Safety and Health Management Planning

For Veterinarians

Safety and Health Program

College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences

Utah State University

Program Developers

Jessie Salter, DVM, MPH Candidate

Michael L. Pate, Ph.D.

Kerry A. Rood, MS, DVM, MPH, DACVPM

Program Reviewer

Dennis Murphy, Ph.D., Nationwide Insurance Professor Emeritus of Agricultural Safety and Health

Acknowledgment

This is supported by the High Plains Intermountain Center for Agricultural Health and Safety CDC/NIOSH Grant No. U54OH008085. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC/NIOSH.

Contents Unit 1. Establishing a Safety Culture ..................................................................... 1 Unit 2. Safety Leadership Styles .............................................................................. 4 Unit 3. Hazard Identification ..................................................................................... 8 Unit 4. Risk Assessment 12 Unit 5. Preventing and Controlling Risks ......................................................... 21 Unit 6. Involving Employees .................................................................................... 25 Unit 7. Program Evaluation ..................................................................................... 28 Appendix A: Hazard Identification 34 Appendix B: Job Safety Analysis ............................................................................ 35 Appendix C: Risk Assessment ................................................................................. 37 Appendix D: Haddon Matrix .................................................................................... 38 References 40

Figures and Tables Figure 1: Transactional Leadership Model ............................................................ 5 Figure 2: Characteristics of Transformational Leadership ........................ 6 Table 1: Catheter Placement Analysis ..................................................................... 10 Table 2: Thoracic Radiographs Analysis 11 Table 3: Risk Ranking and Severity ........................................................................... 14 Table 4: Example Risk and Ranking Severity ..................................................... 15 Figure 3: Hand Injury From Scenario #1 ................................................................ 16 Figure 4: Haddon Matrix 22 Figure 5: Bull Breeding Soundness Exam Haddon Matrix ....................... 23 Figure 6: Hierarchy of Control ....................................................................................... 24 Figure 7: Examples of Safety Culture and Evaluation Statements ..... 30

Unit 1.

Establishing a Safety Culture

1 | Unit 1

Unit 1.

Establishing a Safety Culture

Veterinary staff health and safety are of primary importance to the profession. Although this is inherently understood, oftentimes, staff safety is not given the time and resources needed to promote a safe work environment free from unnecessary risks or exposures. This handbook educates clinic leaders on valuing and creating a safety culture in practice as well as implementing appropriate safety policies and procedures.

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (2018), 12% of veterinary service professionals experienced a work-related injury in 2016. The association also reports that there are three deaths per year in veterinary medicine. Veterinary personnel are more likely to experience a work-related injury than policemen, firefighters, and construction workers. These statistics illustrate the need for a stronger safety culture in veterinary medicine.

This handbook provides an outline on how to establish a safety culture and be proactive in veterinary clinics through evidence-based safety and health practices.

Safety Culture

Safety culture can be defined as “the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behavior that determine the characteristics of the organization’s health and safety management.” 1 In other words, a safety culture is a clinic’s and/or staff member’s attitude toward safety and how safety issues are managed. Broadly, a positive safety culture equates to less incidents at work and fewer missed work days. It also implies better animal care and outcomes.

It is important to remember that safety culture will look different in each individual practice. Taking the time to consider how safety and associated training should look in your clinic is a valuable exercise that should be given ample time and thought.

Reflection Questions

• How does your staff currently respond to safety training? Is this response different from what you want?

• Do staff members practice safe working habits? Are there certain areas that need improvement?

2 | Unit 1

• How can you get the best response to improve safety from your staff?

The answers to these reflection questions will be different for every clinic, so find what works for you!

A model can help you undestand how different aspects of workplace safety culture can be influenced.

Socioecological Model

The socioecological model describes the interactions that people encounter every day. There are five basic factors that affect behavior within the model:

1. INTRApersonal/individual factors influence behavior through personal knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and individual personalities.

2. INTERpersonal factors, or interactions with other people, can provide support or create barriers related to beliefs, attitudes, and actions.

3. Institutional/organizational factors, which includes the rules, regulations, and policies that can promote/inhibit beliefs, attitudes, and actions.

4. Community factors, like social norms that influence individual behavior and actions.

5. Public policy factors, including local, state, and federal policies/laws that influence choices.

Understanding that all levels of the model can impact how a person views safety is critical to affecting staff attitudes and behaviors toward safety. The model also plays a large role in creating a safety culture within your practice. Veterinarians are often the leaders in the practice, even if they do not have a managerial role. It is very important to realize that veterinarians can make or break how a clinic thinks about safety. Encouraging veterinarians to be good examples that put their safety and their staff’s safety first can help promote a positive safety culture.

Ideas for leveraging the socioecological model to promote workplace safety include:

1. Trusted veterinarians lead safety trainings and explain why safety is important.

2. “Safety officers” encourage other staff members to follow safety protocols.

3. Ensure written safety policies are easily available and that each new employee receives a copy of the protocols to review before beginning work.

4. Create relationships built on trust with staff and clients.

3 | Unit 1

Unit 2.

Safety Leadership Styles

4 | Unit 2

Unit 2.

Safety Leadership Styles

Two main types of business leadership are transactional and transformational. Both forms can promote changes in safety attitudes and behaviors within a clinic, but one seems to create more lasting change. As we discuss each leadership style, consider which one you think your staff will be more responsive to and which one can promote long-term improvements in safety culture in your clinic.

Transactional Leadership

This form of leadership is what most people think of for a corporate-type structure. Transactional leadership relies on exchanging rewards for work or loyalty to the company (Figure 1). A clear chain of command typically correlates to what many consider “management.” The motivation for staff to complete a task or change behavior is based on rewards or penalties.

Transactional Leadership

Adapted from Northhouse (2016).

Consider a simple example: Every time a staff member gets acknowledged for exhibiting or complying with a safety practice, their name goes into a drawing for a gift card or bonus on their next paycheck. This reward encourages staff members to wear name tags and provide excellent customer service while interacting with clients.

5 | Unit 2

Figure 1. Transactional Leadership Model

Practical Short-term Reward Performance Corporate Structure Less Flexible External Motivation

Transformational Leadership

This form of leadership leans more toward a partnership. The leader engages with followers, motivating them to move past individual interests and pushes toward a collective purpose instead (Figure 2). This leadership style focuses on higherorder needs (like the need to learn or leave a legacy). Transformational leadership engenders trust, admiration, loyalty, and respect.

Creating an enduring organization

Leading with integrity

Envisioning a new future

Communicating persistently

Transformational Leadership

Meaningful changes in strategy and organization

Empowering employees

Adapted from Northhouse (2016).

Modeling desired behaviors

6 | Unit 2

Figure 2. Characteristics of Transformational Leadership

An example of how transformational leadership might be used in a clinic setting follows:

As the chief of staff at your clinic, you’re noticing some laxity around wearing protective lead aprons and thyroid guards when staff are taking radiographs. You decide to pull your head technician aside and discuss staff members’ attitudes toward radiation safety. Your head technician states that some of the doctors and more experienced technicians aren’t wearing the appropriate protective equipment while radiographing. You ask her how the situation might be remedied. She replies that the doctors need to be better examples. Together you have a meeting with all doctors to reiterate the importance of radiation safety and explain that staff members are following their doctors’ leads and not always practicing safe radiation protocols. Your doctors agree to be more aware of their attitudes toward radiation safety and be good examples by wearing lead during radiographs. After the meeting, you discuss monitoring who is wearing or not wearing aprons and thyroid shields and plan to follow up in one month.

Reflection Questions

• With the above information about transactional and transformational leadership in mind, which style do you feel will have more impact on your clinic?

• Why?

• How might you implement this leadership style more fully in your clinic?

7 | Unit 2

Unit 3.

Hazard Identification

8 | Unit 3

Unit 3.

Hazard Identification

A hazard is considered anything that can potentially cause harm. It can be associated with an activity that can result in injury or illness if not managed appropriately. Identifying and controlling hazards are the first steps to improving clinic safety. There are many hazards associated with veterinary medicine. Most hazards can be placed into one of four categories: physical, biological, chemical, or psychological.

Match the following hazards or practices with their associated hazard category (also available in Appendix A).

________ 1. Poor animal handling techniques

________ 2. Poor knowledge of animal body language/behaviors

________ 3. Poor hand hygiene

________ 4. Improperly maintained anesthetic equipment

________ 5. Overbooking

________ 6. Understaffing

________ 7. Animal bites/scratches

________ 8. Zoonotic diseases

________ 9. Not wearing a mask during dental prophylaxis

________ 10. Destructive criticism

________ 11. Mixing cleaning products

________ 12. Topical parasiticides

________ 13. Fatigue

________ 14. Burnout

________ 15. Gossiping

________ 16. Eating/drinking in treatment areas

________ 17. Heat

________ 18. Noise

________

________

Poor communication skills

A. Physical

B. Biological

C. Chemical

D. Psychological

9 | Unit 3

19.

20.

9

Key for Hazard Identification 1. A or D 2. A or D 3. A, B, or C 4. C 5. D 6. D 7. A or B 8. B 9. B 10. D 11. C 12. C 13. A or D 14. D 15. D 16. B 17. A 18. A 19. D 20. A

Faulty head catch

Now that we can categorize hazards, how do we identify them? Here are a few questions to think about for any given situation that will help you see the potential hazards associated with the task:

• What can go wrong?

• What are the consequences?

• How could hazards arise in this situation?

• Are there other contributing factors?

• How likely is it that the hazard will occur?2

Simply stated, identifying hazards and evaluating their likelihood of occurring and how much damage they may cause in any given situation is an essential tool to create a positive safety culture.

Job Safety Analysis

Job safety analysis is selecting a task or job that needs to be conducted and breaking it down into individual steps to evaluate hazards at each step. Next, ways to eliminate or reduce those hazards are identified.

Tables 1 and 2 provide two examples of a job safety analysis. Appendix B provides a job safety analysis template that you can use with your clinic.

Basic job steps

Potential hazards

Restrain pet. Pet could bite/scratch handler or tech placing catheter.

Recommended action or procedure

Watch for pet behavior signs of nervousness, stress, and aggressiveness. Have enough techs to restrain pet to ensure handler safety. Muzzle as appropriate.

Place catheter. Catheter stylet could stick handler.

Perform catheter aftercare. Pet could remove catheter and cause hemorrhage or eat catheter, resulting in foreign body.

Have enough techs to restrain pet safely. If unable to restrain safely, consider sedation prior to placement.

Use a catheter guard, e-collar, and/or bitter spray to deter pet from chewing on catheter.

10 | Unit 3

Table 1. Catheter Placement Analysis

Unit 3

Basic job steps

Test radiograph setup.

Potential hazards

Handler could be exposed to radiation.

Measure pet. Pet could bite/scratch handler.

Recommended action or procedure

Wear lead apron, thyroid shield, and gloves or step out of machine’s range.

Watch for pet behavior signs of nervousness, stress, and aggressiveness. Use adequate techs to restrain.

Muzzle when needed.

Place pet on/off radiograph table. Handler could receive a back injury or bite/ scratch from pet.

Radiograph pet. Handler could be exposed to radiation.

Lift with legs, not back. Muzzle when appropriate.

Use adequate techs to lift pet and restrain.

Wear lead apron, thyroid shield, and gloves or step out of machine’s. Set machine for correct size of pet.

11 | Unit 3

Table 2. Thoracic Radiographs Analysis

Unit 3

Unit 4. Risk Assessment

12 | Unit 4

Unit 4.

Risk Assessment

Risk is measuring the combined probability and severity of possible harm from a particular hazard. There are multiple ways to rank risks. For example:

• Catastrophic – imminent danger, one or more deaths, widespread illness, loss of facilities or equipment.

• Critical – severe injury, serious illness, property and/or equipment damage (amputations, fractures, long-term or permanent impairment, temporary loss of property/equipment).

• Marginal – less serious injury, illness, or property damage (sutures, deep bruising, strains, short-term disability, short-term loss of equipment).

• Negligible – first aid cases, easy/quick repair of equipment/property.3 These rankings should also be categorized with the likelihood of the risk occurring. For example, risk can be:

• Frequent – likely/probable to occur almost daily.

• Probable – likely/probable to occur several times in a given time period (week/ month).

• Occasional – likely/probable to occur sometime in a period (year).

• Remote – not likely to occur, but it is possible (years).

• Improbable – possible, but the probability of occurrence is close to zero.3

A risk can be catastrophic but also probable and would thus require minimal mitigation strategies or time/effort to prevent its occurrence. A useful way to look at risk ranking and severity is to create a table that lists the two together (Tables 3 and 4; Appendix C).

13 | Unit 4

Frequency

Table 3. Risk Ranking and Severity

Catastrophic

Death, permanent disability

Consequence

Critical Disability >3 months

Marginal Minor, lost work time

Negligible First aid, minor treatment

Frequent Likely to occur; repeated High High Serious Medium

Probable Likely to occur several times High High Serious Medium

High risk – stop/shut down now

Serious risk – high priority to correct

Medium risk – correct soon

Low risk – correct as needed or leave as is

(Adapted from Steel and Murphy, n.d.)

14 | Unit 4

Occasional Likely to occur sometime High Serious Medium Low Remote Not likely to occur Serious Medium Medium Low

Medium

Improbable Very unlikely

Low Low Low

| Unit 4

Frequency

Frequent

Catastrophic Death, permanent disability

Consequence

Critical Disability >3 months

Marginal Minor, lost work time

Negligible First aid, minor treatment

Likely to occur; repeated Dog bites Cat scratches Needle sticks

Probable Likely to occur several times

Occasional

Likely to occur sometime

Remote

Not likely to occur

Improbable

Very unlikely

Horse strikes, vehicular accidents

Horse kicks, zoonotic diseases

Sprain/strain from lifting animals

Crushing injuries, vector-borne diseases

Lightning strikes Client falls Inclement weather

Earthquake

Identifying how likely a risk is to occur in conjunction with its severity will help determine the order in which risks should be addressed and what risks are the most important in your clinic setting.

Putting It Into Practice

Consider the following scenarios.

Scenario #1

“Timber,” an aggressive 85-pound Malamute dog presents to your clinic for evaluation of a hurt paw. Your technician immediately places him with his owner in an examination room and collects a history for you. You’ve seen Timber for annual vaccinations before and have never had any issues with him. You begin your examination with a temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate (TPR), and Timber

15 | Unit 4

Table 4. Example Risk and Ranking Severity

lets you get all your parameters, even a rectal temperature, without complaint. Timber’s right front paw is swollen and he won’t let you manipulate it. He becomes agitated. You discuss some options with the owner.

What options could you give the owner that might mitigate the hazard risk to Timber, the client, and your safety in this situation?

Based on your discussion with the owner, you decide to sedate Timber for a more thorough examination of his paw. Once Timber is in the treatment area, you are unable to hold him safely for IV administration of sedation medication. You opt to give him an IM injection instead. Once the medication has been administered, Timber begins to fall asleep, but every time you try to move him, he wakes up and starts acting aggressively. You try to place a muzzle over his mouth so you can finish your exam. Figure 3 shows the end result.

Reflection Questions

• Were there any good safety plans in place for this situation?

• What other precautions could have been implemented?

• What is your clinic’s policy on aggressive animals?

16 | Unit 4

16 Unit 4

Figure 3. Hand Injury From Scenario #1

Scenario #2

In mid-November, a veterinarian is scheduled to examine 80 cows for pregnancy on the rancher’s property. A snowstorm is forecasted at about the same time the vet plans to return to the clinic. The vet loads up the truck and takes a technician to help with records.

The two arrive at the ranch without any complications. There is snow on the ground, and the cows haven’t been corralled yet. They are currently running around the field while the rancher and two of his children try to move them into the pen attached to the chute. Once the cows are penned, the rancher pushes the first cow into the chute. When the cow hits the head catch, the back of the chute lifts off the ground. The second cow in line is held back by someone holding a piece of plywood, forming a “pregnancy test box” for the vet to stand in while preg checking.

Reflection Questions

• What do you see happening to the vet performing the preg checks? How safe would you feel with an impaired chute and a plywood sheet between you and a cow?

• What safety issues (obvious and maybe not so obvious) do you note in this situation?

• How could these safety issues be reduced or eliminated?

• How could you communicate your safety concerns with the rancher to produce changes that protect you as well as the rancher and his family?

17 | Unit 4

Scenario #3

You’ve just returned from lunch after a long morning of surgery. Your first appointment is an adverse drug reaction (ADR) dog, “Murphy,” that went hiking with his owner last week. He has had some vomiting and is inappetent and lethargic. Murphy is not up-to-date on his vaccinations.

Your technician discovers that Murphy also has polyuria (PU)/polydipsia (PD) and seems dehydrated on skin turgor. You decide to run a complete blood count (CBC) and chemistry panel, which reveal dehydration, azotemia, and elevated liver enzymes. You decide to hospitalize Murphy for IV fluids and 24-hour care.

Reflection Questions

• What’s on your differential diagnosis list? Do any of the differentials pose a safety concern for you, your staff, or the client?

• Because of Murphy’s history, you suspect leptospirosis infection and send out a titer. What needs to be addressed while waiting for his results?

• How do you plan to keep yourself and your staff safe? What are your recommendations for the client?

• What strategies might help reduce or eliminate this and other zoonotic disease hazards in the future?

18 | Unit 4

Scenario #4

You work at a small animal practice and your first appointment for the day is a 2-year-old German shepherd dog (GSD) named “Maggie.” She needs a wellness exam and vaccinations. Your technician heads into the room and you immediately hear barking and growling while the owner yells at Maggie to settle down. Your technician comes out of the room with that look on her face. She tells you Maggie has already bitten the owner.

Reflection Questions

• How do you address the hazards present in this scenario? Does your clinic have a protocol in place for aggressive animals? (If not, now is a great time to create one!)

• The owner has already been bitten. How do you keep the owner safe in future situations like this?

• What other protocols can you put into place to minimize the effects on staff and clients when handling aggressive patients?

19 | Unit 4

Scenario #5

You’re on your way to an equine castration at Reginald Cooper’s place. The patient is a 3-year-old quarter horse, “Amos.” You pull into the yard and immediately notice a horse running through the pasture away from the owner. You jump out of the truck and Mr. Cooper tells you Amos is halter broke, but they just haven’t had the time to mess with him much. You manage to help Mr. Cooper halter Amos and lead him to a small, muddy paddock. As you’re drawing up sedation for the procedure, Amos strikes at Mr. Cooper.

Reflection Questions

• What safety hazards do you see in this situation?

• How will you mitigate them?

This is an excellent example of why all staff members need to be included in developing a positive safety culture. Proper training of front staff may have helped decrease the stress and risk associated with this situation. Teaching anyone who answers the phone to ask probing questions about the given situation can help mitigate hazards and risks associated with these conditions and improve positive safety culture within the clinic.

20 | Unit 4

Unit 5.

Preventing and Controlling Risks

21 | Unit 5

Unit 5.

Preventing and Controlling Risks

Once hazards have been identified, the next step is knowing what to do about them. Mitigation is having a plan in place that will ensure all staff, clients, and patients will be safe in that situation before the hazard arises. One tool used to assess hazards and risks is called the Haddon Matrix (Figures 4 and 5; Appendix D).3 The matrix has nine areas of potential prevention or control of hazards and risks.

Phases

Pre-event

Event

Post-event

Factors

People Agent/vehicle

Physical environment

Social environment

Adapted from Barnett et al. (2005).

The goal of the Haddon Matrix is to identify possible areas of control or prevention regarding any given hazard in a clinic setting. Another underlying concept of the Haddon Matrix is realizing that incidents are not typically caused by any one behavior or choice; it is typically a combination of decisions or behaviors that place someone at higher risk.

22 | Unit 5

Figure 4. Haddon Matrix

Consider bull breeding soundness exams and how we can fill in the Haddon Matrix (Figure 5).

Phases

Pre-event

Factors

People Products

Provide training on cattle handling procedures.

Event

Post-event

Ensure staff use equipment safely/ effectively.

Test chute hydraulics prior to cattle arriving.

Test that chute is operating correctly.

Physical environment

Know where exits are; know where equipment/ cords are in relation to work area.

Exits are not blocked; locate equipment/ cords in areas to minimize trips/falls.

Social environment

Safety Policy is clearly articulated and reinforced with staff

Reporting encouraged to notify leadership for safety improvements

Provide first aid training and client education.

Clean and maintain chute for proper functioning.

Maintain fencing/ corrals; modify loading/ unloading areas if safety concerns present consistently.

Well established protocol to support transition back to work

Using a Haddon Matrix illustrates the various ways to implement prevention and control. When using the matrix, also consider what prevention strategies will be most accepted or helpful. Sometimes the most practical solution will not work because of staff push back or other reasons. Passive prevention is much more readily accepted than active prevention in most situations. Be sure to look beyond what is considered the risk to solutions that might seem less obvious or that circumvent that actual risk.

23 | Unit 5

Figure 5. Bull Breeding Soundness Exam Haddon Matrix

For example, an obvious and practical solution to decrease head-on vehicle collisions is for drivers to pay attention to the road and stay on the correct side while driving. This solution seems intuitive but requires drivers to actively pay attention while driving (which doesn’t occur consistently due to cell phones, crying children, etc.). The passive solution to decrease the head-on collision risk is typically divided highways or barriers to prevent cars from crossing into traffic.

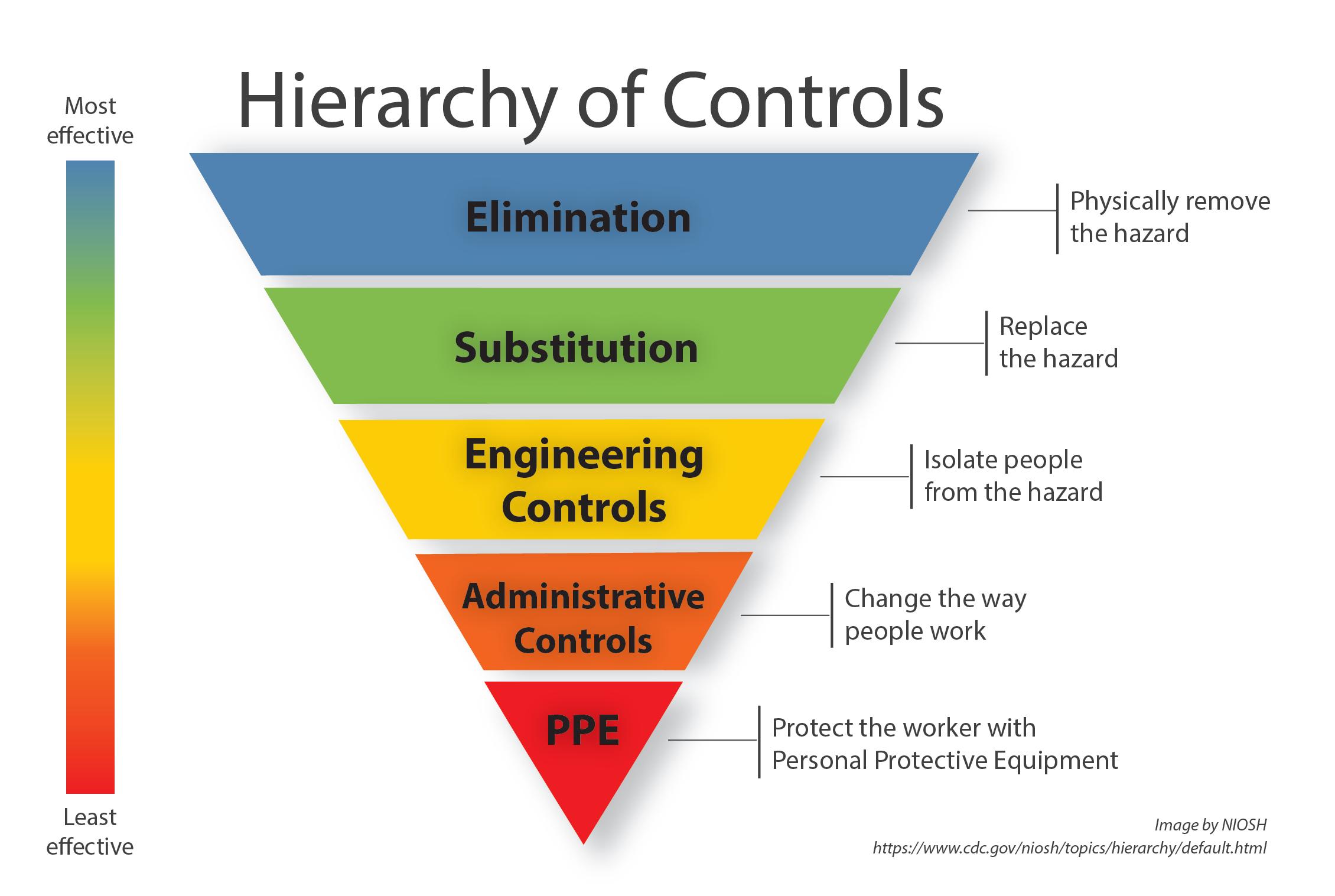

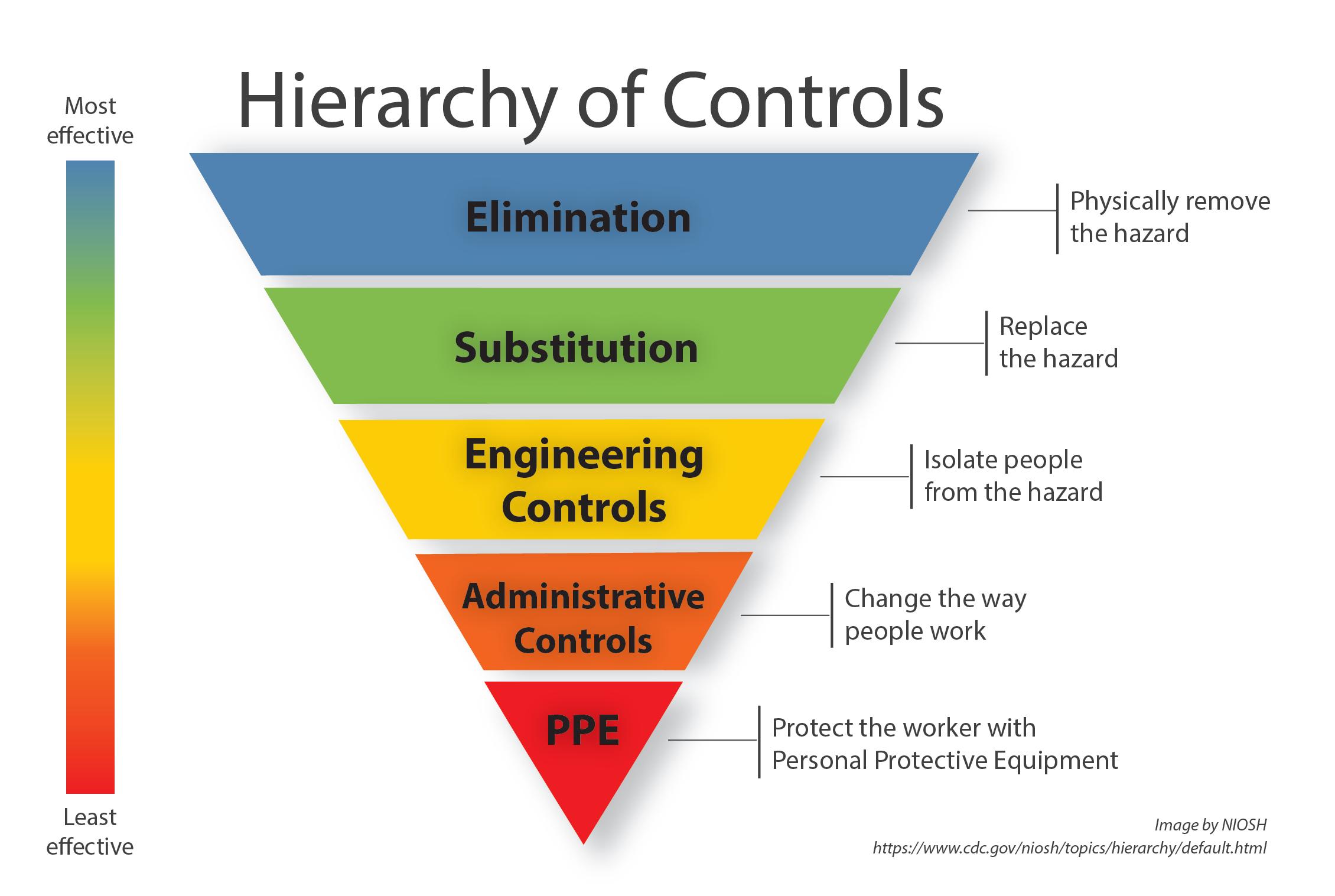

Another effective tool for preventing and controlling hazards and risks is the Hierarchy of Controls (Figure 6). This inverted pyramid illustrates how certain control methods are more protective than others. When possible, it is best to use strategies located at the top of the pyramid as they provide more safety.

Realizing that eliminating hazards is not always feasible, consider trying to find a substitution that might be safer before jumping to the bottom of the pyramid and just providing personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff. In certain situations, such as radiographing animals, it is unlikely you’ll completely eliminate the risk (radiographs are an important diagnostic tool, after all!), but ensuring staff complies with safety policies by wearing lead aprons, thyroid shields, and lead gloves is one of the few ways we can safely radiograph our patients.

24 | Unit 5

Figure 6. Hierarchy of Controls

Unit 6.

Involving Employees

25 | Unit 6

Unit 6. Training

Involving Employees

All staff members need to have safety training relating to job and animal safety. This may include formal continuing education or simple staff meeting presentations to ensure all staff know about the risks of the job and how to keep themselves from harm. Including staff members in the preparation (i.e., having a staff member present the information) is a great way to increase retention of safety protocols and policies and promote collaboration among staff members to keep each other safe.

Training should set expectations for all staff members with appropriate followup and enforcement as needed. Once expectations are set, leaders within the clinic need to model these behaviors to encourage others to comply with these expectations. This is a large tenet of the socioecological model and transformational leadership. If expectations are not being met, leaders must re-train and be sure staff are empowered to meet those expectations. Be sure to reward those meeting and exceeding safety expectations to allow continued promotion of a positive safety culture within the clinic.

Resources for training:

1. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Veterinary Safety and Health

2. AVMA PLIT Risk Management Training Resources

3. Occupational Safety and Health Administration publications (Leading a Culture of Safety: A Blueprint for Success and The Case Study for a Safety and Health Manacement System)

4. CDC Stop Sticks Campaign

Training resources for livestock producer safety:

1. Agricultural Safety and Health Council of America

2. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Agricultural Safety

3. Rural Firefighters Delivering Agriculture Safety and Health (RF-DASH)

4. Upper Midwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center

5. High Plains Intermountain Center for Agricultural Health and Safety

26 | Unit 6

Safety Meeting Essentials

Just-In-Time Training

• This type of training occurs in real time before an actual event. For example, if a hit-by-car dog is coming in, it is imperative to set up equipment and supplies before the dog’s arrival, but it is equally important to discuss how an injured dog may increase bite risks to staff handling a dog in pain and how staff can decrease this risk with proper handling and restraint. Most staff members know an injured animal can lash out aggressively when being handled, but a reminder right before an incident is crucial to keep everyone safe.

Tailgate Training

• Tailgate training uses short blocks of time, typically 10-15 minutes, with a small group of staff to discuss one safety topic. These trainings are informal, and while originally involving a pickup tailgate, they can occur wherever employees are comfortable within the clinic. A supervisor or staff member can perform these tailgate trainings and the topic should be drawn from something relevant to the clinic at that time. For example, if someone fell on a wet floor yesterday, the topic for the next day’s tailgate training might be on slips and falls on wet floors.

• By including tailgate training regularly, you are signaling to your staff that their safety is a priority and you value their input in the safety process.

Pre-Task Planning

• This form of training is used in unfamiliar situations or situations in which the hazards encountered are different from in-clinic hazards (think farm calls where there may be some unknowns). This type of planning allows you to brainstorm what hazards you might encounter and what you’ll need to combat those hazards.

• Steps for pre-task planning:

1. Think through the task from start to finish.

2. Identify any hazards you can think of and discuss the situation with coworkers. (What injuries could occur? What do you need to accomplish the task? Will you need more than one person to complete the task? Do you have enough training to complete the task safely? Are there any live hazards such as electricity, moving parts, confined spaces, etc.?)

3. Create your safety plan. (How can I apply the safety hierarchy? How many people are needed? What equipment do you need?)

4. Let your supervisor know where you’ll be and how long you expect to be there.4

27 | Unit 6

Unit 7.

Program Evaluation

28 | Unit 7

Unit 7.

Program Evaluation

Informal

Informally evaluating the clinic’s safety culture can be as simple as asking staff members how safe they feel in the clinic on a day-to-day basis. It can be included in employee evaluations as well. An observant manager or leader can monitor compliance with written safety guidelines (i.e., are staff members using appropriate PPE when radiographing patients?) and record how often guidelines are disregarded to determine the guidelines’ effectiveness.

After a training, you could ask staff if it was interesting. If a skill was discussed, you could ask an employee to demonstrate the skill to determine if they internalized the information and how well they perform the task.

Formal

Evaluation can also be more formal. This type of evaluation is best when it uses pretests to discern staff knowledge and understanding of safety protocols with posttests conducted after training. This allows you to compare results more objectively. A post-test a few months after the initial training can also help determine the level of retention gained from safety training. This will help improve future training.

By using formal evaluation, staff members are again reminded that safety is a priority of clinic leadership and their opinions are valued and used to improve safety training.

Figure 7 shows a safety attitude questionnaire example (also provided in Appendix E). Most of these questionnaires include sections on organization safety systems and behaviors, staff perceptions of management, risk perceptions, teamwork and communication, and a miscellaneous category. Low scores in any section can indicate that an area of safety culture needs to be addressed within the clinic. These sections are not all-inclusive, so be sure to consider issues that are specific to your situation in conjunction with trouble areas from the questionnaire. These questionnaires can be used for pre- and post-tests to help with evaluating safety programs.

29 | Unit 7

Figure 7. Examples of Safety Culture and Evaluation Statements

Thinking of your current workgroup, please read the statements listed below and mark the response that indicates the extent to which you agree with each statement. Statements Strongly disagree

People in charge are committed to improving safety.

People in charge place a strong emphasis on farm/ranch safety.

Safety issues are openly discussed between people in charge and the people I work with.

People in charge ensure the people I work with have adequate safety training.

People who work with me are committed to safety improvement.

Unsafe conditions are promptly corrected where I work.

People in charge encourage the people I work with to become involved in safety matters.

People in charge praise safe work behavior.

30 | Unit 7

Disagree Neither agree nor disagree Agree Strongly agree

Some general rules that apply to working with animals are:

a. Always have an escape route, establish a routine, and avoid quick movements and loud noises.

b. Work in dim lighting, always use an electric prod, and rush animals to get them to move faster.

c. Be extra cautious around mothers and newborns as well as mature male animals.

d. Both a and c.

Which of the following behaviors may indicate that an animal is aggressive or frightened?

a. Failure to make eye contact, standing still with its eyes closed, and reaching out to sniff your hand.

b. Rapidly lashing tail, pawing at ground, and stiff-legged gait.

c. Standing with its back to you, watching the gate, and bobbing its head.

d. None of the above.

What type of knot should you use to tie an animal?

a. Slip knot.

b. Square knot.

c. Bowline knot.

d. Cow hitch.

Which of the following statements describe strategies for avoiding kicks? Select all that apply.

a. Run up to the animal quickly.

b. Make loud noises as you approach the animal.

c. Approach slowly.

d. Stay close and keep one hand on the animal as you move around it.

When should the handler tie the horse inside the trailer?

a. Before closing the partition.

b. After exiting the trailer, from the outside.

c. From the inside of the trailer.

d. The horse should not be tied in the trailer.

Which of following is false regarding the loading and unloading process of horses?

a. They are slow processes.

b. You should back a horse out of the trailer.

c. You should never touch the horse during loading and unloading.

d. You should keep a hand on the horse while in the trailer.

31 | Unit 7

Reflection Questions

• After reflecting on your personal safety attitude, do you see any areas that already exhibit positive safety culture?

• How could you expand your positive attitude to encourage your colleagues to improve their safety attitude in these areas?

• Have you identified any areas of negative safety culture? How might you go about changing your attitudes in these more difficult areas?

Once you’ve addressed your attitudes about safety culture, you can progress to helping the clinic improve its safety culture. The questionnaire above can be utilized as a starting point for the general atmosphere in your clinic. It is important to include all staff members in the safety conversation. This is a large tenet of transformational leadership and promotes trust and respect among coworkers (remember the socioecological model). Their unique perspectives will elucidate why certain attitudes are persisting in the clinic, and their insights into solutions can be added to the clinic’s plan to improve safety culture.

32 | Unit 7

Reflection Questions

• After reviewing the responses from your staff, what areas need improvement?

• How might the clinic improve its safety culture?

• In what areas is the clinic succeeding? How will you maintain this level of positive safety culture?

Here are some examples that can help individuals and clinics create a positive safety culture:

1. Encourage continuing education in safety training.

2. Provide safety training for staff members.

3. Review OSHA standards.

4. Develop/enhance communication skills.

Final Thoughts for Continual Improvement

As with all evaluations, the goal is continuous improvement. Don’t get frustrated when everything doesn’t go according to plan. Re-evaluate where improvements can be made and move forward. Creating a safety culture will take time and careful planning. Using evaluations to illustrate leadership’s commitment to safety will encourage all staff members to take safety seriously and strive to create a positive safety culture at the clinic.

33 | Unit 7

Appendix A

Hazard Identification

Match the following hazards or practices with their associated hazard category.

________ 1. Poor animal handling techniques

________ 2. Poor knowledge of animal body language/behaviors

________ 3. Poor hand hygiene

________ 4. Improperly maintained anesthetic equipment

________ 5. Overbooking

________ 6. Understaffing

________ 7. Animal bites/scratches

________ 8. Zoonotic diseases

________ 9. Not wearing a mask during dental prophylaxis

________ 10. Destructive criticism

________ 11. Mixing cleaning products

________ 12. Topical parasiticides

________ 13. Fatigue

________ 14. Burnout

________ 15. Gossiping

________ 16. Eating/drinking in treatment areas

________ 17. Heat

________ 18. Noise

________ 19. Poor communication skills

________ 20. Faulty head catch

A. Physical

B. Biological

C. Chemical

D. Psychological

34 | Appendices

Appendix B

Job Safety

Task:

Basic job steps

Potential hazards

Recommended action or procedure

35 | Appendices

Recommended

36 | Appendices

Task: Basic job steps Potential hazards

action or procedure

Appendix C

Risk Assessment

Frequency

Frequent

Likely to occur; repeated

Probable Likely to occur several times

Occasional Likely to occur sometime

Remote

Not likely to occur

Improbable

Very unlikely

Catastrophic Death, permanent disability

Consequence

Critical Disability >3 months

Marginal Minor, lost work time

Negligible First aid, minor treatment

37 | Appendices

Appendix D

Haddon Matrix

Phases

Factors

People Agent/vehicle

Physical environment

Social environment

Pre-event

Event

Post-event

Adapted from Barnett et al. (2005).

38 | Appendices

Endnotes

1 Occupational Safety and Health Academy. (n.d.). Developing a construction safety management system: Setting the foundation. https://www.oshatrain. org/courses/ mods/833m1.html#:~:text=Culture%20may%20be%20defined%20 as,organization’s%20health%20and%20safety%20management.

2 Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (2002). Job hazard analysis. https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha3071.pdf

3 Steel, S., & Murphy, D. J. (n.d.). Safety and health management planning for general farm and ranch operations. Penn State Cooperative Extension. https://agsafety.extension.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/AGRS-123-Revised-Title.pdf

4 North Central Educational Service District. (2022, April 19). Pre-task planning: A critical process for safety. https://www.ncesd.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/ Safety-Matters-Pre-Task-Planning-compressed.pdf

39 | References

References

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2018, October 10). Hurt at work: Injuries common in clinics, often from animals, and usually preventable https:// www.avma.org/javma-news/2018-11-01/hurtwork#:~:text=Citing%20OSHA%20 data%2C%20Dr.,the%20average%20for%20all%20 professions.

Barnett, D. J., Balicer, R. D., Blodgett, D., Fews, A. L., Parker, C. L., & Links, J. M. (2005). The application of the Haddon Matrix to public health readiness and response planning. Environmental Health Perspectives, 113(5), 561-566.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022, December 16). National census of fatal occupational injuries in 2021. United States Department of Labor. https://www.bls. gov/news.release/pdf/cfoi.pdf

Fowler, H. N., Holzbauer, S. M., Smith, K. E., & Scheftel, J. M. (2016). Survey of occupational hazards in Minnesota veterinary practices in 2012. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 248(2). https://doi.org/10.2460/ javma.248.2.207

Gasperini, F. A. (2017). Agriculture leaders’ influence on the safety culture of workers. Journal of Agromedicine, 22(4), 309-311. https://doi.org/10.1080/105992 4X.2017.1357514

Northhouse, P. G. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed.) Sage.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (n.d.). Organizational safety culture - Linking patient and worker safety. United States Department of Labor. https:// www.osha.gov/healthcare/safety-culture

Steel, S., & Murphy, D. J. (n.d.). Safety and health management planning for general farm and ranch operations. Penn State Cooperative Extension College of Agricultural Sciences.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2023, March 3). Agricultural safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc. gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/default.html

Weichelt, B., & Bendixsen, C. (2018). A review of 2016-2017 agricultural youth injuries involving skid steers and a call for intervention and translational research. Journal of Agromedicine, 23(4), 374-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/1059924X.2018.1501455

40 | References

41

Utah State University Extension provides research-based programs and resources with the goal of improving the lives of individuals, families and communities throughout Utah. USU Extension operates through a cooperative agreement between the United States Department of Agriculture, Utah State University, and county governments.

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, Utah State University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University is an equal opportunity employer and does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination including harassment in employment including in hiring, promotion, transfer, or termination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy or any other federal, state, or local law. Utah State University does not discriminate in its housing offerings and will treat all persons fairly and equally without regard to race, color, religion, sex, familial status, disability, national origin, source of income, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Additionally, the University endeavors to provide reasonable accommodations when necessary and to ensure equal access to qualified persons with disabilities. The following office has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the application of Title IX and its implementing regulations and/ or USU’s non-discrimination policies: The Office of Equity in Distance Education, Room 400, Logan, Utah, titleix@usu.edu, 435-7971266. For further information regarding non-discrimination, please visit equity.usu.edu, or contact: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 800-421-3481, ocr@ed.gov or U.S. Department of Education, Denver Regional Office, 303-844-5695 ocr.denver@ed.gov. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kenneth L. White, Vice President for Extension and Agriculture, Utah State University.

Images and figures were provided by the authors and Utah State University (USU) Extension and USU College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences.

December 2023

Utah State University Extension (extension.usu.edu)

42 | Disclaimers

43 | Unit 7