Fire Insurance Should Be Bought

FROM EXPERIENCED AGENTS

We have renresented the Liveroool & London & C!obe Ins. Co., Ltd., for more than fifty years. -Consult us.

DAVENPORT & CO~

1113 E. Main Street ....

Richmond, Virginia.

Business Phone, Rand. 182. Residence Phone, Boul. 4915-J.

ROYALSHOEREPAIRINGCO.

306 NORTH SIXTH STREET

WORK CALLED FOR AND DELIVERED

WORK GUARANTEED

J. MEYERS, Prop.

FLOUR WITH A PEDIGREE

There isn't an old lady in Richmond who can't tell you all about DUNLOP FLOUR and its goo<lness. It has been sold in Richmond for so many generations that it is known as "the flour with a pedigree." As a proof that Richmond's hcusekeepers have excellent judgement. other rousekeepers in foreign l;rn<ls prefer it, and so great is the dcm;ind that the mi11s f.1d '1ificu1ty in supplying it. Our excellent feature aho:i.t '.)l,'1\! J)? FI Ol, R is it, cleanliness-the human 1-ianJ do-~-; not touch it unti! it reaches your kitchen.

DUNLOP MILLS

Richmond, Va.

IN ANSWERING ADVERTISEMENTS MENTION THE MESSENGER

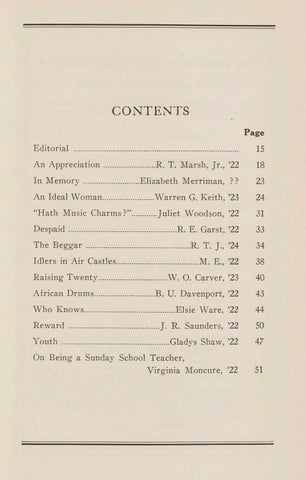

THE l\1ESSENGER

Subscription Price $1.50 Per Annum

Entered at the Post Office at University of Richmond, Va., as second-class matter.

VOL. XL VIII. APRIL, 1922 No. 7.

Richmond Col1ege Department

A_ B. CLARKE, '23 _____________________________________

Editor-in-Chief

W. G. KEITH, '23 ____________________________________ Assistant Editor

0. L. HITE, '22 _____________________________________Business Manager

G. S. MITCHELL, '23 _____________________Assistant Business Manager

M. W. McCALL, '24 __________________________________Exchange Editor

Mu Sigma Rho

R. E. GARST '

B. U. DAVENPORT

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Philolo~ian

W. G. KEITH

C. W. NEWTON

C. G. CARTER

Westhampton College

THELMA HILL ______________________________________

Editor-in-Chief

PEGGY BUTERFIELD _______________________________ Assistant Editor

PEGGY BUTERFIELD _____________________________Exchange Editor

ELMIRA RUFFIN __________________________________Business Manager

MARY PEPLE ___________________________Assistant Business Manager

THE MESSENGER (founded 1878; named for the Southern Literary Messenger) is published on the 15th of each month from October to May, inclusive, by the PHILOLOGIAN and MU SIGMA RHO Literary Societies. in conjuntion with the students of Westhampton College. Its aim is to foster literary composition in the college, and contributions are solicited from all students, whether society members or not. A JOINT WRITER'S MEDAL, valued at twenty-five dollars, will be given by the two societies to the writer of the best article appearing in THE MESSENGER during the year. All contributions should be handed to the department editors or the Editor-in-Chief by the 1st of the month preceding. Business communications and subscriptions should be directed to the Business Manager and Assistant Business Manager, respectively.

Address-

THE MESSENGER, University of Richmond, Va.

SOUTHWESTERNBAPTISTTHEOLOGICALSEMINARY

SEMINARY HILL, TEXAS

A theological seminary with all theological studies and a large range of practical studies in Missions, Religious Education, Evangelism, Gospel Music; for both men and women; taught by a group of more than 30 competent, scholarly, spiritual teachers: a noble equipment; a beautiful location; a student body of more than 700; a great spiritual atmosphere; large opportunity for student-pastorates; a summer session, May 31 to July 6, 1922; correspondence courses offered frei;.

FQr further information write:

L. R. SCARBOROUGH, D. D., President

Seminary Hill, Tex,as

WATCHMAKERS JEWELERS

Ostergren & Dobb

<fbitorial

Good-byes are difficult things to say. It is always a temptation to slip away and not say good-bye. But we feel that the flight might appear ignominious, so for the last time, we take our editor's pen in Au Revoir hand and write just a few words. We want to thank those who have helped us, and we are grateful to you. And we want you to help our successors. To those of you who have proven indifferent to the efforts of this staff, we ask your co-operation with the incoming staff.

We tell you good-bye; also we bid adieu to THE MESSENGER( and it is not so easy as one may think). THE MESSENGERis ours-not the staff's-and you gave it to us in trust for 1921-22. We give it back to youwith a high-and thank you for the trust. Our act has drawn to a close; the orchestra strikes up the finale, and as the curtain slowly lowers, we smile a bit wistfully at you, University of Richmond, and beg to make it au revoir but not good-bye.

T. H.

The question of ultra-modern writing always confronts a magazine which tries to maintain comparatively high literary standards. THE MESSENGER,while limited in its choice of material, being entirely dependent on work done by college students, has at least some policy which it endeavors to follow. The usual types of writing consisting of short stories, essays, sketches, and verses are those which THE MESSENGERis trying to develop. This

THE MESSENGER

attitude is taken for several reasons. First, because there are courses in these forms of composition given in the University, and second, because, with the possible exception of verse, these forms are the most popular, the most representative of college students' ability and require the greatest care in preparation because of the general and intelligent criticism which usually considers them.

Dramatic composition is not excluded from the pages of THE MESSENGER,but it is not encouraged. There is no instruction in our curriculum for the technique of such work and with possible exceptions, there are few college students who undertake to write drama suitable for publication.

As to the publication of free verse, THE MESSEGER wishes to take a definite and unequivocal posiition. Realizing the possibilities in free verse and admitting its worth and influence, we contend that the average college student's attempts in this respect are most assuredly not incited by the desire for freedom of thought; for expression unhampered by form and classic rules, but provoked by the desire to escape the drudgery and intense mental exercise which should accompany the production of any piece of successful literary work. Knowing this, THE MESSENGERis wary about its acceptance of V ers Libre; and yet, wishing to be fair to those who have striven and to be representative of the work done by the students of the University of Richmond, we wish it known that Free Verse will have a place whenever it reaches the same standard which the other types of work reqmre.

Furthermore, THE MESSENGERwill try to direct the energy of those interested in writing to serious, more mature subjects. This does not necessarily mean that a

THE MESSENGER 17

college student should attempt to compete with the products of age and experience but that he should aim at higher subjects in his work and relinquish the ephemereal, childish conceptions, which so of ten find expression in college publications. The deeply personal article is there£ore discouraged because it seldom reaches the reader with the force which may characterize the writer's experience. It is not so much individuality of materidl as of expression and treatment which THE MESSENGERhas in mind. The college student must always bear in mind that style is ( or should be) the aim of his literary attempts, and not a finished piece of work. With these points in mind, THE MESSENGERwill striYe to maintain as high standards as the contributors. assisting in every detail, are willing to consistently exemplify

~n

~predation

ROBERT T. MARSH, JR., '22.

"A thankful heart is not only the greatest virtue, but the parent of all the other virtues," says Cicero. Not claiming virtue, but with a thankful heart, I approach the end of my senior year at college. Four years have I spent within its walls. How they have flown! And now the time to leave draws near. When one bids farewell to a dear friend, after enjoying his hospitality, it is meet that he make some expression of thanks for kindnesses shown and favors received, so, as my undergraduate life comes to a close, I would be most thoughtless and ungrateful were I not to attempt some expression of appreciation for the benefits which have been bestowed upon me by my Alma Mater . So numerous and immeasureable have they been, however, that I am not capable to tell fully my gratitude. As some preambulating, would-be encyclopaedia has said, "The paucity of the English language is hereby very evident in my inability to express my extreme gratification"-and so with me.

We come to college to learn. Many go away feeling that they know no more than when they entered. Then they either have not used their time well, keeping their doors shut to the greatest opportunity which may ever knock, or they do not realize the extent of their knowledge. Usually when one begins to discover how much there is to know and how little he has acquired, he is truly beginning to learn. Very of ten at the end of our college course we are more educated than we think. We may have forgotten how to differentiate u with respect to .i- a month after the term closed, or the formula

for sodium hydroxide may have vanished from our minds as the dew before the morning sun, but general knowledge and a great deal of specific knowledge has been retained. Probably it was relegated to the subconscious mind, where it will stay, apparently forgotten , until the need for it arises; then it will come forth and "save the day like a conquering hero."

I feel that a most important part of my college training has been "learning how to learn." It is practically impossible to carry around in one's head vast amounts of data, and endless dates and statistics, and have them always on the tip of the tongue ( unless we take a course in some correspondence ·school of memory) . Furthermore, it is not necessary to have these countless facts at the tongue's end if we know how and where quickly to secure them when occasion demands. Our research work for various departments, our minute study of suggested and original topics, has taught us how to use the hidden wealth of our libraries. I think of knowledge as a large crystal spring of sparkling water, hidden within a jungle. One cannot expect to carry away all the water from this spring, but must drink from it time and time again. Not everyone can satisfy his thirst, for the fount is hidden. There is a road, however, which leads to the much-sought-after liquid, and college points out this way. It serves as a guide, a lamp unto our feet and a light unto our path. I thank my Alma Mater for teaching me to tread this path.

College life is a world in itself. It is a connecting link and a stepping stone from our childhood, or dependent period, to maturity and independence. Its atmosphere is almost wholly idealistic and I look upon it as a Utopia. The inhabitants of this Land of Bliss are very active, working, playing, struggling, and triumphing.

Problems confront them, requiring clear and quick judgment. Misunderstandings occur, and rivalries and enmities. Joy, pleasure and success reward their endeavors. They are taught to bear disappointment manfully, and to strive further with greater determination. Failure may come, only to be surplanted later by attainment. Why call such a land Utopia where problems and failure are continually found? Because the outcome of the various undertakings is not of too great significance. An endeavor resulting in failure is not irretrievable. One can profit by his mistakes at not too great a cost to himself and his associates. We live in miniature the life which will meet us outside of college, and we learn while we live. Our latest talents are awakened, our possibilities (probably previously unknown), are developed, and our limitations are discovered. Engagement in college activities makes the college man. He who sticks entirely to his books is doing himself an injustice, for he is not taking advantage of the chance to develop himself to the fullest extent, and he will live to regret it. My participation in clubs and organizations has meant everything to me. To feel that I was doing something useful and perhaps furnishing a tiny bit of motive power for the big college machine, has been my joy. In so doing ( and perhaps producing no noticeable benefit to the big- system), I have derived great good for myself. I have gained self-confidence, in which I was sadly lacking as a freshman, a desire and a feeling for leadership, and the will to carry out successfully any responsibility placed upon me. For these traits, whether they be permanent or not, I owe my sincerest gratitude to the institution which gave me the opportunity and helped me to bring- them out.

Emerson, in a letter to his daughter away at school, told her not to tell him so much about text-books, but to

write more concerning her professors. He realized that the thought and influence of the professors determine the policy of an institution and truly make the school. In the work of building character and shaping men's ideals they are the sculptors, and not the cold black words on the printed page. A professor with personality is worth a dozen without, even though they have many degrees after their names. I have been most fortunate in my association with my professors. They have been scholarly men, and at the same time sympathetic, broad-minded and with great understanding. They have been interested and concerned with the individual student's welfare. A bit of advice, a word of encouragement sincerely given means much to the recipient. My professors have all been worthy of respect-have inspired me with ambition, and it has been a privilege to know and become intimately acquainted with them.

A man's wealth may be reckoned according to the number of his true friends. Through them come his sweetest pleasures and deepest joy. Every one he has, then, may be counted as an asset, and such a thing- as having too many friends is hardly possible. "Go slow· in forming friendships," we have been advised. In college we have ample time to look about us, to examine men closely, to see how they react toward changing conditions, before we take them to our bosom and into our confidence. There are men available as friends and there is time to choose. During my stay here the student body has been of moderate size, where everybody has known nearly everybody else. Art atmosphere of comradeship and true fellowship has been always present and the students have had a spirit of helpfulness and friendly interest toward their fellows. Revering the same traditions, fighting the same battles, striving after the same

ideals, and loving the same institution has welded us together into an insoluable mass. I am sure that I have made ties which will continue to bind, not only during the first few years after graduation, but throughout life. "\Nherever I shall meet a loyal alumnus of the college, no matter whether he and I were there together, immediately a feeling of long acquaintance and intimacy will spring up. I am now a member of the large and everincreasing band of true sons, loving a common Mother and unceasingly trying to spread her fame and repay her for her kindnesses.

Only a few of a myriad of things have been mentioned. The more I write the greater a debtor I am shown to be. If I am to be successful in the future, the foundation of this success I owe to my college. When I shall turn in my leisure hands for enjoyment to art and literature, my ability to appreciate them, even slightly, will come from college instruction. Dear Alma Mater, for showing me the way to knowledge, for developing my talents and possibilities, for setting up ideals, for advising and encouraging, for providing me with freinds that will go wtih me unmoved through the shadows of life's closing day-for all these and more, I thank you. I will strive throughout my life to repay you by my loyalty and devotion to the teachings which you have instilled into me. May that day never dawn which shall find me without appreciation and gratitude for your gifts.

3Jn,ffltmorp

ELIZABETH S. MERRIMAN, '??

1\1y little kitten's name was Wraggles, She was a darling chocolate catSitting so sublimely on the tables, So inviting and so fat.

She was a pleasure-giving catEvery whisker placed with taste; So nice to give a kiss or patBut now she's in a better place.

This poem with its history shows that the art of poetry is cultivated by Westhampton at an early age. Betty Merriman, the eleven-year-old daughter of Mr. Merriman, of the Biology Department, was given a chocolate cat. When, shortly after becoming Betty's property, it begun to melt, and the owner was forced to consume it. Betty explains, therefore, that the last line refers not to the cat's chocolate body, but to "the nicer part of her." The word "sublimely" was acquired at "The Yell ow Jacket." Here is the memorial verse by Vvesthampton' s youngest poetess .

~n 3Jbtal'mltoman

WARREN G. KEITH, '23.

Experience was in conflict with youthful dreams and illusions. Young Lascel was distressed, moreover he was angry with his older friend, Munro, because of the latter's sneering remarks about a cherished ideal, which young romantist that he was, he held very near to his heart.

"So you believe in an ideal woman?" came Munro's enfilading fire. Then he laughted at the others' discomfiture. Lascel looked about him in bewilderment, as if he were waiting to beseech some one to assist him in his dilemma.

"Ha, Ha! my boy-one time in my life, my boy, I thought a rose the most beautiful flower in the garden; but then I learned that roses fade; the worms get into their hearts and eat their beauty away; some rose bushes never bloom; some bloom continually; they are varicolored, red, pink, white and gold-and yellow too-all of them have thorns. When I had learned this about my favorite flower, I found that all flowers are beautiful and possessed with great ch~rms. My boy, out of their environment, flowers lose their beauty; their sweet odors fade away and all of them droop and wilt. Now, as I look toward the flower garden, not one flower is prettier than another. A different posy for different occasions; violets for modesty, pansies for thoughts, red roses for trepidations of the heart, and yellow roses for the jealous mood-no one flower can suffice at all times."

Lascel did not like this arrangement of his posy kingdom. To him a woman was a celestial blossom condescending to bloom here on earth. "How can you speak

of flowers and your high regard for them, and yet for the sweetest you have no good word at all?"

"I said that they had thorns."

"And you spoke only of things we soon forget."

"All of them wilt-but sonny, do not think you soon forget the thorns. A sharp thistle stuck in the fleshy part of your palm will be remembered longer than the purple and gold blossom.

Munro was engaged in his greatest of sports-shattering idols.

"This old game of loving is just as natural as other forces on this world-sunshine, cold, electricity. There seems to be a compelling power that lures man 6n to finish his race. Woman is not that power, she is merely the agen .t of it. This power uses her charm to lure man on to fulfill his destiny. Passively he follows its lead, thinking all the while that it is a noble and fixed ideal beckoning him on. Another force quite analogous to this is socalled patriotism, which deludes man into believing that he is really going out to make war on some great dragon. Poor fool ! When woman is the agent the danger is great-the charm blinds him when sight returns to normal-it is too late. Man has accepted the stern rule of convention and custom. Nature laughs to think how easily she has fooled her wisest creation. What man thought to be the rose petals falling about him were in reality snow flakes falling in his pathway, obscuring the way of retreat."

"But I believe in a pure and sacred ideal of womaneach man should formulate for himself a code of principles to which his ideal woman must adhere-then strike out boldly and fearlessly and find her.

"Suppose she is on the other side of the world?"

"But my ideal is an American ideal."

"How many people do you know? From how many do you have a choice?"

"Well, let us get down from our pedestals and hear this bit of homespun philosophy. The ones you will want you cannot get; the ones you can get the devil himself would not have. Come on with one of your ideal women. Let me hear you describe her."

Lascel forgot the philosophy of Munro and started blithely along.

"I only ask that she be able to fulfill four requirements."

"Only four?"

"The first of these is this : She must be athletic, the American ideal; she must be intelligently patriotic; she must be religious, and she must be dainty. That is a woman. Possessing all those charms she will be the ideal of my dreams. And to tell you the truth-though you must not hint it to a soul-I believe that I have found her."

"Is that the first time?

"I admit I have been misled, but this time she is the genuine article-as soon as I try her out in some ways."

"This one has great physicals charms?"

"You have met her, Helen Weir-the new visitor at Will's. She has met one of my most rigid requirements. That is, I found her very dainty. Why yesterday she was so daintily costumed-pink organdie over Cinderella blue taffeta-with everything to harmonize."

"I see that you harmonized, too."

* * * * *

Lascel believed that Helen Weir was his ideal woman from the standpoint of daintiness. Strange to say, the remaining points were impressed upon him in a quick and decisive manner-all in the space of a few hours.

He studied the delightful blue of her eyes; he noted how the contrasting brown hair brought out the color of her cheeks; he elated in the graceful curve of her throat; he followed her every motion as she played on the tennis court opposite him.

"I am tired of tennis. I much pref er hiking. How far is it to the 'Peak?' "

Lascel saw the possibilities of a hike. If she is really athletic, I shall discover it now," he said aside. "Only nine miles-suppose we try a little stroll."

"Cut me a cane," she requested. "Let's put our feet into the road-and walk. Ah, it is real life on the g-reat broad road, where one feels that the road is ever before beckoning on."

They set out in a lively pace. Her stride on the turnpike was far different from the short steps taken under the shade of the mulberries back, in Will's garden. Lascel noted that graceful poise and free swing and be£ore many miles were behind them she had scored point nurpber two-athletic.

They had stopped at a wayside spring. Just then two poorly clothed negro children came by with school books under their arms. Lascel noted the look of tenderness in Helen's face as she talked to the backward children. "Poor pickaninnies," she said, "I am sorry for their lot-I wonder what ought to be done for them-for all of their in this country. Ignorant, diseased, underfed, unwisely reared as they are, they afford us our greatest problem. I enjoy watching men who are really trying to solve some of the parts of their intricate puzzle. Why don't you men do something instead of passing laws in legislatures. Our country needs it."

Then Helen talked of other things. Lascel thought of her in an ideal light, to which another star had been added recently.

They had been discussing politics. Lascel believed that she was patriotic, but her pronouncements on politics confirmed his belief.

"Political expediency is the factor that made Cox the nominee of your party. In other respects, the Democratic convention resembled an attempt of Al G. Field or Ringling Brothers. They wanted someone to run against Harding and he was opportune. Cox never was, is not now and never can be-a leader."

Lascel ventured to break in on her remarks, but she did not heed his remonstrance.

"Why, despite the fact that he was lost in that big 7,000,000 avalanche of 1920, together with his pet orphan, the League of Nations, he still claims the people want it!"

Lascel had to agree she was right. She was a real patriot interested in her country socially and politically. Dainty, athletic and patriotic-but was she religious? Lascel laughed to think of how he would triumph over Munro.

When they reached the peak the whole valley of Anglin lay stretched out before them. For a moment Helen stood and admired the falls of Sinks River far below, or looking farther away, described the fields of blue grass on over toward Lancaster. She stood entranced, the inspiration of the scene around, colored her words giving them a new meaning.

"Look at the falls there-see how the water rushes over the large ledge-see how eager it is to make the plunge. That in like humanity as it rushes on in its course, ever eager to overcome the last obsticle between it and the cool green shadows of perfect peace below. Look at the ribbons of rainbows-see how they cross and recross. There's red brightest of all against the green of the firs and tamaracks! Our lives, Lascel, breaking-

in colored splendor above the greeness of this happy earth!"

To Lascel her animated words were voices from an ideal. Was she dainty ?-listen to her voice and regard for a moment that perfect hand on the rock beside him. Was she patriotic? Sense how alive she was to the greatest need of her own state. Was she athletic? Yonder nine miles away was Berea, they must walk that distance back. Was she religious ?-his ears had just been filled with the chant of a worshipping heart, truly filled with the spirit of the God of the earth. She was ideal-Munro was wrong-an unseen power guides ideal hearts together.

Then he caught her by the hand-she expected that; men grow romantic on mountain tops or by the water side-and told her all that was in his heart-she was his ideal-he wanted her-life would be a dreadful monotony without her.

"I am your ideal, Lascel? Look at the beautiful mist yonder below the falls and all the rainbows shiningso gorgeously. See the rainbows! Now, if two streams of different colored water met above the falls, there would be no pretty mist clouds or rainbows. Let me be frank. You are not my ideal-if you should become better acquainted with me you would find me different from your present ideal woman. A man's ideal woman is his reflection in some woman. The tactful woman is a brilliant reflection of all men. The one she desires for her mate, she chooses, if perchance she can reflect the light toward his reason. Man's reason under the reflected lig-ht of his own desires falters and fails.

"Why do you find these characteristics in me? Because I made myself reflect the soul and self of some man. He loved hiking, I took it up; he is writing a book on the

race question, naturally I am interested; he is a devoted partisan in politics, I try to be; his religion is one of beauty and grace in a live God-that is why I exulted in the scenery. My ideas, many of them are but reflections of his. You stood in the way, the beams fell on you. Ah, yes, you say I am dainty. You really like my pink organdie, and you love these cuffs and this collar-you think they are dainty? Do you think this is dainty?" She held out her left hand, on the important finger she slipped a ring-the gem was a diamond. "He gave it to me before I left."

Lascel recalled the words of Munro-"those you will want you cannot get"-then the idea of Helen, that woman reflects man's impressions, came to him. "I must be wrong," he muttered to himself.

He looked toward the falls-the water fell and dashed into spray, the clouds of mist floated over the fir trees. The rainbows, which a few moments before had arched from rock to rock in entrancing beauty, were gone -the rainbows had fled.

"Come on," he called to Helen, "let us get back down into the valley, I'm hungry."

"J,atb_music<tbarms-?"

JULIET WOODSON '22.

Mother and father and I are indirectly victims of charity. Through the generosity of an indulgent uncleand as a result of a frankly expressed desire on the part of our twelve-year-old brother-we have a little trombone in our home. Innocent and unsuspecting as we were at first-alas for our present intimacy! We marveled at its shiny newness and immense size. (Even now, in times of great emotion, we are often subjected to the somewhat disturbing hallucination that the trombone is playing. Our brother, instead of its being the other way 'round.) But, since that first blissful moment of ignorance, our good manners have been·corrupted to an alarming degree, and our life has become simply one roar after another.

Seven times in the last week has mother been compelled to explain to dazed visitors that the horrible grumbling issuing from the region of the kitchen is neither a sudden warning of an earthquake nor a bomb planted by the new cook. For the past three Saturdays the grocer -boy has delivered our weekly provender with a Daniel-in-the-lion's-den-air. (I strongly suspect though, that the suffering so vividly pictured in his countenance is due in part to the unaccustomed discomfort of keeping cotton in his ears.) And the next-door baby has developed a tendency to wake and find itself hysterical at the third note of Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep!

As for our f amity-our burdens have been well nigh unbearable. The sensations we experience at meal-time are similar to those produced by the steam piano in a circus parade. We breakfast to the accompaniment of

THE MESSENGER

Watermelon Growing on the Vine ( though to be strictly truthful, we are not addicted to the watermelon habit at breakfast). Father carves the meat at dinner in a Turkey-in-the-Straw-atmosphere. And Little Brown Jug works wonders with our glasses of milk at supper time.

Not even on Sunday are we free from all trouble. My favorite hymn used to be the one that began, ''I'l soar and touch the heavenly strings, And vie with Gabriel while he sings, In notes almost divine."

Lately my passion for it has died a sudden death. Soaring to touch any heavenly strings has lost all charm for me-my sympathies-have shifted to Gabriel. But the back-breaking straw descended yesterday when our Musician-in-Embryo announced that he was composing! The finished work will bear the euphonious filte, How It Feels to Have All the Cakes that I can Eat; and its tune has a startling resemblance to the Funeral March.

We know from long experience that the epidemic will not be permanent and that baseball and regular dinner hours will regain their former supremacy. But meanwhile I am collecting odd sofa cushions and stray bits of furniture, and in time I shall have in the basement quite a decent little refuge. I shall call it Enchanting Distance, and I shall compose just one masterpiece. It is to be a Thanksgiving chant and it is to begin,

"O Jazz, where is thy sting? 0 Trombone, thy victory?"

11\e!)pair

R. E. GARST) '22.

The skies are grey 1

The Heavens rain sadness upon me.

Disappointment 1 disillusionment 1 despair

Beat me to my knees.

I will1 I cannot 1 rise.

The gods so will 1 and laugh 1

That sorrow shall be our eternal lot.

My mind trembles

Before the gigantic retrospect of countless years

My body quails

Before the limitless stretches of tomorrow.

My soul sinks down in abject fear

Before eternity. Where shall I turn!

m;bej'Seggar

R. T. J., '24.

The deep bell of the city had sounded three reverbrating strokes. The beggar on the corner raised his cap and looked into the sky. It was a clear open sky that smiled back at him and gave promise of dry, mild weather. A pleased expression softened the sagging, weary wrinkles in the man's face. He reflected pleasantly that good weather would not require him to stay in his cellar lodging. The generosity of mankind swelled under the influence of good weather and the coins that were daily dropped into his hat would increase. The beggar had occupied that particular corner for many years. His leg and one arm were missing testifying to an unfortunate railroad wreck many years earlier. No milestone ever projected itself as loomingly as that railroad disaster overshadowed the beggar's memory. A steel beam had fall en upon both his legs. The rescue party had believed him dead and it was only later that a surgeon had rushed him to the operating table. The massive steel beam had necessitated amputation of both legs. He recalled with a bitterness that was softened little by years, the morning whose cold gray light had fallen across his bed in the hospital when the surgeons had told him of the death of his wife and children. The smallest child had been a year old ; he had been fondling it when the crash came. His wife, sitting opposite him, had smiled upon her husband and her child. The beggar's heart, or its scientific equivalent, contracted when he remembered his wife's smile.

A quarter f:ell into his hat and he mechanically murmured his gratitude. The donor was an old friend

to whom the beggar owed many daily coins. He said several pleasant words in passing and the old man looked up at him thankfully much as a dog looks up at his master. Then a distant sound of many voices came to his ears and he knew at once that the nearby school had released its pupils. They would soon troop by him in groups and lighten his unhappy condition.

The beggar grinned when the first of them passed. They never gave coins and the beggar had long since ceased to expect any but, on the other hand, they invariably cast a happy glow about him. The sturdy energy of childhood that coursed in their young bodies was seemingly passed for the moment into the beggar's diseasewrecked frame. From long experience and habitual observation he had come to know nearly every one of them. He was able to separate the ones who had just begun school from the older ones. The beggar knew that it took seven years to finish the school and he had even followed several of the children through that long period. He dwelt on their faces as they passed and when he occasionally caught a sentence or a few words he would grin in his peculiar manner so that very young children would frequently be frightened by his distorted smile.

A little girl passed. She was probably the beggar's favorite. For four years now she had passed his corner and although he had never ventured a lone word of greeting, he felt himself on quite familiar terms. He could have told her the exact number of times she had been kept in after school and how of ten she had remained away entirely. He even distinguished between the colors of the books in her arm and knew the small red book to be a difficult one. This knowledge sprang from his accidentally hearing her say to another small girl, "that she couldn't and wouldn't study that mean little old red

book." Since that the beggar, on perceiving the small red volume under the arm of a youngster had invariably felt a sense of hostility toward it.

His eyes studied her face as she approached . She was in the midst of a highly colored narrative to her companion and her small red mouth was smiling gleefully. The beggar told himself joyously that sne was very, very happy and he grinned appreciatively. His ugly smile attracted the attention of the girl and for a short moment her childish eyes rested intently upon his face. The beggar stopped breathing; this was a really great moment; she was looking directly at him; she was interested in him as an individual. The child saw the thin, unwholesome lips of a twisted cripple . She shuddered slightly and passed quickly on.

The eyes of the beggar sobered. His joy received its death blow and he quickly turned his face in the opposite direction. Other children were passing and he realized despairingly that they all thought him a loathsome being, one of the unharhonious incidents to be endured on their daily walk from school. His eyes avoided them, fearing that another might notice him.

The beggar knew that the brief incident would torment him for many days. The one being whom he had taken greatest joy in had wounded him. He had delighted in his affection for the small golden-headed child. He had watched her for four years. The unpleasant occurence began to assume the proportions of a catastroph. It was the end of his poem; another tearing disillusionment. Only darkness remained.

These thoughts followed quickly upon one another through the beggar's mind. Not unlike a drowning- man who makes his last plunge, he turned his eyes to the child who was now passing down the street. Possibly he would

never see her again. Possibly she had become frightened by him and would choose another way home. She was still not more than a hundred feet away.

Two men were washing a window in the next block and one of them had paused to light a cigarette. A heavy bucket slipped from his hand. It descended directly upon the small girl. The beggar who saw it gave a hoarse cry and waved his arms, but the tragedy followed cruelly. J\1en, women and children passed him, running toward the spot and crowded about the small huddled figure. The beggar had folded his hands and was muttering unintelligible sentences. A white ambulance carried off the body and a woman passed the beggar with moist eyes.

The beggar caught the coat tail of a bareheaded man ·who had emerged from a near-by house.

"Vlhich one was killed?" he asked.

"The little light-headed one," replied the bare-headed man, shaking his head. "Too bad. I knew the little ~irl well. She lives around the corner from me."

"Y ou'II break it easy-like to her parents," gulped the beggar.

"She didn't have any parents," replied the man, "She's the adopted child of a friend of mine. Her parents were killed in a train wreck."

The beggar stared vaguely for a moment. "Not the old Freeport wreck?" he asked.

The other nodded. "The poor child's father died in the same wreck with both his legs caught under a beam," he added.

Jblers Jn ~ir=<!Castles M. E., '22.

Scientists have discovered much with their microscopes and telescopes. They have theorized still more. But with all their paraphernalia and wild theories, they have never sighted that realm or speculated as to its existence, the realm of air-castles. But who is there who does not know of this wonderful castle-land of the Ego? Miserable, wretched, unhappy mortal who knows not the road, the glorious, carefree road, to this land! Do not scorn him; rather pity him, if there be such a forlorn soul in the universe.

Ah! the glory of it, the joy of it, the complete satisfaction! Whether rich or poor, high or low, we own castles innumerable and all for the price of a bit of imagination! With head high, eyes shining, and lordly mien, we, supreme, sole rulers, survey our domains and smile contentedly. With a slight turn of mind and a breath of imagination as our only tools, we construct, add to, and demolish constantly untiringly and ever with gusto and joy.

'Tis to our castles we run when perplexed and wearied, sad and discouraged, for there Ego reins supreme, and for a while, at least, we are what we wish to be and might have been. How many wonderful scenes are enacted, glorious, triumphant scenes, planned, managed, acted by Ego! And what a relief, what a balm to our harassed souls and trampled selves l How many enemies have been routed, how many oratorical triumphs have been delivered, how many delicious romances have been held in these air-castles l First to one and then to another we run, some old and a bit weather-beaten, some

with many additions and changes, some obviously new, but all ours to do with as we please and to revel in. We loiter, we play, we strut, we act-we idle extravagantly, delightedly. Nobody to say us nay; nobody to dub us fools!

But, gentle reader, take care to choose a favorable time for your pilgrimage to your mental land of play. 'Tis from sad experience I advise. No doubt, I have forgotten everything that I was supposed to absorb in this class in the way of knowledge, but this I shall never forget. I disliked that teacher intensely, and I ached to triumph over her in some way. As I sat there, I traveled to one of my air-castles, and there, with outraged dignity and much pomp and feeling, I was gently, but firmly and effectually, lecturing said teacher. She cringed. I glorified in it. She whined? I grinned diabolically. She begged for mercy! I drew myself up haughtily-"Well, come back and join us, and see if you can answer something!" in a harsh, nasal tone . Gone was my haughty poise, my triumph, my delight! Stuttering, stammering and with a bump and a blush, I came back to earth-and to mortification and humiliation. The air-castle was all right, but the time! Oh! unhappy me-! How many of you have favorite times, favorite haunts-for your travels? How many of you look forward eagerly to the hour just at dusk before an open fire or the first delicious "slumbery" minutes just before you fall asleep? Ah! what peaceful, undisturbed, heaven-sent hours for air-castles! Truly, I believe they are the hours made especially for air-castle idlers. I attribute them to the three old sisters, and to them I extend passionate thanks for this land of triumphs, this realm of dreams, this Utopia of the Ego.

l\ai~ing ~wentp

W. 0. CARVER, '23.

"Yes, siree," Old Tim laid three aces and two queens on the table, drew in a hand full of chips, and lit a cheap cigar. "'Slim' Ellis was the best man I ever worked with. That boy was down right clever. Why he had enough sense to be President of these United States. I remember one he pulled over that was the cleverest I ever saw-

"Y es, I am sticking in ; gimme three cards-"

"It was while we were working down in South Carolina. I remember just the same as if it were yesterday. I ran up on 'Slim' in Joe Stein's place in Greenville one Monday morning. He called me back in a little side room and told me he had a great scheme to make some money if we could just raise some capital. Well, I had a twenty dollar bill and that was all. I laid it on the table-

"I'm looking, what have you got? That's no goodI've got three kings"-

"W ell, as I was saying, I laid my twenty out on the table. But Slim shook his head.

" 'Twon't do,' he said, 'we've got to have forty to pull this little graft.' "

"'There's a game going on up stairs,' I suggested. " 'Won't do,' said Slim; 'That's too slow and besides it's not certain.'

"Well, sir; that boy started thinking and pretty soon a smile sort o'lit up his face and I knew right away he'd got an inspiration. He told me-

"I'm out o' this hand"-

"He told me go get some letter paper and an envelope and to borrow old Stein's typewriter and then wait

for him; he'd be back in a minute. Then he took my twenty dollars and was gone. When he got back I had everything ready. He walked into the room, took off his hat and smiled.

" 'Well, how do I look," he asked. He had gotten a shave and his hair was brushed till I didn't h ·ardly know him.

"'What's your game?' I asked. 'Are you going to a pink tea and rob all the ladies of their jewels?'

"'Well, hardly,' he says.

"I guess it's about my deal'-

"Then he emptied one of his pockets on the table. It was what was left of my bill after he got a shave, nineteen dollars and eighty-five cents, mostly in chang-e, with just a few ones."

"Old Time" had shuffled the cards, but he didn't deal them. He was getting interested in his story. None of the boys said anything; they never said anything when Old Tim was telling a story.

"I wondered what in the hell he was going to do with all that change, but I didn't ask him. He took one of the envelopes I had got from old Stein and addressed it on the typewriter to some New York Company. Then he folded the sheet of paper like it was a letter and put it in the envelope, and last of all stamped it.

"'Now, I guess we are ready,' he says, and I agreed. He took the money and the addressed letter and another blank envelope and off we went, him leading the way. We got out on Main street and turned up until we came to Blake's Hardware store, right on the corner of an alley.

" 'Here we are,' he says.

" '\Nhere? ?' says I.

" 'Right here,' and he pushed me into the pool room next to the hardware store; 'now hold my coat and hat. and wait.'

"He took the letter and money and ran across the street into a drug store on the corner.

"He was gone about fifteen minutes, I guess, before he came back-smiling.

" 'Easy as pie,' he said as he slipped on his coat and hat. Then he pulled a blank, sealed envelope out of his pants pocket and tore it open. There was a brand new green twenty dollar bill !

" 'How did he get it?' you ask. That is exactly what I wanted to know. It was simple enough, too. I could have done it myself if I had the brains to think it out. He simply ran across the street in his shirt sleeves and up to the cashier of the Corner Drug Store, and dumped a pile of change in her window.

" 'I'm with Blake's Hardware Store, across the street. We've got to send a payment off to New York, and not a twenty in the house. I wonder if you could let me have one for this change?' The girl rang a no sale, and pushed him a twenty. While she was counting his change he put the twenty in the blank envelope and sealed it up. Of course, when she saw he was fifteen cents short, she called him.

"'Is that so?' he says. '\\Tell, well; Mary's made a mistake again. I guess the boss will have to fire that g-irl. Here I've already sealed up the twenty, but you can hold the letter while I take this change across the street and have her straighten it out.' With that he smiled and pushed her the letter addressed to the New York firm, and she smiled too. But I don't guess she smiled when she opened that letter after Slim didn't go back.

Let me see; am I dealing." Old Tim chuckled to himself as he passed around the cardboards.

~frican 19rums

BOSWELL U. DAVENPORT, '22.

Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

Sullen drums are slowly, slowly, slowly-booming; Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

Booming from the mountains, calling, calling, dooming Warriors, headsmen, chieftains; places far remote

Thrilling to the solemn music of that war-note; Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

Bon-fire, crackling signal, roars and swishes, leaping, Dancing with the dancing, black-sknined devils, keeping Lit the rounded summit of the mountain, glowing, Lighting up the crouching, naked figures, showing Tribal doctor squatted in the circle, bumping, Thumping, thumping, with a human thigh-bone, thumpmg

Hollow log end-covered by tight stretched, goat-skin drumheads;

Prancing fighters jab and shake their gleaming spearheads, Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

Dart and swirl, shake and wave their shields of leather; Ceaseless rolls that peaceless thunder, rumbling weather

Bringing screaming death and lurid skies at dawn; One pitch, one tone, one note, pounding on, on, Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

Tireless, cumulative monotone that broods

Drones incessant gloom throughout the solitudes; Bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwm-ba, bawwmba, bawwm-ba;

ELSIE WARE, '22.

There came to the woman by the fire the cheery click of the key in the latch. It was quickly followed by a man's firm steps approaching the room in which she waited. As he paused on the threshold, he noted the beckoning, gleaming fire, crackling in the open grate. He saw the fire-light fitfully playing over the old mahogany book-cases. His look rested for a minute on the table littered with books and magazines. Then his glance came lingeringly to the figure in the deep arm-chair. His dark blue eyes lighted up with an inner fire and his mouth curved into a smile of worship. He looked with deep eyes at the comfortable figure in the big chair and studied the calm, smooth face under the crown of gray hair. A welcoming smile spread over his thin, lined face as he hurried to her side. With a gentle movement, he bent and kissed her strong mouth. It was a wordless benediction.

When she had left to attend to the final preparation of his dinner, his gaze wandered over the comforts of the room, the room her hands had made home-like. From the table he took a small volume. Tenderly opening the yellow pages, he found the passage he was seeking.

Ah, fill the cup :-what boots it to repeat How Time is slipping underneath our feet: Unborn to-morrow and dead Yesterday, Why fret about them if To-day be sweet!"

Softly canning the words of the Rubaiyat, he gazed into the sparkling embers. His mind painted in them the ministering woman that he called wife. As in review before him, he recalled the untiring efforts to make his frail existence easier, to take every load from him that

might weaken his sickly body. Her every care was for him and his heart was filled with love of her.

The last light of the dying day cast its brilliance into the shadowed room. It rested on the spare figure of a gray-haired man as he knelt by the big, white bed. In his arms he supported the pale form of a dying woman. The rosy glow passed over their faces and imparted a look of divine radiance to them. The silence was broken by a weak voice, speaking softly. "Don't grieve, Ned, when I'm gone: You have nothing to regret. Your every thought has been for my comfort and pleasure. Ned, you haven't failed to let me know of your love for me. I'm going, Ned, but-, dear-, I'll-be-waiting." The voice trailed off. The man gave a bewildered look and with a dry sob held her to him. Convulsions shook his wasted body as he tried to held sleep. His grief spent, he laid her gently on the pillows. Arising, he opened the door to his friends.

He clothed her in her wedding garments, and as he had received her, so he gave her back. Gazing on her for the last time in this earthly form, he saw her as the bride he had led to the altar. A faint glow was on her cheeks, and her face was in peaceful repose. With a long, lingering look, he turned away.

A breeze fluttered through the open window and brushed the cheek of the gray, wrinkled man in the big arm -chair. It passed lightly over the piled-up table and with a light touch, moved an open page. It wafted over and died away. There came into the room the first notes of the spring birds, but the man did not heed them. His head rested wearily against the tall back of the chair. A look of utter desolation was about him. His clothes were rumpled and unkempt. His white moustache had grown long and drooping. His white hair was uncut and dis-

ordered. He stared unseemingly before him with his hands folded idly in his lap. With a slow movement, he turned to the books on the table, then with an impatient sigh turned away. Even his books, his ever-steadfast friends, held no comfort or pleasure for him now. His mind could not be turned away from its overwhelming sorrow. As he glanced at the room, now so lonely, he was reminded of the one who would never cheer him again. His thoughts came back to her last words to him. She would be waiting, but where?

Suddenly there came to him, the opening notes of a piano. A voice, tender and young, softly began to sing. At first his mind refused to listen, but as the sweet, clear voice throbbed its song, he was held in its power.

"Thou art the blood of my heart of hearts, Thou art my soul's repose;

But my heart's grown numb, and my soul is dumb, Where art thou love, who knows, who knows?"

As the voice held the last notes, his face lost its tragic look of grief, and the softening tears trickled down the worn cheeks.

"Thou art the hope of my after years, Sun of my winter snows;

But the years go by 'neath a clouded sky, When shall we meet, who knows, who knows?"

A quick sob came from him, and a light broke over the sorrow-aged face. The dark blue eyes lighted up with an inner fire, and his mouth curved in a smile of almost worship. Wiping the tears away, he took from the table a small volume and tenderly opening the yellow pages, softly read:

"Ah, my Beloved, fill the cup that clears

To-day of past Regrets and future FearsTo-morrowt-Why, to-morrow I may be Myself with Yesterday's Sev'n Thousand Years."

!}outb

GLADYS SHA w, '22.

Once upon a time when the stars were young, and the world was full of wonderful newness, Youth set forth on a quest. Now the stars are old, but Youth is still aseeking with all the eagerness of the setting-forth. Just to be young is to be a-thrill with a wanderlust and a wonderlust. Then one meets Adventure across a city street. Then one sees Romance lurking behind every closed window. R. L. S. says, "youth is the time to go flashing from one end of the world to the other both in mind and body; to try the manners of different nations; to hear the chimes at midnight; to see sunrise in town and country; to be converted at a revival; to circumnavigate the metaphysics, write halting verses, run a mile to see a fire and wait all day long in the theater to applaud Hernani."

Hernani was truly the product of youth. Indeed the triumph of Romanticism was the triumph of young thought. Who but youth would have the temerity to assail the impregnable citadel of the classicists, and from the very boards of the Theatre Francais? Who but youth or a poet would have appeared in the red waistcoat and green trousers of Theophile Gautier? But then he might have appeared as the Queen of Sheba, for he was both youth and poet.

No poet is ever old. The day he feels the hand of age he ceases to be a poet. Poetry is the language of youth. Its boundless vitality and bubbling joy scorn the halting commonplaceness o:t prose. They need the lyric sweep and flowing melody of verse for adequate expression. The poet exists in all young things to a more or less marked degree. Shelley could share his exquisite, ethe-

real fancies with the world. The ordinary youth feels a hot choking feeling in his throat when the organ swells forth and recessional, filling the church with thunderous melody. He knows that wind in his hain and rain in his face sets his blood leaping and bounding through his veins. Ordinary youth is poetic, but inarticulate.

Youth has no age limit. Of course, for some, it is harder to be young at eighty than at eighteen. Some rare spirits grow younger as the swift seasons roll. The ponderous weight of years and experience that so crushes the others, hardens and strengthens the muscles of their spirit, keeps their imagination flexible. They drink daily of the much-sought-after fountain. They know that old age and death are not inevitable. They know, instead, that youth is eternal.

There is a French proverb that Stevenson quotes, " Si J eunesse savit, si vieillese pouvait." The last half may be right, but what is wiser than the eyes of youth. Youth is free to roam the wide world over. Who has not secretly fancied himself a pirate, a bold swash-bucklingbuccaneer who roved the Spanish Main? Who has not sallied forth from the pastern gate of a moated castle, a gallant knight in glittering armor to do battle for some lady fair? One moment one is a boleroed matador of the Spanish arena. The next one rests in the shade of a lonely palm on the white hot plain of a trackless desert. Today one climbs the snow-capped Alps, and maybe risks one's life for one exquisite blossom, a fairy edelweiss. Tomorrow one will stand by a wayside shrine, drenched in the fragrance of cherry blossoms, and listen to the temple bells of old Japan. Youth digs gold in the frozen Klondike. Youth hunts big game in the wilds of Africa. Youth sees through the garishness and the sordidness of the fruit-vender to the sunny skies and vine-covered hills

of his native Italy. What need has Youth of a magic carpet or an Aladdin's lamp?

Oh, Youth is the time for dreams, dreams of love, of happiness, of great things to be done. Youth has no past. The future is one exquisite rosy cloud whose lining is of shining gold. One crosses to the rosy land of air castles over the gorgeous rainbow bridge of the present. When one is young, the present is the time to live, and dream, and love.

Yet Youth is not forever dreaming. The idle fancies of a summer's day will yield to the clash and din of a battle royal. When fire runs in one's veins for blood, we can meet the rush of the storm with up ..flung- hands. Youth is the time to dare great things, to act! It is the youth of the world that can stand the sµock of an epic day. The maid of Orleans was a child when she caught the vision. She was hardly more when they burned her in the market place of old Rouen, yet she had led the armies of her King to victory-,. The flash of her sword and the fire of her spirit swept all before them. Today the sound of her name can kindle the soul of France to a pure white flame of patriotism. Have not you heard of the spirit of legion of Mons?

Who is it that rests beneath the gold of the wheat and the red of the poppies that blow in the fields of Flanders? The youth of the world. The young, young dead. Who is it that sleeps alone in sea-girt Skyros, that "corner of a foreign field that is forever England?"

Oh, it's good to be young in winter. It's better still to be young in June; but best of all is to be young in the springtime. Then youth has time for singing. All the world is bursting into song. The tinkling music ·of the running brooks, the joyous caroling of the birds, the song of the rising sap, find an echo in the heart of us. "All

suddenly the air comes soft." Everywhere there is the feel of buds swelling and things beginning to grow. It is in springtime when the woods are white with dogwood, that I can hear the haunting, teasing sweetness of the pipings of Pan. For you know, "they do say in Ireland that the pipes of Pan be the witch of Happiness-ever pursued, yet ever fleeding."

Yes, Youth is all for gladness. There is so much to do, to hear, to see, and there is so much to live, why lose a glimpse of the sky through the trees, or miss one thrilling note of the robin's song? Now is the time for rapture and madness. And if there be a little weeping, what matters it? I heard somewhere that rainbows spring from Youth's incongrous tears.

l\cwarb

J. R. SAUNDERS, '22.

"Thou Spirit of the Hopes of Men, One moment, I would speak with thee! Thou who dost flit from mount to glen Touching each soul from sea to sea.

Far in the future; thou shalt know, After the toil and sacrifice, Then shalt thou come to me, and show To men, that I have paid your price.

That I have labored long and well For them; that they might see the dawn And grow more perfect; mark you! tell Them all o £this, though I have gone."

<!&n·jicing a ~unbap ~cbool m'.cacbcr

VIRGINIA MONCURE, '22.

Sunday is far from being a day of rest when you try to becalm and enlighten ten little girls, who, as if their whole future destinies depend upon it, are bent upon imparting to you all the events of their past lives, and not a few of those adventures which are yet to come. I hear how Trixie, "the lady next door's little dog," wages war on all cats in his vicinity, and suffers no remorse of conscience therefrom; how the cow that grazes in the field near Ursula's house, deliberately walked up the steps of the Christian Science Church, down the aisle, and into the chancel, where she lay down and went to sleep. The sexton, in the meantime, had fled, tearing his hair. On Sunday morning, according to Ursula's version, the minister was somewhat astonished upon seeing a cow mounting laboriously into the pulpit.

When Ursula began the story, I am practically certain that she had no intention of letting the cow enter the church, but upon being asked, "What happened next?" when she had reached the point where the bovine hesitated on the porch of the church, she must have felt that it would never do to disappoint her enraptured audience. Thus encouraged to continue her narrative, she supplied with imagination what she lacked in actual facts. I am sure she felt duly repayed for her gallant efforts, for the story was uproariously enjoyed more than any told heretofore in our midst. Each Sunday morning the class inquires diligently concerning the possibility of new escapades on the part of the cow. They never seem at a loss for answers, be they right or wrong. After telling them that Simon was called

Peter, meaning "a strong rock," I asked, "Nancy, why was Simon called Peter?" Nancy, making superhuman efforts to think, finally, with a proud look around at mere mortals, says, "They called him Peter for a nicknameand I've got a cousin named Peter!"

"When in doubt, smile," is the policy maintained by Caroline, who has never to my knowledge answered a single question during her sojourn in our midst. After the others have covered t1i~mselves with glory by reciting the text, I approach Caroline on the subject. Being shy,

"She looked down to blush, and she looked up to sigh, With a smile on her lips and a smile in her eye;" but never a word comes from her lips. I repeat the text for her sole benefit," 'Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with they might.' Now you say it, Caroline. 'Whatsoever thy'-what? "I wait in suspense, hoping against hope .

With great solemnity, and all in the same breath, she says, " 'Whatsoever thy what," and feeling that she has done her duty, she reclines on her laurels 1 so to speak.

· At times I am well nigh overcome with their entreaties to sit by me. In , my embarrassment at this open disclosure of affection, and in my desire to seem impartial, I resort to a practice of my childhoo-d days, and count, "Eenie, meenie, minie, mo; etc.," with the children chiming in at the end. I feel. that the author of the Primary Teacher's Helper," that mainstay of all Sunday School teachers, . made a grave mistake in omitting-mention of this method of deciding such v.ital questions as who shall carry the banner in the Easter celebration, who shall take up the collection next Sunday, etc. Anyone, hearing us count in chorus, would no doubt cease to_wonder why the

younger generation is what it is, if this is what it learns at Sunday School.

When I am notified that our class is to receive a new member in the person ·of one Hortense Bugg, I immediately instruct the class not to so much as smile at her name, when the roll is called. With much clapping of hands over months to suppress laughter, and much rolling of gleeful eyes, they await her entry. Her little brother, Ivanhoe Bugg, feeling his importance, conducts her into our presence. The class, visibly conscious of its responsibility, receives her with open arms and manifest joy. Presently Lillian, patting her with great affection, says, "You cert'n'y have got a pretty first name. At the Easter celebration, together with keeping the children in line, and preventing Ursula, who triumphantly carries the banner, from singing entirely out of time; and telling Nancy not to form the habit of stepping on the heels of the little boy in fact, and so on ad infiinitum I begin to have a fellow-feeling for the Old Woman in the Shoe. But after all, it is such a joy to hear all those little innocents, when called upon to recite, pipe forth the text for the day, " 'Let us do good unto all,' " and then a little proud of their achievement, settle back in their seats for a dandy earned rest.

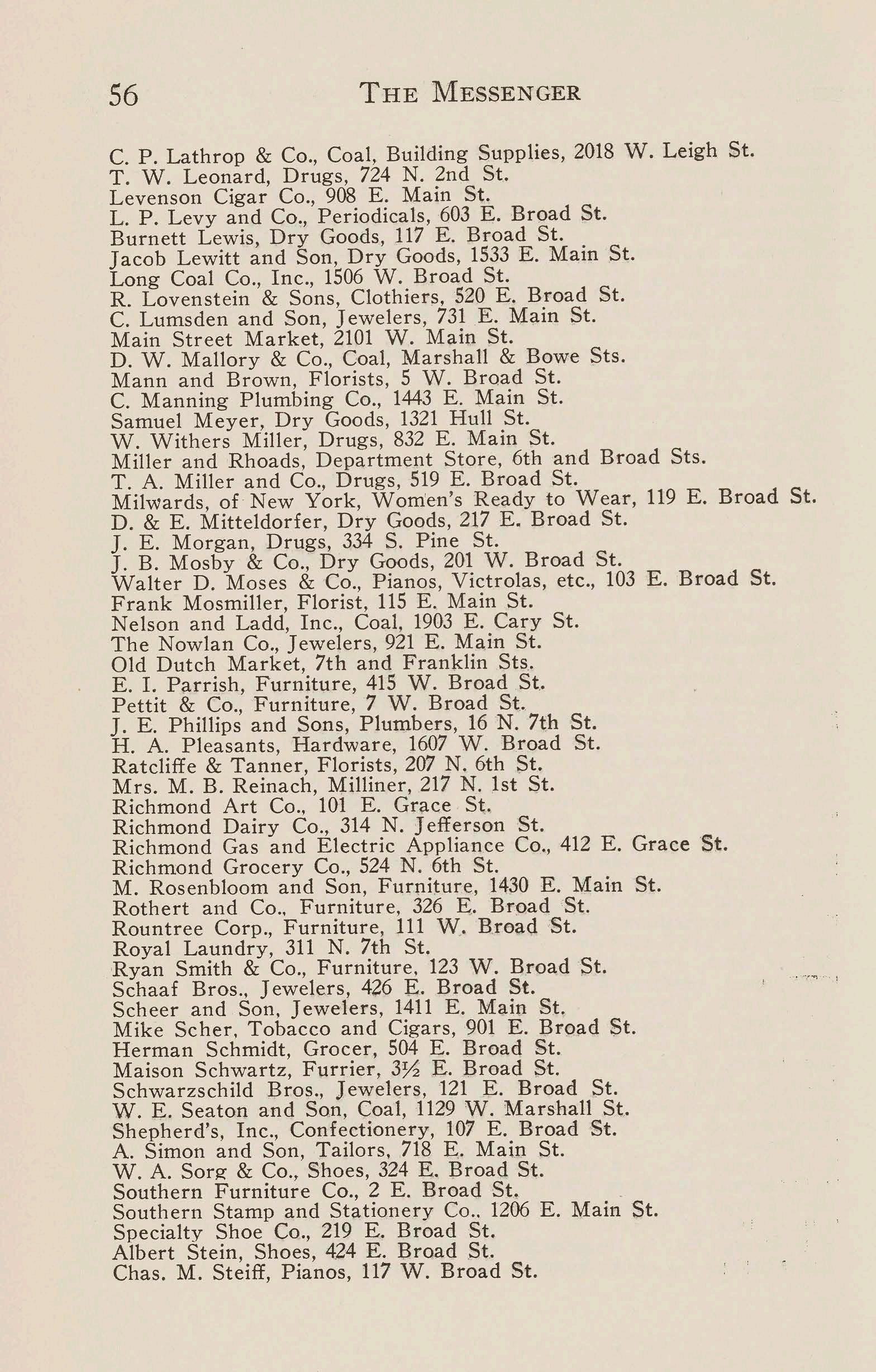

The University of Richm ond publishes the following list of Retail Merchants of Richmond, Va., for the information of students and faculty, and as a token of appreciation of the active and invaluable assistance given the University in the Million Dollar Campaign by the Retail l\tierchants Association:

A. A. Adkins & Co. , Furniture, 1204 Hull St.

J. T. Allen & Co., Jewelers, 1323 E. Main St.

B. P. Ashton, Grocer, 616 E. Marshall St. Bell Book & Stationery Co., 914 E. Main St.

S P. Bass, Men's Furnishings, 1624 Hull St.

0. H. Berry & Co., Clothiers, 1019 E. Main St.

R. L. Booker, Drugs, 2001 W. Main St.

H. Carl Boschen, Shoes, 23 W. Broad St.

J. P. Bradshaw, Clothier, 600 E. Broad St.

E. L. Brandis, Drugs, 2601 Park Ave.

D. Buchanan & Son, Jewelers, 225 E. Broad St. Burk & Co., Clothiers, 800 E. Main St.

R. E. Burks & Co., Furniture, 212 W. Broad St. Bergman's, Women's Ready to "\Near , 3 E. Broad St. Braus, Women's Ready to Wear, 309 E. Broad St. Catlett Electric Co., Jefferson & Grace Sts.

W. S. Cavedo, Drugs, Floyd A ve . & Robinson St. Chaddick Motor Supply Co., Inc., 713 W. Broad St.

J. H. Chappell & Bro., Plumbers, 309 E. Main St.

R. E. Chelf Drug Co., Drugs, 1201 W. Broad St. Childrey Drug Co., Drugs, 101 ,E. Broad St.

A. P. Chisholm, Grocer, 2800 Hull St.

R. L. Christian & Co., Grocers, 512 E. Broad St.

A. B. Clarke and Son, Hardware, 510 E. Broad St.

The Cohen Co., Department Store , 11 E. Broad St. Harry V. Cole, Confectioner, 204 N. 4th St. The Corley Co., Piano s, Victrolas, etc., 213 E. Broad St.

A. N. Cosby, Grocer, 1400 3rd Ave., H. P.

S. H. Cottrell and Son , Coal, 1103 W. Marshall St.

W. D. Crenshaw, Tobacco and Cigars, 1100 E. Main St.

M. Crighton, Millinery, 113 E. Broad St. Crump and West Coal Co., 1811 E. Cary St. Dabney Bros. & Co., Clothiers, 6 E. Broad St.

F. W. Dabney & Co., Shoes, 433 E. Broad St.

A. J. Daffron, Furniture, 1438 Hull St.

Danforth Millinery Co., 216 N. 2nd St.

Dann Millinery Co., 5 E. Broad St.

Dennis Auto Supply Co., 301 W. Broad St.

C. H. Dorset Hardware Co., 2600 Hull St.

Dreyfus & Co., Women's Ready to Wear, 201 E. Broad St.

A. Eichel & Co., Butchers, 330 N. 6th St.

W. E. Ellis, Grocer, 724 W. Broad St.

Stephen A. Ellison & Co., Coal, 602 E. Main St.

Epps and Breitstein, Clothiers, 812 E. Main St.

THE MESSENGER

J. E. Eubank, Grocer, 2623 E. Broad St. Fannye Millinery Co., 204 N. 1st St.

Adam Feitig, Grocer, 119 E. Main St.

Lee Fergusson Piano Co., 119 E. Broad St. Fourqurean, Tem'ple & Co., Dry Goods, 101 W. Broad St. The Freed Co., Women's Ready to Wear, 215 E. Broad St. Galeski Optical Co., 737 E. Main St. Gans-Rady Co., Clothiers, 816 E. Main St.

W. R. Gibbs, Meat Market, 1821 Hull St.

W. A. Gills, Grocer, 2401 W. Main St. Gills and Atkins, Haberdashers, 917 E. Main St.

The Gift Shop, 320 E. Grace St.

R. E. L. Glasgow, Hardware, 1518 W. Cary St. Globe Clothing Co., 613 E. Broad St.

Goode's Shoe Store, 1447 E. Main St. Grant Drug Co., 626 E. Broad St.

W. T. Grant Co., 25c. Dept. Store, 321 E. Broad St. Wm. A. Green, Tailor, 519 E. Main St.

Meyer Greentree, Clothier, 701 E. Broad St. C. Fred Grimmell, Plumber, 212 E. Broad St. Frank B. Grubbs, "Paragon Pharmacy," 801 W. Cary St.

Chas. Haase and Sons, F urriers, 119 W. Broad St. Henry R. Haase, Furrier, 207 E. Broad St. G. L. Hall Optical Co., 211 E. Broad St.

The Hammond Co., Florists, 101 E. Grace St. C. B. Harper Hardware Co., 510 E. Marshall St. Harrison's Drug Store, 3901 Williamsburg Ave.

S. H. Hawes & Co., Inc., Coal, Building Supplies. 1801 E. Cary St. Hay and West, Grocers, 305 N. 6th St.

Hellstern Bros., Cigars and Tobacco, 633 E. Broad St. Hofheimer Bros. Co., Shoes, 300 E. Broad St. Hopkins Furniture Co., 25 W. Broad St. Ho lladay Co., Auto Accessories, 629 E. Main St. Howell Bros., Hardware, 602 E. Broad St. Hub Clothing Co., 717 E. Broad St. Hunter & Co., Stationers, 105 E. Broad St. H. C. Hurdle, Drugs, 1101 W. Cary St. Hutzler and Co., Dept. Store, 1201 Hull St. Huyler's Confectioner, 221 E. Broad St. Jacobs and Levy, Clothiers, 705 E. Broad St. Jahnke Bros., Jewelers, 912 E. Main St.

J. A. James, Jewelers, 633 E. Main St. W. H. Jenks, Electrical Contractor, 621 E. Main St. A. E. Johann, Drugs, 827 W. Main St. Jonas Millinery Co., 115 E. Broad St.

Jones Bros. & Co., Furniture, 1418 E. Main St.

Chas. G. J urgen's Son, Furniture, 27 W. Broad St. Kann's, Inc., Women's Ready to Wear, 109 E. Broad St.

Kaufmann & Co., Millinery and Women's Reddy to Wear, 401 E. Broad St.

C. D. Kenny Co., Tea and Coffee, 606 E. Broad St. G. R. Kinney Co., Shoes, 604 E. Broad St. Kirk-Parrish Co. , Clothier, 605 E. Broad St.

John F. Kohler & Sons, Inc ., Jewelers, 209 E. Broad St. S. S. Kresge Co., Sc, 10c and 25c Stores, 429 E. Broad St. Lane-Bowles Co., Auto Supplies, 521 W. Broad St.

C. P. Lathrop & Co., Coal, Building Supplies, 2018 W. Leigh St.

T. W. Leonard, Drugs, 724 N. 2nd St.

Levenson Cigar Co., 908 E. Main St.

L. P. Levy and Co., Periodicals, 603 E. Broad St. Burnett Lewis, Dry Goods, 117 E. Broad St.

Jacob Lewitt and Son, Dry Goods, 1533 E. Main St. Long Coal Co., Inc., 1506 W. Broad St.

R. Lovenstein & Sons, Clothiers, 520 E. Broad St.

C. Lumsden and Son, Jewelers, 731 E. Main St. Main Street Market, 2101 W. Main St.

D. W. Mallory & Co., Coal, Marshall & Bowe Sts. Mann and Brown, Florists, 5 W. Broad St.

C. Manning Plumbing Co., 1443 E . Main St. Samuel Meyer, Dry Goods, 1321 Hull St. W. Withers Miller, Drugs, 832 E. Main St. Miller and Rhoads, Department Store, 6th and Broad Sts.

T. A. Miller and Co., Drugs, 519 E. Broad St. Milwards, of New York, Wom 'en's Ready to Wear, 119 E. Broad St.

D. & E. Mitteldorfer, Dry Goods, 217 E. Broad St.

J. E. Morgan, Drugs, 334 S. Pine St.

J. B. Mosby & Co., Dry Goods, 201 W. Broad St.

Walter D. Moses & Co., Pianos, Victrolas, etc., 103 E. Broad St.

Frank Mosmiller, Florist, 115 E. Main St.

Nelson and Ladd, Inc., Coal, 1903 E. Cary St.

The Nowlan Co., Jewelers, 921 E. Main St.

Old Dutch Market, 7th and Franklin Sts.

E. I. Parrish, Furniture, 415 W. Broad St.

Pettit & Co., Furniture, 7 W. Broad St.

J. E. Phillips and Sons, Plumbers, 16 N. 7th St.

H. A. Pleasants, Hardware, 1607 W. Broad St.

Ratcliffe & Tanner, Florists, 207 N. 6th St.

Mrs. M. B. Reinach, Milliner, 217 N. 1st St.

Richmond Art Co., 101 E. Grace St.

Richmond Dairy Co., 314 N. Jefferson St.

Richmond Gas and Electric Appliance Co., 412 E. Grace St.

Richmond Grocery Co., 524 N. 6th St.

M. Rosenbloom and Son, Furniture, 1430 E. Main St.

Rothert and Co .. Furniture, 326 E. Broad St. Rountree Corp., Furniture, 111 W. Broad St. Royal Laundry, 311 N. 7th St.

Ryan Smith & Co., Furniture, 123 W. Broad St.

Schaaf Bros., Jewelers, 426 E. Broad St. Scheer and Son. Jewelers, 1411 E. Main St.

Mike Scher, Tobacco and Cigars, 901 E. Broad St.

Herman Schmidt, Grocer, 504 E. Broad St.

Maison Schwartz, Furrier, 3½ E. Broad St.

Schwarzschild Bros., Jewelers, 121 E. Broad St.

W. E. Seaton and Son, Coal, 1129 W. Marshall St. Shepherd's, Inc., Confectionery, 107 E. Broad St.

A. Simon and Son, Tailors, 718 E. Main St.

W. A. Sorg & Co., Shoes, 324 E. Broad St.

Southern Furniture Co., 2 E. Broad St. .

Southern Stamp and Stationery Co .. 1206 E. Main St.

Specialty Shoe Co., 219 E. Broad St.

Albert Stein, Shoes, 424 E. Broad .St.

Chas. M. Steiff, Pianos, 117 W. Broad St.

THE MESSENGER

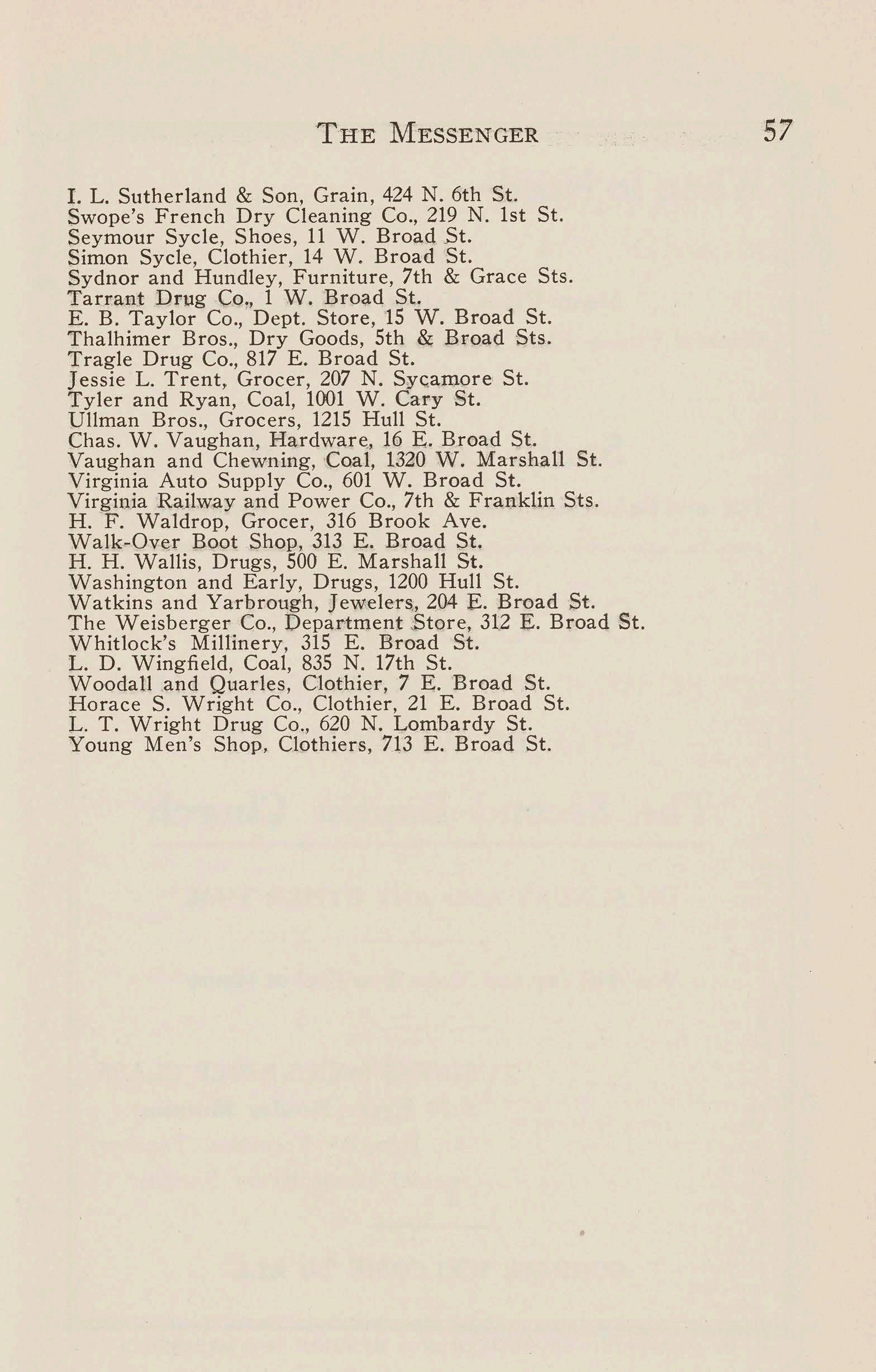

I. L. Sutherland & Son, Grain, 424 N. 6th St.

Swope's French Dry Cleaning Co., 219 N. 1st St.

Seymour Sycle, Shoes, 11 W. Broad St.

Simon Sycle, Clothier, 14 W. Broad St.

Sydnor and Hundley, Furniture, 7th & Grace Sts.

Tarrant Drug Co., 1 W. Broad St.

E. B. Taylor Co., Dept. Store, 15 W. Broad St. Thalhimer Bros., Dry Goods, 5th & Broad Sts.

Tragle Drug Co., 817 E. Broad St.

Jessie L. Trent, Grocer, 207 N. Sycamore St.

Tyler and Ryan, Coal, 1001 W. Cary St.

Ullman Bros., Grocers, 1215 Hull St.

Chas. W. Vaughan, Hardware, Hi E. Broad St.

Vaughan and Chewning, Coal, 1320 W. Marshall St.

Virginia Auto Supply Co., 601 W. Broad St.

Virginia Railway and Power Co., 7th & Franklin Sts.

H. F. Waldrop, Grocer, 316 Brook Ave.

Walk~Over Boot Shop, 313 E. Broad St.

H. H. Wallis, Drugs, 500 E. Marshall St.

Washington and Early, Drugs, 1200 Hull St.

Watkins and Yarbrough, Jewelers., 204 E. Broad St.

The Weisberger Co., Department Store, 312 E. Broad St.

Whitlock's Millinery, 315 E. Broad St.

L. D. Wingfield, Coal, 835 N. 17th St.

Woodall and Quarles, Clothier, 7 E. Broad St.

Horace S. Wright Co., Clothier, 21 E. Broad St.

L. T. Wright Drug Co., 620 N. Lombardy St.

Young Men's Shop, Clothiers, 713 E. Broad St.