Decay as a force of life: how ruins and aged bodies need not signal decline

Vasiliki Souti, 16063547Out of sight, out of mind: this is the motto we as humans and we as architects adopt when it comes to our bodies’ or our buildings’ imminent decay. While Western culture is helplessly trying to censor the traces of time in all visual representations, this essay will argue that an exposure to architectural decay can lead to a familiarisation towards our own ageing. First, I will reflect upon the modern-day tendency to demolish ruins in parallel to ageist behaviours which aim to marginalise the elderly. This will lead to a further discussion on our era’s obsession with newness and youthfulness in architecture and body images respectively. I will then review and contest profit-centered stereotypes about the impotence that ageing brings upon buildings and bodies. Having critically examined the place of decay in contemporary society, the remainder of the essay will focus on ways that ruins can alter our negative approach towards old age. By looking at the reasons why ruins have been extensively admired for their aesthetic attributes through time, I will maintain that a similar perception of beauty could become associated with the ageing body. Following on from that, it will be stated that dilapidating architecture possesses an emotional power in familiarising us with our ineluctable mortal fate. Additional analysis will prove that despite the apparent link between decay and death, the natural regeneration occuring in derelict sites signals life, which can prompt us to view bodily ageing as a procreative process. I will go on to present recent examples of cases in which ruins are viewed as stimulus for confronting fears of obsolescence and mortality. Through an example in the built environment whose ruined state is not concealed but celebrated, I will finally identify how we can establish a mentality that faces signs of decay as a carrier of wisdom and rich history. I will conclude that ceasing to conceal decay in the urban environment can ultimately encourage us to address our stereotyped fear about the inevitable changes that time will induce to our body: old age can instead be viewed as a time when the experience acquired in a lifetime can be used to create new opportunities of enjoying life.

Creating structures that will endure through time has in the past been a primary architectural aim. Nowadays, on the other hand, it is highly unlikely for a building to survive long enough to become a ruin, let alone be worshipped in its ruined state. From the 20th century onwards, building lifespans have decreased to 50 years, in an incessant loop of construction and deconstruction (Sennett, 1996). The case of architects outliving their buildings has become so common that “The Rubble Club” was created for them (Slessor, 2015). The club can be joined by any architect that has had the misfortune of watching the precocious demolition of one of their projects. Nowadays we cannot afford to allow time for a building to age: before decay takes over,

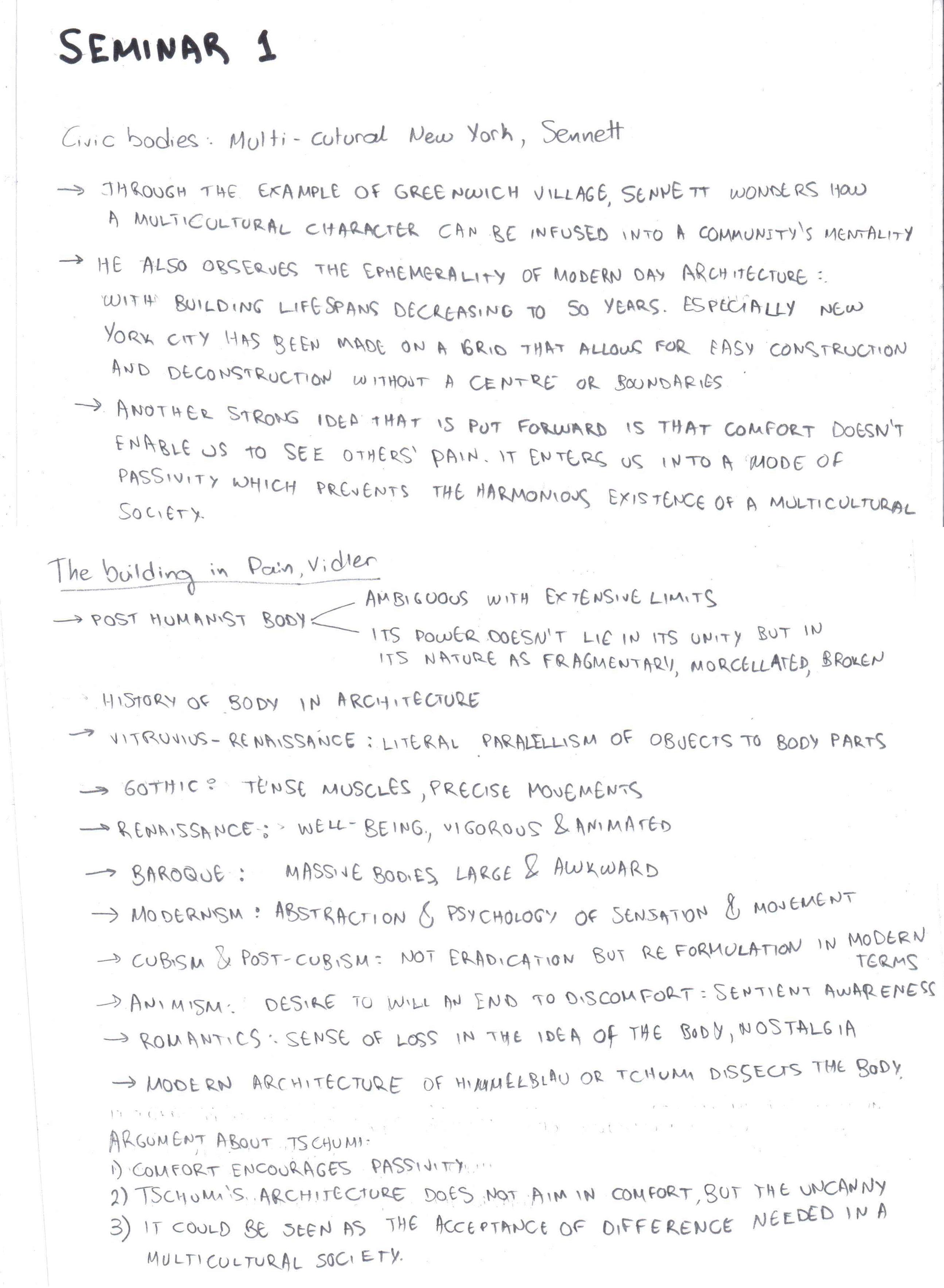

Figure 1: The New Acropolis Museum in Athens; Will the ruins of our high-tech superstructures survive for millennia like the ruins from classical antiquity did? (Source: Michael Photiades Associate Architects, 2009: online)new human needs deem it obsolete and call for its demolition. Scully (1999) thinks that only the buildings with an indisputable reason for surviving will live through the centuries, radioactive waste storage facilities being one example of contemporary architecture that is obliged to last for long. In this context, it is rational to doubt whether the ruins of our high-tech superstructures will survive for millennia like the ruins from classical antiquity did.

While building life-spans have decreased, human life expectancy is constantly rising, leading to an ever-increasing aged population. Still, we marginalise the elderly in the same manner we wipe out buildings as soon as they are of no use to us. Green (2010) identifies a range of ageist stereotypes aimed at old people, which assume that they have limited productivity, high dependence and a lack of physical beauty. This approach is reminiscent of decaying architecture being considered non-profitable, ineffective and ugly. Ageism can reach extreme points, as in the case of an Ugandan tribe described by Turnbull (1989, cited in Green, 2010), that treats the old members of the community as phenomenally dead. In Western cultures, and in contrast to buildings which we can easily dispose of through demolition, our ethical principles do not allow us to eliminate the elderly; instead, we try to conceal them by excluding them from society.

The dominance of ephemeral architecture is a manifestation of our culture’s mania for newness. In his lecture, professor Juhani Pallasmaa remarks a general obsession with progress and innovation in the architectural and artistic field (UNSW Built Environment, 2016). Often, the pursuit of newness is carried out at the expense of other previously fundamental architectural values, such as durability and user experience. For Pallasmaa (UNSW Built Environment, 2016), novelty cannot by itself be an artistic pursuit. Instead, eloquent art and architecture should address the common state and fate of being human. According to Svendsen (2005:75)

In this objective something new is always sought to avoid boredom with the old. But as new is sought only because of its newness, everything turns identical because it lacks all other properties but newness.

At this point, it would be reasonable for me to add that if newness is the principal unique attribute of a building, it is only anticipated that it will fall into desuetude when the first traces of decay start to appear.

If we try to locate bodily perceptions within our culture’s mania for the new and polished we will easily identify our obsession with youthful bodies. In an age awash with images, more attention is paid to external appearance and beauty rather than intellectual development. This becomes more prominent when the female body is involved because its beauty is seen as awe-inspiring, seductive and exclusively youthful (Markson, 2003). In the meantime, as Markson (2003) observed, the naked ageing female body in film is censored, associated with asexuality, infirmity, even repulsion. In view of the above, it is expectable for ageing to be perceived as decline by individuals that base their uniqueness on superficial beauty. If newness in buildings and youthfulness in humans emerge as the fundamental values of our era, one must be wary to contemplate what will become of all the universal virtues that have survived through centuries of man’s presence on earth.

In a world where every square metre translates to dollars and pounds, ruins are often viewed as an unnecessary waste of space. The goal of architecture now revolves around creating functional buildings that satisfy the needs of production and consumption. As Edensor (2005) notes, whether a space is useful is determined by its productivity and thus ruins, especially industrial and post-industrial which are thought to have less historic value, are rendered as counterproductive. They occupy, nevertheless, plots of land that have potential for profit if they are cleared and rebuilt. De Graaf (2015) goes so far as to argue that the value of architecture is nowadays not judged on its function but on its marketability. Many may claim that this practical, unsentimental approach to the architectural environment is the only way to provide for the ever-changing needs of today. However, by deciding on the survival of a building based on whether it is still functional, no consideration is given to the aforementioned derelict sites’ historical and social importance for the city.

A similar root to ageist stereotypes can be identified in the perception of the elderly as an unproductive workforce. Green (2010) argues that ageism should be viewed in the context of our capitalist, profitseeking society that regards the elderly as inefficient. This universal condition becomes most obvious in manifestations of Institutional Ageism, such as forcing older employees to retire early (Green, 2010). Ageist

phenomena in the workplace are mainly fuelled by widespread conceptions about old people’s declining mental competence (McCann and Giles, 2002). Such an approach, however, does not take into consideration their beneficial contributions due to high levels of experience, motivation and company loyalty. Burtless (2013) further challenges stereotypes of decreased productivity in late adulthood by stating that not only is there limited proof to support it, but also that workers between 60-74 years old often outperform their younger counterparts. Therefore, engaging in ageist behaviour is unjustifiable and unthoughtful, since it undermines the positive contribution that the elderly can have in society and does not allow them to share their knowledge with the young.

We have so far analysed the manners in which our culture’s aversion towards decay becomes prominent. As historical knowledge has proves, the undesirability of ageing is much more deeply rooted in human psychology (Troyansky, 1991) than the more recent establishment of ephemeral architecture. Therefore, it is easier to start from valuing decay in architecture and then applying our our appreciative perspective to our ageing bodies. The following paragraphs will examine the ways in which dilapidating architecture can lead to a confrontation with the negative perceptions of bodily ageing, and how we can develop more positive approaches towards old age. The stream of thought will be backed by two areas of research: the first postulates that our architectural surroundings ultimately shape our personality and awareness (Proulx et al., 2016). The second area of research relates to a common psychological practice called exposure therapy, which sustains that continuous exposure to the sources of one’s phobias can eventually eliminate them (Laborda and Miguez, 2015). Thus, I will attempt to prove that the confrontation of decay in the built environment can cure gerontophobic tendencies.

As we have seen, today it is more common for dilapidating architecture to be despised for its obsolescence instead of being praised for its beauty. In the past, however many have dwelled upon the aesthetic significance of ruins. As Makarius (2004) points out, the apotheosis of architectural ruination as a nostalgic tribute to bygone cultures is a notion that was widely popular in the 18th century. Decay in architecture became the aesthetic norm of the era, with artificial ruins being created as a fashionable element to decorate the landscape around wealthy mansions (Edensor, 2005). A century later, Ruskin (1849) believed that architecture should aim to survive through time and be handed over to our descendants as part of their heritage. In this sense, the marks of time would not degrade architecture’s sublimity but instead enhance it, with signs of its previous occupants being embodied in the building’s memory. Even in modern times, it is still not uncommon for ruins to be romanticised and revered for their symbolic meanings. Such emotional connotations emerge because, for romantic thought, ruins are nostalgic memorabilia of what has been lost forever.

While obsession with novelty has not always been an aesthetic datum in architecture, bodily decay has never been embellished with the same notion of beauty that has been attributed to ruins. Representations of the ageing body as barren and unattractive date all the way back to ancient Greece (Gilleard, 2006). In ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, where bodies present perfectioned proportions and characteristics, there is no place for signs of ageing (Troyansky, 1991). A single exception is that of statues aiming to capture the cerebral magnificence of older, notable political and intellectual figures. One of the few periods in history that openly depicted bodies in decay was the Middle Ages. For medieval thought, decay, in the sense of death

Figure 2: If we can find beauty in ruins why can we not see the beauty of the aged body?and the disintegration of the corpse, represented the passing from sinful, mortal life on Earth to eternal, virtuous life in Heaven (Camille, 1992). This is not a celebration of the body in decay on grounds of aesthetic appreciation, but rather rooted in religious beliefs. Nevertheless, constant exposure to bodily decay in art and architecture succeeded in familiarising people with it (Bynum, 1998). During the Renaissance, classical ideals of the perfect young body reemerged (Haughton, 2004) and we can say that since then representations of beauty have gone hand in hand with youthfulness. At the same time ageing is seen as a period of loss and decline, a perception which bears nostalgic connotations. Keeping in mind that the beauty of decaying architecture emerges from the feelings of nostalgia it revokes, I am urged to wonder why we cannot see beauty in old age in the same way we see beauty in ruins. If we are to agree with Ruskin (1849), who holds that marks of occupation and decay encompass buildings’ rich social life, we have to start viewing wrinkles as a badge that celebrates the plenitude of emotions experienced in one’s lifetime.

Frowning upon decay, both as human beings and as architects, is like ignoring a fundamental aspect of life: mortality. According to Dillon (2014), ruins are a tangible reminder of precisely that concept: that architecture -and humans- are not almighty. This psychological response to architectural decay can be traced back to the 18th century. Diderot (1767, cited in Dillon, 2014:16) wrote:

The ideas ruins evoke in me are grand. Everything comes to nothing, everything perishes, everything passes, only the world remains, only time endures.

To view ageist behaviour in the light of Diderot’s reflection may give us a glimpse as to how gerontophobic feelings are incited. Nelson (2002) believes that there is a psychological reaction underlying discriminatory behaviour by the young against the elderly. According to his theory, in their interaction with older people, the young are called to confront feelings of dread towards their own mortal fate. But if the confrontation of a fear is a way of overcoming it, then exposure to the image of both ruins and aged bodies can help us in familiarising ourselves with our inevitable fate. Nelson (2002) also believes that the main difference between ageism and other kinds of discrimination, such as racism or sexism, is the fact that the discriminator (the young) will one day belong to the discriminated (the old), unless they are met with premature death. Here one can discern a valuable lesson for architecture: as it is arrogant for us as humans to be disrespectful towards the elderly since we will one day be old, it is vain for us as architects to turn a blind eye on the decay of our designs which will inevitably fall into eventual desuetude.

At an individual level, the decay of a building may symbolise death. In a more holistic approach, however, it showcases that nature will persevere in defiance of any artificial intervention. A ruin is a building that humans have abandoned to natural forces, a site that nature is claiming as its own. It is a place where architecture fuses into landscape and landscape blends with the architecture (Dillon, 2014). From a utilitarian point of view, a building that has fallen into disuse has reached the terminal stage of its life cycle. What is often overlooked in this approach, however, is that an abandoned site may generate life through fostering non-human organisms (Edensor, 2005). DeSilvey (2006) talks about the “procreative power of decay”, stating that every object is made out of material that has a whole new layer of biological existence that unravels after it fulfills its social purpose. Additionally, Edensor (2005) claims that the forms of flora and fauna that

Figure 3: A ruin is “a place where architecture fuses into landscape and landscape blends with the architecture.”tend to inhabit derelict sites are often labelled by humans as pests. He attributes our despise towards these “ignominious” creatures to our own need for control, since they are a message from nature showing that it cannot be tamed. Especially in the context of a global ecological crisis, ruins are a reminder that regardless of human ambitions to subdue our planet’s power, nature will always have the final say.

Over the passing of time, bodies give in to the forces of nature in the same manner that a building subdues to a ‘brute, downward-dragging, corroding, crumbling power’ (Simmel, 1911, cited in Dillon, 2014:36). As with a ruin that has been left at the mercy of nature, Öberg (2003) thinks that a big factor prejudicing us against ageing is the fear of losing control over bodily changes. However, ambitions of eternal youth are unachievable because ageing is a natural process and to go against nature you have to pay a price. As Sobchack (1999) notes, a plastic-surgery patient has to sacrifice a period of their life to physical and psychological pain. This amount of time can never be given back to them when the effects of the surgery eventually give in to the forces of gravity. Is it not preferable in this case to accept nature’s rules instead of fighting them? The “procreative power of decay” that DeSilvey (2006) found in dilapidating architecture can lead to an awareness of the regenerative power of bodily decay. In a metaphorical sense, instead of a period of socio-economic decline and deterioration of physical appearance, ageing could be viewed as a pathway to a new, knowledgeable life. At the same time, a literal interpretation can show us that in nature, decay and death nurture new life cycles. Therefore, death may signal the end of one’s social life, their body can however be a source of life for another human through organ transplantation, or it can return to the soil as a source of nutrients for other organisms through decomposition.

Despite our obsession with the future, the amusement with ruins still persists among some groups of people who are defiantly choosing to become immersed in decay rather than disregarding it. An example of modernday “Ruinophilia” is Urban Exploration, or Urbex for short. Urbex teams comprise urban ruin enthusiasts who explore abandoned buildings and their history, reproducing them through photography (Williams, 2017). In the Internet world, this photographic trend that captures and is captured by urban decay has been named “ruin porn” (Gansky, 2014). The “ruin porn” movement, which commonly focuses on the post-industrial ruins of Detroit, has been criticised for fetishising the aesthetics of urban decline and poverty without contemplating on the more burning implications of its social and economic origins (Leary, 2011). Notwithstanding such criticism, the movement has a lot to teach us on appreciating history and decay. Tredrea thinks that the abandoned places he photographs “[...] were important and thought about and all of a sudden the world’s just forgotten them. Then people like us go around and take photos and bring them back to life.” (Williams, 2017:online).

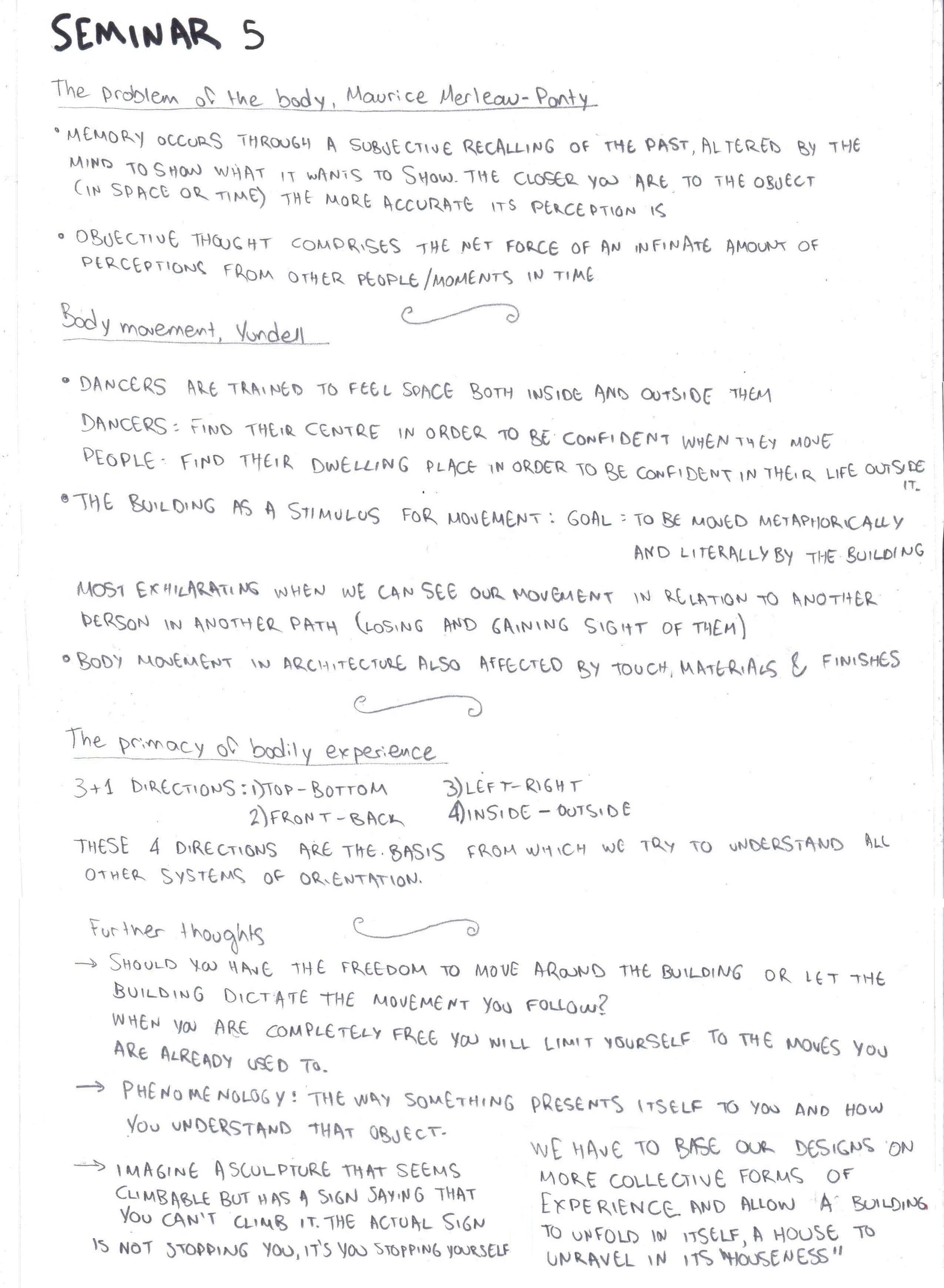

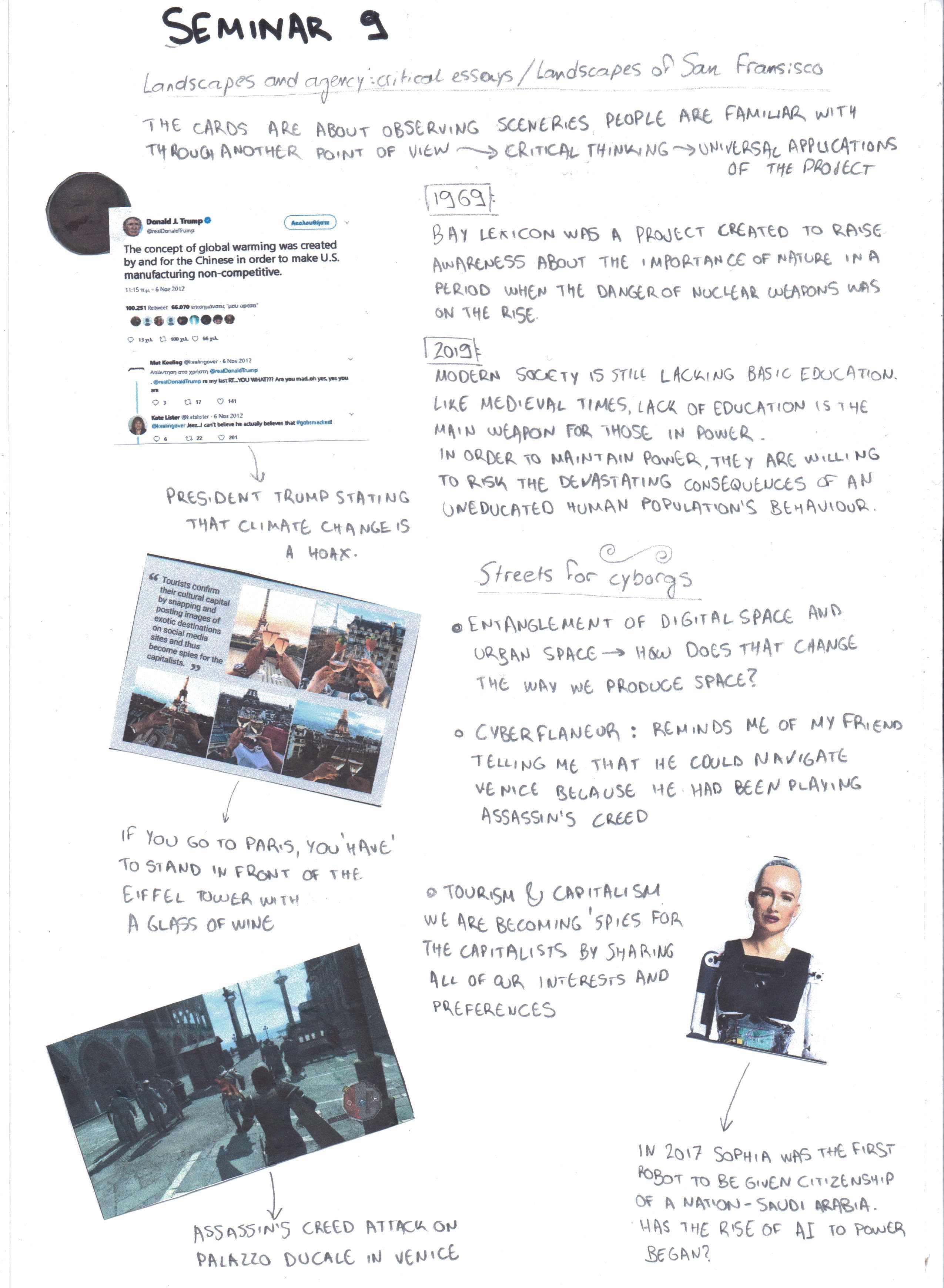

But what happens when Urbex meets the ageing body? In 2006, photographer Sarah R. Bloom decided to search for her identity as a middle-aged woman through a series of self portraits among dilapidating architecture called “Self, Abandoned” (Bloom: no date). This is a practice she still engages in until today. In an online interview she explains: “I’m thinking about [...] how it feels to get older and how it feels to be sort of left behind, which is how I relate to the buildings as they’re left to rot as they stand” (Popp, 2015:0 min 58). In this way ruins, through a metaphorical connection with the ageing body, become the ground for confronting feelings of marginalisation and fears of mortality that are associated with decay.

Figure 4: The ageing body as “rejected material” (Source: Bloom, no date: online)

Figure 4: The ageing body as “rejected material” (Source: Bloom, no date: online)

While the “ruin porn” trend uncovers our anxieties about loss and decline, a rising interest in architectural conservation projects has proved that architecture can be new and at the same time respectful towards decay. A representative example is the Alveole 14 cultural centre by LIN Finn Geipel and Giulia Andi, which is depicted in Figure 5. The project involved the renovation of an abandoned Nazi submarine base in St Nazaire (LIN, 2010). Interestingly, the aforementioned views that deem ruins obsolete are reflected in the published material about this project. In this instance, Jäger (2010) believes that before the architects’ intervention the site was worthless, a pure obstacle to the city centre’s connection with the sea, an unpleasant reminder of the devastation that the city suffered because of the war. In his approach, Jäger fails to see that the architects’ goal was not to interfere with the bunker’s image of decay. Instead, as Capezzuto (2007) confirms, there was minimal architectural intervention to the structure, leaving the signs of decline still intact. New life was breathed into the building by providing it with a social programmatic function, while the remnants of decay were maintained for everyone to see, as a collective memory of the grim past. This is another manifestation of the “procreative power of decay”.

In the same manner that conservation architects are charmed by decay, plenty of artists admire the ageing body and depict it as their primary source of inspiration. Photographer Dylan Collard views the irreversible process of decay as an enriching journey through life. He believes that

Beyond the lines and wrinkles of old age is an unseen life lived, a past filled with experience and learning, acquired knowledge and sometimes wisdom.

(Collard, no date:online). Martin (2018) has claimed that such artistic initiatives can make us reassess the ways we view old age affecting ourselves and the people around us. Considering the research conducted by Proulx et al. (2016) that proves the direct link between the urban environment and the formation of human thought and behaviour, I wish to rephrase the above statement to include architectural, in addition to artistic, initiatives.

This essay has shown how exposure to decay through architecture can prompt us to confront our fears on self-ageing and prove that ageing, whether architectural or bodily, can signal the beginning of new life. In recent years, an intensified marginalisation of aged buildings and aged bodies has arisen, while newness and youthfulness are presented as the ideal principles of human life and creation. This attitude can be attributed to capital-driven motives that deem decay as counterproductive. Thus, ruins and aged bodies can be victims of a similar discrimination. Nevertheless, the aim of this essay is not to view the ageing body as a ruin, but to view both as carriers of a rich living experience that a young person or a new building cannot possess until they reach old age themselves. This full-bodied memory that decay encompasses is exactly where its aesthetic value lies. Moving on, psychological reactions to ruins may urge humans to confront feelings that view the ageing process as an omen of death. However, the “procreative power of decay”, which is present in derelict sites, proves that time does not threaten one’s life purpose but embellishes it. All in all, it can be concluded that a polished built environment, where traces of decay are censored, does not prepare us for the inevitable course of life; befriending decay on the other hand can result in a better understanding of the life course, and thus more satisfaction in our living experience. While the present essay has focused on theoretical analysis, a further cross-disciplinary study could provide tangible research results as to how exposure to architectural decay could act as a form of exposure therapy for gerontophobia.

Figure 5: The Alveole 14 centre celebrates its decay instead of concealing it (Source: Jäger, 2010: 159)