EDUCATI N

The magazine of the Virginia Education Association

As DEI comes under attack, it’s time to C.A.R.E. about belonging, for both educators and students.

• Hats off to our ESPs! u pg.12

• A code of ethics for the education profession. u pg.14

• VEA staffers talk about moving out of classrooms and into UniServ offices. u pg.16

As DEI work comes under attack, it’s time to C.A.R.E. about belonging, for both educators and students.

4-7 This month: Digital freedom, the importance of teammates, what we really do, and Touching Base With Pam Blair of Wythe County.

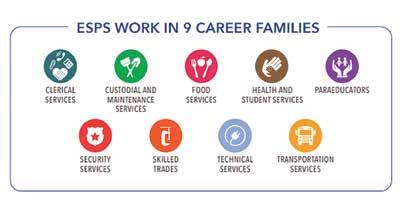

12 Hats Off to Our ESPs Often uncelebrated, they’ve always been an indispensable part of public education.

14 Our Definitive Guide and Standards A code of ethics for the education profession.

16 Getting a Move On VEA staffers talk about their transitions from our state’s classrooms to UniServ offices.

20 Membership Matters Summer far from leisurely for VEA members and advocates.

24 Insight on Instruction Be a helping hand for your rookie colleagues.

30 First Person The Mayfly Project: Angling to help foster kids.

“My grades are in the tank. Can you give me a shot of artificial intelligence?”

Editor

Tom Allen

VEA President

Carol Bauer

VEA Vice President

Dr. Jessica Jones

VEA Executive Director

Dr. Earl Wiman

Communications Director

Kevin J. Rogers

Graphic Designer

Lisa Sale

Editorial Assistant/Advertising Representative

Kate O’Grady

Contributors

Pam Blair Vickie Kitts-Blevins

Ty M. Harris Toney L. McNair, Jr.

Missy Alexander Andy Thompson

Alice Willingham

Vol. 118, No.1

Copyright © 2025 by the Virginia Education Association

The Virginia Journal of Education (ISSN 0270-837X) is published six times a year (October, November, December, February, April and June) by the Virginia Education Association, 8001 Franklin Farms Drive, Suite 200, Richmond, VA 23229.

Non-member annual subscription rate: $10 ($15 outside the U.S. and Canada). Rights to reproduce any article or portion thereof may be granted upon request to the editor. Periodicals postage paid in Richmond, VA.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Virginia Journal of Education, 8001 Franklin Farms Drive, Suite 200, Richmond, VA 23229.

Article proposals, comments or questions may be sent to the editor at tallen@veanea.org or Tom Allen, 8001 Franklin Farms Drive, Suite 200 Richmond VA 23229 800-552-9554.

Member: State Education Association Communicators

VEA Vision:

A great public school for every child in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

VEA Mission: The mission of the Virginia Education Association is to unite our members and local communities across the Commonwealth in fulfilling the promise of a high quality public education that successfully prepares every single student to realize his or her full potential. We believe this can be accomplished by advocating for students, education professionals, and support professionals.

“I should be an astronomer—lots of people say I’m really good at staring into space.”

“Can I move to the back row since it’s a wi-fi hot zone?”

Think you could do it? Maybe, maybe not—but some Florida fifth-graders did. They faced a daunting challenge: a threeweek digital detox. The rules? No phones, computers, or video games, and only a couple hours of television daily, with the stipulation that they turn it off an hour before bedtime.

Participation for the 19 students at KLA Academy in Miami who tackled the detox was voluntary, and here are some of their comments, recorded during and after the 21 days:

• “I’m a kid and I’m supposed to be having interactions with my family and my dad told me he felt more connected to me.”

• “I should remember this moment in time because devices and technology are just gonna keep growing.”

• “Patience? I don’t have patience for anybody.” (Day 4)

• “I feel like I was so much sadder on my screen and without my screen, I got so much better sleep. And I was so involved with my friends and I felt like we were more connected.”

• “It’s amazing how three weeks can change your whole life.”

• “I miss my iPad every single five seconds.” (Day 9)

• “I started a book— a book from my house. I would have never done that if I had my iPad. Like I started a book? That is so weird for me to start a random book on a random day.”l

“One thing in your favor, with these grades you can’t possibly be cheating.”

Father to son, looking at the youngster’s report card

“There’s a special meeting at school this week—just you, my teacher, and the principal.”

Son to father, handing him a notel

Cell phones, laptops, and tablets come with some inherent dangers for young people. So does driving a car. You have to have a license to get behind the wheel, and now some schools are experimenting with a “digital driver’s license” to better prepare their students to navigate the information superhighway.

In a pilot program at one Wisconsin middle school, students get a 45-minute class on how to manage their cellphones, laptops, and tablets very early in the school year, and then must pass a test before they’re allowed to use school-issued devices or bring a cellphone to school.l

What’s something you like about your job?

The best aspects of teaching in a socio-economically and racially homogeneous area are giving kids fictional literature that exposes them to perspectives, scenarios, and imaginary escapes they might never otherwise experience. It’s a great way to empower them by teaching them to write to specific audiences so their voices can be heard. I’m now in my 23rd year teaching, coaching, and sponsoring clubs, and I enjoy it as much as ever.

How has being a VEA member helped you?

Being a WEA/VEA member has kept me informed of legislation that affects my colleagues and me, which enables me to both question decisions and advocate for others. Membership has also given me a web of connections with expertise and support for any issues that teachers face, and an avenue for change with this platform being involved at all levels of education, from tiny counties like Wythe to leaders in our capital. l

The Virginia Department of Education has identified the five top critical shortage teaching areas in our state as:

1. Elementary education PreK-6

2. Special education PreK-12

3.

“Mrs.

“Virginia’s leaders don’t strive for a middling commitment to economic development, transportation, law enforcement or any other government responsibility that shapes the state’s quality of life. But the middle is precisely where the commonwealth lands in a new national ranking of teacher salaries—signaling a need to expand major initiatives in recent years to boost classroom pay… The average pay in the state last year… ranks 26th in the nation, one spot lower than a year ago and about $5,700 below the national average…pay should be a priority because everything else that happens in the state — from economic development to job growth to crime rates — is heavily influenced by education, giving the commonwealth an enormous return on that investment. A middling effort is not acceptable and Virginia can do better."l —from a May editorial in the (Newport News) Daily Press and (Norfolk) Virginian-Pilot

Teachers had mixed feelings about the use of artificial intelligence in the classroom in a recent Gallup survey, with almost two-thirds using it in some way and saying it’s a time-saver, while more than half believe AI will decrease students’ independent and critical thinking.

More than a quarter (28 percent) of the 2,200 teachers surveyed oppose using AI tools, while among users the most popular tools are for making worksheets and other assignments; creating assessments and quizzes; and completing administrative tasks.l

“We’d be in a much better place if national leadership were helping Americans see the situation this way: Our public schools are trying to do something unprecedented—enable every child, regardless of race, social class, or income, to succeed in a century transformed by technology and new global challenges. We all share responsibility for what the schools are today; we are all responsible for making them better. We can cheer their achievements, reward initiative and improvement, provide the resources to help them flourish, and, yes, expect them to recognize their shortcomings and improve.

Public education is especially worth supporting now, when we are so divided and dialogue across political lines is so fraught. It’s where people with different values and beliefs rub shoulders and learn to live together as productive, contributing citizens. It’s a bedrock of democracy that’s worth securing."l

— Michael V. McGill, former superintendent of the Scarsdale, NY Public Schools and author of Race to the Bottom: Corporate School Reform and the Future of Public Education

Nothing is more important to a successful and productive workplace than employee happiness. But what’s most important when it comes to making people like their jobs? Well, according to a poll taken on LinkedIn and X (formerly Twitter) by Tamara McCleary, CEO of the marketing firm Thulium, the answer is clear:

• A close work friend I trust — 8%

• Career growth & advancement — 13%

• Competitive compensation — 19%

• Positive team culture — 60%l

As work in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) comes under attack, it’s time to C.A.R.E. about belonging, for both educators and students.

by Ty M. Harris

Just eight months ago, I received the most incredible validation of my life’s work to date. Education Week recognized me as a “2025 Leader to Learn From” for my work involving equity. The timing turned out to be rather ironic: In the period between

the editors’ notice and the official announcement, diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) came under attack. By the time the article was published, attempts to remove DEI were well underway.

During those attempts, I’ve sought out silver linings. I’m grate -

ful to have some familiarity with the opponent we face, which isn’t a person, but apathy disguised as civility. This adversary equates silence with neutrality and believes that sameness is synonymous with fairness. It confuses comfort with courage. Those of us who have been working to promote equity—the idea that every student is worthy of getting what they need to succeed—were not surprised by these developments, but we are disheartened and frustrated, as this has long been a challenge in education. Just when we thought we were truly beginning to make progress, we’ve been forced into retreat. So, the struggle continues. I find solace in knowing that progress is still possible. But how do we begin? How can we succeed in our mission to truly serve all students and staff when many strategies and techniques are considered “questionable”? What is preventing people from feeling heard, valued, and respected? What prevents students from taking risks or families from getting involved? The short answer: absence of a sense of belonging, the root cause of a problem plaguing many of us at some point. Belonging is an essential human need, as primary to our well-being as food and shelter. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs specifies it as core to psychological health, citing its significance for self-esteem and self-actualization. Without a sense of belonging, we can experience feelings of loneliness, isolation, and even depression. While many articles recognize the importance of belonging, they often fail to provide concrete steps for achieving it. And, while typically there is a heavy emphasis on students, we cannot forget that adults also need to feel a sense of belonging, not only for their

peace of mind and well-being, but to be able to extend grace to students.

The Rising Tide Three years ago, my office, then called the Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, created the T.I.D.E. (Togetherness through Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity) Coalition in Virginia Beach City Public Schools, a community of practice made up of students, staff, and community members. This was in response to survey data suggesting that a sense of belonging was a concern in our secondary schools. T.I.D.E. students reviewed data with administrators, then identified at least one action they could take to improve their peers’ sense of belonging. Research by experts including Dana Mitra and John Hattie routinely shows that belonging improves when students are involved, so we took the approach of elevating student voice to identify challenges and allowing them to participate in finding solutions. Far too often, we fail to include students in discussions that directly impact them. It didn’t take long for students to implement some of their ideas, and within one year, the number of students who felt a sense of belonging in their school rose by over 10 percent. Additionally, students shed some light on why more than half of their peers reported not feeling a sense of belonging at their school. A standard narrative emerged: adults often act as bystanders rather than upstanders, meaning adults don’t always intervene when they witness behaviors detrimental to a positive school culture. This was all happening at light speed, so we decided to slow down, catch our breath, and dig deeper. We hosted a workshop for

division and school leaders to find a way to enhance everyone’s sense of belonging. This led to a new framework to guide our efforts, the C.A.R.E. (Connection, Achievement, Responsiveness, Engagement) Continuum.

The C.A.R.E. Continuum is an exciting pathway to develop a division-wide approach for addressing belonging. This year, we are introducing the framework to students in the T.I.D.E. Coalition, while also exploring themes with a new group of stakeholders called the C.A.R.E. Collaborative, made up of students, teachers, administrators, parents, central office staff, and a school board member. We are committed to ensuring that everyone understands that they matter.

I know “equity” gets tossed around a lot, but let’s be real: you can’t have true belonging if you’re not making space for everyone, especially those who are often left out. So, we’re keeping equity front and center. It’s not just a box to check; it’s the backbone. Here’s what C.A.R.E. is all about:

Crucial Connection

Connection is how humans achieve a sense of belonging. For adults, connection is about much more than just being on campus or in faculty meetings together. It’s about genuine relationships; the kind built on trust or a shared laugh in the hallway. Belonging isn’t just signing your name on a duty roster. It’s looking around the classroom or the staff room and knowing, “These people have my back.” When you feel connected to others, firm bonds are established.

Those bonds are forged and fortified through shared experiences. When individuals or groups navigate challenges, celebrate successes, or engage in everyday activities, they create a collective history and a shared identity. Amazing things happen in those shared experiences. I think about the challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, the uncertainty of it all, a collective wondering about what was happening. Then, pulling together to hand out computers, prepare packets, or create virtual lessons. After a few months, the focus shifted to preparing the building space for reduced capacity or placing stickers throughout to remind people to maintain a six-foot distance. We did that together, and I’m sure everyone has a few poignant stories to tell. These moments, big and small, become the inside jokes and war stories that bond a team. Suddenly, it’s not just “my class” or “your department,” it’s “ our school.”

Ultimately, the emotional core of belonging is the profound feeling of being understood and valued. Genuine connection flourishes when we feel safe expressing our authentic selves without fear of rejection. When our perspectives are heard, our feelings are validated, and our contributions are recognized, we feel seen and appreciated for who we are. This affirmation solidifies our place within the group, confirming that our presence matters.

Connection is not a passive state but an active, relational process. By cultivating meaningful relationships, participating in shared experiences, and fostering an environment where individuals feel understood and valued, we build the bridges that lead to genuine belonging. It is through these vital connections that we satisfy one of our most profound human needs, providing the stability required to thrive.

While we often discuss student achievement, what about the adults who support them? Achievement isn’t just about test scores or gold stars for perfect attendance. For teachers and leaders, it’s about setting goals with your team. It could be rolling out a new curriculum or just getting through a week without losing your sanity, and then making it happen. That shared victory? It’s like winning the Super Bowl. Everyone gets a little swagger in their step. Achievement, while often viewed as an individual pursuit, is a powerful catalyst for fostering a deep sense of belonging, which can be understood through Maslow’s research. Achievement solidifies our place within a group by fulfilling our higher-level needs for esteem. After our physiological and safety needs are met, we seek love and belonging. Directly above this is the need for esteem, which includes self-respect, confidence, and recognition from others. Achievement is the primary vehicle for satisfying these esteem needs. When we feel competent and respected, our sense of belonging transitions from simple association to secure, meaningful membership. We no longer question if we belong; we think we have earned our place.

In Belonging Through a Culture of Dignity, Floyd Cobb and John Krownapple introduce an important concept called the belonging gap: The incorrect notion that people have to achieve before they’ll be accepted. As someone who routinely felt like I didn’t belong until I won a race or scored a touchdown, I fully agree that it happens far too often.

The more I dug into the research, however, the more I found that it doesn’t have to be that way. Achievement can lead to a greater sense of belonging. Here are some examples to illustrate my point.

• Goal-setting as a team: When your grade level or department sets out to crush a big goal together, you build a story. You may be revamping the reading program or organizing a school carnival that doesn’t end in chaos. When you pull it off, you don’t just bond over the results; you bond over the journey.

• Feeling competent: There’s nothing like finally mastering a new teaching strategy or figuring out how to utilize new tools in Canvas. When you feel competent, you transition from being just another teacher in the building to being “that teacher,” the one everyone turns to for help.

• Recognition matters: Let’s be honest, everyone wants a little recognition. You may get a shoutout at the staff meeting, a note from a student, or someone may bring you a cupcake just because. Those moments are like tiny Oscars for the work you do every day. It’s proof that your effort isn’t invisible.

• Making a difference: The best feeling? When you know what you’re doing matters to students, to colleagues, to the whole school vibe. Maybe it’s the student who finally “gets it,” or the new teacher who survives their first semester because you had their back. Those contributions are what weave your story into the school’s bigger narrative.

Achievement is the receipt that says, “Yep, you belong here.” It’s what makes your role in the school real, not just a paycheck, but a piece of the heart of the place. That’s how you go from just showing up to being part of something worth coming back to.

Belonging doesn’t come overnight because you put a “Welcome” sign on the door. It’s built day by day, based on consistency and actual responsiveness.

Imagine a student who finally works up the courage to tell you they don’t understand the material, or a colleague who tells you they feel left out of the planning committee. If you dismiss their problem as them just being needy, then you’re missing the point. But if you pause, listen, and take action, such as redistributing their load or bringing them in, you realize why it’s so important. That kid or co-worker suddenly has that feeling of, “Hey, I matter here. My voice isn’t background noise.” It’s like a move from the sidelines to center stage in your own High School Musical moment. Suddenly, everyone is in this together. This trust fosters a sense of being supported. Knowing you can raise a concern without fear of rejection or punishment is a safety net.

Additionally, a thoughtful response is an opportunity to express empathy. If your colleague tells you that she’s burning out or if your student is stressed out about exams, don’t just say “Hang in there!” and push it off. Approach them, ask them how they’re doing, and maybe share a time when you experienced the same thing. That’s what breaks

barriers. Lastly, these interactions result in the profound understanding that people care. Responsiveness is the most substantial evidence of care. It is the knowing that you are not a number or a title, but an individual of worth whose voice is heard.

This feeling of being cared for is the key to feeling a sense of belonging. When the culture of the building means worry is met with a response, help is consistent, and compassion is present, you have something special. Individuals will feel secure, appreciated, and genuinely part of something beyond themselves. What’s the old saying, “People won’t care how much you know until they know how much you care”?

Embracing Engagement

If responsiveness is the heart, engagement is the spark. You can’t simply hope students or teachers will feel like part of the team when they’re relegated to the sidelines. You have to bring them in, offer them tasks, and let them host the morning announcements, just like it’s their episode of Abbott Elementary (I love that show). Request suggestions, allow them to take things and run with them, and honor their victories.

When you do that, suddenly, the school becomes essential to everyone. They’re not passengers, they’re driving the bus. Belonging is built through meaningful engagement. This happens across several themes, beginning with participation. Simply being present somewhere is not sufficient; belonging flourishes when

one shifts from being an observer to a contributor.

Active participation is most potent when united around a common purpose. When people work together toward a shared objective, whether it is winning a championship, completing a project, or contributing to a community, their contributions become interdependent. Their common purpose coordinates their actions and incentives, creating a unifying force that transcends personality differences. As they strive together for this shared goal, an identity emerges. The “we” becomes more significant than the “I.” Individuals begin to see themselves reflected in the group’s identity, and the group’s identity as an extension of the self.

This shared identity is a powerful anchor, serving as the basis for belonging to a unique and recognizable group. When one’s work and contribution are welcomed and appreciated, it sends a compelling message: “Your presence and your effort are crucial to our success.” This acknowledgment serves as the emotional foundation of belonging.

A Call to Action Belonging is not merely a desirable state but a fundamental human need. By nurturing connection, fostering achievement, demon-

The author talks with high school students in Virginia Beach at an event called “Power of We” last December. There will be a similar gathering for middle school students this fall, co-facilitated by the Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities.

strating responsiveness, and promoting engagement, we can cultivate a stronger sense of belonging for ourselves and others. Prioritizing belonging in our relationships, communities, and institutions is essential for creating a more compassionate and thriving world.

Your method for addressing belonging, whether through the C.A.R.E. approach or one you develop locally, can’t just be a poster you hang up next to a faded “Hang in There!” kitten. It means listening, showing up, and making space for every story, not just the loudest ones. And it means facing the hard stuff as well. Because when students and teachers feel like they belong, you don’t just get better test scores; you get better humans. And at a time when educators seemingly need to pick their battles with caution, if that’s not worth fighting for, I don’t know what is.l

Ty M. Harris, Ed.S., a member of the Virginia Beach Education Association, is the director of the Virginia Beach City Public Schools Office for Opportunity and Achievement (formerly the Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion).

Photo by

Often uncelebrated, they’ve always been an indispensable factor in public education.

Our schools can’t function without them, something Virginia got a little taste of during the years of our state’s “support cap,” which limited their numbers until VEA members’ lobbying efforts eliminated it. We learned how essential the more than 2 million education support professionals (ESPs) that work in our country’s public schools are, where they do everything from driving

money to help students get classroom resources, go on field trips, or work on class projects. On average, they contribute $282 a year.

• They’re part of the community. Two-thirds of ESPs live in the school district where they work, and many of them volunteer in some capacity in those neighborhoods.

• They play a vital role in keeping our young people safe. Three-quarters of K-12 support professionals have responsibilities for ensuring student and staff safety.

• They’re experienced and committed. Nationwide, ESPs have been on the job in their area of work for 13 years; 65 percent plan to stay until retirement.

• They understand the importance of education. More than half of ESPs (57 percent) have at least an associate’s degree.

• Their workforce closely reflects the gender breakdown of the teaching force. Eighty-one percent of ESPs are female, compared with 77 percent for teachers.

students safely to and from school to keeping buildings clean and safe. They do more than that, too, as they address the needs of the whole student. ESPs work in a wide range of areas, shown in the “9 Families” graphic on the facing page. And they’re family to many of our students, too. Here are some facts about our ESPs from NEA research:

• They’re generous. More than 60 percent have spent their own

• Like teachers, they’re on the front line in our efforts to fight poverty’s effects on children. A majority of ESPs (55 percent) work in Title schools. ESPs are also there for children with special needs, as 62 percent are involved in their learning and care.

In addition, 49 percent of ESPs work as paraeducators; 43 percent serve in preschool, kindergarten, or in the elementary grades; 84 percent are on full-time schedules; and 65 percent

are paid an hourly wage.

Professional Growth

NEA believes that professional development is every bit as important for ESPs as it is for teachers, and delivers it through the union’s ESP Quality department. If you’re an ESP, here are a few ways you can improve your skills and build your effectiveness at serving your students and school community:

• Webinars. NEA’s ESP Learning Network offers regular webinars on a range of topics in both English and Spanish. You can also access previous presentations.

• Professional Growth Continuum. This is a framework of resources to help at every stage of your career, and is based on eight universal standards: communication, cultural competency, organization, reporting, ethics, health and safety, technology, and professionalism.

• Publications. Brochures, ebooks, and manuals are available on ESP topics, from bullying prevention to beating privatization.

• Peer mentoring. For ESPs, mentoring can be as essential as it is for teachers in helping you deal successfully with the growing complexity and increasing demands of education.

To learn more about these and other NEA learning opportunities, visit www.nea.org/professionalexcellence/professional-learning/ esps l

Stephanie Lovelace, a member of the Franklin County Education Association and a paraeducator for nearly 30 years, is VEA’s Education Association’s 2025 Education Support Professional (ESP) of the Year. About her long career in the classroom, primarily focused on special education, Lovelace says, “I wouldn’t change a thing. I have a special place in my heart for special need students.” Along the way, she’s sought out additional training and now holds numerous certifications in autism spectrum disorder, ranging from how to best help teach students with different types of autism to assisting such students in handling their feelings and controlling their emotions.

“Stephanie approaches every task with a positive attitude, demonstrating not only excellent organizational skills but also a compassionate and supportive presence for her students, says Vicki Craighead, assistant principal at Lovelace’s school, Lee M. Waid Elementary. “Her ability to engage with students in meaningful ways and provide support in the classroom environment is unmatched.”l

The National Education Association believes that the education profession consists of one education workforce serving the needs of all students and that the term ‘educator’ includes education support professionals.

TOGETHER WE’RE STRONGER.

TOGETHER WE’RE HEARD.

With more members like you, we’ll have a stronger collective voice that can help educators live better lives, so our students get the best education possible.

The educator, believing in the worth and dignity of each human being, recognizes the supreme importance of the pursuit of truth, devotion to excellence, and the nurture of the democratic principles. Essential to these goals is the protection of freedom to learn and to teach and the guarantee of equal educational opportunity for all. The educator accepts the responsibility to adhere to

the highest ethical standards.

The educator recognizes the magnitude of the responsibility inherent in the teaching process. The desire for the respect and confidence of one’s colleagues, of students, of parents, and of the members of the community provides the incentive to attain and maintain the highest possible degree of ethical conduct. The Code of Ethics of the Education Profession indicates the aspiration of all educators and provides standards by which to judge conduct.

The educator strives to help each student realize his or her potential as a worthy and effective member of society. The educator therefore works to stimulate the spirit of inquiry, the acquisition of knowledge and understanding, and the thoughtful formulation of worthy goals.

In fulfillment of the obligation to the student, the educator:

1. Shall not unreasonably restrain the student from independent action in the pursuit of learning.

2. Shall not unreasonably deny the student’s access to varying points of view.

3. Shall not deliberately suppress or distort subject matter relevant to the student’s progress.

4. Shall make reasonable effort to protect the student from conditions harmful to learning or to health and safety.

5. Shall not intentionally expose the student to embarrassment or disparagement.

6. Shall not on the basis of race, color, creed, sex, national origin, marital status, political or religious beliefs, family, social or cultural background, or sexual orientation, unfairly:

a. Exclude any student from participation in any program

b. Deny benefits to any student

c. Grant any advantage to any student

7. Shall not use professional relationships with students for private advantage.

8. Shall not disclose information about students obtained in the course of professional service unless disclosure serves a compelling professional purpose or is required by law.

The education profession is vested by the public with a trust and responsibility requiring the highest ideals of professional service.

In the belief that the quality of the services of the education profession directly influences the nation and its citizens, the educator shall exert every effort to raise professional standards, to promote a climate that encourages the exercise of professional judgment, to achieve conditions that attract persons worthy of the trust to careers in education, and to assist in preventing the practice of the profession by unqualified persons.

In fulfillment of the obligation to the profession, the educator:

1. Shall not in an application for a professional position deliberately make a false statement or fail to disclose a material fact related to competency and qualifications.

2. Shall not misrepresent his/her professional qualifications.

3. Shall not assist any entry into the profession of a person known to be unqualified in respect to character, education, or other relevant attribute.

4. Shall not knowingly make a false statement concerning the

qualifications of a candidate for a professional position.

5. Shall not assist a noneducator in the unauthorized practice of teaching.

6. Shall not disclose information about colleagues obtained in the course of professional service unless disclosure serves a compelling professional purpose or is required by law.

7. Shall not knowingly make false or malicious statements about a colleague.

8. Shall not accept any gratuity, gift, or favor that might impair or appear to influence professional decisions or action.

Adopted by the NEA 1975 Representative Assembly.l

These principles, adopted by delegates to the 2006 NEA convention, guide our work and define our mission:

Equal Opportunity. We believe public education is the gateway to opportunity. All students have the human and civil right to a quality public education that develops their potential, independence and character.

A Just Society. We believe public education is vital to building respect for the worth, dignity and equality of every individual in our diverse society.

Democracy. We believe public education is the cornerstone of our republic. Public education provides individuals with the skills to be involved, informed and engaged in our representative democracy.

Professionalism. We believe that the expertise and judgment of education professionals are critical to student success. We maintain the highest professional standards, and we expect the status, compensation, and respect due all professionals.

Partnership. We believe partnerships with parents, families, communities, and other stakeholders are essential to quality public education and student success.

Collective Action. We believe individuals are strengthened when they work together for the common good. As education professionals, we improve both our professional status and the quality of public education when we unite and advocate collectively.l

Photo by iStock

VEA staffers talk about their transitions from our state’s classrooms to UniServ offices.

Several members of VEA’s UniServ staff came into those positions directly from doing union work as members and serving as leaders in their locals. We asked some of them about that career transition, and here’s what they had to say:

MELISSA “MISSY”

ALEXANDER

Mountain View UniServ

TELL US ABOUT YOUR CAREER IN VIRGINIA SCHOOLS.

I spent 18 years as a secondary English teacher: seven years in Fairfax, five in Prince William, one in Manassas Park, two years on a leave of absence as I cared for my daughter while she battled pediatric brain cancer, and I also spent three years at Trinity Christian School in Fairfax.

HOW WERE YOU INVOLVED IN VEA WORK AS A MEMBER?

I’ve been a VEA member since the 2004-05 school year but didn’t get involved as a leader until 20192020. That year, I ran for executive board secretary, and for the next two years was incredibly active, leading advocacy campaigns during the COVID-19 pandemic. My union siblings and organized rallies and advocated before county leadership and the school board to ensure the safety of our colleagues during such an unprecedented time.

WHEN DID THE IDEA OF VEA STAFF APPEAR ON YOUR RADAR?

In 2021, I was nominated for and accepted into the NEA Pre-UniServ Program and graduated that spring. After that, I knew I wanted to

transition to staff and serve my colleagues in that capacity.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY ABOUT BEING ON STAFF?

I adore working with our members and helping grow them as leaders. While assisting employees with member rights cases is rewarding, there’s nothing like the joy of seeing a leader learn and evolve. have members who have gone from barely knowing Robert’s Rules to serving on the VEA executive committee in my three years as their UD, and that makes me a proud Mama Bear.

Cumberland Mountain/ Southwest Virginia

TELL US ABOUT YOUR CAREER IN VIRGINIA SCHOOLS.

I was a business education teacher at Honaker High School in Russell County Public Schools for 11 years, including three as an administrator. I couldn’t have asked for a better place to work. Honaker’s staff are still like family, and students whom I still call my kids to this day, many of whom are now educators and members themselves.

I served in various roles while a member of the Russell County Education Association, eventually becoming president. During my time in governance, I sought to learn as much as possible about VEA and how to be an effective member and leader for my local. I was a delegate to the convention each year, attended lobby days, instructional conferences, the Local Officers

Retreat, and the Reggie Smith Organizing School, and was also a member of the Professional Rights & Responsibilities Committee.

WHEN DID THE IDEA OF VEA STAFF APPEAR ON YOUR RADAR?

When longtime UniServ Director Doris Boitnott began considering retirement, she started intentionally acclimating me to her work. This was part of Doris’s giftedness in being able to walk side-by-side with anyone along their journey, providing them with the information and encouragement they needed.

HOW DID THAT TRANSITION HAPPEN?

Doris retired and, sadly, passed this past January. I will never fill her shoes, but I’m thankful for all she taught me and the connections she facilitated that helped make my transition much easier. My daughter, Hannah, graduated from Honaker High in 2020, and it was a perfect time for me to “graduate” from Honaker High as well.

As a former member and local leader, have special insight and relatability into the roles they play that others who don’t come from the governance side of an education union may not have. Working for an organization with diverse individuals and diverse perspectives has been great. I continually learn from them in the work we do, as well as from their experiences as they live their

lives. I couldn’t stay away from serving in a leadership capacity, so I currently serve as president of one of VEA’s staff unions, the Virginia Professional Staff Association.

ANYTHING ELSE?

Get involved in your local union. You are the Union! Attend district and state events. Every member has a UniServ Director that is just a phone call or email away to ask for assistance with employment matters, but also for more information on how you can get involved, events, professional development opportunities, member benefits, and other information. Tap into their knowledge. If we don’t know the answer, we’ll connect with each other, other VEA departments, and elsewhere to assist you.

DR. TONEY L. MCNAIR, JR. Tidewater UniServ

TELL US ABOUT YOUR CAREER IN VIRGINIA SCHOOLS.

I began as a long-term substitute high school choral director, and, after two months on the job, I was offered a regular contract for the next school year. I then spent three years in Portsmouth and the rest of my 21 years of teaching in Chesapeake, working

as an elementary general music teacher, and a middle and high school choral director. The highlight of my teaching career was being named the 2017 Virginia Teacher of the Year. I most enjoyed my engagement with students from diverse cultural backgrounds. I got to spend time shaping and molding students in other areas besides music. Some of my students have successful professional careers and some are in the teaching profession, attributing this to the experiences we’ve shared in my classroom.

I was recruited by my building rep in Chesapeake to replace her when she needed to give up the position to create time for graduate school. I became more engaged in VEA as I attended some of the statewide activities, including the Reggie Smith Organizing Institute, and eventually became a VEA trainer under Beblon Parks and Cheri James. I served as both president and vice president of the Chesapeake Education Association, as District N president, and a VEA Board member.

WHEN DID THE IDEA OF COMING ON VEA STAFF APPEAR ON YOUR RADAR?

One year prior to COVID-19, based on the number of issues and concerns that were coming up in my school division, the idea circulated in my mind to consider becoming a UniServ Director. I was CEA president at the time and we’d been without a UD for over a year. During that time, VEA’s then-Director of Field Support and I dealt with these concerns.

When the pandemic hit, teaching middle school choral music was an extreme challenge since we were “sheltered in place.” My current position with the Tidewater UniServ Council, which covers Portsmouth and Suffolk, was open. I applied for it and here I am!

I enjoy my work with educators as they learn to advocate for their rights and gain a sense of dignity in doing so. Educators who are successful in resolving some of their concerns while trying to provide a quality education for their students see the value of collaborative efforts with those who share the same values. I also enjoy working with my colleagues who bring diverse experiences to the job, making them highly qualified to assist educators in building their professional capacity and growing to be leaders.

I’m looking forward to new opportunities to grow professionally and expand my knowledge in my work. I’ve learned, served, and trained with some phenomenal professionals and groups, like the Harvard Kennedy School, labor legend Marshall Ganz, Organizing and Action, Leading Change, and Ellen Holmes with the NEA-UniServ Support Program. I’ve also learned and grown a lot from being an active member of the Virginia Professional Staff Association (VPSA), our professional staff union, where I serve as an executive board member and committee chair.

This would not have happened had not had the opportunity to serve as a UniServ Director.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR CAREER IN VIRGINIA SCHOOLS.

I began as a classroom aide and now my purpose in life is to aid those in the classroom (and the rest of the school). When I began my career in middle school, I was a fresh-faced 22-year-old, fresh out of Radford University, with only half a clue about what I wanted in life and an even less-defined idea of what career I wanted, if I wanted that at all. I sashayed into my hometown of Harrisonburg, wielding a degree in Physical and Health Education that was my ticket to a long and satisfying career. My confidence was shaken when I finally began teaching middle school health and physical education. Although was prepared with content and enthusiasm, I was ill-prepared for how needy and brutally honest middle school students could be. It took my first three years of teaching just to consider myself adequate, much less a master teacher. spent 29 years at

that same middle school, and I’d still hesitate to call myself a master teacher. Teaching is the most difficult job in the world to be great at!

I worked hard as a member of the Harrisonburg Education Association and became a leader in my building. I also became passionate about preserving educators’ autonomy and respect. Eventually, I became HEA president.

During my tenure as a local president, Virginia passed a bill giving public employees the right to collectively bargain their contracts, and this was my opportunity to really show up for my colleagues. I tirelessly recruited members and openly campaigned for better working conditions and pay. Our membership grew 25 percent, and HEA members are now on their way to using those bargaining rights. I realized then, as do now, that my passions had shifted, from bright-eyed students who have so much to learn to those who work endlessly to give those students every advantage.

ABOUT BEING ON STAFF?

The people that dedicate their lives to their communities and their most precious resource, their children, are worth fighting for! As VEA’s Valley Uniserv Director, I am older and wiser and the lines on my face should give school employees confidence about my hard-won knowledge and experience. I pledge to them that I will support and

defend all people who work to do what is morally and ethically right for public schools, students, and the soul of our nation.

Education has changed dramatically over the course of my career. Schools were once a place where learning was the main objective and parents were responsible for their child’s overall well-being. Now, most schools look like community centers that attempt to fill the void often left by parents, local churches, and underfunded social services. Schools now offer all types of services including medical care, psychological care, parenting classes, jackets for the needy, food for struggling families and community entertainment. However, the funding model for schools remains the same, as if nothing has changed over the last 30 years.

a former St. Mary’s County leader there, so I never worked in Virginia’s public schools, but I’m always amazed at how educators across the country all encounter similar challenges and triumphs. Teaching was extremely rewarding for me, and now I find that assisting teachers and other school staff members is even better as I’m able to help them be their best for their students.

The greatest part of what we do is empowering others to advocate for themselves. Members share their experiences and encourage others to organize around issues that make the education profession better for everyone.

WHAT DO YOU ENJOY ABOUT BEING ON STAFF?

I was a longtime member of the Maryland State Education Association and

Want to Learn More?

highly recommend that former educators, especially those with governance experience, consider becoming UniServ Directors. We are often the first people to provide guidance when our members are in crisis and need suggestions that will give them hope. I find that my past union activities and prior knowledge help me put members at ease and feel better about the circumstances they encounter. I try to offer options that they may not have thought of otherwise. And, as an experienced educator, you already have the skill set! The active listening, effective communication, ability to adapt, empathy, creativity, patience, organization, work ethic, advocacy, negotiating, lifelong learning, problem-solving, and critical thinking you demonstrate every day are all important parts of this work.l

If you have questions about UniServ or other VEA staff work, email vea.hr@veanea.org

VEA leaders and advocates had a hopping summer of 2025, traveling, training, learning, networking, and recruiting, both in and out of state. Here are some of the highlights:

• More than 100 VEA delegates went coast-to-coast to represent our state’s members at the NEA Representative Assembly in Portland, Oregon, where they joined over 6,000 of our colleagues from around the country. The convention included debate on new business items in six categories: Elevating the Professions and Advancing Student Learning; Ensuring Equity by Advancing Racial, Social, and Economic Justice; Growing Our Union; Demonstrating and Strengthening Democracy; Promoting Peace; and NEA Operations. NEA President Becky Pringle left delegates with seven key words to think about and aspire to: Educate, Organize, Mobilize, Litigate, Legislate, Elect, and Communicate, urging educators everywhere to “fight forward” instead of just fighting back. In addition, normal procedures were suspended so all delegates could spend a full day training on campaign strategies, tools, and resources to effectively stand up and speak out on behalf of our students, colleagues, and schools.

• Members gathered in Richmond later in July for three back-to-back events: Leadership Training, the Summer Organizing Institute, and the ESP Conference. Attendees had a wide range of workshops and hands-on activities to choose from, with topics running the gamut from Having a Vision for Your Local to Being Part of a Statewide Movement to NEA’s ESP Bill of Rights. They also heard from guest speakers including legislators, NEA’s ESP of the Year, and many of their colleagues.

• A VEA cadre took part in NEA’s Leaders for Just Schools annual conference in Baltimore, learning to advance racial and social justice in our schools and bringing back resources and ideas to share.

• And, in just about every school division in our state, members accelerated into late summer by reaching out to incoming colleagues at New Employee Orientation events, spreading the word about the work being done by our union and welcoming new members into the fold.l

Louisa County native Princess Moss, former VEA president and a former elementary school music teacher, announced her candidacy for president of the National Education Association at its convention this summer in Portland, Oregon. She’s currently NEA’s vice president, a position she was elected to in 2019 and then re-elected in 2022. Following her announcement, the VEA delegation to the NEA convention voted unanimously to support her campaign, which will culminate in an election at next year’s gathering in Denver.

Stay tuned in the months ahead for news from the campaign trail and for ways in which VEA members can support Princess.ll

Hard work and commitment have paid off for Portsmouth Education Association members, who have fought hard for two years, collaborating with both City Council and the Portsmouth School Board to make sure that school employees got significant and overdue improvements on payday.

As the new school year begins, all Portsmouth Public Schools employees got three well-deserved wins, thanks to PEA members’ efforts:

• They were placed on their correct step on the salary scale.

• They received a 3 percent raise in addition to the step adjustments.

• Any PPS employee who signed a contract for the 2025-26 school year by last June 2 got a minimum $2,000 retention bonus.

“This is more than a win,” PEA President Laura Hamilton told members, “It’s a promise kept. We pledged to fight for equitable compensation, and this ensures PPS educators are now among the highest paid in our region according to 2024–2025 market data.”

She acknowledges, though, that challenges lie ahead, as the school division faces a budget shortfall, but remains confident. “We are firm in our belief that investing in people is investing in students,” she says, “and this is proof of what we can achieve when we stand together.”ll

Ruby Dews, a school bus driver and longtime member of the Danville Education Association, was surprised with a plaque recently by the Danville campus of Rivermont Schools, which serves students with behavioral and educational challenges. The honor, presented by Principal Tia Hairston in recognition of her many (and ongoing) years of service to Danville Public Schools, read in part, “For your never-ending support of our students and school, your commitment, and your love. We appreciate you!”l

VEA-Retired members will hold elections in January for all Council positions, as well as delegates to the VEA and NEA conventions for the next two years. Petitions and nomination forms are available now; paperwork must be returned by December 15th, as voting will be held January 24-26, 2026. All the forms and details can be found at vea.link/retired-elections

Questions? Email vearetired@ veanea.org l

Nelly Henjes is a new UniServ Director in Fairfax. A former early education paraprofessional in Pinellas County, Florida, she later became president of the Pinellas County Educational Support Professional Association, leading negotiations for multiple collective bargaining agreements. She’s also participated in the NEA Organizing Fellowship Academy.

Sam Fenzel-Alexander has joined VEA as an Organizing Specialist in Hampton Roads, bringing experience in education, political campaigns, and union organizing, including his most recent work as a staff organizer with AFT in Hampton and his time as a sixth grade science teacher and worksite rep in Newport News.l

You’ve spent your career helping others; take some time now to check on your own financial future in the Virginia Retirement System. Track savings and review benefits using myVRS and your DCP Account, if applicable. Here’s how:

1. Project Your Future Income

Log in to myVRS at varetire.org/myVRS, and you’ll see your member contribution account, total service credit, retirement eligibility date, and any defined contribution plan account balances you may have. Use the Benefit Estimator there to run scenarios based on different retirement dates and payout options, and the Retirement Income Planner to set your income-replacement goal. If you’re in the Hybrid Retirement Plan or participate in Virginia’s 457 Deferred Compensation Plan, you can review balances, adjust contributions and access tools, calculators and other resources in your DCP Account at dcp.varetire.org/login

2. Spot Potential Savings Gaps

Your Member Benefit Profile, available each fall in myVRS, summarizes benefits as of June 30. Find it under My History in the menu, select Annual Statements, and choose the most recent year. Check “Your Target Income in Retirement” to see how your projected VRS income compares to the common goal of 80 percent of your current salary. Your VRS benefit alone is not meant to meet that goal, but you can see how your benefit fits into your broader financial plan, including Social Security and other savings.

3. Supplement Your Savings

Whether it’s your first year in one of Virginia’s public schools or your 41st, welcome to a new academic year and thanks for doing work of matchless importance to our future! There aren’t a lot of careers that you go home from each day truly feeling like you’re having an important impact. We are incredibly fortunate.

Longtime local leader, UniServ Director, lobbyist, advocate and VEA-Retired member Shirley George got a big national-shout in Portland at the NEA convention this summer, receiving NEA-Retired’s highest honor, the Distinguished Service Award. Earlier this year, she’d been presented the VEA-Retired Martha Wood Distinguished Service Award at the VEA convention, so to say it’s been a banner year for Shirley is quite an understatement. Both awards saluted her for 60 years of excellence and her “contributions to public education as an active and/or retired member in local, state, and national associations.” Many congratulations on a well-deserved honor, Shirley!ll

Check if your employer offers a supplemental savings plan, such as the Commonwealth of Virginia 457 Plan, which provides tax-deferred savings and payroll deductions. If you’re a hybrid plan member, consider setting your defined contribution plan voluntary contribution at 4 percent to receive the maximum 2.5 percent employer match. Make updates in your DCP Account, where you can also use SmartStep to schedule gradual, automatic increases until you reach the max. Determine how changing your contribution will affect your take-home pay at dcp.varetire.org/ make-a-plan.

NOTE: Keeping contact information current in your online account(s) helps ensure that VRS can reach you and that only you have access to your personal information. Review this information periodically. If you did not register for myVRS within 90 days of your hire date, VRS has locked your account for your protection. Call us at 888-827-3847 for assistance. For help with your DCP Account, contact the VRS Defined Contribution Plans Service Center at 877-327-5261.ll

You probably hear this a lot this time of year, but really do mean it from the bottom of my heart: I value and respect you and couldn’t be prouder to join you in the mission that is public education in these times.

I’m also honored to serve as your VEA president, because you make it what it is: not only a powerful labor union that protects the rights of educators, but Virginia’s largest and most effective advocate for public education. You’re part of an organization that takes a stronger stand for students and public schools more strongly than any other in the Commonwealth. That’s exciting!

I urge you to share that excitement with your colleagues who haven’t yet joined VEA. When we add to our numbers, we also add to our ability to spread the word on what our students and the school employees who work with them need to succeed. That’s good for everyone.

Another factor in our ability to get the resources our students and colleagues lack will be the outcome of this year’s statewide elections for governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and every member of the House of Delegates. More on this in next month’s issue, but suffice it to say that what happens at the polls in November will reverberate through our public schools for years to come. Stay tuned as VEA interviews candidates and recommends those who will support public schools—not just say they will.

All of this is part of our calling, which is about offering our kids the kind of public schools that make good on the American promise of equal opportunity for all. What our schools make possible is nothing less than the cornerstone of our democracy and the best hope for we have the kind of civic future we all long for.

As we move ahead, we have lots of work to do to arrive at that kind of future. We’ll do our part by making the new school year a most excellent one— the kind our students, colleagues, and communities deserve—and I wouldn’t want to be doing that work with anyone else!!l

County Education Association and an English and journalism teacher at Hidden Valley High School, has been named the 2026 Virginia Teacher of the Year. A 20-year classroom veteran, including 14 at HVHS, he’s known and appreciated by his students for his ‘ASK’ philosophy: Approachable, Standards, and Kindness, an approach that has helped him relate to and mentor countless students (and not a few colleagues, too) during his career. Neale brings a unique perspective to his students, as he came to the classroom after a litigation-focused law career.

“Matt’s dedication to his students and passion for education shine through in all that he does,” according to RCEA President Alisa Downey and VP Shelley Winterer. “We’re proud to celebrate this honor with him, our colleague and fellow VEA member!” He excels outside the classroom as well, serving as a passionate advocate for the Roanoke community. He leads the school’s opioid awareness initiative in partnership with the Roanoke County Prevention Council, working to educate students and families.

As Teacher of the Year, Neale will serve as an ambassador for excellent teaching and is Virginia’s 2026 nominee in the 2026 National Teacher of the Year competition.l

Look around: there are likely some new teachers in your building. As a more experienced educator, here are some ways you may be helpful to them, from the American Psychological Association:

Listen to his or her experiences at school.

• Respond with empathy or sympathy to troubling experiences.

• Respond with enthusiasm to good news and small victories.

Initiate a conversation.

Rather than waiting for the new teacher to initiate a conversation, ask about his or her experiences. If the response is, “I don’t want to talk about it right now,” check, gently, to be sure that she just wants to forget about work-related concerns for a while. Convey that you want to hear about her concerns when she’s ready.

Resist the temptation to offer solutions right away. In many cases, the new teacher will simply want to talk about problems and know that you understand and are concerned. Avoid saying something like, “I wonder if you could…” as soon as a problem comes out. You may be helpful in creating solutions to the problems, but this may be more productive later – after the new teacher has had a chance to talk and simply experience your support. We are all tempted to give advice or try to “fix” the problem even when we are not asked to do so.

Ask about victories and positive experiences. During the first year or two, stresses and difficulties may overshadow the large and small victories that occur every day in the

classroom. Asking about these victories can help reinforce the positive aspects of the new teacher’s day.

Focus on something other than teaching for a while. Structure some time for you and your friend to enjoy each other’s company and do things that you enjoy. Make it a rule that school will not be discussed. Everyone needs a breather from his or her job every now and again.

Ask what you can do to be helpful. We all have preferences for how others can be helpful and supportive. Ask what would be helpful.

Check occasionally to see if your support and encouragement could take other forms.

Ask how your support is working:

“I would like to help. Please tell me what would work for you.”

“Are there things I could do that would be more helpful?”

“Is there anything I’m doing that’s a problem?”

“If you would like us to talk about school, just let me know when it’s the best time for you.”

Give some space.

After being in a classroom with children or teenagers all day, new teachers may need some quiet or alone time to rest and relax. Be respectful of the fact that they may not want to discuss their day or even small talk right at the moment you ask, but may want to come back to it later.l

Some tips for having an effective relationship with your mentor teacher:

•

• Schedule a regular meeting time free of distractions.

• Have your mentor read your lesson plans and offer feedback.

• Observe your mentor and have him or her observe you.

• Work with your mentor to develop your classroom management plan.

• Keep a journal of dates and topics discussed with your mentor.

• Be open to what your mentor has to say.

When a teacher hears a student stutter, the immediate reaction is a mixture of concern and questions. Here are eight tips from The Stuttering Foundation that can help curb a student’s frustrations and help keep you at ease:

1. Do not tell the student to “slow down” or “just relax.”

2. Do not complete words for the child or talk for him or her.

3. Help all members of the class to take turns talking and listening. All children, especially those who stutter, find it much easier to talk when there are few interruptions and they have the listeners’ attention.

4. Expect the same quality and quantity of work from the student who stutters as from the one who doesn’t.

5. Speak with the student in an unhurried way, pausing frequently.

6. Convey that you are listening to the content of the message, not how it is said.

7. Have a one-on-one conversation with the student who stutters about needed accommodations in the classroom. Respect the student’s needs but do not be enabling.

8. Don’t make stuttering something to be ashamed of. Talk about stuttering just like any other matter.

For more information on how you can help a child who stutters, visit The Stuttering Foundation’s website at www.stutteringhelp.org.l

Who knew? The ageold comic book turns out to be an effective literacy-building tool. Through the Comic Book Project, an artsbased initiative hosted by the nonprofit Center for Education Pathways, students can follow an alternative path to strengthening literacy skills by writing, designing and publishing original comic books. The Comic Book Project puts students into the role of creator, writing and drawing about their personal interests and experiences, thereby engaging them in the learning process and helping to boost motivation.

For more information, visit www. comicbookproject.org l

“Supporting teacher mental health is not at odds with academic excellence; it is foundational to it. A regulated, supported educator is far more equipped to deliver high-quality instruction, build strong relationships, and respond to student needs with consistency and care. When educators are empowered to set boundaries, access mental health resources, and work in psychologically safe environments, they are more likely to remain in the profession and more capable of meeting the demands of teaching.”l

— Megan Booth, human resources professional and former high school principal

When students learn about economics, they learn practical skills that will help them for the rest of their lives. The Virginia Council on Economic Education (VCEE) is a nonprofit organization based at Virginia Commonwealth University that seeks to equip young people with the economic and financial literacy skills they will need to both survive and flourish.

VCEE serves teachers by providing curriculum and background materials, all of which are linked to Virginia’s Standards of Learning. It also offers workshops and activities designed for all grade levels, including the Stock Market Game and the Virginia Economics and Personal Finance Challenge.

In addition, VCEE also recognizes outstanding economic educators and lesson plans with an annual awards program. The awards are determined based on the use of creativity and originality in the teaching of economic and financial literacy concepts.

For information on VCEE resources and awards, visit www.vcee.org.l

In these economic times, getting a grant to fund a project is a better deal than ever. Whether the grant you’re seeking is through their organization or not, the NEA Foundation offers these tips for writing a more effective application:

• Be creative. Experiment with ideas that you and your colleagues believe will improve student achievement or your instruction.

• Identify clear, specific learning objectives and activities.

• Ask someone not involved in the project to read the application and clarify any confusing, conflicting or vague language.

• Avoid acronyms and jargon.

• Relate budget line items to learning objectives.

• Describe how the proposed work will be a true team effort.

• Develop a strong evaluation plan and connect it to the learning goals outlined in the application.

• Read and carefully follow grant application guidelines.l

Do you know when your provisional or professional teaching license will expire? It is not the responsibility of the Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) to notify you when it is up for renewal—it’s your responsibility to monitor that. However, the VDOE does provide online services to help you know your status. To find out when your license expires, or to access other information on renewals, fees, replacements and applications, visit the Teacher Licensure section of the VDOE website at www.doe.virginia.gov/teaching-learning-assessment/teaching-in-virginia/licensure l

Writing is often the strongest driver of insight because it’s a slower process, and that means writing affords more time for reflection. You do have to take time to reflect to get the added benefits of writing—quickly jotting something on a napkin isn’t likely to lead to enlightenment. Thoughtful, reflective writing has been repeatedly shown to be a beneficial exercise for gaining clarity. Writing is also well-suited to becoming a regular practice, such as journaling for 10 or 15 minutes a day… for generating maximum clarity about a confusing or troubling situation, writing seems to give us an edge over speaking aloud or talking in our heads.l

— Maryellen MacDonald, the Donald P. Hayes Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Language Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

“What did you do now? The Secretary of Education called and said something about getting you in a Full Nelson.”

“Haveyou heard of The Mayfly Project?” asked my fellow Lord Botetourt High School teacher Greg Hupp, and I had to confess that had not. He explained the program, and I believe it’s one that our public school teachers might want to be part of and even volunteer for.

The Mayfly Project is a national nonprofit that helps foster kids develop better mental health and cultivate respect and knowledge about the environment through spending time outdoors and fly fishing. Greg, a history teacher, noted that the program pairs mentors and mentees and the pair take five outdoor outings over two months. Young people, who have often experienced trauma, can develop confidence, learn a rewarding hobby, have a good time outside, and maybe even forge a lifelong connection with the environment.

“Our foster son absolutely benefitted from The Mayfly Project,” Greg’s wife, Tasha, told me. “He learned how to set up a flyrod, cast accurately, catch fish, and develop confidence in himself, plus have fun outside. The adult mentors were outstanding, and some of them were veterans, which is another positive about the program.

“I also liked the emphasis on conservation issues, such as the importance of clean air and water and how entomology fits into an overall understanding of the environment,” Tasha added. “Our foster son turned 10 during his time in the program, and there was even a birthday cake for him.”

Both Greg and Tasha noted that a number of these young people are very much at-risk, and some have even been in residential treatment facilities. As a result, they may be enduring difficulty integrating themselves into society and being successful in a school setting. Yet, the couple has

observed that The Mayfly Project has shown the ability to calm and inspire even the most troubled individuals.

“I think teachers would be especially good volunteers for this type of program,” Tasha said. “They know kids are often struggling with issues that go far beyond the classroom.”

Scott Barrier, lead mentor for The Mayfly Project in Roanoke, has also been involved with Project Healing Waters Fly Fishing, which serves veterans with both emotional and physical disabilities. So, he is very aware of the tonic that the outdoors in general, and fly fishing specifically, can provide.

Helen Barrier, co-lead mentor for the Roanoke project, has a background in special education and inclusive practices, having spent 20 years at Virginia Tech’s T/TAC (Training and Technical Assistance Center), where she served students with disabilities. Helen said that Roanoke and Pearisburg host the only Virginia Mayfly projects in the Old Dominion, but many more are needed…which is where VEA members come in.

“First, we need Virginia’s teachers to be aware that this program exists, as it only began in 2015 in Arkansas and many people understandably have not heard of us,” she said. “Second, we need teachers, guidance counselors, and other school staff to recommend foster kids 8 to 18 that would benefit from the mentorship our program offers. Mentors are welcome, even if they don’t fly fish.

“Many foster kids have spent their entire lives dealing with adults who have let them down and disappointed them. Our mentors show these kids how to develop patience, self-confidence, environmental awareness, brain rest, and, well, the word is grit. When these kids finish the program, they receive all the fishing gear they need to fish the rest of their lives.”

Mayfly Project success stories abound. Scott relates that one boy had been in foster care since he was five months old, was adopted when 15, and was one of Roanoke’s first mentees.

“His adoptive parents told us that the boy so much looked forward to coming to the five sessions and constantly talked about much he loved being outside and fly fishing,” Scott said. “We were thrilled when he came back the next year as a junior mentor.”

“He said he wanted to give back to others what the program had given to him. It brought tears to our eyes to see him in a leadership role and working so passionately with kids.”

Foster parents also have expressed their gratitude. “One foster mom came over to me and started crying,” Helen recalled. “She said she couldn’t believe the focused affirmations we gave these kids. This is just what they need, she said.”

For more information: https://themayflyproject.com/ or https://themayflyproject.com/roanoke-virginia-project/ l

Bruce Ingram (bruceingramoutdoors@gmail.com), a member of the Botetourt Education Association and a veteran educator, teaches English and Creative Writing at Lord Botetourt High School. He’s also the author of more than 2,700 magazine/web articles and 11 books.