ilt s ,atttgtr

In this issue

PETTON PLACE

Reviewed ALSO

By DICK BROWN

Edi tor

Connie Butler

Associate Editor

Ken Burke

Business Manager

Frank Schwall

Art

John Davis

Art

Jehane Flint

Phebe Goode

Earlene Hard

Virginia Harris

Margaret Williams

Oriti

Tommy Atkins

Dick Bell

Sally Finch

Nita Glover

Virginia Harris

Wendy Kalman

Ted Nordenhaug

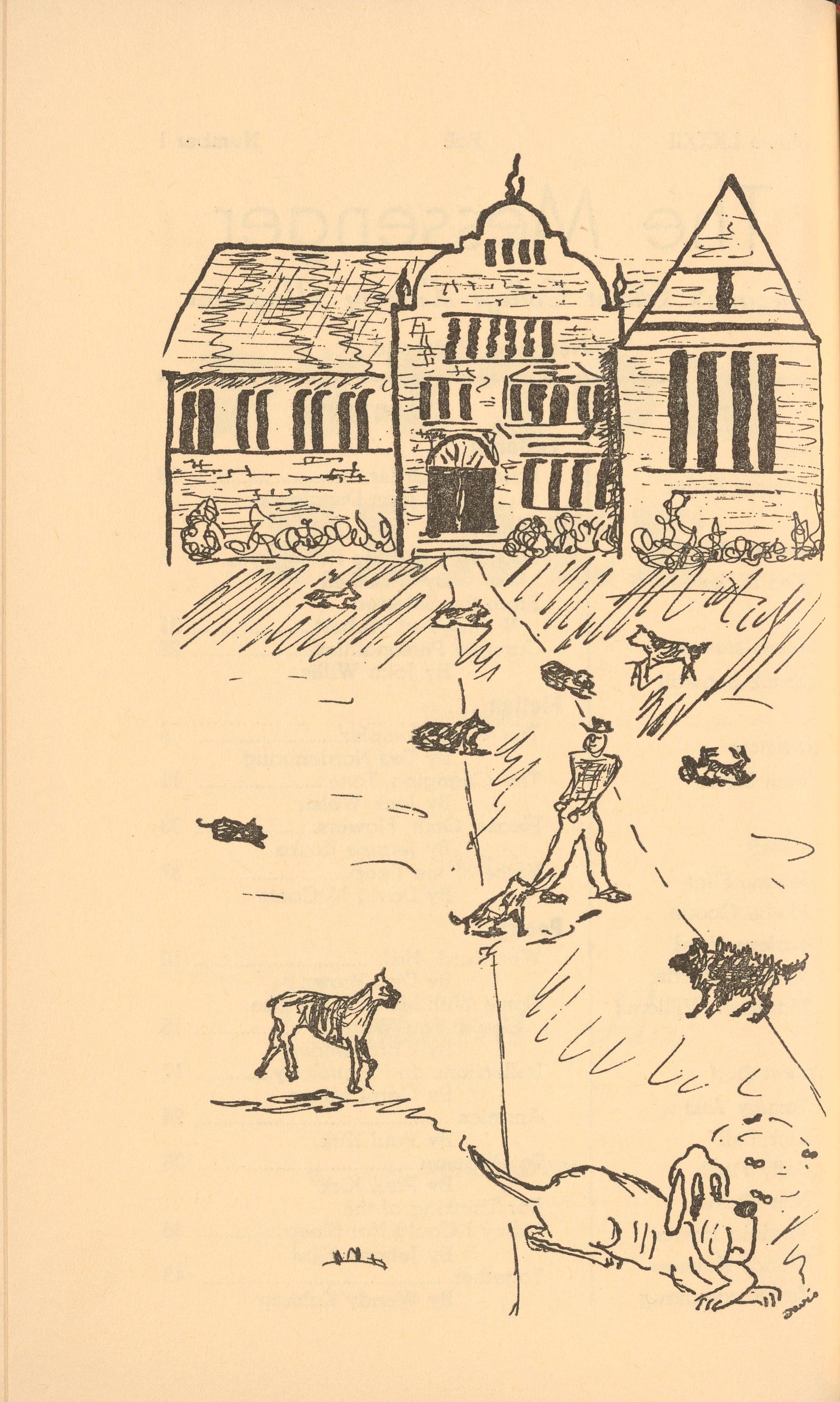

Dog Meat and The Refectory

By DICK BELL '58

It is becoming increasingly difficult to make one's way about the Richmond campus without running into or stumbling over one or more members of our campus canine population. I say "member of our canine population" without in the least inf ering they would be recognized as such by any learned doctor of the biology department. Only in shape do they retain even a vague resemblance to typical members of their breed. Even here it cannot always safely be determined whether they are canine or some other species, since their rib cases are scarcely covered by flesh, their tails are invisibly tucked between their legs, and their faces rival in blankness those of most students.

Even this does not state the case fully. The proverbal "friskiness of a pup" is no where to be found among this group. They lie the day long about the campus wherever their least efforts take them. They move only to secure food and to fulfill other natural necessities. They refuse, as I have intimated already, to move even when their positions are threatened by the feet of onrushing students. Not even do they respond to the football player when he extends his hands in a gentle, sincere gesture of friendship.

This problem must soon be solved. We have only to imagine what might happen in the future to feel the urgency of a solution. Every year this particular campus group registers a sharp population increase. It is only a short time until these new members will have adopted the lethargy of their Predecessors. It is conceivable that professors will, in the

near future, be forced to park their cars off-campus and walk to their 8:30 classes to avoid the trouble of chasing the canines from the roads. To bring this problem closer to the professors, it should be pointed out the large number of dogs contributed by the professors to the campus canine population both in the nature of their personal pets and through their personal pets' natures.

It is possible the situation could develop to such an extent that students would have to walk to classes and chapel. To those few who have no cars and who think a dearth of cars would make campus strolls less hazardous, it should be pointed out the dogs must as surely be avoided as the automobiles. It is obvious as much concentration would be necessary to side-step the one as the other.

What would happen to the students' study habits? Picture the sorely belabored student beginning his daily "mid• night to one" joust with his books only to hear from his window added to the usual night sounds the soft snores of some pooch. This addition to the nightly noises might ruin his midnight concentration abilities, and cause him to make an unfavorable adjustment in his college life.

We are overlong in setting up the problem. We should concern ourselves mainly with a practical solution, and first we must seek the cause of this growing dilemma. In my research on the subject, I have pinpointed the trouble spot as the college refectory.

In this building the dogs find their daily bread. The old saw, "One man's poison is another dog's fortune," applies here. Food is in abundance for the hungry canines. No dog can amble through those trash filled aisles without receiving from dog-loving and self-loving students such delicacies as barbecued fat-ribs, cold roast beef, or even super-thin T-bone steaks. The students are also generous with their lumpy• mashed patatoes, their greasy greens, and their chili bean delights; most of which the canines, no doubt to show they too can be generous, leave untouched .

The question comes to mind, "If food is so plentiful why are the dogs emaciated and lazy?" The only logical answer I can give is that the quality of the food is low. This cannot be proven, however, since I have not yet run across a stu·

dent who has eaten enough to pass judgment on its quality, and the dog's conditions are such that they register neither approval nor disapproval of their daily fare.

Several solutions are apparent, but I think most must be discarded on close examination. For one thing, the quality of the food could be improved. This is no solution, however, for then the students would eat the food and the dogs would starve to death. A second possibility would be to turn the dogs over to the city pound. This would mean extra work on the refectory help, though; for leaving full plates at the tables would cause the hired help to have to scrape the food from the plates into leftover containers for storage until the next meal.

One proper solution presents itself: the school administration should require the canine population to carry meal tickets similar to those carried by students. This would meet all the needs I have mentioned and several others I shall mention.

In the first place, this plan would add money to the school treasury and would inform the treasurer on the exact number of dogs on campus. If the number of dogs was at any time less than the number of students, the treasurer could inform the dietitian, and he could cut his food bill, since what the dogs don't eat is wasted anyway. The monetary significance of collecting twice for each meal (from the student who doesn't eat the food and the dog who does) cannot be underestimated.

In the second place, the school administration could "raise the standards" of its canine population. Stray dogs and professor's dogs would be eliminated because they could not buy a meal ticket. Only the dogs of the prosperous suburb-dwellers surrounding the school grounds could afford to pay their way.

Lastly, it would give us a permanent use for the old temporary Air Force barracks. This building is ideal for a dog kennel, and it could once again become a paying proposition: for, of course, a small fee would be charged for this service too.

I believe my proposal has astounding possibilities and should be looked into at once.

The Guill-Complex

By TED NORDENHAUG '60

It had been almost a year, now, since the war had ended, since the shrill, deathly screams of falling bombs had rent the air, since the last angry machine-gun fire had strafed the city ... Yes, the war was over now, but the wounds of Munich still lay open and bare. Where once swank apartments and monumental avenues had stood, proud and stately, there was now only the level, frozen ground as far as the eye could see. One could walk block after block, in what had once been the heart of the city, and never see anything higher than a rubble heap, overgrown with wire grass or the occasional remains of a bomb-shelter.

As I slipped on my overcoat and stepped out onto the sidewalk, I noticed that the streets were covered with a thin coating of ice. The frozen cobblestones groaned and sagged beneath the weight of the morning traffic. A bright spot in the overcast hinted ever so slightly at the sun, but the biting cold of the north wind made it folly to raise one's head even an inch to gaze skyward and see what the day held in store. I buried my hands deep in my pockets and snuggled deeper into the proctective warmth of my fur collar. I found it hard to believe that I was back in Munich, the city which I knew so well, the city which had dreamt of a golden future in the Reich.

It was nine o'clock,-too late for the workers, too early for the housewives to be about-so I had the streets comparatively to myself. I walked for an hour, aimlessly, meeting very few people, occasionally stumbling over a stray cat. Oh, how I hated those cats! They reminded me of her, and . . . the Reich.

Gradually, the crowd began to thicken, and I found myself staring into the stony, expressionless faces of the postwar German people: members of the S.S., still tall and erect

after all they had lived for had crashed around them; members of the youth movement, no longer wearing their brown shirts, yet I knew they were dedicated; they must have been dedicated! But somehow their faces were different.

I continued to walk the streets of the gutted city, searching. It was then that I saw her. Deep, tired lines were etched into her pale face. Vicious furrows seemed to have been plowed into her brow. Her shabby, brown coat, the grotesquely protruding cheek bones, the eyes set deeply in hollow sockets made her look like a living ghost. The Reich would never have permitted this! She brushed past me; she did not speak; in an instant she was gone. It took me some minutes to realize that she was just another HausfrauJ on her way to do the family shopping.

Ach! The Reich!

A young lad-he would have been in the movementpassed by, whistling. But there was little conviction in his song, and it soon ceased; the wind had shoved it down his throat. He looked right through me, paid me no more than a casual glance, and hurried on. He did not remember. They had all forgotten.

Munich! The queen city of the Reich! And now the snow had begun to fall.

I rounded a corner and walked down DachauerstrasseJ past the bulJet-riddled statue of Maximilian, past the gutted beer hall, past the twin towers of the cathedral, which ironically enough still stood, though scarred and worn. · Here, I stumbled over some half-naked, ragged urchins, battling on an old garbage pile. I smiled at them, but they were so engrossed in their brawl that they did not even glance up at me. Disgustedly, I noted the object of their contentions-a filthy crust of black bread. They did not deserve even that! Ungrateful wretches! The Reich would have been different.

It was late when I left the beer hall. Even the beer had been cheap and watery. Tired, and utterly disgusted, I returned to my quarters; night had fallen and the night was cold. I had no heat. I dashed cold water on my face and stood before the mirror how long I do not know. I heard myself mumble: "Ach, Eva, do you like me better without the mustache?" It was embarrassing; everyone knows that the Fuhrer does not talk to himself.

WESTWARDHA! or Hey Jake,the Wagon'sStuck

In the MudAgain

East is east and West is West, And the wrong one I have chose. Let's go back to the good old days When students went their merry ways And never a gripe arose.

Oh, give me back that virgin 7,and, Which since has been profaned, Where honor was still honorable, And tolerance still tolerable, Where vanity was vain.

Where freedom really did exist, Not vaguely as a theory, Where a man could think and act and speak, Without the approval of a Greek; And the frat did not grow weary.

A7,as,I fear that land is gone, Ravaged, burnt, destroyed; Where the individual had a soul, And was ne'er dissuaded from his goal, When pressure was employed.

'Sic semper tyrannis' the Roman said, As he felled the would-be king. But those times are gone, I stand alone, My cries but an echo bring!

Yes, East is east and West is West, And the wrong one I have chose. I can only moan,· "I should have known," For I dared not write in prose!

TheChangingTone

By JACK WELSH '60

Trevis Long, the choir director for Seventh Street Church, sat at his office desk and pondered the problem in his mind. The pencil in his hand did a tap lightly on the glass top, and his horn-rimmed glasses rose periodically whenever his brow knitted.

It was Thursday night, and in twenty minutes the weekly choir rehearsal would begin. Trevis had just twenty minutes before the problem would have to be faced and solved. It had been put off long enough; tonight it would be finished.

The choir members had begun to congregate in the church sanctuary, and the sound of their voices drifted into the office. Trevis thought about his choir; it was a loyal, faithful group. There was Marvin Jessup, bass, and Jane Page, alto-they were to be married next month. There was Mrs. Watkins, alto--she was expecting a baby. Of course one couldn't omit the Clarke family-a tenor, two sopranos, and a fledgling bass. And then there was old John Haynes, a monotone--he was the problem.

There was no place for a monotone in a choir, but how could Trevis tell Mr. Haynes that he was no longer needed. Besides, Haynes was ever faithful and prompt. Trevis could remember only one time that the old man had missed a choir rehearsal or a church service. That was a Thursday two weeks ago . . . what a wonderful rehearsal-no loud, clear, off-beat monotone. Still the absent one had had the foresight to phone Trevis and notify him that a bad attack of lumbago was keeping him at home. Oh, why are the ones you want to get rid of so faithful?

John Haynes was very prompt for all rehearsals. He would come into the church sanctuary and head straight for his seat in the bass section, where he sat by himself, serenely waiting for the rehearsal to begin. Although this small figure was neatly dressed on Sunday mornings, he always attended Thursday's sessions in grimy work clothes that carried a faint musty odor. Trevis often wondered why.

Many of the young altos and sopranos whispered and pointed at old John's Thursday night attire. Of course the girls performed these unkind acts behind his back and wouldn't have dreamed of hurting the old man's feeling. Ye4 somehow Trevis sensed that Haynes, although he knew about the twittering of the youths, didn't care at all.

Even some of the older women of the choir began to complain of the way Haynes dressed for rehearsals. When one or two had actually come to Trevis and asked him to do something about this problem, he searched for a way to open a discussion of these matters with Haynes. Although it was not going to be easy, this talk would have to be very business like, and maybe the director could somehow find an opportunity for finally dismissing old John from the choir.

Trevis got his chance one Thursday night when "the problem" arrived late for rehearsal--come to think of it, this was probably the only time Haynes had ever been late.

When Trevis had begun the rehearsal, he had noticed that "the seat" in the bass section was not occupied. It was going to be pleasantly gratifying to conduct a good practice. But during the third page of Mozart's "Alleluia" the side door on the left of the choir loft opened, and the old gentleman stumbled through the alto section to his accustomed spot on the back row. Trevis noticed that, as Haynes passed Mrs. Watkins, his soiled overalls grazed her crisp white blouse. The woman hastily brushed imaginary dirt from her sleeve and cast a meaningful look in Trevis's direction.

Trevis Long positively resolved that this night was going to be old John's last singing engagement with the Seventh Street Church Choir, and after the closing prayer the director started to beckon to the late arrival that he would like to speak with him. But Trevis noticed that the old man was already making his way to the director's stand.

His clothes were certainly filthy, but his face and hands glowed with a ruddy cleanliness. His hair was snow-whiteneatly combed. As Trevis breathed deeply and started to ask Haynes to step into the office, the approaching figure began . humbly apologizing for his late arrival.

"I'm awfully sorry I was late a-getting here tonight, Mr. Long. I know you like all us members to be prompt, but something unexpected upped." He wheezed and continued.

"You know, I go by Widow Bradley's every night to fix her furnace, and tonight the thing'd gone out -so I had to fix'er."

So that explained the damp and dirty work clothes. Trevis looked at the old blue eyes as they waited for a reply. "Oh, think nothing of it," Trevis heard himself answer. "Everybody is delayed sometime or the other. See you Sunday."

Trevis gathered up his music and quickly walked to his office. After everyone had left, he too went home. To think that old Haynes had taken that job-and probably no one else knew about it. Well, you couldn't dismiss a person from the choir because he was late one time.

Later Trevis could have kicked himself. Being choir director was his job. He should have done what was best for the choir, and getting rid of a monotone was certainly the natural and correct thing to do.

As the director now sat tonight in his office, he thought of the many times he had almost told Haynes not to sing with the choir. How was he going to do it now? He had started to tell him last Sunday morning but . . . Trevis ruefully had to admit that he was thankful to the old codger that time.

The anthem for last Sunday was a beautiful one. After a tenor solo, the choir provided a soft, rhythmical background as the tenor soloist again sang the haunting melody. The music had started, and Trevis remembered he had scowled at Haynes when the old man began to tap his foot in accompaniment. This was another gruesome habit that old John sometimes delved in, but those blue eyes must have understood the director's silent message for the noise quickly ceased. Trevis resolved to speak with John after the service.

Then Wayne Mallory started his solo. Trevis gulped; it was a half measure too soon. He attempted to subtly signal the concentrating singer-then the organist. No good.

Trevis was frantic. When the choir came in, it was going to be chaos. And suddenly old John started tapping his foot again.

"Oh, my God," Trevis prayed. This was too much to stand. All three of them were carrying on at three different tempos. At least John's tapping was with the director's beat -miracle to behold!

The organist glanced up, frowned, and skipped half a measure. Trevis prayed, "One more to go."

But Wayne Mallory sang blissfully on-then he paused, sang one note twice, and finally began to stay with the beat In two measures, the choir entered correctly, and the rest of the anthem sounded as it should-except for a certain clear monotone.

Trevis Long would always remember that sickening feeling which gripped him after the choir had finished. The sweat had poured down his back. He could recall even now the intense gratitude in his heart toward John Haynes.

Why did the old man always have to come through at the wrong moments? Oh, Trevis could cite numerous occasions when he had been ready to get rid of Haynes, and then something had happened to stop this action.

The chair in the office squeaked as the choir director turned to glance at the clock. Eight o'clock. It was time for the rehearsal to start, and Trevis didn't have the answer to his problem. He quickly gathered up his music.

"Oh, Lord, help me to say the right thing. I don't want to hurt the old guy's feelings, but he just doesn't belong in the choir. He can't keep on singing. Please let me do it right."

Trevis tucked the music under his arm and walked to the door. He flicked out the light, pausing a second before he stretched out his hand for the knob.

"Br-r-ring ... Br-r-ring ... " The office phone on the desk shattered the stillness of the dark office. Trevis started; then he flicked on the light and returned to answer the phone. "Yes?"

"May I talk with a Mr. Long, please?"

"Speaking," Trevis answered.

"Ah-Mr. Long, this is Dr. Martin at the Central Clinic. I'm sorry to bother you, but the body of an elderly gentleman was brought in here a few hours ago. He was killed by a hitand-run driver on the corner of Elwood and Stafford Avenues."

Trevis Long automatically thought of a little old man in dirty overalls. "Yes?"

"His only marks of identification were two scraps of (Continued on Page 32)

Come With Me or What Else Could You Want?

Come with me where telephones are made without the bell, Where palm trees always shade your head, and time can never tell, Where sunlight never is too bright, And clouds are never gray, Where you can set and chew and spit, And "raise hell" every day.

Oh, come with me where tax forms never meet the press, Where integration deals with ducks and Dodos none the less, Where Michael Todd is 'neath the sod And Faubus close behind, Where Baptist preachers finally teach us What is peace of mind.

Come with me where the cold war is just a snow ball fight, Where 8'[J'Utnik is a carousal that runs both day and night, Where Arabs rather sell their scarabs Fashioned by the hand, Then spend their life in vengeful strife For a few square feet of sand.

Oh, come with me where Broadway is one long wide, wide road, Where Hollywood is used for fire and Labor's just a load, Where politics and Russia's tricks And gastric ulcers too Are ancient terms one never learns, Becausethe needs are few.

Come with me where Christmas lasts the whole year 'round, Where autos fly in squadrons and never touch the ground, Where socialities are used at night

To illuminate the dark, Where hot dog stands and rubber bands Have never made their mark.

Come with me and leave behind your Elvis Presley hits. Hang your guitar on the wall, forget your bO'J)'J)ingfits.

I'll free your soul from "rock and roll," And lead you to the land

Where you'll trade your suedes and "custom mades" For bare feet in the sand.

Come with me where billboards and Bilbo are "cuss'' words, Where we'll forget "Suburbia's'' never ending teeming herds, Where we can flee the mad TV!

L. Welk, detergents, fights. With nature's scene "toujour" serene, We'll find our lost eyesight.

Come with me where atoms remain where they belong, Where everyone has hailed that "Stardust'' be the national song, Where you'll for get the constant threat Of colds and Asian flu, Where General Ike and F. Lloyd Wright Are peryplejust like you.

Come with me where "Oonvo" is disliked by just a few, Where you can grow a long black beard and sleep the whole day through, Where green MG's grow on all trees And Profs are good old Joes, Where Deans insist class be dismissed In winter when it snows.

Come take your outs and we will fly where class bells never ring, Where life consists of just one endless round of 'P(1,rtying. The reams of those fantastic dreams You sometimes wish could be, Will all come true if only you Will come and be with me.

REFLECTIONS

By A Psychology Major

We're all just a bunch of neurotics Who look on stability with scorn. With behavior resembling psychotics We think maladjustment's the norm.

We rush to our anylists, Provide research for panalists, Render justice unreliable, Misconceiving, unpliable, Leave our children a heritage, Of diversified miscarriages, And in general seem hazy As to who's sane or crazy.

Oh ... we're all just a bunch of neurotics, With a concept of Zife far from true. And we'll wind up case histories for medics, If we choose to remain deaf to this view.

CAROL E. MINOR '58

CAROL E. MINOR '58

Law and Order

JOHN E. DONALDSON '60

Since the days of Reconstruction the most pressing problem with which the South has had to cope has been that of racial relations. In attempting to resolve this problem, the South over a period of years developed a social order compatible with the principle of "separate but equal" set forth in a decision of the Supreme Court in 1896. Over a period of fifty-eight years this social order was upheld by Federal courts, but on May 17, 1954, that august group of politicians and professors composing the Supreme Court ruled that all prevoius decisions upholding segregation in public schools were in error and that segregation of Negroes on the sole basis of race was a denial to them of the equal protection of the laws. Subsequent decisions have completely repudiated segregation on the basis of race in all public facilities.

I do not propose to discuss the legality of these decisions, the competence of the Supreme Court, the moral issues involved in the rulings, or the social merits of integration and segregation. I have strong feelings on each of these questions, but I am primarily concerned with the problems of law and order arising from recent decisions of Federal Courts relative to segregation in public schools. The question of how President Eisenhower and the Federal courts intend to bring about integration is foremost in my mind. Are they willing to wait until conditions are such that integration can be accomplished with a minimum of ill-will, disorder, and violence, or are they determined to compell racial mingling in the public schools of the South even if it can be accomplished only by the use of armed force and at the risk of a possible abandoning of the school systems in certain areas? Will these officials be governed by the best interests of the communities in question, or will they instead be governed by political expediency or a desire to reform the South no matter what the costs? If these officials continue on their present course, the answers

to these questions can be deduced from the rulings of Federal Judge Ronald Davies and the actions of President Eisenhower relative to developments at Little Rock, Arkansas last September.

The town of Little Rock had made preparations to begin limited integration at the opening of the school session on September 2. As this date approached, tension began to mount as a result of the circulation of inflammatory literature and the influence of extremists. By the middle of August The Afro-American, a Negro newspaper, was predicting an outbreak of violence when the schools opened. As a result of these developments a county court issued an injunction temporarily restraining the school board from beginning integration. This injunction was set aside by Judge Davies on August 30. Fearing an outbreak of violence, Governor Orval Faubus sent the National Guard to Little Rock on September 2 to prevent integration. During the three weeks that followed peace and segregation prevailed. However, on September 20, in obedience to a summons, Faubus appeared in court before Judge Davies and was ordered to remove the National Guard. He reluctantly obeyed and on September 23, nine Negro pupils entered Central High School. The violence Faubus had sought to prevent became a reality with fighting and rioting in the streets and disorder in the school building. In an effort to restore order forty-one arrests were made by city and state police. The next day the town was partially occupied by paratroopers of the U. S. Army's 101st Airbourne Division. Integration was then enforced by the might of armed force.

The implications to be drawn from these developments provide a just cause for alarm. If the Federal authorities continue on this course there can only be disaster and social regression. The course taken by these officials was one in which no concern was given to local conditions. Let us hope that this course is not continued. A court order in itself cannot remove prejudice and fear from a man's mind, or instill in him love where hatred already exists. It is argued by integrationists that segregation is an evil to society in that it denies rights to certain groups. This may be true, but if in removing this defect other evils are created, nothing good for society will have been accomplished.

In large areas of the South immediate integration would be accompanied by violence and increased racial animosities. Immediate integration can only mean social regression in these areas. Resistance would be such that if integration were enforced at all, it could only be done by the force of Federal troops. Certainly we do not want to risk having more Little Rocks. Florida, realizing that little education can take place in the presence of bayonets, has arranged to close any school district that is occupied by Federal troops whose intent it is to enforce integration. Florida is said to be the most moderate Southern state on the integration issue, incidentally.

In other areas of the deep South and in Virginia, there will be no Federal troops and no violence if integration of the public schools is ordered. There will be no troops or violence because there will be no public schools. There is no provision in the Constitution that can enable a Federal court to require a state to maintain a school system. If an order to integrate is tantamount to closing the schools, then such an order should not be made. If the courts would only be patient enough to wait until local conditions are such that integration can be accomplished without disrupting society, then integration could be had with no loss of public education. If, on the other hand, the courts were to give no concern to these conditions, the harm done to our social order may be irreparable .

In this essay I am not defending the prejudices of the Southern White. I am not condoning his willingness to resort to violence, to disobey the laws, or to close the public schools in order to preserve segregation. I am only asking that the Federal authorities involved in this controversy recognize the reality of the determination of certain communities to avoid integration at all costs. I am not asking that they not enforce integration in areas where it can be accomplished in an orderly manner. I ask only that they wait until local conditions are such that the communities in question can integrate with a minimum of ill-will, violence, and social disorder. If the courts are willing to use as their guide the best interests of the community in formulating their decrees, we can solve the integration problem in an orderly and effective manner. Shall we progress, or shall we regress? It's up to the courts.

From The SelectedWritings Of Hubert

Deer girl,

Hello! How are you? Fine I hope. Good. So am I. That is good, two. I am a freshman in kollege. So are you in kollege, i meen. Uhh! I like you. Very much. You don't like me, do you? As I like you and you don't like me I am sad.

I am going to join a frat. Then maybe you'll like me because I will be a Grecian. I am saving my money. I am going to buy a suet. IVY LEAGUE! I have already saved 67c. Soon I will have enouf. Are your coarses hard? Mine are. My prof in Inglish 101 is very hard.

I am a nice boy. You are a nice girl. Too! I like you. You do not me. I'm sory. Because I am a fresh man, that's why. Next yeer I will be a sarfmore. Then, you'll see. You may think this is pupy love. It ain't. I am a kollege man! Ha! You'll see . I am not adolesent no more. MATUR! As you can see I am emotionable. I am rought with emotion. Matur emotion!

This is a love leter. I hope you like love leters. But this is a matur love leter. I am a matur man! Do you like matur men? I hope you do. Next yeer I will be in my second yeer and even more matur. I want to ask you a personel question. Uhh! Shuks! I forgot.

luv,

Hubert

Editor's note: Printed with the permission of a Westhampton lady. We also wish to offer our humble apologies to the Faculty Committee on the Students' Use of English.

Peyton Place

Peyton Place. By Grace Metalious. New York: Dell Publishing Oo., Inc. $.50.

Every day people are provided with opportunities to indicate their thought and that which they seek from life. The presence of Peyton Place in Convocations, the meal lines, and at Evening Watch shows that, aside from being a series of sordid character sketches cemented with a common locale, it is just such an opportunity.

Exposing a particular talent for lurid scences which proclaims her a candidate for the title of mistress of non-intellectual turgescence, the author proceeds to display for the morbidly curious the sinfullness of the people from Chestnut Street to the Cross shack; for the open minded are currents and lllldercurrents of emotions; and for the book lover she presents a one-sided facsimilie of a book showing the good and bad of life. Grace Metalious has combined life in the privacystript raw with suficient profanity to attract quite a bit of attention. But is this attention justified?

Peyton Place is a town, named for a "nigger," and is just like any Lincolnville or Trumantown with one exception: Peyton Place has no good. Without a doubt this point is made: the venerable doctor is a drunken abortionist; the most important minister is a spineless turncoat ... and so into the night which covers further incidents of rape, racket, and rut. After this goal is achieved, a moral follows stating that Peyton Place is just as any other town, neither good nor bad. I question the basis for the moral, as well as its truth.

By and large, however, Peyton Place provides an illustration for that adage, "Seek and ye shall find." Seek sin, find sin: seek a saga, find one: seek quality, and find it, maybe.

So then, to sum up the achievement of Peyton Place as a book, there isn't any such thing as a good small town. If this be true, then Williams has anticipated my feeling in the following lines from his poem, Towns Become Jewels: 22

".

. . Oh why are they not as once we believed they were incorruptible gems true diamonds dropped in water?"*

-J. S. PRESGRAVES

*Tennessee Williams, In the Winter of Cities, (New York, 1957), p. 110.

The Night I Became A Statistic

By TOMMY ATKINS '60

The refreshing coolness of the night air gradually dissipated before a new force. The air grew thick with a pungent odor. A dry, acrid taste crept up my tongue. First watery beads and then trickling streams of sweat broke out upon my body. My nostrils began to strain to bring into my lungs a sufficient quantity of oxygen. A restless feeling set in and I presently found myself wide awake. I heard a slight crackling noise in the distance and saw crimson rays of light streaming under my door. Within seconds, billows of thick gray smoke were pouring under my door. These billows of smoke were the last objects I was to see clearly, as my eyes began smarting and watering to the point of virtual blindness. The crackling noise grew louder, while dull thuds echoed from the front rooms. The acrid smoke expelling almost all of the dwindling oxygen supply from my room, a wild hysteria gripped me and I rushed to the door. As my sweating hand gripped the hot doorknob, my skin stuck to it, and the stiffling heat badly seared my arm. The floor gradually sild out from under me and I crashed helplessly into the anxious arms of the inferno below. When my charred form ·struck the blazing linoleum floor, I stuck to it and I was unable to rise. My limbs became numb with heat. A great number of flames hungrily licked my face and body, and I felt my flesh slowly slide from my baked bones. A new odor-that of blazing flesh-was mixed with the pungent air. My head began to swim with the heat waves. A half-hour later a few charred bones were the only proof that I had existed. I had become the first victim of the Ku Klux Klan!

Xnanias

A ballad in Old Piedmont Negro dialect

Poets seems to take a lilcin'

To de boys what does de spikin', Grades de road, an' taps de rail,

An' drinks up shine an' gits in jail.

Ah agrees dat dey's aw right.

Dey kin work, an' dey kin fight.

But dey's hoggin' all de glory; Bo Ah's got a diff'unt story.

Ah's gwinna tell yoo ob a great Virginian what once loaded freight.

Now Petersburg, when Kirk was boss, Is when an' whar Ah come across

A fella wif steel piston bones

By de name ob Nias Jones.

He stood a eben seben-two,

An' he cou'nt wear no sto' -booght shoe. He cou'nt weigh on regular scales, But use de one f o' cotton bales.

His skin was soot, his whiskers cinders. His eyes glowed red like lamps on tenders.

His teef was big an' straight an' white

An' showed like moonbeams in de night.

His arms was like two junkin' cranes

Wif five-pronged scoops all '[)Uffwif veins.

De Seaboa'd Railroad, I don't figger

Neber hire no bigger nigger.

To see him walk you'd think he's creepin', But Ah'd be truckin' jest akeepin'

Up wif dat big lumbrin' hide.

He'd cross de track wif one good stride. 24

When he'd walk to work fru tenon, People'd stop an' turn aroun'

An' gasp at dat tremenjus back,

An' think some train done jump de track.

An' "Dixie'' was de warnin' blowed (Uh, dat's de only song he knowed.)

When dat engine hit a crossin'.

An' none dem cars wou'nt try no bossin'.

But, wif all dat fella had,

He'd neber fight or git real mad.

Why, once he gabe a dog a pat,

An' cried acause he knock it fiat.

He lub his Lord an' un'erstood

His strengf was meant to work fo' good.

He'd neber gripe or loaf or run

Away fum work out in de son.

De sweat roll down like rain on tar

When he'd top hogs-heads in a car.

By hisself he'd Zif' up bales,

An' switch-base ties, an' standard rails.

His partner, B7,an,done most de thinkin'.

N ias was de boss ob stinkin'.

His hat could hol' a country peck,

But he cou'nt sign his own pay check.

Dey's a team, da.t Nias an' Blan, Blan de brains an' Nias de man.

One day a truck brought fifteen men, What sat a free-ton cotton gin

On de creakin' warehouse flo'.

Dey jest could git it fru de do'.

De boss-man look an' near 'bout 'sploded.

"We'll neber git dat blamed thing loaded! It's fifty feet fum car to gin.

Ah'll hao t' hire a dozen men."

Blan got mad wif Debil-heat.

Nias 7,aughan' scratch his seat.

Blan say, "You leab dis to us.

We's gwinna git it done or bus'!"

De boss-man lef' at half pas' one.

At two he brought back ten more men, 25

But, "Glory be!" Dere warn't no gin.

"How you git dat in a car?"

"On a roller wif a bar,"

Say Blan, "Ah tol' Nias how to do it,

An' he 'bout pick it up an' fru it."

Nias done his work by day, But when night come he like to play.

He got no special wife or h<Yme, But he know jest what streets to roam.

Somebody yell, "Nias is comin'!"

Den how dem bees would start t' hummin'.

De chullen skated 'tween his feet .

De women, quick-like, got real neat.

Dey'd try all de latest charms

To git all crushed up in his arms.

De gals would beg, an' sometime fight

Jest to git him fo' de night.

She'd be de proudest in her race,

Till N ias went some odder place.

He'd pick a gal what done good cookin'.

He din't cear if she's good lookin'.

An', Lordy, once he got t' sittin'

Wif de food dere warn't no quittin'

'Stead ob a bib he'd wear a towel.

'Stead ob a fork he'd use a trowel.

He'd chomp an' chuck whole cakes an' chicken8

Like dey's little party pickin's.

But Nias warn't de kind fo' takin',

An' keepin' all dat he was makin'.

On Christmas Ebe his whole week's pay

Was spent on stuff to gib away.

He'd leab a basket on de do'

Ob anyone he thought was po'.

Wif one bare fis' he'd bash de en'

Out ob a keg f o' all de men.

Den when de chillun gather roun'

He'd fro' money on de groun'.

He'd squeeze de gals mo' dan enough

An' gib dem kinds ob un'erstuff.

Den come de war, an' army 'quippin'

Take a heap ob railroad shippin'.

Nias was too ol' to fight,

But he'd work till late at night.

He done all dat he could do

To hep Camp Lee's supplies run fru.

But dem days was pow'ful tough,

An' eben Nias warn't enough.

Spider webs gabe way to freight.

De warehouse sag wif all de weight.

So de camp trucks an' men

To help po' Blan an' Nias begin

To git things packed an' "hauledaway.

Den it happen. Cuss de day!

On de platform, 'bove de track

Sat a wobbly, rusty stack

Ob freight car wheels, fo' scrap,

Dere axles tied wif one steel strap

A truck back up, gabe dem a bump.

De strap bus' loose. Dey 'gan t' hump.

Like banshees wakin' out de groun'

Wheels screeched an' groaned, den tumble down!

Dem flanges was so old an' rough

Dey groun' de two-by-fa's to snuff.

Hab a ton apiece dey weighed,

An' balled like freights down mountain grade!

De men was standin' on de groun'

Aside de track, but all jerked roun'

When dey heard dat awful rumblin',

Dem soldiers jumpedr-all but one.

He'd step in de switch an' cou'nt run.

All dat steel was gwinna fall

On him fum off a six foot wall.

Re screemed! He try to twis', to pull!

Den Nias charge in like a bull!

He pushed de white boy on his face

An' stood like Sam'son 'gainst dat race

Ob fallin' pillars, 'bove his brother.

Den one bashed him! Den another!

Still he stoode dere like a boulder,

Blockin' tons ob steel wif his shoul,der! He stood dere straight, in blood an' pain, Till he'd derail de Debil's train! His pistons limp, his boiler crushed, He chugged up blood. Den, slow an' hushed, "It's ober son,-lt's safe," he said. Den fell like a oak. Nias was dead. Dat's his story. Ah swear it's true!

An' one mo' thing befo' Ah'm fru. If de 'mount de women cried An' mount ob flowers by his side Is what decide de place fo' his soul, His warehouse is Heben. His frieight is all gol'!

TO WOMAN

Spider, hidden by the sun

On webs of burning beauty spun, To your snaring orbit run Blinded fools to feast upon. (Blinded fools, and I am one.)

PAULW. KIRK,JR.

PAULW. KIRK,JR.

Campus Personalities

By JOHN WILLIS '60

Almost every student at some time in his college career undergoes a period of self-analysis during which his personality changes drastically. In one extreme, he will resemble T. S. Eliot, the dean of intellectuals and sophisticates, who unlike so many of his disciples, actually is a genuine scholar. In the other extreme, he will lean to the freshness of Jerry Lewis, a perennial college favorite for the campus-wit. The tragic tendency is to compromise these two positive personalities and become just a "good guy," a hale-fellow-well-met.

There is no great harm in trying to modify your personality, or in trying to pattern after the admired characteristics of an acclaimed personality, but the truth of the matter is that most students are more interesting naturally than the character molds they choose for themselves. I'm sure you've had the pleasant experience of getting to know someone intimately after having known them casually for some time, to find that their "real" personality is much more appealing than the one they display to people outside the inner circle. Unfortunately for most of us, the old saying that "first impressions are lasting impressions" is pretty generally true. Many freshmen are intimidated by the rigors of ratting, only to find that students and faculty have pegged them and classified them by their behavior those first few sleepless days. Others come equipped with a special "man of the world" attitude, hoping (in vain) to ward off some of the ratting activities by seeming tougher-than-thou. They too are dismayed to find that they have been classified as bullies, poor sports, churls, tough guys, and such. It takes quite a bit of doing to convince the campus that you aren't still acting out of character when you do begin being yourself again.

There are many pressures brought to bear on us not to be natural, not to be ourselves. Outside of the commercial pressures w h i c h try to convince us to be Marlboro Men, Ivy Leaguers, Schlitzers, etc., there are other pressures to don the mask. Students coming to these happy hallowed halls soon become aware that there is definitely life beyond the misty shores of Westhampton Lake, and accordingly become tigers or teddy.,.bears, hoping to win the favor of a faerie queene. Co-eds too must learn to deftly swing their silken locks in just the right angle to their painted eyebrows, or develop a fetching grasp on the Bunsen Burner in the lab, (a burning situation). The truth still is that while men and women both are pressured into these false personalities, both sexes choose their mates from those who are attractive naturally. "Inner qualities"' are usually terms ref erring to blind dates whose appearance is no better than their vision; but in seeking personalities for lasting friendships and/or marriage, they are the important questions.

The qualities of scholarship are essential for poets and professors, but most students shun being called dean's list students or "brains." Most students seem to feel that straight-A students are lacking in some of the more fundamental drives. Science has not yet proved any correlation between bust and brain. The object, then, is to be a well-rounded guy to our classmates; to the draft board and faculty an indispensable appointee to the Institute for Advanced Research; and to our girls, worldly, suave boulavardiers--except when the occasion calls for a little-boy-lost. This in itself would require all of our energies, but we are even further pressured into restyling ourselves.

When a student is motivated to run for campus office, he must take on certain other aspects. He must be chocked full of school spirit, matched only by his disgust with the school administration. He must stand for all high and lofty callings compatible with the dictates of his conscience and fraternity. He must have a dynamic personality, that will bring out the vote; a positive personality that will not be swayed by students with an axe to grind, or officials with a student to grind; that will put across all of its purposes without offending either the students or the administration; a personality that will stay

within the realms of those things that belong to the students, without becoming a figurehead for somebody's machine. Man is a political animal, and the campus politician is a marvelous animal, a dazzling blend of personality perfection.

Person is the root of personality. Each of us is different in every way that people can be different: psychologically, physiologically, biologically, mentally, constitutionally, and all the rest. Our pasts were different, our futures will be different. If we pretend to be what we are not, someone else, the results will be tragic or comic. Personalities are the results of needs, backgrounds, circumstances, and experience. Personality is not a plastic substance, a face that we can put on according to our moods. What a pleasure to smoke a cigarette that doesn't filter the flavor, that let's you get a natural smoke; what a pleasure it is to meet someone who respects you enough to be sincere.

Sine and cere are two Latin words which form our Eng~ lish word; they mean "without wax." Back in the old days of the Roman Empire, merchants would sell pots and vases of ceramics that would sometimes come to pieces when put to use. They were attractive, but when put to a practical purpose, they fell apart. Some merchants were unreliable; but others would place on their wares the sign "Without Wax." Their works were without blemish and cracks, they were not reinforced or held together with wax and putty. They were genuine, sincere. We need to hang such signs on our personalities, if we can, so that all men will see the fruits; that they can vote for us in confidence; confide in us safely their problems; that they can know they will not be deceived or let down; that we won't fall apart when taken to task.

Polonius said to Laertes: "This above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow as the night the day, thou cans't not then be false to any man." Too many students aren't true to themselves, pretending that they can handle more than they can take care of well; and then they either fail completely or back out altogether. They argue whether reason is with them or not, and they allow themselves to be caught in compromising situations for which they have to repair bad reputations, and nurse wounded pride. Be yourself. If you are always natural, even if it may seem pretty plain to you, things will fall into place; but if you are constantly changing per-

sonalities, you won't be stable, always having to adjust and making other adjust to you.

Some students take to heart the old saw "all the world's a stage, and every man a player." But they fail to grasp the oldest truth of acting: the hardest part to play is to be yourself. An average actor can work hard on a script and command the stage; it takes the very best to be himself and still command the stage. Some think they must color their speech with witty little gems, or masculine curse words. (Why do men think it masculine to curse when many women can put them to shame?) One can only repeat that those who are always naturally themselves command the stage which is this world. Fraternities, machines, and "pull" will keep us out in front to a point, but in the really important questions, men will always look to the individual, the man who thinks and acts himself, for leadership.

THE CHANGING TONE

(Continued from Page 14)

paper, and one of these mentioned your name. Would you like for me to read them to you?"

Trevis licked his lips. A half audible "If you don't mind" slipped through.

"No sir. Ah-the first one is a memo. It reads: Phone Mr. Long, 7-4920, and tell him that I won't be there for rehearsal. Lumbago is bothering." And the other is a poem."

"A poem?"

"Yes sir. It says: 'Although I know my tone is harsh ... And my chords are cracked and old ... I hope I'll get to trade them in . . . When I walk the streets of gold . . . For I don't sound the best you know ... My voice has flown away ... May I get a silver harp or such ... When I reach those shores someday.' "

There was a long pause. Trevis took a deep breath and closed his eyes.

"Thank you" was all he could say. And slowly he placed the receiver back on the hook.

Eight-ten. He was late. Trevis turned and walked quietly into the sanctuary.

Please Omit Flowers

By JEANNE KOSKO '58

John Holcraft was a quiet, peace-loving man, who lived with his hired man, Harve, in a small house near town. He was much like any middle-aged, retired bachelor, except for one thing. He was a fanatic about funerals. Even if he didn't know the person, he would go, just to hear the crying of the mourners and the sad words of the minister.

Harve would bring the paper and John would soon be busy planning his day's schedule.

"Ah, yes, there are quite a few today. I see now that this is going to be another good way. It says here that Mrs. McIntyre fell and broke her neck; her funeral will be at 0akey's. And old man Johnson killed his wife; she will be buried at Evergreen. Oh, here's another. A Mr. Hill was killed in an auto accident; his funeral is at Lotz. Well, that makes three. I'll have a full schedule today, so don't expect me until late, Harve." With that, John would put on his black suit very carefully, place a white carnation in his lapel. and set out for the day.

Now, this thing had been going on for years. Harve, who by now was used to his boss's queer ways, sometimes went with him. But more often John went alone, to sit and weep over the wonderful fates of these people, so fortunate to die-to be mourned for.

"Oh why," he would think to himself, "why couldn't these people be shedding their tears for me instead of wasting them on such a person as this? Worst of all, he doesn't even know what's going on and that they're crying for him!

At home, later in the day, John would relate his day's activities to Harve, who listened with interest.

"Harve, you should have gone with me today and seen the funeral they gave old Mrs. McIntyre. I haven't seen one

so beautiful in a long time. The chapel was filled with weeping and beautiful words of the preacher. But there the old lady lay, dead as a doornail, not knowing a thing about it It's a shame to waste so much grief and attention on a person who can't enjoy it. Well, I guess I'll go to bed now. Goodnight, Harve. Call me early. I have another busy day tomorrow."

John went off to bed, to dream of his day's experiences. But, tonight he couldn't go to sleep. Through his mind ran all kinds of thoughts. Suddenly he sat up and called out wildly.

"Harve, Harve, come quick! I've got it. It's the answer to all my prayers. It's so simple, why didn't I think of it before?"

By this time, Harve was in the room, wide-eyed with wonder.

"What's the matter, boss? What's the matter with you? What you got?"

"I'm going to have a funeral, Harve. All to myself, and everybody's going to cry just for me. It's going to be wonderful."

"But boss," interrupted Harve, "How you going to have a funeral when you ain't even dead yet? All the funerals I'se been to, the folk's been dead."

"That's where you come in Harve. I'm not going to die. I'm just going to borrow somebody's casket for awhile. Now here's my plan. The paper said that G. S. Smith died and his funeral is tomorrow. Now, there probably won't be anybody at the funeral parlor this late, so I'm going down and get Mr. Smith's body out and hide it. Then I'll get in his casket and lock it after me, so they won't know who's in it. Then they'll bury me and you'll come and dig me up. Isn't that simple? You will do it, won't you, Harve ?"

"No, suh, boss. You ain't catchin' me digging you up. I stood your going off to the funerals every day, but you ain't gittin' me to do this, no siree! We been friends a long time, but if you ask me to do this, we're through for good."

"But, Harve, if you will just do this for me I'll never go to another funeral. I have waited for this thing for years. You know that. Now you wouldn't spoil my life's ambition ,

would you? I'll really die, if you won't do it. Please, Harve, Please. Don't let me down now."

"Well, all right, boss. But you'll have to promise me that you'll cut out your crazy ways and stay home every day. If you will, then I'll do it for you."

"Thanks a lot, Harve. I promise you right now that I'll never go to another funeral."

John excitedly dressed in his best black suit, put his flower in his coat and hurried off to the funeral parlor. When he reached his destination, he went in silently, and sighed thankfully at seeing no one. He slipped into the chapel and went right to work. It took a long time to get the body out of the casket and down the steps to the basement, as Smith was a big man and John was quite small. But he completed this task after awhile and hid the body under some boxes in the corner. Then John took on a reverent attitude as he ascended the stairs and solemnly climbed into his bed for the night, being careful to close the top after him.

He settled down to his night's rest in his strange bed. At last he was content. He had longed for a funeral practically all his life. And best of all, he would be able to hear what was going on.

"That's what I want most of all," John thought.

"To hear the people crying and hear the sad funeral sermon. Of course, it won't be about me and the people won't be crying for me, but I'll still be in the coffin, and it'll seem like they're mourning for me."

With this thought in mind, John went tQ sleep. Someone knocked against the coffin. John awoke with a start and bumped his head when he tried to sit up. Then he remembered where he was. Today was his funeral.

"It must be about time," he thought. "I can hear the people moving, and-what's that? Tears? They're crying for me? Oh, this is heaven, I just know it. That must be the minister clearing his throat. Yes, the people are quieting down, it must be about time for my funeral."

Then he lay there, absorbing all the sounds of his funeral-the soft crying of the people and the beautiful words of his funeral sermon. His pillow was slowly becoming wet with his tears.

"There must be a hundred people here. Just listen to them cry. Mr. Smith must have been well-known to deserve all those tears. I wonder where I'll be buried. I hope it's at Evergreen. Oh, my gosh. I forgot to tell Harve where I'll be buried. How will he know where to dig me up?

But John's thoughts were interrupted by the words of the preacher.

"I now commit the final remains of George Samuel Smith to God and Eternity. Due to the last wish of Mr. Smith, the body will be cremated."

There was a scream, but it went unheeded. The congregation thought it was a mourner overcome with grief. Then the coffin of G. S. Smith was slowly lowered into the crackling flames of the furnace.

FOR THINKING OF THE SKY I COULD NOT SLEEP

I saw this morning morning's missile, kingdom of daylight's dolphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Rocket, in his racing

O'er the curving level underneath him azure space, and shooting

High there, how he swung behind the moon in a golden ring In his swiftness! Then off, off forth in haste

As a jet engine cuts smooth through a cloud bank; the speed and brightness

Bewildered me so-my heart in hiding

Feared for the world-the power, the meaning of things.

Cold science, warheads, bombers, oh, air, pride, hatred, now Harken! for the echoes that spring from thee now, a million Times more deadly, more perilous, 0 my fellow man! It is no lie! Each age must run its course in time And, so must yours, world-citizens. Please not in strife, I cannot bear to die.

JEHANE

Voice 01 l'he Deep

By DAVID A. McCANTS '58

"Come on back, Dad. We won't throw water on you," shouted the three boys laughingly.

"Not me. I'm getting away. Three against one isn't fair!" They called him "chicken"-even the youngest, little Ronnie, who was not yet four,-imitating his older brothers. But their father was well out of their range now and almost skipping along the beach, although slightly wet after the water battle with his sons. He liked playing with his three boys in such a manner, though, even if he was the one to get wet. What would he do without Marie had he not the boys to keep him company?

Henry Rose walked along the beach enjoying the warm sunshine and gentle breeze. It was nice here, but not like it used to be with Marie. The boys missed her, too. He could tell. They didn't speak of their mother often, though. Sometimes Frank, the oldest and eight, would say: "You know, like Mommy did." Mommy! He still called her that. Many small children call their mothers that in their first years, and he was only five when she went away. Yes, that was what he had told Frank and Donnie-their mother had gone away. And they had believed him so easily. There were only a few questions until so many people, relatives and friends, appeared at the house, and then Donnie cried, which set Frank to wondering and soon to crying. He had even tried to explain to Frank about it being God's will, and that God had something else for his mother to do. But Frank wanted his mother with him. Had it really been three years? It seemed much longer when he remembered his loneliness. It seemed shorter when he remembered the day. Oh, that day! He was away that day. Would she be here with me today if I hadn't gone into town that afternoon, he asked himself. If he could have a second With his wife for each time he had asked himself that question, they could have relived their lives together. Often, as just now, he could be laughing at one minute

and suddenly so lonely for her that he imagined her presence with him, and the two of them, together, reliving in his heart and imagination moments of happiness 'and tenderness. He stopped walking and looked at the scene about him. He saw her crying for help, calling his name, and he was not there to answer. When he had returned, the storm was over. A party had already gone out to recover her body.

Why did he return here every year? It certainly wasn't the same as it had been with Marie. The boys liked it here, that is, with the exception of Frank. He, like his father, now knew what it was to fear a storm at sea. Mr. Rose couldn't help noticing how Frank very carefully watched over his brothers as they played on the beach. Yes, the boys liked it, but he didn't, for how could he appreciate the place she loved so well when she was no longer there. This place held too many memories. He wondered. Was it a memory of that day and his loss which brought him back each year? "Marie," he said. "I ... ," and he threw himself onto the beach.

When he roused, he noticed that it was becoming darker. Believing that the sun had only disappeared behind a cloud for a moment, he remained there in the sand, having raised himself to a sitting position. Soon, realizing that it was becoming even darker and looking out into the ocean, he saw the rain coming towards him. It was a storm. A nor'easter! Immediately he jumped to his feet and ran as fast as he could to the cottage. Nearing the cottage, he called out to his maid.

"Sarah! Sarah! Where are the boys?" he called excitedly. Sarah appeared at the door. "They're down by the water. What's wrong?"

"A storm is coming up. It looks bad." He appeared worried. He was nervous and continuously looked at the black clouds moving across the heavens.

Sarah peered out of the door and looked up at the sky. "Yes, it does look bad," she said and went scurrying into the cottage to lower the windows.

Mr. Rose did not hear Sarah for he was nearly to the ocean's edge. He could feel his fear of storms mounting within him.

Upon reaching the water, he saw nothing of his boys. 38

He called out, but no one answered. He ran up and down the beach but could not find them. Running back towards the cottage, he met Mr. Daniels, walking towards him.

"Mr. Daniels!" he shouted. "Have you seen anything of my boys?"

"Why yes. They were out playing on that raft a few minutes ago."

They looked out into the water. No raft was there. The two men looked back at each other. They were both aware of the same thought. Which way would the tide have carried a raft? Henry Rose glanced up at the sky. He thought for a moment and then spoke.

"I'm going after them," he said anxiously.

By this time the sky had darkened almost completely. This was to be one of the worst storms of the season. Such a thought strickened him with terror.

"You can't go out there with this storm coming on. This is really going to be a big boy," warned Mr. Daniels.

"My boys are out there on that raft. I've got to find them."

The wind began to blow harder until their words were muffled. They could barely hear each other's shouts above the wind and the sea.

"You'll drown. You'll never make it back before the storm breaks.

"They can't be far away. I'll reach them and pull into shore up the beach." He was running to his boat. Mr. Daniels hollered to him, but he ran on, paying no heed to the old seaman.

The sky continued to darken and the water became rougher. The waves beat harder and harder upon the shore. They splashed on the sand with more force and sent sprays of water into the air. The treetops no longer bent lazily, but the wind blew with all its force, sending sand, leaves, trash, and anything in its path into fury.

Mr. Rose jumped into his boat, started the motor, turned into the sea, and headed in the direction he thought the tide would be carrying the raft on which his three sons were trapped. The boat was travelling against a terrific wind, which slowed him considerably. The wind was becoming stronger, and it was difficult to steer the boat.

He was well into the ocean now. His eyes searched the horizon, trying to locate any little speck that he could tell himself was a raft bearing his three sons. There was nothing but water.

It was nearly as dark as night, though it was only three o'clock in the afternoon. The wind blew more fiercely, throwing water into the boat and nearly capsizing it. Considering Mr. Rose's fear of ocean storms, he was now frantic. He could not see the raft, and surely they couldn't have gotten any farther than this. He wondered if they might have gotten to shore, but felt almost with certainty they had not.

He had never seen a more violent storm in all of his experience on the sea. The boat was filling with water, but still there were no signs of a raft carrying three boys. Every thought imaginable ran through his mind. Maybe they had been overturned by the wind and waves. Maybe they had seen the storm in its making and had gotten to shore. The latter seemed impossible, however. Boys didn't look for storms. The sea was in all of its fury. Mr. Rose was panicky. He couldn't steer the boat. Between wringing his hands together and pushing them through his hair, he could hardly retain his balance. The boat was rocking. His clothes were soaked. The waves reached out for him, and he held little hope for the safety of his sons. He was out of his head, and he was standing in the boat.

The waves were talking to him. He despised what they were saying. Why did they have to remind him? Over and over they repeated those mournful words. "We've got your wife, we've got your sons, and now we're out to get you. We've got your wife, we've got your sons, and now we're out to get yoooooooou."

He was screaming and shouting, "Shut up. Shut up. Be quiet. I can't stand it any longer. Stop torturing me." A huge wave lunged over the side of the boat, knocking him down, but he rose up and continued shouting. "You've got me licked. You've taken my family, even though I came to save them . You've taken my wife, my sons,-you've taken them all but me--now take me. Now take me! Me, me, me, me!" He fell to the bottom of the boat, screaming and holding his hands to his face.

The boat tossed furiously; waves lashed across his body. 40

The thunder and lightning rumbled and cracked, but he heard none of these.

He came to consciousness, but he was dazed. He tried to stand but couldn't. He waited a moment and tried again. This time he managed to get to his feet. As he stood there in the boat, the storm seemed to be subsiding. Soon, however, it broke out again. The oars were back at the cottage, and the motor had conked out. The boat tossed about at the sea's command. Nothing he could say or do could control the sea. Then, he heard a voice. At first, he thought it the voice of the sea again. "Mr. Rose," it said. "Mr. Rose," it said again. Something told him it was not the voice of the sea, but he couldn't believe that it was not the demons who had taken his wife and now his boys. He listened. It called again.

"Mr. Rose. Mr. Rose. Where are you?"

Excitedly he answered, "Over here! Over here!" Suddenly a wave appeared over the side of the boat and knocked him down, causing his head to hit on the seat of the boat.

"Where am I?" His head was swimming. "Oh! the pain." His eyes opened. "What's wrong with me?" He tried to sit up but couldn't.

A nurse came to his bedside and persisted in quieting him. "Now, you'll be all right, Mr. Rose. Just lie down."

"Where am I? I can't remember anything."

"You fell and hit your head during the storm. Do you remember now?"

"Oh, yes." He thought for a moment. A worried expression came over his face. "My boys were killed in that storm. Weren't they?"

"No, they're safe. An old fisherman came upon them just before the storm broke loose and picked them up." Henry Rose appeared relieved. He smiled.

"Thank God, they're safe." His eyes closed, and he fell asleep.

Editor's critical comment: We think David Mccants can do better than this. This ending lacks finesse. As a matter of fact, the whole story is naive.

[/ogether

We were walking on the dusty road, Just my dog and I, We were walking to a place unknown To those who passed us by. And as we walked on side by side Each, thought we seemed to share Each,trouble seemed to drift away With th,e sea-filled air. We laughed together, "talked" together, played together too, Such, comradeship and loyalty are shared by very few.

When we reached our destiny

We sat and watched the bay, For hours until night had put Her foot down over day. We began the journey homeward, Both tired and content, I knew he thought that days like this Forever could be spent. Only dreams are left for me But if it could be so, I'd find a spot forever Where he and I could go.

WENDY KALMAN '58

memoriam

ReflectionsWritten

UponThe DeathOfClaudeW.

Estes.Jr.

We had climbed to the top of the Natural Bridge and now looked down into that great chasm far below. That gorge separated us from the opposite cliff. Claude turned to me and said, "Let's cross over to the other side."

This was a difficult task. The high wooden railing which lined the highway as it crossed the bridge of stone left no firm footing on the outside. Nevertheless, and possibly because of the very danger, we decided to cross over.

We inched our way across. A series of concrete abutments presented our chief difficulty. As we worked our way around each one, we realized that a slip of the foot would send us plunging down to the stream, 200 feet below.

Claude led the way. As he climbed around the first abutment, I grasped a cable with one hand and locked my other in his.

After he had maneuvered himself to safety, he likewise helped me across.

Three years later I stood and watched as once more Claude prepared to pass over The Eternal Bridge. This time he too led the way. But this time I could not follow immediately. But I know he has reached the other side and is now waiting for us. His example and faith will be as a hand grasping ours to steady us as we prepare to cross The Eternal Bridge.

The fullness of life is not measured by its length. "He also that had received two talents came and said, Lord, thou deliverest unto me two talents: behold I have gained two other talents beside them.

"His Lord said unto him, 'Well done, good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.'" -Anonymous.

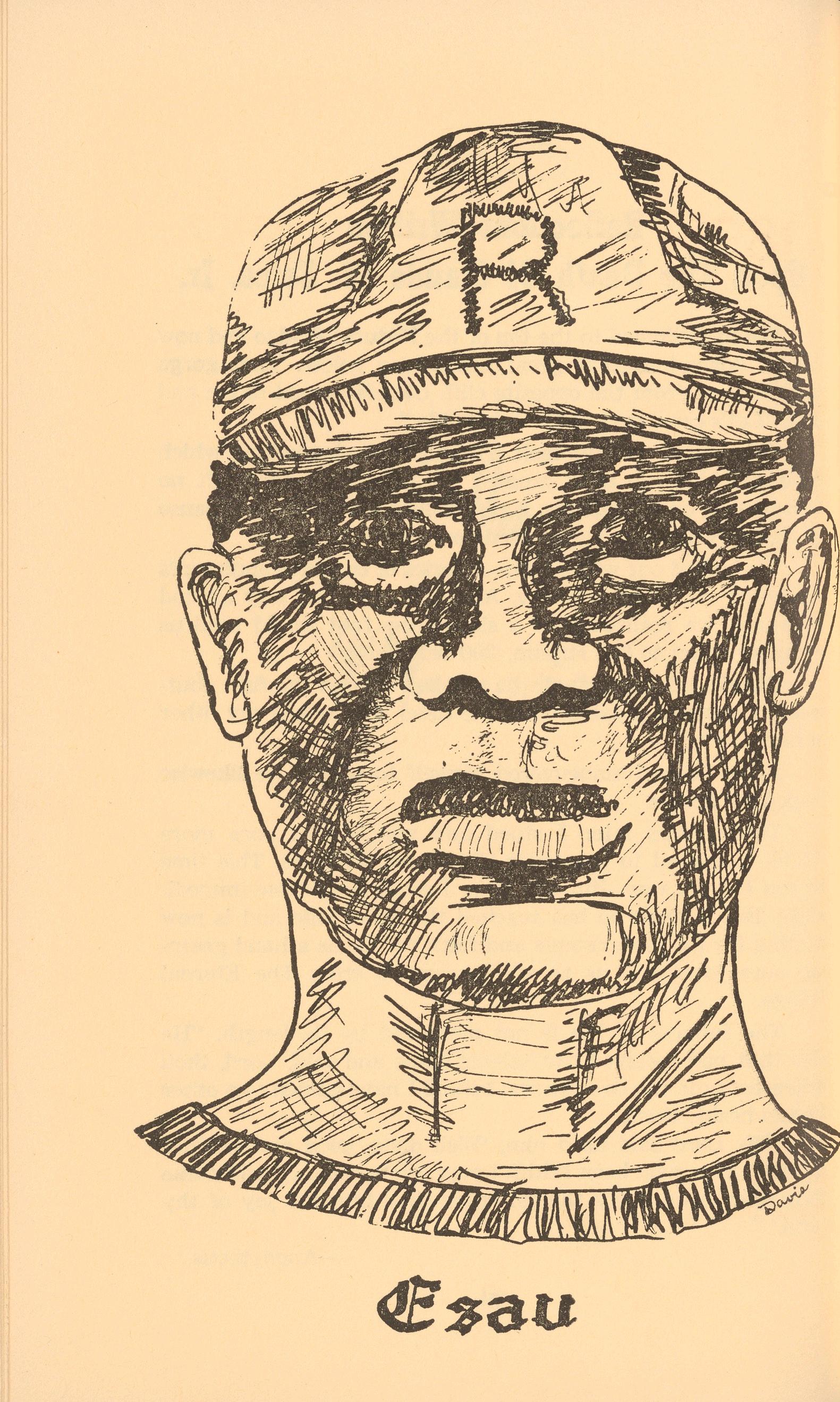

1895-Esau Brooks-1957

Where's Esau?

This was, perhaps the most familiar sound around Milhiser Gymnasium. This lovable old man who had taken care of many Richmond athletes down through the years was always near by when this question was raised.

Puttering around in the equipment room, lining the field or just giving out soap and towels, he always wore a smile. He seemed uncanny in his memory of the small things the boys would ask of him. Those special shoes, pads, pants, ol' what have you, were carefully set aside for their user. He never forgot those men who were late coming from practice. Nearly always there would be soap and a towel lying in front of their lockers. From these deeds all athletes learned to love the old darkey in the beat-up baseball cap and tee shirt.

Esau was the master of the wintergreen bottle and adhesive tape. With tender and skilful hands he would massage torn ligaments, unkink sore muscles, and strap up bruised shins and arms. Many are the times that he taped the wounds of Mac Pitt, Dick Humbert, and Ed Merrick when they were the gridiron greats of the University.

Of all the tributes that can be paid to Esau, the greatest would be: he loved each man. Not just the great athletes of our school, but all those he came in contact with were his favorites as well. Never haughty, though there was much over which he could have been; never servile as at times he might have been; yet beautifully humble with a subtle dignity that made him at home in any company.

When he perished in the fire that destroyed his small house on Ridge Road, he left behind little of the world's goods. But he left a host of friends, black and white, who gathered in the Mount Vernon Baptist Church to say a fond farewell.

In the last few months of Esau's life great sorrow came to his home. With the death of his beloved wife, Willie, he lost his bulwark on which his life stood. When he could no longer go home to Willie at the end of day, Esau spent most of his waking hours inside Milhiser Gymnasium.

Just a few hours before he met his death he was in the training room patching wounds and getting Ed Merrick's boys ready for their game with The Citadel.

This brave winner of France's Croix de Guerre was a gentleman as surely as he was a trainer. Though he died at the age of sixty-two after serving the University of Richmond for forty-three years, he'll live forever.

-"SNOOKIE" LEONARD

Here it is-the NEW Messenger. It doesn't claim to rival the Atlantic Monthly, nor does it attempt to "drag" the Pogo bandwagon. Some magazines attempt to be the official organ of the scholarly sophisicates while others cater to the wit of the cultured cro-magnom. To quote Christopher Fry we would like to say "With us it is not so; ours is the iron board for all crumpled indecisions." Contrary to some schools of thought the Messenger is not a product of the staff alone. Everyone is welcome to get into the wash. We welcome any constructive suggestions or criticisms. In other words, if ya' don't like what you read write something yourself.

Contest Announcement

Phi Delta Epsilon, the national journalism fraternity, is sponsoring a short story, essay, and poetry contest for the purpose of encouraging more student participation in literary activities on campus. Awards of ten dollars each will be given for the best short story, essay, and poem submitted by undergraduate students of the University. Contest rules are as follows.

1. All manuscripts must be typed double spaced on plain white paper.

2. Short stories should not exceed 2500 words in length, essays 1500 words, and poems 150 words.

3. All entries must be submitted by February 14, 1958. Entries should be sent to Connie Butler, South Court, Westhampton College, or Ken Burke, 1711 Huguenot Road.

4. Members of P.D.E. and The MESSENGER staff are ineligible.

5. Manuscripts should be unpublished previous to entry in the contest.

Winning entries will be selected on the basis of originality, literary form, and general appeal. Contest judges are Miss Joan Corbett, Mr. Joseph Nettles, members of P.D.E., and the editors of The MESSENGER.