Dr. Raymond Bennett Pinchbeck

1906-1957

1906-1957

University of Richmond

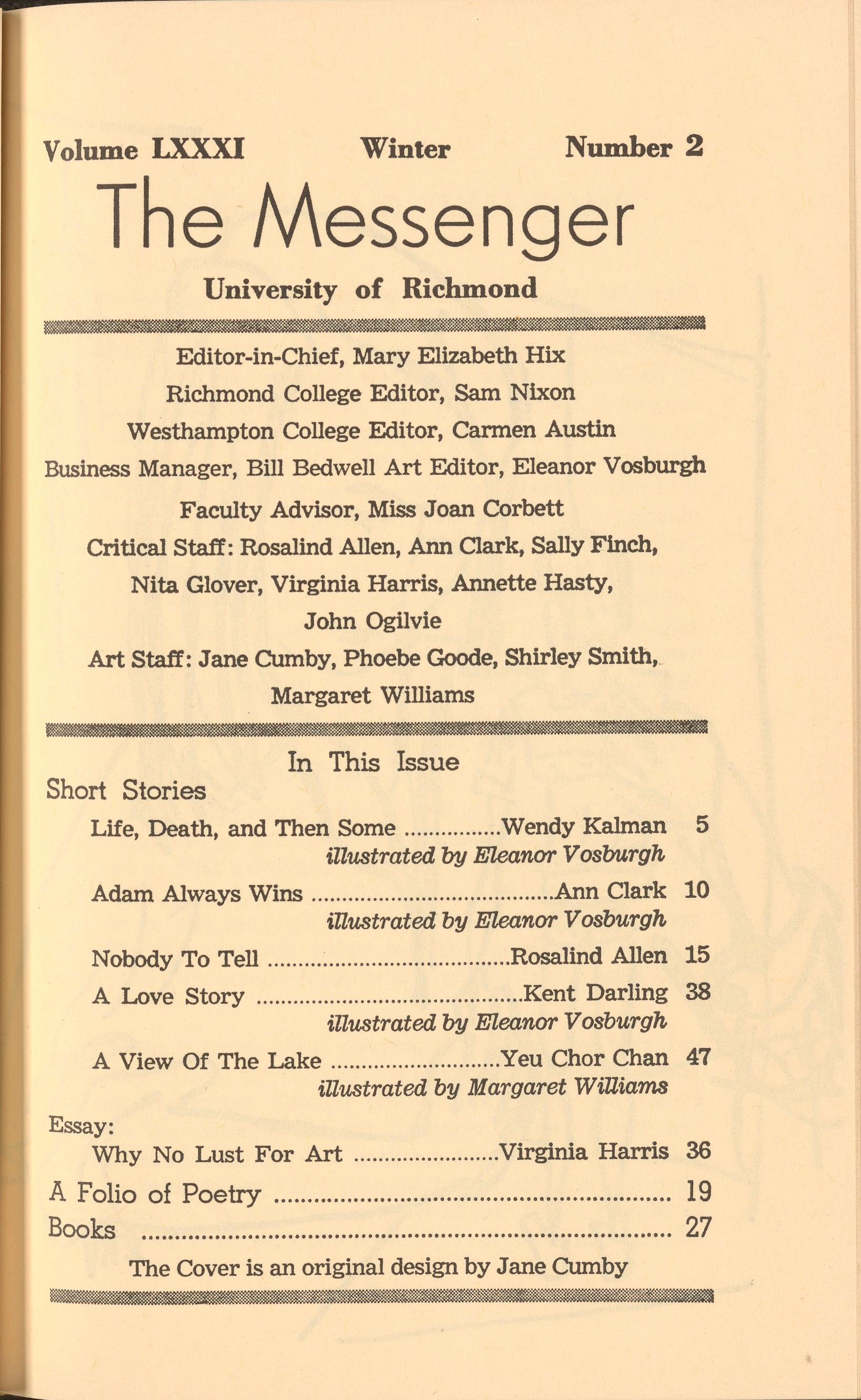

Editor-in-Chief, Mary Elizabeth Hix

Richmond College Editor, Sam Nixon

Westhampton College Editor, Carmen Austin

Business Manager, Bill Bedwell Art Editor, Eleanor Vosburgh

Faculty Advisor, Miss Joan Corbett

Critical Staff: Rosalind Allen, Ann Clark, Sally Finch, Nita Glover, Virginia Harris, Annette Hasty, John Ogilvie

Art Staff: Jane Cumby, Phoebe Goode, Shirley Smith, _ Margaret Williams

She sat in the lobby staring out the window, her book still open, lying on her lap and her legs wrapped in a rubberlike fashion around the legs of the chair. The dampness in the air made her shiver slightly; pensively, she curled helself in the cushions, closed her eyes, and found herself enveloped in a whole new world. On the other side of the window in the lobby there was a powerful mountain reaching possessively towards the sky, wincing as the other mountains folded in a green pattern along its sides. At the foot of this gigantic piece of nature, there in a little nest all its own, lay the Inn. It had a toylike appearance from a distance which added to the fantasy; when the lights beckoned through the dark night, it became a castle made for pretending. This was Eagles Mere; the rain on the window sang a monotonous melody bringing the past swiftly back to the small girl curled pensively in the chair in front of the window. She sighed, quietly contented-this was the place she had dreamed about ever since she had heard it mentioned.

Jenifer Woods was a homely child, although at this stage she did show signs of a few pleasing possibilities. Rather tall, wiry and at that awkward phase of adolescence, Jenifer detested all mirrors for they reflected the horrid truth that she managed to put into her subconscious mind at other times. The very idea that her father was the manager of the Inn encouraged her non-conformity and played havoc with convention.

The clock struck four, piercing the silence and breaking the steady rythmn of the rain. Jenifer suddenly realized that this was the night. Feeling strangely cheerful, she rushed down to the cottage, dressed haphazardly for dinner and approached the dining room with her usual sulky expression. "No one must know," she thought to herself, "no one must even suspect." A cold fear gripped at her heart; tonight of all nights she must act quite normally in front of her parents;

she forced an expression that miraculously passed for a smile and relunctantly began to eat.

It seemed like eternity until enough time had elapsed for Jenifer to excuse herself from the table without causing any question. She raced to the cottage, threw on her old clothes -at last she was free! Outside once more, she headed for the mountain trail.

The sky was black with darkness and the stars decorated the heavens with a cold, foreign luster. The Inn was too far up for the moon to add its beauty to the splendor, but the haunting darkness became a kind of magic to the strange way of this mountain country. Jenifer ran, her heart half crazy with delirious anticipation! The cold air bit at her face as the winds screamed from the mountain's peak reaching the trees at the Inn with a temperate murmur, chanting weirdly into the night. The trees, instead of looming separately into the sky, swayed like a mass army with the wind Each was bunched with the other; each connecting its own part of the forest.

Her strong, young legs carried her up the mountain trail; the streams gushed in an unorganized pattern past the rocks that had stood without flinching in their paths for centuries. The mountains beckoned Jenifer from their lonely heights. "They have a closeness," she thought, "that does not let you feel entirely free." The strange child did not realize that dur• ing all this time she was so deep in thought that somehow she had managed to loose the trail. "Heavens no!" she fran• tically thought, "Anything but this!" She was paralyzed there in one spot and the more she tried to move, the stronger the soft earth held on to her feet. "Quick sand!" . . . the thought began as a frightened whisper from within, surging to a wild crescendo that coated the child's brain with the cold, black fear of death.

What power stirs the subconscious to produce thoughts that even at the time of death bring comfort to a human soul? There was Jock, a pet mouse; Elizabeth, her oldest and dear• est friend, who although just a rag doll knew all the sorrows of Jenifer and through all her trials had managed to keep the same non-committal smile on her face. There was Kimy, the big lovable family collie, "Brownie", the pet hen-the only thing that ever worshipped her, and her room at home.

Her quiet, messy room with the walls that held her secrets well and groaned with all the pain shared from an unhappy adolescent. "Arnold, dear, wonderful Arnold," thought Jenifer, "He will never know, but will worry so when I do not come."

Arnold was a Swede. A big, husky, rather middle-aged man that had found happiness in the solitude of the serene forest. Jenifer had discovered Arnold on one of her walks, and as they met each day, a beautiful bond grew between them. The Swede lived in a one-room, hand built log cabin, and although it was rough, to Jenifer it was the most comfortable place in the world. Jamey was Arnold's horse and only com• panion, so together, man and beast lived side by side unmolested by the pace of modern society. Arnold was Jenifer's brother, father, lover, and God. Jenifer, to Arnold, was an unfortunate bundle of ugliness that made him feel as though he were giving life to a tormented heart. He could understand the ways of this unhappy child and would sit for hours, smoking his pipe, listening intently to the gloomy dissertations of Jenifer's life. Together they had roamed the woods, fished, hunted, swum, and every afternoon they would ride Jamey until twilight, when they would take Jenifer to the clearing in the forest and she would slip away with promises of another happy reunion.

Jenifer's parents would never understand. They were so cold, so busy all the time. It was true, Mr. and Mrs. Woods were very busy with the guests at the hotel and had little time to bother with Jenifer. They were so ashamed of her ugliness and sulky ways that they had shipped her off to

boarding school at an early age, always encouraging her to visit a friend during vacation. Whenever Jenifer entered the room she was tactfully, but definitely whisked away or told to go out to play. Totally unhappy, and completely desperate, Jenifer had decided that tonight she would go to Arnold and persuade him to take her away. If he had refused she was going to kill herself.

"I'm dying," she thought, "Now everyone will be happier." The night wore on and the impending blackness reached a depth unknown to Jenifer before. Slowly she shut her eyes, letting the darkness take command and lull her gently to eternal sleep.

The seasons passed and five years later the Inn, still boldly juting from the horizon, entertained guests just as before. It was a crisp fall morning for the sun had not yet pierced it's rays through the chilling mist, when a weary traveler approached the entrance, dismounted and strolled into the lobby to stand before the blazing fire in the hearth. The Inn was comparatively deserted for fall was closing time and only a few guests remained. The silence was broken by Mrs. Woods who, in her well trained way, was reciting her usual welcoming address. "This is your daughter, isn't it"? asked the man pointing to a portrait above the mantle. "Yes," was the enthusiastic retort, "She was such a lovable, happy child; everyone adored her, and our life has been so empty since she has been gone. We were so proud of our Jenifer, always at the head of her class, and a born leader. She was everything we ever had, but now .... "

"She's gone?" asked the traveler, "When did she leave?"

"Five years ago her shoes were discovered at the edge of the quicksand bed, it was so tragic ... she had so much to live for . . . such a happy child ... but why speak of this? My husband is in his office, may I take your name to him?" The man had scarcely heard the question; he was looking at the mountain on the other side of the window. He turned and headed for the door. "Arnold", he murmured, "My friends call me Arnold".

Outside the Swede paused and drew in a deep breath. His memory flashed back and he remembered the little bundle of ugliness that had brought him so much life. He smiled and thought, "This is what she really wanted: freedom and peace."

8

He mounted Jamey; together and alone once more, they headed for the mountain trail.

The day wore on and late in the afternoon the stillness began to creep back into the lap of the mountains. Once again the earthly creatures settled down to receive dusk. The mountain lake was serene, soothed by the late afternoon rays of the sun, and the trees swayed drowsily to the unsteady rythmn of the winds.

-WENDY KALMAN '58

Messenger ...

A desire to uphold the high caliber of fineness and originality which The Messenger maintains has caused the editorial board to choose carefully and objectively the material that will be included. However, without representative contributions, The Messenger cannot hope to provide a true sample of University talent. The Editors urge that those students interested in creative writing or art offer their selections to the Staff for consideration. We would like for the student body to feel the same pride and interest in the magazine as we, of the magazine board, do. By your support and contributions The Messenger will achieve an appeal that is both collegiate and intercollegiate.

-The Editors

Elizabeth McKeldin had a difficult time locating her seat in the car. Finally, after a slow and patient search, seeking and asking various questions, she found seat twenty-six on the aisle.

The car was fairly crowded with only a handful of vacant seats scattered throughout. The porter brought Elizabeth her three suitcases. How the large cumbersome bags would fit into the shallow rack above bothered her.

Being twenty-one, free, and on a two week vacation to Florida had the occupant of seat 'twenty-six' very excited and happy. The first trip to the warm sunny state is usually a glorious and long awaited experience for almost anyone. She was also looking forward to seeing her brother and sister-in-law in Palm Beach.

It had been two years since her Mother and Father's twenty-fifth wedding anniversary when Bob and Ellen were last home.

They ran a small jewelry and coral shop on County Boulevard in the town, and made quite a prosperous living. It had belonged to Ellen's father before he died.

The train started up, so Elizabeth joined the others in waving and blowing kisses to those on the platform. Jim looked rather dejected standing there with the McKeldins. He did not like having to part with Liz anyway, especially after she had just arrived home from her Northern college for the long awaited spring vacation.

The train rapidly picked up speed and soon Elizabeth felt like she was gliding along, cutting a smooth path from the crowded bleak city to the wide rolling country side.

Small farm houses, adorned with either the reddest and newest model car, or else the oldest and most dilapidated one in the front yard, flew by as if they were just insignificant specks.

It was now four-thlry and in approximately twenty-two hours she would arrive at her destination. There would be no transferring or getting off the train unless for a soft drink on a station platform, so Liz settled herself comfortably back in the reclining chair.

She loved people and was sorry that the seat next to her was vacant. She amused herself by listening to the conversations from the various passengers surrounding her.

Two ornately dressed old ladies were seated behind Elizabeth. They kept up a steady conversation from the time she aboarded until their debarkation in Florida. She gathered that they were both widows who lived near each other and were members of the same Philadelphia club.

"What did you think of Marjorie Tuesday afternoon! I've never seen such a display. There's no reason for her to wear all that atrocious purple."

"It seems she wore the somber shades while Milton was alive. Now that he's gone, she's doing quite a bit of celebrating. Marty told me that after the party she went out to dinner with the house guest who apparently had recently lost his wife. Quite a catch, that Raymond Raison! I hear that he adores parties and trips. I can't see Marjorie travelling. She despises it!"

Elizabeth soon grew fascinated with the old ladies, who were so concerned about the gay Marjorie. It was a shame they were so envious. They probably would do anything to be young again, or, to be occupied.

"Next time we come, Virginia, we'll have to fly. Darling, I'm certain you'll love it. You should have been with me on my Ireland trip. We were up, and then down, and I didn't even know the difference."

"I know that, Kate. You've told me before. If we're going to go places together, you'll have to be satisfied with the train. Just the thought of a plane nauseates me."

After this, they were silent for a while, so, unable to wait any longer, Elizabeth rose and pretended she was looking for something in the rack overhead. The ladies were just as she had expected. One was very small with glasses and an abundance of make-up. Her lips were dark rose lines with matching spots in the middle of her cheeks. Her silver grey hair had apparently just been done up because each tight little curl was just in Dlace. She had on beautiful drop sapphire

earrings which complemented her periwinkle blue tweed suit, light blue scarf and gloves and dark blue bag. Elizabeth had never realized the assorted shades of blue.

The blue lady's companion was adorned just as heavily with rose; rose lipstick, rose suit, gloves and blouse. One could not help but notice them when passing through the car. Not that it was necessary, but one set the other off with the great contrast in color. Elizabeth smiled when she saw the hair of the second. It was practically silver blue with more blue than silver, and just long enough to give the appearance of a carefully combed French poodle. There were large gold shiny earrings on her protruding ears.

Having resettled herself with amusing visions, Elizabeth anxiously awaited further conversation, but with the two ladies silence reigned, so she eavesdropped on two teenage girls across the aisle. They must have been about fourteen for their faces were clear and shiny, and their eyes wide with novelty and excitement. For them, the trip was broken up by innumerable trips to the ladies lounge, either for a hair combing, or practice for inhaling a cigarette in a sophisticated manner; or maybe, just any manner at all.

One said rather hurriedly to the other, "Did you see that soldier.? He looked right at us. He's the fifth one who's passed us. I wonder if they're all going to that club car that was just announced."

"There's only one way we can find out."

"Jane, you wouldn't go to the club car?"

"Well, not unless you went."

"Well, what do you thing? Shall we?"

"Let's wait to see if some more go by. The others were rather short anyway. Does my hair look all right?"

"Yes, for the tenth time. Gee, if you comb it one more time, it'll fall out."

"The door just slammed. Here comes another ... Heck!"

The subject of soldiers was dropped and clothes were discussed. Elizabeth looked over at the great motion of hands describing a particular "dreamy" blue evening dress.

"You'll love it, Beth. There's piles of net in the skirt. You remember Esther Williams in that movie we saw, well, it's just as wide as that yellow gown she wore. And the top fits real tight, and Mommy let me buy it! It has little silver

straps, but I'll have to buy a strapless bra to wear under it."

"Really, how will you hold it up?"

With that, Elizabeth looked out of her window because she could no longer contain herself.

"Gosh Beth, don't be so silly-shhh! There goes the door again."

Once more silence reigned except now the old ladies were discussing quite rapidly and emphatically another 'Marjorie'.

Two rather tall blond boys in military uniform glanced knowingly down at the supposedly occupied and unobservant girls.

"All right now, Beth, let's go. We can order a coke -or something."

"I've never been in one before. What'll we do? What'll we say to them? How old shall we be?"

"Let's be eighteen. They'll never know the difference."

"Let's be sixteen. They might not believe me."

"All right. We'll go to the ladies room once more and then back to the club car. Are you going to smoke?"

"Of course; after all, we're sixteen!"

"I'm scared."

So, they made their way to the ladies lounge and after about a half an hour, returned looking still wide-eyed and fourteen.

Elizabeth turned around and followed them with her eyes, only to hear;

"Virginia, do you think those children are going to the club car?"

"Of course, Kate, where else?"

"Well, really!! Probably chasing those seven soldiers who have gone through."

"Have you been counting, Kate?"

"Hush, I think that's horrid. Those darlings by themselves with those rough boys. What do you think they're doing? Drinking?"

"And, if they are?"

"I wouldn't be seen in one of those smoky, smelly cars! They're always so packed and you never get service. Really!!"

Elizabeth relaxed to the detailed horror story of one of Kate's visits to a club car. She had practically been smothered by a sixty year old Boston lawyer.

"~t•s play some gin. Have you cards, Kate?"

"No, ask the porter."

"Cards," he said, "were in the club car, three cars to the rear." "Well, I'll go get them, Virginia. You just wait right here . . I'll be back in a minute." ·

"Are you going to the club car?"

. "Where else? How else do you expect we'll get cards?" "How long will you be?"

"Would you care to come? I might have a drink. rm absolutely dry as a bone."

"Really!! ... Well, just so long we don't stay. We should check up on those children, anyway."

Elizabeth was awakened from her hour's nap by the giggling and laughter of four happy and contented females noisily returning to their seats.

-ANN CLARK '58

She, Emma Slaughter, had always arranged the flowers for the sanctuary, at least ever since her husband had passed on to his glory, fifteen years ago. "Dear William," Emma remembered-she was thinking that this Sunday was the special one when the flowers were placed in the church in his memory. She could already see what the church bulletin would say: "The flowers in the sanctuary today were placed here by Mrs. Emma Slaughter in loving memory of her husband, the late William Reuther Slaughter, for twenty years a faithful member of the church." There in the black and white it would be and everyone would know. William had done so much for the church-Emma wanted to be sure the people didn't forget him.

Emma was wearing her new lavendar silk to church today-William would have liked it-he thought she looked so nice in lavendar. It was such a shame though, having to wear the choir robe during the service-it was always hot and wrinkled whatever she had on. Finally she was readybags, gloves, and (she thought ruefully) last year's neutral straw. But no one would know, she smiled and told herself -the deep purple band and bow made it "new"' again, especially with the lavendar dress.

Before Sunday School Emma decided she would go in the sanctuary and look at the flowers-just to be sure they still looked as fresh as they did yesterday afternoon. As soon as she opened the door and looked in, she stopped. There were the flowers, both vases of them, on either side of the baptistry, tall pink glads-but the cherry laurel was gone from around them-the cherry laurel she had brought from her own back yard, from the tree that grew outside the bedroom window, hers and William's-William's favorite tree. The green of the cherry laurel had been perfect bunched around the pink glads, she thought-then she was angrythat anyone would dare to change her arrangements, espe-

cially today, William's day-the bulletin even said it was his day. Emma remembered two weeks ago when she had used some long stems from the nandena bush with red and yellow tulips--and the nandena had been missing when she got to church on Sunday. She had asked the janitor and the church hostess and Miss Mildred, the pastor's secretary-and none of them knew who had disturbed her arrangements. So Emma decided she would ask Dr. Sutton-he was the pastor, wasn't he-he would have to find out what had been happening-why it was almost like stealing-to take things out of the flower arrangements, stealing right in the church, Emma Slaughter thought with horror. She knew Dr. Sutton would realize how serious it was-Dr. Sutton was such a wise, kind man.

Emma wasn't going to Sunday School today. Her circle was presenting the new drapes to the church, the ones in the Church Parlor-Emma had been on the committee, so of course she had to be there-she had explained all that to her class--her girls, all of them young working girls whom she, Emma Slaughter, had brought into the church-they were her greatest pride. But today the drapes were being presented-so she couldn't go to her class.

Emma remembered how hard it had been to convince the committee which drapes they should buy-she and Mrs. Bennett and Martha SaWYer and Miss Mildred had all gone together to decide. The other three had seemed so intent on getting solid green drapes--to tone with the carpet, until Emma had convinced them that a large floral pattern would be so much better. Finally-Emma smiled-they had all agreed to get the beige ones with the large rose flowers-and Emma was pleased. Of course, she didn't want to influence them, she had explained, but the green was impossible-too plain for the Church Parlor.

The parlor door was closed when Emma got there-she was disappointed to be late. She slipped around to the back and sat down. Martha SaWYer was already presenting the drapes on behalf of the Mary-Martha Circle (which Emma thought should have been named the Eleanor Palmer Slaughter Circle in honor of William's dear old aunt who had been a missionary in Shang-hai for so many, many years-but

right after church-she would tell him about the circle getting the wrong drapes for the Church Parlor and the cherry laurel being taken out of William's flowers and the nandena disappearing two weeks ago and . . . But then it was time for the choir's anthem-she stood up with the rest of them-she was right next to the organ on the second row and she couldn't understand why Mr. Carter had put her there-she had always been on the first row until last Wednesday night-and she had told him that it made her head ache to be so close to the organ. He had just smiled and said, "Well, we'll see-we'll see how this works out, Mrs. Slaughter-we can always change again later. Then they were singing-"Jerus-a-lem, Je-rus-alem-O turn ye to the Lo-rd God-0 tu-rn ye (and the "turn" went way up high and Emma Slaughter came out on it with all the strength of her voice-she liked the high notes--and Mr. Carter was looking at her, not smiling at all, but with a cold hard look on his face-and Emma couldn't understand why he had to look at her that way if he didn't like the way the choir was singing-he must be looking at the tenors in the row behind her)-and then they were through with the anthem and sitting down again-and Dr. Sutton was preaching about "Our Church in Our Town"-Emma had noticed the subject in the bulletin-and then she was checking to be sure there wasn't a mistake in the notice about William's flowers--but there it was in black and white, so everyone could see-"The flowers today ... in loving memory of ... " Then church was over-and two ladies had joined the church, so Emma Slaughter had to rush down and see them about joining the Mary-Martha Circle before anyone else asked them and she had to tell Dr. Sutton about everythingso she didn't go back to take off her choir robe-she just walked down into the crowd at the front with the stiff white collar around her neck and the blue choir robe coming open in front so the new lavendar silk showed through. "I'm Emma Slaughter,'' she was saying, "so very glad you joined our church-we have the best pastor in town, you know-now you simply must come to the Mary-Martha Circle-it's meeting at my house this Thursday-here, let me write it down for you-I'll be looking for you-now what did you say your name was?"-saying that to both of them and then waiting (Continued to Page 49)

Margaret Logan Ball

Kenny Darling

Ann Hunter

Barbara Matthews

Betsy Minor

Sam Nixon

With Art Selections By

Jane Cumby

Margaret Williams

The tempo c:reepsin under yoor skin.

Y CYUfeel a looseness setting in.

If yoo dig fhat stuff then, man, you're "right," And yoo'll be there /or the rest of the night. Y oo'll find your feet make a sudden shift

As they swing on into "Minor Rift,"

And your toes will feel like they've got to roam When the guys break into "Flying Home."

There's Harry James, Krupa's drum, Benny Goodman, Lester Young, Lionel Hampton, Vernon Brown. Man! Those cats are going to town.

And Batchmo's grinning from ear to ear. There's a sudden tighten'in the atmosphere, Gene goes wild on the drums. They yell: "Go on Krupa, give 'em Hell!"

The trumpets sc:ream ... the saxes moan, Then the base ... then the trombone.

Excitementrises with every beat, Andsoon the crowd is on its feet

Yellingfor Jazz, Jazz, Jazz, Man! Jazz,Jazz, Jazz!

It'sa southernsym'Ph,ony p7,ayedby brass. It'sJazz,Jazz, Jazz!

If Beiderl>eckecould be here now

He'dshow these cats the why and how

Ofplaying dixie7,and in the style

That twenty years ago drove them wild. He'dtake that trumpet and make it croon

WhileBasie tickled out a little tune,

Andthen with Armstrong blowing high

They'dhave them rocking by and by.

But they come and go, and it's still the same; A musical craze with a frantic name; A rocking road of no retreat;

TheP<>Undingpulse of Basin Street.

Jazz began in the golden haze Of bathtub gin, prohibition days. Then it kept quiet for years, but now

The boys are back and raising a row. Miller went, but he's here again. He plays it cool and just the same.

All the guys are swinging now.

Its Jazz, man, it's Jazz! They play it high, they play it low, They make it jump, they make it slow.

They play music that can be heard From New Orleans to Old Pittsburg. It's Jazz, Jazz, Jazz, Man!

It's Jazz, Jazz, Jazz!

It's a southern symp1wny played 'b-ybrass. It's Jazz·.•. crazy Jazz!

-BETSY MINO!

For there sha,ll arise false Christs and false prophets, and shall show great signs and wonders ••. Matthew .24:.24

They sat in the darkened room wondering with their duck-for-a'PP'les minds "Who will be the Phoenix to rise from our ashes1» and Stravinsky fio<>dedthe room with hi-fi pizzicato.

There was one, negligent in gray flannel, who had the biggest a-pple of all wedged in his teeth and tried to be his usual strident self, shouting "I willJ"-but it came out a'PPle-muffled.

Besides, three of the duckers were women and they joined hands around One who had picked his a'PPleup by the stem. "Look!" they cried. "How gently he takes the stemJ» (The hope in their voices would h<zvekilled War)

Rejoicing, they willed him their children's futures. Rejoicing, they looked up-where Heaven shotild have beenand naturally no one saw him wink-even radar couldn't catch it.

When the ashes are cold and dry and blowing the Phoenix will rise slowly, splendidlya little sorry no one is left to watch his majestic flight towards the sun.

-MARGARET LOGAN BALL '57

I walked through all, infinity, Beyond the sphere of men, I lived a thousand lives in one, I died with every friend.

And yet no secret could I find To this one life that's lost, Had I but died a million-fold, The questions still would come.

My life is fashioned from a dream, Beyond the rainbow's tint ... A song of endless, timeless space-The crumbling sobs of greatness.

-BARBARA MATI'HEWS '59

Broken memories, Scattered dreams, A page of eternity, Fate's obituary, Love's marriage, A sprig of sin, Death's calling card, 0, Christ!

-ANTHONY NIXON '57 24

Other women, not Being so inclined, Finding themselves unfit Fuel for your mind, Hid in secret shame And burned out their desire Envying my name Who kindled that fire. They would think beauty how, Yet know it was not halfCalling you brother now I think of this and laugh.

-ANN HUNTER '57

I do not, Zike Penel-Ope, Have need for any tricks or tapestries

To keep the lovers back: One or two have stopped But being bored have gone, Finding nothing that was not meant for you.

The dog plays on the 'floor like a puppy, And I am not wrinkled with waiting; But do not be too long in comingI have heard, already, in the night

The eager breath of the unicorn And found his footprints at my door. -ANN -HUNTER '57

B 0 0 K s

Bebecca West. "The Fountain Overflows." New York:

Viking Press, 1956. $5.

After nearly twenty years, Rebecca West has given her readers a novel which probably will, if it has not already, reach the popularity of her previous books. The Fountain Overflows is an ususual story of the lives of ususual people who are essentially in a world of their own. The time is late Victorian, and the story itself is written as a rather typical English novel of that era, though with autobiographical aspects. After years of psychoanalysis, it is indeed refreshing. The reader will find himself gradually in the grips of a seemingly quiet day-to-day account of a bewitching family.

The household is headed by Piers Aubrey and his wife, Clare. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say Clare Aubrey and Piers; for that very appealing lady very quietly rules a circle that revolves around her husband. In a family with such a wistful quality it is not surprising to find each member thinking and feeling in the terms of art. The father is a brilliant journalist to whom responsibility, and money, when he has it, mean nothing. Mrs. Aubrey is an equally brilliant pianist and a wonderful mother. Unfortunately, the oldest child, Cordelia, is an intense, but remarkably bad violinist. The twins, Rose and Mary, show promise of playing very well; and the youngest, Richard Quin, has the rather touching quality of being himself.

The narrator is the child Rose, which perhaps explains the stiffness of the dialogue at the beginning of the book. The following years of their life are seen through an imaginative child's eyes.

Miss West convincingly combines realism with fantasy. The latter quality is presented simply and rather innocently; a child's explanation of a disturbing personality among the people she loves. It is also a way of presenting an undercurrent of emotions, and serves as an outlet for the younger children in the form of their "make-up" characters.

Actually, the mother is the one who makes the book as delightful as indeed it is. Clare Aubrey lives. She has a capacity for love and understanding which, in varying degrees, the others lack, though each of them especially the children, has a deep sense of family loyalty and an uncanny insight of mood. These feelings are largely due to their desire to protect their mother. For her, the fountain overflows.

In order to live in a sensitive confusion, she gave up a career as a concert pianist, and devoted herself to guarding her family from a trivial life. She must deal with the cooking, the cleaning, and an overabundance of bill-collectors. This leaves her untouched, absentminded, and endearing.

To say that Miss West's characters are eccentric would be to exaggerate their difference from other people a little too much. Instead, it would be more accurate to say that they are a bit more imaginative, tense and dedicated than their neighbors. Indeed, it is difficult for the reader to determine who is ususual, he himself, or the Aubreys.

-SALLY FINCH '60

Arnold Toynbee, An Blstorlan's Approach To Bellglon. New York: Oxford University Press, 1956. $5.

Seldom, in reviewing a book written by an intellectual of no small repute, is one able to distinguish a conflict generated within the mind of the individual who has avowed to express a point of view within which there are imposing barriers. But the occasion has presented itself.

In Toynbee's new book, An Historian's Approach To Religion, there appears such a conflict, almost of two intellects comparing notes, without giving ground on a single point. This struggle appears, then, to be between monotheism and deism: each a whole and integral part of the mind of Toynbee. Aside from a somewhat ostentatious pervasivity, there ls an earnestness, a great and vast curiosity, and a warming sincerity in which the author has poured a collection of facts resembling cement blocks of unmovable weight and indefeatable mass.

Whether or not there is a plea for undogmatic theologistics can not be properly decided, for here in the mention of a phase of the theme of the book, indecision is prevalent.

The man, Toynbee, seems to be questioning himself concerning what he really expects from theology at the same time that he writes down what he should get. In so doing, he manages to inflict difficult passages on his willing subject with great ease and dexterity, at times even doubling the load at the expense of the meaning.

However, the book has the food, and the facilities, for creating havoc amongst the congenial brethen of the conference table and seminar. Active participation in discussion is bound to follow the introduction of any one of the numbers of controversial statements to be found in the pious pages of the volume.

Professor foynbee goes through his evaluations of the religious sects of our time and of past time thoughtfully and thoroughly. He covers the great ones, and the causes and the foundations upon which rest the small ones. He covers his subject as only a true historian of great statue could do, but he seems set on the conception that certain religions have a leading place and others do not. This leading place is subimplied to mean in a world of existing theoretical purity and self-impoverishment. Of course, he allows that man can only strive for this goal, and so he pushes toward it with unconsciously conceived injections of spiritual strength.

Toynbee speaks of parochialism and the hybris-"That inordinate, criminal, and suicidial pride which brings Lucifer to his fall." The first of a long line of remonstrations, these are used to make us, the uninformed, aware of what may befall us when we allow our malignant pride to grow unmolested.

It is apparent, however, that his warnings are too theoretical to effect a change in the socialized society wherein most of us maintain our meager existence.

I fail to see where this scholar, from the tracks which lead deep into his memory as seen in the lines of the book, can supplement no less narrow a view toward Judaism and Catholicism then he does. Nor can I see how he is able to devour so readily their good and useful, in the days of modern, radical and too often impersonal political policies, points while professing somewhat vaguely that there is a one, true, certain salvation for the mind and intellect which is evidently available only through Christianity. It is quite an interesting question, or questions, as they are reconsidered.

In effect, Toynbee has picked the teeth of Judaic Western Llberalism, and done a good job of it. He has likewise masticated the body of Judaic Western Communism.

He says, though, that the fight of theologies is not between these two, as every contemporary indication points to, but between the whole Judaic group of ideologie~ and religions -Communism, Liberalism, Christianity, Islam, and their parent, Judaism itself-and the Buddhaic group of philosophies and religions--post-Buddhaic, Hinduism, the Mahayana, and the Hinayana. He feels that it is the duty of the historian to bridge the gap between these two factions, impersonally and whole-heartedly. It is apparent that he becomes intolerent of the end of intoleration which he preaches.

He remarks that "most of the societies that embarked on the enterprise of civilization so far, have started life on the political plane, as mosaics of parochial states." He then traces the worship of man through an idolization of this state, the parochial community, and thence the idolization of a universal, ecumenical community, which is literally an empire by comparison. As a culmination of the man-worship of the agesprogressing, the idolization turns to that of ''the self-sufficient philosopher."

It is here that Toynbee makes a rather weak statement: he maintains that these idologies do not allow for human suffering and thus paved the way for higher religions. He alternately confutes and asserts the right of assertion of peasantic theory. An educated man, he is clearly overly biased, which causes him to retrace his steps and smooth a statement he has just made.

When he calls for separation of the essentials from the non-essentials, it is assumed he is speaking of theology. But how does he suggest this if his affirmed motive, as an individual and not as an historian, is to spread the conception of theologically flexible monotheism about a civilized world?

In theorizing through several chapters, Toynee thinks in terms of relative simplicity, as far as logical philosophy is concerned, but he persuades his reader to enter the depths of his straited mental processes and glimpse what must be termed a cheater's view of his idealism.

After he has picked the mode into which he is happily versatile, he launches into a full-scale discussion of the finer points of higher religions. He takes his subject, in which he is flawlessly versed, through the birth of higher religions; the small intuitive effect that sovereignties had on them until the rise of idologies came in the form of the Roman Empire. He then describes the relaxation of the principal virtues of the theologies, whose notable offspring was the centuries old religion, Christianity, and the resumption of trivialistic worship; he traces the bickering of one group with another, of church with state, of state with state, and finally the cardinal victory of the church over the state, with its subsequent enforcement of a doctrinal dedication.

Thus he quickly rushes up to the idolization of the religious institutions of and by which theoretists managed to outwit the political rationalists in the struggle for suprem~ power over mankind. Too quickly he convinces us that her victory for service was good. He considered his subject to have reached the level at which western civilization began to take its toll of idolized religious fascism, and embarks upon his golden chariot to lead the hunt for the defects in western civilization.

He warns, didactically, that religious fanaticism was reaching a dangerous peak, from which the only road led to chaos. He finds in the seventh century, the feeling that something was amiss. It certainly was. But as we are assumed to be familiar with the seventeenth century, he makes no further mention of the "amiss." Here Toynbee assumes a conservatism that is inconsistent with his thinking.

In discussing western Christianity versus western Imperialism, he achieves his aim impartially and succesfully.

Traveling faster, as the era of secular prominence opens a wider schism, he brings to light the scientific rationalism which free thought had given impetus to, itself bordering on pure sectarianism and touched with mottled atheism.

As though a race run for crucial stakes were on, Toynbee hurries through the twentieth century concept on a worldwide plane, then concludes his momentous work.

He steers back to the injection of man's self-centeredness; which the culmination of is the goal of every free-thinking individual who is a professor of any faith which lays down certain standards of good and blasphemes evil in its entirety.

In the overall effect of the book, and it is certainly long overdue on the library shelves of every university and private library, I think that it is in substance very worthwhile and encouraging, especially in its view toward free-thought among Christians.

I say there is no fault with the writer, or with his style; however, I do fail to see the separation that is claimed between the personification of an individualist's view and the claimed expression of an impartial evaluationist's view.

I recommend this book for those Christians who want provocative material illustrating new concepts in Christian thought, but there is no use for it as an instruction guide for the unsettled faithful.

Reviewed by JOHN DOUGLAS OGILVIE '58

Editor's Note: Professor Toynbee, officially retired in 1955 as Director of Studies at the Royal Institute of International Affairs and Research Professor of International History in the University of London, is scheduled to a-ppear on the University campus during the coming year.

Colla Wilson, The Outsider, Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Co., 19:16, pp. !28.

In many respects, The Ou1sider has proven to be one of the most controversial books on the best-seller list. It is a provocative blend of philosophic inquiry and literary criticism, that captures the intelligent perception of a writer who looks

with troubled eyes into a bizarre and tragic age. Bounded by the technological spirit of the century, and the automatons which power has made of civilization, The Outsider becomes the "hole-in-corner man". Deprived of understanding, revolted and frightened by the insensitiveness of modern man, these modern philosophers become an individual cult, outside the society of their contemporaries. "Wilson has imposed his own lonely discipline on that rebellious assembly of genius in an infinity of disguises." He has made a colossal attempt to depict this invisible man, tucked into his narrow room by the antics of robots, the outsider who "sees too deep and too much, and in this vision he finds Truth, which is chaos."

By plucking from literature a bristling battery of characters and quotations, Colin Wilson has attempted to protray his bitterly cynical Her<r-a man "compounded of many simples." Marshalled without a trace of pedantry, this twenty-four year old genius walks boldly in front of an imposing list of studies: the fact that he is, to all appearances, familiar with Barbusse, H. G. Wells, James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, Nijinsky, Van Gogh, T. E. Lawrence, G. B. Shaw, Hemingway, Schiller, Proust, Goethe, and a host of others is a staggering accomplishment in itself. Coupled with his unique concept of the Outsider, he proves that he is more than a brilliant biographer. He uses, almost without exception, men whose creative ideas have plunged them into an abyss of outsiders who have become unfit for ordinary life by the fact that they refuse to blind themselves to the dramatic reality of living. To prove his theory, he has impressed an almost universal archetype. According to the dust-jacket, The Outsider is "an inquiry into the nature of the siclmess of mankind in the mid-twentieth century."

Why then has Mr. Wilson used such an eclectic representation? It is almost certain that he has made a genuinely intricate study of this host of creative artists, many of whom are completely new to us. It is also possible that he is a philosophical fraud. Certainly he is guilty of a glaring error in reviewing Albert Camus' The Stranger. His assumption that Meursault's murder of the Arab is committed in selfdefense may be disproved by an analysis of the scene, and by the condemned man's thoughts during the interrogation.

Camus makes the very distinct and unmistakable statement: "The heat . . . seemed to be bursting through the skin. . . Then everything began to reel before my eyes, a fiery gust came from the sea, and a great sheet of flame poured down through the rift. Every nerve in my body was a steel spring, and my grip closed on the revolver." There can be little doubt as to the outcome; in the same manner there can be no reasonable doubt that the murder did not occur as a defensive measure.

The fact that he has made the cult of the Outsider and the Insider (which he calls the "other-directed" and the "inner-directed") into dinner-table talk is proof of his magnetic genius. The book is a depressing, pessimistic study on the blindness of man. Chosen from a twentiethcentury creed of 'anti-life' the outsiders of Wilson's books are men "in the country of the blind, where the one-eyed . man is king." Their occupational disease is more than a defeatist cult; it is a sickness of its own. It is from such a sick, diseased world that Colin Wilson draws his answer. Paradoxically, his solution is one we hear every Sunday. Christ taught it, Buddha contemplated its meaning, Dante, Shakespeare, Keats felt it. But there is a difference between the past and the present. These old Outsiders had a religion; the modern Outsider does not. The resolution of the problem, like the suicide of Nijinsky and Van Gogh, the radicalism of Nietzsche, the "visionary" faculty of Blake, or the corrupt world of Fox, is never satisfactorily answered until man finds some peace within himself. It is what Eliot (and the Eastern mystics) call "Shantih." It is what Wilson prescribes, a rock on which to anchor as he faces chaos. No one seems to know what the new religion will be; perhaps it will be a religion of humility, like the old, which will teach these modern outsiders that life is an universal yardstick by which we measure our value to the human race.

-Reviewed by KENT DARLING And MARY ELIZABETH HIX '57

Recently, one of the downtown theaters of Richmond featured a movie based on Irving Stone's semi-biographical sketch of one of the foremost artists of the 19th century. Vincent van Gogh, as a leader of post-Impressionism, has lived, painted, and died-and not many of the people of the capital (of the Old Dominion) were much inspired to see the artist's life portrayed on the screen, or to benefit themselves by being able to get a full-scale view of many of the original masterpieces, courtesy of cinemascope, museums, and art dealers. In brief, "Lust for Life" played at one theater here for a single week, whereas its success in New York, for example, has not dwindled for the past six week ... Could we dare compare the contrasting situations of Richmond, Virginia and New York city with the similar one which exists between the United States and Europe?

Without a doubt, the most persistent accusation directed towards us is towards our culture. The European has a tendency to consider the American culturally inferior. Yet, we argue, spurred on by our dependence upon the external material indications of artistic patronage, doesn't America have the best symphonic orchestras, the richest museums, the largest libraries? Yes, we have our Lee theater-goers and our museum members in Richmond, but who, outside of a few in this nation, realize that art is a creative processthat there is a definite distinction to be made between creative and interpretive artists. The above accusation is not a novel one, nor should it any longer shock the reader. I have heard it from Frenchmen, Germans, Hungarians, Italians -probably the most recent (though certainly quite fair) objection of much authoritative import comes from Pulitzer Prize winner, Gian-Carlo Menotti, an inhabitant of New York. for twenty years: "Americans have always concerned themselves more with the possession and display of art rather than with the production of it." In this respect, the average American does not consider the creative individual as being an asset to the community; it is unmanly, indeed unAmerican,

if one's choice is to take up music, writing, or painting. No wonder it is, then, that the young American artist seeks out Europe as his "spiritual home." It is, fortunately or unfortunately, a businessman's America, an America of judges consisting of "financial acrobats."

Our general interests of today seem to be directed more towards Presley (the Gotterdameron of the hep-cats), what Louella P. says about Truth and Love, what love-stricken doll Mary Worth will aid next, and what success Bob Hope had in entertaining the Royal Family. And, as Emerson stated, "The fine arts have nothing casual, but spring from the instincts of the notions that created them." Undoubtedly, the indifference with which Americans view creative life enhances our future cultural doctrine. For, deep appreciation and a positive attitude towards creativeness are the forceful prerequisites which we lack. And these cannot be bred overnight. Essential as they are for one's (Richmond's, the United States') cultural progress, these changes of attitude must be instilled in him from early childhood. The youth of the coming generations should reach adolescence with an ample understanding of those masterpieces which constitute the "classics" in any field of art. Inspiration and encouragement should then follow.

As it is now, I think our indifference is epitomized in too many different ways. Artists are rarely assigned to any responsible position, and seldom are they chosen as recipients of honorary degrees from outstanding colleges or universities. We seem to accept, without the basis of experience, tpat any seriously artistically inclined individual possesses not one iota of responsibility-that irresponsibility is synonymous with creativity. Rarely do we realize that creativeness demands strict discipline which must be imposed upon and by the artist himself.

This is not to state that I advocate a complete reversal of attitude. But with more outward expression of inward appreciation towards the artist, such encouragement should Produce less self-conscious composers, writers, painters. Perhaps we could then approach a fair rivalry for Europe from the cultural point of view.

-VIRGINIA HARRIS '58

Paris is made for lovers, she thought suddenly, and realized that tonight, at least, the old saying had come . true. It was not true as one saw it in advertisements, under slogans for French perfume, with a model in mink gently caressing the face of a continental gentleman sporting tails, both of them surrounded by bottles of champagne. Certainly she was not a model, for her figure was less than beautiful, and the Frenchman with her wore an Air Force uniform instead of black and white. And they were not surrounded by bottles of champagne, but instead confronted by two citronades, and she was not caressing his face. She sat rather still, rather stupidly drunk with the eyes and the mouth before her, the whole face run together in a blend of beauty so dazzling that the unbelievable happiness seemed not to be hers, rather someone else's.

His eyes were kind tonight, not dark with the unhappiness and desperation which had a first made her afraid of him. He looked, in fact, like a pleased small boy who has done something of which he is immensely proud. He was proud of having surprised her, she knew, but she could not yet know that he had been terribly afraid of seeing her, even after her letter which had said that she would be in Paris between August 4th and the 8th. His pride was that of a small boy's, too, and he had feared always that she would reject him as she had rejected him on the boat. He had followed her about insistently, worried that Americans were not accustomed to persistent demonstration, and that she would look at him scornfully. He had left her on the last morning on board, when she had to get off in Southampton. He was

returning to France after eighteen months in the United States on an exchange plan between jet fighter pilots. And he had to bid her goodbye among all the other milling passengers, in the gray dawn when both of them were too exhausted to speak coherently. She had never said that she loved him, and after the first mention of it, he had refrained from saying it, either. He had only had a look to remember, an expression of sudden regret, sudden passion, all tempered with terror that had begun the first time he had kissed her. He did not understand the terror, he had done nothing ungentlemanly, he had sought only to make her happy. But she had been afraid, and after that night, she had avoided him persistently. Then he returned to base after a short vacation in Brest; he had gone back to St. Dizier, and there had been a letter waiting for him, a sheet of paper that informed him of her whereabouts for the next month, including the statement that she would be leaving Italy for Paris on the third of August. He sighed now. He still knew no more than he had in the beginning. This girl said very little. She looked silently at him now, wondering how she could ever have been afraid of love, no matter on which side of the sea it belonged. The terror she had felt in the last few minutes with him weeks ago had been a kind to which she was not accustomed; she had in a moment been struck with the loss of him,_and it was like the ground giving way with no hope in the world of support. She had been drawn inexorably away by circumstance, too late she realized her own heart. She had been convinced that they were never to see one another again, but she was a determined person, and she haunted the French ship lines, asking for his address on their passenger list. They refused to give her any information, and at last, in desperation, slle postedan unaddressed letter to him through them, having first secured their promise that the address would be written on it, and the envelope would be sent to him. She had almost forgotten the letter after that, the possibility of its ever reaching him had seemed so thin. And then she had gotten off the bus from the railway station tonight, hot and dirty and tired. She had rounded the corner, stepped through the hotel door-and she had seen him immediately through a mist, standing at the desk. If she had known how to faint, she would have dropped to the floor. but she had never fainted

in her life; she simply took his arm, and walked out of the hotel with him, messy and sticky and uncombed though she was, while her friends stood openmouthed, watching. They had walked and looked at each other, and they had finally dropped down in this brightly-lighted and unglamorous place.

Her friends had warned her not to put him on a pedestal, that he would appear considerably less glamorous off the ship, that shipboard romances always held a touch of transient glory. It frightened her a little to realize that he was more beautiful to her than even that last desperate moment of goodby, that she had not been wrong. She was in love with this man, unwisely and without thought, but in love.

They walked together again, after the citronade was gone and they were tired of other people. They walked up on street, and then up another, and they turned a corner. She caught her breath in a joyful pain. Paris was spread out before them in a glow, or at least a bit of Paris, a lane dotted with street lamps and bordered by gardens. Nobody else was there. It seemed as if nobody had ever been there to love this part of Heaven. She stopped and turned to face him, knowing that she must say what had thudded in her heart for too long, knowing that the words were going to come spilling out relentlessly because she wanted them to.

"I love you," she said painfully. "I suppose I've always known it, but I didn't tell myself until I lost you. Then I knew that I loved you more than anything else, and I knew that if I saw you again I would have to tell you." She said it very slowly and simply so that he would understand. It was so dreadfully important for him to understand!

His kiss was cool and sweet, a lover's kiss. His mouth had never touched hers that way before, and she went limp with the sheer beauty of it, with the tenderness and gentle love that came from him.

"I love you," he told her, and he, too, said it calmly, without beating his breast in passion. It was as simple as that, and there was nothing that had been left unsaid. And he took her arm as they walked on, smiling at each other delightedly as if each had given the other a wonderful present which they had opened together. She found it an effort to look away from him, and she wanted to stop again and again to touch his face

with her fingertips, as if he were a dream to disappear when she awakened. His chin was darkly rough.

"When must you go back to St. Dizier?" she asked him, not fearfully, for she believed this night would never end.

"I must go tomorrow, early. I cannot be late." But he said it curtly, for he knew better than she the fleetness of time.

"Tomorrow? But that is so soon!" She found herself staring blankly at him.

"Yes, soon." He sighed deeply. "But I can stay here all night. We can stay here together until I have to go."

She looked at him fearfully. "Shan't I ever see you again after tonight?"

"I don't know. If you want to see me, you will see me."

He was unfathomable. What was he thinking? Did he want to see her again?

"My dear, I love you. I want to see you forever. I can't bear the thought of losing you."

"Oh I love you." He buried his dark head on her shoulder. "What shall we do? I don't know what to do. I must go back tomorrow, you must leave me in four days, you will go back to America and forget me."

Suddenly she understood the fear and the silence which had sometimes come between them, driving out the love because it was stronger. Fear is the most terrible thing in the world, she thought. We are afraid because we don't know how to do the extraordinary, and we feel strangely certain, that because it is the extraordinary, we will not succeed. Then she knew what she could say to him, to make him understand what they had both failed to see from the beginning.

"If we believe enough, we cannot fail." She kept her eyes looking directly into his, for he must see that she was right. "If we are afraid of loving each other because I am American and you are French, then I should go away from you now without saying even goodbye." His grip around her tightened, but she went on more slowly, hoping he could feel the strength she now held

"If we think of our own sacrifice, we are lost. Only if we work at this, and believe, and understand with the heart can we succeed. Are you strong enough?"

"I love you, I want you. Can you stay here with me?'' He looked despairing at her.

"No," she answered quietly. "But I can come back next summer, and then I can stay."

"You will never come back," he said bitterly.

"Not if you don't believe that I will."

He did not believe her, she saw in an instant. He would never believe her, probably because he had seen too many American girls who fell in love with other jet pilots, and who promised and extracted promises, and then went back to their own country and forgot. Strangely, she did not feel strengthened and noble at his lack of understanding, she was defeated by it. What if I am like those others, perhaps they meant what they said as urgently as I do now. Why did they forget? Will I, too, go away and never come back? If that is to be true, then I am being unfaithful this minute, trying to make this man believe in me and understand that I will never leave him. She was suddenly, unbelievably, shaken and afraid again. What am I doing here? Oh God, I wish I hadn't seen him here. We both could have gotten over it so much more painlessly. But they were there, and she was very tired, and she wanted to go back to the hotel.

He took her back willingly without a word of protest. He had hoped for so long, hoped as one does in daydreams with· out a real supposition that any of it will come true. Now that it all had been thrown in his lap, he was terribly frightened

and he could not allow himself to believe her because she was going away so soon, so very soon, and the future was too uncertain for him. He did not know where he would be sent next; there were rumors of Indochina, and he could not ask her to come back year after year and wait for him. He could not dare to ask her, because he did not want her to consent and then not come. He was afraid of that more than anything else. It was as if he could not bear to have his illusions shattered about her, to have the whole image spoiled.

They had reached the hotel before she realized that neither of them had said a word since they had been standing together on that dark street which, if she ever saw it again, she would recognize instantly because of the dark memories which would rise from its pavements. There were no plans for the next morning before he would leave. Perhaps this was goodbye. Well, then, she could at least tell him goodbye with dignity.

"I'm sorry," she told him uselessly. "Goodbye. Adieu." She did not know that the French interpretation of 'adieu' is 'goodbye forever,' until the grave. She turned away from him and went inside, leaving him rigid with despair on the street outside. I will never see her again, he thought. She meant that she never wanted me again, that she doesn't need me at all. The thought made him choke, and he argued unreasonably with himself. But I don't want her to go away. For the first time in his adult life, he felt a strange mist sting his eyes, and the hotel wavered in front of him. I don't want to lose her, he repeated. I wish we had not been taught to accept defeat, he thought hopelessly, I wish we had been taught to fight until we got what we wanted. But if she doesn't want me, I don't want to bother her and make her unhappy by following her. That isn't the way to fight. ·

He saw himself standing there in the street stupidly, and With an effort he peered through the door, faintly hopeful that she would be standing there, waiting, and that they would go out and begin all over again. But she was not there, and the hope died reluctantly; he turned away, retracing his steps blindly, uncaring. He walked all night through the silent streets, feeling no weariness in his legs, for the pain in his heart blotted out everything else. Once he stepped unseeing off a curb, twisting his left ankle painfully, but after the

first momentary shock he forgot it, and went on without a limp. He was amazed to see the sun begin to come up, and realize that the gray shadows were lifting from the streets. He had not realized it was almost time for him to return to his hotel and prepare to return to the base. Suddenly he was unbearably weary, his legs refused to move anymore, and he wondered dazedly if he would be able to get up and go on. He did not know where he was, for he had lived in Brest all his life, and was as unfamiliar with Paris as any foreigner. This realization, perhaps above everything else, discouraged him utterly, and he buried his dark-bearded face in his hands, wondering for a moment why his ankle had begun to ache horribly after all this time. Hardly conscious of his surround• ings, he sank down on the bare pavement, his back resting against the stone wall of a building, and slept.

The gendarme found him not an hour later, and, mistaking the young flyer for a drunken boy who had been unable to find his way home, gave him a sharp kick in the ribs which shocked him into painful consciousness.

"Would you perhaps like to stay here forever?" the man inquired of him, his tone heavily punctuated with sarcasm, and he looked at the gendarme and thought ironically, Yes, I should like to stay here forever, to sleep here blessedly, and never wake again. But he turned obediently, and rose, and shambled off in another direction. . . .

The telephone rang imperiously in her room at seven thirty, and, even in her sleep she heard it distinctly, and was out of bed in one swift leap.

"I came back," he sounded drugged. "I had to come back."

"Where are you? Where have you been? Wait a minute, are you here at the hotel?"

"Yes. Here. At the hotel." Every word was an effort. "I must go to my train."

"Don't leave! I'm coming. Now! Wait for me!" She was frantic. He must not leave.

"Yes. I wait."

She threw on anything. What she wore, how she looked the last time she saw him was not important. She was at the desk in five minutes, taking him by the hand, pulling him

outside where the world could not listen curiously.

"Oh. You look so tired," she cried, pitying.

"Yes. I have walked. All night. I am tired. Look, I fell off a street curb." He tried to laugh, showing her the ankle which had swelled noticeably.

Oh God, she thought, tell me what to say. I can't do this alone.

"Can you walk on it? Let's go a little bit away from here."

He came patiently after her like a dog on a leash, and his eyes were blindly loving like a dog's.

She stared at him in despair, and her mind raced. What shall I do? How shall I say anything? Shall I hurt him deliberately now, or ease this farewell off as best I can, and Wait until we both can forget with time? But she could not kick a beaten man, she could not make him suffer now anymore, he had been through enough.

"Come over here and sit down on the bench with me. I want to talk to you," she offered. She began to speak, choosing her words carefully. "Dear, I have not been sleeping much, either. I think we must try this winter to write each

other, to try to know each other better. I can come back next summer. I have a very understanding mother, and I know that she will let me come back, perhaps she will even want to come with me. Would you like that?"

He stared at her blankly, and she realized that he had not taken in a word. She took his face between her palms.

"I love you," she said to him until the blind look was gone and he was listening to her. "I love you, and I must go away for a while, but I will come back, I will come back. Do you understand that?"

"Yes. I understand-that. You will come back to me?" He looked at her trustingly, anxiously, like a child who wants to be loved by a parent.

"I love you." She could not promise and live a lie. He relaxed. He seemed satisfied that she would return if she loved him. It was time for him to go, she knew, and she stood up, and hailed a taxi for him.

"You must not miss your train, dearest," she told him gently. "Here's a taxi for you to take you to the station. We must say goodbye for a while, now."

"Write to me," he pleaded, and then he kissed her good• bye. She kissed him back with love because he wanted her to so much, and because she still loved him. Then he got into the taxi and closed the door. In a moment he was out of sight He did not look back, and she felt almost a curious disappointment.

She waved until the car was out of sigh~ and when it was gone with only a cloud ot dust to remind her that it had been there at all, she stood where she was. She felt drained of energy, and she realized for the first time in her life how difficult it was to deal with other human being's emotions. How small I was, the shame overcame her, to act on im· pulse, and to play with love on short notice, knowing, I think, that I could not really be hurt by ·it. I think I have hurt someone unbearably. I must write him right away; it will give him something. A year is a long time. Perhaps we both will forget easily, perhaps not. And then, perhaps I shall come back here next year. The thought was strangely comforting, and she carried it with her as she returned alone to the hotel.

The sunlight touched slightly the grassy sides of the lake. Among the light, green grass I could see the golden reflections of light. The clear water looked cold, even from a distance, and thin sheets of ice covered parts of its surface. On the other side there were white ducks swimming on the water, and some were scattered on the small half-island which extended into the water.

The silent lake went on as usual and no one paid any attention. Now and then one or two ducks cried out. telling

their companions that they were there. Beyond the sides of the lake there was a path covered with dried leaves, and tall trees rustled slightly in the calm breeze. Some pines, still bearing coats of green, looked proud. Through bare branches the light, blue sky could be seen.

I combed the grounds in search of a place to sit and rest, but tiny stones and the dampness of the soil thwarted me in my search. I still remained there, breathing the deep, fresh air. I picked a stone from the ground and threw it into the water. When the stone struck the water, the ducks moved back toward land, but a few minutes later they moved back into their happy circle.

On the left as I turned, I saw a beautiful building with a pink, brick bell-tower. The sunlight slanting off the tower, created a long shadow upon the lake's surface. In front of the building I could see a thick, dusty cloud of smoke caused by the wheels of cars running through the sandy road, and as the smoke moved slowly toward the top of the tower, I could see the rays of sunlight shining through the smoke. A red-coated girl carrying her class books appeared briefly in the haze, walked toward the building, and vanished into the building.

I could see further away a tall chimney, pouring out black smoke that rose rapidly into the air. The smoke looked busy and hurried, but it did not affect the peacefulness of the surroundings. A bird sprang from a tree and flew from a tree and flew across the lake, lighting there in another tree. A slight, cold wind then struck my face and I forgot all of the things I had been watching. I would have liked to stay there as long as I could. A bell in the tower rang out a few chimes, and I knew it was time to leave.

-YEU

(Continued from Page 18)

to speak to Dr. Sutton. Then she was shaking his hand and saying how she loved his sermon-that was a good way to begin, she thought-"You have such a wonderful way of speaking right to my heart, Dr. Sutton-and he was saying "Thank you so much, Mrs. Saughter, thank you so much"and "Now about the drapes in the church parlor, Dr. Sutton" -and he said "Thank you so much, Mrs. Slaughter-for the drapes-they are a beautiful addition to the parlor-I'm so happy you were on the selection committee' --and she said, "But--" and realized he wasn't shaking her hand any more -he wasn't looking at her even-he was shaking some man's hand hard and saying "It's been years, Bob-how wonderful you're in Bayersville--you've got to see my wife--tell you what-you'll have to come home to dinner-this is too good to be true" . . . not noticing Emma at all any more, though she kept standing there-but he still wouldn't look-and finally she started walking away, out of the church, not to come back again until Sunday night-and she remembered she still had her choir robe on, still covering up her new lavendar silk. She took it off then, back in the choir room and put on her last year's straw with the purple bow-and everybody else had gone--there was nobody to tell, nobody at all.

-ROSALIND ALLEN '57

Although "Scrapbook" is one of his first contributions, Anthony Nixon has spent his last two years in Richmond College as a member of The Messenger Staff. With both high school and college experience, Sam will probably continue in journalism after his graduation in June, 1957.

John Ogilvie, a junior at Richmond College, is making his first appearance in The . Messenger with his review of Toyn. bee's newest book, An Historian's AP'J)Toach to Religion. Editor of Frat Chat, President of Philologian Literary Society, and a major in English, John plans to continue writing both serious fiction and poetry.

Both Wendy Kalman and Ann Clark, juniors at Westhampton, appear for the first time in this issue. Ann is a member of The Messenger staff, and an English major. Wendy, a transfer from William and Mary, heads this issue with her short story, "Life, Death, and Then Some."

Rosalind Allen is a consistent contributor to The Mes• senger. President of Mortar Board and a major in English, Rosie plans to attend graduate school after receiving her degree in June.

A transfer from Hollins College, Kent Darling is com· pleting her senior year at Westhampton. She has appeared in previous issues, this time as author of "A Love Story," and co-reviewer of The Outside.

Both Ann Hunter and Margaret Logan Ball have had considerable experience in the writing of poetry and prose. Ann has published in national poetry magazines, and Mar• garet has worked on this staff for four years. They appear in the Folio of Poetry, Ann as author of "Eloise From Her Convent," and "Words For Ulysses," and Margaret as author of "Chamber Music for the Twentieth Century."

Virginia Harris, author of the essay "Why No Lust For Art?" has spent only one year at Westhampton. A junior this year, she transferred from Oberlin in February, 1956, and since then has planned a major in English. 50

Betsy Minor and Barbara Matthews are both members of the University Players. Betsy has appeared in past issues, this time as author of the comical magnum opus "A Southern Symphony." Barbara is introduced in The Messenger with her first poem, "I walked through all infinity."

A member of the freshman class, and representative to College Government, Sally Finch makes her debut in The Messenger with her lucid review of Rebecca West's latest novel, The Fountain Over-ftows.

Coming from Hong Kong, China, Yeu Chor Chan, a sophomore at Richmond College, is working toward a major in chemistry. Although he plans to be a physicist, Chan is interested in literature, particularly the short story and poetry. "A View of the Lake," concluding this issue, is his first publication in English.