INK Magazine is produced at the VCU Student Media Center.

P.O. Box 842010

Ricmond, VA 23284

Phone: (804) 828-1058

INK Magazine is a student publication pulished bi-annually with the support of the Student Media Center.

To advertise with INK, please contact our advertising representatives at advertising@vcustudentmedia.com.

Material in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from the Student Media Center.

All content copyright © 2025 by VCU Student Media Center. All rights reserved.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

KAYANA JACOBS

LITERARY EDITOR

LAREINA ALLRED

ART EDITOR

CALEB GOSS

PHOTOGRAPHY

EDITOR

KOBI MCCRAY

SENIOR COPY

EDITOR

ANDREW KERLEY

GRAPHIC DESIGN

EDITOR

MARTY ALEXEENKO

MUSIC EDITOR

ZOYA JAVAID

FASHION EDITOR

JASMINE PURCHAS

NEWSLETTER

EDITOR

MASON ROWLEY

SOCIAL MEDIA

MANAGER

NATALIE UHL

DIRECTOR OF STUDENT MEDIA

JESSICA CLARY

CREATIVE

MEDIA MANAGER

MARK JEFFRIES

FRONT COVER

XXXXXX XXXXX

BACK COVER

AMYNA DAWSON

LAYOUT DESIGN

MARTY ALEXEENKO

LAREINA ALLRED

CALEB GOSS

LYDIA BEHLER

AMELIA MAGEE

AVA SOONG

RYAN BENSON

CONTRIBUTORS

LAREINA ALLRED

CALEB GOSS

KAYANA JACOBS

MARTY ALEXEENKO

JASMINE PURCHAS

AKILI WILLIAMS

LUCILLE ELLIOTT

AURELIO BABBIT

AVA SOONG

AMYNA DAWSON

SELAH PENNINGTON

AISHA VIRK

ASHA HUBBARD

AMELIA MAGEE

CLAUDIA ANDRADE-AYALA

BUFFY PETRIN

WALKER COSBY

RYAN BENSON

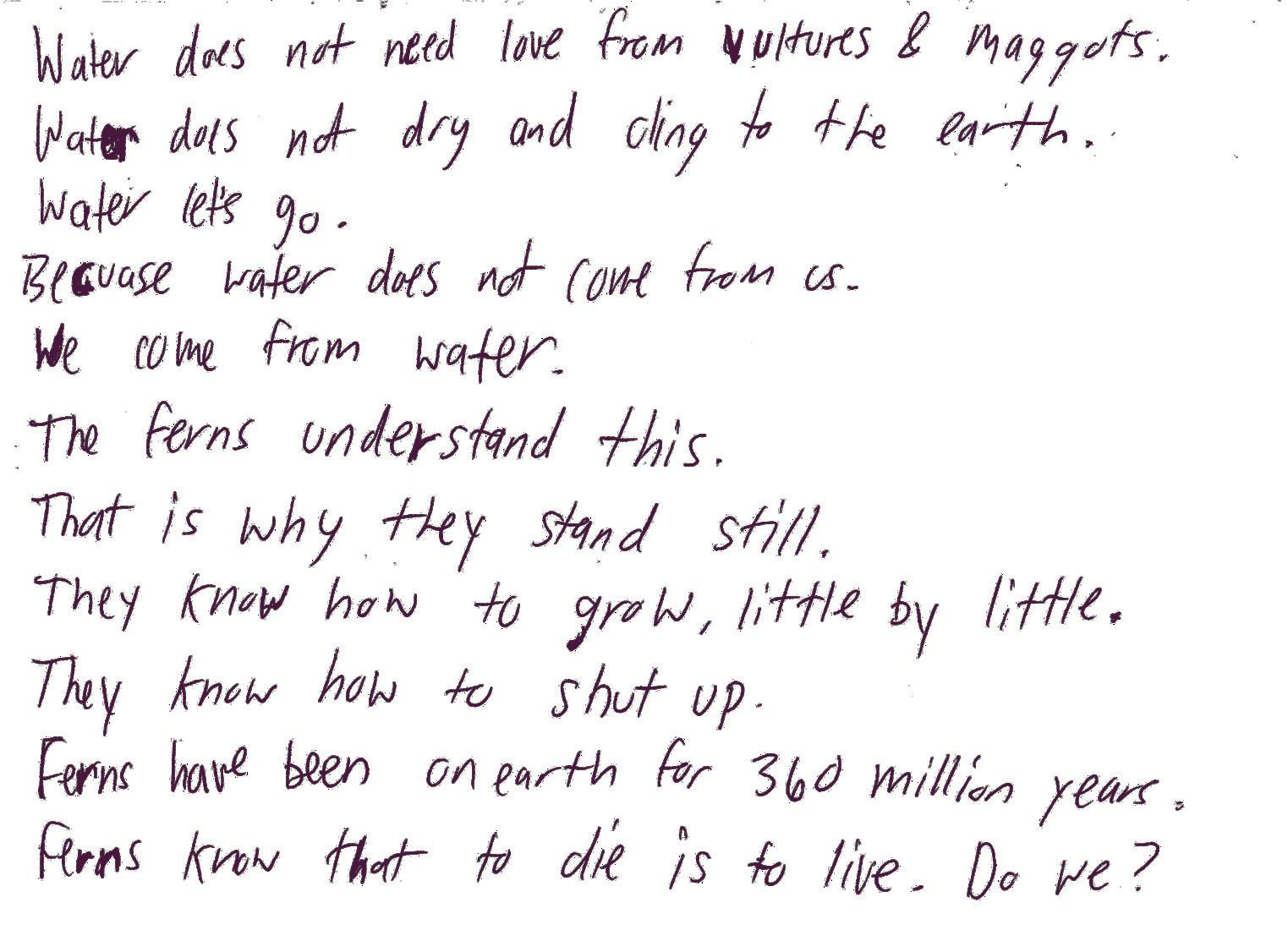

Dear Readers,

Being as natural as you can be in a world that suffocates Hating everything and wanting nothing but your sore being, bare Being as vulnerable with your lover, yet guarded with your thoughts.

What are we if not our rawest forms?

Who are you — without me? Without your layers Without money, without sex, without drugs Without fulfillment and fantasy.

What remains?

How are we to know? When life rawdogs you and simply being alive is rough When the degradation of our energies physically changes our beings, And the game of pretend has ended When life's road takes you away and makes you stay, What would you say?

I’d say everything I couldn't

Ignoring the overgrown knot in my throat And spilling the words I swallowed whole

The rawest of emotions would surface, for at the end of the road When life strips away everything but my bare bones, I will finally embody my rawest form.

Kayana Jacobs Editor-in-Chief

CHAPTER I

Ten thousand years ago, our ancestors began domesticating mammals for their milk. It’s a relatively recent development in human history, but it’s one that has shaped our culture, religions, and of course, our diet.

The genes that allow people to more easily process lactose are still most common in parts of Western Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, where raising livestock became a main source of food and commerce. These lucky populations can guzzle milk to their heart’s content without much consequence, because they’ve evolved to continue producing lactase — the enzyme that allows us to digest the lactose in milk, originally only present in infants — well into adulthood.

However, many others still experience nausea, queasiness, or more … unpleasant side effects if they consume too much dairy. Their ancestors likely did not need to rely on dairy as a prominent food source, and consequently never evolved to be okay with it. So now you get an endless parade of upset stomachs and Lactaid pills as we try to muscle our way through American grocery stores, bemoaning about our lactose intolerance and yet, if you’re anything like me, still eating copious amounts of cheese.

Products originating from cows, goats, sheep, and other domesticated mammals have fed millions of people for thousands of years. Dairy remains an important staple in many cuisines. Cheese, yogurt, butter, ice cream; these various and sundry pleasures of life all rely on the existence of milk! What would life be like without this magical source of calcium, or as those of the Middle Ages called it, our “virtuous white liquor?” What would we dip our chocolate chip cookies into?

Milk is no longer just a drink. It is an enduring symbol of America’s fracturing politics. We like to imagine picturesque dairy farms alongside beautiful young milkmaids, associating it with all things fresh and fertile. Milkmen of the 1950s delivered that precious nectar straight to your door, and then had affairs with your wife!

Our country’s cultural imagination has placed milk on a weirdly high pedestal, offering big-time tax cuts to dairy farmers and inventing a food pyramid that incentivized children to eat tons of cheese. But alternatives have been cropping up faster and more plentiful than ever.

According to food researcher Nils-Gerrit Wunsch, the sale of plant-based milks earned an estimated $2 billion in 2024. That number is projected to only increase in the coming years, as most restaurants and coffee shops now stock a variety of alternative milks for their customers. Ask

a VCU student what kind of milk they take in their coffee, and you’ll usually receive a very long, very impassioned answer about how Blanchard’s skimps on oat milk and how dairy upsets their delicate, liberalized stomach. Almonds, soybeans, oats, cashews, the options go on and on. Hip consumers usually rave about plant milk’s health benefits and ethical superiority, but I like it mostly because it doesn’t give me violent diarrhea.

Recently though, milk straight from the cow has been having a sort of cultural renaissance. Lithe TikTokers spout the benefits of drinking milk to their fans alongside daily supplements and red light therapy. Liz Seibert, an Instagram influencer and model, posted about the benefits of unpasteurized milk for “balancing her hormones” and the locations of her favorite Amish suppliers. The girlies are back to drinking cow’s milk, and some insist on having it raw.

But what even is raw milk?

Raw milk simply means unpasteurized. Pasteurization is, in short, heating up foods to destroy pathogens. According to the Louisiana Department of Health’s Bureau of Sanitation Services, “Pasteurization is a process by which milk is heated to a specific temperature for a set period of time to kill harmful bacteria that can lead to diseases like listeriosis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, diphtheria and brucellosis.” Cool! I love not contracting diseases!

Despite some influencers’ claims that raw milk is nutritionally superior, helps to treat asthma, and builds your immune system, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has conclusively found that this is not true. In “Raw Milk Misconceptions and the Danger of Raw Milk Consumption,” the FDA states that “Raw milk can contain a variety of disease-causing pathogens, as demonstrated by numerous scientific studies. These studies, along with numerous foodborne outbreaks, clearly demonstrate the risk associated with drinking raw milk.”

So why does this trend persist, and what does the average VCU student think of the raw milk movement?

An anonymous student states that “It’s very interesting … what it actually says about culture right now. I think of people like Nara Smith and the whole trad wife movement. How there’s this idea of what cleanliness is and what a cleansing is. What is that style called right now? Of the clean girl. Or this new wave of health … and how that actually is showing how we’re moving into a far-right society — even though we kind of already have, and always have been in a lot of ways.

“Looking at … these new crazes makes me think … [about] who is promoting these ideas [online]. Like, ‘Look at it! It’s good for

to poor government isn’t to descend into anarchy and defund the FDA, rolling back the clock on hundreds of years of scientific progress; it’s to make these institutions stronger, more localized, and better equipped to educate the public about what really matters. We have to build a society that trusts each other. Instagram-sponsored snake oils may soothe the wound of living, but they will never heal you. There is a better way to live on this planet.

Between the teetering extremes of hyper-processed factory foods and antivaxxer tradwives, most Americans just want to get through their day without adding more to their already increasing grocery bill. So what do we do? Roll over and let the Monsanto overlords harvest our DNA for AI-generated crops? Or try to start our own homesteads with 12 babies and a bunch of cows infected with bird flu? Neither extreme sounds appealing, but thankfully there’s a middle ground that asks very little: just be a normal human being! Eat the food with the Red 40 dye in it, or don’t. Be a vegetarian or a vegan or a pescatarian or a lesbian or whatever, or don’t. Start a community garden. Purchase from local farms and businesses with ethical practices. Fuel your body and your mind with food that you love! But please, please just put the raw milk down.

Science is a fickle thing. It is neither perfect nor eternal. Things can change, and our understanding of the world is always in flux. However, the solution to this uncertainty is not to cling to false prophets. It is to accept fear, and to sublimate it into action.

Far too often, though, it is easier to believe in online wellness fads than it is to face the truth: no one is sure of anything, and we are all just trying our best. There is no master plan by Big Dairy to turn your children into hormone-depleted soy boys.

There are no scientists in white lab coats sneaking microchips into flu vaccines. Raw milk will not make your skin brighter, your hair shinier, or your “gut biome” more balanced. On the best of days, it’s just going to taste like milk. On the worst of days, it’ll give you salmonella. Peppermint essential oils will not cure whooping cough, facial massages will not magically sharpen your jawline, and if you never stop to examine the paranoia and mistrust that governs your life, you’re going to wake up one day in a hospital bed, dying of a completely preventable disease.

Written by: Buffy Petrin

Graphics: Asha Hubbard and Amelia Magee

The sky is full of stars through the sunroof, and this park ranger is rapidly approaching the window in his stupid, stupid hat. We’re not high yet, but we could be: there are exactly four lighters thrown across my best friend’s seats and console, a bag of “donny burger” weed in the glovebox, and one purple, cat-shaped pipe that hasn’t been cleaned in months. She found it on the ground some sunny day in the park, lying helplessly in the dirt like a turned up centipede.

To them, it felt like luck, but I hated how their eyes lit up. Technicolored flashes illuminate the barren battlefield parking lot, closed after dark — the perfect spot to slouch around in a brand-new Elantra that somehow already reeks of stale cigarette smoke and burnt carts (said car would end up getting totaled a few months later, as I always feared when strapped into its backseat veering down the highway, blasting Yabujin or Nyan Cat remixes).

This always seems to happen to us: rangers on the beach, drug dogs at Greyhound stations, overlyconcerned English teachers. Yet it’s surprisingly easy to avoid lasting consequences as a bunch of weird-looking, privileged teenagers. So easy, in fact, that you never learn when to stop.

drove lifted trucks trying to become SoundCloud rappers (think Nettspend with less charm) or fail high school Chemistry. They were on the local news for wanting their names to be called at graduation, skipped class to sunbathe in the woods instead of being alienated; honked at in the parking lot by swathes of unwashed camo-clad teenagers.

This sort of intangible existence calls for a solution to circumvent reality, isolate the feelings from the circumstances into a thick, sticky slop of warm night, ashlittered balconies, and “King of The Hill” reruns. There’s a transmutative property in letting your mind float away from you: everything else seems to drift with it. The cat pipe is a gateway to escaping the wound of displaced queerness, if only for some fleeting hours. There’s something inexplicable about adolescence and the draw of escaping identity, the need to be freed from the confines of the self in order to crack it all open and see what’s really inside. The problem is, when you’re self-immolating in the echo chamber of “you,” what lies beyond gets as hazy as the smoke that trails up towards the shoreline.

It’s easy to resort to black-and-white thinking before your frontal lobe has started to develop. Drugs are bad. Friends submitting themselves to active addiction is even worse. With enough convincing, it turns into a sort of artistry or romanticizable suffering. There are two acceptable paths at the ripe age of 17: “girlfailure” or miserable Car Seat Headrest fan, both exceedingly postironic, so-lame-it-wraps-back around-toactually-being-cool forms of dependency. (It’s also very easy to view things

as innocuous when they receive an aestheticized label, looping back to becoming part of identity itself!) These are the only “okay and interesting” ways to abuse substances. No one understands the true cerebral nuances of getting fried after school daily, playing Persona, or listening to “Twin Fantasy” on loop — or so I’m told. I understand what they mean, though. It’s like being frozen in a moment of perfect time; security like you can find nowhere else in the world.

I was always put off by the inability to connect with my own body in these moments, feeling trapped in my mind rather than freed from it. Maybe that’s the point, but I’ve never met anyone who could effectively intellectualize a perspective numbed to so much of the world. Others are not so lucky. Nights turned to days, to elaborate routines of running away from truth and fear, or most certainly from emotional intimacy. Their memories are a blur now, the tailend fragments of ripping bongs from the passenger seat on trail roads, chasing waves on the grey beach, staring up through empty fingers at the wind chimes strung up on the ceiling. The only thing that remains is a burning sense of guilt; despite the world’s failings, our shoulders brace the weight.

Gravity, sadly, doesn’t discriminate.

So, at a certain point, things start to fall apart. It’s fun, until your best friend fails out of college and sends you a very long paragraph about how you can’t be friends anymore because she’s “too neurotic” and has felt like you secretly hated her for the past three to four months. Your other best friend is slightly more affected by receiving an identical paragraph hours before; considering their fraught, nebulous homoerotic tension — who has the time to think about emotional ramifications when you can get really high, watch “South Park,” and make out? We make fun of her for the notinsignificant amount of coke she buys for a mutual friend’s “birthday” later on that she does most of, blissfully ignorant to our own tight grasp on escapism simply packaged in a different form.

Clearly, the problem exists at the root, but it still makes me wonder: why do we chase the tactile unattainable? Is suffering more worthwhile if it takes on a tangible existence? Tonsil stones, not being able to remember what you did the day before, feeling complete apathy towards love and connection. Is it part of the human condition to avoid pain at all costs? Or is it for the euphoria, a weightlessness not possible through mundane existence? I decided to moralize it as a form of damage control, an opinion formed by naivete and a dash of necessity. It was cool, it was “Lana Del Rey,” it was the only thing keeping the people around me afloat.

This transmutes when I go to college. People are tethered to their habits in a much more functional way — this time, with easy access and approval. Go out, get drunk, dance until you throw up. However, I wasn’t “allowed” to drink until my first Spring semester by my boyfriend at the time who had literally dealt drugs to my entire high school. Though it was most definitely a control tactic, I got to witness everything from a birds-eye view; the trails of vomit and slumped shoulders

in sallow campus buildings, mouths connecting trails of smoke. I watched people fail out, get put on academic probation, and get kicked out of parties. There’s only so many times you can watch drunk people stumble in mosh pits and then break out into a tale of family tragedy on the (now long, annoying, and necessary) walk home before it gets really, really old. I started viewing substance use as an exacerbatory evil: watching people wallow in their own self pity quickly dispelled my romantic notions of the “tortured artist” rationalization I had held on to for so long.

It’s no lie that substances are inextricably linked with culture. “Heroin chic,” “bumpin’ that,” and Troye Sivan’s “Rush” are all tied to glamorizing drug use to achieve a level of higher being, ranging from shocking thinness to becoming a popular “it’ party-icon. Vermin Supreme lit my friend’s cigarette in the back of a bike shop! The perception of substance use in young adults is extremely highly aestheticized (particularly in queer communities), leading me to question if being outcast and put into a tumultuous social environment early-on leaves us with a sense of apathy and recklessness that follows like a sort of murky, impenetrable fog. It’s fun and interesting to do Benadryl alone in the woods — not completely irresponsible! When others have little regard for your autonomy and existence, does it just rub off? Some blow hundreds of dollars on cheap wine and American Spirits, some smash their face on mossy rocks at Belle Isle and get two brandnew front teeth, some start lugging a bag of loose tobacco with them everywhere because they fully ran out of money to buy actual cigarettes with. And yet the world keeps spinning, apathetic to the compounded woes of the unglamorous, bleary Richmond populace.

Community, and a lot of times the lack thereof, is the likely the singular most important influence. It’s how people end up doing coke at the ripe age of 14 just to watch “Regular Show.” It’s a quick solution to boredom, to a lack of social chemistry. It doesn’t matter if there’s no real connection if everyone is lost in themselves, be it for better or worse. When it gets bad for me, I’ll accept anything that numbs the clumsiness of this threadbare body, makes me a whole person, makes me connected. Despite my negative affect towards the rampant normalcy of substance abuse, the smell of vanilla ozone makes me terribly nostalgic.

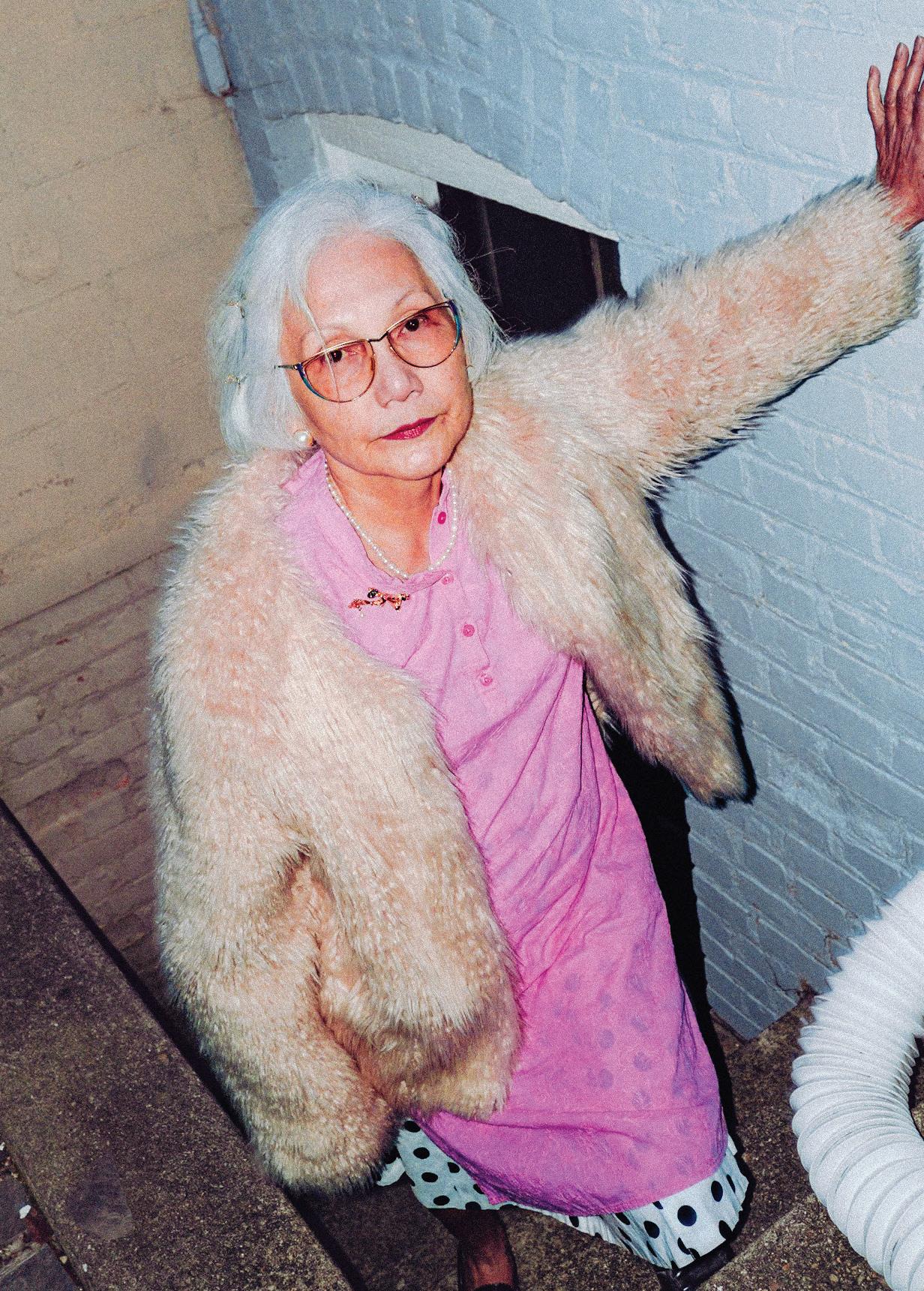

Written by: Kayana Jacobs

Photography: Amyna Dawson

There’s a rhythm to Loving Acres that feels ancient, like something pulled from the marrow of the earth. The air feels alive, humming with the sound of life. Dusk falls softly over the sanctuary, painting it with strokes of gold. In Chester, Virginia, down a road you’d only travel if you knew where you were headed, sits a house that’s anything but ordinary. A house where life spills over in its rawest form and pigs answer to names like Pringles.

Welcome to Loving Acres, a sanctuary and home led by Rachael and Melissa “Mel” Loving, a couple who show that queerness, resilience, and a wholehearted devotion to love and pursuing what brings them joy can spark change and offer a sanctuary. Their home unfolded around us, warm and livedin, as if the walls themselves had stories to tell. My girlfriend and I stepped into their world, welcomed to poke and prod through the tangled threads of their personal lives and business. Outside, the world was stepping into a new year. Inside, their son’s girlfriend, Tiana, stood at the stove, cooking collard greens — a slow simmer, rich with history and quiet superstition. The scent surrounded the room, wrapping itself around the moment. If omens are real, this was a good one. A sign of an abundant year ahead. Rachael and Mel sat across from us in an unintentional uniform, a pair of matching overalls, Rachael smirked, insisting it was a rare sight. We lingered in the kitchen, letting the weight of the day settle, trading thoughts like pocket change.

K: M: R:

Can you introduce yourselves?

I’m Mel, or Melissa Owens, and I am Rachael’s wife. I’m also a music therapist.

And I am Rachael, Rachael Loving, and I am the ringmaster of the sh*t show here at Loving Acres.

Rachael and Mel met in 1990. Their dynamic was friction at the start, thrown together by fate or a university’s random pairing system as practicum partners in their music therapy program. Mel was intense, driven, laserfocused on mastering every detail. Rachael? Not as much. She moved through the world with an ease that Mel found antagonizing, her approach to their studies more freeform than structured.

M:

We were very, very different people, and I did not like Rachael very much because she was not a very serious student. And I was a very serious student. So I just thought she wasn’t serious enough that it bothered me. But we ended up becoming friends, and I became friends with Rachael and her partner at the time. And then when I went back to grad school, we … What’s the right phrase to say this politely? We went home, we went to a bar, and I went home with her. We’ve been together ever since. That was April 4th 1993, we think. We kinda made the date up, but I think that’s when it was. And, literally, like, that was it. I was like, we’re gonna be together forever, but you need to know I’m never gonna tell my family.

The couple had been together for four or five years before Mel finally told her parents. It wasn’t about shame; it was more like a quiet reluctance.

The weight of expectations, the heavy presence of theological beliefs, the unspoken rules of family. It all lingered, unaddressed but impossible to ignore. Rachael never pushed her to come out to her family. “It’s okay. We’ll be together. You don’t ever have to tell you don’t ever have to tell your parents.” And for a while, that understanding was enough. It was comforting, even, to have that space to breathe, to let things unfold on their own terms. But as their love deepened and the years passed, it became clear that something so powerful wasn’t meant to stay hidden. Mel had been raised on the kind of love that endures. The kind of love that shows up every day and doesn’t shy away from being seen. The kind of love that withstands time and change. The kind of love that demands to be seen. Her parents were together for almost 70 years before her father passed away.

M:

I was not gonna hide it anymore. Anymore. Mhmm. Because I said to my parents, look. If I told you that I met someone who’s also a music therapist, who also loves animals, who also is very devoted to their family, who is kind, who treats me, you know, with respect and kindness and, you know, is wonderful to me, you would be thrilled. The only thing this person has or doesn’t have is a penis … Like, if I describe the person, you agree this is the perfect person for me.

I don’t know why I have no prostate.

M:

R: “What are you?” — She loves to quote Madea. But anyway, this is why she drove me crazy in college!

What was I saying? We’re very, very fortunate that as soon as we told our family, my dad, as a pastor, said, “I have to reconsider. I have to reread scripture with you all in mind.” M:

They reflected on how far they’ve come, pointing out how different things are now compared to 31 years ago. It’s a relief to be in a place where they don’t have to hide anymore, they shared. Back then, there was a real fear of Mel losing her job. Mel often talked about her cautiousness around being public, even questioning if they should put both their names on the same check.

I never thought about that sh*t.

She never did. Rachael is 100%. M:

Rachael never thought about the things that held others back. She’s never worried about things like what people might think or whether she’s conforming to expectations. She never hesitated, nevezr second-guessed, just lived her truth with unapologetic confidence. She’s had jobs that paid really well, in medical sales, where she was incredibly successful, but it was also brutal. It took a toll on her. She remembers a day she came home after a long shift, cleaning out the utility closet.

R:

M:

R:

I said no. And I’m not a huge drinker.

It was brutal. It was horrible. And it was not her. This is absolutely her. I mean, she did not know that this is what she was gonna do with her life.

Sometimes you don’t know what you want.

M:

K:

But she’s been rescuing animals since she was little. I mean, she would bring birds home. Her mom just tells all these stories about her care for animals. And I’ve always loved animals. I remember rescuing a bird that was drowning in Hawaii, and I dove out under the waves and brought it in. But the interesting thing is I’m not really involved in the day-to-day care of the animals at all because I work full-time and I really do more of, like, taking care of the house.

So this urge to nurture animals is kind of instinctual for the two of you? Could you tell me more about what made you want to build this sanctuary?

R:

M:

R:

M:

R:

M:

An accident.

Oh, really? It wasn’t an accident. It just wasn’t … it wasn’t what we planned.

Yeah, it wasn’t intentional.

Yeah. I always wanted a pig. I wanted a little pet piggy. Didn’t know anything about them. I didn’t know that there’s no such thing as a mini pig, that they get big! So Rachael got Pearl for me.

Well, we went to the state fair for chickens, she told me she wanted chickens —

Then she got Pearl.

The details of how the chicken purchase went to a pig purchase are still blurry in the long history of Loving Acres, but that was the start of their farming journey. A journey not as romantic as it seems, but more fulfilling than most.

M:

M:

I had always wanted a farm. But I didn’t even really know what that meant. It was just the romantic idea of having land and flowers and a garden. Not really crops, but a garden and some goats. Never ever ever wanted this, all of this. But once this one got started, once we got a pig and we needed a little more space, we wanted to have a little bit of land. We started looking, and I found this house.

The rest is history. We built a fence for Pearl, and then we got a goat, a baby goat, and we got sheep, and we were not rescuing any animals then. We just had three pets.

But, also, right before we got to this house, we took in Josh, our godson with autism, who’s now 34. Rachael stopped working because she needed to be home to care for him. So I’m the breadwinner, and we have all these animals to take care of, and it gets really expensive.

K:

R:

How do you manage the balance between housing all the animals and the economic realities of running a sanctuary?

Our lives just really, really changed. We stopped traveling. We used to take nice trips. We stopped going to dinner. We stopped going out and spending money, and we started just putting anything that we had extra into the animals and into making sure that we had what they needed.

R:

Rachael’s really the one who does all the work with the animals. I mean, she and the folks that come and volunteer. We’ve found churches that give us food that help us with the animals at least. People who donated their time to build fences. We got the army involved. They come every now and again and just clean up and stuff.

We had a very, very dear friend, sadly, who we lost to suicide, named Daryl, and he really pretty much built everything here. I mean, he’s the one. Very, very instrumental. It wouldn’t be without him.

M:

We met him when we moved in because he had a koi pond, and this place has a little pond. He just started coming around, and he was like, “These two women need help!” He built the chicken coop.

R:

M:

Mhmm. He did the bulk of the stuff to get us some real fencing. We had the barn here and the greenhouse, but none of the housing.

We just poured everything that we had into taking care of the animals. We gradually just did it, and it was not financially easy. We had to sacrifice a lot. We don’t buy new cars. We like to shop at thrift stores.

R:

M:

But the balance was very, very tricky. It’s still very tricky because it’s very, very expensive to take care of all of these animals.

The interesting thing is that Rachael knew nothing about farm animals when this whole thing started. And we would get a pig, and we had to learn how to take care of a pig. Got a goat, had to learn how to take care of a goat.

R:

K: My first time I did, I got my first two sheep, a boy sheep and a girl sheep. I had a sheep mentor in Pennsylvania, and we would shear the sheep because we wanted to shear the sheep. So, I had sheared Sunny myself, who’s still back there.

Your sheep, do you say you get them sheared instead of doing it yourselves?

I sheared him, and I was so proud. It took, like, two and a half days or so. It took a while. It should take, like, five minutes. They could do them in 20 minutes. So, I did them. I took them up there, and I was so proud. I showed her.

I said, “What do you think, Michelle?”

And she said, “Who sheared him?”

I was all proud and said, “I did.”

And she said, “You might wanna open your eyes next time.”

Taking in an animal isn’t just about giving it a home; it’s about rising to the responsibility of truly knowing and nurturing them. You don’t just wake up one day knowing how to take care of a sheep. Or a llama. Or a miniature horse. And you can’t just wing it. You have to learn. Rachael is dedicated to every aspect of animal care, even the parts that most people might shy away from. Fecal testing. Rachael’s desire to run her own fecal tests isn’t just about saving bread for vet bills. It’s about truly knowing what’s going on with her animals, right down to the microscopic level. Parasites, infections, the weird and wonderful world of gut health.

The way she sees care as something holistic, not just responding to problems but anticipating them, learning, evolving is inspiring. That same philosophy extends beyond just their health and reaches into how they use the materials these animals provide. The wool from their sheep doesn’t go to waste. Instead, it is carefully collected, cleaned, and transformed into beautiful, handcrafted felted artwork. What begins as raw fiber, a byproduct of care and maintenance, becomes something expressive.

R: All you gotta do is take a piece, and you just sit in front of the TV and stab things. It’s fun. You’re just watching TV, and it’s very cathartic. That’s all there’s to it.

M: You’re gonna have a lot of loss when you have a sanctuary, when you have a risk. Every one of them. You know you’re gonna lose a lot of animals. You’re gonna see a lot of terrible things that people do to animals, and there’s a lot of cruelty out there. You have to be able to stomach that and also make sure that you are still allowing yourself to process the things that happened that are difficult. You have to take care of yourself emotionally, too. Rachael and I feel very much that our job in this marriage is to make sure to make life easier for the other person. So do whatever you can when you know you really love somebody. To make the relationship easier.

R: I think, in the past two years, we have gotten into a really good groove with it.

M: But it was not without its ups and downs, because I didn’t wanna have a sheep living in the house. I still don’t want a sheep living in the house.

K: What’s her name again? Pierogi.

R:

Mhmm. can’t leave her in a wheelchair 24/7. So this year, we’re turning half of the garage into a barn, essentially, so that we’ll have stalls and housing for animals that can’t be out with a herd.

M: Yep. But it’s definitely not all sunshine and roses.

K: I think it’s funny how you asked for the pig first, though.

M: I shot myself in the foot on that one tonight. It’s my own fault. But let me tell you something. Nothing makes me happier than seeing my wife happy.

R: Oh, beautiful. That’s the sweetest thing you said all day.

M: That’s the only sweet thing I’ve said today? I’m a keeper.

R:

M:

R:

M:

R: Sweetest thing all year.

But really, this is our own little slice of paradise.

M: She’s pretty wonderful. She likes the Commanders.

R: I’ll take the Ravens.

M: It was a Commanders vs. Ravens game that we were on the way home from when we got married.

The best 2 minutes and 50 seconds of their lives. Their wedding day. On their way back from the Ravens stadium, they took a short detour to get married. In t-shirts and jeans, with their son and the only working wedding officiant, Rachael and Mel made their long-lasting love legally official. We sat in the living room watching their wedding video, which in true Loving Acres fashion, was captured not by a professional camera, but through a FaceTime call recorded by Rachael’s brother. It immortalized the moment in the most raw, unfiltered way.

M:

I’m leaving Friday to go to the Chinese Lantern Festival.

I don’t really wanna go anywhere because we’re great right here. She doesn’t let me hold her back. She wants to go. She goes, “Sometimes you just have to do [things] yourself.”

But you know what? She’s gone with her ex-girlfriend. They stay in a hotel together, at football games. I don’t care. I travel.

R: Let me tell you [what we did that night.] She was in her bed. I was in my bed. We went down to the bar, had a drink, came back up, and she went, “Oh, the Barbara Streisand special is on tonight.” Girl, that’s what we did. We watched Barbara.

CHAPTER II

disorder, I was familiar with the first image. I was vaguely aware of the second image, but it was veiled, a vague threat hidden behind the promises of beauty.

had me — has me — trapped in an abusive relationship with her: she takes the weight and in return I give her my energy, my passion, fistfuls of my hair.

You see edits and slideshows about how much creators love to starve themselves, subsist themselves on bland low-calorie foods. You see supermodels and

K-pop idols who are all leg, next to diets so skimmed down they wouldn’t sustain a newborn. Ask TikTok, and an eating disorder is a perfect way of life. An eating disorder is enviable; an eating disorder means you have more strength, more willpower, than anyone else. Even outside of those explicitly eating disordercentered communities, it persists. Influencers with millions of followers no longer get pushback for throwing around phrases like big back or calling others fatties or weak. They make videos about how great it is to be skinny and how to stay that way.

In the 2010s we saw a huge push towards size inclusivity. Gorgeous plus size models were everywhere and “Every Body is Beautiful” was an inescapable mantra. But if you had asked me, or any other plus-size person, we knew it was all surface level. Fatphobia laid dormant underneath it all. It didn’t matter that Barbie released a new line of dolls with different body types. You still had to be beautiful and right in other ways for your fatness to be ignored or tolerated, and it was hardly ever accepted or celebrated.

While plus-sized models were aphrodisian in underwear campaigns, people of all sizes on the ground still faced the daily weariness of societal pressures. In the late 2010s, curves were all the rage, but I still got called the “fat girl” at school and asked out as a cruel joke every other day.

And now we’re back to saying the quiet part out loud. In her article “Being dangerously thin is back in. Is the body positivity era finally over?” for The Guardian, Arwa Mahdawi says maybe it has something to do with Ozempic’s new widespread accessibility. Or maybe, as Leslie Vargas writes in “Thinness, White Supremacy,

and Fascism” for Afropunk, it has something to do with the everpresent lean towards rightward politics, which encourages people to be in tight control of their bodies in order to conform. At the end of the day, it leads popular influencers, like TikTok’s Slim Kim with nearly 200,000 followers and over 7 million

likes, to openly espouse that her “favorite thing is to be skinny” and her “favorite fear to not be.” Or there’s Liv Schmidt, who had over 600,000 followers before she was banned from TikTok. She was a personal favorite of mine when I was in deep. She’s made skinniness a brand: you can pay nine dollars a month to join her “skinny group.” You can learn to be just like her, only eating one spoonful of your plate and half of every packaged snack.

Social media now is a never ending barrage of body. Every single post has skinniness or lack thereof looming over it, and every influencer seems to think of nothing else. Here’s what to eat, what not to eat, how I look, how you look, how she looks and he looks. Here’s the shades of blue you should and shouldn’t wear so you don’t look fat, and here’s why you should cut gluten, sugar, dairy, Red 40, carbs, vegetables that aren’t green, fruits, red meat. Go paleo, go keto, get 10,000 steps, pilates, strength train … or, if you really want to get to the bones of it, here’s what you need: a calorie deficit. Plain and simple.

My eating disorder first reared its ugly head my freshman year of college. I had always been a little overweight and never felt very

secure in my body image. But in my first semester free will, a meal plan and depression lead to a lot of sudden weight gain. We’re talking three 5-piece Ram’s Coop combos a day, including that sweet tea; loading up on bags of cookies from Ram City Market, which would be gone in one hour; and, of course, you couldn’t

forget that daily large latte. It was just because I was eating my feelings, eating my loneliness, my fear, my discomfort. I didn’t fit in where I was. I couldn’t handle socializing, I usually ended up bailing not even halfway through any function I was invited to. I stayed in my dorm all day until my 6 p.m. classes and hardly saw

the sun. I didn’t know where I was going or why I was where I was. But I knew that food couldn’t hate me, so I kept eating it.

Then the crashout came after my fall semester. I’d gained all this weight and hated it. I hardly had any friends and everyone I wanted to be friends with was very pretty

and very skinny, and worst of all, I had a terrible moment of weakness that definitely involved a boy breaking my heart. January, for me, ended in a lot of nights alone on my floor, ugly sobbing, desperately wishing someone would come comfort me.

So I was uncomfortable everywhere I went. I couldn’t look myself in the mirror. And no one, it seemed, wanted to date me. To my mind I was ugly, and fat (assuming that was the worst thing to be), and weird, and unlikable. And I at least had it in my power to fix one of those things.

Leading up to this, I’d already been exposed to a lot of eating disorder content by way of Tumblr and TikTok. This moment in my life was not the first time I’d considered some of the bodydestroying habits I was now embarking on. I’d trawled many times before through cutesified Tumblr posts advocating

things like the “Hello Kitty” or “Draculaura” diets (which would require 500 calories, 30 minutes of exercise, and 10,000 steps a day — something that will kill you). I’d longingly watched a thousand TikToks of emaciated girls flexing their protruding hip bones and rib cages. And I’d often wished, staring at this content, that I’d one day be someone with that sort of “will power,” the determination to become as sick as possible.

So all that wanting had been building up in the back of my mind for years before this. It was a slow, gradual chipping away at the floodwalls of my brain until, bam, the walls broke and there it all was, rushing out.

All of a sudden I was severely restricting my calories, working out at least once a day, and obsessively tracking my steps to the point I would pace the block or even just my dorm late into the night to hit my goal. It was wonderful at first. Or, well, it seemed wonderful. The weight was dropping quickly, at least, but it didn’t take long before I started to become exhausted, angry and even less social than I had been before.

What didn’t help in all of this was college. I spoke to a classmate of mine who’s struggled with similar issues. She pointed out the competitiveness of it all, and I agreed: our culture is so steeped in diets and fatphobia, it seems skinniness has become a rat race. You can hardly go a day without listening to someone else casually describe their own

disordered eating habits. It’s all ”I skipped breakfast, I had a coffee instead, all I ate yesterday was a bag of chips.” And then all of that gets paired with an unspoken (and sometimes very spoken) judgement, because in the stringent beauty standards of artsy young adults, “not-skinny” is often the worst thing you can be. Fat people are very familiar with the quiet, judgmental glances and nonchalant exclusion from certain aspects of social life.

Of course this is all connected to the current state of social media, which bleeds into how we interact with each other in the real world. Every day I hear other students throwing around casual fatphobia, disparaging their own big backs or celebrating skinny queens.

It’s not just that. There’s also just the fact that big life changes — like starting college — can trigger eating disorder behaviors or cause relapses. For a lot of people, starting college constitutes one of the biggest changes they’ve ever experienced. All of a sudden you’re cities, states, or even nations away from all your family and friends. You’re expected to be an adult, to take care of yourself, to decide your own curfew and study schedule and eating habits. Life becomes out of control, and at the end of the day, eating disorders are all about control. Controlling your food intake, to control the way you look, definitely to exert some kind of control over the rest of your ungraspable life. But the moment you tip into

disordered eating, the moment your healthy girl arc turns into a toddler’s average calories a day and two hours of cardio? That’s the moment where things really do fall completely, utterly out of your hands.

I just wanted to fit in. That’s all it ever was for me. Since I was

a kid, I’d never felt in control of myself. I’ve had a chronic case of brain fog my whole life, I’ve always been a little socially inept, and I always had a lot of people talking over me. I never fit in. All I’d ever wanted was to find my niche, a group of people who I belonged in, who would care for me. I could not keep a handle on

The eating disorder was a liar.

Trust me. She lies to you. If I felt like I couldn’t get a handle on things before, well. My eating disorder came in like a tornado and absolutely ruined me.

That “fitting in” thing? My eating disorder destroyed that. All of

myself. I found everything I did absolutely humiliating, like I was constantly too much, constantly the elephant in the room. My brain told me that if I wanted control over my life, I needed to fit in with others around me, so that they could stabilize me. And culture said that if I wanted to fit in, I needed to be smaller.

a sudden I couldn’t go out with my friends for fear we would eat. I needed all of my meals to be perfectly planned. The last thing I did before going to sleep every night was plan out when and what I would eat each day, and any hint of that schedule being thrown off made me absolutely freak. Then when I did go out? Lethargy laid

heavy on me; I zoned out of just about every conversation because I was so damn tired, constantly convinced I would faint. And I got mean, snappy. I tried not to let it leak out, but your inner eating disorder makes you mean. I found myself suddenly so much more judgmental than I’d ever been — “I don’t look like her, do I? Oh, at

spots to press, the sensation of chunks of food stuck up in the back of my throat. I started waiting for my roommates to leave the house just so I could eat dinner, because I knew that if I ate dinner — just a normal amount of food! — I would go straight to throw it up. I pregamed parties hunched over the toilet, regurgitating.

Yes, I lost weight. It wasn’t worth it.

Because I also lost passion. I lost the energy to do anything except control the way I ate and obsessively exercise until I was dizzy. I sacrificed so much beautiful time with my friends, and I developed a new burning self-hatred like I’d never felt before. It was never worth it and will never be worth it to give in to an eating disorder.

You do not want to spend the rest of your life trapped in a binge/ purge cycle. You do not want to be 19 missing out on your friend’s birthday party because you had to leave to throw up in a public trash can. You do not want to be 25 unable to indulge in the catering at your wedding. You don’t want to be 40, some day, raising kids and trying not to instill in them the habits that control you.

It’s hard. It’s really hard to escape diet culture. It’s nigh impossible to go about your day to day without hearing fatphobia or about someone’s new diet or a comment on your body. Fighting off the eating disorder demon in the back of your head is a constant uphill battle, but it is the most important battle you will ever fight.

Why make yourself smaller in a fight to make your life better? If you have a hole in your chest, what will shrinking yourself do? It won’t shrink the hole. You’ll just shrink around it, until the hole is all you are.

The goal is to make your life fuller. There are so many ways to feel good that don’t involve shrinking. Eating food you love and that makes you feel good, mindfully. Creating and consuming art. Holding your friends close. You can not cure hating yourself with hating yourself. But you can start to chip away at self-hatred by replacing it with love, as much of it as possible, in whatever way you can.

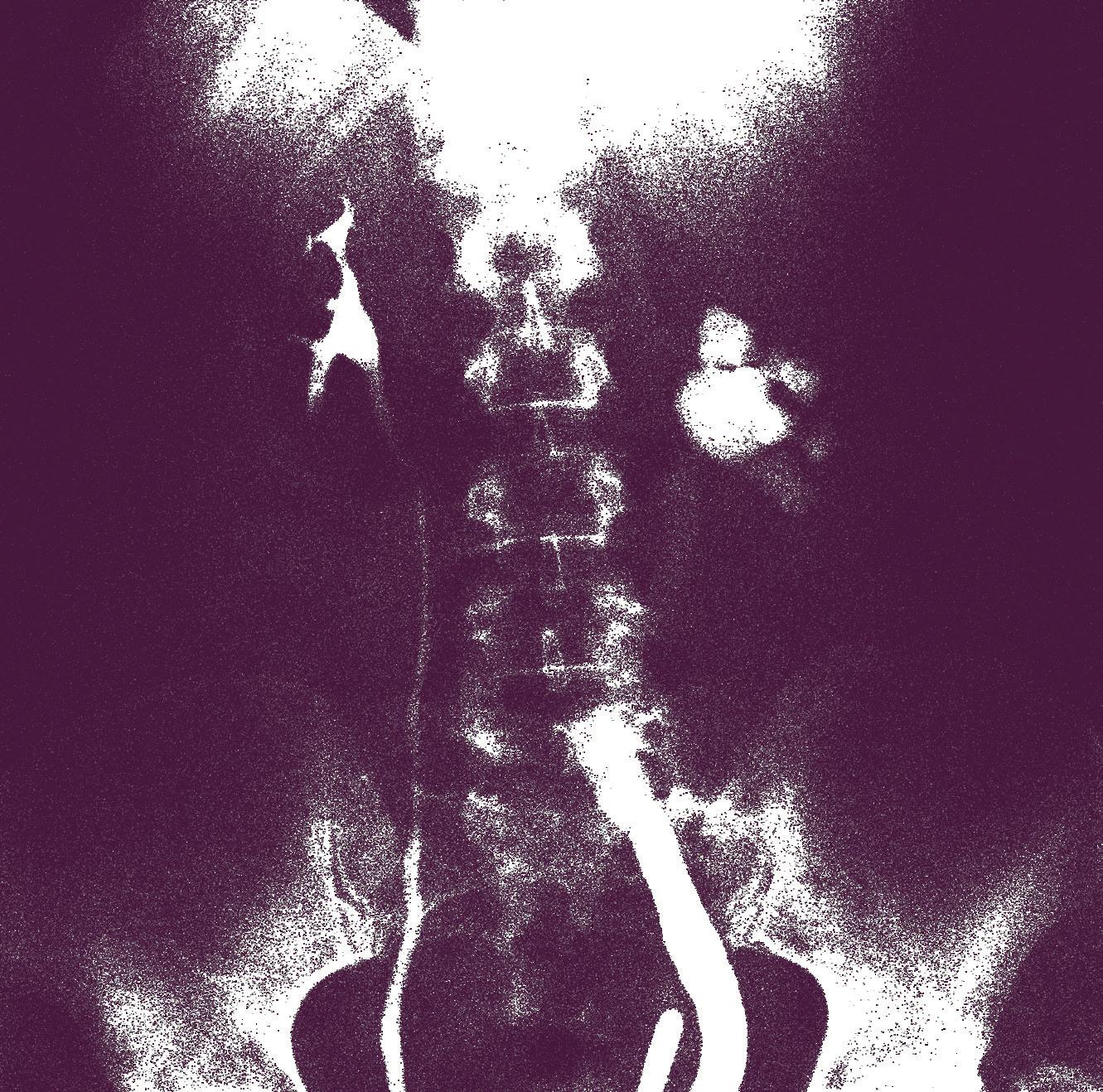

Photography: Caleb Goss

Models: Marty Alexeenko and Maeve Hickey

Creative Direction: Marty Aleexenko

For the longest time, there wasn’t a word that accurately described my relationship with womanhood and gender nonconformity. It wasn’t until I became enamored with a transgressive German film in my sophomore year of college when everything clicked, when I would find the word embodying my state of being.

While niche, the film still had academic articles backing its transgressive potential — this spiraled me down a years-long investigative journey, fixated on the macabre nature of the film itself, its meta-feminist, often shocking depictions of womanhood, and its relation to my unorthodox female experience. I became enamored, obsessed, infatuated, with the female grotesque.

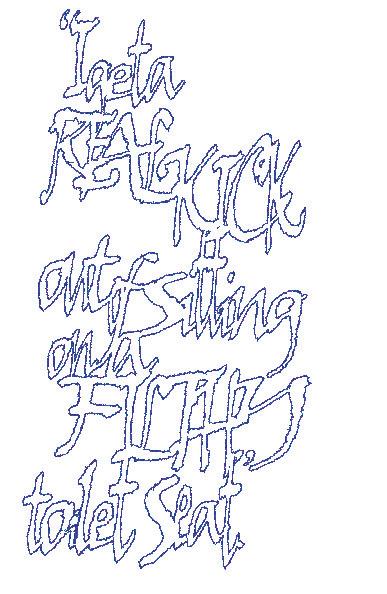

“Wetlands” follows the harrowing tale of Helen Memel, an 18-year-old girl with hemorrhoids. After a tragic shaving accident lands her in the hospital for an extended stay, she recounts her various deviant behaviors that lead her up to her moment in the trauma center, and it’s certainly not for the faint of heart. The tone of the film is abruptly set upon viewing the opening sequence: barefoot, Helen ventures into a flooded underground latrine. Through her monologues, we learn her prerogative: “I get a real kick out of sitting on a filthy toilet seat. The filthier the toilet, the better. I’ve been experimenting for years, and I’ve never even had a yeast infection … I couldn’t care less about hygiene … My goal is that it emits a lightly bewitching odor that you can smell coming from my pants. Men perceive it without realizing. Because we’re all animals looking to mate with each other.”

“This book shouldn’t be read or adapted to film. It’s nothing more than a mirror of our sad society. Life has so much more to offer than the disgusting perversity of the human heart.”

Many examples of this shocking sexual and hygienic deviancy are established throughout the film, such as Helen trading tampons with her best friend, Helen openly sharing her outlandish sexual fantasies to her love interest, Helen fidgeting with her medical waste, and Helen forcefully reopening her anal fissure to remain in the hospital with said love interest. Trust that this is all for good reason. It’s openly stated Helen can’t distinguish her dreams from reality — this concept of the female grotesque is built upon a woman’s actions in regards to her circumstances, after all.

Throughout the course of the film we learn how Helen’s dysfunctional family shaped her current state: her mother neurotic and unstable, her father jumping ship during her formative years. Helen would come of age in an overly sterilized, parentally absent dynamic, bringing along its own slews of trauma that she seeks to heal through her rebellious escapades. She finds solace in a series of misadventures with her best friend Corinna, from trading tampons to nabbing a situationship’s drug stash, but even this connection doesn’t last forever. Watching further into the film as Helen dives in and out of reality while recovering from her injury, we still go back to the central theme of how circumstance influences Helen’s magnum opus of transgression — the meta-feminism of the film, where I found meaning among the disgust.

“Wetlands,” as a film, was based upon the work of Charlotte Roche’s critically acclaimed debut novel “Feuchtgebiete.” The book caused its own stir long before the movie adaptation in the European press. At a surface level, the content is gross. It can be hard for the average viewer to stomach. The storyline of a young girl participating in overtly disgusting and sadistic sexual antics is bound to turn off general audiences, but in classic art school film analysis manners, we must dig deeper into Roche’s intentions. Metafeminism is defined by viewing feminism through a lens of disorder. “Wetlands” makes such a case. In a 2008 interview for SPIEGEL, Roche dives into her work’s controversial nature, utilizing the explicit content, her depictions of a woman in disorder, as a device for her core feminist narrative. When touching on critiques citing “Wetlands” as pornographic, Roche extrapolates: “That’s not what happens in my book. I’m more interested in masturbation and exploring your own body … My topics are the ones that concern everyone, but we don’t have the words for them. There are women who don’t even have a word for their own genitals. Men are better at that. I see it as my job to look where others don’t look. Where language fails.”

When asked about her views on the feminist canon as a whole, Roche points to the demands of “Wetlands” content, critiquing the status quo: “First-generation feminism always knew exactly how we women should behave. We lack that certainty. I have no idea where good behavior for women ends and bad behavior begins. I just want women to have the choice to go one way or the other.” This quote sums up the starting formula to pondering transgression in relation to feminism through disorder: pondering the female grotesque.

Defining the female grotesque requires deep introspection into the pillars of modern-day feminism. The standards of what it means to be a “good feminist” have long been held in the chokehold of affluent, cisgender, straight white women. Thus, opening the dialogue is essential to dispelling hegemony. Finding an academic source diving deeper into the meta-feminist context of “Wetlands” was my saving grace for finding the answer to the question: “What is the female grotesque?” It lies in the nature of a woman’s transgressive actions. “Wetlands” continues to serve as a paramount example of a context in which female transgression exists, albeit in a very overt manner, but nevertheless deserving of extended dialogue.

In “Rethinking Transgression: Disgust, Affect, and Sexuality in Charlotte Roche’s Wetlands,” author Helen Hester argues that the novel’s transgression comes through its depictions of human nature, rather than the sexual content itself. Hester cites the public journalistic response to “Wetlands” as a reaction to the “discourse of an organically occurring link between the concepts of the transgressive, the pornographic, and the feminist.” The public has been pondering feminism solely through depictions of women’s sexuality, rather than the potential for

a woman to be disgusting completely outside of a sexual perspective:

“The critical reaction to Wetlands is influenced by the repressive hypothesis and is tied to the now-conventional notion of sex and sexual speech as culture’s privileged locus of transgression. It is for this reason that the role of disgust in the text remains largely ignored.”

Building on the media’s reception of “Wetlands,” Hester hammers in the importance of the distinction between the “graphic depictions of the abject body, having been inappropriately labeled as pornographic” versus the actual pornographic elements of the book itself. These statements allow us to further pinpoint what it could mean to be transgressive beyond the general perceived canon.

Helen’s actions throughout “Wetlands” serve more as allegory rather than an explicit answer for transgression. Thankfully, Hester assists in finding a definition beyond the act of being disgusting or being overtly sexual: “Transgression need not be loaded with the ideological weight of disobedience or rebellion, but can in fact take the form of a relatively neutral act of boundary crossing … Even as the association of sex with transgression is endlessly reiterated, it is showing signs of wearing down and losing its hold over the contemporary imagination. Sex is beginning, perhaps, to lose its status as a particularly privileged and iconic site of transgression.”

Media has long been plagued with the idea that transgressive female characters must play a dominant role through their sexuality. The examples cited in this article have shown how such depictions have been a detriment to pondering female transgression beyond a sexual context. The subject of sex is the most surface level branch of thought for art to tap into. Nevertheless, “Wetlands” has used audience arousal, and the controversy of the journalistic storm, to propel the female grotesque to the mainstream.

Transgression is not always overt — it’s more than just physicality, transgression is a practice, one that you may be exercising. You? Embodying the grotesque? It’s more likely than you think. Hyper analyzing ‘Wetlands” was only the first step in coming to terms with my lack of normalcy with gender. Soon, I began to examine the transgressive nature of my life as a whole.

Want to get a master’s degree? Grotesque. Want to lift weights? Grotesque. Don’t tweeze your unibrow? Grotesque. Married to your work? Grotesque. Hustle two jobs to eat? Grotesque. Do we have anything in common? You could be grotesque.

Embodying the female grotesque serves me great importance, having grown up queer in a conservative family. The Russian Orthodox traditionalist structure of my mother’s side and the radical red American standards from my stepfather’s side will haunt me forever. I live with the shame of embodying their worst nightmare, and I live with the joy of my brutal, independent, grotesque state.

My stepfather always pesters me about the mysteries of my adult life. He doesn’t understand how much I work. I speak nothing of it, but maybe one day I could tell him: “When there’s no longer holes in my socks, when I’m no longer eating all my meals from cans.” Self-sustaining is grotesque.

He couldn’t stand to be seen next to me, in the street, at parties, around his friends. He was well aware that my presence made him look queer. I’ll never forget how I’d let my knees bleed into the gravel. He couldn’t look me in the eyes when he was sober, but I’d spat him on the floor. He said he could never see me recovering, yet I’d wrapped around him like a python. He told me my face hurt to look at, and I told him I would lick the pavement he pisses on. To exist as an impossibility to hegemonic dynamics is one of the many burdens of transgression.

To rationalize my existence sometimes feels like I have to use every muscle in my body to wade through a thick pool of mud. Even when I’m out, the dried sediment is forever stuck in every crevice of my body, difficult to scrub out.

The female grotesque, foremost, is queer. I realized I identify so much with the concept of “grotesque” and meta-feminism as a whole because the mainstream feminist canon does not apply to me — because I am not a cisgender woman, nevertheless, feminist issues are still something I must ponder. Every day I conjure up new allegories of the female grotesque: Butch swag, Kreayshawn, Lady Gaga’s 2009 performance of “Paparazzi” at the VMAs.

To recognize it is to keep it in practice, to see it in others. As much as I joke in regards to meta-feminism, I truly think about it all the time, because it’s the only concept I’ve ever felt applies to me.

My gender nonconformity impacts my life in many different ways that I see every single day. It’s the way people look at you when you walk into the store, the way your academic peers perceive your work, the way your employer treats you, the way other queer people see you.

I often wonder if the grotesque is a curse, a burden I must bear until something sweeps me up out of this “phase,” until I’m saved, but then I remember how long I’ve been living it. What began as questioning the inherent politics of women in skateparks at age 18 has now, through my adulthood, become an exercise in my disorder.

Written by: Walker Cosby Graphics: Aisha Virk and Marty Alexeenko

I was 18 when I found out I was trans. For two years now, I’ve known I’m a girl. It’s always been a matter of hemming and hawing, fighting with fabricated versions of myself. A clash of personas, forever winning and losing miniature battles inside my brain, creating this territorial stalemate of abstract people that all form into my ego, none of them having enough control over myself to define who I am. Emotional suppression led to a facade of myself being created, one that only existed to be present in the moment. I felt like it was better for something to be verbally present. Maybe I’d eventually find my true self.

In my youth, it was hard for me to make friends or talk to people who I thought were cool. I had low selfesteem on top of these mini identity crises I was going through. So, I found myself ensnared in this group of altright cis white guys as my friends for all of high school. I was always deemed too sensitive by them, not able to handle their microaggressions and misogynistic humor. Never “able to take a joke.” I eventually lost my sense of self, my morals, my superego to this cesspool of cruelness. And I just let it all happen.

Like most edgy teenagers though, I found solace in music, especially in my junior and senior years of high school. In my anxious post high-school jitters, I found “Spiderland,” the defining 1991 posthardcore record by Slint. “Spiderland,” as suggested by its title, creates an emotional space beyond conventional music. The six track record intricately spins a web-like narrative into their harmonics, slow drums, and spoken word, stepping with you into a pale grey void of fortune tellers, vampires, pirates, drunken fools, and the inner thoughts of four lonely teenagers from Kentucky.

It felt like the queer high school awakening I never had. They’re gritty and loud, not afraid of anything; the star of the show. When Friend came to Richmond a few months ago, I requested they play “Say My Name,” a song written by Autumn about being a trans girl. It follows the dog motif of the album it was released on, “Dog Eat Dog.” Many of the other tracks on the album follow themes of feeling like or being treated like a dog, such as “This Dog Don’t Bite,” with its imagery of being treated poorly for not doing what you’re told, or violent nature associated with those who disobey cruel directions. but none speak to ideas of

With its increasingly loud buildup, stacking bass on top of distortion, and its chilling pre-chorus, “Always call me, never say my name,” building up to a shaky cry of “Say my name,” I knew it was a special song. I had to shove myself up to the very front, where I was eye level with them. Beyond myself, I felt like a girl in a way I never had before. And Autumn could tell I was. She looked at me dead in the face while we both screamed the lyrics, until I was eventually hunched over gripping my sides in some attempt to open up my ribs so I could keep yelling without having to stop to breathe. By the time the song was over my chest hurt so much I could barely move. It felt like we were the only two people in that entire room. In a way, Autumn saw me in a way no one else had. They gave me the setlist after. I knew I had to be like Autumn.

When I began questioning myself, it was an overly long stage of denial. In truth, I didn’t want the answer to my identity crisis to be that it’s because I’m a girl. Being trans in this time is really scary. I didn’t want that to be my solution. Like most harrowing days of painfully personal inner questioning, I dug through my childhood memories in an attempt to find any sort of evidence of these revelations. My bottling up of emotion led to memory loss, and I don’t even really remember a lot of my childhood. Thankfully, I was able to return to some later high school memories with clarity, specifically from a special place that always gave me comfort.

Revisiting “Spiderland” was a whole different experience. Now, I often put on the whole album, and can’t do anything else until I finish listening to it. I’ve actually been trying to listen to the whole album each time I sit down to write this.

Slint gives me a space to exist as I was before, now with a new understanding of myself and a truer lens of how I want to see myself. Through my many walks in “Spiderland,” I found out that, no matter what has happened or what will happen, I’ll always be a girl.

While Slint gave me a place of solitude after I had defined the glass box, Friend, and specifically Autumn, helped me figure out how to step out of that glass box, and actively lay out the floor plan for what I want to do with my music. Autumn was able to, with the help of their band, make my dread fizzle away with the bleating of their angsty queer punky attitude. Through my own music, I want to create a space safe for all party people, myself included.

In my restless contemplations, flaking at this version of myself who’s been bloodied and scarred by himself and his youthful tendencies to never reach out for help, scavenging away to find my true morals and feelings, I feel I’ve finally come to realize what’s really going on. At least I hope I have.

The trans experience right now is super hard. I feel, in a way, that I’m still trapped in my glass box, still stuck in Spiderland. I still feel burdensome, and I still feel like I can’t talk about myself, because I don’t fully understand myself. Parts of me feel like I shouldn’t even feel trans because I lived such a heteronormative lifestyle. But in a way, that is my own trans story. I felt such shame from feeling so sensitive and detached from this masculine lifestyle the way I did in my youth, such guilt and fear of rejection. But I guess my story was just unexpected. A friend of mine once told me in relation to this, “Everyone finds out about this kind of thing at the right time.” You’re never too old, but you can be too late, if you submit yourself to hatred. Listen to yourself first, and step out of Spiderland. The music will always exist there.

CHAPTER III