UR MEDICINE’S GOLISANO CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL NEWS

1 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

2024 VOL.

1

2024 Miracle Kids | Melina Switzer

Jill Halterman, MD, MPH

Jill Halterman, MD, MPH

I am honored to be the new chair of the Department of Pediatrics and physician-in-chief of Golisano Children’s Hospital. I look forward to building on the legacy of our past leaders and teams who have fostered GCH’s growth and development into the institution it is today, delivering outstanding care for children across the region and helping them reach their full potential.

The last volume of Strong Kids highlighted the value of investing in pediatric health care to ensure the long-term health of children. This year’s “Miracle Kids” issue is a perfect example of how investments in pediatrics have paid off here in the Finger Lakes region. Novel treatments and procedures that were not available ten or even five years ago, paired with the dedication and expertise of our caregivers, are now curing our sickest children and improving their long-term quality of life. Whether about improved survival rates for extremely pre-term infants, safe and effective bone-marrow transplant cures for patients with sickle cell disease, state-of-the-art gene therapies being developed by our research teams, or gastrointestinal motility testing, the stories in this issue illustrate the incredible progress we’ve made here in Rochester in delivering the highest quality of care for children.

It is important to remember, however, that many children still lack optimal access to care, and, therefore, our job is only half-done. As chair, my goal is to expand initiatives that are focused on moving beyond our hospital walls and to serve children in historically marginalized communities in both urban and rural areas. We’ve proven that we can deliver outstanding clinical care to children with the most complicated illnesses, yet we must also address the myriad barriers some of these children face in securing regular and reliable treatment. Similar challenges exist for children needing routine check-ups, vaccinations, mental health and wellness screenings and lead testing, and we must focus on developing solutions that ensure equitable access to these critically important services. The tools to address these challenges—from collaborative community events and partnerships with schools and neighborhood organizations to mobile health vehicles to meet families where they are—have been proven to work, and with a collective effort to scale these resources up, we can provide both the preventive and acute care to truly help all children reach their full potential.

During the course of the year, I’m looking forward to sharing more of our plan to address health equity as we refine our strategic direction. There’s a lot to be proud of in our recent history; it is my goal to not rest on these accomplishments and to continue to make an impact on our community.

Golisano Children’s Hospital Board of Directors

Kim McCluski, Board Chair*

Daan Braveman

Mike Buckley, Esq

Steve Carl

Jeffery Davis

Lauren Dixon

Roger Friedlander

Jay Gelb

Mike Goonan*

Deborah Haen

John Halleran

James Hammer

Howard Jacobson

Todd Levine

Scott Marshall*

Gary Mauro*

Kathy Parrinello, RN, PhD

Brian Pasley

Ann Pettinella

Jennifer Ralph*

Molly Branch-Shill

Mark Siewert*

Mike Smith*

Steven Terrigino

Truman Tolefree

Donald Tomeny

James Vazzana

Alan Wood

Kathy York

Bruce B Zicari II

Faculty

Jeffrey Andolina, MD, MS

Marjorie Arca, MD

Susan Bezek, MS, RN

Jill Cholette, MD

Anjana Kundu , MD, ABHIM, FAAP

Michael Scharf, MD

Laurie Steiner, MD

Honorary Members

Michael Amalfi

Bradford C Berk, MD, PhD

Al Chesonis

Judy Columbus

John L DiMarco II

Wanda Edgcomb

Harvey Erdle

Nick Juskiw

Richard Kreipe, MD

Elizabeth R McAnarney, MD*

Dante Pennacchia

Gail Riggs, PhD

Ex-Officio

Kellie Anderson*

Steven Goldstein

Claire Haen

Jill Halterman, MD, MPH*

Jennifer Johnson

David C Linehan, MD

Douglas Phillips

R Scott Rasmussen*

JoAnne Ryan

*Executive Committee

2 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

2024 Miracle Kids

Melina Switzer p. 5

Remi Anthony p. 9

Adaramola Olasumboye p. 13

Maddilyn Wilber p. 17

Isabel Vazquez-Mercado p. 21

5 3 1 2 4 1 2 3 4 5 3 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

photos by John Schlia

Miracle Kid 4 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Melina Switzer

How a determined spirit, plus advances in care here in Rochester, have helped a young girl pull through—despite a debilitating intestinal condition

By Scott Hesel

Melina Switzer is full of boundless energy.

The 12-year-old spends a good portion of her free time at the Warrior Factory in Rochester, looking to earn her Ninja bands. During these courses, participants build their physical strength, endurance, and agility by engaging in a number of acrobatic exercises. Melina is fully immersed.

Sometimes, however, her days at the gym end short. Her chronic pain—concentrated in her intestinal area—acts up, and she calls her parents after 20 minutes. It’s a constant concern that follows her everywhere, from the Warrior Gym to her other activities, such as participating in the Greece marching band and serving in the Youth Worship Group at her church.

“She doesn’t want her condition to disrupt her life,” said Kelley Switzer, Melina’s mom. “She will participate as long as she can to keep active as a distraction from the discomfort.”

This discomfort—which can keep Melina out of school two to three days a month—reflects a decade-long battle to treat Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction. While Melina still struggles today, it’s nothing compared to what she’s been through, and thanks to new treatments and technology here at GCH, there’s reason to be optimistic for the future.

Problems with Eating—from Minor to Emergency

Melina was born prematurely, but her early years were normal. Her physical and mental development stayed on track. The only early warning sign was that she was a little difficult to feed.

“She always seemed to have a slow gut, but the signs were hard to notice at first,” said Kelley.

The serious health issues began at age three, around the time of potty training. First, Kelly noticed Melina’s decreased desire for eating. Then, Melina started experiencing significant abdominal pain.

Kelley took Melina to the Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (GI) at GCH, where she was seen by Rebecca Abell, DO, a junior attending physician in the division who now serves as chief.

5 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

“She first presented to our practice, when she was three, with persistent constipation. The constipation worsened and worsened, despite using every type of medicine we had available,” said Abell. “Eventually, due to her abdominal pain, vomiting, and distention, we got to the point where she couldn’t even tolerate food.”

On the surface, Melina’s case seemed like a bowel obstruction that was preventing food, fluid, and air from moving through the stomach and intestines, but there was no actual physical blockage seen on imaging. So, Melina’s condition remained a mystery. Meanwhile, her health continued to deteriorate. Eventually, Melina was unable to feed by mouth and needed a nasogastric (NG) tube, which is placed through the nose and down the esophagus to provide liquid nutrition. Her condition continued to decline until she could no longer tolerate NG feeds, and her intestines were not able to absorb the nutrients she needed. She required a central line (a venous catheter) for total parenteral nutrition (TPN). At her worst point, she experienced continued visits to the ER for vomiting up to four to five times per day and concern about central line infections.

Yet even through these worst days, Melina displayed a fierce spirit, someone who—in the words of her mother—would go to the doctor and be told that “she looks fine.”

“We struggled with the balance of trying to shelter Melina and mediate the risk of infection and provide as much of a normal childhood as possible, which she always wanted,” said Kelley.

Given that there was no physical obstruction, the working theory was that a part of Melina’s digestive system simply wasn’t functioning, due to either a nerve or muscle issue. Only motility testing—an advanced procedure that examines how both the small and large intestines move— would be the most likely method of diagnosing Melina’s condition. Unfortunately, this testing is only performed at a limited number of centers, and Melina was placed on a nine-month waiting list for the procedure at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“There were only two places in the country who could offer this service to us,” said Kelley. “It was defeating to have to wait that long for our daughter.”

A Steady Recovery

After the long wait, Melina met with Alejandro Flores, MD, director and chair, Ambulatory Community Services, and attending physician in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at Boston Children’s Hospital, for the test. Since Flores had served as a mentor to Abell during her training, there was effective communication between both institutions.

“They found that while the small intestine was functioning fine, the large intestine wasn’t functioning at all,” said Abell. “The nerves in the large intestine were no longer working, and there was no movement on her motility testing.”

While the diagnosis provided clarity to the Switzer family, Melina’s road to recovery would be anything but smooth. The process would start with an ileostomy, a surgical procedure in which the ileum, the lowest part of the small intestine, is brought through the abdominal wall to create a stoma, which is an opening on the surface of the abdomen that allows waste to bypass the colon and exit the body into a bag.

After the ileostomy, Melina would have to wait two years for her intestines to rest, then undergo an additional motility test to see if the nerves of her large intestines had recovered, in which case an additional

6 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

surgery would be required to reconnect the intestines to the colon and start the transition back to regular feeding and digestion.

Fortunately, the ileostomy could be performed back home in Rochester and was done successfully by Chris Gitzelmann, MD, at the time a pediatric surgeon at GCH. While Melina still had a long way to go, the initial improvement was significant; she could now move off TPN and receive feeding through a gastrostomy tube (G-tube), which is inserted through the belly and brings nutrition directly to the stomach, and she even started taking a little bit of food by mouth.

“Being on TPN provides calories for kids to grow when the GI system cannot absorb nutrients. However, TPN requires a central line, which can potentially lead to bloodstream infections. CIPO can put people at risk for bacteria overgrowth in the gut that could potentially leak into the bloodstream,” said Abell. “Melina’s surgery helped to get her off of TPN so that we could prevent that risk.”

After two years, the Switzer family arranged for another motility test in Boston with Flores. The test revealed good news: Melina’s large intestine appeared to be working again, allowing food and fluids to move through the intestine as needed. Melina returned to Rochester for surgery at GCH to re-attach her large intestine to her small intestine and begin the process of full recovery.

Throughout all of these years, Melina experienced chronic pain from the level of stress on her GI system, in addition to the challenges of receiving nutrition through central lines and a G-tube. Her mentality never wavered.

“From a young age, she was the type to never let the pain bother her,” said Kelley. “She always seemed to understand that staying in bed didn’t benefit her.”

A Setback, but Hope for the Future

Melina’s second surgery was successful. During the course of several years after the operation in 2018, Melina started to transition from the G-tube to regular feeding by mouth. While she still needed supplemental G-tube feeding at night and for the occasional bowel clean-outs, her GI system looked to be fully working again.

“After almost a decade of medications, medical tests, and interventions, she was finally living the life of a normal kid,” said Abell.

“We weren’t living in the hospital anymore,” echoed Kelley.

But the story didn’t end there. In 2022, Melina’s chronic pain—always present, even in the best of times—started flaring up more, and the constipation started to return. Around the same time, she tested positive for an asymptomatic COVID infection when she was hospitalized for worsening constipation that needed a bowel clean-out. Both Kelley and Abell wonder if this could have caused some worsening dysmotility.

“We know that COVID can cause GI symptoms, and we’re seeing some evidence that COVID may affect the nerves and the motility of the GI tract, much like other infections can,” said Abell.

Fortunately, with time comes new tools to treat Melina’s condition, and GCH is now better equipped to offer help. First, new drugs have been developed in the past decade that can be utilized to potentially cure non-functioning intestines. Melina is taking one of these drugs right now to stimulate bowel movement, and the results haven’t yet been determined.

If these drugs don’t solve Melina’s issues, she’ll need another motility test. This time, however, there’s a strong chance that she’ll no

“After almost a decade of trying to solve the problem, she was finally living the life of a normal kid.”

longer need to travel to Boston. Thanks to the purchase of new equipment and the hiring of Ajay Rana, MBBS, MS, in the GI division, GCH will have motility-testing capabilities this year. For the first time in her life, Melina will, potentially, have everything she needs here in Rochester.

“Just to know that something is going to become available is really exciting to our family. It’s rare to have this service, and we’ve met many other families locally who are experiencing similar issues and will benefit greatly,” said Kelley.

While there are many questions yet to be answered, it won’t slow down Melina; she’ll be at gym collecting her Ninja bands.

“After all these years, she knows how to manage it herself now,” said Kelley.

7 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Miracle Kid 8 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Remi Anthony

There Is a Light that Never Goes Out

By Terri Medina

In the journey of parenting, unexpected twists can sometimes take us by surprise. One such turn occurred for Mike and Jenny Anthony in 2021 when their daughter, Remi, fell ill at just 18 months old.

What seemed like a routine case of hand, foot, and mouth disease quickly escalated into something more concerning. As a nurse herself, Jenny’s instincts kicked in, leading the couple to seek further medical attention when Remi’s symptoms persisted longer than expected. Little did they know, this decision to seek more care would find them fighting for the life of their young daughter.

The Worst Fears, Confirmed

The Brighton couple had always wanted a family. Jenny was a NICU nurse for more than 15 years and joined Strong Memorial Hospital in 2015. Welcoming their daughter, Remi, in 2019 felt perfect, and those early beginnings were filled with milestones and joy. Remi was in daycare and picking up the usual illnesses that often spread through communal spaces. She was a happy child, full of curiosity and whimsy. She was known for emitting a light that brightened any space she occupied. But she was continually getting sick, and after one too many bouts with illness, the Anthonys were worried. Jenny was pregnant, expecting their son, Gus, and she was committed to keeping everyone healthy.

“We spoke to her pediatrician by phone, and that’s when she was diagnosed with hand, foot, and mouth disease,” said Jenny. “We expected that Remi would recover in a few days. But her fever was so high and persistent that we just didn’t feel right about not having her seen in person.”

Jenny’s medical background and Michael’s attentiveness had the couple on edge. At the hospital, staff were preparing to check for a urinary tract infection, but as a precaution, Jenny asked if they would

9 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

perform labs along with the urinalysis, which wasn’t typical. Her request was granted.

“I think if you don’t know what I know, you wouldn’t think to ask for bloodwork first,” said Jenny. “But I just felt like something wasn’t right. Bloodwork is not the typical step for her presenting symptoms, but I wanted to go that route to rule anything out and check her labs prior to checking urine. The likelihood of it being childhood cancer was low, and my mind wasn’t even considering it a possibility.”

Jenny remembers watching their daughter waiver between listlessness and pep. “Everyone was hoping it was carryover from a previous case of COVID Remi had about a month before, perhaps a post-viral immune response” she said.

While there often is a low chance of bloodwork showing cancer for most people, Jenny had a close family history of leukemia. Her sister, Katlyn Pasley, was diagnosed with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in 2000 as a child, and she succumbed to it that same year.

Unfortunately, the worst-case scenario came true: when the blood work results came back, they showed markers for leukemia, and the Anthonys turned to a pediatric hematologist/ oncologist at GCH.

“Everything was moving so fast at that point. Things got real very quickly for us. Because my sister also had had leukemia, I thought, ‘No way is this happening twice,’” said Jenny.

Over the next few days, the Anthonys would meet with members of Remi’s care team, including Jeffrey Andolina, MD; John Mariano, MD; and their dear friend David Korones, MD, as they navigated the medical challenges the family now faced.

“I remember telling (Mariano), ‘I’m floating right now, and I need you to tell me what to do or what you would do—because I have no idea how to make these decisions,’” said Jenny. “Korones and Mariano guided us to make the decision to go forward with a bone marrow biopsy that morning. It seemed so invasive for our child to go through that, but they explained that it was not as invasive a procedure as we thought, and it would definitively tell us what was going on with our daughter.”

Afterward, when it was confirmed as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Remi was more vibrant than she had been in weeks because she had received blood and fluids. “She’s feeling really good so we’re like, how is this possible?” thought Michael. “How does she have cancer?”

Continued Care and Support

“They told us treatment would last two to three years, and I remember just being floored by this,” he said.

The Anthonys turned to family and friends for support, which came in abundance. About two months prior to Remi’s diagnosis, Jenny’s mom had passed away. The family was still healing, already receiving so much support from the community and loved ones. Jenny recalled feeling an immediate extension of support once again.

“We were like, ‘My God, we need you guys again,’” said Jenny. “We have an incredible community, and they showed up again for us. In the beginning of it, we were slow to let people know and slow to even realize what we were going to need, and they just rose up and answered what we needed without us knowing what we needed. We had financial help, and the meal train started right away and lasted the entire year!”

Mike was researching on his own, trying to understand everything there was to know about ALL, a type of cancer with a good prognosis. “This was all a new and wild frontier for me,” he said, recalling lots of sleepless nights. “We thought it would be a reasonable course of treatment, but Remi was considered high risk due to her family

10 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

history, so that changed her treatment and upped the amount of chemo and intensive treatment she would receive. I had so many questions in that first month we were in the hospital. Everyone was so patient, kind, and helpful.”

The additional stress and anxiety of this issue has made Remi’s case extremely intense and emotional, both for family members and for the health-care team. “I always have an immense responsibility to make sure we are doing everything we can for our patients to receive the best treatments,” said Andolina. “In Remi’s case, I felt significant empathy for the family having to go through treatment for leukemia for a second time.”

The family stated that their support at GCH was incredible. Jenny, who had worked as a traveling nurse at one point in her medical career, said she had never seen a place like the tower at GCH. They had a private room with their daughter, where they stayed every day. While they only live about 10 minutes from the hospital, they did not want to leave and felt comfortable during their stay.

“I was pregnant, so I needed some physical support as well,” she said. “(Mike) kept encouraging me to bring in an air mattress, and I was like, “I don’t know if that’s too invasive,” but the nurses were supportive of it, so I could actually sleep.”

After Jenny gave birth to Gus, Remi had a few unexpected inpatient stays. The staff on 7North allowed the Anthonys to be together as a family during those challenging inpatient stays, for which they are grateful.

“Even in that challenging time of their lives, they always made small moments for one another,” recalled Samantha Chiarella, RN. “They always had a smile on their faces and were always so loving and supportive of each other and all the staff here.”

The Brightest Light in the Tower

“Remi has an engaging and happy personality—she is a favorite of the nurses, for sure,” said Andolina. “My best memories of Remi are her running through the halls of 7North, with her chemotherapy backpack attached!”

Michael recalled how that backpack went everywhere she went for months. “If she was in the car or on the couch, it was right there next to her. If she was sleeping, it was in her crib; eating, it was on her highchair.” He even sewed patches of her favorite characters on it.

Before her mother passed away, Jenny said her mom often referred to Remi as “sunshine.” “She’s just jolly and goes along with everything,” said Jenny. “You really do feel her presence like sunshine.”

Of course, there are tough times, too. Cancer treatment is not without some misery. It is difficult for anyone at any age, but we often wonder why it afflicts such little ones, especially as their lives are just beginning. Korones, a longtime provider and friend of the family, said it can be difficult to meet the emotional needs and psychological needs for everyone involved.

“I took care of Jenny’s sister when she had ALL more than 20 years ago, and I was there the day she died,” Korones said. “It was one of the most shattering losses I have ever experienced. I knew Jenny then, and later, I got to know her even better when she was a nurse on our palliative-care team. She has long been special, a dear and special friend and colleague. My heart breaks a little extra for what she and Mike are going through, and yet they are all so easy to love.”

Today, Remi is three years old and in maintenance mode. According to Andolina, her prognosis is excellent due to her treatment plan on a national protocol, with an added upfront antibody medication, which is expected to help her remain in continued remission.

“People tell you that she won’t remember the pain. But she will remember the love, the hugs, the snuggles.”

“As with all of our patients, our teams and I hope and are doing everything we can to be sure that Remi is cured of her leukemia and that she lives a long and healthy life,” he said.

The family describes this as a bit of an arrival.

“Everyone told us the whole first year to just hold on tight for the maintenance phase,” said Jenny. “Sometimes we were just living day by day; other times, we could operate week by week. Often, we couldn’t schedule or plan anything. You learn a lot about becoming flexible. Now we can do more normal things, and Remi is just thriving. People tell you that she won’t remember the pain, but she will remember the love, the hugs, the snuggles. And we know that to be true. Her light just shines so brightly.”

11 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Miracle Kid 12 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Adaramola Olasumboye

Through pain and perseverance, one family’s journey to transplant triumph

by Kelly Webster

True love and unwavering faith can move mountains, as demonstrated by the Olasumboye family’s remarkable journey with their son, Adaramola, affectionately known as Dara. In the face of adversity, they found strength and hope, ultimately triumphing over sickle cell disease through a life-changing bone marrow transplant.

The Struggles of Sickle Cell

Adewale and Adedoyin are both blood type AS, which means they are carriers of the sickle cell trait. Statistics say that their offspring have a 25 percent chance of having sickle cell disease. Despite their fears, they were encouraged by love and faith, welcoming three children into the world: Yeni, Dara, and Tolu. While Yeni and Tolu were born healthy, baby Dara was diagnosed immediately with the disease. Confronted with the devastating news, Adewale said, “We just have to face the challenge. I’m going to love him and do everything I can to give him a good life.”

Dara’s health issues began when he was only six months old. With sickle cell, blood cells are rigid and crescent-shaped, which causes them to get easily stuck in blood vessels. A “crisis” is when blood flow becomes so blocked in a specific body part that it causes severe pain. Dara had his first crisis at age one. During those early years, Dara had to visit the hospital several times to get through these events. “It was devastating,” said Adedoyin. “As a parent, you do everything you can, but nothing seems to work. It makes your heart ache.” On a more beautiful note, music played a crucial part in helping Dara cope with his condition. “Dara enjoys dancing,” Adewale said, “even if he’s in pain.”

13 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

In 2018, the family moved to Corning, New York. They wanted the best care for Dara. Adewale asked his former doctor for a recommendation and was referred to Golisano Children’s Hospital (GCH), which offers the region’s only Pediatric Hematology program. GCH is a designated National Marrow Donor Program Transplant Center.

Suzie Noronha, MD, a pediatric hematologist, provided a warm welcome for the Olasumboyes. She knows firsthand how her patients can be in and out of the hospital for severe pain. Noronha built a trusting relationship with the family through many visits, answering all of their questions and providing detailed information about all the treatment options available. “Dara’s parents had done their research before coming to us,” Noronha said, “and knew that as children with sickle cell grow into adults, even more complications can develop. Knowing that they wanted to stop Dara’s pain and prevent those future ailments, I turned the conversation to bone marrow transplant. At this point, it’s the only known cure to really get rid of the disease, but of course, it’s not a walk in the park. It’s a journey full of challenges, both physically and emotionally.”

The Defining Moment of Their Lives

Watching your child suffer is excruciating. Simply managing pain through medications wasn’t

enough. Dara’s family longed for a cure. Noronha discussed at length with Dara’s parents the risks of transplant, such as infection or fever. Anyone who receives a transplant can develop graft vs. host disease (GVHD), in which the donor’s immune cells see the recipient’s body as foreign and essentially launch an attack on it, leading to rashes or organ problems. However, it’s less common in younger patients, especially those with a full match to their donor. Ultimately, there is also a very small chance, around 4 percent, of death. Every parent’s worst fear is losing their child.

“It’s really tough for some families to come to terms with these risks, even when the chances are very small,” said Noronha. “But one of the most agonizing realities for anyone who has sickle cell is the relentless, severe pain. It’s such a burden on them. As they grow older, adults can develop even more complications, like liver, kidney, or lung problems. Sadly, this often means adults can be too sick to endure a transplant.” It’s an agonizing process to make medical decisions on behalf of your child, especially when there is no easy answer. Dara’s parents felt that the transplant was the best way to give Dara the life that he deserves.

Once decided, Noronha introduced the family to Jeffrey Andolina, MD, MS, the director of Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation, who prepared the whole family for what was to come. The first step was to find a donor. Typically, siblings are the initial option to consider, since there’s a 25 percent chance they’ll be a full match.

Both of Dara’s sisters were tested, and little Tolu was a perfect match.

How do you talk to a six-year-old about being a bone marrow donor to their big brother? Only members of the family truly know what each other’s values and beliefs are, so Andolina and Noronha offered guidance to the parents, then Mom and Dad had the delicate talk with Tolu. Adewale was impressed with her and how mature she was. “I can save him?” she asked with a smile on her face. “Yes, I’ll do it!”

Andolina notes that every donor will have their own transplant team to specifically advocate for them. “It’s also perfectly safe,” he said. “The donor’s bone marrow grows right back after a few weeks.” If there was any doubt a donor didn’t want to participate, they would not move forward. But Tolu, the loving little sister, was actually excited to help her big brother. Adedoyin recalls how supportive Andolina was. “He was always available for us. We could connect with him anytime to ask questions.”

The transplant process spans several stages. Dara, now eight years old, braved extensive preparation as he was admitted to GCH for a one-week, pre-transplant stay. He had a Mediport implanted into his chest, where the bone marrow will be inserted later. He received a series of transfusions to remove as much sickle cell blood as possible and replace it with healthy blood. This helps reduce the number of unhealthy cells in his body during the transplant. Dara also went through chemotherapy for a week. This essentially eliminated his own bone marrow that produced those sickle cells and wiped out his immune system, allowing his body to accept the new bone marrow.

With Dara prepared, it was time to bring in Tolu and perform the actual transplant. On May 17, 2023, half a liter of bone marrow was taken out from her hip. When the medical bag was brought into Dara’s room, he exclaimed, “Is that my sister’s blood? How is she? I want to see her!” Her bone marrow was then slowly injected into Dara’s Mediport over an hour. Andolina said, “The stem cells in the donor bone marrow get into Dara’s bloodstream, then they know to home in and go into his bones and start growing new blood.”

The hospital was Dara’s whole world as days stretched into weeks for his recovery. Time seemed to stand still as he missed his own bed and playing with his friends from home. His parents were torn between the anguish of seeing him hospitalized and the hope that this was the cure that would forever change Dara’s life. Their spirits

14 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

never faltered, though, and they all remained resilient through their unwavering faith and love for each other.

“It was a defining moment in our lives,” said Adewale. “We were so anxious and wanted to make sure Dara was OK during all of this. Not only was he going through so much physically, the emotional toll of being away from home for a month was rough on him. But our medical team did an amazing job. They loved Dara, they gave him a lot of care and attention, which helped keep him smiling.” Because their hometown is an hourand-a-half drive away, the hospital arranged for the family to stay at local hotel for six weeks after the transplant to be close to Dara as he recovered. Once he was able to leave the hospital, he still visited the clinic for checkups several days a week.

Having Hope and Health

Andolina reflects on how it was the perfect transplant. “It went smoothly for three reasons. One, Dara was otherwise a pretty healthy kid; he had no other complications. Two, we had a perfectly matched donor with Tolu. And three, they were a really focused, reliable family that did everything asked of them. Dara took all his medications, came to all his appointments, and that’s a huge credit to Mom and Dad.”

It is now one year later, and Dara is doing wonderfully! After spending the summer recovering and gaining strength, he went back to school with new enthusiasm and is excited to get involved in sports. He is, essentially, cured. Sometimes, Dara will say, “Daddy, can we go say hello to my nurses?” Adedoyin reflects that the nurses were so supportive, they became like friends and family.

Breathing a sigh of relief now that Dara is healthy and living his best life, Adewale and Adedoyin want to help others who are facing this disease. Back in their home country, Nigeria, babies born with sickle cell disease are often helpless. The Olasumboyes are working on starting a foundation to help those babies. The program will educate people on sickle cell disease: how to manage the condition and how to find the cure if they get a match. Adewale said, “As Dara grows up, he’ll have something incredible to commit himself to.” As this family knows, having true love and faith can work wonders.

“Breathing a sigh of relief now that Dara is healthy and living his best life.”

15 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Miracle Kid 16 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Maddilyn Wilber

From a devastating diagnosis at birth, to a life full of laughter

By Barbara Ficarra

For Adrianne and Brandon Wilber, the joy of welcoming their daughter, Maddilyn, was soon mixed with worry and uncertainty. It started the day after she was born in November 2019, when Maddilyn failed her newborn hearing test.

Sometimes newborns just have fluid in their ears, and a repeat test shows all is well. But when Maddilyn failed a second time, Adrianne and Brandon were concerned.

“I had a mother’s intuition that something wasn’t right,” Adrianne remembers.

A third, more precise evaluation called the Auditory Brainstem Response Test—which measures a baby’s brain waves in response to sound—confirmed that Maddilyn had profound hearing loss.

It was devastating news for the Wilbers and Maddilyn’s eight-year-old brother, Chase.

“At the beginning, it was very scary,” Brandon says.

“You think about things as a parent—like, I love music; will she ever be able to experience that with me? What about school? How do I tell her brother that your sister can’t hear you, and you’re going to have to learn another language? There are a lot of things we were very concerned about,” Adrianne adds.

As bad as things looked, there was even worse news to come.

Additional Risks—and an Important Decision

Following diagnosis of a hearing problem in infants, it’s common for providers to recommend genetic testing and a consultation with an ophthalmologist to see if there are issues with the eyes, since many disorders affect both.

17 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

The Wilbers were referred to Jenina Capasso and Lindsay Adamczak, genetic counselors at University of Rochester Medical Center. Capasso and Adamczak conducted an in-depth analysis of the health history in Adrianne and Brandon’s families and ran genetic tests on Adrianne and Brandon.

Their work revealed that Maddilyn has Usher Syndrome, a rare genetic disease that can cause deafness or hearing deficits at birth, and later in life, progressive loss of eyesight. The vision loss typically starts in the second or third decade of life and begins with loss of night vision, followed by peripheral (side) vision. Ultimately, the patient’s field of vision narrows until they have only central, or tunnel, vision. After this diagnosis, the Wilbers were referred to Dr. Alex Levin, an ophthalmologist and ocular genetics researcher.

Knowing that vision loss could impact Maddilyn’s ability to read lips and use American Sign Language to communicate, the Wilbers focused on giving their baby every option available to improve her hearing.

“The first step was to try hearing aids for Maddi, but they didn’t notice a difference with them. My husband and I were crying. Knowing your child can’t hear—it’s a grieving process,” says Adrianne.

The Wilbers reached out to Dr. John Faria, a pediatric ear, nose, and throat physician at Golisano Children’s Hospital. Faria treats a variety of childhood ENT conditions and performs most of the cochlear implant surgeries for children in Rochester and Buffalo.

Not all families choose to treat a child’s hearing loss, Faria notes.

“Rochester has one of largest culturally deaf communities in the nation; I see families that don’t see being deaf as a problem at all, and that’s totally fine. Other families consider it something they want to treat. Usually, the first thing I ask a family is, ‘How do you want your child to communicate?’”

For the Wilbers, Maddilyn’s potential vision loss was one factor in their decision to use technology to augment their daughter’s hearing. Another was the knowledge that if they waited too long, cochlear implants wouldn’t even be an option.

“The brain changes the way sound is processed if a child is not exposed to sound for a long time,” Faria says. In other words, there was a window of time in which Maddilyn could acquire the ability to understand and respond to spoken language.

“We wanted to help her hear with implants, to learn English and be integrated in a general-education classroom with her hearing peers; then later on down the road, if she decides she wants to be completely deaf, she has that option,” said Adrianne.

Successful Surgery and Living Life to the Fullest

Maddilyn had an audiologist for the hearing aids trial and later switched to Megan Wightman, AuD, a senior audiologist with URMC’s Otolaryngology (ENT) Department, who works with cochlear implant patients.

Faria did the cochlear implant surgery when Maddilyn was one year old.

Cochlear implants include an internal processor surgically implanted behind each ear and an external processor that sits on the outside of the skull and is attached to the internal device via magnets. It communicates with the internal device so that electrical signals can stimulate the cochlea to receive sound.

Wightman worked with Maddilyn to adjust her implants and ensure she had access to all the sound they can deliver.

18 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Success comes from “consistent use, speech, and language therapy,” Wightman says. “It’s a lot of work. Maddi’s parents were extraordinarily involved and have done a great job with her.”

On top of all that work for Maddilyn and her parents, the little girl faced other health setbacks. As an infant, she returned to the NICU for two days with jaundice. She had severe RSV at two months. Faria twice placed tubes in her ears for recurrent infections and removed her tonsils and adenoids because of frequent bouts of strep throat. Maddilyn now experiences headaches and is receiving treatment for them.

But the biggest challenge was her near-deafness and its effect on her language development.

“She went a year and three months before she could hear anything,” Adrianne says. “All that language and development she missed out on. She was seeing a teacher of the deaf and a speech therapist, Megan, and a social worker who was helping link her with services.”

When it came time for preschool, Maddilyn went into pre-K in a general-education room—having had an Individualized Education Program (IEP) developed—and never looked back.

“She has now made up for all of her language delay,” Adrianne says proudly. “She still sees a speech therapist and a teacher of the deaf regularly at school, and she is right on par with all her hearing classmates. She has not let any of this stop her.”

Even better, it hasn’t seemed to interfere with her being a happy, inquisitive, and outgoing child.

“She’s still a regular and crazy four-year-old!” Adrianne says. “She probably knows even a little above her age level because what she doesn’t know in speech, she knows in sign. If she’s not sure in words, she uses sign—it’s amazing.”

“It is really impressive because with cochlear implants, you would never know now that a child is deaf,” says Wightman. “Maddilyn is a little superstar with her implants.”

that gene—the protein needed for proper ear and eye function—is not there to do its job.”

“She still sees a speech therapist and a teacher of the deaf regularly at school, and she is right on par with all her hearing classmates.”

“She is sassy,” Adrianne says. “She is the embodiment of sassy, and she is a determined little thing. If she doesn’t want to do something, or if she does, you’re going to know about it, and you’re going to have a hard time stopping her!”

When it comes to a favorite hobby, Adrianne can’t narrow it to one.

“What doesn’t that kid like to do? My fear of her not being able to enjoy music? Right out the window. She likes to dance like no one is watching; she loves listening to music and singing, being outdoors. Her animals. Spending time with her brother and cousins. She likes roller skating and is very proud of herself that she wins the limbo every time.”

Cracking the Genetic Code

The technology that can provide hearing to a child born without it is a miracle. When it comes to Usher Syndrome, however, there’s another miracle in the works at URMC and other ocular-genetics research centers around the country.

“Maddilyn has an abnormality in the gene USH2A, the second-most common genetic disorder of the retina and most common cause of Usher syndrome,” Levin notes.

“The gene in question for Maddilyn is a very important one that tells the ear and the eye to work. And if that gene isn’t working, the product of

Up until now, patients with Usher Syndrome who experience vision loss could only receive help with, not a cure for, their vision symptoms. But, Levin says, “Thanks to the ocular genetics research under way today, including here at URMC, I would say the chance of this child losing her sight is almost zero. We and others are already working on treatments to deliver gene therapy to those with Usher Syndrome, and before Maddilyn even has a single symptom, it’s almost certain that gene therapy will be available to her.”

The first gene therapy in the human body was approved by the FDA in 2017 to treat an eye disorder—Leber Congenital Amaurosis—a type of hereditary retinal dystrophy caused by abnormalities in the RPE65 gene.

“There are now 16 sites in the United States that are allowed to administer that gene therapy, and URMC is one of them,” Levin says. “The treatment has restored sight for children legally blind at birth.”

This gene therapy uses the virus that causes the common cold to instead transport a functioning gene to the eye to treat retinal dystrophy. The USH2A gene is too large to fit into the cold virus, so an alternate carrier is still being developed, Levin explains.

“Once that is tackled, Maddilyn would be a great candidate. We’re doing research to hopefully start clinical trials for her gene in collaboration with the University of Iowa. When gene therapy is ready for her particular disease, we’ll provide the treatment right here for her, most likely before she ever experiences a visual symptom.”

Miracles on top of miracles—and one less thing Maddilyn will have to overcome. Now she can focus on that next limbo contest—and living her young life to the fullest.

19 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Miracle Kid

Isabel Vazquez-Mercado

A collective effort from caregivers and family help an extremely pre-term infant overcome long odds of survival.

By Kiara Warren

Bringing a child into the world is a momentous occasion, a culmination of months of anticipation, preparation, and hope.

For parents of premature babies, this period of life can feel much like an emotional rollercoaster, especially when pregnancy complications can cause birth to take an unexpected turn and defy the conventional experience.

For first-time parents Claritza Mercado Rosa and John Michael Vazquez Vargas, the birth of their daughter, Isabel Ruby Vazquez Mercado, was filled with unpredictable complexities and challenges.

It started when Claritza began to experience some pain and discomfort during the second trimester of her pregnancy. While attending an appointment for a routine anatomy scan at around 20 weeks, physicians sent Claritza to labor and delivery for additional testing and observation. Initially, they wanted to be sure that everything was okay, given the symptoms she had been experiencing at home; however, upon examination they realized that she was already dilating, and things took an abrupt turn.

An Unexpected Arrival

Claritza’s care team sprang into immediate action.

Physicians had hoped to perform a cervical cerclage to keep her from dilating further and delay labor to better Isabel’s chances of survival, but quickly realized that she had dilated to 5 cm and that she no longer qualified for the procedure.

At this point, John and Claritza were given their odds: Babies born before 22 weeks typically have a 5 percent or less chance of survival and are not currently eligible for resuscitation in New York State; however, those chances improve each week until delivery. Claritza was kept in the hospital on full bed rest to delay labor.

21 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

At about 21 1/2 weeks, after Claritza had been in the hospital almost two weeks, physicians decided to transfer the Mercado-Vazquez family to Strong Memorial Hospital. Shortly after their arrival, Claritza delivered Isabel—on the very night she made the 22-week mark.

Due to Isabel’s extreme prematurity, Claritza was administered a host of medications aimed at bolstering Isabel’s chances of survival, including a steroid shot to help with her lung development.

As the night progressed, Isabel gradually descended into the birth canal, signaling her readiness to enter the world. On March 25, Isabel was born via an emergency C-section, weighing one pound; she was a fighter from the very beginning—displaying a strength and resilience that belied her tiny size.

The reality of Isabel’s premature birth shattered Claritza’s and John’s expectations, leaving them grappling with the overwhelming emotions of shock and worry. It was the beginning of a journey filled with unexpected twists and turns as the new parents learned to navigate the unfamiliar terrain of the GCH Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

“I call it a rollercoaster; we got off one ride and went to the next. There were a lot of small goals—feedings, weight gain, breathing on her own, hoping,“ said Claritza. ”It is something that

you cannot prepare for. I don’t imagine what it would be like losing her—I don’t even think about it.”

Defying the Odds

Isabel was vulnerable to a host of severe health complications affecting her body’s major systems. Because of her extreme prematurity, she was included in the small-baby program in the NICU, where she had an additional team rounding on her to evaluate and monitor her progress closely and to also make sure John’s and Claritza’s needs were being met.

Colby Day Richardson, MD, neonatologist and medical director of the NICU, describes the small-baby program as “an incredible addition to our clinical care made possible by the dedication of a multidisciplinary team, with the goals of improving outcomes in some of our most vulnerable patients and focusing on supporting and empowering our families at the same time.”

Isabel’s lungs were underdeveloped when she was born, leading to Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), a form of chronic lung disease that affects premature babies. From the time she was born, Isabel required the support of high-frequency and conventional ventilators to breathe.

“She was up and down on the ventilators; she would move to another one but then need higher support again later that night. It was a true balancing act between the ventilator supports and medications.” said Claritza. “I was numb but I didn’t want to show her my weakness; she was showing us she was strong, and so I wanted her to know that we were strong, too. “

Due to the severity of her breathing complications and an esophageal perforation, Isabel was unable to work on feeding by mouth for several weeks. Once she was able to reduce the level of ventilator and oxygen support, she started trialing feeds with milk on cotton swabs and received most of her nutrition through a nasogastric tube (NG tube) that ran down her throat and into her abdomen.

It was not long, however, before Isabel’s care team noticed that she was struggling with feeding. Her abdomen would turn black, and she was unable to suckle and swallow effectively, leading to feeding difficulties and failure to thrive. Additional testing and imaging revealed that Isabel was suffering from Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC). NEC is a

serious gastrointestinal infection in which the infant’s intestinal tissue becomes inflamed and could become perforated, causing it not to function appropriately and affecting their bowel movements.

“Isabel’s weight gain was up and down a lot. Getting the right balance was tough, and she was not pooping like she should, so we did not want to ramp up feeding, but she wasn’t gaining good weight,” said Claritza.

On April 5, Isabel’s care team performed an emergency bowel resection surgery to remove the dead tissue from her intestines and placed an ostomy bag to help with bowel movements. These procedures would help her better tolerate feeding and digestion and support her ability to gain weight in the NICU.

“I remember speaking with someone who had gone through a comparable situation and the baby didn’t make it,” said Claritza. “I remembered how blessed we were that we took the 10% chance of survival and that she was still here with us. We wanted to grab her and hold her, and we couldn’t most of the time—but we didn’t give up, and neither did she.”

John and Claritza remained steadfast advocates for Isabel. They alternated their disability time between them so that they could be sure that someone was always available to be with her and quietly bond once her respiratory support allowed them to hold her and engage in skin-to-skin care.

“We are a small local family. Our parents live in Puerto Rico, so it was important for us to be present for Isabel,” said Claritza. “In the beginning I would go during the day, and John would go at night; once I went back to work, we switched, and John would go during the day.”

Skin-to-skin care, also known as kangaroo care, can be one of the most important aspects of an infant’s wellbeing in the NICU. Studies have shown that skin-to-skin care improves outcomes for premature babies: It supports temperature regulation, growth and neurodevelopment, sleep quality and feeding, and decreases infant stress, length of stay, and mortality.

“We know, based on evidence, that skinto-skin care provides a large number of medical benefits both to families and to the infants in our unit,” said Richardson. “In the NICU, we are committed to promoting skin-to-skin care as part of our mission to provide optimal health care to our infants and their families.”

22 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Persistence was a key factor in Isabel’s journey. Claritza and John would attend smallbaby rounds, ask questions, and serve as active members of their infant’s care team.

“We were fortunate enough to have a wonderful team that supported us along the way; every little step she would take meant a lot. It made us feel that she was going down the right path. We celebrated any small moments,” said Claritza.

The Greatest Gift

As the months went on, Isabel continued to grow and improve. She was making strides with feeding, and her lungs continued to get stronger. In July, she was extubated, and physicians decided that it would be okay for her to trial off oxygen support; by August Isabel no longer required any respiratory or IV support.

Finally, Isabel was close to going home with her family and had just two tasks left to accomplish before she could be discharged: surgery to reconnect her intestines, and she needed to be able to drink from the bottle without relying completely on her NG tube.

John and Claritza were offered the option of doing NG tube feeds at home, but they preferred to give her some extra time to grow and learn to feed by mouth. Ultimately, Isabel did just that and was discharged to home—taking all of her feeds on her own—on September 5, in time for John’s birthday.

“Isabel’s parents were amazing at being at bedside. They integrated themselves into her care from the very beginning, which is hugely beneficial to a premature baby’s development as well as the transition home,” said Richardson. “It’s nice to see a baby born so early doing so well.”

Though Isabel continues to manage some minor conditions associated with her extreme prematurity, she does not require any major supports at home. She has had followup appointments with pediatric specialists in pulmonology, gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition and has undergone multiple procedures with ophthalmology to address retinopathy. Additionally, she receives care from Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics to address some developmental delays. Despite the hurdles in her journey, she is making strides and preparing to embrace the world ahead.

“We were fortunate enough to have a wonderful team that supported us along the way; every little step she would take meant a lot”

23 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Miracle Maker Award for Outstanding Commitment by a Healthcare Provider Sue Bezek

After more than 45 years serving as a nurse, a nurse practitioner, and a nursing leader at URMC, Sue Bezek, the chief nursing officer at Golisano Children’s Hospital, will be retiring.

Her career has been defined–from the very beginning–by a philosophy that emphasizes putting the needs of patients and families first.

“Making a difference for people who were struggling with their health is what drew me in to the field,” she said.

It didn’t take long for Bezek to find a path in nursing that enabled her to fulfill this goal. While earning her BSN from Villa Maria College, Bezek became enamored with pediatrics during one of her training rotations as a student nurse. Her first nursing position was on the Infant and Toddler unit (4-1600) at Strong Memorial

Hospital (SMH). After a year on that unit, she sought to augment her clinical skills in a pediatric intensive-care area and transferred to the NICU.

Soon after her transition to the NICU, she was elevated to the position of nurse leader. “I think I was somebody who had an affinity for problem solving, but I still had to grow my skills to navigate the challenges of leadership,” she said.

One of these challenges was earning the trust and respect of her peers after being promoted into leadership so early in her career. Bezek accomplished this by emphasizing collaborative problem solving with her team.

“I would approach an issue and offer to the team: ‘Here’s how I think we could solve it, would you do it this way? How can we collaborate in finding solutions?’”

After two-and-a-half years in this position, Bezek took on a new role when the URMC Ambulatory Surgical Center opened in December of 1984. Bezek served as a Level II staff nurse, and was the only nurse on staff who had previous experience in pediatrics.

Bezek’s three years in that position offered a great experience to learn about patients and clinicians across the URMC system, all while serving as a resource for her peers about pediatric care. “I learned skills from my colleagues about caring for adult patients but also helped them learn about the care of children,” she said.

While working at the ambulatory center, Bezek began her pursuit of an advanced educational degree in nursing and received a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner degree from the University of Rochester. She subsequently transitioned to serving as a Nurse

Practitioner (NP) in various Pediatric Divisions – in progressively more responsible roles.

Throughout these roles – from serving as the first PNP in the new Pediatric HIV Program and then as a PNP in the Pediatric Primary Care Practice, to eventually ascending to senior leadership at GCH –Bezek has been guided by words of Dr. Elizabeth McAnarney, former chair of the Department of Pediatrics.

“She told me: ‘If you keep your decisions focused on the right thing to do for the patient and family, all the other things will fall into place,’” said Bezek.

Bezek applied this approach at every level, first as a practicing NP serving patients directly, then in subsequent leadership roles as a senior nurse manager of the Outpatient clinic, followed by associate director of the Sovie Center for Advanced Practice, and subsequently, the director of pediatric nursing and then the inaugural Chief Nursing Officer for Golisano Children’s Hospital.

“In leadership, you don’t necessarily see your impact on a patient-to-patient basis, so you have to really listen to your team, who have these day-to-day experiences with patients and their families, and do collaborative problem solving while trusting their perspective,” she said. This teamfocused collaboration has also resulted in advocacy for initiatives that were aimed at improving both patient and staff safety in the past few years.

Through her tenure in leadership, Bezek focused on serving the needs of patients on a population-health level. As her responsibilities grew, so did GCH, from one floor on SMH to the major world-class facility that it is now. During this time,

24 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Bezek also witnessed the landscape of pediatric health care change.

“The patient population that we care for is much more acute and complex than when I first started. The families have information at their fingertips through the internet. They have multiple, wellresearched, and detailed questions that can make things tougher for clinicians to be at the ready for them and answer in a timely fashion. This requires more collaboration across specialties and more shared knowledge in order for us to serve families best,” she said.

Sue Bezek’s ability to solve problems creatively, build highly effective teams, and remain laser-focused on provision of high quality, family-centered care have made her an effective leader that has contributed greatly to the growth of GCH, according to Tim Stevens, MD, Chief Clinical Officer at GCH.

“Nurses are the first point of care for many of our patients, so fostering a strong patient-first nursing culture is critical for building trust with our community,” he said. “Sue brings a thoughtful, inclusive, and family-focused approach to leadership that has shown great results toward helping children in the region and beyond.”

In addition to her experience as a clinician and leader, Bezek has coauthored a few book chapters, has guest lectured at the University of Rochester School of Nursing, and has won several awards, including the 2010 Ruth Lawrence Academic Faculty Service Award in Community Service, and the 2012 Excellence in Nursing Leadership Award and the 2016 March of Dimes Nurse of the Year in Leadership.

Miracle Maker Award for Outstanding Commitment by Grateful Parents Diana and Nick Rawden

When Diana Rawden was pregnant with Nash, it was discovered that he had a very serious heart defect that would require surgery after he was born. Nash underwent his first surgery at just five days old. Thanks to George Alfieris, MD, chief of pediatric surgery at GCH, and his entire team, Nash’s heart defect was fixed during this first surgery! During routine checkups after his surgery, however, it was then discovered that there was another issue, and at just six months old, Nash underwent a second open-heart surgery. Again, thanks to Alfieris and his team, Nash had a successful surgery and is now a very healthy and energetic six-year-old! Diana and Nick were so grateful for the care Nash received at GCH that they decided they wanted to help give back to the hospital. They started a golf tournament in 2022 and have raised more than $71,000 for our PICU department. This year will be the 3rd Annual #OurNash Golf Tournament, and we can’t begin to thank the Rawdens enough for their true dedication and continued support!

25 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

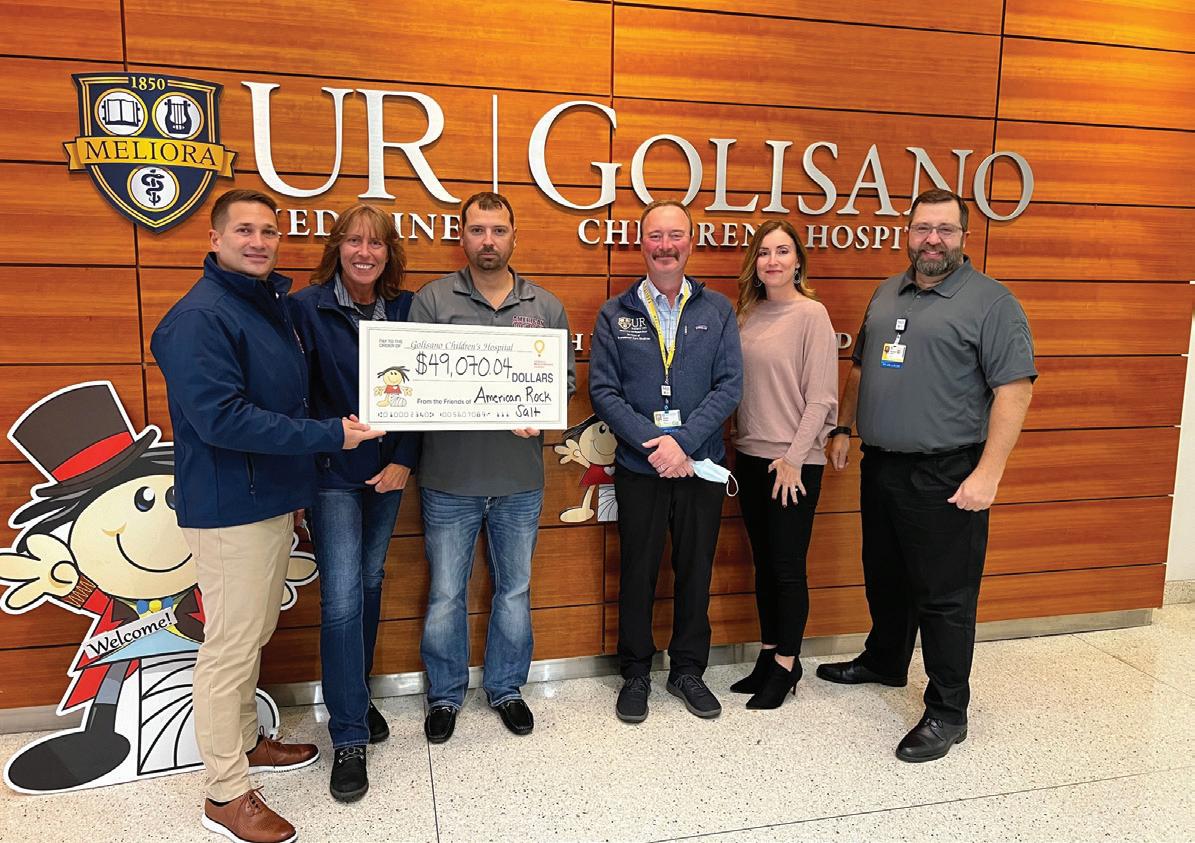

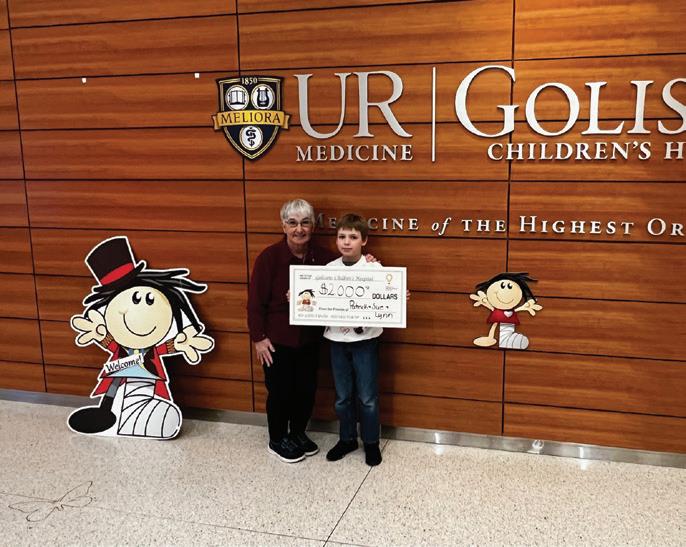

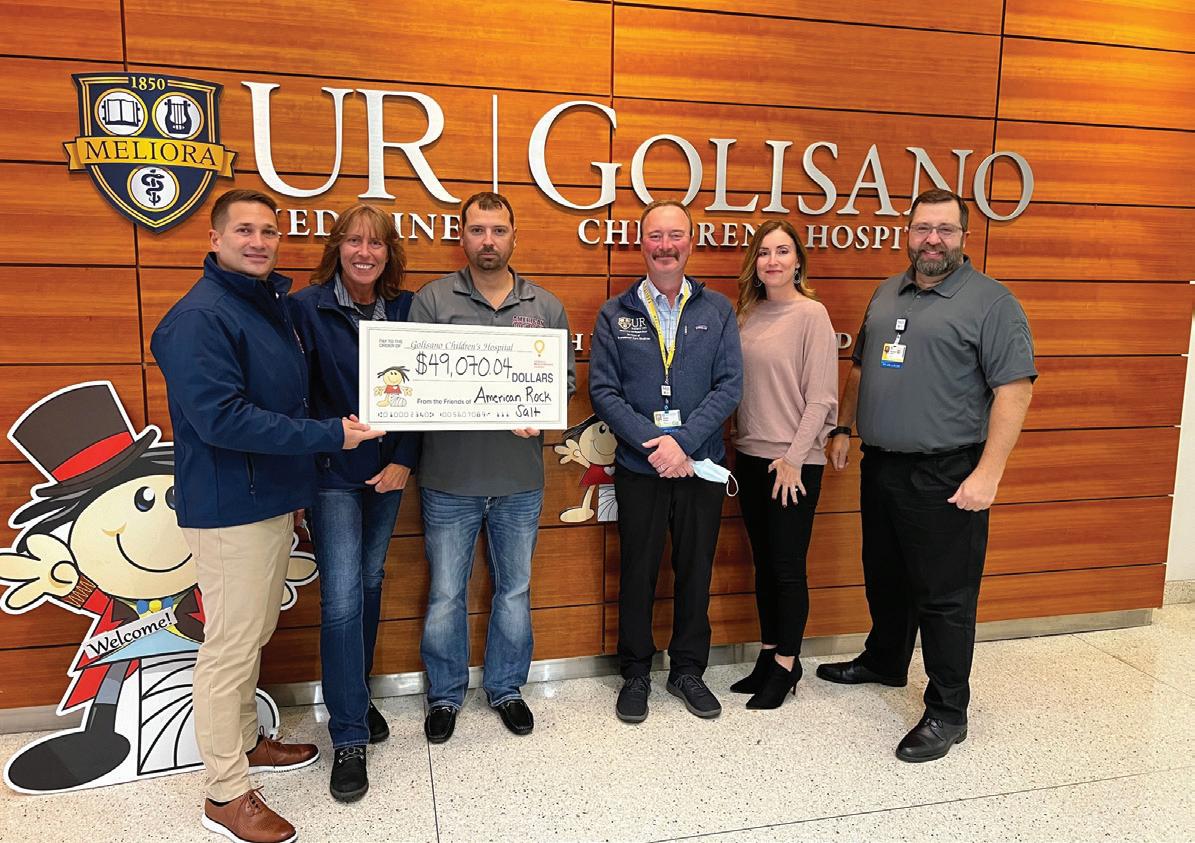

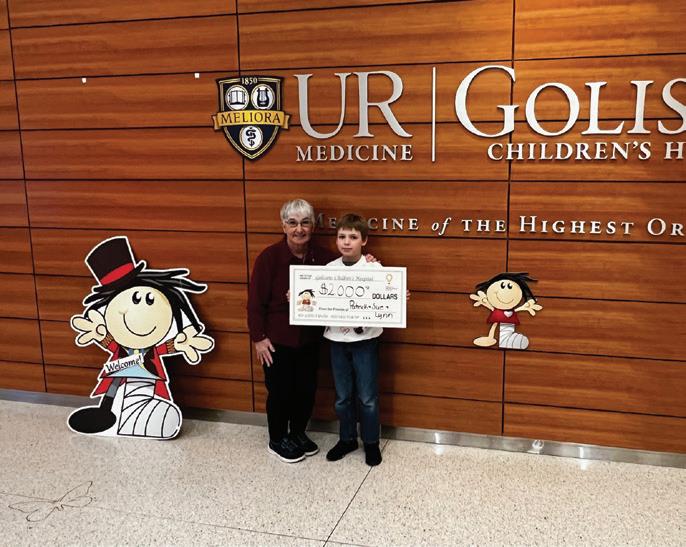

Miracle Maker Award for Outstanding Commitment by a Community Group American Rock Salt

In 2021 the team at American Rock Salt decided to hold their first-ever charity golf tournament. At the time, they learned that a member of the team had a granddaughter who had spent a few months in GCH. They ultimately made the decision to give back and donate the proceeds from their tournament to the hospital that took such good care of one of their own. It was a huge success, and they decided to make this an annual event. Since the tournament’s inception in 2021, more than $134,000 has been raised for Golisano Children’s Hospital! We are grateful for the team’s continued support and look forward to working with them again on this year’s golf tournament.

Miracle Maker Award for Outstanding Commitment by a Company Howard Hanna Real Estate Services

Howard Hanna has been a continual supporter of GCH for close to 10 years. The company is dedicated to making a difference in our community, and its goal is to raise money that will help provide families access to pediatric care, essential services, and life-saving medical treatments they ordinarily cannot afford because of their financial circumstances.

Howard Hanna has held various events over the last few years that have raised crucial funds for its Children’s Free Care Fund here at GCH. Some of these events have included a Game Day Event, VIP Buffalo Bills Training Camp Event, and a golf tournament. Outside of hosting its own events to raise funds for the hospital, the firm also helps support our various fundraising events, including Stroll for Strong Kids and GCH Gala. Between its own events and the support of ours, Howard Hanna has provided more than $169,000 in support to GCH! We are so grateful for the partnership we have with Howard Hanna and we look forward to working with the team for years to come.

26 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

27 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

Board Spotlight: Lauren Dixon

Throughout her life, Lauren Dixon has worn many hats. As the founder of the Dixon Schwabl + Company, a marketing and advertising agency, she built the firm from a tiny, upstart company in 1987 to the 100-plus-employee organization it is today. During her career, she’s also served on 11 boards, including a previous stint at URMC’s Thompson Health. She accomplished all of this while raising four children with her husband (and coleader of Dixon Schwabl), Mike Schwabl.

Lauren’s own experience of being a parent, as well as observing her Dixon Schwabl employees raise their kids, opened her eyes to the importance of supporting GCH. While her own children grew up healthy, several of her employees had children who experienced NICU stays, needed complicated surgeries, and/or underwent treatments for cancer.

“I watched my work family go through difficult, challenging days. I was eager to help make a difference, and because Golisano had helped my team members immensely, I wanted to give back,” she said.

Lauren has also seen GCH grow during the past decades, emerging from being a mostly local institution to now serving children beyond New York State. As a new board member—and someone who sponsored a room during the construction of the current facility—she wants to facilitate GCH’s expansion as a benefit both to the Rochester community and beyond.

“When we sponsored a room several years ago, there was an understanding that every child would get their own room. GCH has grown so much that it’s no longer the case,” said Lauren. “It’s important to me to continue that growth opportunity, leverage the expertise we have, and build on our new abilities to hire the best and brightest in the country.”

Board Spotlight: Kathy York

Kathy York joined the Golisano Children’s Hospital board in 2022. Before retiring, she had spent nearly 30 years working with children as a teacher, nanny, daycare director, foster parent, and mom. The last 10 years of her career were spent working with toddlers and college students at Syracuse University.

“Joining the Children’s Hospital board is a perfect fit for me, as I want to give back to the community by making a difference for future generations of children and families. My entire life has revolved around children, and helping ensure access to excellent medical care by serving on the board is a privilege!” she said.

The central New York native also serves on the board of the Brighter Days Foundation. This foundation is one of the sponsors of the Brighter Days Pediatric Mental Health Urgent Care Center, which is set to open in early summer 2024 on Crittenden Blvd. near Golisano Children’s Hospital. This will be only the second urgent-care center of its kind in all of New York State.

“When parents have a child or adolescent in crisis, they need to have access to care immediately,” said York, “not wait for days, weeks, or months in the future. We are so excited to see a program that will be available to families seven days a week in the afternoon and evenings right here in central New York!”

In her free time, Kathy enjoys spending time with her husband, Frank, their four adult children and children’s spouses. She currently has one grandchild and another one due this summer. Kathy also enjoys travel, gardening, and hiking with family and friends.

28 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

Thank you!

We are extremely grateful to our community fundraisers.

Bapa Network Foundation

Battle of the Beaks—Basketball Game

Brighton Police Patrolman’s Association

Fairport Central School District Fall Crawl

Howard Hanna—Children’s Free Care Fund

John Betlem Heating and Cooling

Kyle O’Donnell and Family

Lauren Elker—3rd Annual Paddle Tournament

Mandy Meyers

Rainbow Classic Fundraiser

Roberts Wesleyan University Fundraiser—

Bob Segave and Team

Spirit of Children

Sue and Patrick Hartrick

Tai Chi Bubble Tea

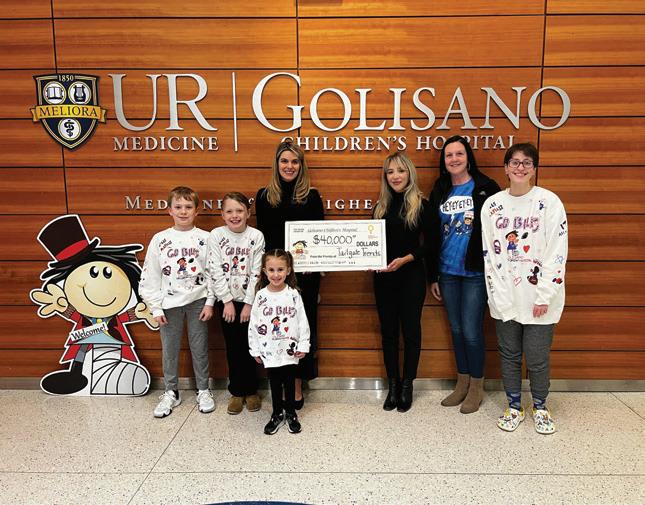

Tailgate Trends

30 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024 – V1

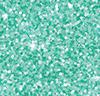

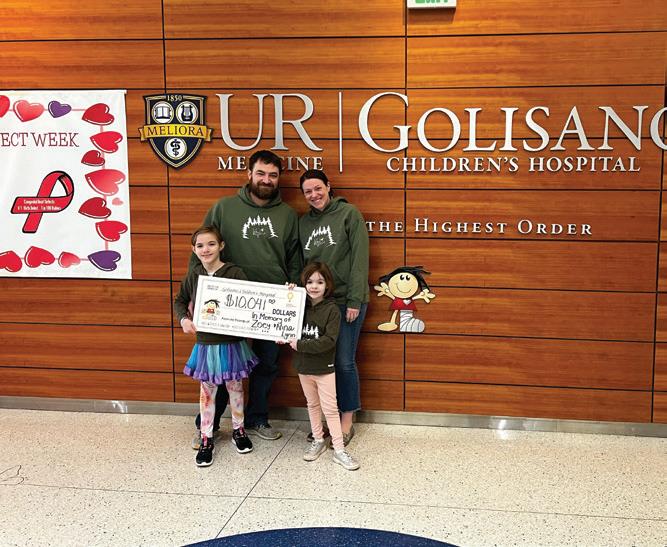

Zoey’s Tree Farm Fundraiser—Lytle Family

John Betlem Heating and Cooling

LaurenElker—3rdAnnualPaddle Tournament

SpiritofChildren

Zoey’sTreeFarmFundraiser— LytleFamily

Sue and Patrick Hartrick

Tai Chi

Bubble Tea

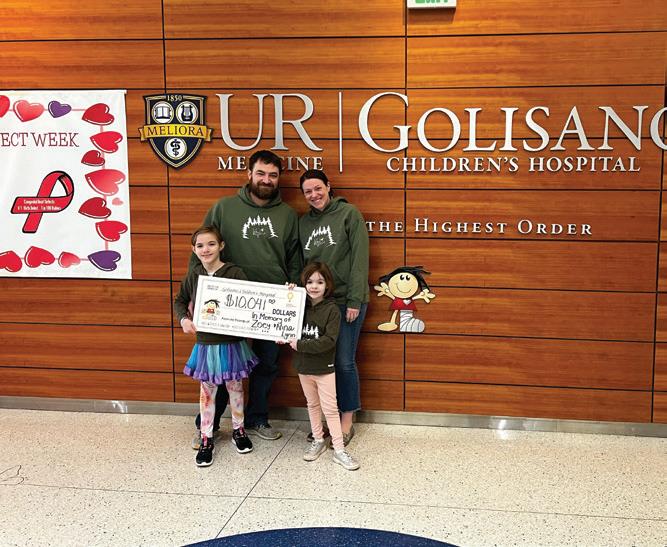

TailgateTrends

Upcoming Community Events

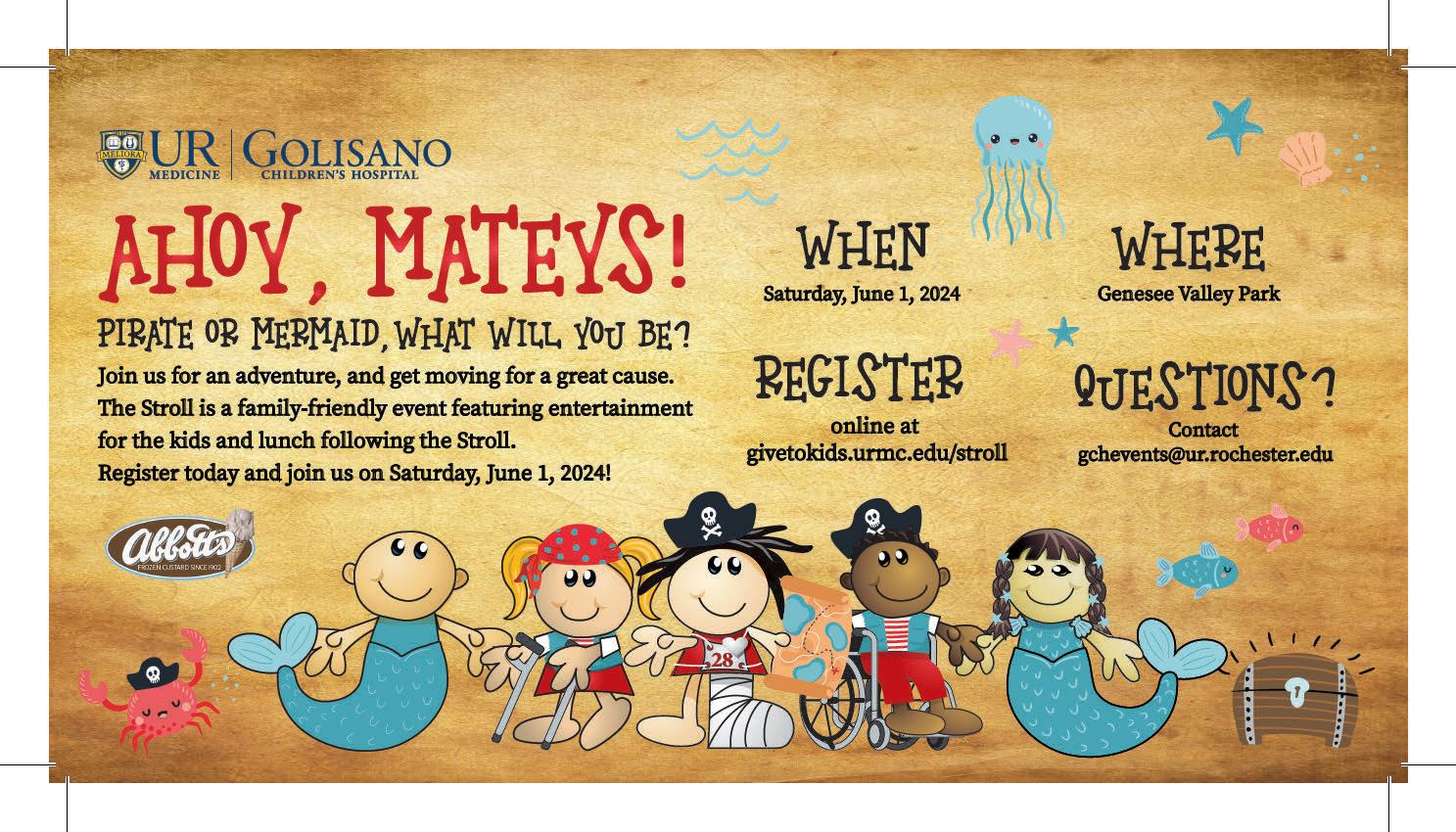

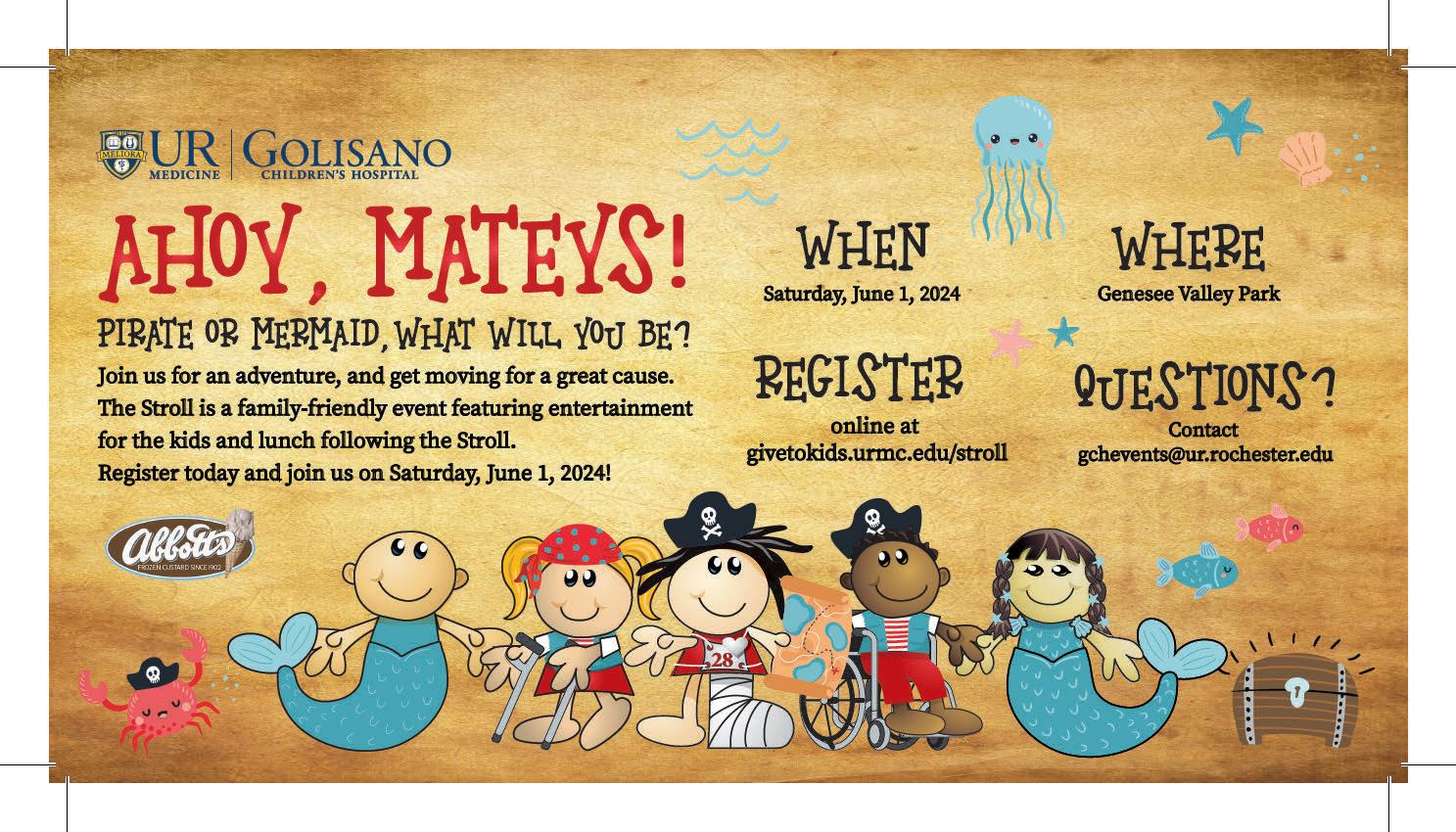

Stroll for Strong Kids

Saturday, June 1

Genesee Valley Park 5k – 8:30 am

Golisano Children’s Hospital Advancement Office 585.273.5948 | www.givetokids.urmc.edu

Scott Rasmussen Sr. Assistant Vice President for Advancement

Betsy Findlay Sr. Director of Advancement, Special Events and Children’s Miracle Network

Stroll for Strong Kids – 10:30 am Givetokids.urmc.edu/stroll

GCH Golf Tournament

Monday, September 9

Oak Hill and Monroe Golf Clubs

Lunch and registration 11 – noon; shotgun start at 12:15

Sponsorships available. Contact bfindlay@admin.rochester.edu

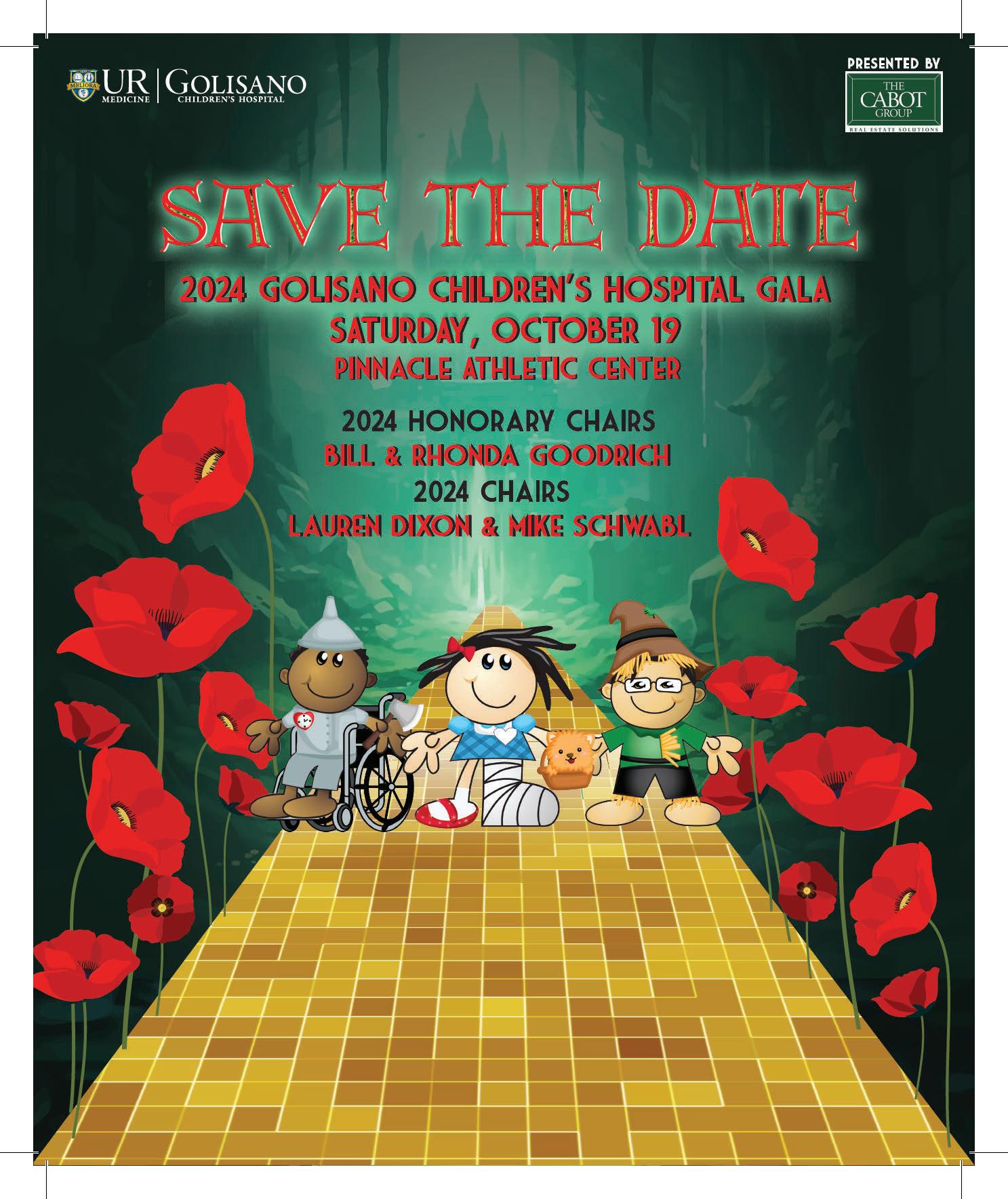

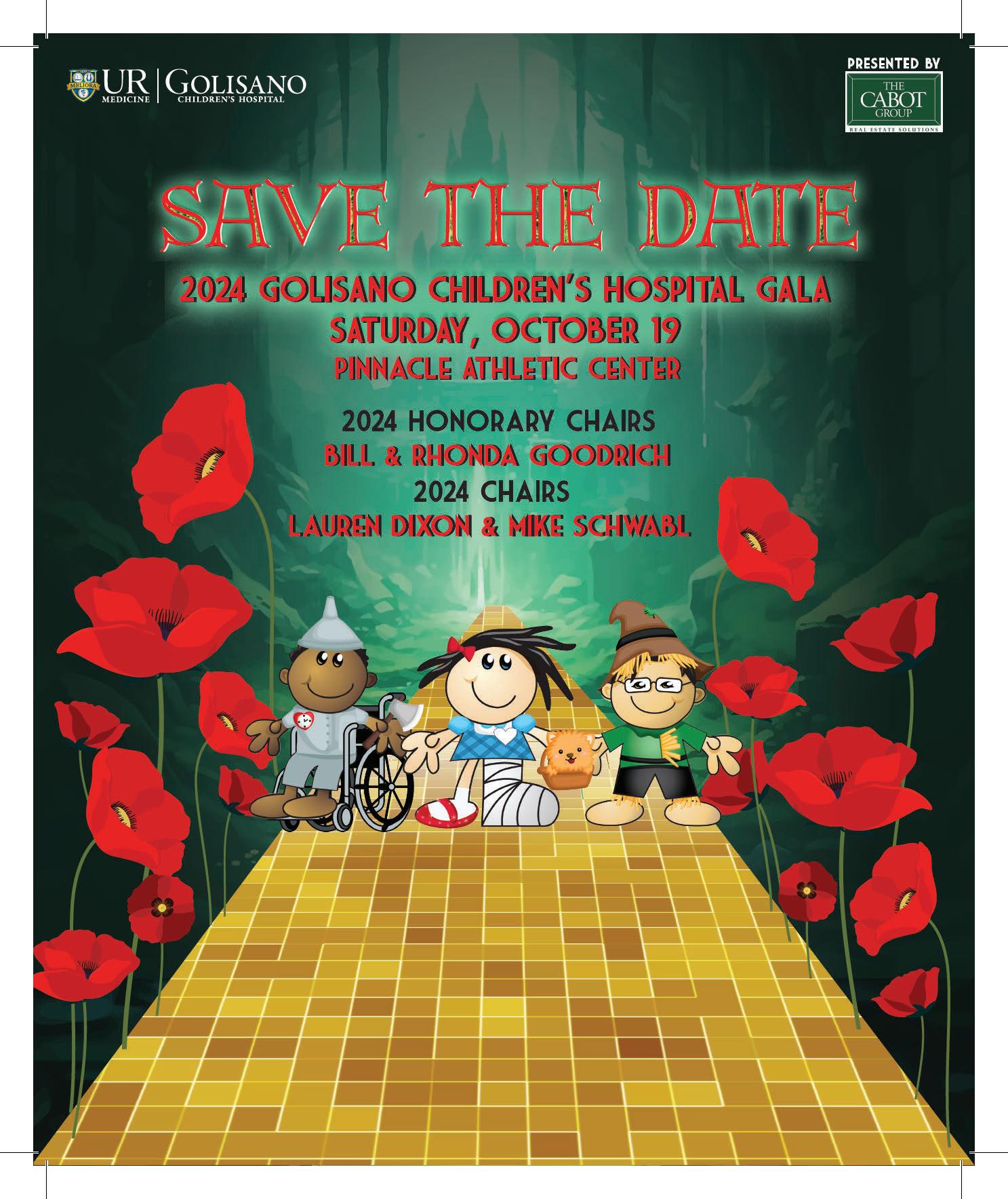

GCH Gala

Saturday, October 19

Dave Brown Associate Director of Advancement

John Belt Advancement Assistant

Sarah Craig Associate Director, Community Affairs

Katie Keating Development Associate

Pinnacle Athletic Center, Victor 6-11 pm

Sponsorships available. contact bfindlay@admin.rochester.edu Givetokids.urmc.edu/gala

Costco In-Store Fundraising

May 1-31

Walmart In-store fundraising

June 10 – July 7

Tops Friendly Markets In-store Fundraising

June 16 – July 6

Dairy Queen In-store fundraising

June 1 – July 25

Miracle Treat Day – July 25

Speedway/7-ElevenYear-round fundraising at all Rochester area locations

Jennifer Paolucci Assistant Director, Special Events and Children’s Miracle Network

Public Relations and Communications 585.273.2840

Scott Hesel Communications Manager Kiara Warren Public Relations Associate

Karen Ver Steeg Art Direction & Design

Help give back just by using your debit card! Each year, Advantage will donate a portion of their profits to Golisano Children’s Hospital when you use the GCH debit card. Advantage has donated over $32,000 to Golisano Children’s Hospital since 2013! Visit any Advantage Federal Credit Union to sign up for your debit card.

Find us on social media:

facebook.com/GolisanoChildrensHospital

twitter.com/urmed_gch instagram.com/urmed_gch

31 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2024– V1

32 Golisano Children’s Hospital | 2023 – V1 University of Rochester Office of Advancement and Community Affairs 300 East River Road PO Box 278996 Rochester,

To make a donation online go to givetokids.urmc.edu

NY 14627-8996

Jill Halterman, MD, MPH

Jill Halterman, MD, MPH