s g H M CO CO ^ < o r d g w s g W M

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

KENNETH L. CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1995

JANICE P. DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan,1994

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1994

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1995

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

RICHARD W. SADLER, Ogden,1994

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden,1995

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

Utah Historical Quarterly wasestablished in 1928to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801)533-3500 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00.

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 l/4 or 3 */2 inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage ispaid atSalt Lake City, Utah.

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICAL. QUARTERLY

SUMMER 1994 / VOLUME 62 / NUMBER 3 IN THIS ISSUE 203 CRISIS IN UTAH HIGHER EDUCATION: THE CONSOLIDATION CONTROVERSY OF 1905-7 ALAN K. PARRISH 204 "ALITTLE OASIS IN THE DESERT": COMMUNITY BUILDING IN HURRICANE, UTAH, 1860-1920 W. PAUL REEVE 222 KEETLEY, UTAH: THE BIRTH AND DEATH OF A SMALL TOWN MARILYN CURTIS WHITE 246 UTAH'S CCCs: THE CONSERVATORS' MEDIUM FOR YOUNG MEN, NATURE, ECONOMY, AND FREEDOM BETH R. OLSEN 261 AN ADVENTURE FOR ADVENTURE'S SAKE RECOUNTED BYROBERT B.AIRD EDITED BY GARY TOPPING 275 BOOKREVIEWS 289 BOOKNOTICES 295

UTl")JoVJcX

Contents

1994 Utah State Historical Society

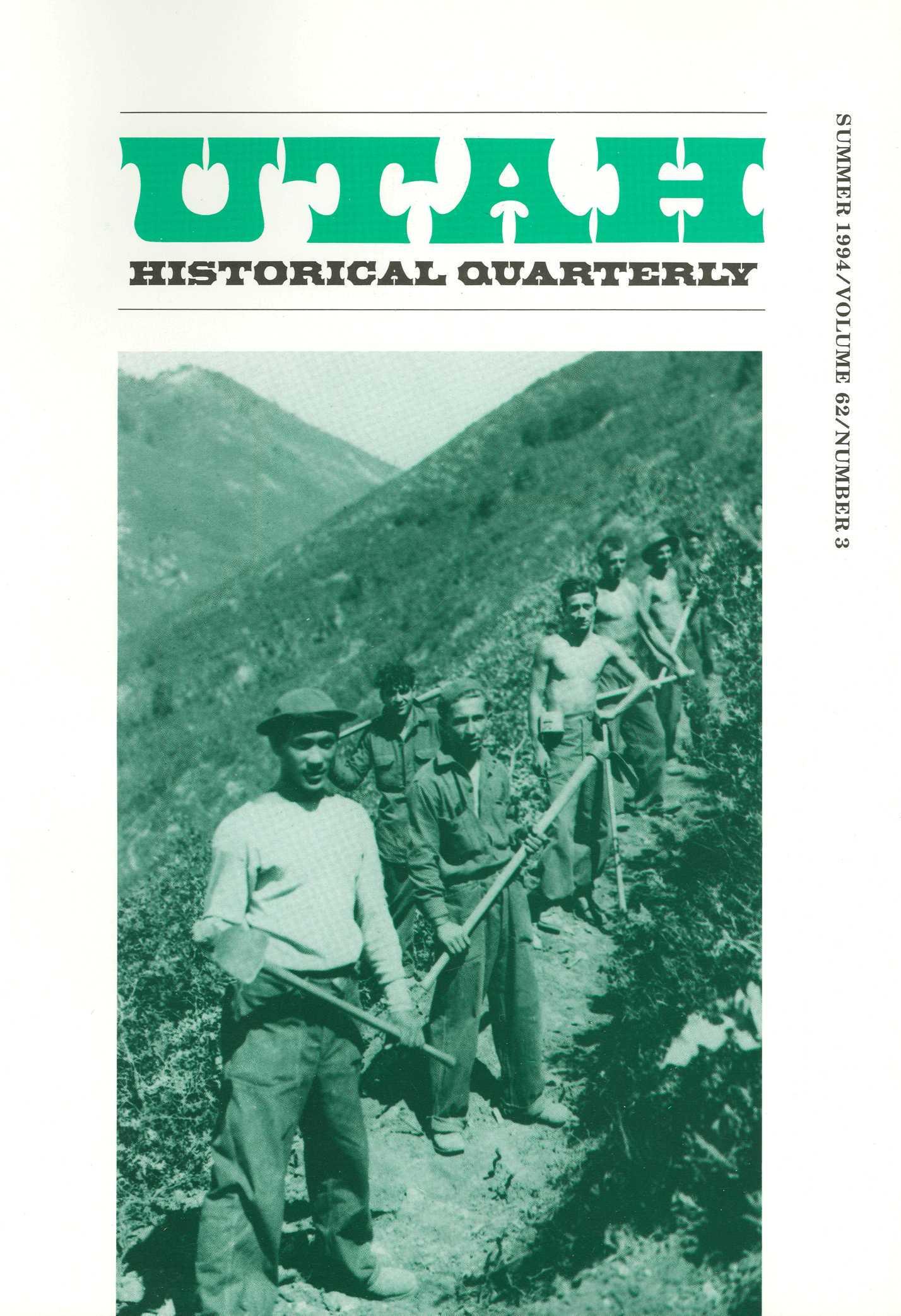

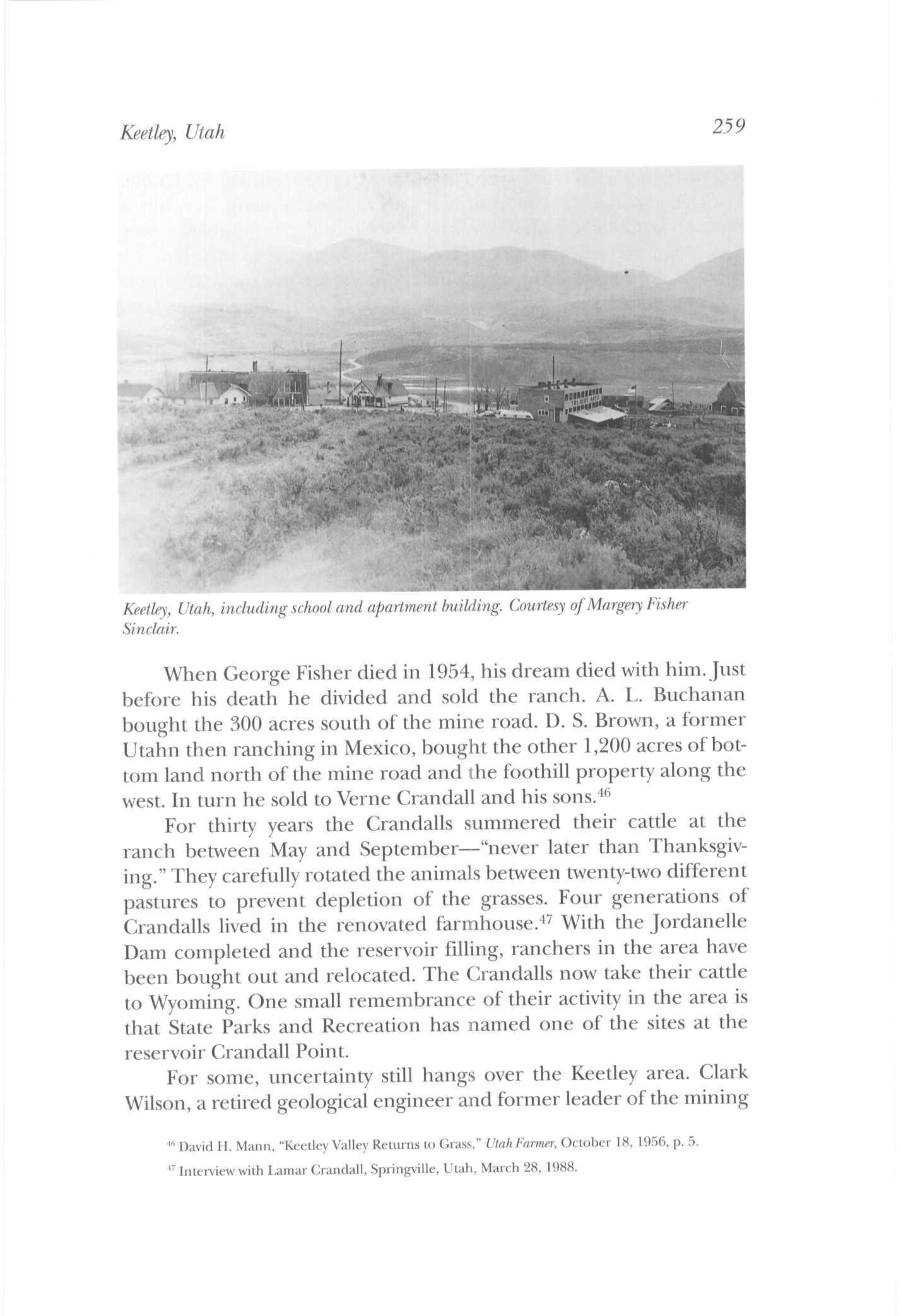

THE COVER CCC workersfrom State Camp S-206 constructed a trailfrom Camel Pass to an erosion area in the mountains east ofProvo and Springuille. USHS collections.

© Copyright

MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY Kidnapped from That Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists

KEN DRIGGS 289

Dreams, Visions, and Visionaries: Colorado Rail Annual No. 20 STEPHEN L CARR 290

LOUISE TEAL Boatwomen of the Grand Canyon: Breaking into the Current GARY TOPPING 291

WILLIAM G. HARTLEY. My Best for the Kingdom: History and Autobiography ofJohn Lowe Butler, a Mormon Frontiersman....STEPHEN B. SORENSEN 292

ROBERT WOOSTER Nelson A. Miles and the Twilight of the Frontier Army

PAUL L. HEDREN 294

Books reviewed

In this issue

Public education, especially its funding, often generates controversy in Utah. Some readers may recall the media coverage J. Bracken Lee and George D. Clyde received decades ago when they grappled, in quite different ways, with this thorny subject An earlier governor, John C Cutler, found himself at the center of a debate during 1905-7 over the future of the Agricultural College of Utah in Logan. Along with many legislators and citizens concerned about the lack of high schools in some rural areas, he believed the ACU was wasting scarce state funds by duplicating courses available at the University of Utah Others feared that the ACU was losing sight of its agricultural mission as its curriculum continued to expand under the leadership of William J. Kerr whose vision embraced the traditional university. The consolidation controversy detailed in the first article affected the careers of several key players and provided political drama as it moved toward resolution.

The following two articles take us to the small towns of Hurricane and Keetley and the challenges of building communities in Washington and Wasatch counties respectively The first study analyzes demographic data, while the second weaves its narrative from personal recollections. Both include dramatic episodes and remarkable individuals struggling to survive economically.

Next we see how the Civilian Conservation Corps shaped the lives of the unemployed who left home and family behind to work on various projects on the public lands in Utah. Although the CCC camps provided adventure of a sort for city boys, that aspect of the experience was only incidental to their work, training, and achievements But adventure for adventure's sake was the goal of the two young men whose trek through the San Juan back country in the summer of 1923 is chronicled in the final article. In overcoming unforeseen difficulties, though, they too gained a priceless sense of accomplishment.

Agricultural College of Utah, Logan. USHS collections.

BY ALAN K PARRISH

Crisis in Utah Higher Education: The Consolidation Controversy of 1905-7

Buildings at the Agricultural College of Utah in Logan, left to right: 1891 dormitory later used by the School ofDomestic Arts to 1935, Smart Gym built in 1910, and the president's home. The plowing of Old Main Hillfor a victory garden in 1918 seems to symbolize the victory that proponents of agricultural education achieved a decade earlier. USHS collections, courtesy ofA. J. Simmonds.

Dr Parrish is associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University

DURING 1905-7 A BATTLE WAS WAGED OVER the maintenance of Utah's institutions of higher learning. At the center of this controversy was the question of whether to consolidate the Agricultural College of Utah (ACU, now Utah State University) with the University of Utah (U of U). In addition to fomenting serious divisions among Utah's principal educators, the issue divided both houses of the legislature and was the chief political agenda item of the governor. The course followed shaped Utah's higher education profile for decades The controversy had its most immediate impact on the lives and careers of three distinguished educational leaders: John A. Widtsoe, William Jasper Kerr, and William S. McCornick.

At age eleven, John Andraes Widtsoe immigrated to Logan, Utah, from Norway After completing his courses at Brigham Young College, he graduated from Harvard,joined the ACU faculty, and obtained his doctorate at the prestigious Georg Augustus University in Goettingen, Germany. Ashis career progressed he served as director of the Experiment Station at the ACU, principal of the School of Agriculture at Brigham Young University, president of ACU, and president of the U of U. For three decades he was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

William Jasper Kerr was born and raised in Richmond, Utah. He attended the University of Deseret and Cornell. He, too, climbed the academic ladder, first asafaculty member at the U of U and later aspresident of Brigham Young College, president ofACU, president of Oregon State Agricultural College (now Oregon State University), and commissioner of higher education for Oregon.

William S McCornick was the first president of the Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce, twice a member of the Salt Lake City Council, the first president of the Alta Club, and president, vicepresident, and director of several banks, mining companies, railroads, and land and cattle companies. He was treasurer of Rocky Mountain Bell Telephone Company and an original member and president of the Board of Trustees of ACU, serving from 1890 to

, 205

1907.1 McCornick's influence is of particular note because he was not a member of the dominant religion in the state.

Within a two-year period all three men left the ACU. At the regular meeting of the Board of Trustees of the ACU on July 8, 1905, Widtsoe was dismissed. On March 21, 1907, McCornick tendered his resignation as president of the Board of Trustees, and, a week later, on March 28, 1907, Kerr resigned after serving seven years as ACU president The consolidation controversy brought these giants to the lowest ebbs of their professional lives.

The Land Grant Act of 1862 (the Morrill Act) made 30,000 acres of federal land available for every senator and representative from each state Proceeds from the sale of such lands were to be used to establish and fund college programs for the industrial classes of the nation Their emphasis was on agriculture and the mechanical arts. The Hatch Act of 1887made an additional $15,000 available for experiment stations associated with the land-grant colleges. With these federal acts in mind, Anthon H. Lund presented a bill in the Utah House of Representatives on February 28, 1888, that created the Agricultural College of Utah It passed unanimously in both houses and was signed into law by Territorial Gov. Caleb W.West on March 8, 1888. The Lund Act provided $25,000 to purchase land and erect buildings. The cornerstone of the main building at the ACU was laid on July 27, 1889, and its doors were officially opened the first week of September 1890 As the new college in Logan progressed, certain lawmakers began to worry that courses at the ACU duplicated those at the U of U, creating a substantial waste of money Although the land-grant ACU was a product of federal legislation, the legislature could decide whether to use the federal funds for the university or for a separate institution. This controversial question was carefully considered by the legislature in 1894and apparently resolved at the constitutional convention in 1895 when the delegates affirmed the existence of the two separate schools.2

Nationally, nineteen states and one territory chose consolidation to achieve land-grant legislation that provided college programs for the industrial classes at existing institutions, while seventeen

206 Utah Historical Quarterly

1 Orson F Whitney, History of Utah, 4 vols (Salt Lake City: G Q Cannon 8c Co., 1904), 4:624-26; J Cecil Alter, Utah, the Storied Domain, 3 vols (Chicago & New York: The American Historical Society Inc., 1932), 2:285-86; Kate B. Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, 20 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1958-77), 10:337-39

2 Constitution of the State of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1895), Article X, Section 4

states and two territories established separate institutions. In the fall of 1906 this national division set the stage for the debate over whether to consolidate the ACU and the U of U. This issue became a major political controversy in state elections and in the sessions of the state legislature. Across the state public education was still undeveloped, and secondary education was not available in many places. Many felt that funding high schools for all areas of the state was a higher priority than maintaining two institutions of higher education. Most citizens thought that the small number of students attending the two colleges did not justify the operating costs

The strongest advocate of consolidation was Gov John C Cutler,3 who appealed to the Senate and House on February 2, 1905, to appoint a joint committee to make a thorough study of the situation and then "formulate recommendations as to legislation."4

After three weeks of investigation the ten-memberjoint committee presented two reports to the legislature. Five members favored an amendment to the state constitution, arguing that "the State cannot possibly maintain two separate institutions aspiring to become universities, and make each one an institution creditable to the State of Utah."5 They recommended that the ACU be made a department of the U of U permanently located in Salt Lake City. Their proposed constitutional amendment required a two-thirds majority vote of the Senate. Only ten of the twelve needed votes were obtained and the

5 SenateJournal. Utah, 1905, p 408

The Consolidation Controversy 207

Gov. John C. Cutler. USHS collections.

3 Heber M Wells, the state's first governor and Cutler's immediate predecessor, was also concerned about duplication He sought to resolve the problem by bringing the two governing boards together in a special meeting. See Board of Regents Minutes, University of Utah, January 24, 1903.

4 Herschel Bullenjr., "The University of Utah-Utah Agricultural College Consolidation Controversy 1904 to 1907 and 1927," p. 2, manuscript in author's possession.

bill failed The otherfivejoint committee members felt that "the duplication of courses at the institutions mentioned is a matter of serious and mature thought."6 Their view became Senate Bill 150, passed by a unanimous vote,7 which recommended the formation of a special commission. Such a commission was created and charged with the difficult task of finding away to control the two schools and to avoid the "duplication of studies consistent with the finances and the educational advantages of the State ."8

Although further action on consolidation awaited the College Commission report, the legislature had passed a bill, signed by Governor Cutler on March 20, 1905, that limited expansion of the college's curriculum by defining the courses of study the ACU could offer. They included:

agriculture, horticulture, forestry, animal industry, veterinary science, domestic science and arts, elementary commerce, elementary surveying, instruction in irrigation . . . , military science and tactics, history, language, and the various branches of mathematics, physical and natural science and mechanic arts. . . .But the Agricultural College shall not offer courses in engineering, liberal arts, pedagogy, or the profession of law or medicine.9

On June 30, 1906, the College Commission submitted three reports. The members had evidently found consensus on the thorny issue of consolidation as difficult to achieve as it had been for the legislature'sjoint committee. The majority report filed by five members found expensive duplication at the two institutions and recommended a constitutional amendment to combine the two schools "on one site."10 The report bore the signatures of two members from Salt Lake County and members from three counties south of Salt Lake County. The first minority report, signed by two members from Cache County where the ACU was located, argued that the constitutional provision for the perpetuation of both the U of U and the ACU had passed by an overwhelming vote of 98 to 3 An extreme emergency did not exist and, therefore, a constitutional amendment was not needed. They recommended continuation of both institu-

6 Ibid., p 402

7 Ibid., p 403

8 Ibid See also HouseJournal. Utah, 1905, Joint Senate and House Bill No 1, March 1905, p 647

9 Laws of the State of Utah 1905, pp 125-26

10 Summary of the Majority Report of the College Commission, 1906, p 10, copy in Papers of John A Widtsoe, Special Collections, Utah State University, Logan

208 Utah Historical Quarterly

tions with each school limiting its work to specific departments to minimize duplication. The second minority report, signed by the member from Weber County, which lies between Cache County and Salt Lake County, recommended that the two institutions be united under one president and one board to eliminate their "unseemly rivalry." These recommendations were widely discussed during the election campaign of 1906, the southern counties of the state favoring consolidation while the northern counties remained torn on this politically significant issue.

Governor Cutler, who had been an ex officio member of the commission, offered his suggestions to ajoint session of the legislature onJanuary 15, 1907.The budget requests of the two institutions concerned him greatly: "They are now asking for over $579,000, or over one-third of the expected revenue for the next two years." To satisfy "even a reasonable part of these demands," he asserted, would "deprive the primary and secondary schools of the State and other institutions and departments, of funds absolutely necessary for their support." The legislature should at the very least, the governor believed, place the ACU and the U of U "under one board, with the proviso that one sum be asked for both schools." Cutler went on to decry the intense rivalry for state funds that had developed between the schools and the persistent lobbying by school officials who "should work together for the educational betterment of the youth."11

The alumni associations of both institutions actively campaigned across the state. After fifty-three years the U of U had an extensive list of alumni and a record of successfully providing for the educational needs of the state Aside from competition for funds, the U of Uwas under no threat in the controversy and stood to make significant gains by absorbing programs developed by its perceived rival in Logan.

At the ACU the consolidation controversy ran deep and deserves careful analysis The very composition of the college seemed to justify the opposing views held by some of its principal leaders. The college had twomajor divisions and subsequent differences in emphasis. President Kerr oversaw the faculty, academic programs, welfare of students, and fiscal maintenance of the college. Widtsoe, director of the experiment station, supervised research, the operation of laboratories

" Bullen, 'The Consolidation Controversy," pp 11-12

The Consolidation Controversy 209

and experimental farms, and the dissemination of information through published bulletins, a farm newspaper, and farmers' institutes These differing responsibilities undoubtedly influenced their opposing views on consolidation. Kerr held the traditional view that college work should extend to all areas of learning His interests paralleled those of great educators in established American universities. He endeavored to build a faculty and student body that would advance classical academic subjects and prepare students for life. Widtsoe, in establishing the experiment station, had produced rich benefits for the agricultural industry of the state. His statewide "student body" followed the plow, planting and reaping as aided by the learning of those at the college, on its experimental farms, and in its laboratories He believed that this hands-on work experience was the essence of the ACU Although Widtsoe did not oppose academic learning, the broad educational agenda of Kerr surely threatened Widtsoe's vision of agriculture and education.

Addressing the annual convention of the Association of American Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations in 1905,Kerr defended his belief that land-grant colleges should offer the broad curriculum espoused by conventional colleges in addition to the distinctive "technical courses required in the development of the varied industries and resources of the country."

12 Guided bythat philosophy, the seven years of the Kerr administration (1900-1907) represent a period of remarkable expansion; "the whole Institution started moving and spreading,

119-24

210 Utah Historical Quarterly

WilliamJ. Kerr. Trom A History of Fifty Years.

12 W.J Kerr, "The Relation of the Land-Grant Colleges to the State Universities," reprinted from the Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Convention of the Association ofAmerican Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations, U S Department of Agriculture, Office of Experiment Stations, Bulletin No 164, pp

especially in the Engineering department."13 Faculty rank advancement policies adopted the criteria embraced at traditional colleges, and college governance and the rights of students similarly evolved In 1901 the semester system replaced the quarter system In Kerr's first biennial report, he noted that the departments of the college had been expanded into six schools with each school growing to meet the needs of the expanding curriculum. The school of general science, for example, now included "the broad field of general science, mathematics, language, history and literature."14 In 1902 the Board of Trustees added courses in mining and electrical engineering. In 1903 a school of music was established, and summer school was added to the college calendar. Kerr did not wish to preside over a school that "merely catered to the immediate needs of the time, he sought to establish a real college expanding into the various fields of knowledge."15

Kerr was the principal proponent of expansion at the ACU and thus the principal rival of consolidation. Ironically, the debate that ensued in the Senate, the House, and the press on the topic often focused on his earlier views as a delegate to the 1895 constitutional convention where he had been the most ardent supporter of consolidation—stating that "under no circumstances" would he favor separate institutions. His lengthy testimony then, published in the proceedings of the convention, became convenient fodder for those who favored consolidation ten years later.

Widtsoe reported that he laid low in this controversy, limiting his opinions to official faculty meetings That was an understatement Available materials do not reveal his personal assessment of the matter until much later Three years after the controversy wasresolved, Widtsoe responded in a lengthy letter to an official in Alberta, Canada, where a proposed agricultural college was the subject of debate. The official specifically wanted to know if Widtsoe thought agricultural colleges were "most successful when combined with a university or when each is conducted separately."16 Widtsoe answered that this had been a crisis in Utah for eleven years and the

14 Ibid., p 62

15 Ibid., p 63

Consolidation Controversy 211

The

13 William Peterson, as quoted in Joel Edward Ricks, The Utah State Agricultural College: A History of Fifty Years (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), p. 59.

16 J W Woolf to J A Widtsoe, January 8, 1910, box 102, Papers ofJohn A Widtsoe, Special Collections, Utah State University, Logan

most prominent subject in at least two sessions of the legislature. He felt duplication was an unnecessary concern if attendance at one institution required additional staff Another argument for consolidation was more compelling. When agriculture is taught as part of many other professional subjects, "the prospective farmer has a chance to measure himself with men in other pursuits and in that way acquires a certain dignity and faith in himself that only comes by such contact."17 Then he emphasized the need to have at the head of the college someone devoted to its agricultural mission:

William S. McCornick. USHS collections.

There are some three or four agricultural colleges as departments of universities in the United States that maintain a very high rank There is a very much larger number of separate institutions that stand high among the schools of the country It would generally be found that the attendance of agricultural students is, in proportion to the population, very much greater in a separate agricultural college than in one combined with a university. All in all, while the question is difficult of full solution, it seems clear that the agricultural college of the future which is to serve the people in the best waywill be a separately maintained institution.18

To understand Widtsoe'sviewsduring the crisis, it may be useful to look at those expressed by his assistant, LewisA. Merrill.19 Widtsoe was president of the organization that produced the weekly newspaper, the Deseret Farmer, and Merrill was the editor during the controversy. This newspaper provides insight into the polarization that grew between Merrill and the policies advanced by Kerr Merrill charged

17 Widtsoe to Woolf, January 1910, ibid

18 Ibid.

19 In June 1905 Merrill so opposed Kerr's policies that he sent a letter of resignation to the Board of Trustees Days later he sent a letter to Kerr seeking to withdraw his resignation In his appeal he wrote, "Why am I singled out? Surely you don't mean to infer that I alone am the offender, because John A Widtsoe isjust as deep in this as I am." LoganJournal, June 17, 1905, p 1

212 Utah Historical Quarterly

that the expansion of the ACU under the Kerr administration was detrimental to the school's programs and emphasis on agriculture. This overarching concern clouded the consolidation issue Had agriculture been given the attention Widtsoe and Merrill perceived it should have, perhaps any expressed views on the issue of consolidation would have been significantly different.

Changes in the ACU Board of Trustees aggravated tensions at the school. Governor Cutler, who opposed Kerr's policies, attacked them through appointments he made to the board, replacing three of its seven members with loyal supporters—Thomas Smart, Lorenzo Stohl, and Susa Young Gates—early in 1905

The scrutiny of Governor Cutler, the examination of the joint committee and special commission, the composition of the Board of Trustees, and the growing sentiment for consolidation in the legislature brought burdensome pressures to the ACU Board and President Kerr During the summer of 1905 the board's president, William S.McCornick was traveling abroad and did not attend board meetings. Reports of a board meeting scheduled for May 12 hint at problems to come. The three new appointees opposed continuance of the meeting and forced an adjournment against the opposition of the three members of the old board News coverage reported that the action amounted to the opening gun of a conflict being fired. The primary purpose of the meeting was to confirm appointments for the next year and take action against persons the president opposed. The Salt Lake Herald reported, "President Kerr has discovered that two of the professors on his staff are not in harmony with him, if they are not altogether disloyal."20

Then, on June 2, 1905, pursuant to the call of the newly appointed trustees, a meeting of the board was held Motions for the election of college officials in a block vote failed in a standoff between old and new board members. Trustee Smart had moved that Kerr "be elected President of the College Faculty for the ensuing year" and that Widtsoe remain as director of the experiment station and professor of chemistry and Merrill as agronomist with the station and professor of agronomy. 21 It was evident from the vote that Widtsoe or Merrill or both would not be rehired. With the growing tension both Widtsoe and Merrill may have considered leaving the

20 "A Sensible View of the College Situation," LoganJournal, May 16, 1905, p 1

21 Minutes of the Board of Trustees, ACU, June 2, 1905, p 143

The Consolidation Controversy 213

ACU.22 On Saturday,June 3, 1905, the Deseret Evening News, Salt Lake Tribune, and Provo Daily Enquirer all reported that the two men had submitted their resignations from the ACU following the June 2 meeting The Tribune got to the crux of the matter:

Of course the refusal of the old members of the board to support the motion simply means that they do not intend to consider the two professors at all, and that they will make no concessions whatever. It was so taken by the two men in question, who, upon hearing of the action of the old members, immediately resigned and accepted other positions

When seen by the Tribune last night, Dr Widtsoe said: "This is all I have to say—I have resigned because of the conditions which exist at the Agricultural college at the present time, and because of unjust and false rumors circulated upon the streets of Logan and throughout the State, which the directors of the institution have not seen fit to correct, though they knew these rumors were false."

Professor Merrill was equally brief and to the point—"I must frankly state that I am not in harmony with President Kerr's policy in administration of the Agricultural college It is not favorable to agricultural work He is attempting to make a university out of it instead of an agricultural college 3

OnJune 5when the Board of Trustees met in regular session no allusion was made to the reported resignations. Kerr read his report with recommendations regarding changes in the faculty for the ensuing year. 24 In the afternoon session a motion to sustain Kerr, Widtsoe, and Merrill by a block vote was made repeatedly by Trustee Stohl, a new appointee Each time it failed or was ruled out of order Adopting Kerr's report would amount to the dismissal of both Widtsoe and Merrill. The minutes of the next board meeting, three days later on July 8, reveal that Kerr intended to stick by his report.25 By then, McCornick had returned from his travels and stood solidly behind the embattled college president Kerr's report lists the names and salaries of the college faculty for the following year, with the names of Widtsoe and Merrill conspicuously missing. According to Kerr,

22

In a letter to G H Brimhall, president of Brigham Young University, May 3, 1905, Widtsoe wrote what appears to be the acceptance of a job offer made earlier: "I am now ready to accept the proposition that you made some days ago. .. . My term of office in the A. C U. closes Sept. 1st, 1905."

Brimhall Presidential Papers, box 11, folder 3, BYU Archives

23 "Row in State Institution," Salt Lake Tribune, June 3, 1905, p 2

24 Minutes of the Board of Trustees, ACU, June 5, 1905, p 147

25 Ibid., July 8, 1905, p 153

214 Utah Historical Quarterly

. . . These Professors had given ample evidence that they were not in harmony with the faculty or in sympathy with the policy of the Board of Trustees or the President One of the fundamental requisites to success in all educational institutions is . . . unquestioned loyalty to the institution and its authorities. He further stated that he was prepared to prefer specific charges against each of these professors, and to call witnesses before the Board and submit other evidence. ... in as great detail ... as might be desired by the Board.26

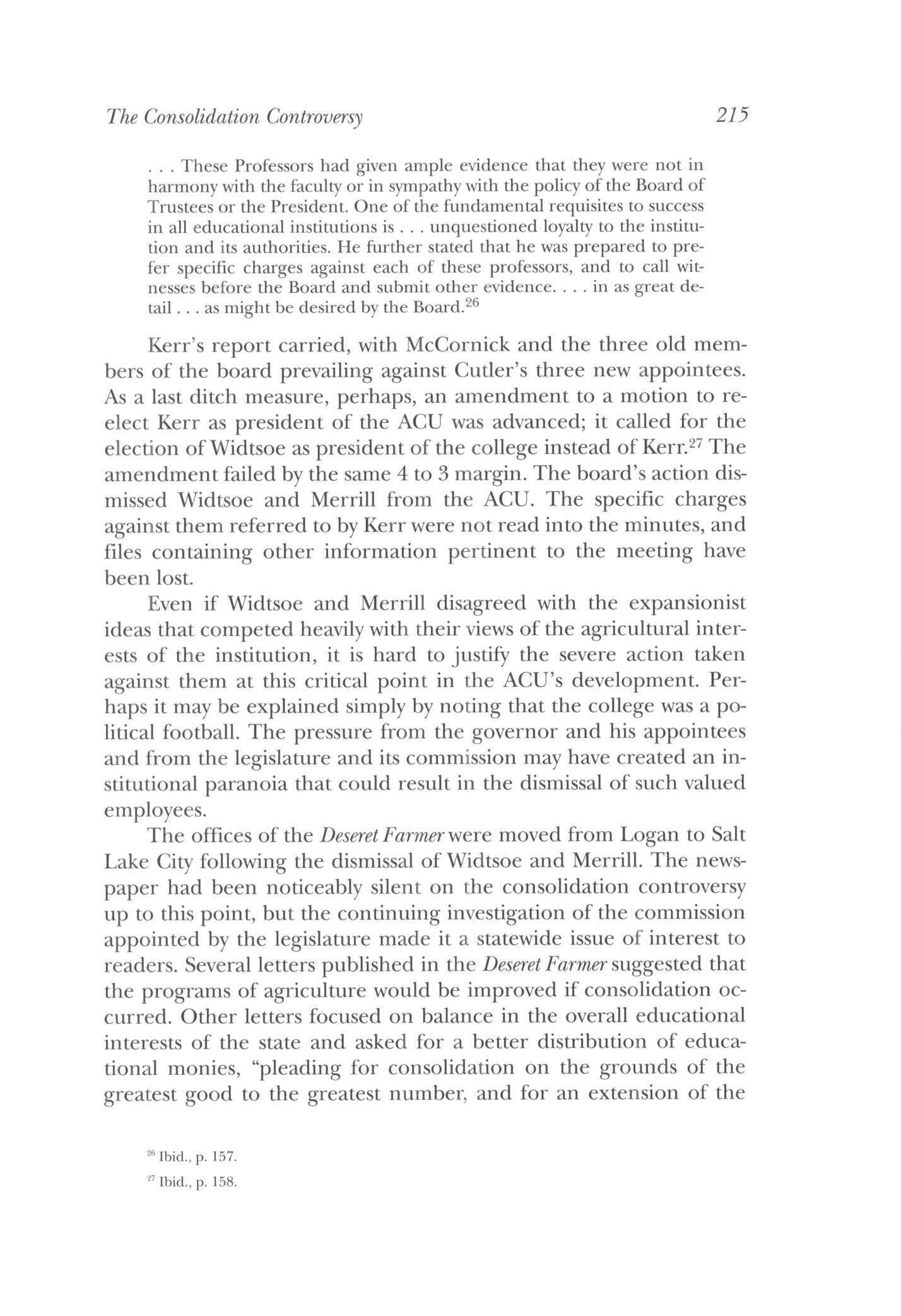

Kerr's report carried, with McCornick and the three old members of the board prevailing against Cutler's three new appointees. As a last ditch measure, perhaps, an amendment to a motion to reelect Kerr as president of the ACU was advanced; it called for the election of Widtsoe as president of the college instead of Kerr.27 The amendment failed by the same 4 to 3margin The board's action dismissed Widtsoe and Merrill from the ACU. The specific charges against them referred to by Kerr were not read into the minutes, and files containing other information pertinent to the meeting have been lost.

Even if Widtsoe and Merrill disagreed with the expansionist ideas that competed heavily with their views of the agricultural interests of the institution, it is hard to justify the severe action taken against them at this critical point in the ACU's development. Perhaps it may be explained simply by noting that the college was a political football. The pressure from the governor and his appointees and from the legislature and its commission may have created an institutional paranoia that could result in the dismissal of such valued employees.

The offices of the Deseret Farmer were moved from Logan to Salt Lake City following the dismissal of Widtsoe and Merrill. The newspaper had been noticeably silent on the consolidation controversy up to this point, but the continuing investigation of the commission appointed by the legislature made it a statewide issue of interest to readers. Several letters published in the Deseret Farmer suggested that the programs of agriculture would be improved if consolidation occurred. Other letters focused on balance in the overall educational interests of the state and asked for a better distribution of educational monies, "pleading for consolidation on the grounds of the greatest good to the greatest number, and for an extension of the

The Consolidation Controversy 215

26 Ibid., p 157 27 Ibid., p 158

privilege of acquiring at least a high school education by the young men and women of this state."28

Another view published in the Deseret Farmer alleged that Kerr had utilized money appropriated for agriculture for other needs of the college, including tile floors in the president's residence and oak tables in the library. This commentator suggested: "Let the dean of the Agricultural College be responsible for the expenditures and leave the amount to be appropriated with the Legislature as is now done with the Mining School and Utah will have the greatest Agricultural College in the West in avery short time."29

Joseph F.Merrill, director of the School of Mines at the U of U, also wrote a letter favoring consolidation. He pointed out that many strong agricultural colleges operated as departments of universities, as did other special programs, including his own:

We already have two state schools existing as departments of the University—the School of Mines and the Normal School—and so satisfactory is the union that no officer of either school would consent to its separation from the University.30

Both of these schools had achieved distinction quickly on small appropriations compared to independent operations. Merrill asserted that the ACU would enjoy the same benefits through consolidation. Each school controlled itscurriculum, faculty selection, course development, and admission and graduation requirements, and each enjoyed all the freedoms of a separate college. Rather than absorbing and destroying the ACU, consolidation would liberate and strengthen it, he claimed.

For it will put the college at once into the hands of a director and his faculty—all of them specialists in the technical departments. . . . The college will therefore be run and managed by those who are especially trained and interested in the work . . . qualified to determine how the college can best serve the people. Hence the college should, by consolidation with the University, thrive more than it has ever done for the conditions would be more favorable for growth.31

If there was fiscal discrimination against agriculture at the ACU, the independence described byJoseph Merrill would have been most attractive to men like Widtsoe and Lewis Merrill.

29 "A Difference," Deseret Farmer, August 25, 1906, p 5

30 Joseph F Merrill, "Urges Consolidation," Deseret Farmer, September 1, 1906, p 3

31 Ibid., p 3

216 Utah Historical Quarterly

28 Melvin C Merrill, "Another Agricultural College Graduate Favors Consolidation," Deseret Farmer, September 29, 1906, p 12 See also Deseret Farmer, September 22, 1906, pp 13-14

The consolidation controversy continued to polarize those who believed they had a major stake in the outcome Lewis Merrill's editorial response in the Deseret Farmer to a letter printed in the Logan Journal illustrates this. The letter writer had charged that "every great and good cause has its traitor. The Agricultural College cause has its,L.A.Merrill."32 Merrill's editorial argued for loyalty to the institution's best good:

It is a little strange that every one who does not support the President of the Agricultural College isclassed as traitor to the College There isa difference between loyalty to the institution and loyalty to the man who for the time being stands at the head of that institution

As a matter of fact, we do not consider Mr. Kerr disloyal to the State University because he isnow against consolidation, though he isa graduate from a two years course of the University. Neither is any alumnus of the Agricultural College a traitor to that institution if he happens to favor consolidation He may honestly believe that a greater and better Agricultural College may result from such union,—and such being his views, he iscertainlyjustified in working towards his ideals.33

The controversy spread beyond academia and the legislature. Removing the ACU from Logan would affect many people in the community. Local citizens and businessmen joined in the struggle through the Logan Chamber of Commerce. Cache County organizations and related groups from surrounding counties (Weber, Rich, and Box Elder) alsojoined forces.

On March 4, 1907, a bill proposing consolidation of the ACU with the U of U was advanced in the Senate.34 On March 7 it passed by a margin of 12 ayes, 6 nays, 0 absent and not voting—the necessary two-thirds majority for a constitutional amendment. When the bill reached the House of Representatives, however, member^ opposed to consolidation accomplished a near political miracle Although defeated in the Senate vote, Sen Herschel Bullen of Logan continued to lead the legislative fight against consolidation, working hard to form political alliances. When the vote was taken at 11 p.m. on the 57th day of the session, the bill failed to receive the necessary two-thirds majority on a roll call vote: 24 ayes, 20 nays, 0 absent and not voting.35 A group of six senators and twenty representatives had

52 LoganJournal, as quoted in Deseret Farmer, September 8, 1906, p 4

33 Deseret Farmer, September 8, 1906, p 4

34 SenateJournal. Utah, 1907 (Salt Lake City, 1907), p 353

35 Bullen, "The Consolidation Controversy," p 17

217

The Consolidation Controversy

unitedly opposed consolidation during the sixty-day session. Senator Bullen wrote of their determination:

On the morning of each day out of the sixty, when the legislature was in session, and after our group was organized, they met at my room at the Wilson Hotel for roll call and report, or were represented by proxy, or excused If ever a group of men entered into a compact, dedicating every ounce of energy and every spark of ability they possessed, it was this loyal group of defenders.36

Although the fight against consolidation had been won, the legislature and Governor Cutler had in 1905 thwarted Kerr's expansionist policies by limiting the courses that li i i i * ^ T T i r-

john A. Widtsoe.

could be taught at the ACU and refo- USHS collections. cussing the school's efforts on agriculture and industry. Widtsoe and Lewis Merrill had been dismissed for opposing the policies of President Kerr. The legislative sanctions against those policies marked the defeat of the Kerr/McCornick regime and brought about their resignations

On March 21, 1907, the Logan Journal announced McCornick's resignation:

After mature reflection and careful investigation, President W S McCornick of the Board of Trustees . . . reached the conclusion that the seeming intention ofJohn C Cutler and the party behind him, to destroy the Agricultural College, was real, and declining to be a party to such an outrage upon the people of the state, he has tendered his resignation

Mr McCornick was asked not to resign, and what were the terms which he laid down as the price of remaining upon the board, do you think? Simply this—that the administration of William J Kerr should remain undisturbed "If Kerr and his policy are to go, then I'll go too,"was his

218 Utah Historical Quarterly

Ibid.,p 22

ultimatum, and having satisfied himself that the board was packed to carry out a scheme of revenge, he lived up to it.37

One week later Kerr submitted his resignation to the Board of Trustees "to take effect at the end of the school year following the usual plan in such cases."38 He pledged to finish the year's work and prepare the annual report for the board and to cooperate in any desired way. After accepting Kerr's resignation, "on motion of Trustee Smart, Dr.John A. Widtsoe, head of the School of Agriculture of the B Y University at Provo,waselected President of the College to begin at the pleasure of the Board, and end June 30, '08."39 The motion passed, and a new chapter in the history of the ACU thus began. The crisisover consolidation had festered for more than a decade, and itseffect would linger for several more years. Years later Widtsoe expressed some personal feelings about the controversy and his regard for the college.

The dismissal shocked me. It was not so much because of losing ajob; I felt I could get another. But it was unfair, the kind of thing big men don't allow I was subjected to much unfavorable newspaper notoriety inspired by the President or his friends as means of self-defense Most of all, Iwanted to bring toward conclusion the experimental work initiated by me I had so completely identified myself with the work of the Station that I felt as if I were leaving a child It was some comfort to know that the Station and itswork had been brought to national recognition and that Iwas leaving behind a group of men trained in the progressive policy of the Station.40

Widtsoe also revealed hisview of the controversy in a letter to the superintendent of the Ogden city schools:

There are two sides to the question without a doubt I propose, as far as lieswithin my power, to conduct the Agricultural College in such a way as will prevent any ill feeling arising between the University and the Agricultural College, and to prevent any discussion that may tend to injure for a second time, the cause of education in our beloved state.41

The issue of consolidation was past His duty was to set a new course for the ACU in developing industrial education in Utah. The legislature had issued guidelines to minimize the duplication of instruction

17 LoganJournal, March 21, 1907, p 1

38 Minutes of the Board of Trustees, ACU, March 28, 1907, p 226

:;

'' Ibid., p 226

40 John A Widtsoe, In a Sunlit Land (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), pp 86-87

11 Widtsoe to Superintendent John M Mills, August 7, 1912, Papers ofJohn A Widtsoe

The Consolidation Controversy 219

at the two institutions, setting the bounds each was to work within. Widtsoe announced his intention to comply with the new laws governing course offerings. The minutes of the ACU Board of Trustees contain a lengthy report on the courses of study and the direction of the college. According to the law passed in 1905,42 the ACU was not allowed to offer courses in engineering, the liberal arts, pedagogy, law, or medicine; however, only engineering was taught at the college at that time.43 Accordingly, engineering courses were phased out, although students who were pursuing engineering prior to passage of the lawwere allowed to complete their degrees Some doors had closed, but other doors opened. A glimpse of Widtsoe's vision for the school is conveyed in his report to the board. He acknowledged the limits that had been set by the legislature, but he emphasized that there was, nevertheless "a splendid chance for expansion and construction."44

That expansion included the establishment of a traveling school of agriculture and domestic science. To head it and related programs Lewis A Merrill was employed as superintendent of agricultural extension work with headquarters in Salt Lake City. This illustrates the statewide view the ACU has followed since.45 The faculty instituted night schools in domestic science and mechanical arts.Attendance was phenomenal and the students included representative citizens of Logan.46 Widtsoe also advanced programs that imbued harmony between the two schools U of U officials proposed a joint irrigation engineering course, with the university providing all the technical work in engineering and the ACU all the work relating to the duty, use, and measurement of water. Similar ventures were pursued with the State Normal School, exposing its students to agriculture and agriculture students to pedagogy.47

In its first three decades the ACU achieved an international reputation in agriculture Much of this acclaim wasdirectly tied to Widtsoe's influence. Extensive pioneering in arid farming and irrigation,

42 Ricks,

4S Minutes of the Board of Trustees, ACU, April 23, 1907, p 239 This report spans several pages with the lengthiest description under the title of agriculture

44 Ibid., pp 243-44

45 Ibid., June 2, 1908, p 258

46 Ibid., November 30, 1908, p 265

47 Ibid., April 23, 1907, pp 242-43

220 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Utah State Agricultural College, pp 65-66 The law referred to is entitled an "Act prescribing and limiting courses of instruction in the Agricultural College."

combining classroom instruction, laboratory analysis, and experimental farms paid huge institutional dividends. That greatness may never have been achieved had Kerr remained president. On the other hand, the greatness that Utah State University has achieved in fields outside of agriculture may have come earlier had the Kerr administration been allowed to follow its charted course

The institutional development that the leadership of the state rejected seemed to be the very guidance Oregon sought. That isevident in the duration and success of Kerr's service as president of Oregon State University and commissioner of higher education for the state of Oregon. At the same time, the educational vision and practices of Widtsoe became increasingly attractive to the governing boards of Utah's three institutions of higher education. On at least two occasions he was considered for the presidency of Brigham Young University, and for manyyears he oversaw developments there as commissioner of education or as a member of its Board of Trustees Moreover, after nine distinguished years aspresident of the ACU, Widtsoe was asked to take the helm at the U of U He continued in that position until he was called into full-time service as an apostle of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Consolidation was a legitimate public controversy in Utah and across the United States. Ultimately, it may be said that its resolution in Utah was the consummate compromise. The advocates of consolidation of the ACU with the U of U were defeated in 1905 and 1907, and the continuation of the college as a separate entity was assured. The policies of expansionism that had created unnecessary duplication in the eyes of those who favored consolidation were limited by law and by changes in the leadership of the Board of Trustees and the college presidency. Consolidation advocates could thus claimvictory for their ultimate goal.

The Consolidation Controversy 221

"A Little Oasis in the

Desert": Community Building in Hurricane, Utah, 1860-1920

BY W PAUL REEVE

Hurricane Canal control gates. Historic American Engineering Record photograph.

Mr. Reeve is a graduate student in history at Brigham Young University.

BY W PAUL REEVE

Hurricane Canal control gates. Historic American Engineering Record photograph.

Mr. Reeve is a graduate student in history at Brigham Young University.

ON E FEBRUARY NIGHT IN 1910 THE TORRENTIAL Virgin River came thundering down in a tremendous flood, laying waste to everything in its path.JamesJepson,Jr., a resident of Virgin City, Utah, lost his farm to the surging waters. He lamented, "The next morning there wasn't enough land in my main farm to turn awagon around on. But I had another choice bit of land further back, four acres, where I had lucerne and orchard [The river] didn't even leave me that!"1 This was not the first time the Virgin had defied its name and leapt its bounds to destroy farmlands, vegetation, livestock, and the settlers' livelihood Along with their personal property, the river all too frequently washed away the pioneers' determination; many packed what few belongings remained and moved on in pursuit of a more stable environment in which to eke out a living Historians studying "The Stability Ratio" of nineteenth-century Mormon towns found the region of southern Utah the least stable of the four they examined—"fewer than half stayed.2 Although southern Utah experienced a low persistence rate compared to other Utah areas, it scored remarkably high in comparison to the almost 75 percent turnover rate one analyst found among the "non-dependent population" of Jacksonville, Illinois.3

Thus, persistence in Utah's southern region marks a midpoint between the relatively stable areas of central and northern Utah and the extremely fluidJacksonville, Illinois. Even placed within this context, however, the area's persistence rate is not startlingly significant; it isonly through first understanding southern Utah's harsh environment and the circumstances under which the settlers came to colonize it that the stability rates begin to personify the dogged determination of the region's pioneers. In Utah's southwestern desert this determination gave rise to a unique community-building experience—that of Hurricane, Utah.

In 1906 Thomas Hinton became the first colonizer to settle in Hurricane; over the next fourteen years the town experienced a

1 Etta Holdaway Spendlove, "Memories and Experiences of James Jepson, Jr.," p 28, typescript, Utah State Historical Society Library, Salt Lake City

2 Dean L May, Lee L Bean, and Mark H Skolnick, "The Stability Ratio: An Index of Community Cohesiveness in Nineteenth-century Mormon Towns," in Generations and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History, ed Robert M Taylor, Jr., and Ralph J Crandall (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1986), p 155

3 Don Harrison Doyle, The Social Order of a Frontier Community: Jacksonville, Illinois, 1825-70 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), pp 261-62 Doyle's "non-dependent population" included all household heads and family heads, all gainfully employed persons, and all males age twenty or older

Community Building in Hurricane 223

remarkable growth rate that placed its population second only to St. George in Washington County (see Charts 1 and 2) To determine the reasons behind such rapid growth and early community success, this study explores the Hurricane colonizers' backgrounds and places the Hurricane experience within the broader context of the Mormon colonization of the region. The characteristics of the town's early settlers and the community's early leaders and their role in providing stability will also be discussed. In examining these factors it will become evident that Hurricane's early prosperity and growth emerged from the rugged determination of its pioneers; most endured decades of hardship in southern Utah's harsh environment before investing their labor and money in the Hurricane Canal Company in the hope of improving their economic conditions and escaping the violent flood waters of the Virgin River The canal's completion fulfilled the investors' expectations as settlers eagerly poured onto the Hurricane bench and established the town of Hurricane. The new community's rapid growth was largely sustained by an abundance of land and the instant, respected leadership the canal company authorities provided Thus, the canal became the key in Hurricane's community-building success.

For Thomas Burgess the October 1861 conference of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints held far-reaching implications. Active membership in the Mormon church for nineteenthcentury Saints often dictated much of their daily lives, including, at times, prescribing where they would live and thus the hardships they might face. Such was the case with Burgess in 1861 as the "call" came from President Brigham Young to relocate his family to southern Utah to help strengthen the struggling Cotton Mission.

The great colonizing efforts of Brigham Young form an extraordinary chapter in the story of America's western frontier. The Mormons, who arrived in the Great Basin in 1847, had fled the religious persecution that had driven them from Ohio, Missouri, and, finally, Illinois. Eager to live in peace, they willingly committed to settle on undesirable lands, believing that in isolation they could practice their religion and build the kingdom of God on earth free from outside detractors. The Mormons' tragic experience in the Midwest further created a desire among church leaders to establish their godly society based upon the principles of independence and economic self-sufficiency Thus, as southern Utah historian Andrew Karl Larson perceived it, the primary reasons Brigham Young sent a band of

224 Utah Historical Quarterly

Community Building in Hurricane 225

CHART 1: TOTAL POPULATION OF UPPER VIRGIN RIVER TOWNS AND HURRICANE, 1860-1920

CHART 2: TOTAL POPULATION OF HURRICANE AND ST GEORGE, 1870-1920

Source: U.S. Population Census, 1870-1920

1200 1000 800 600 400 200 D Duncan's Retreat • Shunesburg • Grafton H Virgin City 11 Springdale • Rockville H Hurricane 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920

2500 2000 1500 1000 500 D Hurricane M St George 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920

"intrepid settlers" to the rough country of the Virgin River Basin were to "build up the out posts of Zion and to aid the church in achieving the goal of economic self-sufficiency."4 Their mission was to produce enough cotton to supply the church members' needs; with this goal in mind the Mormon prophet directed Burgess and a large group of colonists to relocate in Utah's warm southern climate to establish new settlements and reinforce those already existing.5

The Saints, in their attempt to cultivate the parched lands of the West, quickly discovered that the successful solution to the problem of aridity "was the price of existence." That price, as William E. Smythe described it, was paid by "the free and unlimited coinage of labor," which became the "cardinal doctrine" in Utah's economy. 6 The Saints believed that "all should work for what they were to have, and that all should have what they had worked for." "In order to realize this result," he further explained, "itwas necessary that each family should own as much land as it could use to advantage, and no more. '

These were the principles applied among the southern Utah Saints; yet, in the region's harsh environment the Cotton Mission never really flourished, and as the century wore on the settlers turned more toward eking out an existence for their individual families than to communal cotton production. For residents of the eastern half of the Cotton Mission who were located along the banks of the Virgin River—in particular the communities of Virgin City, Duncan's Retreat, Grafton, Rockville, Springdale, and Shunesburg— even providing for their families proved difficult. For them, accepting the prophet's call included contending with the unpredictable and often violent Virgin River which all too frequently overflowed its banks to claim increasing portions of farmland

These uninviting conditions were all that welcomed the Thomas Burgess family and Burgess's daughter Emma and son-in-law Robert

4 Andrew Karl Larson, "Agricultural Pioneering: Virgin River Basin," Utah Magazine 9 (June 1947): 28 Larson, in a subsequent article, "The Cotton Mission: Settlement of the Virgin River Basin," ibid 9 (August 1947): 6; and in his "Agricultural Pioneering in the Virgin River Basin" (Master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 1946), noted other factors motivating Brigham Young's efforts to settle southern Utah, including "controlling the approaches to the Great Basin where [Young's] empire was centralized," serving as a way station for a "new routing of Mormon immigrants over the old Spanish Trail," providing a link with a "proposed new trade route by way of the Colorado River," converting Indians to Mormonism, and protecting travelers from Indian depredations

' Larson, "Cotton Mission," p 25

6 William E Smythe, The Conquest ofArid America (New York: MacMillan, 1907), p 54

7 Ibid., p 57

226 Utah Historical Quarterly

Warne Reeve to the area about the first of December 1861 This small group camped between the new towns of Duncan and Grafton "until the land was surveyed and drawn." Burgess drew "ablank" and Reeve "two fractions," and so on December 20 they started towards St. George hoping to better their land allotment. When they arrived at Virgin City, however, Reeve's wife delivered her first baby, forcing the group to stop for a few dayswhile the new mother rested During this time they were offered another draw of land and received "only 3 1/2 acres of farm land and a[n] acre city lot."8

Five days later a tremendous rain began to drench the area. The Virgin River and its tributaries all ran high floods that obliterated the first colonizing attempt at Grafton and swept away much of the land at Virgin City and Rockville. For the first settlers of Duncan's Retreat the floods proved too great a challenge; they sold their claims and moved away. Reeve, Burgess, and eight others, looking to improve upon their poor draw of lots in Virgin City, bought the claims in Duncan's Retreat and settled there. The river continued to take its toll in the ensuing years. Reeve described their difficulties: "From time to time heavy floods have come down the river taking our land, orchards and gardens and causing many to leave. At the

Community Building in Hurricane 227

8 Robert Warne Reeve Journal in "Thomas Robert Reeve," ed Fern S Reeve, p 1, manuscript in possession of the author.

present time, 1866, there is not more than one half the bottom land left that was here when we came, but we have been told ... to hold our positions as long as possible."9

Certainly, as Reeve indicated, many could not endure the hardships of the region; and, after thirty years along the river bottom and the complete abandonment of his community, even Reeve moved away. Despite the continual flow of settlers leaving the area, examples of remarkable staying power can be found in some of the communities. In Duncan's Retreat, according to the federal census records, over 80 percent of the families living there in 1870 remained in 1880. The same was not true twenty years later. The community itself was completely abandoned by 1893 due to continued flooding, and less than one-fifth of the town's families found new homes along the upper river basin (see Table l). 1 0 The rest, like Reeve, found land more suitable for farming, no doubt far removed from the destructive forces of the Virgin River. In May 1892 Reeve moved his family to Hinckley in Millard County, Utah, where he described things as "quite different" from the "crowded" conditions in Dixie.11

Even though Robert Reeve decided to seek better conditions elsewhere, his son Thomas stayed and took up residence with his new wife in Virgin City.12 One cannot help but wonder what motivated those who remained in the face of such adverse conditions and, further, what separated those who stayed from those who left. Apart from Duncan's Retreat, the other communities along the Virgin River Basin experienced a comparatively high turnover rate, especially in the first ten years of settlement For example, in Virgin City only one-third of the town's original settlers remained by 1870, and by 1880 only two of the original sixteen families persisted amid

9 Ibid., p 3

10 U.S Manuscript Census, Washington County, Utah, 1860-1900; Kane County, Utah, 1870 All census references are from Washington County, Utah, except 1870 when boundary changes included the upriver communities in Kane County

" Reeve, "Thomas Robert Reeve," p 4

12 If at least one family member was traceable through the census records, then that family was counted as persisting Hence, in the case of the Reeves, even though Robert Warne Reeve moved away in 1891 and thus did not appear on the 1900 census, his son Thomas Robert Reeve was listed as a resident of Virgin City in 1900, and therefore the family was included among the persisters The problem inherent with this methodology is the difficulty of tracing daughters who might have married during the decade between census counts; however, among the families studied there were only a few whose children were all girls This, of course, excludes young couples with only one child who would not have been of marriageable age by the next census Overall, there is a minimal likelihood of these numbers being skewed by families with daughters who may have married and remained in the area but were untraceable The other difficulty in this type of study is compensating for those who may have died between census records; yet, by calculating persistence based upon traceable family members this problem should also be minimal

228 Utah Historical Quarterly

Source: U.S Manuscript Census, 1860-1900

^Includes any male member of the family traceable through census records See note 12 for a further explanation of methodology

the hardships of the region In Rockville the results are similar for the first decade, with slightly over one-third of the town's pioneers enduring; and twenty years later less than half of those remained. The numbers vary from community to community, but the general pattern seems to indicate that those who arrived after the initial settlement period were more likely to persist, excluding Duncan's Retreat and Shunesburg which were abandoned by 1900 It is plausible that because many of the difficult tasks of colonization, such as building roads, irrigation ditches, and community structures, had already been accomplished, new settlers could integrate more easily into an established social order. Even with these advantages, the turnover rate was still around 50 percent among the later arrivals, the low being 33 percent persistence in Rockville and the high 67 percent in Grafton (see Table 1). In the end, the results for the four communities still existing in 1900 are remarkably similar; close to half of the total families in the region had at least one family member who had persisted for twenty years or more along the upper Virgin River Basin (see Table 2).13

13 U.S Manuscript Census, 1860-1900

Community Building in Hurricane 229

Year Virgin City 1860 1870 1880 Grafton 1870 1880 Rockville 1870 1880 Shunesburg 1870 1880 Duncan's Ret. 1870 1880 Springdale 1880 Total Families 16 36 36 7 9 37 42 7 15 11 13 9 Persisted Through 1870 5 (31%) Persisted Through 1880 2 (13%) 19 (53%) 5 (71%) 14 (38%) 4 (57%) 9 (82%) Persisted Through 1900 2 (13%) 9 (25%) 17 (47%) 4 (57%) 6 (67%) 5 (14%) 14 (33%) 3 (43%) 4 (27%) 2 (18%) 2 (15%) 5 (55%)

TABLE 1: FAMILIES* ALONG THE UPPER VIRGIN RIVER WITH AT LEAST ONE MEMBER PERSISTING, 1860-1900.

TABLE 2: FAMILIES IN 1900 WH O PERSISTED FOR TWENTY YEARS OR MORE ALONG THE UPPER VIRGIN RLVER GORGE

In explaining the distinction between those whostayed and those who left, a natural assumption isthat the persisters enjoyed a financial security that perhaps mitigated the otherwise harsh conditions. As a whole, however, neither group commanded great wealth In comparing the persisters' real estate and personal estate values listed in the 1860 and 1870census against that ofthemovers, thedifference in economic conditions between the two groups only partially explains why some stayed and others left. For example, the 1860median real estate value for the persisters was 67 percent higher than for the movers; however, the median personal estate valueswere identical at$300.The results varied in 1870when the difference in real estate value fell to a 33 percent margin in favor of those who stayed while the persisters' personal estate value jumped to 75 percent higher than those who left.14 In general then, those whostayed appeared toenjoy abetter economic condition than those who left, which maypartially account for the latter groups' movement Yet,it isalso interesting to note that the largest landholder in 1870,Ansom Winsor at$3,000,wasamong those who had moved by 1880.Therefore, taken asawhole, an economic interpretation fails toprovide acompletely satisfactory explanation.15

14 Ibid For persisters in 1860 the median real estate value was $250, compared to $150 for nonpersisters The average real estate value was $250, with a low of $100 and a high of $440; for nonpersisters the real estate average was $309, with a low of $75 and a high of $1,200 In 1870 the median real estate value for persisters was $300 versus $225 for nonpersisters In personal estate the median was $350 for those who stayed and $200 for those who left In the same year the average real estate for persisters was $483 with a low of $0 and a high of $1,500; for nonpersisters the low was also $0, the high was $3,000 and the average was $387

15 Neither age nor occupation was significant in explaining the difference between the two groups In general, the male heads of household in both groups were around 42 years old and the majority were farmers In 1860 the actual statistics for persisters were: average age, 35; median age, 36; youngest, 26; oldest, 45; occupation: farmer, 60%; farm laborer, 20%; and other, 20%; for the same year among nonpersisters: average age, 42; median age, 40; youngest, 23; and oldest, 64; occupation: farmer, 100% In 1870 the persisters' statistics were: average age, 45; median age, 47; youngest, 22; oldest, 79; occupation: farmer, 64%; farm laborer, 13%; and other, 23%; the figures for nonpersisters in 1870 follow: average age, 43; median age, 42; youngest, 21; oldest, 85; occupation: farmer, 61%; farm laborer, 19%; and other, 19%

230 Utah Historical Quarterly

Community Virgin City Grafton Rockville Springdale Shunesburg Duncan's Retreat Total Families in 1900 34 11 23 17 0 0 Number of Persisters 19 6 14 7 Percent of Persisters 56% 54% 61% 41%

Perhaps the answer resides in the individual character traits of those who were called upon to endure the hardships of the Virgin River Basin Robert Reeve gave one indication of his staying power when he wrote, "butwe have been told from time to time to hold our positions as long as possible."16 His statement implies a devotion and submission to church authority asa reason for remaining despite the adverse conditions. As sociologist Lowry Nelson discovered through in-depth examinations of several Mormon settlements, religion played a key role in establishing a social order in the Mormon West Most Latter-day Saints,with their reverence for church authority and belief that Brigham Young was divinely inspired, would make personal sacrifices to accept the call to colonize; this was certainly the case for those settling along the Virgin River Basin.17

In addition to this religious zeal, the Saints possessed a unique mindset concerning marginal lands As previously described, they were willing to accept the hardships of the semiarid West in exchange for isolation and religious freedom. Thus, they saints were often officially instructed, even from the pulpit, to colonize unattractive areas. A discourse by Apostle George Q. Cannon on August 10, 1873, in the Salt Lake Tabernacle provides a notable example. He told the Saints, "good countries are not for us" but "the worst places in the land we can probably get and we must develop them." If the Saints took the "good country" it would not be long "before the wicked would want it," he warned. They should instead "thank God" for what they have even if it is "a little oasis in the desert where a few can settle."18 Considering that a fundamental tenet of Mormonism is the belief that the words of the prophet or an apostle are inspired messages from God, this sermon becomes all the more powerful. In essence then, the Saints were consigned to their difficult circumstances by their devotion to a church hierarchy they believed to be divinely inspired.

In southern Utah local authorities promulgated similar messages. At a church conference in St. George during May 4-6, 1866, H. W. Miller compared his farming experiences in the East with that

16 Reeve, "Thomas Robert Reeve," p 3

17 Lowry Nelson, The Mormon Village: A Pattern and Technique of Land Settlement (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1952) For specific examples of devotion among those called to the Cotton Mission see Andrew Karl Larson, "I Was Called to Dixie"; The Virgin River Basin: Unique Fxperiences in Mormon Pioneering (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1961), chap 8

18 Journal ojDiscourses, 26 vols (Liverpool, 1854-86), 16:143-44 Cannon was specifically addressing a failed Arizona colonizing attempt; however, his words reflect church teachings for all regions

Community Building in Hurricane 231

in northern and southern Utah and concluded "to his entire satisfaction that a small piece of land well cultivated was more lucrative in yielding comfort and wealth than a very large piece with common cultivation."19 The Saints were often encouraged and directed concerning their utilization of these "small piece[s] of land." On one occasion the presiding authority for the area, Erastus Snow, toured the upriver settlements and delivered his counsel. The report of his visit states, "the brethren were encouraged to plant cotton more extensively, and although the season is far advanced were advised to plant all they can within the next few days, as the crop of cotton will otherwise be light this season, and the mills will be idle."20 Snow also played down the recent floods the settlers had experienced: "We found the saints in . . . cheerful spirits. The high waters of the Rio Virgin have done less damage than was at first reported. The prospect for fruit this season is very flattering: orchards are laden with everyvariety of the climate."21

If the reports in the Desert News are any indication, Snow was correct about the cheerful attitudes, at least until the next floods hit. A.J. Workman, one of the original settlers of Virgin City, expressed to the church newspaper his perfect contentment with conditions: "I have quite a family, about a dozen in all, and by the help of the Lord I live and have plenty, and raise it from four or five acres; and I believe I could live well and support my family on three acres. We do not know what we can do until we try."22 With such a positive outlook and religious devotion, it isno wonder Workman was one of only two Virgin City original settlers to persist along the basin for over forty years.

Thus, the religious devotion of these faithful Mormons, coupled with a mindset programmed to accept less than desirable lands and further enhanced by particularly positive dispositions, largely accounts for the persistence of these rugged individuals in the face of devastating circumstances. Generally speaking, however, this devotion and determination appeared in at least three distinguishable levels and led to different responses from the settlers. The first level, demonstrated by Workman's optimistic attitude and religious piety,

19 Deseret News, 15:197.

20 Ibid., 16:201

21 Ibid.

22

15:189, and 16:49

232 Utah Historical Quarterly

Ibid., 16:246 Workman submitted equally glowing reports on other occasions See Desert News, 15:29,

likely characterized those who persisted The next group, while still demonstrating their reverence for church authority, perhaps lacked Workman's sanguine outlook or his sturdy fortitude to remain in the region despite its unfavorable environment. For example, many colonizers revealed their continued devotion to the Mormon hierarchy by seeking releases from church authorities prior to leaving Charles Burke, like so many others, had been called to the Cotton Mission and had settled in Virgin City.As the floods continued to destroy his means of existence he opted for brighter prospects elsewhere. His daughter wrote, "When father decided to move to Hin[c]kley he went to St George and asked the Stake President for a release from his Dixie Cotton Mission call. They gave it to him with their blessings."23 Joseph Black, a Rockville resident, was also discouraged by the hardships of the Cotton Mission. After determining he could not make a proper living for his family, he wrote to Brigham Young describing his valiance in settling the region but regretting that due to the growing size of his household and the difficult conditions along the river basin he could no longer subsist in Rockville Young gave permission to Black to move to Millard County and buy a wheat farm.24

A final group of colonizers lacked both devotion to authority and dogged determination. Among these Saints, releases were not obtained prior to leaving; in particular, following yet another devastating rampage by the Virgin River in 1868, a number of families simply deserted. They were not highly regarded for abandoning their posts, and when the local hierarchy went into the area to boost morale and reinforce the Saints' religious conviction, the report described the residents of Virgin City, Duncan's Retreat, and Rockville as "alittle cast down over the loss of their farms" and then noted that many of them had "stampeded last winter" without first obtaining a release. Those who remained were admonished to follow "the Savior's parable: that the wise man built his house on a rock, and when the winds blew and the floods came, that house stood!"25

It seems apparent that the Virgin River, in effect, served as a winnowing agent. It separated those with rugged determination, religious zeal, and a mindset accepting of difficult conditions from

25 Deseret News, 17:135

Community Building in Hurricane 233

23 Carrie Burke Wright, "Memories" in "Mary Jane Burke Reeve," ed., Fern Reeve, p 3, copy in possession of the author

24 Hazel Bradshaw, ed., Under Dixie Sun (Panguitch, Ut.: Garfield County News, 1950), p 283

CHART 3: ORIGINATING TOWNS OF 1910 HURRICANE, UTAH HOUSEHOLDERS

Source: U.S Manuscript Census, 1900-1910

CHART 4: ORIGINATING TOWNS OF 1910 HURRICANE, UTAH HOUSEHOLDERS WH O MOVED FROM THE UPPER VIRGIN RIVER BASIN

Source: U.S. Manuscript Census, 1900-1910.

those lacking one or more of these characteristics. Indeed, by 1900 the Mormon community-building experience along the upper Virgin River Basin had produced a determined group of individuals with extraordinary staying power. Therefore, when a proposal was advanced and accepted in 1893 to construct a canal nearly seven miles long to bring water to the thirsty land known as the Hurricane Bench, families scraped together what little money they had and

234 Utah Historical Quarterly

All Else 29 %

Upper Virgin River Town s 71 %

City

Rockville 17% Springdale 2% Grafton 17% Virgin

64%

joined together to incorporate and take stock in the Hurricane Canal Company. They were investing in their hopes for an improved future; and even though two previous surveys had deemed the canal impossible to build, the hardships these colonizers had already endured had molded them into a perfect group to accept this difficult challenge

On August 6, 1904, following eleven years of tedious manual labor, the first water flowed through the Hurricane Canal onto the desert soil of the Hurricane Bench However, there were still many miles of distribution ditches to dig before widespread agriculture and settlement could begin In fact, not until 1906 did Thomas M Hinton, the first resident of Hurricane, arrive. Interestingly, he was not one of the builders of the canal. Although born in Virgin, he had moved away prior to the canal's construction. Unlike Hinton, over two-thirds of the fifty-eight households found in Hurricane by 1910 had moved there from farmlands along the upper Virgin River (see Chart 3). Of those, 64 percent had originated, likeJames Jepson, in Virgin City.The remaining 36percent had migrated from the other river communities of Rockville, Grafton, and Springdale (see Chart 4).26 The significance of these figures lies in the fact that of those families moving from the basin to settle Hurricane, over ninetenths had persisted along the river bottom for at least twenty years. 27 These findings, coupled with the fact that nearly three-quarters of the canal company stock-holders by 1907 were persisters of over thirty years, demonstrate the durability of those who were among Hurricane's original settlers (see Table 3).28 Such a legacy of perseverance virtually ensured the new community's success.

For Thomas Hinton, it seems that Hurricane provided the economic opportunity he needed to raise his family. According to Vera, his oldest daughter, the family had been extremely mobile prior to their arrival in Hurricane. She recalled that from 1900 to 1906 they had moved five times before making Hurricane their home.29 Using

b U.S Census, 1900 and 1910 Specifically, 17% were from Rockville, 17% from Grafton, and 2% from Springdale

'" Almost two-thirds persisted for thirty years or more

"H Records of the Hurricane Canal Company, Hurricane Canal Company Office, Hurricane, Utah These numbers were obtained by comparing the stockholders listed in company records with federal census records Most of Hurricane's original settlers held stock, at least from 1902; the latest year one of them purchased their first stock was 1907

'"'Vera Hinton Eagar, "The Life of Vera Hinton Eagar," photocopy of holograph in possession of the author

Community Building in Hurricane 235

his skills as a carpenter, Hinton built a lumber granary for Thomas Isom which he wasthen allowed to use as a place of residence until he could construct a more suitable dwelling.30 By 1910 Hinton owned his own home free of mortgage and undoubtedly kept busy constructing houses and barns for the newly arriving residents.31 Hinton was thirty-three in 1910; he had been married for eleven years and had three daughters. Hewasfairly typical of the town's sixteen new arrivals who originated from outside Washington County and accounted for one-fourth of the Hurricane's families in 1910.It seems certain that all but one, Edward Cuffs, moved to Hurricane from within Utah. Even his move wasnot from a great distance. His three youngest children were born in Nevada, and he likely moved to Hurricane from that state.32 The average age of a head of household among the newcomers wasthirty-six—a full eight years younger than the average for the persisters. The oldest among the newcomers was Joseph Retty, a sixty-one-year-old widowed farmer, and the youngest wasJoseph Spendlove, a twenty-five-year-old farmer and father of six-month-old twins.33

By occupation, exactly half of the town's carpenters and almost three-fourths of its day laborers were newcomers. In contrast, only one-fifth of the town's farmers had moved from outside the county;

30 Larson, "I Was Called to Dixie, "p 400

31 U.S Manuscript Census 1910 Hinton listed zero months unemployed on the census record

32 In fact, if Cuff, as seems likely, moved from a location in southern Nevada such as Mesquite or Panaca he would have been closer than someone leaving central or northern Utah