What is the relationship between law and the built form?

How have planners exerted pressure on regulators?

How does the city reflect the constraints and incentives provided by planning law?

These questions, borne of an inquiry initially sparked by Alex Lehnerer’s work Grand Urban Rules, are the pathways through which an interdisciplinary team from Law and SAPL explored how rules shape the urban form and the city. In this edition of NXC, the authors, Kirandeep Kaur (SAPL) and Benjamin Sasges (Law), argue that the relationship between law and form is not a unilateral imposition of power, but one characterized by bilateralism, with both sides pushing and pulling against the other.

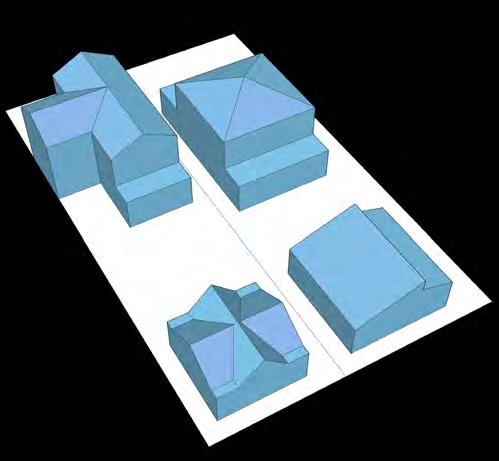

To illustrate this relationship, the authors examined four examples as intersections of law and form. These were a right to sunlight, incentives for development in the downtown core, backyard suites, and redevelopment.

Richard Parker Initiative

TOWERS & INCENTIVES

BACKYARD SUITES

INFILL REDEVELOPMENT 39| CONTRIBUTORS

As an interdisciplinary project between the Faculty of Law and the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, the disciplinary differences provided ample opportunity for discourse, both between the study participants and thirdparties brought in to provide constructive feedback on the work. In that same vein, the authors would like to thank Justice Ola Malik of the Court of Queen’s Bench, as well as David Down, of the City of Calgary.

There are two important characteristics of Calgary to consider in context to this study. First, the urban fabric of the city is predominantly low rise, with the exception of Downtown with its high rise buildings. Second, the angle of the sun in Calgary means that even relatively short buildings can cast considerable shadow.

It is in this backdrop that we examine a tapestry of regulatory interventions. Some, such as those protecting sunlight, tend to inhibit high rise development. Others allow greater height and development in a bonusing system, which sees developers providing public amenities in exchange for a larger footprint.

If sunlight has entered a certain window for 20 years or more, then the owner has a right to expect that this shall be the case in the future as well. [p.151, 254]

Through the heights of the adjacent buildings, the upper space around the cathedral shall remain unencumbered by visual interference. Tall structures will be permitted to stand in the cathedral’s view shadow. [p.136, 249, 251, 256, fig.49-52]

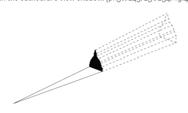

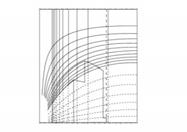

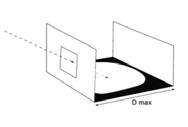

The Daylight Evaluation Chart measures and regulates the shadows cast on the street by the building. [p.155, 251, 252, fig.62]

By virtue of their locations, topographies, or buildings, certain streets possess visual qualities. These stand under special protection. A quality of street view map specifies the view relationships and visual peculiarities that are to be protected.[p.128, 252, 254, fig.43]

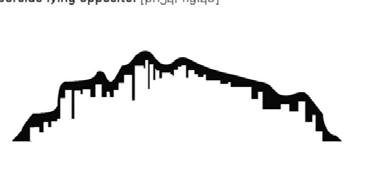

In order to allow the city to remain visibly a settlement at the edge of mountainous terrain, the ridgeline of the mountain range is protected. The city has the discretion to determine the number of meters of ridgeline that must be visible from the harbor-side lying opposite.

[p.134, fig.48]

Access to sunlight is considered by many to be a crucial amenity of any public space. In a private context, a backyard dominated by a neighbor’s tree or a newly built high-rise, can give rise to significant complaints regarding the lack of access to sunshine. Our study, mirroring the ways sunlight protection is considered differently in public and private contexts, divided the notion of sunlight preservation into two inquiries. In a public context, the law protecting sunlight is extremely limited. A general right to sunlight has its roots as a common law property right in England. This right allowed a property owner who had received a particular amount of sunlight for a period of 20 years or more to block development that would block such sunlight. While this right still exists in some jurisdictions, in Alberta this right is explicitly excluded.

Therefore, statutory rights to light exist in pockets, applied to specific areas and types of developments.

applied to specific areas and types of developments. One such area which is protected - under the Municipal Land Use Bylawis Century Gardens, an area between 7th and 8th avenues, and 7th and 8th streets in the Southwest of downtown Calgary. Surrounded by high rise buildings on all sides, Century Gardens follows the City’s goal of having public space within 5 minutes walking distance from anywhere in downtown. This 7000 sq m urban park provides much needed relief from the surrounding density and intensity. It provides a place where people can take a break from their commute, or where users from nearby buildings can come for their lunch or coffee breaks. This public space also forms an informal link between the Beltline district and the downtown core.

DOWNTOWN WEST END

The following sunlight protection areas must not be placed in greater shadow by a development as measured on September 21, at the times and locations indicated for each area, than were already existing on the date the development permit was applied for: (d) Century Gardens as measured on those portions contained within Plan 8050EJ, Block 46, Lots B to E; Plan A1, Block 46, Lots 27-40 and PlanA1, Block 46, OT from 12:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m. Mountain Daylight Time.

As noted, the Municipal Land Use Bylaw protects Century Gardens by prohibiting development that would cast shadow on the protected area between certain times.

This decision is prescriptive, and clearly identifies certain areas as being of public importance. In the previous version of the Land Use Bylaw, the section that listed these protected spaces categorized them as “Sunlight on Important Public Space”. A statutory document therefore identified certain areas as

having public importance, from which it can be inferred that sunlight is something that some important spaces have some sort of right to.

The fact that some spaces receive protection and others don’t raises the question of how certain spaces are selected. As our research has covered elsewhere, if access to sunlight is in fact a right, even a limited one, it should be clear what criteria need to be met in order to access that “right”. Alternatively, one might expect that public consultation drives the selection of locations to benefit from this right. From our research, it is not clear that either of those measures have been adopted, indeed, for over two decades the sites protected under the Land Use Bylaw have not changed. As we examine Century

Gardens, consider how the measures which shape the landscape around that area would impact other parts of Calgary. What commercial, political, and social projects or interests would these measures be in conflict with?

It shows the area of Century Gardens being built up and occupied by buildings prior to 1975. To celebrate Calgary’s centennial, the land of Century Gardens was developed into an urban park. In the 2020 image, we can see the park under redevelopment, the proposal for which was based on extensive public participation.

With two new park pavilion buildings, a public washroom, and future park food concessions, the park will be safer, with upgraded lighting and security cameras. Upgraded heritage waterfalls, and a new central splash pad will be the public attractions, with improved access from surrounding areas. With Century Gardens inclusion in the Land Use Bylaw, the City ensures that these amenities will have as much sunlight access as possible, despite their central location in the downtown core.

We see the spatial repercussions of sunlight protection, as the shadows cast by surrounding buildings never put Century Gardens in full shadow. The only building casting serious shadow on Century Gardens is the Westview Heights Apartment building, constructed in 1972, pre-dating the regulation.

Recalling the question posed earlier, the magnitude of the spatial impact suggests potential conflict that sunlight protection would have with other interests. More widespread

sunlight protection would constrain development, potentially to an untenable degree for many builders and investors. When taking into consideration optimal building height, at least some scholarship frames regulations such as sunlight protection as an obstacle or hindrance to best design. Beyond commercial interests, increased densification is seen as a crucial tool in providing affordable housing in an increasingly urbanizing world. In that view, measures such as sunlight protection hinder the ability for housing stock to most efficiently respond to increased demand and may cause home prices to stay artificially high.

On the other hand, what might Century Gardens have looked like in the absence of protections for sunlight? How tall might surrounding buildings have been and what impact might they have had on the quality of public space?

The Westview Heights Apartments building, built in the year 1972, is the talllest building to the south of Century Gardens and pre-dates the regulation for sunlight preservation.

Here, another shadow visualization demonstrates how any additional built volume would cast a much greater shadow than what exists. Such development would negatively affect the public value of the park, and undermine the use of the park.

A second, private context of sunlight protection enshrined in law is found in statutory plans for different communities. Such documents are created under statute, and are empowered by the Municipal Government Act (the “Act”). These documents, for example an Area Redevelopment Plan (“ARP”) or Area Structure Plan (“ASP”), do not “require the municipality to undertake any of the projects referred to in it” (under s. 637 of the Act), however development permits are still subject to the relevant statutory plan. Therefore, when hearing any appeal regarding a development permit issuance, the board hearing it must comply with any applicable statutory plans.

The references to sunlight in different statutory plans across the city range from those with strict, prescriptive requirements, to those with absolutely no mention of sunlight. In the following map, a sample of statutory plans have been selected

Municipal Government Act:Governing Statute

MGA creates Statutory Plans, including:

and categorized into three categories, either through the language or the broadness of applicability.

A plan with stronger right to sunlight, such as the Hounsfield Heights/ Briar Hill ARP, contains proscriptive language such as “redevelopment shall consider”, and “the following guidelines and actions are required”. On the other hand, weaker protections are articulated in the more equivocal and permissive language found in the Calgary/Altadore ARP where sunlight protection “is to be encouraged”. As the map demonstrates, in most of the neighbourhoods considered in the study there is no right to sunlight in their relevant statutory plan. This is particularly acute as the neighbourhoods become less central, with very few neighbourhoods outside the city’s core having any mention of sunlight protection.

Area Structure Plans and Area Redevelopment Plans (ss. 633, 634)

When a development is appealed, ceteris paribus, the body hearing the appeal must comply with any applicable statutory plans [s. 687(3)(a.2)]

How do these laws affect the built form? Consider one hearing held under the Hounsfield Heights/Briar Hill ARP, a statutory plan with one of the most stringent levels of sunlight protection in the city. In this case, the tribunal heard that a proposed addition to a home would create significant loss of ambient light to the neighboring lot. The complainant asserted that it would “greatly affect their family’s quality of life, in particular of their handicapped son who resided with his brother at the home.” The Board accepted the evidence that the son would be significantly impacted negatively. Despite the lack of an absolute right to the protection of sunlight, the form of the home, as well as the situation of the family, when considered in light of the ARP, caused the proposed redevelopment to be rejected and the right to sunlight affirmed.

In this case, the relationship between form and law is hardly unilateral. While boards and tribunals hearing such appeals, may take into consideration the statutory plan, there is overwhelming evidence that often it does not factor into the final decision. Even in neighborhoods with more stringent protections in their statutory plans, boards and tribunals regularly find that a

detrimental effect to sunlight is insufficient to revoke or cancel a development permitfollowing map, a sample of statutory plans have been selected and categorized into three categories, either through the language or the broadness of applicability.

References: SDAB2012-0028 (Re) [April 18,2012]

As the City grows, and requires greater density, the City must balance that interest against protecting heritage sites, accessible public space, and pedestrian pathways. One of the tools the City has to do this is through Density Bonusing Policies (“DBP”s). Density bonusing is “a planning practice in which development must provide public amenities to accompany the additional density it is proposing.”

In Calgary, these zones are found in the downtown Beltline area. The DBPs are governed under the Land Use Bylaw 1P2007, s. 1332. Under this section, the Bylaw states that “the floor area ratio of the Commercial Residential District (CR20-C20/R20) may be increased in accordance with the incentive provisions of this Division to a maximum total of 20.0 floor area ratio.” (1332(1))

The Bylaw emphasizes that the public amenities must be as permanent as the development they are

connected to (s. 5), and explicitly defines the types of amenities that qualify under the scheme (s. 4). As an incentive system, the way that the amenities are defined tends not to be restrictive. For example, Public Open Space, a qualifying amenity, must only be “landscaped, publicly accessible, pedestrian space that is open to the sky and is located at grade. It may be soft or hard landscaped.” (1P2007, s. 8.2, p 810.)

This legal framework allows for flexibility in form, while effectively incentivizing behavior based on policy priorities. The law therefore enshrines values, and allows individuals to make choices about the built environment within the parameters of those values.

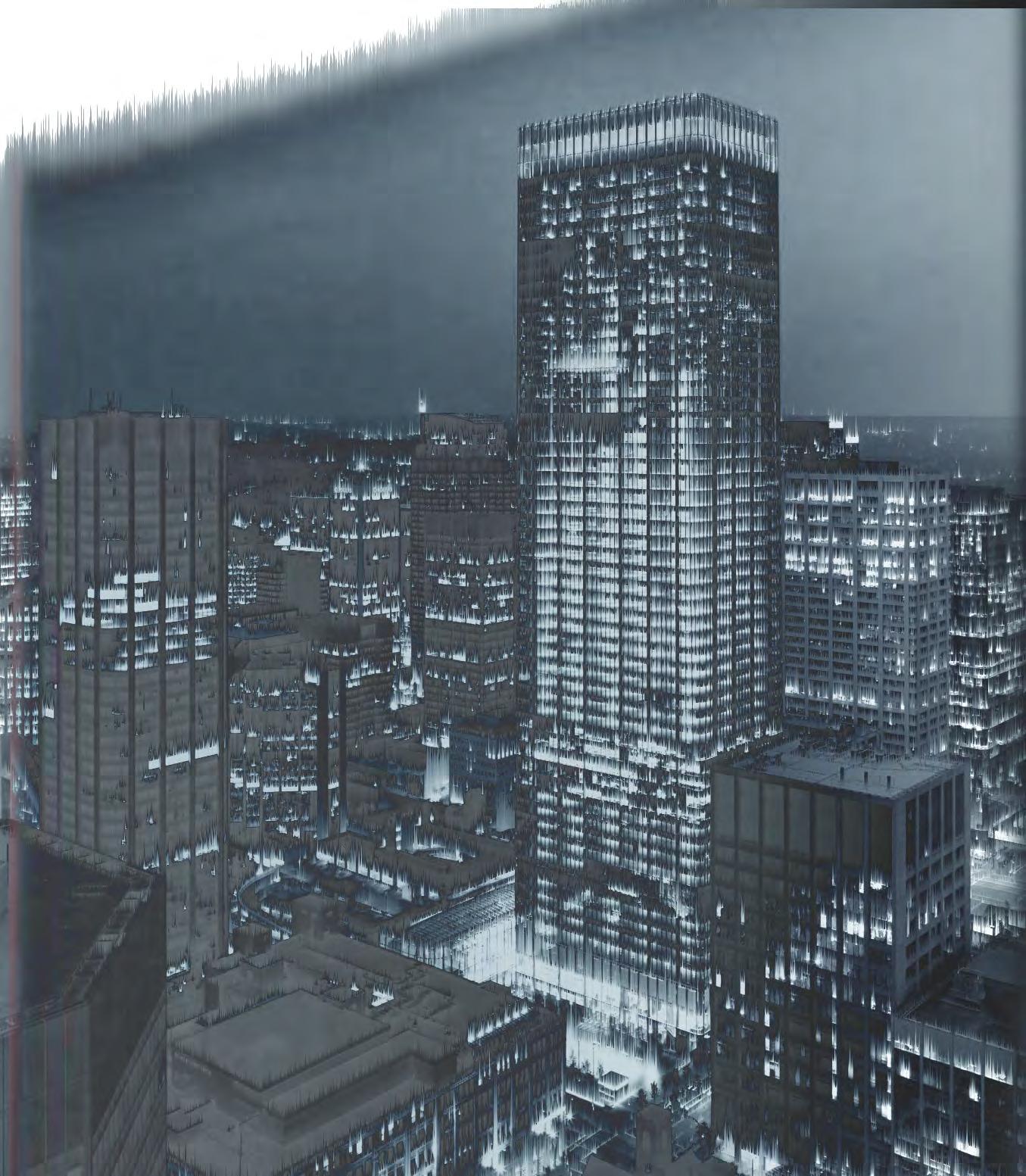

Brookfield place is one such example, where bonus density incentivizes public amenities, based on policy. At 247 meters, it is the tallest building in Calgary, featuring a three-storey, 50,000 square foot transparent glass pavilion connected to the City’s Plus 15 system, an indoor urban groove, and numerous sustainable design features. Public amenities include Public Art & active art space and an outdoor plaza, significantly contributing to the public realm with programmable public space, restaurants, cafe’s and cultural activities. On the facing page, the graphic shows the break up of bonus density incentives used to achieve the iconic form of Brookfield Place. As referenced at Table 8, many of the features that make Brookfield Place such a landmark building are the result of amenity bonuses. While ostensibly these features are “concessions” made to the city in exchange for increased density, the features have the effect of greatly enhancing Brookfield Place’s profile and making it a more desirable location.

TABLE 8: PUBLIC AMENITY ITEMS

3.0 FAR

4.0 FAR 1.0 FAR

4.0 FAR

4.5 FAR 1.0 FAR

1.5 FAR 1.0 FAR 1.0 FAR

LAND USE BYLAW – 1P2007

Base

8.0 On-site Pedestrian Amenities

8.1 Contribution for CBD Improvement Fund

8.2 Public Open Space

8.3 Indoor Park Incentive

8.4 Urban Grove

8.5 Public Art on Site &

8.6 Contribution to Public ART Fund

8.10 Active Art Space

8.23 +15 Skywalk Bridge

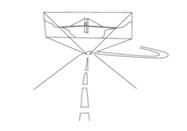

A unique aspect of Calgary’s downtown core is the +15 Skywalk System. This system connects a number of towers downtown by way of elevated “tunnels” which run above streetscapes and allow for easy movement through the core under any weather condition. Under s. 1332 (8.23), constructing a +15 Skywalk System bridge provides 1.0 floor area ratio (to a maximum of 2.0) to a proposed development. As a hallmark characteristic of the commercial core, developers are incentivised to include a bridge both through the Land Use Bylaw and to provide better integration into the downtown for its tenants

MULTI-RESIDENTIAL HIGH RISE SUPPORT COMMERCIAL DISTRICT (CC-MHX)

1139. Restricts floor plate above but gives more density below to have better street frontage & flexibility of floor plate size for mix of uses above.

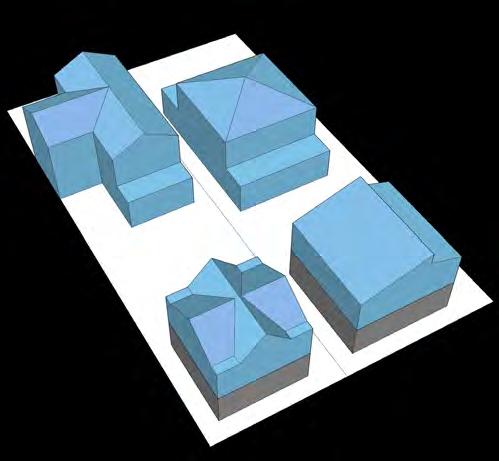

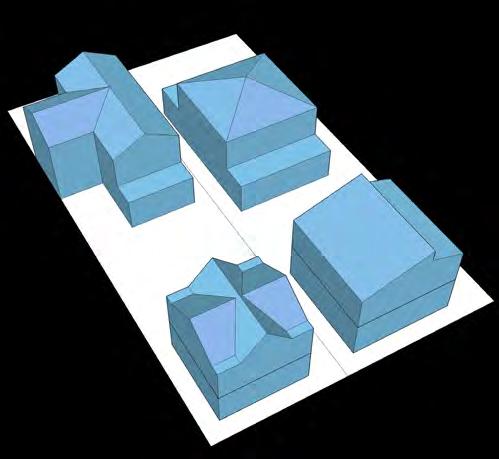

An additional prescriptive mechanism for shaping the city exists in section 1139, 1221, and 1314 of the Land Use Bylaw. These sections restrict the overall floor plate area of developments, which can only be overcome through mechanisms such as the Bonus Density system - which themselves exert significant impact on form. For instance, s. 1139 states that each floor located above 25.0 meters above grade must have a maximum floor plate area of 650.0 square metres, and a horizontal dimension of 37.0 meters. The restrictions are relaxed in some areas, such as through s. 1221 for the East Village Transition District, but still provide hard constraints that affect the size of new developments.

This restrictive floor plate policy acts as a mechanism to influence the land use of these towers, as well as the form. One such example is the Vantage Pointe Building, in Connaught district of the Beltline area, where

1221. More Density to Centre City East Village Transition District.

(1) CENTRE CITY EAST VILLAGE TRANSITION DISTRICT

Restricts frontage to 60 m ( 36 m above grade) in the 6 m buffer from street, restricts floor plate size to 930 sqm.

(2) OTHERS

Restricts frontage to 60 m (25 m above grade) in the 6 m buffer from street, restricts floor plate size to 750sqm.

the restrictive floor plates allow for a 3 floor pedestrian scale podium below, and a residential tower above and four floors of underground parking. Vantage point is a of underground parking. Vantage point is a full block development, with co-op food market on the western portion and a 26 story tower on the eastern portion of the site.

With the current economic trends affecting vacancy rates in the core of the city, we now face a challenge of adaptive reuse of vacant office towers. The Cube, across the street from Vantage Pointe, is one such project, where an office tower has been repurposed to residential use, bringing new meaning to the neighbourhood. This was facilitated by the City under Calgary’s Centre City Enterprise Area plan for 3 years, wherein changes of use, exterior alterations or small additions did not need a development permit in the Beltline or Downtown areas.

1314. More Density in Transition Area to Comercial Residential District.

Vantage Pointe. Source - https://www.dononda.com/

The Cube. Source - https://renx.ca/

Secondary and backyard suites are developments that are added to residential dwellings (typically single family detached units), that increase density and provide diverse housing options within a community. In recent years, backyard suites in particular have been the subject of considerable attention from proponents and opponents alike. As Cailynn Klingbeil put in a 2019 article for The Sprawl, “For Calgary, a city trying to shift half of new growth into existing neighbourhoods by 2069, backyard suites are an important tool. The density they bring is gentle, as unlike other forms of infill, existing houses remain in place.”

Though the City has taken strides in incentivizing the creation of backyard suites through law, heavy regulation still weighs in on their creation. The Land Use Bylaw 1P2007 explicitly states that “a Secondary Suite and a Backyard Suite must not be located on the same parcel.” (s. 354(2)). Therefore, while

(s. 354(2)). Therefore, while density is being incentivized to a certain extent, other constraints are introduced into the regulation of backyard suites.

In addition, backyard suites - and secondary suites for that matter, face hurdles in the form of restrictive covenants which prohibit certain types of developments. Restrictive covenants are a common law instrument whereby the owner of a plot of land covenants with the owner of an adjacent/neighboring parcel not to make certain undertakings on that land. This covenant runs with the land, or in other words is passed down through title. Therefore, if an individual buys land that is encumbered by a restrictive covenant, they must abide by the demands of the restrictive covenant. Entire communities can have restrictive covenants, which is often the case in Calgary.

University Suites - Backyard Suites

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY

BANFF TRAIL

UNIVERSITY HEIGHTS

Therefore, despite broad policy moves towards greater density, backyard suites still face significant hurdles.

Consider the case of Faulkner v Donaldson (2020 ABQB 259), in which a home with a secondary suite was found to be in contravention of a local restrictive covenant and the owners of the secondary suite were ordered to comply with the covenant. That case affirms that restrictive covenants are enforceable, and can significantly hinder any densification in a given neighborhood. The neighborhood in question in Faulkner, University Heights, continues to reflect this restriction. As of 2021, only four secondary suites exist in the community.

Though restrictive covenants explicitly enshrine conceptualizations of a neighborhood’s character and prohibit increased density, such attitudes are also present in the written law. When interpreting clauses pertaining to backyard suites, one Board noted that “a backyard suite is secondary to the main residential use of the parcel… and the board finds that Backyard Suites are intended to be accessory in relation to the main residential dwelling on a parcel.” (SDAB2016-0017, para 14) In that same case, the Board found that the large, proposed backyard suite would result in

more potential occupants and “additional parking demand which would impact the adjacent properties and the surrounding area.” (Para 20)

Further, as the case was being heard under s. 35, a Discretionary Use Development Permit Application, the Board was free to consider the compatibility and impact of the proposed development with respect to adjacent development and the neighborhood (s. 35(d) 1P2007).

Weighing on this issue, the Board found that the proposed, large backyard suite would “unduly interfere with the amenities of the neighborhood, or would materially interfere with or affect the use or enjoyment of neighboring parcels of land.” (Para 25)

What both Faulkner and this Board decision demonstrate is the degree to which the law has enshrined interests opposed to density, even while legislation supposedly serves to increase it. While the law has opened the doors in some respects to backyard suites, in actual operation significant challenges remain.

The city of Calgary defines Backyard suites as ” a dwelling unit in a building that is detached from the main residence, such as a garage suite, garden suite or laneway home”. For the purpose of this study, we have considered Backyard suites in the two locations as marked on the map below.

BUILDING PLACEMENT

SUNLIGHT AND SHADOWING

TREES

HEIGHT AND MASSING

BALCONIES WINDOWS

ACCESS

The backyard suite is placed in alignment to the neighbours’ yard, and buildings, while ensuring easy access to the lane.

Location of the Backyard suite ensures maximum sunlight, both for owner’s and neighbour’s yards.

Existing healthy trees in between both the backyard suites has been mained, and acts as a privacy screen.

The height, massing and roof profiles of the suites, transition from the neighbourhood parcels, reducing the percieved heiht of the backyard suites.

Balconies facing the street, no direct views of neighbouring yards.

Windows placed to provide views to the streets.

Direct access from the lane.

WITHOUT PARKING

Solar powered, award winninng backyard suites like the one pictured above, take the concept further while maintaining the massing and form reccomendations of the City.

(GENERAL PHOTO)

Infill development, understood as new construction in the established urban environment, is another mechanism through which the city can adapt to the evolving demands of its citizenry. Beginning in the late 2000s, the City of Calgary initiated a series of “monitoring programs for residential infill development producing various amendments to the rules of the Land Use Bylaw.” (Enabling Successful Infill Development, CPC20180888, p 1.)

In some policy statements, the City of Calgary has described these bylaw revisions as part of efforts to “support growth in our city while accommodating citizens’ needs” (Planning & Development Report to SPC on Planning and Urban Development, PUD20190402), demonstrating the perceived importance of a legal framework in the development of a built form

that is responsive to the city’s needs. Further, Council noted that there was a significant “gap between policy and regulation regarding low density forms of infill development…” (Ibid), a gap which review of the Land Use Bylaw was designed to address. One such area of deficiency was described as follows: “Built form can influence a desired behavior and can facilitate a desired experience. Current rules are not focused on creating specific experiences and as such, often create buildings that do not respond to the spaces in between the buildings.” (Ibid)

Location Map - Redevelopment

In 2019, the Council and the City Administration discussed 12 specific areas where the Land Use BYlaw could be amended to facilitate successful infill development. These areas included vehicle access, tree retention, and building height. These 12 areas are valuable as considerable discussion is publicly available on the rationale behind the bylaw changes, the intended effect on the built form and most were passed by the Council and are reflected in the current bylaw. Calgary's City Council viewed the "lack of front porches for existing and new infil homes" as a concern and wanted to incentivize more porches, while mitigating other issues porches raise. (CPC2018-088, p3) Simply, a major value underlying proposed Bylaw amendments was the creation of more porches, a value apparently not shared by unregulated market forces.

Administration argued that front porches should (1) provide an area that is a functional outdoor amenity space, (2) create a transitional space between the public realm and the private home, and

(3) not produce unintended consequences that would exacerbate other infill concerns such as massing and privacy (CPC2018-0888, p 4-5).

One amendment proposed to incentivize porch construction was an amendment to s. 336(5) of the Land Use Bylaw to allow a porch to project a maximum of 1.8 metres into a front setback area in Developed Areas (CPC2018-0888 Attachment 1, p 1). Administration suggested that this change would “encourage more homeowners to add a porch to their home” as under the previous regime porches could not project into a front yard setback unless a relaxation was requested. In this case, unlike bylaw amendments considered under sunlight regulation, or backyard suites. Administration hoped to use the bylaw to incentivize certain behaviour.

Aditional research examines the relationship between law and form in three further areas: towers and incentives, backyard suites, and infill redevelopment. In each of these examples, the law takes on a different role: imposing requirements, creating incentives, or providing a forum for contested notions of the city. Understanding the various ways in which law and form interact is crucial, as cityies select the best legal instrument to achieve policy outcomes. By shedding a light on the different ways this relationship can be characterized, the authors are advancing a body of research that enables us to effectively shape the cities of tomorrow.

The law therefore acts to create incentives for behaviour, or in the case of porches, to ease restrictions that may dis-incentivise individuals from building them. The fact that this type of regime is common in the examples considered demonstrates that the City uses law in an adept way. Rather than always using the law to prescribe outcomes, law can be used to incentivise behaviour that furthers policy objectives, and create a built form that is guided by the law, but not stifled by it.

Kirandeep Kaur

Master of Planning

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary

Benjamin Sasges

Juris Doctor Faculty of Law, University of Calgary

SUPERVISORS

Lisa Silver

Associate Professor Faculty of Law, University of Calgary

Fabian Neuhaus

Associate Professor

School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, University of Calgary

The city is the largest human-made physical artifact. However, how is its form to be explained? Is it randomly emerging as the result of thousands of independednt decisionos? or is it based on the creative whims of the designer elite as they strive to mark the world with their monuments? Or it it a cultural response to the local climatic and geographical circumstances?

This issue explores the role of law and regulation as the guiding factor in the emergent physical form of the built environment. A handful of these rules are critically analyzed. How they shape the urban form both purposively and unintentionally are being considered in this issue. Far from a unilateral imposition of power, the relationship between law and design is bilateral, with both components exerting influence on the other. For example, the common law principle of the right to ligh was explicitly excluded at the provincial level in Alberta. However, in Calgary, bylaws and community-specific plans create distinct rights to sunlight not found everywhere. In a residential context, the right to sunlight is used to contest a neighbor's aditions or increase in density. This and other aspects are discussed by analyzing specific examples in Calgary

While we prepare for our next engagement, keep in touch with us @NEXTCALGARY.