XS1 I— O 50 < O d S M 05 b5 s 25 CI S w H

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

KENNETH L. CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1995 JANICE P. DAWSON, Layton, 1996 AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1994 JOEL C. JANETSKI, Provo, 1994 ROBERT S. MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1995 ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996 RICHARD W SADLER, Ogden, 1994

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden, 1995 GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 x/\ or 3 V2 inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society.

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

THE COVER Many pieces of horse-drawn equipment can still be seenat the Swett Ranch inDaggett County, including this intact Hoover-type hay wagon. The ranch, listed in the National Register of HistoricPlaces, has been owned and maintained bythe U.S.Forest Service since 1972. Hundreds of other artifacts as wellas the ranch buildings help visitors to the site discover what homestead life was like. Forest Service photograph in USHS National Register files.

© Copyright 1994 Utah State Historical Society

mm Hi Jt

HISTORICA L GLTJARXERL Y Contents SPRING 1994 / VOLUME 62 / NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 103 THE 1872 DIARYAND PLANT COLLECTIONS OF ELLEN POWELL THOMPSON BEATRICE SCHEER SMITH 104 THE SWETT HOMESTEAD, 1909-70 ERIC G. SWEDIN 132 GARLAND HURT, THE AMERICAN FRIEND OF THE UTAHS DAVID L BIGLER 149 OVER THE RIM TO RED ROCK COUNTRY: THE PARLEYP PRATT EXPLORING COMPANYOF 1849 DONNA T SMART 171 BOOKREVIEWS 191 BOOKNOTICES 199

VJtX

SANDRA C. TAYLOR Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment atTopaz SACHI W. SEKO 191 192

MARK ANGUS Salt LakeCityUnderfoot: Self-guidedToursof Historic Neighborhoods ROGER ROPER

R MCGREGGOR CAWLEY Federal Land, Western Anger: The Sagebrush RebellionandEnvironmental Politics JAMES MUHN 193

STEPHEN TRIMBLE. The People: Indiansof the American Southwest FLOYD A. O'NEIL 195

JACQUELINE PETERSON with LAURA PEERS. Father DeSmet andthe Indians of the RockyMountain West JEROME STOFFEL 195

RICHARD E TURLEY, JR Victims: The LDSChurch andthe Mark HofmannCase MAXJ. EVANS 196

GENE A. SESSIONS and CRAIG J. OBERG., eds. The Search forHarmony: Essays on Science and Mormonism... .MICHAEL P. DONOVAN 198

Books reviewed

In this issue

Historians of the Powell expeditions have traditionally focused on the geological, geographical, and ethnological contributions of those well-documented explorations and in the process have spared little ink in describing the grit and egotism of the major and his men. The student envisions masculine images of boats, bruises, rapids, tempers, and sweat. Now, with the discovery of Ellen Powell Thompson's diary in the New York Public Library, generously excerpted in our first article, a much more complete picture emerges of the second expedition. The genteel Ellen, like her brother a keen and indefatigable observer of the Colorado Plateau, concentrated on floral specimens. Her careful documentation significantly expanded the collective botanical knowledge of that time and place, while her diary reveals much about herself, the expedition, and the red rock country of 1872.

Not far from the spot that Powell first launched his boats in the Green River, we shift to a later time and an engaging story of bucolic family life on a remote but picturesque homestead. Now gone, and their homestead incorporated as a visitor site within a national recreation area, the Swett family left a nostalgic record of life on Utah's agricultural fringe that served them well clear through the 1960s.

Our attention then shifts back to the nineteenth century and heroic achievement for the final two articles. One examines the philosophy and courage of Indian agent Garland Hurt and his tumultuous tenure in Utah Territory in the 1850s The other chronicles the incredible saga of the Parley P Pratt exploring party through southern Utah in 1849 Full of action and suspense, both are meant to be read and appreciated from the comfort and security of the living room on a pleasant summer evening

Buildings on Green Section of Swett Ranch. Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service.

The 1872 Diary and Plant Collections of Ellen Powell Thompson

BY BEATRICE SCHEER SMITH

Ellen Powell Thompson (1840-1909), 1870. Courtesy of Grand Canyon National Park, Museum file #8183.

Dr Smith, a resident of St Paul, Minnesota, holds three degrees in botany and is the author of A Painted Herbarium: TheLife and Art ofEmily Hitchcock Terry (1838-1921) (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1992)

BY BEATRICE SCHEER SMITH

Ellen Powell Thompson (1840-1909), 1870. Courtesy of Grand Canyon National Park, Museum file #8183.

Dr Smith, a resident of St Paul, Minnesota, holds three degrees in botany and is the author of A Painted Herbarium: TheLife and Art ofEmily Hitchcock Terry (1838-1921) (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1992)

"I never felt more exultant in my life ... I was looking on the most wonderful scenery I ever beheld."

"Drew a large cactus growing by the pool. Got heated. Went to bed sick."

"I feel used up. More so than I ever felt in my life."

So WROTE ELLEN POWELL THOMPSON, SISTER OF Major John Wesley Powell, in the small diary she kept briefly in 1872 as she accompanied her husband, Professor Almon Harris Thompson, through the canyon country of southern Utah and northern Arizona when he was geographer and first assistant to Powell on his second exploratory expedition of the Colorado River in 1871-72. The progress and accomplishments of this expedition are well documented: almost all members of the party keptjournals, which have been published, and some wrote articles for their hometown newspapers. 1 Now with this account of Ellen Thompson's diary, housed in the New York Public Library and heretofore unpublished, and recognition of her interest in the flora of the Southwest, a different voice is added to these records. "Nell," or "Nellie," as she was called, not only survived the rigors of the trip, which in itself is notable, but she collected plants along the way. She was among the early plant collectors of the area, and her specimens, including several species not described before, are preserved in the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University

As far aswe can determine from the fragmentary remains of the first pages of Ellen Thompson's diary, she did not begin recording her canyon experiences until several months after the Colorado River expedition was underway She was, however, with the group from the start. The members' first general rendezvous was scheduled for about May 1, 1871, in Green River City, Wyoming, a plan they carried out successfully. Nell was not the only woman in the party: Emma Dean Powell, wife of the Major (asJohn Wesley Powell was called), was also along. About ten of the expedition members had come by train from St. Louis via Omaha, Cheyenne, and Laramie, arriving at Green River Station the morning of April 29. The party made camp in some deserted adobe huts. Clem (Walter Clement) Powell, the Major's

1 Transcripts of the diaries, journals, and letters of members of the second Powell Colorado expedition and their biographies can be found in the Utah Historical Quarterly, volumes 7 (1939), 15 (1947), 16 (1948), and 17 (1949) Darrah (William Culp Darrah, Powell of the Colorado [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1951], p 162) considers the following journals and diaries of particular interest and lists them in what he considers their order of value: A. H. Thompson, J. W. Powell, S. V. Jones, W Clement Powell, F M Bishop, and J F Steward

Ellen Powell Thompson105

twenty-year-old cousin who had been hired as a boatman, wrote in his diary (April 30): "The river, railroad and our camp are in the Green River Valley surrounded by high bluffs. It is a picturesque place." The women stayed briefly with the party in Green River, helping to prepare the supplies for the descent of the river. Nell had sewn American flags for each of the three boats. On May 3, escorted by their husbands, they left for Salt Lake City, where they planned to spend the summer Clem noted on that day: "Cousins Emma and Nellie left for Salt Lake City.Will not see them again till next winter."2

Meanwhile, at Green River City preparations continued. The Major and Professor (as Thompson was known) had returned from Salt Lake City, the personnel of the river party was complete, and

106Utah Historical Quarterly

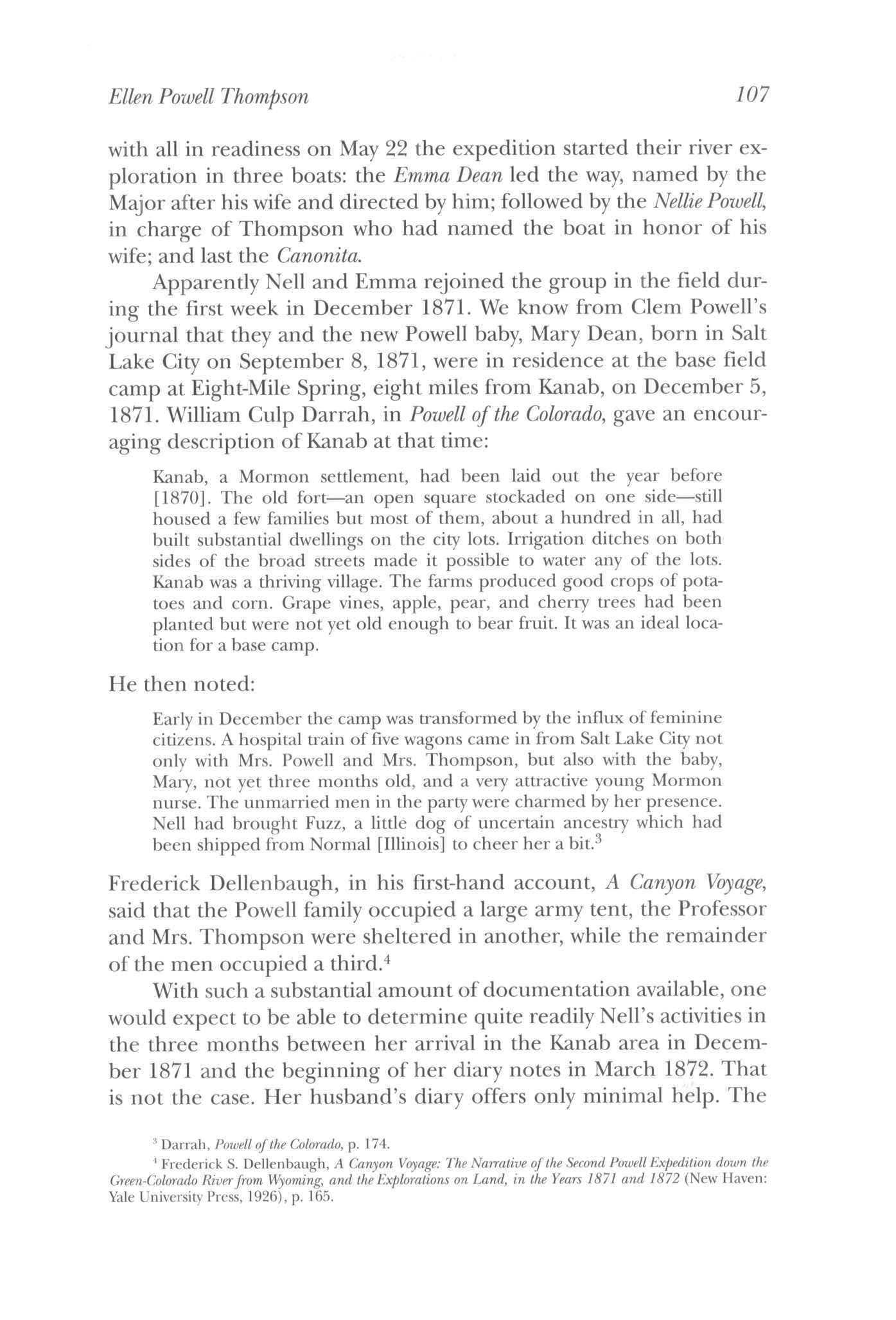

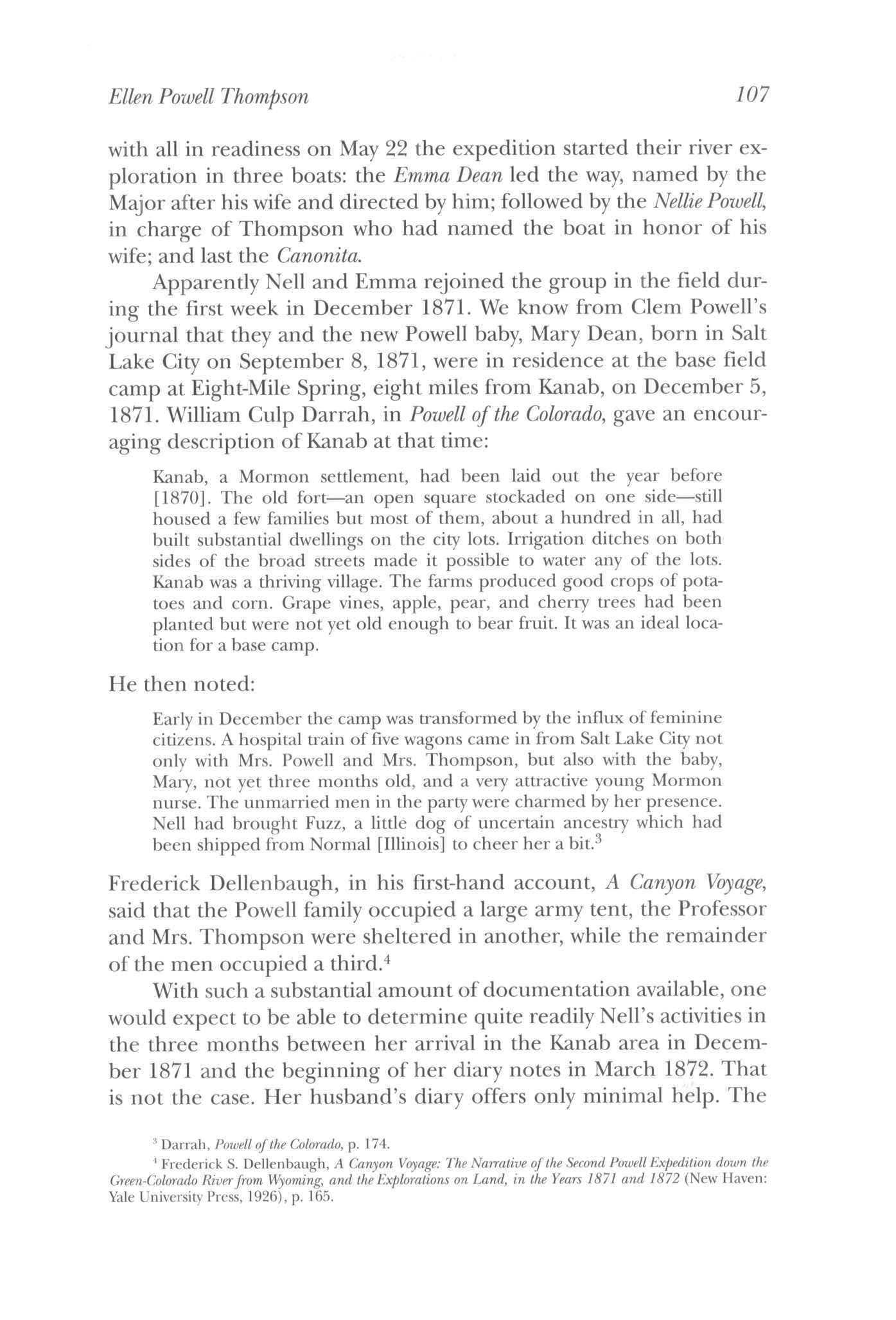

Powell family siblings gathered in Topeka, Kansas, for thefuneral of sister Martha Powell Davis, November 10, 1900. Seated: Major John Wesley Powell, Mary Powell Wheeler; standing: Ellen Powell Thompson, Bramwell Powell, William Paul Powell (son of Bramwell), Almon Harris Thompson (husband of Ellen). From the William Gulp Darrah Collection, courtesy of Elsie Darrah Morey.

2 Charles Kelly, ed., 'Journal of W C Powell—April 21, 1871-December 7, 1872," Utah Historical Quarterly 17 (1949): 259

Ellen Powell Thompson101

with all in readiness on May 22 the expedition started their river exploration in three boats: the EmmaDean led the way, named by the Major after his wife and directed by him; followed by the Nellie Powell, in charge of Thompson who had named the boat in honor of his wife; and last the Canonita.

Apparently Nell and Emma rejoined the group in the field during the first week in December 1871. We know from Clem Powell's journal that they and the new Powell baby, Mary Dean, born in Salt Lake City on September 8, 1871,were in residence at the base field camp at Eight-Mile Spring, eight miles from ICanab, on December 5, 1871. William Culp Darrah, in Powell of the Colorado, gave an encouraging description of Kanab at that time:

Kanab, a Mormon settlement, had been laid out the year before [1870]. The old fort—an open square stockaded on one side—still housed a few families but most of them, about a hundred in all, had built substantial dwellings on the city lots Irrigation ditches on both sides of the broad streets made it possible to water any of the lots Kanab was a thriving village. The farms produced good crops of potatoes and corn. Grape vines, apple, pear, and cherry trees had been planted but were not yet old enough to bear fruit It was an ideal location for a base camp

He then noted:

Early in December the camp was transformed by the influx of feminine citizens. A hospital train of five wagons came in from Salt Lake City not only with Mrs. Powell and Mrs. Thompson, but also with the baby, Maiy, not yet three months old, and a very attractive young Mormon nurse The unmarried men in the party were charmed by her presence Nell had brought Fuzz, a little dog of uncertain ancestry which had been shipped from Normal [Illinois] to cheer her a bit.3

Frederick Dellenbaugh, in his first-hand account, ACanyonVoyage, said that the Powell family occupied a large army tent, the Professor and Mrs. Thompson were sheltered in another, while the remainder of the men occupied a third.4

With such a substantial amount of documentation available, one would expect to be able to determine quite readily Nell's activities in the three months between her arrival in the Kanab area in December 1871 and the beginning of her diary notes in March 1872 That is not the case. Her husband's diary offers only minimal help. The

3 Darrah, Poiuell of the Colorado, p 174

4 Frederick S Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage: The Narrative of the Second Powell Fxpedition down the Green-Colorado Riverfrom Wyoming, and the Fxplorations on Land, in the Years 1871 and 1872 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1926), p 165

4 Frederick S Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage: The Narrative of the Second Powell Fxpedition down the Green-Colorado Riverfrom Wyoming, and the Fxplorations on Land, in the Years 1871 and 1872 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1926), p 165

period in question coincides precisely with a time of concentrated effort on Thompson's part to produce a topographic map of the area, his primary responsibility His customary brief daily comments unfortunately are limited even more than usual to succinct scientific observations. As Herbert E. Gregory, geologist and editor of the Almon Thompson diaries, explained:

Beginning with December 7 and extending to May 25, 1872, Thompson and assistants gave their attention to the preparation of a topographic map The brief entries in the Diary for this period note chiefly the routine relating to personnel, equipment, methods of procedure, and areas surveyed The pleasures, hardships, disappointments, and dangers of work in an unexplored country are minimized as features incident to all new scientific exploratory work.5

This single-minded point of view left little room for personal details Clem Powell recorded in his journal that Christmas and the New Year were celebrated in the Kanab base camp, and during the first two weeks in January he referred frequently to his visits to the Thompsons' tent and to his outings with the Professor and Cousin Nellie into Kanab On February 4 he wrote: "Prof, intends breaking up camp and go on a trip to the Buckskin, Cousin Nellie and all of us"; and on February 23, "Started for the Buckskin Range [Kaibab Plateau]."6 From these few records of Ellen Thompson's activities during the winter months of 1872 we turn to her diary, beginning with the first full day's record on Tuesday, March 5.

THE DIARY

The New York Public Library card that identifies Ellen Powell Thompson's diary reads: "Thompson, Mrs A H., Diary, 1872-1873?, kept by Mrs. A. H. Thompson, while on a trip to the Colorado River with her husband. 132 p."7 It is housed in a green buckram manuscript box with her husband's diary for 1875.According to the labels affixed to the item, Nell's diary was presented to the library by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh on April 30, 1919; he had received it from her on November 3, 1908. Dellenbaugh, a lad of only seventeen

6 Kelly, 'Journal of W C Powell," pp 395, 397

7 Permission to publish the Ellen Thompson diary has been granted by the Rare Books and Manuscripts Division of the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations, which the author gratefully acknowledges.

108Utah Historical Quarterly

s Herbert E Gregory, ed., "Diary of Almon Harris Thompson: Geographer, Explorations of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries, 1871-1875," UtahHistoricalQuarterly 7 (1939): 63

Ellen Powell Thompson109

years when he was hired as a boatman on the second Colorado River expedition, has written engagingly of his experiences.8

Ellen Thompson wrote her diary notes in pencil on a small unlined pad, 3 1/4 by 5 1/4 inches. The once-joined pages are now separate and darkened with age. The notes, written across the narrow dimension of the page, are sometimes too faint to read, and the words are often difficult and even impossible to decipher. The first 24 pages of the total 132 exist only as fragments. Among the remnants, the earliest decipherable date is February 19 [1872]. But beginning at the twenty-first page a continuous record can be followed from Tuesday March 5 through Thursday May 16 [1872]. After a blank page or two, and a lapse of a year, Nell resumed her writing in the spring of 1873 (erroneously labeled 1872), but made only brief notes for less than two weeks (April 5 to April 16). The remainder of the notebook, some twenty pages, is blank except for a few lines of notes not related to her canyon experiences.

For the sake of clarity, in the following diary transcriptions misspellings have been corrected and punctuation has been added By consulting the journals of other members of the expedition, Ellen Thompson's meanings and her location, if unclear, could generally be determined. Most useful were Professor Thompson's diary and Dellenbaugh's account in ACanyonVoyage.9 The general area covered by the survey during the winter and spring of 1871-72, when Nell accompanied the party in the field, included the Kaibab and Kanab plateaus, the region between the Paria and Virgin rivers, the Mount Trumbull district, and areas west to the Nevada line. People referred to are: "Harry," "Prof.," Almon Harris Thompson, Nell's husband, geographer, and Powell's chief assistant; 'Jones," Stephen Vandiver Jones, topographer; "Fred," Frederick Samuel Dellenbaugh, artist and assistant topographer, at seventeen the youngest member of the group; 'Johnson," "Willie," William Derby Johnson, Jr., topographer; "Cap," Captain Pardyn Dodds; "Clem," Walter Clement Powell, Major Powell's first cousin, boatman, and assistant photographer; 'Jack," or "Hillers," John K. Hillers, boatman and photographer; "Andy," Andrew J. Hattan, cook and boatman; and James Fennemore, photographer. Any material added to the original document is enclosed in brackets.

8 Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage.

9 Gregory, "Diary of Almon Harris Thompson," pp. 70-77; Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p. 184-94

8 Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage.

9 Gregory, "Diary of Almon Harris Thompson," pp. 70-77; Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p. 184-94

Tuesday, March 5, 1872, found the members of the survey field party, with Nell in attendance, on the Kaibab Plateau. The Professor recorded cliffs 1,400 feet high at the lower end of the canyon (tributary to Snake Gulch) in which they were camped The Moqui (Hopi) Indian ruins Nell mentions were apparently seen by the Powell expedition on the first exploration of the Colorado two years earlier, and Harry,Jones, and Nell went to see if they could locate them again.10

10 A photograph (no 136, without title) in the Hillers Collection of Photographs of the Powell Survey in the National Archives, Washington, D C , shows a cliff dwelling (?) with an American woman in the center of the picture. This is very likely the site Nell described. The finding guide to the collection suggests that the figure may be Mrs J W Powell or Mrs A H Thompson Unfortunately, the quality of the photograph did not allow clear reproduction It should be added that Mrs Powell did not accompany the 1872 field expeditions

110Utah Historical Quarterly

Map of southwestern Utah and northwestern Arizona showing the region where Ellen Powell Thompson botanized as she traveled with thefieldparty of the second Powell exploratory expedition of the Colorado River in 1871-72. Drawn by natural history illustrator Kristine A. Kirkeby to whom the author expresses gratitude.

Tuesday [March] 5th

Broke camp at [ ] and started for the first camp we made in this canon. As four of the horses could not be found we cannot go for the Kanab Wash. Got here at 12 o'clock. After dinner Harry, Jones, and self went to find old Moquis ruins in a side canon Found old walls of their houses under the ledge of rocks on the side of the walls on one side, two years since The Mormons thinking they might find some treasure hidden dug in the earth and tore down much of the wall But instead of tearing down anything that the Indians ever built they tore down a wall Nature made Ajoke on them!! Found a spring [Oak Spring, on a tributary to Snake Gulch] They are very rare in these canons Got into camp at 8 o'clock The men had found the horses It looks like a storm

The following day Nell recorded finding a new species of cactus (which the Professor notes in his dairy as well). Nell had a strong interest in the botany of the region Unfortunately her notes about her plant collections are only sketchy. Although meager, they are most welcome, since mention of plants is almost nonexistent in other accounts. What information can be gathered is discussed in a later section

Wednesday [March] 6th

Started at 9 for the "Kanab Wash [Kanab Creek]." Out of this Canon [Snake Gulch] into another to the West In a snow storm In half an hour it cleared off aswe supposed And for two hours I never felt more exultant in my life The sun shone so bright—and yet it was cool The air so pure, and I was looking on the most wonderful scenery I ever beheld Avery narrow canon about one-eighth of a mile in width with its walls on either side rising from 800 to 2000 feet At first for the first 5 miles the right hand wall layin waves of willows and was covered with small cedars The left hand rising in cliffs Then both walls were massive cliffs almost reaching to the sky of white sandstone, now seldom trees to be seen Harry, Fred, and I went on ahead of the others to sketch the hieroglyphics Now the walls on either side rise to 1500 feet It clouds up, and we are in a heavy snow storm for four hours, tho we stop several times to sketch. Found a new cactus (to us). Intend to secure the blossom if possible.Just aswe were about to leave the canon andjust as the sun wassetting we looked back of us. We saw the rainbow which looked as if it reached from one side to the other. Camped at dark at the Cedar tree [1 mile from junction of Snake Gulch and Kanab Creek], found water in pockets, making 24 miles.

Thursday March 7th

Started at 9o'clock Madewithin twomiles—the "Kanab Wash" another Canon. The sceneryjust as wonderful, tho not as beautiful to me. Making only 15 miles, the road being hard both of man and beast on account of the

Ellen

111

Powell Thompson

willows.11 Also the rough road Got in camp at 6 o'clock Found three plants today

"Pipe Springs" Friday March 8th

Got here at half past two (2 1/2 o'clock) after one of the wildest rides have had.12 Broke camp at 9 o'clock, coming through still another canon [Pipe Spring Wash] in which I found a cactus in blossom, which I put up Then instead of following through the canon, Harry struck off for Pipe [Spring] The wind blew very hard, and I loped most of the wayfor 8 miles

Saturday and Sunday, March 9-10, were occupied with a trip to Kanab. Nell briefly noted on Saturday: "Cap D[odds],Jones, Harry and I came to Kanab today. My business was to get my boot mended, Harry to get supplies for another trip Slept in an empty house on the Fort." And on Sunday: "Finished work by three o'clock and started for Pipe Springs which we reached at 7 1/2. I rode Bay Billy Johnson joined the party Came with us."

Then follow ten days in which Nell's diary entries amount to little more than short and, for the most part, quite dismaljottings. Much of the time she was sick, but she managed to do some mending and write letters to family members and others from her bed On three of the

112 Utah Historical Quarterly

Cacti in Kanab Canyon near the Grand Canyon. Photograph byJohn K. Hillers in the Hillers Collection ofPhotographs of the Powell Survey, 1871-1900, National Archives.

11 Gregory, "Diary of Almon Harris Thompson," p 70; Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p 185 The difficulty of dealing with the willows in Kanab Canyon the next day was mentioned by other members of the party besides Nell Thompson wrote: "Wash much obstructed by willows"; and Dellenbaugh added some detail to the problems for the horses, which Nell inferred: " the thick willows pulled the packs loose One horse fell upside down in a gully, but he was not hurt and we pried him out and went on."

12 The wild ride included seven miles in Pipe Spring Canyon and then the climb up and out over the 500-foot canyon walls It was not too exhausting, however, to prevent collecting and pressing an interesting cactus

Ellen Powell Thompson113

days she noted that she "took time," her contribution to the work of the expedition. Beyond this she had little spirit and little to say. Monday, 11th: "Sick all day Harry atwork on map Jones andJohnson went to put up a flag. Clem and Hillers came, took 50 views. Wind blows."

Tuesday, 12th: "Mended some but in bed most of the day. The wind has blown terribly all day."Wednesday, 13th, things improved: "Sewed most of the day. Feel some better. More wind than ever." And the following day, Thursday, 14th, was a good day: "I feel well again. Have done some washing, lots of mending, written to Martha, Mary, Bram [her sisters and brother] and Mother Thompson Took time." But it was a short-lived reprieve from her indisposition. The next four days' notes are brief and offer no explanations. Friday, 15th: "Sick all day.

Wrote to Mrs. [?].Took time." Saturday, 16th: "Wrote to Lida and Walter Mended." Sunday, 17th: "Sick, but wrote to Frankie [?]."Monday, 18th: "Sick all day. Took time." And on Tuesday, March 19, she recorded only that the mail came; she received several letters

During this period of inactivity for Nell, the rest of the party was busy around the Pipe Spring area: recording the topography, gathering survey data essential for the drawing of the map of the region, shoeing the horses, replenishing photographic chemicals, copying

Lake in Kanab Canyon about three miles above Kanab. Photograph byJohn K Hillers in the Hillers Collection ofPhotographs of the Powell Survey, 1871-1900, National Archives.

Lake in Kanab Canyon about three miles above Kanab. Photograph byJohn K Hillers in the Hillers Collection ofPhotographs of the Powell Survey, 1871-1900, National Archives.

bearings, putting up a monument, making observations, putting up the flag, taking pictures The Professor was principally occupied, however, with planning and making preparations for a trip to Mount Trumbull, a prominent volcanic peak to the southwest in the Uinkaret Mountains. The entry in Nell's diary for Wednesday, March 20, makes it clear that she intended to be part of the party: "A very busy day for all Shall start in the morning." In spite of several days of poor health during the previous ten days, she obviously had no intention of staying behind On the following morning the horses were packed once more, and the party set forth on a straight route over level terrain from Pipe Spring to Trumbull

Thu[rsday

March] 21

Started at half past 10 o'clock. When not more than two miles from Pipe Springs Clem let go his horse while helping Hillers fix the pack Off it run—lost his gun Harry went back, helped him hunt for it—until two— did not find it. Clem remained to hunt.

Found a new plant—an Umbelliferae [Parsley or Carrot Family]. Made camp at the "Wild Bank pocket" at 6o'clock. Made 16 miles.

It was a four-day trip to Mount Trumbull. On the second night out (Friday, March 22) the party camped on a gulch, where there

114 Utah Historical Quarterly

Pipe Spring National Monument, 1881. Sketch by visiting French artist A. Tissard (inset). USHS collections.

was no water and the grass was poor. Nell said nothing of that day, only that they "made dry camp in the foothills of the [?] Mts." The following day, after an early start, they happily found water—clearly a lovely sight to Nell, who left a more detailed description than the other diarists—and camped for the rest of the day.

Sat[urday March] 23rd

Started out by 7o'clock without breakfast Harry,Jones, and Cap went on ahead to find water. At about 10 came to some wickiups and near by Harry's horse hitched. While waiting there I drew a very large cactus. Soon Harry halloued, then came. He had found water, half a mile away. We were all soon looking at the animals drinking out of the "Rocky Pool." It is a pocket in the rocks holding 500 bbls or so of water Had to climb down 80 feet over rocks to get to it. At first expected to have to bring it up to the horses, but on the opposite side found a trailwhere the Indians had gone in themselves and taken animals in to water. So they drove the horses around on the other side, then down, only letting four or five go at a time At 11we ate breakfast Picked and cut boughs for beds, put up tents, etc This is a lovely spot, or at least wonderful mountains in every direction. Here we are under the shade of cedars and pines. It is warm as a day inJune in central Illinois], tho we can see snow-capped mountains all around us. The water in the pool isvery clear, cold and soft, as it iswhere the sun never shines on it, and ismelted snow and rain [?] from the rocks and hills all around Took two pictures of it this afternoon. I climbed the rocks on the east of it which were covered with live oak, making a regular oak forest.

The following day provided an opportunity for undisturbed botanizing—successful, but with an unhappy ending

Sunday [March] 24th 1872

Harry and Cap. went in one direction,Jones and Fred in another, to explore. I took a long hunt for flowers. Got more of the same Umbelliferae. Found the Moss Pink—Polemoniaceae [Phlox or Polemonium Family] Drew a large Cactus growing by the pool Got heated Went to bed sick

In spite of not feeling well the night before, Nell climbed to the summit of Mount Trumbull the following day. According to Dellenbaugh, the top commanded a magnificent view in all directions. He also reported that it was not a very difficult ascent, which apparently could not be said for the route followed by Harry and Nell in the descent. 1 3

Monday [March] 25

Climbed Mt. Trumbull. Harry, Cap., Fred, Jones, Johnson, the photographer [James Fennemore] and Hillers went. Made flag on the Mt. Took time. Harry went to point out views to take—raised a monument.

Ellen Powell Thompson 115

13 Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p 187

Harry and I came down a new way, very hard both for us and the horses. Found a flower, a Scrophulariaceae [Figwort Family].Got into camp at sundown. Very tired.

On March 26 the Professor decided to move camp to a nearby lava bed and spring Here they stayed until April 5 The men continued to explore the area, seeking trails that gave access to the river and gathering data for the topographic map. Part of the group returned to Kanab for supplies, which were running low. The weather was bad, too stormy and cloudy for photography Snow made trails very soft underfoot But with the advent of spring, flowers were coming into bloom: "Many flowers in blossom," the Professor recorded in his notes. During this interval Nell continued her plant collecting, apparently in the area of the campsite (she mentioned only one trip out in ten days), in spite of the fact that she was sick most of the time, unable to do anything or even get out of bed Although she nowhere gave a reason for her illness, she was probably debilitated by a gastroenteritis brought on by inadequate food and bad water (the Professor succumbed on one occasion) Her notation, "Have worked with my plants all day," suggests that she made more collections than the few she specifically mentioned in her brief daily record.

Clem's diary, written at the base camp in Kanab, gave a more graphic report of this interval: " Thompson's party snowed in at the lower end of Mount Trumbull. Feed for horses and wood for fires exhausted. ... It has stormed steadily."14

Tuesday [March] 26th

Started for the spring Harry found on the 24th. Found the Painted Cup—Scrophulariaceae, Castilleja—making camp at 2 o'clock in an oak grove. It seems quite like home, and as it isquite remarkable to see oaks so large, in this country, Imake a note of it. Tho' they are only what would be called Scrub Oaks in Ill[inois]. Our tent is under two of them. The spring is tinctured with iron—which makes the coffee black—and tastes in the bean soup

Went to bed sick Men came from Mt T[rumbull]

Wed[nesday March] 27th

Cap andJones went to the river Harry at work all daywith his topography. Went over to the ranch to see about getting into the river. I have done nothing. Sick.

116 Utah Historical Quarterly

14 Kelly, 'Journal of W C Powell," p 404

Thursday [March] 28th

In my search for flowers found two new ones of the Umbelliferae— and one of the Santalaceae [Sandalwood Family]—Comandra [Bastard Toadflax] Harry at work

Friday [March] 29th

Harry and Fred [and] myself went to see the crater of the lava bed Harry to show Fred what he wanted him to sketch I found and put up an Elaeagnaceae [Oleaster Family]—Fred remained Harry and I got in at 2— found Cap and Jones here Had been to the river and climbed down to it 500 feet, cannot get animals down Jones brought me three flowers, but do not make out what they are as he brought no leaves Hard snow storm

Saturday March] 30

Harry and Cap went to hunt a way into the river. Jones and Fennemore went to Kanab, are to bring the wagon and supplies in 8 days to us near St George They will have a hard day as it has been either snowing or raining all day. I have not been able to sit up.

Sun[day March] 31st

Been snowing all day, been reading in tent out of Harpers "The Scott Centenary of Eden [?]" "Old Books in New York" "English in School." In the latter are expressed my ideas —At four went to find flowers, found two While we were eating supper Harry came. Had found a way as he hoped to the river, and so he left them to go in and came back to do other work.

Monday Apr[il] 1

Harry was very sick all night—had an attack of cholera morbus—did not get to sleep until four o'clock this morning. Has been resting today. Is much better. Cloudy, so he and Fred could do nothing.Jack and Andy went to the river to get views.I made a peach dumpling for dinner.

Tuesday, Apr[il] 2nd

We woke this morning to find that snow had fallen to the depth of 2 feet during the night. Not too comfortable at least is it to be up on the mountains in such a storm with nothing for a cover but a small A tent. Have worked with my plants all day.

Wednesday [April] 3rd

Still very cloudy so that Fred cannot do his work. The men all got in today. Dodds andJohnson at 6 o'clock and Hattan at 8. The two first have been to find awayinto the river.

Thursday [April] 4th

It looks more like clearing off today Harry went over to Whitmore's [Ranch] to find out what he could about the trail to St George Harry says the stock can get little or nothing here to eat, and so theywander miles away. If it isclear tomorrow will stop another day and do the work here, tho as the men say "we are most out of grub." If not, will start for St. George. I have worked some with my plants, but have not been well enough to do much.

Ellen

117

Powell Thompson

In her weakened condition Nell must have found it difficult to help break camp, get her plant collections and pressing supplies packed up, mount her horse, and take to the snowy mountain trail as they headed for St. George. "The ride has used me up," she wrote at the end of the day's journey on April 5 Despite the difficulties, Nell's account of the next four days' trip northward through snow and sleet and on critically reduced food supplies, finally arriving at Berry Spring near Toquerville, constituted the most descriptive and complete writing in her diary and contains details not recorded elsewhere

Friday

[April] 5th 1872

Animals ready—packed and saddled at 8o'clock, tho the snow is deep and ground under it very soft. Had a hard pull up Mt. Lucy—ground so soft that it has been hard for animals and tiresome for all the folks. Made 15 miles Are making dry camp, dry for horses, but we have enough water in kegs for bread and coffee. The ride has used me up.

Sat[urdayApril] 6th

Started early, looked dark, and really was so cloudy that Harry could find no wayout, but started in the right direction. Had gone not more than a mile before we were at the top of a perpendicular wall. Cap. Dodds, who finds the trail and leads, says, "Well, here we are come to thejumping off place." And sure enough it looked like it—as if, should his horse take another step, he would be to walk into the ocean One man said to another, "Fred, here is Buffalo Harbor," and one could not rid themselves of the idea that they were on the shore of an immense lake (Lake Michigan) in a storm. Until the fog cleared, and we could see that we were at the top of a line of cliffs, and at this point 600 feet down to the foot Asno use [to] try to go over mountains in such darkness, so we sort of unpacked, built fires—laid blankets—tents, to catch snow, and soon had our kegs filled. Still snowing, so beans and peaches are put on to boil.At 2o'clock we have eaten them and at half past are off again having had (jhust has gud a ting as ude want) or as the Mormon members of our party expressed it, This is as much of a Godsend as the Quails lighting in such numbers [on October 9, 1846, during the Mormon exodus]

And surely that expressed it, for the horses had had good grass with lots of snow in it for several hours—and we had snow melted for bread and coffee should we have to make dry camp But cannot really call it dry, for it has been raining or sleeting or snowing ever since we started, tho it has been clear enough to see where to go, and got down into the valley of the cliffs nicely. But as the snow melts as fast as it falls, our water which we melted will come in good Made not more than 10 miles [Thompson estimated perhaps only 5]. Came into camp early on account of wood being here in a grove of cedars, aswe are now come into a country where there is little wood.

118 Utah Historical Quarterly

Sunday [April] 7th

Started early. Sleeted till noon, and facing a Norwester makes one chilly, so that we walked much of the time to keep warm. And this in "Dixy Land" too—or at least we are verging into it [Dixie National Forest lies to the north]. Were very uncertain about the road or trail, sometimes striking one and keeping it for some miles, then leaving it, only aiming to keep the general direction. But this will not do in this country, for it is cut up with canons, many of them impassable. [?] did this P.M. to one where we could look down 1500 feet to itsbottom. Two or three went off to explore. I found four new plants. Meantime Harry said when he came back we had gone 20 miles out of our way,but had found water in a canon four or five miles away. Set off to it, had brush (sage and greasewood) to burn, brought water up out of the canon for bread and coffee. That night found five new flowers, put them to press. This country is perfectly wonderful to me, perfectly cut up with canons, no streams of water, but to take the place of creeks and rivers are canons Few springs, and where there is one some Mormon has settled and has a ranch, sometimes has his family or families with him and living in adobe houses with very few of what our ladies in the States would consider the necessaries of life much less the comforts His two or three hundred head of stock feeding on the grass and coming to the spring to water Ate all of our flour tonight. Put in beans to boil for breakfast.

Monday [April] 8th

After our breakfast of beans, started at 8 o'clock. While the horses were being watered Iwent down into the canon, found one new flower. Soon found a way down into the canon, rode an hour in it There were many cattle feeding. In Ill[inois] the people would think cattle would starve, and those really were quite on the verge of starvation. Were soon across the canon and in a valley with mountains on our left and high cliffs on

Ellen Powell Thompson 119

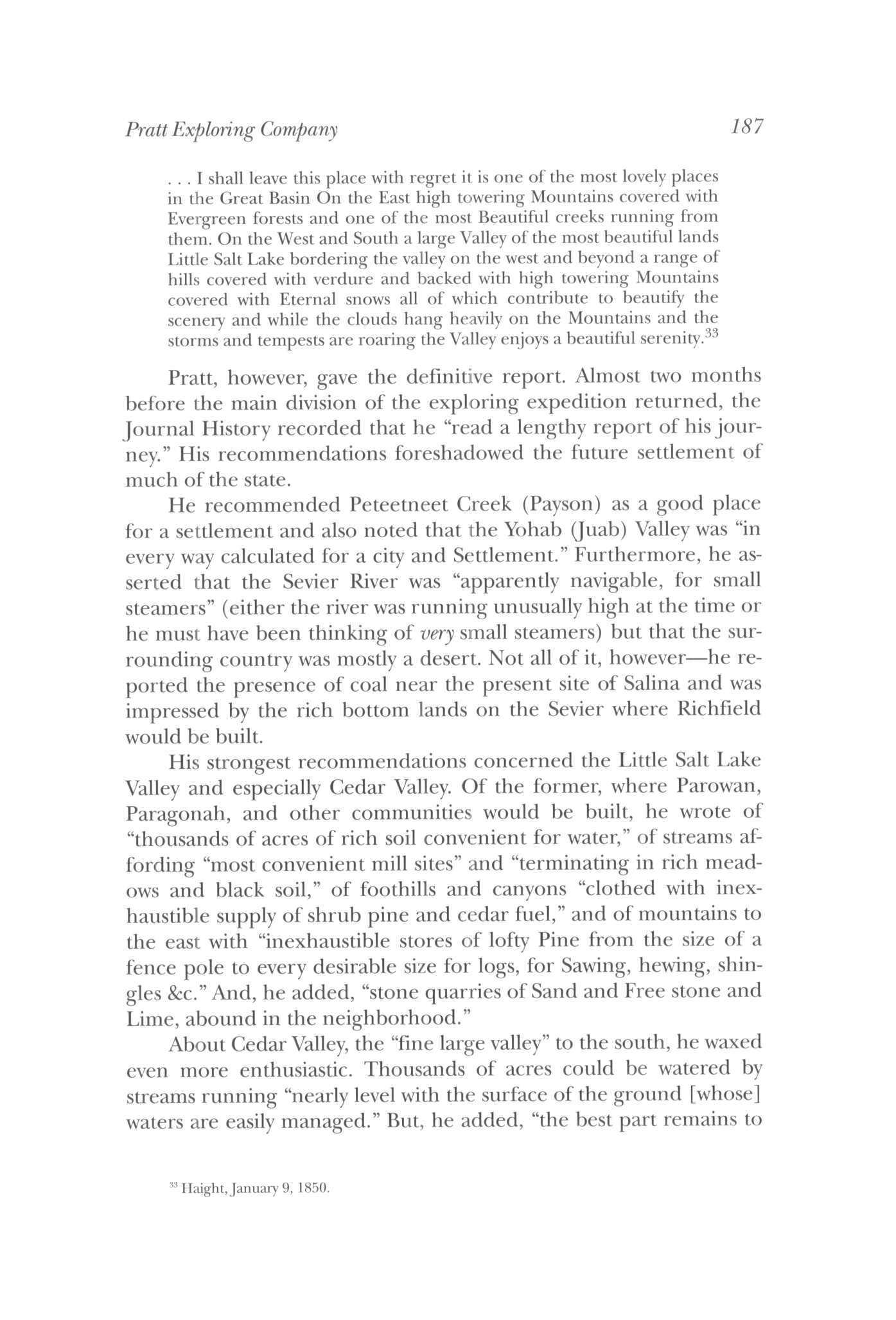

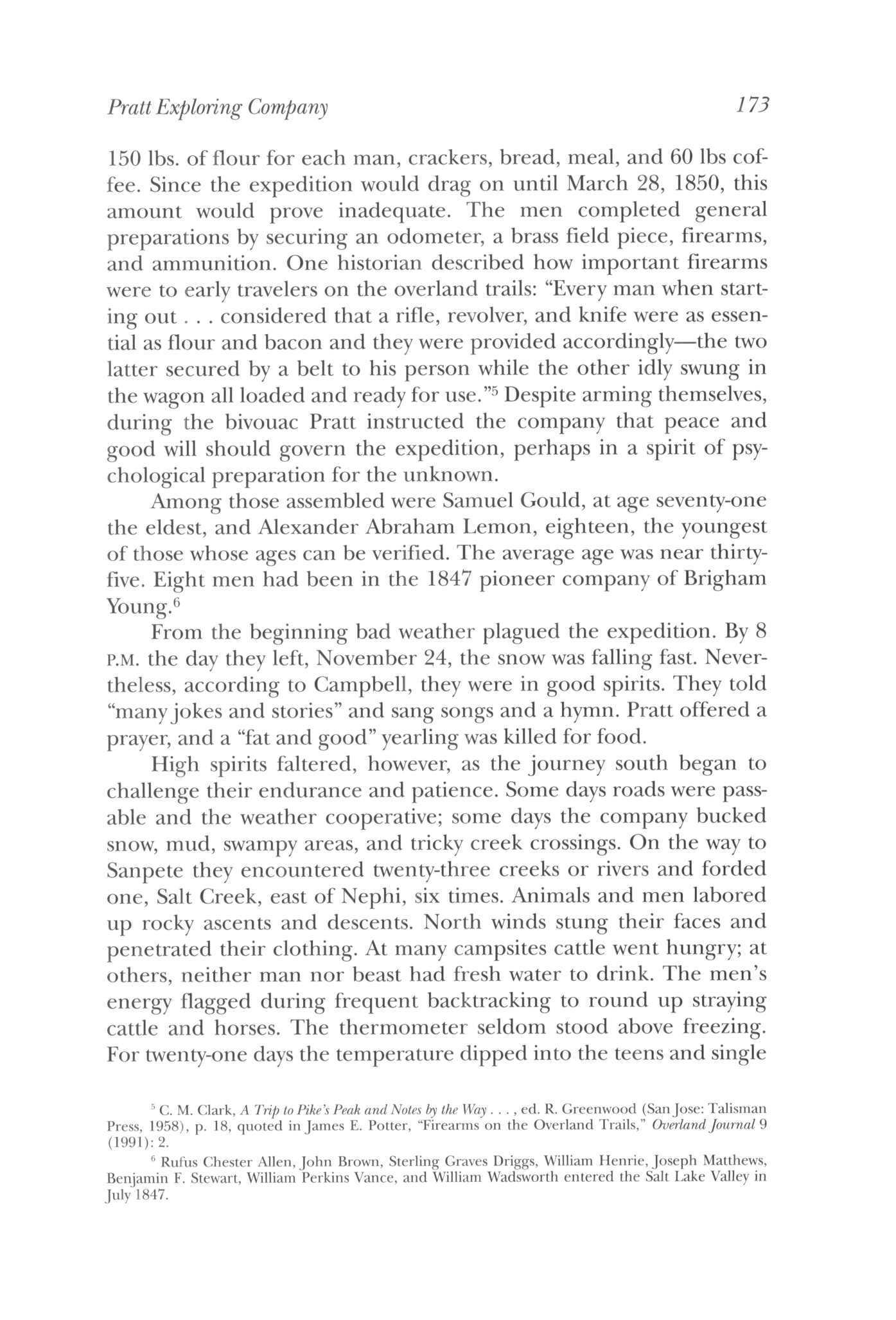

Region south of Toquerville, south of the Virgin River, with the Pine Valley Mountains in the distance.

Photograph byJohn K. Hillers in the Hillers Collection ofPhotographs of the Powell Survey, 1871-1900, National Archives.

our right, then up on the cliffs in front of us. And O! the view from this point—Mountains—mountains—cliffs—peaks—White, black, red, and with the glass can see St. George 20 miles away. Washington 15 miles, Toquerville 12 miles away Here Harry and Alfred [Zenny] leave us with the best horses to find what he can do for "grub,"asit istwo o'clock, and everything is gone but coffee and beans We overtook him at Gould's Ranch Had bought corn meal and milk, but had to wait for the cows to be brought, so Iwaited. In an hour the cows were milked. It was put into our kegs and we were off. I should mention here that the corn bread the woman gave uswith the cup of milk tasted good [underlined three times!]. Met an outfit of miners three miles from the ranch I forgot to mention a thing which looked strange to me. When the cows had come, the man came in and said, "Woman, the cows are here, be off and milk them and not keep the stranger waiting."And as the wife [sic] put the crying babe on the floor, snatched up the pail and started off, and as she passed out of the door he says "No dallying round and [?] woman." Well, she seemed to think it was all right "and so long asyou [?]."Meantime the man sat down after sending a larger baby out with the one put on the floor and talked with us, think[ing] he was agentleman, I suppose.

The viewfrom the top of Hurricane Hillwas fine. The sun wasjust setting. It is a mile or more from the summit to the foot and Toquerville is plain in sight—and is the most pleasing sight witnessed for months, for it reminds one of home, with its stone houses and many green trees. It receives its name from the black lava surrounding it on all sides, "Toquer" being the Pa-Ute for black. It is a town of inhabitants and has been settled years.At the foot of the hill we leave the home view of the village and before us on to our right is scenery for the painter. Way off and up reaching to the western skywhere the sun hasjust gone out of sight, but illumining the skywith the brightest hues, are the white-capped Pine Valley Mts. Then at their feet a range of lava hills [this word crossed out] peaks, then jutting right out of the black hills are sharp peaks of red sandstone, bright red—and lower down at the feet of these are white sandstone hills, and at the feet of this a green bank of the Rio Virgin, 'tho the river could not be seen. Reached Berry Spring at 9. Found Jones, George [Johnson], Fennemore, and Glen[?] with [?] and mail from Kanab Letters ["s" underlined three times] for me. Two from Martha and two from Bram. O! how cheering such dear letters are. (A nice little painting from Frankie, a little letter from Maud [?].Nothing to put under our blanket in bed.

For the next two weeks Thompson made his base camp at Berry Spring. The snowstorms in the mountain country had made topographic work well nigh to impossible, and he decided to move to the lower country around St. George. He sent his men out in small parties to various destinations to continue gathering data for the map He himself handled the business details of the expedition, checking supplies and equipment and taking care of monetary affairs in town.

120 Utah Historical Quarterly

Nell explored the region around the camp and visited with other campers at the site, but on the whole her diary entries reflect little enjoyment. Her energy seems spent by the long expedition in the field, and many days she is sick. "I am not well enough to drag round," she wrote.

Camp Berry Spring Tuesday [April] 9th

Went down to look at the spring and river. Found a willow in blossom. The spring comes out of the rocks, warm water and impregnated with sulphur and very hard So we shall not enjoy drinking or using it, tho' it is water so one [is] thankful to get it. The Rio Virgin. There is a fort here built of stone some three years since as a protection from the Indians, and three or four acres of land fenced with a stone wall for a corral for cattle. Two brothers by the name of Genny [?] were stationed here to take care of a cooperative heard [herd] One having a wife, they were not here one year when the Pa-Utes became so troublesome that the three started for a settlement to obtain help. They were found all killed, horses taken, harness and wagon cut to pieces and the ranch has not been used since.

Wednesday [April] 10th

Harry went to Toquerville. Three families in camp here today on their way to the Paria [River]. The wind blew fearfully today, thought it would surely blow the tent down and away. Sick all day, but this evening went over to see the women encamped and hard it looked to see poor fagged out women and children taking such a journey. An old man 80 years said he had been sent on missions for many years. Ten years ago he was sent into this southern country and had used up his all $1000 here, and must now die a poor man. He hoped this would be his last move. I think itwill. Several outfits of miners have passed here.

Thursday [April] 11th [The men] getting ready to start on trips tomorrow An outfit of miners stopped here this morning Had a quarrel Two of them wanted to go to the diggings one way, the other another, so they split up Harry bought the flour of the two that were going to return It is quite a common thing to meet men returning from the mines, everything used up

Friday [April] 12

Cap D, Fred,Jack and Fennemore started for the Wingkaset Mts [according to Thompson, the Mingkard Mountains, now called Virgin Mountains] with rations for 12 days Jones, Johnson and Andy with six days rations for the P b [Pine Valley Mountains] I tried to write letters today, but the fact isI cannot—I am not well enough to drag round

Sat[urday April] 13

Harry, George and I started at 11 o'clock for St. George. The wind hadjust begun to rise and by the time wewere half a mile off could not see one rod ahead of us for the sand in the air And it blew harder and harder

Ellen Powell Thompson121

all the time until itseemed asifweshould surely be blown from our horses At one time when wewere riding bythe side of high cliffs, stone and gravel were blown into our faces. We reached St. George safely, however, at four making the 15 miles in good time, having seen nothing of the country Went to Mrs Ivins, she and Leady [?] were very cordial. Went to the theatre at night—saw the "Seven Years a British Soldier," all home actors, and all did well.

Sunday [April] 14th

Talked and read all the forenoon, P.M Harry, Caddy, Mrs Ivins both called on a lady by the name of whose husband was killed by the Ind[ians] five years ago. He had gone off on business for the settlement, left camp alone to look for horses, and did not return Went then to call [on] Mr Dogl [?], he a very outspoken pleasant man, she a real lady. Had things very homelike Were treated to cake and homemade wine Tell about St. George [then space on the page]

Monday [April] 15th

Caddy and I went up the bluffs north of town to some springs and a cave in the rocks Had a fine viewof the place Went to a dance at night

Tuesday [April] 16th

Went to the store and got calico etc for summer. Started at three for camp. Got in atjust dark.

Clearly Nell intended to describe the town of St. George in her entry for Sunday, April 14 (above). She left a space in her notebook but never filled it By chance, and quite uncharacteristically, her husband included in his notes for that day an interesting description of St. George, a refreshing departure from his usual brief comments on only scientific and business matters. To complete Nell's account, and fulfill her intentions of more than a hundred years ago, Thompson's record is included here:

St. George is a very pretty town. 1500 population. Is watered by springs, large lots, well built. Seems to be considerable enterprise in town. Nice Court House of cut stone. A tabernacle of cut stone, school house, etc. People seem much above common run of Mormons. Have two taverns, three stores, a tanning, shoe, and harness shop. Are talking about bringing the Virgin [River] into town Many trees, mostly cottonwoods along the streets Figs, apricots, peaches, apples, etc grow in open air, almonds as well Grapes are abundant; the black ham berry and mission flourish, but the Isabella is the most esteemed for wine making.15

The remaining ten days at the Berry Spring camp were lackluster ones for Nell She wrote only brief diary notes: the comings

122 Utah Historical Quarterly

15 Gregory, "Diary of Almon Harris Thompson," p. 75.

and goings of the men; an errand to get grain and flour; looking for a lost horse; one man lame from a fall while climbing the mountains to 10,000 feet; washing clothes; cooking a duck for dinner. She mentioned the weather: "Another windstorm," and "The weather is very warm, stood at 98 1/2 at 1 o'clock in a tent—this is almost unbearable. Have tried to read the newspapers some. Make but little out." One observation recurred with increasing frequency: "Sick all day," or "Very sick all day." But in spite of all, she managed to add some plants to her collections: on one day, "Found two new plants," and on another apparently good day for her, "Took a long walk on the bluffs. Found 7 new plants. Identified and put them up."And on the evening of the same day. "Tonight Harry and I went out for a walk, found two plants."

Then follow three days in St George, April 27-29 Some of the men went to the Pine Valley Mountains; others to the Paria River to check on the boats; Thompson explored the confluence of the various mountain ranges, washes, and canyons. On one of these days Nell was sick all day. The following day, the 29th, a note of despair entered her record: "Tried to write today but could not. I feel so sick all the time that I am afraid to go on."

Ellen Powell Thompson123

St. George, Utah, 1876. USHS collections.

But go on she did. They broke camp at 10 the next morning (Tuesday, April 30), rode twenty miles, and ended up making a dry camp They had crossed the Santa Clara River, and heading westward their destination was the Beaver Dam Mountains. Nell wrote of the day: "Found three new plants. . . . Saw a whole band of Indians and their huts. One guided us to the trail for a string of beads." In hisjournal Clem wrote of this incident: "The Indians swarmed about as we passed; when they caught sight of the lady, they shouted in astonishment, 'Squaw! Squaw!'"16 The next day they broke camp early—6 o'clock, and after 10 miles found an alkali spring ("It was surcharged with alkali, and horrible to drink," Clem noted17), which furnished water for both man and beast. As they continued on Nell noted—"very hot. Found 15 new plants today. At 6 PM found a pool. Went in to camp." The following two days were disastrous for all apparently. Neither Nell nor her husband made any notes. Were they all sick? On the third day, May 4, Nell recorded: "Sick all day. Could not even change driers on plants Laid under trees all day The water yesterday made me much worse and in fact has made all sick and the horses too." But they continued their exploration of the Beaver Dam Mountains nevertheless. Then, after two days of hard riding and dry camps they returned to St. George. The next day, May 7, they moved on to Fort Pierce, sixteen miles. Nell found four plants that day. The following day they made fifteen miles, mostly in the rain, arriving at Pipe Spring by 7 in the evening "Sick all day," Nell wrote Two days later they were back at their base camp in Kanab. 'Very sick," Nell noted. On Sunday, May 12, Harry Thompson wrote simply, "In camp First day of rest for five weeks." Nell wrote on that same day: "It seems good to think we shall get some rest. I feel used up. More so than I ever felt in my life." Also on that day Captain Bishop, a topographer with the expedition, recorded in his journal: "Mrs. T[hompson] looks careworn and thin It has been a pretty rough trip on her."18

Nell was then thirty-two years old. That she looked and felt spent after such a grueling schedule under such difficult conditions is hardly to be wondered at. Rather one can only marvel at her durability, aswell as that of all the expedition participants.

16 Kelly, 'Journal of W C Powell," p 412

17 Ibid., p 413

18 Charles Kelly, ed., "Captain Francis Marion Bishop's Journal, August 15, 1870-June 3, 1872," Utah Historical Quarterly 15 (1947): 234

124Utah Historical Quarterly

It comes as no surprise that Thompson decided that Nell should not accompany him on his next journey eastward across the unknown country of the Red Lake Utes, a hostile tribe, to the mouth of the Dirty Devil River. Dellenbaugh wrote: "Mrs. Thompson was to stay in Kanab, for Prof, decided that it would not be advisable for her to accompany him on thisjourney, although she was the most cheerful and resolute explorer of the whole company. A large tent was erected for her in the corner ofJacob's [Hamblin] garden, and she was to take her meals with Sister Louisa [one ofJacob's wives], whose house stood close by. With Fuzz, a most intelligent dog, for a companion in her tent and the genial Sister Louisa for a next neighbour she was satisfactorily settled."19 Nell's diary entry of May 14 added more details: "Came back [to Kanab] from Johnson [a settlement 14 miles east of Kanab] Found a yellow lily—14 miles seemed a long ride alone [the Professor remained in Johnson to work] Harry wants me to stop here [Kanab] Commenced to board at Hamblin's today at $5.00 per week. She doing my ironing and washing for it. She to buy [?] tea, sugar or anything I may have to sell her." Dellenbaugh's characterization of Nell as a "resolute explorer" is well demonstrated by this two-day trip to Johnson with Harry, fourteen miles each way—on horseback, of course—and botanizing as she went along. Only the day before she had declared herself more "used up" than she had ever known.

On May 16 Nell's diary for 1872 came to a close. The last entry is brief: "Worked on plants some. Am feeling better—Harry busy."

THE PLANT COLLECTIONS

Botany was not of primary importance to Major Powell on his Colorado River expeditions, although the description of him by one writer as a person of "only a limited interest in the biological sciences" would hardly seem to be borne out by the herbarium of almost 6,000 specimens he assembled in his early years. 20 Despite his wide range of interests, the Major's chief concerns on the second river expedition were the geology, topography, and physical characteristics of the area and the description and recording of the maze of

Ellen Powell Thompson125

19 Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p 195

20 Arthur Cronquist, Arthur H. Holmgren, Noel H. Holmgren, and James L. Reveal, Intermountain Flora: VascularPlants of theIntermountain West, U. S. A. (New York: Hafner Publishing Company, Inc., 1972), vol 1, p 56; Darrah, Powell of the Colorado, p 41

canyons that it comprised. That the plants did not go unnoticed we can lay to the efforts of Ellen Powell Thompson, described byJoseph Ewan as an "acute frontier collector."21

Ellen Thompson was not the first plant collector in Utah and Arizona. She was preceded by John Fremont (1843 and 1845), Howard Stansbury (1849 and 1850), and Edwin Beckwith (1854), all attached to various expeditions sponsored by the U.S. government. Nor was Nell Utah's first woman collector. Jane Carrington of Salt Lake City collected plants in 1857 in the Great Salt Lake basin. The fifty-nine herbarium specimens attributed to her, including at least two new species, are housed in the Durand Herbarium at the Musee National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris.22 Efforts to find out more about Carrington's plant collecting and to identify her more completely have not been successful to date.

Ellen Thompson andJane Carrington are only two examples of the large number of nineteenth-century American women who made important contributions to our knowledge of the country's flora Early educators, such as Amos Eaton and Almira Lincoln Phelps, encouraged women to study botany, which was viewed as an ideal and healthful pursuit. Nell would have had at her disposal the popular text known as Mrs.Lincoln'sBotany{FamiliarLectures on Botany by Mrs Almira H Lincoln, Hartford, Connecticut), already in its third edition in 1832. In the 1850s when Nell was attending Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, and perhaps getting her first exposure to the formal study of botany, there were 150,000 copies of this book in circulation. One can speculate that her interest in botany was also whetted by her older brother's intensive plant collecting at this time—John Wesley Powell must have worked continuously at it in order to amass 6,000 herbarium specimens. Having been reared in the Middle West, Nell doubtless found the plants of the Southwest's canyon country very enticing Such a different flora, combined with her natural love of adventure, resulted in an interest

21 Joseph Ewan, Rocky Mountain Naturalists (Denver: University of Denver Press, 1950), p 42 There is no indication that Ellen Powell had any official appointment or even recognition as botanist to the expedition Her interest in collecting the flora was apparently self-motivated Her diary makes it clear, however, that her husband was entirely supportive of her efforts and that the other members of the field party were interested and even sometimes contributors to her collections

22 James L. Reveal, "Comments on Two Names in an Early Utah Flora," Great Basin Naturalist 32 (1972): 221 Elias Durand of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in his article "A Sketch of the Botany of the Basin of the Great Salt Lake of Utah," written in 1859 (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 11 [n.s.]: 155-180, 1860), summarized what was then known about Utah's flora, based on the collections of the individuals mentioned here

126Utah Historical Quarterly

Ellen Powell Thompson127

compelling enough for her to endure the severe difficulties of life in the field that she records in her diary.23

An impression is generated in the literature, scant as it is, that Nell's plant collecting was a time-passing activity to fill the empty hours while her husband was away in the field. One account stated: "While the men were out exploring, Mrs.Ellen Powell Thompson . .. remained behind in Kanab. Asa non-Mormon in a newly established Mormon community, she likely had a great deal of spare time, and to fill it she collected plants."24 Another source described her diary as written "while staying in Kanab, Utah (1872) when [her] husband was off surveying the country."25 Numerous references in the journals of various expedition members and nowNell's own account give a quite different impression of Nell and her interest in botany

Clem Powell said that Nell "accompanied the Professor, being desirous of making botanical collections, and inspired by a love of adventure."26 As one of the youngest members of the expedition, Clem recorded more of the human side of the canyonlands exploration than the other participants. Thus hisjournal and letters are particularly helpful as sources of information about Nell's botanical pursuits. Far from remaining behind in Kanab, Nell accompanied her husband's field party far and wide: into territory north to Panguitch and the Sevier River, west across the Santa Clara and Virgin rivers, southwest to Mount Trumbull, and east to the Colorado.

Dellenbaugh reported an incident that well reflects Nell's love of adventure A land party that included Nell had assembled to visit the river party in August 1872 as they prepared to make their final descent of the Colorado from Lee's Ferry through the Grand Canyon. They tried out the EmmaDean by taking Nell and a few others up the river for a short stretch "so that they might see what a canyon waslike from a boat. Mrs.Thompson wasso enthusiastic that she declared she wanted to accompany us. Prof, took her as passenger on the Canonita [she rode on the cabin] . . . and . . . ran down through a small rapid or two about a mile and a half. . . . Mrs.

23 For studies of other nineteenth-century American women botanists see the following works by the author: "Maria L Owen, Nineteenth-Century Nantucket Botanist," Rhodora 89 (1987): 227; "Lucy Bishop Millington, Nineteenth-Century Botanist: Her Life and Letters to Charles Horton Peck, State Botanist of New York," HuntiaS (1992): 111; A Painted Herbarium: The Life and Art ofFmily Hitchcock Terry (1838-1921) (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992)

24 Cronquist, Intermountain Flora, p 56

25 Andrea Hinding, A S Bower, and C A Chambers, Women'sHistory Sources: A Guide to Archives and Manuscript Collections in theUnited States (New York: R R Bowker Company)

26 Kelly, 'Journal of W C Powell," p 412

Thompson enjoyed the exhilaration of descending the swift rushing water and still thought it attractive."27

Doubtless Nell's continual efforts at plant hunting and collecting, even when the trail was difficult and she was decidedly unwell, aroused an interest in the flora among other members of the expedition. Captain Bishop, one of the topographers, built a plant press and was enough excited by a plant he found to record in his dairy: "Found some fine specimens of the Pulse family a variety of wild Pea."28 He had a Gray's ManualofBotany; Clem had requested it of his brother Morris to give to Bishop. And Jones helped with the collections, although not too successfully, as Nell recorded: 'Jones brought me three flowers, but do not make out what they are as he brought no leaves [March 29]." That Nell heightened Clem's awareness can be felt in his vivid description of the botanical wealth and diversity that the area offered the botanist-plant collector, enthralling under even the most difficult conditions. He was obviously moved by the scene surrounding the 2,500-foot-high Table Cliffs of the Aquarius Plateau, with their pink and white limestone sides and ledges:

Against this brilliant background, the deep green of the pines shows handsomely Soon the barren plain stretches out before us, with its wearisome world of sage There are scentless flowers in shady places, bright, hued, and welcome to the sight. The pride of the desert, the queen of the mountain, is the many-tinted cactus There is a great variety of new and handsome species of this plant in Utah Mrs Thompson has safely forwarded living specimens to botanists and friends in the States. A field of many acres, filled with blossoms varying in color from the purest white to the deepest crimson, with yellow, pale-pink, and scarlet intermingled, forms one of those rare sights that partly repay the traveler's toil. The prickly stalks and fleshy leaves of the cacti are fit emblems of the arid fields and desolate rocks from which they spring; but the delicately-pencilled flowers awaken thoughts of the dawning days when we will loose the rein, drop the oar, and hasten to fields more fertile.29

The only indication of the totality of the Ellen Thompson plant collections is found in Clem Powell's journal. When describing the accomplishments of the second Colorado expedition, he wrote: "The plants of Utah have been gathered and classified. Mrs. Thompson has over 200 varieties They will appear in late editions of standard works on Botany."30 Nell carried along her plant press and drying blotters

27 Dellenbaugh, A Canyon Voyage, p 216

28 Kelly, "Captain Francis Marion Bishop'sjournal," p 230

29 Kelly, 'Journal of W C Powell," p 418

30 Ibid., p 405

128Utah Historical Quarterly

Ellen Powell Thompson129

thompsoniae

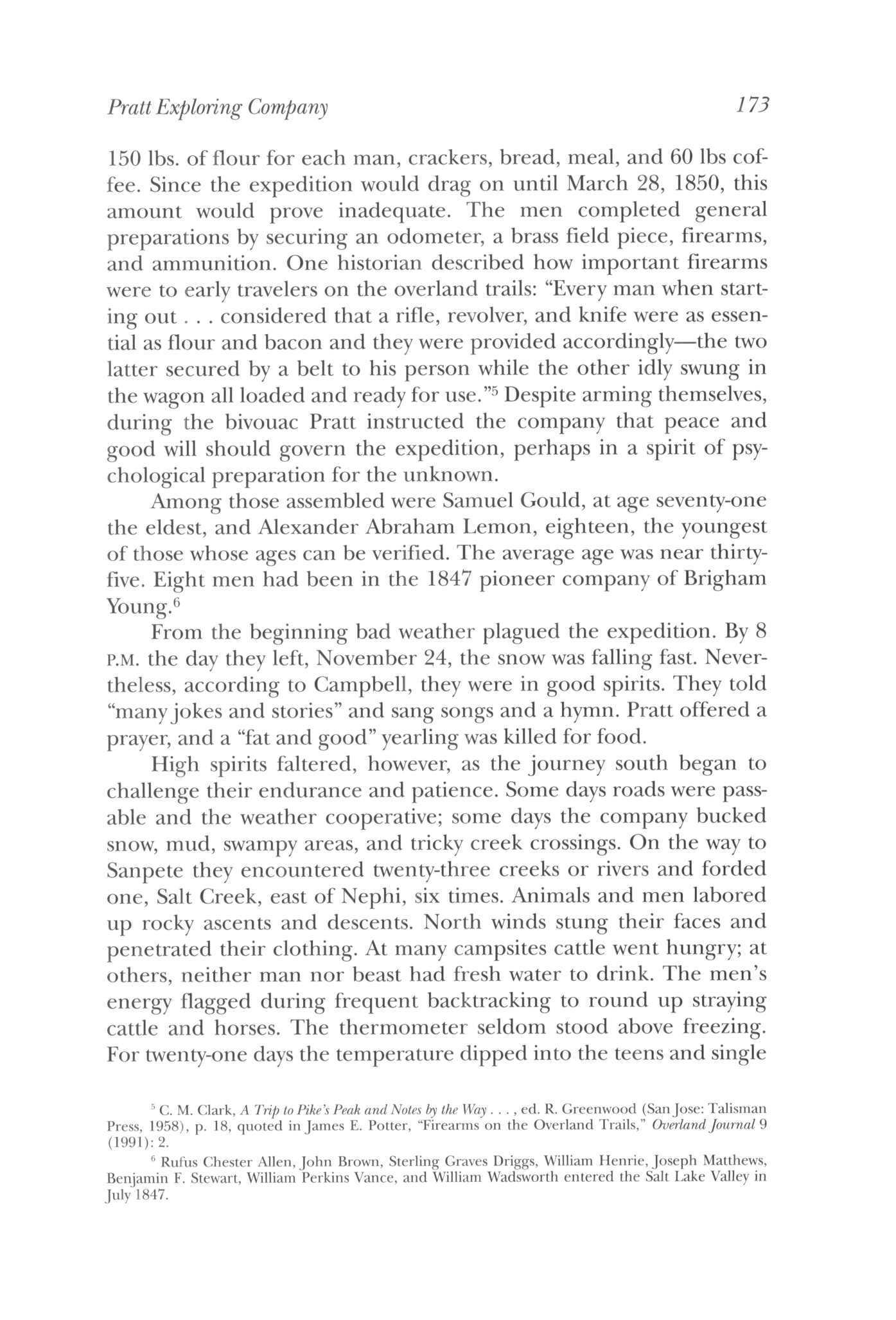

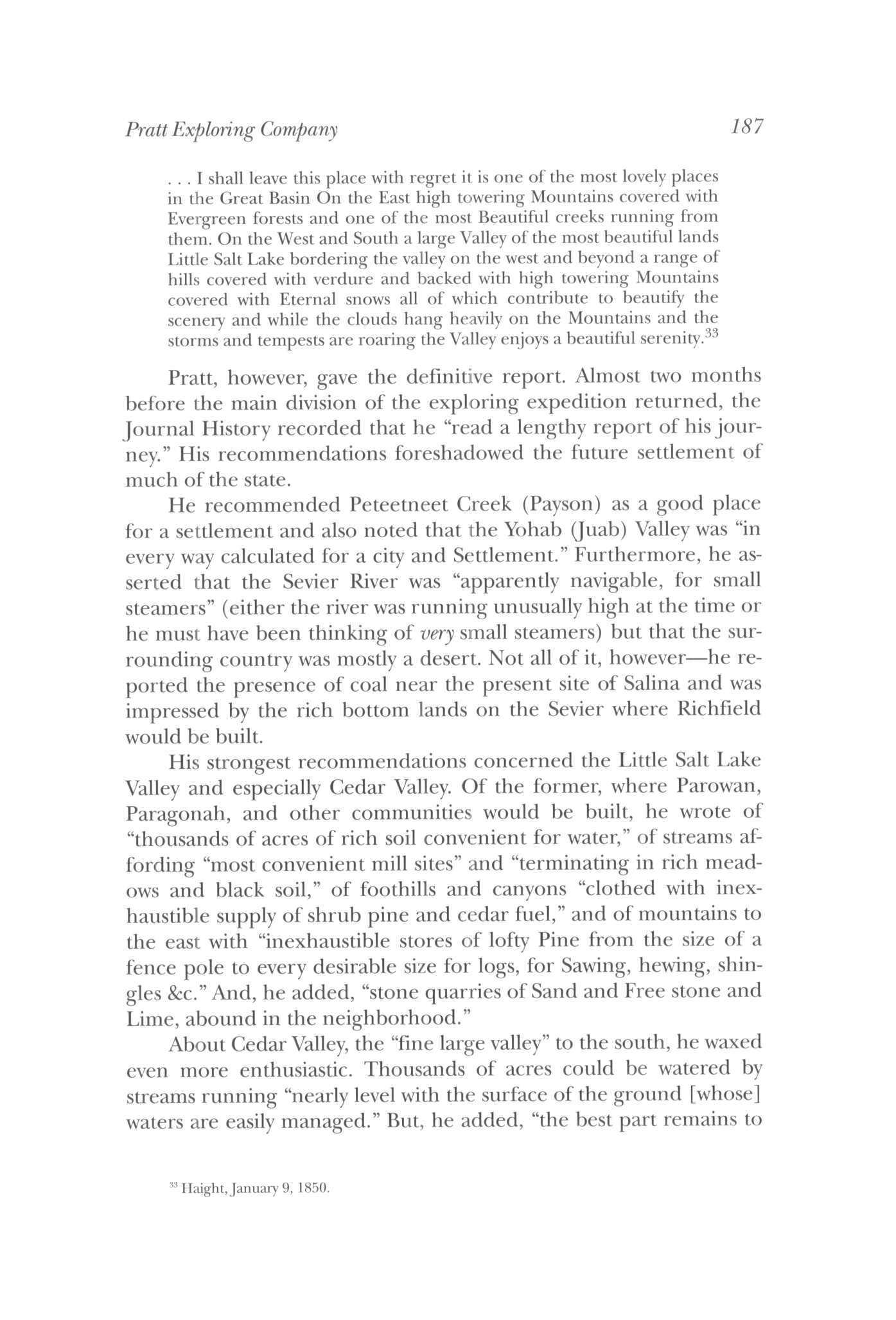

Three ofEllen Powell Thompson's plant collections that bear her name: Psorothamnus thompsoniae (ThompsonsDaka), Astragalus mollissimus var. thompsoniae (Thompsons Woolly Locoweed), both drawn by artist Bobbi Angell, and Penstemon thompsoniae (Thompson's Penstemon), drawn by artist RobinJess. Reprinted with permission from Arthur Cronquist et al., Intermountain Flora, vol. 3b (pp. 33 and 145, copyright 1989) and vol. 4 (p. 403, copyright 1984), the New York Botanical Garden.

and pressed her specimens while in the field. She told of working with her plants, that is, changing the driers so that good specimens would be obtained for later herbarium mounts. She corresponded with Dr. Asa Gray at Harvard University to whom she sent her specimens. They are still preserved in the Gray Herbarium there. She also sent live specimens to botanists and friends.

Psorothamnus thompsoniae Astragalus mollissimus var thompsoniae

Psorothamnus thompsoniae Astragalus mollissimus var thompsoniae

Gray referred Nell's collections to Sereno Watson who identified and mounted them and wrote on the sheets the locality and the collector's name. The archives of the Gray Herbarium contain no additional information about the specimens, such as notes, records, or correspondence The only detailed account of some of Ellen Thompson's collections isfound in a paper byWatson in 1873, entitled "New Plants of Northern Arizona and the Region Adjacent." Watson assigned the specific epithet Thompsonae to two of the fifteen collections attributed to Thompson, PeteriaThompsonae and EriogonumThompsonae, indicating Nell's first collection of the species. In a later paper (1875) he described an additional new species collected by her, AstragalusThompsonae. There are more Thompson collections in the Gray Herbarium, but how many cannot be determined. A catalogue of the vast holdings by donor's name was only begun at the herbarium in 1890, many years after Nell's collections in the 1870s.31

Thompson plant collections are acknowledged in other accounts, such as that of Rothrock on the botany of the Southwest in the Wheeler geographical surveys (1878); and those of Brewer, Watson, and Gray on the botany of California in the Geological Survey of California reports (1880). Eaton (1879) records her collection of the fern Notholaena sinuata in the Arizona/Utah area In the more recent account of the Intermountain flora of the United States by Cronquist et al. (1984-89), we find the following three species attributed to Thompson: Thompson's Dalea {Psorothamnusthompsoniae), Thompson's Penstemon (Penstemonthompsoniae), and Thompson's Woolly Locoweed (Astragalus mollissimus var. thompsoniae) . 32

We can only lament that Thompson did not keep a more complete account of her plant collections. Specimens may well be preserved in other herbaria, but without the scientific names of the species it becomes virtually impossible to locate them In view of the great difficulties under which she worked we are fortunate to have

31 Sereno Watson, American Naturalist 7 (1873)): 299 Also S Watson, "Revision of the Genus Ceanothus, and Descriptions of New Plants," Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 10 (n.s 2, 1875): 333 Changes in the botanical nomenclature used by Watson reflect changes in the taxonomic status of the species since Watson wrote his initial descriptions over a hundred years ago The generous help of Drs Hollis Bedell and Jean Boise Cargill, botanist-archivists at the Gray Herbarium, is gratefully acknowledged

32 J T Rothrock, Reportsupon theBotanical Collections Made in Portions of Nevada, Utah, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona during the years 1871, 1872, 1873, 1874, and 1875, is vol. 6 of the 7-volume report of George M. Wheeler's U.S. Geographical Surveys Westof the One Hundredth Meridian (Washington, D. C : Government Printing Office, 1878); Geological Survey of California, Botany, vol. 1 (by W. H. Brewer and Sereno Watson and Asa Gray), vol 2 (by S Watson) (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1880); Daniel C Eaton, TheFernsofNorth America, vol 1 (Salem, Mass.: S E Cassino, 1879), p 294; Cronquist, Intermountain Flora, vol 3, pt B (1989), pp 32, 144; vol 4 (1984), p 402

130Utah Historical Quarterly

Ellen Powell Thompson131

such observations as she was able to make to add to our historic records.

EPILOGUE

Ellen Thompson made a few brief notes in her diary for ten days in the spring of 1873. She was in the field with her husband once again, north of Kanab in the Panguitch area and traveling along the Sevier River. She continued her botanical work: "Letter from Gray"; "I hunted flowers"; and "Put up cactus roots."

Professor Thompson kept diaries through two more seasons in the field in Utah—1874 and 1875 From his usual very brief notes one can deduce very little about Ellen's life, but it appears that she was with him in the West, although staying in Salt Lake City most of the time. There is no mention of her plant collecting. How long she continued to gather specimens—or if she did—we have no way of knowing.

After the Colorado River expeditions the Thompsons made their permanent residence in Washington, D. C, where members of the Powell family were living and Harry Thompson was employed at the U.S. Geological Survey, founded byJohn Wesley Powell.

In the 1890s Ellen was actively involved with the woman's suffrage movement and became a nationally known suffragette. Letters to her from members of Congress (1896-97, 1901-2) relating to her activities in behalf of this cause are housed with the records of the National American Woman Suffrage Association at the New York Public Library in New York City.

Ellen Powell Thompson's connection with the exploration of the Colorado is commemorated by her plant collections housed in the Gray Herbarium at Harvard University and the several new species that bear her name. In addition, Mount Ellen, at 11,485 feet the highest peak in the Henry Mountains of southeastern Utah, is named after her. And a fragment of the hull of her namesake vessel, the Nellie Powell, all that remains of the three boats that were used in the historic Powell exploration of the Colorado River, is on permanent display in the Visitor Center Museum at Grand Canyon National Park.

33

33 The help of Dr Sara T Stebbins, museum technician at the Visitor Center Museum, Grand Canyon National Park, is gratefully acknowledged A report of another memorial to Ellen Thompson is found in the Daily Pantograph, Bloomington, 111. of July 21, 1957, which states that a white Indian pony that Ellen Thompson rode "on one trip [in the Southwest] is mounted and in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington." According to Frank Greenwell, Department of Mammals and Curator of Exhibits, no such mount is in the Smithsonian at the present time, and no record of its having been there is known

The Swett Homestead, 1909-70

BY ERICG SWEDlN'

NESTLED IN THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF UTAH, high in the Uinta Mountains near Flaming Gorge Dam, is the area of Greendale Though now mostly National Forest with a sprinkling of private homes, seven decades ago this was a homesteading community of at least six families. Oscar and Emma Swettwere among the first homesteaders to arrive and were the last to leave Their homestead is now a visitor site in the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, administered by the U.S. Forest Service. Their story of twentieth-century homesteading Ohio

i^W^fe**^**^^ • .'•-.ft :1

MS***

Dwellings on the Swett homestead, left to right, are: original one-room log cabin, five-room house, two-room log cabin. Unless noted otherwise, all photographs arefrom a U.S. Fewest Service report in the USHS National Registerfiles.

is a doctoral candidate in history at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland,

Mr. Swedin

illustrates the enormous technological changes that have swept this nation during the twentieth century and how people have reacted to those changes.1

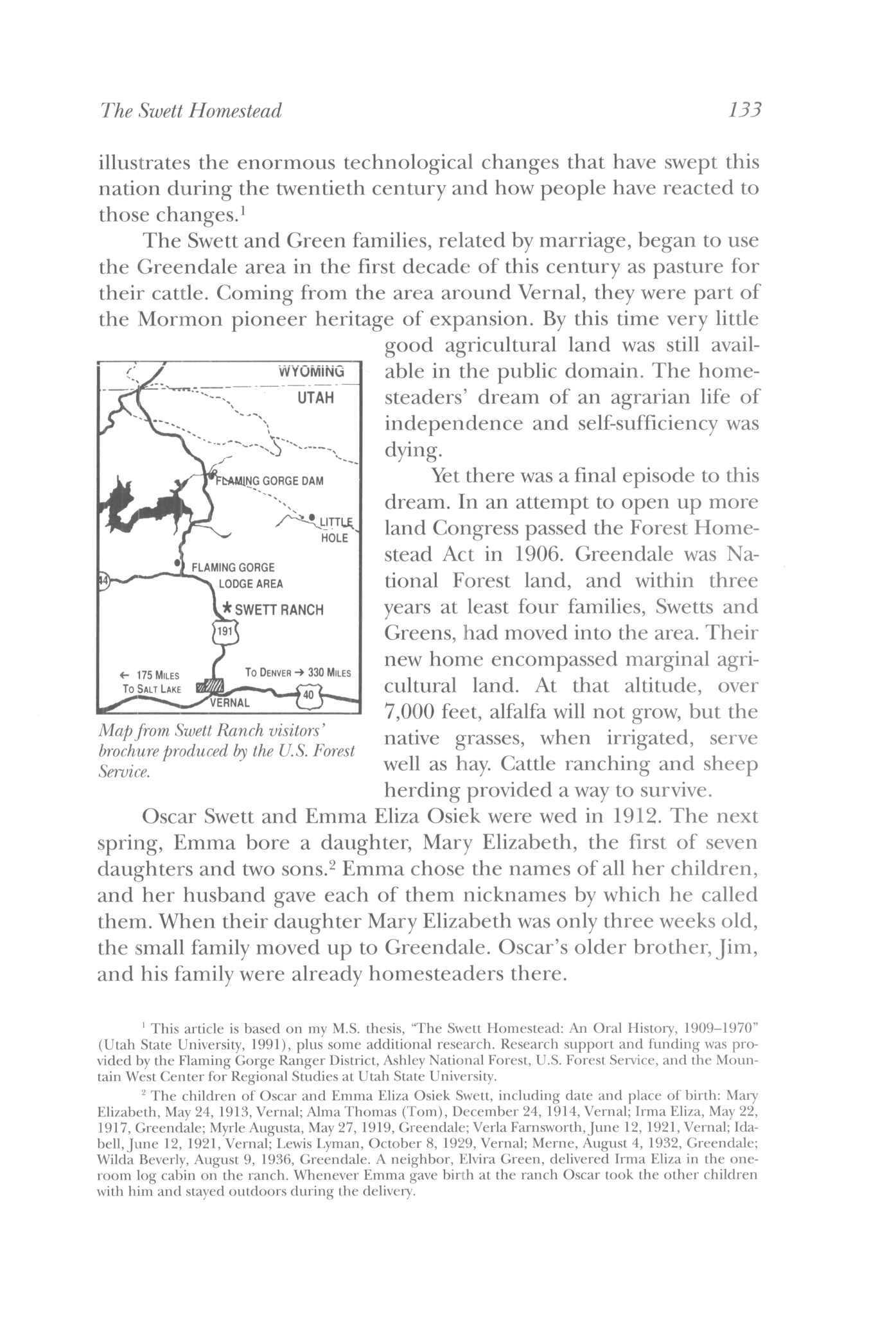

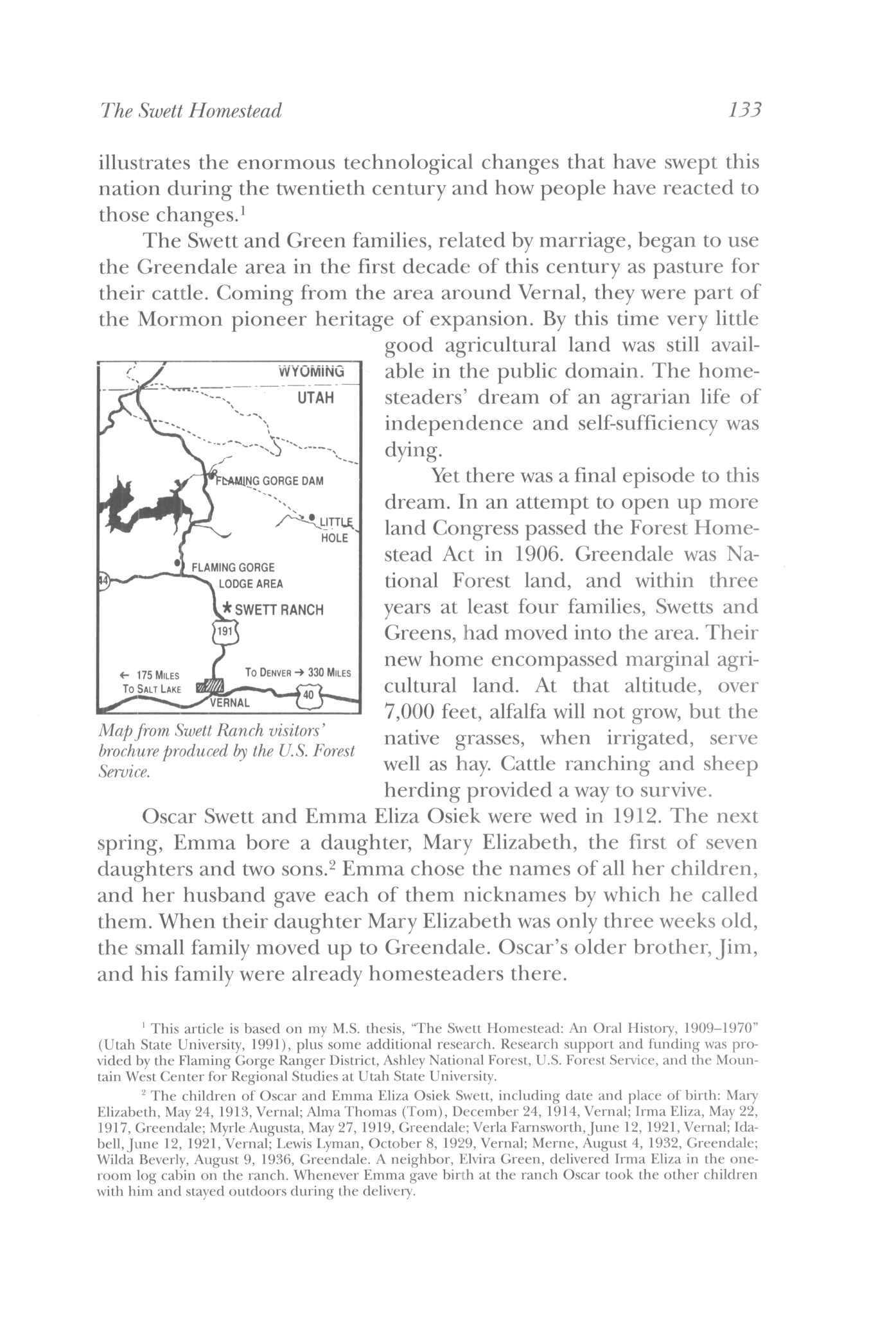

The Swett and Green families, related by marriage, began to use the Greendale area in the first decade of this century as pasture for their cattle Coming from the area around Vernal, they were part of the Mormon pioneer heritage of expansion. By this time very little good agricultural land was still available in the public domain. The homesteaders' dream of an agrarian life of independence and self-sufficiency was dying.

Map from Swett Ranch visitors' brochure produced by the U.S. Forest Service.

Yet there was a final episode to this dream. In an attempt to open up more land Congress passed the Forest Homestead Act in 1906. Greendale was National Forest land, and within three years at least four families, Swetts and Greens, had moved into the area. Their new home encompassed marginal agricultural land. At that altitude, over 7,000 feet, alfalfa will not grow, but the native grasses, when irrigated, serve well as hay. Cattle ranching and sheep herding provided a way to survive.

Oscar Swett and Emma Eliza Osiek were wed in 1912. The next spring, Emma bore a daughter, Mary Elizabeth, the first of seven daughters and two sons. 2 Emma chose the names of all her children, and her husband gave each of them nicknames by which he called them. When their daughter Mary Elizabeth was only three weeks old, the small family moved up to Greendale. Oscar's older brother, Jim, and his family were already homesteaders there

1 This article is based on my M.S thesis, "The Swett Homestead: An Oral History, 1909-1970" (Utah State University, 1991), plus some additional research Research support and funding was provided by the Flaming Gorge Ranger District, Ashley National Forest, U.S Forest Service, and the Mountain West Center for Regional Studies at Utah State University

2 The children of Oscar and Emma Eliza Osiek Swett, including date and place of birth: Mary Elizabeth, May 24, 1913, Vernal; Alma Thomas (Tom), December 24, 1914, Vernal; Irma Eliza, May 22, 1917, Greendale; Myrle Augusta, May 27, 1919, Greendale; Verla Farnsworth, June 12, 1921, Vernal; Idabell, June 12, 1921, Vernal; Lewis Lyman, October 8, 1929, Vernal; Merne, August 4, 1932, Greendale; Wilda Beverly, August 9, 1936, Greendale A neighbor, Elvira Green, delivered Irma Eliza in the oneroom log cabin on the ranch Whenever Emma gave birth at the ranch Oscar took the other children with him and stayed outdoors during the delivery.

The Swett Homestead133 WYOMING

IjTAH

/^Aj-ITTL^

bAMING GORGE DAM

HOLE

Four years earlier, in the summer of 1909, Oscar's mother, Elizabeth Ellen Swett, had filed a claim on 151 acres of land for him since he was not old enough to legally do so for himself. When he reached legal age he filed on additional land next to it, and he and his wife began to fulfill their dream of having a small ranch.

Oscar chose a beautiful spot for their new home, locating it at the north end of their homestead next to an aspen grove and East Allen Creek. The hillsides to the south were covered with Ponderosa pine, while to the north and west they enjoyed a commanding view of the meadow that made up most of their homestead. Beyond, in the distance, one could see all the way to Wyoming

Their first home was an abandoned one-room log cabin located in McKee Draw. Oscar disassembled the cabin, hauled the logs to the homestead, and put it back together. It had originally had a dirt roof, but Oscar replaced that with a wood roof which he shingled.

The Swetts and the other homesteaders altered the landscape to suit their needs by pulling sagebrush from the mountain meadows to create hay fields; by dredging a ditch some fifteen miles long—the Greendale Canal—to bring irrigation water to each of the homesteads; and by turning trees into miles of fence. The local economy was based on cattle. The families ran their herds of cattle on the surrounding National Forest land, using the hay on their homesteads for feed during the winter. In the fall they drove the cattle north to Green River, Wyoming, or south into the Uinta Basin to be sold.

During the first few years Oscar and his young family lived on their homestead only during the summer. Oscar's mother, who also lived up there, taught her new daughter-in-law how to cook the dishes Oscar liked. Daughter Irma described this food, much of it cooked in a small black kettle: "We ate good meals . . . potatoes, gravy and meat, bread and butter, and fruit and vegetables."3 During the winter the Swetts stayed on Oscar's mother's small ranch in Vernal, where Oscar helped his younger brothers with the chores. Those first years were rough as the Swetts labored to improve their homestead. They did not have a lot of money, but there were neighbors and relatives nearby to help. Emma did much of the work, pulling up sagebrush by hand while her young children followed her

134Utah Historical Quarterly

3 Interview with Irma Eliza Swett Toone, Vernal, September 15, 1989, p 4 Copies of all the interviews cited herein are available in Special Collections, Merrill Library, USU, and the Flaming Gorge Ranger District office of the U.S Forest Service in Dutch John, Utah Interviews were conducted by the author unless credited otherwise

and made a game out of piling up the sagebrush into stacks for burning. It took them about twenty years to finally clear all the fields on their homestead. Emma also "took care of the milk cow, pigs, chickens and other chores as well as washed clothes, cooked, kept house, canned, gardened, and sewed. The children helped as they became big enough."4 When her husband needed assistance Emma helped, and when he was gone she did his chores. During the summer the fields had to be irrigated, so "even while nursing a baby, she would walk to the far fields to change the water, walk home to feed a baby, then head for the fields again."5 In addition to making their clothes, Emma even repaired her children's shoes with her own cobbler equipment

The Swetts present an interesting case study of self-sufficiency and interdependence with the larger economy. Although they made their own clothing, they bought the cloth in Manila or Vernal. Emma had her own garden and bottled incessantly, both fruit and meat, putting up somewhere between five hundred and a thousand quart

5 Ibid

The Swett Homestead135

Emma and Oscar Swett and their nine children at a 1944 reunion. A family photograph in the Ashley National Forest files.

4 Phil Johnson, "A Brief History of the Oscar Swett Homestead: Daggett County, Utah" (Forest Service study, November 1971, Swett Ranch file, Flaming Gorge Ranger District, Dutch John), p 7