UPW

Black Women, Architects of the American Kitchen, Deserve a Rightful Place in the Sun

Black Women, Architects of the American Kitchen, Deserve a Rightful Place in the Sun

LENA WALKER BELL , 79, of Hephzibah, Georgia departed this life suddenly after a brief illness on Sunday, May 21, 2023. A beloved mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, sister, auntie, cousin, and friend, she was born to the late Mark Walker and Ruby Johnson Walker in Sardis, Georgia on June 10, 1943—the youngest of six children.

Lena received her primary and junior high school education in Sardis, Georgia and began high school in Waynesboro before withdrawing to care for her ailing mother. Undeterred by a yearslong delay in her education, Lena later earned her GED and began working in the field of health services and nursing. She retired from her position as a licensed practical nurse at Gracewood State School and Hospital in 2007 after thirty years.

She married Lucius Gordon,

Sr., in 1962, and they welcomed four children into the world. In 1977, she married Mitchell Bell, and welcomed

two more daughters. A dedicated worker throughout her life – whether in the cotton fields of Burke County or as a caregiver in the halls of Gracewood, Lena enjoyed winding down by reading, exploring on the computer and being in the company of her children. She also enjoyed volunteering with Cancer Support Services (formerly known as The Lydia Project) in Augusta.

Lena leaves to cherish her memory: six children, Lucius Gordon, Jr. (Candace) of Ogden, UT; Wycliffe Gordon (April) of Augusta, GA; Karen Gordon Thomas (Clarence) of Hephzibah, GA; Stephen Gordon of Santa Barbara, CA; Audrey Michelle Ali (Esaa) of Martinez, GA; and Tonya Bell of New York City; nineteen grandchildren, Ismael, Yusef, Attiyah, Celeste, Countess, LeBarron, Thomas, Cliff, Corey, Evan, Jaz, Cassandra, Daniel “Scooter”, Malcolm, Chris, Ryanne, Jamil, Jayden, Raheem; one great-grandson, Mason; one brother, Alvin Walker (Julia) of Fort Lauderdale,

and a host of nieces, nephews and friends.

She was preceded in death by her parents, two sisters; Marie Roberts and Rosie Lee Jenkins; two brothers, Alfred Walker, Sr. and Curlie Walker; a beloved nephew that she was raised alongside, Leroy Mincey; and a host of other beloved family, friends and loved ones.

A celebration of life was held at on Wednesday, May 31, 2023, at Broadway Baptist Church (2323 Barton Chapel Road, Augusta, GA) with Rev. Anthony Booker presiding and Rev. Alfred Walker officiating. Interment followed at Hillcrest Memorial Park. The family received family and friends the day before on Tuesday, May 30, 2023, at Kinsey & Walton Funeral Home Chapel, 3618 Peach Orchard Road, Augusta, GA. (706) 790-8858.

Please consider making a donation to Cancer Support Services at www. cancersupportservices.org.

Augusta Black Restaurant Week (ABRW) is proud to announce its return in 2023 with exciting new partnerships. The 2023 event, #ABRW23, will take place from June 12-18, and will highlight some of the area’s black-owned eateries and chefs, while giving patrons an opportunity to partake in specialty or signature items.

New partnerships this year include Visit Augusta, Yelp!, Juneteenth, and Food Truck Family Friday. Visit Augusta, the official destination marketing organization for the Augusta area, will provide additional marketing support to help promote ABRW23 and attract visitors to the area. Yelp!, a popular restaurant review and discovery platform, will showcase participating restaurants and help patrons discover new black-owned eateries in the area.

Juneteenth, a holiday celebrating the emancipation of slaves in the United States, will be celebrated during ABRW23, and will feature special events and activities in partnership with local organizations. Finally, Food Truck Family Friday, a popular food truck event series in the Augusta area, will team up with ABRW23 to bring together some of the area’s best food trucks for a fun

and casual food event.

In addition to these exciting new partnerships, ABRW23 will continue to feature prix fixe menu items, chef collaborations, and other activities designed to showcase the unique culinary talent of the area’s blackowned restaurants and chefs.

“We are thrilled to partner with Visit Augusta, Yelp!, Juneteenth, and Food Truck Family Friday for this year’s event,” said event coordinator, Olivia Pontoo. “Their support will help us to amplify our message and showcase the amazing culinary talent in our community. We can’t wait to share this year’s event with everyone.”

Participating restaurants and chefs, as well as a full schedule of events, will be announced closer to the event, so stay tuned for updates on the ABRW23 website and social media channels. Don’t miss this opportunity to experience some of the best food in the Augusta area, while supporting the local black-owned restaurant community.

For more information about Augusta Black Restaurant Week 2023, visit the event website at www.augustarestaurantweek.com.

•

•

•

A chef and food writer takes a hard look at the rare outliers who have achieved recognition for their cooking, and the inequity that still prevents most Black women from owning restaurants.

by Mecca Bos Civil EatsThere’s a moment in the 2009 animated Disney film The Princess and the Frog, when the main protagonist, Tiana, a New Orleans-born Black woman, is on the precipice of realizing her lifelong dream of owning a restaurant.

Then, a real estate agent, Mr. Fenner of Fenner & Fenner, who had been poised to sell Tiana her coveted restaurant space, tells her she has been outbid.

“A little woman of your . . . background would have had her hands full trying to run a big business like that. You’re better off where you’re at,” he tells her.

It doesn’t take much imagination to intuit what function that pregnant pause, and the word “background,” have in the scene. Disney, as much a mirror on American life as any media, was punctuating a disturbing American credo in that scene: the U.S., as represented by Mr. Fenner, thinks Tiana is better off as a laborer, nothing more.

After Mr. Fenner breaks the news, Tiana takes her place back behind the catering table at the Mardi Gras ball where she’s serving her specialty beignets. She trips and falls, all of the beignets she baked for the event go flying, and our heroine sits dejectedly in a dustbowl of powdered sugar and sorrow.

In his foreword to The Jemima Code, author Toni Tipton Martin’s presentation of more than 150 African American cookbooks, journalist John Edgerton wrote:

“Throughout 350 years of slavery, segregation, and legally enforced white supremacy, the vast majority of women of African ancestry in the South lived lives tightly circumscribed [to] . . . domestic kitchens. To them fell the overarching responsibility for the feeding of the South, as well as the duty of birthing and nurturing replacement generations.”

In the collection, Tipton Martin lays out another brutal conundrum: the image of the Black woman chef embedded in the cruel stereotype and barbarous invention of racism and in the caricature of the Mammy—a deceit that functions, in part, to bury the rich culinary gifts that Black women have given American cooking.

After years working as a chef, I did not see myself reflected in the food industry. Around four years ago, Tipton Martin’s book opened up my own personal search for other Black women in

food.

I quickly learned that I was not alone in my search. Modern American cooking enthusiasts have long been wringing their hands over the question of what “American” food actually means, and a growing number of chefs are circumventing the Eurocentric answer to that question and revealing actual Native American ingredients and cookery—ancient traditions hidden and all but destroyed by colonialism.

But the millions of Black women who picked up those Native ingredients and applied both the intelligence and traditions of Africa and those of Europe that were imposed on them have yet to garner rightful recognition in the pantheon of the American professional kitchen. Their toil and intellectual property have been as dismissed and concealed as that of any slave, their names sacrificed and lost to the American project.

Of the roughly 1 million restaurants in the country, for instance, about 8 percent are Black-owned. About 2,800 are owned by Black women, according to 2019 Census information. That’s less than a third of 1 percent of all American restaurants.

In his 2015 profile of Southern cooking doyenne Edna Lewis, journalist Francis Lam wrote,

“The elite homes of Virginia, going back to the days when the Colonial elite socialized with French politicians and generals during the Revolutionary War, dined on a cuisine inspired by France. It was built on local ingredients—many originally shared by Native Americans or brought by slaves from Africa—and developed by enslaved black chefs like James Hemings, who cooked for Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. Because this aristocratic strain of Southern cuisine was provisioned and cooked largely by black people, it came into their communities as well, including Freetown.”

Freetown was Lewis’s hometown, a Virginia homestead built by a community of formerly enslaved people, including her grandfather.

For anyone concerned with the legacy of the Black chef in America, James Hemings and Edna Lewis are familiar names. Lewis left Freetown during the Great Migration for Washington, D.C. and then New York, where she found work first as a domestic and then eventually as a cook in stylish restaurants,

which led her finally to her own restaurant and a cookbook deal.

In her cookbook The Taste of Country Cooking, Miss Lewis, as she was known, writes in almost ecstatically loving terms about her childhood in Freetown. She recalls details like the “moist smell of chickens hatching” and “the first asparagus that appeared on the fence row, grown from the seed the birds dropped.” Along with hundreds of others, these memories recall a life made of not just four seasons, but the many seasons that arrive each year, and with them, the resulting cuisine that was so endemic it was sacred.

But by the time she was 15, Lewis left Freetown as part of the Great Migration, an event often described as millions of people moving for a “better life.” In reality, 6 million African Americans fled the South in an effort to get away from white terrorism: the lynching and indentured servitude that made “free” life not much better than enslavement, and the destruction of their homesteads and farm properties to a degree that often resulted in starvation.

Miss Lewis likely didn’t leave her community as a child—for a place completely unknown to her—because she was in search of a better life. When she did leave, her dressmaking skills put her in circles with white socialites, including

an antiques dealer with whom she eventually became a partner in her first restaurant.

Tipton Martin, who had a chance to meet Miss Lewis before she passed away in 2006, told her that the world needed to know that there were a lot more people like her—they have just been invisible, hidden. Miss Lewis responded in a letter: “Leave no stone unturned to prove this point. Make sure that you do.”

So what of the millions of other women constrained to the American kitchen for 350 years, and what of their bequest? What of their descendants? Where are our restaurants and our book deals?

Not at all incidentally, Tiana’s mother in The Princess and The Frog works as a domestic and seamstress in the home of a wealthy white family in New Orleans’ opulent Garden District. When Tiana grows up, she works as a server and baker in a modest restaurant. At least Disney does not lie in this portrayal of Southern racial hierarchy in 1912. Though in 1926, at the height of the Great Migration, Tiana would have been more likely to wake up as a frog than be granted the keys to a restaurant. (Spoiler: in the film’s end, Tiana gets the prince and her dream business.)

But among the many tired anachronisms in the film (racist voodoo tropes, Bayou dwellers portrayed as toothless hillbillies, etc.) the most tired is its repetition of America’s favorite fusty nugget: If you just work hard enough, you can get what you dream of. The film doesn’t mention of the 400 years of work with no pay.

Criminally little about Black history, particularly antebellum Black history, has been told through the eyes of Black people. Harriet Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, was the first African American woman to publish her own slave narrative, in 1861. She had the extremely rare fortune of being taught to read and write by one of the women who owned her.

In the book, Jacobs recounts the plight of her grandmother, known as “Aunt Marthy:”

“She became an indispensable personage in the household, officiating in all capacities, from cook and wet nurse to seamstress. She was much praised for her cooking; and her nice crackers became famous in the neighborhood that many people were desirous of obtaining them. In consequence of numerous requests of this kind, she asked permission of her mistress to bake crackers at

Continued on next page

night, after all the household work was done. . . . The business proved profitable, and each year she laid by a little, which was saved for a fund to purchase her children.”

Jacobs goes on to describe how her grandmother’s mistress eventually asked to borrow the $300 she had saved. It was never returned, but the mistress did purchase a silver candelabra with the money, which likely got passed down to her own heirs over the generations. Aunt Marthy’s 10-year-old son was sold for around $700, about the cost of two candelabras.

This description of the condition of the enslaved female cook, housekeeper, waiting maid, and housemaid was a relatively benign experience, compared to the other sadistic abuses described in the book. But it begins to paint a picture of the legacy, or lack thereof, for the Black woman culinary worker in America.

The enslaved domestic servant after Reconstruction didn’t fare much better than the enslaved sugar mill and sugar plantation worker, who had no other choice but to go on to coerced labor or indentured servitude, working in the very same mills and living in the very same slave quarters.

For instance, by the 1880s, about 98 percent of Black women in large southern cities like Atlanta worked as domestics. In the 1912 essay, “More Slavery at the South,” an anonymous African American domestic woman contacted hundreds of other women like her and attempted to present a snapshot of their daily working lives. “The condition of this vast host of poor colored people is just as bad as, if not worse than, it was during the days of slavery,” she wrote. “Tho [sic] today we are enjoying nominal freedom, we are literally slaves.”

She describes 16-hour work days and adds that just as enslaved Black women were expected to acquiesce to rape and sexual harassment by their white masters, as rejecting advances by the man of the house, even under emancipation, was widespread grounds for termination. Many, if not most, Black women were raising children by their husbands as well as by the white men whose homes they worked in.

“You might as well say that I’m on duty all the time—from sunrise to sunrise, every day in the week I am the slave, body and soul, of this family,” the unnamed author wrote. “We are but little more than pack horses, beasts of burden, slaves! In the distant future, it may be, centuries and centuries hence, a monument of brass or stone will be erected to the Old Black Mammies of the South.”

To this day I don’t know of any such monument, with the additional added insult that the “Old Black Mammy” is itself an invented apparatus, in part to explain away the relationship between white men

and Black women. In actuality, domestic workers were likely to be underweight, not overweight, thanks to severely rationed food, light skinned, because household work was often assigned to mixed-race women, and young, because less than 10 percent of Black women lived beyond 50 during that time period.

When a Southern movement to erect such monuments and memorials began in the early 1920’s, Black protests voiced that a better memorial would be to extend the full rights of American citizenship to the descendants of these women.

It’s difficult to discern what the turning point was that ultimately gained Tiana ownership of her restaurant in The Princess and the Frog. After being turned into a frog and kissing the prince, she was transformed back into human form, and in short order, the restaurant, and the man, are hers.

Whilst still a frog, she sang, “I’m going to do my best to take my place in the sun when we’re human.” So maybe it was in that moment—when she was at long last recognized as human.

In 2023, when the most recognizable movement for Black rights goes by the slogan “Black Lives Matter,” I think we can mostly agree that we are still fighting for our lives to matter enough to be rec-

ognized as fully human.

By the Jim Crow era, as late as 1966, the one job open to Black women was as a maid who cooked, washed and ironed clothes, and cared for children, for as little as $20 per week. Though Black women domestic workers fought for better wages and conditions, Black women’s contributions to the project of American cookery hasn’t been reflected in a way that even begins to scratch the surface of the true history. And the industry seems content with this fact.

There were no better farmers at the end of the Civil War than the formerly enslaved people, who were captured from African countries for their agricultural knowledge and had done all of the planting, harvesting, and gardening that went to feed the big house, as well as their own communities and families. Similarly, there were no better cooks than Black women, who were at the helm of virtually every kitchen in the South. Forbidden from reading and writing, they would not have been cooking from recipes or formal technique, but by memory, or “by hand”—a skillset that none but the most proficient cooks and chefs can boast.

And while it’s true that many Black women wanted to move out of the domestic sphere when more lucrative and less oppressive jobs became available to them after the civil rights movement, I still have extreme difficulty understanding how America’s most proficient cooks still don’t have a piece of the restaurant ownership pie.

While the Mammy stereotype remains highly visible in American culture—with Aunt Jemima being the most prominent — the actual Black woman chef is, conversely, invisible.

The 2021, post-George Floyd New York Times article, “How High-End Restaurants Have Failed Black Female Chefs,” cites a study from that same year published by a nonprofit advocacy group for restaurant workers’ rights. It indicates that racial and gender biases compound to make it especially hard for

Black women to attain leadership roles in restaurants.

“Using Seattle’s restaurants as an example, the study detailed several factors—openly discriminatory hiring and training, implicit bias among employers and customers, a lack of networking and training opportunities—that prompt many Black women to leave the industry,” the article reads.

As the 20th century progressed, Black women went from the domestic service sector to performing similar duties in hospitals, schools, and restaurants, including fast food. Today, almost a third of Black women are employed as service workers, compared to one fifth of white women.

“We should imagine an America where the legacy of Black women’s intellectual property and centuries of culinary know-how gets applied to the restaurant world and a true American cuisine emerges.”

“Since the era of slavery, the dominant view of Black women has been that they should be workers, a view that contributed to their devaluation as mothers with caregiving needs at home,” wrote economics professor Nina Banks in a 2019 article for the Economic Policy Institute. “African American women’s unique labor market history and current occupational status reflects these beliefs and practices.”

“Of the roughly one million restaurants in the country, about eight percent are Black-owned. About 2,800 are owned by Black women. That’s less than a third of one percent of all American restaurants.”

“We should imagine an America where the legacy of Black women’s intellectual property and centuries of culinary know-how gets applied to the restaurant world and a true American cuisine emerges.”

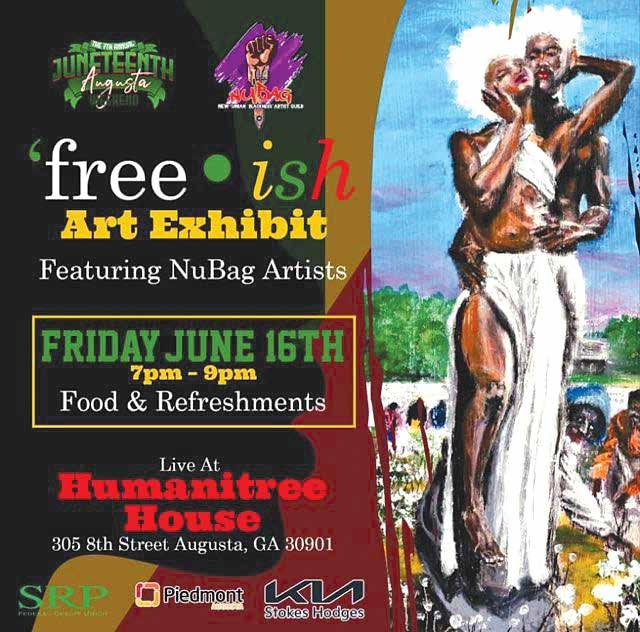

On June 19, 1866, formerly enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, celebrated a year of emancipation, or freedom, with the “Juneteenth” holiday.

Juneteenth celebrations quickly spread to the rest of the country, and the date continues to be the oldest known tradition honoring the end of slavery in the United States.

On June 19, 1865, U.S. Major General Gordon Granger performed a public reading of General Order Number 3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of person -

JUNE 19

Juneteenth Festival

Mon, 12 – 9 PM

Augusta Common, 836 Reynolds St

Augusta, GA

JUNE 17

Juneteenth 2023 Celebration

Sat, 10 AM – 5 PM

Augusta Museum of History, 560 Reynolds St

Augusta, GA

JUNE 19

Juneteenth — theClubhou.se

Mon, 9 – 10 AM

theClubhou.se, 100 Grace Hopper Ln Suite 3700

Augusta, GA

JUNE 17

Juneteenth 2k23 Celebration

Sat, 2 – 7 PM

Dyess Park, 902 James Brown Blvd

Augusta, GA

JUNE 17

Juneteenth Mega Festival

Sat, 9 AM – 11 PM

Your Neighborhood Builder, LLC, 25 Bogus Hill Road North Augusta, SC

JUNE 17

Juneteenth2023

Sat, 9 AM – 11 PM

The Landing on Bogus Hill Road, 23 Bogus Hill Road North Augusta, SC

al rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Granger’s announcement came two-and-a-half years after President Abraham Lincoln declared the end of slavery in states in rebellion during the Civil War with the Emancipation Proclamation. At the time, however, the United States could not free those enslaved peo -

ple held by Confederates. The event largely recognized as the end of the Civil War, and the Confederacy, was the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in April 1865.

As the Confederacy began losing the war, Texas became a refuge for enslavers to keep those they had enslaved. Texas was the westernmost Confederate state and one with little U.S. Army presence since there was little fighting there.

More than 150,000 enslaved people were forced to move to Texas. In Texas, formerly enslaved people almost immediately organized and purchased lands as “emancipation grounds” for the annual Juneteenth gathering.

Emancipation Park (formerly the Colored Emancipation Park)

in Houston, Emancipation Park in Austin, and Emancipation Park in Mexia (now Booker T. Washington Park) were all created as sites for Juneteenth celebrations.

But following Granger’s announcement of emancipation, not all was good news. Texas enslavers often delayed delivering the news of freedom until the harvest or the arrival of a U.S. agent. Other African Americans faced terroristic racial violence from the white populace.

Today, Juneteenth celebrations include picnics, rodeos, barbeques, parades, and readings of the Emancipation Proclamation and the work of African-American authors, such as Ralph Ellison, whose posthumously published second novel is titled Juneteenth

JUNE 17

Juneteenth Paint and Sip Sat, 6 – 8 PM

Stars and Strikes Family Entertainment Center, 3238 Wrightsboro Rd

Augusta, GA

JUNE 17

Juneteenth Firework Show — Umoja Village Sat, 2 – 9 PM

Aiken, SC

JUNE 23

Juneteenth Movie Night Fri, 6 PM

The Center for African American History, Art and Culture, 120 York St NE

Aiken, SC

JUNE 16

1st Annual Juneteenth Players Ball Fri, Jun 16 – Sat, Jun 17 Luxe, 813 Broad St

Augusta, GA

JUNE 17 Augusta Civil Rights Activist Sat, 12:30 PM

Augusta Museum of History, 560 Reynolds St

Augusta, GA

JUNE 19

Juneteenth Open Mic ~ Music ~ Poetry ~ Hip Hop ... Mon, 8 – 11 PM

Augusta

Augusta, GA

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp awarded $3.8 million to the Augusta Parks and Recreation Department from the Improving Neighborhood Outcomes in Disproportionally Impacted Communities grant for two park improvement projects:

Boykin Road Park - $1,669,031 will be used to revitalize Boykin Road Park in the Dallas Heights subdivision from an athletic park to a passive park. Features include comfort stations, picnic shelters, a walking track, a sustainable playground with an interactive water feature, new lighting, and a community garden with outdoor fitness equipment for seniors. Those improvements will provide opportunities for children, adults, and seniors to play and exercise together, enjoy the outdoors, and gather with community members.

May Park - $2,200,000 will be used to add additional parking, a picnic shelter, seating, and a walking track, replace the old comfort station, tennis and basketball

courts, and the grills. In addition, the awarded grant funding allows for improvements inside the community center. These improvements include renovations to the restrooms, locker rooms and steam rooms. These upgrades will make the community center more attractive for group exercise.

“We are in the middle of construction of the new Henry Brigham Community Center, just finished improvements to Jamestown Park, and replaced the playground at the community center in Blythe; we will begin improvements at Fleming Park and Dyess Park shortly and now we can add two more projects that will benefit our entire community” says Maurice McDowell, Director of the Parks & Recreation Department.

In addition to the two park improvement projects, the City of Augusta is also receiving $1,766,336 in grant funds to bridge recreation and commerce in Downtown Augusta. The Jones Street Alley project will create a direct connec-

(At Right) May Park - $2,200,000 will be used to add additional parking, a picnic shelter, seating, and a walking track, replace the old comfort station, tennis and basketball courts, and the grills tion between Jones Street and the Augusta Common. Added sidewalks and alley space will provide opportunities for more community events and improve foot traffic between the central business district, the convention center, and the Augusta Common. This is a collaborative project between the City of Augusta, the

Downtown Development Authority of Augusta, Cranston Engineering, and private property owners.

Interim Administrator Douse stated, “Augusta appreciates the funding and confidence Governor Kemp has invested in our community, we will make certain the projects are reflective of such.”

Karen Brown, a former professional ballerina, artistic director, current university professor and founder of En Pointe Plus (EPPSM) Dance Mastery Institute (www.karenbrowndancemastery. com) is looking for a highly organized and productive Program

Coordinator for the 6th Annual Sand Hills Summer Youth Program. Week 1 runs June 12 - June 16, 2023 and Week 2 runs June 26, 2023 - June 30, 2023. Must have strong office and communication skills.

I require a go-getter who is equally capable of administrative work, running errands and assisting with sessions and workshops for middle school students.

I’m looking for a driven and ambitious individual.

So, if you are…

• A fast learner, impeccably organized, incredibly productive

• Results-oriented and punctual

• A great communicator, both written and verbal

• A sponge when it comes to learning

• Positive and personally powerful with a valid driver’s license

You’ll be able to manage the following responsibilities which include but are not limited to:

• Answering phones, answering daily emails, purchasing program supplies, electronic filing, scanning, drafting letters, managing databases, assisting with scheduling, and limited bookkeeping.

• Extensive experience with research on the Internet, use of Mac, or PC

• Competent in Microsoft Office (particularly Excel)

• comprise and send out daily schedule to all participants and post schedule at the Program site

• communicate with parents

• organize and coordinate field trip transportation with Board of Education sponsors

• Send thank you letters and mail prizes to online winners

• Create Certificates of Appreciation

• Coordinate with the program site manager and all vendors, guests and reporters around the culminating events on Friday 6/16 and 6/30/2023.

Assistance with dance training workshops:

• Set up the studio for daily practice.

• Manage participant Check in and Check out.

• Maintain and update the “In Case of Emergency” File

• Schedule the Adult volunteers (2 each day)

• Review participants homework assignments

Must have access to the Internet, your own computer, and a cell phone.

1) In a cover letter, explain your past experiences that make you the right person for this job. You have one page, single spaced, 12-point font, Times New Roman font, to make your case.

2) Include a 1-page resume.

3) Email your two-page total submission to enpointeplus@gmail.com with the subject title:

“Personal Administrative Assistant”

Compensation:

Starting rate $15 per hour. $20 per hour during the weeks of the program. References are required.

Thank you for your interest!

--Sincerely,

Karen Brown, Founder, En Pointe Plus Dance Mastery InstituteA permanent display case for the Washington Quilt was has been installed at Augusta University’s Reese Library. The quilt honors local educators Drs. Justine and Isaiah “Ike” Washington for whom Washington Hall is named. The Augusta University Libraries would like to thank Nancy Glaser and the Augusta Museum of History for the construction and installation of the case, and thanks the library staff members (Thomas Weeks, Courtney Berge, Melissa Johnson, Katlyn Tuten) and the IT students (Jamie Navarro and Sam Allen) that helped move the case safely from the parking lot and into the library. The Washington Quilt can be viewed during the library’s normal operating hours. For more information on the quilt checkout process and procedures, please contact Special Collections Librarian Courtney Berge at 706-7371475 or cberge@augusta.edu.

Augusta, is hosting its second annual Augusta on Display community engagement forum for citizens to learn about the services offered by the city and give feedback on the municipality’s proposed budget.

BACKGROUND: During the three-hour trade show style event, the public will have a chance to meet their elected officials, have one-on-one conversations with representatives from city departments, and share their opinions on how the city should spend tax dollars. Additionally, there will be bouncing houses for children, health screenings, family-friendly entertainment, and attendees will have the opportunity to tour a variety of government vehicles.

WHEN: June 3, 2023, from 9am-12pm

WHERE: Julian Smith Casino, 2200 Broad Street.

AUGUSTA

The Richmond County School System (RCSS) will host a summer career fair to recruit employees for open positions on Saturday, June 10. Recruiters and hiring managers will be on-site to conduct interviews and discuss open positions.

“We are looking for some talented and dedicated individuals to join our high-performing workforce to support the educational offerings and resources needed to educate more than 30,000 students. Our employees are eligible for excellent benefits, and we offer professional development and a collaborative work environment,” says Dr. Cecil Clark, Richmond County School System Chief Human Resources Officer.

The job fair will be held in the Westside High School gymnasium, 1002 Patriots Way, from 9 a.m. –12 p.m.

The next Walk-In Wednesday job fair will be held on July 12 at 864 Broad St., from 9 a.m. – 12 p.m.

To view the complete list of openings, visit our website at rcboe.info/Work4RCSS.

RICHMOND COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

Bond Issue Program

PROPOSAL NUM.: B-21-026-4050.2

PROJECT NAME: Blythe Elementary School Roofing Replacement

Sealed proposals from Contractors will be received for the B-21-026-4050.2 – Blythe Elementary School Roofing Replacement by the County Board of Education of Richmond County at the address below until 3:00 PM local time, June 27, 2023. This will be a public bid opening, read aloud in the Richmond County Board of Education Conference Room located at 864 Broad Street, Augusta, Ga. 30901. No extension of the bidding period will be made.

A Pre-Bid Conference will be held June 13, 2023 @ 10:00 AM local time in the Media Center Conference Room, Blythe Elementary School, 290 Church Street, Blythe, GA 30805.

Drawings and project manual on this work may be examined at the Department of Maintenance and Facilities, Richmond County Board of Education, 2956 Mike Padgett Hwy., Augusta, Georgia 30906.

Bidding documents may be obtained at the Office of the Architect: 2KM Architects, Inc., 529 Greene Street, Augusta, Georgia 30901. Applications for documents together with refundable deposit of $125.00 set should be filed promptly with the Architect. Bidding material will be forwarded (shipping charges collect) as soon as possible. The full amount of deposit for one set will be refunded to each prime contractor who submits a bona fide bid upon return of such set in good condition within 10 days after date of opening bids. All other deposits will be refunded with deductions approximating cost of reproduction of documents upon return of same in good condition within 10 days after date of opening bid.

Contract, if awarded, will be on a lump sum basis. No bid may be withdrawn for a period of 35 days after time has been called on the date of opening.

Bid must be accompanied by a bid bond in an amount not less than 5% of the base bid. Personal checks, certified checks, letters of credit, etc., are not acceptable. The successful bidder will be required to furnish performance and payment bonds in an amount equal to 100% of the contract price.

In accordance with the Davis-Bacon Act, and the General Wage Determination’s available from the DOL for Richmond County (www.wdol.gov), the Contractor will be required to comply with the wage and labor requirements and to pay minimum wages in accordance with the schedule of wage rates established by the United States Department of Labor. The highest rate between the two (Federal and State) for each job classification shall be considered the prevailing wage.

The Owner reserves the right to reject any and all bids and to waive technicalities and informalities.

To promote local participation, a database of Sub-contractors, Suppliers, and Vendors has been developed by the Program Manager, GMK Associates. Contact Jeanine Usry with GMK Associates at (706) 826-1297 for location to review and obtain this database.

Bids shall be submitted and addressed to:

Dr. Kenneth Bradshaw County Board of Education of Richmond County Administrative Office 864 Broad Street, Augusta, Georgia 30901 c/o: Mr. Bobby Smith, CPA

Dr. Lewis spoke about her new book Light and Legacies: Black Girlhood and Stories of Liberation

Janaka Bowman Lewis, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of English, Interim Chair of Writing, Rhetoric and Digital Studies and Director of the Center for the Study of the New South at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Freedom Narratives of African American Women (2017), and three children’s books Brown All Over, Bold Nia Marie Passes the Test, and co-author of Dr. King is Tired, Too!! Her latest book is Light and Legacies: Black Girlhood and Stories of Liberation, which is out in bookstores now.

RICHMOND COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

Bond Issue Program

PROPOSAL NUM.: B-21-026-4050

PROJECT NAME: Blythe Elementary School HVAC Replacement

COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION OF RICHMOND COUNTY INVITATION TO BID

Sealed proposals from Contractors will be received for the B-21-026-4050 – Blythe Elementary School HVAC Replacement project by the County Board of Education of Richmond County at the address below until 3:00 PM local time, June 27, 2023. This will be a public bid opening, read aloud in the Richmond County Board of Education Conference Room located at 864 Broad Street, Augusta, Ga. 30901. No extension of the bidding period will be made.

A Pre-Bid Conference will be held June 13, 2023 @ 11:00 AM local time in the Media Center Conference Room, Blythe Elementary School HVAC Replacement, 290 Church Street, Blythe, GA 30805.

Drawings and project manual on this work may be examined at the Department of Maintenance and Facilities, Richmond County Board of Education, 2956 Mike Padgett Hwy., Augusta, Georgia 30906.

Bidding documents may be obtained at the Office of the Architect: 2KM Architects, Inc., 529 Greene Street, Augusta, Georgia 30901. Applications for documents together with refundable deposit of $100.00 set should be filed promptly with the Architect. Bidding material will be forwarded (shipping charges collect) as soon as possible. The full amount of deposit for one set will be refunded to each prime contractor who submits a bona fide bid upon return of such set in good condition within 10 days after date of opening bids. All other deposits will be refunded with deductions approximating cost of reproduction of documents upon return of same in good condition within 10 days after date of opening bid.

Contract, if awarded, will be on a lump sum basis. No bid may be withdrawn for a period of 35 days after time has been called on the date of opening.

Bid must be accompanied by a bid bond in an amount not less tha n 5% of the base bid. Personal checks, certified checks, letters of credit, etc., are not acceptable. The successful bidder will be required to furnish performance and payment bonds in an amount equal to 100% of the contract price.

The Owner reserves the right to reject any and all bids and to waive technicalities and informalities.

To promote local participation, a database of Sub-contractors, Suppliers, and Vendors has been developed by the Program Manager, GMK Associates. Contact Jeanine Usry with GMK Associates at (706) 826-1127 for location to review and obtain this database.

Bids shall be submitted and addressed to:

Dr. Kenneth Bradshaw County Board of Education of Richmond County Administrative Office

864 Broad Street, Augusta, Georgia 30901

c/o: Mr. Bobby Smith, CPA

AUGUSTA

A.R. Johnson Health Science and Engineering Magnet School senior Jonathan Ross, Jr., has been named a 2023 Gates Scholar.

Ross said, “I feel honored to be a Gates scholar after all of my hard work and perseverance. As a result, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation will pay for my full tuition at Morehouse College. As I am blessed with this opportunity, I will take full advantage of it as I work towards earning a degree in computer science.”

The Gates Scholarship awards high-achieving students of color with a last-dollar scholarship that funds the full cost of college attendance that is not covered by federal student aid or family.

Ross is the salutatorian of his graduating class at A.R. Johnson Magnet School. In addition to The Gates Scholarship, he earned the College Board National African American Award, the F. Wayne Clough Georgia Tech Promise Program Scholarship, the Black Scholar Recognition Award from Augusta State University, and a scholarship from Morehouse College. He is a member of the Augusta Youth Leadership Program, the National Honors Society, and a student athlete.