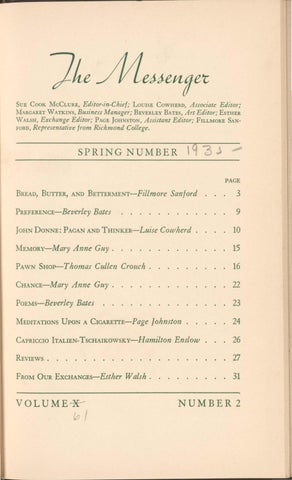

SuE CooK McCLURE, Editor-in-Chief; LouisE CowHERD, Associate Editor; MARGARET WATKINS, Business Manager; BEVERLEY BATES, Art Editor; EsTHER WALSH, Exchange Editor; PAGE JOHNSTON, Assistant Editor; FILLMORE SAN· FORD, Representative from Richmond College.

BY FILLMORE SANFORD

THIS business of being a college senior is most engrossing. Indeed it is so engrossing that most college seniors are too busy being college seniors to allow any concern for the future to play more than a minor role on the stage of diurnal undergraduate thought. But it is a fact-an inexorable fact-that in June this University will make its proportionate contribution to that vast swarm of more or less sweet young graduates turned from the protection of class and club and cloister into the cold milieu of a money-mad world. It is a disquiteing thought that ere long the pleasant consideration of proms and dances and lessons and lectures must give way to serious and practical concern for jobs and salaries-and possibly meals.

Commencement time is a trying time. Our liberal arts graduates are suddenly slapped in their optimistic faces by the necessity of making a practical livelihood. Those seniors who shall have by that time girt themselves with sufficient credits and quality credits to stay the hand of the grim reaper in the Dean's office shall leave college walls poorly equipped for the pull and haul existence of business competition. Most of them are prepared for no specific vocation, not even teaching. They will have learned no specificgroup of facts. They will have mastered no one body of knowledge. They will find that the sheepskin, even if formidably illegible to the business executive, is no longer a symbol of achievement. It has come to be no more than a nicely engraved affidavit that the holder thereof has spent four years in the softening atmosphere of undergraduate extravagance.

The college man, soon to grapple with the world of hard practicality, often finds himself questioning the 3

wisdom of having spent four years in seeking this chalice of enlightenment. His education appears of slight consequence in his efforts to land a job. He finds that the collegiate standards of worth and those of the economic world are at diametrical variance. The University professors extol the virtues and value of the broad fullness of life. The practical man of the world .attacks all undergraduate vagary as a waste of time, and sees higher education as excess baggage in the desert travels of modern life. The hopeful neargraduate is given to wondering whether this college life were not a mere pleasant idyllic interval rather than a constructive training.

As he peers over college walls into the world beyond, he sees a bustling, materialistic way of life. He notes the effects of the prevailing capitalistic ideology-the ideology that places creature comforts and cumulative capital ahead of the human qualities and cultural values which the university has taught him to know and respect. Most college seniors, of course, give little thought to the future, either philosophically or practically, until the last few months of the final year have begun to slip by with their wonted rapidity. Many do not think even then. They do not think about anything. They make passing grades, maintain an acceptable social batting average, have a good time, and hope for the best. Other seniors, gripped by an early materialistic conditioning, worry only about the fact of getting some sort of good substantial living. They come through college keeping "practical application" as a watchword, hitting the high spots, and taking only those courses that will directly assist in the landing of some sort-any sort-of job. But there are a number of seniorssalt of the collegiate earth-who have felt the spark of intellectual curiosity, who know the thrill of seeking truth for truth's sake, who like art for the sake of art, who earnest!y seek a broadness of outlook, a richness of personality, a 4

firmness of character, who are concerned with making lives rather than livelihood.

It is this type of man who revolts at the thought of having to enter unreservedly into the whirling mill-race of money-making, after having once known the calmer, richer channels of a university education. He looks in the mouth of this gift horse of capitalistic tradition-and is dissatisfied.

Since the Industrial Revolution there has been a growing emphasis on the material side of man's existence. The technological progress of civilization has been accompanied by an elevation of the dollar mark as a symbol of success and prestige. In our country the Puritans echoed and enhanced this tendency by preaching diligence and honesty, by elevating thrift and economic acumen.

"Sloth is evil. Apply thyself diligently for the glory of God. Save. For when you destroy a crown you destroy all it might produce." Ben Franklin reflected this growing materialistic ideology in his saws-"Time is money. A penny saved is a penny earned. Early to bed, early to rise ... " This group of stereotypes are shibboleths in our modern existence. Accumulation of wealth has become the chief end of man. Money is the root of all good. The rich man is our paragon of excellence.

In this life of driving for dollars, where even time is made a function of money, the tendency is to make our colleges into machine lathes for turning off sharpwitted, polished vocational technicians. Materialistic iconoclasts would revamp the whole educational set-up, putting all the emphasis on the practical, pragmatic side. The broadening of the mind would be replaced by the thickening of the pocketbook, the swelling of production.

It would seem natural and apropos that the college man should take his position on the cultural end of this argumentative see-saw-in self-defense, if nothing else-and 5

stand up for the principles of his university. In spite of this alleged "intellectual measles" and the scorned autointoxication of idealism, his outlook might be worth some consideration.

The college-bred man is impressed that we are infinite! y more than economic men. We are thinking, creative, artistic, religious creatures, with unlimited capacities for enjoyment and happiness. Man does not live by bread alone. Any way of life, and most certainly any educational system, that takes into account only the protoplasmic and materialistic side of man is radically unjust and myopic.

The big guns of business-the makers of millions and civic club speeches-decry the yearly turning out of college graduates who are no better than numbskull neophytes in the practical world. These young hopefuls, says the shogun, because they hold college degrees, think the world owes them a living and immediate applause as they start to climb from an humble bottom to an elevated top in a few short, romantic months. They look upon the diploma as a passport up the ladder to success. 'Twere better that these youngsters spend their four years learning the fundamentals of some business instead of living leisure!y off checks from home and learning a bunch of fool ideas that aren't worth a tinker's damn in later life. Culture doesn't give one a roof over one's head and a balance in the bank. A man must have a good comfortable life, he says. Yes. But what about a comfortable good life?

The thinking college man is not so wrapped up in the halcyon-tinted undergraduate life that he doesn't realize what he is going to face after graduation. He knows full well that the great American myth is no more-the myth that tells of the romantic rise of the deserving from logcabin to the White House. He knows that he will have to earn what he gets and that he will have to face many in-

equalities and injustices. He knows that he will have to go at the thing tooth and nail if he wants to come out near the monetary top.

He realizes this. But still he is unprepared for the battle of dollars because during his college days he has concerned himself primarily, as the authorities intend he should, with the less material and more permanent side of his naturethe side that rises above wage-earning ability, transcends the dollar mark. He experiences the sheer joy of living. He is in the process of laying a foundational sense of cultural, intellectual, emotional values. He is sounding the bedrock of his character, building a sea-wall against the coming tides of life. He thinks of living the good life. He studies because studying is a good in itself. He reads and thinks because he wants a broader outlook on life. He makes social contacts because he wants to know himself and other men. He desires that his mind be not forever stifled in a downtown office.

Not that a college man fears work. He does not. But he does not want to be a slave to practical things. He wants to be his own man. He fears the profit-motive maelstrom that directs every mental process toward monetary success. If a man is to succeeed today-and Americans must succeed -he must let nothing divert him from his goal. There is no place for wayward consideration of life's non-essential. Bread comes before betterment, dollars before duty, income before ideals.

The mind of the successful business man must be stripped down to a streamline machine for making money. The accessoriesof artistic interest, religious activities, constructive reading or writing must be secondary. His art is the art of the profit maker. His religion is obeisance to the almighty dollar. His reading is of business journals. His writing is done in figures. He concerns himself with his own private 7

goods and chattels, giving infrequent thought to that part of him that is divorced from his acquisitiveness.

Such men go barging and blundering through the china shop of life like the hungry Newfoundland, lacking all the sharp eared awareness of the terrier or the fine sensitivity of the spaniel. Life, if not unsuccessful and not dyspeptic, is an affair of busy, blustering bluntness. The world is one of deals and dollars, bills and budgets. Occassionally there is time for participation in a few concentrated, high-tension pleasures. But the verve for acquisition demands a speedy return to diligent application.

This is not life. It is only partial. It was Thomas Carlyle who called man a swine. This may not be wholly true. But his stomach is often more imperious than his soul.

Where the college man is thrust into the swim of practical life he finds that he must swim for all he is worth-or drown. His faculties are so engrossed with the necessity of making a bread-and-circus living that he can be encumbered with no extras. The college bred wideness of interest must be shed like swaddling clothes in the thing-ful but empty life.

Vocation is important. Our University and university students recognize that it is important. But it must not be placed at the very peak of our pyramid of values. It must not exercise such a hard-handed hegemony, such a stultifying tyranny over all other phases of human life.

Our educational system does not intend to make life a glorified sheep walk. The attempt is not to have all mankind, wrapped collectively in sack-cloth and ashes, spend its collective time in trailing raptly through art galleries, or poring over the classics,or musing over poetry, or perennially indulging in esoteric philosophical cogitations while the cobwebs settle on the wheels of industry and the milkweeds thrive in the grain fields. Life cannot be one long

shaded avenue of cultural bliss. But the gown should exert its influence to direct life away from the material go-gettism, the bustling Babbittism, the eternal emphasis on immediate practical results. It should stress culture for the sake of culture and knowledge for its own sweet savor.

Our universities seek not to produce a yearly harvest of bespectacled, anemic intellectuals, a flock of impractical dreamers. But they revolt at the graduation of a flock of tough minded wage earners. The aim is for the fuller life. The emphasis is not on technical efficiency, but upon individual and collective happiness-happiness based not upon bread and butter alone.

The college graduate can do no more than rant at existing conditions. He must seek a subsistence. Whether or not he can live also depends on how thoroughly he can emancipate himself from the "time is money" idea.

So long as our American life embraces the gold standard, the odds are against him. But he can-and must-steer his ship of life by an idealistic compass. If his destination be the Never, Never Land, no matter. We live in the striving.

Pteteteuce

BY BEVERLEY BATES

I'd rather feel the bitterest cold Than never feel at all, And as for knowing, I'd rather wander down a one-way street Than never leave the little hole Life found me in; And what is morel' d rather find one locked and barred Than never knock upon a door.

BY LUISE COWHERD

JOHN Donne was, first of all, and above all, an artist. He was, moreover, a philosopher, a psychologist, a nonconformist, a craver of candor, a recusant, a fluctuant, an idealist, an extremist, a moralist, a poet, a preacher, and a thinker. We are concerned here with the thinker; but the thinker may not be separated from the others lest he lose his identity, his significance. The man and his art are inseparable.

Those in each generation who seek a new sense of beauty, of pain, are thinkers; and as such they are ignorers of all unable to fit themselves to a growing age; in turn, they are ignored, made a butt for a time, and, in their struggle, they take on a ruthless emotional attitude which is accompanied, very often, by violence. It is so with Donne, "the satyr trampling on a bed of flowers."

In his early life, the circumstances and the environment hedging him aboutwere responsible for the wildness which came out from his already precocious mind into bursting force against every oppression. The child of a thwarted, frustrated family bcame the lampooner, first of London life, which he synchronized into his mental violence and made him satires, then, later, of women on whom he exercised his physical violence, and made him lyrics. These utterances were full of shrewd expression and much evidence of thought that could detach itself only so far from the man that, as yet, had neither poise of body nor of mind: "he is the prey of lusts that drive him hither and thither. His very moralizing is spasmodic. Pity chokes his spleen, and blind fury blends his reason, and in his 'raucous maw, Rankly digested' truth and faded falsehood mingle." But his aim was intransigeant and not a littl~ stubborn.

Hence in the evolution of this thinker, it was the period of his heart's direct assault, the prelude of bafHing searches, which gave him later much to regret, but which probed his brain and heightened it with unrest until, from where he least expected, should rise the answer that sent his soul sermonizing loudly to its peace.

In the struggle, in the heat of the first young fires, in the constant quest, the Donne genius ranged every scale of experience and upon each "struck some note, harsh, cunning, arrogant, or poignant, which lingers down the roof of time" into the sonnets of Millay, into the essence of a modern novel1-

The r:~ftersof my body, bone, Being still with you, the muscle, sinew, and veine Which tile this house, will come againe,and, in general, into our own growing consciousnessof new meanings and use of words. We can read Spender and gain the same reaction to his intensity of attack as from these lines of Donne's:

On a huge hill

Cragged and steep, truth stands, and he that will Reach her, about and about must go, And what th' hill's suddenness resists, sin so, Yet strive so, that before age, death's twilight, My soul rest, for none can work in that night.

No more than we wish to console our present connotation of "Truth" with its passive synonym - "Beauty" - did Donne wish to console his full-blooded thought to the sweetness of his age. It is true that his intoxication with life came also to other men of the Renaissance who, with him, set up anew the body to be artistically adored: but his intoxication was realistic. Because of this realism, his attitude, though passionate of origin, was never one of fear or false reverence. Out of his experience his intellect served in its

1 Look Homeward, Angel.

11

turn the physical with complete candour and the spiritual without sentimentality; it taught him to preserve a singular perspective:

What Anatomist ~nows the body of men thoroughly, Or what casuist the soul?

Thus would the "anatomizer" always learn, thus would he always find the consecutive movements of harmony in each step "from the riotous valley of physical indulgence" and stringing them together "up the tortuous hill of intellectual questioning," so great was his exultation that he stopped, now and then, "where imagination may spread its wings."

One of the most beautiful times of his life, yet one of the bitterest, is the single instant when his positive spirit lay at Anne's feet and its eyes hung humbly under the shadow of her original charm. His wife was a rest to him on the hillside, an instigator of the inter-assurance of his mind. He taught himself from his experiences. His art and his thought, he interwove.

Many scholars speak of the keynote of the Doctor's life as intensity. On this intensity, which stood out in his critical writings as "bitings", his enemies could get a hold; but his wisdom matured, the taper in him burned eternally as a vestal-watched fire, his "emaciated body" died its studied death having a free tongue. (A minister said once to Brieux about his Les Avaries that when a thing needs saying a man is in due course inspired to say it, and such inspiration gives him a right to be heard.) Most certainly Donne had every worldly inducement to refrain from writing or speaking as he did and no motive for disregarding these inducements except the motive that is inherently the power of the intensified of mind and the motive that bid a crown say, "Come. Here is St. Paul's! " 2

2 1n 1621 King James appointed Donne Dean of St. Paul ' s.

Donne never lived prudently. He struck through the appearances of men and things, beyond illusions, to a real profundity. At Oxford, he adopted the esoteric cults which ministered to his mysticism. At Cambridge, where his Gothic strain in temperament met with less sympathy, he chartered his experiences to his casuistry, enhancing his rationalism. At Lincoln's Inn-so unlike many of our universities-he was "shielded from the importunities" of life. Here, like an apothecary, he surrendered himself to his growing ideas which, because of the deep consideration he expended upon them, tended to last-to remain an integral part of his close ingenious logic.

It is evident, then, that the prelude years made Donne competent later, as a theologian, to "report adequately of the soul." The essence of his sermons, like the firmness of caryatid thighs, appears distinctly through the soft folds of a (literary) drape; and, for the most part, their content is as substantial as their beauty. When we read them and think that for two hours the Dean could roar over the heads at St. Paul's maintaining a high level of rhetorical excellence, keeping each sentence and each paragraph flowing into the other without effort, concentrated and full, in weighty harmony to the climax, we feel, by a sort of steadily increasing exultation, lifted up to the level of understanding that which is ordinarily beyond. Nowhere is he irrating. Nowhere does he impose upon us a backward movement.

Whether or not we agree that Donne owes his fame as a preacher to his power as a sensualist, whether he owes his sermons to his lyrics, whether he owes his fear of death to a love of the body, is a matter of no importance. It is important that he was a man of thought, howsoever it developed. We may blame him for much. But we must be careful that we do not give out a too-limited judgment. If we dislike his mutinous temper, we must, nevertheless, 13

recognize that it drove him to the high seas with the Earl of Essex and thereby scored for him unquestionable advantages.3 We certainly cannot condemn his seeking unconventional opiates when there was in him the unconventional to be satisfied. We would do it ourselves if only to preserve our sanity. And John Donne was both experienced enough and clever enough to take from circumstance what he wanted without giving too much in return. The loss of youth and virginity to him were nothing so long as he did not permit to be taken of his intellectual and spiritual strength more than the experiences were worth to him. The artist wished to work: and, since he wished to write, he put h1s energies into it. He vehemently desired to speak out his fire-words in an effort to dispel his loneliness, to satisfy the impetus that bounded his intelligent curosity. He ran the entire gamut of puerile extravagances like a strange wild thing; his nervous thought was loosened, thus, from tension, as were his sensitive lips, and the desire that sometimes must have come into his face when he saw the inescapable directness of a lady's appeal as he passed along in his chair.

Finally, the Pagan came to lean toward the church and the godly. Why? Because he was called upon, and, perhaps, because circumstance had been a little cruel, and because he had not yet found what he sought. It may be, he had discovered that the less he yielded to the ephemeral pleasure of physicality, the stronger he became, the more energy he had for other things, the more for his work, the more in which to solve the still clinging interrogations, the more for his friends who were friends without reservations, which his mistresseswere not.

Donne, emerging from the madness of his paganism (which reminds us of Van Gogh's paintings and their mad-

3 Court preferment came, was for a time one of the chief causes which kept him outside the church, and became a disappointment-the goad which drove him within it to the penitent, the puritan, away from the pagan.

ness), may have been almost afraid of what his life would be in the church-the high new emotional quality of it; but he came to see that for him life had no meaning without the Divine. At last, he was saved from ecstatic insanity. He came to see his terror had been shame, had been also misunderstanding. He no longer imprisoned himself unconsciously in what he created. His thinking had set him apart first as "the rose" and then as "the yew" of the Renascence.

BY MARY ANNE GUY

Were tears like raindrops, My heart would be a lush, ripe thing Memories smooth-washed into the soil Richer for a new flowering.

But on the monument of my heart, Sepulchered forever in one image dearer, The hot, eroding, uneffacing tears Have but marked that image sharper, clearer.

BY THOMAS CULLEN CROUCH

F1vE o'clock.

Cortlandt Street quickened with the vigor of the afternoon rush. The rattle and roar of the traffic swelled with the cries of bumptious news-boys vending the evening editions of the Herald, Tribune, Sun, and Lord knows what other manifestations of the power of the press; vagrant tides of pedestrians swelled into a sea that seemed to be moving in every direction at once. The last hour of the day made wassail as the menials of industry found themselves united in freedom with the bankers and executives of business.

There was no distinction. They were all ephemeral drops in the vast wave of humanity, until a slender young man of medium stature emerged from the tide and stopped before the ornate show-windows of Eichelstein' s Pawn Shop. He wasn't exactly a pauper, for though his clothes were somewhat shabby he was still two jumps ahead of the bread line. One jump was a leatherette casewhich he carried in his right hand, and the other was a battered brown portfolio he held under his arm. Had you inquired three months ago, he would have told you with all the confidence in the world that the little portfolio held history in the making. And had you listened long enough, you would have believed it.

For a while he stood, oblivious to the roar of the city, staring with a vacant eye at the lavish display of pocketwatches, accordions, field-glasses, gaudy jewelry, saxophones, andirons, and rifles. All their bizarre fascination was lost upon him. Not even the resplendent drummer's traps in the background surrounded by luggage had the 16

power to move him. His mind was lost in the dank corridors of thought that led through the underground recesses of the past. There were ante-rooms of offices,refusals, letters of rejection, and a wallet whose sides had come closer and closer together until they had finally met.

The imposters, Disillusionment and Dejection, tugged at his sleeve and he entered the shop. A sharp-featured man with an inscrutable countenance looked over the counter at him, enquiringly. The man who was unmoved by the lure of the show-windows tossed his leatherette case on the counter.

"How much am I bid," he said, "for this most excellent typewriter?"

The other examined it critically.

"Ten dollars."

His customer looked dissatisfied.

"Oh, come on, Shylock," he protested,. "one pound of flesh is enough. Just look at that machine. It set me back sixty dollars, and it's hardly a year old. It's a golden opportunity for you at fifteen dollars."

The loan-agent was only slightly impressed.

"Well," he conceded, '.'I'll be a sucker and give you eleven. You've been a pretty steady customer."

"You're a hard man," said the other sadly. "You can't realize the sentiment I feel for this wonder of science. My conscience won't allow me to part with it for such a paltry price. It wouldn't be fair to the typewriter. I'll tell you what, we'll compromise on fourteen dollars."

The proprietor laughed.

"I'll make it eleven seventy-five," he smiled. "Seventyfive cents for persistence. That's the best I can do. My customers wouldn't appreciate its sentimental value, I'm afraid." 17

The man who had been disillusioned regarded the machine fondly for a moment.

"Mister,U he said, "you've bought a typewriter. Sold to the bidder for eleven dollars and seventy-fivecents!"

The loan-agent counted out the cash and handed him the redeem-slip which the other flipped back.

"No, thanks," he said. "It's yours, body and soul to sell when and as you pleace. This is the last time I'll see you. So long, and good luck."

Once out of the shop, he made his way to a restaurant at the corner and ordered coffee and a sandwich. Somehow he did not seem to care for more.

Ordinarily, a man finds in a meal surcease for sorrow, brief though it may be. But here it lacked its magic. Perhaps it was because a sandwich and coffee are, at best, a trite repast and unworthy to be called a meal. · Or perhaps not even a banquet could have sufficed. He felt as though he had a lost an inherent part of himself now that his typewriter was gone. What shreds of confidence that had remained within him were left in the pawn shop.

He opened his portfolio and drew forth a sheet of paper. Moving the dishes to the side he wrote the following letter with his pen:

Dear Kathryn:

Far be it from me to be an apostle of gloom, but I do think it's only fair to tell you the truth. I know now I should have written this long ago instead of telling you that I was getting along so splendidly here, but somehow I couldn't. You had so much faith in me that I hated to let you know I've been a failure. It just didn't seem possible after I met you. I suppose your father was right when he said I was a worthless fellow and that you ought to discourage me. And you were brave enough to stand up against him! Even now it makes all this seem like a terrible dream. I realize that I

have no right to hold you to your promise any longer. You have so much to look forward to that I would be unable to give you. So here's luck and happiness always.

Robert.

He folded the letter carefully and searched in his portfolio for an envelope. There were none there. The clock on the wall indicated five-thirty; too late for a stationery store to be open. He arose, paid his bill, and left the restaurant.

Half way down the block the versatility of the three gilded balls of the pawn shop suggested envelopes. He turned his steps in that direction.

As he entered he saw there was someone ahead of him, an adolescent, impressionistic counterpart of nimself-at least as far as clothes were concerned-bartering for a typewriter.

"The price, I tell you," said Eichelstein, "is twenty-five . dollars. I can't sell it any cheaper."

His would-be purchaser seemed disappointed. He stared at the object of his desires for a moment before he spoke.

"Then haven't you another you could let me have for twenty? Honestly, that's all I have-twenty dollars and fifty cents."

The proprieter thought for a moment.

"Nothing but a machine that prints only capital letters, and you couldn't use that for writing."

The other laid the twenty greenbacks on the counter and grinned from an otherwise strangely enigmatic face. The laughter in his eyes was tempered by an impish shrewdness.

"Twenty good American dollars," he said. "They're harder to get than they used to be. I've been saving a long time to get that much at one time. Come on and be a sport, and let me have it. I need it a lot."

Eichelstein hesitated and then shook his head.

19

"No," he said, "the price is twenty-five. I'm sorry." He glanced at Robert.

"Listen," said his youthful customer, "we'll make it a sporting proposition. If I can guess within a dollar of what you paid for it, will you let me have it for the twenty?"

"It doesn't matter what I paid for it," said the loan-agent. "I know what I can get for it, and there wouldn't be much point in selling it any cheaper."

The other seemed to accept it as final. He was visibly disappointed. His expression of eagerness and expectancy faded almost to wistfulness.

"I was hoping I could get it," he said looking down at the key-board in front of him. "I've waited so long to get one that !--counted a lot on getting it today. Well," he added as he picked up his money and turned to leave, "I suppose I can wait a little longer."

The face of the man with ·the shabby suit who had been looking on the while softened. Dejection turns to dejection for reason tliat nowhere else can it find solace. Here was something that moved the depths of his sympathy. The face of Eichelstein also changed. What true man could resist such an appeal? Certainly not an humble pawnbroker whose prices are, at best, considerably variable-especially when the customer is about to leave emptyhanded.

"Wait a minute," he called almost grufH.yto his departmg prey.

The other hesitated, and returned.

"You want that typewriter pretty bad, don't you, kid? Well, I believe that's all you have, and I'm going to sell it to you."

"Now you're talking," said the other with enthusiasm. "Here's the twenty."

He handed the money to Eichelstein, picked up the typewriter with alacrity, and started to leave.

"Don't I get the half-dollar?," asked Eichelstein querulously. ·

Out it came reluctantly.

"No, you keep it, kid," laughed the loan-agent. "Buy yourself some paper."

He waited until he had left and then turned to his other customer.

"Funny thing about that boy," he said. "He's been in here a dozen times in the last year. Lives in some dump down town and sells magazines at a stall on the corner. He's got enough ambition for a dozen people in his class. Thinks he can do things with that typewriter."

The voice droned on, but the man who carried the unsealed letter in his pocket did not hear. He had rubbed the lamp and was speeding away on the magic carpet of imagination. Why should anyone place so much faith in a typewriter ?--a magazine peddler--propably read when business was dull,--poor environment--ambition--yes, that was it !--character versus environment conflict. He buys a typewriter at a pawn-shop and finds that it prints part of the 'C' and 'H' poorly-- and then one day a man comes to the magazine stand and asks him if he wants to make some money--a lot of money--

The voice of Eichlestein grew sharper.

"Eh?" said his customer startled, coming to earth with a jolt. "Did you say something?"

"I said, what is it this time?"

"Nothing," he answered absently, slightly annoyed by the interruption. What a story that ought to make if handled properly! Why, if the man happened to be-"I think I made a mistake," he told the pawn-broker, and left the shop. 21

Outside, the city roared boisterous!y for him to join the fray. The first faint lights on the lamp-posts appeared and shed a glow upon the white-hot anvil of fate. Stepping to the edge of the curbing, he took the letter from his pocket, tore it to bits, and threw the scraps into the gutter.

Down the street he encountered a beggar selling pencils and erasers.

"How's business?" he asked, pausing before him. "I don't know," said the wasted derelict, "I haven't seen him today."

His superior dropped a quarter in the tin cup he held. "Keep the change," he said. "We professional men have got to stick together."

If the beggar was surprised, he did not betray it; for he had learned that such things are not given to explanation other than what the Gods had allotted each in his separate star.

Ca,ticci~dtaf ien- )J.ckaik~wJ.k'/

BY HAMILTON ENSLOW

I am a trumpeter in a dead city Sounding my call above your changeless sleep; You do not stir, but f armless dreams of pity Cloud your dark brain-you sigh, at last, and weep ...

My endless reveille rings about black windows, Knocks on dull walls, affronts the skY; Wins as much answer from the shadows As from the trance in which you lie.

It is as well, perhaps. Continue, dreaming! am content with echoes, as they break Clanging about your vision, seeming To move you, though you do not wake.

Not for this will I cease blowing

The brazen note that goes unheard, Unanswered; though you sleep, unknowing And understand no single word.

~eviewJ

Within The Gates. A play by Sean O'Casey. Macmillan Company, New York, 1934.

WITHIN THE GATES is one of the most powerful and significant dramas to result from the Irish literary revival of the twentieth century. After spectacular successesof his earlier contemporaries and of his own earlier plays, f une and the Paycock and The Plough and the Stars, Sean O'Casey has produced a play of more depth and sincere emotion than any of the preceding Irish dramas. At its production in 1934, critics realized its emotional intensity and tragic pageantry as a new and progressive element in drama . Even the banning of its production in Boston has not prevented this play from being firmly established as one of the year's major contributii:ms to drama. In a season which has already witnessed the innovation of reversal in time in Merrily We Roll Along, the morbid abnormalities of the adolescent in The Children's Hour, and the utterly new angle on the familiar relationship of the "eternal triangle" of Point Valaine and The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles, Sean O'Casey has presented something unique. Across its scenes pass so many examples of the desperate and coarse elements in society, that one is amazed by O'Casey's handling of a sordid and unpleasant subject in such a way that an artistic and poetic effect is achieved. The tragic pageantry and realism of the chorus heightens this effect. True, its poetry is starkly intense and contains none of the sentiment usually found in this type of drama. O'Casey has deliberately avoided any suggestion of plot or character development. His whole play and its characters are suspended in a timeless abyss. This drama is in no way a story. It is an effect, a panorama of life among classes whose ignorant ideas and philosophy often approach super27

st1t1on. There is the atheist, the unemployed ex-soldier, the nursemaid, the whore, the Salvation Army officer, the soap-box orator, and the bishop, all of whom are engaged in settling the world's affairs on a park bench. They have the typical views of their economic class on .religion, or more accurately, anti-religion, the Ten Commandments, the revaluing of the pound, and trade. For instance:

Foreman: " ... even a prominent politician's beginning to realize the necessityfor the belief in God. I read the other dye thet a clergyman said that it was the opinion of the Right Honorable Winston Churchill-"

Man With the Stick: (interrupting vehemently)

"Winston Churchhill ! Why do you bring irrelevent trivialities into the discussion, man?"

In Within The Gates is presented a genuinely tragic picture of people who can break any of the Commandments without the least twinge of conscience, and with the next breath, hysterically pray for salvation from the flames of a Hell for which their environment has instilled in them a frantic horror. To make their desperate ignorance more poignant, the only religious succor extended to them is from · a Bishop, whose hypocrisy is unconsciously expressed by the whore:

" ... you'd expect the very nightingales to warble Onward Christian Soldiers during their off-time."

The intense reality and haunting pathos of this play are sufficient proof that in Sean O'Casey, Europe possesses its one outstanding genius.-K. B. B.

Poems, by STEPHEN SPENDER. Random House Publishing Co., 1934. Vienna, by STEPHEN SPENDER. Random House Publishing Co., 1935.

YouTH has always struggled to touch the very heart of being-to discover the essence of life-something to signify its purpose and justify its being, by which we can understand ourselves in its relation, ourselves in relation to the whole world. Young poets have sounded a wistful note for many a day, escaping from the world of stern reality or crying out against it, believing that ever elusive essence to have fled beyond the din of cities and the struggle of society. But Stephen Spender is a poet of a new courage, who sees the recent past crumbling close behind him and offers it a challenge. He defies its power to crush him beneath its rums:

"How can we kill these dead? 0, kill their worth!" He seeks a new world order in a communistic doctrinethe essence of which he builds upon a love for humanitya love that includes in its breadth even those who, in his mind, have wrecked the world and brought it finally on the verge of chaos:

"There is no question more of not forgiving, Forgiveness become my only feeling To understand their lack of understanding Has absorbed by entire loving, Yet sometimes I wish that I were loud and angry Without this human mind, like a doomed sky That loves, as it must enclose, all."

Spender's purpose has a depth and dignity because he is an intellectual as well as a poet of feeling. Of his words he makes sharp, clean, delicate instruments that cut to the core and strip bare of any elaboration the essential meanings of words, leaving the imagination of the reader free to create its own images. Spender projects meanings into words which, by their suggestion, spur the mind and emotions into 29

limitless directions. They take the mind's breath! He asks, and necessarily, the cooperative imagination of the reader. He demands also an intellectual "set" or approach for understanding. A poetry that can reach as deeply into sensation is supremely satisfying, but it necessarily implies an intellectual support. The reader also must have experienced. It is not explanation that he offers; Spender does • not seek to make of poetry that which should "strike the readers as a wording of his own highest thots and appear as a remembrance." It is an awakening. It does not surprise, by its "fine excess,"but by its singularity of suggestivity. If the direction toward which Spender points is in any way indicative of the future, poetry will strip itself of its narrative intent, except as narration can develop the progress of thought. It will become poetry of thought, of suggestion, of interpretation rather than of explanation and elaboration. Idea and vision will matter; imagination will direct the approach. This poetry will no longer seek beauty alone. If it can offer truth, it will have served its purpose. This is the new day toward which Spender points.-M. T. C.