THE ARTIST GENE

The knowledge, creativity and know-how of multiple generations enriched Chris and Matthew Cox’s childhoods. Now this legacy infuses and informs their work in furnishing the future for generations yet to come.

Every few days, when the Cox brothers were growing up in England, their father would lug home some new treasure, extolling its virtues and unwittingly sowing the seeds of his sons’ futures. “He was always off buying and he’d come back with fantastic things,” Chris says. “‘Look at this, Matthew. Look at this, Chris!’ You’ll never see an example as good as this,’ he’d say, and we could feel his enthusiasm.”

The Cox boys were so immersed in the antiques trade that its influence proved inescapable and utterly inspirational. And they weren’t the only ones. No fewer than 12 members of their immediate family are or were notable antique dealers, especially their father, Robin, and grandfather, Ralph, who literally wrote the book on Victorian tinware with a tome he authored in 1970, but also their grandmother and various aunts and uncles. It was how Robin and their mother met. It was what the boys lived and breathed, a tide in which they became strong swimmers. “You could say it’s in the family bloodstream,” Chris says. “But it’s more that there was nothing else in our veins. It’s all we know.”

Well, not exactly true. Chris, a sculptor/maker and partner with his artist wife Nicola in Cox London, and Matthew, an antiques dealer who now has a furniture workshop, know a lot about a wide variety of subjects, much of it learned by osmosis from their dad, as well as from their mother, Pearl Bugg, who pitched in for the family business by restoring and recoloring pieces, a practice that later led to her own artistic pursuits.

A delightful woman with an endearing name to match, Pearl Bugg is a self-taught master of many things: renovating, gardening and floral design, and especially painting. Her charming animal portraits, primarily birds and dogs with a smattering of barnyard beasts, render the animals’ distinct personalities. When the kids were younger, however, and her restless husband was either off on the hunt or busy buying and selling properties (the family moved five times), she not only managed the household but often did the plumbing and house painting.

Between finding, making and doing, the scrappy Cox family developed an acumen fitting for their environment—their fantastically antique hometown of Stamford, Lincolnshire, an ancient market town right out of a period movie set (which it has been many times over). With the soul of old things permeating their every pore, the boys developed a love and appreciation for time-honored craftsmanship, materials that last, the beauty of patina, the power of an object’s evolving history as it is passed from generation to generation. And with this shared passion, Chris and Matthew set off on diverging yet complementary paths.

Ralph Cox’s original shop in Barton-upon-Humber, 1952.

The Stamford shop of Chris and Matthew’s grandparents, Ralph and Olive, 1971.

Olive arranging jewelry in the shop window.

THE COX BOYS WERE SO IMMERSED IN THE ANTIQUES TRADE THAT ITS INFLUENCE PROVED INESCAPABLE AND UTTERLY INSPIRATIONAL.

Busts survey Ralph Cox’s stand at the Chelsea Antiques Fair, 1967.

Jagger greets Chris and Nicola in their bedroom where a favorite tapa cloth from Tonga hangs.

Opposite, left: Chris fabricated an iron base, inspired by the work of Gilbert Poillerat, for the voluptuously scalloped 19th-century stone basin converted into a sink for the primary bathroom.

Opposite, right: Ogun chairs surround the Reed dining table (all Cox London creations) which supports artistic endeavors every bit as much as dining.

As artists who can’t remember a time when they weren’t fabricating things, Chris and Nicola fully embrace the moniker of “maker.” Their material of choice is metal—steel for Chris and bronze for Nicola. “It’s rare to have ferrous and non-ferrous in the same workshop,” says Chris. “Nicky’s always been the bronze founder and I’ve been the forger and fabricator since I was better at welding. We’re a perfect team in that respect.”

Their collaboration started while both were studying and experimenting in the three-year sculpture program at Wimbledon School of Art. Nicola was always primarily interested in casting, exploring plaster and cement fondue before igniting her interest in the bronze foundry at school. Chris, meanwhile,was busy making objet trouvé by welding scraps, pulling from a towering heap of metal at school, much as he did in high school after discovering an enticing cache of raw materials at the edge of a field in Stamford, a pile of stuff too rusty or broken to be of use to the farmer who dumped it. “I made animals mostly, horse heads, lifesize goats,” Chris says. “It’s what got me into art school.”

On visits back to Stamford, he would also plunder his father’s and grandfather’s troves of antique books and auction catalogs. “One of Ralph’s great passions was metalwork—tinware, ironware, the humble as well as the fine, the older the better,” Chris says. “Along with a great eye, he had a wonderful library covering everything from the work of Renaissance sculptors to that of Alexander Calder, always one of my faves.” Because these catalogs tended to be mostly about lighting, Chris has been intrigued by chandeliers and other forms of fixtures from the very

beginning. Right out of school, he worked for an antique restorer of metal, primarily chandeliers, in London’s East End. In one short week he felt he’d found his life’s work. “All of the components and parts of lighting, creating it from scratch, asking dealers how much it would cost to restore a fixture—these were things I understood. I’d seen these materials around my house; I’d overheard my father and grandfather discussing all these things.”

But Chris still had to learn the brass tacks: threading, lathe operation, silver and lead soldering, polishing, lacquering, patinating, gilding, wiring. Nicola meanwhile, having furthered her knowledge by working for a glass artist back home in New Zealand, was heading up the wax room at a foundry in the Docklands, and honing the many skills demanded of bronze casting (a process with at least six steps) each of which is critical and exacting.

It was, for both of them, an essential period of “learning and earning,” Chris says. “But really all we wanted to do was make what we wanted to make.” Nicola still tends to start a piece with narrative, with ideas constantly germinating from a rich compost of information and knowledge. Chris, on the other hand, dives right into the making. Initially the two primarily created furnishings needed for their little Victorian house, the kinds of things that are still Cox London’s sweet spot: clean-lined furniture, lighting inspired by the antiques Chris grew up around and mirrors. But it is pieces like the Floral chandelier that most exuberantly express his and Nicola’s sculptural core, flights of imagination and desire to create pieces with personality and soul.

Chris and Nicola’s eclectic sitting room featuring multiple pieces made in their own workshop, including an octagonal coffee table, bold andirons and iron picture rails. An Oculus mirror and an antique sofa were acquired from Chris’s brother Matthew.

Exquisite tangles of branches, leaves, buds and blossoms, forged of iron and brass, subtly lit from within, hover over a table like an impossibly lush nest set adrift on a current of air. The eight months it took to work out the initial design was time well-spent; the chandelier put Cox London on the map. “Nicky and I both love nature and wildlife,” Chris says. “It’s definitely something my mother instilled in me.” A conservatory at the back of their current Edwardian terrace house in north London brims with palms and succulents much like those Chris grew up learning to nurture, minus the lizards and iguanas he had as a boy.

Plants, like these in the conservatory, are key occupants of the Cox house, just like they were in Chris’s childhood homes.

The natural, freeform design of the Magnolia chandelier contrasts with more structured geometric candlesticks.

Around the corner from a spectacularly graphic 1940s Fijian ‘tapa’ that nearly covers a wall of the living room hangs a large Brighton station lantern, a Cox design based on an antique.

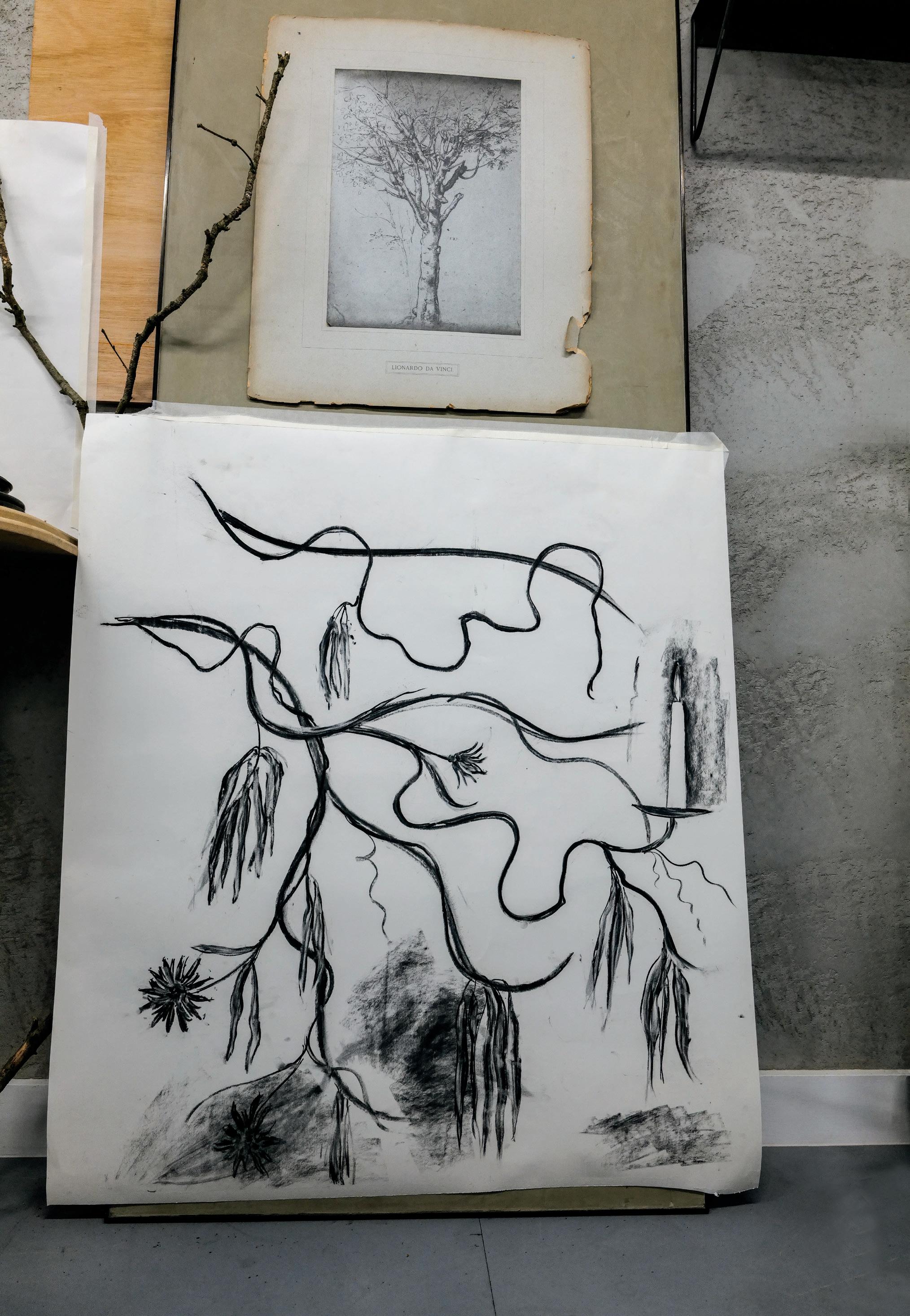

Nature is a number one inspiration as evidenced by a drawing by Chris and an etching of a tree by Leonardo da Vinci.

A lasting impression.

All of it is stuff to feed the imagination, natural forms that first find their way onto paper before blossoming into three dimensions from the drawings that Chris and Nicola create. Through materials as old and weighty as time—bronze, brass, stone, glass—and a deep understanding of patination, they miraculously capture the evanescence of nature in a form that can last forever.

Aided by a team of skilled makers in their ever-expanding Tottenham workshop, Chris and Nicola are turning out pieces for the ages, on display in their Pimlico Road showroom, territory Chris knows well. “Since I was ten years old, a good half a dozen major dealers on this road used to call on my father,” he says. Now all sorts of dealers and designers call on Chris and Nicola in London and Matthew in Stamford, eager to soak up another generation of Cox acumen and eye.

Chris and Nicola in the workshop.

This spread: The artistry and industry behind the creative process of Cox London.

Matthew Cox and Camilla McLean flank Matthew’s mother, Pearl Bugg, in the front parlor of their Georgian house.

Like Chris, Matthew’s upbringing with all things old has led to his 26-year career as an antiques dealer. He attributes his passion and joy to the fact that “provenance or no provenance, every piece has a story to tell.” And often, in his hands, a new life to live. Though not a “maker” per se, Matthew is a first-rate adapter. He sees “stuff sitting around with no obvious use”—architectural elements and industrial parts, for example, and gives things a fresh purpose, elevating recycling to upcycling.

An air vent from a factory roof is reborn as a superscaled convex mirror with a broad verdigris frame. A column, cut down, becomes the base for a table. Nineteenth-century metal components are fashioned into modern-day pendant lights. A hollow brass stair rail cut into segments is remade as multiple wall sconces.

And then there are the straight-up old pieces he loves for their simple form and strong character. He’s drawn to the functional: chairs and benches, cupboards and cabinets, sconces and lanterns, and timeless sturdy tables like the Living Island, a kitchen workhorse inspired by one in the Old Kitchen at Burghley House, one of England’s grandest Elizabethan houses just down the road.

Pearl’s rendering of the house hangs above a radiator with a custom cover by Matthew that echoes the splat balusters of the original stairway.

Beyond The Articulate table in oak hangs The Konami cabinet, inspired by utilitarian Japanese furnishings. In the foreground, the Vesper light in a verdigris finish.

Matthew and “Meelie’s” entry hall in Stamford features multiple pieces made in their workshop just down the road.

Matthew was probably stirred to make such a table because as a child, he’d come home to find the kitchen table, or some other major piece, sold and gone,” speculates Camilla McLean, his partner and prodder-in-chief. “I’m a great believer in going with the flow, being at the mercy of what falls in my lap,” Matthew confesses. “Camilla is the one who puts things in front of me and says, next, next!”

“Next” currently means working on their largest antique to date—a magnificent Georgian house in the center of Stamford that Matthew had frequently walked by as a boy and admired for decades. Together they are peeling back layers and returning rooms to their original lean beauty, for their own use and to serve as a showcase for their antiques and furniture collections. A mid-19th century glass-fronted tack cabinet from the stables of an English country house now commands a wall of the kitchen. The Galley lantern hangs in the front hall, Vesper lights climb the stairs.

A newly-made Orangery table anchors the main reception room where Oggy, their adorable schnauzer, circles around Chippy, a stuffed mohair “sibling” beneath Pearl Bugg’s portrait of a King Charles spaniel. Levity and wit counters the heft of the oak table flanked by antique benches—a table much like the one that spun Matthew off in a new direction a decade ago. “Someone had seen an antique refectory table on my website that was sold, and asked if it was possible for it to be reproduced. I found a joiner to make the table, and it turns out the buyer’s son worked for designer Martin Brudnizki, and before we knew it, we had orders for 20-seater tables for 10 restaurants.”

One of the most distinguished houses in Stamford, the exterior has been little altered since it was built in 1674.

Schnauzer Oggy with his steadfast stuffed chum, Chippy.

The view from the stair hall takes in an extended garden along with the rooftops and steeples of Stamford.

New lighting designs by Matthew Cox slip in quietly among the antiques including furniture, paneling and a fireplace mantle above which hangs a painting by Pearl Bugg.

Antique benches flank a bespoke table by Matthew. The hand-blown globe of the wallmounted Loupe light subtly reflects the space.

This launched Matthew’s furniture production offshoot, which exemplifies his savviness in glorying in the past without being trapped by it. With furniture, he believes it’s hard to improve on classic forms, however his business practices are forward thinking. His website, for example, is a beguiling blend of handsome pieces shown in monastic settings accompanied by 3D augmented reality features that allow clients anywhere to see furniture in various materials and finishes as well as in their own homes.

Becoming fully sustainable, i.e. eliminating the need for printed catalogs, showrooms, sample furniture, even inventory, is his ultimate goal, a challenge outlined in his 100-Year Plan. That means considering nature with every purchase, passing on skills, creating finishes that only grow more beautiful with time, and not only making furniture to order, but repairing, restoring, re-purposing and reselling it for as long as it, or his company, exists. In other words, making furniture to last generations, both materially and aesthetically.

“A hundred years is our benchmark,” Matthew says. “We often handle furniture this old, so we know that by using similar materials and techniques we can ensure longevity.” In the Maker’s Handbook given to every team member, he invites them to consider that “one day in the future our furniture will belong to an entirely different generation, and we want our pieces to be just as loved and useful then as they are today.” Matthew could just as easily be speaking for Chris and Nicola. Through all of them, the Cox credo lives on.

Sanding the Orangery table to a silky smoothness.

Matthew in his workshop.

This spread: The workshop is an organized array of forms, tools, drawings, pieces in process and finishes, handled by a team of makers, finishers and their apprentices.

Camilla’s homemade soup shared in mugs accompanied our workshop tour.

Pearl Bugg, brush in hand, in her Stamford studio.