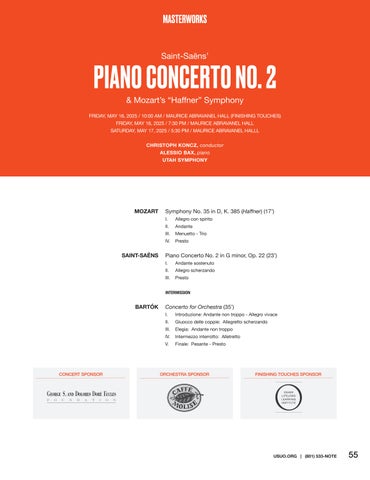

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2

CIRQUE CINEMA

& Mozart’s “Haffner” Symphony

FRIDAY, MAY 16, 2025 / 10:00 AM / MAURICE ABRAVANEL HALL (FINISHING TOUCHES)

CONCERT SPONSOR

FRIDAY, MAY 16, 2025 / 7:30 PM / MAURICE ABRAVANEL HALL

Featuring Troupe Vertigo

SATURDAY, MAY 17, 2025 / 5:30 PM / MAURICE ABRAVANEL HALLL

JULY 31 / 2024 / 8 PM

CHRISTOPH KONCZ , conductor

COSETTE JUSTO VALDÉS , conductor

MOZART

ALESSIO BAX , piano

SAINT-SAËNS

BARTÓK

JESSICA DANZ , horn

UTAH SYMPHONY

Symphony No. 35 in D, K. 385 (Haffner) (17’)

I. Allegro con spirito

II. Andante

III. Menuetto - Trio

IV. Presto

Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 22 (23’)

I. Andante sostenuto

II. Allegro scherzando

III. Presto

INTERMISSION

Concerto for Orchestra (35’)

I. Introduzione: Andante non troppo - Allegro vivace

II. Giuocco delle coppie: Allegretto scherzando

III. Elegia: Andante non troppo

IV. Intermezzo interrotto: Alletretto

V. Finale: Pesante - Presto

ORCHESTRA SPONSOR

FINISHING TOUCHES SPONSOR

Christoph Koncz Conductor

Austrian conductor Christoph Koncz is highly acclaimed, and this season marks his second as Music Director of Orchestre Symphonique de Mulhouse, while he continues his tenure as Principal Conductor of Deutsche Kammerakademie Neuss am Rhein. His highlights thus far have included collaborations with Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Dresden Staatskapelle, Orchestre de Paris, Mahler Chamber Orchestra, hr-Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt, London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. This upcoming season, he returns to the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and the Orchestre Métropolitain de Montréal. He will also conduct the Symfonieorkest Vlaanderen with Johannes Moser, Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano, and make his debut with Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. He is passionate about expanding the classical music repertoire, often championing works by lesser-known composers.

Combining exceptional lyricism and insight with consummate technique, Alessio Bax is without a doubt “among the most remarkable young pianists now before the public” (Gramophone). He catapulted to prominence with First Prize wins at both the 2000 Leeds International Piano Competition and the 1997 Hamamatsu International Piano Competition and is now a familiar face on five continents as a recitalist, chamber musician, and concerto soloist. He has appeared with over 150 orchestras, including the New York, London, Royal, and St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestras, the Boston, Baltimore, Dallas, Cincinnati, Seattle, Sydney, and City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestras, and the Tokyo and NHK Symphony in Japan, collaborating with such eminent conductors as Marin Alsop, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Sir Andrew Davis, Hannu Lintu, Fabio Luisi, Sir Simon Rattle, Ruth Reinhardt, Yuri Temirkanov, and Jaap van Zweden.

By Jeff Counts

Symphony No. 35 in D Major, K. 385 (“Haffner”)

Duration: 17 minutes in four movements.

THE

COMPOSER

– WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

(1756–1791) – Mozart’s departure from Salzburg in the early 1780s created a troubling rift with his father, one young Wolfgang was too busy to mitigate with more than some alternately deferential and frustrated letters. Wolfgang’s squabbles with his employers had led to his firing in 1781, a situation he might have enjoyed more if it hadn’t made his father so anxious and angry. A dutiful and sometimes practical son, Wolfgang wanted to be back in Leopold’s good graces, if only to deflect his intense scrutiny. But with the huge success of The Abduction from the Seraglio, other pressing commissions and an impending wedding to Constanze, the composer was burning the candle even more quickly than usual.

THE HISTORY – Mozart Sr. broke the ice a bit in 1782 with word of a request from home for a celebratory composition. Salzburg’s Mayor Sigmund Haffner was to be granted nobility, and he wanted new music by his city’s favorite son to be performed at the ceremony. Though overwhelmed by his numerous existing commitments, Mozart agreed to take on the project, due in no small part to the prospect of detente with his father. The turn-around time was quick, but Mozart promised to work as briskly as possible without allowing haste to affect the result. He kept his word, but just barely. It took him up to the last moment to complete the score and the music he sent home to honor Haffner was not the symphony we know today. In fact, it wasn’t a symphony at all. The Serenade (as it was originally constructed) was performed that August and Mozart didn’t give it much thought again until the following February. With an impending Vienna concert series set to feature his own works, Mozart was in need of a new symphony. Like so many of his projects during this period, it would have to be done quickly, so he wrote to his father and asked that the Serenade score be returned in hopes that he might renovate it for the purpose. This the composer did with relative ease (by removing two of the original movements and expanding the orchestra) and great success, though once again he had to work with supernatural speed since Leopold took his huffily sweet time sending the materials to Vienna. No harm done, in the end. Or at least no new harm. For all the thorny familial tiptoeing and compressed timelines, the dazzling “Haffner” Symphony bears no scars. Mozart himself was quite pleased with the piece, and a little surprised by it. “My new Haffner symphony has positively amazed me,” he

wrote to Papa, “for I had forgotten every single note of it.”

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1783, the American Revolutionary War ended with the Treaty of Paris, the country of Georgia became a protectorate of Russia and The Great Meteor cut its historic path across the Northern European sky.

THE CONNECTION – The “Haffner” Symphony was most recently performed by Utah Symphony in 2016. Rei Hotoda conducted.

Concerto No. 2 in G Minor for Piano and Orchestra, op. 22

Duration: 23 minutes in three movements.

THE COMPOSER – CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) – Life was proceeding nicely for Saint-Saëns in the 1860s. He was comfortable financially and enjoyed a position of prominence in the artistic circles of Paris thanks to his handful of prize-winning compositions and widely respected skills as a pianist and organist. Saint-Saëns also held a teaching position at the Ecole Niedermeyer (he replaced the school’s namesake in 1861) and was reportedly a great source of intellectual inspiration for his students. In fact, those who knew him much later in his life might have been surprised to learn that he often courted scorn at work by exposing his pupils to the “modern” excesses of Liszt and Wagner.

THE HISTORY – Russian pianist Anton Rubenstein was performing on a series of concerto concerts in Paris in 1868 (under the baton of Saint-Saëns) when he mentioned a desire to reverse roles and conduct a program with Saint-Saëns as soloist. The novel idea of changing stage positions was very appealing to the Frenchman, and it offered a “two birds one stone” opportunity. The hall was not available again for a few weeks, so Saint-Saëns seized the chance to suggest the composition of a new work. Rubenstein was game, so Saint-Saëns hurriedly put together the 2nd Concerto. The premiere did not go very well, partly because Saint-Saëns had not budgeted much time for practice in his rush to complete the score but also due to unpredictable swings of mood in the music that left the audience a bit baffled. One famous critical quote from the evening came from fellow pianist and composer Sigmond Stojowski, who claimed that the

concerto “began with Bach and ended with Offenbach.” A pithy remark to be sure, intended to call out something inconsistent about the music, but perhaps not such a damning indictment on closer inspection. There is a Bach-like atmosphere as the work opens and there is an abrupt shift of temperament into the scherzo, but it feels more like the other side of the same coin than any crime of disconnection. The fleet and frantic finale only serves to confirm a certain delightful totality despite the concerto’s quick-change antics. Saint-Saëns was never shy in his opinions, and he would become quite the conservative killjoy in his later years, when music by Debussy and Stravinsky regularly ruffled his traditionalist feathers. In 1868, however, he was still the good-spirited man of the hour, his hour, and the 2nd Concerto reflects his active and effortlessly witty mind. It remains one of his most popular works and is certainly the most adored of his five concertos. Saint-Saëns loved it too and continued to perform it throughout his long life on stage.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1868, Liechtenstein disbanded her army and declared permanent neutrality, Siam’s King Rama IV died, Cuba’s ten-year war with Spain began and Fyodor Dostoyevsky published The Idiot

THE CONNECTION – The 2nd Concerto of Saint-Saëns was performed most recently by the Utah Symphony in 2017. Thierry Fischer was on the podium and Louis Lortie was soloist.

Concerto for Orchestra

Duration: 35 minutes in five movements.

THE COMPOSER – BELA BARTOK (1881-1945) – With the situation in Europe worsening by the day, Béla Bartók sent many of his most important scores abroad and then reluctantly emigrated to the United States in 1940. As an outspoken critic of fascism, the freedom in his perceived circle of safety had disappeared as Hungary’s nationalistic government attempted to silence him. Once settled in New York, Bartok began to suffer the first symptoms of his long undiagnosed leukemia that would take him so quickly. He was never fully at home in America (he felt just as underappreciated there as he had in Hungary), but it would

be here that he received the 1943 commission that would forever define his place as a 20th century orchestral titan.

THE HISTORY – The new work, a Concerto for Orchestra (commissioned by Serge Koussevitsky in memory of his recently deceased wife Nathalie), premiered in Boston the following season and would become Bartók’s most popular and important masterpiece. Sadly, it was one of the last pieces he would complete before succumbing to his illness in 1945. In the end, it was a monument not just to Nathalie Koussevitsy, but to himself, and it is a pity Bartók never experienced the Concerto’s ascendance to the first rank of 20th century compositions. He didn’t necessarily break new ground with his version of the non-symphony since Hindemith and Kodaly had each already written a Concerto for Orchestra in the previous two decades. It was Bartók, however, who brought a level of perfection to the form and whose masterwork still serves as its finest example. The piece is structured as a large palindrome and Bartók himself often spoke to his Concerto’s “tendency to treat the single instruments and instrument groups” in a “soloistic manner.” Indeed, the writing is highly virtuosic, and every section of orchestra is featured expertly at a time when American orchestral talent was burgeoning under the leadership of many imposing European maestros. “The general mood of the work represents,” he wrote in a brief program note for the premiere, “apart from the jesting second movement, a gradual transition from the sternness of the first movement and the lugubrious death-song of the third, to the life-assertion of the last one…” With all the Bartók hallmarks on display – the depthless well of melodic ingenuity, the rhythmic vitality, the formal creativity, the scathing wit (refer here to the “jesting” Bartok mentions in his note and the Shostakovich parody that “interrupts” the Intermezzo movement) – this is the work of a genius who was in total, effortless possession of his skills. Not one note is out of place.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1944, Mount Vesuvius erupted, the “Great Escape” from Stalag Luft III occured, the United Negro College Fund was founded in America and Iceland’s issued its final declaration of independence from Denmark.

THE CONNECTION – The Concerto for Orchestra has been a favorite of Music Directors and Guest Conductors alike at Abravanel Hall. Maestro Ilan Volkov conducted it most recently in 2014.