HIGHLANDER magazine

There’s something about the wild we can’t ignore. For many of us, the outdoors is more than just a place — it’s a part of who we are. It grounds us, restores us and reminds us of our small but vital role in a vast and beautiful world.

Yet, the landscapes we cherish face mounting challenges. The current political climate has made the future of our national parks, public lands and fragile ecosystems increasingly uncertain. Conservation funding is under scrutiny, climate policies are shifting and the delicate balance of preservation and recreation hangs in question.

It’s a sobering reality but not a hopeless one. Across the country, advocates, scientists and everyday adventurers are stepping up to protect the spaces we love. In this issue, we hope to highlight stories of responsible stewardship, sustainable access and preservation of our wild places for generations to come.

As you read, I hope you’re reminded of the deep connection we share with the outdoors — it’s a bond worth protecting.

— Aubrey Holdaway

Future foresters grapple with job uncertainty

Utah’s big elk at Hardware Ranch

Gallery: National forests on film

Blind Hollow: Logan’s hidden winter retreat

Climate change brings drought, rising temperatures and fire risk

Saving the wetlands at the Great Salt Lake

Finding sanctuary, wellness and connection at Maple Grove

Reservoirs and resources: Stewarding Utah’s water

Gallery: Experiencing the outdoors

pg 24

Protect or profit?

The fight for Utah’s public lands

pg 28

Logan’s Backcountry Squatters

pg 31

Oldest living Colorado blue spruce finds a home in Utah

PRODUCED AND DISTRIBUTED BY USU

STUDENT MEDIA

0165 OLD MAIN HILL LOGAN, UTAH 84322-0165

Aubrey Holdaway

Kelly Winter, Emma Shelite, Layla Alnader, Essence Barnes, Malory Rau, Esther Owens, Samantha Isaacson, Claire Ott, Lacey Cintron, Brook Wood, Ella Stott, Sicily Clay, Aubrey Holdaway

Jack Burton, Kelly Winter, Claire Ott, Hazel Harris, Dane Johnson, Elise Gottling, Emma Shelite, Lacey Cintron, Aubrey Holdaway

Ella Stott, Isabella Erwin, Camille Simpson

COVER BY Aubrey Holdaway

INSIDE COVER BY Claire Ott

pg 32

Wildlife on the move: UDOT gets $9.6M to upgrade crossings

pg 34

Gallery: Utah wildlife

pg 36

Pando: How one tree makes a forest

The Scottish thistle stands for strength, bravery, durability and resilience, which is why we chose it for our logo.

pg 40

Utah Forest Restoration Institute takes aim at the West’s growing fire crisis

pg 42

Does Logan speak for the trees?

Imagine you’re a college senior who just landed your dream job working for the U.S. Forest Service — a career that won’t necessarily make you a lot of money but is fueled by a passion for the natural world and protecting our federal land. Then you receive an email terminating you.

On Feb. 14, thousands of federal employees received that email.

As part of an initiative by President Donald Trump’s administration to shrink the size of the federal workforce, probationary federal employees were terminated from their jobs across different agencies.

This initiative affected the whole nation and directly impacted students on Utah State University’s campus.

“Just seeing all these jobs go away and science being defunded — I guess I don’t really know what I’m doing with my life at the moment,” said Anna Hansen, sophomore in USU’s forest ecology and management program. “I had these goals to do, and now I’m not really sure if that’s going to work out.”

Federal probationary employees are people who have been in their role for under three years and

can be let go at any time. These jobs, after their probationary period, can turn into a lifelong career.

“Those types of employees were targeted by the administration to be let go because it was easy,” said Ellen Orlea, junior in USU’s forestry program.

Orlea was someone who received a termination email. She was hired out of high school in the Cedar City Ranger District and worked out of Filmore for the last two summers.

While the termination was “blindsiding” for Orlea, she said it wasn’t as devastating to her as others she knows — people who moved across the country for a job they have now been let go from.

These federal employees who manage the federal lands do everything from maintaining hiking trails and manning entrance stations to wildfire prevention. Temporary or newer employees are a large portion of that workforce.

“The American public doesn’t realize how much these government employees who have been cut — how much they do for public land,” Orlea said. “Without all these lower-grade employees, the nation would not function and will not function. People don’t see that until it’s gone.”

Federal and state land is protected land for wildlife, plants and people. According to Utah.gov, 71% of the land in Utah is managed by either a federal or state agency, an amount of land bigger than the entire state of Arkansas.

“Especially with the urban population along the Wasatch Front, people need that escape — that release. That has to be protected,” said Darren McAvoy, wildland resource professor at USU. “If you just let it go by itself, it’s a little bit more inclined to have troubles with fire, insects or disease. Long-term prudent forest management can help minimize the disturbances that happen on our forest land.”

Utah’s Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management primarily manage wildlands containing woody species in Utah, but it’s about more than just the trees. Taking care of the forests is important, as most of the water in Utah comes from forested land. The better the care, the higher the potential for water quality and quantity.

Another important aspect of the Forest Service is fighting wildfires. Hansen, who has a job this summer in wildland firefighting, didn’t lose her job.

“Cutting everything else is crazy, but then firefighting is even crazier,” Hansen said. “I feel like they stopped the hiring of a lot of wildland firefighters with the hiring freeze, so it’s kind of made the

summer of wildland firefighting feel a bit more scary because there’s going to be less people to help, and with climate change, the fires are only getting worse.”

These positions help preserve and protect the land. The people who work in these fields typically do it because of a passion, not money.

“I’ve always really cared about conservation science and protecting the planet, and to see that other people don’t care and the government doesn’t care is kind of a depressing feeling,” Hansen said.

The Quinney College of Natural Resources at Utah State has several different majors for students to turn their passion for the outdoors into careers.

In years past, there were more forestry jobs than USU students to fill them, and the Forest Service paid a lot of attention to QNCR graduates.

With the changes and terminations, the outlook for this year’s graduates could be very different and affect those still in college who are considering pursuing this career.

“There’s still a need for foresters longterm in the country,” McAvoy said. “I still believe that job prospects are probably

better now than they have been anytime during my 40-year career, despite the challenges with the uncertainty from the federal government.”

Since the layoffs, some jobs have been brought back, but there is still uncertainty in the future of both forestry and other land management agencies. The lack of jobs is not the only reason Hansen is concerned.

“The Earth is so beautiful, and it’s our home. We all live on it as one community of humans and whatnot, and it provides for us,” Hansen said. “It’s just sad to see that people don’t appreciate that.”

Even with the current uncertainty, McAvoy said he is still encouraging students to pursue these careers.

“Even if you’re not pursuing a career in forestry or land management, the work that these people do affects you,” McAvoy said. “Any trail that you use, picnic area you enjoy or fire that could be near your house is managed by someone working in these federal or state agencies.”

35mm, 400 ISO

Nestledalong the serene Bear River in Southeastern Idaho, about an hour’s drive from the Utah State University Logan campus, Maple Grove Hot Springs offers a unique retreat blending natural beauty, personal wellness and community connection.

Spanning 45 off-grid acres, this riverfront sanctuary invites guests to immerse themselves in geothermal mineral pools, engage in holistic activities and disconnect from the digital world.

In 2018, the springs faced an uncertain future after several foreclosures.

Recognizing its historical and cultural significance, owner Jordan Menzel embarked on a mission to preserve and rejuvenate the space. Menzel’s vision extended beyond merely maintaining public access. He aspired to create a wellness retreat center

that celebrates the area’s natural splendor and fosters meaningful human connections.

“The story of Maple Grove really is about a bunch of people coming together to preserve a hot spring that many people have loved for generations,” Menzel said.

At the heart of Maple Grove’s philosophy is presence and mindfulness. In an era dominated by digital distractions, the retreat offers a haven free from Wi-Fi and cell phone service, encouraging guests to engage fully with their surroundings and each other.

“There are just very few places these days where you don’t have cell phone service, so you kind of just have to figure it out — you get here, you got to talk to people,” said Spencer Felix, USU student and yoga instructor at Maple Grove.

This intentional disconnection allows visitors to experience the therapeutic benefits of the natural setting, from observing local

wildlife like bald eagles and trumpeter swans to soaking in the mineral-rich hot springs.

“The most important step in personal wellness is presence,” Menzel said. “It’s being really front and center to what’s going on in your mind — your body — having time and space for meaningful conversation.”

The springs operate entirely off-grid, utilizing solar and hydropower to minimize its environmental footprint. This commitment to sustainability not only preserves the pristine landscape but also serves as an educational model for guests interested in eco-friendly practices.

“We’re in a natural setting,” Menzel said. “It gives us the opportunity to introduce people to a beautiful truth that it’s possible to have a restful, amazing experience while also minimizing or eliminating a lot of the heavy carbon outputs required for just modern society.”

Guests can choose from a variety of lodging options, including fully furnished stone cabins, yurts, cabins and wooded campsites. Each accommodation provides 24-hour access to the hot spring pools, riverfront beach, hiking trails and wellness classes such as yoga and guided sauna circuits.

“We have really great events almost every weekend: aquatic yoga classes, open mic nights, acoustic concerts, workshops,” Felix said. “So, for college students especially, it’s an awesome place to check out.”

The retreat also hosts workshops and events aimed at personal growth and community building. These programs encourage participants to step out of their comfort zones, fostering progress and happiness through new experiences.

“Deep within our retreat center ethos is the idea that as humans, we’re at our best when we can make ourselves just a little uncomfortable physically, socially or emotionally

to try new things,” Menzel said. “In that discomfort is where growth happens.”

To maintain a peaceful and respectful environment, Maple Grove has established clear guidelines. The retreat is an alcoholand drug-free zone, and guests are encouraged to observe silent hours after sundown to enhance the contemplative atmosphere. Swimwear is required in all communal areas, and the use of electronic devices is discouraged to promote genuine human interaction.

“This is very much like a retreat facility, so it’s different from a party place,” Felix said. “Yes, there’s a lot of fun here, but it’s fun that looks different. We’re a noise-free environment, so after hours, we try to be very still and quiet. Lots of people travel here for the silence.”

Looking ahead, Maple Grove plans to expand its offerings by integrating sustainable food and farming practices. These initiatives aim to provide guests with fresh,

locally-sourced meals and hands-on learning opportunities in ecological stewardship.

“We’re designing the final frontier for our space and experience, which is food and farming,” Menzel said. “Soon, we’ll be making some big commitments to building out our capacity and infrastructure for producing food in a way that everyone can learn from through workshops, as well as bringing that food into our guest experience through our dining experience.”

Maple Grove is open to the public daily from 10 a.m.-9 p.m., with closures on Wednesdays for maintenance. Due to limited capacity, guests are encouraged to book their visits in advance to ensure a tranquil and personalized experience.

Whether seeking solitude, community or a blend of both, Maple Grove offers a rejuvenating retreat where nature and wellness converge.

LAYLA ALNADER

What was once a near-vanished symbol of Utah’s wilderness is now a testament to resilience and conservation. The Rocky Mountain elk, hunted by Native American tribes for centuries, had nearly disappeared from the state by the late 1800s due to overhunting by settlers, but today, elk herds thrive.

In 1910, Utah’s first official efforts to protect and conserve elk began when the state’s first game laws were enacted. The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources was created in 1921 to regulate hunting and manage wildlife populations more effectively.

“Hardware was set aside as a WMA [Wildlife Management Area] in the late 1940s specifically for wintering big game,” said Marni Lee, wildlife recreation programs coordinator for the Utah DWR at Hardware Ranch in Hyrum.

“The education center is just one part of the Hardware Wildlife Management Area. Because of its status as a WMA, the land will never be developed, giving our local and statewide communities

opportunities to immerse themselves in Utah’s wildlife habitats forever.”

By the 1950s, the DWR began a series of elk translocations, bringing elk from other western states to repopulate the land. These efforts were successful, and by the 1960s, elk populations were on the rise once again.

Today, elk hunting in Utah is regulated through a lottery system where hunters apply for a limited number of permits each year. Hunting has become a dynamic tool used for population management as people learn more about range ecology.

DWR carefully monitors and adjusts hunting permits based on species population levels, habitat conditions and weather to maintain a healthy and balanced ecosystem. Many of Utah’s wildlife species rely on hunting to keep the population at an optimal level, while others rely on natural predators.

In 2024, the state increased the number of permits for the first time in six years. This marked a sense of optimism about the effects of hunting on Utah’s environment and the future of hunting.

Brad Hunt, DWR wildlife management area manager said the deer and elk populations have grown over the past few years due to lighter winters.

“The outlook for wildlife in Cache Valley is relatively good,” Hunt said. “Overall, wildlife are faring well. Wildlife still face issues such as urbanization and the loss or fragmentation of habitat.”

Science and technology has become a valuable tool for hunters and animals. GPS systems and detailed data analysis provides information on geographic spread, weather conditions, trends in elk behavior and migration patterns. Studying this information can help better inform wildlife management decisions.

The Hardware WMA, owned by DWR, spreads across 14,332 acres and is located in Blacksmith Fork Canyon. The Hardware Wildlife Education Center is just one component of the complex operation. The center provides an opportunity for visitors to discover Utah’s wildlife and their associated habitats. During the spring and fall, visitors can enjoy guided walks through nature,

crafts and informational panels focused on a specific wildlife topic.

“Our WMAs in Cache Valley are vitally important in helping these populations survive in the winter and mitigate the winter nuisance and depredation,” Hunt said.

The DWR closes wildlife management areas seasonally to provide wintering areas that allow wildlife to escape people and conserve bodily resources needed to survive the winter. Obeying these closures is vital in preserving wildlife safety and health.

“It’s important to recreate responsibly,” Hunt said. “Disturbance in sensitive areas can promote erosion, result in the removal of native plant species and promote the establishment of noxious and invasive weeds that degrade habitat.”

Lee oversees visitor services, including education and interpretive programming. She said her role has helped her see wildlife, hunting and land preservation as a tool for people to discover the natural world.

“I think about the endless opportunities for teachable moments,” Lee said. “When I think of wildlife, hunting and land preservation, I think of them as complex areas of study and management that involve more than the best science.”

During the winter months, visitors can ride through a herd of elk on a wagon and learn more about the ecology, anatomy and migration patterns of elk. The property is open year-round for hunting, fishing, camping and other outdoor recreational activities.

“Everyone can connect to wildlife somehow, and with Utah’s diverse wildlife populations, everyone can find something wild that calls them to action,” Lee said.

The education center is a part of the WMA perhaps most famous for the elk-viewing wagon rides. According to Lee, the rides began through an elk-feeding program in the late 1940s to mitigate wildlife damage to private lands in Cache Valley.

“In addition to offering rides, feeding the elk gives us an opportunity to trap some of them and determine the overall health of the herd,” Lee said.

WMAs primarily exist in winter use areas. Ongoing habitat restoration and improvement projects help maintain adequate space for wintering wildlife to congregate.

When enjoying and interacting with wildlife and their habitat, it is crucial to practice the Leave No Trace principles, according to Hunt.

“Following road-use directions, staying on designated roads and trails and camping in designated areas plays a huge role in reducing the amount of damage done to wildlife habitat,” Hunt said. “By cleaning up after ourselves and leaving spaces better than we found them, we can all help keep the areas we recreate in clean and beautiful.”

When snow falls in Logan Canyon, groups of backcountry skiers can hike up the trails of Blind Hollow Trail and spend the weekend in Utah State University’s backyard winter campsite: the Blind Hollow Yurt.

Managed through USU’s Outdoor Program, this Mongolian-style winter yurt gives both students and non-students a unique opportunity to experience Logan winters up close.

Unlike a tent, the circular design of yurts make them more spacious and allows for better protection against weather elements. This makes them ideal shelters for winter camping.

“Yurts are not permanent structures, and they wear out over time,” said Dan Galliher, USU Campus Recreation outdoor programs and facilities associate director. “The yurt that’s up there now is the second one.”

The original yurt was built by USU in 1996 and later rebuilt in 2007. OP made the yurt available for trip reservations to provide Logan’s outdoorsy community with a local opportunity for winter camping and multi-day backcountry skiing.

“The yurt trips are definitely one of our more involved winter trips,” Galliher said. “It is not ‘glamping’ by any stretch of the imagination.”

The yurt is located atop the mountains of the Bear River Range, surrounded by trees, snow and roughly 2,500 feet of elevation. The only way to get there is on backcountry skis or snowboards.

“Hiking on backcountry equipment is not like hiking in your hiking boots,” Galliher said. “It’s much more strenuous.”

On the first day of the trip, backcountry skiing groups must hike up roughly 4.5 miles of snow to reach the yurt campsite. According to Galliher, this can take groups anywhere from 2.5–7 hours depending on experience and skill level.

“We typically recommend that you can ski a black diamond at a ski resort and have had some backcountry experience,” Galliher said. “Any days that they’re up there, the main emphasis is to be out skiing.”

The yurt is equipped with a full camp kitchen and bunk beds for six, along with sleeping bags, cots and a wood-burning stove. Guests only need to bring their ski equipment and food.

“It will fit up to nine people — not very comfortably, but you can get nine people in there,” Galliher said. “It’s definitely a very rustic backcountry skiing yurt.”

OP hires student yurt hosts during the winter season to keep the yurt in good condition between rentals and to help assist backcountry skiing groups.

Clayton Shaw decided to become a yurt host after attending three backcountry yurt trips himself. He has now been a yurt host for the past two seasons.

“I start off by giving them a little bit of information about what it takes to get up there,” Shaw said. “I make sure that they have all the information they need as far as where everything is in the yurt, where they’re supposed to dig snow to melt water, what areas work well to ski in and what areas they should avoid.”

Yurt host duties also include hiking up to the yurt at least once a week to restock supplies like toilet paper and fire starters, chop wood and shovel snow.

“There is no established trail in the winter,” Shaw said. “So when I go up, I also put up a track that vaguely follows the summer trail, and from there, everyone can kind of ski where they want to.”

According to Shaw and Galliher, yurt hosts do not stay for the duration of the trip and are mainly there to serve as informational consultants.

“As the host, I just get them set up and turn them loose,” Shaw said. Once the yurt host leaves, it is up to the group to manage the yurt and explore the landscape for themselves.

OP offers two kinds of backcountry skiing yurt trips: private and university-led.

“If people are renting it out themselves, they spend the whole time up there backcountry skiing,” Shaw said. “If they’re on a university trip, their trip leaders are up there picking the run list and everything for them.”

Yurt trip attendees get to spend all day exploring miles of Bear River backcountry and popular riding terrain around Blind Hollow.

“It is a wilderness area, and they’re pretty much on their own,” Shaw said. “I think that’s what a lot of people like about the yurt.”

According to the U.S. Forest Service, a wilderness area is where motorized equipment and development are illegal. Places are dubbed wilderness areas in order to preserve and protect their natural ecosystems.

“When you’re out there, it’s pretty much just you and the group that you went with, which I think is awesome,” Shaw said. “It is a beautiful area.”

Yurt rentals are typically open from late December to the end of March. The fee for students is roughly $300, and the fee for non-students is roughly $500.

“These are always one of our most popular trips,” Galliher said. “Most of the time, students who go have never been camping in the winter before, and they’ve possibly never seen a yurt.”

According to Shaw, another appealing characteristic of the yurt to guests is the convenience.

“Camping involves bringing in your stove and camp gear and everything and then possibly digging out a spot to pitch a tent and being really cold overnight,” Shaw said. “At the yurt, you can be camping in the winter — in the snow — with a lot more comfort than if you just went to any old trailhead.”

The yurt is maintained through USU student fees, giving students priority access to weekend reservations and a discount on ski equipment rentals.

“Our mission is to provide opportunities for adventure and discovery, and this fits right in there,” Galliher said. “It’s very adventurous, especially if you’ve never done it before, and that’s what we push through OP.” 13

Utah’s reservoirs are more than just scenic bodies of water — they are the lifeblood of the state’s agricultural industry, drinking supply and overall sustainability.

Utah’s diverse geographic landscape is home to 137 reservoirs, each one playing a vital role stewarding the state’s water resources, including supporting its 10.5 million acres of agricultural land.

Patrick Belmont, professor of hydrology and geomorphology in the Department of Watershed Sciences at Utah State University, said reservoirs offer a buffer for agriculture.

“It’s hard to have a population anywhere near this size and be growing this amount of food if you don’t have access to water all throughout the year,” Belmont said.

Managing Utah’s water resources is a unique challenge due to the state’s diverse climate, spanning from the mountainous Wasatch Range to the arid desert.

“There’s a big gradient in terms of where our water is, and that also relates a fair bit to where our population is,” Belmont said. “We’ve got a lot of our population centers around the Wasatch Front, and that’s where a lot of our reservoirs are. A lot of other places — we just can’t have a large population because there’s no water to even dam up.”

Candice Hasenyager is the director of the Utah Division of Water Resources.

“Water in Utah is hyperlocal,” Hasenyager said. “It really depends on where you’re at, what your water resources are and what storage reservoirs you have. It has to be managed at the individual and local level.”

Utah reservoirs are currently 80% full on average, according to Hasenyager. This excludes some of the larger reservoirs such as Lake Powell, which is at approximately 35% capacity.

“We’re seeing really good reservoir levels because of the previous wet years that we’ve had,” Hasenyager said. “This is about 20% higher than normal due to that additional carryover from those earlier wet years.”

Snowpack, a metric that directly impacts reservoir levels, makes up 95% of the state’s water supply.

“Right now, our current snowpack statewide is about 92% of normal for this time of year, so definitely below where we’d like to see it,” Hasenyager said. “But if you look at the broader picture of the state, there’s definitely some regional impacts that are going on.”

According to Hasenyager, snowpack levels in Northern Utah are normal, ranging from 90% to 108%. In the central part of the state, snowpack is between 55% and 82% normal and is even lower in Southern Utah, ranging from 29–31%.

According to Belmont, there has been a greater fluctuation between delivery and melting of snow due to warmer temperatures, changing how reservoirs are managed throughout the year.

“Reservoir operators are starting to think earlier in the winter about how much water they should be diverting to fill the

reservoirs versus how much they should be passing downstream,” Belmont said.

During the spring, reservoir operators attempt to find the balance between storage and passage of water. In the summer, their focus shifts to responding to calls for water, using meters to ensure there is an adequate amount for the current year and a base fill amount for the next year.

“That can be a tricky game to play because if you go into a sequence of dry years, it’s not guaranteed you’re going to get the reservoir refilled the next year,” Belmont said. “So, they may scale things back a little bit if they see that they’re starting to run low.”

A key part of water resource management is mitigating the impact of inevitable fluctuations — conserving water usage allows for more water storage in reservoirs that creates a holdover for dry years and a greater reserve of groundwater.

“One of the best things that we can do is use less water,” Hasenyager said. “If we use less water, we’re making ourselves more resilient to any sort of fluctuations that occur.”

While reservoirs serve an important purpose, Belmont is concerned with potential risks they can cause.

“As humans, we’re really good at setting really narrow goals and achieving those goals,” Belmont said. “We wanted to store water. We’re really good at that goal, but then we often don’t think of a lot of the unintended consequences.”

According to Belmont, soil erosion caused by wildfires can lead to sediment entering reservoirs, which can have detrimental impacts on water quality.

“When that fills up the reservoirs, it can cost tens of millions of dollars to clean that sediment back out,” Belmont said. “Sometimes, it also just completely removes a reservoir from being able to be used for a while.” Reservoirs have also been found to produce large amounts of methane, a strong greenhouse gas, due to carbon that gets stored and broken down in the reservoirs. They can also disrupt aquatic ecosystems and be expensive to maintain.

“The costs for that are starting to add up,” Belmont said. “I’m afraid we’re handing those costs off to younger generations without really dealing with them.”

From Hasenyager’s perspective, the mindset around water usage has changed significantly.

“In the past, we’ve seen a lot of effort to create new dams and reservoirs, and now it seems like we’re trying to figure out how to use our water as widely as possible,” Hasenyager said. “I’ve seen more of an emphasis on how we can conserve and use the water as best we can today.”

Such conservation happens at an infrastructural level.

“Looking at our housing types and our property, looking at how landscaping goes in and doing it right the first time to make sure we’re using low water use plants and drip systems,” Hasenyager said. “There’s been a significant investment into water and trying to help us create a more resilient water supply for our future.”

Belmont hopes to see a philosophical change in how humans steward the earth’s natural resources.

“The number one thing would be to tread much lighter and steward our environment with a much greater sense of humility — recognizing that we’re part of this ecological system and anytime we alter that system, there are going to be ramifications and some unintended consequences,” Belmont said.

PHOTO BY Claire Ott

BY

SAMANTHA ISAACSON

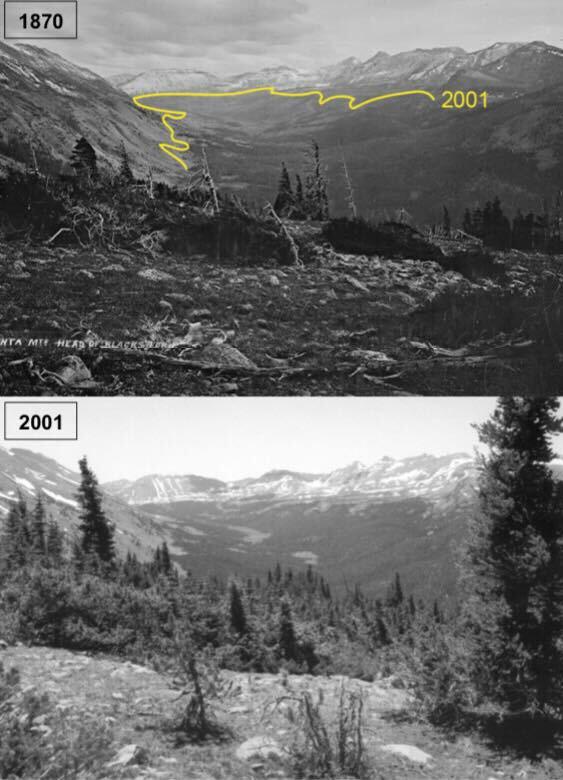

Climate change affects the entire world, and Utah is no exception. Over the past four decades, Utah’s annual mean temperature has risen 0.4 degrees Fahrenheit every decade.

The rise in temperature has caused a multitude of changes in Utah’s climate and has created many problems because of it.

Scott Hotaling, assistant professor of watershed sciences at Utah State University, said the rise in temperatures has caused a decline in winter snowpack in Utah.

“The reservoir of snowpack each year in Utah is our seasonal buildup of water, and it is getting smaller,” Hotaling said. “It’s not getting smaller super fast, but it’s trending downward, and it has been for our 45-year record that we’ve been monitoring.”

Between 1979 and 2023, there has been a 16% decline in peak snowpack statewide.

Hotaling said along with the snowpack getting smaller, peak snowpack and runoff time are shifting further away from the summer months.

“It’s not a huge shift in timing, but it’s on an order of days, and every day that it shifts earlier means that there’s a longer summer dry period,” Hotaling said. “In Utah, we really need water in July, August and September. Those are the hottest and driest months of the year in Utah, so the more we shift our snowpack peak away from those months, the less water is actually going to still be available when those months come.”

Andre Geraldo de Lima Moraes, assistant professor of climate data analysis at USU, said another issue related to rising temperatures in Utah is a change in how much precipitation falls as snow in the winter.

“Part of the reason Utah has less snowpack is because it’s warmer during the winter, and precipitation that used to fall as snow is now falling as rain,” Moraes said.

Between 1960 and 2010, the proportion of winter precipitation falling as snow in Utah has declined by about 9%.

According to Brad Washa, USU assistant professor of wildland fire science, the change in snowpack and subsequent hotter, drier summers has increased fire risk in Utah.

”The snowpack is melting off pretty fast instead of building right now,” Washa said. “With the snowpack gone a lot earlier, fuels like grass and such that carry fire across the landscape are now available and have a longer period where they can dry out.”

Washa also said the timeframe for increased fire risk in Utah is getting longer.

”The fire season starts earlier in the summer and lasts later into the fall,” Washa said.

“Last fall on the Wasatch Cache Uinta, there was the Yellow Lake Fire that lasted well into October — a fire of that size occurring in October is unheard of. Normally at that time of year, you’d start seeing cooler temperatures and more moisture.”

Washa said as temperatures continue to rise during the summer, the fires are going to start burning at a higher level of severity.

According to Moraes, hotter summers in Utah also lead to issues with crops in the summer.

“Hotter summers also mean more rapid evaporation from the crops, which means farmers have to use more water,” Moraes said.

Wei Zhang, assistant professor of climate science at USU, said the public should also be concerned because it impacts everyone who lives in Utah.

“I think everyone should definitely be aware of climate change for many reasons. There’s the changing water cycle, for example, that increases drought occurrence — drought intensity — in Utah,” Zhang said. “Those effects on the water is a big deal in Utah

because we are in the dry region, so if the water gets more and more diminished, then that’s going to affect everyone here.”

Hotaling said in order to help fight climate change, the public should work to educate themselves, specifically on what choices are the most impactful in terms of urban emissions and greenhouse gases.

“Practicing using public transport or riding a bike or walking to work when you can really helps. Using solar power is also more efficient and climate-friendly than burning coal or natural gas,” Hotaling said. “Meat just as a product of how it has to be raised and the amount of resources that go into it can be a very climate-intensive thing to produce. So, if you want to eat meat, at least try and make better choices like chicken or pork or beef — also eating more vegetables. Instead of drinking regular milk, drink alternative milk, which uses way less water. It’s really about personal choices and being more mindful of those.”

For students who want to get involved with climate change, USU offers a Climate Adaptation Intern Program.

Those who wish to find more information about climate change can visit the USU Climate Adaptation and Resiliency page.

CLAIRE OTT

Concern over the state of the Great Salt Lake, the largest saline lake in the Western Hemisphere, has steadily increased over the last few years.

Located in the Great Basin watershed, the lake is a natural feature that has garnered increasing attention. While shrinking water levels and toxic dust are major worries, researchers in the Wetland Ecology and Restoration Lab at Utah State University say water isn’t the only concern.

Karin Kettenring, head of the lab, said the presence of invasive phragmites grass, a type of common reed, presents problems for the lake and surrounding wetland.

“It takes up a lot of water, and then when you multiply that out over tens of thousands of acres, that’s a massive amount of water consumption,” Kettenring said.

Phragmites spread rapidly by releasing seeds into the wind. Previously, managers thought the plants mainly spread through root and stem expansion, but Kettenring’s lab discovered seeds play a bigger role, changing how experts manage the issue.

“It spreads much more by seeds than this clonal spread,” Kettenring said. “If you’re trying to manage it, you need to actually deal with those seeds.”

These invasive plants pop up in dense bunches that can grow up to 15 feet,

thrive in disturbed areas like roadsides and compete well with other plant species.

“Once you know what it looks like, if you drive, you see it everywhere,” said Sam Kurkowski, lab manager.

Without natural predators to keep them in check, Kurkowski said phragmites crowd out native vegetation. Native plants are essential for healthy wetlands, providing food and habitat for wildlife.

“In the battle to have functioning wetlands, native plants are a key part of that,” Kurkowski said. “Our lab is trying to figure out how we can re-establish native plant communities that are dwindling and make them the dominant plant communities again.”

Another challenge with invasive phragmites is once it’s removed, it is likely to return unless it is replaced by another plant, which is where restoration efforts come in.

Montana Horchler, master’s student in the lab, is conducting growth chamber experiments to see how different temperatures affect seed germination.

She tested the effect of three different temperature regimes on seed germination and used a microscope to count the number of seeds germinated every two days.

From that, she was able to generate “germination curves” that visualize the process and “show us what conditions the seeds need to germinate to their fullest possible extent,” Horchler said.

As water availability continues to become more uncertain, Horchler said it might make sense to use species more drought and salt tolerant. She said this isn’t something groundbreaking, but it has yet to be done at the Great Salt Lake. “Managers are already doing seed-

based revegetation,” Horchler said. “Usually, they’ll seed in May or June, and it’s possible that with higher summer temperatures and increasing water availability uncertainty, it might make sense for us to put seeds out in the fall.”

Hailey Machnikowski, another master’s student in the lab, has a similar twopart setup with a field and greenhouse experiment she says is aimed at “adapting restoration for climate extremes and for weather extremes.”

Her field experiment compares two different types of restoration frameworks: a precision framework and a number of bet-hedging frameworks.

“[We want] to see which one is going to be most effective in a world with constantly changing and unpredictable water conditions,” Machnikowski said. “You’re essentially choosing the right species, seeding them at the right time and putting them in the right place.”

With the bet-hedging framework, also referred to as risk mitigation, the assumption is that conditions are

unknown, variable and likely to be extreme.

“We put out a bunch of species, and hopefully conditions will be right for at least some of them to stick,” Machnikowski said.

The other two bet-hedging approaches involve separation of dormancy break time and seeding time, which Machnikowski said gives the seeds a chance to succeed if conditions aren’t right the first time.

Machnikowski is also testing how young plants handle drought and flooding.

“Seedlings are a lot more vulnerable because they haven’t yet developed the plant structures that adult plants have that makes them more resilient,” Machnikowski said. “We want to know that these young plants are still going to be hearty enough to survive potentially rough conditions.”

The goal of her research is to improve the outcomes of large-scale reseeding efforts for Great Salt Lake restoration, 19

especially as climate change is projected to cause more severe drought and precipitation events.

“It’s important that we figure out how to adapt these practices so that they’re still going to be effective in a changing world, whether that’s from climate change or if it’s from anthropogenic impacts,” Machnikowski said.

With quality and long term sustainability in mind, Kettenring emphasized the importance of restoring lots of different plants back to the wetlands.

“We’re really trying to combat that homogenization of wetlands that’s occurring,” Kettenring said. “Particularly from a restoration standpoint, we’re trying to find lots more species that can be used in restoration.”

Ecosystems function much better and are more resilient in the long run when the biodiversity is higher, according to Kettenring. Healthy wetlands filter water, prevent floods and provide critical habitats for birds.

“We don’t know what the future is going to bring in any particular wetland because, you know, weather is so variable year to year,” Kettenring said. “If we can get more of that diversity in there, it’s kind of like an insurance policy.”

At the heart of Utah’s culture and its land lies the Great Salt Lake, and Horchler believes it is imperative it be taken care of.

“I strongly believe that it’s an important thing to steward the Great Salt Lake in a way that is good for future generations

of people and all living things,” Horchler said.

According to Kurkowski, wetlands are one of those things people don’t think much about, and the trick is trying to get people to care about them before it’s too late.

“You take it for granted until it’s not working anymore and there’s not enough clean water or water at all,” Kurkowski said. “Wetlands do lots of really important things for us and for nature. It’s really important to be able to restore that diversity back into wetlands.”

BY Jack Burton, Claire

Ott and Aubrey Holdaway

The fight for Utah’s public lands

Spanning2.26 billion acres is a mosaic of geologic diversity known as the United States, from the red rock deserts of Moab and the evergreen forests of the Sierra Nevada to the icy blue glaciers of Alaska. Of these acres, 840 million are deemed public lands: federally managed areas open to all and safe from private development.

Federally held public lands are managed by agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Department of the Interior and the National Park Service. Land policy regulates the acreage in accordance with the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, which aims to take a balanced approach to thoughtful development and preservation.

In an August 2024 lawsuit, the State of Utah sought to challenge this designation, claiming federal possession of unappropriated lands is unconstitutional. As filed, the lawsuit could have had dramatic implications not just for Utah but for over 150 million acres of U.S. landscapes.

“The net result would have been the undoing of the federal lands system in the American West,” said Steve Bloch, legal director for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

Utah’s lawsuit, directly filed with the Supreme Court of the United States, targets unappropriated lands: public lands lacking a congressionally defined purpose, unlike national parks, monuments and conservation areas.

Unappropriated lands encompass around 18.5 million acres in Utah, according to the Utah Senate.

“The State of Utah was asking the United States Supreme Court to skip the line — to not have to bring a case in federal district court through the court’s appeal and ask the Supreme Court to hear it that way, which is the way most cases are built up,” Bloch said.

In Utah, anti-public land sentiment is not new. Despite ceding all rights to federal land in 1812 as part of becoming a state, Utah has historically vied for state control.

“This has been a big fight since at least the 1980s — people wanting to have what is federal land turned over to state or private ownership,” said Nichelle Frank, assistant professor of U.S. history at Utah State University. “Utah has been a big part of that discussion.”

Born from the 1970s movement, the Sagebrush Rebellion, states dominated by public lands would first push against federal management via legislative action. Dubbed the “sagebrush rebels,” members of the movement saw public lands as federal oversight.

“These are ranchers who want to continue using lands for grazing,” Frank said. “They feel the government has too much of the land and want to see more state, county or private control of these lands.”

The movement reached a tipping point with the enactment of the FLPMA in 1976. In July of 1980, hundreds of sagebrush rebels bulldozed a road through a wilderness study area near Grandstaff Canyon Trail in Moab, declaring independence from the BLM.

“They then get a lot of lip service support from the [Ronald] Reagan administration, who aligns very politically with them,” Frank said. ”Over the course of the 1980s, you see a lot of cuts to federal spending for public land management.”

Despite appeasements made on behalf of the Reagan administration, the ideals of the rebellion continue to circulate today.

BY

“Reagan is actually very disappointing to them, so the sagebrush rebels ultimately continue to exist,” Frank said. “There are people today who are a part of that story. They transition into something called the wise use movement, and it’s the same idea of anti-federal government control.”

Utah currently runs on the “Stand for our Land” campaign, stating unappropriated lands should fall under state management. According to a public statement from the campaign, Utah hopes to manage unappropriated land for multiple uses, “prohibiting the privatization of these public lands except in rare situations.”

However, environmental organizations and other entities argue this land would fall into private hands.

Utah currently runs on the “Stand for our Land” campaign, stating unappropriated lands should fall under state management. According to a public statement from the campaign, Utah hopes to manage unappropriated land for multiple uses, “prohibiting the privatization of these public lands except in rare situations.”

However, environmental organizations and other entities argue this land would fall into private hands.

“Utah’s congressional delegation in the halls of Congress is talking about the sale, disposal or transfer of federal lands

into state or private hands,” Bloch said. “We’re tackling this at a variety of levels, both in the courts and in the court of public opinion.”

Patrick Belmont is the department head of watershed sciences at USU.

“I think there is a very legitimate concern about this land being taken from public hands and given out to private landowners,” Belmont said. “The historic record is not very good in terms of conservation and biodiversity protection, and there is a history of privatizing the profits of these lands.”

Lands under private ownership are not held to the same environmental protections, creating potential for irreversible damage.

“When land becomes privatized, often the landowner is managing it in a way to maximize short-term profits,” Belmont said. “That usually involves some degradation, which is often irreversible or very costly to fix.”

Belmont argues the best way to protect these environments is through public lands, as federal entities can be better held accountable for the stewardship of the land.

“Stewarding the land in perpetuity means keeping it ecologically healthy,” Belmont said. “These are all ecosystems we are trying to manage, and these ecosystems are fragile. You start breaking one or two pieces, and the entire system can break, and it may not come back.”

Bradley Parry is the vice chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. According to Parry, any decisions regarding public lands should first consider the tribes.

“The first line of federal property, if it’s going to go to someone, should go to the tribes,” Parry said. “But as long as our federal and trust land is protected, we’ll work with Utah however they move forward.”

Parry argues imbuing indigenous values into people’s regard for land provides a proper framework for decisions about the land and its preservation. The Shoshone Nation is manifesting some of these values in its Wuda Ogwa project, a full ecological restoration of the Bear River Massacre site.

“Water is life — land is life — and you have to respect all of these things,” Parry said. “We didn’t set out to save the Great Salt Lake in our Wuda Ogwa project, but it’s a byproduct of cultural beliefs and

PHOTO BY Aubrey Holdaway

it’s a byproduct of cultural beliefs and spiritual values we are implementing on our own land.”

While Utah’s lawsuit claimed it “would not directly challenge” federal lands held in trust on behalf of Native American tribes, maps depicting “lands in lawsuit” from the “Stand for Our Land” website do include lands managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, notably the Uncompahgre Reservation. The Ute Indian Tribe filed a subsequent lawsuit in November 2024 asking the state to remove claims on this land.

Later statements from Utah government officials denied any claims to tribal lands. With a long history of broken treaties between governments and Native Americans in mind, however, tribal leaders continue to worry over what these implications could spell for tribal sovereignty.

“When it first came out, we were told this wasn’t going to impact the tribes, but then you start seeing different language and you ask, ‘What’s really going on here?,’” Parry said. “We just need to have a sit down, government to government, and get

some assurance this isn’t going to impact us.”

On Jan. 13, the Supreme Court rejected Utah’s lawsuit, for now upholding federal management over public lands in the U.S.

“The legal arguments Utah has been trying to raise have been rejected for more than 100 years,” Bloch said. “Their real play was that maybe the conservative justices on the Supreme Court would be interested in changing the fabric of the American West.”

Despite the Supreme Court’s decision, the fight over public lands is far from over. Mass federal layoffs and budget cuts have gutted agencies such as the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service, putting public lands protections at risk. A push for “restoring energy dominance” from the second Donald Trump administration aims to revise national monument designations, such as Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase, opening these lands up to mining and drilling.

“We’re calling people to action,” Bloch said. “Let’s make sure that our elected officials know that Utahns support conservation of some of the most important lands in the country, whether that’s Grand Staircase and Bears Ears or wild places in Southern Utah like Labyrinth Canyon and Dirty Devil River.”

Utah’s land is a finite resource — there is only one Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef and Zion. The decisions made about these lands will have implications for some of America’s most unique landscapes for generations to come.

“Generations from the future are going to look back at how we’ve damaged a lot of these lands, and they’re going to regret it because they’re inheriting that damage,” Belmont said. “People looking back from the future would prefer we protect these amazing, unique and intricate ecosystems.”

Editor’s note: Efforts were made to reach Gov. Spencer Cox and the Utah Attorney General’s Office for comment, neither of which responded.

Despite new legislative hurdles reshaping university policies, the Utah State University Chapter of Backcountry Squatters remains steadfast in its mission to create a welcoming and empowering space for women and nonbinary individuals in outdoor recreation.

Kayley Bullock, president of the club, outlined the role the organization serves on campus and nationwide to build an outdoor community for women and nonbinary people to feel welcome.

“Backcountry Squatters builds an inclusive outdoor community by providing opportunities for leadership, personal growth and professional development,” Bullock said. “This is accomplished through chapters that offer events for community, building DEI education and honing technical skills.”

Syd Lenssen, vice president of the chapter, emphasized the support and participation the club has been getting this year despite legislation changes.

“We’ve had a pretty good turnout for events,” Lenssen said. “We’ve had a lot of support, especially with that new ruling and people realizing, like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is important — women getting outside and having a space to feel comfortable.’”

Lenssen said the club is a great outlet for creating long-lasting friendships, and it makes the outdoors a less intimidating space to enjoy.

“This club has been so awesome for me and so many of my friends. A lot of us met through this club our freshman year,” Lenssen said. “It’s been really cool to see those relationships grow through the years, all because of Squatters.”

Lenssen outlined activities the club has done, including several craft nights featuring painting in the park, collages in the Natural Resources Building and friendship bracelet-making.

“We did a sound bath in Grand Canyon cave. We had this lady come up from Salt Lake and did a sound bath, and we did yoga,” Lenssen said. “Last weekend, we did a tailgate up at Beaver and made chili.”

The club has collaborated with others such as Aggie Blue Bikes, the USU Snow Club and the Students For Sustainability Club. They do more hiking and backpacking during the warmer seasons.

“We also did a backpacking trip in October that was so awesome,” Lenssen said. “We had like 17 girls come up to White Pine Lake, and we all hiked in and camped for a night.”

PHOTO BY Claire Ott

While the club continues to advocate and create spaces for women and non-binary individuals outdoors, it’s facing new challenges than it has previously.

“We weren’t receiving any funding from the school anyways, so we’re not going to get dismantled,” Bullock said. “We’re not affected by that, but we did lose spaces that we had on campus, like Women’s Climb Night or trips through the [USU] Outdoor Programs.”

Cree Taylor, associate dean of inclusivity and excellence in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences, explained the process of the new legislation that has affected several clubs around campus. House Bill 261, or the Equal Opportunity Initiatives bill, was passed during the last legislative session.

“What the bill alleges is that diversity, equity and inclusive efforts were actually exclusionary and made people feel bad and weren’t needed and were wasting money,” Taylor said. “In that vein, they said universities cannot have DEI-official anything, so that had to go away. That’s why we use inclusive excellence now, and it also looks a little bit different.”

Because Backcountry Squatters is open to women and non-binary folk only, it can’t exist within the school’s parameters.

“They call it protected identity characteristics, so you can’t have any student resources or clubs or scholarships based on a protected identity characteristic,” Taylor said. “That’s why they closed the Inclusion Center — because the Inclusion Center was offering identity-based support, and the legislature said, ‘You can’t do that.’”

The Utah Statesman has previously reported on HB261 and its effects on students. To learn more about the bill, visit usustatesman.com.

Bullock said managing these changes has been difficult, as the club can no longer use any campus resources.

“We can’t use those spaces unless we pay for it, and we can’t afford to pay for it because we have to earn donations for our club,” Bullock said.

One of the main effects was on the club’s collaboration with OP.

“The Outdoor Programs was meeting with lawyers to make sure that they were doing this correctly because they were so taken aback by the bills being passed,” Bullock said. “It’s not like they don’t want to help support these groups — it’s coming from the state. The university likes these small communities that we have, but because it’s state legislation, it’s out of their control.”

Anna Rupper is an employee with OP but spoke with the Statesman as a student and member of the Backcountry Squatters. She discussed how OP has been affected by the legislative changes and what it means for the Backcountry Squatters.

“HB261 affected governmental programs from having gender-exclusive activities and events,” Rupper said. “They can no longer do Wild Women’s trips, and they can’t do certain collaborations with clubs. Anything that was specified towards a certain group, they can no longer offer.” Before the changes, Women’s Climbing Night was held once per week in the ARC.

“They designated three hours once per week to women and non-binary people to come and learn how to climb,” Bullock said. “The rest of the time, it’s just open to the public, and most of that time is filled with men or other people, so it’s kind of hard to feel comfortable as a beginner when everybody there already seems so good.”

The club also hosted a backcountry ski trip every year through OP with the goal of helping women learn how to backcountry ski and feel comfortable in that space.

“The bill just took us back three steps,” Bullock said. “I felt like we were

really going in a good direction where women really found their space and felt comfortable doing whatever, not even just related to the outdoor community — literally anything with womanhood. The step was taking us so far back — like, medieval.”

Lenssen said the last backcountry ski

trip the club took before the legislation changes took effect had a massive turnout.

“We had like 25 girls come out and ski, and for a bunch of them, it was their first time,” Lenssen said. “We can’t do that anymore. I backcountry ski, but I don’t

know if I feel comfortable enough to take a group of people out that don’t know anything. That’s kind of where the OP was really awesome to take over the leadership part of it.”

Rupper expressed her frustration as a club member, emphasizing the important resources OP was able to provide before their collaboration was discontinued. OP trip leaders have medical certifications and experience, which provided a way for the club to safely try new and different outdoor activities.

“It’s often hard to find a place to learn a new activity and be safe in the outdoors, especially as a newcomer and for friends that I know that are new to the outdoors,” Rupper said. “Being able to collaborate with the Outdoor Programs helped. There was good and safe leadership, and it provided a lot of gear and a lot of opportunities that would be hard to come by with just a student-run club.”

While the OP can no longer work with the club, Backcountry Squatters continues

to get individual support. Bullock emphasized the male support the club receives, especially from members within the outdoor community.

“A lot of the male OP trip leaders and staff are also a really great support for us because they also understand that there are struggles for us women, and they also want to help promote our spaces and help us feel more included,” Bullock said. “The outdoor community in general is super inclusive, so we don’t want to shut down anybody that’s trying to get outside and learn to be happy.”

The goal is for the club to step in on campus and fill the space OP left behind as legislation prevents it from serving identity-exclusive groups.

“That’s kind of been our aim this year and especially this semester,” Lenssen said. “Just really go all in with creating these spaces for women because the state is literally shutting us down from doing it.”

The club posts about upcoming activities under their Instagram handle

@backcountrysquatters_usu, and information about the nonprofit can be found at backcountrysquatters.org.

“We can still keep promoting women in the outdoors and connection and just keep building, growing and keep fighting,” Bullock said. “Keep fighting the system so that we can have our spaces and feel comfortable doing the things that we love outside.”

MALORY RAU

The Colorado blue spruce was named Colorado’s state tree in 1939. When it was discovered the oldest living blue spruce was actually in Utah, researchers were surprised to say the least.

Standing just outside Cedar City at Cedar Breaks National Monument, “Old Blue,” a nickname from its discoverers, is estimated to be 457 years old.

In the summers, students, volunteers and field crews go out and survey trees for Utah State University.

Old Blue’s discovery was completely accidental. USU forest ecology professor Jim Lutz explained how the tree was discovered by random tree-ring sampling.

“It just looks like a tree. It’s not even very big. A lot of times, old trees just get fat. They might not be tall, so it was just one of the ones we sampled and we checked,” Lutz said. “We think it’s really good that this is the Colorado state tree and Utah has got the oldest one.”

Despite being named Old Blue, there actually appears to be very little blue in this species of trees.

”They’re called blue spruce because they can look blue, but most of the natural ones in Utah are mostly green,” Lutz said.

Old Blue appeared to be “hiding among Engelmann spruce,” according to an academic article by Lutz with fellow contributors Joseph Birch and Justin DeRose. Its age is a telling sign of how its presence has affected the health of the forest.

“It may be advantageous to plant some blue spruce when restoring an Engelmann spruce forest. Blue spruce are more resistant to beetle attacks and have similar climate requirements,” the article states.

Lutz’s recent research has been covering the impacts of climate change in forestry specifically, such as Utah’s susceptibility to droughts. Most trees have grown to withstand Utah’s temperatures even with ongoing climate change, but they are extremely sensitive to droughts, according to Lutz. Old Blue provided much insight to this research.

”Old trees give us information on how much they’ve grown, so they’re really important for understanding past climate or past forest conditions, but old trees are also survivors,” Lutz said. “We assume their genetics are good because they’ve had to go through all these hard times in the past. If we can identify the old — doesn’t have to be the oldest — trees, then maybe they have good genetics and their seeds would be things we want to collect and propagate.”

Lutz has been researching how warmer temperatures are affecting trees due to an insect called the bark beetle. Warmer temperatures have led to an increase in the population of this particular beetle and an outbreak that’s killed a lot of trees, but the Colorado blue spruce species remains insusceptible, thus making it a tree to keep an eye on as it could become more dominant in Utah as conditions shift.

The whole team behind Old Blue’s discovery was elated to have the oldest Colorado blue spruce ironically be discovered in Utah.

“We need to talk some serious smack to those forestry people at Colorado State,” Lutz said.

ELLA STOTT

Astretch of U.S. Highway 40 known for frequent wildlife collisions is getting a safety upgrade. With $9.6 million in federal funding secured in January, the Utah Department of Transportation and the Division of Wildlife Resources are working together to implement and retrofit safety improvements to protect both motorists and migrating animals.

The federal grant funds infrastructure in rural communities, and the improvements will take place between Starvation Reservoir and Strawberry Reservoir in Duchesne and Wasatch Counties. According to Matt Howard, UDOT natural resource manager, three considerations led to the selection of this area.

“We have a lot of color data from our partnership with the Division of Wildlife Resources, and those colors send out a signal up to every two hours, and so it gives us very precise data about what animals are doing in that area,” Howard said. “We also have a lot of carcass removal contractors who pick up carcasses, and they add the points to an app that we use to track, and we have crash data from law enforcement.”

Alongside meeting the guidelines of the grant, Howard said this rural spot showed a real need for the improvements.

“It is a hot spot for collisions and also a barrier for wildlife movement,” Howard said. “Anytime you build a road between a habitat, you’re going to have animals that are trying to move around.”

According to the UDOT website, 60% of the crashes in the area over the last seven years have involved animals. Howard said the danger for the animals is furthered by the type of vehicles frequenting the highway.

“This is a major corridor for oil trucks going from the Uintah Basin, where there’s a lot of oil and gas exploration, to Salt Lake, where the refinement happens,” Howard said. “So we had all these oil trucks continuing pretty steady traffic, and they’re not able to swerve or slow down for animals.”

Howard said the oil traffic in the area is projected to double in the next 10 years, which created urgency behind the project.

The funding will be used to build 23 miles of eight-feet-tall fencing along the highway,

retrofit three existing underpasses and add one new underpass.

“Although wildlife fencing without wildlife crossings can be a big barrier to movement, and 23 miles is a lot of fence, there are going to be some very specific targeted areas where the one wildlife crossing structure is going to be installed, and then those other existing structures will be fenced to,” said Makeda Hanson, DWR wildlife mitigation initiative coordinator. “That will really focus animals to those areas.”

According to Hanson, the three existing underpasses are being updated in order to make it easier for wildlife to recognize them as safe and use them.

“Wildlife crossings can be scary for wildlife to use, especially initially — and so trying to remove any unnecessary obstacles to wildlife to help them,” Hanson said. “Some of the plans are just to fix some of the substrates on the wildlife crossing so it’s a little bit more approachable for wildlife — so smoothing out the dirt on the bottom a little bit or just adding that fencing to the sides to make sure the animals know that that’s a good place to cross.”

Hanson said the highway is a barrier between habitat and wildlife, but there are other risks without the fencing and underpasses.

“With wildlife-vehicle collisions, there’s a higher proportion of reproductive females that are healthy that are getting killed on roadways than other types of mortality that our deer are experiencing,” Hanson said. “It’s really important for us to try and make sure that we’re protecting that part of the population that’s really leading to healthy, productive populations.”

According to Howard, another risk without the improvements is some animals won’t even attempt to cross the road.

“That’s shown in our data in multiple different locations — that the majority of animals when approaching a road will never even attempt to cross it,” Howard said. “So,

if you have a good habitat surrounded by two or three roads, that habitat may never be accessed by animals, and that’s a loss for the herd, and that’s a loss for people who like to see animals, and it harms their ability to survive harsh winters.”

According to Hanson, avoiding the structures is important for wildlife to use them and understand they’re safe.

“Try and avoid human activity near those structures. If there’s a lot of activity from hiking or whatever other human activities there are, that could discourage wildlife from using those areas,” Hanson said. “So, if you can avoid those, that would be best, especially during the fall and spring when we see a lot of migration.”

This isn’t the first project UDOT and DWR have taken on recently to improve wildlife safety across the state. Most recently, in 2023, UDOT was awarded around $5.5 million to construct new underpasses and

fencing in Kanab along U.S. Highway 89.

“We call it a wish list: projects that we think are pretty shovel ready — that we could implement a project right away if we got the money,” Howard said. “That’s something that we present to the state legislature every year, and it’s something that we work together with the Division of Wildlife Resources to come up with.”

Moving forward, UDOT and DWR hope to secure funding to work at the Echo junction, where Interstate 80 and Interstate 84 meet by Echo Reservoir.

“That’s one the bigger hot spots in the state, and it’s where we think we have some good ideas of how we can resolve the problem,” Howard said. “We just need the funding to do it.”

Hanson encouraged Utah residents who want to help the process to download the Utah Roadkill Reporter app, available for iPhone

and Android users.

“If you see a road kill, if you can safely record that, or once you arrive at your destination, you can record the animal and put an approximate location on a map,” Hanson said. “That really helps us understand where those hot spot areas are, so where we’re seeing the highest number of collisions, to try and prioritize an area specifically for wildlife crossing.”

Howard also suggested interested residents write to or call the state legislature.

“Let them know that this is something your community is very passionate about,” Howard said. “When we think about putting these crossings in, it’s not just public safety or worrying about the number of animals that actually get hit. We’re also just trying to grow bigger, healthier populations of animals in our state.”

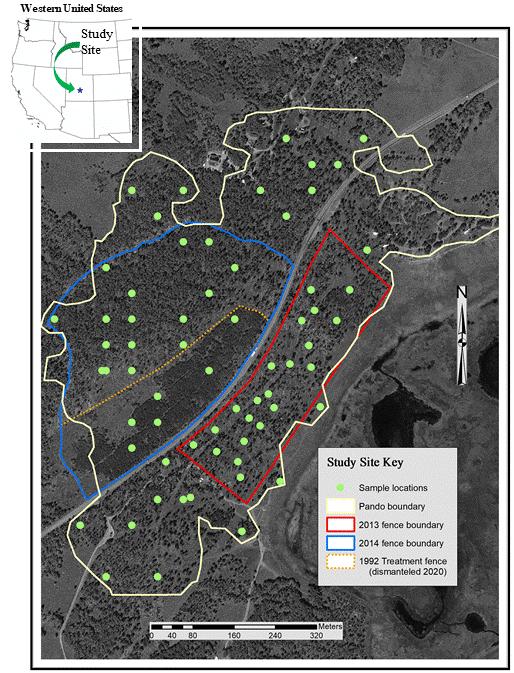

All trees start out as a single seed, but not all trees become Pando, a quaking aspen clone in Utah’s Fishlake National Forest. Over thousands of years, it has grown to span over 106 acres with an estimated 47,000 genetically identical trees.

“It’s been around a long time — certainly centuries if not millennia,” said Paul Rogers, ecologist and director of the Western Aspen Alliance.

According to the United States Forest Service, when the Pando clone was discovered, scientists named it a Latin word that means “I spread.” Pando is an aspen clone that originated from a single seed and spreads by sending up new shoots from the expanding root system.

“Pando is believed to be the largest, most

dense organism ever found at nearly 13 million pounds,” according to the Forest Service. First recognized by researchers in the 1970s, it has more recently been proven by geneticists.

Aspens are known for their clonal growth, meaning what appears as a forest of trees is, in fact, a single interconnected organism.

“What we think of as a tree is really kind of a branch,” Rogers said. “The part sticking above ground is only a small part of this larger organism, which is this vastly connected root system.”

Pando’s size and resilience make it a symbol of nature’s endurance. Yet, despite its longevity, the giant clone is in decline.

“If something’s been around for thousands of years and in the last 50 or 75 years, it starts dying off rapidly,

clearly, that points the finger back at how we as human beings are interacting with it,” Rogers said. The primary threat to Pando’s survival comes from an overabundance of deer due to the eradication of natural predators to regulate their populations. When unchecked, deer feast on the young aspen shoots, preventing regeneration.

According to the non-profit Friends of Pando, “The problem with deer, and elk is their preference for eating the stems of new growth and sometimes nibbling on old growth. These action hinders Pando’s ability to keep energy production and regeneration in balance as the new growth either dies, or is unproductive throwing energy production out of balance. When deer or elk eat at the bark of mature trees, they can leave scars which create pathways for diseases and other animals to destroy healthy branches.”

While cattle grazing has also impacted the ecosystem, Rogers emphasized deer pose the greatest challenge.

“All the young ones keep getting eaten, and then you have this giant gap — the tall ones and nothing in between,” Rogers said. “It’s like if you walked into town where everyone was 85 years old. That’s not a very sustainable demography.”

Fencing has been implemented in certain areas to protect the clone, leading to promising regrowth. However, fencing is a temporary solution that fails to address the core issue.

“I call it Pando triage,” Rogers said. “It’s like getting a patient breathing again. But then what? The real issue remains. There are too many animals.”

Aspens are a keystone species in many forest ecosystems. According to the Forest Service, “aspen communities are found associated with a diverse range of vegetation, from semi-arid shrublands to wet, spruce-fir forest… The aspen ecosystem is rich in number and species of animals, especially in comparison to associated coniferous forest types.” This means their health has a cascading effect on the plants and animals around them.

Natural fire suppression is another issue for Pando’s regeneration. Aspens have a unique reproductive strategy largely dependent on disturbances like fires. When mature stems are damaged or destroyed, the root system sends up new shoots, rejuvenating the forest.

“Aspens are built for resilience but only if we allow the natural processes to occur,” Rogers said. “Without those disruptions, Pando becomes vulnerable.”

Efforts to restore balance in the ecosystem will require cooperation among federal agencies, state wildlife managers and local communities.

“In some way, we need to limit the number of animals that live in that area, but that’s a hard thing to do,” Rogers said. “Ideally, we want the system to run on its own. That’s what our target should be.”

Rogers proposed a variety of measures from selective deer culling to exploring the reintroduction of predators. Though controversial, such measures are essential to maintain Pando’s long-term health.

“Ignoring the core problem for a quick and expeditious fix now often makes the problem bigger down the line,” Rogers warned. “Like climate change or some of the other big issues, we’re pushing it on to somebody in the future, and that doesn’t seem ethical to me.”

Pando has become a focal point for scientific research. Ecologists like Rogers are studying the impacts of different management strategies to determine the most effective long-term solutions. By monitoring the growth of fenced and unfenced areas, researchers can gather crucial data to inform future conservation efforts.

“Science gives us the tools to understand what works and what doesn’t, but it’s up to policymakers and the public to put that knowledge into action,” Rogers said.

Public engagement is also vital. Rogers encouraged visitors to experience Pando firsthand and connect with the landscape. His involvement in the recent PBS documentary on Pando highlighted the importance of storytelling in fostering appreciation and understanding.

“We do really care about these places, and if we can impart even a little bit of that to people, then hopefully you can make some positive improvement,” Rogers said. “We’re looking to make those connections so that people care about places because ultimately, it affects us, right?”

Educational initiatives, guided tours and interpretive signage are all part of ongoing efforts to raise awareness about Pando’s plight. By fostering a greater understanding of its ecological role, conservationists hope to inspire broader support for preservation efforts.

Ultimately, Pando’s future depends on a collective effort. Whether through policy changes, public advocacy or conscious land management, the choices made today will determine if this trembling giant continues to endure for centuries to come.

For more information on how to visit Pando and support its conservation, visit the Forest Service website or consider contributing to local preservation efforts.

If Utah needs to sidestep a major, deadly fire, Utah State University will play a crucial role.

The Utah Forest Restoration Institute, housed in USU’s S.J. & Jessie E. Quinney College of Natural Resources, was launched using state funding in 2024 to synthesize science on forest health, develop a resource hub, monitor vegetation shifts and train students in modern practices. It emphasizes curbing the escalating fire threat through research and teamwork with state and federal agencies.

“Fire is a natural part of our ecosystems, and without that regular fire, we’ve had a lot of changes to our forests,” said Larissa Yocom, director of UFRI.

Wildfires burned 8.9 million acres across the U.S. last year, a figure reported in a Feb. 2 Statista publication, marking a more than threefold increase from the previous year. In Utah alone, state data shows 50,170 of those acres were scorched.

“We have a century of fuel buildup in our forests because we’ve been suppressing fire for decades when, in fact, most of our forests are fire-adapted,” Yocom said.

Utah saw 961 fires in 2024, of which 57% were human-caused. Logan’s hillsides remain among the most vulnerable areas in the state.

“Sometimes people don’t like to hear about it, but climate change is another big thing,” Yocom said. “Even if we didn’t have that buildup of fuels, we also have hotter, drier seasons, and something that’s just indisputable is that our fire seasons are getting longer.”

The unpredictability of wildfires only heightens the fear they inspire.

“No city is safe from wildland fire,” said Robert LaCroix, assistant chief of fire operations for the Logan City Fire Department.

LaCroix, who brings 33 years of experience battling blazes from California to Utah, was “on the initial attack” of the 2018 Paradise fire, which

said, highlighting the trade-offs that complicate these efforts.