ContEnts ContEnts

Open Letter

By SLACC Chairs Luna Fan and Ruaraidh Prentice

LexiCon - Una Fiesta de Idiomas

By Neo Haque

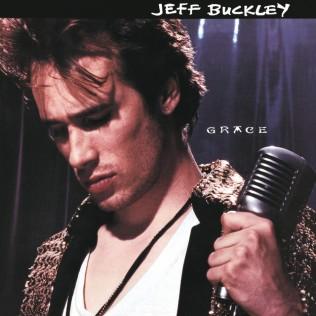

AC Music Review: Grace, Jeff Buckley ‘What matters in life’

By Sam Shovlin

Respect. Opportunity. Equality.

By Livia Felden

Sustainability as a Fiesta

By Feifei Liu

Yearning for Christmas

By Saanjhi Dubey

The Marginalized Side of Christmas

By Anonymous

“Born

in a Great Family” - Hidden Stories around the Campus

By Uxía Fernández Fernández

Color Fiesta - What the Colors Left Behind

By Giuliana Clementin

: A Winter fiesta

By Athena Rahman

Winter food: Celebrating the season

By By Hala Mughhrabi

The Room Hums

By Giuliana Clementin

“Fiesta” for Everyone?

By Facundo Almada Abreu

Human Library Speech

By Ziva Jacobson

Latino Christmas in Wales

By Sebas Orué

Open Letter Open Letter Fiesta Fiesta

Student Life Council Chair’s Letter Student Life Council Chair’s Letter

On most days, this school runs on order.

We move from class to class by timetables. We measure time in deadlines, weeks in assessments, worth in numbers. We introduce ourselves with nationalities, roles, grades, labels Everything has a category. Everything has a place until Friday night, when the lights dim for SOSH, the speakers turn on, and the room begins to move.

Anthropologists call this a ritual – a moment when ordinary life is suspended so that a community can remember what it is beneath structure We did not have that language when we first stood at the back of the sports hall: watching you all arrive in colors that did not belong to any uniform, carrying flags that we’ve only seen on Google, speaking languages that did not appear on our timetable.

But now we understand the meaning.

As the Student Life Council Chairs, we have stood at the threshold of many of our fiestas. We have watched national groups rehearse late into the night, and sometimes arguing gently over what part of home they were allowed to bring into this shared space. We have watched students step onto the AC Vision stage shaking, not because they were afraid of losing, but because they were afraid of representing something larger than themselves. We have watched fierce rivalry transform into quiet respect at the end of AC Olympics, where sweat

and exhaustion stripped competition back to humanity. We have watched AC Got Talent turn strangers into stories, to carry their House’s energy, laughter, and pride into the room.

And every time, we see the same transformation:

For a few hours, we are no longer solely students, competitors, leaders, followers, internationals, or locals. The usual architecture of identity loosens. Bodies begin to speak where language once stood in the way. Movement becomes a shared grammar. Music becomes a belief system that no one has to explain.

Philosophers might say this is where order meets its necessary chaos. The world is a system held together by schedules and standards, expectations and outcomes. Fiesta is the rare moment when we are collectively permitted to lose control without losing one another: a pressure valve, a fragile middle space where release is allowed. And I sometimes ask myself the question Nietzsche might have asked:

If we were never allowed to dance, how long before the world inside us would begin to break?

But to speak honestly of fiesta is also to speak of what is not always visible.

From the outside, celebration looks equal. Everyone is invited. Everyone is welcome. Yet power has a way of hiding inside even joy. Whose music fills the room most often? Whose culture becomes the rhythm everyone learns? Which dances feel “universal,” and which remain labeled as “exotic”? Which languages dominate the microphone, and which remain only in the crowd?

Sociologists tell us that even happiness is political. Even celebration carries structure. And yet, what continues to humble me is not that these tensions exist, but that in this community, we keep choosing to enter the room anyway. Again and again, we step into imperfect togetherness.

At fiesta, no one has to wear a mask, unless the dress code says so. No one has to perform or pretend. No one has to be anything other than exactly who they are. We all show up for the same reason: to dance, to laugh, to forget the time, and to party the night away without worrying about what comes next.

Life at AC is loud in its own way. Deadlines stack up faster than unread emails. Social life somehow becomes another responsibility. Sleep turns into a myth. And roommates… I think we can all agree on that one. There is always something demanding attention, something waiting to be fixed, finished, or figured out. But when it’s just you and the music, all of that quietens Stress loosens its grip Problems don’t vanish, but they step aside. They become tomorrow's problems.

That’s why a quote shared at last year’s Fiesta has stayed with me. “Life is not the amount of breaths you take. It’s the moments that take your breath away.” (Ana Sofia Reis e Sousa, 2025). In one sentence, it says everything we tend to forget Life isn’t about how busy we are or how well we’re coping. It’s about moments that stop us in our tracks, that make us feel fully present, fully alive.

Every fiesta that SLACC hosts is one of those moments - or at least we try to make it be. It reminds us that joy is not a distraction from real life. It is part of it. That choosing to dance, to celebrate, to be surrounded by people you love is not running away from responsibility; it’s remembering what all the pressure is for in the first place.

This issue of INK, “Fiesta!”, is an invitation. For one night, let the deadlines wait. Let the stress soften. Let tomorrow deal with itself. Be loud. Be ridiculous. Be exhausted in the best possible way. Let Fiesta be one of those moments that takes your breath away.

And remember SHE didn’t leave you on read, you just left her speechless.

Dear ACers,

The next time you walk into a room filled with unfamiliar music, unfamiliar skin, unfamiliar history, don’t rush straight to the center of the noise. Pause. Look around. Notice who is dancing freely. Notice who is searching for space. Notice who has never been invited forward before.

Because in a world that is still learning how to live together, a fiesta is never just a party.

It’s just the rehearsal.

Your SLACC Chairs, Luna and Ruaraidh

LexiCon - Una Fiesta de Idiomas LexiCon - Una Fiesta de Idiomas

After deciding back in Year 9 that I wanted to get good grades in French, (which paid off somewhat I think), I found myself lost in a rabbit hole of learning to optimise my language experience outside of school. Having watched countless videos and having read the abstracts of dozens of papers, I slowly became something of a linguistics enthusiast It made perfect sense that after starting at AC, my best friend from Day 1 would share this passion with me.

I know now that in hindsight, when Sebas approached me all those months ago, asking whether I wanted to organise a conference with him, my blind enthusiasm got a bit in the way of logic. Organising LexiCon was one of the most stressful things I’ve ever had to do for school. The last thing anyone wants to do while balancing 4 IAs, an EE, and early university applications is to organise a two day event for 400 people who don’t wanna be there. Looking back, I have no regrets about how things ended up, but I wish I had jumped into things with a bit more of an understanding into how much work it was going to be For all future generations of conference organisers, here’s what I learnt/what I think you should know:

1.From the beginning, we had a pretty clear vision of what we wanted the conference to look like. I know now that everything about the conference organisation process is iterative; if this doesn’t make you believe in “make the plan, execute the plan, expect the plan to go off the rails… throw away the plan,” nothing will. Having a solid foundation for your schedule, dream guest speakers, and decoration vision board, is all great, just don’t be gutted if (when!) your plans fall apart like a Nature Valley Granola Bar.

2.Don’t get bogged down in the details. When working with a team of 4-5 other smart, opinionated people, it’s easy to get caught up discussing one minor detail of the schedule or logo for an entire hour’s meeting. If you find your team starts to go in circles over something that can be easily resolved, don’t be afraid to call it out, take a breather, and talk about something else.

3.Listen to Claudia. Enough said, she knows what she’s doing.

4.Don’t be embarrassed to contact people. Whether it’s emailing Bruno Mars’ agent 5 times or making Marija send Adam Alecksic a LinkedIn request, you never know what’s going to happen. Before you know it you may be on a Google Meet with the world’s foremost expert in any given field.

5.Sometimes, trust>being right. If you’ve chosen to work on a team with someone for as big of a project as a conference, you need to be willing to trust them to make decisions on behalf of the team. Regardless of whether you think they’re making sense, sometimes you need to let go of the reins and see someone else's idea come to life

6.The above applies to you as well; if you’ve been chosen to do a conference, that means someone, somewhere, thinks you’re going to be able to pull it off. Extinguish your internal voice of selfdoubt and trust yourself like you would your teammates.

7.Get that extension. Hey, I don’t recommend putting off any of your IA’s till last minute, but when you get premonitions about breaking down on the floor of your dorm at 21:57 over ManageBac not working, don’t be ashamed to speak to your teacher and ask for an extra week to work.

8.Take Geography SL: If you have the ability to get a free code by any means possible, do so. While spending four hours formatting on Canva while everyone else is in codes is by no means anyone’s dream, you might just clutch the entire conference.

9.Speak to your guest speakers. I’d be lying if I didn’t tell you what a great networking opportunity being a conference organiser is. A couple of WhatsApp messages, a long email thread, brunch the morning of the conference, etc. all go a long way.

Throughout my time planning LexiCon, I was terrified that people would find it boring. I was definitely proven right in some regards, but I was also overwhelmingly touched by the number of people who genuinely enjoyed it and came up to me afterwards to tell me that. Ultimately, know that you’re not organising the conference for the people that will spend the entire two days hiding in bed or queuing for the health centre, but because you want to show the people who care something you’re passionate about, and that’s nothing to scoff at. Now, looking back months after the fact. I can confidently say that despite all the times I almost killed or got killed by my best friends, LexiCon could not have possibly been more worth it.

By Neo Haque

‘Jeff Buckley was a diva. And a particularly fanciful one at that.’ –Dominique Leone (2004). Buckley was not a grunger, a rockstar, or a folk mystic like his father Tim Buckley- he was something different entirely: a songbird, a mercurial vocalist whose four-octave range echoed the aching purity of petit moineau (little sparrow) Edith Piaf’s, and whose bluessoaked, orchestral, and sorrow-lit sound existed far outside the boundaries of 1990s alternative rock. In a year dominated by distortion and angst, Buckley arrived as a shimmering anomaly, a romantic torchbearer for a new emotional vocabulary that would go on to profoundly shape artists like Radiohead, Muse, Lana Del Ray and countless others. Grace was not simply another rock album from the nineties- it was a musical revolution, a singular force that still ripples across modern music. Tracks like Mojo Pin, Grace, Eternal Life (especially the much rawer sounding road version) and Forget Her, highlight the almost big band-ish, theatrical and rock side to Buckley’s music, while Last Goodbye, Dream Brother, So Real and Lover, You Should Have Come Over represent Buckley’s Edith Piaf-esque songbird roots However, undoubtedly, Buckley’s genre bending style can never, and will never be replicated ever again.

1994 was arguably one of the most influential and powerful years for music, especially for the alternative rock scene, with artists such as Weezer, Nine Inch Nails, Pearl Jam, Green Day and Stone Temple Pilots releasing their own ‘pièce de résistance’ works, however in my opinion, no album has left such a transcendent and haunting mark on the music industry as Grace. As it happened, Grace was received with mixed feelings from critics who probably thought they were getting the next great alt-rock savior, and instead felt they'd received dinner theater for the moody crowd They had a point: For all its swells of emotion and midnight dynamics, Grace was not a record to rally the post-grunge alternation. It made a jazz noise where a rock one was expected and a classical one where a pop one might have sold more records. Jeff Buckley’s stylistic choices completely caught the music industry off guard: in a year dominated by distortion heavy, power chord driven guitar lines and abrasive vocals, Buckley brought blues and soprano back to the mainstream. In an interview with MTV, Buckley described Grace to be ‘what matters in life’, a melancholic anthology of ‘love, morality and the passage of time’, and 31 years later, Buckley’s message still resonates with lovers, yearners and grungers to this day.

By Sam Shovlin

Growing up, my father always told me:

“Livia, when you get into a good college, study hard so you can go to an even better university. Get a PhD, and then work as hard as you can harder than everyone else”

But to my brother, he said something different: “Henry, when you grow up, just get into a good university that’s all you need for your future.”

For a long time, I didn’t understand why he said that. Later, I realized it wasn’t because he believed I was more capable, or that I needed more motivation

It was because he knew the world would not be as kind to me. Because he knew I would have to fight harder.

Why?

Because I am a woman.

And I know I’m not the only one who feels this way. There are around 4.15 billion women on Earth and many of them face the same challenges.

Why?

Because too often, men, companies, and even governments see women as less.

Today, my speech is about gender inequality. But first, let’s be clear about what that means

Gender discrimination is the unfair or unequal treatment of individuals based on their gender It includes any action or attitude that systematically disadvantages or marginalizes people because of their gender identity or sex affecting their rights, opportunities, and access to resources.

So let’s talk about why gender inequality is bad and why we have to change this system, where women are oppressed and treated as less, as smaller and less worthy.

First, gender inequality limits potential not just for women, but for entire societies. Think about the girl who dreams of becoming an engineer but is told, “That’s a job for men.” This matters because words like these don’t just break dreams they shape a girl’s belief about what she is allowed to be. Think about the woman who has brilliant ideas but stays silent in meetings because every time she speaks, someone interrupts her. This is not just rude it reduces her visibility, her chances for promotions, and her ability to be taken seriously These are not isolated moments they happen every single day Talent has no gender but opportunity often still does. When we deny women, we lose doctors, engineers, leaders, artists and thinkers who could change our future or turn the world into a better one.

Secondly, gender inequality affects and prevents economic growth. Imagine a woman working twice as hard, taking twice as many shifts and still earning less than a man. Do you know how that feels? I can tell you. It does not feel nice

It feels unfair. It feels exhausting. And most of all, it feels like no matter how hard you try, the finish line keeps moving further away This wage gap doesn’t only affect her bank account it affects her entire life. It means less independence, less security, and fewer choices It means worrying about rent, about food, about the future while knowing that the only reason for this struggle is her gender And when millions of women are held back like this, whole economies suffer. Progress slows down. Innovation disappears Potential is wasted

Thirdly, gender inequality creates deep social injustice

Think of the girl who is not sent to school because her education is seen as unnecessary

Think of the woman who walks home at night with fear in her chest and her keys between her fingers

Think of the victim who is blamed for her own pain, told it was her fault because of the way she dressed or spoke.

This is not just inequality

This is a system that teaches women to be quiet, to be small, to accept less and teaches men to feel superior, even when they are not

But here is what we must understand:

Gender inequality is not natural. It is not tradition. It is not destiny. It is a system created by humans and that means it can be destroyed by humans too.

Change begins with awareness.

With education

With speaking up.

With men who choose to stand beside women, not above them

With companies that choose fairness over profit.

With governments that choose equality over power

And with us Right here Right now

Because every time a girl is told “you can’t”, we should answer “yes, you can” Every time a woman is silenced, we should amplify her voice. Every time inequality shows its face, we should refuse to look away

We are not asking for special treatment

We are not asking to be placed above anyone. We are simply asking for what should have always been ours:

Respect. Opportunity. Equality.

And until that day comes, we will keep speaking. We will keep fighting.

And we will keep believing in a world where being born a woman is not a disadvantage but simply a part of being human.

By Livia Felden

When it comes to fiesta, people often imagine parades, dancing or music – a celebration of togetherness and joy. But what if sustainability can be a fiesta? What if designing greener cities is not just a responsibility, but a celebration of human innovation, collaboration and care for the planet? When we see sustainability as a fiesta, we begin to recognize how people around the world are “celebrating” sustainability on Earth through inventions, systems, and ideas that move in rhythm with nature rather than against it. Sustainability can be seen as a fiesta because it brings communities together to celebrate a dance of creativity, shared responsibility, and innovative ways of caring for the city we all live in.

Act One: The Green Stage – Hydroponic Vertical Farm, Shanghai

Every fiesta needs a stage, and in Shanghai, that stage rises vertically glowing, green, and full of life. The Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District showcases one of the world’s most advanced celebrations of sustainable urban food production: the hydroponic vertical farm.

If Shanghai offers the stage, Melbourne brings the rhythm. Every fiesta has a beat that unites people, and in the sustainability fiesta, that beat is community. The CERES Fair Food System demonstrates how distribution, which refers to the journey from farm to table, can become a dance of shared responsibility

Based in the CERES Community Environment Park, this system reshapes urban food access Through an online platform, citizens order organic, locally grown produce delivered by electric vehicles, reducing carbon emissions. Pick-up points across the city ensure convenience, and reusable packaging replaces single-use plastics. CERES also supports more than 150 small-scale farmers and provides fair-wage employment, including opportunities for disadvantaged communities

In this act of the fiesta, the rhythm is not created by instruments but by shared values, such as justice, respect, and cooperation CERES shows that sustainability is not only about saving the planet but also about celebrating human connection. Sustainability as a fiesta cannot be celebrated by a single person. Instead, it is a dance we perform together.

Seeing sustainability as a fiesta allows us to understand city innovation not as a burden but as a celebration. These cities show that sustainability thrives when people design, move and act together, just like dancers following the same rhythm from different corners of a festival. In this sense, sustainability is not a distant ideal but an ongoing celebration shaped by the choices we make each day Every new idea adds another beat to the global rhythm of caring for our planet. The fiesta has already begun, and all of us are part of its dance.

By Feifei Liu

Yearning for Christmas Yearning for Christmas

All I Want for Christmas Is the Right to Celebrate It

All I ever wanted for Christmas was to be allowed to celebrate it Growing up in a Western-centric world, much of the media I consumed reflected Western traditions. As a result, Christmas was presented to me as a magical, joyful holiday filled with twinkling lights, candy canes, and evergreen trees I vividly remember being obsessed with the original Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and an endless rotation of Hallmark Christmas films. Media has a powerful influence on children, and naturally, eight-year-old me desperately wanted to experience that joy for myself.

However, I was an Indian Hindu living in a predominantly Muslim country. When I asked my parents if we could celebrate Christmas, I do not think I had ever received a faster refusal. Still, I persisted. I begged relentlessly, captivated by the idealism and excitement the holiday represented. Eventually, they agreed.

We went searching for a Christmas tree and decorated it just two days before Christmas. At the top, instead of the angel that came with the tree, we placed a handmade star an intentional compromise that respected our beliefs. That night, I went to bed brimming with anticipation, convinced that Santa Claus would somehow find his way to me

The next morning, I ran to the tree, only to find a few balls of lint and fallen tinsel beneath it. Unsurprisingly, Santa had not delivered gifts to a Hindu child who did not even truly believe in him. Confused, I asked my parents, who struggled to explain and chose instead to avoid the conversation. Later that day, at a Christmas party, I asked one of my non-Christian peers about it. They responded bluntly, “Santa isn’t real ”

Oddly enough, I was not devastated. Deep down, I had always known Santa was a commercialized figure a myth crafted for children. Still, a small part of me had hoped that perhaps his Christmas miracle might extend to me as well When I returned home and told my parents, they reminded me that I was Hindu and proud, and asked why I needed Santa at all. But I wanted him not for belief, but for belonging.

Ironically, many of my holidays revolved around Christian celebrations such as Christmas, Easter, and Halloween, despite living in a Muslim country. Meanwhile, there was little space or recognition for Diwali or Holi. I was expected to celebrate Christmas, yet no one celebrated my festivals. This contradiction confused me deeply, and I asked my mother why She gently responded, “I don’t know, chunnu (my love in Hindi), but if you really want to, let’s go to the Christmas market.”

So we did traveling across town after a tantrum that lasted longer than usual That visit reshaped my understanding of celebration The glowing lights strung from pole to pole, the scent of gingerbread and hot chocolate, the towering decorated tree at the center, and children laughing while parents talked—it all felt alive with warmth and community

That night, we returned home and prayed, thanking our Lord for the day and sharing stories about the traditions we had witnessed from other cultures. We never put up a Christmas tree again after that year, but we always made sure to visit one In doing so, we found a way to appreciate the beauty of other traditions without losing our own.

By Saanjhi Dubey

Shopping has become one of the strongest traditions of Christmas. Many of us don’t mind spending a little extra at this time of year to buy something thoughtful or original for our family and friends. But let’s be honest: at its core, this is a tradition that businesses understand extremely well. They take full advantage of it, pulling out all the stops to attract as many customers as possible. The festive atmosphere plays its part, but companies do the rest–and spoiler: it works, or at least that’s what predictions suggest

While Christmas is a joyful religious celebration for many in the Western world, for others December 25th can be a source of frustration, anxiety, or even boredom. The idealized image of smiling families, abundant food, and overflowing love often contrasts sharply with reality For many people, the season is marked instead by family conflict, loneliness, financial strain, consumer pressure, and overindulgence in food and alcohol. These are some of the less glamorous truths of Christmas.

This reality is reflected in public services Hospital emergency departments often see an increase in cases involving accidents, fights, heart attacks, and even suicide attempts during the festive period. Few people stop to question whether the gifts they buy are genuine expressions of affection or attempts to fill an internal void–or perhaps simply responses to relentless advertising.

Loneliness affects both the young and the elderly at Christmas. Feelings of desperation increase, and in some cases people harm themselves. Psychiatric services come under particular pressure at this time of year Although the number of emergency attendances is not necessarily higher than during the rest of the year, services are often less well staffed, meaning patients may have to wait longer for support (Hughes, 2023).

Despite Christmas often being described as a time of kindness and goodwill, this is not always reflected in reality. During the holiday season, incidents of assault tend to rise, with alcohol frequently involved. These situations can occur both within families and in the wider community. Rates of sexual assault and domestic violence also increase, and many of these cases end up being treated in emergency departments (Hughes, 2023)

According to NHS England, in the UK, one in six adults experiences depression (Office for National Statistics, 2021), and Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) affects one in 20 people (Healthwatch, 2023). A recent poll showed that a third of people feel their mental health declines during the festive period (Mental Health UK & Skipton Building Society, 2022).

To put this into perspective:

An estimated 4% of people in the UK (around 2.7 million) spend Christmas Day alone.

73% experience loneliness and isolation during Christmas and festive periods, even when surrounded by others (Shervington, 2024).

As you can see, this is not something experienced by just a few I have experienced it myself. I remember enjoying Christmas with my entire family when I was younger. However, as the years passed, I found myself feeling increasingly alone Last Christmas, it was just my dad, my mum, and me This wasn’t because relatives had passed away or moved far away– it was simply the result of various events in my family that led to us sitting alone at the table.

As a 12-year-old, I didn’t fully understand it, but it shaped my emotions around Christmas. Watching my friends receive ten different presents from twenty different relatives didn’t feel great. It made the contrast even more painful.

Last Christmas, a friend called me and said, “I’m afraid. I’m spending another Christmas alone.”

How was I supposed to feel hearing that? She was on the other side of the world, with no family, no girlfriend, no friends around her–not even me. It hurt to think that someone I cared about was completely alone on a day that is supposed to represent togetherness So I made sure to call her, to wish her a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. Because there are many people like her, and sometimes the least we can do is remind them that they are not alone.

At the end of the day, these festivities do not define our worth or our happiness. Christmas is just one day out of 365–a day celebrated by some religions, and heavily commercialized by many industries. Before all the advertising, it was meant to be a time to slow down and enjoy the presence of others.

This is an opinion piece. It is not written to provoke pity for those who struggle during Christmas, but rather to invite reflection. Because behind the lights, the music, and the gifts, there is another side of Christmas one that deserves to be acknowledged.

By Anonymous

NHS England. (2023, December 18). Christmas: a time of joy, happiness and goodwill to all NHS England North East and Yorkshire Shervington, J (2024, January 4) How to optimise your mental wellbeing during the festive season Mates in Mind Office for National Statistics (2021, October 1) Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: July to August 2021 ONS

“Born in a Great Family”

“Born in a Great Family”

Hidden Stories around the Campus

Hidden Stories around the Campus

In Western culture, before you’re born, you’re already defined. You’re shaped by a series of sounds that come out of your loved ones’ mouths, the name they have chosen for you. The only tag you will carry to the grave.

Mine is Uxía. My mother chose my name, not for any particular reason. Uxía. It is not Spanish, it is not Portuguese, and I have always hated it. At least, I love its meaning, “born in a great family.”

Growing up, it had always been my paternal family and me. I could recall a hundred memories with them: cooking traditional recipes in my grandma’s wood-burning stove, hearing my aunt tell me stories about her crazy adventures in Turkey, and all sitting at the Christmas table.

My parents? They were also lovely. My dad would be out working from 7 until midnight, and would come back to play with me. My mom would pick me up from school with a warm plate of my favourite food, even though she had already eaten.

At times, I did start to feel a bit odd. I started seeing how my parents weren’t there when I was with the rest of my family, how my dad stopped playing with me, and my family told me that ‘it was best not to follow my parents' steps.’ And honestly, they were right. My parents were never there. I loved them, but I did not want to be like them. I wanted to travel, to have my grandma’s jewels, to sit again at the Christmas table, and to go with my aunt to Turkey. I was so focused on being like them that I never noticed how they were pushing away from me.

The next year, on my 11th birthday my parents couldn’t make it. It was just my grandma and me. I was upset, sitting alone on the verge of tears, and she did not talk to me at all. I realized I was alone.

Shortly after, my grandmother looked at me. “Uxía.”

“You’re just like him,” she cursed. “You’re just like your dad.” I did not understand why she said that. I hated him. I hated that he was never with me. I hated looking like him, our sad gazes, our curls, our smile. I only had my mom’s eyes, and through them I cried.

When midnight came, my dad arrived, and so did my mum. That stranger who lived in my house just when I was asleep rushed. He rushed to grab me in his arms and clean my tears. His clothes were dirty with wood dust and I could tell. It itched my skin.

But still, that night, my dad played with me.

He sat down with me the next day. His eyes looked into mine, with a soft smile. He was in the house for the first time in years.

“Your grandparents have a lot of money.” My dad suddenly said. It had never crossed my mind that they were actually millionaires “We’re disowned.” He added.

No more Christmas dinners, no more travel tales, no more visits no more anything. My eyebrows frowned, my mind rushed to understand “Why?” I was numb. I just wanted to hear the reason as my memories with them were gripped in my mind, as it was the only thing I had left.

“Because we’re poor, Uxía.”

Four words. Four words took me to see it: missing birthdays, dirty clothes, them not eating, my grandparents not treating my parents with the same warmth I felt something inside me ache: we never had any money, and still, I hated my parents for it. It was just the three of us, just our small house, just our money, just all we had just poor people.

My parents looked at me, worried They expected me to shout, to cry, to hate them for not having enough money, for being poor people I dreaded. With another four words, I replied:

“They’re dead for me.”

Over the next few weeks, this kept me awake. I started feeling nausea that did not let me fall asleep. How was I treating my parents? How was I idolizing my grandparents? The memories swirled around my mind, and I tried all night to fight against them, to fight against the fact that I hated the people who had been sacrificing their lives for me. I was stuck in a village, repeating our family cycle.

So, for the first time, I was Uxía, alone A girl with her Galician name Her poor name. But, at least, I still had my mom and my dad. During one of those nights, my overthinking was interrupted by a loud bang coming from my parents’ bedroom My legs began to run without me realizing I opened my parents’ bedroom door just to see an image I would never forget: my dad had dropped dead onto the floor.

We carried him into the car and rushed to the hospital, just to learn a few days later that he had a condition in his lungs that could kill him at any moment I almost lost my dad, and he could die at any time I had lost, or rather buried alive, my paternal family, and I was not willing to lose my dad. I remained numb, and I went to the doctor:

“Why?”

“His lungs developed an immune reaction towards dust. He has probably been breathing in large amounts of it for years. Don’t worry. He’s okay.” But I knew it wasn’t. Dust. Wood dust. My grandparents worked with wood, and my dad worked with them. My dad worked with dust, but with no protection The dust got into his lungs year after year and accumulated His lungs began to dry out, his breathing became heavier, he couldn’t play with his daughter. He had to work, breathe dust, give money back, take care of us He had to die, to die for mom, to die for me

My dad was about to die, and I knew who the murderers were.

My grandparents.

The weeks went by, and my dad kept getting weaker. He was at home, and I did not know what to do. I just stood there in silence, took a piece of paper, and drew. My dad loved art, and so did I. If none of this had happened, could he be an artist? Could I be an artist? My destiny was my father’s And I didn’t want to be anything other than who my parents were. I would rather die being a poor person with values who fought for her family than die being rich and indifferent

And by those values I lived, taking the present in my hands: learning how to cook, taking care of our chickens, growing crops in our garden, focusing on high school to get a job, hopefully paying off our debt ... Until one day, someone knocked on our door It was a man whom I had never seen before He talked to my mom for hours, but he didn’t come in. Only later did I learn that he was my maternal uncle, asking my mom for forgiveness.

The next day, I met my maternal grandmother. Odila. She was the opposite of the family I already knew. She had no teeth, looked old, not so put together, and spoke Galician. I tried not to judge and smiled at her as she looked at me Her eyes were watery “Uxía,” she said, warmly, with love Over the next few years, I began seeing her weekly. She would sleep with us and talk to me. She taught me the names of birds, trees, recipes, how to crochet, sew, dance, laugh, and love She taught me not to be my dad, not to be my mom, not to be her, but to be myself.

I remember when I once baked for her. Later, she came up to me with a piece of paper and a pen. I started listing ingredients as she stared, frozen, at the paper She did not know how to write

I spent the next few months teaching her how to read, as she asked me to write the stories of her childhood for her just so she would never forget them. And just like that, I am telling this story to you: my story.

During the next few years, I felt lost, but I found a way to raise my voice, and others’. I found a way to share the stories of those who cannot write them. One year before coming here, I got into the best pastry school in my area, which would have granted me a job, having all I needed right in my hands. But still, my grandma told me, “You’re smart enough to study, kid” And she might have been right, so I risked it.

Three months later, I heard about UWC. This February, I was given the only spot my NC had for UWC Atlantic, and a full scholarship.

In two years, I’ll go to university, or not who knows.

But right now, I have found myself learning. Learning that I’m more than a conflict, that I am not divided, that I am full of two countries and two family experiences. Learning that it might not have been my fault, and that still, I chose to fight for it and make the most of it.

Thanks to that, I’ve gotten the opportunity to keep going, sharing the stories of those who cannot write them. So here goes my tribute to INK magazine, my own story, my own identity:

My name is Uxía, and it does mean “born in a great family,” even if I wasn’t looking at the right side of it for my whole life.

By Uxía Fernández Fernández

Color Fiesta at the Colors Left Behind Color Fiesta at the Colors Left Behind

what she paints anymore: the canvas faces days, half-finished.

By Giuliana Clementin

: A Winter fiesta

The moment I step into a শীেতর �মলা, the first thing that welcomes me is the smell, that warm, smoky sweetness rising from the rows of িপঠা (sweet cakes) stalls It reaches me before the music, the colors and before the crowd, and even now, as a teenager, I feel the same thrill I did as a child waiting all year for this day.

For a moment, I forget I am merely a visitor, I feel as though the festival has been waiting for me

People wander around in slow gentle waves, wrapped in soft shawls and thick winter কাপড় (clothes), each colour glowing like a small flame against the grey of the season Someone tunes a harmonium nearby, someone else calls out to a friend; and somewhere in the distance, children participate in কিবতা আবি� (poem recitations) with the kind of confidence I never had at that age In the crisp, winter air, every sound feels sharper, as if the cold has polished the world clean

I walk toward the িপঠা corner, the heart of any true শীেতর �মলা (winter festival), here, the craft is part performance, part inheritance. The women behind the stove don’t just make িপঠা, they shape memory.

I watch them dip their hands into smooth batter, their movements so practiced they look choreographed, the flick of the wrist as they pour it onto the pan, the sharp hiss as oil greets the mixture, the gentle turning, the knowing look; all of it speaks to years spent perfecting a skill both sacred and simple.

And every time I stand here, another winter rises in me, a core childhood memory of watching my mother or grandmother create warmth in the cold, their hands moving just like these women’s hands, their laughter mixing with the steam.

Back then, I thought winter existed solely for িপঠা. But a শীেতর �মলা is more than food. It is culture arranged in concentric circles.

One corner bursts with �লােকর গান (folk songs) rising like steam over the stoves.

Another corner hosts children and elders standing under fairy lights, reciting poems that everyone already knows by heart.

Stalls sell nakshi katha, winter shawls, clay toys, handwoven baskets, each item carrying a story older than the festival itself.

And of course, the ever-present �ঢাল (drum) beats from somewhere unseen, the rhythm guiding the movement of the entire mela.

Everywhere I turn, the place feels like a fiesta, joyful, crowded, chaotic in the softest, most comforting way

Children chase each other between stalls, families sit on straw mats eating patishapta , someone bargains loudly over a scarf; someone else insists I try their new batch of bhapa pitha because “এইটা একদম গরম (its freshly warm),”

As I wander deeper inside, I realise once again that the magic of a শীেতর �মলা is not in its size or its noise, but in its contrasts, the bite of the cold and the warmth of voices, the crisp winter air and the sweetness of গুড় (jaggery), the early dusk and the flicker of fairy lights.

When I finally leave, my hands are slightly sticky from গুড়, my hair smells faintly of smoke, and my heart feels unexpectedly full the exact feeling I used to carry home as a child, when winter meant light and laughter and waiting for this one �মলা because this winter festival is never just an event

It is a reminder of belonging a small fiesta of memory and meaning that stays with me long after the cold has passed

By Athena Rahman

Food is at the heart of the Middle East and the Arab world. It is one of the pillars of our shared, yet diverse, culture–even more so during the harsh, dry winter time.

From the hearty savory dishes to the sweet and dense desserts, every meal is a celebration in its own way! I always loved Warak E’nab (stuffed vine leaves), which you might've heard about or even had! It seems straightforward–just rice inside rolled vine leaves but the reality is that it’s one of the most laborious dishes out there; it's a labor of love more than anything.

I particularly remember jumping down from my school bus under the rain and running into my grandma’s house, then having her feed me that first bite while the pot is still simmering on the stove. Then I would sit down in the living room and enjoy a plate with my cousins. To me, that feeling of togetherness is the purest form of love there can be, making every bite a mini-celebration of family and love.

Not all dishes are as complicated as this one, though. On the opposite side of the spectrum we have the humble lentil soup. Consisting of boiled lentils, onions and spices, it is the staple food of the Arab world during the winter. Fun fact: This food specifically is basically renowned as an “official winter announcement” for most Arab households particularly the Levantine Arab ones.

Although Arab food culture is incredibly rich in spices and intense flavors, it is no less rich in sweet, decadent dessert. And you cannot say ”dessert” in Arabic without saying Om Ali (literal translation: Ali’s mother) which can be considered a type of bread pudding, with a puff pastry or bread base, any type of bread, really! Then that bread is soaked in a mixture of spice milk and baked. Being first recorded in Egypt around the 13th century, it is one of the longer standing pillars and celebrations of Middle Eastern history. On the more modern side, going back to the Ottoman Empire, there’s sahlab. Sahlab is a hot, sweet, and thick drink made across most Arab households, bringing warmth both actual and emotional to people’s hearts during the rough winter seasons.

All seasons are special in the Middle East, and all of them come bearing gifts. But winter is one I especially hold dear. It’s the one season where life slows down, family gets together, and every day is a little celebration of community whether we notice or not.

By Hala Mughhrabi

Then I go home, my phone still ringing with other people’s laughter. I promise myself, next time I’ll get it right next time I’ll dance, next time I’ll belong.

And when the next invitation comes, I’ll iron the shirt again, practice the smile again: the same beginning, a little more tired, a little less sure it ever ends.

By Giuliana Clementin

“Fiesta” for Everyone? “Fiesta” for Everyone?

* Disclaimer: This article is not aimed toward anyone, and its purpose is not to criticize, but to instill reflection.

Today, I want to tell you the stories of two of my friends: José and James.

José was born in Riohacha, one of the poorest cities of Colombia, to his mother, Carolina, and has two younger siblings. José’s dad abandoned the family when José was seven; he was never seen again. Carolina barely graduated elementary school, as she had to help at home instead of continuing her education. She became a housewife, until her husband abandoned the family. Carolina, with her basic academic skills, now had to feed three mouths on her own. She worked two low-paying jobs and left home every day before dawn. José, the oldest, had to prepare breakfast for his younger siblings, help them dress up, and walk with them twenty blocks to arrive at the local rural school. His faded pencil case held only half a pencil and half an eraser. Every afternoon, he would arrive at his house and study till dark, when the light from the sun stopped illuminating his re-used notebook. There wasn’t electricity in his house, but José is resilient—he went to the street and sat under a light post to be able to finish studying everything he could. He got ahead of his classmates in every subject, and some years later, graduated first of his class, despite his difficulties.

He applied to a well-known international boarding school somewhere in the European countryside; there were, however, only two scholarships available for hundreds of applicants in Colombia, and he had to take the in-person exam in the capital. His mom, deciding to believe in her child, started baking and selling cakes to the neighbours to pay for the bus fare. As you may already expect… yes, José made it. The program was difficult for him—he had to learn English on his own, and his pronunciation was sometimes mocked. But hey! José from Riohacha, Colombia, that boy that once studied under a light post because his house had no electricity, is heading to Harvard this year.

James was born in Los Angeles, USA, to mother Sarah and father Donald. He is a single child. James’s parents met during their Ivy League years and later went on to complete MBAs at a top business school. James has always attended prestigious private schools, where he was driven by his chauffeur every morning. One afternoon, after researching on his latestgeneration laptop, he found out about a wonderful opportunity to study abroad at a selective international boarding school in Europe. The regular admissions process seemed lengthy… and perhaps unnecessary. His parents could afford to pay full tuition instantly, so he applied through a faster global admission route. Some months later, he was sitting in math class at that school… but he already knew all the content. How boring! He ended up receiving near-perfect grades. He only struggled in English, for which he got a private tutor his parents knew back in LA. Oh, and the same one helped him draft his stellar university essays. James also got into Harvard. He’s going to study Economics so that he can continue his parents’ international business.

As you may have already guessed, José and James aren’t really my friends, but they represent many people on this campus that have inspired me to write this. José and James are fictional examples that unfortunately mirror the not-so-fictional unequal world we live in.

So, returning to “fiesta,” are all celebrations the same? Yes, both students got into the same university. Both will celebrate. But while José fought language barriers, financial obstacles, and structural inequality, James walked a path already smoothed for him. Before celebrating your own college admission, pause. Reflect on the opportunities that carried you. Remember that in this very school you’re standing, there are students who had to fight harder, refugees who studied while fleeing war, girls denied education, and families struggling just to bring a plate of food to their tables… and who are still standing. Meritocracy is a myth, because it celebrates merit (a result) while ignoring the paths people take to reach it.

By Facundo Almada Abreu

Human Library Speech Human Library Speech

Hi I’m Ziva and I have ADHD - which stands for Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder. Today I’ll be talking about the impact that this has had on my identity throughout my life, particularly after my diagnosis.

I’ll first define some terms for those who don’t know. Neurodivergent refers to anyone with a learning disability - for example ADHD, Autism, OCD or Dyslexia Neurotypical is everybody else - those traditionally considered as normal, the people mainstream society was built for.

Due to the past neglect of research into ADHD in women, the stereotype of the hyperactive little boy who can’t sit still and wants to lick all the walls and climb on everything persists. But in reality the impacts of ADHD are way more complex and way more wonderful but come with much darker implications.

Sooo how does ADHD affect my life?

ADHD causes a lot of problems in my life - and not just academically. It causes me to be late to all sorts of things: doctors appointments, codes, family dinners, friends’ birthday parties and more - putting a constant strain on my reputation, friendships, academic achievements and consequently my self esteem. ADHD makes me overshare, over-eat, it makes me overexcited. But more than anything, like a web connecting all of these issues, it makes me overthink; not enough attention is given to the impact of that.

I was also diagnosed with a mood disorder that a lot of people with ADHD have called Rejection sensitive dysphoria, or RSD for short. It is a condition where one experiences extreme emotional lows upon facing rejection, lows which are usually disproportionate to what actually happened; it’s important to establish that this pain is felt in response to perceived rejection, meaning that it doesn’t necessarily have to be realit’s not rational and I probably perceive a lot more rejection than what is really there

This does not pair well with ADHD. Being someone who shows up late all the time, doesn’t do most of their homework and talks either too much or too little, I can face a lot of rejection which honestly affects my mood and quality of life significantly at times

Soooo now I’m gonna talk about how my ADHD relates to community and belonging.

Identity is closely linked with belonging, determining where and with whom you belong For example, you’ll see people in the same national groups hanging out, people with similar sexualities or people with similar styles. The same goes for being neurodivergent Whether consciously or not, you naturally gravitate to others like you. And in a world where the majority of neurodivergent people can easily feel misunderstood, we often form our own communities.

Sometimes I love the community that my neurodivergence brings but honestly, other times I hate it. Being able to label myself as having ADHD has helped me to understand myself more and why I identify with the things I identify with, but the idea that I am defined by it upsets me. The communities us neurodivergent people create still have their own rules and norms, norms which can, in my experience, be harmful and exclusive, overshadowing our individual nuances that lead to true connections. (But take this with a pinch of salt because as I said before, my RSD can make me see rejection when it isn’t really there).

I don’t always feel that I fit in super well into this neurodivergent culture which can make me feel like I’ve betrayed my own people, question my identity and wonder if I even belong anywhere at all. I wonder though whether I actually do identify with it, and I’m just reluctant to identify with anything or anyone at too much because I’m scared of being put in a box. If I’m put in a box it restricts me to certain groups and I hate that - I am determined to keep the door open for all kinds of friendships.

Unfortunately, keeping that door open for new friendships is not just about remaining neutral, it's about avoiding the neurodivergent stigma, which although ableism has generally reduced, is still alive and well (for example the r slur which you’ll hear everywhere) When the people I’m sat with are loud and unapologetic about their neurodivergence, I sometimes cringe and feel something wilt inside I am deeply ashamed of this as I know being able to express our identities instead of suppressing them, like so many neurodivergent people have already been socially conditioned to do, is essential

If more of us truly realised that we can still be human while having different or less common personality we could minimise the gap between neurotypical and neurodivergent people. And I am terrified of that gap, it's why I refuse to fully embrace the neurodivergent community for fear of being stigmatised I’m just trying to leave that door open for new people, any kinds of people to come into my life - but maybe minimising and restricting my identity isn’t the right way to do that.

SOOO why did I want to come here and say all of this?

It doesn’t make me sound professional, it doesn’t make me look cooler and I’m definitely not talking about pressing world issues in the way AC conventionally does it But it matters to me because our individual experiences, our inner worlds, all the joy, all the wonder, all the complex individual pain trapped inside of our heads are not talked about enough, and so I feel like I’m really out on a limb here right now, talking about mine But I want people with experiences like mine to be represented in places other than in social media bubbles full of people just like them. I want people who aren’t like me to see this side of me, the one that usually only those closest to me can know, and I do so in an appeal to break down some of the barriers that exist because of differences in our identities

I want the world to be more aware of it - because even if it’s emotional, even if it's obscure, subjective, irrational, even if it seems insignificant, it affects my life in countless objective ways - like when my shame spills out and hurts people that I love, or when there is no closure to all of this suffering because it arises out of something which doesn’t make sense. I don’t have any suggestions about what the world can do to make this better - it just made me feel weird how most of the people I live with know so little about what’s going on inside my head… and I wanted to change that.

By Ziva Jacobson

Latino Christmas in Wales Latino Christmas in Wales

Before you read this, please look up “Santa Claus Llegó a La Ciudad” by Luis Miguel Listen to it while you read this, or add it to your Christmas playlist for next year.

Picture the upper quiet room of Morgannwg house (not that you should know what it looks like Imagine it). Picture study tables put together to become one long dinner table, eight or nine sets of plates and cutlery, soda, pizza and buñuelos. Everything ready for a Latino Christmas Dinner. The only thing missing: the heat we are so used to having during our yule tide.

Back home, I associated Christmas Eve with two specific events: spending the night at my grandma’s house and eating two kilos of ice cream to combat the tormenting heat of summer (remember, seasons are opposite in South America!). Being here, in Wales, Christmas Eve means my family will spend the night at my grandma’s house without me, and instead of two kilos of ice cream I’ll have two layers of coats to combat the tormenting cold of the Welsh winter

Both years I was lucky enough to be allowed to stay on campus during Winter Break. All students staying are required to move to Morgannwg, a guest house on campus recently rebranded as the morgue by AC students as a result of disease spreading around. Sick students were quarantined at the morgue until the sickness died down.

LexiCon Fact: Apparently, before Besse’s current location was officially opened, the first generation of Bessians lived in Morgannwg during their first term in 2020. Remember Christina Herre, LexiCon guest speaker and AC alumna? She spent her first year as a Bessian in Morgannwg, and even slept in the bed she had at the time when she came for the conference!

One of the highlights of my IB1 winter break was rooming with Achilles, my dearest second year from The Philippines, who is now studying at Middlebury. We watched films together almost daily: Wicked, The Wizard of Oz, Midsommar, Everything Everywhere All At Once. I remember how locked in he was, waking up early every morning to go down to the gym and study afterwards. I tried doing the same this year, but I found that the earliest I could wake up was 10:30AM. I digress.

Pre-UWC Atlantic, I remember being jealous of characters in Christmas movies who spent their time building snowmen, playing in snowfights (do people actually do that?), and making snow angels on the ground, while I had to deal with the heat. Now, what I had romanticized my entire life was finally happening: cold Christmas!

Except there is no snow in Wales. And regardless, the cold had brought with it no more than romanticized nostalgia, a yearning for the Paraguayan sun that I knew would burn my back and dizzy my afternoons. The excitement and dreamlike jolly I looked forward to experiencing was replaced by an insistent desire to be back home, to spend time with my loved ones, knowing well that this would mean suffering from the incessant heat

Looking for comfort in a shared feeling of melancholy, the Latino students who stayed in Morgannwg during winter break planned a special Christmas Dinner Party. Back home, Christmas Eve is culturally bigger than actual Christmas day; rather than having a Christmas lunch on the 25th of December, families gather to celebrate Christmas with a big dinner on the 24th of December, which often extends to partying until at least 5AM on the 25th. And we remained true to our culture. We spent the whole night gossiping, laughing, looking back at how life was back home. Our Colombian second year Eimy, who now studies at Macalester, told us stories of ghosts and romance all night, until we picked up our phones and realized that it was 6 in the morning. Now, I’d like to extend a public apology to Siân, who lives adjacent to Morgannwg, and had to sleep through our nightly hullabaloo. This year, we made sure to be a bit more quiet. So sorry!

Following our ‘24 Winter Break Latino Christmas Dinner, it is beautiful to see that this has now become a tradition. During winter break this year, we made sure from the beginning of break to plan a nice meal for our dinner. Cooking Paraguayan Mbeju, Chilean & Peruvian Cola de Mono, Sopaipillas and Pizza, we stayed up until 6AM gossiping and singing karaoke, with the short 3AM intermission where we called our families to say erry christmas (most of us have a 3 hour timezone difference). During both years, celebrating Christmas with my familia latina made the experience of being away from home so much easier to deal with.

If you ever experienced similar feelings of nostalgia during your time at AC, I’d recommend reading the novel Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih We study it in Hedd’s English class Ignoring the rather disturbing events of the novel, Salih beautifully encapsulates what it means to be a foreigner, to feel as if you don’t truly belong neither in the place you belong nor in the place you emigrated to. Quoting Salih, “Turning to left and right, I found I was half-way in between north and south. I was unable to continue, unable to return”. The difference is, I have a community from the South that made my time in the North so much better.

By Sebas Orué

To see our previous articles scan the QR code!

Archive