th€ ffi€SS€nq€U

A SPECTRAL LITERARY MAGAZINE

THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND 1973-1974

1973-74

To the reader:

The material we have published is simply a specimen of the University. Our criterion was to admit everything, and exclude nothing. Consequently we had little to do with it.

Kelly Haley

Paulette Parker

Wade Reynolds J

Circe

heard that several of your helmsmen disembowelled themselves, Thinking it the end of the world. It was a good storm. The days died young. The sun at noon could scarcely crawl above the waves. Trees on shore ripped out their hair. Snakes shed their skins and tossed them on deck for you to feel. And now, thrown on my island, you wait with spears and eyes like those of old women at night.

Let me anaesthetize you from pain (but mainly other wide blue eyes) and store you within this cask of child-hide ringed with staves of frail bone. Alone, you may glaze in safety from my windows as those swine, lean dying swine, creep to their wives, and sunset eats the flesh of day.

Ellyn

Watts '75

on a 45 degree isoscelesright triangle

balancing on a 45 degree isosceles right triangle i watched the poetry of your eyes, and caught within a geometric plain i found it not too difficult to stand on nonexistant lines. but when your gaze turned glass-eyed glazed there was only plane reality from which i, in a moment, fell, to lie like glass about your feet in a thousand pieces.

wade

reynolds '74

i walked a narrow line, very fine, so smal I it might have been sunlight on a thread, or a beam of moonshine shining early in the morning. and now i've found (a time or two) it's been truly said, hate and love are separated only by that thread, from which i'd fall at any step without a moment's warning.

wade reynolds '74

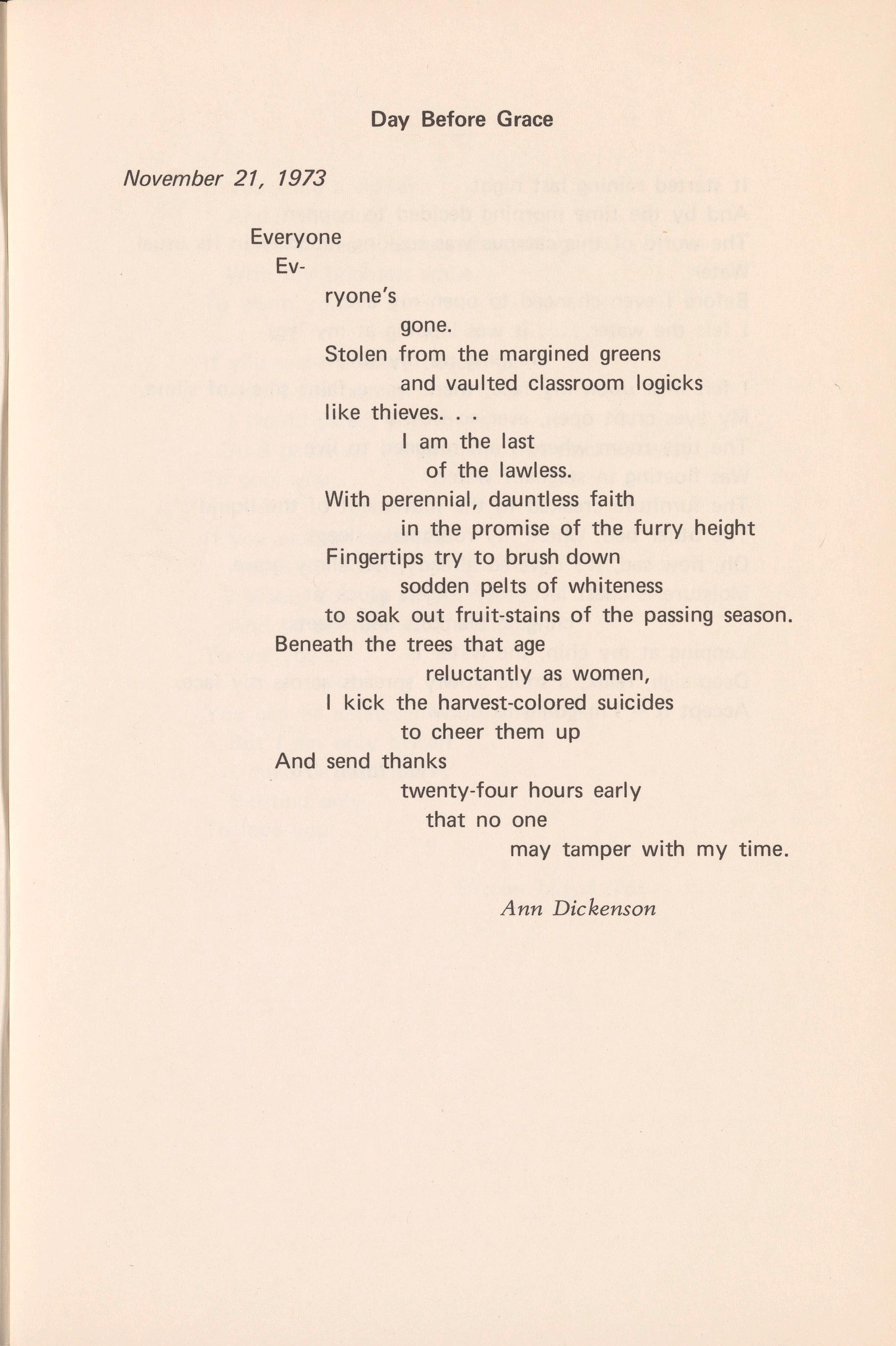

Day Before Grace

November 21, 1973

Everyone Ev-

ryone's gone.

Stolen from the margined greens and vaulted classroom logicks like thieves ...

I am the last of the lawless. With perennial, dauntless faith in the promise of the furry height Fingertips try to brush down sodden pelts of whiteness to soak out fruit-stains of the passing season. Beneath the trees that age reluctantly as women, I kick the harvest-colored suicides to cheer them up

And send thanks twenty-four hours early that no one may tamper with my time.

Ann Die kens on

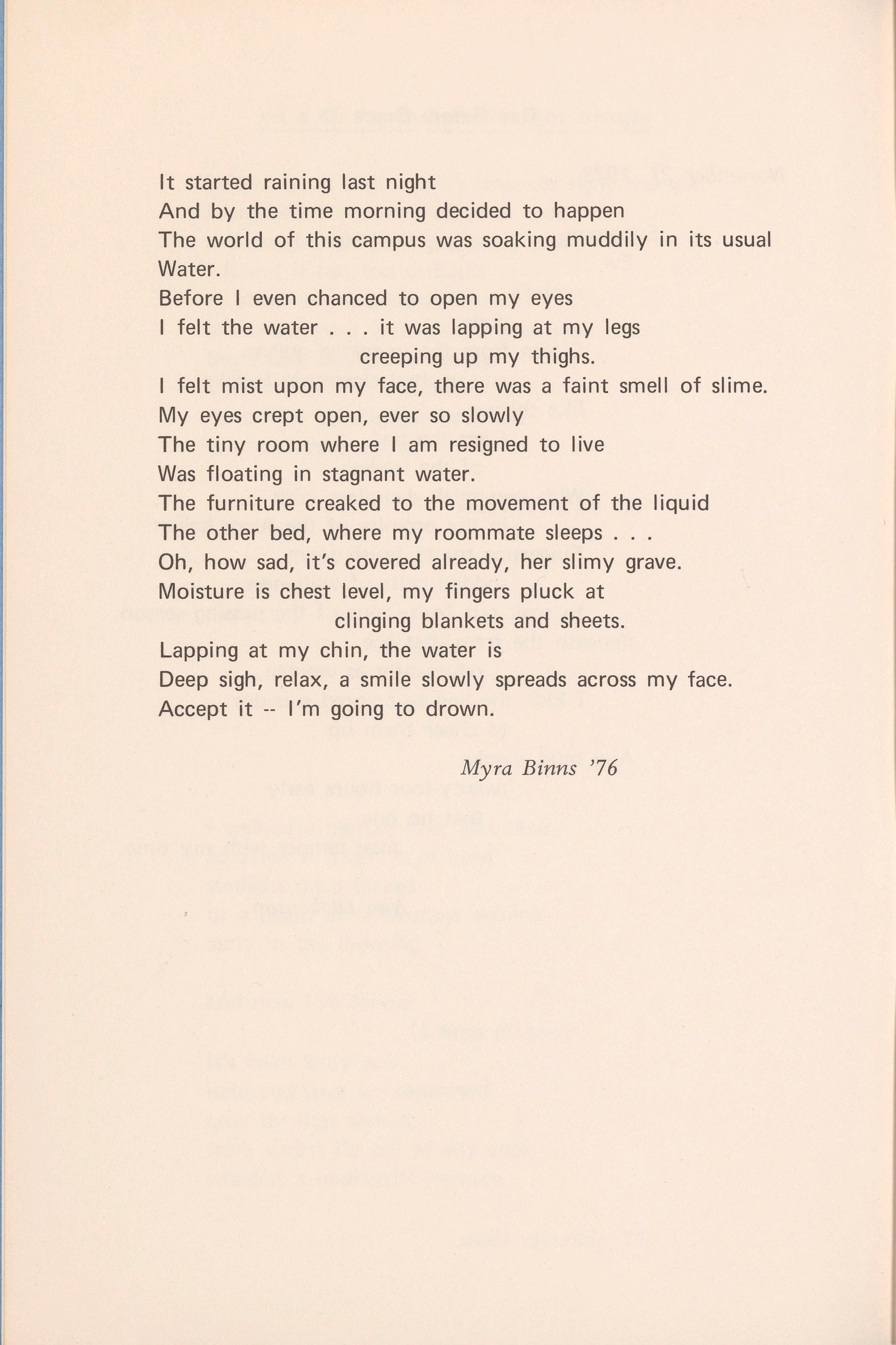

It started raining last night

And by the time morning decided to happen

The world of this campus was soaking muddily in its usual Water.

Before I even chanced to open my eyes felt the water ... it was lapping at my legs creeping up my thighs. felt mist upon my face, there was a faint smell of slime. My eyes crept open, ever so slowly

The tiny room where I am resigned to live Was floating in stagnant water.

The furniture creaked to the movement of the liquid The other bed, where my roommate sleeps ...

Oh, how sad, it's covered already, her slimy grave.

Moisture is chest level, my fingers pluck at clinging blankets and sheets.

Lapping at my chin, the water is Deep sigh, relax, a smile slowly spreads across my face. Accept it --I'm going to drown.

Myra Binns '76

If you were a flower And I the sun, If I would greet you every morning With my brightest smile

To warm you ...

If you were a sandy beach And I the ocean, I would caress your brow And bathe all the scratchy hot prickles away To cool you ...

If you were a mountain And I the forest, I would curl up at your feet And be content just looking up

To see you ...

You can be whatever you want to be But I am only myself. I must be satisfied Existing only

To love you ...

Sharon Lloyd '76

This is the dramatic situation: Zebras are stealing your love.

There is nothing you can do Home remedies have failed

You can't talk to zebras

They refuse to be cudgelled

You hire a chimpanzee

But he runs at the first show of force

With their hooves and teeth

They are angrily smashing your last barriers,

Tables and chairs flung hastily against the door. When you finally relent

They take it all

The hour glass, the moth collection, last year's prize asparagus . . . everything

They are phantom zebras

As you watch them flying away

Their wings silently beating

They do not turn the sky black

But rather stripe it black and white.

Peter

Woolson '74

A FABLE

In the twelfth century, in the country of Azulia, there was a ruler whose courtiers named Shandrah, The Sie One. Shandrah was not a vain sort of fellow, and his courtiers, by and large, got nothing of the king's benevolence for their flattery, unless they were very beautiful women--then they basked in the radiance of small gifts of gold and stuffed figs. Shandrah, after all, was at least a practical person, if not wise; the Koran and the ways of the court held unfathomable mysteries for this royal sojourner, but the avenues of money and the whiles of women were instinctual and unerring for him: under him, the kingdom prospered. There was a camel in every tent, mocha of the finest quality in every pot, and the lips of the masses were forever praying to Allay for the longevity of Shand rah.

Needless to say, Shandrah got old, and his days of great power and wisdom waxed thin. His eyes became cataracted, and he was always passing gas. His harem, once known for its beauty and charm, became slovenly and fractious from disuse. Even the old custom of strong coffee and intoxicating hookah before bed was forwaken, and the kingdom sorely grieved for their expiring monarch. Shandrah, too, saw his age and gradual denouement growing close, and, good ruler that he was, began to dispute with himself the matter of heredity. Normally, the kingdom would have gone to the eldest son, in this case Adil, but Shandrah loved this one least. His youngest son, Radah, was the apple of his eye: Where Adil had studiously obeyed the kingly traits of acquiring a thorough knowledge of the Koran and the cults of Azulia, and had gotten the highest praise from learned men, Radah had been around the countryside, whoring after wild women and practical knowledge. This, Shandrah thought, was best; how much better to live a life of a tree, with one's roots spread deep and far into the suckling ground of life, than to be an unroasted pistachio, unflavored and bitter. With this troublesome thought, the old man languished and went to many a sleepless night.

The day that he crumpled in his mosque, and the phisiks had ordained ominous drugs, Shandrah grew fearful for his life and kingdom. Calling Radah to his bedside, he whispered into his son's florid ear a cryptic message: "Radah, bread of my breast, joy of my life, listen; you are the last of my children, and yet the wisest; you, above enyone else in the royal family should ascend to the right hand of Allah here on the throne. I would be less than a father and leader if I told you to destroy your brother. Besides, I would not favor a Cain to lead my people. But this much I can tell you: the people of Azulia, being once the victims of a cruel hoax of the Romans in the sixth-century, decreed that from that day forward, no horse should rule the land. The hoax, as your brother, learned idiot that he is, surely knows, was this. The arrogant Romans, after defeating our armies, took us for fools. They raped our women, abducted our children, and cajoled our men as if they were cows and sheep. The final insult was the installment as governour a stuffed centaur, half-man, half-beast. The Romans consulted it day by day, as if it were a oracle, and the supposed decrees issuing from its divine lips were law. My son, this I can tell you: Show your brother for the horse that he is, and you will rule the kingdom." And, speaking these very words, Shandrah, as kings and potentates are wont to do at such dramatic times, went to that big hookah bowl in the sky. Shandrah's advice perplexed poor Radah, and he stayed from the harem for many days. Finally, one hot night, his favorite concubine, Hornina, came to visit him in his quarters. "My liege, what ails you? Has your mighty power left you, and thus your harem? What gives?" Radah, smart devil that he was, knew that Hornina was a sly and ambitious girl who wished to be Queen C of the harem. Confiding in her, he told of his father's last words, and reminded her of Adil's coronation three days away. Hornina

thought for a moment, and whispered into Radah's ear, "Prince, lure your brother into my quarter of the harem tomorrow night at 9:30. Assemble secretly your advisors and tutors outside the curtains of my room, and when I yell, "alli!" throw the drapes aside. Then you will truly see your brother as the horse." With a mysterious glint in her eye (though Radah was not quick enough to discern that gleam of invention from an invitation to passion) Hornina kissed the prince, and departed

The next day Radah cornered Adil in the Mosque. "Hey, Adilly, brother of mine and regent of the crown (Radah knew when to use obsequious flattery), want a hot time tonight with an almond of a cobra?" "Shh! such profanity in the house of Allah! and in the presence of my tutors!! I should have you whipped!" whispered the infuriated Adil. Unabashed for all this, Radah innocently added, "I'm so sorry brother, keeper of timeless wisdom. It's just that she has such a nice f/iti,withrounded noozolas, and she can really use the Rancon twist to expertise and delight! After all, I thought that since you were being coronated in a couple of days, you would like one last bash." From the moment that Radah mentioned Hornina's flitti, and elaborated on her charming noosolas, the foolish Adil was caught. The very mention of the infamous Rancon twist almost caused him to commit the ultimate sacrilege in the very seat of God. "Alllahhhaa-haa! Hot spit! When, and where?" whispered the infidel Adil, his words already hot with the sin of the Christian barbarians. "At my harem, 9:30 shartp," said the wise one, and quickly left. He didn't like the mosque, or the priests, but in those days, the smell of undeoderized feet almost made him wretch. He secretly believed that was why his brother was in such poor shape sexually, his feet repulsed all the young and attractive harem girls.

At the appointed time, Adil arrived at Hornina's tent, little suspecting that his brother and cabinet were stationed outside, like voyeurs. "Hello there, Adil, keeper of Allah's ways (At this, Adil almost ran away. He was ashamed of what he was going to do to such a nice girl-the Rancon twist-what would his mother say?) and debaucher of the jaded: how goes it?" asked Hornina, unveiling in the sensuous Eastern manner her middle noozola. "Pretty good ... l, ah, uh, listen. Radah told me that you were a Rancon twister ... ! didn't say it, I just heard it, and I was wondering ... ?" the meek Adil fully expected to get his face slapped, but instead was surprised by a broad smile on Hornina's face . "Oh yeah? What else has he told you?" she asked. "Oh that's all. ..well, what about it?" he queried, his lips red with desire.

Hornina, seeing her opportunity, quickly got a bridle from under her bed, and brought out a small riding crop from her cabinet. Looking at Adil coyly, she murmured, "Silly, first there has to be the chase, doesn't there? Here, you put this on." And, handing the bridle to Adil, she quickly went to the other side of the chamber. Adil, being a bit of a masochist, put the bridle on and waited for the sting of the whip. Suddenly, Hornina ran over to the crawling Adil and jumped on him, cowboy fashion. "Whoopie, Whoopie, Alli!" she cried. And at this, Radah ripped open the curtains. "See," he cried, "look at my brother, who crawls as if a horse, yet acts more as the ass." And the tutors and scholars conferred, and then decreed that the ashamed Adil be banished from the court forever. Radah, the wise one, became king, and the country was a happy and prosperous one. Adil, it was rumored, became a jockey who won many renowned titles.

The moral, of course, is that when someone takes you to Hallelujah Downs, don't let them make an ass out of you.

Shawn Majette

TO ARIEL*

0 spirit of blackness, Cruel tongued creature,

Like a cat you were:

Creeping under lettered lines

Crouching behind thin stanzas

Pouncing suddenly

Upon parlor poetry readings And volumes bound in serviceable cloth.

That part of me which is drawn Unwillingly To mutilative automobile accidents And secret bloody crimes

Returns to you again and again.

What miseries lie beneath your Inexplicable

Yew trees and blank mirrors? What nightmares did you Compress

Into swarming bees and a dead baby?

Peering back at us through the gaseous window, You could hand us a slip of paper

Neatly categorizing Every symbol, Every horror, But it is better that you do not. Unlocked, explained, released, They would not be beautiful.

0 spinner of evil spells,

0 weeping, vengeful one,

0 Ariel, How lost you were.

Sharon Lloyd '76

* Ariel - book of poems by Sylvia Plath

A Salve for the Wound

Christ, Peter thought, staring blankly upward at the dingy white ceiling. He felt again the dull throb of pain where the needle was sticking in his arm, taking away a pint of blood as he lay passively on his back. Staring at the flat flesh of hjs elbow joint as his arm lay palm upward and rigid at his side, he imagined the short, thick needle buried inside the vein. He wondered if he was actually seeing the pale blue beneath the skin jump with each pulsebeat. A few feet away a nurse stood talking absorbedly to a co-worker, and Peter noticed her harsh whiteness offset by a slightly bulging plumpness. He stared, neck craning off the stretcher, at the general hubbub of the blood 'donor' center. In the large room there were perhaps fifteen stretchers, with people in all stages of donation, from being escorted to a prone position to holding cotton swabs on the recent wound. Nurses scurried about, earring thick plastic pouches filled with the dark red or afixing empty ones to the side of the movable stretchers. It seemed to Peter that he had been lying there a long time, and he looked over in irritation at the nurse who was still holding animated conversation regarding her children's schooling. I hope to God she knows what she's doing, he thought. He ached to peer over the side at the bag where the thin plastic tube disappeared, but the jab in his arm prevented him. He lay back and closed his eyes, attempting to ignore the pressure. A noise at his head caused him to open his eyes, and he saw the nurse, at last, bending over checking the pouch beneath him.

"Just one more minute, Mr. Verne," she said and was gone, this time further off. Peter's eyes fixed blindly upward and waited. The nurse bustled back and without hesitation plucked the needle from his arm, applying a cotton swab to it and telling him to hold his arm ceiling-ward. He remained in that position for some time, till a numbness could be felt in his entire arm, from the blood rushing downward. The nurse was at his side, sealing the pouch after letting some of the blood into a clear testube.

Peter asked, "Could I see that?"

"What?" said the nurse, straightening up.

"That testube," Peter repeated himself evenly. "Could you hold it up to me so I can see it." The nurse, somewhat surprized and as though humoring a spoiled child, held it before his face . He stared, fascinated at what his heart had pumped out. The deep, dark body of it held him as he felt the living substance inside the glass with its black rubber stopper. Its musty red fullness was unlike any red he had ever seen before. Suddenly he felt the presence of the nurse and said, "O.K. Thanks."

She finished the securing of the pouch and turned back to him, lowering his arm which still remained upright. Applying an oval bandage to the small red spot she asked, "Any wooziness?"

"No," Peter replied, and sat up to the other's jovial "O.fS." He sat with his legs dangling above the floor as the nurse filled out and signed a small form. Handing it to him she said,

"Take this over to the main desk, they'll take care of you." Her automatic "Thank you" at his back went unheeded as he weeded his way through the maze of stretchers, his good arm clutching the slip of paper and pressing against the other. He made his way up to the •'main desk," which consisted of two plain glass surrounded windows, both of which had short lines of men clutching slips of paper similar to his own. Peter stepped behind a thin, grizzly man who wore baggy trousers and a short sleeved blue shirt, even though it was close to February. The man had thin grey hair, and Peter noticed from behind his knobby, cartilaginous ears, his stooping posture and the bend in his knees. Glancing over at the other line, Peter noticed with a grimace the unshaven grey faces and the overcoats shiny from long use. He wondered if they were questioning his clothes

which, while not expensive, were at least a good sight better than theirs. He put his hand up to his face, which was narrow, though compact and intense. He too, had not shaved that morning and his heavier than average beard must make him look haggard, he thought.

"Christ let me get out of here," he wispered to himself under his breath. He felt what he thought was a wave of nausea sweep over him. Maybe I shouldn't have come straight from work, he thought.

The man in front of him was at the window now. Peter looked back across the room to the stretcher he had lain on. Another man was lying quietly with his arm away from his body, the nurse busying herself over him. Then it was Peter's turn as the man in the short sleeves vacated the window, and he pushed the paper into the teller's stodgy fingers. He studied it for a moment and said,

"Type 8-negative. You're a rare breed, mister. Fifteen-sixty." The man slid the green bills and coins toward Peter, which he scooped up without counting and rapidly crossed the worn wooden floor toward the door. Just as he had pushed open the door and was about to bolt out, a puffing, overweight man with a bloated face began to step in. There was confusion for a moment, and both stood staring at one another. Peter disgustedly stepped bqfkward to allow the other entrance, who lumbered past wheezing "Scuse me, mister". Peter stepped out into a freezing rain and leaned against the front of the building, waiting for a moment of unsteadiness to pass. After a few moments he breathed a sigh of relief, and head down, hurried over the dull concrete sidewalk in the rain.

Oh Christ, he thought.

IIPeter felt some relief seated on the bus staring out the window. There was something pleasant about giving onesself up to the rocking and swaying, especially after waiting many long minutes in the rain, standing. He had the seat all to himself, a rare thing in the mass transit system of Dayton, Ohio, and he closed his eyes, feeling the motion. The bus ride from where he worked at the lumber yard usually took about fifteen minutes, but because of the detour he had taken he knew it would take a good deal longer tonight to get home.

HomE;, he thought, and frowned. He reached into his shirt pocket inside his leather jacket and took out his package of Chesterfields . Knocking one out of the package, he placed it in his mouth and searched for a match. He l it the cigarette and felt a few pieces of loose tobacco from the unfiltered end get sucked into his mouth. The harsh bitter taste of the coarse crumbs caused him to sputter, head lowered toward the floor and side of the bus. After he had cleared his mouth he leaned back against the green cushion and inhaled deeply, feeling the hot smoke rasp his throat and envelope his lungs. He watched the heavy blue smoke jet from his mouth in a thick, swirling motion, colliding with the thick bus windows and cascading downward. Again he inhaled deeply, and had to choke back a hacking cough. He stared glumly out into the greying daylight, the rain splashing and streaking the window A few pedistrians hurried along protecting themselves from the rain. lntermittantly the red taillights of car lights just beginning to come on could be seen. Peter noticed his own reflection emerging on the bus windows, and watched it for a few moments. He wondered if the loss of blood had caused a whiteness to his face or if it were the odd reflection on the glass. Noticing the tenseness around his normally calm brown eyes, he thought again bitterly, I don't know how much more of this I can take. Something is going to break. His mind returned to the seemingly ageless question which had been assualting his mind. What am I going to do? he thought.

The bus lurched to a stop to let on a drenched businessman in a soaked, but

expensive trenchcoat. He sheepishly looked to both sides as he made his way to the back of the bus. Peter's gaze returned to the approaching darkness outside. He pictured his wife, Charlene, at home, knowing, waiting for him to return. Maybe she would have gone out No. That would be an admission of something wrong, he thought. They both had been carefully avoiding it, not daring to approach for fear of the explosion which must follow. But it was clear to both of them now; it had to be, Peter thought. Two people cannot exist as we've been existing and not see that it was abundantly clear what they must do. Yet just the same we can't say it to one another, Peter thought. Or rather I can't say it, he thought. He scowled darkly and swore under his breath. He thought of his wife's slight build, with her high cheekbones and long yellow hair, her usually cheerful eyes that he used to tell her twinkled. They had known each other for a long time, much longer than the scant nine months they had been married.

It had been good then; good companionship and compatability at first, then respect and a genuine sensitivity for each other. There had been sex, too, before the marriage, though not ~uch because of fear on her part. Their relationship had indeed, grown, to a gradual interdependence for each other. They had reached the point where their thinking had become similar, each knowing instinctively the needs and wants of the other. Which made it so hellish now, Peter reflected darkly. He thought of Charlene as she would be when he entered the house, cooking or doing dishes in the kitchen, or upstairs in the duplex, which in his most private thoughts Peter was at first ashamed to bring his wife to live in. She would be busying herself with something as he walked in the door and they would both attempt a cheerful "Hellow" which rang hollow with falseness. He could no longer meet her eyes, which said above all else, above the worry, despair and even fear, said, why? That he could not stand. He simply could not face the quiet, trusting, gentle look in her eyes, that seemed to cry out to him.

And he was afraid. Afraid because he was so much stronger than she; not only physically but mentally he could stand the pain. But the thought of inflicting this hurt on her affected him deeply, and he knew he would think about it, regret it for some time to come. He knew he would, indeed, perhaps always be returning to it somewhere in the back of his mind.

At that moment Peter's reverie was broken by someone plopping down, wet and smelling of the night air, in the seat next to him. He looked over briefly at the middle aged housewife with her plastic see-through rainhat and dampened shopping bag. Peter felt the bus lurch forward in the night, which was now completely black. The rush hour traffic of those lucky enough to afford cars of their own whizzed past below the bus, and Peter watched the tops flashing by. He had had some thoughts of soon getting his own car, he remembered. That seemed like ages ago, now. And God only knows what would happen to them financially. Peter became lost in his own thought and worry, and having crushed out his cigarette many minutes ago, he mechanically reached again into his inside pocket. A second later the acrid blue smoke was spiralling upward in the milky haze of the bus' lights. The woman alongside him, who was pressing her flanks uncomfortably against him, looked over with a hint of dissaproval in her face. Peter ignored her and returned his gaze outward.

Thoughts of stopping at the bar on the way home ran through his head. He wondered momentarily, a sense of temptation and guilt overcoming him. Good God, is that becoming a habit? he asked himself, shaking his head. He dropped his hand into his lap, and half heard and felt the crinkle of the bills in his pocket.

If that were only the worst of it, he thought, tersely . I can't sleep, I can't think straight, I can't do my work down at the yard. He thought with disgust of a bookkeeping error he had made last week which had come to light today at work. Because of it a

supply of building materials which Jerry, his friend and manager of the yard, had promised to one of the largest contractors in town, had not been ready. Thank God Jerry and I have known each other for such a long time, Peter thought. If it had been anybody else they would have been looking for another job by now

Again the bus came to a rolling halt and the woman next to him got up clutching her shopping bag and left. Peter watched her bulky figure retreating clumsily down the aisle. She dissappeared, stepping downward from the bus. So what am I going to do, Peter asked himself mercilessly. Divorce. The word had such an ugly connotation. He rolled it over in his mouth, picturing himeslf saying it to Charlene, who, even though she could not help but know something was dangerously wrong, could not know the whole truth. Because the truth, the simple truth, was that Peter believed he had stopped loving his wife He saw the neon lights of the neighborhood ba r just ahead at the next stop , and grasping the back of the seat in front of him, swung out into the aisle.

Ill

Charlene lifted her red swollen hands out of the hot dish water and stared at them a moment The harsh white detergent suds left a lingering smell and she noticed the knuckles were unnaturally large. They were not exceptionally pretty hands, she thought, but were well shaped and smooth. She glanced over the white porcelin countertops and around the old kitchen, checking for any more dishes . Not seeing any she plunged her hands again into the water, feeling the skin tingle and bristle. She located the metal stopper and pulled, feeling the water suck down the drain. She ran some cold water over the sink and her hands, drying them on a dishtowel. Turning around she surveyed the room. It was a small , and despite her efforts, a rather bare looking room. The entire house, for some reason, whether because of the lack of sunlight or perhaps because of the dull green walls, did not lend itself to a warm atmosphere . The kitchen had a green topped oval table with chrome rim and tubular legs, which was the first thing seen upon entering the house Peter and she ate their meals there in the kitchen, because the house did not possess a dining room .

Charlene looked up to the round dark plastic clock with its glinting gold hands and thought that her husband should have been home now. She placed both her hands on her stomach and thought, I hope he comes straight from work tonight. I don't understand him wanting to stop at that bar on the way home. Not that I mind him having a beer, she continued thinking, and he says he has friends that stop in there after work, too. It's just that it is not like him; Charlene paused, with a slight turn of her head. She crossed the linoleum floor to the aging stove and lifted a teapot off the burner, running some water into it at the sink. She lit the stove from a small box of kitchen matches and stood on her toes to reach a teabag from the top shelf of the cabinet above. Dangling it by its string, round and round, she thought, it's just not his nature. He never drank before, even all the time before we were married. At the most he would have a beer only if someone were to insist at a cook-out or something. The copper colored teapot began to hiss and she twisted the knob and poured the bubbling water on the bag.

But then, she thought, if he does have some men friends there . . ., He doesn't know hardly anyone his own age since we moved right after the wedd ing. There's always plenty of women around for me down at the department store but the only friends he's got are the one's he works with. Charlene carried the steaming cup of tea to the table and sat down in one of its plain white plastic covered chairs. A stew was bubbling on the rear burner of the stove which she had had time to make because she had come home early tonight; it was Peter's favorite . Tonight, of all nights, let him come straight home, she thought She bent her head to take in the sweet steam from the tea, and took a small sip,

feeling the heat go down her throat and into her stomach. Into my stomach, she thought. She inclined her head and stared silently at the thin white sweater around her waist. A glimmer of concern crossed her face and she looked up again at the silent clock. She arose and went over to the stove. Lifting the top of the large pot she was hit with a burst of steam from the boiling stew . She stared down into its thick broth and thought , I don't know what's going wrong. Peter is so . ..different, now . I can't tell what he's thinking anymore. He doesn't tell me anything And now he's even begun sleeping on the couch, saying he's fallen asleep in front of the television. Or else he comes in late and flops in bed, thinking I'm asleep, and he has really been drinking, I can tell. She opened a drawer and rummaged about till she had fished out a large wooden spoon, with which she began stirring the heavy mixture. We just don ' t talk anymore, she thought painfully, momentarily sinking downward, letting the spoon hit against the side of the pot, unattended. But I've got to talk to him now. She took a breath and drew herself up, putting the top back on the stew . Turning the blue flame down as low as it would go, she crossed back to the table which took up so much of the small room. She continued thinking, what is it that could be the matter? Maybe we lack something But then we've only lived here for less than a year. And when we were first married things were so good, too. Those first few months we couldn't stand to be away from each other. Peter would come home from work all brimming with smiles, he really was like a boy, so happy and enthusiastic . Charlene smiled to herself, remembering. The money hadn't even been a problem then, even though we're probably better off now. And yet Peter looks so worried when the bills or rent is due, she thought Charlene thought of the electric bill which had come that day, in its dull brown envelope with the little window. Her face wrinkled in worry and she thought , Oh how am I go ing to tell him? I don't know what he'll do or say anymore Why did this have to happen now? Charlene took her small face in her hands and stared down at the floor, remaining in that position for some time. Once she thought she heard something outside the door and looked up expectantly, but it turned out to be nothing but a nighttime noise. After a while she got up and poured out her cold tea and shut off the stew. She felt she had no appetitite, but almost forced herself to eat before again g iving up.

That young doctor, she thought. He was all smiles and encouragement. Already a month along and you could hardly tell. Again she looked down at her thin waist, and pressed in lightly with her fingertips, afraid to press too hard. She was afraid of the small strange growing thing inside her that she would have to protect from the world, even in her loneliness and fear Clasping her shoulders together in the dim light, she shivered.

IV

Walking along in the wet night air Peter attempted to read the crystal of his watch by the criss-crossing shadows of a passing streetlamp . Swearing violently , he came to a halt and lifted his wrist very close to one eye, staring at the watch with great effort. "leven-thirty. Huh. Gotta get up at six-thirty " He inhaled sharply through his teeth and spun back toward the sidewalk away from the light He was again plunged into the damp dark and quiet as he plodded along, knees sayging, toward his house a few blocks away. Once he broke into a girl-like giggle and thought, that Roger. Says he was a Lieutenant in the air force over Korea. The only flying he ever did was by the seat of his pants, he thought and gaffawed outloud And the way everybody gives him Hell, he continued, it's just too much. He again broke into a laugh and thought, I swear 1 · thought Rog was going to bust somebody in the mouth. Shaking his head and still chuckling, he thought, what a character.

His grin gradually vanished and he continued staring down at the rain soaked blocks of sidewalk. Still musing, he thought, and they don't mind buying for you down there,

either. No sir, they're not stingy. House buys one for every three, just like clockwork. He felt the solid weight of the pint bottle of whiskey in his jacket pocket, pulling him slightly to one side. He thought of the money he had gotten that afternoon and reached into his pants pocket. A thin crumple met his hand and he thought guiltily of the money he had spent. "Goes like water" he mumbled. "Christ, the rent is due in four days," he remembered, and his eyebrows bunched together; his mind seething. Guess I'll make it this time, anyway, he thought. With Charlene's paycheck ...

A feeling of defeat came over him and he suddenly stumbled and almost tripped on the edge of the pavement. A whining sigh escaped from him and he felt as though he would like to sit down for one moment, just to steady himself before going on. He looked over to the curb and then around in a frustrated effort to find a dry spot. His legs ached as he attempted to peer into the rain soaked darkness ahead. All of the rather shabby homes here at the end of the busline on the outskirts of town were quiet, set back from the haze illuminated by the street lamps. He was only about one block away now, he realized.

Wonder if she'll be up, he worried. Guess I could of at least called. "No, Goddamn it," he swore outloud. I guess if I want to have a few drinks I can. He was silent for a few moments and his head swam. "Oh," he moaned to himself. Don't know how I'm gonna make it to work in the morning. He put the back of his hand to his forehead and pressed to relieve the pressure, and when he brought it away he was nearing the path up to his own door. Stopping at the foot of the path he stared at the silent, weirdly glinting screen door. He tumbled up the path and the few cement steps and entered the house. He was careful as he entered and felt along the wall for the light switch. The stairs to the bedroom went upward to his right. He found the switch and crossed the small living room space into the kitchen. Reaching over he flicked on the circular neon bulb overhead and was bathed in its white light, staring for a moment at the deserted room. He crossed to the sink and turned on the cold water tap while he reached into the cupboard for a glass. Most of the glasses were stacked up under pots and pans in the dish drainer, and pushing aside juice glasses and cups, he found a thick squat glass that had once been a jelly jar. A glare of contempt was in his eyes as he stared at it momentarily.

The water running in the sink was cold by now, and he filled the glass up and returned to the table, pulling a chair out and sitting down. After lighting a cigarette he pulled the bottle of whiskey out of his pocket, its brown paper bag rustling. He unscrewed the pint bottle, breaking the seal, and poured more than an inch into the glass. His eyes were tired and he felt vaguely uncomfortable from the wet cold and the standing. Taking a sip glass he set it down away from him on the green table. His boots were pinching his feet, swollen from standing.

He put his hands on the table edge to push his chair back and unlace his boots, but as he did so the table slid suddenly with a screech, and he was jolted to hear the thick glass breaking against the linoleum. "You mother-fucker ... " he said through bitterly gritted teeth, staring down at the shards of glass and the brownish water which spread out in all directions like the points of a star. Almost immediately the whiskey smell came up to him.

He pushed himself to his feet and grabbed a roll of paper towells from the countertop. Pulling off and wadding up a bunch of them he began to mop up the water. As he was swishing it around on the floor, straining to reach across the slivers, he looked up and saw Charlene standing in her long pink robe, staring down at him. Peter saw her shoot one long glance at the pint bottle on the table, still standing undisturbed. A wisp of hair fell down on one side of her face and he saw the concern in her face.

He looked up at her for one moment and then continued to mop the water, saying brusquely:

"I've broken a glass."

"I know," Charlene said in a quiet voice "I heard you upstairs. I thought you might have cut yourself."

"No, it's nothing," he said, dying away. A moment later he said guardedly, "Sorry I woke you up "

"That's alright," Charlene said."I can't sleep very well tonight anyway. Let me help you with that," she said crossing the floor.

"No, I'II get it," Peter said angrilly, and then added, "There's glass over there. You'll cut your feet." She stopped quickly at the tone of his voice and remained staring down at him: He began picking up the larger pieces of glass, placing them gingerly in his palm. When he had gotten all the large pieces he started searching of the smaller ones, squinting his eyes.

"Use a wet paper towell to do that" Charlene said, to his bent head . Peter stood and straightened his aching back. "OK" he said, without emphasis. Looking at her he said,

"Why don't you go back to bed. It's late."

She paused and said hesitatingly, "You coming up?" The extra seconds of silence from him scared her. She waited.

"Yes," he said evenly. A second later he heard her turn and almost immediately she yelled a painful Ow! Peter looked up sharply. She was bent over, holding her right foot, the long roge getting in her way. "Oh God," Peter said What did you do, stop on a piece of glass?" "I told you," he said, crossing over to her "Here, sit down," he said, pulling a chair over to her. She sat down, her face still constricted from the pain. The light robe split over her knees and Peter looked at her soft brown skin and small kneecaps. She bit her lower lip.

"Here, let me see," Peter said, pulling her foot toward him by her ankle. Beneath her little toe he saw a splotch of blood and a small jagged, glinting sliver of glass.

"Now hold still," he said, pulling her foot more toward the light. Charlene felt his harsh grip pinching her skin. Peter pressed in on each side of the sliver with the tips of his fingers and attempted to grasp the glass with his fingernails. Charlene uttered a small gasp and he missed, managing to get a grip on it the second time. "There," he said, looking at the sliver and half holding it up for her to see. He crossed to the garbage pail and flicked in the glass.

"Thanks," Charlene said, holding her foot in her lap . Peter grunted to the wall, "I broke the glass." Her eyes tightened. She said, staring at the blood "Could you bring me a damp paper towell, please?" He moistened a towell and crossed over to her again, holding it out to her. She took it from his hand, her fingers grazing his as she did so. She felt something tighten inside her as a stormy look crossed over Peter's face. He turned back again and began sweeping in the small area in front of her. Still daubing at the blood, looking down, Charlene asked, "How were things at the yard today?" Peter was bent over, scooping the pieces into a dustpan.

"Oh, alright, I guess," he said. "I just nearly lost my job, that's all."

"What?" Charlene cried . "What do you mean, what happened?" The paper towell hung limp in her hands.

"I screwed up a Goddamn supply order" he said. "The bastard nearly fired me."

"Who, Jerry?"

"Yeah, Jerry."

"Well was he really pissed off? I mean, do you think he'll stay mad?"

"How should I know?" Peter said curtly. Lower, he added,"I may not give him the chance."

"You're not thinking of quitting," Charlene said incredulously.

"I don't know what the Hell I'm going to do," he said. "Look, it's late. If I don't get to bed soon I'll never get up in the morning. Why don't you go on up to bed."

Charlene remembered the doctor that day and thought I've got to tell him now. I should have told him when I first felt it. He may not come home after work tomorrow, either. Her worry forced her on and she said in a strained voice: "Is there anything else bothering you, Peter?" Hurriedly she added, "Look, I just don't want you to worry It's not good for you. Peter turned and faced her, his face drawn and haggard. He stared at her and said with a frightening flatness,

"What's bothering you is me having a drink once in a while."

Charlene was shocked.

"No!" she said vehemently. "That's not it at all, I.. "

"Well I've got a life of my own, too, you know," he cut her off viciously. "Peter," she began calmly, almost pleadingly. "I don't mind you having a drink after work."

"No, sure you don't," he said sarcastically. "I see the looks when I come in, like I'm some kind of criminal or something . " Charlene sat straight in the chair and held her head erect, forward.

"Well what do you expect me to think, when all of a sudden you start coming in at all hours of the night, half drunk," she said, her eyes starting.

"Oh now I'm a drunk, am I" he said, in a deadly tone.

"No, I didn't mean that. I'm sorry," she said, slowly, her voice beginning to tremble slightly. I can't let this turn into a fight, she thought.

"It's just that you never drank before, and now all of a sudden you start." She added, "I'm worried about you, that's all."

"Well how about letting me worry about myself, Charlene," he said, leaning back on the edge of the sink and lighting a cigarette. The last one he had lit had burnt untouched in the ashtray, where a near perfect line of ash lay. Staring at the smoke twirling away from the cigarette, he added,

"Though Christ knows I haven't done a very good job of that up to now."

"What ~o you mean by that?" Charlene said sharply. Peter looked at her for a moment and said with a drawn out emphasis, "Do you really want to know?" She did not answer him and waited. He turned to the sink and wrestled another glass from the dish drainer . Stepping forward, he reached for the bottle from the table, filling the glass almost half way with the amber whiskey.

Anticipating the horrible burning in his throat, he threw down half the whiskey at a swallow. The liquid was like fluid fire and he grimaced, his face twisted. He felt a fear too, as he saw his wife waiting, and drew strength from the whiskey and his exterior. Still once he thought, no, I cannot do this. But then Charlene was there, waiting for him to continue. He became even more incensed, and his gut was broiling with the mouthful of whiskey.

"You want to know why I drink?" he began, staring into the brown pool at the bottom of his glass, which was illuminated from the light.

"I'll tell you why, if you really want to know." He paused, and said, "It's because I despise myself." Again he paused, as though spacing each sentence to allow them to sink in.

"And when I drink I can despise myself even more. I despise what I have been, what I am, and especially do I dispise myself when I think what I could have been." He took a smaller sip and continued, the liquid not burning quite so much now:

"Yes, then I hate myself the most. When I think what life could have given me, if I'd only taken it." He stared into the glass "The hatred is so bad, then, Charlene, that it

is less painful to be burnt by this slop, ache from it and vomit it, then it is to face the pain inside." He stopped, and remained staring into the glass. He could feel her eyes on him as he half swiveled and refilled his glass, his hands unsteady and shaking Charlene sat in stunned silence. He looked up to her and said bluntly, "and you didn't know anything about it, did you."

Before Charlene could recover he continued, "No, you didn't. And I guess there are a lot of things about me you don't know. But somehow, and I don't know why or how, I've finally woke up and looked around me." He saw Charlenes's stricken face but continued, "What do I see? I see death in life. I see myself buried in a job that any man could be trained to do in twenty-four hours. A job that at its best is bookkeeping and at its worst is loading lumber in the freezing rain. I see myself in a beat-up duplex that doesn't even make pretensions of being anything more than third rate and for which I'II be paying off the First National Bank for half my life, just like the rest of the morons on this block."

Again he raised the glass to his lips and gulped. He could feel the liquor making his head spin, and a desire to be unconsciously drunk possessed him.

"Oh." Charlene said, with a faraway look, staring down at the floor before his feet. Through tight lips, not looking up or raising her voice, she said, "Is that all?" There was a silent pause and she continued quietly, "Isn't there something else?"

Peter turned to the sink and ran some water into the remaining whiskey, diluting it. He remained staring at it a long while before turning around and again facing his wife. He was about to speak when Charlene said in a subdued tone,

"Then you have found another woman. You don't have to lie to me."

"No, NO!" Peter screamed hoarsly, leaning forward. "Christ can't I make you understand?" He clenched his fists before him, the muscles bulging. "I wish to God it were that simple." He covered his eyes with his free hand and half-sobbed. "I only wish to God it were that simple," he repeated, to himself.

"Charlene," he said, looking up with an agonized expression, "1'm sorry. I have tried, and I have tried, till I'm about to go right out of my head. It won't work. I just can't take anymore of this." He stopped, suddenly tired.

"Our marriage," Charlene began, and drifted away. Still she stared at the floor, her thoughts elsewhere. Peter began again.

"There's nothing between us anymore. We have to face that. I'm sorry it had to be this way, I'm sorry 1've got to do this to you." He added, "I know its more difficult for a woman than a man, he continued. Still she was silent, a pained look on her face.

"Charlene" he pleaded, "say something." He glared at her. She began, "Peter ... l...love you." He half-cried and laughed, downing the whiskey. ''Well in that case, Charlene," he said with an emphasis he did not feel, "It is going to be that much more difficult for you." He saw her through glazed over eyes, sitting there, the long pink robe hiding the chair and draping on the floor.

"You're willing to throw this away," Charlene began carefully, calmly. She could tell the whiskey had its grip on him by now, but she could not stop, she felt she had to know. "Our marriage, our home, our future, everywhere we have made it to by this ·time in our lives All of our work, all of our plans, all the memories we've had together. When I remember ... "

"That's what I hate about you, damnit!" Peter swore, his words slurring viciously. "Your're Goddamn memory, your Goddamn 'I remember when's'. People like you are a curse on the planet, always remembering how good things used to be and refusing to accept change or be honest about the present. It's over. Let's face it! Don't give me any of

your Goddamn memories. I want nothing to do with them. They're like dead wood in your mind. You're better off without them." Charlene saw his body sway to one side as he finished.

"My mind is my own business, Peter" Charlene said. "And if what you're telling me is that we are finished, then you could at least have the decency to listen to me this last time," Peter stared mutely, drunkenly. There was a silence, and Charlene continued.

"You talk about being honest to the present. Yes, I'll admit I didn't know that you felt this way, or at least this badly. And how could I? You never once spoke to me about it, you never once treated me as a confidant or even a friend. Her words were calm and had a tone of finality. "Instead all you have done is turn me off completely like I was some kind of machine. You just tuned me out and started drinking to assuage your conscience, and forget the problem. I don't call that honesty, in fact I think it's the worst kind of lying."

"Lying?" Peter said. "Yeah, maybe that's just what I am, a liar, if you insist. But I know the truth about one thing, Charlene." Peter felt the desire to win this argument-he felt the desire to win once and for all and have it over and done with, win now conclusively, and if necessary, ruthlessly. He said, "And that is that I made those memories. Yes, Yes!" he continued, his voice rising louder and more hoarsley, "I made them, Charlene, and I can unmake them, if I have to."

Charlene continued, almost as if he hadn't spoken:

"I haven't lived with you for this long and not learned something about you. You set yourself up as though you were creator and destroyer, and whenever you don't like something you think you can just undo it. Well it doesn't work that way. But contrary to what you say about me interfering in your life, I was quiet and tried to help you in other ways. Though you ought to know that you 're not an easy person to Iive with, and I've found myself wishing for something more too at times."

Peter stood leaning forward, his eyes glassy, clutching the glass in front of him. Charlene said, looking up to him, "Maybe you are searching for something, and maybe this isn't it. Maybe this doesn't satisfy you, but it's not nearly as sordid and useless as you say. But it seems as though you've made up your mind without me and apparently you don't want to attempt to talk about it anymore. Alright. If that's the way you want it, I'm not going to stand in your way. But I'm going to do more for you than you would probably do for me, because I think I do, indeed, love you'.' Peter lifted his head heavily and stared. "I'm going to wait. I'm going to give you the opportunity to come back, should you ever decide it's what you want. Because you are the worst kind of idealist, Peter. You are a perfectionist. You refuse to believe that there should be problems. But no matter how much you think you can, you cannot cast somethings aside. Some things are born, created, and grow, and you can't stop it."

Peter crossed to the table, carrying the glass and the pint bottle, which was by this time empty past the top of the label. Sloppily he pulled out one of the chairs, its aluminum legs clanking against the leg of the table. He sat, now a few feet away from his wife, and there was a dull glint of frightened shock in his watery eyes.

"The worst thing about it, Peter," Charlene said, "Is that you are really hurting yourself worse than anybody. I've seen that. Because you are carrying around a huge guilt complex. No matter what you may think, however, I am able to take care of myself. And so you don't need to worry about me. i was alone before you came into my life and I can be alone again."

They both trailed into silence, and stared at one another for many moments. The silence under the flourescent light seemed to illustrate the late hour. Peter broke his gaze from Charlene's face and said huskily,"! gave you my blood, Charlene."

"I know you did, Peter," she said, "even more than you do. That's why I'm giving you time. I'll spend it in asking myself if you ever really loved me in the first place." She added softly, "because I don't think you even know."

She got up slowly, and favoring the cut foot, disappeared into the darkness of the living room and was heard going up the stairs. Peter lifted his glass and took a long sip. The pain drew tears to his eyes and he held the glass before his eyes, staring. His face began to contort involuntarily and his breathing became faster and faster. As the first tears began to trickle down his face he murmered into the brown substance in the glass, "I did." His chin trembled uncontrollably as the placed the glass down and held his hand to his face.

"I did," he said more loudly, a second time, his voice constricted and strange. With a great sob he collapsed on the table in front of him in uncontrollable tears, crying, "Jesus Christ, I did."

Thomas Hurst '7 5

October 17, 1973 for somebody else

accepted your projection of solidityuntil object substantiated image and the trust of my fragile, crushing burden Fell through a paper screen. If the heart would have calmed for one moment of reason before the mind abandoned the final column of self-support, Wouldn't I have realized - ? The man strong enough to cast a facade of brick j and mortar

Has no need of one.

Ann Dickenson

thi sisth ekindo

fda

yiha dtoda y thin

gsjus

tdid n'tg

otoget her iti sal lmi

xedup wit hnoth

ingma kin gsen se buti tcoul d'vebe enif

ikne whow

toputittogether

Josh Wertheimer ( '7 5)

Life, C.S. Lewis, Etcetera (In Rememberance of Life B.C.)

Sorting through the crevices of skulls and the ameoba-1 ike uncertainty of day to day drudgery, am totally bewildered, confused, floating without boundaries to provide a form for my identity. No exit.

I'm caught in a whirlwind which tosses about my hair in windswept electricity and erodes valleys in my brain.

The dictionary calls this life, but what do you label it, Dr. Lewis? Oxford cloisters sheltered your body but not your soul as it embarked on its pilgrimage from Nietzchean chambers to Bethlehem stables.

I can sit here and speculate for eternity, But maybe I don't have eternity ... just now?

I can pretend I don't exist if I want and then there is no need for my questions or for answers.

Still my hand waves a flag colored in red human blood in front of my face, beckoning me to pledge my allegiance to to the human race. I am.

But what comes after that? Etcetera ...

Finally the tombstone closes in upon me ... the questioning halts . . . Life goes on without me. Etcetera.

Julia Courtney Habel '74