Between a Coop and a Hard Place Jet McCarthy HarvestedMariam Yassine & Mayela Dayeh

NestboundAmir Farrag

ISSUE O4

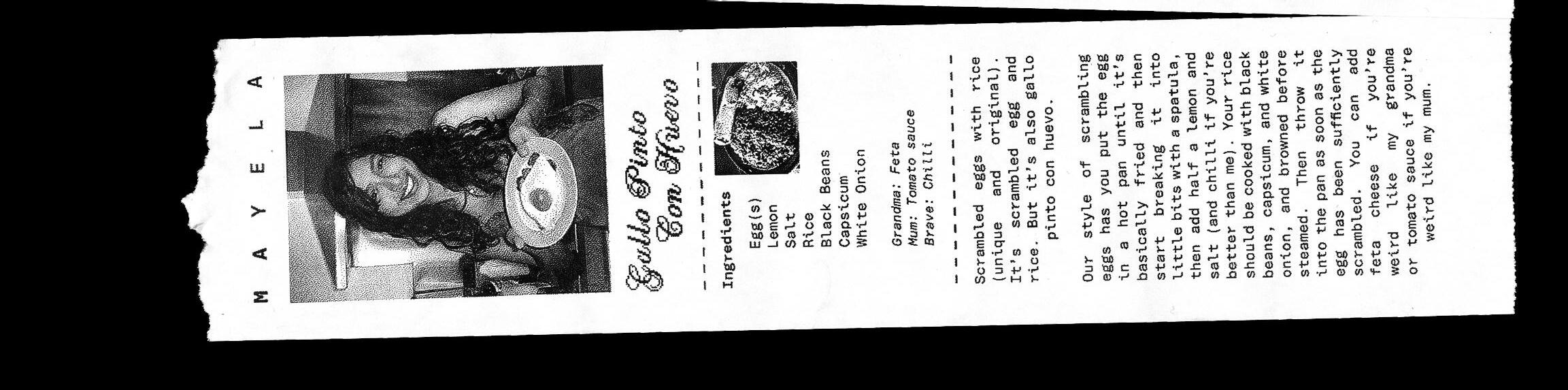

Between a Coop and a Hard Place Jet McCarthy HarvestedMariam Yassine & Mayela Dayeh

NestboundAmir Farrag

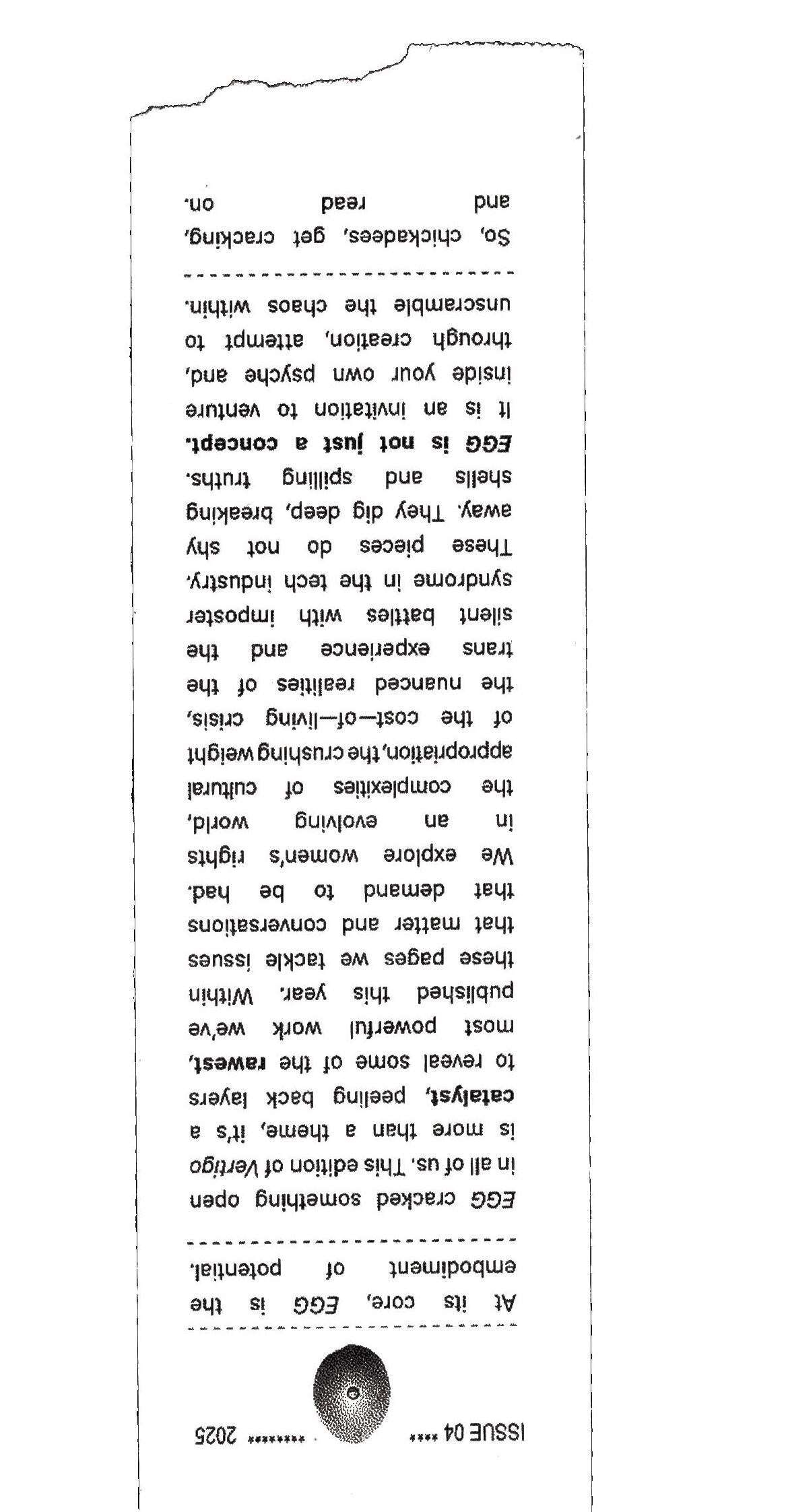

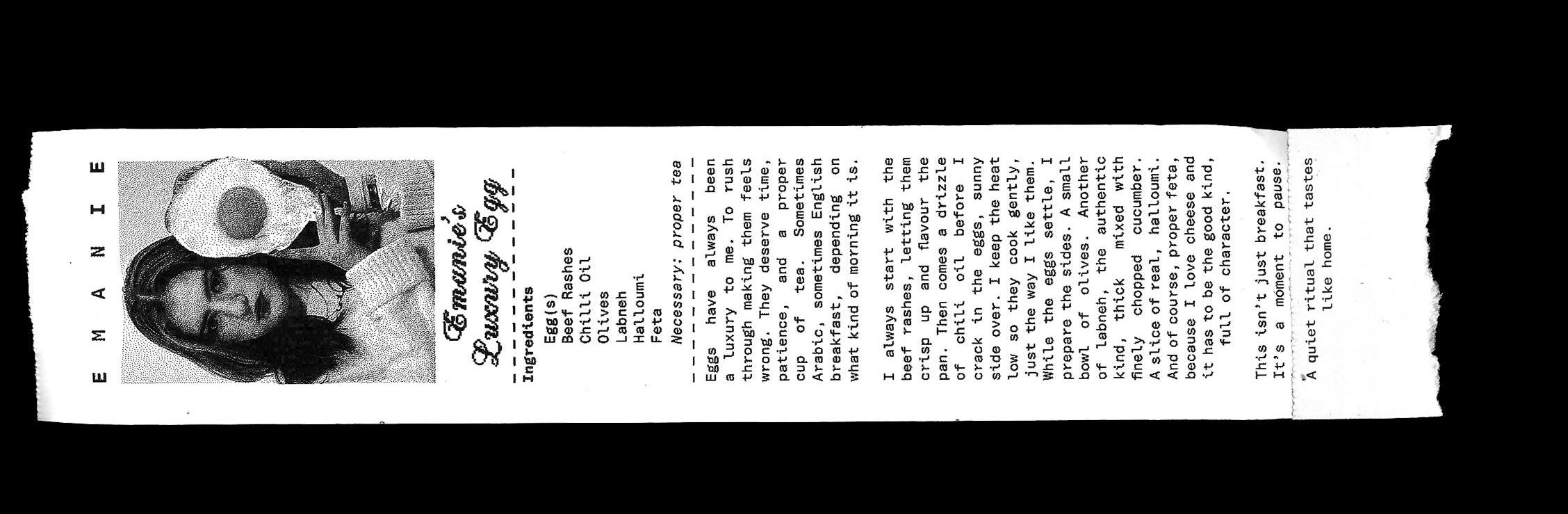

Words by Emanie Samira Darwiche

Design by Arkie Thomas

Vertigo editorial team acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the traditional custodians of the land on which this magazine is written, spoken of, edited, and printed. We recognise their enduring connection to Country to land, waters, skies, and stars and we honour the strength of their cultural knowledge, storytelling, and sovereignty, which has never been ceded.

We pay our respects to Elders past and present, and to all First Nations people whose resistance and custodianship continues to shape this continent.

To acknowledge Country is not a box to tick or a gesture of politeness. It is a reminder that we live and work within a colonial project that has never ended. It is our responsibility to speak from

ceremony, art, song, and story. Before anything was printed, before anything was written, there were always stories.

This year, we hold a sharpened awareness

Ruman

Kimia Nojoumian

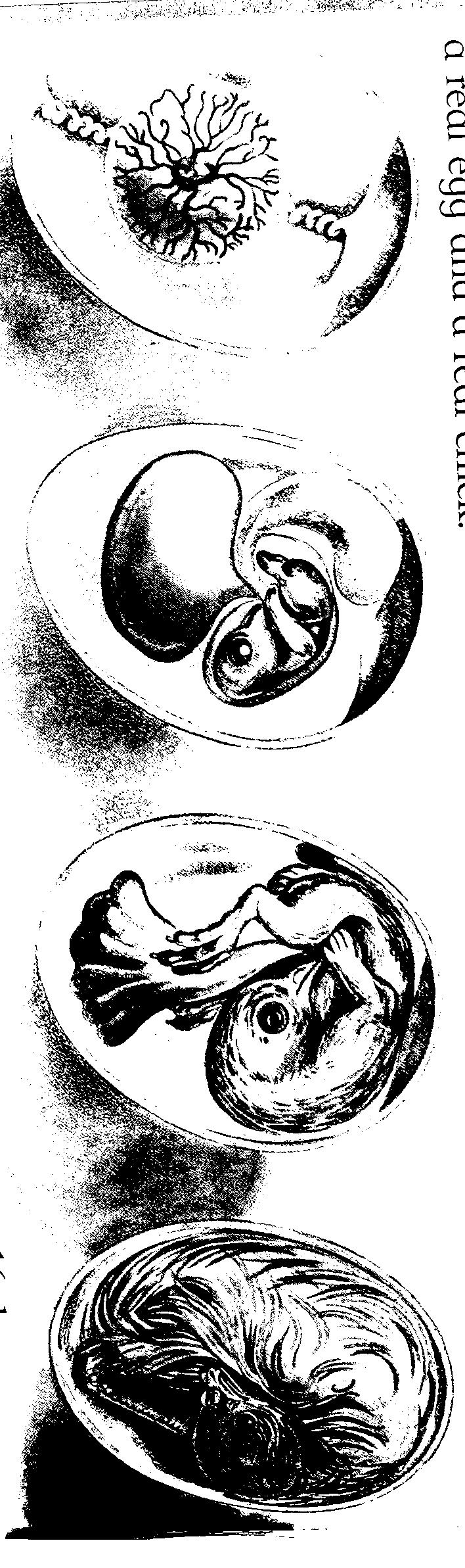

“REPRODUCTIVE ASSISTANCE”

A term which, at first glance, seems innocuous or even positive. Potentially referring to IVF or some sort of procedure that families

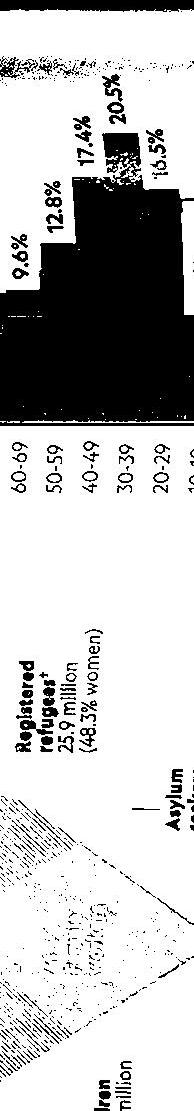

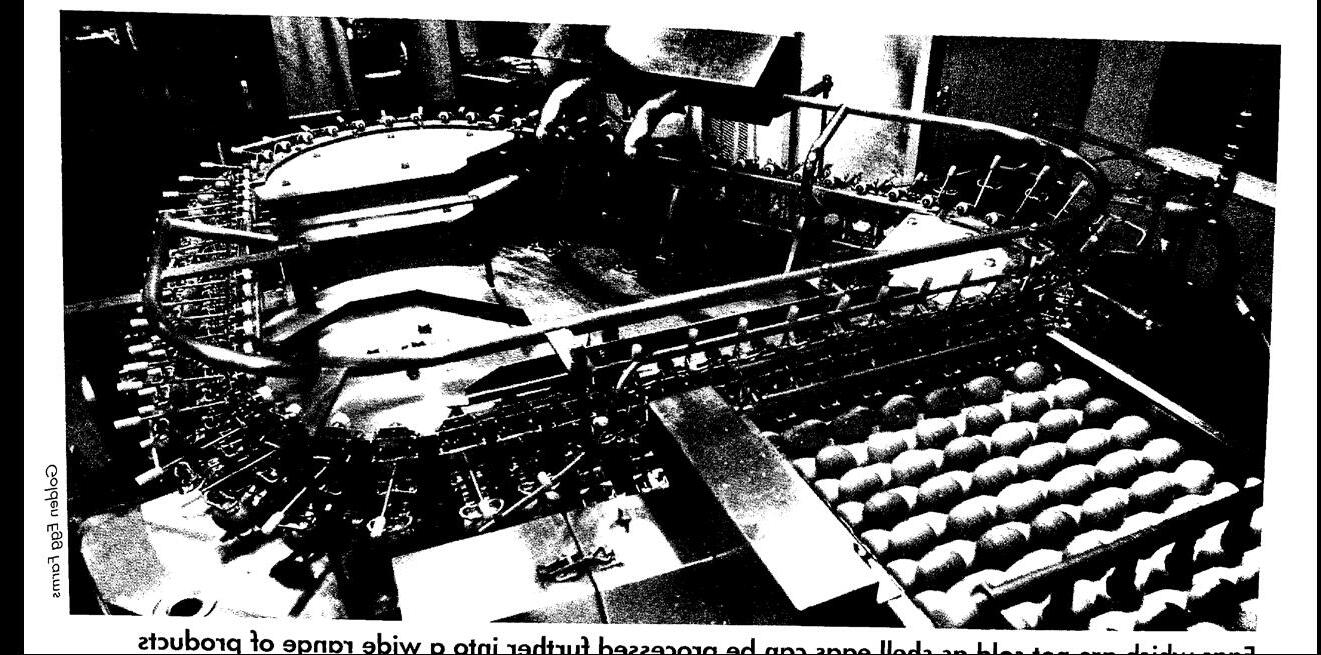

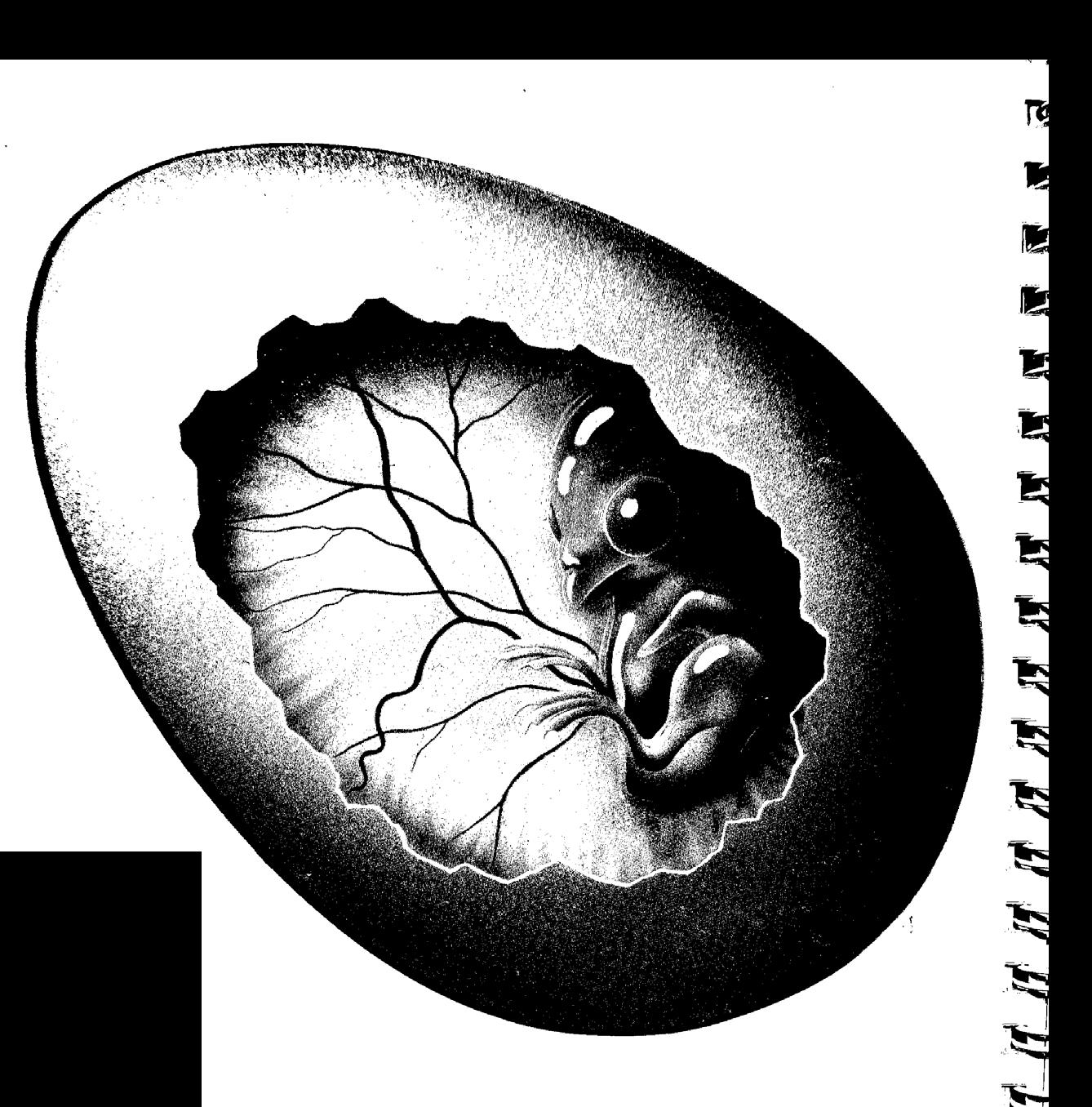

The commodification of human eggs, or oocytes, have transformed them from a promise of life to a product for sale. This trade lays bare the violent systematic devaluation of marginalised, racialised, immigrant women, whose bodies are seen as raw material to be

mined, managed, discarded. and

$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$

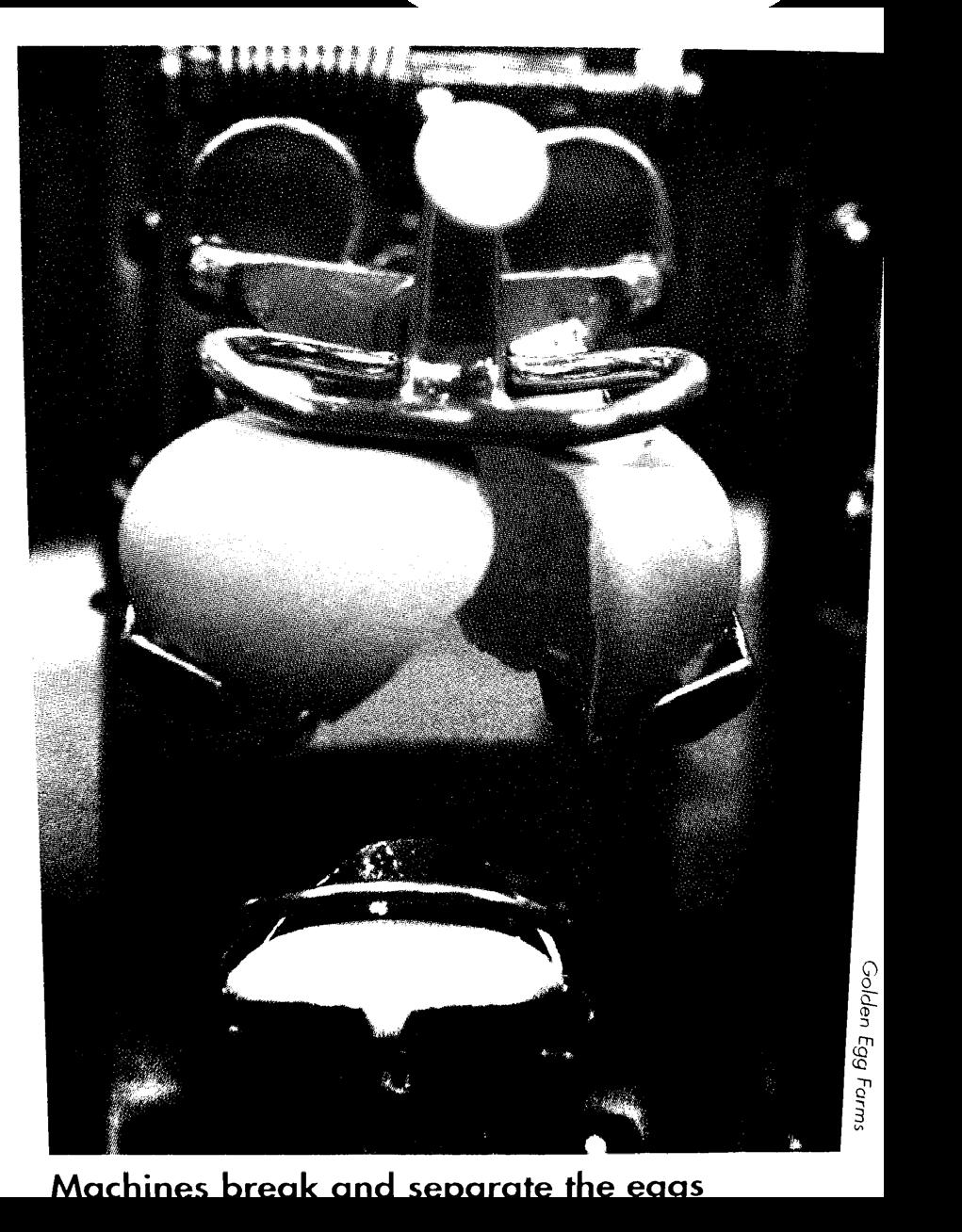

Globally, the market for human eggs is booming, feeding o economic desperation, reproductive anxiety, and global health crises. As instability deepens, the industry thrives, profiting from the bodies of women pushed to the margins and selling fertility as a luxury for the privileged. In countries such as Spain and Czechia, now widely regarded as central hubs in the “reproductive economy”, clinics scout women, predominantly immigrants or those from lower-income backgrounds, to undergo what is essentially human experimentation.

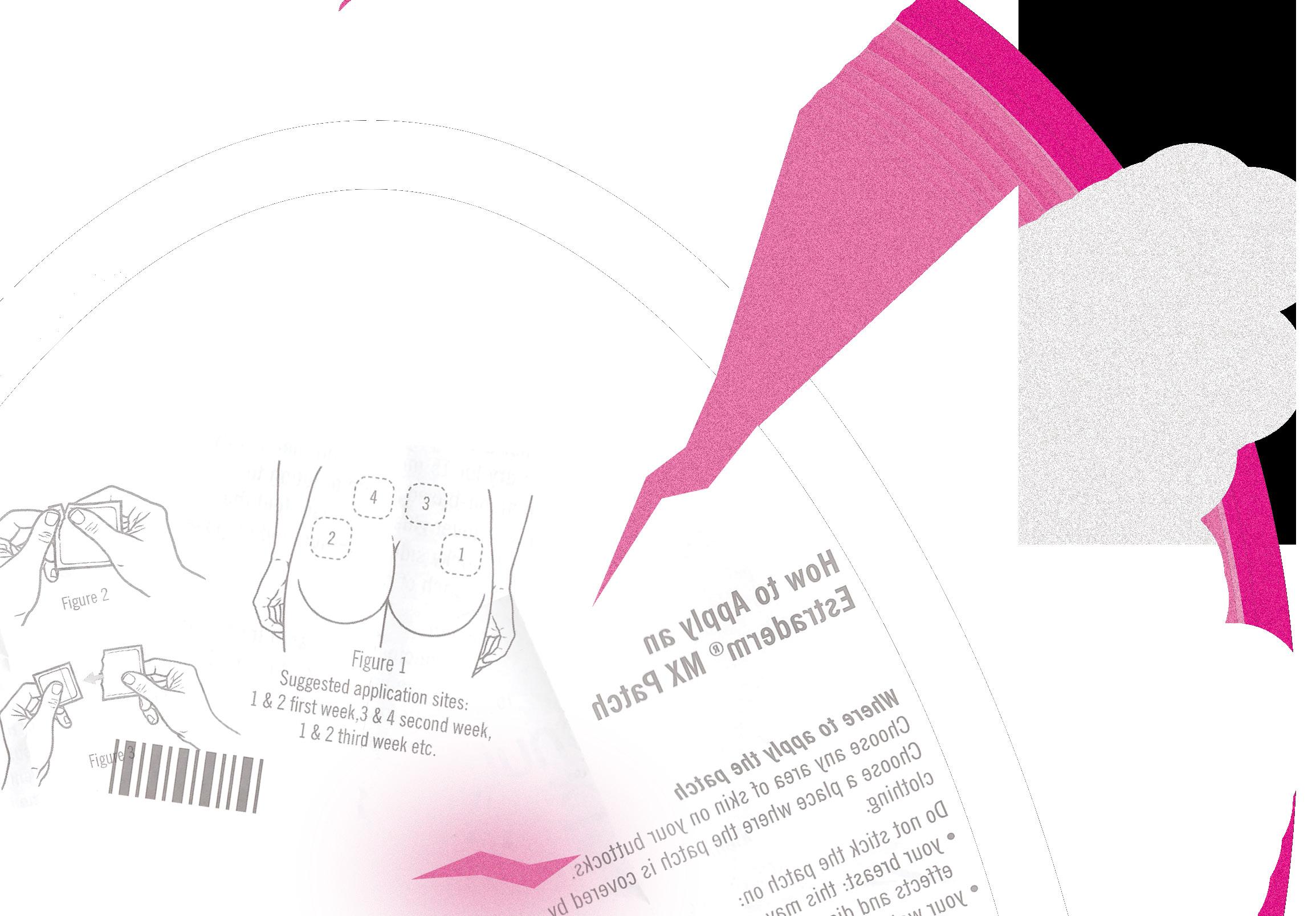

This experimentation? Weeks to months of hormonal injections, followed by invasive surgery to harvest human eggs. In exchange, these women are handed paltry sums, a fraction of the profit their bodies generate.

These transactions are heavily medicalised and shrouded in altruistic language, a concerted e ort to conceal an underlying market logic that grows increasingly extractive as demand continues to rise. The clinics, far from being a neutral actor, encourage exploitative fertility tourism and the deregulation of the system, moulded by neoliberal imperatives, prioritising market e iciency and consumer choice above ethical safeguards.

And it’s no surprise who the consumers of this “product” are. A luent patients, generally from wealthy Western nations, are positioned as entitled consumers whilst economically vulnerable women become the invisible labour force sustaining the system.

These women, primarily from Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Eastern Europe, are recruited through coercion while their participation is framed as voluntary. O ers of employment and financial stability in Western nations—nations that have often destabilised these women’s home economies—target the desperate and vulnerable. These women are transported, pressured into donation through debt or

deception, and left with few resources or recourse. Human tra icking networks have begun to intersect with egg donation pathways, particularly in regions where legal oversight is weak or intentionally neglected.

The racial and colonial dimensions of the trade can also not be ignored. The bodies of women from lower socioeconomic countries are mined like natural resources, their genetic “value” assessed by a market that echoes imperialist nations’ hunger for extraction.

It is now embedded in every transaction where women’s bodies are stripped for parts to fulfill the reproductive desires of the privileged.

This system, like colonialism itself, relies on unequal power relations, dispossession, and the reduction of women to tools of production. This is not an industry detached from history—it is one manufactured by it.

And this violence isn’t confined to the egg trade. It is embedded in broader reproductive exploitation, where women’s choices are dictated not by autonomy, but by economic survival. An obstetrician has told a 2024 Australian parliamentary inquiry (yes, this happens on our own soil) that hundreds of immigrant women seek abortions with her each year. Driven not by freedom, but to avoid breaching their visa conditions where pregnancy can mean punishment, not protection.

Dr Trudi Beck, a GP in Wagga Wagga, described an “unseen population” of migrant women who undergo terminations they would not otherwise choose, because pregnancy would threaten their ability to work and meet minimum visa conditions in physical labour sectors. These women are cornered into medical procedures that sever them from choice over their bodies, not because they want to, but because capital has made their choices inconvenient.

This is forced reproductive control under the guise of policy compliance. The state and the market work together to dictate whose pregnancies are viable,

and whose are not. Whose lives are worth accommodating, and whose are expendable for productivity. These women are not just abandoned; they are actively engineered into silence and compliance. Their labour is welcomed; their lives are not.

The risks they face—medical, financial, legal, psychological—are exacerbated by a near-total lack of post-procedure care or long-term monitoring. The line between consent and coercion is blurred to the point of erasure. And all the while, the egg donor, the pregnant worker, the brown woman with a temporary visa—she is used, minimised, and then forgotten.

In the status quo, the global oocyte trade remains a marketplace disguised as a medical clinic, and reproductive “choice” becomes a euphemism for economic coercion. Economically marginalised and racialised women aren’t allowed to make their own choices with their bodies, lest they become economic liabilities. This logic reflects global inequality, racial capitalism, and the enduring colonial ideology that some lives are worth more than others. And unless we recognise and confront this, the system will continue to thrive at the expense of the world’s most vulnerable.

DESIGN BY ARKIE THOMAS

WORDS BY AMIR FARRAG (he/him) @amirfarrag03

WORDS BY AMIR FARRAG (he/him) @amirfarrag03

Feed yourself to me, nourish me, Let yourself become my own. Drain your blood, let your calf drink. Bleed yourself and let go. I will drink whatever I can. Give yourself up for me, feed me yourself. Feed me your flesh and you will leap the highest. Feed me your flesh and I will leap higher. Bind your legs and watch me leap, Then hear the hunted fall.

Do your calls reach empty burrows, Or do they return clear in the fog?

Prey on small creatures, stain their blood, Feed it to me, then give me yourself.

How can you see me through this mist? What are you looking for?

Hunt for me. Then feed me. Then nourish me. Hunt for me then feed me then nourish me.

Huntformethenfeedmethennourishme. Nourishmenourishmenourishmenourishme.

When my cheek is wounded and red, lay anguish, for you have stained hands. When my cheek is stained red, you lay in anguish, for your hand is wounded.

When you hold me, Do you feel the shape of something missing?

Stained, wounded and red, I will jump higher still, For the flesh you fed me nourished me.

Still wounded and red, I will jump higher, For the flesh your compassion poisoned was served to me warm.

Fed. Nourished. Hunted. Feed me your flesh, then nourish me. Hunt yourself, then share all of yourself. Fed and nourished.

Wounded for me, you jump the highest. I will jump higher still.

utsstudentsassociation.org.au

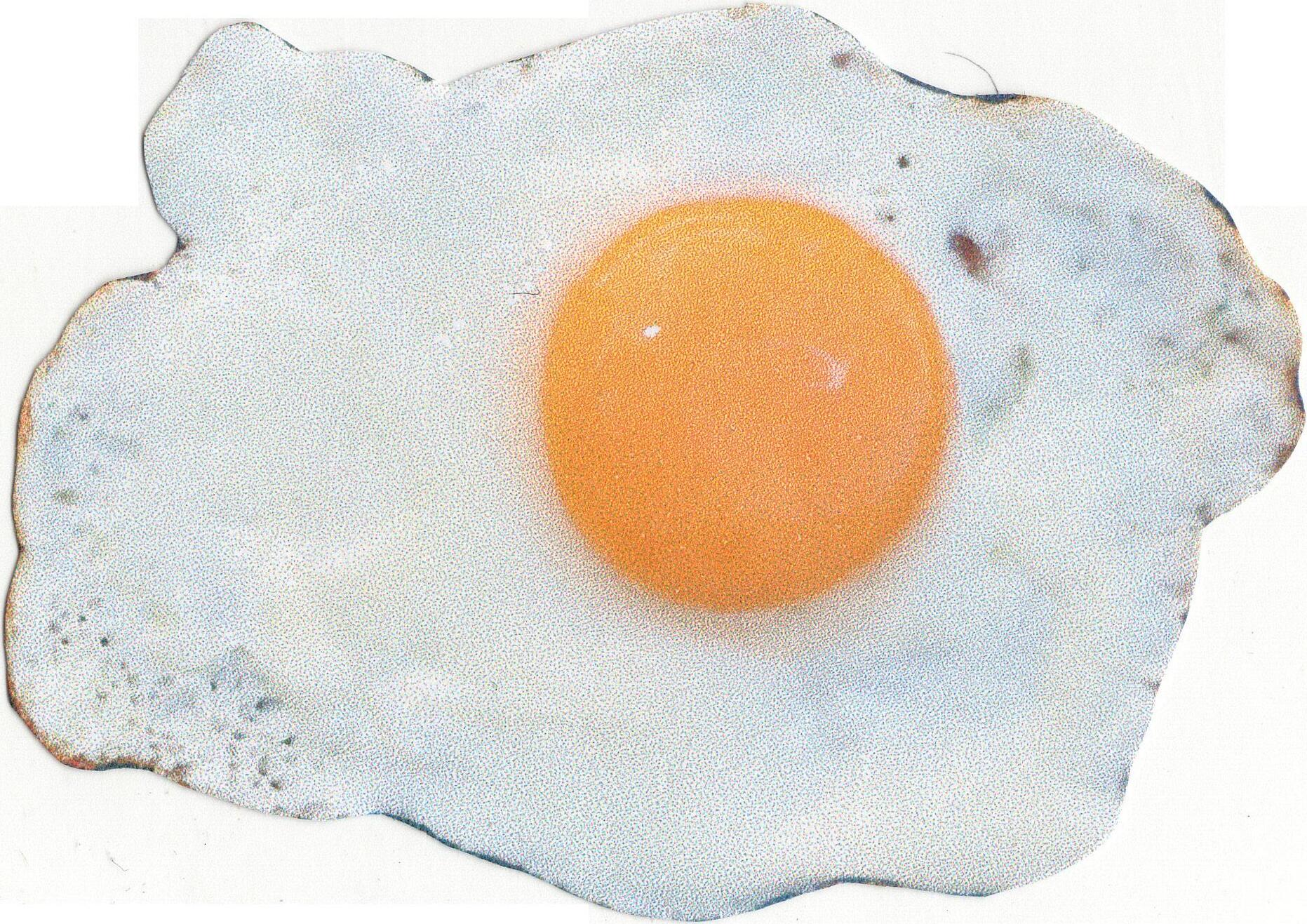

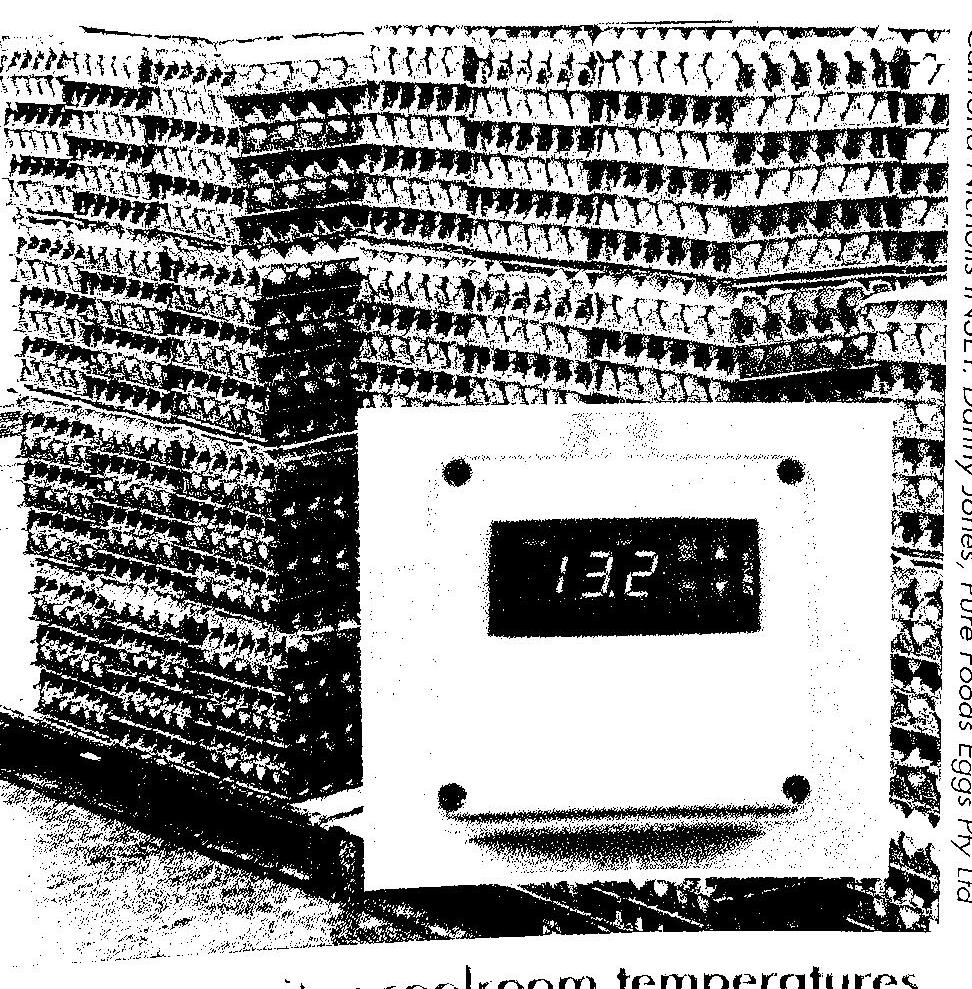

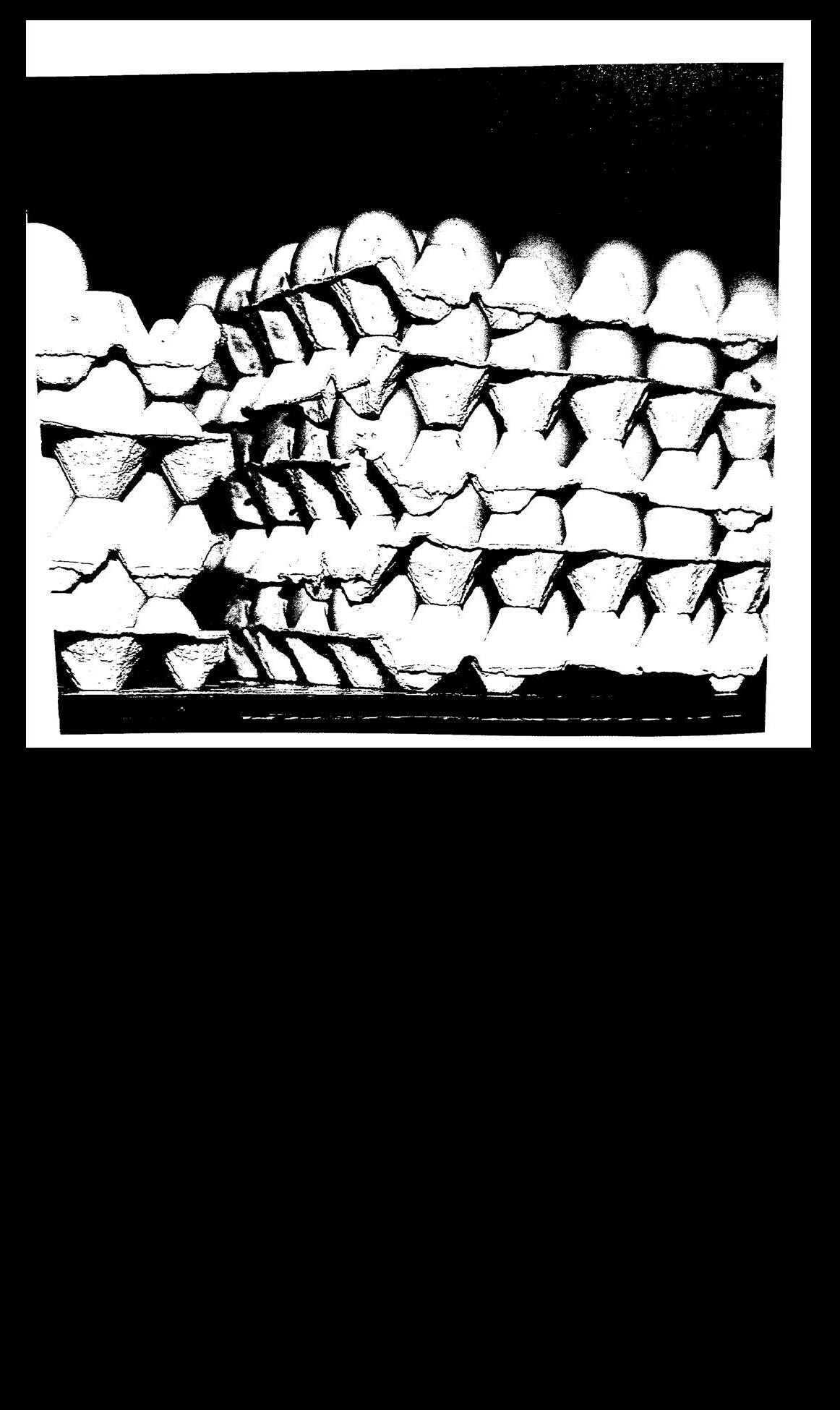

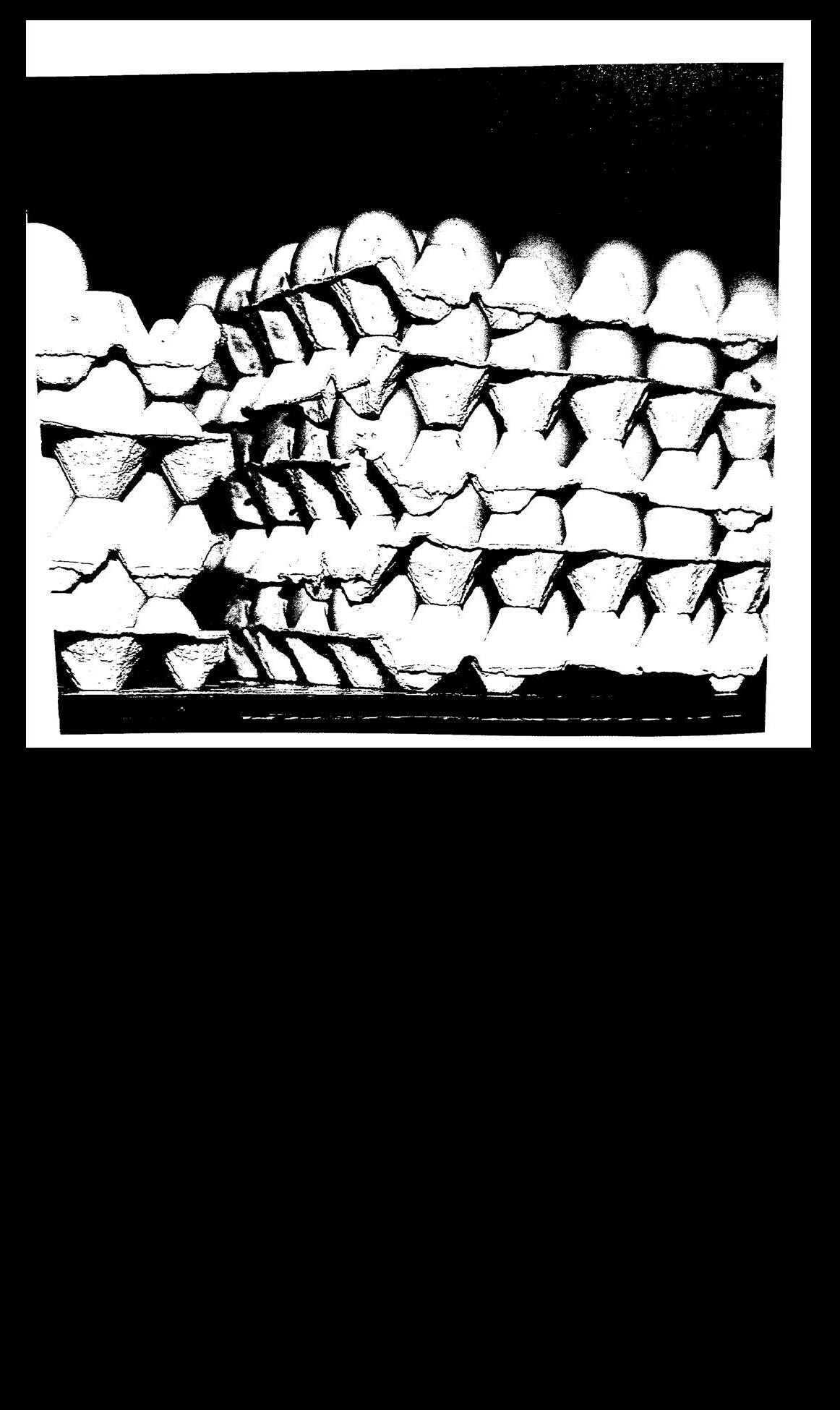

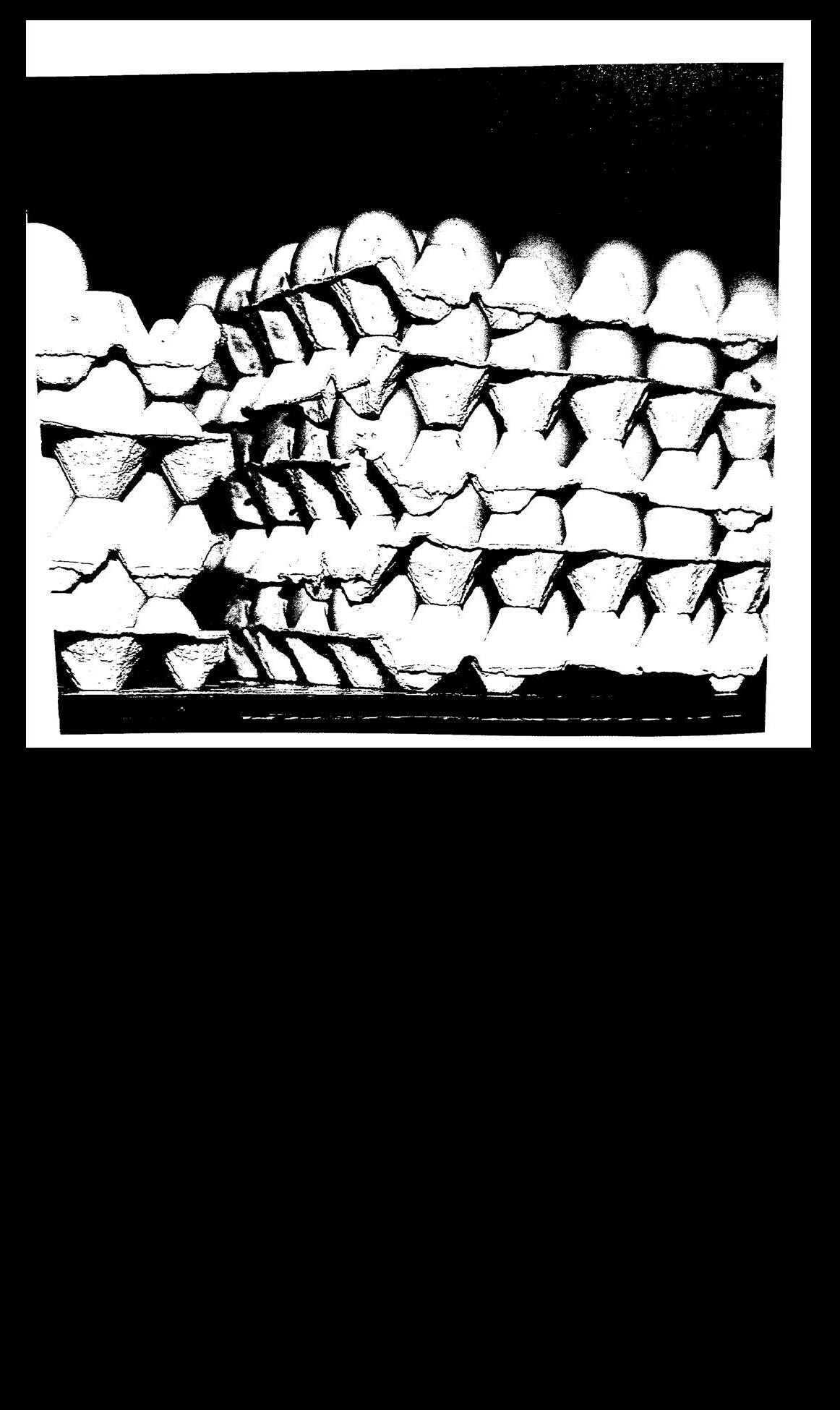

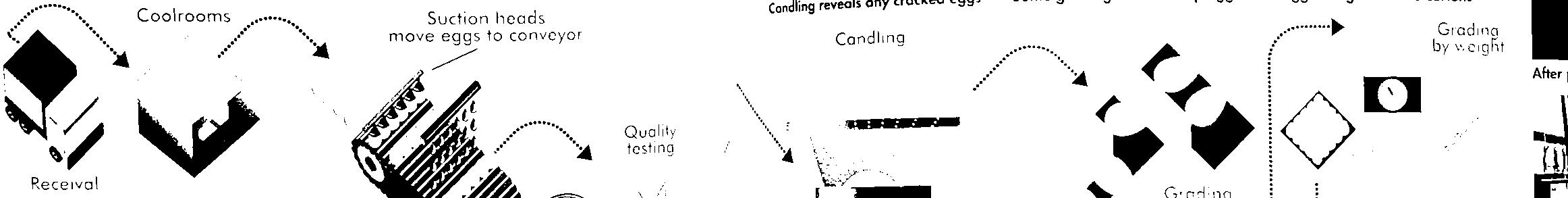

In the past year, UTS students have likely noticed bare shelves where it hurts the most. Today, the average UTS student eats their mi goreng with no fried egg and their scrambles have a higher proportion of milk. Students have relied on eggs as a cheap source of nutrition for forever, but this lifestyle has become a lifestyle of rations. If we continue down this path, Night-Owl will soon be all broth and no noodle, and Bluebird Brekkies mere bacon and no egg.

So, how did we get here?

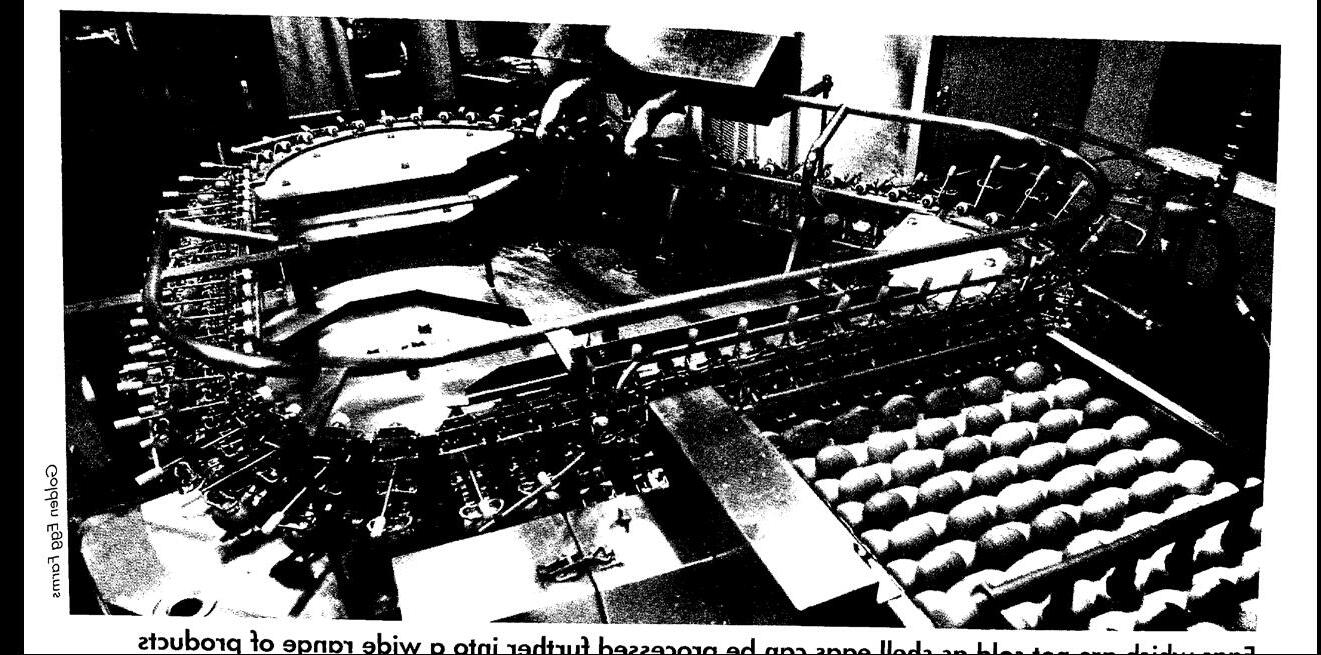

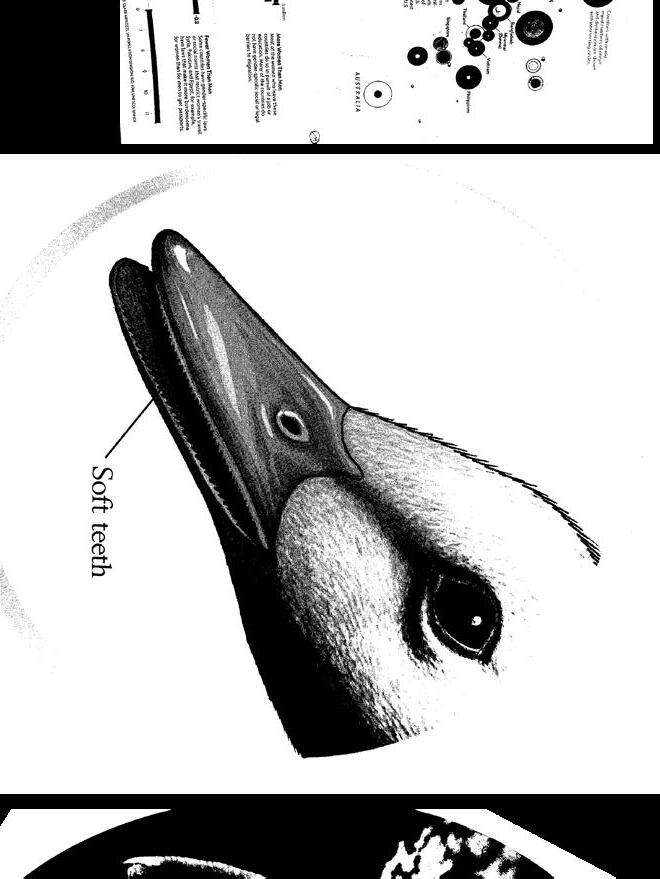

According to Mandy McKeesick of The Guardian, Australia’s ongoing egg scarcity may be attributed to growing consumer demand for free range googies.

A 2024 outbreak of the H7N8 strain of Avian influenza, known on the streets as bird flu, has spawned a crippling egg shortage on Australian shelves. The domestic outbreak, which hit farms in NSW and Victoria, is notably di erent from the global situation. Overseas, the more aggressive H5N1

Yay, a win!

Farmers in Australia employ a strategy of containment and depopulation to address such outbreaks. In June 2024, Avian Influenza was detected in two farms in the

this may not be the end of the story for Australian egg consumers. The real culprit: free-range farming.

She cites Greg Mills (qualification: he knows his eggs). Mills has worked as an industry adviser to the national poultry welfare code, as a university lecturer on egg production, as an on—farm consultant in free-range farm development, with the NSW Department of Primary Industries, and more. A brief glance at his LinkedIn profile compellingly validates his eggspertise.

So what does the messiah of egg production, Greg Mills, say about free—range farming? Put simply, if we continue on the slippery slope of the free-range egg takeover, the consumer’s decision will be between expensive eggs or no eggs at all. Now as a vegan I must admit the decision is easy for me.

However, eggs remain a staple for many a budding mind. In my deep dive into egg academia, I found a study on tertiary students suggesting that higher egg consumption led to healthier body composition because of increased protein intake. Considering the general stereotypes of uni students’ demonic diets, I could see the public health benefit of a couple of eggs, though chickpea flour may also do the trick.

So, for the sake of my UTS egg—eating cohort and my journalistic credibility I will entertain the concept of eggs, for now…

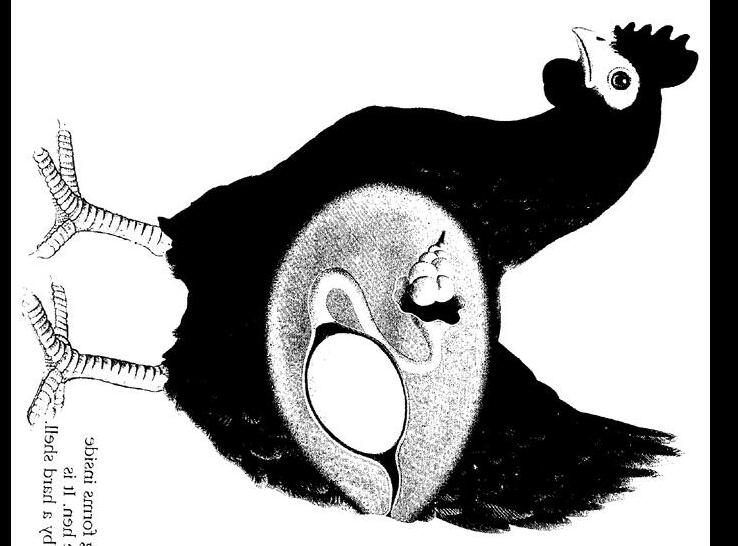

The crux of the theory is that the outdoor nature of freerange chickens increases susceptibility of contact with diseased wild-birds. This results in large-scale culling biosecurity measures, disrupting the delicate supply chain of eggs. Rebuilding the flocks is a long process, thus the current ongoing egg shortage despite disease elimination.

In a 2020 One Health article on Avian influenza in the Australian poultry industry, Angela Scott and her colleagues corroborate the findings of Mills. They found that a 25% change of chicken farms to free-range would increase the likelihood of an avian influenza outbreak by 6-7%.

So according to Greg Mills the choice is easy. For him, reintroduction of caged farming also does not seem to come at a cost. Greg Mills stated to the ABC that lower stocking density in sheds does not improve animal welfare. To me this seems like a pretty novel take, but let’s give Greg the egg a chance.

The idea is this: every time an egg-laying chicken is bred, the male o spring is mulched as they lack utility. Because chickens in cages do not die as often, farmers are not compelled to breed another chicken to fill their place. This then saves the male cockerel that must be killed to breed the new lady chicken. Thus, welfare! I’m not sure about your definition of welfare, but to me it has more to do with quality of life. It has less to do with whether my confinement may deter someone from mulching hypothetical male babies.

To return to the point, there seems to be an overriding belief that factory farms breed wellness. However, in the journal ‘Appetite’, Kristof Dhont and his colleagues suggest that there is a wilful disregard of factory farming’s culpability in zoonotic transmission of disease. Zoonotic transmission refers to where infectious disease is passed from animals to humans. Generally, this is a common occurrence in animal farms, and the starting point of most infectious diseases. Overcrowded conditions and production scale paired with feeding of antibiotics streamlines the spread of disease and of antimicrobial resistance.

So, if unlike Greg Mills we consider animal quality of life important and if factory farming may not necessarily safeguard against disease, what then is the decision for the every-day UTS egg consumer? I am not personally sure, but I’ll put forward some suggestions. The first is to accept expensive eggs. We can pursue the avenue of free-range farming and cross our fingers in hope that outbreaks are not as prolific as Mills suggests. Alternatively, we can impose some middle-ground regulations that reduce flock exposure to wild birds, treat water sources and restrict movement of people and equipment between farms. Or, we can all go vegan. Yet, this seems like an unlikely and

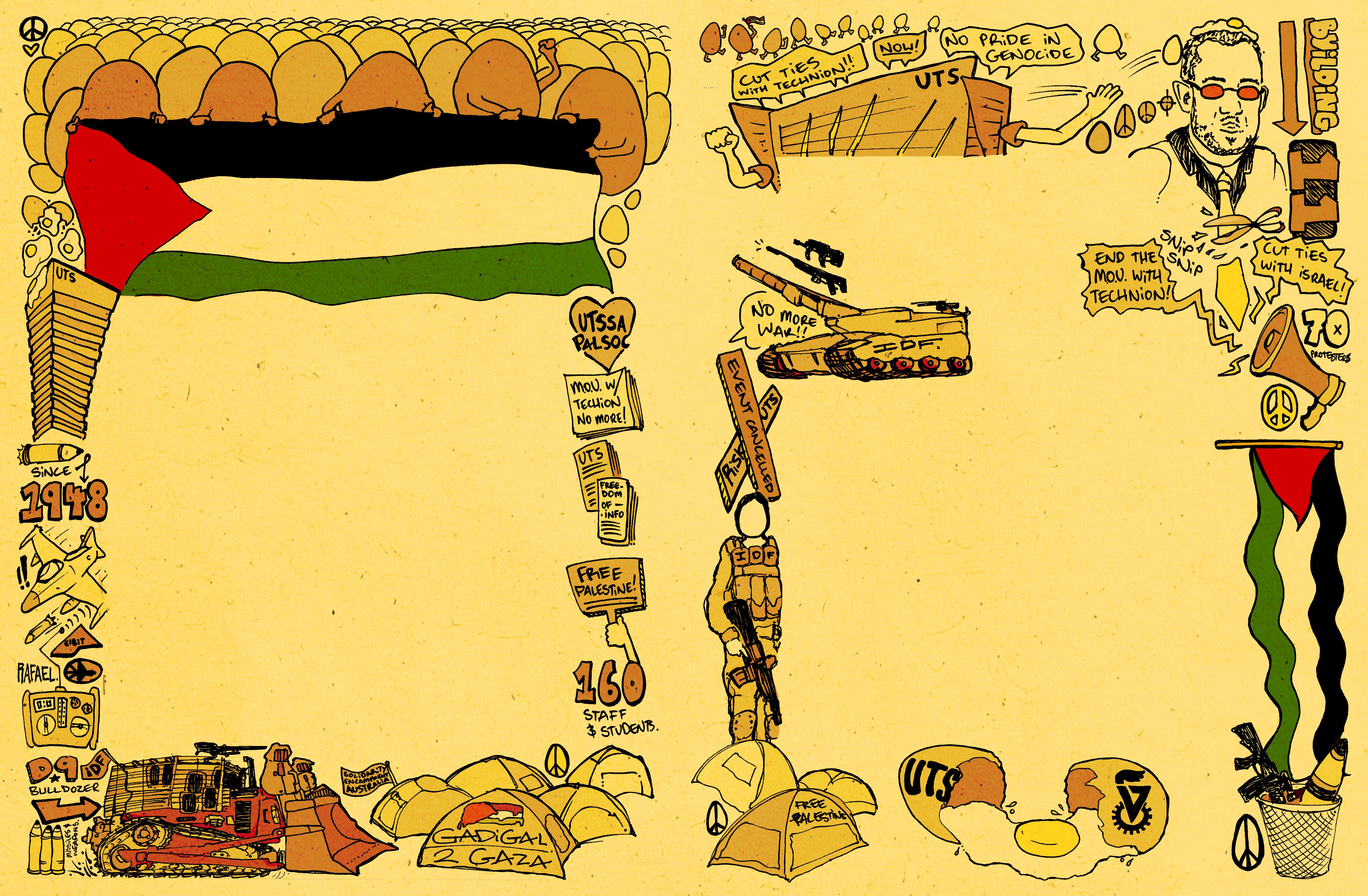

Words by Ali Al-Lami (he/him) @solidarityuts

Designed by Nate Halward Coloured by Mayela Dayeh

The University of Technology Sydney (UTS) has o icially ended its Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Israeli Institute of Technology, known as Technion, following nearly a year of sustained pressure, campaigning, and coordinated action by students and sta . This is an incredible win for The UTS Student Association (UTSSA), the UTS Palestine Society (Palsoc), Solidarity, and UTS Sta for Palestine, who all backed the campaign. And for the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) branch, who, in October 2024 voted for an academic boycott of Israel and to end Australian university cooperation with Israeli counterparts including Technion.

Technion has played a central role in Israel’s military and weapons development since 1948. It is deeply embedded within the Israeli arms industry, contributing to the ongoing genocide in Gaza by assisting weapons manufacturers such as Elbit and Rafael in developing military technologies. Among these is the remote-controlled D9 bulldozer, especially cruel in its use to demolish Palestinian homes in the occupied territories.

Since 2010, UTS had quietly maintained an MOU with Technion, facilitated by the Faculty of Science. The agreement supported student exchange programs, joint research, and the use of UTS facilities. It was due for renewal in June of 2025.

In September 2024, UTS Sta for Palestine obtained internal university documents through a Freedom of Information request, revealing the existence of the partnership. This disclosure occurred around the same time that Palestine solidarity encampments began appearing on campuses across Australia. Inspired by those actions, we began organising at UTS with one clear demand: to end all ties with Technion.

Technion was a key focus of the student and sta National Day of Action held on 23 October 2024.

Around 100 students and sta from the University of Sydney marched to join 60 others at UTS.

The protest entered the UTS Engineering building and occupied it for approximately 30 minutes, demanding the university cut all ties with Technion. The building includes the o ice of Professor Michael Blumenstein, a Technion Australia board member and UTS Pro Vice-Chancellor for Business Creation and Major Facilities.

In December, UTS sta and students helped organise a protest at the Technion 100th Anniversary Dinner in Sydney.

A second National Day of Action took place on 26 March this year, with 70 sta and students gathering at UTS to protest.

But the campaign for Palestine at UTS has faced continual repression. In October 2024, when a health science researcher at UTS tried to organise a seminar on “The Health Crisis in Gaza” the event was banned and the room booking cancelled due to a “risk assessment” with the sta member threatened with misconduct if he went ahead. Students responded by taking over the room to watch a Zoom meeting of the seminar at the scheduled time.

Yet, in April this year under the same risk management assessment, management allowed Israel IS, an organisation set up to promote the Israeli Defense Force, to bring former Israeli soldiers into UTS to speak. Students were told a speakout against this would be considered an unauthorised protest under campus policy and students could be issued with move on orders. The protest went ahead regardless.

Security tried to stop students leafleting for protests on several occasions, and lecture announcements about Palestine have also been prevented.

But even with all this suppression, the significance of this win for all UTS organisations campaigning for the cut is monumental. It follows campaigns that have successfully ended student exchange partnerships with the Hebrew University at University of WA, Ben Gurion University at Curtin Uni, and the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design at Sydney University.

We need to keep fighting to end all university ties with Israel. This kind of campaigning can help broaden support for Palestine on university campuses, and build support for broader demands for Albanese & federal powers to cut ties with Israel through sanctions on weapons exports and a ban on trade.

WORDS BY ADA KUMAR (SHE/HER)

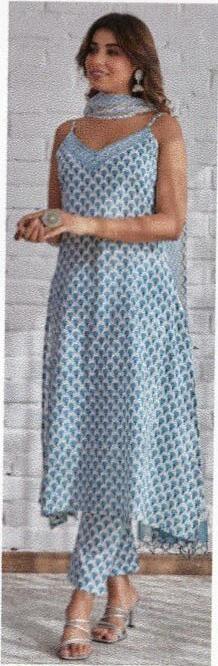

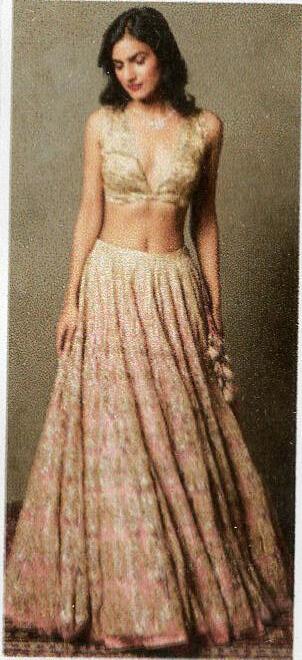

For many students, university is more than academics. It’s a space where cultural identity is constantly negotiated, reclaimed, or challenged. Cultural traditions that shaped home life often become sources of selfconsciousness or misunderstanding on campus. Meanwhile, many of these same traditions are commodified and popularised in mainstream student culture, stripped of context and true meaning.

Recognising the di erence between cultural appreciation and appropriation helps build stronger connections and fosters genuine inclusivity. Because you don’t have to look closely to see society’s best rebrand; practices that were called too ethnic now come neatly packaged as wellness and boho-chic. Turmeric, Amla hair oil, yoga, incense were all kept within the safe parameters of immigrant houses.

First and second generation immigrant children begging their mothers to pack sandwiches, not Parathas for school. Now this instinct rears its head in uni as well, hesitating to reheat my dahl rice in the common microwaves. I grew up walking on eggshells around my culture. Loving the vibrance on our trips back to family in India but reverting back to neutrals as the people on campus idolised. But as a glossy rebrand sweeps over Western pop culture, and culture is reduced to a colourless aesthetic, the generations before me contributing to the culture are left out of the conversation—yoga is now a billion— dollar industry (without any Yogis). After all, our culture was never fragile to begin with, it was simply deemed unprofitable in its original packaging. I suppose, scrambled eggs sell more than Bhurji.

South-Asian children growing up in Western society know how to manage their cultural identity well; the dichotomy between our home and outside life could’ve got us employed on Kanye West’s PR team. The same traditions and practices that were strategically made more digestible now exist in the mainstream, the shoulders carrying them praised for their innovative style. An egg, the yolk discarded, existing only as a shell, a practice without any substance behind it.

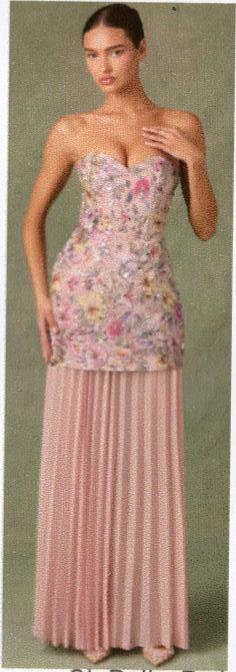

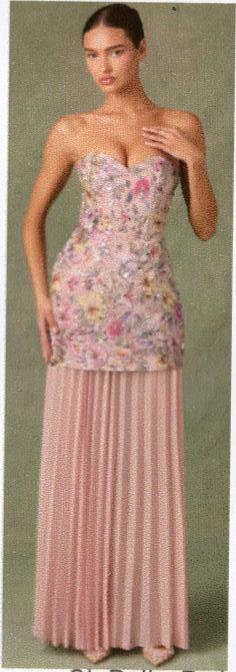

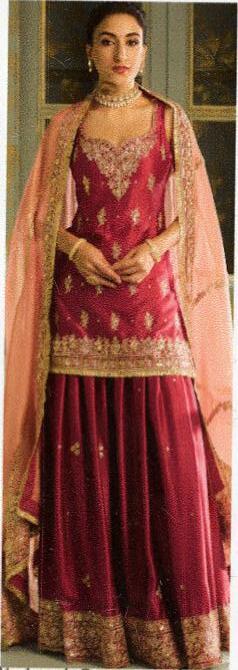

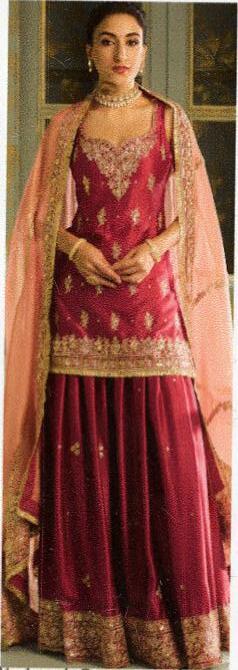

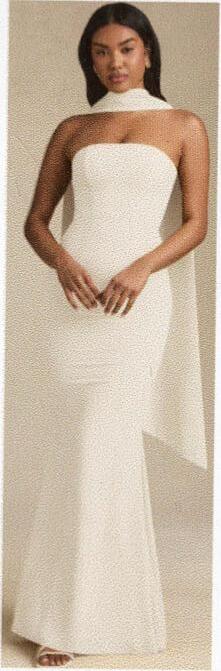

“It’s very

It’s a bit of an abnormal feeling. Of course, there is pride in seeing the culture I grew up with on runways and magazines. Look around and you’ll see it all over campus, kurtis that draw glances over the shoulders are considered ‘edgy’ and fashion forward (essentially a dress over pants for those not bothered to look it up). The jhumke I wear to class have made headway on quite a few Pinterest boards. However, there is bitterness in the question that follows; who gets to wear the culture and at what cost?

At the moment, the cost is of local labour, generations of artistry and children who were told their culture was “too much” growing up. Oh Polly, Reformation, Pepper mayo; these are some of many who have figured out that South Asian culture is much more palatable on those who aren’t.

After all, the clothing didn’t change, only who was wearing it. Bangles, jhumke, bindis, mehndi, all deemed ‘free spirited’, sported by the iconic Vanessa Hudgens— oh, and also your South Asian neighbour. This form of expression on brown skin remains foreign and exotic, or worse yet, performative as an attempt to ‘reclaim’ our culture.

Our exhaustion at these rebrands is innate and personal, rooted from being ‘othered’ when wearing the originals. The same generations that scrubbed away our coconut oil and undid our slick-back plaits in fear of perpetuating the stereotype of being ‘smelly’ are now seeing the same product sold for an exorbitant price as part of the ‘clean girl aesthetic’. The coconut oil stored in Mum’s old spice jar is now a uni-girl essential. The frustrations stem from exploitation, while watching these watered-down versions not achieve the craftsmanship required to rip o the original artistry. Mind you, this occurrence is not new. Cultural appropriation has long existed, long enough for the distinction between appreciation and appropriation to be understood.

I loved being able to dress up my friends of non-South-Asian background and share my culture, which they would reciprocate. At UTS, our cultural societies and initiatives play a vital role in this exchange. Whether it’s the Indian Student Society’s celebrations, the Equity, Inclusion and Respect policy, or smaller places where students can bring food, dance, and stories from home to share with others.

Cultural exchange is a significant celebratory aspect of a highly globalised world; there is so much beauty in celebrating each other’s cultures and practices. Appreciation allows for credit, context and celebration of the generations that have spent building this culture. Appropriation extracts and erases, it’s expression with amnesia.

For those of us who trimmed our identities just to fit in, the uncomfortable truth that our culture was only accepted once it was peeled away from who we actually are really cracked the shell wide open. On campus, this plays out in small but telling ways – like watching people sip on ‘Chai tea’, or excitedly sharing the “miraculous benefits” of Ayurveda as if it were a new discovery, all while treating it like a trendy wellness fad. Meanwhile, they’re studying globalisation and multiculturalism in lectures but then ask us, “no, but where are you really from?” when ‘South-West Sydney’ doesn’t satisfy their curiosity.

Being a student living this experience means navigating all these contradictions every day. We’re constantly negotiating how much of ourselves to show or hide, and learning how to reclaim spaces that were never designed with us in mind.

Detachment allows for consumption without actually associating with the culture or people themselves, while concurrently seeing the rise of South-Asian hate on social media platform comment sections.

BIT IRONIC THAT IN A MOVIE CALLED “WHITE CHICKS”, THE FORMAL ATTIRE TO THE WHITE PARTY IS A LEHENGA AND JHUMKE.

WHAT YOU ARE SEEING AT THE MOMENT IS A SUCCESSFUL REBRAND, NOT JUST SELLING THE PRODUCT BUT REWRITING THE STORY. THE GENERATIONS THAT CREATED, DEVELOPED AND ARE LIVING THE CULTURE ARE LEFT OUT. AGAIN.

As for first and second generation SouthAsian immigrants, the eggshells are now swept away and we no longer crack our identities to fit the mould.

If you ever called the food, people or practices smelly, yet post your Golden Latte, turmeric shots, or festival-chic look with a sense of accomplishment, sit in that discomfort.

Learn about where your daily practices come from and appreciate the people behind the culture you partake in. If you love the culture, love the people too. However, if this seems too big of a task and your jokes still echo the policies of White Australia, our culture’s not ‘too overwhelming’—your palate is simply too bland. I better not catch you in a two piece set lighting incense for your ‘manifestation ritual’.

DESIGN BY ARKIE THOMAS @AARKIIIVE

WORDS BY EMANIE SAMIRA DARWICHE (SHE/HER)

When I first read:

I didn’t cry, and I didn’t smile either. I just sat with them. Something in my chest felt tight. Like I had been holding my breath without realising it, and suddenly I was being invited to exhale. It wasn’t a dramatic moment. Just a quiet one. But sometimes those are the moments that stay.

Some days it feels close and grounding, like something I can rest in. Other days, it feels far away, buried under busyness, doubt, fear, or just the exhaustion of trying to exist in places that are not built for you. And truthfully, writing this, sharing this, is hard. It is di icult to admit that your Eman (faith) can feel unsteady. That your relationship with God can sometimes feel like you are whispering into a distance and hoping something echoes back. That even when you want to be close, your heart doesn’t always cooperate.

There is a quiet loneliness in being visibly Muslim in spaces that are secular by default and spiritual only when convenient. You grow tired of asking for prayer breaks, declining invites, and explaining your boundaries. The weight builds slowly at a glance, the pause before your name.

Before UTS, I studied at the University of Wollongong. On paper, everything seemed fine. But something vital was missing, and I didn’t yet have the language to explain it.

Ramadan came quickly, my first as a university student. Fasting wasn’t hard because of hunger, but because of the silence. The absence. The feeling of being unseen.

Each day, I sat alone on the train, clutching a date and a water bottle, breaking my fast as the train rattled on. I missed Dhuhr, Asr, and Maghrib. I missed the warmth and togetherness I had always linked to Ramadan. There was no one to pray with, no one to say, “I’ve felt that too”. The isolation was quiet and hard to name—a heaviness that followed me from station to station.

That was the first break. I was in a place I could not grow.

Later, during a visit to a friend at UNSW, she invited me to a sisters’ Halaqah. I almost didn’t go. I didn’t feel Muslim enough. But I went. We sat in a circle listening. It didn’t change everything, but it healed something. For one night, I didn’t feel alone. That memory became proof that a space like that could exist. Just not at UOW.

I found out the UOW MSA had not been active since 2019. I thought about starting it up again, but I did not have the tools or the guidance I was only in my first year. I was already holding too much.

When 7 October came, a line had been crossed. Not just in the world, but inside me.

I watched my peers shrink into silence. I saw student journalists question whether they could mention the word Palestine without consequences. I saw people afraid to grieve openly. The people who were loudest about inclusion fell painfully quiet.

I didn’t want to explain myself anymore. I didn’t want to compromise on my values, or filter my language so people would feel comfortable. I needed to leave a place that required me to fracture who I was just to exist.

I applied to UTS with one requirement. I didn’t care about prestige, programs, or the commute. I just needed to know if it had an MSA—a space where I wouldn’t carry my Islam alone.

Most of my classes as a communications student are in Building Three. Photography. Audio. Journalism. We learn how to tell stories there—but it’s not where my story at UTS began.

It began on Level Five, in the prayer room.

I paused at the door. For so long, I had prayed in stairwells and empty rooms, quickly and quietly, just to avoid questions. But this room was di erent. It welcomed my worship. For someone used to hiding, that meant everything.

I stepped in, laid down my mat, entered sujood, and cried. Not from sadness, but because I finally felt safe.

That was when I knew I made the right choice. A quiet moment. A return. Ramadan that year wasn’t easier, but it was di erent. I wasn’t alone.

I broke fast with others, prayed with sisters, and shared food and dua. For the first time in a while, I could focus on my connection with Allah.

It wasn’t perfect. I still struggled, but I was trying. And trying was enough.

At UTS, I didn’t have to shrink my faith. I could be fully Muslim.

But even in supportive spaces, the work of protecting your faith continues. Assumptions and quiet expectations still linger.

Being part of a magazine that I am so deeply proud to contribute to, has shown me how di icult it is to hold both your identity and your responsibility in creative spaces. I came in with a mission: to humanise Islam. To platform stories that reflected my community. To write with conviction, not compromise. But somewhere along the way,

I started making trade-o s. I started softening the edges of my voice. Not always by force. Sometimes just by fatigue. Sometimes out of fear of being labelled biased. Sometimes because I didn’t want to be seen as reactive, or emotional, or too much. So I let neutrality take the place of justice. I let the idea of professionalism slowly dilute my purpose. And I felt myself drift.

Slowly, quietly, and in ways that others didn’t notice. But I did.

That’s the hardest part of all of this. You can finally find your voice, and still struggle to use it.

Not because it is fragile, but because it holds something sacred inside. Something that is protected. Something that must be nurtured. Sometimes, we go through things that make us feel like we are breaking. But maybe that cracking is necessary. Maybe it’s not destruction—maybe it’s preparation.

Maybe it’s what allows us to become.

Your “egg” might look di erent from mine. It might be your first prayer after a long time. It might be sitting in a Halaqah quietly, listening. It might be deleting something that made you feel far from yourself. It might be setting a boundary. It might be whispering “Ya Allah, help me” at 3am.

Whatever it is—it counts. It matters. And it’s enough.

“Because with sincere faith, you will grow into the person you were always meant to be.”

You don’t need to have it all together to be worthy. You don’t need to speak loudly to be heard by Allah. You don’t need to be perfect to be loved. You just need to protect your yolk. To hold your sujood close. To remember that even in the moments where you feel spiritually lost, your Creator is not far.

You are not behind. You are not failing. You are becoming. He never forgets to teach you. Not even for a moment.

Find your UTS community

Meet like-minded people in safe and supportive spaces. Find out more at utsstudentsassociation. org.au/collectives

How did you two meet?

A) We met on Hinge. or B) I am a prince and I a m with my brother, in a wealthy foreign land, treating with a foreign king with a beautiful foreign wife. Soon our eyes meet, pupils locked, entangled. Then we run away and all the men who love her pursue, burning crop, waging war. Still, love is a sanctity that must be defended and so we battle for a decade. I also kill the demigod Achilles. or C) I am a prin ce, with my brother, with a wealthy foreign king, with a beautiful foreign wife... soon she has run away with me, with an empire in pursuit… Word gets around how I stole his woman, smuggled her over borders, refused to let her go, and caused a war that wastes away ten years and maims basically everyone I know. People start to not really like me. or may be also more realistically D) I smell sm oke waiting for the train. It takes me o the faded polish of my regular commute and up the escalator. I find myself o the street, on the second floor of a burning building... and you, you there too; your blonde hair lapped at by the flame but never catching. Cool under the pressure of the thinning air, in the process of submerging yourself in a claw-foot tub of boiling water (the temperature of hell; the Underworld). I ask you politely if you’d like a hand. Your skin scalds my arms as I carry you, step by step, out of the burning building. but meanwhile E) All men hate me on both sides of the gate, in that I grow weak for the love of you, and that I have caused ten years of doom to everyone for my self indulgence. You yourself call me a coward, scorn the reckless impulse that inched each limb of yours away from salvation and towards me, god-blessed but damned regardless.

Words By Mannix Williams Thomson (he/him) @mannixthomson

Design By Charli Krite @charlik.psd

J. F. G. H. I. and then F) I get thra shed around by your husband for a while before I am saved by the Goddess of love and lust and beauty and pleasure, Aphrodite, who has always had the hots for me. really in reality G) Trying t o impress you I compared us to Paris and Helen; star crossed lovers who took war for love, although most of what I knew of the story was from the movie Troy with Brad Pitt. Now that I’m a sophisticated writing student and much more better-read, I realise Paris is actually not a good person to be compared to. so… H) Maybe I am the warlike Achilles, you being Briseis, cooling my rage for only a moment. But again, that is more Troy than The Iliad . Also, either way, Achilles is not a great person to be compared to. Really, I’d want to be Hector, but then where are you? not to mansplai n but I) Fiction is a ll lies–lies that try to translate the chaos of reality into something as two dimensional as a piece of paper. I had played God. But no, even gods (lower case G) have to contend with each other; I had played Homer, and now I cannot unassign roles I’d blindly given, as the intergenerational, international echoes of Chinese (ancient Greek) whispers go uncontrollably beyond our intentions. al so it turns out tha t J) We a re influencers, Inner-West micro-influencers, or maybe Kardashian level influencers, and every time we tell our stories people listen. Women and men fluster, film execs commission, politicians dance our rhythms. Buildings burn, Paris and Helen are sanctified, statues are erected. Women leave families, men send arrows into the ankles of their enemies. Inaccuracies create digestibility. Our minds yearn for the simple sting of unrequited love, why overcomplicate? All we can do is lie to each other, build structures that mimic order, storify truth until it makes sense. so,

K. L.MNOPQRSTUVWXY. K) Appeal to desirability. Why don’t we make it a settler epic, I bet that’d sell: I am a leader of my ancestors, Windradyne, Wiradjuri warrior. I walk into Parramatta with PEACE written on my hat, an olive branch across my shoulders. Then the fictional pivot; I catch the eye of the wife of the governor, you, and you run away with me, and the war continues, and on and on. fuck L) We’ve gone t oo far in our web of lies, we’ve butchered too many stories. Book ink is bleeding, paper sticks together, histories are warring. MNO PQRSTUVWXY) We met, we told some lies, entertained each other. All you can do is let go of the beginning as it thrashes in your hand, there is no control of the story. so back to basics: Z) We talked a bit on Hinge. We got a drink. I chose the place because the courtyard got sun but by the time you arrived there was only a sliver left. We moved from place to place, ran into familiar faces, made up a few stories. We kissed and looked at the city. We walked for a while, took the bus, ate burgers. I stayed over but we didn’t make love. We shivered, both from the cold and the comfort of being close to each other. You fell asleep quickly but I was uncomfortable on your $90 mattress. The next day you made us toast and put heaps of sugar in the co ee and we laid in the sun and then you went to work. but there still is fiction in every word, really it went like

Words by Lana Ruman (she/her)

Designed by Nathan Halward Engineering, Identity

On the surface, the life of a STEM student at UTS might seem straightforward –morning lectures, late-night deadlines, and internships on the horizon. But just beneath this smooth exterior, many students carry delicate, fragile histories.

Shells fractured by war, colonisation, and generational trauma.

Like eggs with hairline cracks, we remain whole. Still here. Still showing up to class. But undeniably altered, fragile in ways not always visible to the eye.

For students of colour—especially those from families who migrated from regions shaped by conflict, famine, displacement or occupation—the STEM journey is far from neutral. It’s not just a path of academic rigour. It’s personal. It’s emotional. And it’s political in ways that most lecture slides won’t ever acknowledge.

We’re asked to innovate for the future, while our present is still shaped by the unresolved violence of the past. We’re told to think objectively while carrying the subjective realities of loss. And we’re encouraged to build—even rebuild— systems that have historically, and in many cases still, harm our people.

Engineering is often marketed as apolitical. The emphasis is on function, optimisation, and innovation, as if these concepts exist independently of history or power. But the reality is far less sterile.

Take Wernher von Braun, a figure often revered in aerospace circles. As a lead architect of NASA’s Saturn V rocket, he played a pivotal role in launching the Apollo 11 mission and securing the United States’ dominance in space exploration. What is frequently omitted from this celebration is his earlier history. Von Braun was a member of the Nazi SS and the developer of the V-2 ballistic missile, an early rocket weapon built using forced labour that killed thousands during World War II. After the war, the United States quietly absorbed him through Operation Paperclip, recruiting him to bolster American defence and aerospace superiority.

This is not a fringe anecdote. It is the spine of modern engineering history. And it reveals how scientific brilliance has often been welcomed, even glorified, regardless of the human cost.

In short, innovation without ethics isn’t progress. It’s just polished harm.

Today, the relationship between engineering and geopolitical violence continues, just under a di erent name and banner.

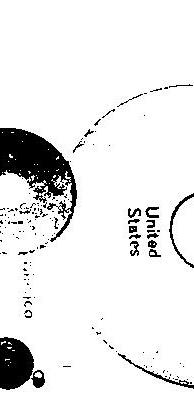

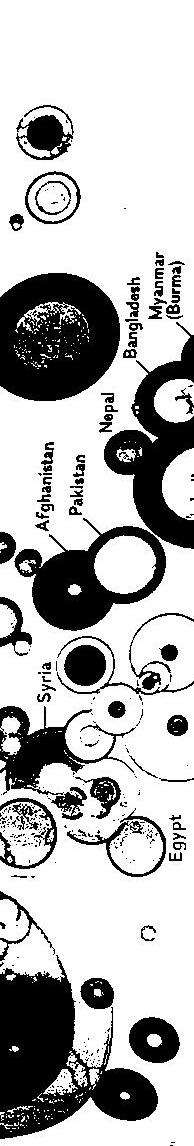

In Gaza, more than 35,000 people have been killed over the last two years. In Yemen, Sudan, Syria, and Libya, armed conflict persists with little Western scrutiny. Weapons used in these conflicts—drones, missiles, surveillance tools—are often manufactured, designed, or coded in the West. Many of those tools are built by people not much older than us. And in many cases, by graduates who once sat in university lecture halls not so di erent from ours.

Here at UTS, we are taught to design e icient systems, develop machinelearning models, and optimise code. But what’s often missing is the question: to what end? Are our skills used to build prosthetic limbs or target-locking systems? Are we improving energy infrastructure or developing control algorithms for military drones?

The same engineering principles that power life-saving technologies are also used in machinery designed to take life. That duality isn’t theoretical, it’s a lived contradiction for many of us.

It’s tempting to assume innocence by omission. “I’m not working for Raytheon, so I’m fine.” But the entanglement runs deeper.

Major tech companies, including Microsoft, Amazon, and Google have all signed contracts with military and intelligence agencies. Smaller startups often supply software and hardware for “dual-use” technologies, which are those with both civilian and military applications. Even the raw materials for our devices, cobalt and coltan, are extracted from countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, often through child labour and environmentally

So what happens when a child of Palestinian or Sudanese refugees is trained to work in the very systems that have displaced or harmed their communities? What does it mean to learn about “ethical engineering” in a classroom while your cousins live under drones built by the industry you’re trying to break into?

The shell cracks a little deeper. The internal contradiction sharpens.

Let’s be clear: this is not an argument against engineering. STEM is not the villain here. Breakthroughs in medical technology, climate resilience, and infrastructure are urgently needed. because we wanted to help. We wanted to rebuild what was broken, including in the places

But helping doesn’t mean pretending the system is neutral. Helping doesn’t mean silence.

Every country has a right to defend itself, but we need to ask: who defines “defence”? And who gets labelled the aggressor? Whose lives are protected by our technologies, and whose are deemed

At UTS, we pride ourselves on being a globally engaged, socially conscious university. But if we want to live up to those values, we need to foster conversations that connect STEM to ethics, history, and global responsibility.

We may not be able to change the entire system from our desks—but

▶ Ask questions in class: If something doesn’t sit right, raise it. Start conversations about the ethical applications of your work.

▶ Seek out ethical placements: Look for graduate roles or internships with companies working in climate tech, humanitarian aid, or ethical AI.

▶ Create community: Share resources. Talk openly with peers who understand the weight you carry. The cracks feel less isolating when we name them.

weight is often doubled: our labour is valued while our histories are ignored.

are cracked, yes—but not broken. And

Because in the end, the real question isn’t whether we can build. It’s we build—and who it’s for.

you are not entitled to her life because you had a small blow to your ego.

WORDS BY KIMIA NOJOUMIAN

@KIMIA_NOJOUMIAN (SHE/HER)

DESIGN BY ARKIE THOMAS NATHAN HALWARD

I began writing the article you’re now holding in March 2025. Since then, I have had to update the statistics of lives lost to femicide in 2025 almost every time I have reopened this document. The issue of femicide in Australia is not a case of a few bad eggs. It’s the result of systemic failures and a lack of accountability from the very institutions that are supposed to protect women and educate young men.

On 13 March 2025, Netflix released its hit series Adolescence, which follows the story of a 13-year-old boy, Jamie Miller, who murders his fellow female classmate, Katie Leonard. During its airtime, the series explored themes of misogyny, male rage, and toxic masculinity.

As a Media Arts and Production student here at UTS, I too was captivated by the show’s visual language and its ambitious single-shot format. But as a woman, I am horrified by the public’s response. Much of the discourse has centred on Jamie’s defence, with lines like “but he was bullied by her”, speaking exactly to the purpose of the series: You are not entitled to her life because you had a small blow to your ego.

is set in Britain, Australia endures the same pressing issue.

At the time this article was sent to Vertigo, 36 Australian women had already lost their lives to gender-based violence in 2025. I genuinely hope that by the time you’re reading this (after it’s been edited, designed, approved by the UTSSA, sent to print, and finally reached your hands) that number hasn’t changed. But for this writer’s peace of mind, could you check it for me, please?

Check the stats at: australianfemicidewatch.org/database

Adolescence underscores the critical role educational institutions play in addressing this ongoing crisis. Which provokes the question:

In the Age of Adolescence, what is UTS as an institution doing to help bring a stop to femicide in Australia?

It is important to note that UTS approaches the prevention and response to gender-based violence separately as per the Sexual Harm Prevention and Response Policy, which was first approved in December 2022, and most recently amended in September 2024.

Prevention is overseen by Respect. Now. Always. (RNA), UTS’s resident sexual violence prevention team and Steering Committee, established by the Provost in 2017 under the framework of the aforementioned policy. RNA is a mechanism for collaboration between the student body and the university, ensuring continuous growth for internal policies regarding the subject.

You, however, may know them as the stall at O’Day that gives out ice cream and condoms.

As a frequent volunteer, I have worked closely with the organisation and seen firsthand how it educates and empowers both the student body and faculty. Catharine Pruscino spearheaded the program in 2017, laying the foundation for the RNA that UTS knows today. At its conception, RNA was a radical response to the 2016 Change The Course: National Report on Sexual Assault and Harassment. I use the term “radical” as it was specifically designed to cater to the UTS student experience, taking into account the student voice, an uncommon notion at the time. I will note here that every tertiary-level institution was required to respond to the report and was responsible for how it was handled.

Response for the student body is provided by Student Services, UTS Counselling, two safety case workers, and the Government Support Unit.

In an interview with a victim-survivor who followed the proper channels for incident reporting at UTS, she stated that if she were to make a recommendation to a student who was in her position, it would be to “get a lawyer”. She also noted that UTS’s response services have had repeat incidents where victimsurvivors have been left in the dark regarding their cases, and have either relied on social capital for their voices to be heard or have fallen through the cracks.

It is encouraging to see that in recent years, the UTSSA has fought for and successfully campaigned for the introduction of “safety caseworkers” into the Student Services Unit. These are professionals who were intended to support, assist and help navigate students through the process of reporting gender based violence and sexual assault on campus, taking a case-by-case approach and maintaining confidentiality. Currently, there are two sta members in this role. Despite arguably improving the ‘trauma-informed’ capacity of the university to respond to sensitive matters, students have raised questions of whether these positions materially improve the navigation of the reporting process, or whether they simply act as glorified counsellors, rather than advocates for victim-survivors. However, what remains clear is that UTS can and should be doing more regarding its response to gender-based violence.

On 24 February 2024, the Education Minister, as part of the Action Plan Addressing Gender-based Violence in Higher Education, announced the implementation of a National Higher Education Code to Prevent and Respond to Gender-based Violence.

The code has 7 actions:

Establishing a National Student Ombudsman

Enhancing the oversight and accountability of student accommodation

Introducing a National Higher Education Code to Prevent and Respond to Gender-based Violence

Requiring higher education providers to embed a whole of organisation approach to prevent and respond to gender based violence

Identifying opportunities to ensure legislation, regulation and policies can prioritise victimsurvivor safety

data transparency and scrutiny

Its primary purpose is to create a national standard to prevent and respond to gender based violence due to universities’ current failed self-regulation.

All universities must begin reporting on their compliance from 1 January 2026. A current fear amongst academics in the space is that universities are treating the code as an upper threshold rather than baseline compliance. Mia Campbell, President of the UTS Students’ Association, has stated that at present, UTS is not aligned with key aspects of the code and that based on the pace of change in this area, it would take a “miracle” to reach this baseline before 1 January 2026.

Dr Rachel Bertram, co-leader of the Bystander Ally Project, also noted that this code is a minimum baseline when it comes to ensuring student and faculty safety on campus and risks a focus on short-term compliance measures above investment in meaningful and transformative change.. For instance, in cases of noncompliance, institutions will be liable to a “civil penalty” of 200 penalty units, which is equivalent to a fine of approximately $66,000 under the legislation. This raises a critical question: are universities more likely to implement meaningful internal reforms to improve safety, or simply absorb the fee?

We all hope for the former, but the unfortunate reality in most cases is the latter.

I was recently reminded of a quote by ABC reporter Annabel Crab, “If a man got killed by a shark every week, we’d probably arrange to have the ocean drained”.

Regularly reviewing of progress against the Action Plan.

Needless to say, all eyes are now on what UTS’s next move will be. How will UTS as an institution prioritise gender-based violence as a prevalent issue? It’s going to take more than fruit and ice cream to fix this issue; UTS needs significant internal reform to its response processes. We need sta and students to be held accountable for their actions, and for victim-survivors to feel safe on campus.

I’ll

Words by Roya Rezaie (she/her) @r07ya

Design by jpc_studio

The golden yolk of gently poached eggs spilling across a bed of crushed garlic and yoghurt.

Buttery sauce drizzled across the plate, infused with fiery swirls of Aleppo pepper. Flakes of dried mint melt on your tongue as you crunch into toasted bread drowning with sesame seeds.

“Personally, I like my eggs without wondering which Balkan country the recipe was stolen from”

ğ

“If we already normalise French restaurant terms like à la carte, surely, we can learn how to say “chill-burr”

“As if cooking wasn’t enough effort already, having to toe the line between cultural appreciation and appropriation can be daunting.”

Words By Alecia Lim

At three in the morning, sometime after Easter, chocolate eggs started rolling under my bedroom door. It started with one. Still sleepy-eyed and unaware, I shoot up from my bed, in disbelief that I could be woken up at this hour. And there lay an egg, still in motion, rolling around on the spot.

As unbelievable as it may sound, I was once taunted by a mouse.

Thinking I have fallen victim to a silly, childish prank, I get up and storm into my brother’s room.

“What are you doing?!”

The room is dark and there’s a lump hiding under the sheets. That’s some dedication.

“Huh?”

He grumbles and waves me o like he’s just woken up. I’m starting to think that maybe he has.

I’m back in bed, and just as I’ve started to doze o , I hear scratching. Another egg rolls under the door. This time, bits of the wrapping have been nibbled o .

This has to be some sick joke. As I get up to chuck the egg away, I pause, and decide to leave it there.

I’ll use it as bait.

At this point, I’m wide awake. I’m lying down, lights o , and staring at the ceiling. I’m haunted by this mouse. There might be more. They’re in my walls, watching and waiting, for the moment I fall asleep to scurry out and roam free.

I close my eyes, thinking it’ll heighten my other senses. I hear a slight movement, and I’m up in a second. By now, my eyes have adjusted to the dark and I see a tail dart away from the gap under the door. The egg is gone.

I stu a towel under the door and pretend to fall asleep until I do.

Design by Arkie Thomas

Mice are said to be born from the moisture of the earth, the soil, the dirt. They are inherently of dirt , they are dirty. Because of this, they are most commonly associated with disease—the bubonic plague being one of them.

In The Middle Ages, mice were carriers of Yersinia Pestis, a zoonotic bacterium that was responsible for the plague. Despite its fast—acting nature, the bacterium undergoes several stages before the plague can be spread e ectively. And, while rodents get the reputation as superspreaders, it really starts with a flea.

Yersinia Pestis is first ingested by a flea, where it finds its way to the digestive tract and multiplies until a blockage occurs. Now infected, the flea bites another host, and its bacilli are regurgitated, spreading through the host’s lymphatic system to the lymph nodes where they produce proteins that disrupt the body’s inflammatory response. By now, the host’s immune system is at an all—time low, and the bacilli know it. They take over the lymph nodes, causing them to swell up and form into buboes. While the bubonic plague was most known for its growth of buboes, other symptoms included: fever, chills, headaches, nausea and vomiting, body aches, and even delirium. If left untreated, the disease can progress to the septicemic stage, infecting the host’s bloodstream. At this stage, the plague kills almost 100 percent of those it infects. Eventually, it turned into a pandemic—known as the Black Death—which devastated Europe from the 14-16th centuries, killing upwards of 25 million people.

Although it seems like mice were to blame for all the death and turmoil that came from the Black Death, most people forget that they, too, were victims of the disease. During these times, mice developed similar symptoms and eventually met the same demise, with rodent populations su ering from high fatality rates.

Mice and humans are alike. They form intricate social bonds within their colonies and are known to be incredibly empathetic creatures. Beyond this, mice have about 85% of the genes that code for proteins in the human body, meaning that mice and humans develop in the same way—particularly during the embryotic stage! Mice are also prone to the same types of diseases as humans. It is because of this that they are often chosen as subjects of experimentation.

In 1968, at the National Institute of Mental Health, biologist John B. Calhoun conducted an experiment in which mice were supplied with an unlimited source of food, water, and bedding; they were given everything, except space. The Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice, otherwise known as Mouse Utopia , aimed to understand how social behaviour can change in overcrowded environments. In their habitat, the mice were protected from the threat of predators and exposure to disease. So, they started to breed, continuing until numbers reached a total of 2,200.

At this point, the utopia turned to hell.

“What is really catastrophic and where the real fear is, on a level where the mice and man are extremely similar.” John B. Calhoun, 1972

With the population at its peak and space at a minimum, the mice began to exhibit abnormal, destructive behaviours. Unable to escape, the juveniles and runts of the habitat became primary targets as males aggressively attempted to assert their dominance within the hierarchy. In their reign of terror, they would regularly attack others of their own volition and forcibly mate with other mice. Sometimes, violence would escalate to the point of cannibalism. Even the alpha males could not withstand the strain of limited space as they struggled to defend their territories from one another. And they soon grew tired. As a result, nests were overtaken, and mothers prematurely kicked out their young in stress. Deprived of guidance, the young failed to develop healthy social bonds, and most died out. The remaining adult mice kept to themselves, hiding away, obsessively and relentlessly grooming themselves. The social structure of the habitat was destroyed, and isolation ensued. Reproduction rates declined, and the population plummeted, failing to recover. By 1973, the population had fallen to zero.

Through Calhoun’s experiments, the concept of a “behavioural sink” was coined to describe the collapse in social behaviours due to overpopulation. In his work, he aimed to prove that social density was just as crucial a factor as physical density.

While Calhoun’s experiments pointed to the grim consequences of a congested future, he did not think humanity was doomed. He rejected the idea that human expansion would always lead to social dysfunction and ecological disaster. Instead, Calhoun thought of population density as a catalyst for innovation and social evolution. He saw humans as “positive animals” whose adaptability and capacity allowed for reimaginations into societies where they could live in healthy and sustainable urban populations.

However, as groundbreaking as Calhoun’s experiments were in the understanding of human behaviour, mice, as always, were reduced to mere subjects of experimentation. Despite being sentient beings, their existence was filled with su ering, and their su ering became an afterthought, overshadowed by the pursuit of scientific progress. They were stripped of complexity and care, and yet it was surprising when the experiment resulted the way it did. When their social structures collapsed, when they turned on one another, and when their population came to an inevitable end.

The experiment awakened something raw and primal in the mice, but they acted like animals because we treated them like animals. And though Calhoun viewed humans di erently, if we were subjected to the same environment, I don’t think we’d be any di erent.

I think back to the mouse that taunted me.

The morning after, we bait some catch and release traps with cheese—of course.

Nothing.

“Maybe try a chocolate egg,” my brother suggests.

I laugh but I try it anyway.

The next day when I go to check the trap, the egg is gone. In its place, a mouse scurries around the small, clear enclosure. And I see something alive. Not an experiment, or a metaphor, just a mouse.

Suddenly, I think of the Mouse Utopia. I think of the chaos, violence, and death that raged through the confined habitat. I think of their bodies being tossed away like any other piece of trash. I think of how they couldn’t even find peace, even after death.

And in this moment, the separation between human and mouse feels a little more blurred. I think, I wouldn’t wish that on anyone, or anything.

So, I set the mouse

So, when the egg cracks, it’s just a matter of courage and safety until a girl comes into her own.

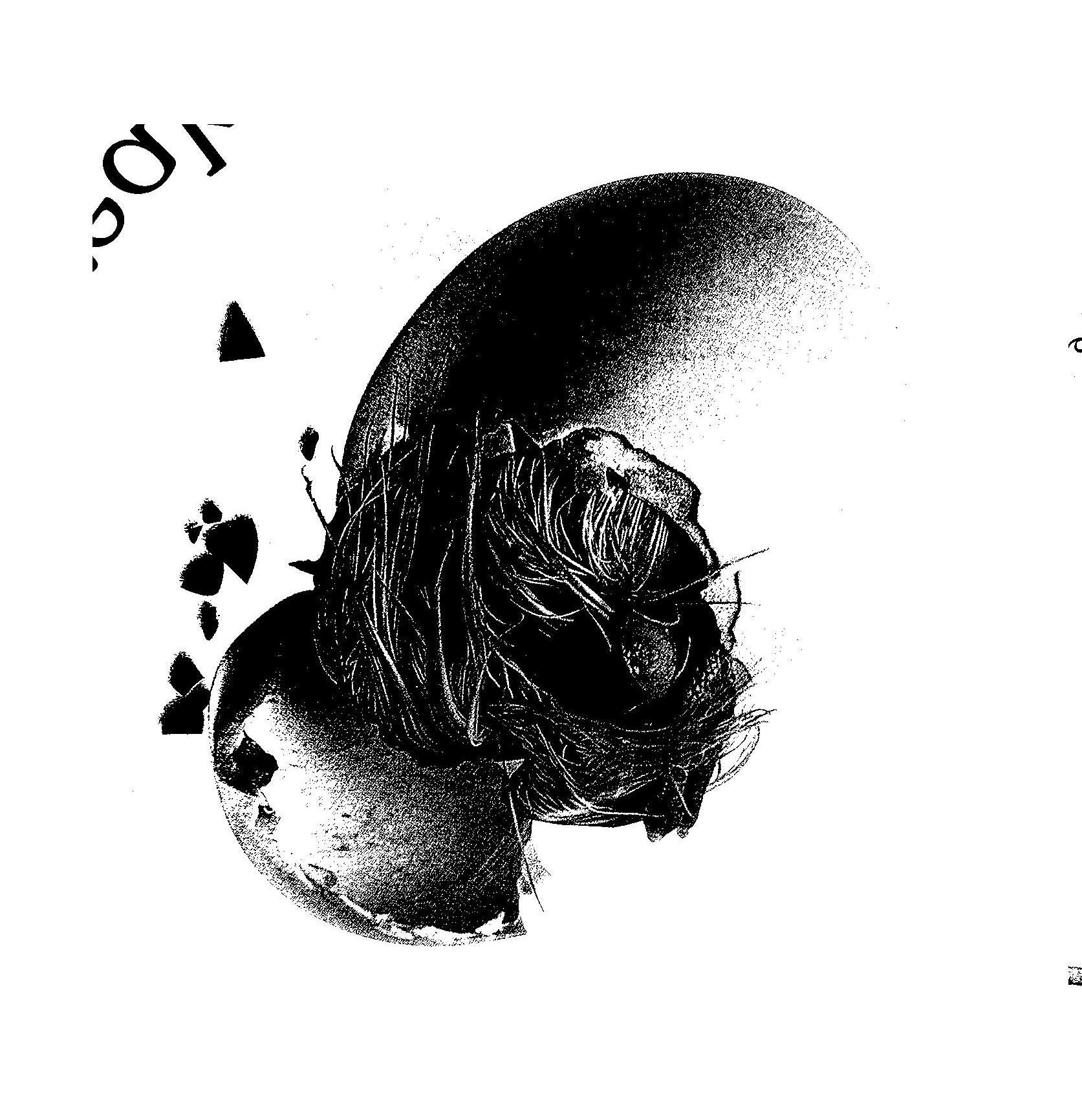

My egg was fragile from the beginning.

I tackled it gingerly, watching film after film trying to figure out how to be trans - like there was a ‘right way’ to hunt for: something to discover. The initial rupture was Julie Andrews starring in Victor/Victoria (1982), in all of her butch/ twink glory.

Her, a woman, pretending to be a man, pretending to be a drag queen, made my masculine qualities twinkle and shine, disconnecting the two polarised traits of masculine and feminine. I had cracked a lot more the first time I had watched The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), with Tim Curry salaciously belting Sweet Transvestite.

But what really cracked it for me was the realisation that I had always known.

It was a line of thinking similar to the one that came with my realisation of bisexuality. First, a sly humorous spark; then, a panic, an influx of religious guilt; and then, finally, acceptance.

The exploration of my identity through the idea of drag, and my continued understanding of the labels I once wore, can be used to understand the distinctions between the crossys, the sissies and the dolls.

, are your girls who genderbend for the kicks, whether it’s drag, discovery, or sex. The girls do it all for the illusion. This is what is important to note—generally speaking, it’s a surface-level feeling. Crossdressing, formerly called transvestitism, is when one wears the clothing of the opposite sex. It can get complicated when the crossys discover they are dolls through this exploration,

interested in things that are associated with women. From the small sample size of ‘research’ I’ve conducted myself, around 40% of people I’ve slept with have later come out as trans.

Whether it’s a hushed whisper, asking me to call these very straight, very masculine men, or these sissies, ‘girls,’ while we are in the secrecy of my bedroom, or their wanting a slip of oestrogen from my case: I raise an eyebrow.

I chalk it down to the power of the doll, in stride.

These are your girls! Oestrogenated, transgendered, and gorgeous. Girls like us come in all different ways, and from all different places. Trans girls, or the , are hailed as the trailblazers for the queer community, namely the Black, and the Indigenous, trans women of colour—those who have been doing it for time immemorial.

The main difference between the dolls, the crossies, and the sissies is that the dolls’ trans identity is inextricable from ourselves and our spirits. It’s more than clothes and medication and movies; it’s growing so close to yourself with love, to turn a magnifying glass around and reinvent yourself to survive in a world that was not built for us.

Upon exploring each facet of my gender journey, I find that I hatch into a new version of myself each day. That the ferocity of self-love and strength is found in splitting the trepidation of self-doubt and swimming in the possibility of rediscovering myself over and over and over again.

Words by Gamya Shastry (she/her) @gamya.28

BURNOUT DOESN’T FEEL DRAMATIC. IT FEELS ... OVER-EASY.

When you’re a university student, burnout is normalised, joked about, even expected. But for students from immigrant families, it runs deeper than late-night deadlines or juggling too many shifts. It’s laced with guilt, cultural expectations, and the weight of succeeding not just for yourself, but for your entire family.

According to a 2023 Orygen report, students from migrant and refugee backgrounds reported significantly higher rates of psychological distress, yet were less likely to access support services. For many, there’s an internalised belief that struggle is normal.

Further research from a 2021 study published in found that immigrant youths, particularly those from low-income households, often hold extremely high academic aspirations, shaped largely through family expectations. While this can drive achievement, it also creates a powerful source of pressure. The study noted that even if students wanted to succeed, systemic barriers and emotional fatigue made it difficult to follow through, especially when asking for help feels like admitting weakness.

This pressure is compounded by what psychologists call intergenerational expectation—the belief that children must “repay” their family’s sacrifices through academic and career success.

For many students from immigrant backgrounds, education isn’t just a personal milestone: it’s a legacy. One you are expected to carry carefully, no cracks allowed.

Burnout isn’t always loud. It doesn’t scream. It hums quietly under everything, like the fridge. You don’t notice it, until it stops. You still submit assignments. You still show up to class. But inside, you’re running on empty, you’re scrambled and scraping the pan for whatever energy is left. You forget who you are outside of achievement, and when you finally take a break, you feel guilty.

This pressure isn’t uncommon. In fact, a 2022 ReachOut survey found that 72% of young Australians feel the pressure to succeed. For many students from immigrant households, that pressure is rarely just personal, but rather reinforced by cultural narratives, family sacrifice, and the burden of being “the dream”.

Even if you know you’re lucky and privileged, guilt is a shell that doesn’t crack cleanly. It lodges in your throat and cuts you into pieces. That’s why, despite all these pent up emotions, students push through and study. But pushing through doesn’t mean you’re not overwhelmed. You tell yourself to be strong like your parents were forgetting that strength without rest eventually breaks you.

At UTS, free counselling is available to all students. The team supports everything from study stress and anxiety, to more complex personal struggles.

If sitting down with someone face-to-face feels daunting, there’s also TalkCampus, a 24/7 peer-support app available to all UTS students. It allows you to talk anonymously with students around the world who truly understand what you’re going through.

Despite these services, many students, especially those from cultures where mental health isn’t openly discussed, hesitate to reach out. For some, asking for help feels like admitting failure. For others, it’s simply not how they were raised.

The reality is, no amount of gratitude can protect you from exhaustion. And pain isn’t a competition. Just because someone else carried fire doesn’t mean you’re not burning.

Eggs are fragile, but they’re also full of potential. They can be anything from your favourite breakfast to the beginning of the circle of life.

24/7 anonymous peer support. Download and register with your UTS student email for full access.

Written by Mila Fisher (she/her)

Designed by Nathan Halward

Tech can feel overwhelming, especially when you feel like you don’t belong. I’ve been there. As a cybersecurity student, I’ve learned to look past the initial assumptions. It’s not just about hacking; it’s about protecting people and sticking with it when things get tough (and trust me, things get tough). So if you’re starting your journey now, here’s the lowdown on what I’ve figured out so far.

If you’re here, there’s a reason for it.

Every opportunity I have had comes with that little whisper in the back of my head that says “this was just luck.” Even when I know, deep down, that I have put in the e ort, taken the initiative, asked questions, and stayed up late trying to figure things out.

Imposter syndrome, I’ve realised, often stems from a quiet disbelief in your own ability, even when you’ve clearly earned your place. It’s something that does not always go away with time or achievement. Sometimes, in fact, the more you grow, the louder the voice gets, like you are just getting better at pretending. It took me a while to realise that this feeling is incredibly common, especially in the world of tech. In a space that moves fast and celebrates brilliance, it’s all too easy to forget that you deserve to be here too.

Imposter syndrome, while uncomfortable, can fuel meaningful growth. If you are questioning yourself, it probably means you care. It means you want to do a good job. You are open to learning, you seek feedback, you are trying and that is more powerful than you think.

I have had to remind myself that I deserve to be here and that I have worked hard. That no one starts o knowing everything and that everyone is learning, all the time. People have di erent strengths and ways of thinking, and you do not need to be good at everything to be considered valuable.

So when that voice of doubt creeps in, it’s easier said than done but I try not to shut it out. I listen, then I answer it. Yes, this is new. Yes, it is hard. But I am here, and I will figure it out.

So if you are feeling like you do not belong, please know this, you are not alone. The fact that you care, that you are reflecting, that you are showing up anyway, already says so much about who you are becoming. Keep going. The industry needs people like you.

Cybersec does not have to be you and your code against the world.

While cybersecurity can be an enjoyable technical puzzle, what draws me in is the human impact—knowing that the work we do protects real people from real harm. I care deeply about the stories of individuals and organisations who fall victim to phishing, identity theft, ransomware, and social engineering. This desire to help others is what led me into this field, alongside a love for technology and the challenge of keeping the shell unbroken in an increasingly fragile digital world.

I do enjoy the technical side, and I have learnt so much from hands-on labs, tools and capture the flag challenges.

But the part I think more students should hear about is governance, risk and compliance (GRC). It’s not as flashy, and often doesn’t get much airtime at university. Most discussions centre around penetration testing or security operations centre roles. But GRC is the backbone of a strong security program.

It is what connects people, processes, and policies to reduce risk and build long term resilience. It is also an area where empathy, leadership, and proactive planning are just as important as technical skills. Too often, the less technical roles are undervalued, yet they’re the glue that holds the entire system together. Where would we be without risk assessments, policy frameworks, compliance audits or proper incident response planning?

GRC roles ask us to zoom out and look at the bigger picture. Instead of just reacting to incidents, you’re implementing safeguards that stop them from happening in the first place. You translate complex technical risks into language that stakeholders can understand and act on. You’re asking the hard questions, what could go wrong? Who does this a ect? How do we recover? Then building the structures to answer them. I would consider it strategic and people focused work that underpins every security control, every alert and every investigation. And while it may not always make headlines, it is often the reason a company stays out of them.

Trying to land a graduate program in the tech world? Welcome to the ultimate endurance test.

The first thing a lot of people don’t realise is that applications come out almost a full year beforehand, so you need to apply early. For example I graduate at the end of 2025 (touch wood), but I began applying in March 2025 for a job in February 2026.

If you miss that window, you might have to wait an entire year (2027!) for the next round of grad roles and for

So, where do you start? First, hit up GradConnection. It’s a goldmine for finding open programs. Most applications follow a similar pattern: you’ll start by submitting a resume (keep it plain and professional). If you’re shortlisted, you’ll get invited to complete a psychometric assessment, often within 48 hours—no exceptions. These tend to land right when you’ve got a major assignment due or a late shift at work. No pressure, right? The tests can take over an hour, covering maths, logic, verbal reasoning, and emotional intelligence. Ignore the “there’s no right or wrong answer” messaging, trust me, there is. I recommend practicing on sites like the Psychometric Institute so you’re not blindsided by the style of questions.

Next comes the assessment centre: a 2–4 hour marathon where the company observes how you interact, problemsolve, and present. From the moment you walk in, you’re being assessed. Are you too quiet? Too dominant? Do you include others? Do you have solid ideas?

Then comes the one-on-one interview, where you’ll need to show that you’ve actually researched the company. Practice common questions like “What’s your biggest weakness?” or “Describe a time you handled conflict.” Use the STAR method as that’s what they expect, and yes, it takes practice (at least it did for me).

Here’s a tip: keep an Excel spreadsheet (I loveeeee a good spreadsheet) of every place you’ve applied, which team, and what stage you’re at. If someone calls you two months later asking, “Why did you apply to our cloud infrastructure team?” you’ll want to at least sound like you remember.

And finally don’t get discouraged. I didn’t land a summer internship, and that felt rough (like really rough). But I kept applying, kept practicing, and now I have multiple graduate o ers. The process is tough, but it’s survivable and honestly worth it when you crack your first o er.

And if you’re still waiting, still applying, still unsure, that’s okay. This process doesn’t define your value, and it definitely doesn’t mean you’re not good enough.The grad process might make you doubt yourself. But it doesn’t mean you don’t belong.

I hope more students see that cybersecurity has so many di erent avenues, all of them critical to achieving the same goal: protecting people and driving positive change. And yes, sometimes, it is also about knowing when it is time to wear the hoodie. But choosing a path you care about doesn’t mean the journey is always smooth. I’ve learnt that the hard way, too.

Speak to our Student Advocacy Officers for independent and confidential advice.

Book an appointment OR Drop in

Tuesdays, 10:00am-12:00pm

https://zoom.uts.edu.au/j/89791010171

Thursdays, 12:00pm-2:00pm https://utsmeet.zoom.us/j/12028173

UTSSA office

UTS Tower Building, Level 3, Room 22 (02) 9514 1155

utsstudentsassociation.org.au/advocacy

This month has been one of the busiest and most challenging of the year so far, with major work continuing across campaigns for justice for Palestine, reforming UTS’s response to sexual violence, and defending the integrity of education at our university

On sexual violence reforms, I’ve been pressing UTS to address serious inconsistencies in its reporting of sexual harm. Current data is filled with contradictions, making it impossible to track outcomes or assess whether survivors are receiving support. I’ve called for a standardised reporting system that tracks timelines, referral pathways, outcomes, and demographic trends. At the same time, I’ve been working with the National Student Ombudsman to progress a systemic complaint against UTS for failing to implement past review recommendations. This accountability work is di icult but crucial, and I’ll continue pushing until victim survivors see real change.

On Palestine, beyond organising the August 7 National Day of Action at UTS, I’ve responded to troubling findings from an external review of campus protests earlier this year. The UTSSA has raised serious concerns about procedural fairness, inconsistent treatment of political expression, and the chilling e ect on student activism. We remain clear: freedom of expression, including for Palestine, must be protected on our campus.

Beyond these campaigns, I’m excited that the UTSSA has launched a new food security partnership with OzHarvest, bringing free hot lunches to students on campus starting August 15. I’ve also been in contact with sta and other student leaders across NSW to build momentum on transport concessions for part-time and international students, an issue that students have been fighting for decades. The state-wide petition for expanding transport concessions has already gathered thousands of signatures—you can add your name and support the campaign using the QR code.

Finally, the UTSSA is deeply concerned by the Operational Sustainability Initiative (OSI) and the suspension of 146 courses announced by UTS. While management frames these as “temporary,” the reality is that decisions of this scale have been made with little transparency and without genuine consultation with the sta and students most a ected. Academic governance processes exist to ensure our community has a voice in shaping the future of education at UTS. Students and sta deserve clarity, accountability, and meaningful engagement, not unilateral announcements and after-the-fact briefings. We will continue to call for proper consultation, transparency, and protection of disciplines that are core to UTS’s identity and mission. I’ve spoken publicly about this decision as both a President and a Physics student (one of the majors that UTS is suspending!) and I’ll continue to fight for the future of these disciplines.

Arkie Thomas @aaarkiive

Nathan Halward @rgb_rex

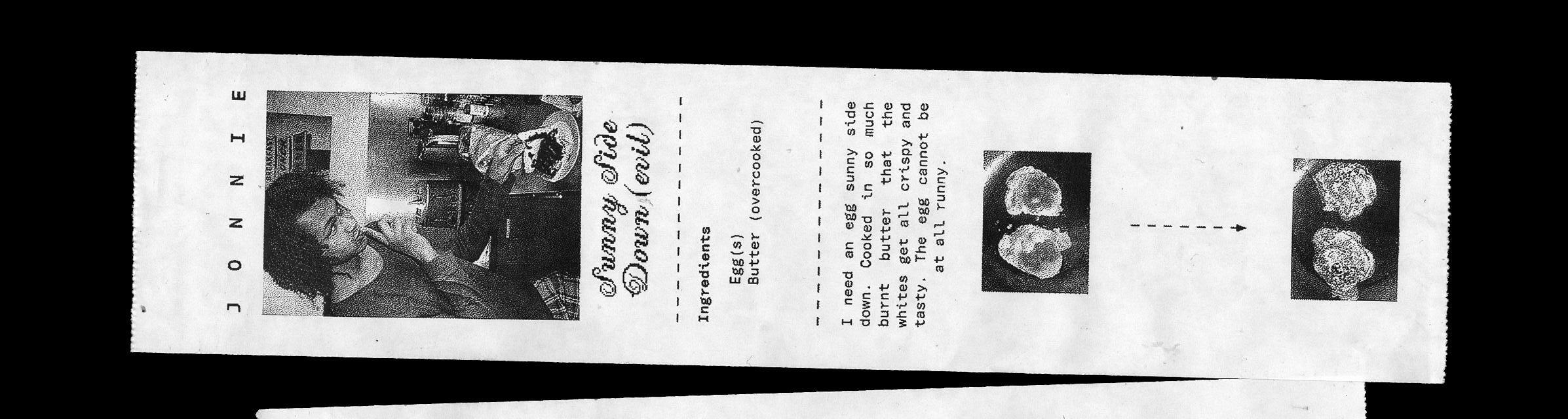

Jonnie Jock @jonniefuckingjock

Charli Krite @charlik.psd

Daniel Sjorgen @desjgnss

James Campbell @jpc.studio_

Ada @ada_k_11Kumar

Amir Farrag @amirfarrag03

Alecia Lim @alecia.lim

Asha @ashadeluxeJohnston

Gamya @gamya.28Shastry

Roya @ro7yaRezaie

Mila LinkedInFisher — Mila Fisher

Mannix Williams @mannixthomsonThomson

Kimia Nojoumian @kimia_nojoumian

Emanie Samira Darwiche

Lana Ruman

Ali Al—Lami @solidarityuts

Jet McCarthy @jetmccarthyy

Mariam Yassine @mariam.yassne

Mayela Dayeh @mayeladay

16TH

Vote between the 14th—16th of October to have your opinion heard.