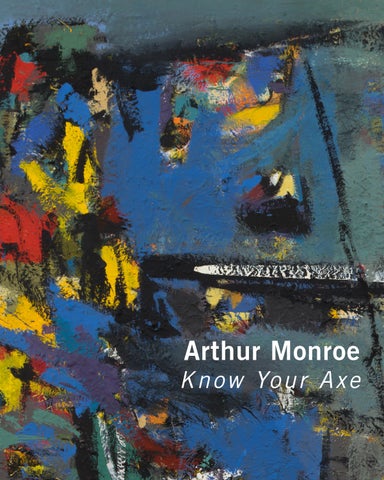

Arthur

Monroe Know Your Axe

Arthur

By Seph Rodney

One of the first things I notice in Arthur Monroe’s paintings are the rhythms at play in his brushwork. It’s likely that I’m influenced by the stories I’ve read of Monroe’s relationship to musicians and poets of the mid-century avant-garde in New York City. They are names of legend. In the 1950s Monroe developed friendships with the jazz musicians Charlie “Bird” Parker and Max Roach, and the poets Leroi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) and Ted Joans, as his son Alistair Monroe attests in an email about his experience of being around his father in the studio. They were “Sippin’ and dippin’ with Billie Holiday, Nina Simone and Alice Coltrane, then kickin’ with Parker, Monk and Roach, chillin’ to the Giant Steps of Coltrane and Charles Lloyd, just to name a few...the sounds were constant and deep rooted.” Arthur Monroe is also said to have counted as his colleagues certain painters of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, among them Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning. Later, in the 1960s, when he had settled in the Bay Area his companions were key members of the Beat Generation, including Bob Kaufman and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who produced the first exhibition of Monroe’s paintings at the famed City Lights bookstore.

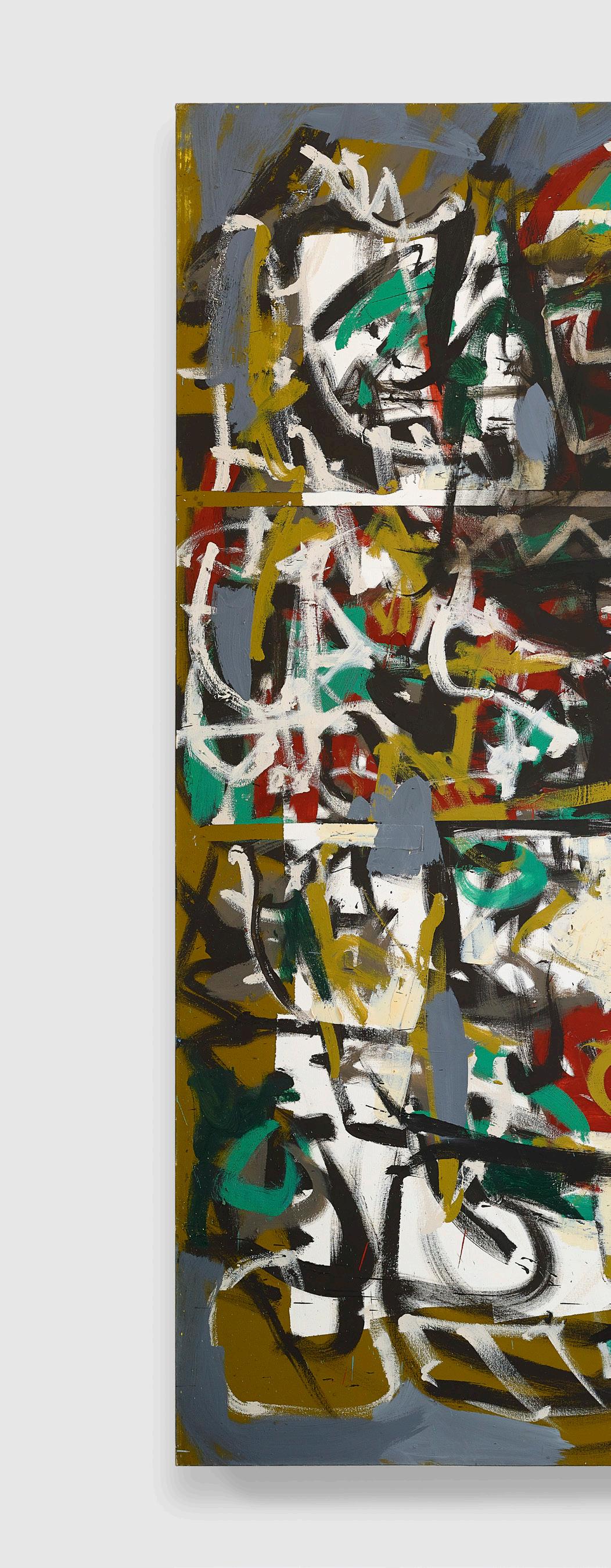

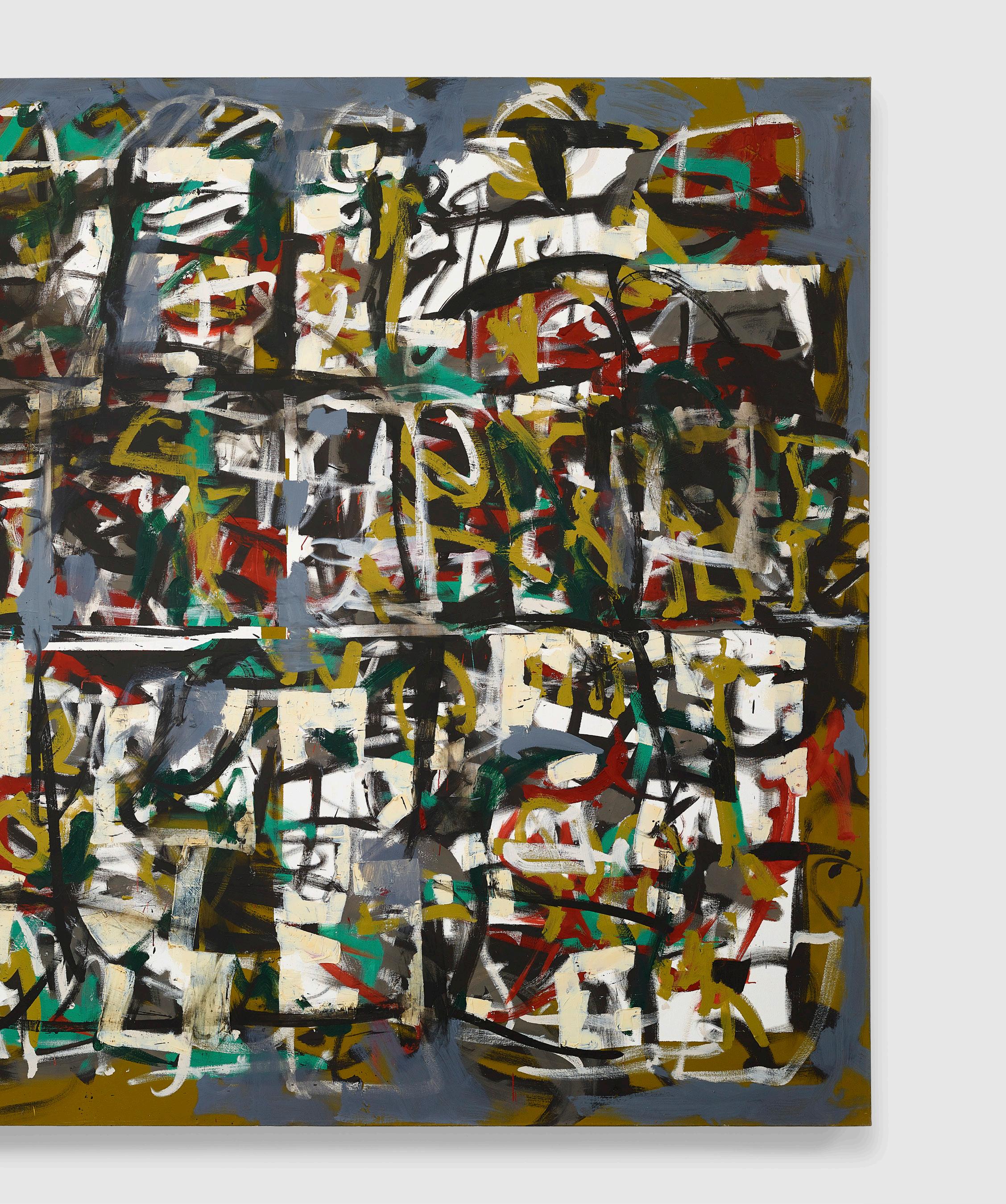

Looking at his 84-by-96-inch Untitled from 1983 (p. 14), I think of the tempo that undergirds it, the pulse and throb of the brushstrokes within small vignettes that contend with the overall organizing structure of each composition—all of which gives me a starting point for how to understand what I’m looking at. This painting’s fundamental structure is a grid.

This grid divides the horizontal ground into three sections, and the vertical is roughly split into six discrete spaces. Each of these small quadrants is delineated by Monroe’s use of white pigment, which has been applied in brief, slashing brushstrokes that create a tumult of movement in their combination with other truncated ribbons of gold, olive green, black, and red. The more or less equal division of space acts as a simple, repetitive drumbeat line to guide me through the painting. There are few, if any, other clues about how to traverse its complicated field. This canvas might depict a kindergarten, all of the children given crayons or colored pencils and a square in which to write themselves onto the evolving story of our world—and none thought it best to stay within their individual borders. The energy of the marks is intuitive, uninhibited, raucous, and searching, perhaps very much like the poets, the Abstract Expressionists, and the jazz musicians of the 1950s and ’60s who thought that mainstream United States culture needed to be reinvented and who earnestly, joyously put their shoulders to the wheel.

But Monroe didn’t articulate a set of political objectives that he intended to achieve with his painting, at least none that I have come across. Instead, he had questions that prompted some hard-earned conclusions, which led to more questions. He said, “If you are a painter, you have to start solving problems. What should a painting have?” 1 I look at his 1989 Untitled #1 (p. 18) to see how he assays an answer in this work.

Here, there is no grid. Instead, in this 96-by-84-inch canvas, there is a large form that dominates the left side, leaving a mostly barren taupe-colored field in the middle and some stray brown and green

1 Kit Robinson, “A Restless, Philosophical Quest: The Art of Arthur Monroe” (Open Space, SFMOMA), October 30, 2019

forms on the right. The dominant hue of the large form is blue, with nonuniform strokes of yellow, orange, and red making up a body, while a resolutely black line shapes the creature in such a way as to suggest an upright whale seen in profile, its tail tucked under and behind it. Here, the rhythm is more subtle: it is the ocean’s current, the lulling movement of the water toward shore. Something that resembles a fin is extended far in front as if reaching for something at the far side of the canvas. The forms on the right side might represent krill, or some other kind of sustenance, or just other life-forms that share its ecosystem.

What did this painting need to have before Monroe thought of it as finished? I know now Monroe imbued it with energy, purpose, a beating heart that guides it to somewhere it can be seen, where it might grab hold of you across the expanse of an invented ground. The painting should be reaching. It should have ambitions, aspirations, a sense that there is some standard that it might achieve, some gold it might publicly flourish on a podium, some sense of achievement.

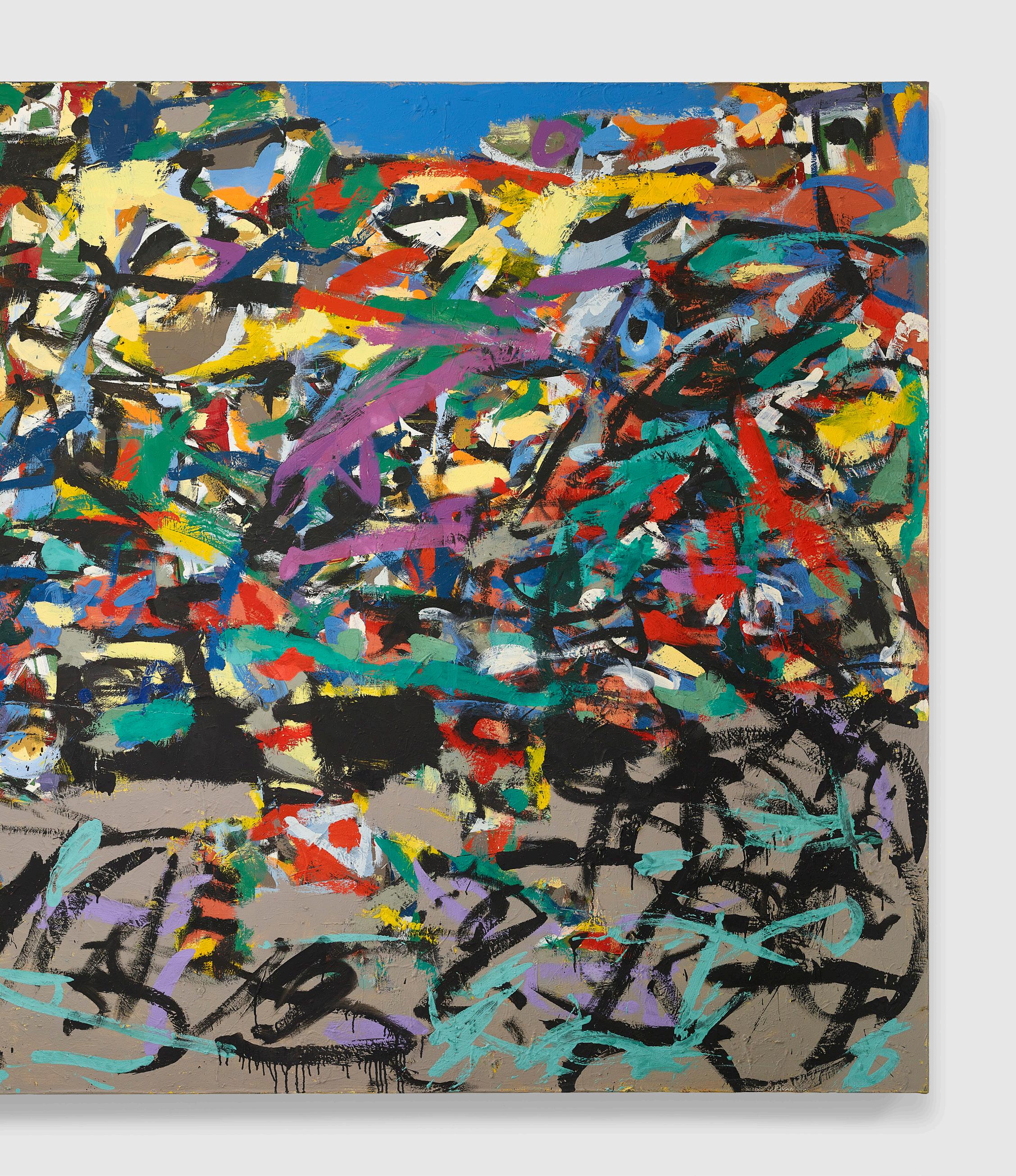

But Monroe’s question might have other answers. His Untitled (2003) (77 by 96 inches) (p. 28) doesn’t seem to have an underlying grid, nor does it flirt with narrative. It’s a shock of movement. From the left side of the canvas to the right there seems to be a hurried migration. Objects, feelings, and ideas flee one side, and slashing and hacking their way, the colors move eastward towards the rising sun. The painting can be read according to these directional markers because the top of the canvas has a ground that is a field of blue, hopeful, like the sky. While the bottom of the composition is that indifferent taupe I’ve encountered elsewhere in his work, the dirt ground beneath our feet. Closer to this bottom the marks become looser, limited to the colors of green and black, and stray marks of purple, as if the complex, kinetic world Monroe had invented was reduced to its most basic sociological signifiers for class (the purple of royalty), for wealth (the green of United States currency), and race (his identity as understood within this limited rubric).

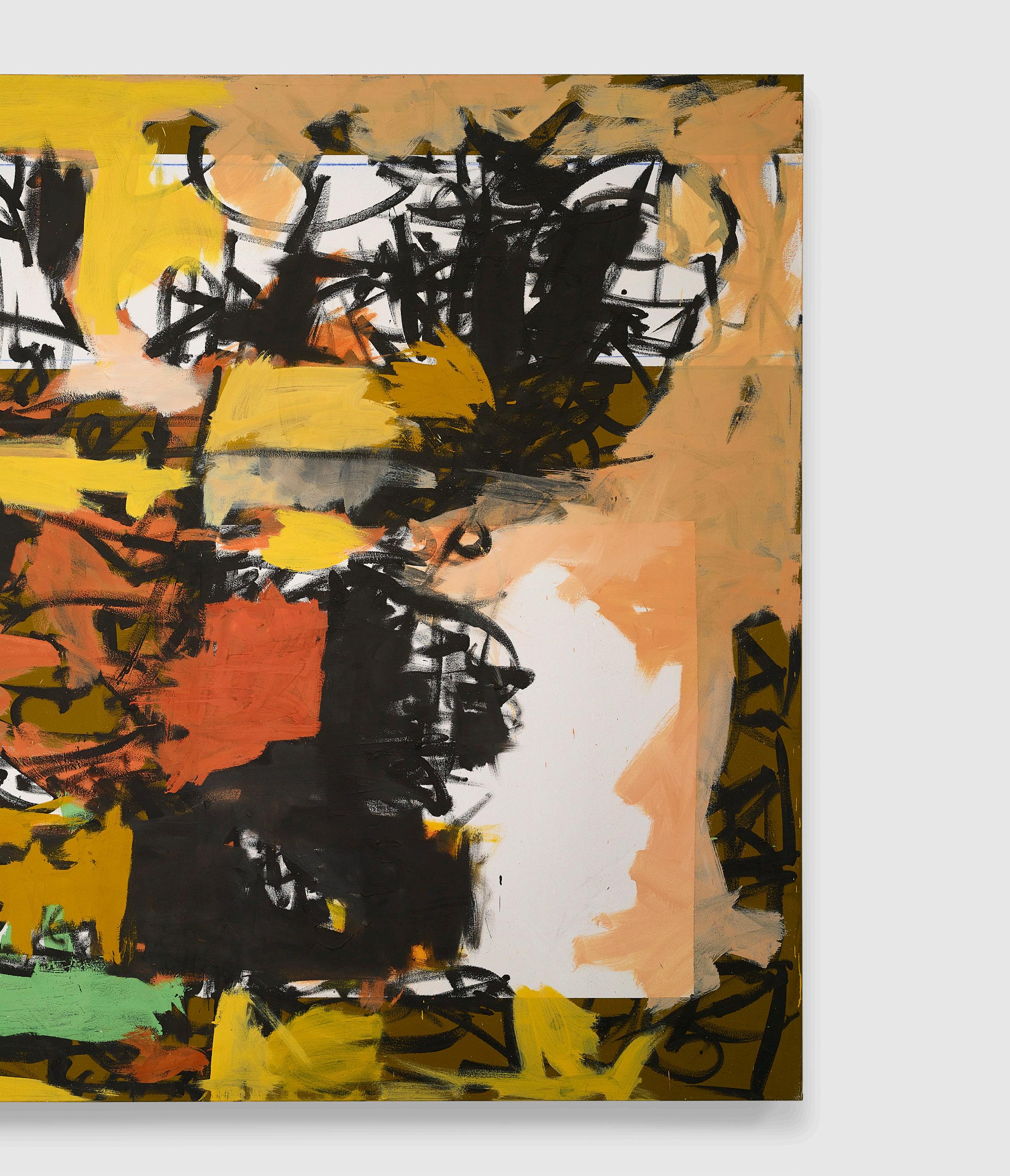

With other paintings the references feel less connected to lived life and more to jazz. Take Monroe’s other Untitled painting from 2003 (p. 24), measuring 84 by 96 inches and suffused with the primary color of gold so bright it feels like a precious stone. However, up close I find a myriad of other hues, a swirl and cacophony of mostly black calligraphic lines, differently shaped blobs of color, and brushstrokes that don’t cohere in any direction or design scheme. This canvas lacks a central motif or an underlying grid. What problems is it solving? Initially I struggle with recognizing what it’s doing.

A music memory comes to the rescue. I think of a contemporary of and collaborator with Parker and Roach: Charles Mingus, the American jazz bassist, composer, and band leader who lived from 1922 to 1979. Mingus was a major champion and enthusiast of collective improvisation, and this work feels like Monroe has taken that ambition to his own heart. Jazz often employs complicated harmonies, but there is a thing known as the tonic that functions as the central reference point in a tonally wide-ranging work. The tonic acts as the fundamental, or “home” note, of a scale or key. The improvisational Mingus frequently utilized this stratagem, and generated one album that long ago took up residence in my consciousness and won’t leave.

On Let My Children Hear Music, the track “Don’t Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too” features Mingus throwing every seemingly available thing into the mix: trombones, dogs barking, skittering drums, the roars of lions, trumpets blaring, tubas affirming the bass line, and the bellows of elephants. At certain points it feels so jumbled that I am lost. Is that dishes crashing in the kitchen sink? Listening to this track again as I write this, I intuit that Monroe had established the gold as the “tonic” of his painting and wanted to wander as far afield as he could get without forgetting where to return. The painting presents the problems of remembrance and recognition when one wanders here and there looking for a thing that is not actually in a place but residing in one’s body—that creative faculty some call a home. For him, after traveling extensively to Central America, West Africa, South America, and elsewhere, this was clearly of significance. It was only after settling in the Bay Area and painting for the next 30 years while employed as a registrar at the Oakland Museum of California that he was able to produce the body of work that now constitutes his primary legacy.

Some writers of Arthur Monroe’s story want to make him out to be a figure who marks both the evolution and marginalization of postwar Black Abstract Expressionism.2 He may be a sign of this historical development, but he’s also much more than that. He’s a bridge between the arts, the literary, visual, and musical, demonstrating that his particular creative work—paintings—aren’t a translation of some other art form; they are their own visual language, his own now and forever. It is a language animated by the need to move, to perambulate, to meander and roam, to provide a beat others can track. What should each painting have? It should have a bit of the image maker. Monroe succeeded in imbuing each painting with this. And each suggests a tempo wafting faintly in the distance that indicates how we might keep time with what we are seeing.

Following pages: detail

78 x 87 in (198.1 x 221 cm)

Following pages: detail

Following pages: detail

Following pages: detail

Following pages: detail

x 96 in (195.6 x 243.8 cm)

Following pages: detail

Arthur Monroe (b. 1935 – d. 2019) was an African American Abstract Expressionist who lived and worked in the Bay Area. Born in Brooklyn, NY, Monroe was educated at The Boy’s School in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn and the Brooklyn Museum Art School. Monroe trained further in painting at the Art Students League and under the tutelage of Hans Hofmann. Monroe spent his formative years in the East Village with painters including Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning, as well as Jazz musicians Charlie Parker and Nina Simone. Discerning the eurocentric aesthetic of the mainstream art world of New York, Monroe left New York for Mexico to examine non-European sources of visual art, especially those of the Mayans, Zapotecans, Michteans, and Olmecans. When he returned to America, he relocated first to Big Sur and then to San Francisco during the legendary Beat Era of North Beach in the late 1950s. Throughout his painting career, Monroe stayed committed to his Abstract Expressionist roots, creating rhythmic and striking, often large-scale works. In Oakland, California, where he spent more than 40 years of his life, Monroe converted the Oakland Cannery Warehouse into the first legal live-work space for artists in the city and advocated for the rights of artists to live and work as he did. He also cared for the historic collection at the Oakland Museum of California as their chief registrar and taught African American studies at the University of Berkeley, and San Jose State College.

During his lifetime, Monroe exhibited at prestigious institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY); the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA); the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN); the Oakland Museum (Oakland, CA); the Museum of the African Diaspora (San Francisco, CA,) to name a few. His artwork resides in the permanent collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (Washington, DC); Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, CA); Kristiania University College (Oslo, Norway); the University of Agder (Grimstad, Norway); and the de Saisset Museum (Santa Clara, CA). His collected papers from 1950 - 2019 were acquired by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in 2019, and he was the subject of a solo museum exhibition in 2024 at the Sonoma Valley Museum of Art.

It is a great honor to present the first solo exhibition of Arthur Monroe’s works since taking on representation of the estate. His dynamic paintings are ripe for rediscovery, and it seems only fitting that the show is taking place in New York, where his life as an artist began. We are tremendously grateful to Alistair Monroe of the Arthur Monroe Estate, who’s collaboration and passion have made this show possible. A thank you also to Seph Rodney for his insightful essay about Arthur Monroe.

Elizabeth Sadeghi

John Van Doren Dorsey Waxter

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

Arthur Monroe

Know Your Axe

September 17 – November 7, 2025

Design by Nick Naber

Edited by Elizabeth Sadeghi & Kieren Jeane

Artwork photography ©Estate of Arthur Monroe

Essay ©Seph Rodney

p. 2 & p. 34: Photos of Arthur Monroe by Kirk Crippens & Torre McQueen

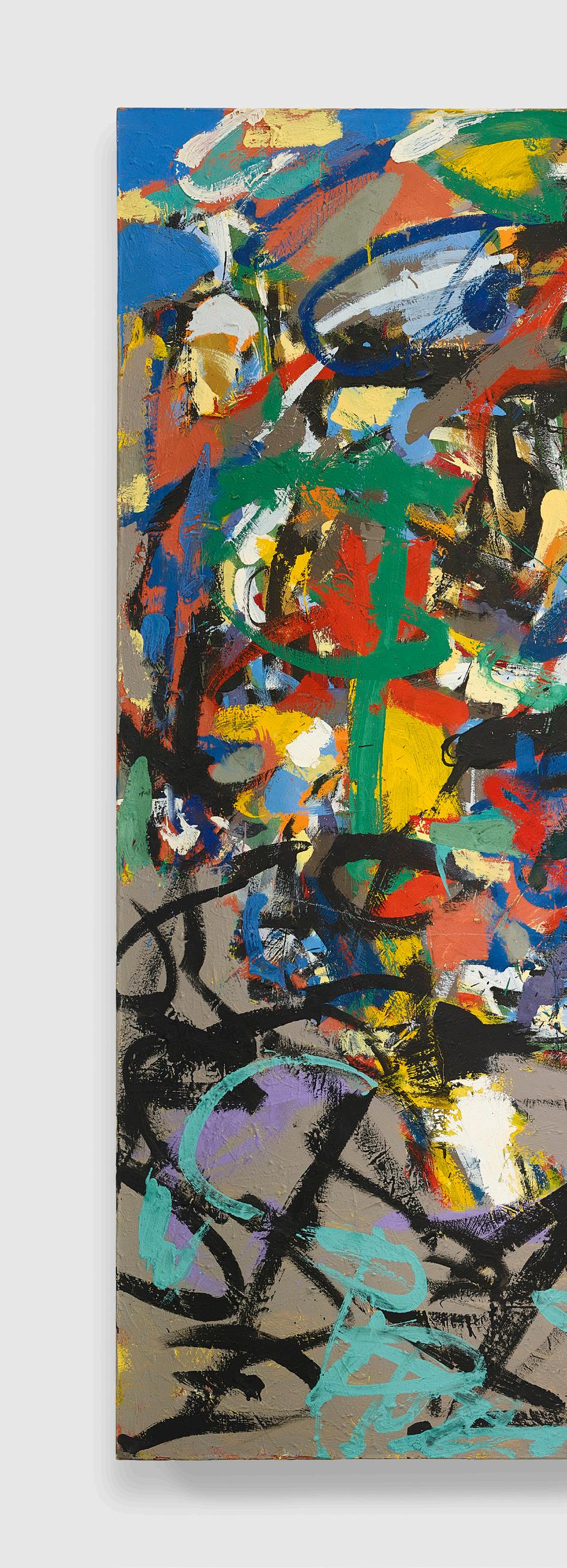

Cover/Inside cover: Detail of, Untitled #1, 1989, p. 18

Inside back cover: Detail of, Untitled, c. 1983, p. 14

Back cover: Detail of, Untitled, 2003, p. 24

VAN DOREN WAXTER

23 EAST 73RD ST

NEW YORK, NY 10021

Phone 212 445-0444 info@vandorenwaxter.com www.vandorenwaxter.com

© VAN DOREN WAXTER, New York, NY.

All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this catalogue may be reproduced without permission of the publisher.