“I was employed at UTD from its inception until I retired in 1986. During that period I became aware that one day UTD would become a huge asset to the community if private citizens would contribute to its growth. When I decided to rethink the content of my will two years ago, a commitment to UTD was placed at the top of the list. This resulted in designating funding for a future Elizabeth Exley Hodge Endowment. At the same time I decided to immediately begin supporting the publication of a UTD undergraduate research journal, at the suggestion of Undergraduate Dean Sheila Gutierrez de Pineres and Robert Marsh, Senior Lecturer in Biology. In March 2012 this journal, The Exley, debuted.”

— Libby Hodge

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL

VOLUME 6 SPRING 2024

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS

THE

In Memory of

Libby Hodge

In the spring of 2011, Ms. Elizabeth Exley Hodge made a generous donation to support the publication of UT Dallas’ first interdisciplinary undergraduate research journal. Hodge’s maiden name of Exley represents the rich history of her family. The surname Exley, originally Ecclesley, dates to 1245 and means “church fields.” Her great-great-grandfather’s birthplace is now known as Exley Hall in Yorkshire, England. This journal was named The Exley to show the University’s appreciation of Hodge’s support for undergraduate research.

About The Exley The Exley Name

Jessica Murphy Dean of Undergraduate Education

Jessica Murphy Dean of Undergraduate Education

Dear Readers,

Welcome to the Sixth issue of The Exley, UT Dallas’ interdisciplinary undergraduate research journal. This issue is dedicated to Ms. Elizabeth Exley Hodge, who was a highly-valued employee at UT Dallas for nineteen years, and continued her contributions by graciously supporting this forum for undergraduate students to share their research and creative work. Please read the lovely tribute to Ms. Hodge written by Robert and Mary Marsh that is featured in this issue.

The research and creative pieces in the Sixth issue of The Exley coalesce around the theme of growth through change, and it is our hope that you will enjoy and learn from them. Student research articles in this issue looks into potential medical interventions, such as possible treatments for Perthes disease, the importance of exercise for adolescent scoliosis patients, and the relationship between gut bacteria and certain antibiotics. They study our communities, both online communities engaging with vaccination, and local communities encountering water contamination. They also give us insights into our world through a study of the twentieth-century architect, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, and one of pure mathematics. Among the creative work here by students, you will find poetry, painting, abstract photography, animated film, and mixed media work. From exploring the growth of young adults to an investigation of knowledge, the students’ creative work will affect you intellectually and emotionally.

The works published in The Exley reflect the dedication of the authors and their faculty research mentors. As a highly selective undergraduate research journal, The Exley encourages students to work closely with faculty research mentors prior to the submission process. The works you will read here are usually the result of multiple semesters of investigation and writing by the student authors. The Exley would not be possible without the careful work of its faculty and student reviewers and editorial team. Each submission receives careful attention from the staff who help students prepare the pieces for consideration and from the faculty who review for form and content.

The Office of Undergraduate Education is very grateful for Ms. Hodge’s generosity and commitment to the University’s continued excellence in undergraduate education and research through a legacy gift that has endowed The Exley into perpetuity.

Sincerely,

Jessica C. Murphy, PhD Dean

Elizabeth Exley Hodge Biography

Elizabeth Exley Hodge was born in a small farming community in Worcester County, Maryland in 1920. She was one of 11 children of Lola Marie Watson and John O. Exley, rowing gold medalist at the 1900 and 1904 Olympic Games. Raised during the Depression-era, Elizabeth worked on the family’s strawberry and tomato farm with her father and brothers. Her first five years of education were in a one-room school near her home. She later attended Snow Hill High School where she became one of 43 members of the 1936 graduating class. It was during her senior year that she became “Libby” to her classmates.

After graduating high school, Libby worked for an insurance company in Philadelphia. She volunteered with the U.S. Air Corps during World War II where she met her future husband, Noble H. Hodge, from Fannin County, Texas. They married in 1942 and moved to Dallas in 1945, where Elizabeth resided after Noble’s military service in England ended.

In 1967, Libby joined the administrative offices of the Southwest Center for Advanced Studies. When the center became UT Dallas in 1969, she advanced to the Department of Biology in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics (NSM), where she assisted faculty members in preparing research grant applications. Up until her retirement in 1986, Libby continued to work in grants management for the School of NSM and later in the Office of Sponsored Projects. After retiring, Libby continued to serve her community. She volunteered at Baylor Medical Center in Garland and worked in the hospital’s gift shop almost every Tuesday for nearly 30 years. She was a member of St. John’s Episcopal Church and regularly participated in their charity events. Libby lived a colorful life—one of both trials and triumph. In 1967, she survived a Cessna plane crash in Gainesville, Texas, while she and a fellow pilot participated in a flying contest sponsored by a chapter of the International Organization of Women Pilots.

Libby was an avid traveler and gardener. She transformed her yard into a personal arboretum filled with her favorite red and white flowers. An orchid hybrid was named in her honor, the Barkeria Libby Hodge. She enjoyed cooking, playing with her poodles Jabot and Jezebel, and sharing her time with others. Elizabeth "Libby" Exley Hodge passed away on January 14, 2021, at the age of 100.

Elizabeth Exley Hodge

Elizabeth Exley Hodge

Libby Hodge

Ours was a most improbable friendship: Libby Hodge was a generation older and divorced with no children. Mary and I were a young couple with pre-school children. Our political and religious views differed. She liked dogs; we had cats. How could a friendship that would last decades develop? For starters, Libby and I were enthusiastic ornamental gardeners. Then, there was the intangible bond that grew from simply enjoying one another’s company.

Libby’s friendship with us was not unique. She made and kept a large circle of friends. From high school classmates to fellow church members at St. John’s Episcopal in Dallas; from her husband’s fellow students at Baylor School of Dentistry to the people living in an adjoining apartment—who were first met through a hole in their wall-mounted, back-to-back medicine cabinets.; from neighbors along her street, to bosses and fellow employees. As the years passed, her early friendship circles grew to include friends’ children and even grandchildren. Libby actively worked to sustain these relationships. She penciled in friends’ birthdays on her calendar every year so she wouldn’t miss sending a card. She attended her high school reunion in Maryland until only she and one other alumnus remained. Annually, she would make pounds and pounds of peanut brittle to give to friends. Although she lived modestly, she would give her postman a ham at Christmas and even gift her gardener a truck. In the end, she left endowments to around sixty individuals and charities.

At Libby’s 90th birthday party, she was surrounded by ninety friends and family from across the country. What was her secret? She once told me, “If you enjoy someone’s company and they yours, don’t hesitate to initiate a get-together even if they don’t reciprocate.”

By Robert and Mary Marsh

In remembrance of

Special Acknowledgements

The Office of Undergraduate Education recognizes contributions towards publication of The Exley, Issue Six from the following individuals:

Robert Ackerman, PhD

Lisa Bell, PhD

Courtney Brecheen, PhD

Kenneth Brewer, PhD

Hillary Beauchamp Campbell

Hilary Freeman

Joannah Gentsch, PhD

Julie Haworth, PhD

P. Brandon Johnson, PhD

Carie King, PhD

Kim Knight, PhD

Aaron Kramer, PhD

Anupam Kumar

Robert Marsh, PhD

Sarina Mohanlal

Jessica C. Murphy, PhD

Bruce Novak, PhD

Shikha Prashad, PhD

Valerie Price, PhD

Justin Raman

Brian T. Ratchford, PhD

Sanjana Ravi

Amandeep Sra, PhD

Alex Garcia Topete

Frederic Traylor

Nathan Williams, PhD

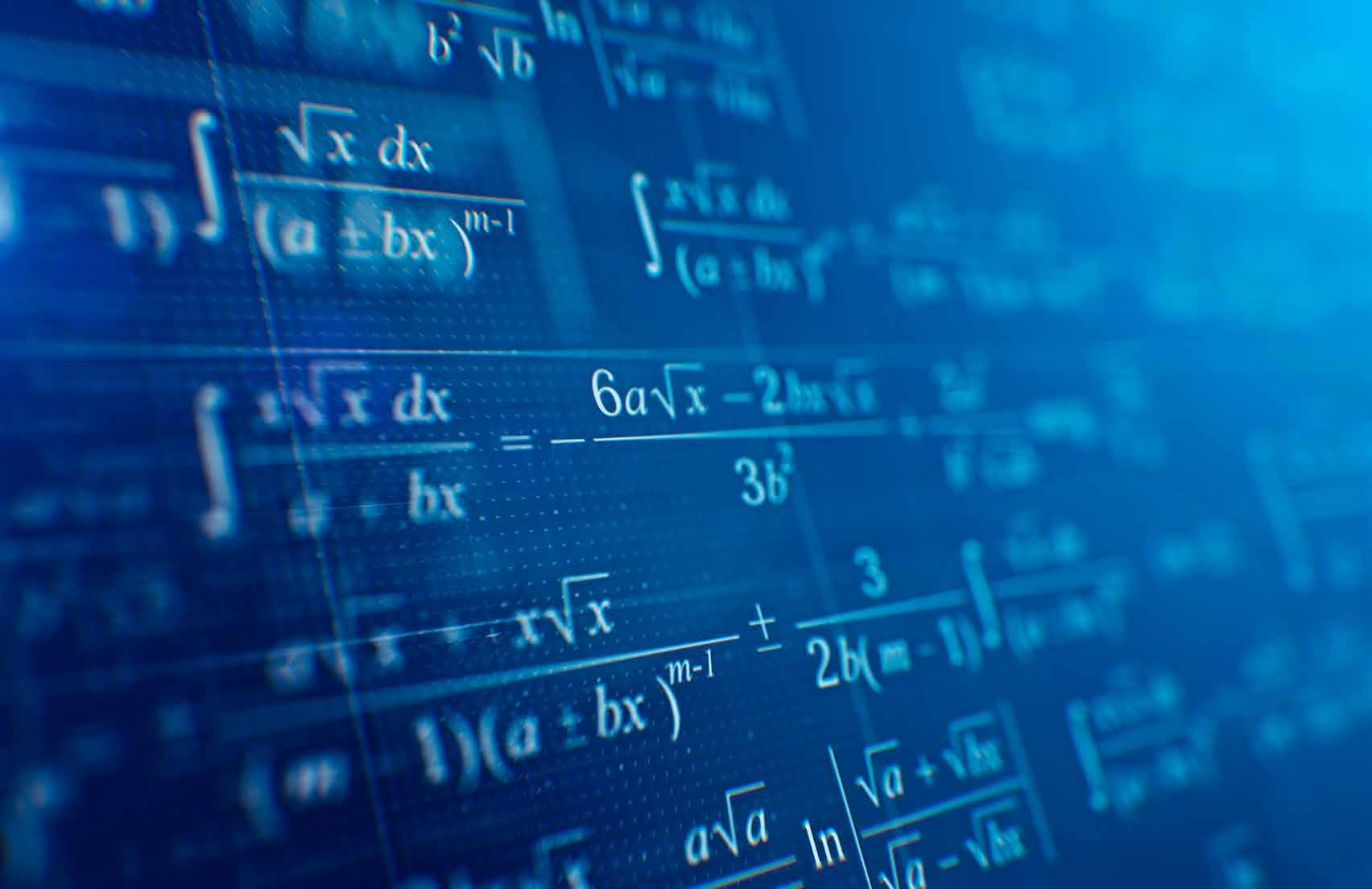

Magazine Layout and Design

Pete Pagliaccio

oue.utdallas.edu/the-exley

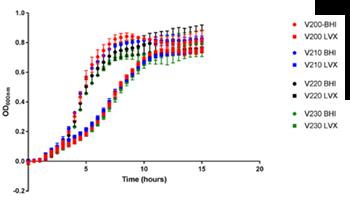

Creative 8 Opinions expressed in The Exley are those of the authors and managing editors and do not necessarily represent the view or opinion of the UT Dallas administration or The University of Texas System Board of Regents. The Exley does not claim copyright interest for any material published herein. Copyright ownership remains with the authors or other copyright holders. Research Post-Operative Oxygen Consumption: Growing Rod Graduates vs. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients — by Megan Badejo 8 Development of an Internal Offloading/Distraction Device — by Jayant Kurvari 16 Geochemical Fingerprinting of Intermittent Low-Flux Leachate from the Austin Chalk in North Texas — by Jackie D. Horn 28 The Role of Carbon-Metabolism Pathways in Levofloxacin Resistance in Enterococcus faecalis — by Uyen Thy Nguyen, Karthik Hullahalli, Kelli L. Palmer 38 Water into Wine: Hundertwasser in America — by Elyse Mack 48 Determining the Characteristic Function of Generalized Divisibility Relations — by Otto Vaughn Osterman 60 Old Shoes — by Ashlyn Huang 6 Entries Departed — by Hon Ho 14 Summer Fruit — by Izabella Dekhtyar 24 Growing Lessons — by Evelyn Alvarez 26 24 28 36 38 48 Marbled Beings — by Christina Hong Thao Mai 36 Nelsonian Knowledge: It’s There — by Michelle Onuoha 46 Reverie — by Lucie Bossart 58 "The Giving P" — Delaney Conroy 66

Contents

Undergraduate Research Programs at UT Dallas Student Research Resources

UT Dallas offers a variety of research opportunities and resources. Engaging in research as an undergraduate has academic, personal, and professional benefits. Research activities enhance analytical and critical thinking skills, which prepare undergraduates for the rigors of their profession or graduate studies. Learning how to practically apply academic concepts, discovering how to work independently, and experiencing how to function successfully as a team member are other benefits many students attribute to participating in undergraduate research activities. Exploring a discipline through research also allows students to make informed decisions about the career they wish to pursue. The Office of Undergraduate Education and other departments across campus, including the Hobson Wildenthal Honros College, academic schools, and the Office of Research provide a variety of research opportunities and other resources to assist both prospective and current undergraduate researchers.

To express your interest in getting connected with research resources, email: ugresearch@utdallas.edu.

Exley Legacy Updates

These outstanding UT Dallas alumni contributed their undergraduate research submissions for publication in prior issues of The Exley . It is a privilege for the UT Dallas Office of Undergraduate Education to provide the

Aaron Dotson – Issue 4 (2015)

Since his Exley publication, Dr. Aaron D. Dotson graduated with a bachelor’s in neuroscience from the UT Dallas School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences in May 2015, where he also served as the commencement speaker and was recipient of the Student Leadership Award.

Dr. Dotson then went on to complete medical school at Saint Louis University (SLU) School of Medicine, and is now completing his residency training in ophthalmology at the University of Iowa. He plans to become a specialist in either cornea or oculoplastic surgery. Dr. Dotson is a strong believer in mentorship. He is an active member of the Black Men in White Coats organization, where he has been featured on NBC’s Today Show and in Forbes Dr. Dotson plans to share his passion with the world by preserving sight and mentoring the next generation of physicians.

Cara Curley – Issue 2 (2013)

Since graduating from UT Dallas with a degree in arts and technology, Cara’s work has been displayed on TV interfaces in thousands of hotels rooms across the country. She’s partnered with Rooster Teeth, Explosm, and Albino Dragon to produce graphics for board games. Cara has also developed packaging for themed playing card decks, including popular brands like Supernatural, Power Rangers, and The Princess Bride. More importantly, she's acquired the greatest gift of all—Moose, the cat. As busy as Cara is with design projects, her and Moose are two peas in a pod. Cara hopes someday her furry friend will learn to bring her caffeine.

(updates provided in 2022)

opportunity for students engaged in research to experience publication of their early research endeavors. Congratulations to these past contributors for their outstanding accomplishments since graduating from UT Dallas.

Karthik Hullahalli – Issue 5 (2016)

Karthik graduated UT Dallas with a bachelor’s in biology in December 2017. He spent much of his undergraduate career doing research in bacterial genetics with Dr. Kelli Palmer. Upon graduation, he worked in her lab as a tech for six months finishing up his research projects. As a graduate student at Harvard University, he currently studies within-host population dynamics during bacterial infection.

Andrew Torck – Issue 5 (2016)

Since graduating from UT Dallas, Andrew moved to the Houston area and graduated from The University of Texas Medical Branch in 2021 to pursue his dream of becoming a medical doctor. He currently works as an anesthesiology resident. When he’s not in scrubs, he takes time to enjoy the calmness of Galveston island, and indulges in his favorite hobby, pen and ink drawing. He also sells his art at local art markets. Andrew’s approach to life is simple yet profound: stay positive. “I realized that it is incredibly important to stay true to yourself and to always make time for things that make you happy, especially in times of stress. My advice to anyone reading this is to find something you enjoy doing and run with it, solely because it makes you happy; life is too short to have regrets!”

1 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 2

Contributor Spotlights

Contributors to The Exley represent the rich diversity of talent, interests, and engagement among the UT Dallas undergraduate population. While the Office of Undergraduate Education temporarily paused publication of The Exley after receiving submissions for the Sixth issue, the contributions of those selected for publication did not stop, even for those who graduated.

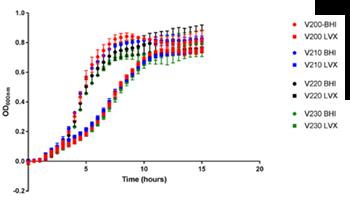

Uyen Thy Nguyen

Uyen Thy Nguyen is a graduate student in the Microbiology Doctoral Training Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she is studying the human skin microbiome. She completed her degree in biochemistry at UT Dallas as a Diversity Scholars Program fellow.

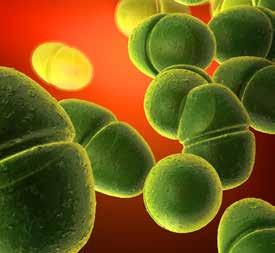

Her research career began at UT Dallas with Dr. Kelli Palmer as an NSF Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation fellow. Her studies focused on unraveling the mechanism of antibiotic resistance using CRISPR-Cas as a tool. Outside the classroom, Thy started Pretty Hard Decisions, a podcast that covers real stories from those on the path toward their Ph.D. The podcast also educates high school and undergraduate students from areas who do not have access to research mentorship.

Their impact on campus remains The following highlights multiple contributors from the Sixth issue. The Office of Undergraduate Education hopes these spotlights inspire current undergraduates to embrace their own unique intersectionality of identities and abilities and ultimately pursue opportunities to have them showcased.

Jayant Kurvari

Jayant Kurvari graduated with honors with a bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering from UT Dallas in 2018. During his time at UT Dallas, he had the opportunity to work with the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital to design and develop a hip implant. From this experience, he became passionate about producing devices that can better the quality of life for people and is currently pursuing a career in engineering and designing medical devices. He is currently working at Orthofix as a Senior Supplier Quality Engineer. Outside of work, he enjoys traveling, running, playing guitar, and spending time with family and friends. He plans to return to school to pursue his masters.

Delaney Conroy

Delaney Conroy (they/she) is an alumna of UT Dallas. They received their Bachelor of Arts in emerging media & communications with a minor in psychology in spring 2020. During this time, their sound and land art capstone project, Wind Chimes for the Prairie received an undergraduate research award. They spent the 2018-2019 academic year studying fine and contemporary art at the Marchutz School of Fine Arts at the Institute for American Universities (IAU) in Aix-enProvence of France. In 2019, they created their sculpture, Karen, located on the Marchutz studio grounds. Since graduating, Delaney has worked as a designer and artist. Their work centers on the relationships between landscapes and their people.

Megan Badejo

Megan Badejo graduated Summa Cum Laude from The University of Texas at Dallas with a bachelor’s degree in healthcare studies and a double minor in biology and psychology. While a UT Dallas student, Megan was an active member and leader of the Undergraduate Success Scholars, served as the Helmsman of the UT Dallas NCAA Women’s Basketball Team, held multiple leadership positions on the Student Athlete Advisory Committee, and served as Vice President of the Minority Association of Pre-Medical Students. Megan also served as the event coordinator for the African Student Union and in multiple leadership roles for the Black Student Alliance. In addition to working in chemistry and neuroscience labs, Megan was also a research intern at Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children under Dr. Amy McIntosh, studying comparisons in the metabolic oxygen consumption and functional outcomes in scoliosis patients.

During her time at the university, Megan received the Dean’s Milestone Service Honor Award, a position on the Dean’s List, the Outstanding Undergraduate Student Award, four Academic All-Conference Recognitions, four American Southwest Conference Tournament appearances, two American Southwest Conference Tournament championships, and a National Tournament Sweet Sixteen appearance.

Megan graduated from the Texas A&M College of Medicine in pursuit of her lifelong dream of delivering hope to marginalized and under-resourced groups. She is currently an orthopedic surgery resident at Duke University Hospital.

Hon Ho

Hon Ho graduated in 2018 from UT Dallas with Master of Science in accounting, finance, and economics. He currently works in investment banking as a Valuation Analyst. He is a Licensed CPA in Texas and has worked in several fields in business, including tax, lending, and credit ratings. Hon enjoys learning about a broad range of subjects including economics and philosophy. In his spare time, he is an amateur poet, writing about various themes in life and believes art and self-expression has a place in everyone’s life.

Elyse Mack

Elyse Mack graduated from UT Dallas in May 2018 with a Bachelor of Arts in visual and performing arts and a concentration in art history. During her time at UT Dallas, Elyse was a McDermott Scholar, the editor-inchief of AMP, and a club badminton player. In June 2020, Elyse received her Master of Art in art history at Williams College, and now serves as a research assistant in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Saint Louis Art Museum. Elyse hopes that her research on eco-criticism in the global contemporary and along wih her leadership in environmental justice will make museums more accessible and equitable places for all.

3 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 4

I first began writing poems after becoming not inspired by poetry, but by song lyrics, and the complex yet concise narratives that could be contained within four minutes of choruses and verses. I couldn’t sing, so I turned to poetry to do the same. Today, I still find inspiration for poetry in music.

A lyric from Weezer’s “Undone” goes, “If you want to destroy my sweater, hold this thread as I walk away.” The mundane but vivid imagery packed into this line has shaped much of how I write today. Using something commonplace like a sweater to symbolize something as heartbreaking as a relationship falling apart is what has kept me fascinated with poetry all these years. Many of my poems, including this one, are centered around common objects or daily routines. I like the idea of taking something ordinary like old shoes and thinking to yourself: is there more to you?

In “Old Shoes,” I wanted to focus on personal growth, so I centered the poem’s concept around a narrator outgrowing a pair of shoes. I also wanted to capture a sense of progression and regression, so throughout the poem, the narrator is torn between feeling trapped in these shoes she loves but has outgrown, and a desire to run away. I used imagery involving traversing through tunnels versus tiptoeing on bloodied feet to capture this feeling. Also, repetition is evident in the poem’s structure, with three phrases repeated throughout the piece and edited each time as if the narrator is reflecting and improving upon herself as the poem goes on.

— by Ashlyn Huang

Old Shoes

My toes scrunch up like talons at the tips of my old shoes.

My layers, dead epithelium, line the insides, the pair a part of me.

I try again to fit myself inside of me. Bad fit.

Shaking my head, my shaking hands remove one toe at a time and try again.

They asked for a better world, and got this instead.

I asked for a better world and reclined my chair, rested my head. I asked myself to get better, and then asked myself not to be selfish.

Toeless, I tiptoe on the soles of my feet in my old shoes that fit again.

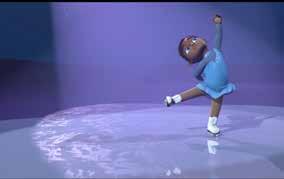

I am young again, and I pirouette through the house carelessly, infinitely, unafraid to bleed.

I wanted to come home to a poet and a dancer, conversing in bodily synchronicity and forced introspection. Instead, I become a poet and a dancer, trapped in my own movements and words.

There is a greener patch on the other side. There is a better breath of air beyond my lungs. There is a light at the end of the tunnel, but I am running towards the wrong end.

They asked for a better world and got free long-distance phone calls. I asked for a better world and called my grandparents overseas. I asked myself to get better and then said “progress is measured in distance, not displacement.”

I yearned to be at the right end of the tunnel with the light. Breathless, not at the distance I had traveled, but the beam passing through my body, illuminating me straight out of the heart.

I yearned for a beautiful sentence that wasn’t laced with melancholy, and when the tendrils burst through the ceramics I could feel the smile illuminating me from the inside.

There is an old shoe box in the basement, stapled indentations lining the lid like ants, and when the dust settled, I ripped open its carcass with steady hands.

They asked for a better world and self-help books became a postmodern cultural phenomenon. I asked for a better world and got myself a copy of one.

I asked myself to get better and bought a bigger pair of shoes.

5 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 6

Post-Operative Oxygen Consumption: Growing Rod Graduates vs. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients

Early onset scoliosis (EOS) is an abnormal sideways curve or deformity of the spine, often in the shape of an “S” or a “C,” found in patients under the age of ten years. The cause of EOS is multifactorial. Sometimes, it develops in patients for an unknown reason; these patients are said to have idiopathic infantile scoliosis. Other patients could have suffered improper spinal development in utero and have a condition referred to as congenital scoliosis. A patient could also have a neuromuscular condition such as cerebral palsy, or a spinal cord injury that led to the deformity known as neuromuscular scoliosis.

— by Megan Badejo

7 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 8

Introduction

Syndromes like Marfans or Prader-Willi are also associated with EOS patients: these patients are said to have syndromic scoliosis. Karol et al. studied early definitive spinal fusion in which the spines of EOS patients are straightened and fused in place, and found that patients required at least 22 cm of thoracic height for adequate ventilation1. Unfortunately, early fusion of the thoracic spine led to a loss of thoracic height, totaling just 10 cm of growth in some patients. Those patients suffered severely diminished lung functionality. To fight back against the negative consequences of early definitive fusion, Dr. Robert Campbell developed innovative treatment options. In 1988, Dr. Campbell used his vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR) as a treatment for congenital forms of EOS to improve the deformity and allow for growth of the developing spine. The VEPTR prosthesis became the first long-term adjustable implant utilized that led to “growth-friendly” surgical treatments for EOS patients2. Growth-friendly treatments include VEPTR growing rods, curved metal rods that are surgically attached to the spine, ribs or pelvis and are lengthened over a period of time. Growing rods are utilized to avoid and treat thoracic insufficiency syndrome, a condition that occurs when the chest is incapable of supporting sufficient breathing due to chest deformity. The growing rods allow for some spinal correction as the patient grows and matures. Due to these revelations, practitioners shifted to implementing procedures that delay spinal fusion.

EOS patients have varying degrees of physical impairment, such as underlying medical conditions, severity of spine curvature and chest-wall deformity that should be considered when determining interventional therapy. Patients with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) face similar issues when it comes to abnormal curvature of the spine. A major difference between EOS and AIS is that AIS does not manifest until late childhood, older than ten years of age, or adolescence. AIS appears through the onset of puberty as a child grows rapidly during this time. Much like EOS patients, the AIS population with larger curve-deformity magnitudes also has compromised pulmonary function3,4,5. Posterior spinal fusion (PSF) is a surgical procedure that is often utilized in the treatment of AIS. This operation works in a twofold manner. It offers correction to the abnormal spine curvature, as well as prevents future spinal curve progression.

Growing Rod Graduates (GRG) are children with EOS who are ≥ 3-years post-surgical application of a growth-friendly construct with subsequent spinal fusion or are at least 1 year from their last lengthening. When evaluating the patient’s “true” outcome after spinal surgery, the patient is as-

sessed using a specific test. Oxygen consumption during V02 submaximal testing is a method to measure the patient’s cardiopulmonary functional capacity. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) can be used to analyze the mechanical properties of the lungs. However, according to Aaron et al., the PFTs have their own limitations6. Forced vital capacity (FVC), that amount of air a patient can force out, has an accuracy of only 60% when patients with restrictive lung disease caused by conditions like scoliosis are tested. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), the amount of air forced out in one second, is also reduced. As a result, the FEV1/FVC ratios will appear normal. In turn, this can bring about erroneous conclusions about lung function in patient populations with restrictive lung disease. When combining the results of both PFTs and VO2 submaximal oxygen consumption testing, the patients can be evaluated and judgments can be made concerning the patients’ lung functioning during routine activities of daily living and while exercising/playing. Jeans et al. demonstrated that there are some GRG patients who possess the ability to exercise and perform activities of daily living at the same level as age-matched normal controls, despite having PFT data consistent with significant pulmonary compromise7 To reinforce the use of PFTs and gain a more accurate view of the patients, a metabolic oxygen test was performed. Metabolic oxygen consumption via VO2 submaximal exercise testing is a reliable outcome measure that was used to assess functional ability in GRG patients with EOS rather than pulmonary function tests (PFTs) alone8.

These conditions were maintained, as the purpose of this study was to compare the metabolic oxygen consumption and functional outcomes of GRG patients to patients with AIS that underwent posterior spinal fusion (PSF) with instrumentation ≥ 2 years prior. In doing so, the aim was to evaluate where the two patient groups stood in regard to their activity levels. The hypothesis was that post-fusion AIS patients would have better functional ability with less oxygen consumption during exercise than GRG patients.

Materials and Methods:

This was an Institutional Review Board-approved (IRB approval no.: 062004-059) study in which two cohorts of patients, 54 in total, with prospectively collected data were compared in a retrospective manner. Both cohorts’ data were collected at a single institution.

Cohort 1 contained 42 AIS patients (7 males, 35 females) who had undergone PSF with instrumentation ≥ 2 years prior. Their mean age at the time of surgery was 14.5 years (10.2-18.7 years) and 16.7 years (12.2-21.7 years) at the time of the testing. Exclusions from this study included patients

with index surgery only for GRG patients, those with underlying syndromes or conditions and patients with revisions and intradural processes. These patients' spinal deformities in the coronal or frontal plane were corrected from an average of 59.7 to 26.6, and, in the sagittal plane, the deformities were improved from an average of 32.9° to 23.9°. Patients were observed leaning less towards the right or left directions, and, in sideways observation, to be standing more upright than backwards or forwards.

Cohort 2 included 13 GRG patients (5 male, 8 female). Nine patients had undergone definitive spinal fusion and three had experienced lengthening and were being observed. Their mean age was 5.3 years (1.3-8.3 years) at the time of surgery, and the mean follow-up age was 7.2 years (3.710.4 years). At the time of testing, they were a mean of 12.5 years (9-16.5 years). Patients were excluded from this study if they were less than a year from their last study. Average Cobb angle, or degree of spinal deformity, before the surgery was 85.9° and 44.2° afterwards in the frontal plane, and changed from an average of 58.9° to 52.8° in the sagittal plane.

PFTs were conducted by The Movement Science Lab. Measures included both absolute predicted values and percentages of predicted values based upon arm span of Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) and FEV1.

Metabolic testing was conducted using a COSMED K4b2 portable telemetry unit with a heart-rate monitor. The patients fasted for at least two hours prior to testing. Talking was discouraged during the testing, and hand signals were used if a participant wanted to communicate.

Oxygen consumption testing consisted of a five-minute seated rest period, followed by a 10-minute warm-up while walking at a self-selected comfortable walking speed. Following the warm-up, the patients participated in a submaximal graded exercise test on a treadmill. The treadmill protocol consisted of three-minute stages. Each stage was increased incrementally by speed and incline. Speed was determined by the individuals, and held constant when they felt as if they were “walking at a brisk pace.” The incline was increased by 3% at each stage until 85% ± 5% of age predicted maximum heart rate was achieved. At each stage, patients were asked to rate their perceived exertion (RPE) using the Borg scale from 6–209 In patients who could reach 85% ± 5% of their maximum predicted heart rate (220-age), VO2 max was predicted using the linear relationship between heart rate and VO2 rate10

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS, version 9.4. Group averages were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and correlations between metabolic data and PFT variables were assessed with a Spearman correlation coefficient (α = 0.05).

Results:

42 AIS and 12 GRG patients participated. The primary diagnoses for the GRG patients were: congenital (6), syndromic (2), neuromuscular (1) and infantile idiopathic scoliosis (3). The average age at index surgery was 5.3 years (1.3-8.3 years), and the average follow-up age from the initial surgical application of the growth friendly spine construct was 7.1 years (3.7-10.4 years). On the day of oxygen consumption testing, the average duration since the last spine procedure was 2.3 years (1.0-3.6 years). Nine GRG patients underwent definitive spinal fusion, and three had completed lengthening and were being observed. The curve magnitude in the coronal plane was an average of 85.9° before fusion and improved to an average of 44.2° after fusion, and the sagittal plane cure magnitude improved from an average 58.9 before fusion to 52,8 in the sagittal plane.

The 42 AIS patients were an average age of 14.5 years (10.218.7 years) at the time of PSF with instrumentation and at least two years from definitive fusion. Their frontal plane was corrected from 59.7° to 26.6°, and in the sagittal plane, the deformity was improved from 23.9° to 32.9°.

PFTs were significantly better in the AIS cohort: average FVC% of 82.2 vs. 45.5 (p < 0.001). GRG patients walked at a slower speed (p = 0.45) and with a higher VO2 cost (p < 0.001). In the final stage of the treadmill test, GRG patients had a higher breathing rate, while total volume and ventilation were significantly lower compared to AIS patients (p < 0.05).

PFTs were significantly better in the AIS cohort: average FVC% 82.2 vs. 45.5 (p < 0.001). GRG patients walked at a slower speed but were not significantly different (p = 0.45), and with a higher VO2 cost (p < 0.001). 37 of 42 (88%) of AIS patients and nine out of 12 (75%) pf GRG patients were able to complete the 85% of predicted maximal protocol. In the final stage of the treadmill test, GRG patients had a higher breathing rate, while total volume and ventilation were significantly lower compared to AIS patients (p < 0.05). In patients who reached this goal, VO2max was predicted, and no difference existed between the AIS (39.3 + 6.1 L/ kg/min) and GRG patients (38.5 + 10.3 L/kg/min) (p = .945).

9 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 10

Discussion:

In a previous study by Jeans et al., it was concluded that patients with EOS who had undergone growth friendly surgical treatment were able to participate in physical activity11 Even though EOS patients had poor PFTs (avg. = 45.5 FVC%), they could keep up with age-matched controls during activities of daily living, i.e., playground and recess activities, with slightly slower speed and with increased oxygen cost. EOS patients commonly are given a poor prognosis, which is thought to be correlated to the variety of their comorbidities. This study was designed to determine how EOS patients who completed growth friendly surgical management compared to other pediatric spine-fusion patients who had undergone surgical treatment of AIS. The perception is that AIS patients are fairly normal children, except for the curvature in their spines. Compared with nonscoliotic controls, most patients with untreated AIS function at or near normal levels12. They often do not present with comorbidities and many times after correction, the patients can return to regular activities. This paradigm makes them particularly suitable for comparison to EOS patients when judging the effects of scoliosis correction on the body of two separate pediatric patient populations. The AIS group can function as a better contrast than a traditional control could, as a normal control would not undergo a similar surgical experience. With this study, the researchers stand to gain realistic information to share with patients and give the families feasible expectations of functionality based on children who have undergone the same procedure. As expected, this study found that PFTs were significantly better in the AIS cohort: average FVC% of 82.2 vs. 45.5 (p < 0.001). GRG patients walked at a slower speed (p = 0.45) and with a higher VO2 cost (p < 0.001). In the final stage of the treadmill test, GRG patients had a higher breathing rate, while total volume and ventilation were significantly lower compared to AIS patients (p < 0.05).

Compared to patients who undergo spinal fusion for AIS, GRG patients have significantly slower walking speeds and decreased exercise tolerance. Although the GRG cohort was small, this data indicates significance in that these EOS patients have the capacity to perform aerobic exercise at extents similar to that of AIS patients. When compared with normative data, this EOS cohort fell in the “Fair-to-Good” classification, showing that EOS patients can achieve function equal to healthy controls who tested as Fair-to-Good13

This is of particular importance when it comes to discussing the advancement of children and what is necessary for proper development. Experts state that children require at least an hour of moderate to vigorous exercise each day for positive health benefits14 In general, it is important to foster physical interactions in children, but for EOS patients who are susceptible to chronic diseases, it may be of greater importance, as their daily activities have the potential to reduce the incidence of chronic disease that manifest in adulthood.

Through metabolic testing, this study has provided greater understanding of the metabolic capacity of EOS patients following growth friendly treatments in relation to that of the testing performed on AIS patients. Contrary to the poor PFT results of the EOS patients after correction, it is apparent that these patients have more oxygen in reserve than previously thought.

Partaking in physical activity during and after growthfriendly treatments in EOS patients is emphasized for healthy recovery. Jeans et al.’s study has shown that EOS patients’ PFT results and pulmonary perception after growth friendly treatments are not a reason to withhold participation in activity15. It was found that 75% of the GRG cohort was able to keep up with their age-matched controls that completed 85% of the predicted maximal protocol. Our study supports this as we found that GRG patients’ performance was similar to AIS patients who had 88% of the cohort complete 85% of the predicted maximal protocol. Additionally, it should be noted that the GRG cohort had a spinal curvature that was more prominent, even after correction. GRGs had a mean curve of 44.2 degrees in the frontal plane and 52.8 degrees in the sagittal plane, compared to the AIS cohort that held a mean curve of 26.6 degrees in the frontal plane and 32.9 degrees in the sagittal plane after correction. This suggests that the GRG cohort’s thoracic height was shorter than that of the AIS cohort, but they were still able to find success in their aerobic capabilities. This finding was further supported by Glotzbecker et al.’s work as they found that the thoracic height of the EOS patient was a very weak predictor of pulmonary function outcomes16 and as we’ve found, PFTs alone are not the best predictors of actual physical capability in EOS patients.

References

1. L. A. Karol, et al., “Pulmonary Function Following Early Thoracic Fusion in Non-Neuromuscular Scoliosis,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 90, no. 6 (2008): 1272-81.

2. R.M. Campbell Jr., “VEPTR: past experience and the Future of VEPTR Principles,” European Spine Journal 22, Suppl. 2 (2013): S106-17.

3. M.G. Vitale, et al., “A Retrospective Cohort Study of Pulmonary Function, Radiographic Measures, and Quality of Life in Children with Congenital Scoliosis: An Evaluation of Patient Outcomes After Early Spinal Fusion,” Spine 33, no. 11 (2008): 1242-9.

4. P.O. Newton, et al., “Results of Preoperative Pulmonary Function Testing of Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Study of Six Hundred and Thirty-one Patients,” Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 87, no. 9 (2005): 1937-46.

5. J. Johari, et al., “Relationship Between Pulmonary Function and Degree of Spinal Deformity, Location of Apical Vertebrae and Age Among Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients,” Singapore Medical Journal 57. no. 1 (2016): 33-8.

6. S.D. Aaron, R.E. Dales, and P. Cardinal, “How Accurate is Spirometry at Predicting Restrictive Pulmonary Impairment?,” Chest, 115, no. 3 (1999): 869-73.

7. K.A. Jeans , et al., “Exercise Tolerance in Children With Early Onset Scoliosis: Growing Rod Treatment ‘Graduates,’”. Spine Deformity 4. no. 6 (2016): 413-419.

8. K.A. Jeans, “Exercise Tolerance in Children With Early Onset Scoliosis,” pg. no. 413-419.

9. G.A. Borg, “Psychophysical Bases of Perceived Exertion, ” Medicine & Science in Sports Exercise 14, no. 5 (1982): 37781.

10. E.H. SK Powers, ed., Exercise Physiology: Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance. (Dubuque, IA: Brown and Benchmark, 1997), pg. no.

11. K.A. Jeans, “Exercise Tolerance in Children With Early Onset Scoliosis,” pg. no. 413-419.

12. M.A. Asher and D.C. Burton, “Adolescent Idiopathic S coliosis: Natural History and Long-Term Treatment Effects,” Scoliosis 1, no. 1 (2006): 2.

13. Vivian H. Heyward, “The Physical Fitness Specialist Certification Manual in Advance Fitness Assessment & Exercise Prescription (Dallas TX: The Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research 1998), 48.

14. W.B. Strong, et al., “Evidence-Based Physical Activity for School-Age Youth,” Journal of Pediatrics 146, no. 6 (2005): 732-7.

15. K.A. Jeans, “Exercise Tolerance in Children With Early Onset Scoliosis,” pg. no. 413-419.

16. M. Glotzbecker, et al., “Is There a Relationship Between Thoracic Dimensions and Pulmonary Function in Early-Onset Scoliosis?,” Spine 39, no. 19 (2014): 1590-5.

11 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 12

I believe poetry to be a very precise form of expression in which subjects and thoughts are expressed through short terms and lines, and very little excess is allowed to prevent muddling the end meaning. Poetry, to me, expresses this through moments, much like how we can sometimes define ourselves or our relationships with others through moments, no matter how large or small those moments are. This writing is an example of that through a moment felt by the person in this poem.

I write mainly through prose or free verse, compared to formal rhyming poetry, because it adds a balance to this conciseness by removing restrictions on how meanings need to be expressed. My belief is that expression should be universally approachable, spoken simply and sweetly.

— by Hon Ho

Entries Departed

Thoughts fall from the sky

Still remnants of a different day

Closing her eyes, watching old things fall

Pieces of days before; written, locked away

Slowly drifting towards the sunrise

Memories once held by thin strings of regret

Left to scatter free; fleeting effortless

As fears fade away between the distance

Someone else; still reminders of her

Worries of things never said

Lost alongside a broken binding

She imagined those moments once more

Thoughts falling further inside

A hand gently touching old scars

And quietly, she sat watching the horizon

Past lives falling into an abyss

Abandoned secrets, left for the crowd

13 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 14

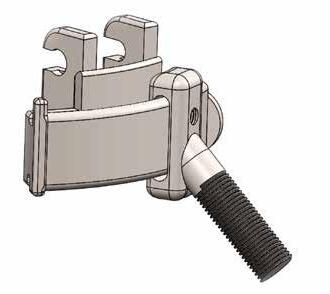

Development of an Internal Offloading/Distraction Device

Perthes disease is an idiopathic childhood condition that occurs when the blood supply to the femoral head ( Figure 1 ) is disrupted, leading to osteonecrosis, or bone cell death. It is one of the most common hip disorders in children, and the risk of a child developing this condition is about 1 out of every 1200 children over his or her lifetime. As the condition progresses, the femoral head gradually begins to break apart as shown in Figure 2. If left untreated, the femoral head can deform and not correctly behave as a ball-and-socket joint in the acetabulum, leading to an early onset of arthritis. This can develop into more serious conditions, such as a total hip replacement for the patient in his or her teens.

— by Jayant Kurvari

15 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 16

Introduction

or separates, the femoral head from the acetabulum, which helps restore blood flow to the femoral head, the main objective of the device. It remains attached to the patient until the femoral head returns to a ball-shape, which is usually after 6-12 months. However, there are three primary complications with this device. First, the body is exposed to the external environment, which could potentially let the body be susceptible to infections. Another problem that the external fixator presents is that, since the device is quite large, there is a large bending moment placed upon the device. This can lead to pivoting of the screws, causing microfractures in the device. In turn, this can potentially lead to larger, more serious bone fractures. Finally, there’s only one axis of rotation for the leg – flexion/extension. This axis of motion is shown in Figure 4. This is a particularly challenging risk, as children tend to run, jump, bounce, and perform a variety of other motions with their legs.

Current Treatment

Current treatment of Perthes disease involves an external fixator, which stabilizes the bone and tissue from outside of the body as seen in Figure 3. This external fixator distracts,

To correct these issues, my team and I developed an internal hip offloading device that was capable of treating Perthes disease, while rectifying the problems presented by the external fixator.

Fabrication and Methodology

The primary objective of the project as set by Scottish Rite Hospital for Children was to develop a biocompatible implant that was capable of 10 mm of distraction, or separation, between the acetabulum and the femoral head that was capable of at least one range of motion – flexion/ extension. Secondary or stretch goals set by Scottish Rite were intraoperative distraction adjustment, the ability to withstand the weight of a large child (approximately 1000 N or 225 lbs.) and all three ranges of motion – flexion/extension, internal/external rotation, and adduction/abduction.

While developing the device, my team and I worked around some constraints presented by the body. Since the device would be implanted within the body, we had to limit the size of the device for easier surgical implementation. In addition, this would also reduce the bending moment device, reducing the chance of microfractures appearing in the bone. Furthermore, this would limit the possibility of infections significantly because the internal tissue isn’t exposed to the external environment. Further anatomical constraints presented by the body included nerves and blood vessels, and the device was designed with the idea that it should not contact or interfere with these features, as it could be detrimental to the patient’s health.

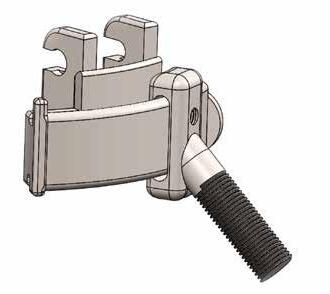

With these constraints, the proposed device was fabricated using a computer-aided design program, SolidWorks, capable of achieving all three axes of rotation in a healthy femur – flexion and extension, internal and external rotation, and abduction and adduction as seen in Figure 5. However, the latter two had a more limited amount of rotation compared to flexion and extension – the main axis of rotation of the project.

The device would be constructed from medical grade stainless steel (316L) because of its remarkable biocompatibility and strength properties. It was chosen over an alloy of titanium, a metal known for its osseointegration, or bone-integrating, capabilities, because the device was not intended to stay in the body for a long period of time. Since osteointegration occurs after several months, it was determined that the device should be made from stainless steel1

in each patient. This included, but was not limited to the length of the femoral neck and angle of the femoral neck. To develop the proposed device, a typical femur and pelvis were used2. Another feature that was included was the addition of a modular distraction component. This would enable the distraction of the femur to be easily managed. If the physician wanted to gradually decrease the amount of distraction from the acetabulum to the femoral head, he or she could conduct a minimally invasive surgery to adjust it. This intraoperative distraction is a secondary stretch goal provided by Scottish Rite.

Device Components

Trochanter Plate

The trochanter plate allowed the device to be attached to the lateral side of the femur by placing screws in at the various holes to secure the device to the bone. This allowed for the device to be secured to the body as seen in Figure 5.

features.

The device needed to provide distraction from the femoral head and the acetabulum, or the ball-and-socket respectively, which was the main objective of the project. Several additional features were also implemented in the device that were not present in the external fixator. The first feature was an intraoperative adjustment through the turnbuckle in the device. This would allow for the surgeons to accommodate for the variability in anatomical features present

17 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 18

Figure 1. Anatomy of human hip and femur: The femur and acetabulum form a ball-and-socket joint which allows the hip to move freely about the femoral head.

Figure 2. X-ray of Perthes disease: A normal femoral head is displayed on the left and a femoral head affected by Perthes disease is displayed on the right. The femoral head on the right does not receive nutrients from the blood, resulting in bone cell death.

Figure 3. Current solution - external fixator: On the left is the device currently used by Scottish Rite Hospital for Children, and the diagram on the right is a basic overview of how the device is fixed to the body for stabilization purposes

.

Figure 5. Full device: A view of the full device attached to the lateral side of the femur

Figure 4. Angles of rotation of the hip: The three axes of rotation are: flexion-extension (F/E), abduction-adduction (Ab/Ad), and internal-external rotation (ER/IR). Rotation exhibited by each of these degrees of motion is limited by anatomical

Flexion-Extension Component

The first part of this device attached to the lateral side of the femur, where the trochanter plate is located. This component of the device allowed for rotation along the flexion and extension plane. Theoretically, this rotation can rotate a full 360o; however, due to anatomical limitations of the human body, this actual range of motion likely varies.

Turnbuckle

The addition of this component to the device will allow for surgeons to adjust the distance between the flexion-extension component and the internal-external rail clamp as seen in Figure 7. In doing this, the device can accommodate for the anatomical differences present in patients. This device can allow for either medial and lateral adjustment, allowing a maximum of 4 mm in either direction.

Internal-External Rail Clamp

This component of the device will attach onto the internalexternal rail and be connected to the turnbuckle (Figure 8). In addition, if the surgeons desire, the internal and external rotation is a full 360 and can be prevented by placing a screw through the rail clamp, fixing it to the internal-external rail.

Internal-External Rail

This component of the device allows for rotation, and theoretically allowing for internal and external rotation 15o in either direction; however, this result is ultimately determined by anatomical characteristics and may be impeded by muscles or other surrounding support tissue.

Distraction Module

This component of the device allows for surgeons to adjust the distance between the internal-external rail and the pelvic plate attachment, seen in Figure 9. In doing this, the device can accommodate for the anatomical differences present in patients. This component of the device can allow for superior or inferior adjustment, allowing for 10 mm of distraction in either direction, achieving the main objective of the project.

Pelvic Plate Attachment

This is the final component of the device. The pelvic reconstruction plates are attached to the lateral side of the pelvis, bending the plates as needed to secure it to the body, allowing for the device to hold more weight from the body. These are the four parts that are sticking outside of the distraction module in Figure 9. This allows for the device to be secured to the body and accommodates for anatomical differences of patients’ pelvises.

Testing and Results

To provide assurance that the device would be feasible for implantation within the body, extensive testing was conducted. All testing was conducted on the full device made from surgical grade stainless steel (SST 316L), for its impressive strength and biocompatibility properties.

Distraction Analysis

The next set of testing would look at the distraction of the device and whether it was adjustable. Testing this achieves the primary objective of the project – to distract the pelvis from the femur to restore normal blood flow to the femoral head. To do this, a demonstrative test was conducted. If the device could distract medially or laterally at the turnbuckle for more than 4 mm, this test would pass. This number was chosen based on the variability of subjects’ anatomical features 2. In addition, if the other distraction component, the distraction screw, could distract the device superiorly or inferiorly by 15 mm, this test would pass. This number was chosen as the optimal distance from the femoral head to the acetabulum for optimal healing as instructed by physicians at Scottish Rite.

Simulation of the distraction analysis was also done with a model of the femur and pelvis to replicate how the device would function in the body. This distraction distance from both distraction components was achieved.

Kinematic Analysis

First, kinematic testing was conducted to determine if the device was functioning as it should by motions depicted in Figure 10. The most significant motion tested was flexion and extension. The device should have a minimum of 80o of flexion and a minimum of 20o of extension. Next, the internal and external rotation as tested; a minimum of 15o of rotation in both the internal and external directions was desired. Finally, there should be less than 5o of movement in the abduction and adduction plane. These measurements were similar to the values determined in research done on hip kinematics 3 .

Simulation of the kinematic analysis of the device was done with a model of the femur and pelvis to replicate how the device would function in the body. Testing went as expected – the degrees of rotation expected were achieved.

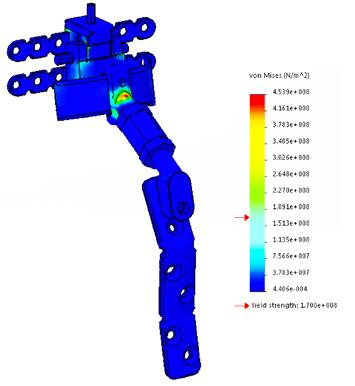

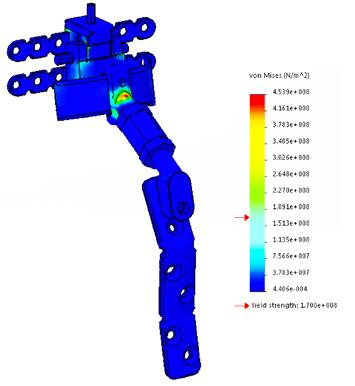

Deformational Analysis

Simulated deformational analyses were performed using the finite element analysis feature in SolidWorks. A load was placed on the lateral side of the pelvis, propagating downward through the device. This would simulate the compressive force experienced by the weight of the patient. To simulate the weight of the patient, a quantity of 1000 N was chosen to reflect the research conducted by National Center of Health Statistics4 The quantity chosen was two standard deviations from the average weight of 18-year-old males, to ensure coverage of the weight of most children. To further assess the quality of the device, a 30% safety factor was implemented by increasing the compressive force to 1300 N (293 lbs.). This would allow for unexpected weight loads applied on the patient to be withstood by the device.

The results of this study demonstrated that there was very little deformation in the device, only 17.5 µm as seen in Figure 10. This value is very small, and the device should still be able to function at all the places where articulation occurs. The maximum stress that this device can handle is 1.700·108 N as seen in Figure 11. This is much more than the elasticity of bone, demonstrating that the bone will break before our device will 5 .

19 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 20

Figure 6. Flexion-extension component

Figure 7. Turnbuckle

Figure 8: Rail with rail clamp

Figure 9. Distraction module

Figure 10. Deformational analysis of device (displacement)

From these results, it can be concluded that the device will work within the human body as intended with little risk of deformation or fracture. Of course, this was calculated using the assumption of an average acetabulum and femoral head. Due to anatomical patient variability, actual ranges of motion may be slightly different and the strength of the device may be changed.

Discussion

In conclusion, the new device offers demonstrable advantages compared to the external fixator, which is used in the current treatment of Perthes disease. It allows for more axes of motion, a lower likelihood of the chance of infection, a lower likelihood that bone fractures and microfractures are caused, and adjustable distraction that can done intraoperatively. In addition, it causes less nuisance to the child while treating Perthes disease, which is the ultimate objective.

The results from the various tests conducted determined that the device is capable of functioning as it was intended, achieving various degrees of motion – internal and external rotation and flexion and extension – and the ability for adjustment to accommodate for various sizes of patients. The device can withstand expected loads with a safety factor of 30%, resulting in the capability to withstand at least 1300 N (293 lbs.). This testing was done in a vacuum – without any muscles from the patients. With the inclusion of muscles, it is assumed that the device can handle more weight more

easily, since muscles may distribute the force around the body. Moreover, since Perthes disease affects many children, the device's components can be modular, to better fit different sized children. For example, it can be increased to fit an 18-year old or decreased to fit a 10-year old.

We have only developed a prototype of this device. Future studies on this device will have more extensive preclinical testing in vitro and in vivo. In addition, since Perthes disease is one of the more common hip disorders, this device could also provide suggestions toward the development of future, innovative medical devices that could be used to treat other, rarer hip disorders.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Harry Kim, Dr. Mikhail Samchukov, Dr. Alexander Cherkashin, Brad Niese, and Dr. Orlando Auciello for their guidance that they have contributed while working on the project. I would also like to thank the UT Dallas Machining Shop and Dr. Jean-Francois Veyan for fabricating the device. Finally, I would like to thank Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children for providing the funding for the project.

Team Members

Basil Alias

Emmanuel Aykara

Sarah Hassan

Amreek Saini

Shreyas Salvi

Hassan, Dr. Harry Kim

Not shown: Dr. Alexander Cherkashin, Dr. Orlando Auciello, Dr. Jean-Francois Veyan

References

[1] “Osseointegration.” Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/osseointegration.

[2] Gilligan, Ian, Supichya Chandraphak, and Pasuk Mahakkanukrauh. Journal of Anatomy. August 2013. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3724207/.

[3] Roaas, Asbjørn, and Gunnar B. J. Andersson. “Normal Range of Motion of the Hip, Knee and Ankle Joints in Male Subjects, 30–40 Years of Age.” Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 53, no. 2 (1982): 205-08. doi:10.3109/17453678208992202.

[4] “National Center for Health Statistics.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. August 24, 2001. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/html_ charts/wtage.htm.

[5] Young’s Modulus - Tensile and Yield Strength for Common Materials. Accessed April 14, 2018. https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/young-modulus-d_417.html.

21 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 22

Figure 11. Deformational analysis of device (stress)

Figure 12. Team and Scottish Rite staff Brad Niese, Dr. Mikhail Samchukov, Meghan Wassell, Emmanuel Aykara, Jayant Kurvari, Shreyas Salvi, Basil Alias, Amreek Saini, Sarah

Summer Fruit

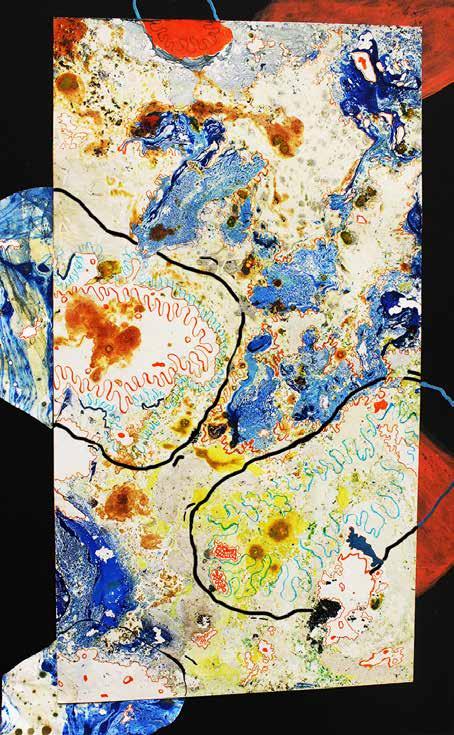

When I think of summer, bright, fresh fruit from the farmers’ market, sunshine and flowers come to my mind. I wanted to challenge myself to depict the feeling of warmth in summer while also experimenting with high-contrast shadows. I particularly limited my color palette to bright colors such as red, green and yellow. To get a sense of texture, I applied more pressure to the colored pencil for the waxy fruit, for a smoothing affect. For the softer textures, I allowed the blackness of the paper to show through, especially in areas of shadow.

My mentality while creating this piece was illustrating contrast in color, shape and texture. The sharp line of shadow along the windowsill leads the eye from the brightest area to the more organically shaped area in shadow. While shading, I wanted to give the illusion that the shadow wrapped around the fruit and flowers. I also used black pencil in a few areas to darken the parts in shadow even further. I included myself in the reflection of the glasses for more realism and to add dimension to the piece so that the viewer captures a part of the perspective they cannot see. I made the composition so that the objects would have heavy overlaps for further intricacy and dimension. So far, this has been one of my favorite pieces that I’ve made, and it has inspired me to continue using high-contrast shadow and detail in the rest of my work.

— by Izabella Dekhtyar

23 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 24

When written in poetry format broken down into stanzas, personal anecdotes gain a beautiful, halting quality. Maybe it reflects how a sentence broken down into lines parallels the hesitance of recounting a story that has influenced one’s personhood. Maybe it is just the fact that it adds an immersive yet detached element to the story that prose is incapable of replicating. Whatever the case may be, the format works particularly well for this anecdote.

During a long bus ride from Nuevo Laredo to Dallas, a man and his older mother told this anecdote to the man’s daughter. The man was trying to be gentle and comforting. Perhaps his boyhood memory was supposed to be a sweet story for his daughter to fall asleep to on the late journey. In any case, the anecdote, as anecdotes are wont to do, contained a lesson or two mostly about growing plants and being kind. As if that had not been endearing enough, his mother chimed in every so often, commenting on her reasoning behind the gardening lessons she had imparted. And maybe she was still trying to impart a lesson or two to her now-grown son.

Giving a title that reflects a work so focused on the personal growth of a stranger was difficult. Ultimately, it was the last thing I wrote as I tried to condense the gardening theme, the imparting of lessons from one generation to another and the increasing bits of wisdom that wove the story into a single concept.

— by Evelyn Alvarez

Growing Lessons

A child runs down the street screaming: “Mama!

Mama!”

A harried-looking woman, standing under the sturdy frame of a simple home, frowns down at the boy as he skids to a stop in front of her. Undeterred by her disapproval the boy looks up from underneath dark lashes, raises his arms, and the woman’s demeanor shifts as she looks down at what he holds cupped between two grubby hands: a plant. Dry, droopy, and brittle looking.

The woman, used as she is to her boy’s antics, takes a moment to sigh in exasperation before putting him to work (there is much to teach you mijo).

Small sun-kissed fingers, guided gently by bigger calloused ones, cautiously move the wilting plant to a little clay pot, where old dirt is mixed with new (remember that change is necessary mijo). And so the plant is tended to with diligence by the stubborn youth (your responsibility mijo).

A pail is hefted up by thin arms to water the plant once a day (boys and flowers both need water mijo).

The little pot migrates from window to window as the boy chases after Apollo’s chariot (this one likes sunlight mijo).

Soft words of encouragement are heard at all hours of the day (everything is deserving of love mijo).

And thus the little plant hangs on for days and weeks and months and years (lies are never kind mijo).

But mama, this is supposed to be a sweet little poem to encourage(be brave and be honest mijo). This is the truth: a little boy with dirty hands and too gentle a heart finds a plant on the brink of death. Unfortunately, despite his best efforts and tender care the plant dies (from time to time, life will break your heart mijo). That day the boy learns a most important lesson (not everything can be helped, not everything can be healed, a harsh yet inevitable truth mijo).

And the poor mother frets about the cruelty of the world until, after a long and frustrating trip, she comes home to a dusty child and windowsills full of little potted plants. See the lesson the boy had learned was not that of the futility of trying. Instead, he learned to pay closer attention to the things in his path.

So he kept an eye out for scraggly souls in need of a little extra dirt, water, and sun.

(Ay mijo, now our home always smells like wet earth and the soft fragrance of tenderly loved flowers blooming).

25 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 26

Geochemical Fingerprinting of Intermittent Low-Flux Leachate from the Austin Chalk in North Texas

Prominent iron (Fe)-rich leachate seeping into a North Texas stream (Spring Creek) led a local homeowner association (HOA) to be concerned for the safety of the residents in the area. The seep exhibited an iridescent sheen and an unpleasant odor, which led the HOA to speculate its source was an industrial origin. The stream's proximity to a commercial sausage factory and a waste-transfer station temporarily holding municipal solid waste (MSW) motivated that speculation. The HOA contacted the Department of Geosciences at The University of Texas at Dallas and Dr. Thomas Brikowski. After consultation, they filed an anonymous complaint with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

—

by

Jackie D. Horn

27 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 28

Introduction

In 2009, TCEQ assessed the discharge originating from the nearby MSW transfer facility. They sampled the water emerging from the stream bank and found elevated levels of arsenic (As) but determined that no major health concern were indicated as the levels were below the safe drinking limits (0.010 mg/L) established by the Environmental Protection Agencies (EPA) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Some years later, the HOA, dissatisfied with TCEQ results of 1.49 mg/L, reconnected with the university. Dr. Tom Brikowski observed a similar discharge from Rowlett Creek (in nearby Breckenridge Park) that appeared to resemble the Spring Creek occurrence, suggesting a widespread seepage. This research study intends to quantify the composition of these seeps, and if possible, identify any potential anthropogenic contributions.

Discharge Zones

The discharge zones analyzed in this study appear episodically along outcrops of Cretaceous Austin Chalk (Figure 1). The discharge zones encompass a 1- to 2-kilometer (km) exposure along the banks of Spring Creek in the North Dallas suburb of Richardson. Each area is 100-200 meters (m) in length, containing zones 3 to 10 m in length with concentrated flow. It is worth noting that the discharge is predominantly on the same bank (east) as the MSW transfer facility but oc-

curs both upstream and downstream of the MSW transfer facility.

A leachate zone defines an observation in the field showing the reddish-brown discharge. Leachate is emerging at the contact between the base of soil (calcium carbonate vertisol layer) and chalk bedrock2 The lateral extent of this iron (Fe)-rich leachate zone is 100 m and can exceed 200 m. The highest concentration of discharge is contained to a 1- to 2-m zone within a large 50-m zone around the spring orifice.

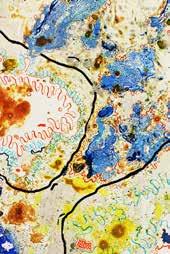

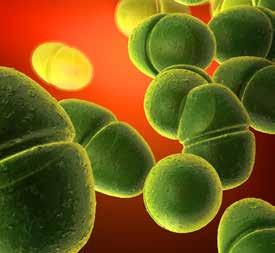

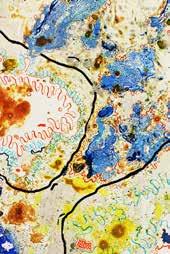

In North Texas, the Austin Chalk contains abundant iron sulfide (FeS) grains. These occur predominantly as pyrite throughout the formation. Meteoric and hydrologic processes that break down the chalk into clay minerals weather these sulfide grains of marcasite (FeS2) and pyrite (FeS2) into limonite —FeO(OH)·nH2O — along exposed fractures. The result is an orange stain on the rock outcrop marking the conduit pathway taken by the Fe-rich fluids2. When spatially concentrated, such staining and seepage can be particularly alarming to the public, who may suspect some kind of toxic spill or mining runoff. Soil microbes (Sulfur (S)-reducing bacteria) may produce volatile H2S that emit a rotten-egg odor as sulfate reduction occurs, and the byproducts of metabolic activity provide nutrients to algae and yield an iridescent sheen to the water surface.3

Austin Chalk, Fe-staining

Geologic Setting

The Austin Chalk (Kau) unconformably overlies the Eagle Ford (Kef) shale and has an unconformity contact by the Taylor Group (Figures 2A&B). It consists of recrystallized, fossiliferous interbedded chalks, chalky limestone and thin seams of marl. Volcanic ash layers (bentonites; aluminum phyllosilicate clay) are present in the chalk further south in Central Texas. They are assumed to be deposited by wind from distant erupting volcanoes around 86 million years ago (mya), and the presence of volcanism during deposition correlates with the Laramide orogeny (mountain building in western America). The trend of those long-ago submarine volcanoes is evident in present-day South-Cen-

emerging from the calcium carbonate layer or chalk. Note iridescent sheen in center suggesting organic substance, inferred to be from algal growth from the dissolution of iron sulfide (FeS2). Photo by Dr. Tom Brikowski.

tral Texas, which coincides with the Balcones Fault Zone. This formation is several hundred meters thick (100-120 m) and coincides with the maximum extent that the sea level rose during the Cretaceous Interior Seaway.

The Austin Chalk is primarily calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and has a grayish-white to medium-gray color. Microfossils of Coccolithophores, foraminifera and Inoceramus shells make up the bulk of the matrix. Minerals present in the chalk range from pyrite, marcasite, iron oxides (hematite –Fe2O3, α-Fe2O3) and maghemite (Fe2O3, γ-Fe2O3), and siderite (FeCO3)5. Most of the soils that formed over this chalk are calcareous, granular and crumbly (Figures 2A&B).

29 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 30

Figure 1. Locality map displays the leachate zones along Spring Creek in Richardson, Texas. Blue boxes indicate the potential anthropogenic sources of leachate (Owens Sausage Farm and Waste Transfer Facility). The green boxes indicate two parks in the area. Red circles show the sampling locations for the water-quality data over a two-year period.1

Figure 2. Panoramic view of field exposure of Fe-rich seepage at Sample Site B. Dr. Ignacio Pujana, is pictured, evaluating the strong sulfurous (H2S) odor emanating from leachate zone. His feet are on the exposed

Figure 2A. Top, Geologic stratigraphic column of East Texas modified from USGS survey team. Note: this study focused on the upper Austin Chalk and soil layers 4

had a blank of deionized water (DI), an anion and two cations (one cation not filtered). All samples were labeled and stored on ice in a cooler to keep reactions at a minimum. Samples were refrigerated in the lab until time of testing.

Temperature (°C), total dissolved solids (TDS), pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), specific conductivity (µS/cm) and turbidity (Nephelometric Turbidity Units [NTU]; HACH Model 2100P Turbidimeter) were collected at each site to determine local conditions, as well as from the sample sites prior to collection. Devices used to collect data consisted of YSI-85, TDS and pH probes (Low range Hanna TDS/pH/ meter) (Table 1).

The Taylor formation overlies Austin Chalk in the eastern part of the county. The members of this formation in the county are Taylor marl, Wolfe City sand and Pecan Gap chalk. Deep soils that formed over the chalk are in the Austin, Houston Black and Houston series6. Soil horizons are grayish in the subsoil, indicating reduction and transfer. Loss of Fe, a process called gleying, is evident in the poorly drained soils of the county7. Some horizons have mottles of yellowish red to brown or strong brown and concretions, indicating segregation of Fe.

Methods

This project incorporated water, soil and rock sampling to examine the nature of the discharge in the leachate zones. Samples were collected over a period of two years (20152017) and analyzed to determine the nature of the seeps. A handheld x-ray fluorescence analyzer (Niton XL3t) and spectrophotometer (HACH DR-1900) were used to analyze the dissolved major and minor elements present. Samples were collected using established best practices, standards, and guidelines from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), EPA and WHO.

All cation containers were prepared differently from the anions. Cations are preserved with 0.5 milliliter (mL) of nitric acid (HNO3) to bring the pH to less than two, whereas anion sample containers were devoid of HNO3. Collection of each sample was obtained at the spring orifice in the leachate zone with a 60-ml syringe equipped with a 0.45-micrometer (µm) tip to filter out colloids. A new syringe was used for each sample to decrease cross-contamination. Each site

Analysis of major element chemistry was via a HACH DR1900 spectrophotometer and standard methods were used for each anion or cation, with ppm precision. Anions tested for ammonia (NH3), bromine (Br) and chlorine (Cl) and cations consisted of barium (Ba), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), Fe and zinc (Zn). Before measuring each sample, the sample cells (10mL) were wiped with a Kimwipe™. All test samples were allowed to reach room temperature prior to the measurements of cation and anion contents. The measurements of cation and anion contents were performed in duplicate (Table 2)

Fe precipitate and clay samples in the discharge zone were scanned primarily for trace elements with a handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer. To obtain the precipitate, two 2-liter (L) bottles were collected using the same process as described above. Samples were dried at 100 degrees Celsius for 24 hours to slowly evaporate the water from the sample. A portion of the Fe precipitate powder was crushed in a mortar and pestle to be uniform size for a laboratory XRF. Powder was placed into a petri dish with a cov-

er for storage at room temperature. Fe powder was pressed into a pellet container for a scan with XRF. The pellet was covered with a 4-µm carbon thin film and then placed into a sealed scanning apparatus. A scan of the sample’s center was run for 90 seconds (s). The sample was run at 10, 25 and 40 kiloelectron volts (keV). Clay samples were run the same way but were left to dry out at room temperature. All data recorded are shown in the spectra graph (Figures 3 and 4)

31 The Exley Spring 2024 Spring 2024 The Exley 32

Table 1. YSI data collected from Spring Creek at each sampling area

Table 2. Data from the three sites collected in Spring Creek. Data shows the average of the data for each site.

Spring Creek Stream Data YSI-85 DO (mg/L) DO% Speci c Conduct (µS/cm) TDS (mg/L) Temperature (Cº) A 9.44 105.1 0.618 402 20.5 B 9.8 110.4 0.613 398.4 21.1 C 9.89 111.2 0.369 240.2 21.1

Data for Spring Creek Discharge Anion/Cation Ammonia Bromine Chlorine Barium Calcium Magnesium Iron Zinc A (mg/L) 0.24 1.08 32 10 0.37 0.34 0.05 0.18 B (mg/L) 0.33 1.18 35 14 0.46 0.37 0.06 0.18 B (mg/L) 0.46 0.88 58 15 0.49 0.40 0.04 0.18

Figure 2B Soil Horizons; O is the topsoil, which is a Houston Blackland Prairie; Ag is an Austin silty clay; Rr is a fractured chalk and R is Austin Chalk bedrock.

Geochemical

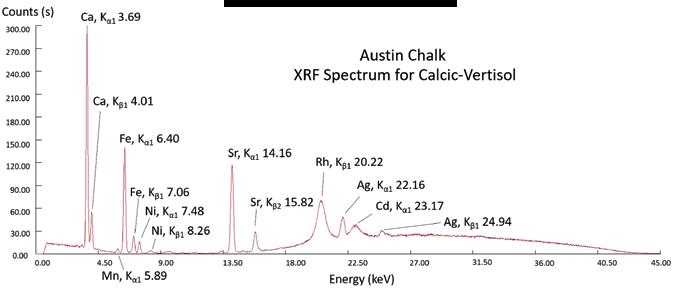

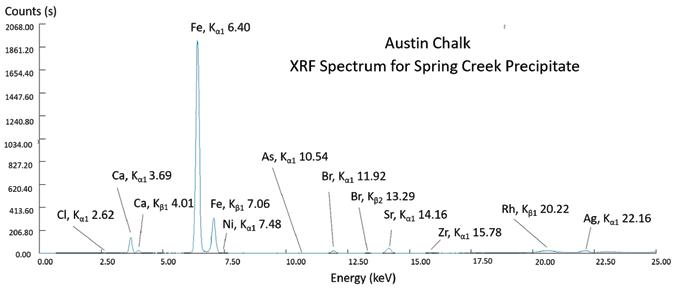

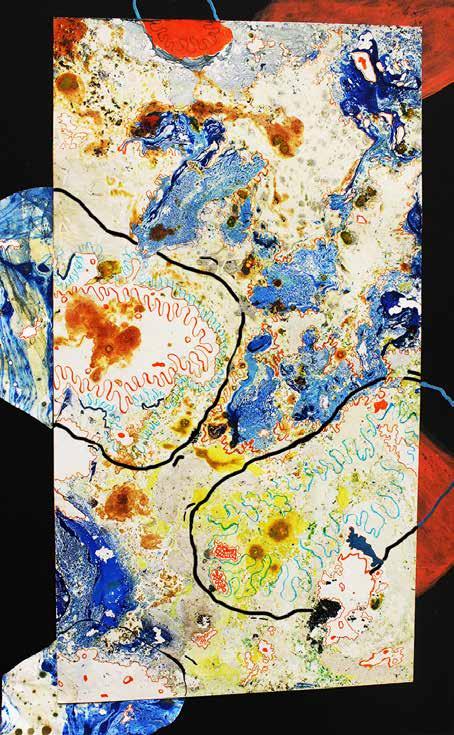

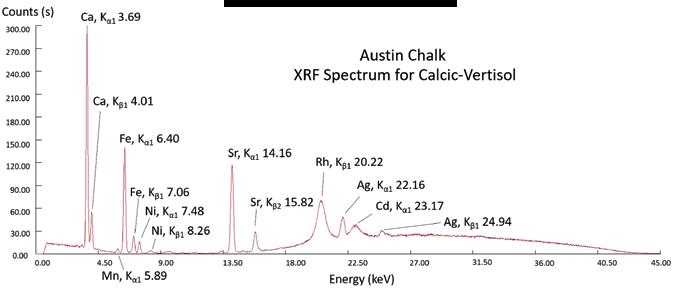

Figure 3 Composite of the data collected for the calcic vertisol clay at sample point B.

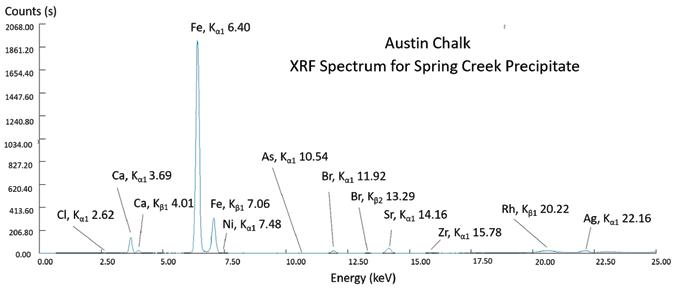

Figure 4. Composite of the Fe rich precipitate discharged from Spring Creek at sample point B. Note that Fe peak is considerably larger than calcic vertisol in Figure 3 and the presences of As.

Results