ft r o r w CI 53 w

s#

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN S ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISORY BOARD O F EDITORS

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 2000

LEE ANN KREUTZER, Torrey, 2000

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2001

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Murray, 2000

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1999

RICHARD C ROBERTS, Ogden, 2001

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 1999

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1999

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi,2001

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801)533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and thebimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on VA inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage ispaid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

ml jCmmimA HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y Contents FALL 1999 \ VOLUME 67 \ NUMBER 4 IN THIS ISSUE 299 THE BEAR RIVER MASSACRE: NEW HISTORICAL EVIDENCE HAROLD SCHINDLER 300 WACCARA'S UTES: NATIVE AMERICAN EQUESTRIAN ADAPTATIONS IN THE EASTERN GREAT BASIN, 1776-1876 STEPHEN P. VAN HOAK 309 WALTER K. GRANGER: "A FRIEND TO LABOR, INDUSTRY, AND THE UNFORTUNATE AND AGED" JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER 331 HOMEMAKERS IN TRANSITION: WOMEN IN SALT LAKE CITY APARTMENTS, 1910-1940 ROGER ROPER 349 BOOKREVIEWS 367 BOOKNOTICES 381 INDEX 383

THE COVER: The nine-story, 144-unit Belvedere Apartment Hotel, built by the LDS church in 1919, was the tallest of the city's early 20th-century apartments.

© Copyright 1999 Utah State Historical Society

MONROE LEE BILLINGTON and ROGER D HARDAWAY, eds African Americans on the Western Frontier ... . FRANCE A. DAVIS 367

K. DOUGLAS BRACKENRIDGE Westminster College of Salt Lake City: From Presbyterian Mission School to Independent College RICHARD C ROBERTS 368

JAMES E SHEROW, ed A Sense of the American West: An Anthology of Environmental History DANIEL C MCCOO L 369

MICHAEL ALLEN Rodeo Cowboys in the North American Imagination . .LYMAN HAFEN 370

VALEEN TIPPETS AVERY. From Mission to Madness: Last Son of the Mormon Prophet DANNY L. JORGENSEN 372

S. GEORGE ELLSWORTH, ed. The History of Louisa Barnes Pratt, Being the Autobiography of a Mormon Missionary Widow and Pioneer VTVIAN LINFORD TALBOT 373

BRYAN WATERMAN and BRIAN KAGEL. The Lord's University: Freedom and Authority at BYU LINDA SILLTOE 375

LYMAN D. PLATT and L. KAREN PLATT. Grafton: Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin ME L BASHORE 376

DAVID L. BIGLER. Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847-1896 PETER H DELAFOSSE 377

FREDERICK LUEBKE, ed European Immigrants in the American West: Community Histories MICHAEL HOMER 378

Books reviewed

In this issue

A recent article in the Salt Lake Tribune relating to the process of education offered the thesis that an educated person must have knowledge beyond a catalog of facts, since "facts change so fast." With only slight reservation, the historian would nod in agreement. Actually, in our profession, and perhaps in the others as well, facts once established do not change. Rather, it is the discovery of new facts, or new ways of looking at old ones, that leads to a refinement of knowledge. Let us delight in the realization that history is constantly being rewritten

Our first article is an excellent example of that process. Although historians have "known" for some time that the Battle of Bear River was really a massacre, not until now, with the discovery of a long-secluded document, can that point of view be fully accepted as fact. As Sgt. Beach's narrative succinctly states, the soldiers heard the cry for quarters, "but their was no quarters that day." His casualty figures, as a soldier who walked the battlefield that cold January afternoon, also pins down the number of Shoshoni dead better than any other source known heretofore. This long-awaited contribution to our knowledge of Utah history is a fitting capstone to the illustrious career of the late Harold Schindler No one valued the bare-boned facts of history more than he

The second article, also relating to Utah's native people in the midnineteenth century, is another case study in historical method Here we see a scholar address a topic in which the facts are elusive but where he nevertheless succeeds in reinterpreting the historical record to create a revised work The reader will understand Waccara's success as a Ute leader just a little better now.

Dealing with twentieth-century topics, the final two selections proceed from a more traditional and resource-rich research base. Yet, the challenge to the historian is no less keen. This same care in organization, analysis, and interpretation of facts must still be applied.

All four articles illustrate the commitment this journal has made to scholarship since its inception in 1928. As its editorial staff prepares to turn the calendar from one century to another, it pledges to continue that tradition long into the indefinite future. And that's a fact.

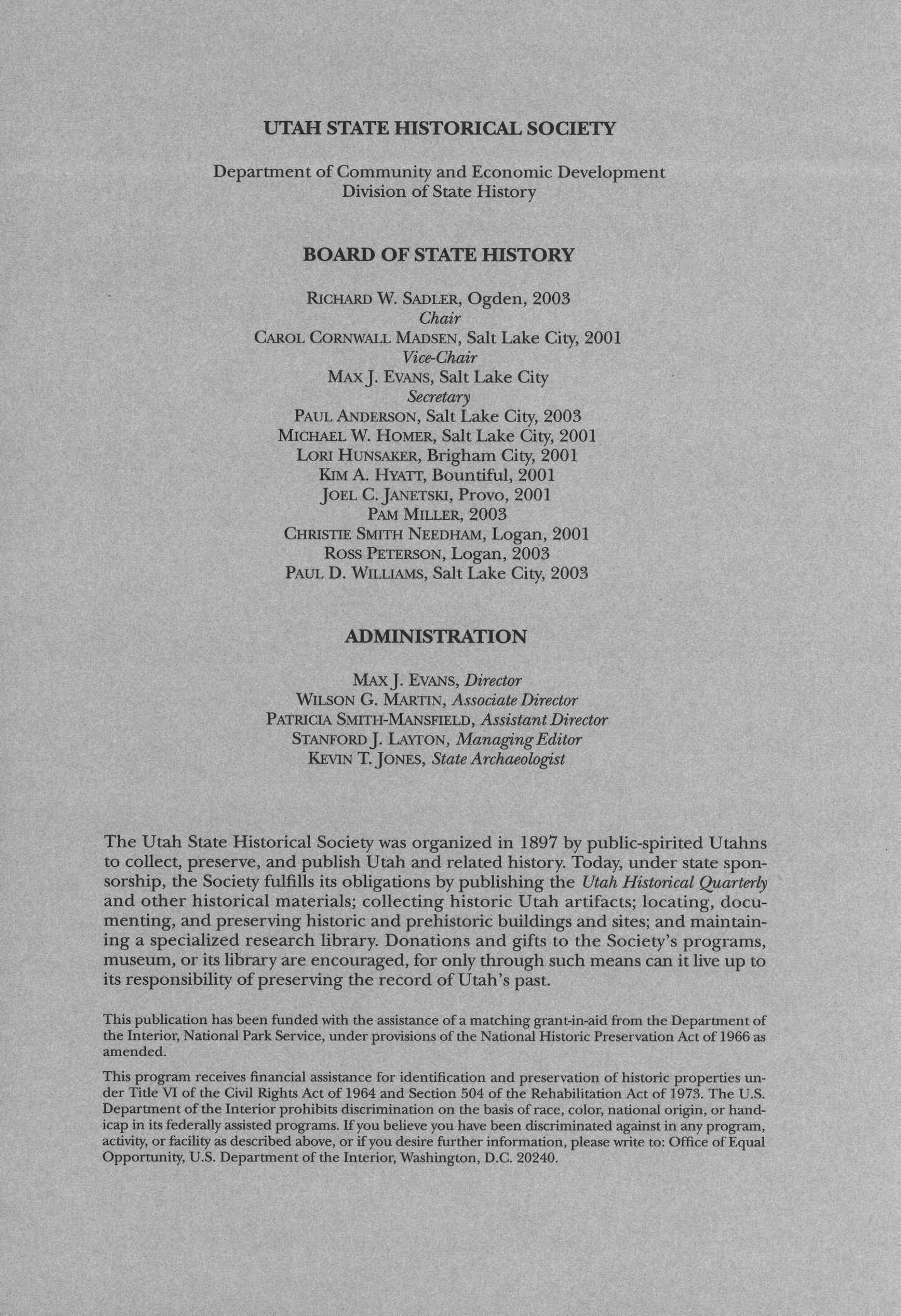

The sword of Col. Patrick E. Connor; USHS collections.

The Bear River Massacre: New Historical Evidence

BY HAROLD SCHINDLER

BY HAROLD SCHINDLER

CONTROVERSY HAS DOGGED the Bear River Massacre from the first

The event in question occurred when, on January 29, 1863, volunteer soldiers unde r Col. Patrick Edward Connor attacked a Shoshoni camp on the Bear River, killing nearly three hundre d men, women, and children. The bloody encounter culminated years of increasing tension between whites and the Shoshonis, who, faced with dwindling lands and food sources, had resorted to theft in order to survive. By the time of the battle, confrontations between the once-friendly Indians and the settlers and emigrants were common.

So it was that "in deep snow and bitter cold"

Connor set forth from Fort Douglas with nearly three hundred men, mostly cavalry, late in January 1863. Intelligence reports had correctly located Bear Hunter's village on Bear River about 140 miles north of Salt Lake City, near present Preston, Idaho. Mustering three hundred warriors by Connor's esti-

Above: Gen. Patrick E. Connor in later years, decorated with his military medals. Right: Unidentified Shoshoni, location and date unknown.

The late Harold Schindler was a former member of the Advisory Board of Editors for UHQand an award-winning historian of Utah and the West

The Bear River Massacre 301

mate, the camp lay in a dry ravine about forty feet wide and was shielded by twelve-foot embankments in which the Indians had cut firing steps. . ..

When the soldiers appeared shortly after daybreak on January 27 [sic], the Shoshonis were waiting in their defenses

About two-thirds of the command succeeded in fording ice-choked Bear River While Connor tarried to hasten the crossing, Major [Edward] McGarry dismounted his troops and launched a frontal attack It was repulsed with heavy loss. Connor assumed control and shifted tactics, sending flanking parties to where the ravine issued from some hills While detachments sealed off the head and mouth of the ravine, others swept down both rims, pouring a murderous enfilading fire into the lodges below Escape blocked, the Shoshonis fought desperately in their positions until slain, often in hand-to-hand combat Of those who broke free, many were shot while swimming the icy river. By mid-morning the fighting had ended

On the battlefield the troops counted 224 bodies, including that of Bear Hunter, and knew that the toll was actually higher They destroyed 70 lodges and quantities of provisions, seized 175 Indian horses, and captured 160 women and children, who were left in the wrecked village with a store of food The Californians had been hurt, too: 14 dead, 4 officers and 49 men wounded (of whom 1 officer and 6 men died later), and 75 men with frostbitten feet. Even so, it had been a signal victory, winning Connor the fulsome praise of the War Department and prompt promotion to brigadier general.1

Controversies over the battle have tainted it ever since For one thing, Chief Justice John F. Kinney of the Utah Supreme Court had issued warrants for the arrest of several Shoshoni chiefs for the murder of a miner. But critics have questioned whether the warrants could legally be served, since the chiefs were no longer within the court's jurisdiction.2 The legality of the federal writs was irrelevant, however, to Colonel Connor, commande r of the California Volunteers at Camp Douglas At the onset of his expedition against the Bear River band, he announced that he was satisfied that these Indians were among those who had been murdering emigrants on the Overland Mail Route for the previous fifteen years. Because of their apparent role as "principal actors and leaders in the horrid massacres of the past summer, I determined to chastise them if possible." He told U.S. Marshal Isaac L. Gibbs that Gibbs could accompany the troops with his federal warrants if he wanted, but "it

1 Robert M Utley, Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865 (New York: Macmillan Co., 1967), 223-24 Other accounts tell of soldiers ransacking the Indian stores for food and souvenirs and killing and raping women See Brigham D Madsen, The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985), 192-93 Madsen's study is the best account of the expedition and of the circumstances surrounding it

2 The Bear River Indian camp, located twelve miles north of the Franklin settlement, was in Washington Territory.

was not intende d to have any prisoners." 3 However—and this is another controversy—there have been many who have questioned whether Connor's soldiers actually tangled with the guilty Indians. Recently discovered new evidence, while it resolves neither of those debates, does address a more fundamental aspect of the encounter that ultimately claimed the lives of twenty-three soldiers and nearly 300 American Indians: that is, Bear River began as a battle, but it most certainly degenerated into a massacre. We have that from a participant, Sgt. William L. Beach of Company K, 2nd Cavalry Regiment, California Volunteers, who wrote an account and sketched a map just sixteen days after the engagement, while he was recuperating from the effects of frozen feet

The sergeant is specific in describing a crucial moment in the four-hour struggle: that point at which the soldiers broke through the Shoshoni fortifications and rushed "into their very midst when the work of death commenced in real earnest." Having seen a dozen or so of his comrades shot down in the initial attack, Beach watched as the tide of battle fluctuated until finally a desperate enemy sought to surrender

Midst the roar of guns and sharp report of Pistols could be herd [sic] the cry for quarters but their was no quarters that day. . . . The fight lasted more than four hours and appeared more like a frollick than a fight the wounded cracking jokes with the frozen some frozen so bad that they could not load their guns used them as clubs[.]

Looking from Battle Creek toward west side of valley where some of the Shoshoni escaped. Charles Kelly photo, USHS collections.

3 "Report of Col P Edward Connor, Third California Infantry, commanding District of Utah," The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington D.C: Government Printing Office, 1897), 185

The "cry for quarters" fell upon deaf ears as the bloody work continued.

In his account, the cavalry sergeant also provided valuable insights concerning the movement of troops as the attack took shape; he carefully recorded the position of each unit and located the Indian camp and its defenders on a map of the battlefield He also charted the course of the river at the time of the engagement and pinpointed the soldiers' ford across the Bear From his map, historians learn for the first time that some of the Shoshonis broke from the fortified ravine on horseback.4 Beach traced the warriors' retreat on the map with a series of lowercase "i" symbols.

The manuscript and map came to light in February 1997 after Jack Irvine of Eureka, California, read an Associated Press story in the San Francisco Chronicle about Brigham D. Madsen, University of Utah emeritus professor of history, and learned that Madsen had written The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre? Irvine, a collector of Northwest documents and photographs, telephoned Madsen that night and told him that he had collected Sergeant Beach's narrative and map. He sent the historian a photocopy and so opened a sporadic correspondence and telephone dialogue that would continue over the span of some eighteen months.

The manuscript has an interesting, if sketchy, pedigree. According to Irvine, he obtained the four pages from the estate of Richard Harville, a prominent Californian and a descendant ofJoseph Russ, an

Battle area as it appeared when CharlesKelly took this photo (possibly 1930s): looking east toward slope that Connor and troops came down. USHS collections.

4 In the past it was believed that the warriors had been cut off from their herd of ponies

5 "Historian Delights in Debunking Myths of Old West," San Francisco Chronicle, February 8, 1997.

*v

early 1850s overland pioneer to Humboldt County who became fabulously wealthy as a landowner and rancher. Harville had an abiding interest in local history and was a founding member of the Humboldt County Historical Society. He also owned a large collection of California memorabilia, which was put up for sale after his death in 1996.

Irvine found the narrative and map folded in an envelope and was intrigued because the documents referred to Bear River, which he at first took to be the Bear of Humboldt County When he found that it was not the northern California stream, he briefly researched the Connor expedition. Although he determined that Joseph Russ had been alive when the regiment was organized in 1861, he could find no connection between the pioneer and the soldier to indicate how the manuscript had come into Russ's possession After his research, Irvine put the document away and thought no more of it until he saw the Chronicle article a year later

Both Irvine and Madsen agreed that the documen t should be made available to scholars and researchers, preferably in Utah The only obstacle was in determining a fair exchange for the four-page manuscript.6 When the Californian suggested a trade for Northwest

Left: Map drawn bySergeant Beach shortly after the Bear River Massacre in 1863, used courtesyofHarold Schindlerfamily. Above: Map of battle site drawn by Brigham Madsen from aerialphotographs shows thepresent course of the Bear River, which may well have changed since 1863. Map isfrom Brigham D. Madsen, The Shoshoni Frontier, courtesy of University of Utah Press.

5 The manuscript was written in ink on a large sheet of letter paper folded in half to provide four pages measuring 19.3 cm by 30.6 cm Beach's map covers the fourth page There are two large tears in the paper, one in the upper right corner of the first page and another across the bottom of the same leaf Evidently, the paper was ripped before Beach began his narrative, for he wrote around the ragged edges, thus preserving the integrity of the account His penmanship is quite legible though flavored by misspellings

Left: Map drawn bySergeant Beach shortly after the Bear River Massacre in 1863, used courtesyofHarold Schindlerfamily. Above: Map of battle site drawn by Brigham Madsen from aerialphotographs shows thepresent course of the Bear River, which may well have changed since 1863. Map isfrom Brigham D. Madsen, The Shoshoni Frontier, courtesy of University of Utah Press.

5 The manuscript was written in ink on a large sheet of letter paper folded in half to provide four pages measuring 19.3 cm by 30.6 cm Beach's map covers the fourth page There are two large tears in the paper, one in the upper right corner of the first page and another across the bottom of the same leaf Evidently, the paper was ripped before Beach began his narrative, for he wrote around the ragged edges, thus preserving the integrity of the account His penmanship is quite legible though flavored by misspellings

documents or photos, Madsen contacted Gregory C. Thompson of the University of Utah's Marriott Library Special Collections. He also contacted me. Special Collections had nothing that fell within Irvine's sphere of interest, but after some months of dickering, Irvine and I were able to reach a mutually acceptable agreement.7 Beach's narrative and map would return to Utah.

Madsen feels that the Beach papers are very important in resolving some of the issues surrounding the encounter Also, he says, the papers can "emphasize and strengthen the efforts of the National Park Service to bring recognition, at last, to the site of this tragic event, which was the bloodiest killing of a group of Native Americans in the history of the American Far West."

Madsen's comment points to the fact that, although Bear River long has been considered by those familiar with its details as the largest Indian massacre in the Far West, scholars and writers continue to deny the encounter its rightful place in frontier history. Yet Beach confirms the magnitude of the massacre when he cites the enemy loss at "two hundred and eighty Kiled." This number would not include those shot attempting to escape across the river whose bodies were swept away and could not be counted.8 While the fight itself has been occasionally treated in books and periodicals, Sergeant Beach's narrative and map are singularly important for what they add to the known record. Here is his account as he penned it:

This View Represents the Battlefield on Bear River fought Jan 29th /'63 Between four companies of the Second Cavelry and one company third Infantry California Volenteers under Colonel Conner And three hundred and fifty Indians under Bear hunter, Sagwich and Lehigh [Lehi] three very noted Indian chiefs. The Newspapers give a very grafic account of the Battle all of which is very true with the exception of the

7 Schindler owned a California-related manuscript that Irvine was willing to trade for the Beach papers. The batde narrative and map are presendy in the possession of the Schindler family.

8 Most histories of the American West mention the massacres at Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864; Washita, Indian Territory, in 1868; Marias River, in 1870; Camp Grant, Arizona, in 1871; and Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890; yet Bear River is generally ignored Body counts vary widely in these histories, but typical numbers of Indian fatalities listed in traditional sources are Sand Creek, 150; Washita, 103; Marias River, 173; Camp Grant, 100-128; and Wounded Knee, 150-200

Sgt Beach's first-person assertion of at least 280 Shoshoni deaths lends additional support to Madsen's claim that the Bear River massacre was the largest in the Far West The toll would almost certainly have been even higher had Connor been able to press his two howitzers into action, but deep snow prevented them from reaching the battlefield in time.

Madsen's book conservatively places the number of Shoshoni dead at 250 It also addresses the question of why Bear River has been generally neglected and advances three reasons: (1) At the time, the massacre site was in Washington Territory, some 800 miles from the territorial capital, so residents of that territory paid little attention; (2) the event occurred during the Civil War, when the nation was occupied with other matters; and (3) Mormons in Cache Valley welcomed and approved of Connor's actions, and some historians may have been reluctant to highlight the slaughter because of the sanction it received from Mormons (See The Shoshoni Frontier, 8, 20-24.) Currently, Madsen says, some traditional military historians are still opposed to using the term "massacre" relative to Bear River

306 Utah Historical Quarterly

positions assigned the Officers which Cos K and M cavelry were first on the ground

When they had arrived at the position they occupy on the drawing Major McGeary [Edward McGarry] gave the commands to dismount and prepare to fight on foot which was instantly obayed Lieutenant [Darwin] Chase and Capt [George E] Price then gave the command forward to their respective companies after which no officer was heeded or needed The Boyswere fighting Indians and intended to whip them. It was a free fight every man on his own hook. Companies H and A came up in about three minutes and pitched in in like manner. Cavelry Horses were sent back to bring the Infantry across the River as soon as they arrived. When across they took a double quick until they arrived at the place they ocupy on the drawing they pitched in California style every man for himself and the Devil for the Indians The Colonels Voice was occasionally herd encourageing the men teling them to take good aim and save their amunition Majs McGeary and Galiger [Paul A Gallagher] were also loud in their encouragement to the men.

The Indians were soon routted from the head of the ravine and apparently antisipated a general stampede but were frustrated in thair attempt Maj McGeary sent a detachment of mounted cavelry down the River and cut of their retreat in that direction Seing that death was their doom they made a desparate stand in the lower end of the Ravine where it appeared like rushing on to death to apprach them But the victory was not yet won. With a deafening yell the infuriated Volenteers with one impulse made a rush down the steep banks into their very midst when the work of death commenced in real earnest Midst the roar of guns and sharp report of Pistols could be herd the cry for quarters but their was no quarters that day Somejumped into the river and were shot attempting to cross some mounted their ponies and attempted to run the gauntlet in different directions but were shot on the wing while others ran down the River (on a narrow strip of ice that gifted the shores) to a small island and a thicket of willows below where they foung [found] a very unwelcome reception by a few of the boys who were waiting the approach of straglers. It was hardly daylight when the fight commence and freezing cold the valley was covered with Snow-one foot deep which made it very uncomfortable to the wounded who had to lay until the fight was over The fight lasted four hours and appeared more like a frollick than a fight the wounded cracking jokes with the frozen some frozen so bad that they could not load their guns used them as clubs No distinction was made betwen Officers and Privates each fought where he thought he was most needed. Xhe report is currant that their was three hundred of the Volunteers engaged Xhat is in correct one fourth of the Cavelry present had to hold Horses part of the Infantry were on guard with the waggons While others were left behind some sickwith frozen hands and feet. Only three hundred started on the expedition

Our loss—fourteen killed and forty two wounded Indian Loss two hundred and eighty Kiled

Xhe Indians had a very strong natural fortification as you will percieve by the sketch within it is a deep ravine {with thick willows and vines so thick that it was difficult to see an Indian from the banks} runing across a smooth flat about half a mile in width. Had the Volunteers been

7

The Bear River Massacre 30

boon in their position all h-1 could not have whiped them The hills around the Valley are about six hundred feet high with two feet of snow on them. . ..

In the language of an old Sport I weaken Trail in the snow

AAAAAAAAA Lodges or Wickeups in Ravine

hi iii iii Retreating Indians

::: ::: ::: Co K, 3rd Infantry

!!!!!!! Cavelry four companies afterwards scattered over the field

Sergeant W. L. Beach. Co. K, 2nd c. C.V. Camp Douglas. Feb. 14th /63

I recieved six very severe wounds in my coat. W. L. Beach

Beach had enlisted in the California Volunteers on December 8, 1861, in San Francisco. After his hitch was up, he was mustered out at San Francisco on December 18, 1864.9 After that, Sgt. William L. Beach may have faded away as old soldiers do, but his recollections of that frigid and terrible day in 1863 at Bear River will now live forever in Utah annals.

9 Fortunately, none of Beach's "wounds" seems to have penetrated beyond the coat; officially the sergeant was listed among the men hospitalized with frostbitten feet. See Brig. Gen. Richard H. Orton (comp.), Records of California Men in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 to 1867 (Sacramento: State Printing Office, 1890), 178-79, 275

308 Utah Historical Quarterly

Waccara's Utes: Native American Equestrian Adaptations in the Eastern Great Basin, 1776-1876

BY STEPHEN P VAN HOAK

BY STEPHEN P VAN HOAK

WACCARA WATCHED with pride as members of the Mexican posse on the far bank of the Mojave River turned and started back for their homes beyond the snow-capped mountains to the west. With his pursuers defeated, Waccara knew that his puwa, or power, would now be unquestioned. He and his people had good reason to be pleased with the results of their winter sojourn to California. Though it would be several days before the remainder of the Ute warriors returned from their scattered horse raids, the hundreds of Mexican-branded cattle and horses already in the Ute camp ensured that the new year would be a good one After a spring of fishing at Utah Lake, the Ute warriors, riding their strong and healthy horses, were likely to have a successful summer hunt on the Great Plains and would return to Utah with an abundance of jerked meat and skins. During the fall months, Waccara's Utes would feast on the buffalo meat but also hunt antelope, deer, rabbits, and other game, and they would harvest seeds, nuts, and berries Their exhausted herd would rest and recover on the grasses of the Sevier Valley, growing strong in preparation for the winter return across the desert to California, where another successful season of equestrian raiding and trading might follow.1

Stephen P. Van Hoak is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in American history at the University of Oklahoma. The author would like to thank Dr. Willard Rollings and Dr. Hal Rothman, University of Nevada- Las Vegas, for their valuable comments, suggestions, and critiques.

1 This description of the yearly cycle of Waccara's band was composed through the use of scattered references from the sources cited in this essay The account features events that were known to have occurred in different years and is intended only to be representative of a typical year for Waccara and his band Sufficient sources do not exist to create a narrative of an entire actual year in the life of Waccara's

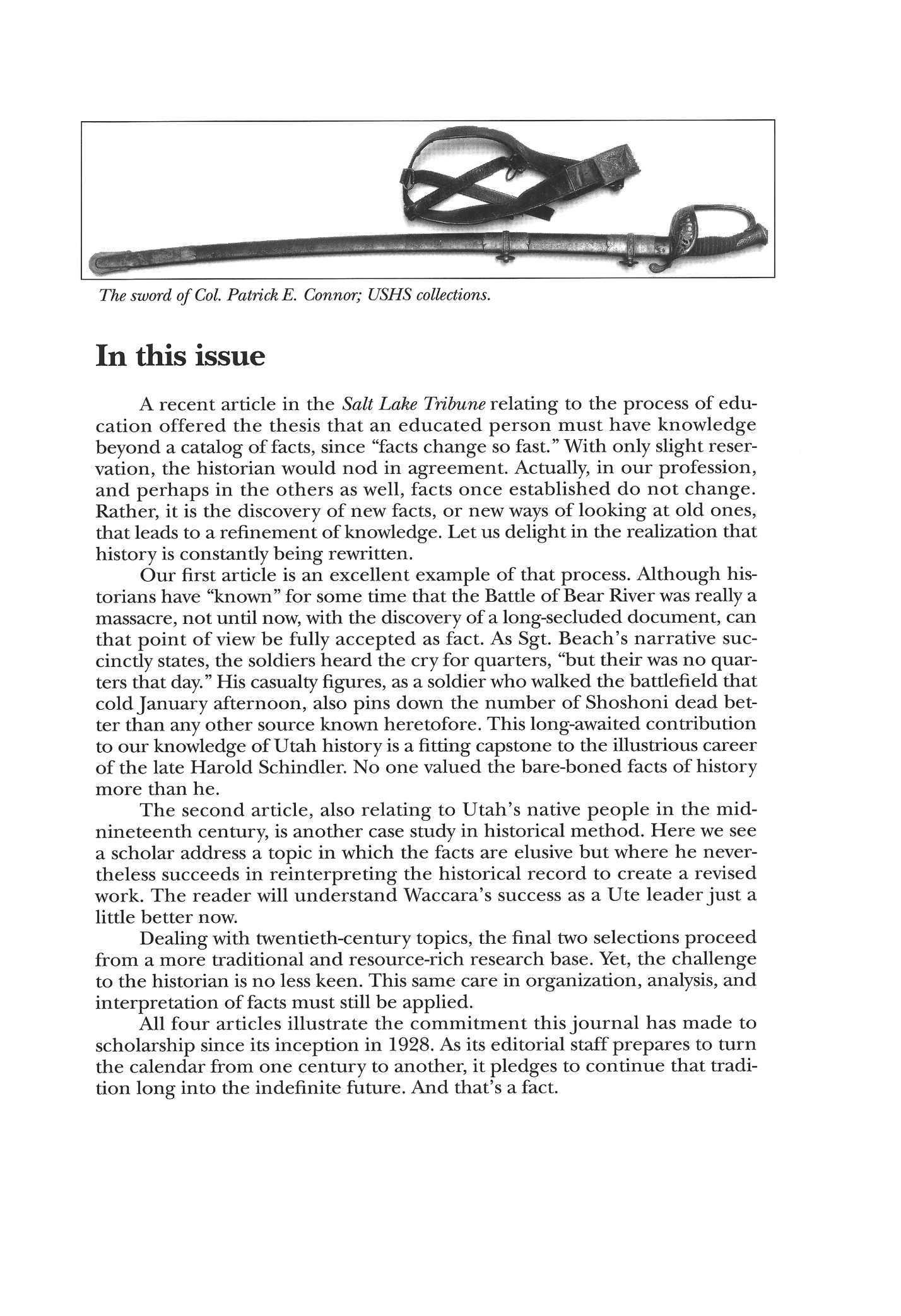

Waccara and his brother Arapeen, by Solomon Carvalho.

The Western Utes were distinct among mounted Native American peoples in both their diversification of food resource exploitation and in the geographic scope of their migrations.2 Although their range and mobility were increased by their acquisition of horses, the Western Utes did not abandon their diversified subsistence pattern to specialize in buffalo hunting, as many Plains equestrian groups did. Waccara's mounted band represented the most conspicuous stage of Western Ute equestrianism, and the success of their annual migratory cycle resulted in their becoming in the mid-nineteenth century one of the most prosperous and powerful mounte d bands west of the Rockies. Waccara's Utes ranged from the Pacific Coast to the Platte River, east of the Continental Divide, following a migratory pattern that circumvented many of the ecological and geographic limitations on successful equestrianism in the eastern Great Basin. Despite their eventual success, however, the Western Utes had not been quick to embrace equestrianism and had not begun to acquire horses until the late eighteenth century, a scant forty years prior to the rise of Waccara. The eastern Great Basin of the eighteenth century was a diverse region that ranged from arid and bleak desert landscapes in the west, to beautiful spring-fed meadows further east in the foothills, to timber- and snow-covered mountains at the basin's eastern extremity. In the higher elevations in the east, numerous mountain streams fed several lakes, the most significant being the freshwater Utah Lake and the briny Great Salt Lake. Beaver were abundant in the streams, and fish and geese abounded in and around the freshwater lakes The dense vegetation in the foothills and mountains supported a large number of small and large game, including deer, antelope, and rabbits.3 These eastern environs were in stark contrast to the arid portions of the Great Basin, and it was around these well-watered hills and mountain slopes, particularly Utah Lake Valley and the Sevier Valley, that the Western Utes made their home.

The Western Utes or Nuciu, as they refer to themselves, had Utes. This essay is based on a master's thesis; for more details and citations, see Stephen P. Van Hoak, "Waccara's Utes: Native American Equestrian Adaptations in the Eastern Great Basin, 1776-1876" (M A thesis, University of Nevada-Las Vegas, 1998)

2 For a brief discussion of differing Native American adaptations to equestrianism, see James F Downs, "Comments on Plains Indian Cultural Development," American Anthropologist 66:2 (April 1964): 421-22

3 For the geography and ecology of the eastern Great Basin, see Ivar Tidestrom, Flora of Utah and Nevada, Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, vol. 25 (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1925), passim; John Wesley Powell, Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah, ed Wallace Stegner (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1962), 110-11, 120-21

310 Utah Historical Quarterly

inhabited the eastern Great Basin for centuries prior to EuroAmerican contact. The Ute creation story alleges that the Utes, along with many other tribes of Native Americans and whites, were released by Coyote, the trickster, from the bag of Wolf, the creator. Each tribe settled in a different region, but Sinawaf (Wolf) proclaimed that the Utes "will be very brave and able to defeat the rest."4 Linguists say that the Utes are a Numic-speaking people whose arrival in the eastern Great Basin is thought to have occurred around 1300 A.D. Though alternative theories exist, one theory posits that the Utes were able to displace the region's previous inhabitants, the agriculturalist Anasazi and Fremont peoples, through superior hunting and gathering adaptations Dividing into numerous groups, the Utes concentrated in areas of high resource density. The group that would come to be known as the Western Utes settled in the eastern Great Basin.5

Specific divisions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Utes are difficult to distinguish, but five distinct historical divisions of Utah Utes, based largely on geography, are commonly recognized by moder n historians and anthropologists. These are the Pahvant, Sanpits, Moanunts, Timpanogots, and, beginning in the 1830s, the Uintahs. Although each division had its own "territory," many Western Utes frequently hunted, gathered, and fished in the territories of other groups, especially at Utah Lake.6

Prior to Euro-American contact, the Western Utes survived in the eastern Great Basin through the exploitation of the varied, though limited, food sources in the region and through the use of seasonal migrations that maximized these resources. In the spring, most Western Utes converged at Utah Lake as trout left the depths of the lake and began their spawning runs into the many feeder streams. The bands feasted throughout the spring on these easily obtained, nearly inexhaustible numbers of fish and on the plentiful waterfowl attracted to the fish. In

4 David Rich Lewis, Neither Wolf nor Dog: American Indians, Environment, and Agrarian Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 22-23

5 David B Madsen, "Dating Paiute-Shoshoni Expansion in the Great Basin," American Antiquity 40:1 (1975): 82-85; Joseph G Jorgensen, "The Ethnohistory and Acculturation of the Northern Ute" (M.A thesis, Indiana University, 1964), 5-15; Anne M Smith, Ethnography of the Northern Utes, Papers in Anthropology no 17 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1974), 10-17; Joel Clifford Janetski, The Ute of Utah Lake, University of Utah Anthropological Papers no 116 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991), 58

6 Donald Callaway, Joel Janetski, and Omer C. Stewart, "Ute," in Handbook of the North American Indians vol 11, Great Basin, ed Warren D'Azevedo (Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 1986), 338-40; Julian Haynes Steward, Aboriginal and Historical Groups of the Ute Indians of Utah: An Analysis with Supplement, in Ute Indians 1, Garland Series, American Indian Ethnohistory: California and Basin-Plateau Indians, ed. David Agee Horr (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1974), passim; Smith, Ethnography, 17-27 Only when the Mormons began to settle in Utah in the late 1840s did observers of Western Utes begin to note the primary residence or divisional membership of particular groups of Utes

Waccara's Utes 311

the summer, resources were far less abundant, and the Utes divided into smaller groups and spread out in search of food Seeds, edible plants, berries, and, to a lesser extent, fish, fowl, and an occasional buffalo formed the basis of their diet throughou t the warm summe r months. The Western Utes continued to live in these small groups throughout the fall. In late autumn they began to hun t the mature large game that was leaving higher elevations in anticipation of winter. They also harvested pinon nuts every few years, whenever a good crop became available, and often cached them as a reserve food source. For most Western Utes, the onset of winter signaled a return to Utah Lake, where fish, cached food, and game wintering in the sheltered river valleys provided them sustenance and where firewood was at hand to give them warmth through the often bitterly cold winter months.7 Mobility and diversity were the keys to Ute survival in the eastern Great Basin. The sociopolitical organization and religion of the Western Utes supported their diversified subsistence cycle. Bilateral, predominantly matrilocal extended families formed the basic social unit in Western Ute culture,8 and in the summer and fall these families usually operated independently in search of resources. Most socioeconomic tasks were gender-specific, with men primarily responsible for hunting and warfare and women generally accountable for food-gathering activities and the skinning and cleaning of animals. Large gatherings were limited to the winter and spring months when many of the Western Utes converged at Utah Lake, but even then families did not surrender their autonomy to the group. Leaders in Western Ute culture were selected to direct only certain specific group activities, such as communal rabbit drives or coordinated raiding or defensive efforts, and these leaders relinquished their authority when the activity was completed.9 Ute religion centered around puwa, or power, a spiritual force that could be harnessed and used by specially trained persons; it was thought to aid the Utes in hunting, raiding, and battle.10 But in the

7 For the yearly subsistence cycle of the pre-horse Western Utes, see Tanetski, Ute of Utah Lake, 31, 36,40

8 In a matrilocal system, husbands leave their families of birth and join their wives' families A bilateral family traces its lineage on both the father's and mother's sides.

9 Because of the overall dearth of primary sources available, descriptions of Western Ute political and social structure are varied and controversial; see Steward, Groups of the Ute, 5-9, 18-20, 63-65, 68-70; Jorgensen, "The Ethnohistory and Acculturation of the Northern Ute," 17-20, 25-33; Smith, Ethnography, 121-27; Janetski, Ute of Utah Lake, 50-51 For an excellent overview of Western Ute culture, see Lewis, Neither Wolf nor Dog.

10 Jay Miller, "Numic Religion: An Overview of Power in the Great Basin of Native North America," Anthropos 78 (1983): 337-54; Gottfried O Lang, A Study in Culture Contact and Culture Change: The Whiterock Utes in Transition, University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 15 (New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1971), 11-12

312 Utah Historical Quarterly

eighteenth century the Western Utes found their puwa insufficient to prevent the intrusion of their enemies, the Shoshoni, into valuable Ute hunting grounds in the Uinta Basin of northeastern Utah.

The military dominance of the Shoshoni over the Western Utes in the eighteenth century was an outgrowth of Shoshoni acquisition of horses.11 The horse was originally introduced into New Mexico by the Spanish in 1598, and for nearly a century the Spanish managed to preserve their monopoly on these animals. But after the Pueblo revolt of 1680, the vast Spanish herds fell into Indian hands, and in the next few decades the horse quickly diffused to the plains north and east of New Mexico. By 1700, the horse "frontier" extended beyond the Great Plains and into the Intermountain region to the west, where the Shoshoni began to acquire their first animals Yet the Western Utes, though much closer to New Mexico, the original source of horses, were unable to acquire horses until nearly a century later.12 The explanation for the slow spread of horses to the Western Utes centers aroun d the environmental and geographic setting of the eastern Great Basin. These factors imposed severe limitations upon the acquisition and useful employment of horses

The most important uses of horses involved combat and hunting. In battle, the power and speed of horses dramatically increased the deadliness of shock weapons. Horses also enhanced pursuit and evasion capabilities, allowing a rider to avoid more numerous unmounted foes and to apprehend slower unmounted enemies.13 The speed of horses was also invaluable in hunting and pursuing large game, particularly the slow-moving buffalo on open plains. Unmounted buffalo hunting required large numbers of warriors to surround the buffalo herd in order to harvest a few animals, but mounted warriors could operate independently, with each pursuing and killing multiple buffalo As a beast of burden, the horse further enhanced buffalo hunting

11 Silvestre Velez de Escalante, The Dominguez-EscalanteJournal, trans Fray Angelico Chavez, ed Ted J Warner (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), 50, 60; Steward, Groups of the Ute, 12-13 Guns were not a significant factor in the Shoshoni dominance over the Utes, as neither tribe was able to obtain guns in large numbers until the 1820s, after the introduction of the fur trade west of the Rockies and after Mexican independence, following which the enforcement of the New Mexican ban on trading guns to the Indians was eased; see Frank Raymond Secoy, Changing Military Patterns of the Great Plains Indians, 17h Century through Early 19h Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 4-5, 20, 60, 84-85.

12 Francis Haines, "Horses for Western Indians," American West 3:2 (Spring 1966): 5-15, 92; Secoy, Changing Military Patterns, 20-22, 27-29, 33 Haines's dating of Western Ute acquisition of horses is inconsistent with the historical record; see Van Hoak, 'Waccara's Utes," 18-20

13 Secoy, Changing Military Patterns, passim; John C Ewers, The Horse in Blackfoot Indian Culture, with Comparative Material from other Western Tribes, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin no 159 (Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1969), 309-10

Waccara's Utes 313

by allowing transportation of larger quantities of meat and in providing the means for wider geographical migrations in search of buffalo. Equestrianism also had significant liabilities, as horses were not merely objects or tools and required sustenance and care in order to survive The constant need to provide water and feed forced equestrian peoples not only to spend the vast majority of their time in locales with abundant water and forage but also to move frequently as forage became exhausted.14 Care of horses and the manufacturing of saddles, saddle bags, and other equipment for horses diverted considerable time from traditional activities and subsistence efforts. Possession of horses also increased the likelihood of enemy raids, necessitating protective and defensive efforts. Even if the horses were well-fed and guarded, herds inevitably sustained losses as a result of disease, aging, and, most significantly, severe winter conditions.15

Winter aggravated many of the difficulties of equestrianism and presented new problems Thick layers of snow or ice blanketing grass needed to be cleared so that horses could feed. Much of the nutritional value of grasses retreated underground in winter, so winter forage provided less energy at precisely the time of year that the horses needed more energy in order to survive the elements. The low nutrient density of winter grasses and the increased danger of disease in crowded and stationary conditions necessitated frequent moves by equestrian peoples. But snow made shifting camp more problematic, and it drained precious energy from both people and animals. Even when horses survived the winter, they often did so malnourished and weakened by disease, which caused serious long-term effects on their health and reproduction—and on that of their potential offspring. Severity of winter was the predominant limiting factor in the size of most Native American herds, and increased winter severity in a region decreased the value of horses in that area. 16

The replenishment of herds depleted by raids, disease, or winter required breeding, raiding, or trading, all of which posed difficulties.

14 For the specific nutritional requirement s of horses, see Jame s E. Sherow, "Workings of the Geodialectic: High Plains Indian s an d Thei r Horses in the Region of th e Arkansas River Valley, 1800-1870," Environmental History Review 16:2 (Summer 1992): 69-70; Alan J Osborn, "Ecological Aspects of Equestrian Adaptations in Aboriginal North America," American Anthropologist 85:3 (September 1983): 576; Ewers, The Horse, 40-41

15 For the limitations and liabilities of equestrianism, see Ewers, The Horse, 37-42, 50-52; Osborne, "Equestrian Adaptations," 584-85 ; Elliot West, The Way to the West: Essays on the Central Plains (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 20-27

16 Ewers, The Horse, 42-46 , 124-26; Sherow, "Geodialectic," 70-76 ; Osborne , "Equestrian Adaptations," 566-85; West, Way to the West, 23-26 Branches and bark were often used as emergency winter forage

314 Utah Historical Quarterly

Breeding was often an ineffective and troublesome method for increasing herd size, not only because of the damaging impact of winter on reproductive ability but also because of the extensive time required to break horses for riding. Raiding for horses eliminated the need to break horses and was therefore a less time-consuming technique of herd enlargement, but horse raiding also risked failure and possible battle casualties The most obvious drawback of trading for horses was the necessity and difficulty of obtaining a desirable product to exchange, the most coveted such commodity being slaves. Despite these difficulties, eventually many equestrian Native Americans developed a system of obtaining horses by raiding other tribes and Euro-Americans for horses and captives, then bartering the captives to Euro-Americans for more horses.17

The inability of the Western Utes to adopt equestrianism in the eighteenth century rested upon many of the limitations outlined above Although there was an abundance of water and forage in the lush foothills and valleys of the eastern Great Basin, winters there were characterized by high winds, heavy snowfall, and temperatures as low as thirty degrees below zero. Further, opportunities to use the horse for hunting buffalo were severely restricted by the Shoshoni occupation of the Uinta Basin and Salt Lake Valley, the only adjoining regions frequented by buffalo.18 And, unlike their Eastern Ute kinsmen in the Rocky Mountains, the Western Utes had few occasions to trade for horses, surrounded as they were with bleak and arid landscapes adjoining their lands to the southeast, southwest, and west, and their enemies, the Shoshoni, on the other sides of the compass. 19

The potential risk and cost for the unmounted Western Utes to raid the mounted Shoshoni for horses was prohibitively high In effect, for eighteenth-century Western Utes, the cost of acquiring and maintaining horses throughout the harsh winter in the eastern Great Basin was greater than the potential benefits of equestrianism. Thus,

17 Useful studies of raiding and trading adaptations to equestrianism include Frank McNitt, Navajo Wars: Military Campaigns, Slave Raids, and Reprisals (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972); Anthony McGinnis, Counting Coup and Cutting Horses: Intertribal Warfare on the Northern Plains, 1738—1889 (Evergreen, CO: Cordillera Press, Inc., 1992); Secoy, Changing Military Patterns. Native Americans preferred smaller "ponies" that were characterized by greater speed, endurance, foraging ability, and surefootedness than "American" horses had; see Ewers, The Horse, 34; Herbert S. Auerbach, "Old Trails, Old Forts, Old Trappers and Traders," Utah Historical Quarterly 9 (January-April 1941): 16

18 Stephen P Van Hoak, "The Other Buffalo: Native Americans, Fur Trappers, and the Western Bison, 1600-1860," unpublished manuscript in the author's possession; Karen D Lupo, "The Historical Occurrence and Demise of Bison in Northern Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly 64 (Spring 1996): 168—80.

19 Janetski, Ute of Utah Lake, 23; Smith, Ethnography, 30-31; Powell, Arid Region, 119-20; Steward, Groups of the Ute, 21, 58 A few scattered Navajos and Eastern Utes likely traded periodically with the Western Utes, but these tribes also sought to increase the size of their herds and were therefore loath to trade away their horses.

Waccara's Utes 315

the few horses they acquired at that time were either consumed as food or traded away. 20

The excessive cost of acquiring horses in the eastern Great Basin was remedied after 1776, when Spanish missionary Francisco Atanasio Dominguez led the first recorded Euro-American expedition into the Great Basin. At Utah Lake, Dominguez found the Western Utes unmounted and eager to procure Spanish trade and assistance against their Shoshoni enemies.21 Although Dominguez's promise to return to build settlements and a mission there did not come to fruition, the expedition was instrumental in opening a trade corridor from New Mexico into the eastern Great Basin. In the decades that followed, trade flourished despite Spanish bandos prohibiting such activity.22 The Western Utes bartered beaver pelts and captives procured from neighboring tribes to New Mexican traders seeking the enormous profits these commodities, especially the captives, brought in New Mexico.23 The Utes were thus able to bypass Indian middlemen and purchase horses and guns directly from their source. At the end of the eighteenth century, when the cost of horses was no longer prohibitive, the Western Utes began to acquire these animals in increasing numbers. They were soon able to dislodge the Shoshoni from their hunting grounds in the Uinta Basin.24

Horses provided a variety of benefits to equestrian peoples The acquisition of horses, or kavwds as they were known to Western Utes, allowed the Utes to significantly expand the range, efficiency, and diversity of their resource exploitation. In addition to providing them with a greater capacity to search for and hunt buffalo, the horse also enabled the Utes to more effectively raid for horses and captives. Unmounted tribes such as the Southern Paiute became exceedingly

20 Haines, "Horses for Western Indians," 12-13

21 Velez de Escalante, Dominguez-EscalanteJournal, 54—56 Speaking to Dominguez, the Utes referred to their enemies to the nort h and east as "Kommanche," but the Comanche had already moved onto the Great Plains by the eighteenth century, and the people the Utes spoke of were almost certainly Shoshoni "Komantcia" was a Numic term that mean t "my adversary."

22 Joseph P Sanchez, Explorers, Traders, and Slavers: Forging the Old Spanish Trail, 1678—1850 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1997), 91-102; Joh n R Alley, Jr., "Prelude to Dispossession: Th e Fur Trader's Significance for the Norther n Utes and Southern Paiutes," Utah Historical Quarterly 50 (Spring 1982): 107-13; Joseph J Hill, "Spanish and Mexican Exploration and Trade Northwest from New Mexico into the Great Basin, 1765-1853," Utah Historical Quarterly 3 (January 1930): 16-19

23 For the extensive slave market in New Mexico, see Lynn Robinson Bailey, Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1966), and McNitt, Navajo Wars.

24 By the 1820s and 1830s, the Western Utes had plentiful guns as well as horses; see Jedediah S Smith, The Southwest Expedition ofJedediah Strong Smith: His Personal Account of theJourney to California, 1826-1827, ed George R Brooks (Glendale, CA: Arthu r H Clark Co., 1977), 42-43 ; Warre n Angus Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 1830-1835, ed J Cecil Alter and Herbert S Auerbach (Salt Lake City: Rocky Mountain Book Shop, 1940), 216-19 For die expulsion of the Shoshoni from the Uinta Basin, see Janetski, Ute of Utah Lake, 20; Steward, Groups of the Ute, 14, 24, 66

316 Utah Historical Quarterly

vulnerable to Ute raids for captives, while mounted tribes such as the Shoshoni became new potential targets of Ute raids for both horses and captives The horse increased the mobility and range of the Western Utes, aiding their traditional migratory hunting and gathering activities in the summer and fall, and the mounted Utes could more easily transport the food and animal skins they obtained. Trade opportunities were also significantly improved by the range and carrying capacity of the horse, allowing Western Utes to more easily acquire Euro-American tools and weapons such as muskets These weapons enhanced Ute hunting and combat efficiency.

Even as equestrianism began to thrive in the eastern Great Basin in the 1820s and 1830s, the massive expansion of the fur trade west of the Rockies, the abundance of fish at Utah Lake, and the northeastward retreat of the buffalo discouraged the Western Utes from specializing in bison hunting. The fur trade was extremely lucrative to the Utes, who traded readily obtained beaver pelts and other animal skins for horses, guns, and other Euro-American goods. Bison hides were of comparatively little value in trade, so in the fall Western Utes primarily hunted deer and beaver rather than buffalo.25 The vast amounts of easily obtained fish available during the spring spawning season at Utah Lake discouraged the Utes from hunting buffalo during that time. Furthermore, the depletion of bison in the Uinta Basin and Salt Lake Valley by the late 1820s limited Western Ute opportunistic buffalo hunting, forcing Utes seeking bison to travel ever greater distances on "big hunts."26 Thus, the buffalo did not become the dominant food source of the equestrian Western Utes as it did for many Plains tribes. The contrast in the degree of bison specialization between the Western Utes and Plains Indians was evident in the term the Utes used to describe Plains Indians: kwucutika, or "buffalo-eating Indians."27 But continued resource diversification by the Western Utes did serve to minimize the adverse impact of the retreat of the bison, and in the 1820s and 1830s this diversity and the burgeoning of exploitable food resources available to the equestrian Utes led to a significant upsurge in Western Ute population.28

25 Alley, "Prelude to Dispossession," 105-17, 122-23 The equestrian Western Utes had excellent access to Euro-American trade, as they were astride both the north-south trapper trade route and the east-west Spanish Trail, both of which were established by 1830, and they were also near numerous trading posts in Utah; see Alley, "Prelude to Dispossession," 116; and Jorgensen, "Ethnohistory," 68-69

25 Van Hoak, "Other Buffalo," passim; Lupo, "Bison in Northern Utah," 168-80; Van Hoak, "Waccara's Utes," 42-51, 82-84

27 Smith, Ethnography, 275

28Jorgensen, "Ethnohistory," 20

Waccara's Utes 317

"SnakeJohn " at Ute camp in Whiterocks, Utah, 1899. Ofcourse, nophotos exist of Waccara's camp and horses. Photo courtesy of the Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library, University of Utah.

The advent of equestrianism in the eastern Great Basin also deeply imprinted Western Ute social and political organization as the Western Utes began to organize into mounted bands. Larger than the Ute family unit but smaller than "tribal" gatherings, these bands typically included from ten to one hundred families, with usually four to five horses per family.29 Western Ute trading, raiding, and buffalo hunting were all enhanced by formation of bands, which were flexible, mobile, and usually strong enough in numbers to ward off enemy attack. Ute leaders directed the activities of these bands with more authority and for longer periods than did earlier traditional Western Ute leaders, and leadership positions increasingly became hereditary. Yet in the early nineteenth century most Western Utes continued to live outside these band structures, and most of those that did coalesce into bands did not do so on a permanent basis After a hunt or raid was over, most of the men returned to more traditional activities and subsistence efforts.30

One equestrian band leader who rose to prominence during these changes in Ute culture was Waccara Born in Utah Lake Valley in the early nineteenth century, Waccara was a witness to the first

29 For examples of early Western Ute bands, see Smith, Jedediah Strong Smith, 41-46; Ferris, Rocky Mountains, 216-20 By comparison, though studies vary, tribes of the Great Plains who specialized in buffalo hunting typically included hundreds of warriors and their families in each band with from three to thirteen horses per person; see Ewers, The Horse, 24-28, 138-39; West, Way to the West, 21; Sherow, "Geodialectic," 68; Osborne, "Equestrian Adaptations," 584

30 For the sociopolitical effect of band formation, see Jorgensen, "Ethnohistory," 25-33; Smith, Ethnography, 121-27; Steward, Groups of the Ute, passim; Ewers, The Horse, 247-49

318 Utah Historical Quarterly

acquisition of horses by his tribe. According to him, his father purchased the tribe's first horse from Spanish traders but, knowing little about the care of horses, kept the animal tied u p for several weeks until it died of starvation Horses acquired thereafter fared better, however, and Waccara began to see his people form into equestrian band s for hunt s an d raids. His father was the leader of a ban d of Western Utes until a tragic dispute with other Western Utes resulted in his death around 1840, whereupon Waccara immediately assumed leadership of the band and moved them south to the Sevier Valley Shortly thereafter, according to Waccara, he had a spirit visitation, an event often associated in Ute culture with the securing of puwa by an individual.31 In the years to come, Waccara would use this puwa to aid his people as they embarked on a new system of equestrianism.

By the 1840s a host of internal and external pressures compelled the Western Utes to expand and intensify their system of equestrianism As increasing populatio n approache d the limit of available resources, they began to experience food shortages.32 The fur trade began a gradual and lasting decline when buffalo robes became the preferred items of exchange to Euro-American traders.33 At the same time, the continued retreat of the buffalo "frontier" was expedited by Euro-American traffic along the Oregon Trail; in addition to killing buffalo directly, travelers also reduced buffalo populations indirectly by disrupting ecosystems and importing new diseases.34 As the distance to the buffalo increased, the Western Utes needed ever-greater numbers of horses for pursuit and transportation. Further influencing the need for larger horse herds was the effect that decades of equestrianism had had in transforming horses into highly desired symbols of status and wealth in Western Ute society.35 The response of many Western Utes to these pressures was to implement a new yearly migratory cycle that provided greater access to traders, to potential targets of raids,

31 Dimick B Huntington, Vocabulary of the Utah and Sho-sho-ne or Snake Dialects, with Indian Legends and Traditions, including a Brief Account of the Life and Death ofWah-ker, the Indian Land Pirate (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Herald Office, 1872), 27-28; Fawn M Brody, ed., Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1962), 277-78. Sources alternatively date the year of Waccara's birth as 1808 or 1815 The most common variations of the spelling of Waccara include Walker, Walkara, and Wakara Waccara's name meant "brass" or "yellow" in Ute After his alleged spirit visitation in the 1840s, Waccara claimed he was given a new name—Pannacarra-quinker, or Iron Twister For the granting of puwa through dreams and the use of such puwa, see Miller, "Numic Religion," 339, and Lewis, Neither Wolf nor Dog, 31.

32 Jorgensen, "Ethnohistory," 21

33 Alley, "Prelude to Dispossession," 113

34 West, Way to the West, 72-78

35 For an excellent study of status and wealth in Native American equestrian societies, see Bernard Mishkin, Rank and Warfare among the Plains Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992); also see Ewers, The Horse, 28-30, 249, 314-16; Smith, Ethnography, 33; Ferris, Rocky Mountains, 239-40.

Waccara's Utes 319

and to buffalo, and that allowed enlargement of their horse herds in defiance of environmental constraints. The leader who directed these Western Ute pioneers was Waccara.

The new seasonal migration of Waccara's Utes began with a winter journey to California, which served to mitigate the detrimental effects of the severe Utah weather on the size and health of the Ute herd. With its mild climate and abundant pasture lands, California was a virtual paradise for the Utes' horses, which grew healthy and strong during the winter months. Initially, these trips were primarily trading expeditions, but eventually the Utes were enticed by the abundance of Californian horses into raiding for horses as well.36 The thinly populated and dispersed Mexican ranches and settlements could muster little defense against Waccara's well-armed warriors.

A typical expedition to California by Waccara's band began in the late fall with a long journey southwest over the Spanish Trail. The Western Ute horses, robust from months of grazing in the Sevier Valley grasslands, were laden with a multitude of fine pelts and skins obtained earlier that fall. As Waccara's Utes journeyed along the trail, their passage through the broken and arid lands was eased by the cool winter temperatures and the few sites along the trail that afforded good pasturage and water. Pausing at these sites, Waccara's Utes rested and recruited their horses, and they often pressured the unmounted and bow-armed Southern Paiute inhabitants of these sites to trade away some of their women and children.37 Continuing along the trail, the Utes eventually emerged through the San Bernardino Mountains and proceeded to visit friendly ranchers and traders met on previous expeditions or through the fur trade. In addition to bartering their pelts, skins, and captives to these traders for horses and EuroAmerican goods, the Utes also procured the use of the traders' land

36 Huntington, Vocabulary of the Utah, 27; George William Beattie and Helen Pruitt Beattie, Heritage of the Valley: San Bernardino's First Century (Pasadena, CA: San Pasqual Press, 1939), 65-66 ; Georg e Washington Bean, Autobiography of George Washington Bean: A Utah Pioneer of 1847 and his Family Records, ed Flora Diana Bean Hom e (Salt Lake City: Utah Printing Co., 1945), 55 Horses bred so well in the mild climate and abundan t pasture lands of California that Euro-Americans slaughtered thousands of them every year to prevent overpopulation; see Clifford J Walker, Back Door to California: The Story of the Mojave River Trail, ed Patricia Jernigan Keeling (Barstow, CA: Mojave River Valley Museum Association, 1986), 122-23 Tales of this abundance of horses probably reached the Western Utes through fur traders and Mexican traders traveling along the Spanish Trail Western Utes may have first journeyed to California in the 1830s, but n o significant migrations or raids by Utes likely occurred until those directed by Waccara in the 1840s, when Californian sources first began to specifically mentio n Ute raids; see Ferris, Rocky Mountains, 251; Eleanor Lawrence, "The Old Spanish Trail from Santa Fe to California" (master's thesis, Berkeley, 1930), 66-100.

37 Stephe n P Van Hoak , "And Wh o Shall Have the Children: Th e India n Slave Trad e in the Southern Great Basin," Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 41 (Spring 1998): 1-25; also see Huntington , Vocabulary of the Utah, 27; Daniel W.Jones, Forty Years among the Indians: A True yet Thrilling Narrative of the Author's Experiences among the Indians (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1960), 48

320 Utah Historical Quarterly

as a safe haven for their women and children, a grazing area for their animals, and a base of operations for the warriors. They then began a long series of increasingly large-scale horse and cattle raids. As Mexican resistance organized and stiffened, these raids culminated in scattered flight by the Western Utes with their prizes through the myriad of mountain canyons and into the desert Pausing on the eastern side of the mountains, Waccara's people reassembled and slaughtered their cattle, jerking the meat for sustenance during the long journey back to Utah.38 Returning through the desert, Waccara usually again demanded women and children from the Paiutes, occasionally offering in exchange horses that were unlikely to survive the remainder of the journey. Within a few weeks, Waccara's Utes reached the extensive pasture lands of southwestern Utah, where they rested and recruited their expanded herd.39 In this new equestrian system, winter served to increase, rather than decrease, the size and quality of the Western Ute herd

Waccara's Utes usually remained with their herd in southwestern Utah for several weeks. Many of the Utes' horses were weakened and undernourishe d from their journe y through the desert, and the Western Utes arrived in Utah just as luxuriant grasses began to emerge from melting snow. Increasingly dependen t on their horses, the Western Utes were, in effect, "chasing grass"—migrating seasonally to areas with abundant forage. From California in December and early January, to southwestern Utah in late January and February, to the Sevier Valley in central Utah in March and early April, the Western Utes responded to the needs of their horses by providing them with access to grass during the months when deep snow covered the grass further north at Utah Lake. By April or May, the grass was green at Utah Lake, and Waccara's Utes converged there with most other Western Utes for their traditional spring gathering.

The spring gathering at Utah Lake remained an integral part of

38 For Waccara's expeditions to California, see Gustive O Larson, "Walkara, Ute Chief," in LeRoy R Hafen, ed., The Mountain Men and theFur Trade oftheFar West: Bibliographical Sketches of the Participants by Scholars of the Subject and with Introductions by the Editor, vol 2 (Glendale, CA: Arthur H Clark Co., 1965), 341-44; Juan Caballeria, History of San Bernardino Valley from the Padres to the Pioneers (San Bernardino: Times-Index Press, 1902), 103-104; Beattie, Heritage of the Valley, 65-66, 84; Robert Glass Cleland, The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850-1880 (San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1964), 65-66; Huntington, Vocabulary of the Utah, 27-28; Lawrence, "Spanish Trail," 86-100; Jones, Among the Indians, 39; Kate B. Carter, ed., "The Indian and the Pioneer," Daughters of Utah Pioneers Lesson for October 1964 (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1964), 92; Journal History of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, microfilm copy available in Marriott Library, University of Utah, entry dated March 4, 1851.

39 Beattie, Heritage of the Valley, 66; George Douglas Brewerton, Overland with Kit Carson, A Narrative of the Old Spanish Trail in 48 (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1930), 100; John C Fremont, Narratives of Exploration and Adventure, ed Allan Nevins (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1956), 417

Waccara's Utes 321

the modified annual migratory cycle of Waccara's Utes. As they had done in the past, Waccara's people feasted on trout as a variety of visitors arrived in the valley to trade.40 Seeking Waccara's Paiute captives came Navajos offering their well-crafted blankets and New Mexican slave traders bartering guns, ammunition, knives, and other EuroAmerican products.41 The large annual New Mexican caravans returning from California coveted Waccara's strong and healthy horses as well as his captives, and they offered similar items.42 Many Western Utes who had remained in Utah during the previous winter also desired Waccara's robust horses as replacements for their dilapidated herds. In addition to trading, the spring gathering also provided time for dances, festivals, horse races, and other cultural activities that were essential in preserving Western Ute cohesion and identity.43 With the coming of summer, however, the Western Utes again scattered, with Waccara's Utes "chasing grass" eastward to the Great Plains and the buffalo.

Annual summer buffalo hunts on the Plains provided Waccara's Utes with an alternative to the more limited food sources available in Utah during that time. Summer on the Great Plains—typified by mild temperatures, plentiful forage, and the gathering of buffalo to mate— was an ideal time for buffalo hunting Waccara's Utes brought their swiftest horses for the hunt as well as numerous sturdy pack animals and some cattle as an emergency food source in case of a delay in finding buffalo Once they found a large herd, the Ute warriors with their bows and arrows quickly dispatched enough buffalo to fully load their pack horses. In the summer, unlike other seasons, buffalo bull meat was quite palatable, and the Western Utes feasted on whatever meat they could not jerk and transport back to Utah. They cleaned and tanned the buffalo hides and used them to manufacture bags, parfleches, clothing, horseshoes, and lodgings. Though the shorthaired summer hides were little valued by fur traders, Waccara's Utes still likely stopped at fur-trading posts on their return journey, bartering some of their skins, jerked meat, and horses for guns, ammuni-

40 Bean, Autobiography, 51; Journal History, May 22, 1850; Fremont, Narratives, 419; Annual Report of the Commissioner ofIndian Affairs for the Year 1855 (Washina;ton, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1855) 522-23. ° &

41 James Harvey Simpson, Report ofExplorations across the Great Basin of the Territory of Utahfor a Direct Wagon Routefrom Camp Floyd to Genoa, in Carson Valley, in 1859, Vintage Nevada Series (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1983), 35; Smith, Ethnography, 252; Journal History, May 2, 1853; Lawrence, "Spanish Trail," 100-16; Jones, Among the Indians, 48.

42 Lawrence, "Spanish Trail," 46-65

48 Janetski, Ute of Utah Lake, 40 Social fission and tribal fragmentation were a common byproduct of equestrianism; see West, Way to the West, 20, 68

322

Historical Quarterly

Utah

tion, and liquor.44 By September, Waccara and his band were back in Utah.

In the fall, Waccara's warriors rested their weary horses and set down their bows in favor of guns. 45 As they had don e for centuries, the men spread out into the woods in search of game; the women gathered nuts, berries, and wild plants. After a few weeks of hunting, Waccara's people often visited the Navajos or New Mexicans to the south or the fur-trading posts to the east to barter some of their pelts and skins for guns, ammunition, and blankets.46 Later, as the cold winter weather began to descend upon Utah, Waccara's Utes loaded their remaining pelts and skins onto their fresh and rested horses and once again set out for California to replenish their herd While en route, the Utes burned the grass at choice locations in order to induce earlier and more prolific growth the following spring when they returned from California.47

Bag of dried chokecherries (perhaps pemmican, madefrom meat and chokecherries pounded together). Used courtesy ofManuscripts Division, Marriott Library, UofU.

By the early 1840s Waccara began to have a continuous, if somewhat variable, following of Western Utes. As was the case with all large Western Ute gatherings, membership in Waccara's "band" constantly fluctuated, as many families or individual warriors joined him only for

44 The Western Utes apparently ranged as far as the Platte River in search of buffalo; see Bean, Autobiography, 105; also see William L Manly, Death Valley in '49, Lakeside Classics, ed Milo Milton Quaife (Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1927), 102-11, and Carter, Indian and the Pioneer, 94 These buffalo hunts occasionally brought the Utes into conflict with tribes of the Intermountain and Plains regions; see Bean, Autobiography, 98; Garland Hurt, "Indians of Utah," in Simpson, Report, 461; Carter, "Indian and the Pioneer," 74-75; Steward, Groups of the Ute, 208; Smith, Ethnography, 247-52. For Plains forage and weather, see West, Way to the West, 22, and Secoy, Changing Military Patterns, 24-25 For buffalo hunting, see Ewers, The Horse, and Van Hoak, "Other Buffalo." Bows were the Utes' preferred weapon in hunting buffalo; guns were more difficult to aim, fire, and reload while the hunter was mounted

45 Guns, likely as a result of their superior range and penetrative power, were preferred by Western Utes over bows for hunting game other than buffalo; see Carter, "Indian and the Pioneer," 121, and Secoy, Changing Military Patterns, 19

46 These trips to New Mexico occasionally took the form of raids, although the relative dearth of horses in New Mexico as opposed to California discouraged the Utes from raiding the former; see Hurt, "Indians of Utah," 461; "Reminiscences of the Early Days of Manti," Utah Historical Quarterly 6 (October 1933): 123

47 Charles Preuss, Exploring with Fremont: The Private Diaries of Charles Preuss, CartographerforJohn C. Fremont on His First, Second, and Fourth Expeditions to the Far West, ed and trans Erwin G Gudde and Elisabeth K Gudde (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958), 87

Waccara's Utes 323

a few hunts or raids and then returned home to more traditional activities The band was usually small, limited by the relatively few food sources for both people and animals west of the Rockies. Waccara was never accompanied by more than forty to fifty families, with about seven horses per family. In contrast, Great Plains Indian bands could number in the thousands, with five to thirteen horses per person. 48

The numerous benefits of Waccara's yearly equestrian cycle gradually became apparent to the Western Utes. By migrating to regions with abundant pasture lands in both winter and summer, Waccara's band could maintain healthier and more numerous horses.49 The increased access to large game and trade enjoyed by Waccara's Utes was evidenced by the large number of high-quality blankets, guns, knives, rawhide bags, and skin lodges in their camp, distinguishing their material culture from that of other Western Utes.50 By leaving the eastern Great Basin during winter and summer, when food sources were most limited, and by obtaining lavish supplies of cattle and storable jerked buffalo meat, Waccara's Utes significantly augmented their yearly food supply

Waccara's success in obtaining horses and trade and in directing successful hunts and raids was, to other Western Utes and Native Americans, evidence of his puwa. 51 Western Ute warriors found that joining Waccara on his yearly cycle of hunting, raiding, and trading could be very lucrative, and many of these warriors and their families began to remain with him throughout the year. Native Americans and Euro-American explorers, trappers, and travelers began to fear and respect the power and influence of Waccara and his band. But Waccara's puwa and the continued practice of his yearly cycle of equestrianism were soon tested by the intrusion of a new people into Western Ute lands.

The arrival of the Mormons in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 initially complemented the yearly cycle of Waccara's Utes by providing them with an improved outlet for the proceeds of their raids and an

48 West, Way to the West, 21.

49 On one raid alone, 150 Utes led by Waccara purportedly captured more than one thousand horses Though both these figures are likely exaggerated, the netting of about seven horses per warrior is probably accurate and is indicative of the high numbers of horses often possessed by Waccara's Utes; see Lawrence, "Spanish Trail," 87-90; Jones, Among the Indians, 39-41; Huntington, Vocabulary of the Utah, 27-28

50 Brewerton, Overland with Kit Carson, 101; Manly, Death Valley, 103, 104, 107; Fremont, Narratives, 417

51 For Waccara's leadership skills, see Lawrence, "Spanish Trail," 87-90; Jones, Among the Indians, 39-41; "Early Days in Manti," 123 Some Euro-Americans referred to him as "Napoleon of the Desert" or "Hawk of the Mountains"; see Jones, Among the Indians, 39, and Journal History, January 15, 1851.

324 Utah Historical Quarterly

enhanced source of Euro-American products. Horses fetched high prices in Salt Lake City as overland travelers on the Oregon Trail detoured there seeking replacements for their exhausted, diseased, or malnourished horses.52 The Mormons sought both the meat of the buffalo to supplement their diet and bison hides for their clothing.53 Buckskin suits became quite fashionable among the Mormons, who repeatedly paid the Utes higher prices for their skins than did the fur traders.54 The Mormons also bartered with the Utes for many of their Paiute child captives, whom they hoped to raise in their homes to become "white and delightsome" according to church doctrine.55 In exchange for these commodities, Waccara's Utes received not only such familiar items as guns, ammunition, knives, and blankets but also cattle, oxen, and other livestock, which served the Utes as a year-round secondary food source. Ute trade with the Mormons was more profitable, convenient, and diversified than it had been with any other trading partners.

Although the Mormons and Western Utes found commo n ground through their mutually beneficial trading relationship, they were diametrically opposed in their views and usage of land and resources. The Mormons arrived in Utah with a belief that nature was imperfect and that, rather than adapt to nature, one should strive to change and improve it. Unlike the Western Utes, who adapted to limited resources through dispersal and migration, the Mormons reacted to the limitations of their environment by concentrating their popu-

52 Journal History, June 13, 1849, March 4, 1851; Juanita Brooks, "Indian Relations on the Mormon Frontier," Utah Historical Quarterly 12:1-2 (January-April 1944): 6 In 1850 a good "Indian" pony could sell for up to $50.

53 Solomon F. Kimball, "Our Pioneer Boys," Improvement Era 11 (September 1908): 837; Bean, Autobiography, 55 Early Mormon settlers hunted for buffalo on the Plains in addition to trading for buffalo products

54 Journal History, June 2, 1849, June 13, 1849, April 21, 1850; Brooks, "Mormon Frontier," 6

55 Van Hoak, "Who Shall Have the Children?"

Waccara's Utes 325

Two Utes: taken by Savage and Ottinger studio, n.d. Used courtesy of Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library, UofU

lation for support and by altering their ecosystem through the creation of new resources. The Mormons brought their own domestic plants and animals to Utah and required comparatively little from nature—specifically, they needed areas for settlement that had abundant water, timber, good soil, and forage for their livestock. Unfortunately, the only such areas in Utah were already used by the Western Utes This placed the Mormons at odds with the Western Utes, whose seasonal migratory use of land was not considered by the Mormons to be "valid" usage. To the Mormons, only those who "improved" the land should be able to use it, and within a few years after their arrival in Utah, Mormon fences, corrals, roads, and settlements cut through most of the best Western Ute lands Waccara's band and others returning from seasonal migrations became "intruders" on their own land.56