Rebecca Andersen

Sara Dant

By William T. Parry

Rebecca Andersen

Sara Dant

By William T. Parry

Laurie J. Bryant

Laurie J. Bryant

Rebecca Andersen

Sara Dant

By William T. Parry

Rebecca Andersen

Sara Dant

By William T. Parry

Laurie J. Bryant

Laurie J. Bryant

165 Reconstruction and Mormon America

Edited by Clyde A. Milner II and Brian Q. CannonReviewed by Reilly Ben Hatch

166 Carbon County, USA Miners for Democracy in Utah and the West

By Christian WrightReviewed by Nichelle Frank

167 Traditional Navajo Teachings A Trilogy

By Robert S. McPherson andPerry J. Robinson

Reviewed by Ronald P. Maldonado

169 The Last Canyon Voyage A Filmmaker’s Journey Down the Green and Colorado Rivers

By Charles EggertReviewed by Christian Filbrun

On summer evenings, LeGrande Davies and his grandfather Otto Kesler loved to sit outside their Cove Fort home and watch the sunset, while a group of coyotes began its serenade. Davies recalled that “‘Grandpa would always say, “Ah. Can’t they sing well. Can’t they sing well.” There was a peacefulness that would come because the wind quits blowing in the evening.’” So notes Rebecca Andersen in the opening article of the spring 2022 Utah Historical Quarterly, which focuses on land in the Intermountain West and a handful of the entities—whether personal, familial, or corporate—that have made a living off it. The action in this issue takes place mainly in Utah but also in Nevada, Wyoming, and other neighboring states, on the traditional homelands of Indigenous tribes, a testament to the reality that watersheds, economies, and interpersonal networks do not always adhere to neat political boundaries.

In 1903, William Henry Kesler moved his family to Cove Fort. Ira N. Hinckley had built the fort, located in Millard County at an elevation of some six thousand feet, in 1867. By the time Kesler arrived, it was almost a ruin. But over the course of the twentieth century, generations of Keslers renovated and cared for Cove Fort and the land it occupied, using it as a ranch, way station, and destination for tourists. Drawing from oral histories, Andersen contextualizes the Keslers’ experience within the broader changes of the twentieth century as the family “fought to maintain sense of autonomy, a way of life and understanding of the past that shaped their identity and relationship to the land.”

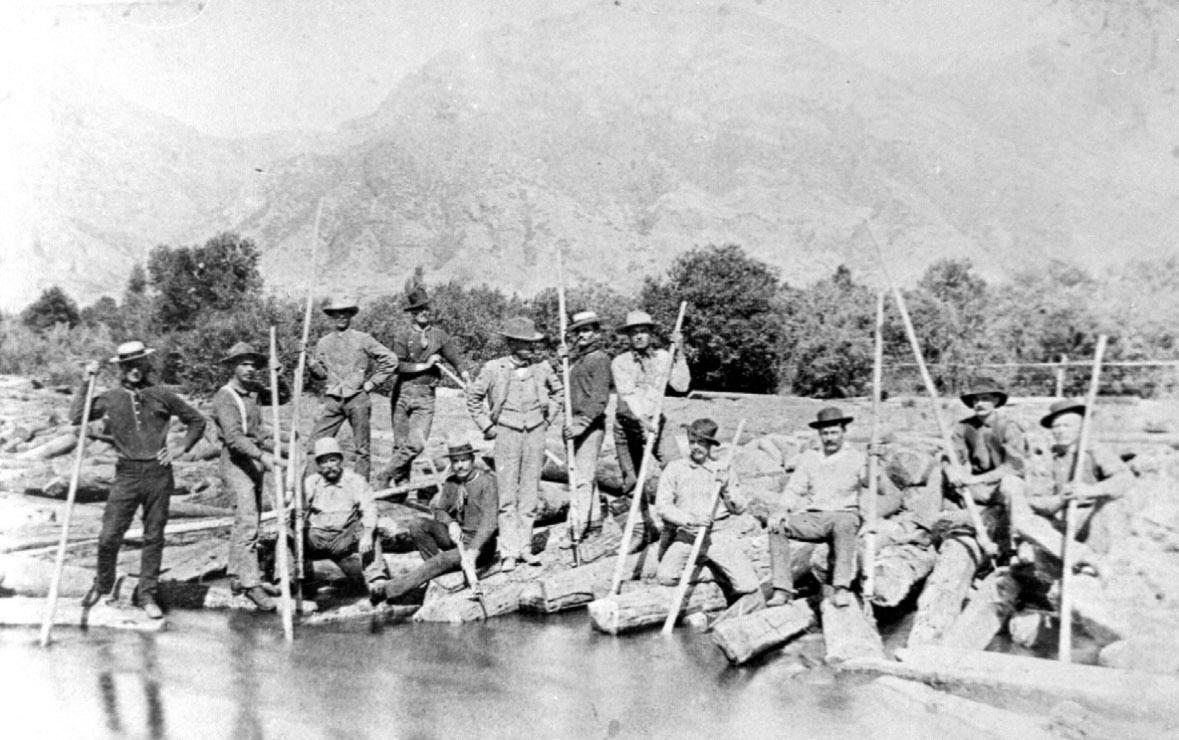

Next, Sara Dant presents an extensively researched history of log drives along the Weber River and other waterways. A regional market for timber grew in the final decades of the nineteenth century, stimulated in large part by the development of railroads and mines. Entrepreneurs in Utah and elsewhere answered this demand by cutting thousands of trees in mountain forests and driving the hewn logs down river to

their next destination. As Dant observes, “In the arid West, water is the essential element,” providing both sustenance and “highways of timber commerce and trade.” This financially significant industry also had a negative impact on the region’s forests and waterways, a fact that was observed by Albert Potter, Reed Smoot, and others.

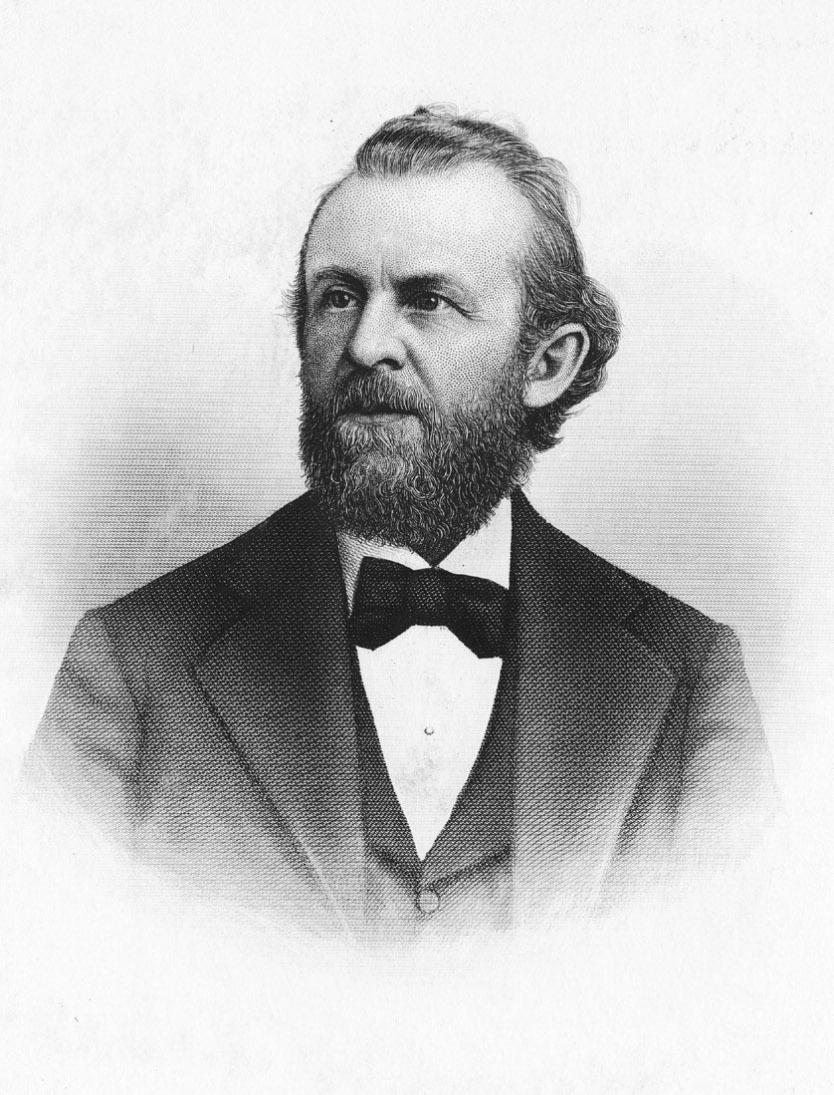

Our third article continues the theme of regional resource extraction with William Parry’s account of William S. Godbe’s mining activities. From the 1860s onward, Godbe and his eight sons were deeply involved in the mineral development of Utah and Nevada. The Godbe men opened mines, combed through tailings, founded companies, created new chemical processes, and much more in their search for mineral wealth. In these endeavors, they met with only partial success and, unfortunately, damaged their own health and, presumably, the health of their employees and the land.

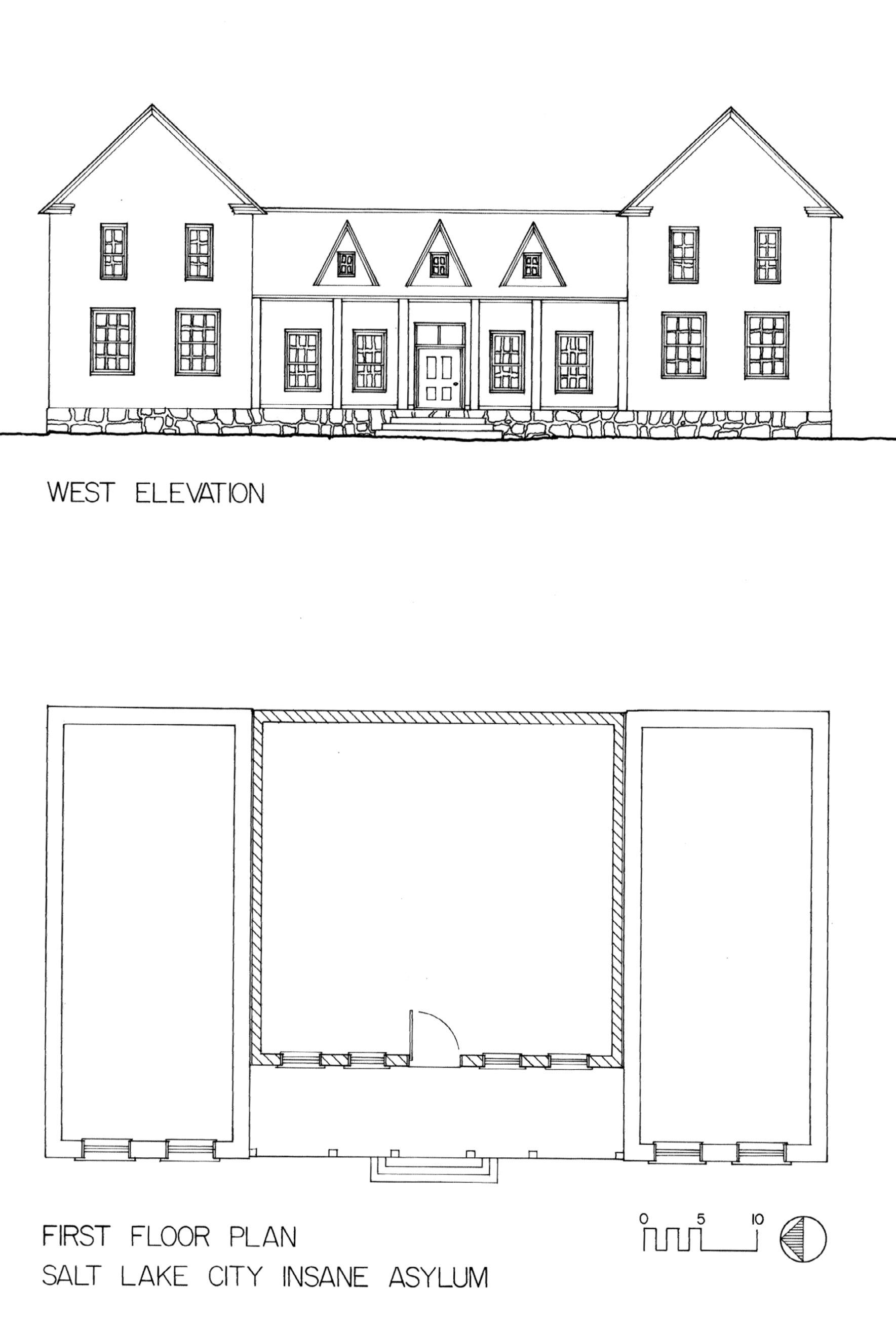

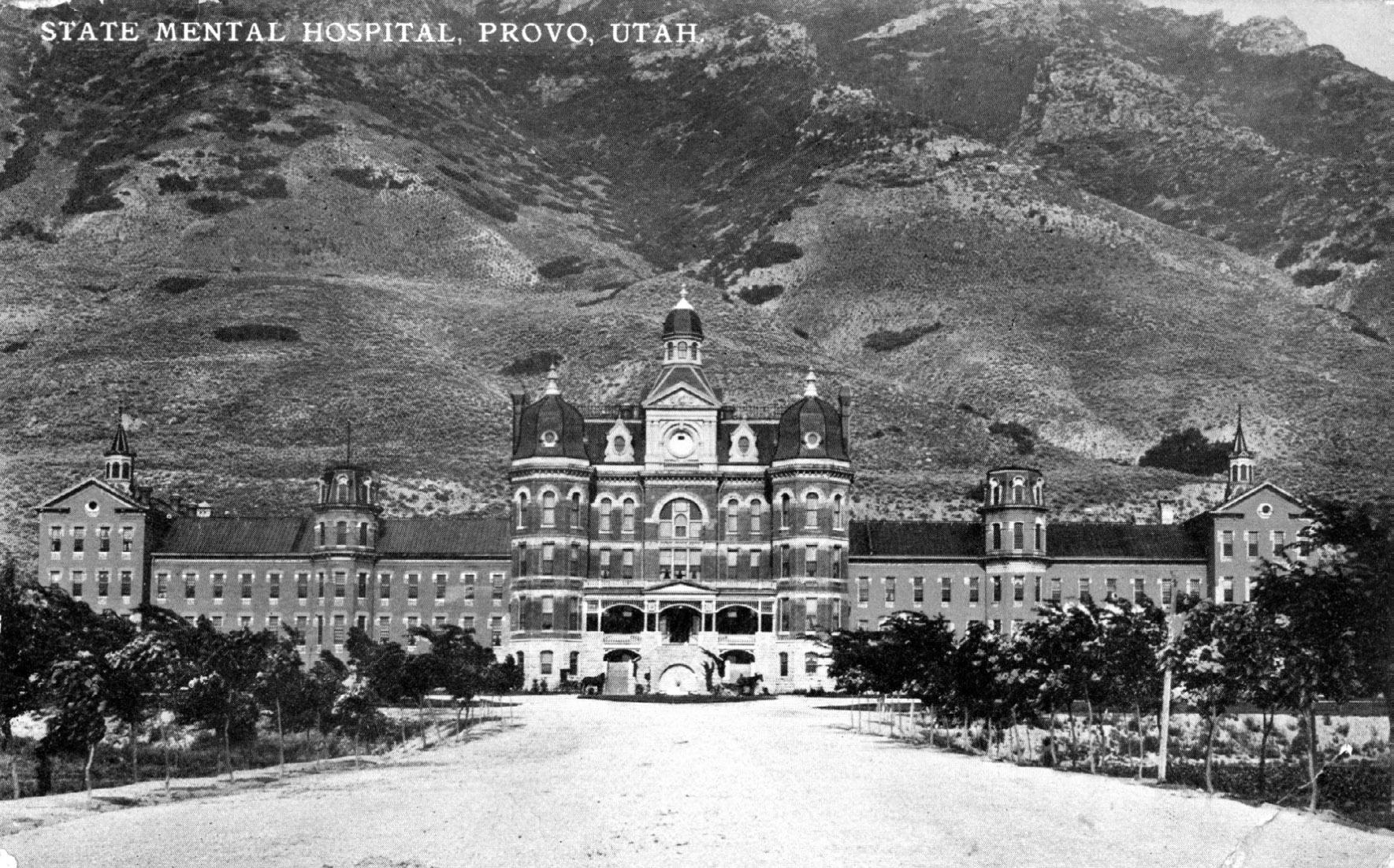

Laurie Bryant rounds out the issue with an article that pieces together the history of Utah’s first hospital for the mentally ill: an institution run both publicly and privately that had a decidedly rocky career and became part of the religious and cultural tensions that were so present in late-nineteenth-century Salt Lake City. In reconstructing a history of the asylum, Bryant also pays tribute to its patients—people who endured much and yet whose lives were infinitely valuable.

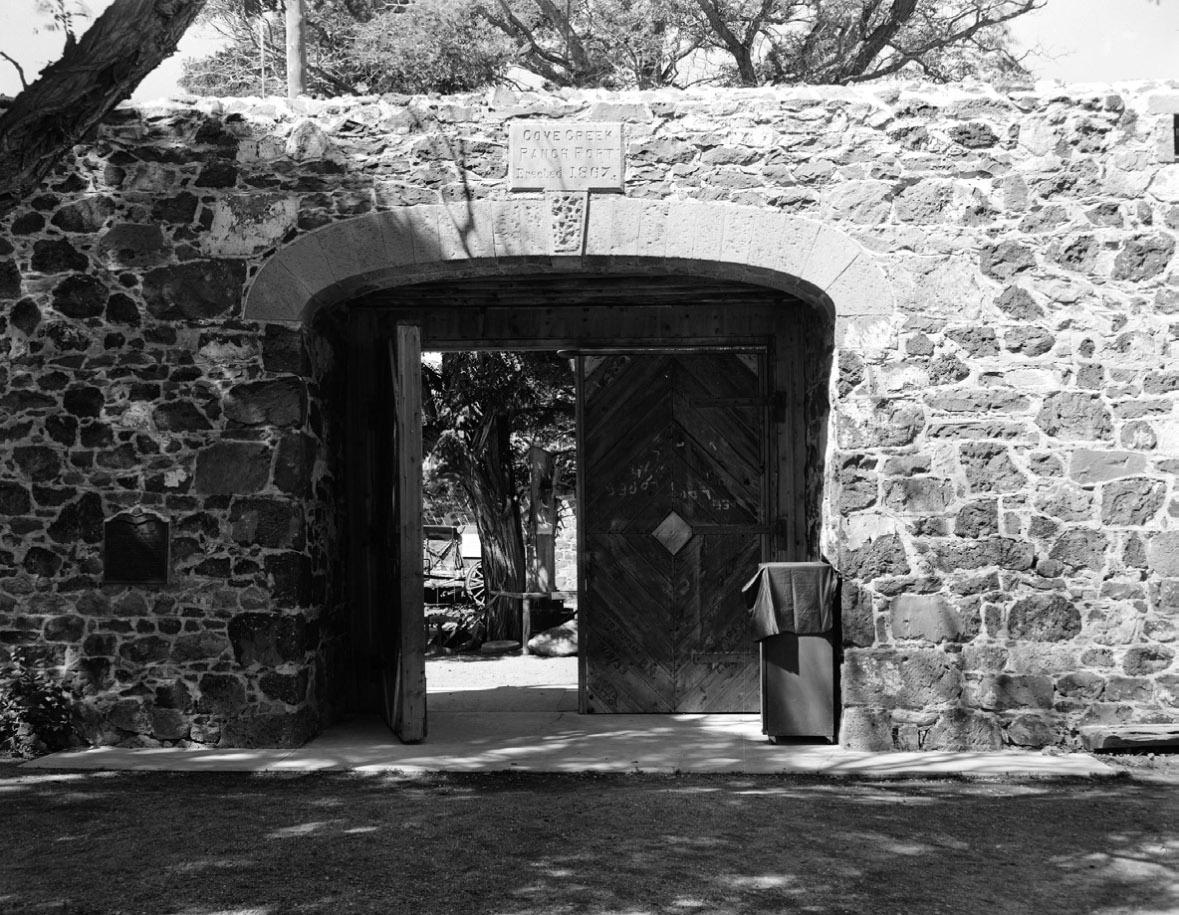

At an elevation of 6,000 feet, Cove Fort, Utah, is a zone of physical and cultural transitions, a land of extremes.1 In the summer, daytime temperatures can soar over a hundred degrees Fahrenheit before plummeting at nightfall. A frost visits every month of the year. Winters are especially harsh. It is not uncommon for temperatures to register twenty, even thirty, degrees below zero. The wind blows constantly, pausing only at sunset, leaving the air breathless and suspended.2 There is water, but it is locked deep underground, reachable only by machine-drilled wells. Any surface water comes from snow melt that trickles down mountain draws and canyons from the east. By mid-May, sometimes early April, these sources run dry. Like much of the Great Basin, Cove Fort country is affected by eastward moving Pacific storm systems. The Sierra Nevada trap most of the moisture from these systems; the north–south running mountain ranges that fold and ripple across the Great Basin catch what is left.3 The grasslands and meadows that initially attracted Mormon herdsmen exist in delicate balance, reliant upon this seasonal flow. Overgrazing attracts sagebrush and cedar, which suck away the runoff and choke future germination and growth.4 Situated on the west side of Highway 91, Cove Fort stands apart, like a sentinel over the small valley entrusted to its care. The fort’s thick rock walls are rooted to the land as if they were some hardened, volcanic outcrop. Giant black locusts tower over them, their branches reaching like fingers to the sky, pitching and swaying in a rhythm all their own.

Since the mid-1990s the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has operated Cove Fort as a church historic site where visitors encounter a narrative that emphasizes the faith and sacrifice of Mormon pioneers in settling and colonizing a difficult land. They learn that in 1867 Brigham Young called Ira N. Hinckley to be in charge of the construction of what became officially known as Cove Creek Ranch Fort, or Cove Fort. The fort was to be part of a larger network of such structures built in response to Utah’s Black Hawk War. Two years earlier, an altercation between Mormons and Ute tribal leaders in the town of Manti plunged the region into a series of violent, internecine conflicts. A formal peace treaty was

not reached until early 1868, and it ultimately resulted in the removal of the Ute peoples onto reservation lands far to the northeast. The history recounted at Cove Fort pointedly emphasizes that although the fort was constructed for defensive purposes, it was never attacked. Instead, Hinckley and members of his family lived and operated it as a ranch and way station from 1868 until the early 1880s, when the newly completed Utah Central Railroad significantly reduced overland traffic and lessened the need for a formal way station in the area. By 1890, church website material relates, the Hinckleys had left Cove Fort for good and the church leased the land to others.5

Historic site interpretation is admittedly challenging. Remembering and forgetting occur simultaneously as one historical narrative replaces or suppresses another, creating what the anthropologist and historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot famously termed the “silences of the past.”6 Understandably, the church’s acquisition of Cove Fort, its restoration, and ultimate interpretive strategy most likely stem from the fact that Ira N. Hinckley was grandfather to the then-president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Gordon B. Hinckley. As a result of these choices, Cove Fort’s historic significance is unfortunately obscured. Little mention is made of the family members who helped build the fort or, more notably, the site’s difficult history, constructed as it was during one of

the West’s most significant yet little researched or understood Native-settler conflicts. Moreover, this narrow interpretive strategy ignores Cove Fort’s later history as both a home for the William Henry and Otto Kesler families and as a stopover for countless automobilists traveling along Highway 91. Indeed, Cove Fort existed as a base for the Kesler family’s expanding ranching operations and as a minor tourist attraction far longer than it did under the care of Hinkley or anyone else.

It is Cove Fort’s twentieth-century history as a ranch and service station that I relate here. In doing so, I contextualize this history within existing literature on tourism in the West and explore how the Keslers creatively managed the land while capitalizing on the fort’s distinctive heritage and its location along Highway 91, one of Utah’s busiest thoroughfares before the coming of the interstate. The Keslers’ management of Cove Fort speaks to the way in which tourist destinations impacted everyday life on the periphery. Locals like the Keslers adapted to and even benefited from changing times. They also fought to maintain a sense of autonomy, a way of life and understanding of the past that shaped their identity and relationship to the land. As Hal Rothman observed, places have identities: “Human-shaped places, cities and national parks, marinas and farms, closely guard their identities. Their people are located within them in ways that create not

only national, regional, and local affiliation but also a powerful sense of self and place in the world.”7 In a sense, the Kesler family’s historic ties to Cove Fort is Rothman’s thesis in microcosm. For most of Cove Fort’s history, the Keslers called it home. They lived in the fort and worked the land to make it productive for livestock, developing an intense connection with the place that remains to this day. It was only when others threatened to remove the Keslers from Cove Fort that the family worked to make the site more accessible to passing travelers, finally turning the fort into a museum in the early 1960s. As the gatekeepers to Cove Fort’s history, the Kesler family’s experiences illustrate the politics of preservation: what gets preserved and why, along with how historical narratives are created and shaped.

In relating this narrative, I rely extensively on oral history. Larry Porter first interviewed Otto Kesler in 1964 while researching his master’s thesis, the only scholarship on Cove Fort currently available. It is clear from these interviews that Porter hoped Kesler could tell him more about Cove Fort’s early history, original layout, and outbuildings. Kesler did this and more. Fortunately, Porter provided the Kesler family with a recorded copy of this interview, which I obtained and then transcribed. Porter’s interview is priceless, and I make liberal use of it here. It captures Kesler’s rare ability to call a history into existence through the rhythm and artistry of his words. More recently, I sat down with Otto’s grandson, LeGrande Kesler Davies, and conducted additional interviews. Davies grew up at Cove Fort in the 1950s and early 1960s during a crucial time when the family nearly lost the fort to the state of Utah. Like those of his grandfather, Davies’s stories communicate a deep love for the fort, its history, and the land.8

In this case, not only does oral history represent an important source material when written or other documentary evidence is lacking, it also allows readers to hear about Cove Fort from the primary guardians of that memory, Otto Kesler and LeGrande Davies. As Alessandro Portelli wrote, “Oral sources tell us not just what people did, but what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did.” Oral history, Portelli emphasized, “tells us less about events than

about their meaning.”9 Through the Kesler and Davies interviews, Cove Fort emerges as a physical metanarrative, situating the family within nineteenth-century Mormon colonization traditions that saw settlement in terms of covenant, beautification, and redemption. For analytical purposes, I have organized my source material into five sections that follow a rough chronological framework of the Kesler family’s history at Cove Fort: arrival, early tourist activity, Otto Kesler and ranch life at Cove Fort, renovation, and the transfer of Cove Fort ownership back to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Larry Porter began his interview with Otto Kesler by asking about the arrival of Otto’s father, William Henry Kesler, to Cove Fort in 1903. Several important themes emerge from Kesler’s retelling of this history: first, by the early 1900s, Cove Fort was in near ruin and that without the arrival of the Keslers, it certainly would have only deteriorated further; second, while William Henry Kesler saw Cove Fort as a home for his family, he was aware early on

of the site’s significance and hoped to preserve its history. Incidentally, these themes were also present in my interview with LeGrande Davies, suggesting a significant correlation between the two versions. Davies contributed further detail to the William Henry story, most of which he likely learned from his grandfather, Otto Kesler. This additional information speaks to William Henry’s inventiveness and ability to create a life for his family at Cove Fort. Finally, Otto recalled a Native American presence at Cove Fort that persisted through the twentieth century. The Kesler family’s interactions with Native Americans seem to have occurred in a quiet, almost subtle way. Yet as will be discussed in greater detail later, tropes from the mythic Old West undoubtedly influenced how visitors stopping for gasoline and a quick tour experienced Cove Fort’s history.

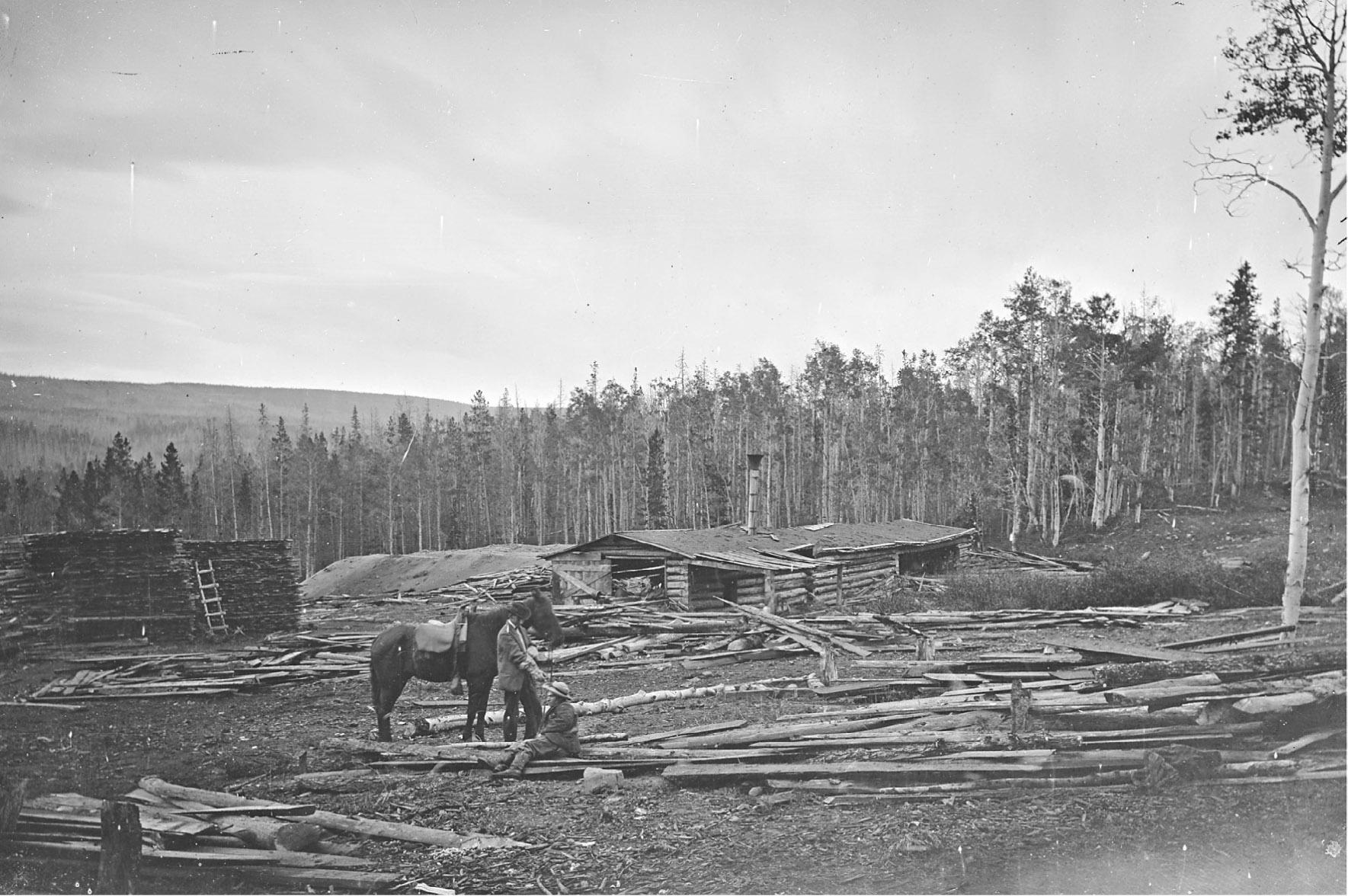

Otto Kesler explained to Porter that after the Hinckleys moved away from Cove Fort, the church leased the fort to a number of individuals. A fire caused by one of the tenants destroyed Cove Fort’s north side, leaving the fort unoccupied and virtually unlivable. Previous tenants and campers had used the surviving south side to stable horses and cows.10 “You can imagine what a place, how it goes when nobody’s lived around there for two or three years,” Otto observed in the interview.11 It was in these conditions—a charred, broken wreck—that William Henry Kesler found Cove Fort in June 1903. Kesler and some other men from Beaver, Utah, stayed briefly at the fort that summer on their way to Kimberly, Utah, where they had a contract to cut and deliver cord wood for mines.

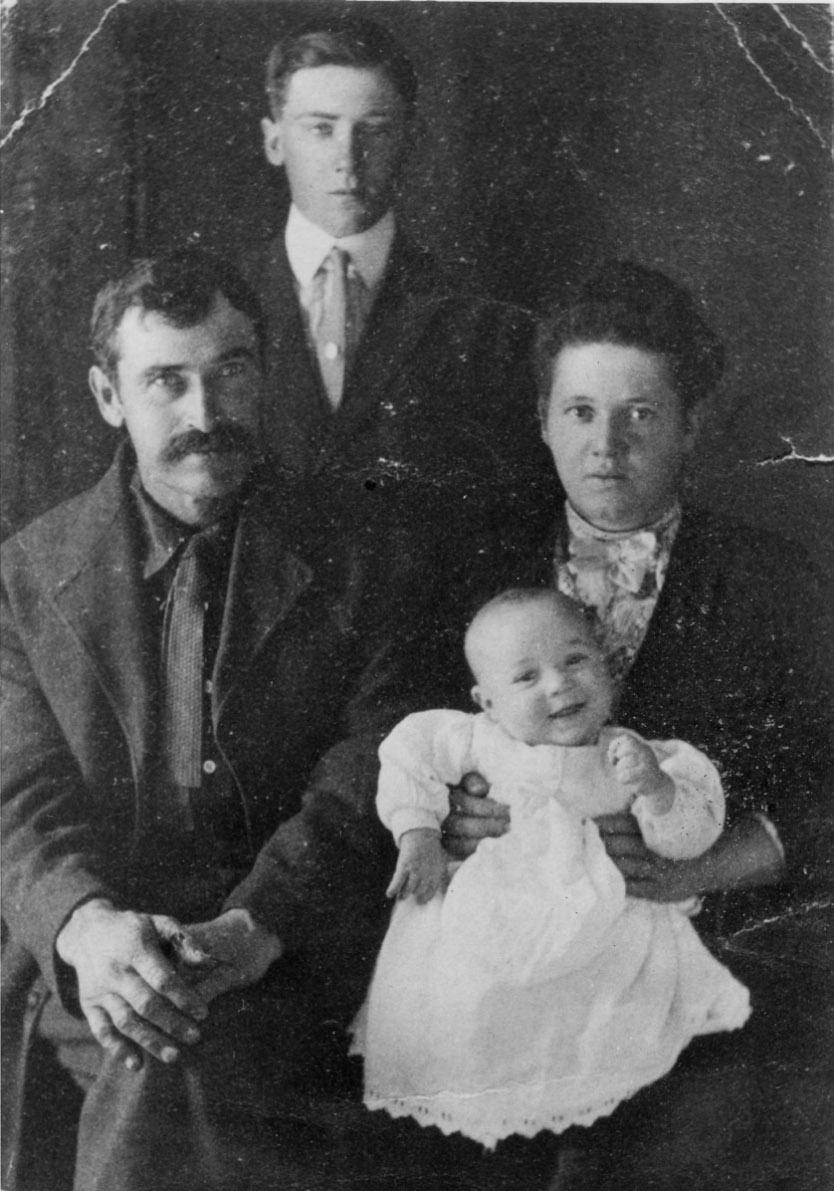

Born in Saint Thomas, Nevada, to Joseph and Anne Pitts Kesler in 1868, William Henry was a month shy of his thirty-sixth birthday. As Davies observed in his interview, William Henry’s life had not been an easy one. Kesler married his first wife, Annie Edwards, in 1893. She died nine months later, shortly after giving birth to their first child. He married again in 1894 to Sarah Adeline Losee. Babies came quickly and, by 1903, their family had grown to include four children.12 William Henry led a hardscrabble life, picking up work where he could find it.13 He undoubtedly saw Cove Fort and the surrounding land as an opportunity to at last settle and create a stable life for himself and his growing family.

Once the contract with the Kimberly mines was completed, William Henry made a trip to Salt Lake City to inquire about leasing Cove Fort from the church in December 1903. Successful in this endeavor, Kesler spent the early spring of 1904 making the fort habitable. On April 25, 1904, shortly after Sarah had given birth to their fifth child, the Keslers moved from their home in Beaver to Cove Fort. Nineyear-old Otto remembered the day well. He and his younger brother Ferrell rode horses and pushed cows. William Henry drove a wagon loaded with furniture and supplies. When the young family crested Pine Creek Hill, they paused momentarily in the afternoon sun as William Henry pointed out Cove Fort, far off in the distance. “It seemed like it took us a long while to get from the top of that hill over that draw with those slow cows.”14

According to Otto Kesler, when the family first arrived, some alfalfa still grew sporadically in the fields east of Cove Fort, across the wagon road. William Henry replanted this field in alfalfa or “young Lucerne,” restoring it to “hay ground.” Otto clarified, “On the west side [of Cove Fort], he got that back into hay again. . . . But the first he got into hay was on the east side of the road—the twelve acres on the east side.” William Henry also planted apple trees, English currants, and gooseberries.15 The Keslers made ready use of Cove Fort’s existing outbuildings and structures. The original round corral served the family well into the 1930s; the barn remained in use until the state widened Highway 91 in the early 1940s.16 Otto indicated that plans for the widened road ran near where the barn sat, necessitating its removal. By that time, however, the barn was too old to be of much use. “It’d leak so much . . . and the timber’s getting old and that, it was getting kind of dangerous—these big winds, it was pretty hard on it.”17 Otto remembered the barn’s four windows nestled high under each gable, a perfect vantage point from which to see the small valley in its entirety. “You could look east and you’d look north and west and south.”18 During this time the fort also became a switchboard for the first telephone line between Beaver and the rest of Millard County. For power, William Henry rigged a direct current wind generator on Cove Fort’s south wall. The Keslers also used a gasoline generator until 1941, when the

family dug and installed power poles and connected their own line with Telluride Power Company to the east in Richfield.19

William Henry Kesler continued to lease Cove Fort until 1911, when he convinced the church to sell it to him outright. He paid $8,500 for it and eight hundred surrounding acres but did not obtain a clear title until 1919.20 Initially the family lived in the fort’s south side until 1917, when Kesler was able to hire brothers Martin Henry Hanson and Lorenzo (Ren) Hanson from Fillmore to help him rebuild the burnedout north side.21 Otto emphasized,

My father had [the north side] rebuilt . . . because he always said that . . . there’d be a time coming when that fort would be worth more than the whole ranch because he wanted to restore it and maintain it so’s it would stand for generations to come for people to see. He knew that there’d been nearly a hundred forts built in the territory of Utah . . . and they were about diminished and destroyed by that time. . So that is one reason for him to build the north side up just like it was and to maintain it and take care of it like he did.22

For at least the first few years, it appears the family all lived at Cove Fort year round. Birth information suggests that between 1907 and 1911, three of William Henry and Sarah Adeline’s eleven children were born at Cove Fort.

The remaining children were born either in Kanosh or Fillmore.23 Oral history testimony from Otto Kesler bears this out. Otto notes that William Henry hired a teacher for his children during the wintertime. This continued until Otto was in the seventh grade, when he attended school in Beaver, eventually graduating from Murdoch Academy.24 According to LeGrande Davies, Otto also attended some primary grades in Kanosh, staying with families there during the week and then riding home to Cove Fort on Friday night. William Henry Kesler eventually purchased a home in Fillmore and at least for part of the year mother and children lived there.25

The land produced well as long as the Keslers could get water to it and the growing season cooperated. My interview with LeGrande Davies highlights William Henry Kesler’s ingenuity and creativity. William Henry rerouted Cove Creek and created irrigation ditches by using a bowl of water as a leveler. He walked slowly and carefully over the land, gaging the grade by how the water tilted and lapped at the bowl’s edge. The ditches he cut curved like snakes, but with them the family was able to irrigate between 180 to 360 acres, generally alfalfa. Kesler also diverted some of the water from Cove Creek so that it ran through the fort’s east gate via a pipe with a filter box full of sand, gravel, and charcoal. The water then collected into a cistern dug into the center of the courtyard. He kept the water fresh by adding lime and by periodically scouring the cistern. Drinking water, however, came from a seep spring about a mile-and-a-half east of the

fort. Water from the spring had to be hauled by wagon in barrels until the 1930s, when the family installed old steam piping from the mines in Kimberly to bring potable water into the fort.26 This proved to be only a partial solution, however, as the pipe often froze. Finally, around 1960 the Keslers improved a well, dug in the 1930s east of the fort, and installed a submersible pump and plastic pipes, buried deep underground to prevent freezing.27

The Keslers were also conscious of the local Native American population and their connection to Cove Fort. Otto remembered that bands often traveled through the area and camped near the fort. “They used to get these elderberries . . . in the fall here and get the juice out of them.” Other times bands passed through on their way to Indian Peaks to gather pine nuts. “The Cedar Indians used to come over to Kanosh and they had big celebrations. . . . And that’s how we’d get to see quite a few of them there at the crossroads.” Although Otto stated that his parents generously provided these travelers with food and feed for their livestock, the Indians scared him. “I had heard so many stories about them, you know.” Despite his fears, he was obviously curious and observed their camps closely, watching as band members cooked rabbit meat in a traditional way and baked bread using skillets. One frequent traveler through the area was a Pahvant man known as Hunkup. Hunkup was well known to the white community; every once in a while, a newspaper article mentioned his activities, often describing him in disparaging and racialized terms.28 Full of youthful bravado, Otto once approached Hunkup while he was camping at Cove Fort. “He had his little fire and getting his dinner and I says to him, I felt pretty big, I says to him, ‘Hunkup, you used to be pretty mean to the white men, didn’t you? You Indians.’ ‘Ah,’ he says, ‘lad, you don’t know what you’re talking about.’ He says, ‘White man used to be pretty bad [to] Indian, too.’ So that started me to thinking that maybe the white men was about as bad as they was.”29

Although Hunkup successfully challenged Otto’s assumptions in a way he never forgot, for modern readers, this story may contain troubling elements. In retelling the incident, Otto only conceded that Euro-American settlers were “about as bad” as Native Americans. More may be at play here, however. In one short

retelling, Kesler ably communicated the long and difficult relationship that formed between Mormon pioneer settlers and the Indigenous people of central Utah. The memory these interactions left on both peoples is palpably present in this experience. Earlier in his narrative, Otto remarked that he feared Indians because of the stories he had heard about them. He did not elaborate on the kind or nature of these stories. Were these popular stories about the mythic Old West or ones about the Black Hawk War passed on to him from trusted adults? As Paul Reeve observed, messaging from church leaders cast neighboring Paiute bands within enduring Book of Mormon narratives. As Lamanites, the thinking went, Paiutes were members of the House of Israel, who needed reclaiming. At the same time, some believed Paiutes descended from the Book of Mormon group the Gadianton Robbers, making them a feared and dangerous people. Yet even during the Black Hawk War, military action was sometimes offset by overtures of peace. As Reeve explained, by the century’s end, power dynamics undeniably favored Mormon settlers. Yet at the same time, the Paiutes had become integrated into Mormon frontier life in ways that insured a significant degree of familiarity between the two peoples, something Otto Kesler’s exchange with Hunkup bears out.30 Otto’s relationship with Paiutes continued into adulthood, when he both employed them at Cove Fort and purchased their handmade deerskin gloves to sell in his store.

By the 1920s, a heightened interest existed nationwide in relating and preserving the frontier experiences of white, northern European pioneer settlers. The historian John Bodnar attributed this awareness to revolutionary social changes that transpired during the first decades of the twentieth century. People adapted to these changes by creating a historical narrative that established and strengthened a cohesive community identity. “The heroes of their cultural construction were not signers of the Declaration of Independence but ordinary people. They were the ‘pioneers’ who first settled the prairie.” Across the Midwest, for instance, Old Settler Associations formed, sponsoring picnics and other events designed to commemorate those who came before. Bodnar explained that these societies glorified Euro-American pioneers as “nation builders, conservators of

tradition, and models of survival during difficult times.” Moreover, the conquered land itself became an important physical witness to the pioneers’ hardy ingenuity and resolve.31 In Utah this drive manifested itself in the founding of the Daughters and Sons of Utah Pioneers, organized in 1925 and 1928 respectively. These groups set out to gather histories and otherwise memorialize events and places significant to the Mormon pioneer experience.32

Further afield, automobile clubs and other local boosters lobbied for better roads in the hopes of building Utah’s nascent tourism industry. They dubbed the highway that passed in front of Cove Fort the “Arrowhead Trail,” one of several main routes to southern Utah’s splendors.33 This phenomenon was not unique to Utah. By the early twentieth century, an emerging automobile culture accompanied by a growth in leisure time largely replaced elaborate railroad tours and exclusive wilderness retreats for the wealthy. Targeted boosterism established the West as the nation’s playground in the form of national parks and resort towns. History, or at least the mythic variety, became a selling point, celebrating Euro-American conquest in starkly racialized terms.34 Knott’s Berry Farm, for instance, originated as a berry stand during the 1930s where Cordelia Knott treated travelers to her famous chicken dinners as a way to make extra money. In 1940, her husband Walter purchased the Mojave Desert ghost town of Calico and resituated it in Buena Park. A decade or so later the new “mining town” had evolved into a a 40-acre Old West theme park.35

Not unlike Walter Knott, although on a much lesser scale, William Henry Kesler also

capitalized on automobile traffic and promoted Cove Fort as a historic site. Although it is not known when these efforts began, an October 1916 Salt Lake Tribune article alerted travelers that they could find a “telephone, gas and oil” at the fort. The short blurb continued, “Note— This is one of the pioneer monuments of Utah, built by Brigham Young as a protection against the Indians. It is worthwhile to stop and examine.”36 Frank Beckwith, owner of the Millard County Chronicle and an important booster for the area, took an interest in the region’s local history.37 In an article for the Improvement Era, Beckwith recalled dropping in at Cove Fort for a drink and hearing about the fort’s history, presumably from William Henry’s wife, Sarah. “What a fine, wholesome, quiet air the old place had!” he recalled. “There was a wash on the line within, a peep of which I had through the open doorway, lending it a really homey background. And better yet . . . two innocent little lambs, just learning the use of those wobbly legs of theirs, emerged timidly through the big portal.” Beckwith learned the fort had been built in 1867 under the direction of Ira N. Hinckley as a protection against Indians but was never attacked. “I listened with interest to her recital that the place was used for years as a stage station in the long ago; also that boy riders carried mail from Beaver to Fillmore, stopping there for change of mount.” Beckwith added, “To linger was a pleasure.”38

The family initially pumped gas from fifty-gallon barrels, which they hauled from the railroad station at Black Rock. Eventually they installed an underground tank and hand pump along with a makeshift concession stand next to the fort. (Later, Otto Kesler operated a store

and Texaco service station across from Cove Fort on the east side of Highway 91.)39 People who needed to spend the night at Cove Fort simply pulled their automobiles into the courtyard. The Keslers partitioned the original assembly room (on the south side) into a kitchen and dining area and reserved a few rooms for travelers. William Henry later constructed additional small cabins east of the fort to accommodate more travelers.40 The family also helped automobilists and others stranded on the road running through Cove Fort country. In an oral history interview, Otto shared several harrowing experiences. “I remember one time, they brought a man and two boys in there. Their ears just a-black ends. They had frost sticking out on them.” Instead of bringing the family in by the stoves to get warm, the Keslers gave them a snow bath. “They put snow on their ears, and put their feet in snow and their hands and everything. Rubbed snow all over their faces and gosh, the frost just come out of their ears.”41

Located along a major highway, Cove Fort quickly attracted the attention of preservationists. There is evidence that as early as 1921 citizen groups tried to persuade the legislature to designate the fort as a state park.42 Efforts to these ends intensified after F. B. McCombe purchased Cove Fort from the Keslers in 1926. Originally from Oklahoma, McCombe and his son had grand designs to turn Cove Fort into a dude ranch, replete with a swimming pool and interior dance floor.43 It is not clear why William Henry Kesler sold the fort, but some found McCombe’s crass commercialism offensive.

“The old ever gives way to the new,” Beckwith cynically observed in his 1927 Improvement Era article: “Cherished landmarks of any region, one by one, are replaced or changed by the onward march of progress—and not always by way of betterment.” He went on to elaborate,

Historic “Old Cove Fort” is now a “Dude Ranch!” Alongside those ancient walls is now a gas station, a hideous thing of galvanized iron, and stalls to display wares for the camper. Nailed upon the very stones (that but for them would breathe a spirit of deepest sentiment) are now gaudy road signs, screeching with raucous voice a message to the autoist. A huge

sign tells you it is a “Camping Station.” But, you have to hunt, in neglect, in weathered paint growing dim, to find the words which bring into being every fondest remembrance of the place—Old Cove Fort.44

In order to both preserve Cove Fort’s history and create a tourist destination, civic groups and highway boosters erected a monument commemorating the Black Hawk War and the fort’s sixtieth anniversary in April 1927. W. O. Cluff of the Richfield Commercial Club presided over the dedication festivities, which included remarks by Heber J. Grant, then president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Ira N. Hinckley’s sons, Bryant, Edwin, and Arza. Despite the fact that the fort had never known armed conflict, locals treated the gathered crowd to a “sham battle for the possession of the fort, executed between a group of cowboys representing the Indians and attacking the fort, and the Richfield battery defending it.”45 A few months later, however, the McCombs left Cove Fort, leasing it to J. M. Perkins and W. R. Monroe, both of whom were involved in Sulphur, Utah, mining. Perkins and Monroe planned to continue running Cove Fort as a resort, but by January 1929, they, too, left and the Keslers repossessed the fort.46

When William Henry Kesler reacquired Cove Fort, he set out to establish it as a historic site, most likely playing to increased automobile traffic and commercial club interest in selling southern Utah as a tourist destination. He spent time locating artifacts and memorabilia visitors might find interesting—guns predating the Civil War and an impressive saddle and coin collection.47 He constructed a small outbuilding near Cove Fort to house these curiosities, calling it “the museum.” He also purchased a Studebaker borax wagon from Death Valley and parked it in the fort’s courtyard.48 Kesler made his most significant find in 1930 when Ira Edward McMullin, an LDS bishop in Leeds, Utah, contacted him with an enticing offer. The Leeds congregation was in the process of constructing a new meetinghouse and wanted to replace its bell. McMullin had learned that a local hardware dealer had recently sold Cove Fort such a bell. Would William Henry trade his new bell for the old one? A load of fruit would be thrown in to cement the deal—after all, the Leeds Ward bell was not just

any bell. According to tradition, it had served as the dinner bell for federal troops (Johnston’s Army) who came to the territory as part of the Utah War. In 1861, when Union Army Colonel Patrick Connor arrived in Utah, he took the bell and cannon from Camp Floyd and installed them at Camp Douglas (later Fort Douglas). Sometime in 1877, a few daring Mormons made off with both bell and cannon. Concealed in a load of grain, the bell found its way to the Leeds meetinghouse. With a reported provenance like that, William Henry could hardly resist, and the dinner bell has been in the Kesler family’s possession ever since.49

In 1934, shortly after Kesler acquired the famed bell, the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association was the last organization to encourage the establishment of a state park at Cove Fort.50 The Daughters of Utah Pioneers joined this effort after unveiling one of its historic markers at the fort in 1935. When the state legislature failed to appropriate the necessary funds to purchase Cove Fort, the Landmarks association offered to buy the fort for $8,500, provided the federal government would make it into a national monument.51 Nothing more came of this effort, however, and the Keslers remained at Cove Fort. It was during these years that Otto bought Cove Fort from his father, paying his other siblings for their shares after William Henry died in 1947.52

In many respects, Otto Kesler was Cove Fort. He grew up at the fort and lived there almost continuously from the time his family first arrived in April 1904 to his death in 1966. The history from this period comes primarily from interviews and conversations with LeGrande Davies, who has many fond memories of his grandfather Kesler. In these recollections, Otto acquires almost mythic proportions. He is razor smart, deeply fair, and honest to a fault. Otto’s ability to read and manage the land figure prominently in these interviews as do the relationships he forged with the Paiute band at Kanosh.

In 1916, Otto married Mary Yardley and had a son, William Kesler, in 1917. Tragedy struck the young family in November 1918, when both Otto and Mary contracted Spanish influenza. Mary died later that month at Beaver; Otto was so ill that he was unable to attend her funeral.53

Two years later in 1920, he married again to Alice Thomas. In a span of ten years, between 1921 and 1931, they had five children: Mary Loree, David Otto, Joseph Frederick, Marion Leon, and Calvin Thomas. Two of these children, Mary and David, were born at Cove Fort; the others were born in Greenville or Fillmore.54 Like his father, Otto later kept a home in Fillmore so his children could attend school, but during summers, the family spent most of their time at Cove Fort. Kesler raised cattle, meat hogs, and sheep and acquired additional acreage near Milford and Kanosh.55 By the 1950s, Otto left the day-to-day operation of these farms to his sons. An accident he sustained years earlier while working at a Sulfphurdale mine made it impossible for him to ride a horse in his later years. Instead, Otto spent his time keeping the service station at Cove Fort. “It was very frustrating to him, I think, that he wasn’t able to physically get out and do everything,” LeGrande Davies later reflected.56

Otto’s two sons, Calvin and David, along with their wives Faye and Helen, moved into Cove Fort, occupying the six rooms along the fort’s

north side. Each family had a bedroom, front room, and a kitchen. A partitioned-off corner in each kitchen functioned as a small bathroom and shower. Tourists who stopped at Cove Fort never fully realized the historic site functioned first as a home. “People would come in—they’d just open the door and walk in on you. And they’d say, ‘Oh! We didn’t know anybody lived here,’” Davies remembered.57

Cove Fort not only bound the Keslers to the land but also linked them with earlier generations of Mormon settlers and pioneers through the common experience of hard work. At five years old, LeGrande Davies steered a hay truck while men loaded bales. “The truck, basically got into the furrows and it kind of stayed there. But my job was to make sure that it didn’t run over any bales. When we would get to the end of going down a row . then my job was to jump down, step on the clutch, and push up as hard as I could on the steering wheel and hold it there until one of them could come in and kick the truck out of gear.” Most importantly, at the end of the summer, Davies lined up with the others to receive his pay—a check for two dollars signed by Otto Kesler. The next year he worked with his uncles, learning how to push cows, keeping them out of roadways, and moving them to different rangeland and water sources. “The year I was seven . is the year I had to catch my own horse, I had to saddle my own horse, and then I started driving cows, driving them out of the lanes. . . . Me and the dogs and the horse.” All alone he drove the cows fifteen to twenty miles a day to new feed and water. “Didn’t do a lot with the hay after that. They got a side loader. . . . But I liked the horses and cattle better.”58 The added responsibilities gave Davies a sense of satisfaction. “I was proud of the fact that I could ride. I was proud of the fact that I could break horses. And it was interesting that my uncles became very proud of that same thing.”59 Experiences like these continued a tradition that reflects preindustrial times. As the labor historian Chaim Rosenberg writes, “A farmer could not afford much hired help but depended on his wife and children to help with the farm work. One farmer said, ‘Every boy born into a farm family was worth a thousand dollars.’” Because child labor reformers saw agricultural work as beneficial for children, especially boys, instilling in them the value of honest labor, discipline, and thrift,

few questioned the health or safety risks these activities posed.60 Davies views his childhood at Cove Fort in a similar light.

Most importantly, working at Cove Fort allowed Davies to spend hours with his grandfather, developing a special bond between them. In oral history interviews, he often reflected on his grandfather’s many abilities. “He had a gift for dealing with horses that I had never seen with anybody. . . . Seeing just what he did with them, even in his crippled state, was amazing to me. . . . My grandfather could talk to them and they were just as calm as could be when he was working with them and when he was around them.”61 According to Davies, Otto was a quiet man, known for his photographic memory and strict honesty. “You ask him about a date or a time or an event and he gave it to you exactly. . He gave it to you as he had seen it. He was a man who was honest and straightforward and everything to him was black and white.” Davies continues, “He memorized things like you wouldn’t believe. . . . He had a mind like a steel trap.”62

It was from his grandfather, too, that Davies learned to love and respect the land. “Cove Fort—it’s rugged country. It’s hard on people,” he observed. “That land’s a desert. But it produces and it produces a lot if you don’t take too much at a time. But you have to take from it. If you don’t, it doesn’t produce as much.” The Keslers survived as well as they did because William Henry and Otto Kesler and their families learned the cadences of the land. “They were very observant with what they were doing. They watched carefully. My grandfather . watched things and he was able to tell when something was working and when something wasn’t. He was able to watch the balances of things.” Otto’s prodigious memory certainly helped. Coming to Cove Fort as a child, he remembered almost everything the family did to the land. He often shared this information in passing to those who would take the time to listen.63 For years, Otto took daily temperature readings for the United States Weather Bureau. He remembered the drought times when, with little to no irrigation, gophers burrowed through the dried-out fields, clipping the roots and destroying the remaining crop. At other times, the ground became alive with hordes of black crickets, marching and devouring every green thing in sight. “They come across the

fields, they come, just didn’t go around the Fort, they just climb over it and down the walls and over and over the walls and right on, just kept a-going,” Otto recalled.64

The Keslers quickly found that for the land to produce at its optimum, it had to be both grazed and farmed. An article for the Utah Farmer explains the process the Keslers used for managing the land. “Since the area is high and frosts occasionally are destructive, [Otto] Kesler and his family have learned how to meet this hazard.” The article continues, “Strange as it may seem, a large herd of beef cattle is the answer, for if a late spring frost hits the dry farm grain just as it is coming into the boot, the hard-bitten grain fields are immediately turned into beef pastures and the grain utilized for cattle feed.”65 The Keslers also found feed for their cattle in seemingly impossible places, like the shadscale and sagebrush ranges west of Cove Fort. “Had a USU guy once come and told us that you couldn’t raise cattle on shadscale,” Davies remembered. “So my granddad suggested that I take him out for a ride and show him. I think I was about fourteen, fifteen. Didn’t have my driver’s license yet, but I drove him out. And we went and watched them eat the shadscale and he was dumfounded.”66 In the wintertime, cattle fed on sagebrush. “We would pick an area where sagebrush was becoming too much . . . and then we mixed cotton seed meal and salt together . . . and it made the cows exceptionally hungry. And what we would do was we’d feed them enough hay to not completely fill them up, but to give them enough . . . energy . . . and the cotton seed meal also helped to give them the vitamins. . . . But then they’d start to eating sagebrush. . . . And our cattle would winter really, really well,” Davies explains, adding, “I don’t know that a lot of people could survive . . . wintering cattle in that area.”67 The Keslers always watched the carrying capacity of the land and kept their cattle herds under 250 head. “It’s the people that were careful that finally ended up with the land. The others would overgraze. They’d go in debt and they’d get all these extra cows and then they’d go broke,” LeGrande observed.68

The Keslers utilized the land in other ways. Like those who came before them, they often bred their mares and then turned them out

onto the range where they would foal. They caught and broke a horse when they needed one. Volcanic lava flow, ash, and cinders break up the range southwest of Cove Fort. “Those horses would run on those lava flows. Running across all that rock all the time, they ended up with the hardest hooves you could imagine,” Davies noted. “It made their hooves extremely hard and it made them perfectly shaped. We never had any problems with horses with broken hooves or horses with chipping hooves.”69

In the end, Davies believes his grandfather inherited the land because he valued it the most. “I think all of his other brothers wanted to go someplace else.” On summer evenings LeGrande loved to sit with his grandfather, watching the sun melt into the hills west of Cove Fort, together savoring the stillness that enveloped the land. “There was a group of coyotes that used to sing out there. Grandpa would always say, ‘Ah. Can’t they sing well. Can’t they sing well.’ There was a peacefulness that would come because the wind quits blowing in the evening.”70

Outside of the Kesler family and other hired help, members of the Paiute band at Kanosh formed an important labor force. Davies remembered them only in terms of family:

The Paiutes that worked for us, that worked for us when I was young, they would come and work with my grandmother in the kitchen and help . . . her clean, they helped her with washing. They were given room and board. They ate with the family when we ate, their kids . . . we’d played around together a lot. . . . The husbands, the males would work out on the farm. They plowed; they worked side by side with us.

“They didn’t get the dirty jobs any more than anybody else got the dirty jobs,” He stresses. “Everybody got the same dirty jobs. You had to dig a cesspool, why everybody got a chance to work in it. . . . They held down calves. They worked with cows when we were doing that. They plowed, they drove tractors, they hauled hay, they were part of the family.”

Throughout this interview segment, Davies was careful to emphasize Paiute cleanliness,

perhaps as a way to counter common racial prejudices he may have heard growing up. “My grandmother, she would have never allowed somebody in the kitchen who wasn’t clean. That meant you had to wash your hands. These women were clean women. They knew how to cook.” Davies continued, Bell was really, she was a great cook. And I mean, a really, really good cook. She cooked traditional Indian foods. . . . [She] was one of the ladies that worked with my grandmother. . . . I don’t know how she got the name Bell. I’ve forgotten what her Indian name is. That’s awful because I knew it. But I forgot what it was. Her husband was a medicine man [Wes]. He traveled around through the western part of Utah and Nevada and up into Idaho, and so on, blessing people and marrying people and going about. He was a well-thought-of man. But we stayed pretty close as families. We were really good friends.

He concluded, “They weren’t ‘dirty Indians.’ They were people. And they were treated as people. I don’t know. That’s always the way I saw it, anyway.”71

Work by the ethnohistorian Martha Knack reveals that the Keslers’s use of Paiute wage labor reflects a much longer history that was characteristic of Mormon-Paiute relationships stretching back into the nineteenth century. It was not uncommon for Paiute men to be employed as temporary farm workers; women often worked as domestics. Indeed, Great Basin tribal groups shifted into this kind of wage labor early on, especially once Mormon settlers dominated food and water resources. Knack cited one Indian agent who, observing in the 1870s, noted that Mormons living in St. George employed Paiutes from the Shivwit band. “Some of the men are excellent cowboys, and have work much of the time with neighboring cattlemen, while others hoe and do other small chores,” the agent reported. Davies’s assertions of familial relationships notwithstanding, in general, Native workers were paid significantly less than whites and were only employed in unskilled or semiskilled work.72

Finally, Otto Kesler continued to operate Cove Fort as a way station, helping countless individuals hard on their luck, especially the “footmen,” homeless men who trod the highway’s dusty shoulder. Whenever Kesler saw them coming, he sent LeGrande out with some Spam, a loaf of bread, or other canned goods

Inside the store at Cove Fort, Christmas 1957. Top row, l–r: Mary Kesler Davies, A. LeGrande Davies, Faye Kesler, LeGrande K. Davies, Calvin Kesler, Alice Kesler, and Otto Kesler. Front row, l–r: Pamela and LaNila Kesler (children of Calvin and Faye Kesler). Courtesy LeGrande Davies

from the store. These he strategically placed in nearby garbage cans for the men to find. Other times the Keslers offered temporary employment and a place to stay.73 One night they very likely helped save a man’s life. A police officer found Bernard Bee half frozen in a blizzard and brought him to Otto’s service station where Bernard polished off a jar of peanut butter, one spoonful at a time. He made it clear he was no charity case, however. He’d work for his supper.74 Bee became an integral part of Cove Fort and the Kesler family. He loved to fix fences and construct outbuildings and sheds. He had worked in a circus and had a stepfather who often beat him, leaving him with a shrunken, misshaped head and a back riddled with scars and lashes. Bee stayed with the Keslers twenty-four years. When Davies left on his mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he gave Bee his World War II bomber jacket. “It was made out of sheepskin and stuff. And he used that. He used that for so many years until he totally wore it out. They finally had to buy him another one. . . . He’s buried in Beaver next to my Uncle Joe.”75

The way of life the Keslers enjoyed at Cove Fort nearly ended when Utah received approval for a new interstate highway in 1957. The proposed route connected the interstate out of Denver with Highway 91 just south of Cove Fort.76 No one was more pleased about the news than Otto Kesler. “Yes sir, this is going to be quite a place when they build the highway,” he told the Associated Press that fall.77 Yet what initially appeared to be a boon almost cost the family the fort. Both in oral history interviews and documentary material that detail this period, Otto Kesler emerges as a proverbial underdog, fighting not only to maintain ownership of his fort, but to preserve a way of life for his family and the foundational ties to the past that went with it.

In the years following World War II, Utah vied with other western states for its share of tourist traffic. A 1958 study by the University of Utah’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research found that 85 percent of Utah’s tourists came to the state by car. Of those, an estimated onethird were Californians.78 The report confirmed what many already suspected: Cove Fort, situated as it was along Highway 91 and now near

a proposed interstate highway exchange, was prime real estate. Early that same year, officials offered the Kesler family $40,000 for the fort and ten surrounding acres with hopes of turning the property into a state historic site. Otto Kesler had no intention of selling—especially at such a low price. In response, the state began condemnation proceedings in July, hoping to secure the property through right of eminent domain.79

The following June of 1959, court proceedings took place in Fillmore. LeGrande Davies remembers the summer well. At fourteen, he stayed at the fort while his parents, grandfather, and uncles traded off attending the trial and working the farm and station. Every evening when they returned from court, Davies listened to the adults long into the night animatedly discussing the case. “I remember . my grandfather a few times coming back home . . . he was so angry about things he would just shake all over.”80 Mark Paxton, who supplied the Kesler’s Texaco station, served as a star witnesses in the case. Paxton conducted a traffic count on a Sunday morning between 9:35 and 11:35 a.m. During that time 515 vehicles passed by Cove Fort, ninety-one stopped, and 335 people visited the fort. Paxton suggested in light of the current interest in Cove Fort, the state should pay the Keslers at least $190,000. After five days of trial, the jury valued Cove Fort at $70,000, without any land except that which the fort sat on. The Keslers were not in the clear yet, however. Nor were they about to accept the new value. Fifth District Court Judge Will Hoyt, on the other hand, recommended the state appeal the case, believing the award was “excessive” and that the jurors “‘were influenced by testimony based upon speculation and upon assumptions of fact not proved by competent evidences.’” The state attorney general, Walter Budge, suggested otherwise, noting the undue burden such an action would place on taxpayers. Public opinion also swung in favor of the Keslers. In an editorial titled “A Vulture Waits,” the Springville Herald criticized, “This case, we believe, is like many others where the law of eminent domain is exercised too far giving the individual few, if any, rights to his own property.” The Salt Lake Tribune took a more measured stance, observing, “Considering the divergence of opinion as to the value of the

property, the feeling engendered by the efforts to turn a private enterprise into a public one by court action, and the growing demand for use of state funds on other projects, the park commission might well reconsider this matter.” The Tribune concluded, “We suggest that the park commission concentrate on more urgent sites, meantime keeping an eye on Cove Fort and continuing efforts to negotiate for purchase when conditions are more favorable.” The state conceded and dropped the suit in September 1959.81

Following the court case, Otto Kelser decided to restore Cove Fort and convert it into a museum. The state suit and the threat of losing Cove Fort for good certainly contributed to his decision. In 1959, John Riley worked on the fort’s south side, using plaster, flooring, and shake shingles that matched the original. The Keslers had not occupied the fort’s south side since World War II when, because of the scarcity of metal granaries, they used it to store grain as part of the federal Hot Wheat program.82 “All window sills . doors, and casings are the original, with many of the wooden pegs still used, rather than nails,” the Beaver Press observed. Two years later the George Brothers

construction company restored the north side, which had long served as living quarters for the Kesler family. In the meantime, Otto’s daughter and son-in-law, Mary and A. LeGrande Davies, along with Calvin and Joe and their wives, Faye and Carol, located many of the objects for the museum. Instead of seeking artifacts directly associated with Ira N. Hinckley, as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did in their restoration years later, the Keslers acquired and displayed objects from the families who helped construct the fort: head mason Nicholas Paul’s trumpet and organ, a walnut bed from the Robison family, a dresser from the Warners, rugs, and other antiques. These objects told an important story that emphasized the history of Cove Fort’s builders and the region as a whole.83

LeGande Davies, then in high school, wrote a short pamphlet for distribution that detailed the fort’s history. Entitled “Brigham Young’s Old Cove Fort,” the pamphlet demonstrates how the family thought about historic site interpretation and gives an insight into the narrative they crafted and shared with tourists. Davies’s pamphlet includes brief sections on Wilden Fort, a structure that predated Cove Fort’s construction; the Black Hawk War; and

Young’s decision to construct a fort in the area initially as a protection against Native Americans, later as a way station for travelers. Ira N. Hinckley, incidentally, receives only a brief mention. The bulk of the pamphlet discusses Cove Fort’s architectural features and closes with the arrival of the Kesler family.84 This emphasis on architecture likewise figures prominently in oral history interviews with Otto Kesler. Even today, the fort’s physical features come up often in conversations with LeGrande Davies.85 Through their experiences of living at the fort, the Keslers seem to have acquired an intimacy with the physical place that directly contributed to their sense of responsibility for Cove Fort and its history.

The operating season for the Cove Fort “museum” ran from March through October. The Keslers charged fifty cents for adults and twenty-five cents for children to see the fort, literally making hundreds of dollars every day—mostly loose change and silver dollars from Las Vegas slot machines. Every night they counted the money and took it to the bank. As part of the 1959 to 1960 restoration, the family converted one of the north side rooms into a small souvenir gift shop that the Kesler women stocked and managed. They often engaged visitors in conversations about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Turning in countless missionary referrals, they sold or gave away copies of the Book of Mormon by the case load along with other literature acquired from the

church.86 Business peaked in the early afternoon when travelers stopped at Cove Fort, eager for lunch and a break from the road. “Cars were parked all along the front of the store, the fort, and then over on the north side. . You might have thirty cars at a time there,” Davies recalled.87 All of Mary, Joe, and Calvin’s families served as tour guides at one time or another. The youngest guide may have been Calvin’s son, Kevin. As a toddler he often walked out in front of the tour group, showing visitors the fort’s historic features. “He had the whole tour memorized,” Kevin’s older sister Pam remembered. “But no one knew what he was saying. . . . He would squat down and he would show them each of the wooden pegs [in the door] and he knew which panes were original glass and which were not.”88

During the off season, when the sun weakened and the air sharpened with the smell of approaching winter, Cove Fort opened up to trophy deer hunters from California. The Keslers advertised their services with the Richfield KSVC radio station. “Where and how to bag that deer is certainly a favorite topic of conversation these days,” one announcement ran. “While no one can guarantee you a deer, your chances of a successful hunt are excellent if you’ll do your hunting in the Cove Fort area. . While doing a bit of resting, be sure to explore the inside of historic old Cove Fort. . . . Also groceries and Texaco products at Old Cove Fort . . . and hunting information too.”89 They camped on the

frost-bitten fields north of the fort, creating a veritable tent city, population three hundred. Some returned year after year—Hollywood screenwriter Bob Leach and the Creole family from Louisiana who always bottled their deer meat before making the long voyage home.90

In many respects Cove Fort symbolized a lifestyle fast disappearing in post–World War II America’s maze of interstate highways and suburban housing tracts. The Keslers were some of the last holdouts. Sometimes on a summer evening when the family gathered at Cove Fort, they shut the gates and turned on floodlights. “It was a nice place to be,” LeGrande remembered. “You could close the doors and let the rest of the world go by.”91 Yet even the strongest of gates could not protect Cove Fort from change. Otto Kesler died while LeGrande was on his church mission in 1966. His death spelled the end of an era for the Keslers at Cove Fort. Without Otto’s unifying influence, the family splintered. A court order shut the Cove Fort museum until the family could resolve its legal disputes. A second blow to the Keslers came with the construction of Interstate 15 in the 1970s. The interstate “changed everything, financially,” Davies recalls. “We didn’t get the gas then. People didn’t come into [the Fort] because they couldn’t see where it was. They couldn’t see the store and we weren’t open late at night either. We closed up when it got dark. . . . Cars would just go by and they didn’t stop.”92 In addition, a fire decimated the Kesler’s store and service station in July 1971.93

By the late 1980s, the family struggled to pay taxes on the fort and the surrounding property. Realizing they could no longer properly maintain and care for Cove Fort, the Keslers reached out to descendants of Ira N. Hinckley in early 1988. Hinckley family representatives expressed an interest in purchasing the fort and deeding it back to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to be used as a church historic site. At the end of the summer, the church had officially reacquired Cove Fort and began plans to restore it back to the days when the Hinckleys lived in the fort. Gordon B. Hinckley, then serving in the church’s First Presidency, called the transaction “a miracle.” It was a bittersweet moment for members of the Kesler family.94

Mary Kesler Davies best articulated what she and the others felt the day Cove Fort officially passed from the Keslers’s hands. “I am hurt . . . but still I am glad.” Unlike a state park, the Cove Fort Historic Site would continue to serve as a way station, a place where others could learn about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and reflect on the sacrifices of the early Mormon pioneers.95

Decades later, though, the hurt is still there. “My granddad had always said, ‘Whatever you do, keep hold of the fort, don’t sell it. . . . I wasn’t going to go back down and farm. . What do you do? I don’t know.”96 For Davies, the sense of loss never goes away but neither do the memories of a time when Cove Fort was more than a ranch, or even a home, but a kind of loadstar—a place that continues to teach him about his identity and the values he learned from his grandfather and uncles.

There is a newspaper photograph of Otto Kesler taken in 1960 by the Salt Lake Tribune. He stands confident, resolute, and tall in his button-up shirt and tie, wisps of hair blowing in the incessant wind. Behind him are Cove Fort’s thick volcanic walls. He is guarding the fort and keeping it safe.97 Today, some of his family continue to ranch the area. Others, like Davies, took a different path. Although the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints owns and manages Cove Fort, the Keslers’s sense of responsibility for the site and its history does not waver. Oral traditions preserve the Kesler family’s significant history at Cove Fort, binding the family to a place and a land other people only pass through. For the Keslers, the story of the Cove Creek Ranch Fort will continue to be one of stewardship, survival, and a profound, complex love for the land and for each other.

1. Stefan Kirby, Geologic and Hydrologic Characterization of Regional Nongeothermal Groundwater Resources in the Cove Fort Area, Millard and Beaver Counties, Utah, Special Study 140, Utah Geological Survey (2012), 5; “Basin and Range-Colorado Plateau Transition Zone,” Utah Geological Survey, accessed May 15, 2017, files.geology.utah.gov/emp/geothermal/br-cptzone.htm.

2. LeGrande Davies, interview by Rebecca Andersen, January 3, 2013, Brigham City, Utah; LeGrande Davies, telephone conversation with Rebecca Andersen, March 25, 2017, all interview recordings and transcriptions in possession of the author.

3. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013; Davies, telephone conversation, March 25, 2017.

4. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013; Davies, telephone conversation, March 25, 2017.

5. Jacob W. Olmstead, “Cove Fort, Then and Now,” Church History, January 20, 2016, accessed November 26, 2021, history.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/historic-sites /utah/cove-fort/cove-fort-then-and-now?lang=eng.

6. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 26.

7. Hal Rothman, Devil’s Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-Century American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 11.

8. It should be noted that Davies and other members of the Kesler family simply refer to Cove Fort as “the Fort.”

9. Alessandro Portelli, “What Makes Oral History Different,” in The Oral History Reader, 2nd ed., ed. Robert Perks and Alistair Thomson (New York: Routledge, 2006), 36.

10. Larry C. Porter, “A Historical Analysis of Cove Fort, Utah” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1966), 105–108.

11. Otto Kesler, interview by Larry Porter, 1964, Fillmore, Utah, copy in possession of the author.

12. Utah, U.S., Death and Military Death Certificates, 1904–1961, s.v. “William Henry Kesler,” State of Utah Certificate of Death, September 27, 1947; 1910 United States Federal Census, Kanosh, Millard, Utah, roll T624_1604, page 7B, enumeration district 0063, William H. Kesler, both accessed November 29, 2021, ancestry.com. See also familysearch.org/tree/find/id, s.v. KWCY-R79, William Henry Kesler, accessed November 29, 2021.

13. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

14. Otto Kesler quoted in Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 107–108; Otto Kesler Oral history, interview by Larry C. Porter, 1964.

15. Kesler, interview, 1964.

16. “Utah Auto Traffic Shows Increase,” San Juan Record (Monticello, UT), July 24, 1941; “Highway 91 Has Large Travel Increase,” Springville (UT) Herald, July 31, 1941.

17. Kesler, interview, 1964.

18. Kesler, interview, 1964.

19. LeGrande K. Davies, telephone conversation with Rebecca Andersen, May 29, 2018; Kesler, interview, 1964. The “Locals and Personals,” Beaver (UT) Press, April 1, 1927, notes an additional line. “A crew of twelve men under the foremanship of Mr. Bean, of the Mountain States Telephone company, are making their headquarters in Beaver, while repairing the telephone line between Beaver and Cove Fort.” Copy of title in possession of LeGrande Davies.

20. Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 109.

21. Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 109; Davies, conversation with Rebecca Andersen, July 20, 2018.

22. Kesler, interview, 1964.

23. Utah, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940–1947, s.v. Murray Kimball Kesler, October 16, 1940, accessed November 29, 2021, familysearch.org; familysearch. org/tree/find/id, s.v. KWCY-R79, William Henry Kesler; “LaRee Kesler Johnson,” Herald Journal (Logan, UT), March 19, 2011.

24. Kesler, interview, 1964.

25. LeGrande Davies, interview by Rebecca Andersen, April 2, 2013, Brigham City, Utah.

26. Davies, conversation, July 20, 2018.

27. Kesler, interview, 1964; Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

28. “The Board of Pardons Listens to a Novel Oration by a Ute,” Salt Lake Herald, August 16, 1896; “‘Hick’ Davis Tells One,” Millard County (UT) Chronicle, October 24, 1929; “Who’s Hunkup?” Millard County (UT) Progress, December 26, 1980.

29. Kesler, interview, 1964.

30. W. Paul Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 101–109.

31. John E. Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 120–21, 136.

32. “Frequently Asked Questions,” Daughters of Utah Pioneers, isdup.org/dyn_page.php?pageID=50; Thomas G. Alexander, “A History of the Sons of Utah Pioneers,” National Society of the Sons of Utah Pioneers, sup1847. com/ahistoryofthesonsofutahpioneers, both accessed December 1, 2021.

33. Albert F. Philips, “Know Utah,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 20, 1928.

34. Earl Pomeroy, In Search of the Golden West: The Tourist in Western America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957); Marguerite S. Shaffer, See America First: Tourism and National Identity, 1880–1940 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2001).

35. Susan Sessions Rugh, Are We There Yet? The Golden Age of American Family Vacations (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008), 100–101.

36. “Building Highway on St. George Route,” Salt Lake Tribune, October 8, 1916.

37. David A. Hales, “The Renaissance Man of Delta: Frank Asahel Beckwith, Millard County Chronicle Publisher, Scientist, and Scholar, 1875–1951,” Utah Historical Quarterly 81, no. 2 (2013): 176–80.

38. Frank Beckwith, “Historic Old Cove Fort,” Improvement Era, April 1927, 534.

39. Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 159–60; Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

40. Davies, interviews, April 2, 2013, May 17, 2013; Writers’ Program, Works Progress Administration (Utah), Utah: A Guide to the State (New York: Hastings House, 1941, 1945), 295.

41. Kesler, interview, 1964.

42. “Old Cove Fort May Be Kept by State as Relic,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 26, 1921.

43. “Old Cove Fort May Become Dude Ranch,” Richfield (UT) Reaper, October 14, 1926; “Historic Cove Fort to Be Rehabilitated,” Beaver County (UT) News, February 11, 1927.

44. Beckwith, “Historic Old Cove Fort,” 532.

45. “Two Thousand People Attend Cove Fort Meet,” Richfield (UT) Reaper, April 28, 1927.

46. Beaver City (UT) Press, July 29, 1927; “General Items,” Progress (Millard County, UT), January 18, 1929.

47. Clint Pumphrey and Jim Kichas, “From Tire Tracks to Treasure Trail: Cooperative Boosterism Along U.S. Highway 89,” Utah Historical Quarterly 85, no. 3 (2017).

48. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

49. Marietta M. Mariger, Saga of Three Towns: Harrisburg, Leeds, Silver Reef (Panguitch, UT: Garfield County News, 1951), 39–40. The only other source that might confirm this story comes from an article in the Deseret Evening News dated November 28, 1877, which reports that police found goods stolen from Camp Douglas in

a Salt Lake second hand store. It does not mention the cannon or dinner bell, however.

50. “Plans Discussed for Dedication of Fort,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 18, 1934; “To Preserve Cove Fort,” Beaver County (UT) News, December 6, 1934.

51. “Marker Unveiled at Cove Fort by the Pioneer Daughters,” Richfield (UT) Reaper, August 8, 1935; “Trails, Landmarks Group Urges Cove Fort Purchase by State,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 7, 1935; “Plan to Purchase Cove Fort Made by Trails Group,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 4, 1935.

52. Kesler, interview, 1964.

53. “Young Wife Succumbs,” Salt Lake Tribune, December 1, 1918.

54. 1930 United States Federal Census, Fillmore, Millard, Utah, page 1B, enumeration district 8, Otto Kelser, ancestry.com; familysearch.org/tree/find/id, s.v. KWCR9JT, Otto Kesler, both accessed December 2, 2021.

55. David H. Mann, “A Century of Farming at Old Cove Fort,” Utah Farmer, May 7, 1959.

56. LeGrande Davies, interviews by Rebecca Andersen, April 2, May 17, 2013, Brigham City, Utah.

57. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013;

58. Davies, interview, April 2, 2013.

59. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

60. Chaim Rosenberg, Child Labor in America: A History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013) loc. 2137–2142.

61. Davies, interview, April 2, 2013.

62. Davies, interview, April 2, 2013.

63. Davies, interviews, May 17, January 3, April 2, 2013.

64. Kesler, interview, 1964.

65. Mann, “A Century of Farming at Old Cove Fort.”

66. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

67. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

68. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

69. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

70. Davies, interviews, May 17, January 3, April 2, 2013.

71. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

72. Alice Littlefield and Martha C. Knack, eds., “Introduction,” in Native Americans and Wage Labor: Ethnohistorical Perspectives (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 12, 29; Martha Knack, “Nineteenth-Century Great Basin Indian Wage Labor,” in Native Americans and Wage Labor, 144–46, 149–50, 153.

73. LeGrande Davies, telephone conversation with Rebecca Andersen, July 26, 2018.

74. Pamela Kesler Robison, interview by Rebecca Andersen, July 13, 2018.

75. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013; Robison, interview, July 13, 2018; “Bernard Bee,” Beaver (UT) Press, October 30, 1986.

76. “Twenty-five Counties Give Support to Highway Route,” Iron County (UT) Record, November, 14, 1957.

77. “Road Brings Bonanza Hope to Cove Fort,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 20, 1957; “Fort Proves Ad-

age—Where Life, Hope,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 10, 1958.

78. Susan Sessions Rugh, “Branding Utah: Industrial Tourism in the Postwar American West,” Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 4 (2006): 455–56.

79. “Acquisition of Park Sites Recommended,” Manti (UT) Messenger, December 25, 1958; “State Files Suit for Title to Historic Pioneer Fort,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 18, 1958; “Cove Fort Seen as Site of State Park,” Iron County (UT) Record, July 24, 1958; “State Hopes to Make Cove Fort State Park,” Millard County (UT) Progress, July 25, 1958; “Cove Fort Land Trial to Resume,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, June 15, 1959.

80. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

81. “Cove Fort Hearing Nears Jury after Fourth Day,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 16, 1959; “State to Buy Cove Fort,” Deseret News, June 17, 1959; “Kesslers Awarded $70,000 for Old Cove Fort after Condemnation Trial,” Beaver (UT) Press, June 26, 1959; “Court Issues Cove Fort Trial Order,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 8, 1959; “State Should Reconsider Cove Fort Suit,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 2, 1959; “A Vulture Waits?” Springville (UT) Herald, September 3, 1959, also quoted in Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 171.

82. LeGrande Davies, conversation with Rebecca Andersen, June 20, 2018.

83. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013; Porter, “Cove Fort, Utah,” 172; “Kesler Family Reopens Historic Old Cove Fort,” Beaver Press, June 10, 1960.

84. LeGrande Davies, “Brigham Young’s Old Cove Fort,” undated, copy in possession of LeGrande Davies.

85. Davies, interview, January 3, 2013.

86. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013; Marion D. Hanks to A. LeGrande Davies, June 16, 1961, copy in possession of LeGrande K. Davies.

87. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013; Hanks to Davies, June 16, 1961.

88. Pamela Kesler Robinson, telephone conversation with Rebecca Andersen, July 13, 2018.

89. KSVC radio announcement, September 30, 1960, copy in possession of LeGrande Davies.

90. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

91. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

92. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

93. “Blaze Guts Store in Cove Fort,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 16, 1971.

94. “President Hinckley Speaks at Cove Fort,” Beaver (UT) Press, August 18, 1988; “Historic Fort Gets a New Lease on Life,” Daily Spectrum (St. George, UT), September 10, 1988.

95. “Cove Fort Goes Back to the LDS Church,” StandardExaminer, August 27, 1988.

96. Davies, interview, May 17, 2013.

97. “Tourists Modern Invaders of Cove Fort,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 31, 1960.

On July 25, 1877, in four simple declarative sentences, the Deseret News summed up a man’s life under a “Drowned” heading in the “Local and Other Matters” section of the paper, sandwiched in-between notices of a horse that had to be put down and a meeting of the Twenty-first Ward. “On June 20th,” it reported, “at Coe and Carter’s tie camp, Weber Cañon, George Carter was accidentally drowned, in the Weber River. An inquest was held over the remains, by a jury, before Mr. James McCormick, Coroner of Summit County. The verdict was that deceased was accidentally drowned while attempting to wade the Weber. From papers found among his effects it appears that Carter was formerly of Montreal, Canada.”1

George Carter was a “river hog” in territorial Utah’s important but often overlooked tie and log driving industry, and on that day his life likely hinged on a single decision made instinctively and reflexively, drawn from his accumulated experience guiding timber to market on the interior West’s rivers. Amid the grinding, crashing roar of thousands of raw logs and rough-cut ties boiling down the Weber River in northern Utah that June, Carter would have maneuvered himself through the adrenaline-fueling chaos for twelve to sixteen hours a day. But on that morning, Carter made a fatal miscalculation. Yet while Carter’s life and final moments may be lost forever in the past, the significant and substantial economy that employed him should not be so ephemeral in the historical record.2

In the arid West, water is the essential element. In addition to providing sustenance, the West’s rivers were also important highways of timber commerce and trade—working water that facilitated territorial settlement and economic development. Yet in Utah’s story, this fascinating aspect of water history has long remained obscured. Log driving originated in Europe, and immigrants to North America brought the practice with them.3 Wood was a vital, indispensable resource and early pioneers used it to build, roof, and heat their homes and cabins; fence livestock in (or out); construct furniture; raise barns; tie railroads; make charcoal in kilns

and for smelters; timber mines and road tunnels; fabricate bridges; and erect temples and stores and buildings. It was the fabric of life. In the Central Rocky Mountain West, white settlement and the coming of the railroad expanded tie and log driving in part because rivers were a logical and inexpensive timber conduit in a region devoid of significant roads.4

It should come as no surprise that tie- and log-driving enterprises—the business of acquiring this elemental commodity—were crucial to the personal and fiscal success of some early settlers. While historians have documented extensively the boom-and-bust economies of the West’s other extractive industries such as mining, ranching, timber, and railroads, the centrality of the tie and log drive economy to the development of the interior West has

garnered only passing mention, if at all.5 Yet as the history of the Weber River—as well as that of the Provo, Bear, Blacks Fork, Green, and numerous other rivers throughout Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho—demonstrates, between the 1850s and 1900 especially, tie and log drives were fundamental to the settlement success of the region.6 This, then, is the story of the Intermountain West’s other extractive economy. And a river runs through it.

Although Brigham Young brought the Mormon pioneers to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake in 1847 in part to escape the United States and the persecution they had encountered at the hands of their fellow Americans to the east, the Saints were soon swept back into the national fold, and both those in and outside the LDS church