W

W

W

W

W

Suggested Citation: United Planning Organization. 2024. 2024 Uniting people with opportunities report: a DC needs assessment

W

W

W

W

W

Suggested Citation: United Planning Organization. 2024. 2024 Uniting people with opportunities report: a DC needs assessment

UPO’s 2024 Uniting People with Opportunities Report: a DC Needs Assessment will be the guiding force that will lead UPO to its vision of Washington, DC: “a city of thriving communities and self-sufficient residents.” The community needs assessment will serve as a tool that UPO uses to achieve that vision, through the assessment of current needs, programs, and issues impacting low-income residents.

UPO is grateful for the input from the communities we serve along with our community partners, which includes government agencies, businesses, and other stakeholders. UPO has and will continue to collaborate with our partners across the city to ensure a better understanding of community needs, while also diagnosing the systemic barriers that prevent low-income residents from achieving economic security. Input that reflects the diversity of District residents is incorporated into this needs assessment to capture the varying experiences and opinions of District residents.

Like the community needs assessments that have come before, the 2024 community needs assessment provides background research, innovative qualitative and quantitative analysis, as well as the identification of trends. The assessment also includes recommendations to improve low-income residents’ access to resources needed to attain economic security. The assessment offers insights into how UPO targets its resources appropriately and where necessary. As new problems emerge, UPO will be on the forefront of innovative program development and resource distribution.

The UPO Board of Directors is proud to serve residents of the District of Columbia. Made up of a diverse group of District residents who are mayoral appointees, elected members, and private sector representatives, the Board uses its collective and individual knowledge and experience to govern an agency that has become an institution in the District of Columbia. We will continue to prioritize the inclusion and maximum feasible participation of residents with low incomes in agency decisions through our board leadership. Accountability to the community and our constituency have allowed us to stand the test of time in this great city.

On behalf of the UPO Board, I am grateful to serve an organization like UPO in our city, and I look forward to seeing a thriving community of economically secure residents.

Since the release of our 2021 Community Assessment, the District of Columbia has entered a pivotal transitory period where residents, community organizations and leaders are rethinking the future of our city since the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, we are excited to deliver our tri-annual, 2024 Uniting People with Opportunities Report: A DC Needs Assessment, which highlights the struggles and triumphs of low-income residents in the District. UPO conversed with stakeholders throughout the city through surveys, interviews and focus groups to gain understanding. The qualitative and quantitative data collected will serve as the cornerstone of UPO’s advocacy pursuits and program development. Public feedback is an essential process for the organization, as residents and former customers play an integral role in defining UPO’s work.

Surveys, interviews and focus groups were conducted both virtually and in-person, providing unique insights into the needs of struggling communities across the District. Throughout this report, UPO provides high quality research on the barriers surrounding poverty, the needs forming as a result of those barriers, and potential solutions to help residents with low-income to achieve economic security in overcoming their personal barriers. Over the past three years, UPO has continued to aid individuals seeking a better life through life changing programs and community support. With the insight provided by the 2024 community assessment, UPO will use the community feedback and guidance to assess our programs’ effectiveness at removing systemic barriers preventing low-income residents from achieving economic growth and security.

UPO has grown into one of the District’s largest poverty fighting organizations through our established connections with low-income communities, community partners, and local leaders. Our dedication to community-based advocacy and grassroots mobilization has helped policy makers and community organizations identify key issues facing low-income residents. We hope to use our extensive and inclusive collaborations to advocate for policies that directly eliminate the systemic barriers facing our customers.

I hope that this needs assessment highlights both the struggles and triumphs experienced by the communities we serve. We will continue to serve our customers with high quality programming and wrap around services that are proven to make an impact.

UPO would like to acknowledge the contributions to this report made by UPO staff including UPO’s Social Science Research Analyst, Connor Zielinski, under the direction of the Office of Resource Development and Research, Kevin Bryant. Additional support was provided by UPO staff and direction of the Office of the Executive Vice President and Chief Impact Officer; the Community Impact Division; the Office of Performance Management; and the Division of Advocacy and Volunteerism, among other staff persons of UPO offices and divisions.

UPO would also like to acknowledge the many DC residents who participated in focus groups and completed surveys for this needs assessment. For a complete list of contributing staff, volunteers and partners, see the Appendix.

The District of Columbia has had two years to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the pandemic waning in the public’s mind, COVID-19 has left a lasting impact on the District. Those who are experiencing poverty are now struggling more than ever, as the city currently gripes with a weaker economic forecast in the upcoming years. However, even with a potential economic downturn looming, the District continues to get richer. Over the past three years, the median income of a DC household of four has increased and now sits above $100,000 a year. For reference, the average household of four across the country is $70,000. Yet, that economic growth is not distributed equally across the District.

Poverty in the District is a direct result of systemic forces limiting the potential economic security of Black and Brown residents. At every turn, the District has barriers preventing socioeconomic equality between residents. Behind poverty are historical forces such as discrimination, systemic racism, social inequality, vulnerability due to health status, adverse experiences and economic changes. Despite poverty rates generally declining within the District, poverty is still an existential challenge that has only become harder to overcome, especially for Black and Brown residents. For example, the unemployment rate for white residents has never increased over four percent. The unemployment rate for Black and Brown residents has never fallen below 8%. The disparity between economic outcomes between white and Black and Brown residents has been well documented and the problem continues to persist after the pandemic. Research presented in this community assessment highlights trends that reveal the state of poverty in the District, the essential needs of District residents that are not currently being met,

and the ways UPO is working with families and communities to help them achieve economic security.

As the District of Columbia’s sole Community Action Agency, UPO is responsible for helping all residents with no or low incomes meet their needs and work towards economic security. UPO is also accountable to the federal government through the requirements of the Community Services Block Grant (CSGB).

Results-Oriented Management and Accountability (ROMA) was introduced as the community action network’s response to the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) and comprises practices that are now a part of the 1994 amendment to the Community Services Block Grant Act. The amendment specifically requires that CSBG-eligible organizations like UPO provide “A description of outcome measures to be used to monitor success in promoting individual and family economic security, and community revitalization.” These three areas are articulated in the three overarching goals of Community Action, as described by the National Community Action Network Theory of Change:

Goal1: Individuals and families with low incomes are stable and achieve economic security.

Goal2: Community where people with low incomes live are healthy and offer economic opportunity

Goal3: People with low incomes are engaged and active in building opportunities in communities.

As part of the ROMA framework, Community Action Agencies identify and address all needs by three levels at which they belong, namely:

Family level need

Community-level need

Agency-level need

Every three years, the United Planning Organization must complete a Community Assessment (CA). The CA will shape the future direction of the organization by informing staff, managers and executives about key trends that are developing across communities that are facing poverty. Moreover, the CA will inform UPO of the necessary programs and activities that are essential for aiding struggling communities. The assessment’s focus on identifying both the needs and

resources that communities experiencing poverty require will help determine the appropriate resource allocation necessary for future supports.

In conducting the assessment, community needs and resources are examined. The 2024 Community Assessment will:

AlignUPO’sprogramswithidentifiedneedsofDCresidents;

AdvanceUPO’sgoalofassistingDCresidentstobecomeeconomicallysecure;

ImprovecommunicationbetweenthecommunityandUPO;and

AchieveUPO’srequirementofatri-annualassessment

To accomplish these goals, UPO conducted surveys, held focus groups, and interviewed residents living in high poverty areas across the District. Additionally, UPO internally surveyed frontline staff, managers, directors and executive staff. The structed process ensured community and customer input in identifying critical needs. The 2024 Community Needs Assessment includes, data, literature reviews, focus group analysis and interviews to determine the necessary services to assist residents, specifically residents with low incomes. The Community Assessment will be updated annually and repeated every three years.

This assessment meets the requirements for section 676 (b) (11) of the CSBG Act and the goals set forth by Information Memorandum 49 from the Office of Community Services in the United States Department of Health and Human Services. For CSBG, the community assessment offers a focus on local conditions and causes of poverty and enables UPO to analyze the economic opportunities and barriers for all residents of the District of Columbia.

Community Action agencies are private non-profit or public organizations that were established under President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 to combat poverty. Status as a Community Action Agency (CAA) is the result of an explicit designation by the local or state government. The program was created to provide low-income people with the opportunity to access various resources in order to achieve their goals, become economically secure, and support their community by helping other people. Community Action Agencies have provided direct support for more than 34 million people in need per year for several decades.

A CAA involves the low-income population it serves in the planning, administration, and evaluation of its programs. A CAA carries out its mission through a variety of means including:

1. Community-wide assessment of needs and strengths

2. Comprehensive anti-poverty plans and strategies

3. A broad range of direct services

4. Mobilization of financial and non-financial resources

5. Advocacy on behalf of low-income people

6. Partnerships with other community-based organizations to eliminate poverty or address specific needs of the community.

For over 60 years, the United Planning Organization (UPO) has stood at the forefront of the community action movement in the District of Columbia – uniting people with opportunities to help support themselves and each other.

This Community Needs Assessment, conducted by the United Planning Organization (UPO) for 2024, provides an in-depth look at the systemic barriers, socioeconomic trends, and critical needs of low-income residents across Washington, D.C. The study's findings span across governance, safety, education, systemic barriers, housing, environment, and employment sectors. Key findings and recommendations are summarized below.

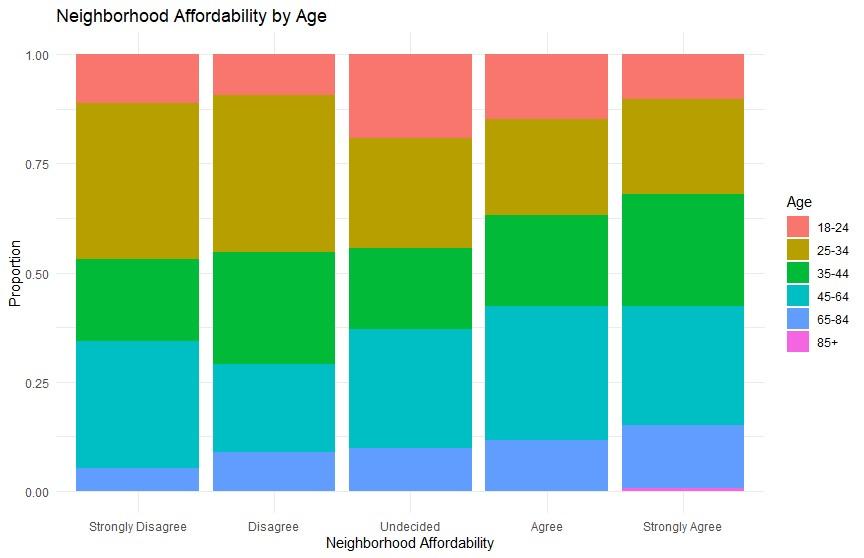

On average, 2024 Community Assessment Survey respondents were predominantly single, Black, female-identifying individuals between the ages of 35-44, living alone. The average respondent had obtained their high school diploma or GED. Respondents, typically, made less than $10,000 a year, paying less than $800 a month in rent, and were unemployed.

The number one barrier preventing individuals from seeking help was a lack of information about where to go for help. Moreover, inadequate transportation was a major hurdle for some residents to overcome.

Concerns about crime and affordable housing throughout the District were reported throughout all focus groups.

The District is still a city divided by systemic inequities, disproportionately impacting Black and Brown residents. For example, white households hold 81 times more wealth than Black and Brown residents.

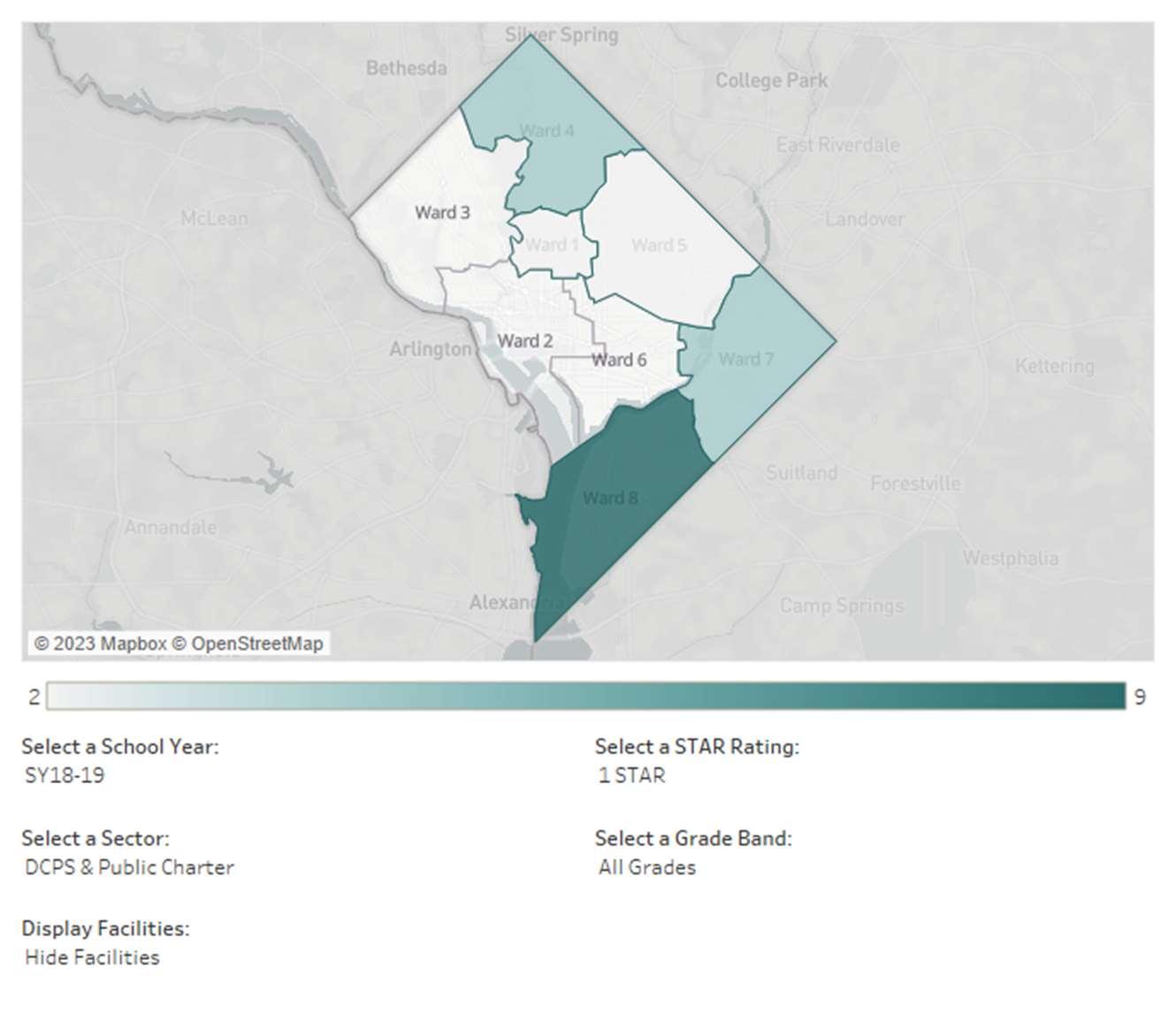

Disparities exist between Wards as well. Ward 3 residents were more likely to report higher levels of income compared to residents in Wards 5, 6, 7 and 8.

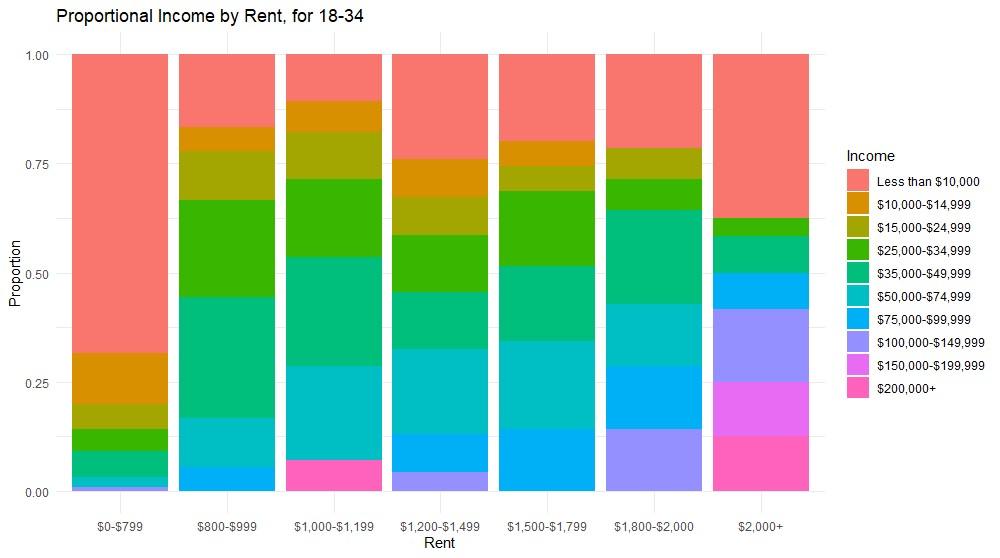

Rent continues to burden many low-income families across the District. As of 2024, minimum wage workers would have to work 79 hours a week to afford a studio apartment to not be considered rent burdened.

Juvenile criminal activity was a considerable issue for many residents, particularly those above the age of 45. Ultimately, the rise of juvenile violence in the District during 2023 can be contributed to the retreat of progressive programs supporting families, such as ERAP or TANF.

Need for Policy Advocacy: Persistent disparities exist, especially for Black and Brown residents, highlighting the need for targeted advocacy and policy reform.

Community Engagement: Residents expressed a desire for more inclusive decision-making processes within governance structures.

Increased Crime Concerns: Community feedback points to significant safety concerns, particularly around juvenile crime, linked to economic instability and reduced social support programs.

Police Interaction: Experiences with law enforcement are mixed, with some communities noting a lack of respect and responsiveness.

Resource Disparities: Schools in lower-income Wards face significant resource shortages, affecting educational quality and outcomes.

Barriers to Access: Limited access to affordable and high-quality early childhood programs impacts many families, particularly those in Wards 7 and 8.

Racial Wealth Gap: The wealth disparity is stark, with white households holding 81 times more wealth than Black and Brown households. This economic

divide affects access to resources and opportunities for many low-income families.

Information and Access Gaps: Many residents lack awareness of available services, and inadequate transportation further limits access to support.

Affordable Housing Crisis: Rent burden is severe, especially for those on minimum wage. A worker earning minimum wage must work 79 hours per week to afford a studio apartment.

Community Impact Zones: Designated areas such as Brentwood and Buzzard Point face chronic housing affordability issues, requiring focused intervention.

Job Placement Needs: Workforce development is critical, with a high demand for training programs in in-demand fields.

Barriers to Job Retention: High levels of underemployment persist, partially due to inadequate childcare and transportation challenges.

Governance: Strengthen community representation in local governance and promote transparency to address community concerns effectively.

Safety: Expand community-based programs to reduce juvenile crime and improve relationships between law enforcement and communities.

Education: Increase funding and resources to schools in underserved neighborhoods, particularly targeting early childhood education initiatives.

Address Systemic Barriers: Develop outreach programs to improve residents' awareness of available services and create more accessible transportation options. To alleviate the systemic and personal issues facing residents, UPO, its partners, and government entities should invest considerable energy in

grassroots campaigning and advocating for policies that benefit low-income residents, while providing wraparound services to those who need them.

Housing: Expand affordable housing initiatives and advocate for rent control measures in high-demand areas.

Employment: Invest in job training programs, particularly those that address the digital divide and provide support services such as childcare.

The United Planning Organization (UPO) was founded as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in 1962 and became the designated community action agency (CAA) for the District of Columbia in 1965. As one of our nation’s more than 1,000 CAAs, UPO is dedicated to helping Washington, DC residents with low incomes along their journeys to becoming economically secure. For nearly 60 years, UPO has been at the forefront of the war on poverty. As the catalyst for economic security and growth for all Washington, DC residents, UPO has laid the groundwork for innovative social service programs such as Early Head Start, workforce development training, and youth development, amongst many other programs.

Every day, UPO works tirelessly to embody its vision, mission, and promise for the people of the District of Columbia.

VISION: UPO’s Washington, DC: A city of thriving communities and self-sufficient residents

MISSION: Uniting People with Opportunities

UPO’s PROMISE: Community Action changes people’s lives, embodies the spirit of hope, improves communities, and makes America a better place to live. We care about the entire community, and we are dedicated to helping people help themselves and each other.

Ruthven Phillip, Esq (Chair)

Salim K. Adofo

Lafayette Barnes (Vice Chair) Shakira Hemphill

Michael Austin, Esq (Secretary) Josiane Yepmo

Barbara Bovbjerg (Treasurer) Reginald Black

Executive Team

Andrea Thomas, President and Chief Executive Officer

Nkosi Bradley, Esq

Christian Clanksy

Tonya Crawford

Loren Cox, Ph.D.

Rhonda N. Hamilton

Jennifer Park, Ph.D.

Christopher Sennett

Dorjan Short

Aron Szapiro

Robert Thorne

Dr. Christine M. Warnke

Daniel Ofori-Addo, Executive Vice President and Chief Impact Officer

Dianna Guinyard, Vice President of Operations and Chief Operating Officer

Rosalind Pinkey, Vice President of Human Resources

Theresa Lewis, Vice President of Legal Affairs and General Counsel

Andrew Harris, Vice President Finance & Chief Financial Officer

Hyvron Jean, Vice President, Technology & Information Systems

Syrita Robinson, Vice President Office Early Learning

Kevin Bryant, Director of Business Development and Asset Management

Disclaimer

The United Planning Organization (UPO) believes reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this document. To ensure continued accuracy, the documents may be changed or updated without notice. Information contained in this document is intended for discussion and educational purposes only and is provided as is without warranty of any kind. Presentation or reference to information provided is at the user’s own risk.

UPO and its contributors hereby disclaim all warranties and conditions regarding this information and all related graphics. Photographic images contained herein are strictly for educational purposes and not for profit. Organizations and individuals contributing to this document may have been mistakenly omitted. The listing of organizations or references does not imply any endorsement or partnership with UPO.

Tables and figures were prepared using U.S. census data, other secondary sources, and UPO primary sources to make projections and draw inferences. These tables and figures are provided for use as the official numbers on population and selected demographics. Other figures tracked by credible independent sources are provided in the narrative and may also be accurate, though not official. Any opinions and views-actual or perceived- expressed from those sources do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the United Planning Organization.

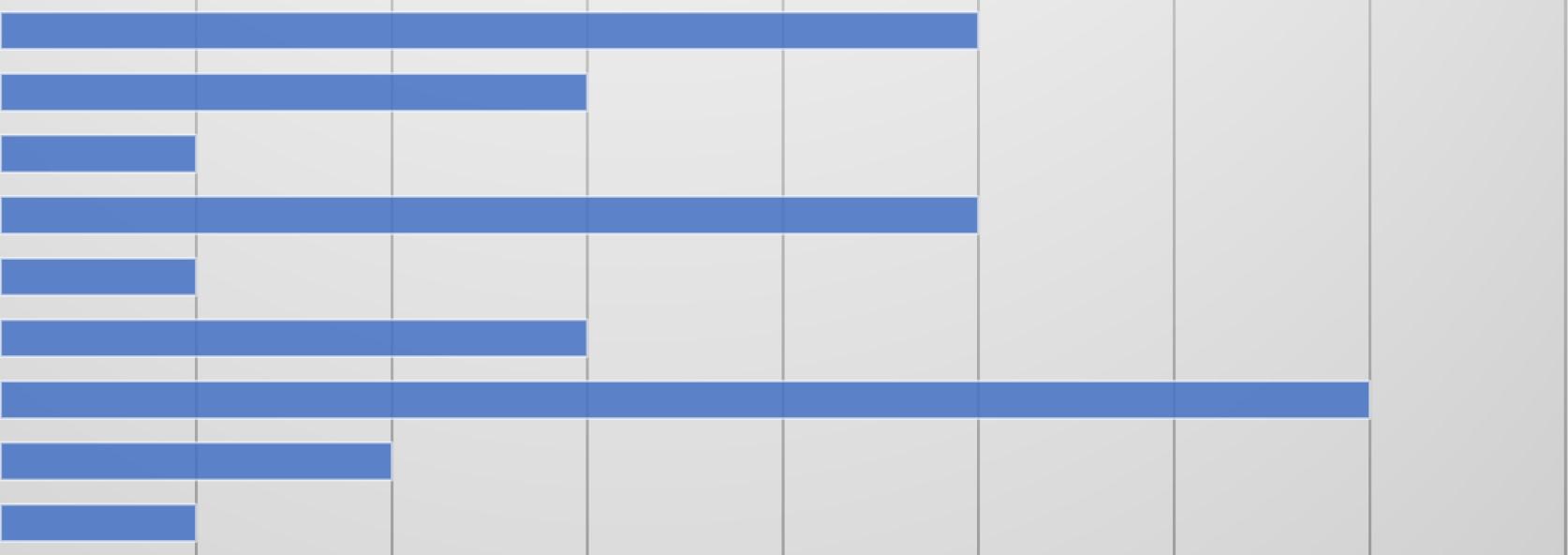

For the 2024 Community Needs Assessment, UPO collected demographic information from a statistically representative sample size in the District. This was accomplished by using statistically proven survey collection methods as well as qualitative data collection efforts from several focus groups and targeted interviews across the District. Through the methods listed above, UPO collected information that best reflects a representative sample of residents and stakeholders in the District including residents with low-incomes.

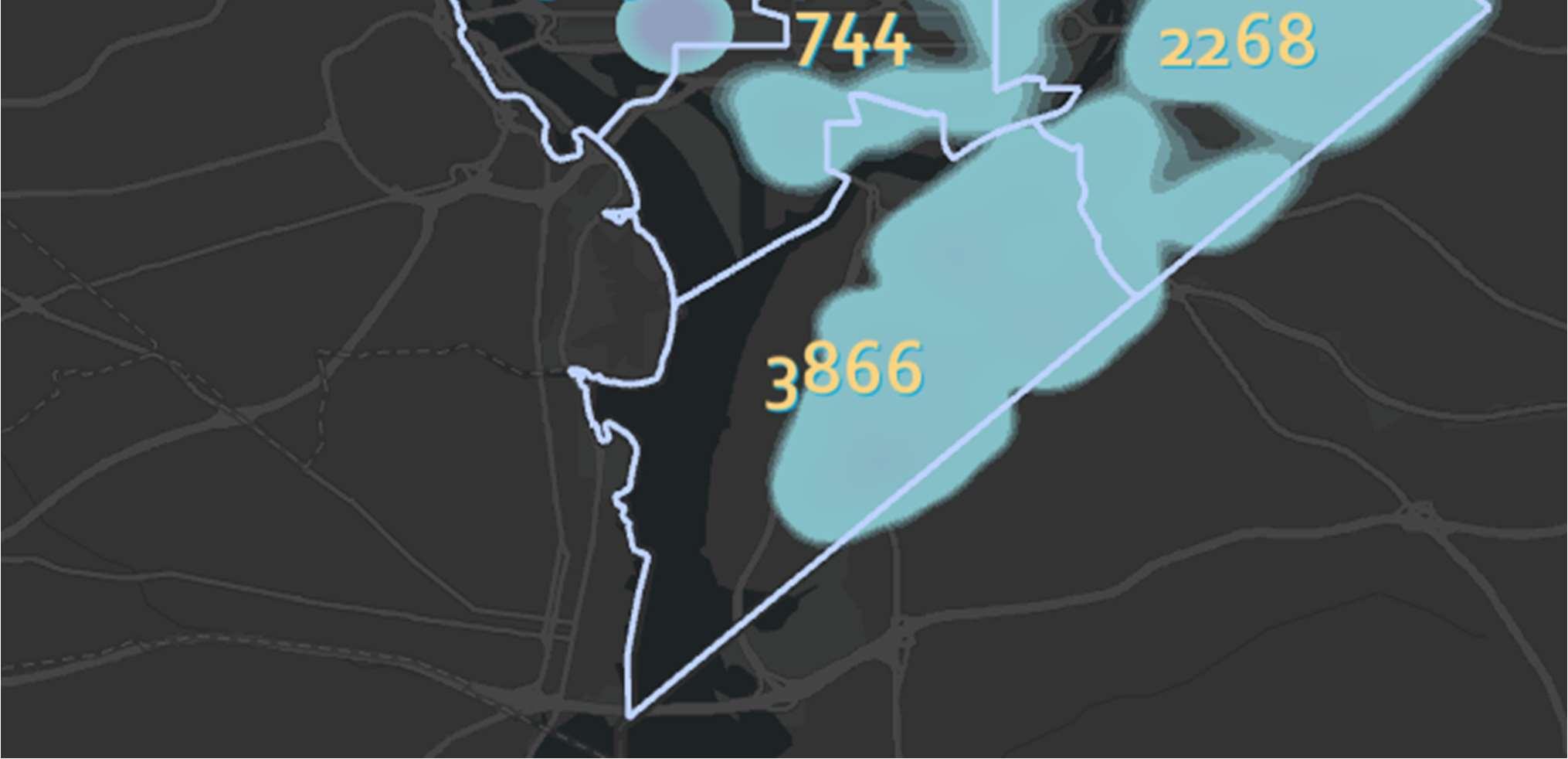

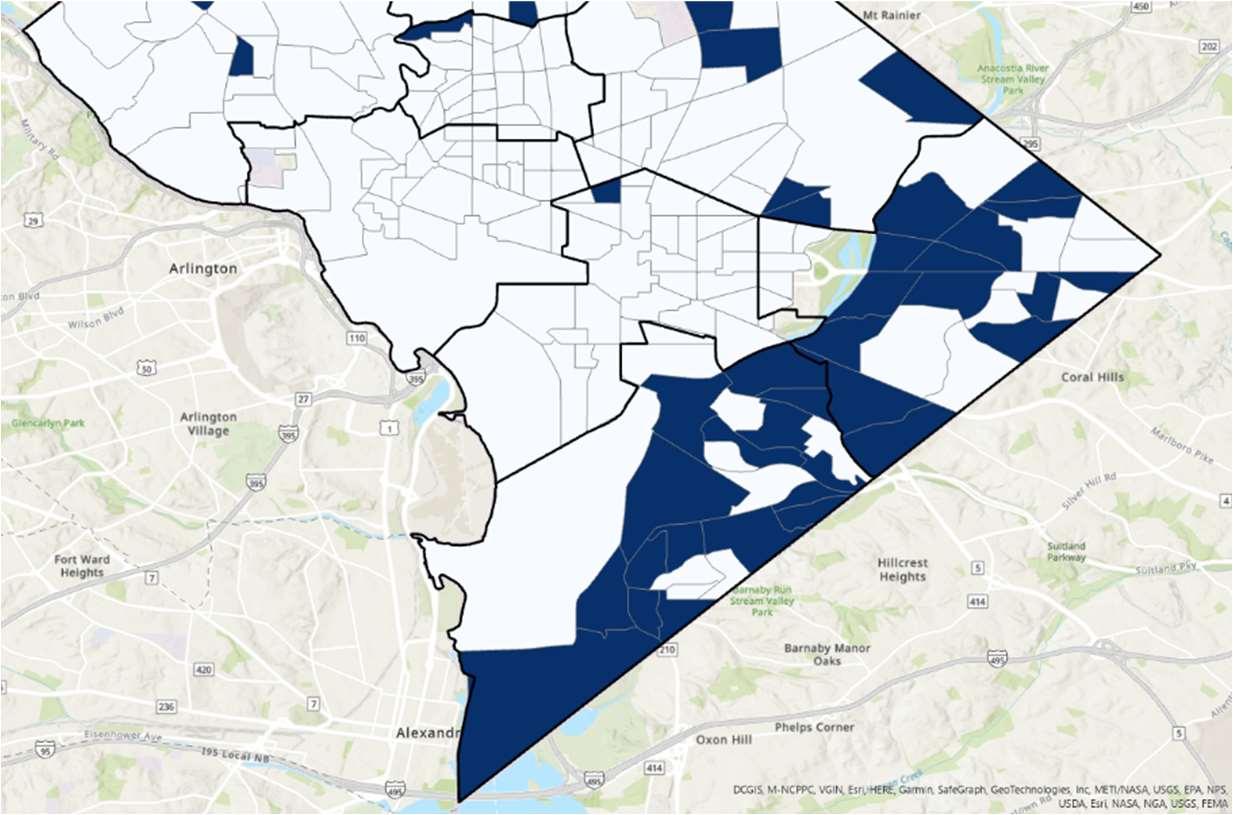

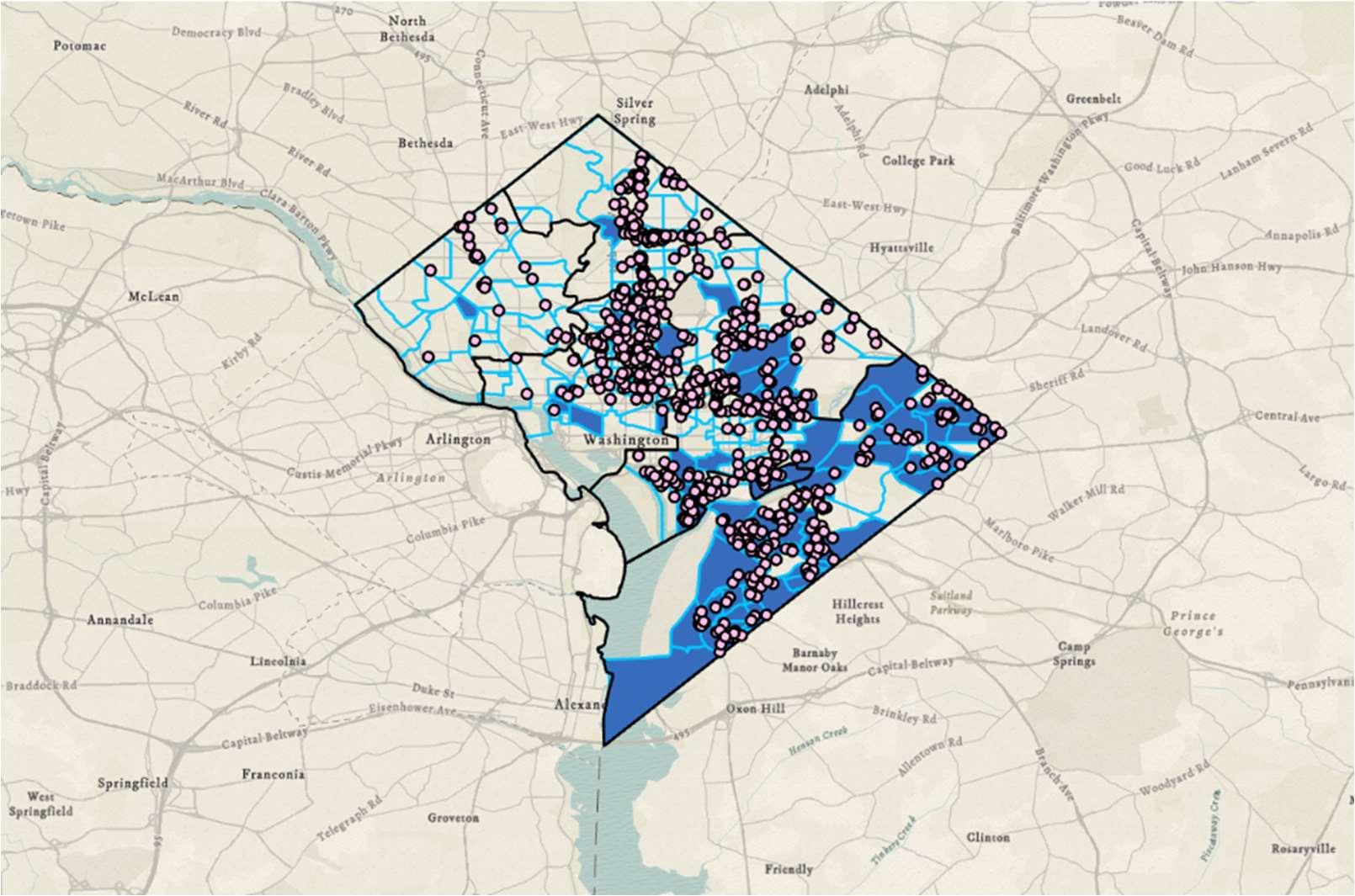

To collect a statistically representative sample, UPO utilized cluster sampling and randomization in distributing the Community Assessment survey. First, UPO identified lowincome neighborhoods in the District through both census data and UPO’s own experience within communities. Census tracts that had a poverty rate of 20% or higher for over ten years was targeted to receive the survey. Once the census tracts were identified, UPO used the publicly available Master Address Repository (MAR) to identify households and apartments located within the selected census tracts. Upon confirmation with the Office of Zoning that develops the MAR that the data was up-to-date, UPO began the data cleaning process, removing unoccupied housing units or units currently being developed. Once the data set had been cleaned, UPO randomly selected 2,500 single family or multifamily homes and 2,500 apartments within the selected communities. Apartment information is also publicly available online through the MAR, which lists the unit numbers within the apartments. Five thousand housing units were selected as part of UPO’s mail survey campaign, earmarking a 20% response rate, with an attached $10 incentive for completing the survey. Data was collected through the Question Pro software and was cleaned for accuracy. After the closing of the survey, the response rate was 7%.

UPO recognized that it was also important to focus collecting information from its designated Community Impact Zones (CIZs). The neighborhoods of Brentwood, Marshall Heights,

Washington Highlands and Buzzard Point have been designated by UPO as CIZ zones due to their high rates of crime, poverty and unemployment. By focusing survey efforts on CIZs, UPO collected information about residents that UPO works with directly, while simultaneously identifying issues with poverty city wide through the mail-in survey.

In tandem, residents who typically do not request UPO services (Wards 1, 2, 3 and 4) were subject to “boots on the ground” survey distribution. The process of collecting surveys through face-to-face interaction ensured that residents living in wards with low poverty rates were accounted for in the city-wide assessment.

In addition to collecting quantitative information about DC residents, UPO, in line with CSGB eligibility, held focus groups in all eight wards located in the District. UPO held focus groups for residents in the aforementioned CIZs, and more broadly, focus groups for Wards 1, 2, 3 and 4, where UPO does not have significant numbers of customers. In the ward groups, residents were asked about the political, social and economic developments ongoing in the District. The questions residents were asked can be found in the appendix of this report. Furthermore, other focus groups were conducted in line with CSGB eligibility, including religious leaders, educators, small business, individuals with disabilities, elderly, and non-profits.

In total, 18 focus groups were conducted between February 2024 and August 2024 in order to obtain residents’ perspectives about the District and to articulate their needs. One focus group was conducted for each Ward, for a total of eight. Additionally, focus groups were conducted with seniors, unhoused individuals, parents of children with behavioral issues, youth practitioners, faith-based leaders, educators, and small business owners. To understand the work-related needs of staff, managers, and executives, UPO held three internal focus groups.

Structured interviews were conducted to supplement the shortage of participating individuals in Wards 3, Wards 4, and for small business owners and faith-based leaders.

Focus groups were analyzed using the nVIVO qualitative analysis. Some focus group analyses may not include nVIVO data visualization.

A total of 1,012 residents responded to the survey. Residents filled out both the “boots on the ground” survey, email survey, and mail-in survey. To complete the boots on the ground survey, UPO worked with external organizations and internal staff persons to distribute the survey to customers and other members of the community. Some of the physical surveys were missing data points. These surveys were still completed in the final analysis.

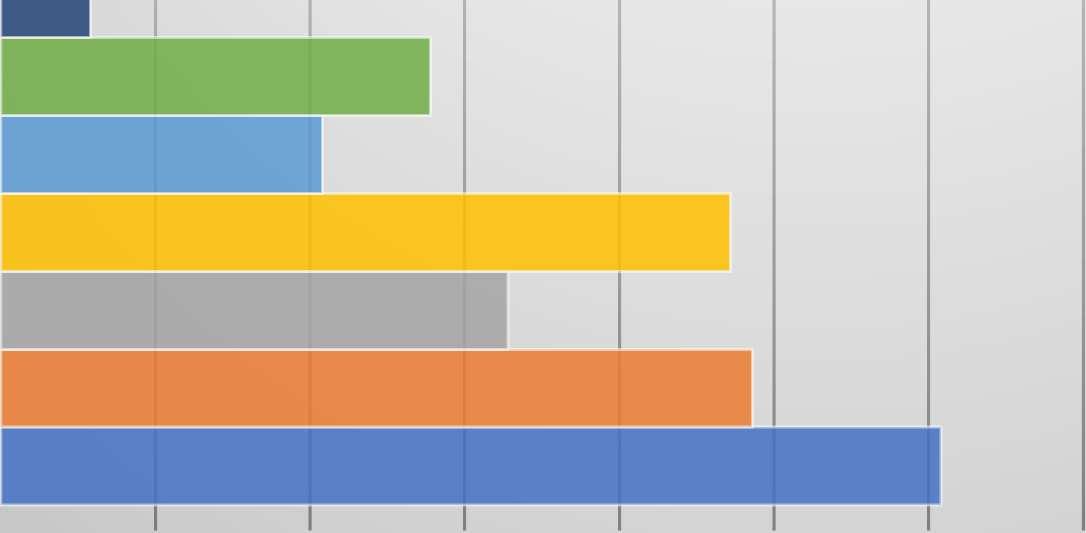

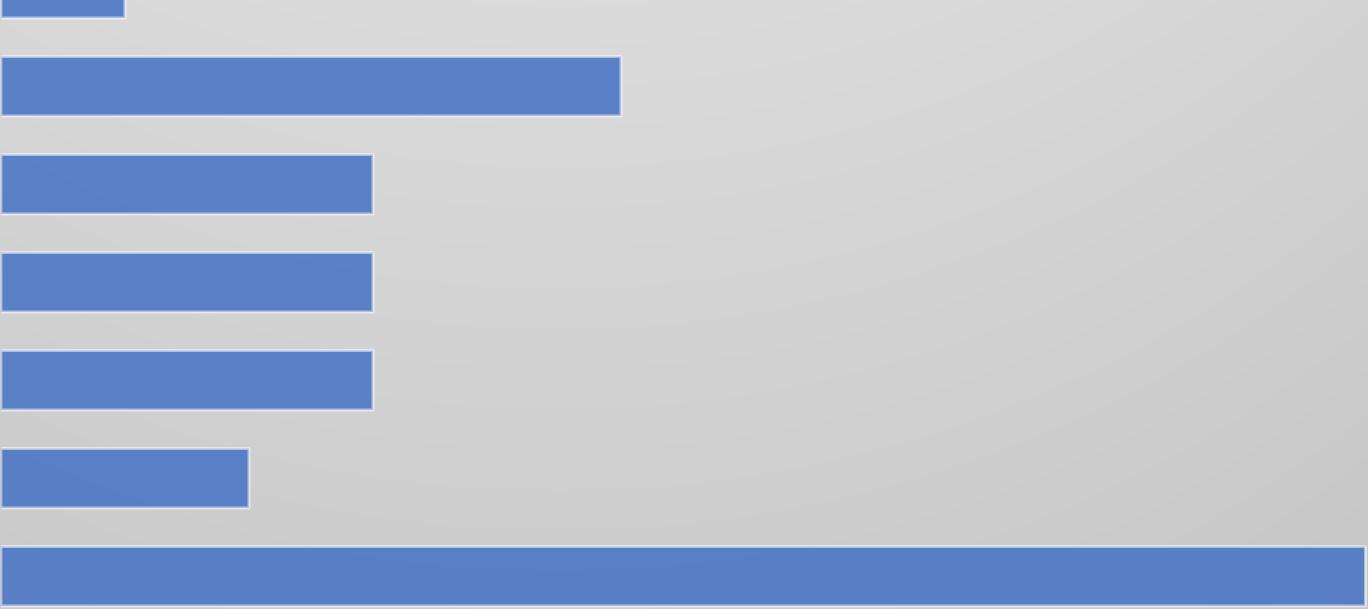

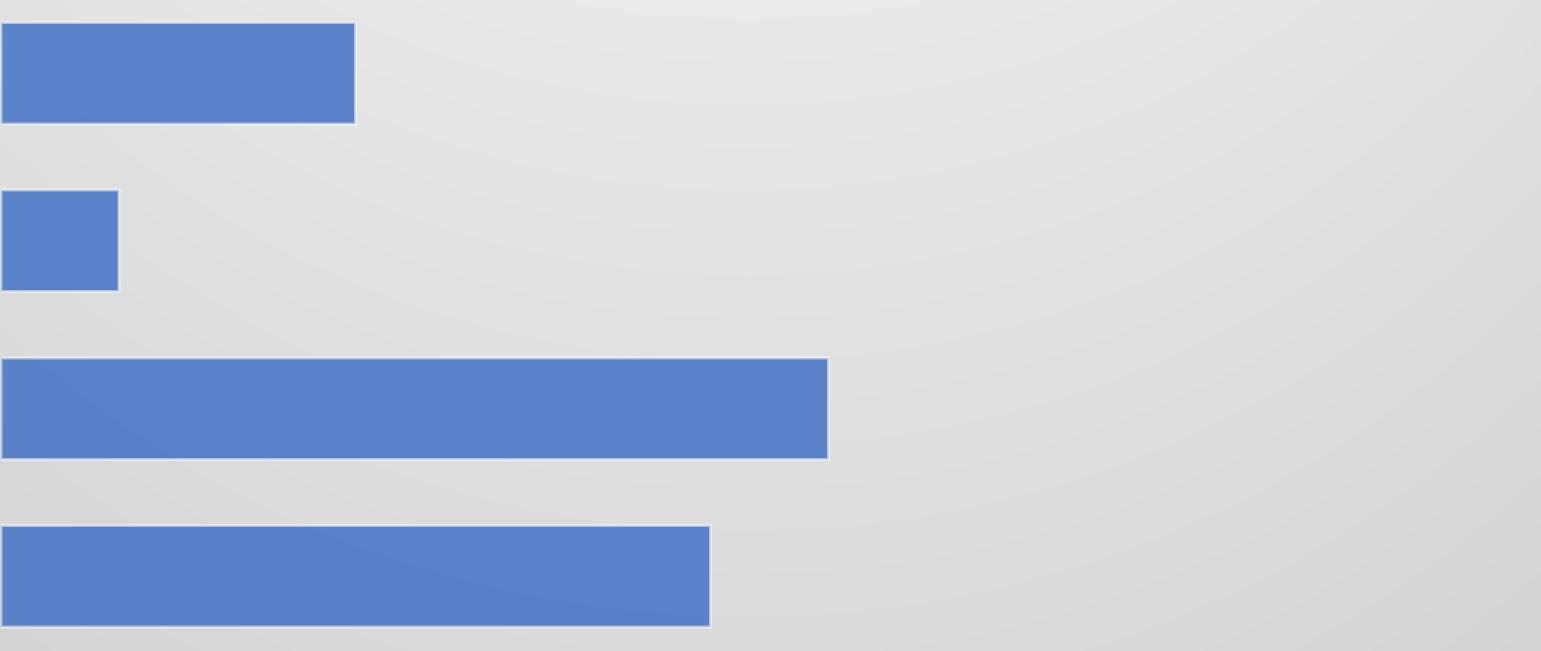

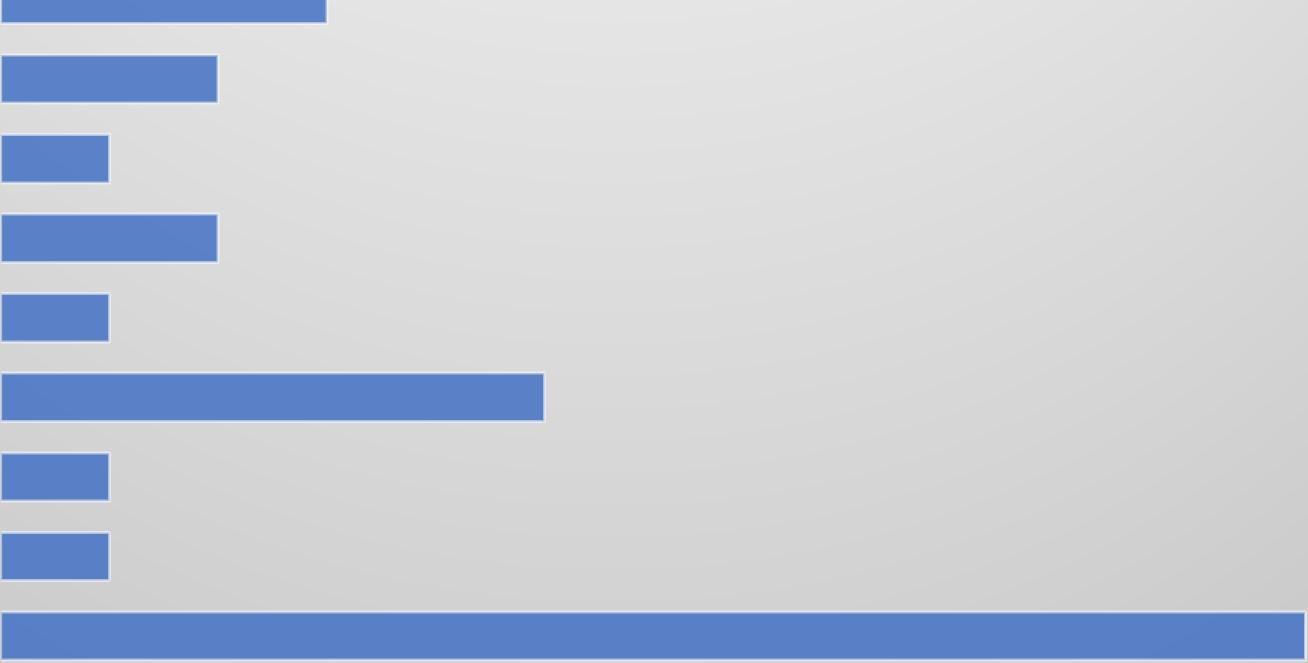

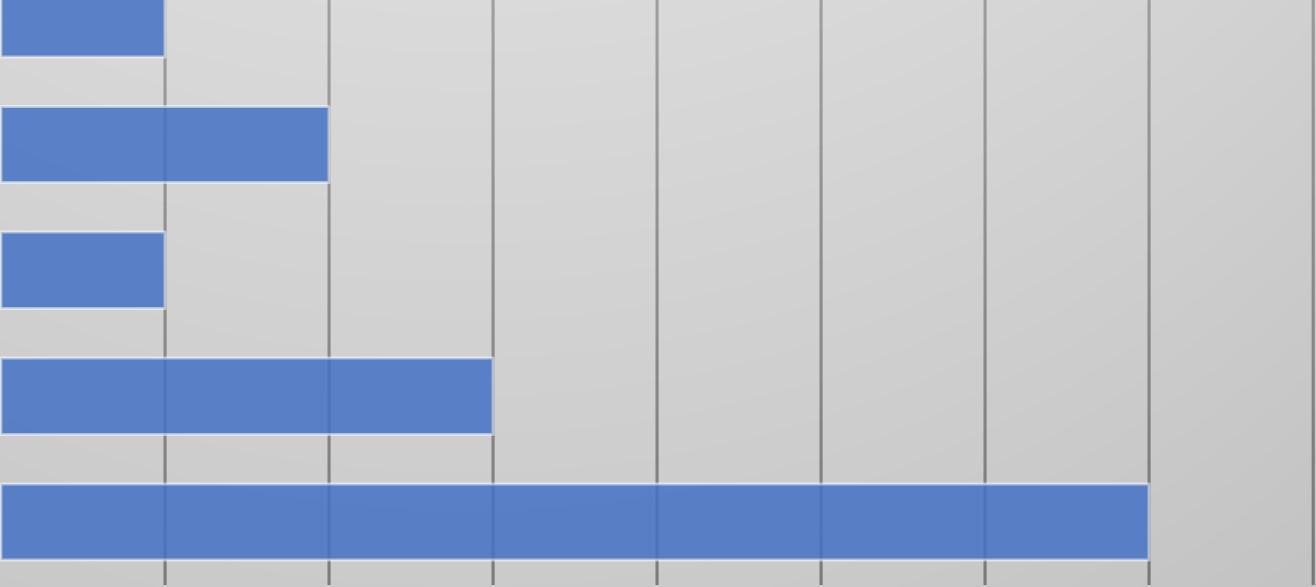

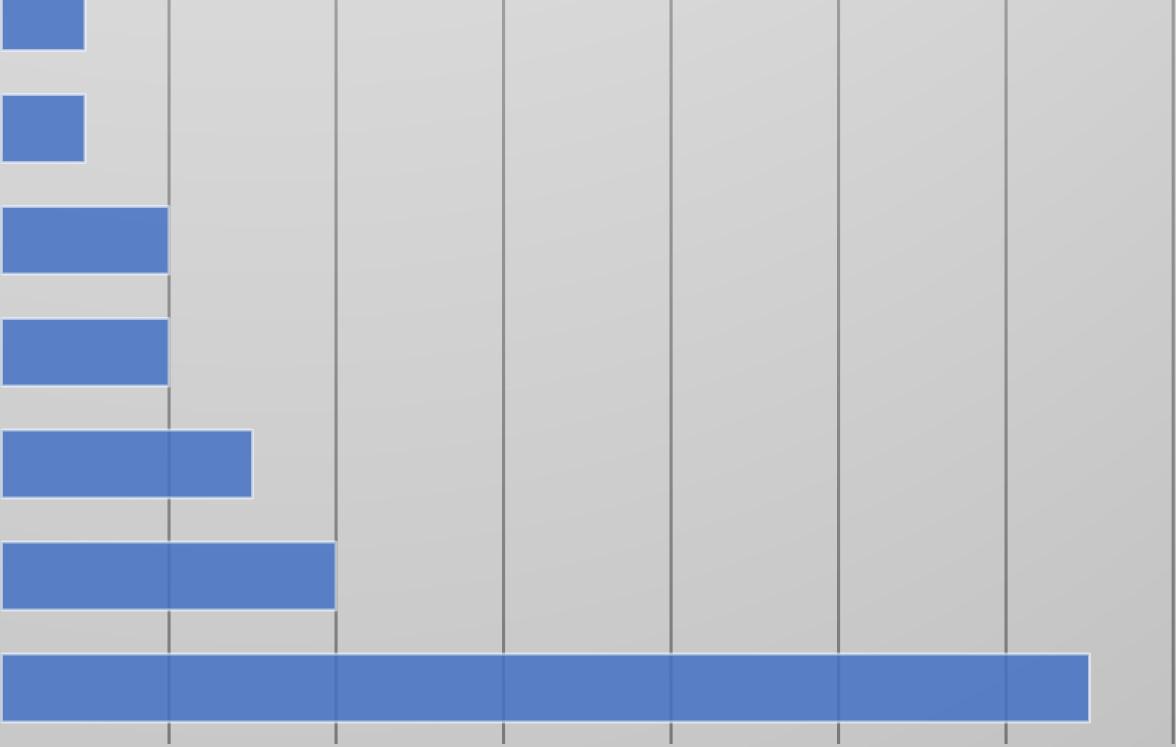

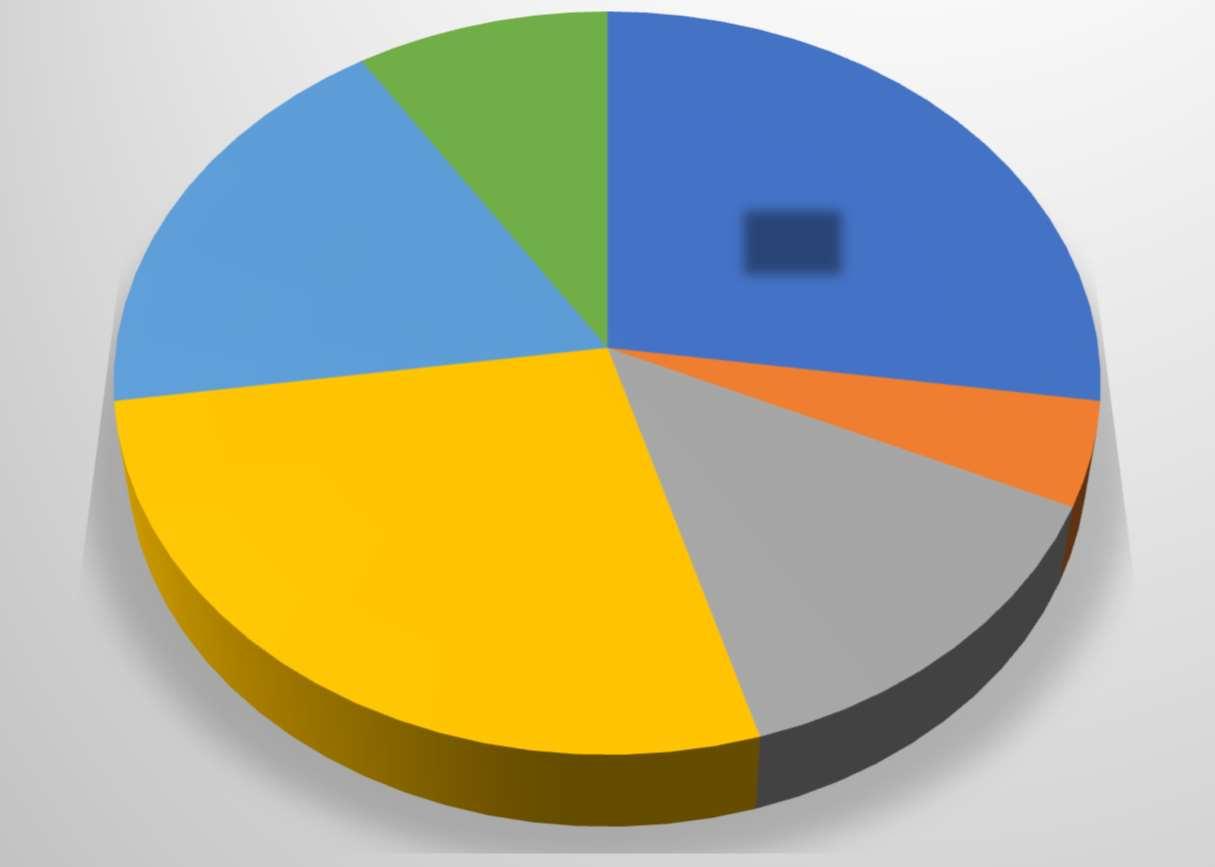

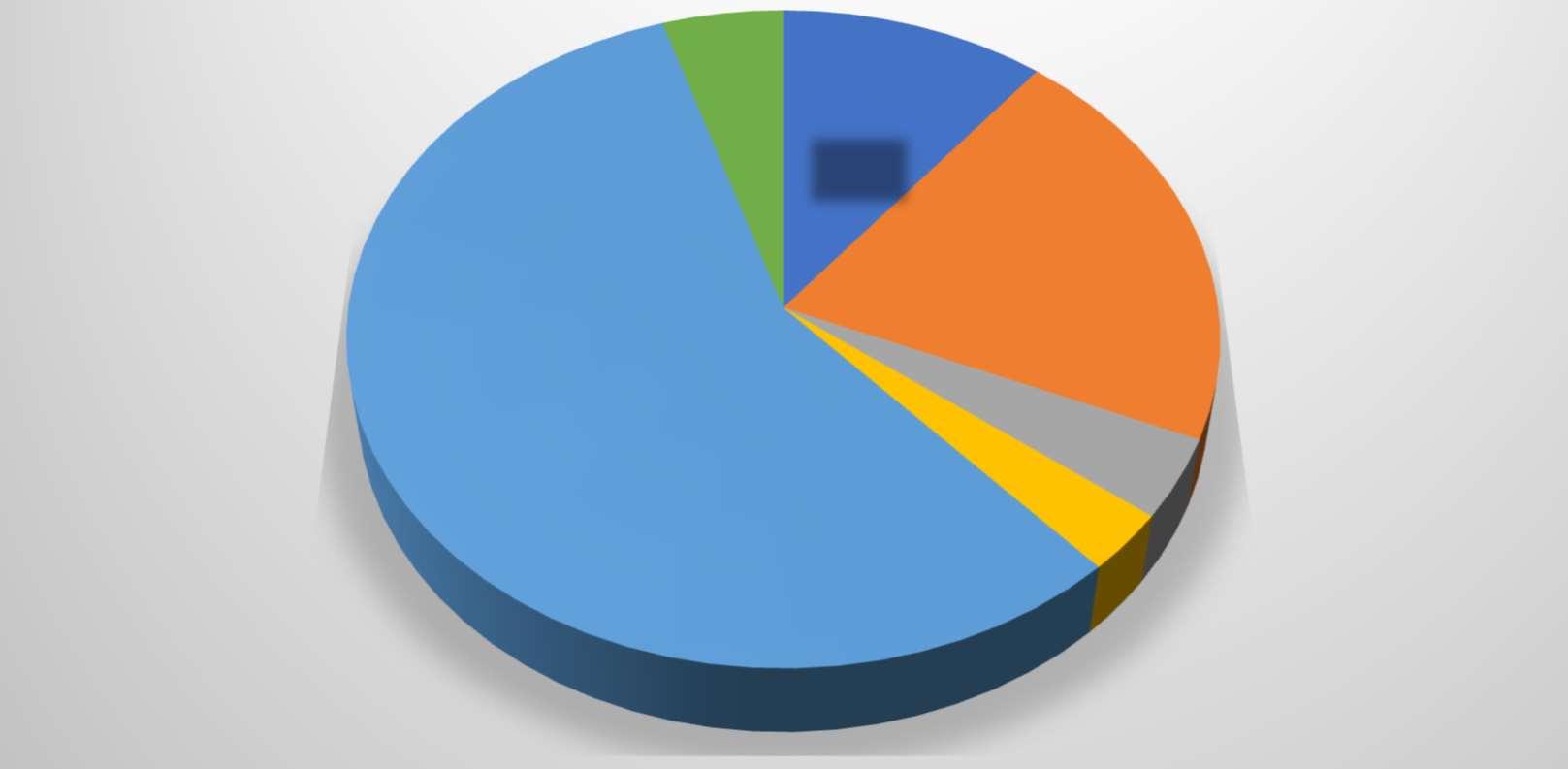

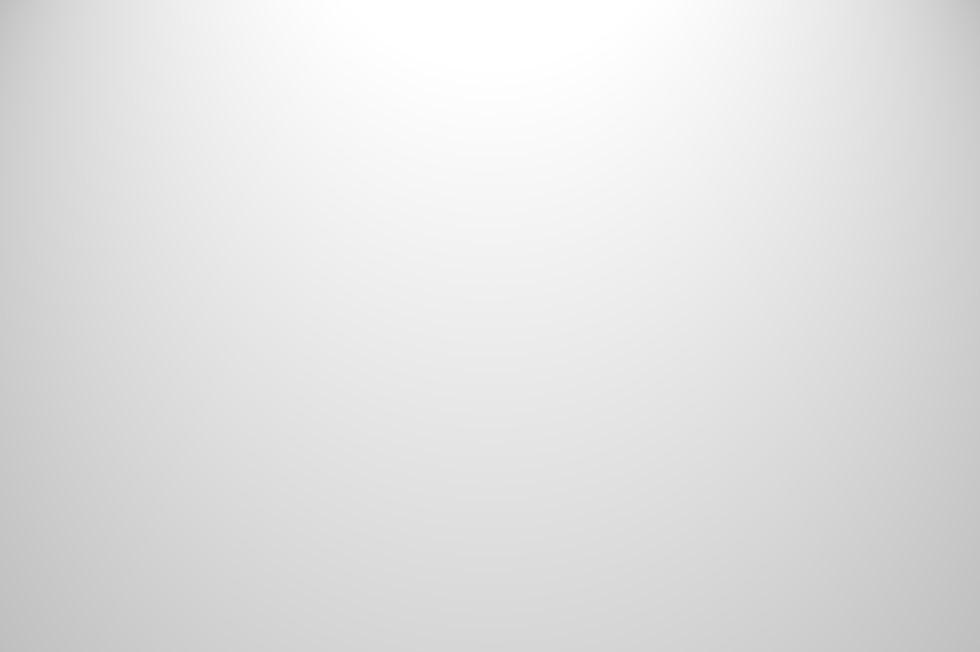

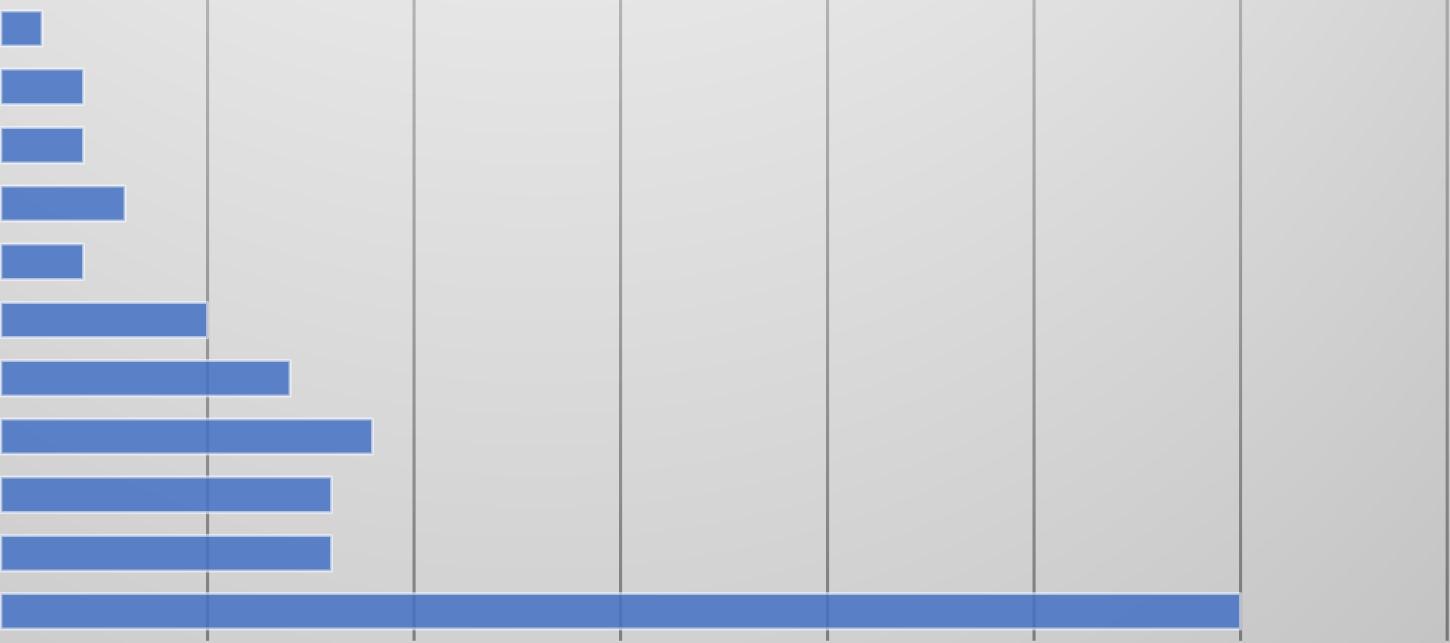

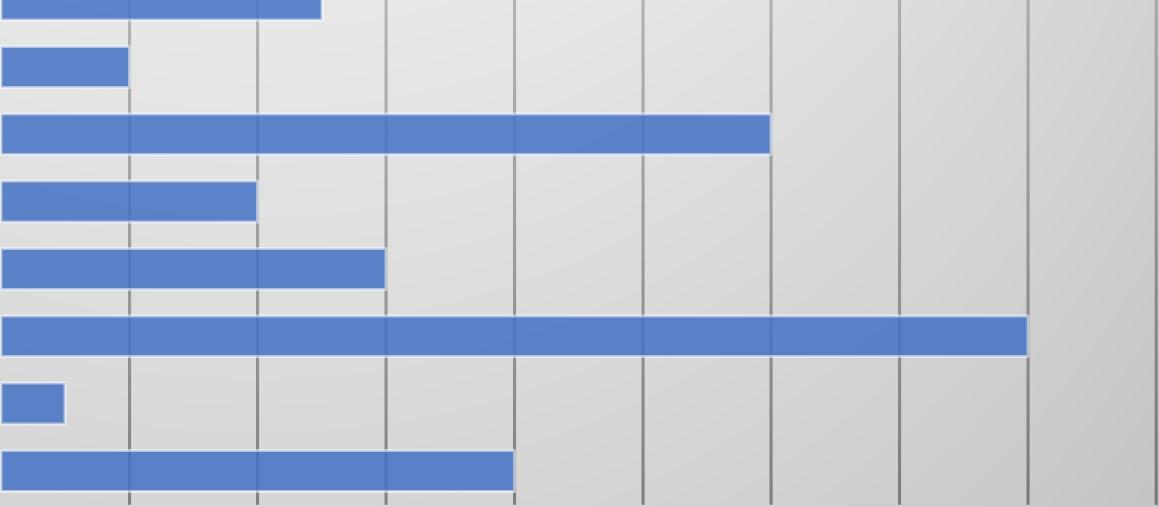

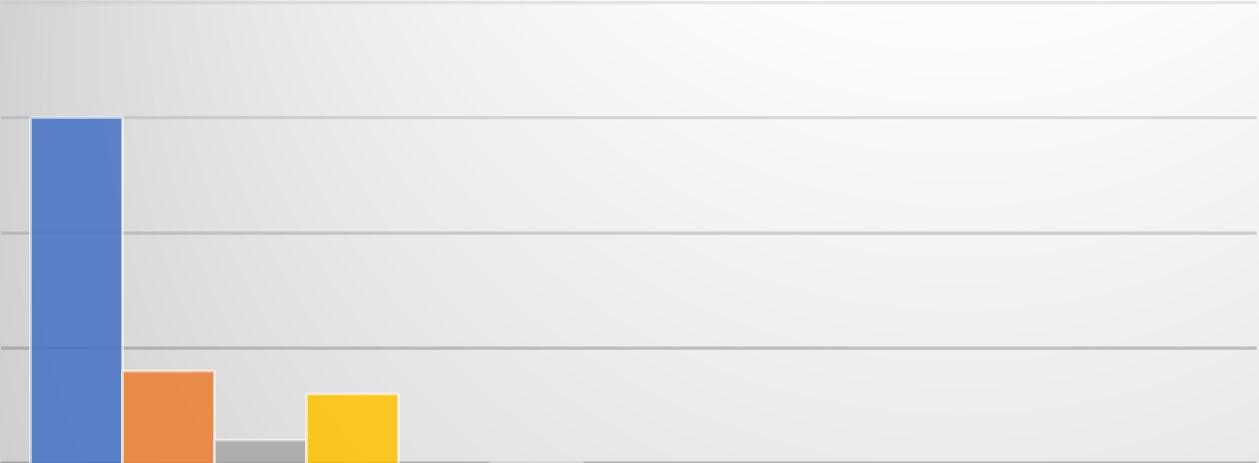

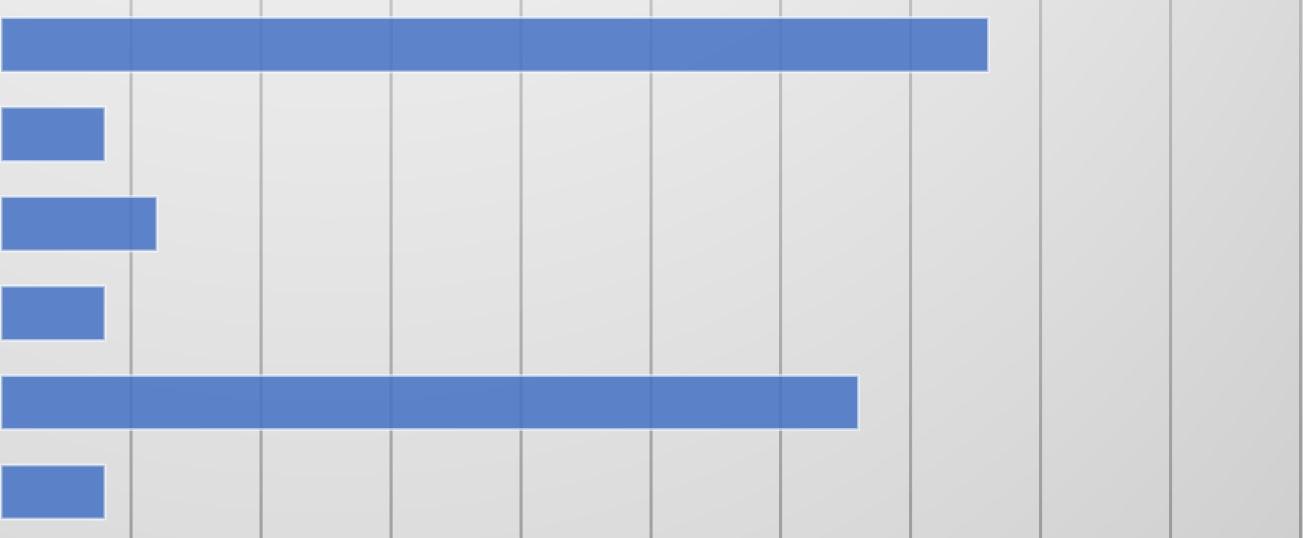

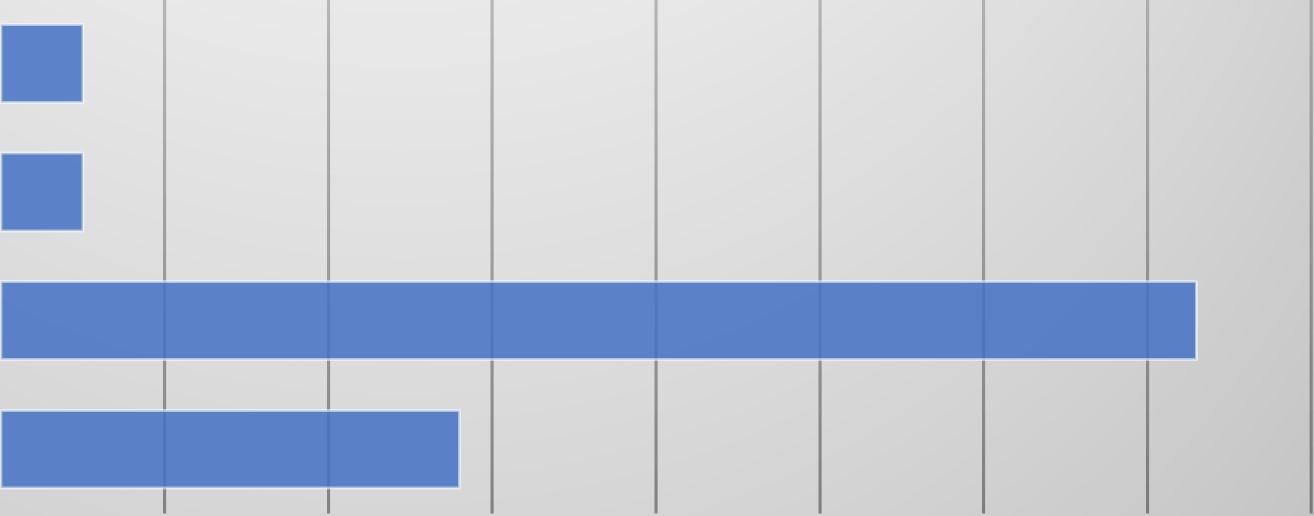

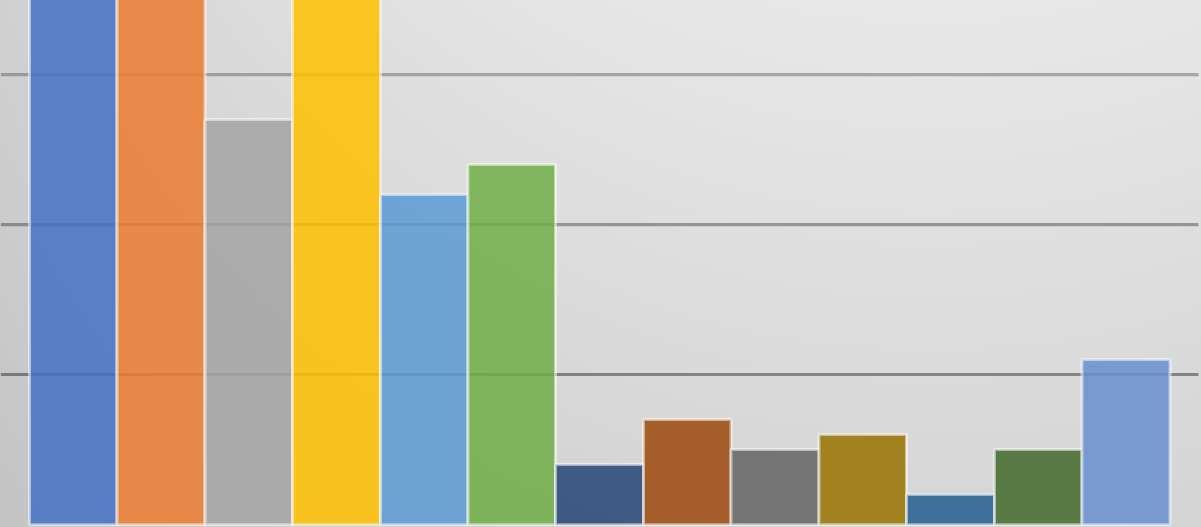

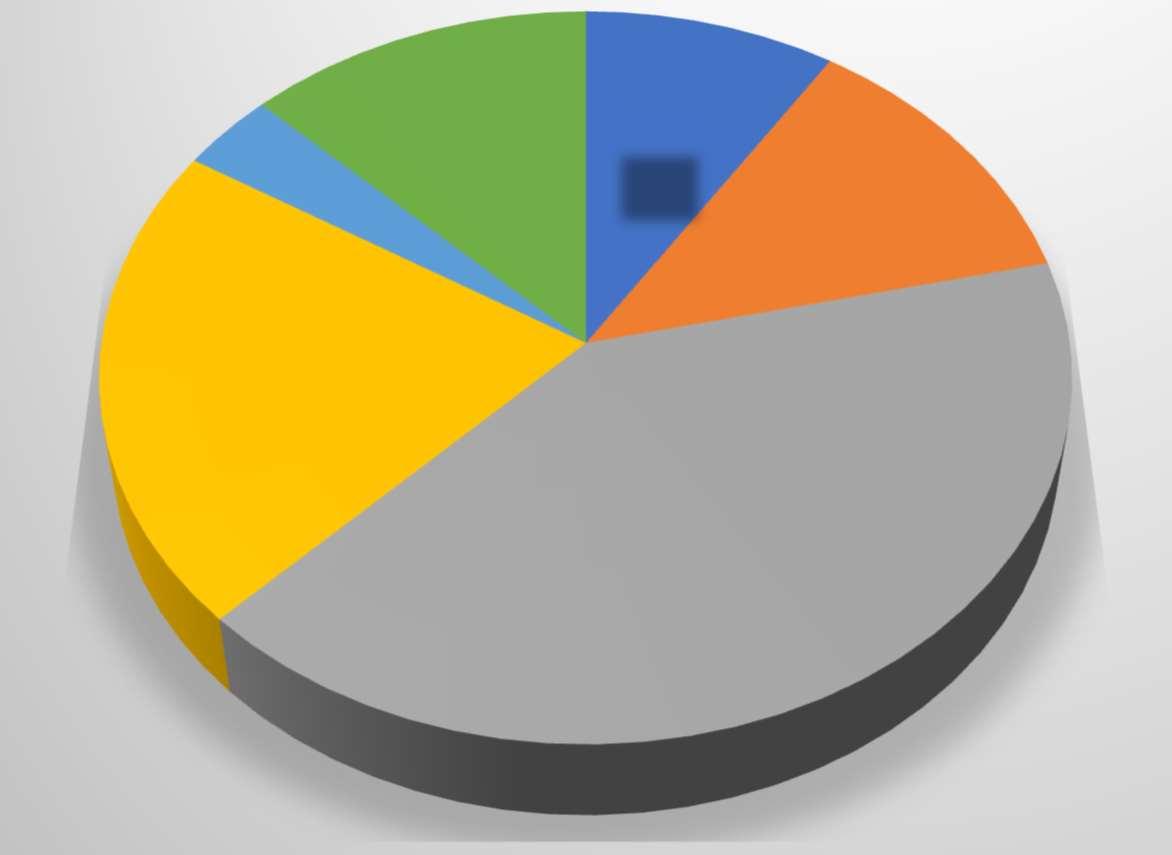

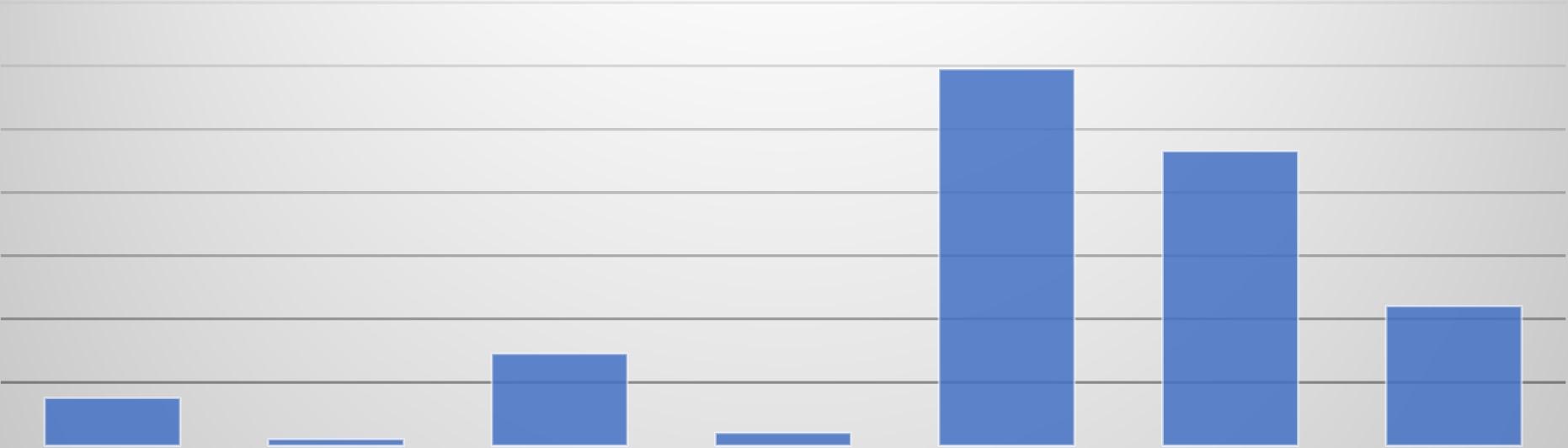

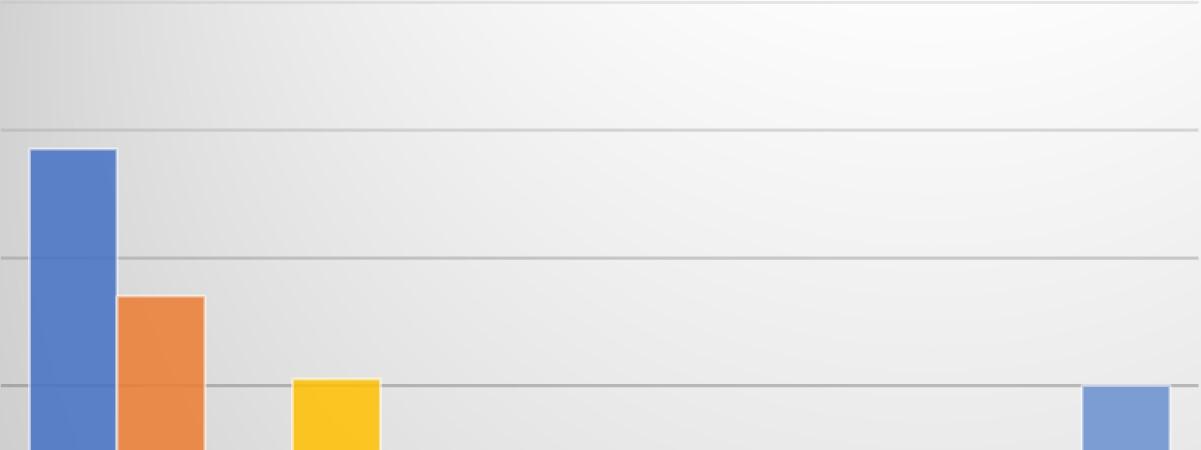

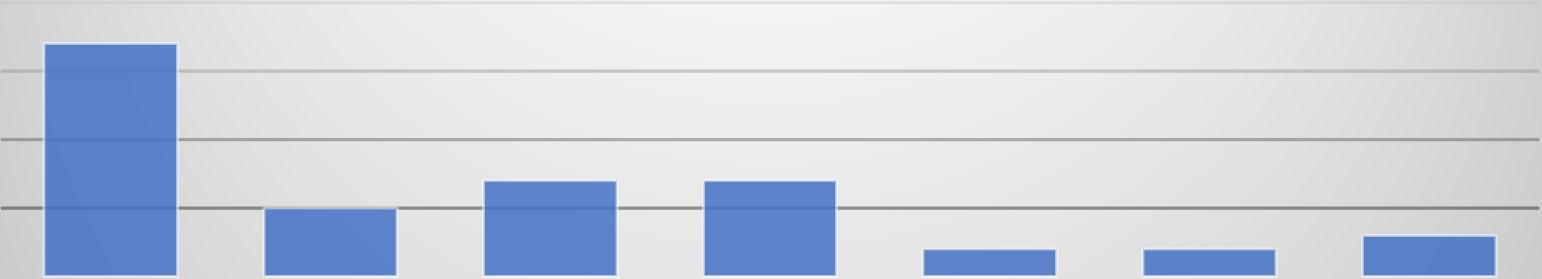

Ward 1 66

Ward 2 47

Ward 3 23

Ward 4 51

Ward 5 103

Ward 6 92

Ward 7 248

Ward 8 311

Didn’t know/Unhoused 71

Because the mail-in surveys were sent city-wide but did not directly target individuals who have received UPO services before, the customer service portion of the survey received 322 responses.

UPO has very little presence in Wards 1, 2, 3 and 4. Moreover, these areas of the city are known for their wealth. An individual living in Ward 3 has a significantly higher chance than making more money than an individual living in Wards 5, 6, 7, and 8. Therefore, there are fewer communities in Wards 1, 2, 3, and 4 experiencing poverty or generational poverty.

The mail-in survey reflects a representative sample of the total population in one area. Even though the survey was sent in areas that had a 20% poverty level or higher, this did not mean that all individuals living in the area were experiencing poverty. As a result, the survey may account for higher levels of socio-economic diversity.

In developing the 2024 Community Assessment, UPO sought to produce a community focused, comprehensive document from which readers can extract free-standing sections.

The comprehensive report begins with the current Overview section, which introduces UPO, its staff, board and programs. Additionally, this section highlights changes since the last needs assessments and services provided to residents by UPO.

The Review of Literature details studies and city-wide analysis by third parties that focus on developments ongoing within the District. The topics range from city-wide issues to niche local issues.

A special section on Juvenile Crime seeks to explain the increase in juvenile crime, the political developments that have occurred around the increase in juvenile crime, and potential solutions to the issue.

A special section on Affordable Housing examines the need for greater affordable housing in the District, along with the reasons for why the District is experiencing a housing crisis in the first place.

A special section on Economic Mobility detailing the likelihood of an individual raised in DC chances to escape poverty if they were born into poverty themselves.

A special section on Digital Literacy and the Digital Divide highlights the struggles for some residents, particularly in poorer parts of the District, to obtain high speed internet broadband.

A special section on The Benefits Cliff focuses on the incentives for individuals who are on public support programs to avoid programs and initiatives that help them achieve economic mobility.

The survey results analyzing the results from the UPO Community Assessment Survey Results contains quantitative data collected from the survey from predominately low-income residents but does include responses from middle-income and high-income earners across the District. The section also details the results from UPO Focus Groups with varying individuals across the District.

Recommendations for Addressing City-Wide Needs covers educational, civic, social, physical and economic needs of residents for organizations such as UPO, government agencies and service providers to improve the quality of life for all residents in the District.

Agency Level Needs identifies key organizational needs for UPO.

The data collected from the Community Assessment Survey is organized on a ward-by-ward basis, detailing the specific needs of residents with each ward. Stakeholders may examine the data analysis and use it to formulate decisions that affect residents within a specific ward. This section will also detail recommendations for a specific ward.

Lastly, the data from the Community Assessment Survey is filtered by a resident’s location in a Community Impact Zone (CIZ), emphasizing the needs of residents in areas experiencing generational poverty.

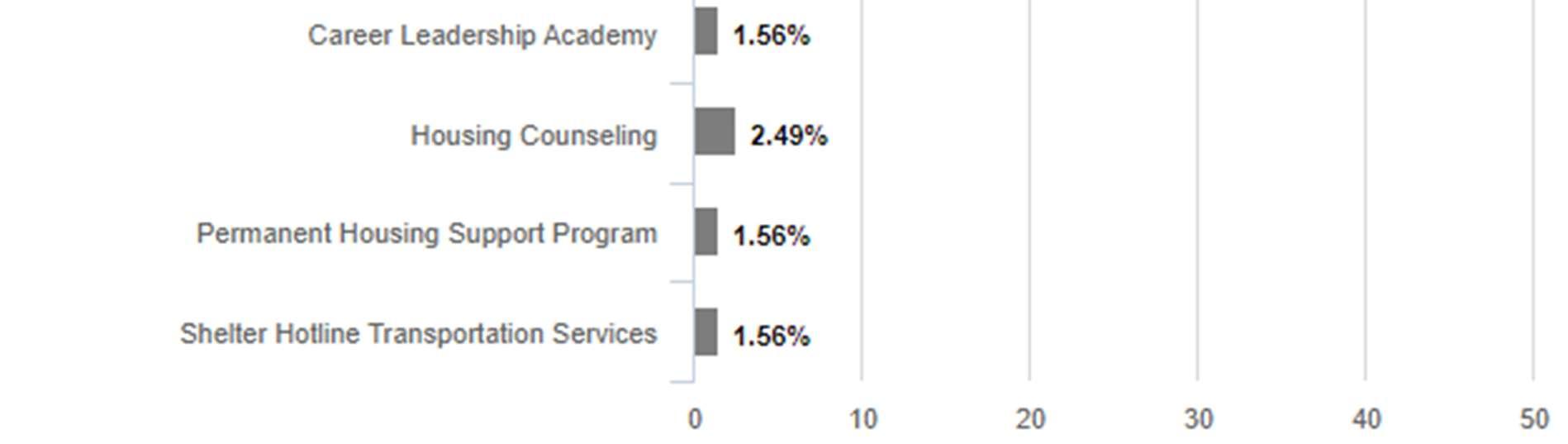

Programs

The programs and services that UPO offers are listed below. In recent years, UPO has sought to increase the number of programs offered to residents in DC and beyond.

Advocacy

Affordable Housing Development

Child and Adult Care Food Program

Comprehensive Treatment Center (CTC)

CREATE After School Program

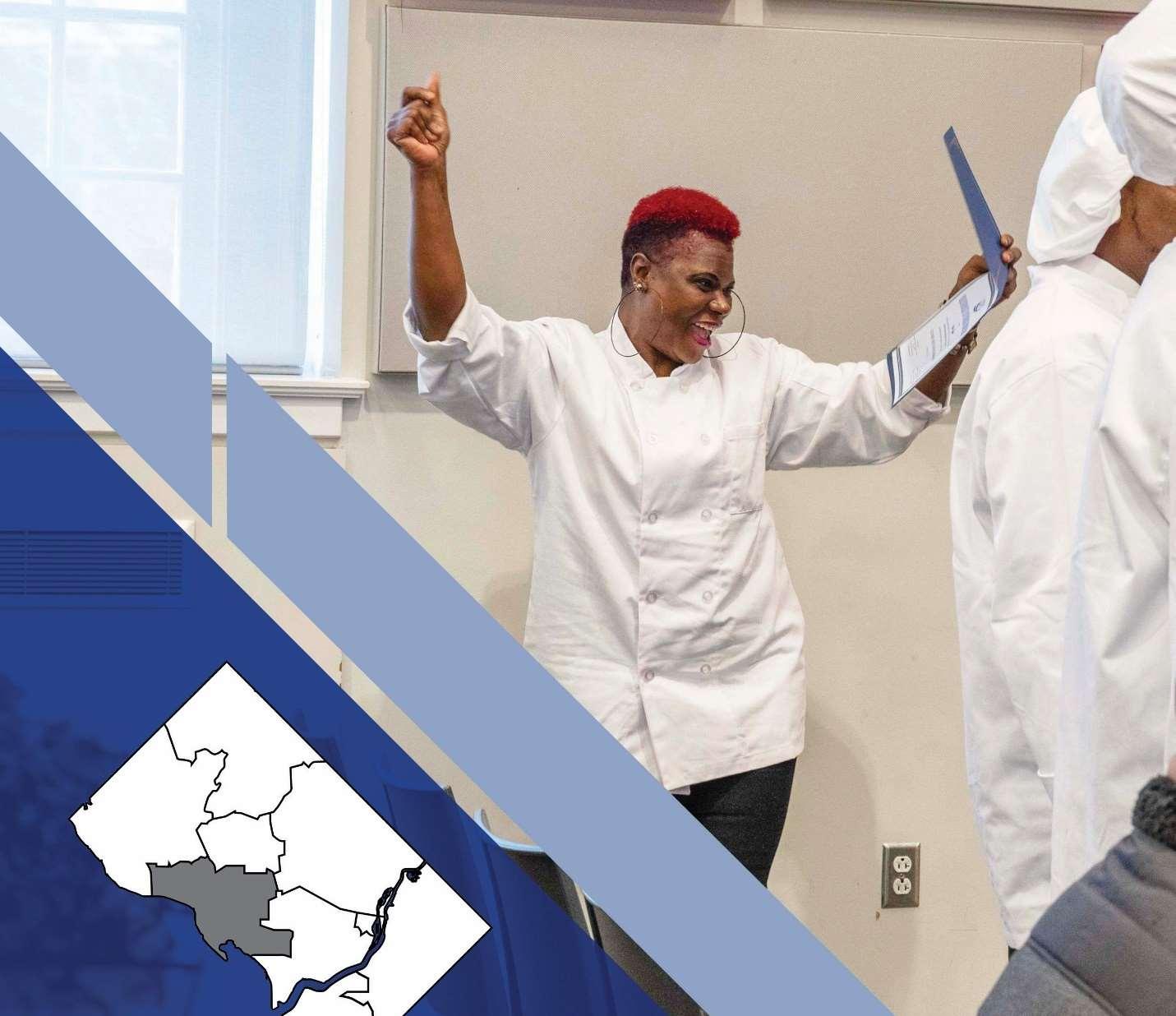

Culinary Arts Training

Early Head Start and Home Visiting Program

Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) Service Centers

Emergency Rental Assistance Program

Employment Placement Services

Foster Grandparent Program

Household Food Distribution

Housing Counseling

Joseph A. Beavers Scholarship Fund

Mental Health Counseling

Permanent Supportive Housing (PHS) Services

Providing Opportunities with Education Readiness (POWER)

Quality Improvement Network (QIN) Technical Assistance to Childcare Providers

Shelter Hotline

Shelter-Plus CARE (SPC)

Strengths-Based Family Worker Training

Summer Youth After-School Program

Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) Program

Volunteer Services

Workforce Institute: Training in 10 Credentialed, In-Demand Job Sectors

Youth Services

UPO serves all customers seeking assistance with a variety of appropriate and available services ranging from long-term case management to one-time referrals. The data outlined in this section reveals the number of services provided, by program, in the fiscal year of 2023. Each program is meant to satisfy two objectives: eliminating poverty and empowering residents to achieve economic security. The snapshot below is meant to illustrate the wide breadth of services that UPO provides.

161individualscametoUPOforSocial EmotionalLearningprogramming

123individualsparticipatedinUPO academicenrichmentclasses

Housing

136individualscametoUPOfor emergencyrentalassistance

80individualscametoUPOfordirect rentpayments

57individualscametoUPOforhousing supplies

37individualssignedupforUPOGED programs

579individualscametoUPOfor housingcasemanagementservices

82individualssignedupforUPO’s homemanagementclasses

87individualsparticipatedinsocialemotionallearningworkshops

340individualsenrolledinmental healthservicesandcounselling

388individualscalledUPOforcrisis intervention

251individualssignedupforUPO medicationandmonitoringprogram

147individualsenrolledinUPO’s groceryfooddistributionsystem

54individualsreceivedpreparedmeals

120individualscametoUPOforfree meals

21individualsenrolledinUPO’shealthy cookingclass

808individualscametoUPOfortax preparationprograms

289individualsenrolledinUPO’spostcoachingemploymentprogram

327individualsusedUPO’s transportationstipend

1,386individualscompletedUPO’s intakeprocess

The 2024 Community Assessment provides a representative sample size of resident demographics within the District and UPO locations. For this reason, UPO opted to emphasize statistically proven methods to collect data upon District residents. This involved the previously mentioned mail-in survey, including weighting the results of the survey more heavily than the “boots on the ground” survey distribution method and the email survey method. In 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, UPO conducted an online survey. Despite reaching more people, UPO researchers found that the data had been breached by malicious actors attempting to spam the survey in order to receive incentives extended to respondents. As a result, much of the data had to be thoroughly cleaned. Moreover, because the survey was conducted online, the survey had self-selected residents who were of higher income.

The survey data collected in the 2024 Community Assessment Survey was more in line with UPO’s customer demographics, as UPO predominately focused on areas of the District which were experiencing generational poverty. Poverty disproportionately impacts Black and Brown residents, meaning a vast majority of the responses came from Black and Brown households. This is reflected by the ward data response rate as well. In 2024, UPO acquired more responses from Wards 7 and 8.

UPO is likely to have surveyed more individuals who had only completed their high school diploma, as residents who have not obtained a bachelor’s struggle to achieve employment and thus a living wage, to reside in high income areas. These areas are predominately in Wards 7 and 8.

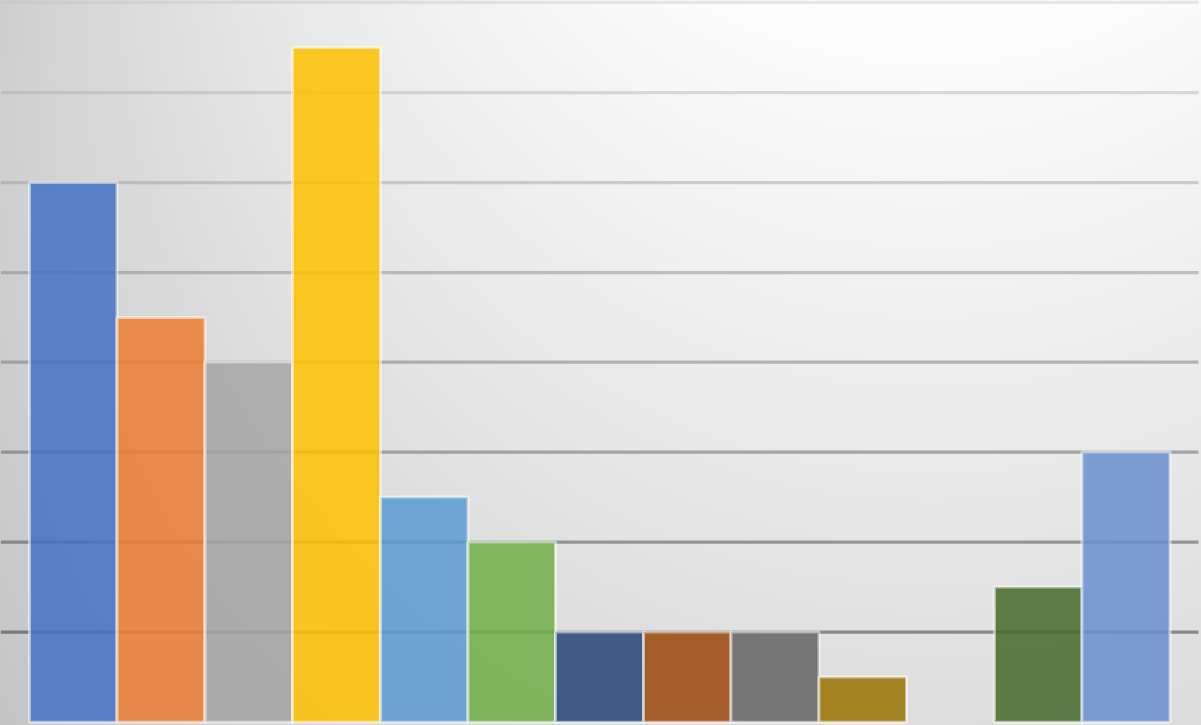

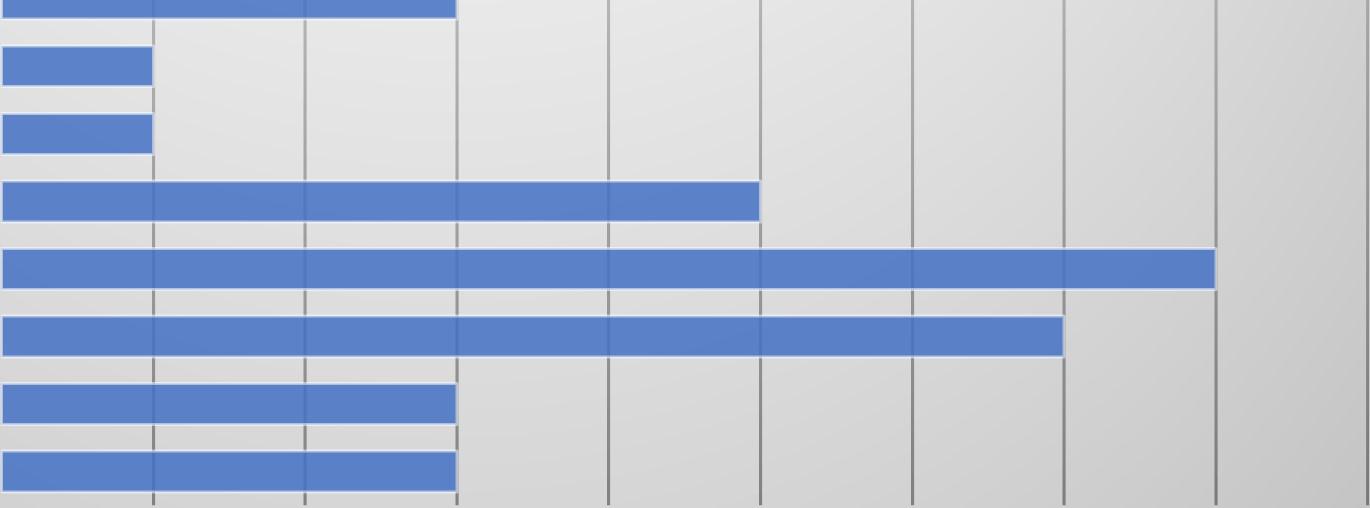

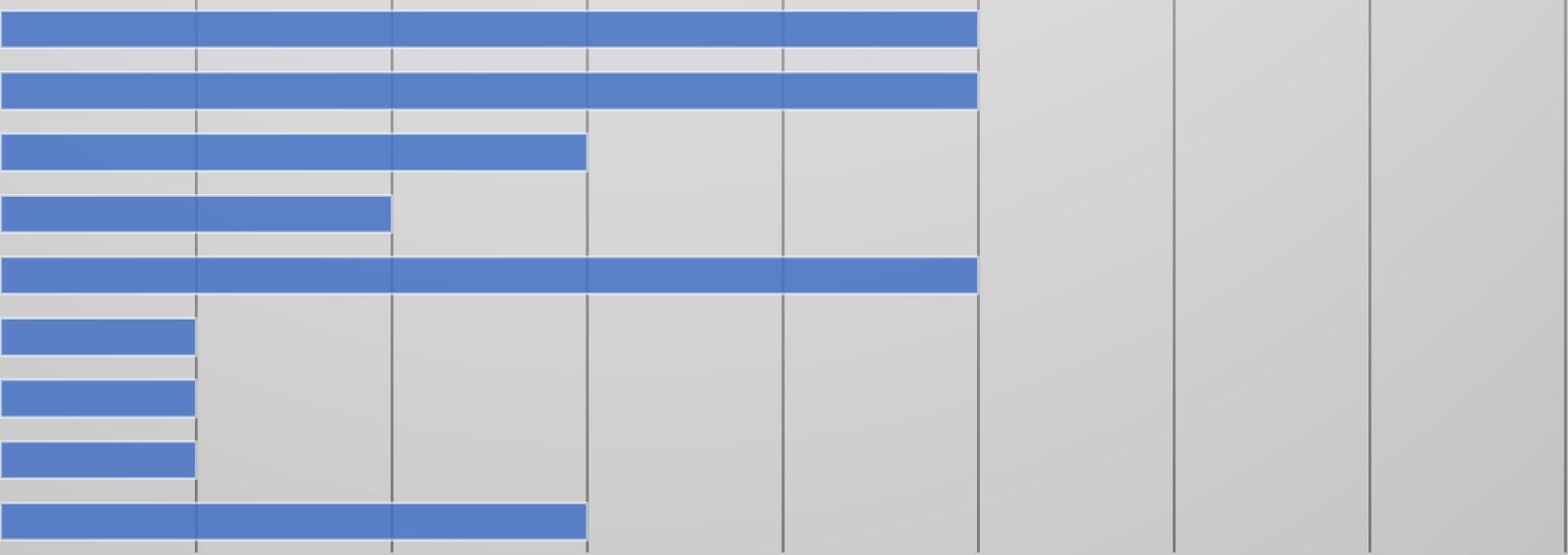

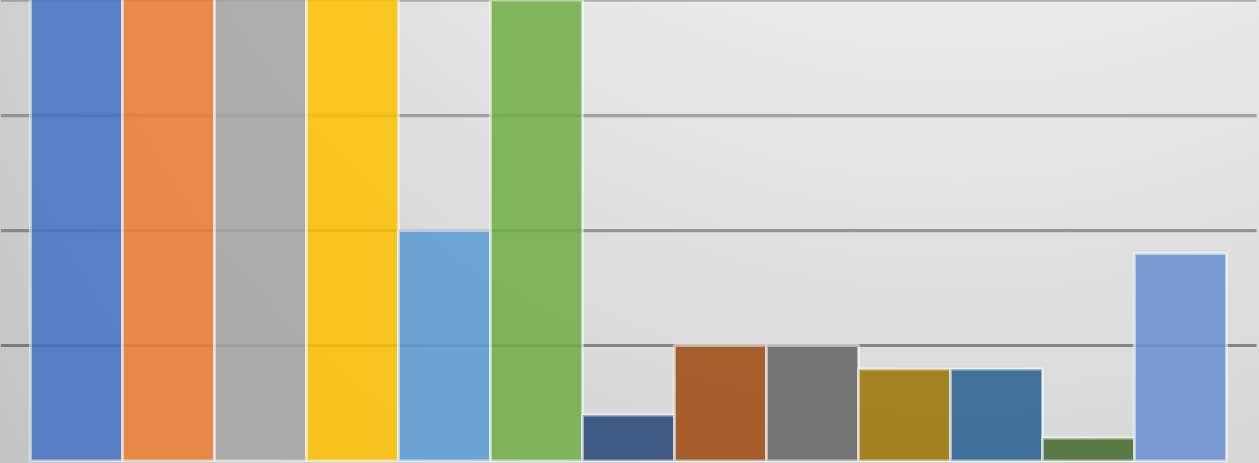

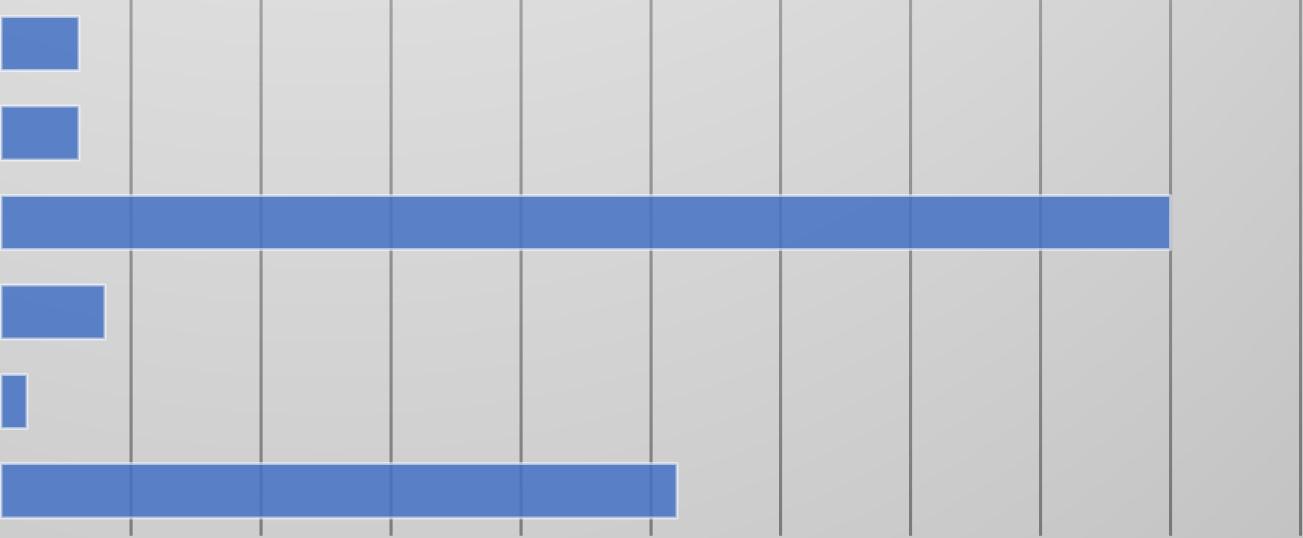

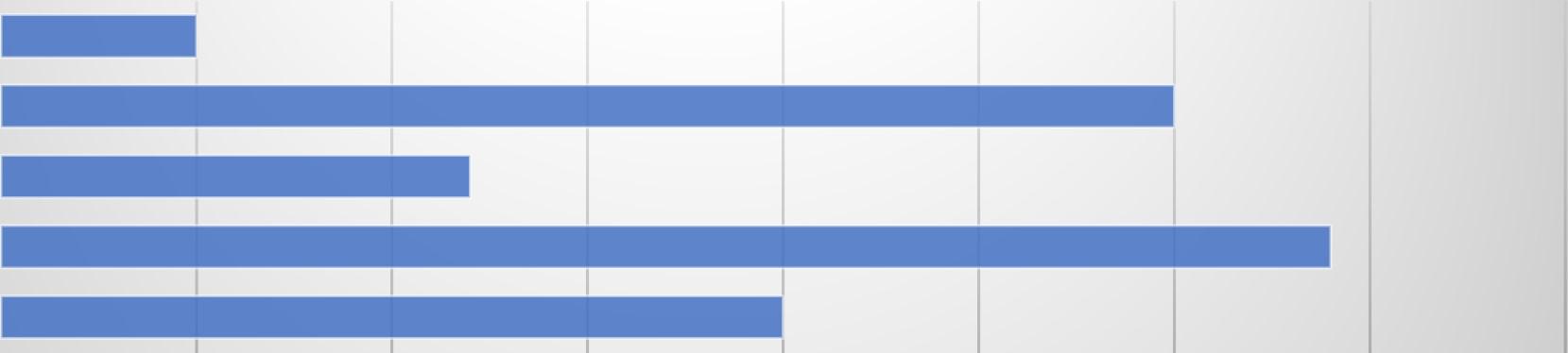

Table 3: Survey Response: Health Coverage Comparison

Health insurance is also a predominant issue for low-income residents in the District. Nearly 77% of low-income DC residents rely on government health insurance programs to obtain basic medical care.

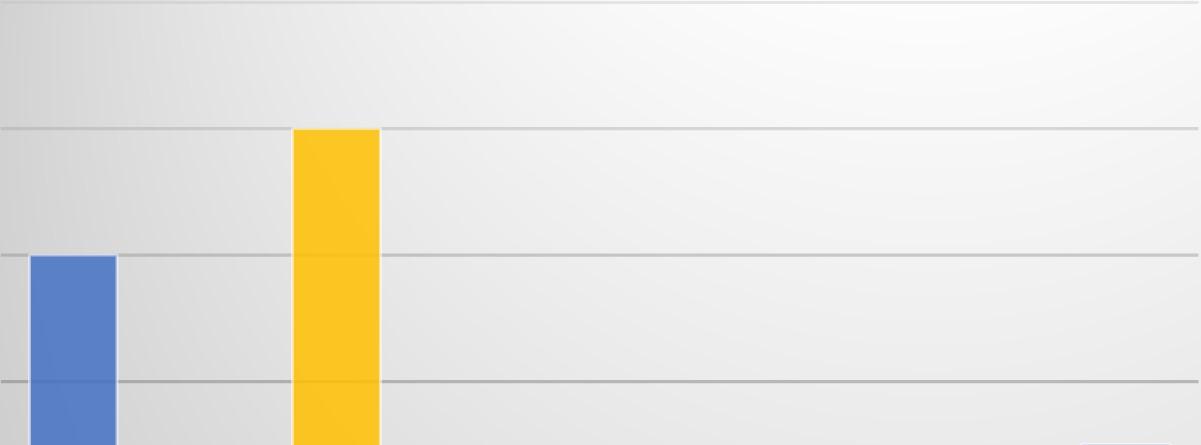

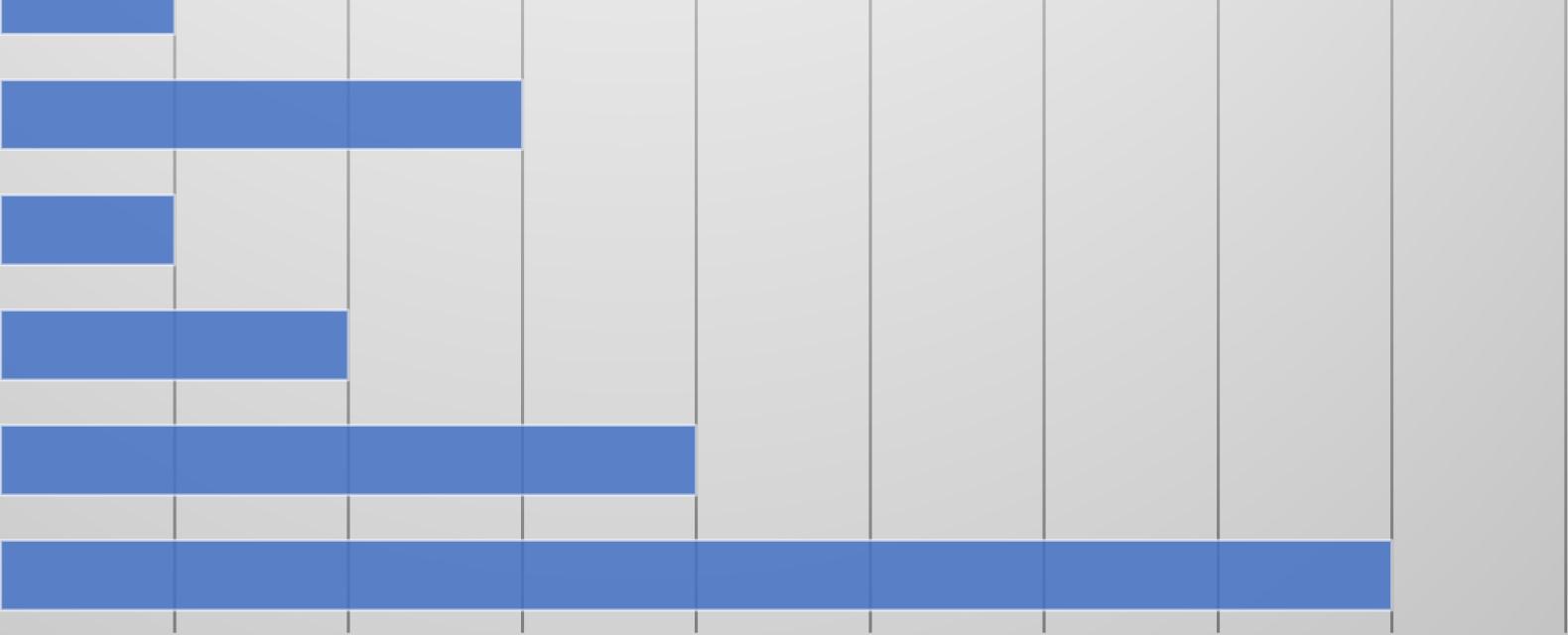

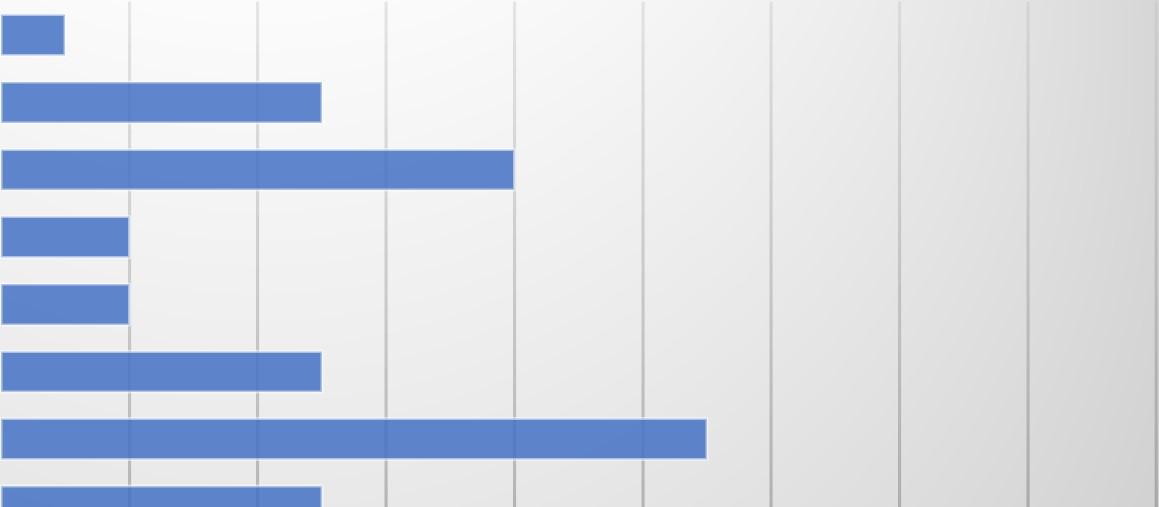

The income collected in 2024 was more representative of UPO’s customer base, than compared to 2021. UPO had received more survey responses from residents of lower-income, reflected by the table below. This report does not indicate that poverty has in fact increased in the District, rather, that UPO was able to obtain a more representative sample.

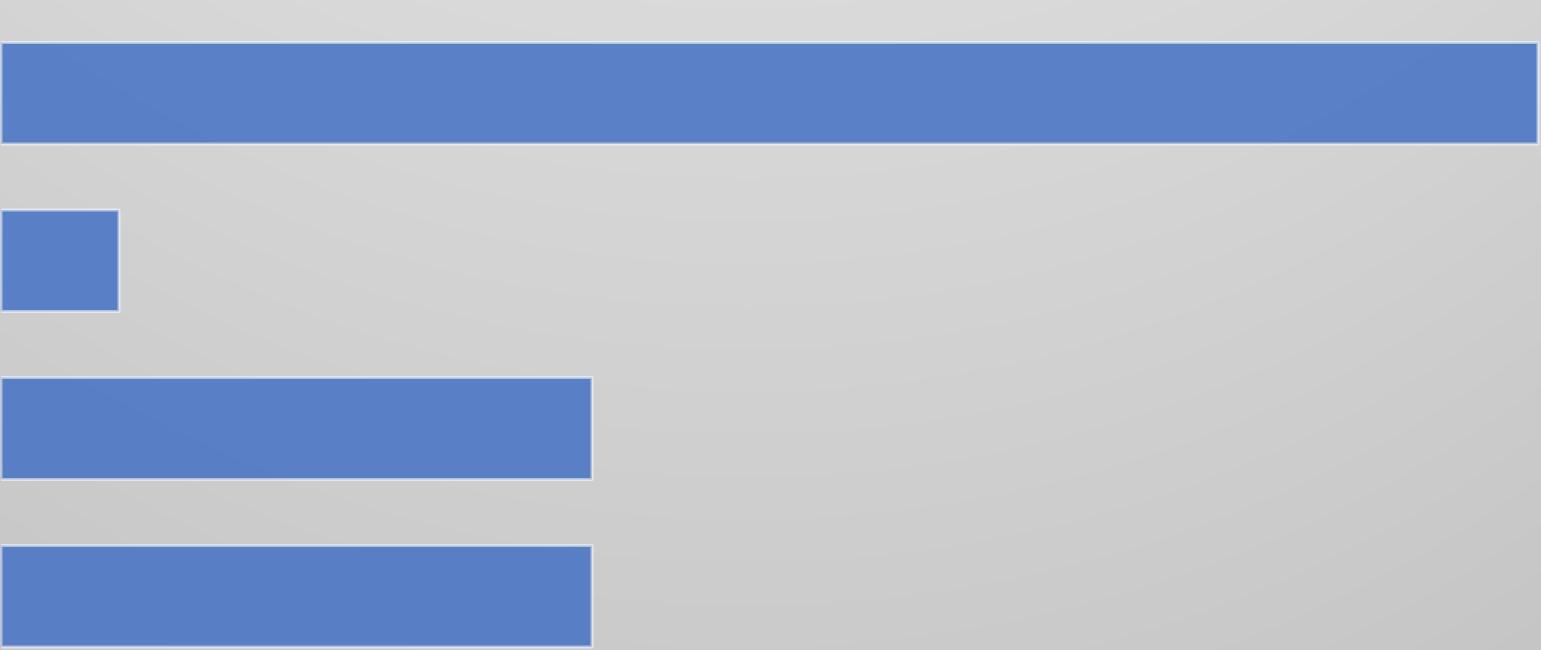

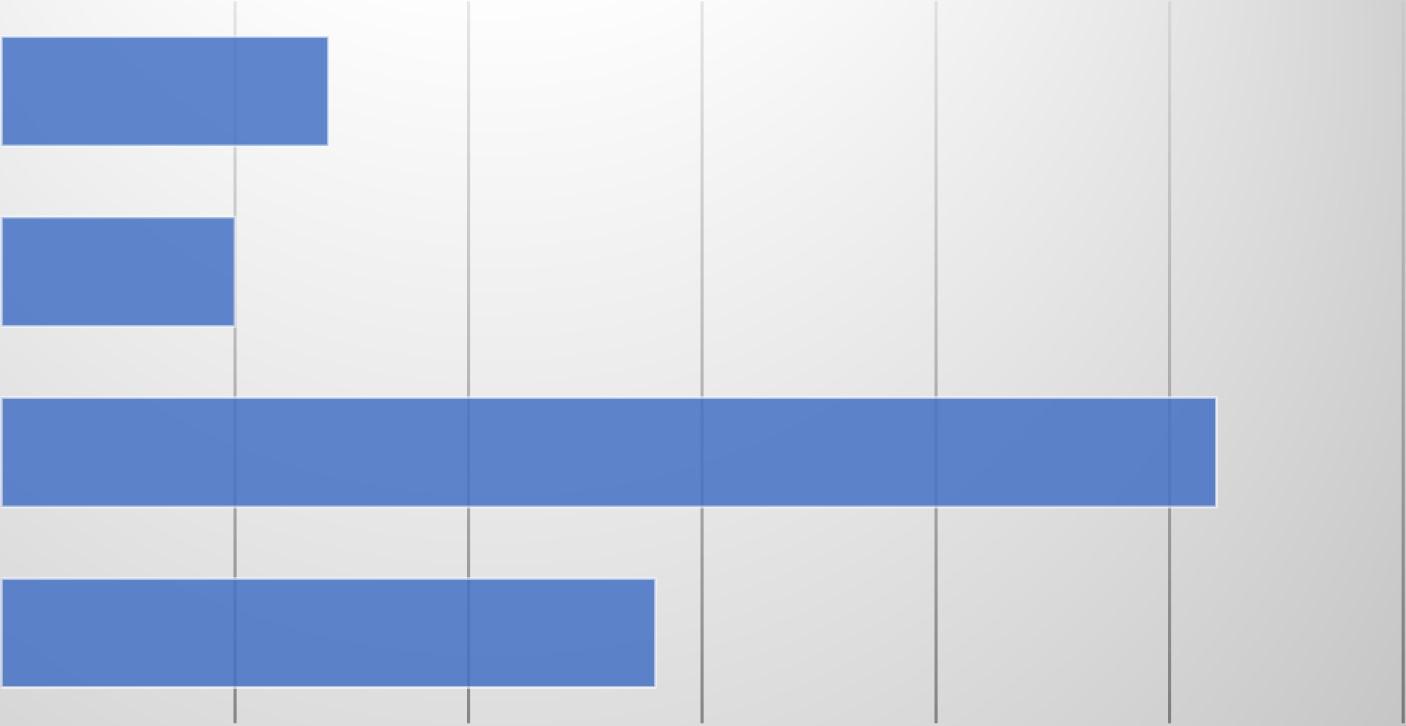

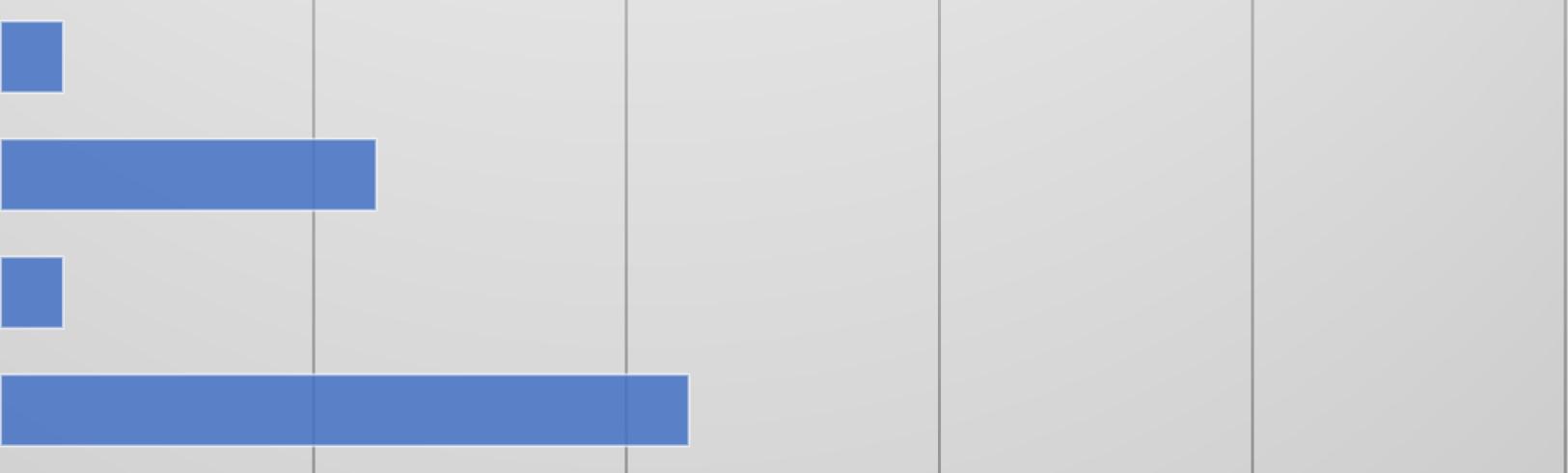

Table 4: Survey Response: Income Comparison

$0-$24,999

$25,000-$34,999

$35,000-$44,999

$50,000-$74,999

$75,000-$99,999

$100,000+

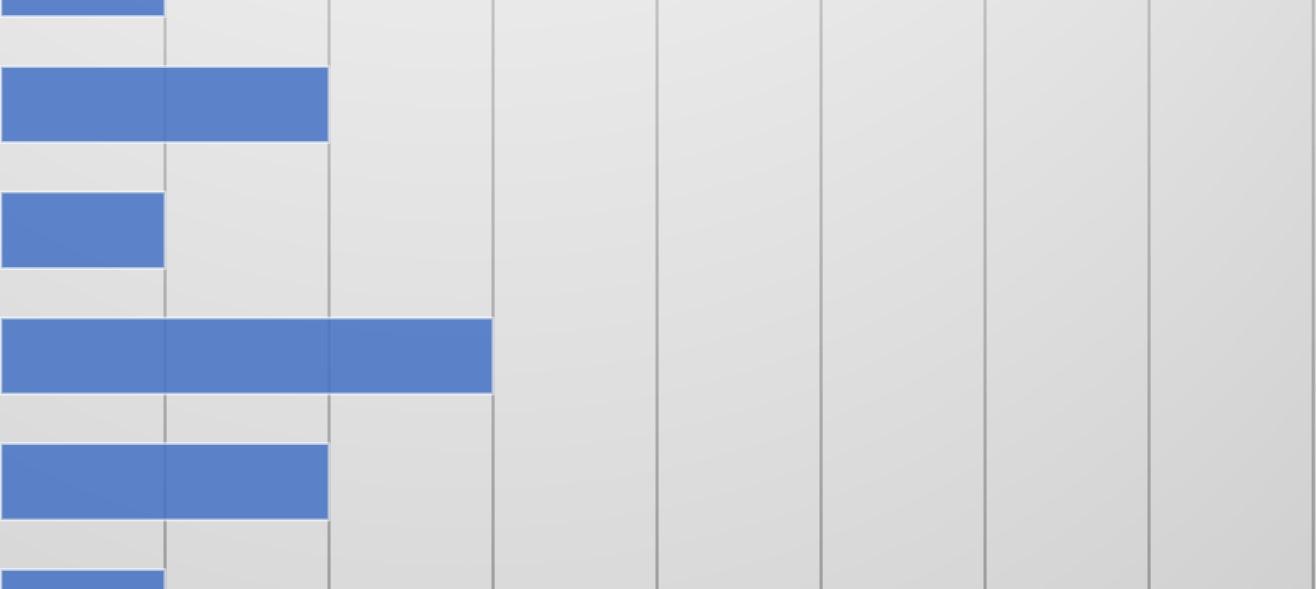

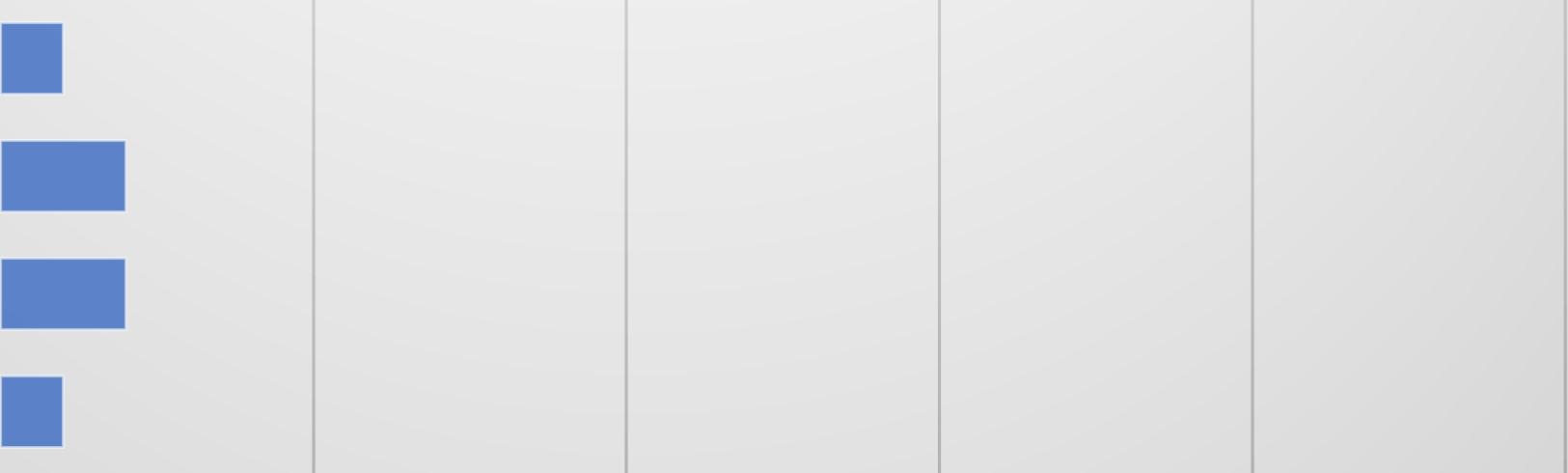

The high response rate of low-income residents from across the District drastically impacts other demographic information. For example, low-income residents across the District are less likely to own a home or pay a mortgage. This is also reflected in the responses of the 2024 Community Assessment.

Table 5: Survey Response: Household Situation Comparison

There is a significant gap in responses between homeowners and renters in the 2024 Community Assessment. Moreover, individuals who do not pay a mortgage constituted only 1% of total respondents, indicating that renters in the District have a higher chance of being lowincome.

Like many cities across the country, the District of Columbia saw a decline in total population during the COVID-19 pandemic. An estimated 20,000 individuals left the District from 2020 to 2022 according to the American Community Survey (total population decreased from 689,545 residents to 671,803 residents).1 Though publicly available data about those who left the District during this period, trends across the country indicate that small, wealthy families fled the District towards the perceived safety of the suburbs.

The largest segment of the population continues to be 25- to 34-year-olds, with 145,253 individuals.2 Though, this segment of the population also saw one of the largest decreases since 2020. The median age is 34.9 years old.3 Seniors (65+) only make 13% of the total population.4 Children under the age of 18 make up 18% of the total population.5 The percentage of seniors and children within the District has been stable since the pandemic. The male to female ratio expanded slightly in 2022. Currently, the population stands at 46.9% male and 53.1% female.6

The District of Columbia is the 6th largest Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) in the country. The city is divided into eight wards and further divided into 46 Advisory Neighborhood Commissions (ANCs), as of the 2022 redistricting.7 Additionally, the District has over 200 census tracts, which are small geographic areas defined for collecting and reporting census data from the U.S. census. These census tracts can be aggregated by several other geographic boundaries such as wards or police service areas (PSA). Data reported in this Community Assessment reflects the needs of Washington, DC residents and may include city-wide, wardlevel, or census tract data.

1 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

2 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

3 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

4 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

5 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

6 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

7 DC.gov. 2023. Advisory Neighborhood Commissions. Retrieved on September 14, 2023 from https://anc.dc.gov/page/about-ancs

Wards are purposely designed to house an evenly distributed number of households. Currently, each ward has a population between 80,000 and 90,000 people. The new boundaries for DC Wards took effect in January of 2022.

The racial composition in the District has changed drastically over the past twenty years. The population percentage gap between Black and white population has been decreasing rapidly as a result of gentrification and limited affordable housing. In 2020, Black residents made up 41.4% of the population while white residents made up 39.6%. In 2022, the gap between the two populations grew slightly, with Black residents composing 42.1% of the population and whites composing 38.4%.8 The changes in racial distribution in the District can be attributed to the shrinking population as the District becomes more unaffordable as well as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Hispanic population of the District has remained stable throughout the pandemic, sitting at 11.7%.9 The number of individuals who identify as having two or more races has increased to 10.2% of the total population.10

Like many cities across the country, the District of Columbia saw a decline in total population during the COVID-19 pandemic. An estimated 20,000 individuals left the District from 2020 to 2022 according to the American Community Survey (total population decreased from 689,545 residents to 671,803 residents).11 Though publicly available data about those who left the District during this period, trends across the country indicate that small, wealthy families fled the District towards the perceived safety of the suburbs.

The largest segment of the population continues to be 25- to 34-year-olds, with 145,253 individuals.12 Though, this segment of the population also saw one of the largest decreases since 2020. The median age is 34.9 years old.13 Seniors (65+) only make up a small percentage of the District of 13%.14 Children under the age of 18 make up 18% of the total population.15 The percentage of seniors and children within the District has been stable since the pandemic. The

8 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

9 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

10 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

11 U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

12 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

13 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

14 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

15 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table DP05.

male to female ratio expanded slightly in 2022. Currently, the population stands at 46.9% male and 53.1% female.

Though the District has seen record economic growth in the past decade, the city experiences high levels of inequality and unemployment. Barriers to economic security are not based upon individual effort, rather, systemic barriers prevent communities or individuals from seeing potential economic gains. Economic mobility and economic inequality have a strong correlation. To ensure all communities have access to equal opportunities, the District must address problems in communities that are struggling in obtaining economic security. Typically, struggling communities are inhabited by people of color who have been systematically discriminated against through segregation policies, redlining and urban renewal.

In the DMV region, the District exhibited the largest negative racial disparities in employment, income and poverty.16 White residents have a median household income of $141,650, nearly three times as high as the median household income for Black residents of $45,072.17 Debt is also not evenly distributed across the District. Poorer, historically Black communities east of the Anacostia River are twice as likely to have delinquent debt.18 Nearly 50% of the residents in Wards 7 and 8 have delinquent debt. With higher levels of debt and lower levels of income, poorer residents are also more likely to have difficulty recovering from economic shocks or an unplanned expense. The Urban Institute estimates that only 42% of households east of the Anacostia River have at least $2,000 in savings, compared to 70-89% of the rest of the city.19

Because of the systemic financial economic constraints placed upon poorer communities, Black and Brown residents are more likely to face generational poverty. Black households are more likely to have higher levels of debt and lower levels of income, meaning there is less opportunity

16 Busette & Elizondo. 2022. Economic disparities in the Washington, D.C. metro region provide opportunities for policy action. Brookings. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/economic-disparities-in-the-washington-d-cmetro-region-provide-opportunities-for-policy-action/.

17 Busette & Elizondo. 2022. Economic disparities in the Washington, D.C. metro region provide opportunities for policy action. Brookings. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/economic-disparities-in-the-washington-d-cmetro-region-provide-opportunities-for-policy-action/.

18 Santillo et al. 2022. Washington, DC, has glaring financial health inequities. So do most American cities. The Urban Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/washington-dc-has-glaring-financial-health-inequitiesso-do-most-american-cities

19 Santillo et al. 2022. Washington, DC, has glaring financial health inequities. So do most American cities. The Urban Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/washington-dc-has-glaring-financial-health-inequitiesso-do-most-american-cities

to invest and transfer wealth generationally. White households in Wards 2, 3 and 4 have a net worth 65 times higher than Black households residing in Wards 7 and 8.20

The scale of the District’s income inequality can also be measured using the Gini coefficient. A score of 0.0 on the Gini index would indicate perfect equality in income distribution, whereas a score of 1.0 would indicate total inequality. The District has the second highest level of inequality in the country, behind Puerto Rico, with a score of .53.21 Though this statistic may be alarming, it is difficult to compare the District, a diverse city, to large states across the country. When compared to other cities across the country, like New York City, D.C. is only slightly more unequal.22

Income inequality within the District is quite pronounced, and disproportionately affects residents of color. To lower economic inequality, the District must promote opportunities to residents to escape poverty and achieve economic security, while redistributing resources to low-income communities.

High levels of income inequality and poor economic mobility can be explained by employment and unemployment. Over the past three years, the District has seen an increase in overall employment. As of May of 2023, the District has gained 3,400 jobs.23 The unemployment rate has fallen back to pre-pandemic levels of 4.6%.24 Despite the strong overall economy, unemployment is still high for minority groups.

The white unemployment rate has remained very low at 1.4% in 2023.25 However, Black unemployment remains stubbornly high, with an unemployment rate of 9.6%.26 Nearly half of

20 Santillo et al. 2022. Washington, DC, has glaring financial health inequities. So do most American cities. The Urban Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/washington-dc-has-glaring-financial-health-inequitiesso-do-most-american-cities

21 Statista. 2023. Gini coefficient as a measure for household income distribution inequality in the United States 2021, by state. Retrieved from September 1, 2023 from https://www.statista.com/statistics/227249/greatest-gap-between-rich-and-poor-by-usstate/

22 Austermuhle, Martin. 2014. D.C: Even more unequal than you may have thought. WAMU. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://wamu.org/story/14/10/31/dc_even_more_unequal_than_you_thought/

23 Department of Employment Services. 2023. District of Columbia looks forward, unemployment rate at 5.1 percent in May. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://does.dc.gov/release/district-columbia-looks-forward-unemployment-rate-51-percentmay#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20employed%20District,to%20391%2C900%20in%20May%202023.

24 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

25 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

26 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

all unemployed Black workers in 2022 were out of work for six months or more.27 Black workers were five times as likely to be underemployed than white workers.28 The trend of high Black unemployment and low white unemployment has been consistent since 2000. Between 2000 and 2022, Black unemployment never fell below 8.3% while white unemployment never rose above 4.1%.29 Employment in the District often caters towards highly educated individuals meaning many communities that may not have access to quality education may struggle finding employment.

The District of Columbia has a higher-than-average poverty rate compared to the rest of the United States. Nearly 17% of residents in the District currently fall under the federal poverty line (FPL) compared to 13% of the citizens across the United States.30 Like income, poverty is also not equally distributed across the District. Wards 3 and 4 have historically been wealthier areas, while Wards 5, 6, 7 and 8 have been poorer. The difference between these wards is quite stark. For example, Ward 8 has a recorded poverty rate of 30% with a median household income of $38,000, while Ward 3 has a poverty rate of 7.9% and a median household income of $133,750.31

Poverty is also not equally distributed by race. For example, Ward 1 has a poverty rate of 11.2%. However, only 2.9% of white individuals live under the FPL, compared to 30.8% of Black individuals.32 The racial disparity between white and Black individuals extends even to wealthier wards. In Ward 3 for instance, only 5% of white individuals fall below the FPL compared to 28% of Black individuals.33 Individuals who did not obtain a high school diploma or GED struggled regardless of ward residence.

27 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

28 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

29 Schnur & Williams. 2023. DC’s extreme black-white unemployment gap is worst in the nation. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on September 1, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-extreme-black-white-unemployment-gap-is-worst-in-thenation/#:~:text=Black%20unemployment%20in%20DC%20is,the%20worst%20in%20the%20nation.

30 Census Bureau. 2021. 2021 American community survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://data.census.gov/profile/District_of_Columbia?g=040XX00US11

31 Census Bureau. 2021. 2021 American community survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://data.census.gov/profile/District_of_Columbia?g=040XX00US11

32 Census Bureau. 2021. 2021 American community survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://data.census.gov/table?q=poverty&g=610XX00US11001,11002,11003,11004,11005,11006,11007,11008

33 Census Bureau. 2021. 2021 American community survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://data.census.gov/table?q=poverty&g=610XX00US11001,11002,11003,11004,11005,11006,11007,11008

Child poverty persists despite increasing family incomes. Wealthier wards such as Ward 3 have low child poverty rates, with only 1.5% of children under 18 falling below the FPL. Every other ward in the District has a child poverty rate of above 10%.34

Barriers to employment exist for residents who have not graduated high school and returning residents. While there is an extensive network of nonprofit organizations as well as state institutions to assists struggling residents with employment, the barriers to employment are often structural in nature. For example, many struggling workers may need education in literacy and numeracy.35 Other factors include transportation access, housing stability and family stability. Often, inability to secure employment stems for societal factors such as where an individual was raised, their access to education and other various support networks. Therefore, connecting individuals with employers means addressing structural issues facing the community, rather than simply training an individual in a skill and sending out a resume.36

Education is the largest barrier of entry for District residents. While the District has done an excellent job recruiting talent from elsewhere in the country, it has often avoided supporting careers of individuals who grew up in the city. Of the top ten most requested jobs in the District, all jobs require a bachelor’s degree or higher to be considered for employment.37 There is not a single career on the list that at minimum, needs less than a high school diploma or GED. Many of the most requested careers pay more than $100,000 dollars a year. The Department of Employment services also provide information about in-demand careers for individuals who lack a high school diploma. Of the top 50 jobs listed, only 20 careers make more than $40,000 dollars a year and none (baring athletes and artists) make more than $70,000 dollars.38 Providing quality education and ensuring that students can graduate with basic literacy and numeracy skills is integral for career development after graduation.

34 Census Bureau. 2021. 2021 American community survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://data.census.gov/table?q=poverty&g=610XX00US11001,11002,11003,11004,11005,11006,11007,11008

35 Grant, Bruce. 2018. Reducing barriers for job-seekers. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/reducing-barriers-for-job-seekers-in-d-c-and-the-metro-region/

36 Grant, Bruce. 2018. Reducing barriers for job-seekers. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/reducing-barriers-for-job-seekers-in-d-c-and-the-metro-region/

37 Department of Employment Services. 2022. The top 50 high demand occupations. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://does.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/does/page_content/attachments/2023%20Hot%20Jobs%2050_0.pdf

38 Department of Employment Services. 2022. The top 50 high demand occupations requiring less than a high school diploma Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://does.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/does/page_content/attachments/2023%20Hot%20Jobs%20Visual%20below%20G ED.pdf

Returning from incarceration also poses a significant barrier to employment. Individuals with a criminal history tend to struggle with finding employment after leaving incarceration on a national level, but the issue is much more pronounced in the District. Over 50% of individuals experiencing homelessness have claimed to have been incarcerated.39 The struggle to procure employment stems from a poor housing situation and the general stigma against hiring individuals who have been convicted of certain crimes. Though institutions such as the Georgetown Pivot program provide support to returning residents, the high rates of homelessness amongst returning residents indicates that the issue is larger than individual experiences.

The factors that individuals may face when searching for employment disproportionally affect Black and Brown residents. As of 2023, labor force participation for young white adults is 11% higher than the labor force participation for young Black adults. Young Black job seekers claimed that they had experienced workplace discrimination, struggled to find work, or lacked the proper mentorship.40 Struggling to find and maintain employment early in life can have disastrous consequences in the future. Unemployment in an individual’s early and late 20s is directly correlated with poor job quality and poverty in an individual's 30s.41 In the District, unemployment and difficulty seeking employment disproportionately affect young Black individuals.42

Overview of Health in the District

Life expectancy has dropped significantly in the U.S. for a number of reasons: COVID-19, the opioid epidemic and lack of access to healthcare services. As of 2020, the average U.S. citizen is expected to live 77.28 years. District residents can expect to live for 78 years.43

39 Coventry, Kate. 2020. Coming home to homelessness. DCFPI. Retrieved on August 30, 2023 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/coming-home-tohomelessness/#:~:text=Nearly%20three%20of%20five%20DC%20individuals%20experiencing%20homelessness%E2%80%9457,h omelessness%20in%20DC%20connect%20that%20to%20their%20incarceration.

40 Schnur, Caitlin. 2024. DC’s labor market is failing young black workers. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on August 19, 2024 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-labor-market-is-failing-young-black-workers/

41 Ross, Martha, et. al. 2018. High-quality jobs for young adults. Brookings Institute. Retrieved on August 19, 2024 from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Brookings_Child-Trends_Pathways-for-High-Quality-Jobs-FINAL.pdf

42 Schnur, Caitlin. 2024. DC’s labor market is failing young black workers. DC Fiscal Policy Institute. Retrieved on August 19, 2024 from https://www.dcfpi.org/all/dcs-labor-market-is-failing-young-black-workers/

43 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

However, there are several health disparities between District residents. For example, the average age-adjusted death rate, which calculates the average number of premature deaths in a given area, is 433 in the District.44 The age-adjusted death rate for white residents is 130, while for Black residents, the age-adjusted mortality rate is 702, nearly 5.5 times higher.45 The disparities in race touch every aspect of health in the District. The child mortality rate, for instance, is three times higher for Black children than it is for white children.46

Over the course of the pandemic, experts advised the public to prioritize their mental health, leading to ongoing discussions about the various factors that affect mental wellbeing. Though the height of the pandemic has receded, the conversations on the salience of mental health are still ongoing. The definition of mental health is loosely defined, yet it is collectively understood to include individual’s emotional and psychological wellbeing.47

The public emphasis on mental wellbeing is ever present in the District. Both adult and child mental health services have seen a seven million dollar increase since 2021.48 This is the result of an 8% of health care services requested by District residents, for a total of 41,560 services requested in 2022.49 The increase in mental health services requested is a direct result to rising rates of symptoms of depression and anxiety within the District. In 2023, nearly 30% of residents reported a major depressive disorder.50 Of the residents who reported depressive episodes, nearly 50% reported that their needs were unmet.51 Unmet health assistance may stem from the financial burden associated with therapy and other mental health services. In 2023, the average therapy session costs 150-200 dollars.52

44 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

45 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

46 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

47U.S Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). What is mental health? Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/mentalhealth on 8/4/2023.

48 Department of Behavioral Health. (2022). Mental health and substance abuse report on service expenditures. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023.

49 Department of Behavioral Health. (2022). Mental health and substance abuse report on service expenditures. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023.

50 KFF. (2023). Mental Health in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023

51 KFF. (2023). Mental Health in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023

52 Brad Brenner. (2023). How much does therapy cost? Average cost of therapy in DC. Therapy Group of D.C. Retrieved from https://therapygroupdc.com/therapist-dc-blog/how-much-does-therapy-cost-average-cost-of-therapy-in-dc/ on 8/4/23.

The costs of poor mental health are not distributed evenly across the District. Individuals with mental illnesses report spending roughly 1,600 dollars out of pocket for mental health services.53 Individuals without mental illness report spending a third of that number.54 Low-income residents are far less likely to have access to mental health services within their budgets. There are also disparities across geography. Wards 7 and 8 report higher needs of mental health services than the rest of the District.55

If mental health services are deemed too expensive, individuals may turn to self-medication as a form of coping, which can lead to substance abuse. The District has wrestled with substance abuse for years, and many who experience mental illness also report high rates substance abuse. In 2023, nearly 5,300 District residents sought substance abuse services from a D.C. government affiliated provider.56 Just over 3,100 individuals who sought substance abuse assistance also requested mental health services from the same provider.57

In 2022, there were 461 opioid-related fatal overdoses, with an average of 38 deaths per month.58 By May of 2023, there were 192 opioid-related fatal overdoses, indicating a steep increase in overdoses within the District. The high number of opioid-related deaths has been a consistent trend in the District since 2018. Older residents are particularly susceptible to opioid overdose. As new, more potent drugs enter the market, older users may have a harder time distinguishing their old supply of opiates. Thus, older residents are more likely to experience repeat overdoses.59 The city’s opioid problem is also more likely to affect Black residents. The

53 KFF. (2023). Mental Health in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023

54 KFF. (2023). Mental Health in the District of Columbia. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023

55 D.C. Health Matters. (2023). Mental Health Needs. Retrieved from https://www.dchealthmatters.org/indexsuite/index/mentalhealth?localeType=3&parentLocale=130951&locale=9405 on 08/04/2023.

56 Department of Behavioral Health. (2022). Mental health and substance abuse report on service expenditures. Retrieved from https://dbh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmh/page_content/attachments/MHEASURES%20Report%20January%202023.p df on 8/4/2023.

57 57 D.C. Health Matters. (2023). Mental Health Needs. Retrieved from https://www.dchealthmatters.org/indexsuite/index/mentalhealth?localeType=3&parentLocale=130951&locale=9405 on 08/04/2023.

58 Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. 2023. Opioid-related fatal overdoes: January 1, 2017, to May 31, 2023. Retrieved on August 29, 2023 from https://ocme.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocme/page_content/attachments/Opioid%20related%20Overdoses%20Deaths_A ug%202023.pdf

59 Turilli, Isabella. 2022. Opioid overdoses are reaching new highs in Washington DC. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/opioid-overdoses-are-reaching-new-highs-washington-dc

average opiates user in DC is Black and between the ages of 55-64.60 Black residents also make up 85% of overdose deaths from opioids.61

To curb overdose deaths, D.C. restaurants have been given permission to distribute Narcan. The drug can also be found in vending machines across the city. Virtual Narcan training education is also provided by the District.

Adverse perinatal outcomes, defined as low birth weight, small for gestational age, preterm birth, stillbirth, or neonatal death, are all issues mothers in D.C. must be conscious of. The District in recent years has struggled to address high rates of adverse perinatal outcomes. Maternal health and wellness are correlated with birth outcomes. For example, if a mother undergoes prenatal care during the first trimester, the child is more likely to be born a healthy birth weight.

The District currently holds the highest maternal mortality rate in the country with 36 deaths per every 100,000 births.62 Low-income residents, particularly in Wards 5, 7 and 8, lack perinatal care. Systemic racism and gendered racism—or the oppression that emerges from the intersection of race and gender—contribute to many of the disparities seen in maternal health and well-being in the United States. In a recent study conducted by Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, researchers identified that “[The District] created a predatory health care system that is both inaccessible and unaffordable for Black women.”63 Participants were interviewed as part of the report, where all participants shared at least one experience with racism in pregnancy-related visits to healthcare providers. Postpartum care is also another area that low-income BIPOC mothers struggle to access. 64

60 Turilli, Isabella. 2022. Opioid overdoses are reaching new highs in Washington DC. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/opioid-overdoses-are-reaching-new-highs-washington-dc

61 Turilli, Isabella. 2022. Opioid overdoses are reaching new highs in Washington DC. Retrieved August 29, 2023, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/opioid-overdoses-are-reaching-new-highs-washington-dc

62 Bhatnagar et. al. 2022. Racism blleds throughout this entire health care system: elevating black women’s birth stories in Washington, DC through a racial equity lens. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Retrieved on August 29, 2023 from https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/UPD_GU_Racism-Bleeds-throughout-this-Entire-HealthcareSystem.pdf

63 Bhatnagar et. al. 2022. Racism blleds throughout this entire health care system: elevating black women’s birth stories in Washington, DC through a racial equity lens. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Retrieved on August 29, 2023 from https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/UPD_GU_Racism-Bleeds-throughout-this-Entire-HealthcareSystem.pdf

64 Bhatnagar et. al. 2022. Racism blleds throughout this entire health care system: elevating black women’s birth stories in Washington, DC through a racial equity lens. Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development. Retrieved on August 29, 2023 from https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/products/UPD_GU_Racism-Bleeds-throughout-this-Entire-HealthcareSystem.pdf

Systemic racism also impacts the infant mortality rate. In 2023, there were 446 infant deaths, for an infant mortality rate of 7.65 White residents have an infant mortality rate of 2, while Black residents have an infant mortality rate of 12.66

As of 2023, there are an estimated 357 childcare centers across the District, or 8 childcare centers per 1,000 children.67 Though the District has a robust number of childcare services, the percentage of household income required to pay for childcare expenses remains quite high. An estimated 27% of household income is needed to pay childcare services providers.68

On June 28th, 2022, the Supreme Court voted to overturn Roe v. Wade, meaning the legality of abortion is determined by the state. The decision effectively ended five decades of constitutionally protected abortion rights. Despite the decision, the District has expanded abortion access for out-of-state travelers.69 However, because of the District’s precarious relationship with Congress, funds for abortion access could be taken away in the next budget cycle. Lawmakers continue to uphold a budget rider that prevents the District from subsidizing abortions for low-income individuals.70

Food insecurity is linked to asthma, dental and developmental problems, colds, cancer, heart disease, pregnancy complications, congestive heart failure and lower cognitive function in adults.71 Food insecurity, therefore, effects the District residents who cannot easily afford food essentials. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP has seen steady increases in enrollment since the pandemic. As of 2023, approximately 145,800 individuals have enrolled in

65 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

66 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

67 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

68 County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. 2023. 2023 County Health Rankings District of Columbia data – v2. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/district-of-columbia/data-and-resources

69 Grablick, Colleen. 2023. One year after Roe’s fall, here’s where abortion access stands in the D.C. region. DCist. Retrieved on September 11, 2023 from https://dcist.com/story/23/06/28/dobbs-one-year-later-dc-maryland-virginia/

70 Grablick, Colleen. 2023. One year after Roe’s fall, here’s where abortion access stands in the D.C. region. DCist. Retrieved on September 11, 2023 from https://dcist.com/story/23/06/28/dobbs-one-year-later-dc-maryland-virginia/

71 District of Columbia Department of Health. (2019). Our healthy DC. Food security. Retrieved August 28, 2023 from https://ourhealthydc.org/dc-chna/health-outcomes/mental-health/

the program.72 Current SNAP enrollment numbers are a sizeable increase from 2019, where approximately 94,000 individuals were enrolled.

Though food insecurity rates have been steadily decreasing within the District, certain populations are still vulnerable to the issue. For those living East of the Anacostia River, buying food may be a difficult task. Nearly 31% and 51% of Wards 7 and 8 are considered a “food desert” respectively.73 A food desert is an area where grocery stores or markets are located more than half a mile from a residence. Typically, areas labeled as food deserts have low rates of car access and high rates of poverty. The estimated food insecurity rate was 11% in 2021.74 Low-income seniors are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity. The insecurity rate amongst seniors as 13% in the District of Columbia.75

As of 2022, there are 350,364 housing units in the District of Columbia.76 However, there are only 326,970 occupied units.77 Of the current housing stock, 161,140 units are a part of apartment units with 10 or more housing units.78 The next largest supply of housing stock is a single-family attached home, of which the District has an estimated 71,120 units.79 Much of the current housing stock is rapidly aging. Nearly 32% of the current housing stock was built before 1939.80

In 2022, the homeownership rate was 42%, significantly lower than the national average.81 The District’s low homeownership rate can be attributed to much of its housing stock being primarily

72 Schilke, Rachel. 2023. Food stamps: SNAP benefits for September to arrive for DC residents in four days. Washington Examiner. Retrieved on August 28, 2023 from https://gazette.com/news/wex/food-stamps-snap-benefits-for-september-to-arrive-for-dcresidents-in-four-days/article_fc2aaa41-3888-5388-a36634ff7dd8bda5.html#:~:text=Approximately%20145%2C800%20people%2C%20or%2022,member%20per%20month%20is%20%2 4188.

73 D.C. Policy Center. 2018. Food Access in D.C. Retrieved on August 28, 2023 from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/01/Food-ACCESS-in-DC.pdf

74 DC Food Policy Council. 2022. Opportunities to strengthen nutrition programs in DC to address senior food insecurity. Retrieved on August 28, 2023 from https://dcfoodpolicycouncilorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/03/opportunities_strengthen_nutrition_programs_dc_senior_food_ins ecurity_fleurian_filkins_dcopfpd.pdf

75 DC Food Policy Council. 2022. Opportunities to strengthen nutrition programs in DC to address senior food insecurity. Retrieved on August 28, 2023 from https://dcfoodpolicycouncilorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/03/opportunities_strengthen_nutrition_programs_dc_senior_food_ins ecurity_fleurian_filkins_dcopfpd.pdf

76 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-years estimates. Table H1.

77 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table S2504

78 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table S2504

79 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table S2504

80 U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. American community survey 1-year estimates. Table S2504

81 Federal Reserve Economic Data. 2023. Homeownership rate for the District of Columbia. FRED. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DCHOWN

made up of apartment units. There are also racial-geographical constraints. Much of the singlefamily homes, often coveted for their ability to pass down generational wealth are located in wealthier areas of the District, which provides an advantage to white residents. D.C.’s Black home ownership has mostly stagnated in the early 2020s. Though the District has roughly double the Black population rate of the U.S. as a whole, Black home ownership has hovered around 20%.82

Although the District grew considerably during the 2010s, the pandemic caused several residents to move to the surrounding suburbs. While an exodus of individuals from an area typically decreases overall demand for housing, finding an affordable apartment in D.C. is as competitive as ever. The high demand for housing has incentivized some individuals to take advantage of the situation. In 2023, the D.C. attorney general warned against scammers posting fake apartments for rent and then charging individuals transaction fees.83 The rise is scammers is indicative of the current housing market instability that many residents of low-income face.

The competition surrounding the rental market creates intense pressure on the cost of housing in the District. A study conducted by the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that for a 2-bedroom apartment, renters would have to make near $40 an hour to make rent, for fair market rent.84 This is especially impactful for young families living in the District, who may require additional rooms for their family. The situation is even more dire for minimum wage workers, who at $17.50 an hour, would have to work 79 hours a week to afford a 1-bedroom apartment. For an individual making minimum wage working 40 hours a week, the fair market rent is an estimated $1,160. There are few, if any 1-bedroom apartments in the District at that price. In fact, for a studio apartment, annual income required to pay rent at the end of the month is $70,880, for a fair rent price.85

Unlike homeowners, renters do not receive tax breaks for entering a lease with a landlord. This puts further economic pressure on low-income, young populations who are more likely to rent after completing their education.

82 Hopkins, Paige. 2023. D.C.’s Black homeownership rates have stagnated. Axios. Retrieved on September 18, 2023 from https://www.axios.com/local/washington-dc/2023/01/12/dc-black-homeownership-rates-unchanged

83 Ianelli, Nick. (2023) Don’t be fooled by this scam if you’re renting in DC. WTOP. Retrieved from https://wtop.com/dc/2023/08/dont-be-fooled-by-this-scam-if-youre-renting-in-dc/ on 8/21/23.

84 National Low Income Housing Coalition. 2024. Out of reach District of Columbia. Retrieved on August 19, 2024 from https://nlihc.org/oor/state/dc

85 National Low Income Housing Coalition. 2024. Out of reach District of Columbia. Retrieved on August 19, 2024 from https://nlihc.org/oor/state/dc

As a rule of thumb, housing is considered “affordable” when 30% of take-home income is appropriated to an individual’s rent or mortgage. However, this rule is inherently regressive. Lower-income households dedicate a higher proportion of their income to rent than higherincome households, as higher-income households tend to have more expendable capital after paying rent or a mortgage. Despite this limitation, the rule is often accepted as at least a benchmark for affordability. If a household spends more than 30% of their income on rent, then the household is considered “cost burdened”.

Many residents within the District are considered cost burdened and even severely cost burdened (50% or more of take-home income is dedicated to rent). By the end of 2021, nearly 25% of renters were considered cost burdened.86 Even as the city provides services such as the Affordable Housing Locator and various forms of housing vouchers, rent continues to increase dramatically throughout the city. By 2023, the average rent for an apartment of 745 square feet was $2,327.87