SHAPING MEMORY

Archiving

As Creative Practice

by Mkutaji wa Njia

Supported by

4

5 Contents 01 Introduction 02 Archiving as Creative Practice 03 Histories, Legacies and Memory 04 The Living Archive 05 The Story of VANSA 06 Creating Our Own Archives 07 Conclusion 08 Acknowledgements and Contributors 09 References

Immersing oneself in the work of artists and creatives of a generation provides a unique understanding of the inner workings of the social, political and economic landscape of that generation. The widely celebrated words of musician and activist Ms. Nina Simone come to mind when she said, “an artist’s duty is to reflect the times.”

An important component of reflecting on experiences is the task of documenting those experiences as a space of reflection and for generations that follow. Some may find the ‘traditional’ role of archiving as it has been exposed through colonial pedagogies to be obsolete as it often objectifies an experience and creates bounds to how a moment can be remembered. This reluctance is valid and true. Similar to many practices, our perception of archives has been largely formed by the ways in which European and Global Western institutions approach the politics of power and memory. This has influenced what we remember and how we remember. Our histories have been painted with brushes that were made in distant lands, foreign to the mediums they seek to embellish.

The question that then arises is ‘how can we shape our memories in ways that resonate with our own methodologies?’ By ‘our’ memory we refer to the African and indigenous experience that we collectively relate to in the age of modernity. How can we honour the storytelling processes of our ancestors and make meaning through embodying our own forms of remembering.

7

1.Introduction

Who:

The Visual Arts Network of South Africa (VANSA) in collaboration with RADAR (Loughborough University’s contemporary arts research programme), has developed this archival project that seeks to expand on the creative work already being done by the two organisations. VANSA’s purpose to preserve, present and protect work in the creative industry, coupled with RADAR’s process-led approach has inspired this project. Over the past six months (JulyDecember 2022), I as the VANSA creative archiving fellow in collaboration with artist Libita Sibungu developed an online talk programme which brought together the work of four Namibian and South African artists. This talk series has largely informed the approach towards writing this publication. Through these talks we have built and dismembered ideas around the archive, what it means to us as contemporary African artists and how we can take charge of writing and developing our own stories.

This publication is an attempt at illuminating some of the moments that are shaping archiving in the visual arts space in South Africa and parts of our continent. Here we will unpack the collaborations between artmaking as a channel in which memory can be captured, and archiving as a creative practice. Part of the mission is to explore how artists engage with established archives preserved by nation states and formal institutions that paint the historical memories of our communities. The second task is to tell the story of how artists and arts organisations document and archive their creative work as a way of awakening the living archive. The final element of this publication will be to commemorate the past 15 years of VANSA’s work in the creative industry and how some of the programs and collaborations have influenced the trajectory of the visual arts not only on the African continent, but in many parts of the global south.

This publication can be viewed as a written series of working thoughts on how we have come to understand meanings around the archive over the duration of this project. As they are working thoughts, these ideas may cease to resonate with us in a few years or even months. However, that is the beauty of the archive, it is a space to trace how we form and dissolve ideas as we evolve as individuals and communities.

8

What to Expect:

The structure of this publication begins with exploring the necessity of archiving. Is it important to archive, if so, why? These are some of the questions that will be addressed in the beginning section. A short introduction to the Shaping Memory Talk Series follows. The following section dives into the histories, legacies and memory we have inherited through both institutionalised forms of archiving and embodied, ancestral knowledge. This section also introduces the necessity of tracing, questioning and disrupting the ways in which memory has been shared with us from the colonial perspective.

The living archive is the section that follows, which presents some of the lessons from artists and cultural workers on how they engage with archiving as a way of remembering the past and imagining the possibilities of the future. The publication then traces the story of VANSA’s 15 years of organising in the contemporary arts sector of the African continent and its diaspora. Various projects and programmes that have shaped the ecosystem are points of particular interest in this section. The final section of this publication shares ways in which we can continue creating our own archives as well as some of the practical things to consider.

9

The archive is a space to trace how we form and dissolve ideas as we evolve as individuals and communities.

2. Archiving as Creative Practice

Why Archive?

For many creative practitioners, the concept of archiving may seem obsolete and unnecessary. The point of ‘making art for art’s sake,’ is central in most spaces, where the intention of artmaking is to create for that moment and to not be distracted by the necessity to document. Having to think about how to document work for people in the future is a task that many may not see the value in. This perspective is valid.

There is also another perspective that seeks to share the value of documenting our work, not only for those who will come after us, but for ourselves to reflect on our journey. In an attempt to illuminate the importance of developing our own archives, the words of previous VANSA director Refilwe Nkomo come to light. She said, “When we know ourselves we cannot be told who we are.” The archive is a space to interact with self and community in unique ways that other spaces may fail to fully embrace. We can create a deeper sense of understanding ourselves and our communities when we are able to trace the evolution of how we came to be where we are now. Simply put, the archive is a space that traces our becoming.

In the same way that individuals and collectives tune and develop their artistic voice through process, archiving is a process-led endeavour. Where each step of the way is as important as the next. The outcome may be difficult to discern, however the labour itself creates its own lyrical journey. Contributing to an archive can be as simple as saving a voice note on your smartphone, or making a note of an experience that inspired you to imagine. Though this publication may present some suggestions on how to consider archiving, creating your own systems of remembering that resonate with you is the overall message.

11

REFILWE NKOMO

“When we know ourselves we cannot be told who we are.”

Shaping Memory Talks: Lessons from Artists

and Cultural Workers

Over the last two weeks of October 2022, Libita Sibungu and Mkutaji wa Njia produced and co-facilitated four online talks with a medley of artists and cultural workers with origins in Namibia and South Africa. Memory Biwa, Libita Sibungu, Lebohang Kganye, Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja and Tšhegofatšo Mabaso each presented the possibilities that rest within the archive. The task these artists have taken on is one where they have accepted to be bent and sometimes broken by their practice. Surrendering to the process that makes them whole.

The lessons from this talk series resonate in many ways with the contents of this publication. Each guest shared perspectives on the archive as an institutional and colonial way of capturing memory, along with the embodied and living archives they are creating within their art practice. Reflections from the talk series will find their way throughout this publication. As a way of drawing parallels between thought and practice through the experience of these five artists.

12

The task these artists have taken on is one where they have accepted to be bent and sometimes broken by their practice.

3.Histories, Legacies and Memory

What Is The/An Archive?

The ways of documenting and recollecting a moment have expanded in the same ways that nations, institutions and systems have evolved. We learn from Artwork Archive that traditionally the archive was, “A collection of documents or records that provide information,” that reflect, “ how we go about saving and organising histories, preserving our pasts, recording our presents and bringing insights into the future.”

On a basic level one can view the archive as a repository of information on stories of the past, ways of making sense of the present and imagining the future.

Many institutions can be considered to be archives such as museums, libraries, schools, art galleries, government buildings and even homes. Some of these spaces often house elaborate catalogues of materials in the form of photographs, documents, records, sketches, audio tracks and so forth that are categorised and classified.

15

IMAGE: District Archives Leiria, Leiria, Portugal, Photographer: Catarina Carvalho, 29 June 2018 (detail)

We learn from European scholars such as Eric Ketelaar and Terry Cook, who have spent much of their professional life on developing the archival space, that the archive should not be seen as static, the context in which it exists has and will be reworked over time.

Simply put, the archive’s responsibility is to reflect the times as they change and transcend. The evolution of archives has created space for various types of information to be included in recording. In creative industries art practitioners have documented through;

• exhibitions and exhibition catalogues,

• recording events

• books

• notes

• sketches

• journals

• photographs

• press releases

• clothing and accessories

• recorded conversations

• workshops

• websites and social media

• studios etc.

IMAGE: Vinyl collection at a record store, Lyon, France.

16

Photographer: Fabien Barral April 22, 2016

Whose Memory Is It Anyway?

The question ‘who reflects?’ is one that is central to dealing with the archive as it has been shared historically and how we create our own forms of (re)collection. The words above were iterated in a short film titled Whilst You Archive Me by the collective known as Decolonising The Archive (DTA).

Some of us may have come across the phrase, ‘history is written by the victors.’ Whether it be the winners of a war or those who have imposed socio-economic power over a majority, usually the story is told through those who have exerted power as it is understood through the political lens. The archive has been masked with the same legacy, where systems of collecting, reflecting and retelling have been exposed through the eyes of the uninvited takers of indigenous land in Africa and its diaspora. The alienation of black artists, and scholars from the archive has created a distrust of the archival space.

It is because of this reason that many choose to reject the archive as a way of recording and organising our histories. The archive has been used as another way to continue to deceive, oppress and miseducate African and indigenous people all over the world. The archive has also been a space of violence and struggle for many. The pain of revisiting the tragedies of our pasts that were imposed on us in spaces such as museums and libraries, often told through the perspective of these colonial institutions, is another reason some prefer to dismiss the archival space.

“Picture me, write me, digitise me, But whilst you archive me, don’t undermine me. Get me right, correct, bright. Put my truth and stories to light. But whilst you archive me, don’t undermine me.”

REALISED BY NADEEM DIN-GABISI, CONNIE BELL AND ETIENNE JOSEPH

17

How We Got Here: Historical Context

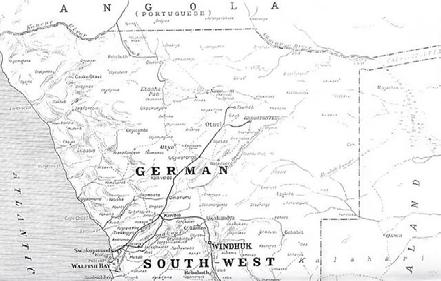

Part of the established archive are the parallel journeys of Namibia and South Africa. The artists who gathered as part of the Shaping Memory talk series have origins in both of these nations, and the history of these two states has affected their practice. The complex histories of both Namibia and South Africa form as the overarching backdrop for these artists to question, dismantle and contribute to the archive. Both were colonised by European nations that extracted minerals, wealth and used black bodies for labour.

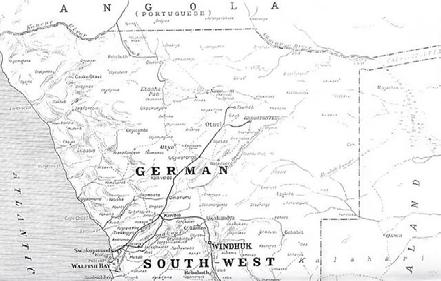

IMAGE: German South-West Africa (north), 1914-1915, Author unknown

Before the Berlin Conference of 1884 where our continent was cut up and divided amongst its invaders, Africa was a borderless topography with different communities that crossed over what would be considered a border today. There are many linguistic, ethnic and cultural ties between groups in both Namibia and South Africa. The indigenous people of Southern

Africa (often referred to as The Khoi and The San) occupied the land before the migration of The Bantu from Central Africa over 3000 years ago. The Germans, the Dutch and the English invaded parts of Namibia and South Africa, each occupying different parts. Namibia was named ‘Southwest Africa,’ and to this day South Africa still holds its colonial name.

18

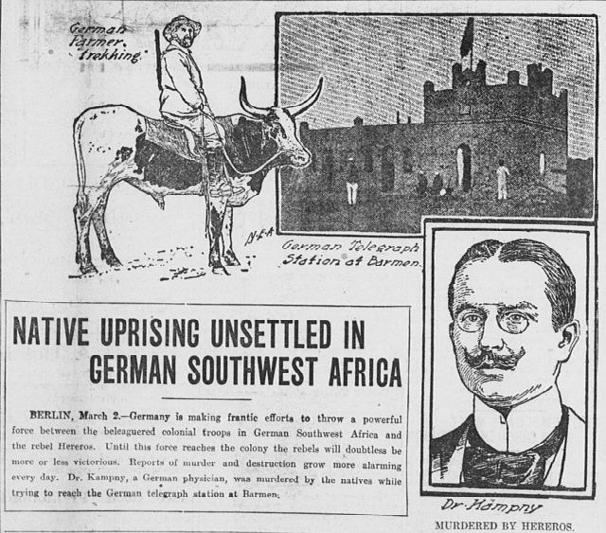

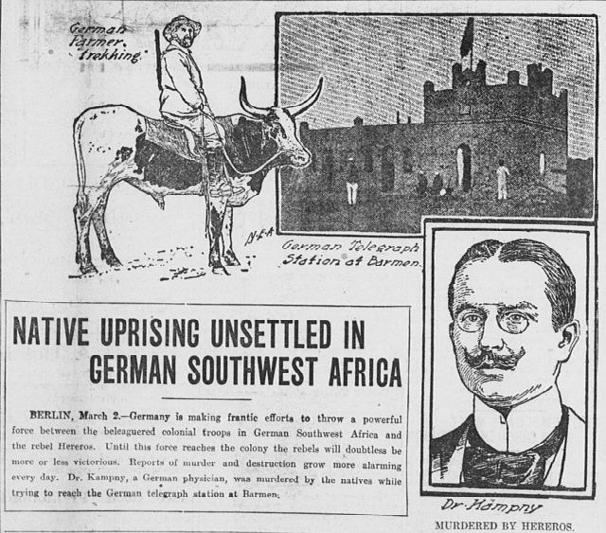

The first genocide of the 20th century occurred between 1904 to 1908 where German troops killed and brutalised Ovaherero, Nama and Damara communities. It is estimated that over 100 000 people died. Memory Biwa shared in her talk the story of Elder Hendrik Witbooi who was a chief of the Nama people and one of the leaders who led the revolt against German arms in 1904. Those who were not killed immediately either fled the territory, or were sent to concentration camps and used for free labour by German armed forces leading to the death of many more. In 1948 when the National Party came into power in South Africa, they also took over Southwest Africa, giving them power over both nations. Colonial occupation transformed into Apartheid which infected the two nations for more than four decades.

19

IMAGE: Images from German South-West Africa during the Herero Rebellion, Upper right: a German telegraph station at Barmen, Lower right: Dr. Kampny, a German physician 1904

It is estimated that over 100 000 people died.

In 1960 The South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) was formed in Windhoek, advocating for the nation’s independence from South African rule. Leaders of SWAPO, such as Elder Andimba Toivo ja Toivo, were sent to the Maximum Security Prison on Robben Island to join leaders of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), The African National Congress (ANC), and other liberation party leaders for acts of treason and other charges against the government. On 21 March 1990 Namibia gained ‘independence’ from South Africa with SWAPO as the ruling party. Soon after, South Africa became a democratic state, led by the ANC.

20

IMAGE: Chief Hendrik Witbooi (centre) and his comrades between 1894 and 1904, Author unknown]

The histories of these two nations is important to take note of as a way of contextualising the work of artists who engage with the archive.

The histories of these two nations is important to take note of as a way of contextualising the work of artists who engage with the archive. There is immense violence and trauma in the stories of

Namibian and South African communities. There is also a great deal of resistance, strength and freedom in the lives of our ancestors who refused to be contained, deceived and victimised.

21

IMAGE: Forum in Amsterdam De Populier, Vote now for freedom in Southern Africa, Motsipe (ANC) Kaukungua (freedom movement SWAPO), Photo by Dijk van Hans / Anefo 29 March 1981]

Disrupting The Archive

The words above were shared by Elder Mbembe in one of his most celebrated public lectures titled, Decolonizing Knowledge and the Question of The Archive at The University of Witwatersrand during the Rhodes Must Fall Movement. Elder Mbembe and Elder Ngugi wa Thiong’o encourage

the need to decolonize the archive as it is a space that opposes possibilities. The work of shaping memory includes creating a space for possibility to exist. Eurocentric canons are often told as a single, monolithic truth, removing the possibility for different perspectives to come to light.

“Yet the Western archive is singularly complex, it contains within itself the resources of its own refutation. It is neither monolithic, nor the exclusive property of the West. Africa and its diaspora decisively contributed to its making and should legitimately make foundational claims on it.”

ELDER ACHILLE MBEMBE

22

Our histories are filled with struggleand - they are overflowing with joy. Our stories are not single narratives, they are composed through a multiplicity of layers. The practice of decolonizing the archive invites the possibility for more than one thing to be true.

Elder Mbembe also references the important work of Elder Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of The Earth. They both place the importance of reshaping our methods of organising, to align with our own multilayered ways of being. Elder Mbembe said;

“Decolonization is not about design, tinkering with the margins. It was about reshaping, turning human beings once again into craftsmen and craftswomen who, in reshaping matters and forms, needed not to look at the pre-existing models and needed not use them as paradigms.” Disrupting the archive means questioning

and challenging the ways that we are taught to remember rather than simply accepting the models we have inherited. Many African artists are dealing with the archive in disruptive and regenerative ways. The following section of this publication titled ‘Shaping Memory Talks’ shares how some artists have managed to redefine the archive through their work.

IMAGE: November 2016 Protest led by The Economic Freedom Fighters in Pretoria for Free Education. Photo by Pawel Janiak, 27 January 2017

IMAGE: November 2016 Protest led by The Economic Freedom Fighters in Pretoria for Free Education. Photo by Pawel Janiak, 27 January 2017

23

4. The Living Archive

Shaping Memory Talks: Lessons for Artists and Cultural Workers

The Shaping Memory Talk series unearthed many ways in which artists on the continent and in the diaspora are engaging with the archive. One of the greatest lessons is how the four artists are actively questioning, regenerating and creating new meanings outside of the traditional archive. The living archive appears to exist with no bounds, few guidelines, and no discipline. This part of the publication shares some of the processes and methods used by these four artists to shape their role in the living archive - the embodied archive that lives, breathes and changes.

Memory shapes the living archive through the process of collecting and composing reenactments of moments in history.

Histories and Possibilities with Memory Biwa

Memory’s work teaches us about the everlasting ties between ancestors and the living. Where the experience of ancestors continues to affect those that are living. Memory shapes the living archive through the process of collecting and composing re-enactments of moments in history. Channelling these stories through photography and soundpieces; she collects, composes and shares the stories and possibilities that rest in the archive. One important moment in the history of Ovaherero, Nama and Damara communities is the attack on chief and political leader, Elder Hendrik Witbooi, which subsequently lead to their death. Memory unearthed this moment in the archive by creating a re-enactment of this attack through a single photograph

that can be stored in the visual archive of Namibia.

Listening at Pungwe, is an interdisciplinary project formed by Memory in collaboration with Robert ‘Chi’ Machiri which exposes parts of the collective archive through original and remixed soundpieces. This archival offering, as Memory explains, opens up technologies of the body and instruments offering infinite possibilities of remembering. An “unmediated voice from the past.”

26

SunBorn Lullabies and Battle Cries By Memory Biwa

IMAGE: Memory Biwa

Negotiating with The Archive: Tšhegofatšo Mabaso

Artist, curator and researcher Tšhegofatšo Mabaso shared with us her journey with responding to, understanding and producing archives as a way of negotiating with institutions. Through her practice, she confronts institutionalised concepts of archiving and how they are often in contestation with more embodied forms of knowledge. As a curator, they create spaces for other artists to negotiate and respond to the archive.

The question of whose knowledge gets to live in institutions is an imperative part of Tšhegofatšo’s practice as she examines how Western institutions select and reproduce specific histories.

27

IMAGE: Tšhegofatšo Mabaso

Archival Friction: Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja

The work of Nashilogweshipwe responds to colonial archives by dancing in the space of the undisciplined and uncontainable. The Oshiwambo word, ‘oudano’ which means ‘to play,’ is how they enter their practice as a performance artist.

Nashilongweshipwe puts into conversation different types of archives, creating in the space that exists between the established and the informal. “Archival Friction,” is what Nashilongweshipwe has named their process. For instance, when working with colonial photography they also draw from the memory of their body and the inherited knowledge of place. In their words, “...the memory of place, what places

remember, what bodies remember.” The embodied archive plays a significant role in Nashilongweshipwe’s practice especially when performing traditional rituals such as Ngoma, in colonial archiving spaces such as museums and art galleries.

Part of disrupting the archive for Nashilongweshipwe is working through the archival work of queer resistance, queer strategies and the evolution of African queer theory. Their curiosity lies in “what is considered archivable,” in terms of ideas that are included in the national and societal archives of Namibia. For them, queer represents that is undisciplined and cannot be contained.

28

IMAGE: Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja

The Power of Process: Libita Sibungu

In her ongoing project, Quantum Ghost, Libita uses photograms, made by hand, and looped audio to expose the topographies of the environments where they find their origins. Walvis Bay in Namibia and Cornwall, UK are the sites where they question the relationship between land and body.

The geographic histories of these two sites are similar in that they are both abandoned spaces previously used as

extraction zones for mining minerals from the earth. Part of Libita’s process in archive making was to collect earth and record sounds in these two places. Through her work, Libita teaches us to place the process at the centre of the living archive. Where collecting and creating elements that will form part of the final archive is the beauty of the living archive.

Interview with Libita Sibungu, Quantum Ghost at Gasworks

29

IMAGE: Libita Sibungu

The Imaginary: Lebohang Kganye

Lebohang’s shares with us the value of understanding the past not only as a way of reflecting on history, but as a channel of imagining and a space to create fantasy. Imagination plays a key role in recreating moments of the past, especially moments that occurred before our time. When all one has is the stories and photographs shared by others, there is space to reimagine how the moment played out.

Through photographs and audio-visual processes, Lebohang combines the journey of her lineage with the social context with which her ancestors were practising their sense of being. She frames the landscape through clothing, set design and in some cases audio, to recreate moments in her family’s past. Her work teaches us of the power in the living archive as it searches for shape and form while capturing ancestral and emerging histories.

Lebohang Kganye’s Website

30

IMAGE: Lebohang Kganye

Her work teaches us of the power in the living archive as it searches for shape and form while capturing ancestral and emerging histories.

5. The Story of VANSA

The Beginning

In 2002 a group of artists and cultural workers came together with the intention of disrupting the historical racial and economic imbalances of contemporary art in South Africa. The Visual Arts Network of South Africa (VANSA) was born out of the need to amplify the voice of what would have been considered to be ‘alternative’ at the time and to deepen the channels of access and information for emerging black artists.

The collective took on the form of a loose association of individuals who were concerned with the challenges that young, African artists were facing at the time. The committee members volunteered their time and resources to establish a structure that lobbied for more public investment, access and funding for the contemporary arts. The organisation also placed the need to develop channels of support through training, workshops, employment and membership at the centre of its work in the arts sector of the continent.

In 2006 the Growth, Transformation and Opportunity conference was hosted in Cape Town by voluntary members of VANSA. This was the first national conference in the visual arts sector since 1978. This conference hosted visual artists and industry workers all over the country and some from parts of the African continent. This conference is often referred to as the ‘official’ beginning of VANSA as an organisation that supports, provides information and lobbies for artists and arts organisations in Africa. This conference was followed by a series of masterclasses that assembled a medley of artists, curators, writers and researchers from the continent to brainstorm and implement interventions, projects and infrastructure that created more opportunities and new possibilities in the visual arts sector of the continent.

From 2007 to 2009 the organisation received its first round of national funding from the National Arts Council of South Africa. This funding helped with capacity building, developing regional structures in Gauteng (main office), Western Cape and KwaZulu Natal. The organisation launched various programs and capacity building.

From 2010 to 2013 the organisation’s online services were launched such as ArtMap (a mapping service that shows the different art institutions that are active in the country), as well as the information/ opportunities portal that provides members with access to new opportunities and funding. The regional offices were closed down during this period, making way for one main office in Johannesburg that committed to decentralising its members through network building, access to information from anywhere in the country and the creative development of infrastructure across the African continent.

33

34

VANSA was born out of the need to amplify the voice of what was considered to be ‘alternative’ at the time and to deepen the channels of access and information for emerging black artists.

IMAGES: Growth, Transformation and Opportunity conference, Cape Town, 2006

35

The Role of VANSA over the past 15 years

The work of VANSA over the last two decades has been a direct response to the needs of artists and art professionals in South Africa and the continent at large. A space that is widely accessible to both self-taught and formally trained artists that provides information, resources and support. The foundation of the organisation is highly research and data driven because in order to provide access and information; relevant and in depth research must be conducted to locate gaps, challenges and opportunities in the sector.

Creating Networks

From its initial stages, it was paramount for the organisation to not only amplify the voices of new, emerging, and established artists, it was also essential that they play a role in developing a strong network between different organisations and artists across the continent. The historical landscape of our continent has been shaped by the disparity enforced by colonial governments who introduced borders that emphasised the geographical and social differences between our communities. Even after each nation state gained its ‘independence’ little effort has been made to establish ties between the various nations. The linguistic and institutional differences between Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone governments has also deepened the distance ‘postindependence.’

Since its inception, VANSA has made efforts to create resilient ties between different arts organisations across the African continent. Collaborations with organisations and institutions such as Centre d’Art WAZA (Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo), thirdspace (Maputo, Mozambique, Yebo Contemporary Art Gallery (Ezulwini, Eswatini), Centre Soleil d’Afrique (Mali), Alle School of Fine Arts & Design (Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia), E.studio Luanda (Luanda, Angola) and many more.

36

Since its inception, VANSA has made efforts to create resilient ties between different arts organisations across the African continent.

Professional Support

In conversations with people who are active in the visual arts sector, one of the main structures that is associated with VANSA is the opportunities portal where artists and art professionals can view information on new projects, funding and employment. This is an incredible resource that has equipped artists and organisations with information, knowledge and access.

In addition to the online information portal, the organisation has played a significant role in developing norms, guides and standards for the visual arts community across the continent. VANSA has lobbied for the rights of artists in South Africa through their work with the government, and as a result has increased state investment in the visual arts. Projects such as the Arts, Culture and Heritage White Paper of 2016, advocating for artist resale rights and lobbying for the state to improve national museums and galleries have enhanced the overall experience of artists and arts organisations in South Africa.

Through its research-driven approach, VANSA has been able to create several guides and toolkits for artists and arts organisations to implement in their communities as a means of supporting themselves. Guides such as 2010 Reasons to Live in A Small Town, The Internship Toolkit and The Best Practice Guide for Visual Arts in South Africa have made it more accessible for artists and organisations to learn and implement professional support in their communities across the continent.

Part of the professional support

VANSA has provided over the years is to collaborate with already established organisations as a means of fortifying the impact they have on their communities. Working with organisations such as the Klerksdorp Art Gallery and Art Aid in Mbombela, has assisted in supporting these spaces as they empower their own communities.

Membership: The Core of VANSA’s Archive

The membership of VANSA is made up of artists, arts organisations and institutions, art enthusiasts and cultural workers that span across diverse disciplines. The membership of the organisation has grown to welcome continental and international visual art organisations to be a part of the conversation.

Members are able to access information about opportunities and be a part of the greater network of the visual arts. The organisation has been able to create a unique approach to decentralisation in the visual arts through their online presence. Anyone is able to join the community from anywhere in the world. Whether you live in the urban landscape of Accra, Ghana or the farmlands of Karoo, South Africa; you have access to networks, opportunities and resources that can help build and grow your practice.

There are three membership tiers, each with its own level of access. One can access the membership structures here: Membership

37

VANSA has been able to create a unique approach to decentralisation in the visual arts through their online presence.

15 Over 15: Programmes That Have Shaped The Ecosystem

VANSA has been in existence for more than two decades. The task of this project is to bring to the forefront, document and articulate 15 years of the archive. The organisation’s contributions to the arts sector on the continent can hardly be measured or quantified, there may be programmes and projects that have gone undocumented, only known by those who are part of them. This list of 15 programmes is far from fully exposing the impact VANSA has made. This is simply a selection of projects that have shaped and shifted the progression of the visual arts in Africa over the past 15 years.

1. 2010 Reasons to Live in a Small Town

Twenty Thousand and Ten Reasons to Live in a Small Town was a question that took the form of an interactive community based programme across various towns in South Africa. The question; what roles can contemporary art practices play in the context of small towns and rural communities in South Africa?

The programme was designed as a response to the call for proposals issued by the National Lotteries Board ™ for projects that focused on public art in 2010. VANSA responded to this call by asking how creative interventions in public space engage with the fabric of local communities in ways that nurture new possibilities. The need for this new narrative was prompted by how small towns and rural communities were/ are often represented as archaic, marginal and lacking places that people need to

leave to be exposed to new possibilities. This programme dealt with how the rural simultaneously composes authenticity and origin, in essence; what is it that we can learn from what is considered to be ‘the small.’

With these questions in mind VANSA commissioned individual projects that activated local resources, agencies, businesses, educational institutions, civic organisations and individuals from conception to completion. As a result 15 temporary artworks, 26 permanent and semi-permanent artworks and installations were developed over the duration of the programme. Projects were rolled out in all nine provinces in the country. Some examples of spaces that were activated are in Dundee (KwaZulu Natal), Hermon (Western Cape), Musina (Limpopo), Phakamisa (Eastern Cape) and Sutherland (Northern Cape).

The outcome of this programme was documented as a publication titled 2010 Reasons to Live in a Small Town in conjunction with an exhibition about the project at GotheonMain, Johannesburg in May 2011.

2. Arts Collaboratory

From its inception VANSA has been concerned with ways in which a sustainable ecosystem among art practitioners on the continent can be configured. The Arts Collaboratory programme was birthed out of the need to facilitate and nurture crosscontinental and global south connections between arts communities. The ongoing outcome is a network of 25 diverse organisations all over the world that focus on art practices, processes that deal with social change and working with broader communities.

The intention for this programme as stated by VANSA’s previous director, Joseph Gaylard in his strategic plan for the organisation in 2013 was to achieve, “Long term support for independent visual organisations focusing on collaborative art practices and social innovation”

38

IMAGE: PAN!C Map, 2015

3. PAN!C

The Pan African Network for Independent Contemporary Artists was established in collaboration with Centre d’Art WAZA (Lubambashi, DRC) in 2012. The programme was formed as a channel of mapping independent contemporary art initiatives across the continent. PAN!C was launched as an online site where visual art practitioners throughout the continent are invited to contribute their projects and spaces. This platform was created to empower broader knowledge, networks, connections, resources and materials sharing across artists and art organisations.

Part of the PAN!C programme is the PAN!C Library which was designed as a content and discourse sharing platform where materials and resources can be exchanged with organisations across the continent. This emerged from the difficulty in knowledge and resource sharing across the continent, as well as the deceptive narrative that Africa does not produce its own knowledge. While navigating this online library, you can expect to find materials and references that deal with matters concerning art on the continent. These materials are available electronically and physically.

An additional part of this programme is the PAN!C Curated Projects space that

IMAGE: Map Index

functions as an archival space for projects that have shaped and influenced the visual arts across, and in some cases, about Africa. This archive was created with the same intention of addressing the challenging communication and knowledge sharing channels on the continent. This space also functions as a platform for reflection on how contemporary art operates in the broader African context.

The final part of this online platform is the PAN!C Research Maps which was designed as a way of rethinking geographies of African contemporary art beyond the borders enforced during colonial rule. The research maps are designed to spatialise connections and shared ideas through communications across the continent. Each map highlights programmes, residencies and organisations operating in different parts of the continent.

To achieve this platform, VANSA in collaboration with Centre d’Art WAZA partnered with seven Arts Collaboratory organisations namely; 32° East Ugandan Art Trust, Centre Soleil d’Afrique, Nubuke Foundation, Darb, Doual’art, and Ker Thiossane.

Link: PAN!C

39

CHOOSE YOUR DESTINATION DO ARTISTS GO ON HOLIDAY? What artists should consider when planning to travel on the continent and applying for residencies. PAN!C | MAP | 2015 CHECK IN TIMES BOARDING GATES BAGGAGE COLLECTION (EXPECTATIONS/OUTCOMES) OTHER: UNDER CONSTRUCTION: AIR AFRICA / artists in residency ARTIST HOME >> AFRICA GUEST >> ARTIST PRACTITIONER RES EARCHER BOARDING PASS RESEARCH DONE ON >> 22 SPACES +2 (0) 23610511 darb1718.com Townhouse Artist in Residence Program +2 (0) 23610511 thetownhousegallery.com Aria (artist residency in Algiers) arialgiers@gmail.com First Floor Gallery Harare firstfloorgalleryharare.com Kitengela Glass Kenyav nani@kitengelaglass.co.ke kitengelaglass.co.ke L Zambia munandiartstudiosv@yahoo.com kalinosicmutale@yahoo.com L South Africa E info@thupelo.com Njelele Art Station Zimbabawe njeleleart@gmail.com njelele.tumblr.com Nafasi Art Space Tanzania info@nafasiartspace.org nafasiartspace.org L Kenya info@kuonatrust.org kuonatrust.org Uganda info@ugandanartstrust.org info@bagfactoryart.org.za Nabdh Residency (B’chira Art Center) bchirartcenter.com panicplatform.net CHOOSE YOUR DESTINATION PAN!C | MAP | 2015 floatingreverie.co.za 13 L Angola E info@e-studioluanda.com Visual Arts Network of South Africa info@vansa.co.za 18 Centre Soleil d’Afrique soleil@afribone.net.ml 19 nubukefoundation.org 20 PLATFORMS AND SPACES THAT ARE IN THE DEVELOPING THEIR ARTIST IN RESIDENCY Sober & Lonely Suburban Residencies 16 Thapong Visual Arts Centre thapongartscentre.org.bw 17 Raw Residency Senegal (221) 33 864 02 48 info@rawmaterialcompany.org rawmaterialcompany.org Picha Art Centre Democratic Republic of Congo (243) 814 53 19 65 recontrespicha@gmail.com rencontrespicha.org Les Ateliers Sahm Democratic Republic of Congo +242 04 499 94 52 info@atelierssahm.org atelierssahm.org

4. Boda Boda Lounge

An adaptation of the word ‘border,’ Boda Boda Lounge was designed to be a project that traces physical mobility and movement across marks that represent the divide of space and land. Those that come across this programme can expect to be transported across the continent by way of video and multimedia art works.

Initiated by VANSA in collaboration with Centre d’art WAZA, Boda Boda Lounge uses artistic practices to respond to and reflect upon cross-border travel and the politics involved in the various contexts of space and nationality. As part of the project, a publication was released titled ‘From Space (Scope) to Place (Position),’ which takes its readers on a journey formed through essays written by various art practitioners on the realities and challenges facing video art practice on the continent.

The project along with the publication includes contributions made by a number of artists from countries including; Ethiopia, Cameroon, Mozambique,

Tanzania, The Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and many more. This was achieved through partnerships with organisations in VANSA and Centre d’art WAZA’s network. Organisations such as Chimurenga (online), Pincha (Lubambashi), Voices in Colour (Bulawayo), Njelele (Harare), Medina (Bamako), 32° East Ugandan Art Trust (Kampala), Alle School of Fine Arts and Design (Addis Ababa), Townhouse (Cairo), Centre Soleil d’Afrique (Bamako), VAN Lagos (Lagos) and Kin Art Studios (Kinshasa).

40

IMAGE: Boda Boda Lounge, Soft Pow(ers), 2018

5. Take Care

The obstacles facing young black art practitioners in terms of mental and holistic health have been prevalent for decades. Many use their art practice as a form of release, however the need for a space that directly addresses the mental health challenges faced by artists and the effects of these issues in the organisational culture of many art programmes, has often been neglected. In response to these obstacles, VANSA launched the Take Care programme which was designed to bring forth “dialogue, awareness and understanding,” about health and wellness to the visual arts space on the continent.

According to VANSA’s research, creative industries are three times more likely to face challenges regarding mental health. The demands that accompany working in the contemporary art industry are unique and as such must be dealt with care. VANSA recognised the need to normalise asking for help as an art practitioner, and acknowledging the responsibility to promote individual and collective care across creative industries. The organisation launched the Take Care website to propose a multi-faceted way of engaging with mental health in the arts.

‘Take Care: A Mental Health Toolkit,’ was published in 2021 as a guide for art practitioners on how to further understand mental health in the visual arts. It provides suggestions on how to handle mental health challenges while working as well as dealing with the demands of the visual arts space. The toolkit also shares information on resources one could use and who can be contacted when in need of help.

Part of this project also included two podcast series titled, ‘Take Care with Maia Marie’ and ‘Minding Our Business with Rera Letsema.’ The former is a space where artists share how they practise wellness in their daily lives and how their creative practice connects with health and wellness. Maia Marie shared conversation with artists such as Gabrielle Goliath, Loyiso Oldjohn

and Akudzwe Chiwa. The second podcast, ‘Minding Our Business,’ was facilitated and produced in collaboration with Rera Letsema, a collaborative creative research space founded by Tšhegofatšo Mabaso and Tatenda Magaisa. This is a six-part podcast where each episode dives into questions of sustainability in creative industries and art as a practice of healing.

In addition to the toolkit and two podcast series, VANSA identified that there was a general lack of knowledge and understanding on matters pertaining to mental health in the visual arts. During this process, the team reached out to Professor Rita Thom and Dr Alicia Swart at the University of Witwatersrand to design a survey that would be open to the public between July and September of 2021. The findings of this survey can be found on the Take Care website.

To complement all the elements of the Take Care programme VANSA developed and facilitated a collection of workshops that were designed to mainstream some of the knowledge revealed throughout the project. These workshops were targeted at organisations and individuals working in the contemporary visual art space. The main focus of these workshops was to mainstream collective care and disassemble adverse and harmful working conditions for creatives.

41

Creative industries are three times more likely to face challenges regarding mental health.

IMAGES: Mental health workshops, 2019

42

43

6. ArtMap South Africa

If the question is; where could one get information about a number of the contemporary art institutions and infrastructure that spans across South Africa? ArtMap is the answer. ArtMap is a geopositioning website that helps artists, curators, researchers and anyone interested from other countries on the continent with a first point of entry into locating some of the contemporary art institutions in the country.

At a single glance, one is able to have an overview of a wide cross section of institutions that run contemporary art programmes across the country. The website geolocates museums, galleries, alternative art spaces, tertiary institutions, development organisations and events across South Africa. This platform can be used by art practitioners from countries on the continent as a basis for creative collaborations with South African organisations, networking and research.

7. ARTRIGHT

ARTRIGHT is a space on VANSA’s website that shares free resources for business, legal and educational guidance in the contemporary arts. The page was

developed to help ensure that people working in and around the visual arts contribute to better and more ethical business practices, on a more regular basis. Often what we find in the creative industries is business conduct that either exploits creatives, or lacks transparency. This programme provides toolkits for art practitioners on governance, organising, collaborations, better business practices, internships and so forth. In conjunction with this webpage, VANSA has hosted a number of professional development workshops over the past 15 years.

8. Best Practice Guide for The Visual Arts

As part of the ARTRIGHT programme, VANSA published a Best Practice Guide for The Visual Arts in 2016. This toolkit emerged out of the need to disseminate and provide access to industry practices that promote healthy and ethical relationships as well as transactions between people working in and around the visual arts.

A major gap has developed between fair standards for collaboration between art practitioners and the current terms of practice in South African visual art industries. This guide shares basic principles that collaborators can make use of when establishing partnerships and relationships. One element of

44

IMAGE: ArtMap

IMAGE: Map Index

collaboration that is not often addressed is the difficulty in navigating relationships that may result in an imbalance in power dynamics between those involved. The Best Practice Guide shares ways in which these circumstances can be navigated to ensure a fruitful and mutually beneficial collaboration. Some of the recommendations include how to manage events, residencies, public commissions, workshops, awards and competitions, publications and so forth. In 2012 VANSA facilitated the first skills development and professional practice workshop. Since then, the organisation has successfully facilitated a number of best practice workshops across the country.

9. Internship Programme + Toolkit

For a number of years, VANSA in partnership with Africalia, a Belgian organisation that supports contemporary art in Africa, ran an internship programme for arts organisations in South Africa. The focus of the programme was to support organisations to successfully host individuals as they work to grow their professional experience and contribute to organisations through internships.

In 2014 VANSA conducted research and compiled a report to determine some of the ongoing challenges facing internships in arts organisations in the country. Subsequent to the report, VANSA in partnership with Africalia designed and published an Internship Toolkit which can be found on the ARTRIGHT page of VANSA’s website. The contents of this toolkit was derived from case studies that outline experiences and lessons of arts organisations as well as interns with varying contexts and needs. The toolkit unpacks themes and topics such as, among others; types of internships, unpaid compared to paid internships, mentorship, resources organisations will need to host interns, and some of the work interns can be expected to do on a daily/weekly/monthly basis.

10. Legal Help Desk

A common thread between many young artists in South Africa from varied backgrounds is the lack of access and exposure to legal advice when dealing with organisations and institutions in the contemporary arts sector. In 2017 VANSA formed a Legal Help Desk in partnership with the creative legal agency, Legalese to provide legal guidance for its members at no cost. This was a space where art practitioners were invited to email their questions and concerns and receive advice on the matter. The virtual help desk dealt with visual arts based queries such as contracts, copyrights, licensing, Intellectual Property and Resale Rights, marketing, ownership of work, professional disputes, free speech and censorship.

11. Revolution Room

Between 2013 and 2016 VANSA in collaboration with Centre d’art WAZA were interested in reflecting on some of the artistic and new museum practices within communities in South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The two organisations identified four sites, three of which are in the DRC and one in South Africa, that would form as case studies for this inquiry.

At each site Revolution Room considered the social and spatial dynamics that exist within the communities’, and how these dynamics reflect on the communities modes of expression, connection to memory as well as the visible social tensions. The purpose of this project was to understand how these intricacies can and often do manifest in the expression of public space through artistic practice.

The reflections resulted in 9 projects that were produced over the period of 2014 to 2015 with a collection of materials used for exhibitions and public presentations.

45

Humusha

Humusha is an isiZulu word that can be translated to mean ‘interpret or translate.’ This programme was inspired by the disparity between the creative industries and science. VANSA wanted to fill this gap by nurturing a relationship between the visual arts as a tool to innovatively communicate scientific phenomena.

The outcome of this inquiry on how collaborations can be fostered between artists and scientists came in the form of a web platform. This is a digital space for scientific researchers to find and commission visual and creative artists to communicate their research findings to the public. The web platform is also a space where freelance creatives can access more opportunities for noncommercial and well-paid work. Artists are commissioned to create images, infographics, videos, animations or any other creative communications for scientists to share their research with the public. Scientists browse a list of creatives and select an artist/s who can communicate their project effectively, learn more about how creatives work and how to remunerate them appropriately.

13. Re-presenting the Archive

I n 2021, Magnum Photos in collaboration with VANSA developed the project ‘Re-presenting The Archive,’ as a response to the left out and sometimes

46

12.

This programme seeks to create new photo edits that bring forward alternative perspectives on what may have previously been misrepresented or buried.

IMAGE: Humusha

IMAGE: Representing The Archive

suppressed photographs that represent African histories. Western epistemes have represented the archive through a specific lens, this programme seeks to create new photo edits that bring forward alternative perspectives on what may have previously been misrepresented or buried.

The outcome of this collaborative project is a fellowship programme that invited four photographers in South Africa to create original photographic work that explores contemporary perspectives through a historical lens. The four fellows were also mentored through online sessions and workshops to create a printed zine or DIY exhibition where their work can be distributed across networks in South Africa and the UK.

Magnum Photos is an international agency that represents some of the world’s most renowned photographers. Their approach to documenting the

world’s events is through artistry, storytelling and photographic

journalism.

14. HGGA with Goethe

The Henrike Grohs Art Award is a biennial art prize that is awarded by the GoetheInstitut and the Grohs Family. This prize was established and named after the former head of the Goethe-Institut in Abidjan. VANSA has been tasked with managing the administration of this programme which shortlists artists who are awarded by an international jury. The winners of this award receive a cash prize as well as a publication produced on their work. This prize is open to artists and collectives across the African continent and supports emerging artists in their careers. The inaugural prize was awarded to Em’kal Eyongakpa, a Cameroonian intermedia artist in 2018. Since then artists and collectives have been encouraged to apply for this award.

47

IMAGE: Em’kal Eyongakpa in his studio

15. CATHSSETA Bursary

In 2020/21 VANSA was appointed by the Culture, Arts, Tourism, Hospitality and Sport Sector Education and Training Authority to select, recruit, facilitate and manage a bursary programme that supports 4 artists to further their education and training in institutions of higher education. The aim of this bursary programme is to fund artists who are studying in fields relevant to areas of scarce and critical skills, providing them with an opportunity to expand on their practice. The 4 selected candidates for the 2020/21 bursary are; NoBuntu Mhlambi, Khulekani Cele, Mhlonishwa Chiliza, and Luvuyo Nyawose.

Policy Making & Advocacy

Part of the initial vision for VANSA when it began was to create and enable a policy environment for visual arts professionals, organisations and businesses. The organisation noticed how issues relating to the visual arts, and most creative industries, are left out of government policies and legislation.

A. Copyright Framework + Artist Resale Rights

The 2016 VANSA report writes;

Artist

Rights

The organisation noticed an imbalance in the industry where art dealers and sellers were making more money from reselling art pieces and the artists themselves not having access to the circulation of revenue made from art pieces created by them. As a response to this VANSA developed and lobbied for the South Africa government to include the Artist Resale Rights in the Intellectual Property Amendment Bill by the Department of Trade and Industry in 2009.

48

“VANSA began lobbying for

Resale

in 2009, and for a Norms and Standards for the Visual Arts in 2010, and this past year has brought about the successful realisation of both these major changes in the sector!”

B. ArtBankSA (Baseline Report 2010)

A national programme supported by the Department of Sport, Art and Culture (DSAC), ArtBank was launched in December 2017 after the call led by VANSA for government to invest more in the visual arts sector. This programme came out of the Baseline Report submitted by VANSA to develop norms and standards of investment of art made by black and emerging artists by government.

The result was a programme hosted by the National Museum Bloemfontein, that purchases art pieces from emerging artists and leases and sells these works to government departments, private individuals and companies.

Access to the website and catalogue can be found here: ArtBankSA

C. Arts, Culture and Heritage White Paper of 2016

VANSA in partnership with Arterial Network SA lobbied for government to include the visual arts in the policy framework for arts and culture in South Africa. The section of the policy that outlines the government’s intentions for supporting the visual arts was in fact written by VANSA. In this paper, the government has committed to; fixing national art galleries and supporting artists to access revenue for pieces sold on secondary markets such as auctions.

VANSA has and continues to make significant progress in the inclusion and representation of the visual arts in the investments and implementations made by the state to improve the overall experience of cultural and creative professionals.

49

6. Creating our own archives

Throughout this publication, we have waxed and waned through the resources, limitations and prospects of the archive as it interacts with people working in creative sectors. As mentioned in the beginning, the intention here is not to provide the reader with a single way of engaging with archiving, but to bring forward different perspectives to help expand on the possibilities of the archive. This final section shares a few things one may want to consider when building their own archive. Whether it be for your creative practice or personal interests, the ways in which we can archive are infinite.

Practical Things To Consider:

Space:

Where will the archive live? This is an important question to ask when considering creating and maintaining an archive. The arts sector is multidisciplinary and there are many ways that you can store your pieces, thoughts and ideas. Additionally, we live in both an analogue and digital world, and because of this the selection of spaces where we can store our work is vast. Place, environment and the body have also been highlighted as significant ways in which we can store our experiences. Inherited knowledge comes from the memory of the body and place. Memory lives even when we do not try to shape it. However there are also some ways that we can intentionally remember. Here are examples of where your archive can live are;

• Videos and short films

• Photographs

• Essays and writings

• Websites and social media

• Personal backup systems such as hard drives and online storage

• Voice recordings

There are various spaces where archives can be stored digitally;

• Hard Drives

• Online storage platforms (Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive etc.)

• Multiple devices such as old cell phones and PCs/laptops

• Memory cards

The Budget:

The resources we have access to directly inform how far we can go with developing our own archives. There are various ways in which we can document, record and store with or without access to large amounts of capital. The first thing to consider is, ‘what do I have access to?’ Do you have a computer, a smartphone, a notebook or even a piece of paper? On a basic level these are all ways that we can shape memory with less pressure regarding capital.

How far would you like to proceed with archiving? This question is important as it can assist in creating a plan for either raising or procuring funds to help support your archival process. Here are a few examples of ways one can seek external capital for a creative archive.

• External funding

• Grants,

• Residencies

• Fundraising

51

Ownership

Who does your archive belong to? The obvious answer would most likely be ‘the one who created it.’ However, when working with others, especially institutions such as galleries and museums, it is imperative that the ownership of work is made clear to every party and individual involved.

Another important element to consider regarding ownership is if something were to happen to you and you are no longer able to continue to contribute to your archive, who inherits it? Will it remain in your family? Will you donate it to a trust or an organisation? These questions regarding ownership are critical if you are interested in creating longevity with your archive.

Organising and Cataloging

There are multiple ways in which one can work on organising and cataloguing a creative archive. The best way to approach this is to consider how you understand and sort through information. Here are a couple of examples of how an archive can be organised;

• By Date: This could be organised from the most recent project to the earliest or vice versa.

• By Project Type: This is helpful for multidisciplinary artists/organisations, or those who work with different mediums. For example; grouping all photography projects together and all installation type projects in another folder.

• The Messy Way: Often we place a lot of emphasis on order, however there is great value in embracing the messiness and disorder of an archive. This particular method is helpful when one is still in the process of a specific project, where the importance is more on retrieving things without the pressure of understanding why and how they will be labelled. There is great value in trusting the process and allowing the outcome to reveal itself to you when it is time.

Organisations to Look Out For

The South African History Archive (SAHA)

Founded by anti-apartheid activists in the 1980s, SAHA is an independent archive that documents, supports and promotes awareness on human rights and struggles for justice in both past and contemporary South Africa. They have access to resources and publications that relate to archival practices as well as networks that can connect different professionals who are working with and through the archive.

Decolonizing The Archive (DTA)

DTA is a Pan-African collective that is dedicated to both disrupting the colonial archive and changing the narrative shared about African and indigenous communities across the world. Their approach to working with the archive is multi-disciplinary, with creative projects ranging from photography, audio recordings, short films, podcasts etc.

Chimurenga

An online platform that nurtures PanAfrican ideas on art, writing and politics. Chimurenga seeks to re-imagine the space in which libraries and archives exist and opens up the possibilities for knowledge production, expression of ideas and creativity.

52

7. Conclusion

Shaping memory considers process to be as crucial as the overall outcome. Each step of the journey is as important as the end. Within the archive lies the possibility to recalibrate, recreate and reimagine the ways we record our experiences. The task is to immersively challenge and disrupt the archive, while recreating paradigms of remembering that resonate with our ancestral and collective selves.

The archive is a space that allows us to trace our becoming by unearthing how we came to be where we are, and how we can imagine the future. The process of creating our own living and embodied archives is an important part of telling our own stories through our own lens. This in many ways speaks to disrupting the archive as an established and colonial way of understanding memory and transcend the confines of what an archive is ‘supposed to look like.’ With this approach in mind, we can then move away from archives exclusively living in spaces such as museums and galleries and create archival paradigms that reflect the progression of our communities.

Since its inception VANSA has challenged the norms of the visual arts sector in Africa. Having been established as a response to the lack of visibility and access for emerging African artists and cultural workers in the visual arts, the organisation has managed to create an ecosystem of professionals who are both self-taught and formally trained. The impact that VANSA has made in the creative sector can be seen by the success of its members. The organisation has managed to develop and run programmes in collaboration with other African and international organisations, influence national policy making and provide professional support to emerging African artists and arts organisations.

55

The archive is a space that allows us to trace our becoming by unearthing how we came to be where we are, and how we can imagine the future.

8. Acknowledgments and Contributors

This publication was made possible through the support of The British Council and Southern African Arts. We would also like to share our appreciation to our collaborators, RADAR for helping us bring this programme to light.

The contents of this publication comes from the contribution of many generous people in the VANSA network. We would like to give special thanks to the current and previous VANSA directors who shared their experience with the organisation and contributed to the archive; Nomalanga Nkosi, Refilwe Nkomo, Molemo Moiloa and Joseph Gaylard. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Libita Sibungu who was commissioned by RADAR to co-facilitate the Shaping Memory Talk Series. This project would have not been made possible without the VANSA Projects Officer, Tokologo Mphaki and RADAR Producer, Laura Purseglove who produced and organised the talk series. The guests of the talk series; Memory Biwa, Lebohang Kganye, Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja and Tšhegofatšo Mabaso who helped us rethink and reimagine the archive.

Design: Lara Koseff

Photography:

Catarina Carvalho (pg: 14)

Dan Cristian Padure (pgs: 1, 6, 32, 50, 53)

Dan Farrell (pgs: 10, 13)

Pawel Janiak (pgs: 2, 23, 54)

Jazmin Quaynor (pgs: 24, 31)

56

9. References

Cook T (2001) Archival science and postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts. Arch Sci 1:3–24

Ketelaar E (2001) Tacit narratives: The Meanings of Archives. Arch Sci 1:131–141

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/13/61328/ innovative-forms-of-archives-part-oneexhibitions-events-books-museumsand-lia-perjovschi-s-contemporary-artarchive/

Weber, H and Weber, M, 2020. Colonialism, Genocide and International Relations: the Namibian–German case and struggles for restorative relations. European Journal of International Relations 2020, Vol. 26(S1) 91–115

Casper, E. (2014) Namibian History, from Namibian.org, [online], Available at: www. namibian.org

Wallis, F. (2000). Nuusdagboek: feite en fratse oor 1000 jaar, Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau.|Encyclopedia Britannica

Online (2009), ‘South West Africa People’s Organization’, available at: britannica.com [accessed 14 April 2009] |SWAPO [online], available at: wikipedia.org [accessed 14 April 2009]|Angola and South West Africa: A Forgotten War (1975-89)”“ article published by geocities.com

South African History Archive: https:// www.saha.org.za/index.htm

Decolonising The Archive: https://www. decolonisingthearchive.com

Video: Namibians Want Reparations From Germany For A Genocide That Killed Thousands (HBO)

Shaping Memory Talks co facilitated by Mkutaji wa Njia and Libita Sibungu: Libita Sibungu and Memory Biwa (13 October 2022)

Lebohang Kganye (15 October 2022)

Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja (20 October 2022)

Tšhegofatšo Mabaso (22 October 2022)

57

IMAGE: November 2016 Protest led by The Economic Freedom Fighters in Pretoria for Free Education. Photo by Pawel Janiak, 27 January 2017

IMAGE: November 2016 Protest led by The Economic Freedom Fighters in Pretoria for Free Education. Photo by Pawel Janiak, 27 January 2017