Pantomath

Ustinov College’s Scholarly Journal 2022-23

Contents

Introduction

Principal’s Introduction p 4

President’s Letter p 5

STEM

Alternative Equivalents of the Human Skin: The Revolution of Skin Damage Study p 6-7

Development of Soft Robotic Endoscopy As A Powerful Tool For Surgical Innovation p 8-9

Diagnosis and Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease: Still A Long Way To Go p 10-11

Psychology

Sick of Study: Student Mental Health and Higher Education Policy p 12-15

A Critical Evaluation of Cronbach and Glesser’s (1957) Bandwidth-Fidelity Dilemma p 16-17

The Internet and Social Sphere

Aliens Built the Pyramids: Ethics of Educating on TikTok p 18-19

Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme Events

Climate FRESK Workshop p 20-21

Digging Deep: Coal Miners of African Caribbean Heritage at Ustinov College, A Perspective On Research Activities

To Improve Cultural Heritage and Diversity Awareness p 22-23

SUCCESS Seminar: Personal Branding and Identity Development p 24-25

Ustinov Annual Conference

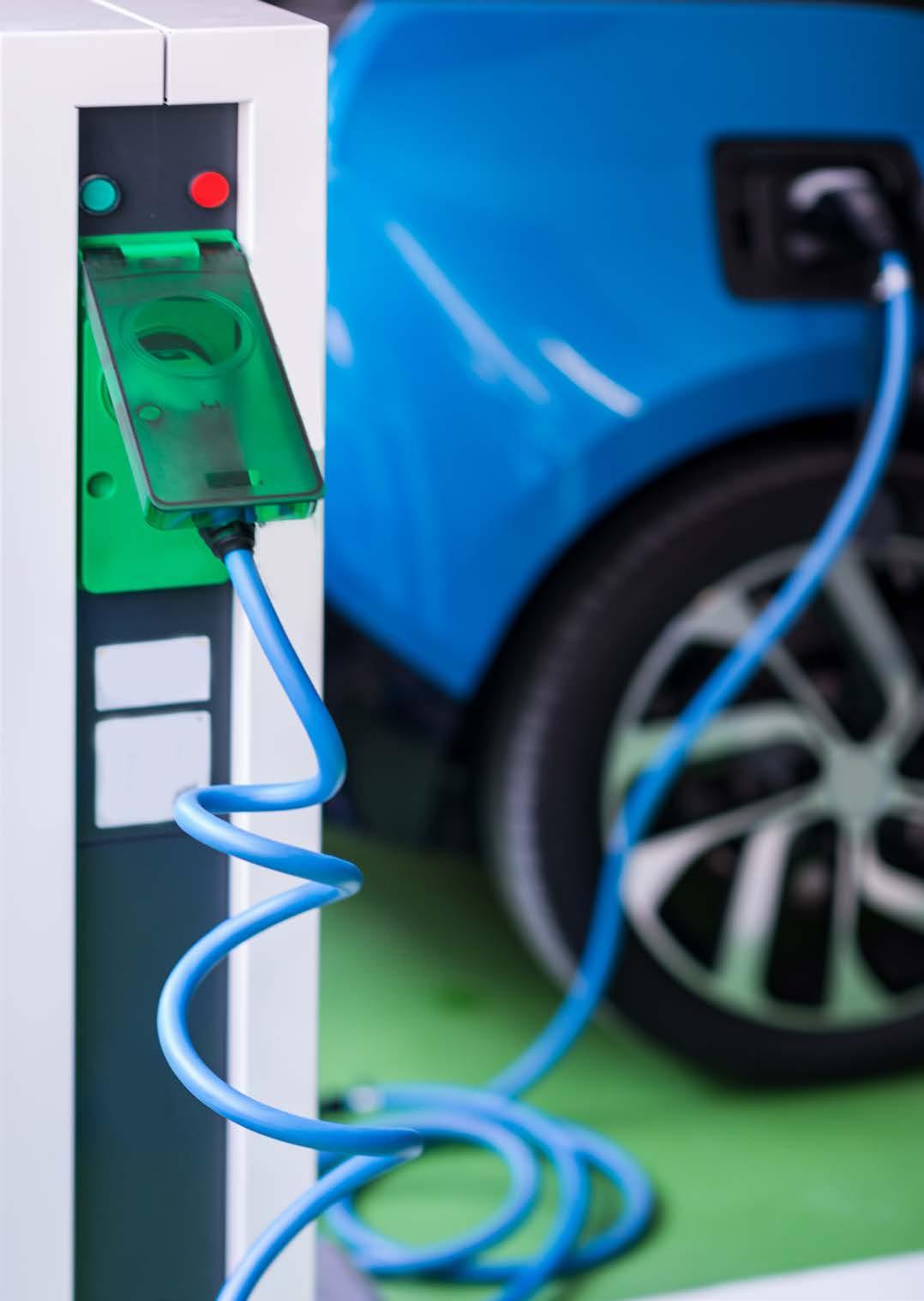

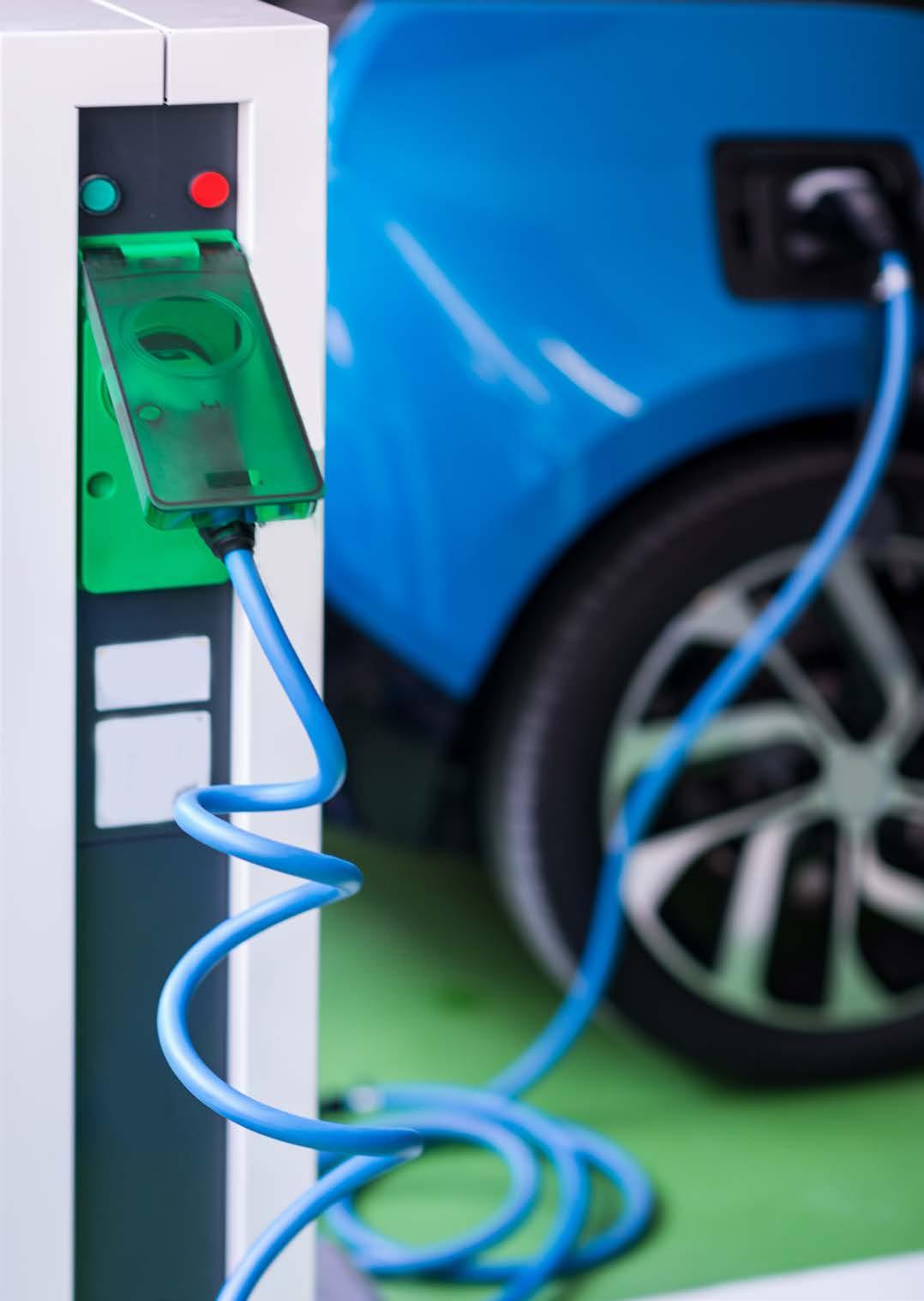

Powering the Future We Want: Global Innovative Approach in Sustainable Energy & Environment Introduction p 26-27

Ustinov Meets: Professor Janet Stephenson p 28-31

Ten Ways To Reduce Your Greenhouse Gas Emissions p 32-33

Editor’s Note

I want to take the time to thank all those who have submitted an article for The Pantomath. It has been a pleasure to read and edit all the amazing articles that have been sent in. I have fully enjoyed reading all the research that has been conducted at Ustinov College this past year.

I want to personally thank the assistant editor of The Pantomath, Izzy Wall, for helping me throughout the editing process. would also like to thank Yuanxi Qin for providing photos for the Global Citizenship Programme events that have taken place over the last year. Lastly, a big thank you to Paula Furness, who has overseen the development of The Pantomath this year and whose guidance has been invaluable for creating every aspect of the journal.

Thank you,

Kate Paterson

Editor Ustinov Pantomath 2022-23

‘The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Ustinov College or Durham University’

CUR/07/23/354 page 2 The Pantomath Ustinov College’s Scholarly Journal page 3

Principal’s Introduction

President’s Letter

Welcome to the 2023 edition of Ustinov College’s scholarly journal, The Ustinov Pantomath!

We increasingly live in a world with a range of worryingly confronting ‘wicked’ problems, such as energy, food and cyber security, anthropogenic climate change, conflict and environmentally driven migration, extreme poverty, gender equality, threats to human health and wellbeing, amongst others. These are ‘wicked’ problems because of their complexity and in many cases interdependence. To understand, explain, and unravel the ‘wickedness’ of these problems, research is required so that evidence-based solutions can be developed across multiple scales from the local to the global.

Ustinov College is very fortunate in having a membership composed entirely of postgraduate researchers at both the Masters and PhD levels with many of our present and past members working towards shedding light on some of the aforementioned global challenges.

The Pantomath, as Ustinov College’s scholarly journal, is just one vehicle through which Ustinovians are able to share the outcomes of their research.

Other avenues include Ustinov’s Annual

Conference and the rich programme of seminars organised under the umbrella of our three ‘Café’ seminar programmes –Scientifique, Politique and des Arts. This tangible research culture, a signature of the Ustinov community, is something we are very proud of!

I trust you will enjoy the rich content contained within the 2023 edition of The Pantomath. This edition is not only the result of the efforts made by the individual contributors who have written articles, but the outcome of the immense amount of time and energy invested, and editorial and design savviness demonstrated by the College’s Media and Publications Team who are part of the broader group of scholars that convene Ustinov’s Global Citizenship Programme of activities.

Do get in touch with the Global Citizenship Programme’s Media and Publications Team if you would like to contribute to future editions of Pantomath.

Best wishes,

Professor Glenn McGregor Professor of Climatology and Principal of Ustinov College

Dear Ustinovians,

As the President of the Graduate Common Room (GCR) of Ustinov College, I am pleased to write to you in the new edition of The Pantomath to express my admiration for the unique relationship between the GCR and the Global Citizenship Programme (GCP). This partnership has exemplified the spirit of collaboration and engagement we strive to cultivate in Ustinov College.

I am incredibly proud of the GCR and GCP for fostering an inclusive and supportive environment that encourages intellectual growth, cultural understanding, and social responsibility. Through these joint efforts, they have not only enhanced the experience of our graduate students but also contributed to the broader goals of our college community.

The Graduate Common Room has been instrumental in creating a vibrant and

welcoming space where students from diverse backgrounds can connect, share experiences, and build lifelong friendships. It has become a hub of intellectual discourse, cultural exchange, and personal development. The GCR has organised numerous events, workshops, and social activities that have enriched the lives of our graduate students and fostered a sense of belonging.

On the other hand, the Global Citizenship Programme has played a crucial role in promoting global awareness and social responsibility among our student body. By offering various opportunities for international experiences, community service, and intercultural dialogue, the GCP has empowered our students to become compassionate global citizens. Their engagement in projects addressing social issues, sustainable development, and cross-cultural understanding has been inspiring.

The collaboration between the GCR and GCP has resulted in an extraordinary synergy that has benefited everyone involved. The GCR has actively supported the GCP’s initiatives by hosting events, providing logistical support, and offering a platform for meaningful discussions. In return, the GCP has provided our graduate students with unique opportunities to expand their horizons, develop leadership skills, and positively impact the world.

I want to express my deepest gratitude to all the individuals who have contributed to the success of this partnership. To the GCR and GCP committee members, your dedication and hard work have been instrumental in creating a harmonious and inclusive community. To the College Management Team, who have supported these initiatives, your guidance and mentorship have been invaluable. And, of course, to the students who have actively participated in GCR and GCP activities, I thank you for your invaluable support. We hope you take many unforgettable memories with you and always remember Ustinov College as the place where you were very happy when you worked so hard to get a postgraduate degree.

As we celebrate the achievements of the GCR and GCP, let us remember that this partnership represents the essence of our college’s values: fostering intellectual growth, embracing diversity, and positively impacting society. I encourage all students to engage with the GCR and GCP, take advantage of the opportunities they offer, and contribute to the flourishing community that they have created.

Together, we can continue to build bridges, nurture global citizens, and make a meaningful difference in the world.

Best wishes,

Joel Lozano Graduate Common Room President 2022-23

Ustinov College’s Scholarly Journal

page 4 The Pantomath page 5

From left to right: Joel Lozano (GCR President) Kate Paterson (Editor of the GCP Pantomath), Teodora Nikolova (GCP Liaison Officer to the GCR and Member of Cafe des Arts) and Jamie Hunter (GCR Clubs and Societies Officer)

Alternative Equivalents of the Human Skin: The Revolution of Skin Damage Study

Skin is the largest organ of humans, and the first barrier to maintain the stability of the inner environment of the human body. Native human skin carries out the defensive responsibilities as the first physical barrier for resistance to most exogenous irritations (such as ultraviolet radiation), providing mechanical protection to underlying tissues and preventing excessive water evaporation from the human body. Apart from physical protections, the skin also performs immunological and chemical functions against pathogens using locally present immune cells - such as T-cells - and their secretions. The skin is composed of three different compartments including epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat. The epidermis, the superficial compartment, plays the core role of the barrier functions outlined above.

The epidermis is frequently exposed to external thermal, mechanical, and chemical stressors which are the main causes of skin barrier damage. Thermal damage is caused by exposure to sources of high temperature, such as flame and hot water. Mechanical damage occurs most frequently from various sources, such as being cut by a scalpel or through the process of shaving. Chemical damage, commonly caused by detergents, is cumulative by taking weeks or months to develop via frequent exposure to the irritants. The degree of damage to the epidermis or entire skin tissue varies and may cause serious infection, prolonged inflammation, and even requirement of a skin graft. Therefore, by understanding the mechanism of the skin barrier damage caused by different exogenous factors, we can investigate effective methods to maintain skin barrier health.

As there are ethical and medical concerns for studying skin barrier damage of the human body, some alternative strategies have been developed during the past couple of decades. Typical approaches

for investigating the mechanism of skin barrier damage and cutaneous wound recovery include a two-dimensional (2D) cell monolayer, ex vivo human skin samples, and animal models. However, almost each strategy has its own limitation in simulating the real situations.

‘The Human Skin Equivalent’ is traditionally assembled by three components including ‘seed cells’ such as keratinocytes and fibroblasts, the ‘soil’, and a 3D scaffold. The scaffold works to support fibroblast growth and secretion to form a dermal structure. It also produces a substrate for keratinocyte growth, allowing for differentiation into a stratified epidermal structure, which closely mimics the status of real human skin compositions.

‘The Human Skin Equivalent’ has been constructed in a bio-science laboratory at Durham University. It is based on the porous scaffold of specific artificial materials which have stable chemical properties and can enhance the reproducibility of produced skin models (Roger et al. 2019). This model is being applied to constructing models of different skin barrier damage types and a study examining a corresponding wound recovery process. They have the potential to simulate the complexity of a real skin wound and further satisfy the test of new medicines for the therapy of skin damage to accelerate their clinical application in the future projects.

This works as a substitute for the traditional strategies mentioned above, as it overcomes most of their limitations by having the potential as an ideal platform for accelerating the study of the mechanisms of skin barrier injuries. This would include studies associated with wound healing and high-throughput screening of medical or cosmetic products for treating skin barrier damage.

STEM

‘The Human Skin Equivalent’ is a type of threedimensional (3D) skin model generated with essential human skin cells outside the human body.

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal page 6 The Pantomath page 7

Peng Feng

Development of Soft Robotic Endoscopy as A Powerful Tool for Surgical Innovation

Yuanxiang Lin

Open surgery is a traditional type of surgery in which an incision is made using a scalpel. The incision in open surgery ranges from 7 to 10 cm to even larger, depending on the procedure being performed. To reduce the size of incision and the pain of patients, techniques of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) are becoming more prevalent. These surgeries use multiple incisions of less than 2.5cm in length. An endoscope and instruments are inserted into these incisions. With the endoscope, the surgeon can observe the procedure on a monitor and perform technical operations remotely from the patient. Different from MIS, Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) makes use of the body’s natural orifice such as vagina or mouth for surgical instruments to be inserted. In both MIS and NOTES, endoscopes are widely utilised to have access to the organ.

In general, endoscopes can be divided into two types: rigid and flexible. Unlike the rigid endoscope, the soft robotic endoscope can circumambulate the obstacle which is intervened between the target object and incision position. The soft robotic endoscope is made by silicone which is compliant to the human body without causing over-sensitive symptoms. Its biocompatibility and elastomeric nature also facilitate the interaction of the soft robotic endoscope with surrounding organs and tissues by not running the risk of damage

(Polygerinos et al., 2017). Its flexibility is generally achieved via pneumatic soft actuators, which are composed of an extensible top layer with neighbouring but independent chambers inside, and an inextensible but flexible bottom layer. The bending of the entire actuator and small changes in the height of the extensible layer are controlled by pumping air into the chambers.

However, there are several issues with the soft robotic endoscope which limit its practical applications. Flexible endoscopes lack the stability in performing surgical intervention due to the lack of stiffness. The localization of the endoscope inside the patient’s body is an additional problem because the view from the endoscope camera is not synchronised with how far the endoscope has gone inside the patient’s body. Another major limitation is that while the distal tip of the soft endoscope can be controlled, the rest of the endoscope cannot.

A soft robotic, multi-module endoscope design, STIFF-FLOP (Stiffness Controllable Flexible and Learnable Manipulator for Surgical Operation), has been studied and tested in lab settings (Cianchetti et al, 2013) to solve limitations of the flexible endoscope. However, it is not suitable for laparoscopy in terms of size. For this reason, it is necessary to downscale the STIFF-FLOP manipulator so that it can be applicable for laparoscopic application.

To assess the developed module, system characterization of the module was completed, and its specific result was utilised as the feedforward signal which was then added into the feedback controller. The combination of feedback and the feedforward controller is then applied in controlling

the bending performance of the module in three different module orientations. No matter if the module is arranged in vertical, inverted, or horizontal module orientations, the feedback and feedforward controller were able to make the module bend to the desired one-plane bending angle at steady state.

References

Cianchetti, M., Ranzani, T., Gerboni, G., De Falco, I., Laschi, C. and Menciassi, A. (2013). STIFFFLOP Surgical manipulator: Mechanical Design and Experimental Characterization of the Single Module. [online] IEEE Xplore. doi:https://doi. org/10.1109/IROS.2013.6696866.

Mosadegh, B., Polygerinos, P., Keplinger, C., Wennstedt, S., Shepherd, R.F., Gupta, U., Shim, J., Bertoldi, K., Walsh, C.J. and Whitesides, G.M. (2014). Pneumatic Networks for Soft Robotics That Actuate Rapidly. Advanced Functional Materials 24(15), pp.2163–2170. doi:https://doi. org/10.1002/adfm.201303288.

Polygerinos, P., Correll, N., Morin, S.A., Mosadegh, B., Onal, C.D., Petersen, K., Cianchetti, M., Tolley, M.T. and Shepherd, R.F. (2017). Soft Robotics: Review of Fluid-Driven Intrinsically Soft Devices; Manufacturing, Sensing, Control, and Applications in Human-Robot Interaction. Advanced Engineering Materials 19(12), p.1700016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ adem.201700016.

STEM

page 8

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

The Pantomath page 9

In our study, a new module of soft robotic endoscope has been developed based on a survey, with a diameter which is less than half of the traditional STIFF-FLOP manipulator and satisfies the standard of MIS application.

Diagnosis and Therapy of Alzheimer’s Disease: Still A Long Way to Go

Yunxi Zhang

Alzheimer’s disease is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases, affecting more than 15 million people globally. Alzheimer’s disease affects mostly people over the age of 65, indicating that ageing is an important factor in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease was first identified by Alois Alzheimer, a psychiatrist whose patient presented progressive cognitive decline. The “peculiar substance” he detected in the diseased brain is called amyloid plaque which is an extraneuronal accumulation. This is one of the neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, the other is when intraneuronal ‘Neurofibrillary Tangles’ are identified in the temporal lobe of the brain. Amyloid plaques are made up of aggregated Aβ peptides. Experiments have shown that the activity of neurons will cause amyloid precursor protein (APP) to process into Aβ, and the increase of Aβ will also inhibit the transmission of excitatory synapses and inhibit the activity of neurons. Therefore, the normal amount of Aβ can be used as a negative feedback signal in the nervous system to maintain the stability of neuronal activity.

The overexpression of Aβ will reduce the density of spinous processes, causing structural and synaptic abnormalities to neurons. Another neuropathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is Neurofibrillary Tangles which are made up of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. The normal structure of tau is a neuronal protein that can promote the assembly of microtubules. Tau works with the other two microtubule-associated proteins (MAP): MAP1(A/B) and MAP2. They

have similar structures and can replace each other. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau is abnormally hyperphosphorylated, forming insoluble fibrils, causing tangles of nerve fibres and microtubules to dissemble, this process is directly related to the development of dementia. Neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial damage are triggered by the accumulation of these protein aggregates, resulting in the death of neurons and the loss of white matter in the brain. The loss of synapses and amyloid angiopathy are also found in Alzheimer’s disease brains.

Although there is currently no effective cure for Alzheimer’s disease, there are still some drugs used to relieve the symptoms. The type of drug currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease are acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs), which mainly include donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine. These drugs have been clinically proven to be effective against Alzheimer’s disease, and their side effects in the gastrointestinal tract have improved in recent years. The only drug approved by Europe and the United States for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease is a low-affinity voltage-dependent uncompetitive antagonist to glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors called Memantine Hydrochloride (MEM). Memantine is combined with open NMDA receptor-operated calcium channels preferentially to prevent neuronal dysfunction caused by increased glutamate levels. However, the efficacy of Memantine seems not very significant, and it can cause side effects such as dizziness and constipation. To combat this there has been a recent modification of the dosage form of Memantine.

STEM

page 10 The Pantomath The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

page 11

Sick of Study: Student Mental Health and Higher Education Policy

Michael Priestley

This paper applies Foucaultian theory to conceptualise student mental health and wellbeing within a political sociological framework of higher education policy discourses and structures.

Context

Student mental health is a growing public and political concern. UK students consistently record lower on wellbeing outcomes than both the equivalent nonstudent population (Thorley, 2017) and their international peers (Broadbent, 2017). Whilst a highly complex and contested phenomenon (Wykes, 2015; RCP, 2011), current research, policy, and practice has arguably coalesced around two core themes of consensus (Byrom, 2018).

First, the number of students reporting mental distress is significantly increasing (RCP, 2011), with five times more students now disclosing mental health conditions at university than a decade ago; there has been a 210% increase in student attrition for mental health reasons (Thorley, 2017).

It is estimated that 33% of students report clinical levels of distress (Beswick et al., 2008); meaning a third of students would pass a clinical threshold to be diagnosed with a mental health difficulty. Recurring concerns are the prevalence of stress, anxiety, low mood, loneliness, and sleep deprivation among students (UUK, 2018; HEPI, 2017; NUS, 2017; Student Minds, 2016; Auerbach et al., 2016; IES, 2015), whilst these risks are felt disproportionately among marginalised groups, namely LGBTQ+ (Student Minds, 2018); BME (Arday, 2018); International (UUK, 2016; Chen et al., 2015); Working Class (Gutman et al., 2015); Mature and Postgraduate (Evans et al., 2018) students.

Second, the demand for university wellbeing services is rapidly increasing (Broglia et al., 2017), with 61% of university counselling services reporting an increase in demand of over 25% over the last five years (Thorley, 2017). At some institutions, 1 in 4 students are either being seen or waiting to be seen by the counselling

service (ibid). It is estimated that 75% of students experiencing mental health difficulties do not receive professional support (MHT, 2016; Auerbach et al., 2016). The distinctive student mental health risk factors, reliable measures, and effective support strategies implicated by these themes remain widely contested (Fernandez, 2016; Wykes, 2015).

Introduction

It is imperative, given the emotive and contested nature of the field, to clarify the linguistic and conceptual parameters and scope of this proposition. This paper conceptualises mental health on a continuum from mental wellbeing to mental health difficulties. On this continuum, any student, when faced with

preventative structural policy changes and by integrating timely and appropriate support, the university can provide a key and strategic site to both reduce risk and maximise protective wellbeing factors to promote better mental health, wellbeing and ultimately learning for all (UUK, 2018).

The Political Economy of Student Mental Health

It is helpful to initially identify three core theoretical approaches to conceptualising student mental health and wellbeing.

First, the biomedical approach, which conceptualises mentally ill health as an internal pathology, mediated by certain genetic risk factors, whereby accurate diagnosis and effective drug therapy are

in interaction in any given case (Lehman, David & Gruber, 2017), the scope of this paper is concerned with emphasising the socio-political lens and exploring how the financial, social and academic pressures that students face impact student mental health and wellbeing.

A Foucaultian Model of Student Mental Health

This paper proposes that a Foucaultian framework of higher education discourse, truth, power and the subject is useful for conceptualising the external and internal dimensions of the relationship between higher education policy and student wellbeing. The theoretical rationale is summarised as follows.

First, for Foucault (1979), socio-political power produces the discourses that count as truth in higher education policy, by which policy then (re)produces these same socio-political power relations. Second, Foucaultian subjectivity, or simply individual beliefs, behaviours and identity, are (re)produced both externally ‘by control or dependence’ (Foucault, 1982, p. 212) and internally by a conscience or selfknowledge (ibid). In sum, socio-political ideology discursively produces and enacts through policy a certain reality of higher education that frames and constrains student subjectivity and wellbeing both externally and internally (Ball, 2013; 2012).

A Foucaultian Model of Student Mental Health and Higher Education Policy

The theorised impact on mental health and wellbeing is explored, in this paper, through the illustrative example of the 2010 three-fold increase in university tuition fees (BIS, 2010). At an external socio-material level, there is a wealth of evidence to suggest that financial hardship, insecurity, and debt are strongly associated with poorer mental health and wellbeing (McCloud & Bann, 2019; Winter et al., 2016; Bambra & Schrecker, 2015; Mattheys, 2015; Bragg et al., 2015). Yet, at an internal socio-psychological level, it is proposed that a market understanding of higher education in policy as a private commodity to be invested in, accumulated, and exchanged for employment and wealth, inherently promotes mentally unhealthy study and social beliefs, behaviours and patterns (Hall & Bowles, 2016; Berg et al., 2015). Once (re)situated within structures of individual and instrumental competition, students can internalise and (re) enact policy systems of assessment, competition and comparison in their own value judgements, self-identification, and self-worth (Loveday, 2018; Ball & Olmedo, 2013; Ball, 2012). As such, students feel responsible to self-discipline their own competitive performance and productivity (Ward, 2017; Ball, 2013; 2012) entrenching a culture of intense perfectionism (O’Flynn & Petersen, 2007 & Smith, Smeyers & Standish, 2006), and associated stress, anxiety, low mood and loneliness (Stober & Joorman, 2001). Neo-Marxist critics have argued, by extension, that this stress and anxiety is both produced and reproduced as a symptom and tactic of neoliberal governmentality; a (self-) disciplinary mechanism that is productive of the ideal ‘docile and capable’ (Foucault, 1979, p.294) politico-educational subject that is ultimately responsible, competitive, and productive within the economic demands of the neoliberal institution (Loveday, 2018 ; Berg et al., 2016; Hall & Bowles, 2016; Rose, 1996).

Conclusion

the challenges and stresses of university life, can experience periods of poor mental wellbeing without necessarily having a diagnosed mental health difficulty. Prolonged poor mental wellbeing can however, in the absence of appropriate help or support, create conditions that may lead to the development of mental health difficulties, or exacerbate existing mental health difficulties. Equally, with the right help and support, those with enduring mental health difficulties can still experience good mental wellbeing. The implication, I suggest, is that university conditions can contribute to poor wellbeing and thus increase risk of students developing mental health difficulties, with the acknowledgement that not all mental health difficulties are solely caused or alleviated by university policy. Thereby through

paramount to effective outcomes (Bentall, 2009).

Second, the psychological approach, which emphases psychological interventions to identify and challenge self-destructive psychosomatic thought and behavioural patterns and equip the individual with the tools to make mentally healthy choices (Seligman, 2004).

Third, the socio-political epidemiological approach, which seeks to identify the social, political, and economic determinants of mentally ill health (Bambra & Schrecker, 2015; Cohen & Timimi, 2010; Ingleby, 1980).

Whilst increasingly policy and practice guidance has adopted a biopsychosocial approach which conceptualises biological, psychological, and sociological factors

This paper has introduced a Foucaultian socio-political epidemiological framework for conceptualising student mental health and wellbeing in the context of higher education policy. The author argues that this insight may have potentially significant future implications, through further research, for elucidating preventative and holistic higher education policy changes to benefit student wellbeing (UUK, 2018).

Psychology

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

“The anxiety currently manifest in higher education is not an unintended consequence or malfunction but is inherent in the design of a system driven by improving productivity.”

(Hall and Bowles, 2016, p. 33).

page 12 The Pantomath page 13

Sick of Study: Student Mental Health and Higher Education Policy

References

Arday, J. (2018). Understanding Mental Health: What are the Issues for Black and Ethnic Minority Students at University? Social Sciences 7(1), 196.

Auerbach, R., Alonso, J., Axinn, W., Cuijpers, P., Ebert, D., Green, J., Mortier, P. (2016). Mental Disorders among College Students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychological Medicine 46(14), pp. 2955-2970.

Ball, S. (2012). The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity. Journal of Educational Policy 18(2), 215-228.

Ball, S. (2013). Foucault, Power and Education

London: Routledge.

Ball, S., & Olmedo, A. (2013). Care of the Self, Resistance and Subjectivity under Neoliberal Governmentalities. Critical Studies in Education 54(1), 85-96.

Bambra, C., & Schrecker, T. (2015). How Politics

Makes Us Sick: Neoliberal Epidemics New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bentall, R. (2009). Doctoring the Mind: Why Psychiatric Treatments Fail London: Allen Dale. Berg, L.., Huijbens, E. & Gutzon-Larsen, H. (2015). Producing Anxiety in the Neoliberal University. The Canadian Geographer, 60(2), pp. 168-180.

BIS [Department for Business, Innovation and Skills], 2010. The Browne Report: Higher Education Funding and Student Finance. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/the-browne-report-highereducation-funding-and-student-finance [Accessed 06 November 2018].

Bragg, J., Burman, E., Greenstein, A., Hanley, T., Kalambouka, A., Lupton, R., McCoy, L., Sapin, K., & Winter, L. (2015). The Impacts of the ‘Bedroom Tax’ on Children and Their Education: A Study in the City of Manchester. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Broadbent, E., Gougoulis, J., Lui, N. Pota, V. & Simons, J. (2017). What the World’s Young People Think and Feel. Generation Z: Global Citizenship Survey, Varkey Foundation. Available from https://www.varkeyfoundation.org/ media/4487/global-young-people-report-singlepages-new.pdf [Accessed 06 November 2018].

Broglia, E., Millings, A. & Barkham, M. (2017).

Challenges to Addressing Student Mental Health in Embedded Counselling Services: A Survey of UK Higher and Further Education Institutions, British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 46 (4), pp.441-445.

Byrom, N. (2018). Academic Perspective: Research Gaps in Student Mental Health. What Works Wellbeing Blog Available from https://whatworkswellbeing.org/blog/academicperspective-research-gaps-in-student-mentalhealth/

Chen, J., Liu, L., Zhao, X., Yeung, A. (2015). Chinese International Students: An Emerging Mental Health

Cohen, C., & Timimi, S. (2010). Liberatory Psychiatry: Philosophy, Politics, and Mental Health Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crisis. Journal of Child Adolescent Psychiatry 54(11), pp. 879-80.

Evans, T., Bira, L., Gastelum, J., Weiss, L. & N. Vanderford (2018). Evidence for a Mental Health Crisis in Graduate Education. Nature Biotechnology 36 (1), pp.282-284.

Fernandez, A. (2016). Setting-Based Interventions to Promote Mental Health at University: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Public Health, 61 (1), pp.797-807.

Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and Civilisation: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason New York: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison New York: Pantheon Books.

Gutman, L., Joshi, H., Parsonage, M., & Schoon, I. (2015). Children of the New Century: Mental Health Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study London: Centre for Mental Health.

Hall, R. & Bowles, K. (2016). Re-engineering Higher Education: The Subsumption of Academic Labour and the Exploitation of Anxiety. Workplace, 28 (1), pp. 30–47.

HEPI [Higher Education Policy Institute], 2017. The Invisible Problem? Improving Students’ Mental Health Accessed via https://www.hepi. ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/STRICTLY-

EMBARGOED-UNTIL-22-SEPT-Hepi-Report-88FINAL.pdf

IES [Institute for Employment Studies], 2015. Independent Report to HEFCE: Understanding Provision for Students with Mental Health Problems and Intensive Support Needs. Available from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov. uk/20180319114953/http://www.hefce.ac.uk/ pubs/rereports/year/2015/mh/

Lehman, B., David, D., Gruber, J. (2017). Rethinking the Biopsychosocial Model of Health: Understanding Health as a Dynamic System, Social and Personality Psychology Compass 11 (8), pp.11-28.

Loveday, V. (2018). The Neurotic Academic: Anxiety, Casualisation, and Governance in the Neoliberalising University. Journal of Cultural Economy, 11 (2), pp.154-166.

Mattheys, K. (2015). The Coalition, Austerity and Mental Health. Disability & Society 30(3), pp. 475-478.

McCloud, T. & Bann, D. (2019). Financial Stress and Mental Health among Higher Education Students in the United Kingdom up to 2018: A Rapid Review of Evidence (Pre-print version available at: https://psyarxiv.com/35djy.)

MHT [Mental Health Taskforce], 2016. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health. A Report from the Independent Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS. Accessed via https://www.england.nhs. uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Mental-HealthTaskforce-FYFV-final.pdf

NUS [National Union of Students], 2017. NUS-USI Student Wellbeing Research Report. Available from: https://nusdigital. s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/document/documents/33436/59301ace47d6320274509b83e1bea53e/NUSUSI_Student_ Wellbeing_Research_Report.pdf

O’Flynn, G., & Petersen, E. (2007). The ‘Good Life’ and the ‘Rich Portfolio’: Young Women, Schooling and Neoliberal Subjectification. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(4), 459-472.

RCP [Royal College of Psychiatrists], 2011. Mental Health of Student in Higher Education. Mental Health of Students in Higher Education

Accessed via https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/ default-source/improving-care/better-mh-policy/college-reports/college-report-cr166.pdf?sfvrsn=d5fa2c24_2

Rose, N. (1996). Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seligman, M. (2004). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realise Your Potential for Lasting Fulfilment. New York: Simon & Schuster Ltd.

Smith, R., Smeyers, P. & P. Standish (2006). The Therapy of Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stober, J., & Joorman, J. (2001). Worry, Procrastination, and Perfectionism: Differentiating Amount of Worry, Pathological Worry, Anxiety and Depression. Cognitive Therapy Research 25 (1), pp.49-60.

Student Minds (2016). Grand Challenges in Student Mental Health Accessed via https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/grand_challenges_report_for_public.pdf

Student Minds (2018). LGBTQ Student Mental Health. The Challenges and Needs of Gender, Sexual Orientation and Romantic Minorities in Higher Education Accessed via https://www.studentminds.org.uk/uploads/3/7/8/4/3784584/180730_lgbtq_report_ final.pdf

Thorley, C. (2017). Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities, Institute for Public Policy Research Available from www.ippr.org/publications/not-by-degrees.

UUK [Universities UK], 2018. Minding Our Future: Starting a Conversation about the Support of Student Mental Health Available from https:// www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/ reports/Documents/2018/minding-our-future-starting-conversation-student-mental-health.pdf

UUK [Universities UK], 2018. StepChange: Mental Health in Higher Education Available from https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/stepchange

[Accessed 06 November 2018].

Ward, S. (2017). Using Shakespeare’s Plays to Explore Education Policy Today: Neoliberalism through the Lens of Renaissance Humanism London: Routledge.

Winter, L., Burman, E., Hanley, T., Kalambouka, A., & McCoy, L. (2016). Education, Welfare Reform and Psychological Well-Being: A Critical Psychology Perspective, British Journal of Educational Studies, 64 (4), pp. 467-483.

Wykes, T., et al. (2015). Mental Health Research Priorities for Europe. The Lancet Psychiatry 2 (1), pp.1036-1042.

Psychology

page 14 The Pantomath page 15

...any student, when faced with the challenges and stresses of university life, can experience periods of poor mental wellbeing without necessarily having a diagnosed mental health difficulty.

A Critical Evaluation of Cronbach and Gleser’s (1957) Bandwidth-Fidelity Dilemma

Evelyn Mary-Ann Antony

Abstract

The bandwidth-fidelity dilemma was devised by Cronbach and Gleser (1957), whereby bandwidth refers to simplicity and fidelity refers to accuracy. Specifically, broad measures (e.g., measures of general cognitive ability) can predict broad criteria (e.g., academic outcomes) with moderate validity, and maximum validity necessitates a higher degree of fidelity between the measure and the criterion (Salgado, 2017). Most research on the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma has been explored in the context of organisational psychology, with a greater focus on job satisfaction and task performance, rather than emotional states and affective symptoms (Hengartner et al., 2016). This discussion paper provides a critical evaluation of the bandwidth fidelity dilemma, (Salgado et al., 2013; Ashton et al., 2014), the implications of the dilemma are discussed, and references to recent research on validity and psychological testing (Soto & John, 2017; Rodrigues & Rebelo 2020).

Key Approaches of The BandwidthFidelity Dilemma

According to Salgado (2017), one of the key approaches in the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma suggests broad personality measures like the Big Five Factor inventory best predict both broad and narrow performance criteria, such as job performance (Ashton & Lee, 2005). The validity of the Big Five Factor traits was investigated alongside those from the HEXACO model (i.e., the same as the Big Five Factor traits but with the additional trait of honesty-humility) (Lee & Ashton, 2004). The research found that facets showed larger validity than the global factors for the prediction of broad and narrow self-reported measures of interpersonal and organisational deviance (Salgado et al., 2015). These findings can be better understood through the practical application of the approach to predicting job performance ratings. Findings showed that conscientiousness predicted both broad and narrow job performance criteria, where the multidimensional nature of job performance did not appear to affect the validity of conscientiousness (Salgado et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the application of this approach has benefits for criterion-related validity, as personality measures are directly related to the outcome, thus being a better predictor of job performance in future research.

The second approach to the dilemma suggests that narrow personality measures (e.g., facet personality scales like the Big Factor Five) predict narrow criteria and explain additional variance (e.g., anxiety) better than broad personality measures (Ashton & Lee, 2005; Salgado, 2017). Broad bandwidth and narrow fidelity within the Big Five Factor model were investigated, and it was found that the narrow measures of personality were able to account for more variance than the broad traits when included alone in a regression equation, and importantly, the facets were able to add incremental prediction when entered with broad trait level factors (Salgado et al., 2015). This highlights that a proportion of useful information is lost when facets are aggregated to the broad trait level. Contrary to the first approach, whereby broad personality measures best predict broad and narrow performance criteria, this evidence illustrates that narrow personality traits should not be discarded in favour of broad factors. It can therefore be concluded that future research should consider assessing current personality inventories to reflect narrow constructs and therefore aim to improve predictive validity.

Implications

The bandwidth-fidelity dilemma has key implications for the conceptualisation and measurement of the Big Five Factor model (Soto & John, 2017). For example, one possible solution to this trade-off is hierarchical assessment, as facet level traits may indicate, and individual facets may be linked to, trait-life outcome associations as well as specific patterns of behaviour. However, when constructing personality assessments, the nuances should represent the facets as broadly as possible, to avoid biases.

Most of the studies discussing the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma are in the context of job performance or related to

organisational psychology (Salgado et al., 2015). In the following example, Rodrigues and Rebelo (2020) compared the contribution of trait emotional intelligence (EI) with its specific facets for predicting overall job satisfaction. The results showed that corresponding facets of self-emotions appraisal, other-emotions appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion, when residualised, do not outperform the contribution of the higher-order traitEI factor and the Big Five Factor in the prediction of overall job satisfaction. The study supports criterion-related validity, thereby corroborating with the first key approach to the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma, as suggested by Salgado (2017). Furthermore, research on the dilemma in areas such as emotional intelligence is lacking, thus warranting further studies to understand the differences between broad and narrow personality measures may link to mental health, education, and cognitive psychology.

Conclusion

The bandwidth-fidelity dilemma has proven to be an important aspect in understanding how personality science is measured. There are arguments favouring broader measures as well as a minority of researchers advocating narrowness, with evidence highlighting that striking a balance between better criterion-related validity vs predictive validity continues to be a challenge in the literature (Salgado, 2017). Finally, the dilemma may have a place within mental health research which would broaden the application of the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma to areas beyond organisational psychology. Whilst the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma continues to be a topic of discussion in personality science, future research can contribute to refining measurement tools and aim to establish a common framework to balance simplicity and accuracy.

Reference List

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2005). HonestyHumility, the Big Five, and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality 73(5), 1321–1354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00351.x

Ashton, M. C., Paunonen, S. V., & Lee, K. (2014). On The Validity of Narrow and Broad Personality Traits: A response to Salgado, Moscoso, and Berges (2013). Personality and Individual Differences 56, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. paid.2013.08.019

Cronbach, L. J., & Gleser, C. G. (1957). Psychological Tests and Personnel Decisions. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Hengartner, M.P., van der Linden, D., Bohleber, L. and von Wyl, A. (2016). Big Five Personality Traits and the General Factor of Personality as Moderators of Stress and Coping Reactions following an Emergency Alarm on a Swiss University Campus. Stress and Health 33(1), pp.35–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2671.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric Properties of the HEXACO Personality Inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39(2), 329-358. https://doi-org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1207/ s15327906mbr3902_8

Rodrigues, N. M., & Rebelo, T. (2020). The Bandwidth Dilemma Applied to Trait Emotional Intelligence: Comparing the Contribution of Emotional Intelligence Factor With Its Facets For Predicting Global Job satisfaction. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12144-020-00740-1

Salgado, J. F. (2017). Bandwidth-Fidelity Dilemma. Encyclopaedia of Personality and Individual Differences, eds Zeigler-Hill V., Shackelford TK, editors.(Berlin: Springer International Publishing, 1-4. https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1280-1

Salgado, J. F., Moscoso, S., & Berges, A. (2013). Conscientiousness, Its Facets, and The Prediction of Job Performance Ratings: Evidence Against the Narrow Measures. International Journal of Selection and Assessment 21(1), 74-84. https:// doi-org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1111/ijsa.12018

Salgado, J. F., Moscoso, S., Sanchez, J. I., Alonso, P., Choragwicka, B., & Berges, A. (2015). Validity of the five-factor model and their facets: The impact of performance measure and facet residualization on the bandwidthfidelity dilemma. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(3), 325–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2014.903241

Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 117–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000096

Psychology

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

page 16 The Pantomath page 17

The findings from this approach highlight key implications for personnel selection, in which potential candidates for jobs are screened and may be asked to answer questions related to their work ethic, efficiency, and productivity.

Aliens Built the Pyramids: Ethics of Educating on TikTok

Stephanie S Black

Stephanie S Black

On the 12 May 2023, I participated in a roundtable discussion entitled “TikTok and Public Medievalism II: Sensationalism and Ethical Engagement” presented at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo Michigan. The discussion brought together archaeologists and historians who create content on TikTok to discuss their use of the platform as an educational tool.

TikTok, owned by ByteDance, only expanded beyond its stereotype as a dance app for teenagers during the Covid -19 pandemic (Khan 2022, 452). My journey on TikTok started in October 2019, right before the start of the pandemic, allowing me to experience how content has changed, such as being a part of the growth of “Archaeology TikTok.” I did not intend for my account to focus on archaeology; it organically developed as I created short-form videos on topics that interested me, which primarily included archaeology and history-related information.

What are the ethical responsibilities of archaeologists and historians on TikTok to combat this misinformation? Is there a moral obligation to engage or is it preferable to ignore it? These are questions which anyone creating content will find themselves having to confront.

Even before the closure of face-to-face learning (due to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020) research was being undertaken on the use of educational videos to engage students in learning (Brame 2016). Since the start of the pandemic, TikTok has been studied for its usefulness in learning for students (Kahil and Alobidyeen 2021; Saidi, Radzi and Ibrahim 2021). This leads us to question what is the ethical responsibility of those who create educational content on TikTok?

Though there are many positives to TikTok as an educational platform due to its focus on short-form videos, (identified by Brame (2016) as being more effective for education than long-form content) the amount of pseudoarchaeology misinformation being spread on TikTok is of concern. This problem, however, is not limited to TikTok. It is also a concern on YouTube (Emmitt 2022). Focusing just on TikTok, in just one study of thirty TikTok videos found after typing “archaeology” into the TikTok search bar, a third were flagged as being questionable due to ethics violations and the spread of misinformation (Khan 2022, 454).

videos. Yet I am aware of the balance. I question whether I should be including a detailed reference list in all my videos. But I started my account for fun. I share history content because I want to share what I am passionate about. To reiterate a point made previously, my aim is for people to see my videos and be inspired to do their own research and to not use me - or TikTok - as a primary source. There is no rule book and so each of us at the roundtable and on TikTok must decide for ourselves what are the ethics of TikTok.

Bibliography

Stephanie S Black (@archthot), “Red Flags:Selling Indigenous (Sami) Remains – Osteologist only has a BA – Claims ethical but remains from 19th Century which is not known for sourcing medical cadavers ethically” TikTok, 8 August, 2021, https://www.tiktok.com/@ archthot/video/6995142736076737797?_r=1&_ t=8auigPCwmrV.

Brame, Cynthia J. 2016. “Effective Education Videos: Principles and Guidelines for Maximizing Student Learning from Video Content.” CBE Life Sciences Education 15 (4).

“We were struck by how TikTok, as a platform, seems to facilitate pushback in a way that other platforms do not; in our research on Instagram for instance, we have very rarely come across posts that call out another user or engage with the ethical and moral issues presented by bone trading, to the extent that can be regularly seen on TikTok…”

(Graham, Huffer and Simons 2022, 215-216).

My perception of TikTok shifted after I posted a video in August 2021 (Black 2021, @archthot) criticising the ethics of the TikToker @jonsbones, who was selling human remains, including a Sami skull. The discussion around the human bones trade went viral. This was seen in both digital spaces and in academia, with articles discussing the ethical and social development of this topic, such as “When TikTok Discovered the Human Remains Trade: A Case Study” (Graham, Huffer and Simons 2022). In this article, the researchers studied the pushback on TikTok (which evolved from my involvement) against the human remains trade.

This article fundamentally shifted my perception of TikTok as a platform, as it opened my eyes to engagement with Public Archaeology and the role of content creators. Until that moment I only saw my TikTok as a fun hobby when I was bored. It was confronting and intimidating to realise a video I filmed in my PJ’s last thing at night would be dissected by academics.

The roundtable forced me to reflect on the way in which I create content. Are my actions ethical? While some people believed it was ethical to include sources in all their videos, I don’t (unless it is a direct quote). I made this decision as I do not want my account to become a primary source for my viewers. My aim is for people to see my videos and be inspired to do their own research.

I believe TikTok can be a powerful tool to combat harmful misinformation. Accounts, however, will use sensationalism to push harmful theories such as about Ancient Aliens. It is also important to remember that the TikTok algorithm is remarkable at pushing similar content once you have shown interest in a video. Therefore, I believe that if you want people who are consuming misinformation to see your videos, you need to be creating similar sounding and looking content. Of course, my content is sensationalised. My primary videos which have gone viral are of me crying and looking miserable. I do not walk around museums and churches crying, but the over dramatics are what capture people and have them engage with my

Emmitt, Joshua. 2022. “YouTube as a Historical Process: The Transfiguration of the Cerro Gordo Mines through Ghost Town Living.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 10: 237-243.

Graham, S, D Huffer, and J Simons. 2022. “When Tiktok Discovered the Humans Remains Trade: A Case Study.” Open Archaeology 8 (1): 196-219.

Kahil, Bachar, and Buthina Alobidyeen. 2021. “Social Media Apps as a Tool For Procedural Learning During COVID-19: Analysis of Tiktok Users.” Journal of Digitovation and Information System 81-95.

Khan, Y. 2022. “Tiktok as a Learning Tool for Archaeology.” Advances in Archaeological Practice 10 (4): 452-457.

Saidi, Normaizatul A, Naziatul Aziah Mohd Radzi, and Mazne Ibrahim. 2021. “Creating Excitement in Learning through TikTok Applications.” Edited by Nur H Hussein. E-Proceeding of Carnival of Research and Innovation (CRI2021). Kelantan: Universiti Malaysia Kelantan. 322-323.

The Internet and Social Sphere

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

page 18 The Pantomath page 19

Climate FRESK Workshop

Scarlett Whitford-Webb

During Michaelmas Term, the Global Citizenship Programme’s (GCP) Café Scientifique partnered with Café Politique to deliver Durham University’s first ‘Climate FRESK’ session.

‘Climate FRESK’ was developed by the French engineer Cédric Ringenbach in 2018. ‘Climate FRESK’ breaks down the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports into bite-sized chunks (Climate FRESK, 2022) with the goal to make climate change education accessible for anyone. Unlike other climate change events such as seminars and lectures, ‘Climate FRESK’ sessions are interactive games in which participants match up IPCC statistics with probable human causes and potential solutions. In this way, ‘Climate FRESK’ sessions break down dense scientific reports into accessible portions of information that can be absorbed by individuals from all educational backgrounds.

The ‘Climate FRESK’ workshop took place at Ustinov College during mid-November. Hosting this event was suggested by Glenn McGregor, the principal of Ustinov College, whose own work has focused on the impact of climate change. In this session, approximately 15 attendees worked together in two teams to arrange statements from IPCC reports in order of: probable human cause, the resulting problem, and future solutions. The event attracted attendees studying in multiple different fields represented in college from marketing to astrophysics. To understand how the session would run, a representative from Cafe Scientifique (myself) and Café Politique (Janelle Anne Rabe) met with two ‘Climate FRESK’ facilitators. These facilitators showed me and Janelle how the game is played, as well as what a completed ‘Climate FRESK’ may look like.

On the day of the event, the ‘Climate FRESK’ game took approximately three hours. This is because both teams had to arrange cards, discuss potential solutions, and take a break for some pizza. At the end of the session, participants mentioned that they found seeing the relationships between human behaviours and environmental degradation helpful, whereby they realised how complex and intertwined they are. The majority left with a clearer understanding of the current state of climate change, but in a more hopeful sense than is portrayed by the news. This result was encouraging

to the facilitators too, who aim to start conducting more sessions across the Durham Collegiate system. Additionally, hosting ‘Climate FRESK’ at Durham University offers an opportunity for students too. This is because students are encouraged to train to become facilitators themselves, which they can do for a small fee. Not only does becoming a facilitator help students learn more about the pressing issue of climate change, but it can supplement your CV.

A link can be found in ‘references’ if you are interested in becoming a facilitator.

Bibliography

Climate FRESK, 2022. Become a Facilitator [online] Available at: <https://climatefresk.org/ world/become-facilitator/general-public/>

[Accessed 15 December 2022].

Climate FRESK, 2022. Our Purpose [online] Available at: <https://climatefresk.org/world/ purpose/> [Accessed 15 December 2022].

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

page 20 The Pantomath Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme Events page 21

For this reason, hosting a session of ‘Climate FRESK’ at Durham University fitted perfectly with one of the primary aims of the GCP which is to foster ‘understanding’ within Ustinov College.

Digging Deep: Coal Miners of African Caribbean Heritage at Ustinov College, A Perspective On Research Activities To Improve Cultural Heritage and Diversity Awareness

Norma Gregory

Diverse Heritage in Practice

As an active and passionate practitioner of interpreting Black British history since 1994, my work has involved pushing boundaries and barriers, with my goal to inspire others to take active and wider steps in their own learning journey. Ultimately improving a better understanding and acceptance of African diasporic contributions within mining, UK industrial workforce, and global industrial heritage.

As an independent-freelance-educator and enterprise leader (as director of Nottingham News Centre CIC since 2013, former schoolteacher, and educational mentor) my current self-directed vocation includes activities such as:

As a curator and researcher of diverse, cultural and industrial history, it is my pleasure to share my experiences tackling the challenges and successes of locating, collating, interpreting and sharing the memories and narratives from Coal Miners of African Caribbean Heritage. I have researched Black British miners who worked in the North-East coalfields, Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, Wales, and other coal regions across the UK during the twentieth century and before the closure of UK deep coal mining in December 2015.

My guest presentation, organised and hosted by Dr Sarah Rosen and the GCP, aimed to inspire diversity of thought in promoting new thinking, to encourage voices to participate and to help lead new ways of understanding and experiencing social, industrial, and cultural history.

Through interpretations of a variety of research data, the Digging Deep Black Miners Heritage touring exhibition was curated and exhibited across the UK and at various sites at Durham University, including Ustinov College, the department of Anthropology, and Durham Castle between October 2022- January 2023.

Examples of community derived research questions, which initiated my learning journey were:

• Who are the Miners of African Caribbean heritage (i.e., Black miners)?

• Where are they located in the UK and the north-east?

• Which coal mines provided employment for the Black miners?

• Where is their place in history?

• What is their contribution to history?

• How might they describe their experience?

• What can I do/we do to support their legacy today?

Over the years, I tackled my research questions through various methodologies, allowing me to collect data by:

• Using oral histories interview methodologies to collate primary source data.

• Collecting and creating original photographic images.

• Conducting literature reviews to review secondary source data.

• Visits to working mining and closed mines, visits to mining related museums and art galleries.

• Participatory research by taking part in the Durham Miners Gala, July (2018, 2019, 2022) and other community events.

• Analysing and assessing existing mining related media content.

• Purchasing and collating rare (and often discarded) mining artefacts and memorabilia from online auctions, car boot sales, antique shops.

• Analysing original diaries, posters, flyers, flags, and colliery banners.

• Co-creating with artists and creative practitioners to develop new art works and installations, podcasts, documentary film and publications.

• Hosting community events such as miners’ reunions, learning workshops, craft and art sessions plus online conversations and learning activities.

• Exploring and utilising artistic, creative, and innovative ways to accommodate under-represented heritage.

• Writing publications, articles, and online content to share learning.

• Working collaboratively with museums, academic institutions, and diverse communities in ways that benefit all collaborators towards fully inclusive practice.

• Providing consultancy services to review and/or improve archive collections and cultural education content.

By working in a non-conventional, driven, and exploratory way, it has improved my cultural industrial heritage education. This was achieved by creating a ‘case study’ of decolonisation ‘real practice,’ particularly for heritage and cultural sector professional development, whilst adhering to the Equality Act 2010 and the global equality, diversity, and inclusion agenda.

In conclusion, my work has benefited the research community and heritage sector by recognising and promoting the value of diversity and the new dimensions it brings, in terms of new knowledge, new partnerships, new audiences, new funding support, new narratives, and education for all. Through innovative and various uses of new data, it has helped to create new ways to understand and raise awareness of the importance and relevance of globally connected cultures of the past, present, and future.

View more at www.blackcoalminers.com and www.nottinghamnewscentre.com

Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme Events

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal

page 22 The Pantomath page 23

SUCCESS Seminar: Personal Branding and Identity Development Carolina Bysh

In today’s job market our efforts, education, or performance are, unfortunately, not enough to stand out (Monarth, 2022). By creating a personal brand, it is possible to increase your visibility, credibility, and access valuable opportunities to start and/or advance your career

The process of building your personal brand is of circular nature and is constantly evolving. There are five key stages which facilitate the development of your personal brand.

Self-Awareness

Before you start to intentionally communicate who you are and how you want to be perceived, it is important to know yourself better and understand what your core values are. Authenticity should be the foundation of your personal brand, otherwise, it will be impossible to maintain this impression over a long period of time. A useful starting exercise is to ask yourself: “How do I envision my professional identity?” A professional identity refers to the meanings that you, as the individual, attach to yourself in the context of work (Dutton et al., 2010). By taking your current but also aspiring skills, character traits, habits, tasks, and roles in relation to work into consideration, you can start envisioning your professional identity.

Research

When envisioning your professional identity, investing time to research the nature of other individuals and organisations related to your career aspirations, as well as understanding trends relevant to your profession, are important steps to shape your own personal brand. Identifying role models within and outside your industry, allows you to draw inspiration from others to shape your own professional identity and more specifically, how you want to represent this professional identity. In addition to identifying individuals, it is also important to look at the company culture and values of different organisations you

Experiment

Coming up with these three attributes to describe your personal brand is extremely difficult, therefore, it is important to create a space for exploration and experimentation to help you refine your personal brand. In addition, as the definition suggests, a personal brand relies on creating, positioning, and maintaining a positive impression of oneself. Therefore, external feedback on how others would describe your personal brand is invaluable.

Act

are interested in working for. Consider how the professional identity you are mentally constructing relates to an organisation’s culture and values. Finally, it is helpful to be aware of general trends within your industry related to your career development. Though the content of one’s personal brand is important, it is also essential to consider how this content is represented. By taking the time to understand your outside environment, you can identify key priorities, for example the importance of a social media presence for promotion or the need to attend in-person networking events to establish your personal brand.

Define

Once you have spent time better understanding how you envision your professional identity through selfawareness and research, the next step would be to create a label for your personal brand. This does not need to be communicated outwards. However, by having a clear idea of your personal brand it will allow you to present yourself and act with more confidence.

One useful exercise for defining your personal brand is the 3-word/phrasemethod. Coming up with the three most important attributes of your personal brand can be incredibly difficult, however, once successful, it is a very helpful task. Example words/phrases to use include trustworthy, research-based, passionate, empathic, analytical and visionary.

Once you are comfortable about your newly developed or refined personal brand, demonstrating these attributes through your behaviour is especially important for maintaining your personal brand. Personal branding takes place at the intersection between perception and reality. Therefore, it is not enough to only communicate what your personal brand is, but also demonstrate your personal brand through actions.

Overall, personal branding is a relational process. Although understanding how you want your personal brand to look is critical in the overall process, a personal brand will only be sustainable, if it is accepted and valued by your external environment. The five steps elaborated in this article, intend to provide a useful guideline on how to develop a personal brand on your own terms without neglecting the professional environment you are exposed to.

Reference List

Dutton, J.E., Roberts, L.M. and Bednar, J. (2010) “Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of Social Resources,” Academy of Management Review, 35(2), pp. 265–293. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5465/ amr.35.2.zok265.

Gorbatov, S., Khapova, S.N. and Lysova, E.I. (2018) “Personal branding: Interdisciplinary Systematic Review and research agenda,” Frontiers in Psychology, 9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02238.

Monarth, H. (2022) “What’s the Point of a Personal Brand?,” Harvard Business Review 17 February. Available at: https://hbr. org/2022/02/whats-the-point-of-a-personalbrand (Accessed: December 9, 2022).

The Ustinov Scholarly Journal Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme Events

“Personal branding is a strategic process of creating, positioning, and maintaining a positive impression of oneself, based on a unique combination of individual characteristics, which signal a certain promise to the target audience through a differentiated narrative and imagery”

page 24 The Pantomath page 25

(Gorbatov et al., 2018:6).

Powering the Future We Want: Global Innovative Approach in Sustainable Energy & Environment Introduction

Kate Paterson and Akmaral Karamergenova

The Ustinov Annual Conference is a platform for Postgraduate students, early-stage researchers, academics, and industrial people to interchange, enrich themselves in an academic and professional capacity, network, and make friendships.

This is Ustinov College’s seventh year running the conference and is held annually within the framework of the Ustinov Global Citizenship Programme, which is now in its thirteenth year. In addition to the theme of the conference, this year’s Ustinov Annual Conference provides an opportunity for every person to feel as if they are ‘a global citizen’ - a key component of the Global Citizenship Programme - who takes an active role in the community and works with others to make the planet more peaceful, sustainable, and fairer. The Global Citizenship Programme fosters an environment which allows the members of Ustinov College to reflect critically on themselves, exploring the world around them regarding the presentation of the past and how we can impact the future.

To do so, the programme encourages participants to think about the ethical components of our actions, which prompt the ability to expand worldview and collaboration.

The theme of the conference, Powering the Future We Want: Global Innovative Approach in Sustainable Energy & Environment, was not a spontaneous decision. Both Akmaral and Arjmand (the organisers of the 2023 Ustinov Annual Conference) are Engineering students, which led their theme choice to engage with discussions on energy and environmental sustainability. The sustainable development goals provide worldwide guidance for addressing the global challenges facing the international community. It is about better protecting the natural foundations of life and our planet everywhere and for everyone,

by preserving people’s opportunities to live in dignity and prosperity across generations. These discussions were led by the three keynote speaker lectures: ‘Culture and Sustainability Transition’ with Professor Janet Stephenson, ‘What is a Just Transition and Why Should We Want

One’ with Professor Simone Abram, and ‘The Renewable Energy Transition: Making It Work in Practice’ with Professor Douglas Halliday. These lectures covered Ustinov Annual Conference’s three main research areas:

Renewable Energy and Advancement in Energy Conservation

The conference gave the opportunity to share various ideas for the responsible utilisation of natural resources, explore the solutions for a sustainable environment, bring social awareness, and encourage the active participation of people for global sustainability. The Ustinov Annual Conference builds a strong network by allowing visitors and participants to engage with the important and factual data and information given, which, in turn, enhances our message of the importance of sustainability.

Sustaining Clean Water for the Future Carbon Capture Technologies

Solar Water Treatment Techniques Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage

Wind Water Conservation Low-Carbon Hydrogen Production

Geothermal Access to Healthcare, Support Services, Education and Employment

Systems Integration and Infrastructure

Wave Energy E-Fuels and Hydrogen Propulsion

Energy - Efficient Machines

Energy Conservation Techniques in Buildings

Energy Storage Techniques

The Ustinov

Journal

Scholarly

page 26 The Pantomath page 27 Ustinov Annual Conference 2023

The Ustinov Annual Conference organisers from left to right: Arjmand Khaliq, Paula Furness, and Akmaral Karamergenova

Ustinov Meets: Professor Janet Stephenson

Professor Stephenson Stephenson is a research professor at the Centre for Sustainability, a research centre at the University of Otago. As a social scientist, she is interested in how society can transition to a sustainable future and the role of culture in preventing (or driving) that change. A lot of her research has focused on cultural change amongst both producers and consumers in the energy sector. She engages extensively with councils, communities, and Māori groups on researching the challenges of climate change adaptations. As Director of the Centre for Sustainability 2011-2022 she led the development of a strong research culture with a focus on interdisciplinary and collaborative research.

On 15th June 2023, Ustinov College’s Global Citizenship Programme (GCP) held their Ustinov Annual Conference (UAC) which focused on approaches to sustainability. I had the pleasure to interview one of the keynote speakers, Professor Janet Stephenson, about her involvement within the push for sustainability, her involvement with the UAC, and her recently published book Culture and Sustainability: Exploring Stability and Transformation with the Cultures Framework

Professor Stephenson’s presentation explores how cultural framing can expose the causes of the sustainability crisis and why as a culture we are resisting change. She details how culture operates structurally to replicate the status quo and constrain change amongst those who are less powerful. At the same time, cultures offer a deep reservoir of possibilities for different ways of living in the world. Seeing the world culturally brings new insights into the potential for transformational change. This is important as researchers tend to see the sustainability crisis reductively.

Professor Stephenson explains one of the reasons for this can be seen when reflecting academic training – seeing the sustainability crisis, for example, as an emissions reduction issue, or a

water shortage issue, or a health issue, even though they all have the same cause. This focus came about through Professor Stephenson co-leading a big interdisciplinary research programme called Energy Cultures from 2009-2016, where the group developed an approach called ‘energy cultures framework’ where they analysed the relationship between culture and energy. The energy cultures research programme was highly interdisciplinary – research team members included people from the disciplines of sociology, economics, physics, consumer psychology, marketing, system dynamics, law, and engineering. The framework has been used in other interdisciplinary research programmes around the world and by lead researchers from many different disciplines. It is open to use with both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

The product of this research can be seen where other researchers around the world have started applying the framework to different research topics outside of energy. By 2021 it had been applied to around 100 different research projects in at least 20 different countries and used by postgraduate students as well as big research teams. Professor Stephenson reviewed how it had been used and to

draw together what could be learned from its many applications which turned into her book ‘Culture and Sustainability’. The book strengthens the framework theoretically, draws conclusions about the relationships between culture and sustainability outcomes, reveals (with many examples) the processes of cultural stability and cultural change, and shows how the framework can be used to support research endeavours and the development of policy.

The many applications of the cultures framework, both by Professor Stephenson and other researchers reveal how cultural processes can operate (often invisibly to cultural actors) to prevent change or result in unintended consequences from policy interventions by showing why financial incentives don’t necessarily work as intended. The research identifies how cultural change can be initiated and how a change to one aspect of culture can often lead to consequential change to other aspects. It details how culture operates at many levels in ways that often slow down or prevent sustainability transitions, and how cultural diversity is a critical foundation for a sustainable future.

“We should be doing more than ‘having discussions’ about energy and environmental sustainability. We all need to be acting in our professional and private (and student) lives to support a transition to a sustainable future, and this is getting more urgent by the day. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the United Nations (UN) make it clear that humanity is on the brink of causing extreme destabilisation of the natural systems we depend on. We are ‘at war with nature’ as the UN Secretary General states.”

Ustinov Annual Conference

This is Professor Stephenson’s first year where she is involved in the UAC, for which the organisers of the event requested her attendance specifically. Professor Stephenson was already planning to visit Simone Abram, another keynote speaker for the UAC, to give a seminar to the Durham Energy Institute (DEI). Her work engages with the two main aims of the UAC:

1. Engaging with discussions on energy and environmental sustainability.

2. Addressing the global challenges facing the international community.

Though she is based in New Zealand, her work is internationally influential as she works with researchers all over the world. She is very active in wanting us to change our behaviours in order to have a sustainable future.

Professor Stephenson’s lecture ‘Culture and the Sustainability Transition’ was incredibly informative, detailing the way cultural features impact and affect sustainability. Culture is about how materiality, motivators, and activities interlink and work with each other, creating a cultural ensemble. Different cultural variants can be found across generations, genders, and nations thus allowing researchers to examine sustainability culture on multiple levels and provide a framework for as to why we have a crisis today. These cultural features can be changed as long as we harness our agency, different factors affect our agency

The most powerful change is in how we think, and there the most powerful change to make is one of humility, recognising that humans rely on the magnificent natural world to exist and that by destroying it we are destroying ourselves.

which can be our control such as money, education, and living situation.

How Cultures Resist Change:

1. Strong alignment with historical and traditional contexts, also known as a cultural ensemble

2. Lack of agency

3. External stabilising influences

4. Cultural vectors

5. What We Can Do to Change Our Culture:

6. One cultural change can have a domino effect elsewhere

7. Changes in agency

8. Changes in the cultural ensemble (e.g.: Covid-19 and the development of working from home and an increased use of video calling)