Queen Maud of Norway: A Homesick Immigrant (1869-1938)

by Rachel Faldet

At First

Around morning rush hour, I step of an express train from Gatwick airport into unexplained confusion. Ofcials shout. Te Underground in central London is closed. Taxi drivers don’t stop. My traveling companion and I drag suitcases-on-wheels away from London Victoria station, consult a paper map, walk miles toward the Victoria & Albert Museum. I persuade a nearby hotel concierge—who learns we are jet-lagged Americans—to keep our bags, though we are not guests. In the museum, en route to an arts and crafts gallery, we chance upon Style & Splendour: Queen Maud of Norway’s Wardrobe 1896-1938. Clothed mannequins are my unfulflled gaze as a loudspeaker commands everyone to evacuate the galleries, gather together, stay in the building.

A suspicious bag is on the pavement.

Unhinged, not knowing the magnitude of public terror, I long to sneak to cases of glass-beaded evening gowns and fur-trimmed daywear, shoes, and clutch handbags, study their details and detach from the problem of how, with transportation shut down, we will get to our out-of-the-city destination where a bed is waiting.

On July 7, 2005, I crave Queen Maud.

Royal Pedigree from Queen Victoria of Great Britain and Ireland

Princess Maud Charlotte Mary Victoria, granddaughter of Queen Victoria of Great Britain and Ireland and Empress of India, did not grow up in the country where she was crowned. European royals typically looked to other countries for marriage partners, with politically-motivated match-makers pushing cousins together. Royal marriage partners could stay within their social class, gain titles, make powerful alliances, but also be lonely, not knowing whom to trust. At times, as with frst cousins Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of SaxeCoburg and Gotha, there was also love. Tat pair produced nine children, including Princess Maud’s father, heir to the British Empire.

Unraveling the descendants of Queen Victoria—who was crowned in 1837 at eighteen and died at eighty-one in 1901—is tricky, because relatives were often named the same name and/or had nicknames. Given names could change when acquiring titles through inheritance, marriage, or reward. Dynastic houses—the Germanic Hanoverians in Princess Maud’s grandmother’s case—relied on mystique and relevance to survive, because monarchies can be viewed as parasites. For instance, after Prince Albert died in 1861, the widowed queen embraced perpetual mourning in black clothing, hiding from her subjects, even refusing to wear the Imperial State Crown because its showcase gems were colored. To dampen antimonarchy rumblings and unrest, jewelers made the 1870 Small Diamond Crown, set with over 1000 colorless diamonds, for the queen to wear during ofcial events. Te Imperial State Crown, carried on a cushion, accompanied her to symbolically

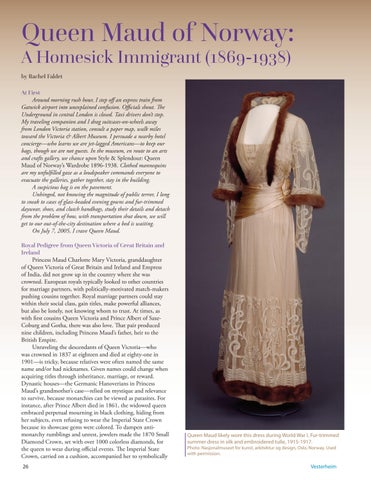

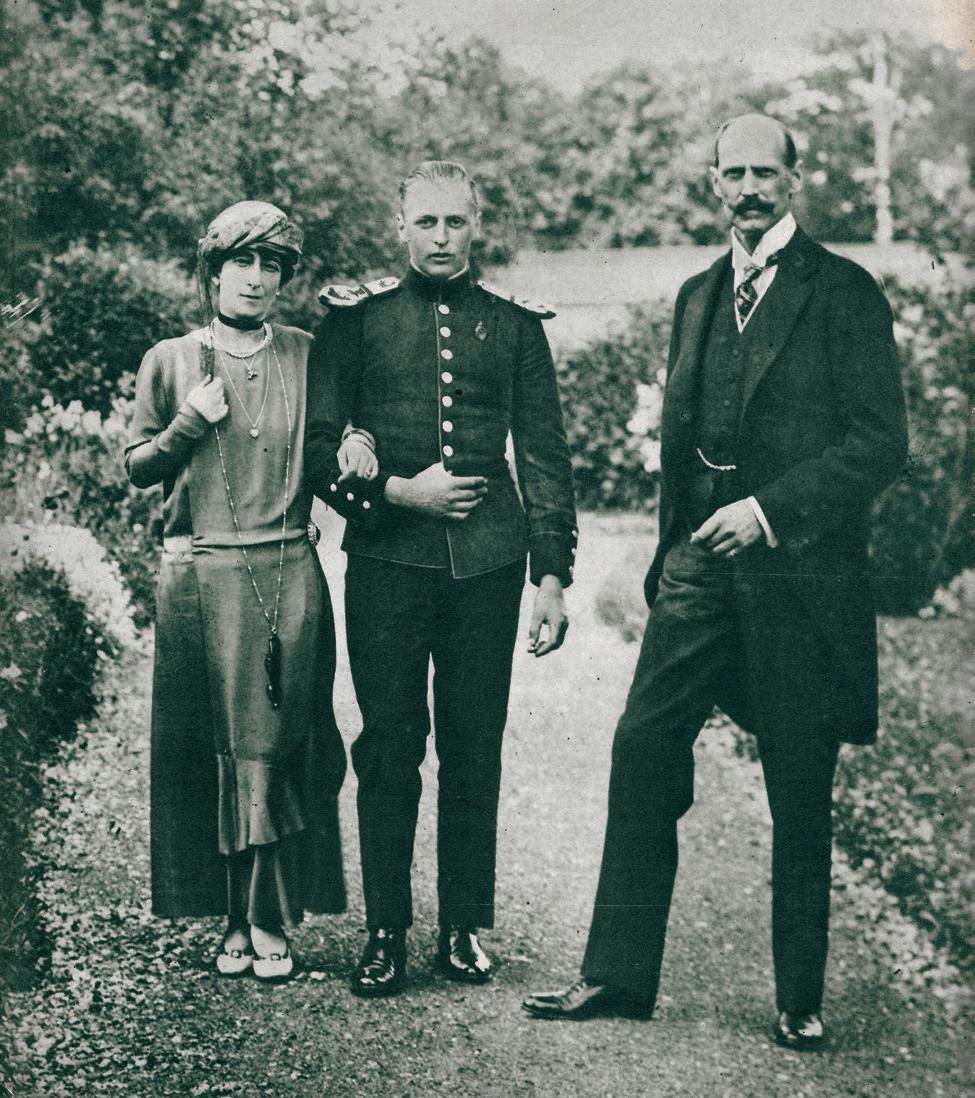

photograph of

enforce the necessity of a hereditary royal family at the helm of privilege. In 1870, Queen Victoria’s greenish-eyed granddaughter – the youngest child of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, and Alexandra of Denmark, who, upon marriage, became Princess of Wales—was not yet a year old.

Princess Maud was born in London on November 26, 1869, and raised in Sandringham House (still belonging to Great Britain’s royal family) in wooded, rural Norfolk in East Anglia. Tough Princess Maud’s father had a difcult relationship with his parents and was known for marital infdelities, as king he actively promoted peace between France, Russia, Germany, and England. Princess Maud’s mother, the “Danish pearl,” became a British fashion icon. While the Prince of Wales was a stand-ofsh father, his wife encouraged their fve children to laugh and have fun. In an 1875 family portrait by Heinrich von Angeli, the “focal point” is Princess of Wales Alexandra’s “hand, which rests on her daughter’s lap,” indicating that the “emotional bond” between Princess Maud and her mother “seems stronger than that between husband and wife.”1 ‘Motherdear,’ known for her beauty, kept the children in simple, yet tasteful, clothing, not allowing the girls to wear rings before becoming engaged.2

As a child, Princess Maud was shy but boisterous, keen on riding horses and bicycles, a tennis player and yachter, tomboyish and petite, strong-willed, and she answered to “Harry.” She and her sisters wore identical dresses, even as teens. As traditional for princesses, she was lightly tutored at home, excelling in dancing. She became friends with frst

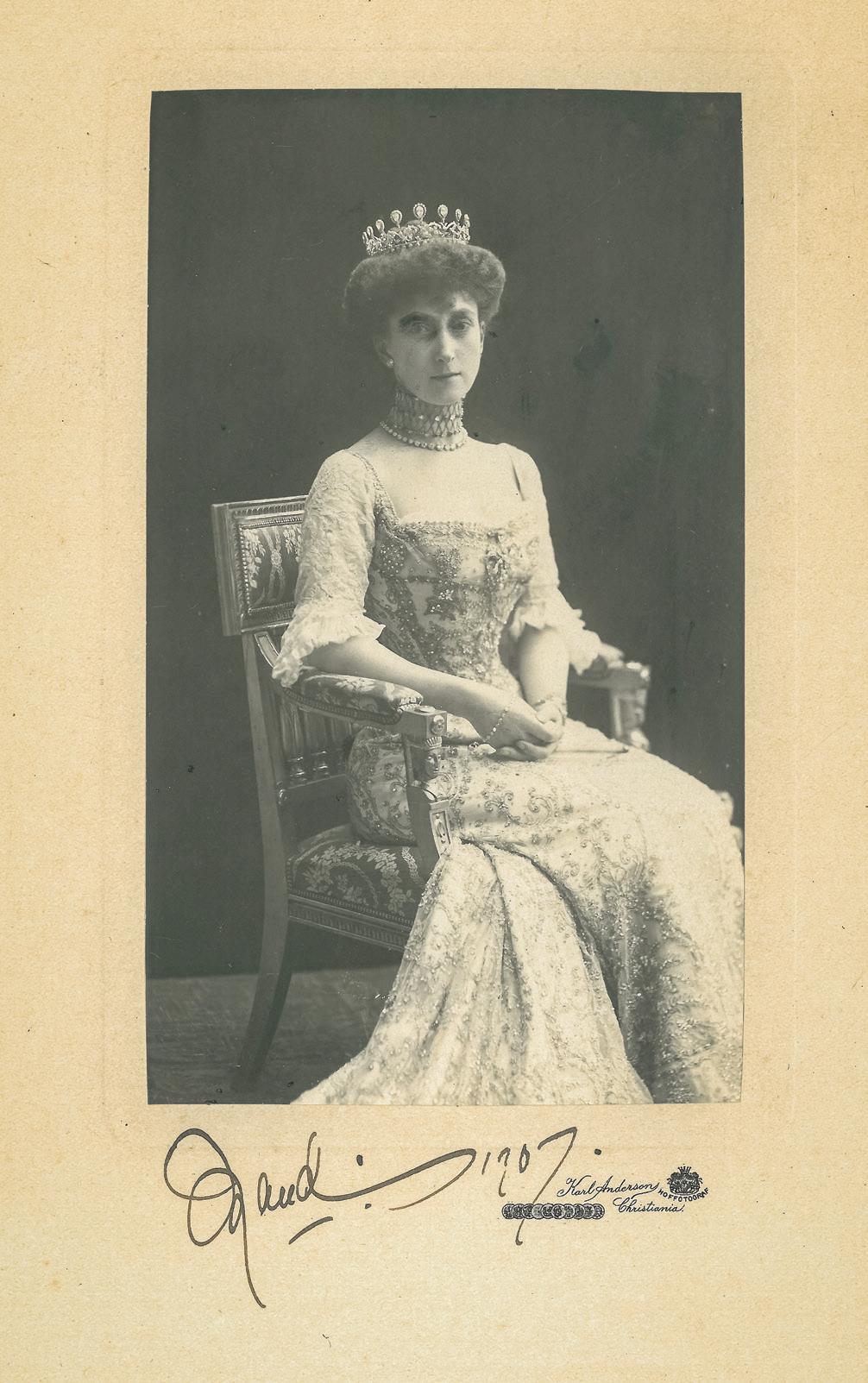

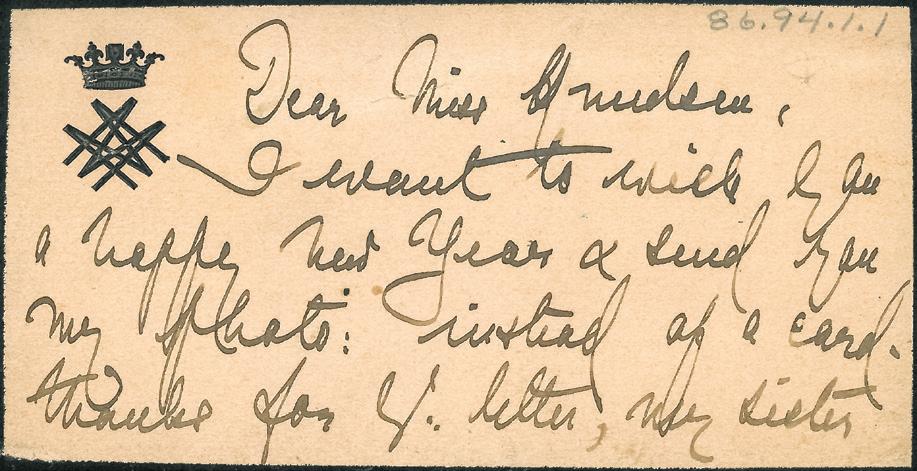

Handwritten card from Maud, then Princess Maud of Wales and later Queen Maud of Norway, to a Miss Knudsen, c. 1895. Notice the reference to Sandrigen. Vesterheim 1986.094.001—Gift of Mabel Thorsen.

cousins on her father’s side, including younger, motherless Princess Alexandra (Alicky) who traveled from Hesse to visit their shared grandmother in Great Britain. Tough Queen Victoria’s diaries and letters reveal her as an unpleasant mother, “the grandmother of Europe” was said to be afectionate with grandchildren. Trough frequent visits to her mother’s Danish homeland, the English princess became a playmate with her outdoor-life-loving frst cousins, the grandchildren of King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Hesse-Cassel.

Under their mother Princess Alexandra’s care, the Wales siblings grew up as close companions, living in Marlborough House when in London, and surrounded by nature in Sandringham. Princess Maud’s oldest brother, Prince Albert Victor, was heir to the throne after their father, though he died of pneumonia, age twenty-eight, six weeks before his arranged wedding to Princess May of Teck in 1892. In 1893 Princess Maud’s brother Prince George married his deceased brother’s fancée—later he became King George V and May became Queen Mary. Princess Maud’s sister, Princess Louise, married for love, and named her daughters Alexandra and Maud. Princess Victoria, a spinster, became a companion for the quintet’s mother, who was increasingly hard of hearing and socially isolated.

Marrying a Danish Cousin and a Love of Home

In autumn 1895, after possible matches fzzled, the nearly twenty-fve-year-old Princess Maud’s engagement to her frst cousin, Prince Christian Frederik Carl Georg Valdemar Axel of Denmark, was announced. Her husband-to-be was twentythree, a speaker of Danish and English, a son of Princess of Wales Alexandra’s brother. Not expecting to be a king, Princess Maud’s betrothed was a Danish Navy man, enjoying long sea stints. Te Danes called the royal ofcer, who sported an anchor tattoo and entered naval training at fourteen, Carl. English relatives called him Charles. Childhood friends, the pair’s adult relationship was a love match, cemented by a desire

to live in a private, simple style, rather than that of fussy court life. After their July 22, 1896 wedding in Buckingham Palace, the newlyweds remained in England for some months, near her parents at Sandringham, before settling in Copenhagen. Princess Maud’s father, still the Prince of Wales, thought the groom “an excellent choice, as he is both charming and good-looking.”3 Some relatives expressed concern about the bride’s ability to adapt to another country, because she loved England and was painfully shy. Teir predictions proved true: Troughout her immigrant life, she often returned home. When Princess Maud’s grandmother, Queen Victoria, was buried on Windsor Castle grounds in 1901, only a few years remained until the loyal-to-England royal was anointed queen of a Scandinavian country whose language she never learned to speak fuently.

Prince Carl’s and Princess Maud’s quiet nine-year-Danish life changed on June 7, 1905, when union between Norway and Sweden was dissolved by the Storting (Norwegian National Assembly). Te two countries would no longer share a king. Te Storting debated not only on who should be king, but whether Norway should be a democracy without a monarch. Princess Maud, related to an iconic British queen and already mother to a son, was a political bonus to Prince Carl’s candidacy. Urged by his father-in-law, now King Edward VII, the future Haakon VII accepted Norway’s ofer, though he held out until a plebiscite proved the country desired a monarch. After a rough November 1905 yacht voyage, the frst king and queen of an independent Norway and the toddler heir to their throne (whose name changed to Crown Prince Olav) arrived in foggy, snowy Christiania (later named Oslo).

Teir coronation ceremony was June 22, 1906 at Trondheim’s Nidaros Cathedral. In loyalty to England, thirty-six-year-old Queen Maud “broke with tradition by selecting a gown without Norwegian symbols.”4 Te couture foor-length dress with an embellished train and scalloped lace sleeves—most likely a “collaboration of dressmakers from Maud’s country of birth and her new homeland”—was gold lamé decorated with embroidered fowers and ribbon bows “in gilt metal thread, gold-coloured sequins, artifcial pearls

and diamanté.”5 Draped in fur-trimmed coronation robes and holding regalia, Queen Maud and King Haakon VII (whose subjects came to call him “Mr. King”) posed for pictures reprinted in newspapers and magazines.

Diminutive Queen Maud, who inherited her Danish mother’s fashion sense, was fascinating for royal watchers. Magazines such as New York’s Good Housekeeping contained stories, often authored by men, that fed on public hunger for details on clothes, hairstyles, family, activities, and worries of dynastic females. In April 1912, for instance, on World War I’s cusp, Queen Maud was featured in an article about queens safeguarding their children from assassination or kidnapping. Te author claimed children were not “pampered and spoiled pets of indulgent royal parents,” and that Prince Olav “has long been weeping for a motor car of his own, and he is never happier than when discussing carburetors and cylinders with the royal chaufeur.” On the other hand, the writer said the Romanov siblings (children of Queen Maud’s cousin Alicky) in Russia “are the inmates of the imperial nursery” whom “one almost pities.”6

Trying to ft into a culture as an invited outsider, embracing outdoor pursuits of skiing, ice skating, and tobogganing soon after her arrival, while keeping her habit of riding side saddle several hours a day, the Queen did not give her heart wholly to Scandinavia. Her book plate—a coat of arms to identify books in her collection – featured the Norwegian fag, the British fag, a lone tree overlooking a ford, and the words “Queen Maud of Norway” written in English. Much of her exquisite clothing was made in England or France, because she stayed faithful to couture houses frequented by her mother. Queen Maud, who appeared at ofcial Norwegian events and ceremonies and went on state visits abroad, was often draped in long strands of pearls, her

Cup made by Porsgrund Porcelain Factory to commemorate the coronation of King Haakon VII and Queen Maud.

Vesterheim 2005.025.001—Gift of Solveig Reinhartsen Bender in memory of Dagny Reinhartsen Almendinger.

Medal commemorating the coronation of King Haakon VII and Queen Maud of Norway, June 22, 1906.

Vesterheim 1978.094.001—Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Storm Bull.

hemlines changing with appropriate trends. As she aged, she forsook the tightly corseted wasp-waist style (on some dresses the waist measured eighteen inches) for looser gowns. Te fur-trimmed, brown wool winter coat worn soon after the end of World War I was a showpiece for onlookers as she skied “so that fne lines of red fash at the pocket and cuf.”7

An amateur photographer, she snapped people and places in Norway, connecting through photo albums with royal and governmental visitors to the country.

Te Queen’s close ties to her English homeland were partly due to the gift of Appleton House, fully furnished, on the vast Sandringham estate of her childhood. Tis brick house of twenty rooms—a wedding present from her parents—and her close-knit family lured her back regularly. She viewed “Appleton House as her one true home, because it was located in the country she loved most and in the county— Norfolk—she liked best.” Not only did lengthy visits home “soothe Maud’s very English soul; from a physical standpoint, they proved to be a necessity” because her constitution was “delicate” and she sufered from bronchitis and neuralgia.8 Indeed, the royal pair’s only child—Alexander Edward Christian Frederik before his Norwegian name change to Olav—was born on July 2, 1903 at Appleton House.

Annually, Queen Maud’s mother, also a royal immigrant, left England to visit Queen Maud for months in Scandinavia. With son in tow, the Norwegian queen returned to England by boat with her Danish mother in late October, going back to Norway before Christmas. Echoing Queen Maud’s childhood, Crown Prince Olav socialized and played games with frst cousins. One game was war with model soldiers, in which the opposing sides were celestial planets, not countries, per rules from Uncle King George V.9 Leaving without her Danish husband for a dose of England helped the immigrant live in Scandinavia the rest of the year with more comfort, but this was interpreted by some Norwegians as being an aversion to

Norway. Some worried the heir to the throne would not be fuent in the kingdom’s language, and noted that Queen Maud attended Anglican church services rather than the Norwegian church King Haakon VII attended. If the claim that Queen Maud inherited her mother’s afiction of impaired hearing is added to an imperfect understanding of the language, no wonder Norwegians viewed their shy queen as “en selvstendig kvinne” (an independent woman).10

Neutrality When Close Relatives are Fighting in World War I World War I’s history contains tangled layers of personnel, strategies, battles, casualties, poisonous gas, political outcomes, cemeteries, and family stories. Queen Maud’s extended family were key players. Tough Queen Maud’s brother, King George V, was on the British throne when World War I broke out in 1914, the scene was set decades earlier by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s hatred and jealousy of his English relatives, particularly his cousin (Maud’s father) and the Kaiser’s own mother—both children of Queen Victoria of Great Britain. Son of a German emperor-father, Queen Victoria’s oldest grandchild, Wilhelm, felt he deserved better respect from his mother’s clan, and this created a smoldering backdrop of family dysfunction.

In June of 1887, the Golden Jubilee celebrating ffty years of Queen Victoria’s reign, soon-to-become-Kaiser Wilhelm II was not asked to participate in a procession of invited royals from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey to

King Håkon VII and Queen Maude donated this tapestry to the Lutheran Deaconess Hospital in Park Ridge, Illinois, for a fundraiser in 1908 or 1909. The tapestry, De Tre Brødre (The Three Brothers),based on a 1900 design by Gerhard Munthe, depicts a folk tale in which three beautiful princesses are kidnapped and locked inside the trolls’ castle. The trolls throw the key out the window and bewitch the women’s sweethearts, three brothers, transforming them into a deer, a fsh, and a bird. After years of searching, the bird fnds the key, and with the help of the deer and the fsh, rushes to the castle to unlock the door. The princesses recognize their sweethearts, who then instantly return to their human forms.

De Tre Brødre (The Three Brothers), tapestry woven by an unknown weaver before 1908 and woven and sold through Den Norske Husfidsforening in Oslo. Vesterheim 1982.114.1—Gift of Lutheran Deaconess Hospital through Sister Esther Aus.

the accompaniment of cheering crowds. Te procession was choreographed by his uncle (Maud’s father) and included the Queen’s granddaughters in carriages. Wilhelm was “seething with rage against his English relations” during the church ceremony, packed with thousands of witnesses, because he didn’t get “the starring role that he considered his due as eldest grandson.”11 Ten years later, when he’d inherited his father’s realm, his grandmother didn’t invite him to her 1897 Diamond Jubilee. If the British followed protocol, an Emperor of Germany deserved a place of honor. Instead, they ostracized him. His revengeful personality and hostile politics put him at odds with English relatives. Family feuds escalated into a naval competition between Great Britain and Germany, though Princess Maud’s father tried to keep peace.

World War I broke out when a Serbian assassin shot Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in June 1914. Prince Olav was approaching eleven, Queen Maud was forty-four. Her brother, George V, was king of her homeland; their father had died in 1910. When Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, diplomatic alliances drew much of Europe into confict. Allies of Russia, England, and France (later joined by Romania, Italy, and United States) opposed Central Powers of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary (later joined by Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria). Germany, with a strong military culture promoted by Kaiser Wilhelm II, used the outbreak of war as pretext for expansion of its borders, moving into its neutral neighbors, Luxembourg and Belgium, and then into France. Germany and its forces were stopped by the Allies in a long line of trenches on the Western Front extending from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps. In the east, Russia attacked Prussia and Galicia, where Austria-Hungary met them in engagements creating an Eastern Front stretching nearly 1000 miles.

Tough King Haakon VII kept Norway neutral and blocked politically dangerous visits from pro-German Scandinavian queens to Norway, Queen Maud’s emotions were slammed by the war. She detested Kaiser Wilhelm II, siding against Germany. A keen letter-writer throughout her adult life, Queen Maud corresponded with Queen Mary of England, her sister-in-law, including this August 27, 1914 message, “All my thoughts and prayers are with you all and our brave soldiers and seamen and may we only be victorious and crush the enemy forever.”12 Tsarina Alexandra of Russia— Queen Maud’s cousin/childhood playmate Alicky—wrote a religious leader in 1915, “Te sufering around is too intense. You, who know all the members of our family so very well, can understand what we go through—relations on all sides, one against the other.”13 In this case, the cousins were on the same side, because Russia was allied with Britain. Tough no fghting occurred on Norwegian soil, “after the May 31, 1916 Battle of Jutland, of the coast of Norway, where Britain lost 14 ships and had 6,784 casualties, a visitor to the palace [was] told Maud ‘laid in her bed three days and cried.’”14

During World War I, Scandinavian countries maintained neutrality, but were pressured by both the Allies and Central Powers to provide goods and access. Shipping in the Atlantic and Baltic was afected by an Allied blockade of Germany countered by the German navy’s aggressive employment of patrol ships, mines, and submarines. Seas were dangerous. Not returning home to England for several months each year was Queen Maud’s war sacrifce. Te last English relative she

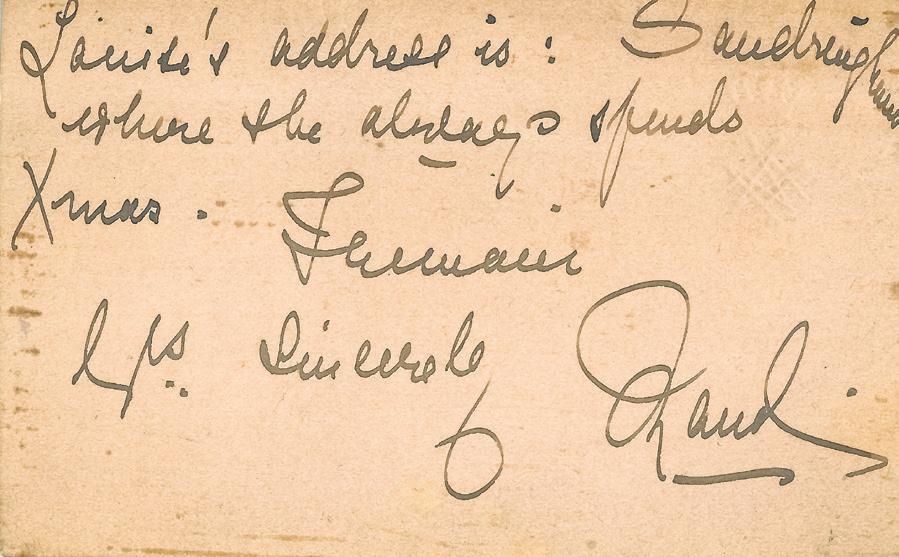

Photograph of Queen Maud, ever conscious of style, in 1929, from Haakon VII 1905-1930 Festskrift til 25 års Regjeringsjubileet, published by Fabritius & Sønner Forlag. Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum Library Collection.

saw, before the war, was frst cousin Queen Consort Victoria Eugenie of Spain in 1914. Trapped in Norway, Queen Maud’s anguish was hearing details of what relatives and countries faced. When new in Norway, Queen Maud plunged into charitable work by taking “a leading role in subscribing to a home for unmarried mothers and attending a public meeting on its behalf, a bold stand that few in the face of ‘respectable’ opinion.”15 She showed further concern for needy Norwegians, only months after World War I commenced, when she headed the Queen’s Relief Committee, which helped parishes in the capital collect and distribute medicine, clothes, fuel, and food. While other European countries experienced peasant uprisings, severe food shortages, and monarchs fearing for their safety, Queen Maud took refuge in her beautiful Norwegian estates and palaces. In 1917, because the world fell apart, she posed for idyllic photographs at Kongsgård, a royal country estate. In one, teenaged Crown Prince Olav—in short pants, matching jacket, and tie—stands in a small dragon-headed boat on the shore of an ornamental lake. His mother, in a just-above-the-ankle-striped skirt, fancy-blouse, and high-heels is fanked by two dogs wearing bows around their necks.16 By the time the war ended in 1918, Queen Maud was almost forty-nine. Te feud between heavily-connected royal families of Europe claimed 17 million civilian and military lives, and left 20 million wounded. In Norway, the monarchy was not overthrown. King Haakon VII didn’t betray his wife as the royal husbands of some of Maud’s cousins did. Teir son, heir to the throne, was admired by Norwegians. Te immigrant trio lived. Compared to her four frst cousins, who married heirs to European thrones, Queen Maud was least scathed during World War I and its lengthy aftermath.

Queen Consort Sophie of the Hellenes was exiled, fnding bitter refuge in Switzerland and snubbed because she was Kaiser Wilhelm II’s sister. Queen Consort Victoria Eugenie of Spain was victim of an assassination attempt on her 1906 wedding day in Spain and, neglected-by-her-husband

and as mother of two hemophiliacs, was treated with mean skepticism before her 1930s exile. Queen Consort Marie of Romania sufered, in reduced circumstances, along with her people during dark days of World War I, glad to eat beans, and persecuted horribly by her son Carol II during his post-war tyrannical rule. Deposed Tsarina Alexandra (Alicky) and Tsar Nicholas of Russia and their fve children were executed by a fring squad in 1918 in Ekaterinburg. War-time decisionmaking compelled their cousin, King George V of Great Britain, Queen Maud’s brother, to refuse the Romanovs asylum, perhaps saving the British monarchy from destruction. Earlier he renamed the British royals the House of Windsor to divorce the family from its Germanic roots.

As soon as seas were deemed safe after World War I, Queen Maud took an escorted boat to England, home to Appleton House.

One Last Trip To Beloved England

Tough King Haakon VII delayed her departure for a week due to political reasons, in October 1938, sixty-eightyear-old Queen Maud, a grandmother of three, left Norway one last time for her stint in Appleton. On a London shopping trip, the Queen felt unwell, underwent an operation, and died in her sleep on November 20. Her cofn was brought to Marlborough House, her childhood London home, and then to Norway by sea, arriving on her birthday. Te funeral was held in Oslo and she was buried in Akershus Castle’s Royal Mausoleum. Widowed King Haakon VII wrote to King George VI—his English nephew and father of the princess later crowned Great Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II—“it was too much for me when I found presents for me from [your] darling Aunt Maud.”17 As usual, the queen for thirty-three years had planned to return to Norway for Christmas.

And Then

After the Victoria &Albert Museum frees people, my husband and I walk hours in chaos until an evening train transports us out of London. Other conference-goers are shocked because some Brits are afraid to travel. Four suicide bombers injure hundreds and kill 52 in the London Underground and on a double-decker bus during rush hour on the morning I glimpse Queen Maud’s haunting possessions.

Months later, after receiving the Victoria &Albert book Style & Splendour: Te Wardrobe of Queen Maud of Norway as a gift, I realize the 2005 London exhibition of exquisitely handmade garments and lovely accessories perfectly celebrates the 100th birthday of Norway, the independent country that became an English princess’s immigrant home.

Endnotes

1 Jane Ridley, Te Heir Apparent: Te Life of Edward VII, Te Playboy Prince, (New York: Random, 2013), 198.

2 William Armstrong, “King Edward’s Favorite Daughter: Queen Maud of Norway,” Woman’s Home Companion, Vol. 40, January 1913, 18.

3 Julia P. Gelardi, Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria, (New York: St.Martin’s, 2005), 63.

4 Te Royal House of Norway website, royalcourt.no, 2017.

5 Anne Kjellberg, Anne and Susan North, Style & Splendour: Te Wardrobe of Queen Maud of Norway, (London: V&A Publications, 2005), 14.

6 Richard Fletcher, “Royal Mothers and Teir Children,” Good Housekeeping, Vol. 54, April 1912, 450, 455.

7 Kjellberg and North, 68.

8 Gelardi, 71-72, 102.

9 John Van der Kiste, Northern Crowns: Te Kings of Modern Scandinavia, (United Kingdom: Sutton, 1996), 55.

10 Jo Benkow and A.B. Wilse, Haakon, Maud og Olav, (Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlad, 1989), 34.

11 Ridley, 302, 303.

12 Tor Bomann-Larsen, Makten: Haakon & Maud—IV, (Oslo: Cappelen, 2008), 71.

13 Gelardi, 216-217.

14 Bomann-Larsen, 96.

15 Van der Kiste, 56.

16 Benkow and Wilse, 94.

17 Van der Kiste, 100.

Other Sources

Berggrav, Eivind. Mennesket Dronning Maud. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1956.

Bjaaland, Patricia C. Te Norwegian Royal Family. Oslo: Tano, 1986.

Greve, Tim. Trans. Tomas Kingston Derry. Haakon VII of Norway: Te Man and the Monarch. Vol. I. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1983.

About the Author

Rachel Faldet is on the English faculty at Luther College. Trough numerous stints co-leading year-long and Januaryterm study-abroad programs in England, she developed a keen obsession with British nobility and royals. She thanks David Faldet, Jimmy Eriksson, and Google Translate for help with Norwegian language sources.