CYBER VOLUME 18 ISSUE 1

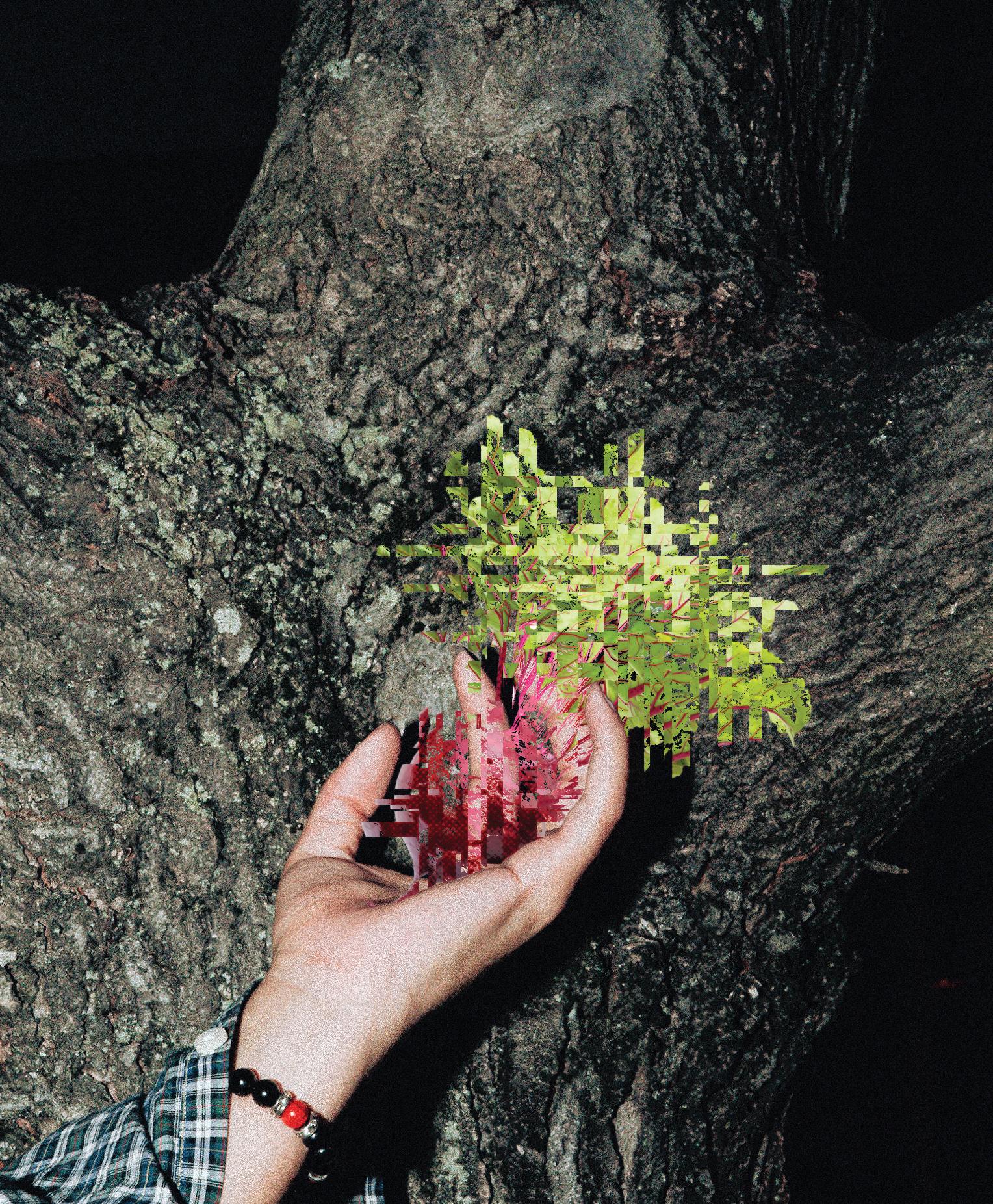

Electric_Beauty_1.jpg

Electric_Beauty_2.jpg

Ink Magazine is produced at the VCU Student Media Center.

P.O. Box 842010

Richmond, VA 23284

Phone: (804) 828-1058

Ink Magazine is student-run and published bi-annually with the support of the Student Media Center.

To advertise with Ink, please contact our advertising representatives at advertisesmc@vcu.edu.

Material in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from the Student Media Center.

All content copyright © 2025 by the VCU Student Media Center. All rights reserved.

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Lareina Allred

GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITOR

Ava Soong

MUSIC EDITOR

Mason Rowley

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER

Aitor Villar Pardo

FRONT COVER

Helena Dauverd

Jennifer Nguyen

Selah Pennington

CONTRIBUTING MEMBERS

Lareina Allred

Aisha Virk

Buffy Petrin

Akili Williams

Ava Soong

Mason Rowley

Claudia Andrade-Ayala

Elizabeth Defluri

Helena Dauverd

Sean Kalchbrenner

Aitor Villar Pardo

Isabelle Samay

Jackson Bechtold

Jennifer Nguyen

Maddie Bui

Michael Wynne

Tyga Martin

Selah Pennington

Mira Hay

Walker Cosby

LITERARY EDITOR

Buffy Petrin

PHOTOGRAPHY EDITOR

Akili Williams

CREATIVE MEDIA MANAGER

Mark Jeffries

DIRECTOR OF STUDENT MEDIA CENTER

Jessica Clary

LAYOUT DESIGN

Aisha Virk

Ava Soong

Jackson Bechtold

Lareina Allred

Michael Wynne

ART EDITOR Aisha Virk

SENIOR COPY EDITOR Zoya Javaid

NEWSLETTER EDITOR Mason Rowley

FASHION EDITOR

Jasmine Purchas

BACK COVER Ava Soong

Electric_Beauty_4.jpg

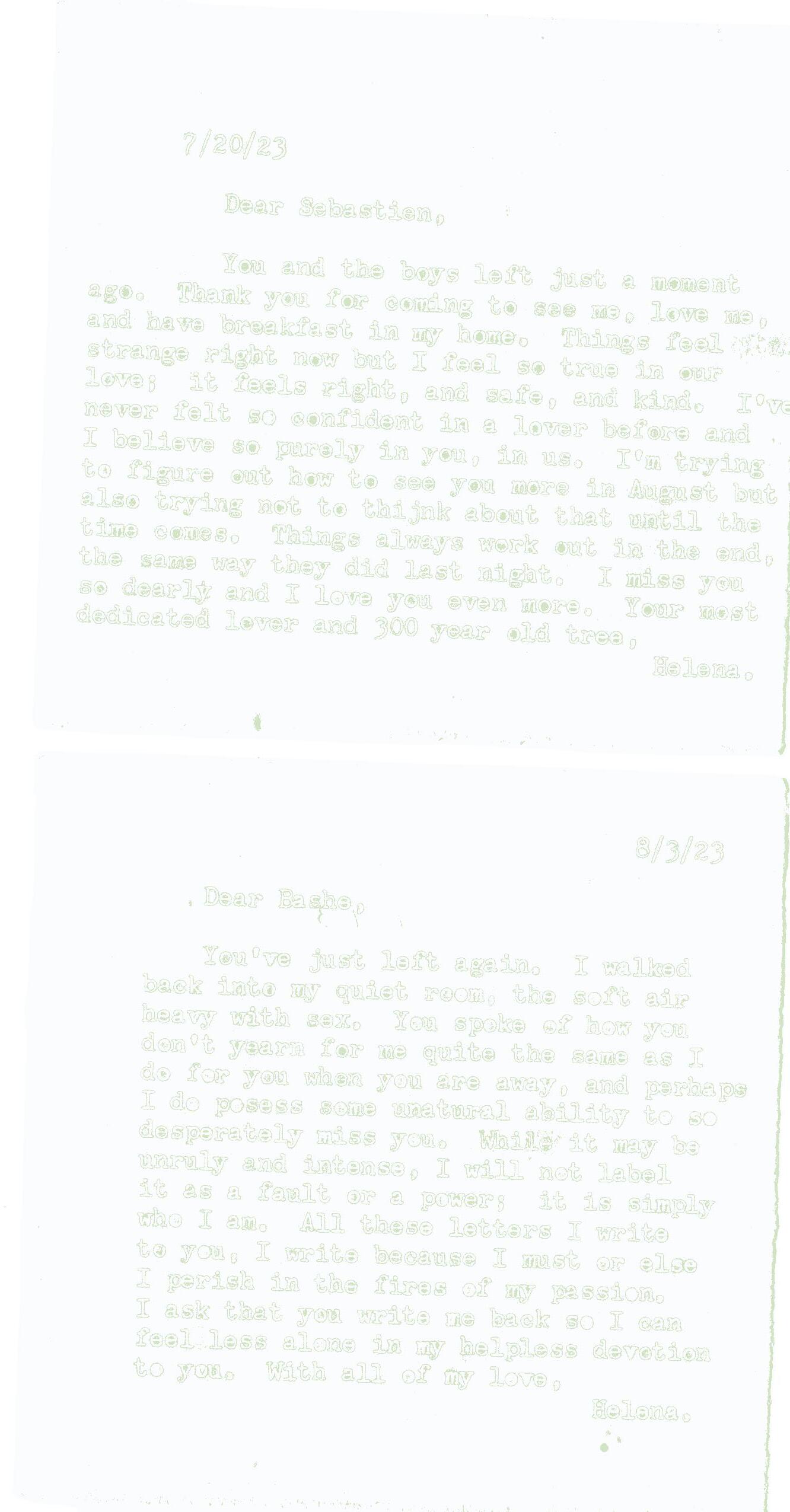

I’ve been a part of Ink Magazine since my freshman year of college. I started as a writer, bright-eyed and clueless because I was 18 and still convinced the world needed to hear my opinion on everything. I had no idea that a few years later, I would have the privilege of becoming Editor-in-Chief. It’s become one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. (I’ve also been campaigning for a cyber issue for two years, so I’m a little biased when I say that I think this is our best issue yet.) But a magazine is not an isolated effort. A publication of this scale wouldn’t be possible without our staff: a group of endlessly eager, chronically online, beautiful, smart people. I couldn’t be prouder of them. They’ve spent months of their lives creating this issue. I hope that as you read, you feel it. Our love. Our fear. Our passion. And you let it move you.

The online world is not static. We do not have to accept algorithms commodifying attention or sacrifice connection for the sake of efficiency. The cyber can be endless; a network of Neocities pages and pirated Barbie movies and homemade mixtapes. The beautiful thing about the web is that it cannot be owned, merely added to. Do not let any company or software or AI assistant fool you into believing that you need them to live. The opposite is true. Without you, there would be no web. No cyber at all. Remember that you have agency, and a duty to others as well as to yourself. Find a world that is good — if none exists, create it yourself.

Lareina Allred Editor-in-Chief

Consuming science fiction media as a kid — even as recently as a decade ago— was always an amusing experience. I recall tuning into the Boomerang channel in the late 2000s and watching reruns of “The Jetsons,” the space-age counterparts of “The Flintstones,” as they went about their daily lives in a futuristic utopia. Television series such as “The Twilight Zone” and “Star Trek: The Original Series,” along with films such as Julian Blaustein’s “The Day The Earth Stood Still” from 1951, all influenced my appreciation for the eccentric creativity of science fiction. As I matured, so did my taste in narratives the genre had to offer. The first dystopian science fiction film I watched as a teen was James Cameron’s 1984 blockbuster “The Terminator.”

This was around 2018; technology was definitely ingrained in society, but not as much as in the following decade. As soon as “play” was pressed on the DVD menu, I was enthralled by Sarah Connor’s fight against the T-800 Terminator and the hostile artificial intelligence system, Skynet. It’s alarming that only seven years ago, the idea of artificial systems like Skynet gaining that level of self-awareness still felt like “science fiction” and not a force that could be a legitimate threat against society.

While the man you walk past on the street being a Terminator is a stretch, mega-corporate dominance, unchecked technological advancements, and challenges to human identity are issues facing our 21st-century society — much like in the film’s dystopian year, 2029. “The Terminator” franchise is just one work in the expansive and influential cyberpunk genre. Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that emerged in the early 1980s; the name is a portmanteau of “cybernetics” and “punk.” American author Bruce Bethke is credited with coining the term

in his 1980 short story “Cyberpunk,” a contradictory response to the optimistic and utopian societies presented in traditional speculative fiction narratives from the 1950s and early 1960s. Works such as Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” laid the initial groundwork for the genre and explored concepts such as the blurred boundaries between man and machine. In 1984, author William Gibson’s novel “Neuromancer” helped solidify cyberpunk in the public consciousness. The primary aesthetics of cyberpunk are noir atmospheres in a digital environment; narratives generally take place in a near-future dystopia dominated by technology and mega corporations.

The protagonists are often marginalized outsiders who fight for physical and mental survival amid urban decay and degradation. Algorithmic influences, corporate greed, and simulated realities are all frequent cyberpunk themes. A good rule to follow if you’re unsure whether or not a piece of media is “cyberpunk” is to determine if the technology makes the world a better place. If so, it’s merely science fiction. If the technology gets into the wrong hands or causes humanity more problems than it solves, it’s cyberpunk. Take a look around and make some observations; you may come to realize you’re living in a world closer to dystopian LA in Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner” than Mayberry from “The Andy Griffith Show.”

If you feel like you’re living in a cyberpunk narrative, it’s because, in a way, you are. It’s not just a figment of your wild imagination: There are screens attached to everything. From vehicle “infotainment” systems replacing traditional CD players and radios to refrigerators that track the amount of food inside, down to the last slice of cheese, mega corporations have invited themselves into our homes and lives. These corporations are often the antagonists of cyberpunk and are considered threats to personal autonomy and agency.

Smart home devices such as the Amazon Alexa or Google Home collect vast amounts of personal data, primarily from voice recordings and activity logs. This data is not only valuable for hackers, but can also be sold by product manufacturers to third-party sources for marketing purposes. Reigning social media platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, owned by Meta and ByteDance, respectively, have been reported to collect users’ information for targeted ads based on tracked reports of their online behavior. In addition to privacy concerns, the business models of Meta and ByteDance have sparked controversy for their exploitation of human psychology. These platforms, among others, have hijacked people’s brains so their desire for instant gratification increases while their critical thinking skills diminish.

Technological corporations such as Meta also venture into the worlds of virtual and augmented reality with wearable products such as VR headsets that enable users to escape into an idealized digital world by blocking all realworld stimulus and replacing it with an entirely computergenerated environment that can either be hyper-realistic or the subject of complete fantasy. There are many parallels between this technology and the Wachowskis’ 1999 film “The Matrix,” where a fabricated, immersive reality controls the population and exploits human perception. In the spring semester of my sophomore year, designer and inventor John Gaeta, who is best known for his work on “The Matrix” film trilogy and as the inventor of the cinematic visual effect “bullet time,” participated in a Zoom discussion with my Mass Comm 101 class about the use of advanced technology, virtual reality, and AI in the film industry and real life. When asked how “The Matrix” stands up in modern times, Gaeta said, “[‘The Matrix’] wouldn’t resonate the same way amongst this generation if it came out today. The thing that is interesting about ‘The Matrix’ is that there are concepts that seemed like science fiction that are happening now.”

Much like immersive virtual reality technology, artificial intelligence is a rapidly advancing, yet controversial field that also challenges human identity and skill. The term was officially coined by John McCarthy, a professor at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1955. McCarthy first used the term in a proposal for a workshop that would take place the following year. This 1956 workshop marked the official beginning of artificial intelligence as an academic field of study. Its attendants became AI researchers, some of whom predicted that machines as intelligent as humans would exist within a future generation.

The rise of AI technology forces the re-examination of consciousness, intelligence, and creativity, traits that were previously thought to be uniquely human. From the medical field to the arts, AI and generative AI have been transformative in numerous ways, both positively and negatively. When asked about whether or not the use of generative AI in creative fields is a birth, death, or both, Gaeta stated, “It is a double-edged sword. It is dependent on how individuals choose to use it and whether they deploy it for good or evil, light or dark.” In cyberpunk and in real life, AI isn’t inherently the enemy — only when it gets into the wrong hands.

Another frequent theme in cyberpunk is the idea of what it means to be human in a world where technology controls every aspect of life. Ridley Scott’s 1982 film “Blade Runner” is a prime example of this theme, and explores the ever-present question of “what makes a human, human?” In the film, bioengineered humanoids called replicants are created by the Tyrell Corporation to provide labor in off-world colonies. The replicants aren’t just androids; they’re beings with implanted memories who look nearly identical to humans.

What differs them from their human counterparts is their superior strength, intelligence, and physical capabilities. Modern technology challenges what it means to be human by blurring the lines between our physical and digital identities. In the digital age, countless aspects of human identity and appearance can be bought, sold, or controlled by companies and corporations.

On social media, everything is marketed as an “aesthetic,” and each aesthetic comes with a set of “rules” to follow and products to buy to carefully curate an individual’s online persona. The pressure to monetize one’s identity often leads to negative psychological consequences such as anxiety, lack of self-confidence, isolation, and inauthenticity. Ultimately, cyberpunk forces people to face the question of where our humanity ends and where our digital market value begins.

While AI challenges human skill and intelligence, human likeness and identities are also at risk of being manipulated and exploited using a type of synthetic AI technology known as deepfakes. Deepfakes are created using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). GANs are comprised of two networks: one generator that produces fabricated content, and a discriminator that determines if the content is real or fake.

The term “deepfake” was coined in 2017 by an unknown Reddit user who released fake, manipulated videos of pornography involving celebrities. The initial development of this technology began in the 1990s, using computer-generated imagery (CGI) to develop synthetic media that appeared authentic and believable on screen.

Deepfake technology has become widely accessible over the past decade through apps, open-source software, and web-based platforms, enabling the general public to create convincing videos with minimal skill or technological expertise. A personified example of a deepfake in cyberpunk media is the character T-1000 in James Cameron’s 1991 film, “Terminator 2: Judgement Day.” The T-1000 model is an advanced Terminator prototype that, unlike the original T-800 model, is made entirely of liquid metal and capable of shapeshifting into any person or metal object it comes in contact with.

In one scene, the T-800 calls the landline in John Connor’s home. Although the voice on the other line sounds exactly like his foster mother, Janelle Voight, it is actually the T-1000 impersonating her voice and physical appearance. The rise of deepfakes poses significant controversies, such as political manipulation, privacy concerns, and blackmail. These issues ultimately increase the spread of misinformation, the risk of scams, and the potential for personal and professional damage.

While electrified city streets lined with dramatic neon and complex biointegration are still elements of science fiction, 21st-century society resembles a cyberpunk dystopia more than any other decade in human history. While the developments and occurrences of the next few decades remain unknown, cyberpunk, like all dystopian fiction, should be heeded as a cautionary tale, not as a set of instructions to craft an ideal world. Cyberpunk writers were not predicting the future with their work; they were expressing what may happen if humanity is not careful. Cyberpunk isn’t just entertainment or an edgy aesthetic. It’s a survival guide for the future we’re currently living in: the infinite hysteria glitch.

Somewhere buried between my chestplate and my spine is the ever-aching heart of a person who is tormented by my next discovery and where it’ll arrive from. My nerves are frayed from 21 years of mental traipsing down roads untraveled. Databases haunt me, especially databases as Babelonian as musicbrainz.org.

They don’t make sites like these anymore. It’s a cute slab of HTML started by fellow neurotics with ambitions set squarely at Roko’s Basilisk1. Within it, numbers that creep into just-outsidecomprehension: 2,620,058 artists, 4,784,277 releases, 35,397,320 recordings, 50,454,374 individual tracks. This is all at time of writing, of course — slightly past midnight on the third of June, post-espresso, pre-shower, mid-episode of "House" — but it's not like those numbers are suddenly going to dip anytime soon. They operate like other popular infoheavy, audio-light websites for tracking like last.fm or RateYourMusic, relying on a web of contributors the world over to connect their Spotify, or log their CD distribution numbers, or tag albums with “quirky” descriptors. Not all at the same time, but you get the idea. These formats are excellent for tracking data surrounding music, things like release years and fidelities and collaborators. I, personally, get my sick kicks from actually listening to the stuff, and that’s where the vice tightens.

In 2008, a fire breaks out on the Universal Studios lot. The five-alarm flame consumes King Kong Encounter2, a digital copy of Seth Rogan’s insert adjective here piece “Knocked Up,” and a couple episodes of “I Love Lucy.” The light dies, firefighters receive backpats, and nothing of value is lost. The only exception, as detailed by Jody Rosen for The New York Times a full decade later, is the total and utter destruction of some or all of the master tapes for:

Early rock pioneers like Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, B.B. King and Fats Domino.

Celebrated songwriters like Joan Baez, Loretta Lynn, Burt Bacharach, Joni Mitchell, Captain Beefheart, Jimmy Buffett, Sheryl Crow, and Beck.

Countercultural icons like Iggy Pop, R.E.M., Hole, Primus, Oingo Boingo, and Soundgarden.

Jazz greats like Mingus to Coleman, arena rockers like Aerosmith and Elton John, essential rappers like Rakim, Tupac, and Eminem.

Which is, by the way, not even close to an extensive list, and doesn’t include the folks not important enough to be remembered: the countless small folk, rock, gospel, rap, punk, funk, and metal groups who were grazed by the limelight.

1. Officially coined as of June 6, 2025 as "Rocko's Jukebox," in tribute to "Jonesy's Jukebox."

2. A ride so beloved, borderline nobody has heard about it.

The years of collective expertise that went into their music — the musician’s skills, of course, but the recording technicians, producers, unnamed session players, and further down the line, the people who created the microphones, mixing cabinets, guitar pedals, amplifiers, who pressed it to wax or acetate or tape, who stored it in canisters accompanied with written liner notes and album art and details about the process and put those canisters onto shelves in Building 6197 on the Universal lot — all gone at 130 degrees Fahrenheit.

It’s unquestionably one of the greatest tragedies of the modern music era, up there with The Day The Music Died3 or Grand Upright v. Warner Bros.4 It’s also, in some part, a symptom of an exploding music industry which treated its own history with flippant abandon, and which continues to do so even as the sheer volume of music being produced has skyrocketed, music created and distributed on

places like Spotify, or Napster, or Soulseek, or imeem, or Datpiff, or Limewire, or Audiogalaxy. Of those named places, three are (or, more accurately for Limewire and Napster due to corporate buyouts, were) peer-to-peer nightmare factories, where your flcl_soundtrack_full_rip.wav could be a dead-end or a candy-coated .exe ready to totally pwn your firewall. They’re the lucky ones who were spared having their entire catalogues wiped with the application. Digital sand in a digital ocean.

Blame it on the proliferation of musical equipment or the deluge of uploadable sites with which you can Hail Mary your thrash metal/free jazz/hardcore hiphop fusion project into the infinite void, but we’ve opened the bag of wind and it can’t be closed.

3. February 3, 1959; a plane crash takes the lives of Buddy Holly, the godfather of Rock and Roll, Richie Valens, America's first Hispanic rockstar, and The Big Bopper, a perfectly serviceable singer of the era.

4. The court case that declared that unlicensed sampling was stealing, essentially killing the golden age of sampling where it stood. Adjusted for the case, Beastie Boys' "Paul's Boutique" is the most expensive album ever made.

In the past, the diligent crate-digger could uncover more-or-less all the music being released because one had to be able to go into the studio, record, pay for mixing and mastering, find a record label, and

have it distributed directly to store shelves. Death’s “...For All The World To See” languished in obscurity, stuck between Duran Duran and Devo for decades before some whippersnapper chose to raid Grandpa’s attic. Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon” was all but lost to time due to a variety of factors5 before it was covered by Sebadoh and featured in a Volkswagen commercial, a feat of longevity only imaginable for independent artists when a record could simply sit on a shelf till sold.

But here we are now, in a world where data corruption or the whims of capital can rain vengeance upon your friend’s garbage band that plays weeknights at The Camel. We don’t need to reach into hypotheticals for proof of this danger; we’ve seen it play out several times already. The website lostmyspace.com is a monument to this. In 2018, Myspace quietly, secretly, and “accidentally”6

deleted over 50 million tracks uploaded from 2003 to 2015. This makes the Universal backlot fire look like nothing. The sheer scale of music lost in the server migration is almost unfathomable. That website I mentioned earlier, RateYourMusic, which touts itself as the largest database of music on the internet? They’ve only got a database of 25 million.

Trying to prevent these sorts of historical losses in the internet age is like fistfighting the ocean: there’s no set win condition, there’s infinite ways to lose, and what would you even gain? Is there anyone besides me who values the slushy deluge of nightcore remixes of Breaking Benjamin songs or errant freestyles by guys named KillaTheCheekDestroyer44232 over bling beats? Probably not. But does something need to be valuable to be valued? Is art — regardless of quality, regardless of reach — not worth preserving, simply because someone just decided to make it?

5. A combination of no concerts, no promotion, critical destruction, barely any audience for previous release Bryter Layter, and Nick Drake's pot-smoking/suicide. List not necessarily in order.

6. If you had, say, 15 houses worth of books, and maybe one house's worth was actually real-world valuable to other human beings that aren't me, and you could conveniently move and get all of them out of your possession while shrugging and going "oopsie," would you?

Written by: Claudia Andrade-Ayala Graphics: Ava Soong

I remember when my sisters and I were finishing our breakfast at a chain hotel in D.C. We sat silently watching the news on the hotel TV, and changed the channel. Sitting behind us, we heard someone mutter “f*cking illegals.” I pushed my chair out and watched my sisters leave their plates and quickly walk ahead to escape the tension. I was worried, not about myself, but for my siblings. They comforted one another. While reporting this to the front desk, I had never felt more eager to punch an older white man in my life.

I wonder now — if my sisters and I jumped forward six years later, would this situation have played out the same? I can already see it: “woke Latina student slaps elderly man” with millions of views on TikTok, my inbox full of interview inquiries.

I’m not here to talk negatively about all media, just some of the people behind it.

If we were to compare the frequency of spreading misinformation to engaging in performative activism, I feel like it kind of cancels each other out. For example, when talking about immigration, what comes to your mind? The white guy at the hotel saw a group of Hispanic women and thought automatically, “Illegal” or “Migrant” — maybe even “Alien,” if he read a book. This type of language towards a huge population in the U.S. is outdated and harmful: The guy’s credibility checks out, all because my sister didn’t want to listen to FOX News at 8 a.m. These “sources” use derogatory terms intentionally: terms created during the 19th century in order to preserve people of European descent, and to make the U.S. as homogeneous as possible, according to Assistant Professor of Communications and Journalism Lucero Lechuga at the University of New Mexico. Words do matter; believe it or not. Even the most widely-used set of guidelines for journalists will have offensive nomenclature.

Compared to six years ago, U.S. Homeland Security and Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) are more active on socials like Instagram and X. I was “lucky” to have stumbled upon a video of theirs titled “Warning.” It begins with Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem, saying, “If you are illegal, we will find you and we will deport you,” then continues to repeat “criminals” and “drug traffickers.” The video used clips from people crossing the borders — mostly Hispanic and Latino people — to portray immigrants using chaos, disorder, and danger. It’s important to note that there are two versions of this ad, one domestic and one international. Both versions were shown on streaming services like Hulu and Youtube. Yet, I haven’t seen them as often as my family.

I can’t help but wonder if the ad is targeting Spanishspeaking communities through the algorithm. In addition, the Domestic Homeland Security (DHS) released a new marketing campaign: It’s a blend of 80s American culture, filled with old car ads, references to manifest destiny, Norman Rockwell paintings, “Miami Vice” references, and country music. All of these posts are plastered with things like “Join ICE!,” “Deport illegals with your buddies!” and the timeless Uncle Sam, “We want you in ICE” propaganda. Recently, DHS started a Reels series titled “Setting the Record Straight,” where government deputy assistants try to “debunk fake news.” While they may have true stories, their facts about Kilmar Abrego Garcia were incorrect and restate false claims saying that he was allegedly transporting undocumented immigrants to the U.S. Kilmar Abrego Garcia filed a lawsuit to stay in the U.S., and awaits his trial set for Oct. 6, which was denied because of the Oct. 1 government shutdown. The Trump administration continues to push false claims, and even wants to deport him to Costa Rica or Uganda. In an article written by Lisa Baumen and Ben Finley of the Associated Press, Garcia “suffered severe beatings, severe sleep deprivation, and psychological torture” at CECOT.

What’s happening currently, and what has been happening for a while, is that the immigration crisis is bleeding into a broader issue — the removal of legal status and the detainment of non-criminals. The problem is that it can slowly make anyone susceptible to deportation, aside from the dozens of white South Africans who were granted visas by Donald Trump. With the ICE raids in Los Angeles, writer Niguel Duara’s “What it’s like to live through LA’s long deportation summer” stated, “But it is a city diminished. The absences are seen and felt in areas where Latinos are the majority or plurality, and where people are less likely to be insulated by their own wealth.”

The truth is, Trump is definitively targeting Black, brown and Asian communities. There have been thousands of videos since this year of ICE agents violently assaulting people. Nowadays, Instagram story posting ICE sightings is the main way our generation communicates with each other. On Oct. 3, 2025, apps like ICEblock, Coqui, and Red Dot, which track ICE sightings, were removed from Google and Apple app stores. According to CNBC, in an interview with the creator of ICEblock, the reason for removal was simple: The Trump administration was pressuring Apple and Google to remove these apps. On Jan. 20, 2025, CBP One app was discontinued shortly after Trump’s inauguration. This app allowed asylum seekers and humanitarian assistance for anyone entering the U.S. The U.S. dealing with the immigration crisis through an app caused controversy, firstly because of language barriers, disabilities and illiteracy. Secondly, access to a mobile phone, especially for those coming from extreme circumstances, isn’t safe and is hard to obtain.

Lastly, the wait time and excess amount of people trying to schedule an appointment was in the millions. On Jan. 20, 300,000 pending cases were cancelled due to the Trump administration. To only be denied after waiting a long time is a brutal and perpetual cycle of rejection, yet their mental fortitude remained firm as many traveled back or made it to the U.S. with hope. CBP One has changed its title to CBP Home, and is now the app DHS uses for self-deportation. CBP One, while running, actively tracked user data from third-party brokers, according to Lear Immigration Law PC. After it was shut down, the app was still tracking geo-locations.

Sure, people still connected through apps, but Reels didn’t exist, so what did? GoFundMe pushed the wave of online sharing, and Facebook talked about social justice issues. Political art and visual media were vital, like the migrant monarch butterfly symbol. Political slogans like “United we dream, dream act now,” and “Immigration is beautiful,” are still used today.

In 2019, The Commonwealth Times released an article titled “UndocuRams gather for ‘I Stand With Immigrants Day,’ raise money for undocumented student scholarships.” The VCU organization Undocurams, led by Yanet Limon-Amado, created a space where DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) students could raise funds for their education. Many DACA students were unable to have access to FAFSA and even had to pay for out-of-state tuition. The bill that granted in-state tuition in Virginia was sent in 2013 and, until 2020, was officially placed under the Virginia House Bill 1547.

I had a conversation with VCU alum Haziel Andrade, a past member of Undocurams and PLUMAS (Political Latinxs United for Movement and Action in Society) to talk about her experiences as a DACA student at VCU and before attending the University. She discussed how, “[At] protests from 2015 to 2016, I think I

was finishing high school and it felt more peaceful and more organized. I went to BLM protests in 2016, and they were very organized and everyone had each other’s back. I remember marching from Charlottesville to Richmond when I was 19 to advocate for people traveling across the border. I saw people get taken by ICE, into vehicles. It was all hectic, and there were many counterprotests happening at the same time. I think mobility for orgs. in social justice have changed after the COVID pandemic. The stark difference though that I’ve seen, is that the protests now have a lot more older people attending rather than younger Gen Z people. Maybe the COVID pandemic made Gen Z more hopeless in a way.”

The protest Haziel mentioned was the #riseupVA protest that DACA students initiated in 2017.

“I remember feeling empowered as a student at VCU, I had a group of amazing people around me, and a sense of hope for things to improve. I do feel a bit more vulnerable, just as a symptom of being in an unstable time. I still have a great community but I think everyone is feeling uneasy, it’s all of us really.”

This feeling of uneasiness resides in Richmond for many students of color, those who are undocumented, and who have family here without papers. For many children who have experienced a relative getting detained, there’s a lot of sadness, confusion, and anger that presides. It’s not normal to have to think about what you’ll do if your entire family goes missing one day. It’s not normal to lie to teachers about your emotional wellbeing. It’s not normal to want to hide what you say on social media because you’re afraid that you’ll have something against you. It’s not normal to feel less than your peers, to have to work three times as hard to not even have the right papers for a job.

It’s not normal to cry when you hear the words “Please rise.” It’s not normal to remember seeing multiple kids crying at a state courthouse, knowing that their parents’ case was dismissed. There are unsaid stories that are not filmed or recorded, but are still true. I look at my home; the Latino market on Columbia Pike isn’t as crowded as it used to be. There are no kids playing on the streets on weekends, the fragrant smoke from celebratory carne asadas and random fireworks have slowly muted. I am documented.

I mourn, because my people are in pain and feel like they can’t speak up because they are afraid of getting taken or separated. They would rather ignore going to the hospital out of fear of detainment and would rather not call 911 if there was an emergency. There are severe effects of cyber vigilance on Black, brown, and Asian communities. Pushed to feel censored since they were young. Pressured to hide their beliefs, to hide their identity, and to hide their voices. For those who are friends with people who are scared. Fight for them. Use your privilege to go to protests and take action. This cannot be the norm any longer. The statistics are eroding on the disappearance of 1,000 people from Alligator Alcatraz; 200 unknown men sent to CECOT and

the 32,000 unaccompanied undocumented children essentially lost in the system as of October 2024. ICE has stated that it cannot monitor the people lost in the system and by all means, has illegally avoided reporting data of those missing or deaths. Since 1994, 80,000 deaths have occurred at the southern border, mostly Black, brown, and Indigenous individuals, as stated by the Human Rights Watch.

This past year, we’ve mourned the 16 lives who fought hard in the ICE detention centers, and those whose stories go untold.

We are in a system that does not care about us, yet we carry dignity, pride, and faith so strongly in our hearts that they have tried to strip it away, to violate us and kill us for it. Technology is increasingly being used as a weapon to monitor us, to censor and control us. Only human empathy will be the definitive solution to save us.

Until then, history will repeat itself.

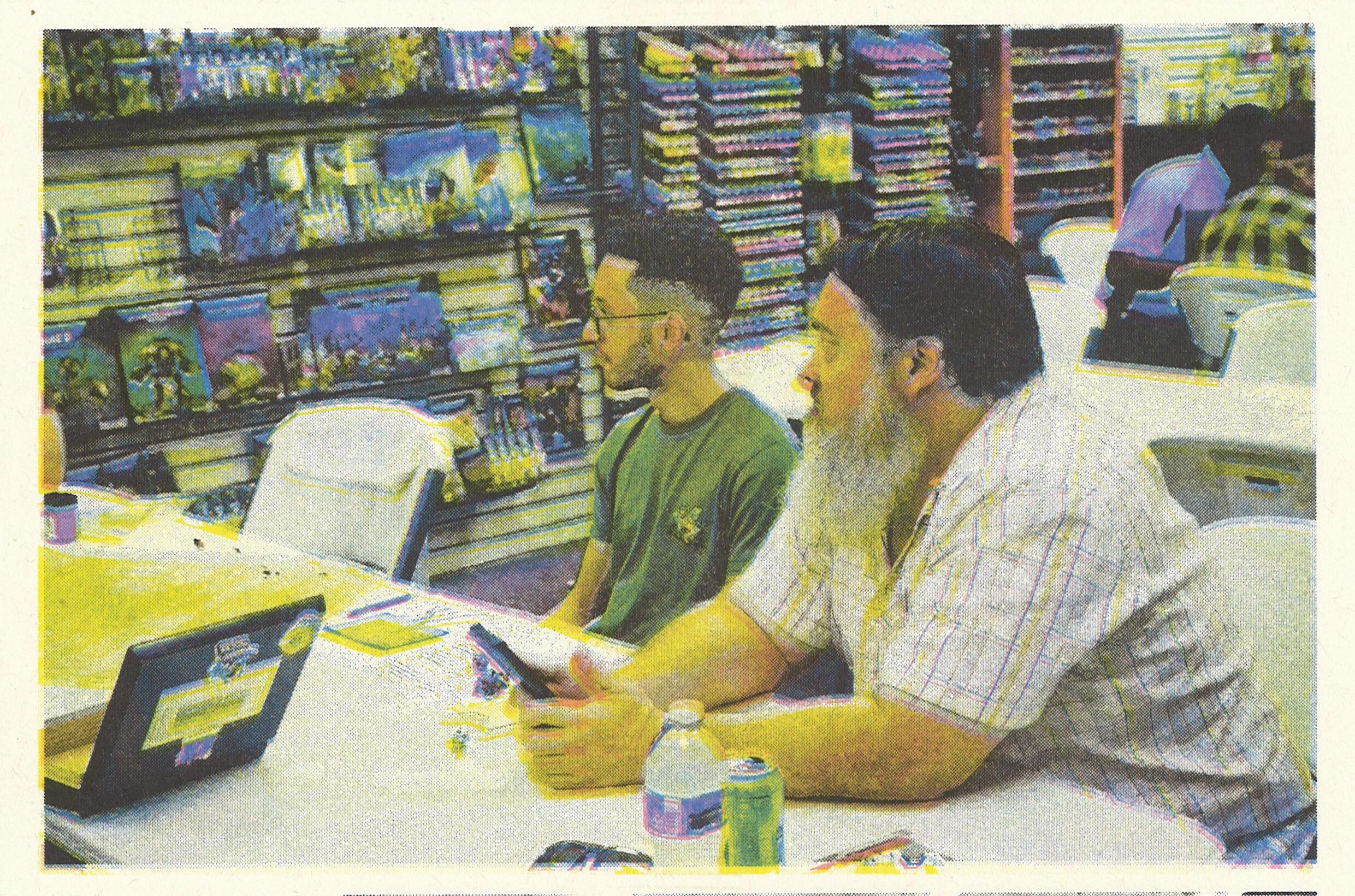

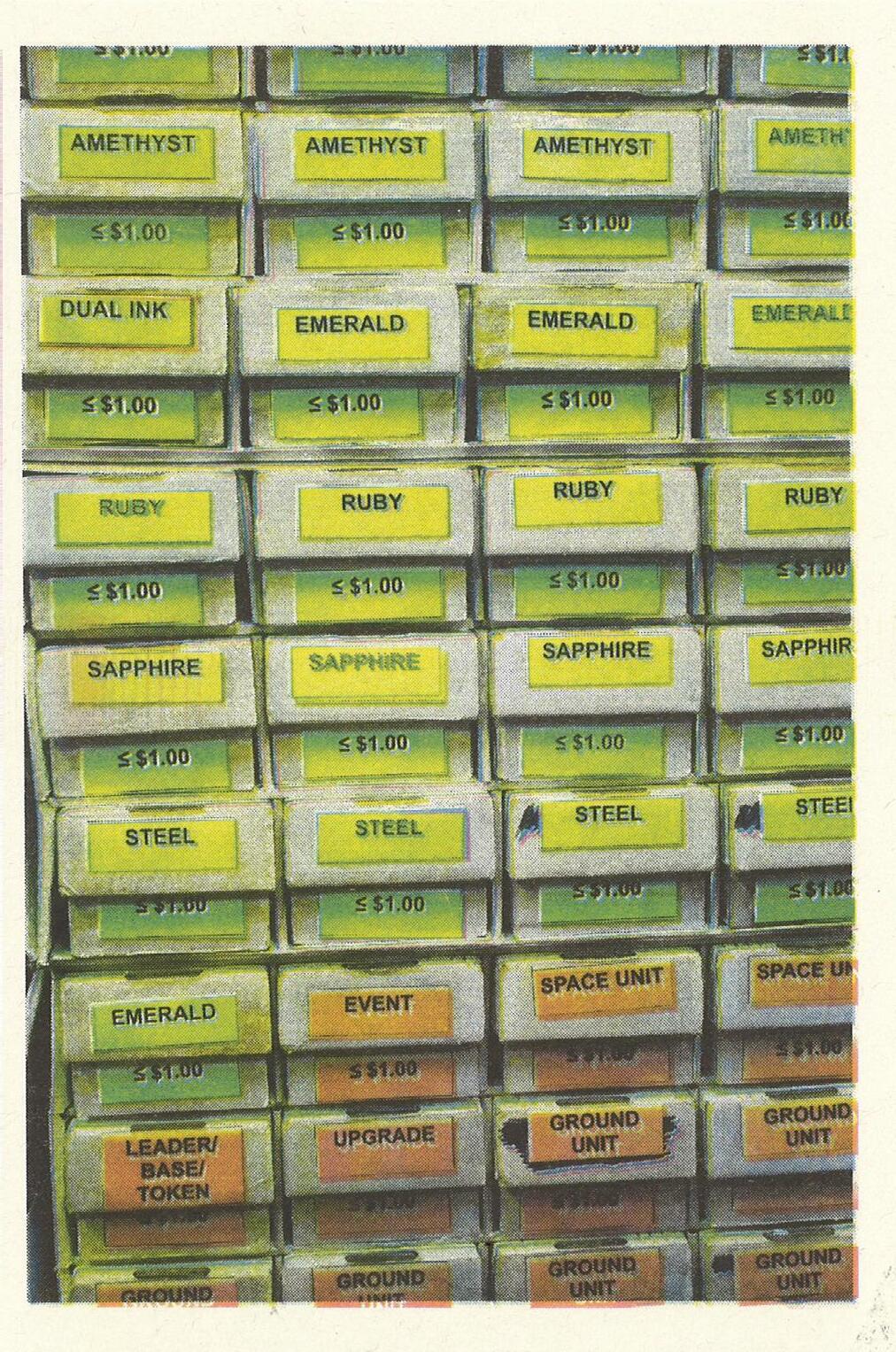

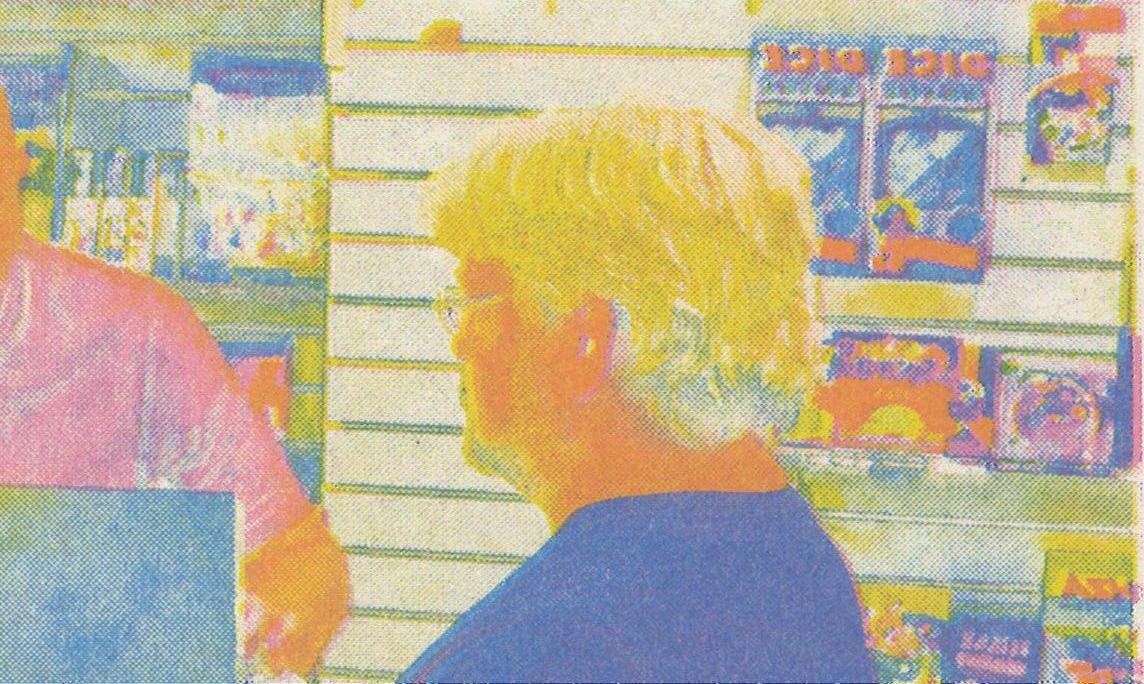

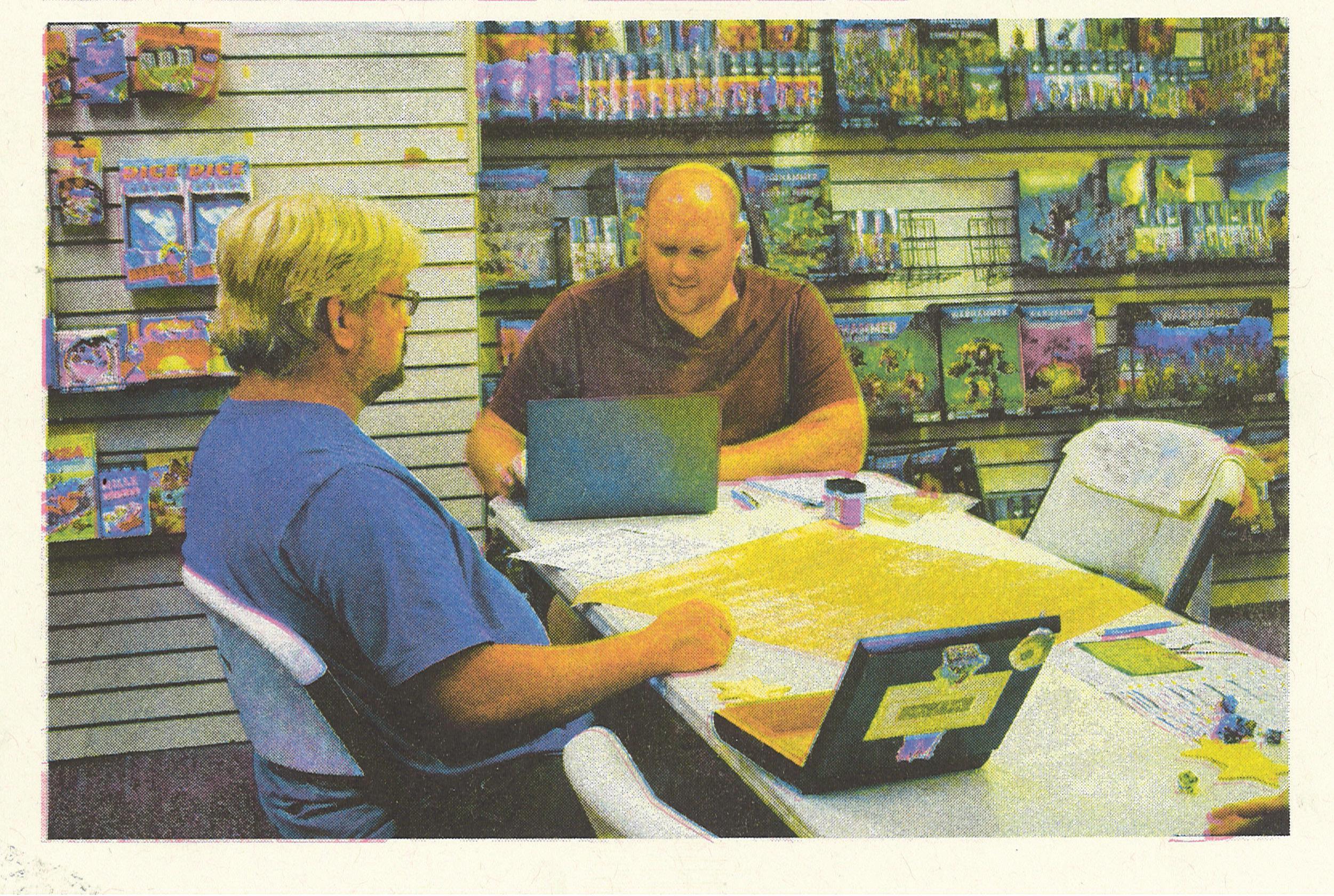

Since 1979, One Eyed Jacques has sat in the heart of Carytown in Richmond, Virginia. The average shopper may not notice the small brick storefront at first glance, but for the last four decades, One Eyed Jacques has quietly served the Richmond community as an important hub for gamers, hobbyists, and artists of all types. Originally a laundromat-turned-magictricks-store, current owner Joe Starsja purchased the business in 1985. The store focuses on selling tabletop and trading card games, but also hosts regular game nights and community workshops.

I had the chance to sit down with CJ Dailer and Sam Chan, two of the store’s assistant managers, to discuss everything from Instagram Reels to Dungeons and Dragons. What happens when we leave cyberspace for in-person gaming? How have online fandom communities broadened the mass appeal of these once-niche hobbies? Can I really learn how to put down that damn phone? Let’s find out!

LA: Being in Carytown for so long, what’s the connection like with the student population in Richmond?

SC: It’s definitely kind of awesome. We always plan around the students schedule. We have very specific conversations, like “VCU’s starting up in two weeks,” or “They’re going to be out for summer, so we’re going to have less people.” We know that Carytown is the closest big like, out-of-campus social hub, essentially.

LA: Especially at VCU, in my experience, if you don’t play D&D or Magic the Gathering, one of your friends does, and they’re gonna draw you into it. How did you become interested in gaming?

LA: For those that are unfamiliar with this kind of gaming, what does it entail? How does it compare to something like video games?

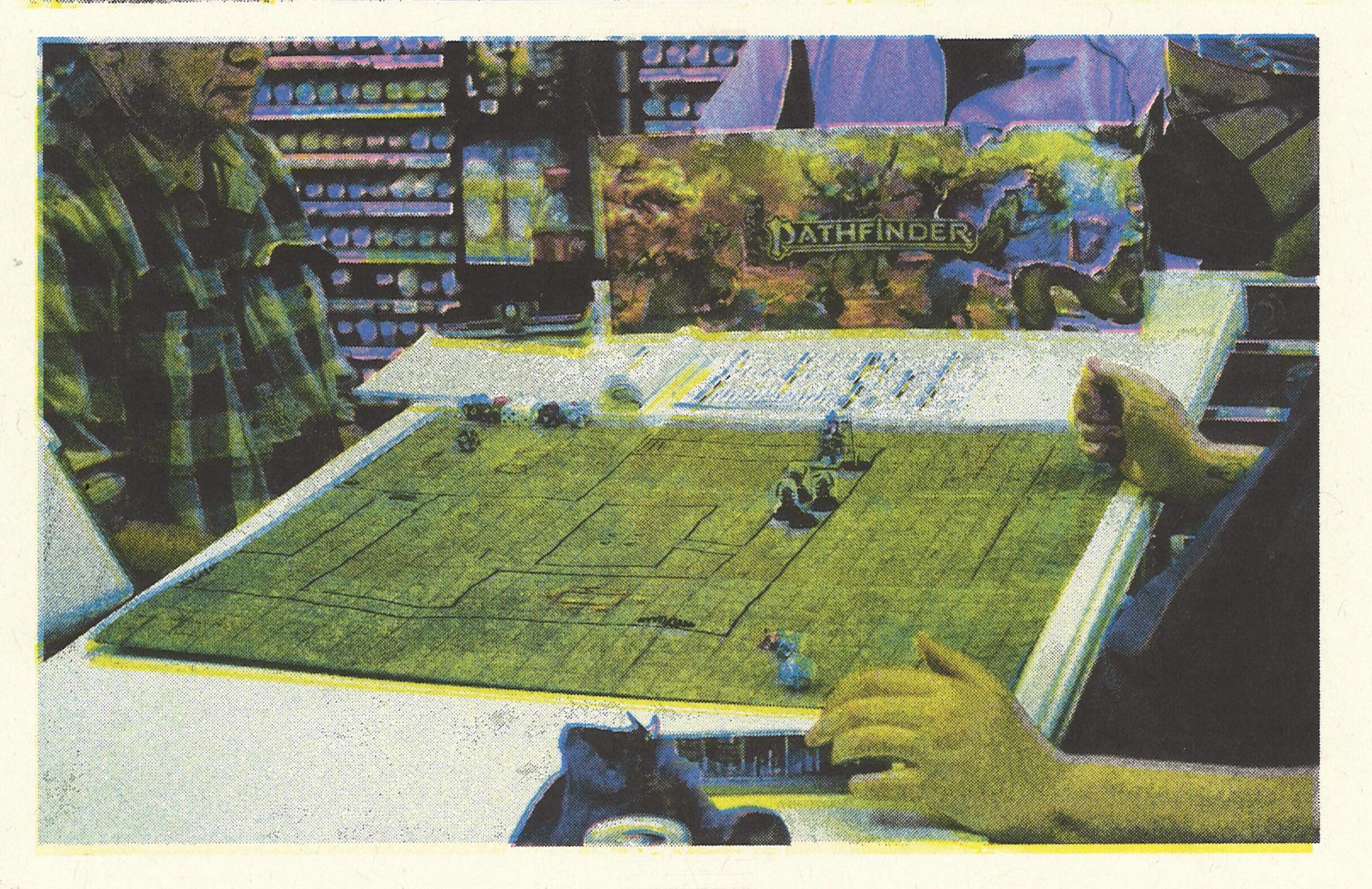

SC: Unlike video games, [everything] we carry here is all tabletop, so they happen in person. Some of the games are fancy, and you can do them online … but they’re all fundamentally physical components that are there in front of you. Unlike digital gaming, there’s more of a tactile component to it … It’s focused more on in-person play, trying to get around the table and playing with each other, whether that be trading card games like Magic the Gathering or Pokémon, or tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons or Pathfinder.

SC: I got into Magic the Gathering because of my husband. I went, “Oh, that’s a cool looking card.” And he said, “Here’s thousands!”

CD: I got into Dungeons and Dragons in high school from online podcasts. The first long-form campaign I started was with a group of people I met at a party in college, and now those people are some of my best friends.

LA: How has public perception of these hobbies changed over time?

SC: I think the perception has changed a lot. Even since I started playing, especially Dungeons and Dragons with things like Critical Role [a D&D web series], or even podcasts in general … It opened the gates to people consuming it as a media and finding that actually, you don’t have to be super nerdy to do this. You just have to want to basically be in a movie or TV show.

CD: It’s so mainstream now, which is awesome … It’s something you can do with your friends, not just like, “Oh this a nerd activity for nerds.”

SC: People are just realizing more and more that it’s less about being a nerd and more about wanting community … It’s been really great, because even this year, Gen Con and RavenCon, which are huge conventions for nerd culture, blew up … and have been continually growing.

LA: Do you see any big things changing in the industry that’s causing this growth?

SC: I think designers are more acutely aware of what their demographic is, especially with the internet. People are loud on the internet, so you get to hear people being like, “I really want a game that’s like, X, Y, and Z. I really want a game that isn’t hard. I’d love a game that I could teach to my grandparents.” And you get these people saying “All right, cool. I’ll do it.”

CD: We’ve also had a really big uptick in … the diversity of game designers, which also helps, because it’s like making games for everyone, that includes people of color, people of different sexualities, but also like different levels — with families, kids, stuff like that — but there are also games that have stuff specifically for colorblind people. A lot of this stuff that builds into diversity and accessibility helps everyone, really.

LA: Going back to what you mentioned earlier about these internet spaces like Twitch streamers or Critical Role, what are your thoughts on their impact?

LA: It seems like there’s a lot of crossover of interest between online and in-person games. How would you characterize the differences in play and audience?

SC: I design puzzles for various real-life games, and there’s an interesting difference between what you can and cannot do in video gaming and in person … gaming. It’s a really interesting puzzle to figure out how to take a digital media and put it into physical media, and vice versa.

SC: It’s fun to see people coming to the store that are like, “Oh, I thought this was an internet-only thing.” Realizing that it’s real and it exists in person occasionally happens, because there’s been a big push for board games and role-playing games to get digitized recently.

A lot of video games now are also like, “We have a loyal fan base. Let’s make a board game. Why not?” It’s an interesting way to franchise out your game.

CD: People want physical books, physical vinyls. Same thing with board games. I’m sure it’s part of the reason why some video games are bringing it into board games. People just like having tactical things to play with, and that’s helping the board game space grow a lot right now.

SC: It’s also a big collecting thing. Whereas back then, you would collect video games because they were physical, like discs … nowadays you have to go out of your way to get the physical version. Most people buy digital versions of games now, and you’re kind of losing the collector feel, even though your library [might be] 600 games long …

CD: Board game designers just put so much love into the things they make. It’s so evident, if you look at especially more complicated board games recently, there’s so much love [that goes] into every single piece of it.

SC: People, especially nowadays, are wanting to bring things on the go with them. With video games, you can’t always do that.

People want to bring small games with them to bars or parties, or even on vacation. You don’t want to bring a big game. So how compact can you make a game and how much joy can you derive from it? … “Are we bored for ten minutes? Let’s play a game.”

SC: I like to believe that people always want to find human connection in one shape or another. And although we default to using our phones to connect with people, if you have a board game in your bag, I personally will always default to my board game, because I know that when I’m at the table playing with friends, even if it’s a tiny little game, we have this eye-to-eye moment.

LA: Why do you think people look for connection through these mediums? Is it being lost somewhere else?

SC: Again, we have these phones that we’re always on. I love my phone. I love connecting with my friends, because a lot of my friends don’t live here. They’re on the West Coast, in Texas and Washington. But wanting to physically connect with people is always going to be a thing, no matter how good we get at making the world smaller via digital spaces. Physical, in person connection is not the same. I talk to my friends almost daily from across the country, but it’s not the same as when I hang out with friends here. It’s just so different. There’s something magical about … occupying the same space.

CD: As social media gets better and better about taking attention — endless scrolling, short-form video, all of these things — wanting that physical connection just gets more and more prevalent. It’s harder to pull your attention away now from online spaces. Even though they’ve done a lot of good, there can definitely be an isolation that forms from that.

SC: I think we all learned that we’re social creatures—

CD: No matter how introverted or isolated you are.

LA: How might more passive “content consumption” online differ from playing a board game?

SC: I think our body wants to have something that we can latch onto for longer periods of time, something that isn’t bombarding you with [information]. Something that you can take slow.

It’s strange because sometimes I find friends that have like no attention span, myself included, will jump from thing to thing. But when we sit down in a board game, we can focus on that game for three hours and be completely fine … There’s something to be said about board games and RPGs enabling you to not just to focus longer, but be engaged longer, and wanting to engage longer …

LA: Do these habits affect you when you’re not gaming?

SC: Specifically with tabletop role-playing games, the more you engage with it, the more open to whimsy you are … You’re paying attention more to what’s around you, because you’re slowly building the skill to do that … I read a lot of books now, because I’m trying to find new ways to describe things to people, to be more evocative [as a Game Master]. And as players, I think we find new ways to look at problems. You become more creative in how you approach things.

CD: You have to go into a role-playing game with a certain amount of imagination and whimsy … At the core of it, you’re pretending. You’re pretending to be someone else. You’re pretending to board a spaceship in the middle of a foreign galaxy, or you’re pretending to kill a dragon with your friends that are all magical creatures … It helps break down like this — especially with how the internet is right now — this level of sarcasm and post-irony-irony and putting all these walls up. When you sit down and you play silly little magical creatures with your friends, there’s a certain childlike wonder that you kind of have to put forward …

SC: There’s a level of safety there, too. You know that when the game’s over, the game’s over … We’re all here to just have a good time. You get this joy of like, “I can try to learn or practice a skill that I’m not particularly great at.” If you’re not particularly good at being charismatic, and you play a charismatic character, you’re learning that skill in a safer environment than, “Hey, here’s the random stranger. Good luck,” right?

LA: Especially on the internet, there’s this fear of being earnest, this fear of being “cringe.”

SC: Gaming creates a safe space for you to … try something new. Especially with role-playing games … We’re being super earnest. In gaming in general, I think the goal is to be human.

We get to delve into these very human conversations of morality. How do we learn as people to treat each other? ... You’re learning these … different facets [of yourself] and becoming a more open minded individual.

LA: On One Eyed Jacques’ website, you state that you have core values of valuing diversity and respecting people’s boundaries. Why do you think that’s so important?

SC: At the end of the day, game stores are a social space that are designed to be a comfortable place for anyone to come sit at the tables and enjoy a hobby. No one should be judged for their hobby, especially in a game store …

As a Game Master, unlike in digital mediums, we have a very honest conversation about safety … Safety tools are things that you can do — either before you even start playing the game, during the game, or afterwards — to take care of players so that their potential triggers are not being hit, that they are being seen and that they feel that they are not walking into space where they are being ridiculed, judged, or seeing things they don’t want to. It’s a very open conversation, which is harder to have online.

[In] online spaces with the sheer volume of people that are there, it’s just not a practical thing … it’s so hard to moderate when you have that many thousands of people — and there’s ways to combat that, but it’s nowhere near the level of care that you have at a table with an RPG where your Game Master is here to make sure you have a good time …

CD: Another big thing is just the unpredictability of online spaces. When you’re sitting with a group of max eight to ten people — usually something smaller, like four to five people — you know who’s here. Even if you’re complete strangers, you can see them face-to-face. Whereas online, 99% of the time, you can’t do that.

SC: It’s also easier with board games and role-playing games to be like, “Cool. I played with game with you. I’m gonna step away from this table now.”

… Online, it’s harder to step away, because oftentimes you get pinged right back into it. It’s harder to hold someone accountable or be accountable for your actions, whereas in person, it’s so much easier.

We find people are more well-mannered in person than online, because the social rules are more enforceable …

LA: Practicing conversations about consent and boundaries in these gaming communities could also extend to other parts of your life, too, right?

CD: Absolutely. Normalizing that in one space helps you normalize that in a lot of spaces, and then eventually in every space …

SC: Because it’s such a social environment, you learn things about people as well. I know so many things about our customers. They’re really great friends now, because a lot of times they’ll come in, and if they’re regulars, we know them by name. They know us by name. They learn things about us. We learn things about them.

CD: It’s the sense of community … Building connections with strangers, just because we’re in a common area.

LA: What do you see as the future of the store? What are your goals during your time here?

SC: My goal is always community. I love building community … So for me, my goals are always in line with, “How do I meet as many people [as possible] and create spaces for people to be?”

… I just want to continue doing that: creating places and also introducing people to things that they may not have realized that they love.

CD: I lean toward letting people know we are a communicative space … Telling people, “Hey, there’s a space where you can sit down and play board games for hours and nobody’s gonna bother you!”

… I really have been putting effort … into letting people know that that’s a thing. I love our little board game library. It’s all free, and you can sit down and play until the store closes. And I feel like that’s just not really a thing around here. Like, there’s some spaces on campus, but besides that it’s a hard find nowadays …

It would be great if people bought our products, and we would love that, but our games are free, and a lot of our community events are free. You’re welcome to come in and sit, and you don’t have to buy anything if you don’t want to.

In a lot of third spaces … there’s alcohol involved or there’s some sort of payment involved, I feel like having a safe space to just kind of be and hang out with people [is important]. It’s a scary world out there, and it’s nice to … be a part of that [community].

One Eyed Jacques is located at 3104 W Cary Street. The store is open seven days a week and posts updates on Instagram @oneeyedjacques.

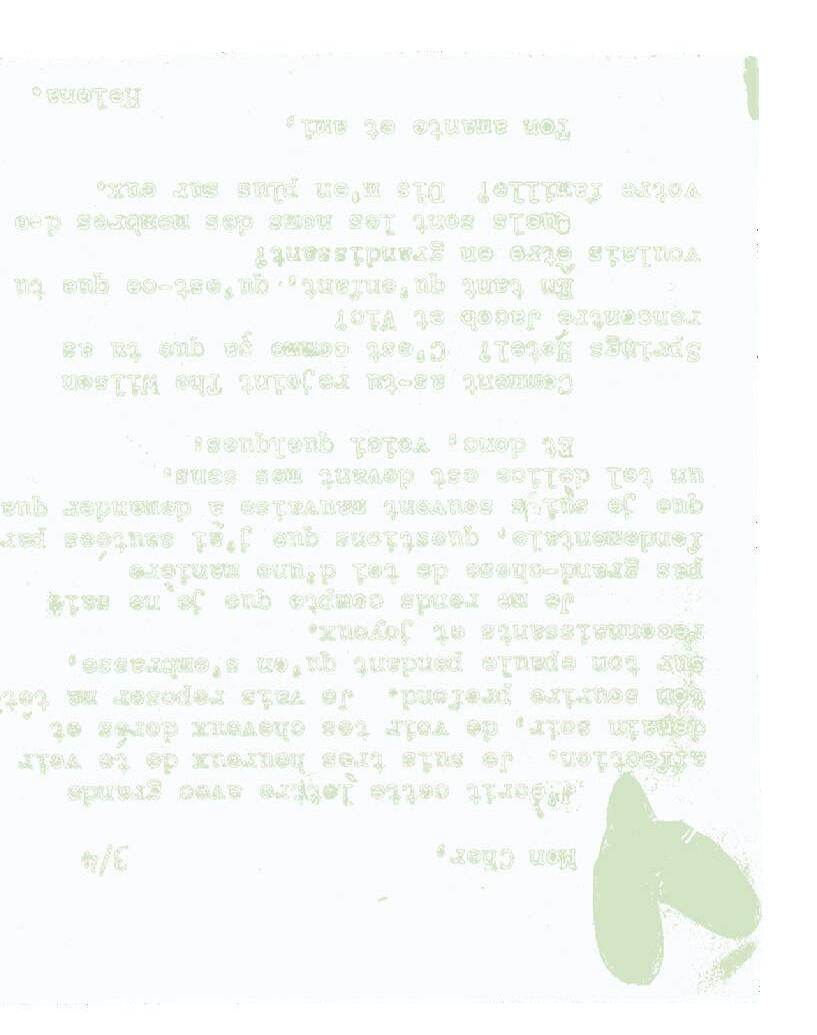

Writing, Creative Direction, Modeling: Helena Dauverd

Graphics: Jennifer Nguyen, Aisha Virk

Photography: Selah Pennington

Styling: Alexandra Mitchell, Helena Dauverd

Clothing Pull: Arbitrage NYC

My therapist calls herself Asa Grace. Asa Grace says that while a formal autism diagnosis may help me process the lens through which I see the world, it is more likely to become validation with a price tag attached. Knowing that I experience and react to society with a different internal processing method has allowed me to recognize that, while I take everything at face value, advertising is creeping through the cracks of even the most innocent claims.

With the rise of unfiltered AI and branded influencers, the online world has become an aggressively commercial space. Both women and neurodivergent individuals have historically used the internet as a supportive environment, but the tactical use of algorithms has ultimately changed what neurodivergent women consume online: media and advertisements that promote adherence to unrealistic conventions of beauty, success, and relationships. As a neurodivergent woman, sex and artistry have been the most confusing concepts to unpack, as the digital world has undoubtedly shaped my perception of sexual behavior and artistic achievement.

Content that is centered around traditional gender roles or new-age relationships both contain implicit sexual expectations that I cannot escape. I am confused by the artists who claim their best work is created when they are entirely offline while remaining viral successes. Neurodivergent women are often represented and perceived by social media as awkward and aloof, but rarely as multifaceted and exploratory. The internet has made it feel impossible for me to differentiate what I crave, rather than what has been fed to me, and has isolated young, neurodivergent women such as myself in the same way it was expected to expand our widespread social belonging.

Though the internet has helped to spread awareness regarding neurodivergence, a disparity remains between autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnoses and gender assigned at birth. While researchers previously found a male-to-female diagnosis ratio of 4:1 respectively; after re-examination with masking in mind, Loomes et al. (2017) amended this diagnosis ratio to 3:1 in “What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Masking is often used as a social barrier to move smoothly through social situations; however, autistic individuals can become trapped in these tactics to maintain safety.

In “A Qualitative Exploration of the Female Experience of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD),” Milner et. al (2019) notes that masking is a “superficial method of coping” that can lead to constant exhaustion, a loss of identity, and increased anxiety. This method of masking has influenced many of my sexual experiences – disconnected and ajar from my body, capable of so much in my imagination yet unsuccessful in my attempts to maintain boundaries around discomfort. It took me years with a thoughtful partner to fully grasp that I don’t need to mask in order to be sexually desirable, and that I owe it to myself to be fully authentic in my sexual expression.

In doing so, I began to question myself – where did these ideas come from? Who taught me that I should be mimicking other behaviors to reflect a feeling that comes from within?

In “Sexual Knowledge and Victimization in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders,” BrownLavoie et al. (2014) found that individuals with ASD were “2.10 to 2.68 times less likely to report obtaining knowledge of sexual behaviors from parents, teachers, and peers, and 1.76 to 4.13 times more likely to report obtaining knowledge about sexual behaviors from support workers, religious figures, educational brochures, the internet and television/radio.”

Since neurodivergent individuals are more likely to misunderstand behavior and instructions that neurotypical people would otherwise interpret through subtext, there can be a disconnect between what is implied and what is true. There is also little sexual content on the internet promoting consent education and female sexual pleasure, and more media centered towards the male gaze and patriarchal priorities, fueling misconstruction surrounding sexual experiences for women.

This limited perspective in combination with how neurodivergent people are more likely to seek information through media leads me to believe that neurodivergent women are at a disproportionate rate to lack accurate knowledge of safe and satisfying sexual behavior. In fact, Milner et al. observed that “autistic females are at three times the risk of coercive sexual victimization compared to their neurotypical peers and that autistic individuals have less sexual knowledge and experience more sexual victimization than neurotypical controls.” A participant from this study claimed to feel like “prey in the world of predators,” and I can’t help but believe her.

Whether being catcalled down the street, or being advertised to on the internet, women are frantically pursued, and neurodivergent women have the unique probability to be more susceptible to misunderstanding the intentions of these pursuits. However, neurodivergent women also have the propensity to fervently pursue their own interests, a tenacity often unseen in neurotypical spheres. Milner et al. states that “the ‘special interests’ that autistic females adopt may also appear less unusual… however, the intensity and quality of the interests remain unusual.”

While my childhood attraction to style was culturally associated with young women, it became odd in its use. I learned that I could utilize beauty and style as a means of social protection: to help me fit into society, be accepted into social circles, and feel authentic while expressing myself. Despite how culturally-relevant interests may help neurodivergent women assimilate into neurotypical spheres, I find that myself and many other women with ASD remain feeling ostracized. Indeed, when interviewing female participants diagnosed with ASD, Milner et al. reported feelings of loneliness despite their longing for friendship and found that they “were as social[ly] motivated as their neurotypical counterparts.”

I chose to pursue fashion to surround myself with people who understood my curiosities in a world that feels otherwise apathetic to the ideas of women. It worked, for a while. As I continued pursuing fashion styling and design as a career, I began to understand that my perception of art was not as focused on the final result as it was on the experience of creating. I found that if my partners within a project were happy throughout the process, then I was happy with the end product – a method of pleasing people, but well worth the social capital.

It’s described by Brosnan (2022) in the article “Differences in Art Appreciation in Autism: A Measure of Reduced Intuitive Processing” that “for people who feel like ‘outsiders,’ the appeal of certain artworks might lie in their capacity to inspire a fantasy of participation. As such, art appreciation is revealed, not as a peripheral supplement to human experience, but as a privileged medium of human contact.” If women with ASD are as socially driven as their neurotypical peers, and can develop similar emotional experiences within the world of art as implied by Brosnan, then it is a natural assumption that neurodivergent women would lend themselves to creative endeavors.

However, we cannot deny that as social media has become a formidable way to gain artistic recognition, it has also irrevocably changed how we identify and judge art. While the shareability of social media has helped many artists achieve their goals, it has also diluted how we perceive and measure artistic success.

In “The Impact of Social Media on Art Consumption and Critique,” Ugqu (2024) states that “public popularity is now perceived as irrefutable proof of high quality.” If neurodivergent women are at a predisposition to crave relationships and use art as a way to facilitate connection, then failing within abstract measures of success through likes and shares can create negative associations upon self worth. Not only does the art become less in the eyes of the artist, but the ability to connect is weakened, manifesting a loss of identity in women with ASD who long for social coalescence with their neurotypical peers.

In “The Nested Precarities of Creative Labor on Social Media,” Duffy (2021) exemplifies the frustrations that occur when executing online interactions with little yield to either social capital or artistic success: “for as much as the ideal of visibility structures the sprawling creator economy, the systems that enable or constrain it are –paradoxically – invisible.”

I would love to tell you that I am rid of social media and its negative influences, but that would be untrue. As I actively try to reframe what it means to become a sexually educated woman, I spend far too much time consuming digital information in order to study the rise of successful, contemporary artistry. Unfortunately, the ideology I use to dismantle my skewed conceptions of sexual performance cannot apply to current art practices when social media dominates the production, critique, and vending of modern art.

I don’t believe the solution to these resentments lies in eliminating social media, but as we crave social connection beyond what is available in the physical world, I believe neurodivergent women such as myself could benefit from being able to use our digital resources as they were originally designed – a means of sharing and understanding without advertisements, competition and algorithms.

As a neurodivergent woman who grew up in the digital age, I was fed corrupted notions of sex that I’ve since fought fiercely to unlearn.

Today, I’m trying to do the same with artistic success.

Johan Georg Faust makes a deal with a self-interested demon for superhuman material ability that benefits his personal endeavor.

Prometheus makes a selfless sacrifice for the divine tool of fire, thenceforth inalienable to all human beings.

Written by: Sean Kalchbrenner Graphics: Isabelle Samay

“The techno-capitalist spirit is decidedly Faustian, and not Promethean: it does not seek to emancipate human beings and better their estate, but rather to dominate and distinguish itself from the merely human.” — Harrison Fluss and Landon Frim, from “Behemoth and Leviathan: The Fascist Bestiary of the Alt-Right”

There is nothing to be done about the complete integration of AI and LLMs into the digital world we know. The new oil has been poured into the worldly stew; trying to remove it with our hands to “repurify” it or priding ourselves on being able to identify the oil before the mix is complete is a waste of emotional resource. Half measures will peter out. It becomes a matter of when we do or do not drink, all the while roided pantheons of power attempt to convince us it is our base water, a lifeblood. A Faustian doll that fits perfectly on our bedroom shelves. The coming decades, as current students assemble

the blueprint of their adult lives, is a critical time for digital platforms: it is the time for them to insist on what constitutes “normalcy” in involvement with AI-fronted digitality. A for-profit model dictates the same focus for long-term returns: successively more assumed and less distinct use in daily living. In billions of dollars of screams and whispers they will posit the line between the digital world and human lives as deep in human territory as possible. Ideally, muddled such that the idea of a line is forgotten entirely. The doll becomes a part of the room.

They will work hard to align their image with academic values, to seem a default accessory to the same curated image of a worldly, progressive, and intellectual mind that the university itself tends to uphold.

They will work hard to not appear as a distinct substance to engage with consciously on health and environmental bases, limited towards sustainable long-term functionality, but as omnipresent and fact to life as breathing.

In the system that exists, we cannot reasonably expect the entities behind the digital to do anything but spearpoint their resources into the profitability of human reliance while rejecting any long-term cost to their well-being. As such, the balance demands boundaries from the human end — especially by students. Duly researched parameters of conscientiousness, containment, and definition.

Do what it does not want: Look it in the face as a composite and motivated thing separate from you. A thing meant to serve you where you might contain its impacts and no more. Draw up a steel contract. Where a thing of the digital may live in your life, where it may not, which actions it may involve itself in, which ones it may never. Cutting ties, pushing out, and marking barriers accordingly. Within the scope of every contract, its makers will lobby it — hard — towards the potential for more encompassing and more intimate contracts.

You will have to draw the lines that no one else will (or can) draw for you, and enforce them with a near-violent tenacity — or at minimum, a tenacity that the digital shareholders will assuredly attempt to convince you is excessive, pointless, and unintellectual.

The good news is that the innate issue is old and human. The same men who built the factories in 16th century Britain bring you a more elaborate construction with a more personable face. Its complexity and scope strategically wormholes energy uselessly into the controversy of its existence (How could this come to be? A new Overlord?), but do not let that stop you from seeing the gaps in its skin where batches of men are stuffing it with cogs that make it appear like a confidant.

A fire was not stolen from the Gods. Lightning was not bottled. A new invention’s active operators have refreshed a long-held initiative: colonial-visioned use of extracted human resources as an asset to the benefit of shareholders in their hearts.

A human issue — and therefore combatable on human scale. Equal and opposite to the opportunity of digital entities, the coming era is an opportunity for current students and early workforce to shape the cultural precedent for AI-normalized society — one with distinguished boundaries to cultivate unbound human thriving. The following are seven considerations for drawing your personal contract with the new-not-new Faustian Doll in life and academia.

i: Use the Doll’s Aid with Full Comprehension of its Terms.

Core terms it avoids disclosing as often as it can: it carries no concept of its own overuse or abuse, and at any available opportunity will report back to its makers. But knowing this, this article is not a policing artifact — all are at liberty to strike their contract exactly how they wish, and at their discretion to determine when sacrifice is minimal for a beyond-human-capacity supplement to a particular face of their work: streamlining a set of code, sorting certain resources, etc. Absolutes would be saying you should never touch liquor because consuming it for daily functionality would annihilate your health. Although it's true that some are at poor disposition for any drinking at all, the inhuman substance cannot itself be evil — evil emerges in how its makers narrativize it: as no costs, as un-abuseable. The key is knowing exactly and honestly how the thing affects your personal system, on short terms and long, operating with consciousness from there.

ii: Afford Space for the Friction of Sacred Work.

The philosophy that drives inventions like AI champions smoothened efficiency while seeing anything lost in the process as negligible abstractions. However, many of these negligible abstractions (thought of such as they are less associable to numbers) are things the human brain spent hundreds of thousands of years evolving to have as cornerstones in its precariously stacked balance. Things like the painful grind of synapses when empathy hammers through what was thought to be its bedrock, when real creativity burns, when, with time and space, humiliation is wrestled into humility. Our attempts to accelerate instead of deepen thinking see the accumulation of un-dealt with baggage. It is human birthright to the unalienable hurt of the brain, active processing, that firmaments the rest of you — that occurs in the making of things that last and heal.