An Immigrant Story of Tragedy and Triumph Sponsor Spotlight

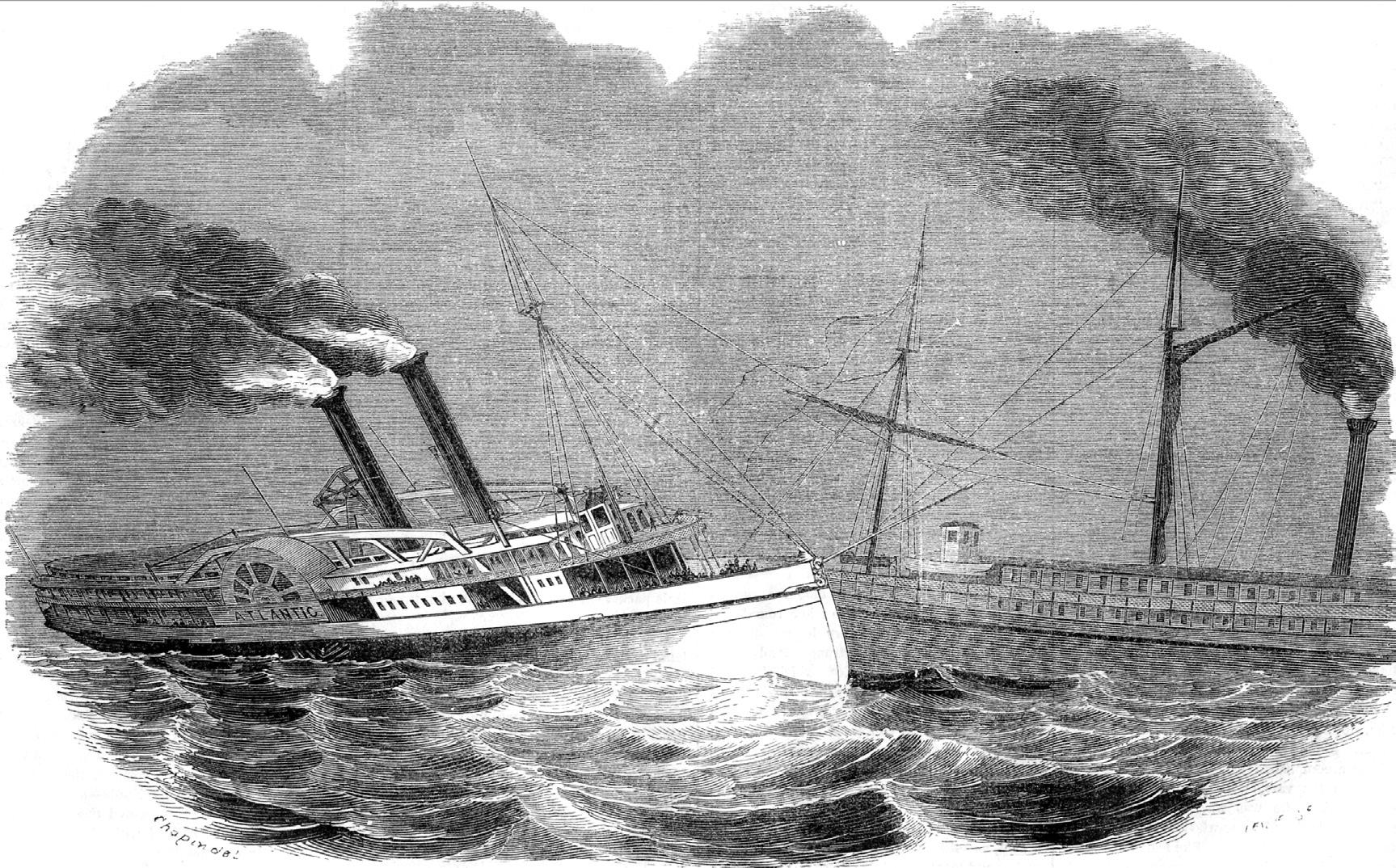

ICollision of the Great Lakes steamers Atlantic and Ogdensburg on Lake Erie, August 20, 1852. From Gleason’s Pictorial, Saturday, September 11, 1852. Courtesy of norwayheritage.com.

The Helles

n 1851, Stephen Olsen Helle returned to Valdres, Norway, from America to bring his mother and fiancée to the home he had prepared for them in the New World. After the three had left Vang, completed their ocean voyage westward, and made the trip through the Erie Canal to Buffalo, New York, the party booked passage on the Atlantic for the trip to Wisconsin.

In the early morning hours of August 20, 1852, Lake Erie in the area above Long Point was blanketed in heavy fog and the darkness was extreme. Passenger Erik Thorstad later recalled what happened in a letter he sent from Ixonia, Jefferson County, Wisconsin, to parents and siblings in Øyer, Norway, on November 9, 1852.

Since it was already late in the evening and I felt very sleepy, I opened my chest, took off my coat and laid it, together with my money and my watch, in the chest. I took out my bed clothes, made me a bed on the chest, and lay down to sleep. But when it was about half past one in the morning I awoke with a heavy shock. Immediately suspecting that another boat had run into ours, I hastened up at once. Since there was great confusion and fright among the passengers, I asked several if our boat had been damaged. But I did not get any reassuring answer. I could not believe that there was any immediate danger, for the engines were still in motion. I went up to the top deck, and then I was convinced at once that the

steamer must have been damaged, for many people were lowering about with the greatest haste. Many from the lowest deck got into the boat directly, and as the boat had taken in water on being lowered, it sank immediately and all were drowned.

Thereupon I went down to the second deck, hoping to find means of rescue. At that very moment the water rushed into the boat and the engines stopped. Then a pitiful cry arose. I and one of my comrades had taken hold of the stairs which led from the second to the third deck, but soon there was so many hands on it that we let go, knowing that we could not thus be saved. We thereupon climbed up to the third deck, where the pilot was at the wheel. I had altogether given up hope of being saved, for the boat began to sink more and more, and the water almost reached up there. While we stood thus, much distressed, we saw several people putting out a small boat, whereupon we at once hastened to help. We succeeded in getting it well out, and I was one of the first to get into the boat. When there were as many as the boat could hold, it was fortunately pushed away from the steamer. As oars were wanting, we rowed with our hands, and several bailed water from the boat with their hats.

A ray of light, which we had seen far away when we were on the wreck and which we had taken for a lighthouse, we soon found to be a steamer hurrying to

give us help. We were taken aboard directly, and then those who were on the wreck as well as those who were still paddling in the water were picked up.

This boat, which was the one that had sunk ours, was of the kind known as a propeller, driven by a screw in the stern. The misery and the cries of distress which I witnessed and heard that night are indescribable, and I shall not forget it all as long as I live. The number of drowned were more that 300, of whom sixty-eight were Norwegians. Many of the persons who were in the first class were drowned in their berths or staterooms. The Norwegians who were rescued totaled sixty-four, but most of them lost everything. I saw many on board the propeller who had on only shirts.1

The Atlantic, transporting Norwegian immigrants to the Midwest, had ran afoul of the Ogdensburg, whose propeller struck the Atlantic forward of the wheel, on the port side. Stephen Olsen Helle, his fiancée, Marit Nilsdatter FylkenAlfstad, and his mother, Marit Steffendatter Brekken-Helle, were tossed into Lake Erie and clung desperately onto a piece of floating timber. When it became apparent that all three could not survive, Stephen’s mother decided to sacrifice herself for the new couple. Marit S. Helle, then 71 years, died after 11:00 p.m. August 20, 1852, in Lake Erie. A memorial stands in the city of Buffalo, New York, which commemorates the famous AtlanticOgdensburg collision.

This incident, so tragic and so touching, supplies a note of sobering drama in an immigrant story that in many other respects was very typical. Stephen Olsen Helle was the second son of Marit and Ola, who were married in 1801. Ola died at the early age of 48 in 1821, leaving Marit with three small sons, Thomas, Stephen, and Ole. The lives of the widow and her three children were ones of hardship and struggle, but together they managed to survive on the Helle farm.

Thomas, the eldest son, would, by tradition, inherit the family farm, so with his military service completed, Stephen— as with numerous other young men at the time—faced the challenging decision of what to do with his life.

In 1846 Stephen and his younger brother Ole traveled to the Wisconsin Territory from Harum, Vang, Valdres-Oppland, Norway, and were able to share many details and personal impressions. They found work as carpenters and explored the

unsettled lands of densely forested Manitowoc County. Stephen and Ole wrote from Port Washington to family and friends in Norway, detailing the opportunities available in America for those who would risk the arduous trip. By 1847, undoubtedly encouraged by those letters, their cousin, Thomas Anderson Veblen, and his family, joined the brothers.

But the Veblens were not the only ones enticed by the messages that Stephen and Ole sent across the Atlantic. By 1848, eldest brother Thomas had married and he and his wife Kari had four children, three sons—Ole, Even, and Thomas— and daughter Marit. Life was hard in Vang. The growing season was short and the climate became extremely damp, with excessive precipitation, for several generations. Crops failed and grain was difficult to dry. Despite the fact that they had never left their valley, Thomas and Kari determined to bring their family to America, too.

Around Christmas time in 1847 Stephen and Ole returned to Norway and the following spring they again made the trip to America, this time bringing with them Thomas and his family, and Ragnild Helle, whom Ole had married.

When the party arrived in Port Washington on August 1, 1848, they had been traveling since April. Eventually they moved to Manitowoc County and Thomas built a log home for his family that is still preserved at the Pinecrest Historical Village in Maitowoc, Wisconsin. Ole and Ragnild built a home nearby. Thomas and Kari had two more children, daughter Siri (Sarah), born 1850, and son Knut, born 1854.

In 1851 Stephen Olsen Helle traveled again to Norway, this time to accompany his beloved mother and his fiancée on their journey to America. In August 1852, as the three boarded the Atlantic on the last leg of their journey to their new home, Stephen and the two Marits were no doubt looking forward to being reunited with Thomas and Ole, and their families. Instead, on that dark, foggy morning on Lake Erie, the Atlantic and the Ogdensburg collided.

Marit Helle perished, but her three sons and their progeny flourished in the New World. Today, her great-great-great grandson, John W. Thompson, is now president of Thompson Investment Management, Inc., of Madison, Wisconsin, sponsor of this issue of Vesterheim

Endnotes

1 Nanna Egidius, Trond Austheim, and Børge Solem “Disaster on Lake Erie,” Norway-Heritage Hands Across the Sea, 2001, http://www.norwayheritage.com/ articles/templates/great-disasters.asp?articleid=33&zoneid=1.

This log home was built by Thomas O. Helle when he first arrived in Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. It is now part of Pinecrest Historical Village in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Courtesy of Manitowoc County Historical Society.