ELEMENTS SUPPORTING AUTHENTICITY

PhilipIVhuntingWildBoar,c.1634-1635,Thepreparatorystudy,

PhilipIVhuntingWildBoar,c.1634-1635,Thepreparatorystudy,

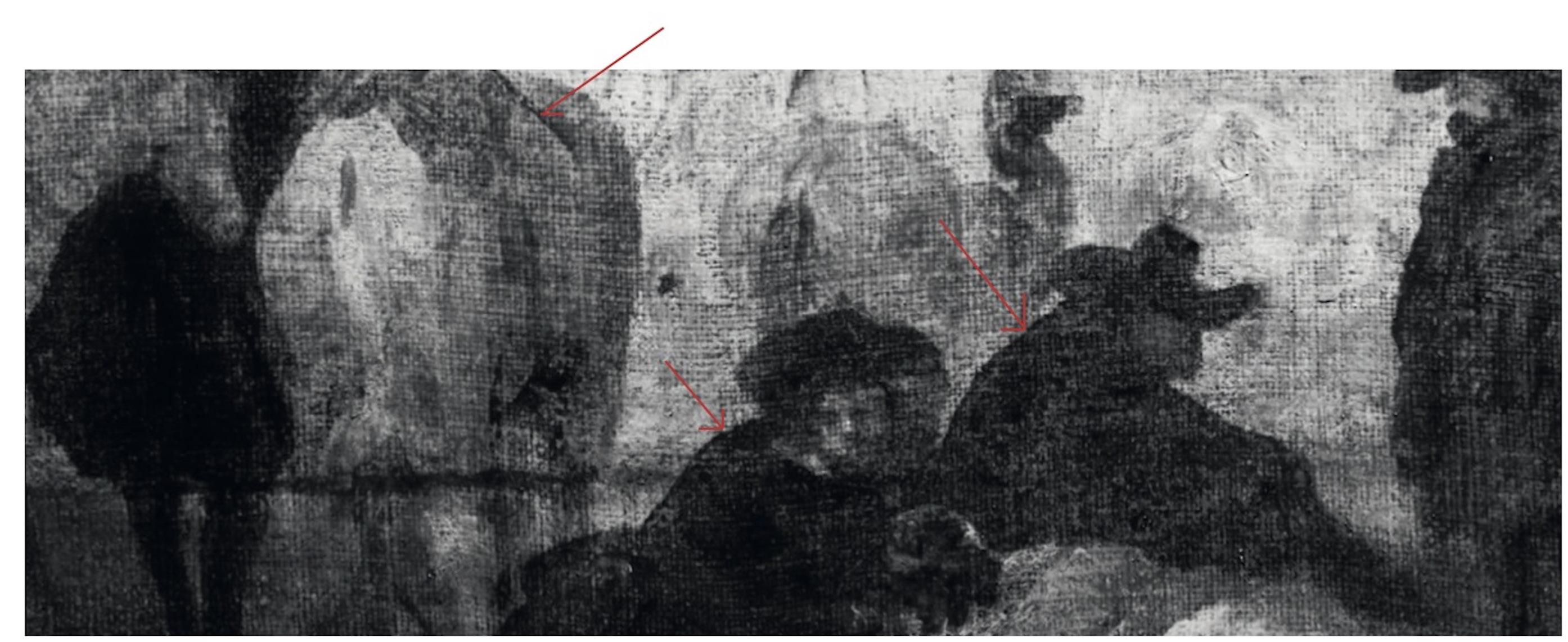

-Numerous signifcant pentimenti are present in the preparatory study, notably on the left: the tree trunk, the man in the black hat, and the group of three gentlemen. (See pp. 11–32 and pp. 58–83 of the book.)

-The preparatory study cannot be a copy of the National Gallery version, as the enclosure is not closed on the right, whereas it is in the fnal version.

This shows that Velázquez rethought the spatial relationship between the two compositions.

The fgure in the tree on the left of the canvas is painted in the opposite position to that in the National Gallery and has not yet unfolded his fabric.

-It is worth noting the many differences in the characters’ clothing, their placement in the painting, and the landscape which, also appears more impressionistic in the preparatory study.

-Presence of an early copy of the preparatory study in the Wallace Collection: if there is a copy, there must be an original—ours.

The painterly quality of the preparatory study is remarkable. The paint is applied fuidly, displaying subtle atmospheric effects and a masterful handling of transparency through the use of highly diluted pigments, typical of Velázquez in the years 1634–1635.

“The blues, diluted like watercolors, are characteristic of Velázquez after his return from Rome.”

(Cf. Brown, Jonathan & Garrido, Carmen, Velázquez: The Technique of Genius, Yale University Press, 1998).

The scientifc examinations of the preparatory study are consistent with those of other works by Velázquez from the years 1634–1635.

-Pigments are the same as those employed by Velázquez during this period (see the pigment analysis fle carried out by R.M.S. Shepherd Associates, p. 90 of the book).

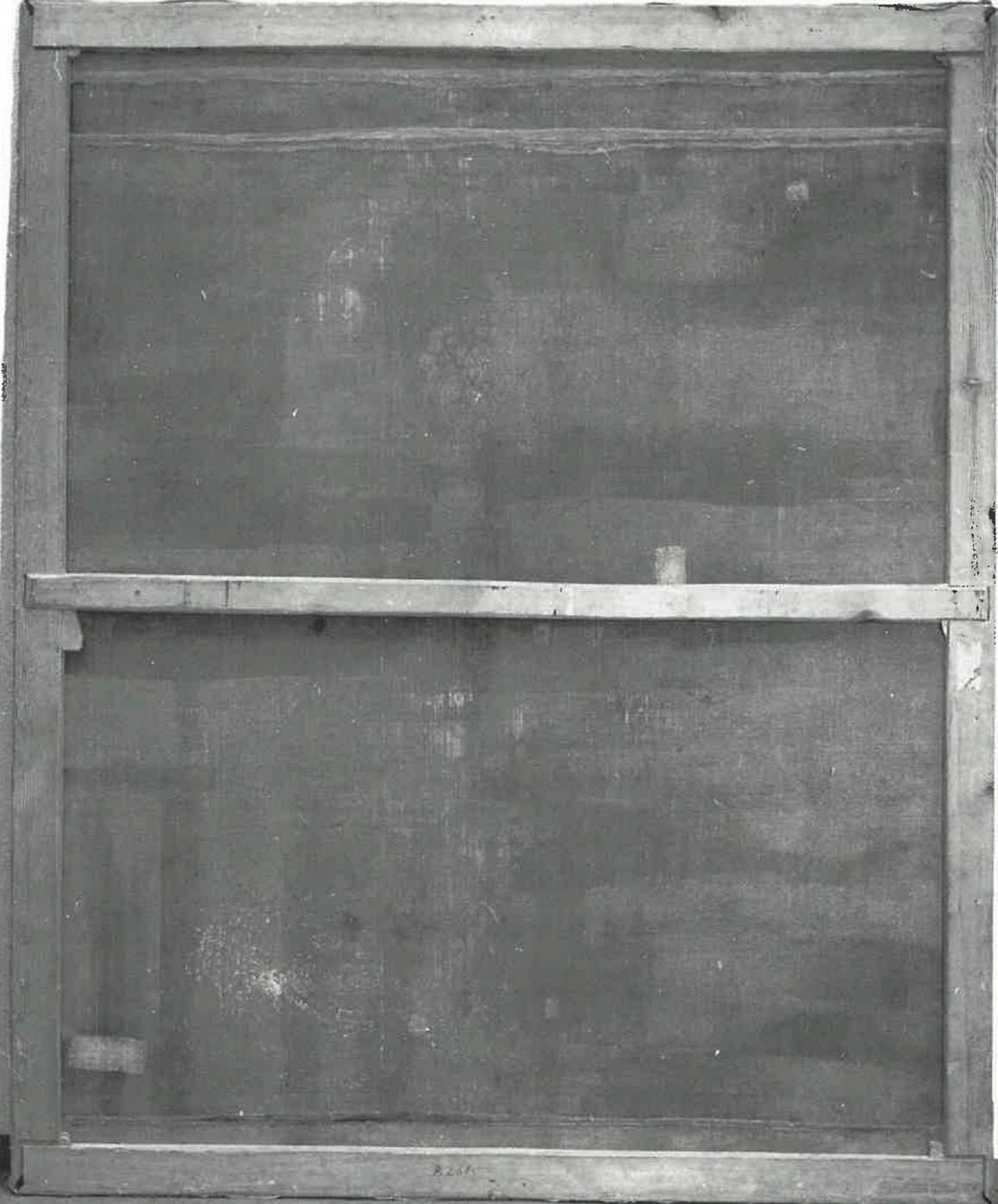

-Ground preparation is lead white–based, as always for Velázquez’s pictures after 1630. This explains the limited visibility of the paint layer under X-radiography, making the upper paint layers almost invisible—particularly since Velázquez used a very fuid paint with little body.

-Radiography shows that the preparation of the canvas was applied using a large fat spatula or knife, characteristic of Velázquez’s method of preparing his canvases.

It reveals also enlargements of the main canvas in length, visible on each side of about 1.5 cm (pp.80 and 62). This same practice of enlarging the main canvas during the creative process is also found, among others, in the painting Baltasar Carlos on Horseback (1634 - 1635), preserved in the Museo del Prado. This is explained in the work of Garrido Pérez, María del Carmen, Velázquez: técnica y evolución, Madrid: Museo del Prado, 1992, pp. 344–345: «The painting Baltasar Carlos on Horseback is one of the rare works by Velázquez preserved without having been relined. The original addition, made with the same canvas and located in the upper part, was added at the time of creation for compositional purposes. It measures approximately 11 cm». A copyist, of course, would not need to enlarge his canvas.

Velázquez, Baltasar Carlos on Horseback, oil on canvas, 16341635, Museo del Prado.

Verso of Baltasar Carlos on Horseback, showing the 11 cm upper enlargement executed by Velázquez during the creative process.

11 cm upper enlargement of the canvas executed by Velázquez

In accordance with Velázquez’s usual pictorial technique, no underlying preparatory drawings are found in our painting. Here, as in his other works from the years 1634–1635, Velázquez develops his forms progressively, sometimes correcting the contours or integrating the ground and underlayer into the composition (pp. 76–79 of the book). His fgures emerge primarily through the juxtaposition of colored areas rather than through precise linear outlines.

Velázquez frst painted the sky, then the landscape, and fnally the fgures. (pp.62 - 65 of the book)

Velázquez, Baltasar Carlos in the Riding School, oil on canvas, circa 1636, 144 × 96.5 cm, Collection of the Duke of Westminster

This creative process is inconceivable for a copyist who reproduces a fnished painting, without ever, of course, going through the same successive stages of creative progression.

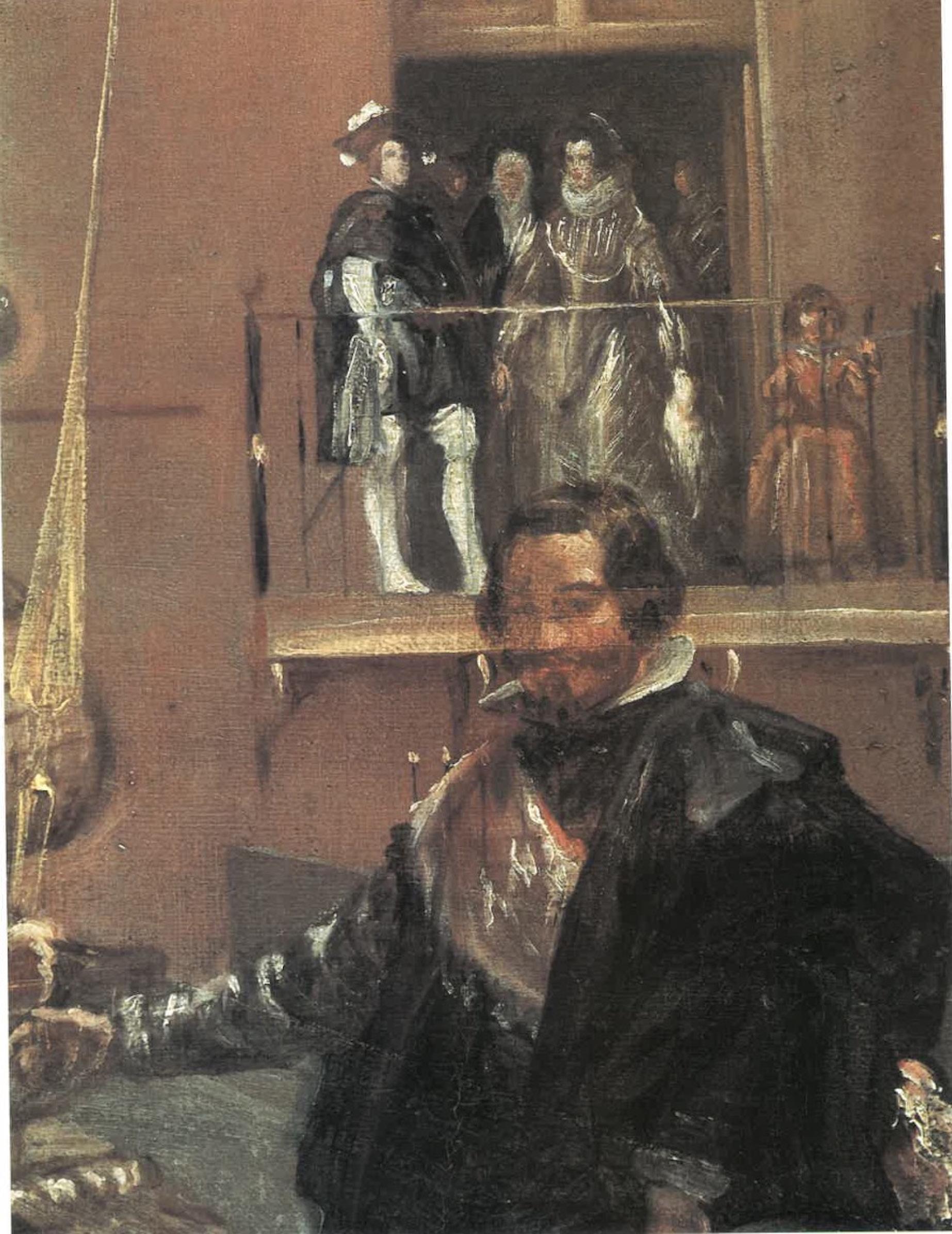

This creative process (painting the sky frst, then the landscape, and fnally the fgures) is very explicit in the painting Baltasar Carlos in the Riding School, oil on canvas, circa 1636, belonging to the collection of the Duke of Westminster.

Detail of the painting Baltasar Carlos in the Riding School. The sky, with its clouds, was painted before the landscape. Over time, the clouds have reappeared in transparency along the entire length of the roof.

The landscape, with its buildings, was painted before the fgures; this is evident throughout, and particularly visible through the face of Don Gaspar

If the preparatory study is not by Velázquez, then the painting in the National Gallery which derives from it is not by him either. Conversely, the preparatory study — which itself has every reason to be by Velázquez — further reinforces, though it has absolutely no need to, the attribution of the National Gallery painting to Velázquez.

The fact that, until now, no complete preparatory study has been found for an important royal commission painting does not mean that Velázquez did not paint any.

It is highly improbable that Velázquez did not conceive this preparatory study to be shown to the king before executing a painting over three meters length, commissioned by the sovereign and intended by him for the decoration of the Gallery of Kings in the Torre de la

Parada. It is historically established that such complete preparatory studies did exist for royal commissions (cf. p. 9 of the book); Velázquez merely followed the practice of Rubens, after they had infuenced each other in Madrid in 1628–1629.

“Velázquez made bocetos as a preparatory stage in the execution of royal portraits.”

(Miguel Falomir Faus, Javier Portús Pérez, M. Dolores Gayo, and Jaime García-Máiquez, Velázquez’s Philip III, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, 2017).p.40

Soldier at the far right of the painting The Surrender of Breda and detail of the Portrait of a Man

There are studies for portraits that are sometimes part of large composition ; there is no reason why the same should not apply to major complete paintings whose subject requires a detailed preparatory study.

An exhibition bringing together Velázquez’s preparatory studies would offer an exciting opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of his creative process and would thus make it possible to better distinguish the fully authentic works from those produced in collaboration, as well as from the works of assistants or followers. It could present the preparatory head studies already mentioned above for major paintings of royal or papal commission, as well as the rare drawings attributed to Velázquez and, fnally, our painting, which appears to be the frst complete preparatory study identifed in relation to a major painting of royal commission.