15

19

20 A Peek into Perry CHS Classrooms

20 Vicki Ammer

20 Kenneth Smith

21 Jason Boll

21 Rachel Mackenzie

21 Maria Orton

22 A Peek into Westinghouse CHS

22 Angela Flango 22 V incent Werling 23 Sean Means

15

19

20 A Peek into Perry CHS Classrooms

20 Vicki Ammer

20 Kenneth Smith

21 Jason Boll

21 Rachel Mackenzie

21 Maria Orton

22 A Peek into Westinghouse CHS

22 Angela Flango 22 V incent Werling 23 Sean Means

■ BY ESOHE OSAI, P h D Assistant Professor, School of Education Director, Justice Scholars Institute

The year 2025 began with much uncertainty for educators, especially those of us dedicated to educational equity and improving the livelihoods of people in marginalized communities. Reflecting on the current socio-political climate in the U.S., I am reminded of how this moment connects to historical periods in our nation. Confucius said, “Study the past if you would define the future.” In navigating today’s educational landscape, I am drawn to Dr. Barbara Sizemore: a giant in Black history, a force of a woman, and an audacious education leader.

Barbara Sizemore was born in Chicago, IL, in 1940. I was born in Chicago in the 1980s, not far from where Barbara Sizemore began her career as an educator. By the time I came on the scene, Dr. Sizemore had moved to Pittsburgh from Washington D.C., after serving as the first Black woman superintendent to head a major city’s public school system. Despite a tumultuous experience in D.C., she came to Pittsburgh ready to roll up her sleeves and stay engaged in the effort to improve educational outcomes for Black children. Dr. Sizemore joined the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh School of Education and was known for her intense dedication to low-income communities that were home to much of Black Pittsburgh. She worked closely with local schools and organizations to combat challenges in Black schools, developing programs and

systems to ensure success for Black learners and to foster thriving Black communities. She was a leader in both the academy and the community – a true communityengaged scholar before that was even a popular designation.

Dr. Sizemore’s story is one of courageous leadership, sprinkled with humility, candor, and deep persistence. She had a profound belief in the potential for Black children to succeed and was unrelenting in her efforts to create meaningful change. As a researcher and thinker, she developed models that facilitated learning and engagement for the most disadvantaged children. She did not hesitate to confront powers and systems that threatened the livelihood and well-being of Black communities. She understood that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results that it gets,” so she tackled educational challenges with the force of her intellect. It did not matter who was at the helm; she faced opponents with grace and fortitude. She understood struggle. She never backed down from a challenge and was relentless in striving for equity and excellence in education.

Sizemore’s life speaks volumes of what is possible for Black children in our public school systems in the U.S. She was like a river in the desert, pouring her heart and soul into her convictions and what she believed

was possible. Dr. Sizemore once wrote, “We must teach our children to dream with their eyes open.” That is our assignment, despite the present challenges in education. We must continue to expose young people to what is possible. We also have to help them become critically conscious because that helps them make sense of what they see around them while dreaming. We cannot allow them to be limited by the versions of reality that are most proximal. We must give them the opportunity to dream—to engage in freedom dreaming. This dreaming, based on deep desires, can become future goals and aspirations. We can then provide the educational and community infrastructure to help those goals and aspirations become reality.

The Justice Scholars Institute is entering its 10th year of partnering with the Pittsburgh Public Schools (PPS) to help build that infrastructure. This foreword acknowledges that we owe a debt to Barbara Sizemore, who spent decades engaged in this kind of work and whose legacy, though underappreciated, speaks volumes. It took me moving to Pittsburgh to learn about Barbara Sizemore. Sadly, she was never mentioned in the schools I attended. However, I intend to make sure that the PPS students I encounter know her name. Her message to PPS students was likely similar to the one I often share: You’re brilliant, and you can do hard things. The struggle of life is real. But you’re built for it. Go forward and change the world

Westinghouse Academy is located in Homewood North, in Pittsburgh’s East End, in a majestic five-story building dating back to the 1920s. The majority Black community of Homewood holds some of the city’s richest cultural history, as well as a history of disinvestment and economic disadvantage. Boardedup houses sit across the street from the school. Flango, who also teaches 10th grade English, has been at Westinghouse since 2017. “We have a lot of really smart, capable, dedicated staff, and we have great students with a ton of potential but also students that experience a lot of challenges,” she says. For example, in the 2023-24 school year, 92% of students were economically disadvantaged, and 67% missed nearly a month of school or more. Westinghouse also had one of the highest student mobility rates—the percentage of students transferring in and out—of any district 6-12 or 9-12 school.

Justice Scholar Nadia Dixon, of Wilkinsburg, says Westinghouse “is not as bad as it’s portrayed on the Internet. It’s a very tight community, even though we have our ups and downs.” She believes a student can get a good education there. At the same time, she recognizes that she didn’t have the same opportunities as students at some other schools, for example, Pittsburgh Allderdice High School in Squirrel Hill. “’Dice has a lot of AP classes,” she says, referring to Advanced Placement, which offers students more challenging content

in high school and can allow them to skip more basic courses in college. Given her goal of being a lawyer, in 9th grade she would have taken AP US Government and Politics if it had been offered at Westinghouse, as it was at Allderdice. She did take a few AP classes, and the school is beginning to offer more, she says, but she wishes she’d had more options.

Jackie Spiezia, who serves as the research and evaluation coordinator for JSI and runs its OST program at Westinghouse, contrasts the college counseling she experienced with what Westinghouse students have reported. The Catholic high school she attended in New York City employed two counselors for its 60 students. Both were “incredibly involved in the process” of helping students prepare for college, she says, including holding FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) workshops and arranging for one-on-one meet-ups with college representatives. Westinghouse has three counselors, for about 660 students. “When I asked the students, who is the person that you feel supports you the most, the two names they gave were the names of their teachers,” Spiezia says. “And so I specifically asked, ‘What has your engagement been like with your guidance counselor?’ And a few students said they had not even spoken to their guidance counselor the entire year.”

In addition to AP, students at certain schools can take courses through Pitt’s nationally accredited, longrunning College in High School (CHS) program, which partners with schools across the state to offer college-

level courses at a reduced rate. In Pittsburgh, though, “They were never in schools that had populations like we serve,” Osai says. “Before we started at Westinghouse, there were zero credit-bearing opportunities in that building whereas at Allderdice there were a dozen or so classes offered. And that to me was not surprising but disappointing that people let that continue.”

Just like at Allderdice, there were students at Westinghouse who wanted to take college classes. “If we know that research says the students who have college courses in high school are more likely to succeed in college,” Osai asks, “then why not give them that chance? And we know that we had very low numbers of successful post-secondary graduation rates from [Westinghouse, Milliones, and Perry]. You have three percent, five percent, six percent some years who are finishing high school and actually six years later have a college degree. That’s not okay.”

She decided, “I’m going to make sure that those students have access to what they should have access to.”

One major existing resource was CHS, which agreed to partner with JSI; currently, it provides teacher training and collaborates in other ways. At the same time, Osai knew that simply bringing CHS courses to Westinghouse would not be enough. JSI would also have to offer the experiences, exposure, information, and “scaffolds” that help students get ready for college, the kind of multi-faceted support that students in schools with more resources often take for granted.

Once they’re settled, she asks them to chart the elements of their research papers and check off what they’ve completed. She tells them, “I want you to see how much you’ve done.”

After a beat, she says, “You’re tired.” They nod. “You’re thirsty.” They laugh. “It’s dark, and you’ve been running up and down….” More laughter. Shoulders drop, and a wave of relief passes over the class. She reviews what the rest of the semester will look like, and asks who is coming to the study session over break. She’ll be away at a conference for a few days, she reminds them. “Now they’ve got you leaving,” a student says, pretending to grumble. “What’s next?”

Flango divides the Argument class into two parts. In the first semester, she says, “We learn the different types of argument, researching and writing arguments as well as delivering them, how to respond to counter arguments. So it’s a lot of reading, writing, debating and presenting.” The second semester focuses on the research paper. Students undergo the scholarly process of “brainstorming their ideas, developing research questions, coming up with a working thesis, doing an annotated bibliography,” and ultimately creating and delivering a presentation. Westinghouse students who write research papers of at least 15 pages are eligible for a

$4,000 college scholarship funded by an anonymous donor. Despite that lure, Flango says that when she first started teaching Argument, “the buy-in was more difficult. The kids were all of a sudden being asked to grapple with a lot more rigorous material. And even though the support was there, it was like, why would I choose to do something more difficult if I can do something that’s easier? As the years have gone on and they’re able to see the upperclassmen do it, and then you see your friend do it the year before you, [the path] has become a lot smoother and a lot easier.”

Nadia’s topic was cultural appropriation versus cultural appreciation and their effects on four cultures. She researched how each group defines cultural appropriation, conducted interviews, and read widely on the Internet to avoid basing her conclusions on one “skewed” argument, she says. She learned, “A 15-page paper is not as hard as it seems because 15 pages is a lot, but after you do it, it’s like, I was stressing for nothing.” In the end, she wrote more than 15 pages, and so did many of her classmates.

“It’s not just rigor and sink-or-swim,” Flango says. “We give them support— very targeted, specific support—every step of the way.” The key is to “meet students where they are” and allow them the space to grow, which can involve more than helping them develop research skills. “If you start to lose confidence or start to doubt yourself, we want to be there. We want to be that safety net to say, let me show you why I know you can do this.”

Basic Applied Statistics (11th or 12th)

US History (11th)

Instroduction to Social Justice (12th)

Argument (12th)

Preparation for Biology (11th or 12th)

20th Centry African American Literature (11th)

US History (11th)

MILLIONES

African American History (11th)

Argument (11th)

Theories of Leadership (12th)

Introduction to Social Justice (12th)

Students who meet certain criteria are automatically enrolled in courses. Others can enroll with a teacher’s recommendation.

High expectations are paired with “specific, targeted” support designed to meet students where they are.

High expectations and student-driven, relevant topics boost attendance

“DID

Means says he tries to give his students a realistic view of their lives after high school. He wants them to have careers they can be passionate about that also pay well—no degrees in “underwater basket-weaving”—with the goal of having one job that will allow them to read to their children at night.

Each year, he wonders, “Did we do enough?” Just as he runs out of time in his classes, at graduation “we ran out of time again because there’s still things that you want for them.” Even so, one of the emotions that day is pride. “We did this for our children,” he says. Professionally, JSI has offered him a level of honesty and authenticity he hasn’t always

The “cohort model”—keeping students together for more than one year—promotes community, which has social and academic benefits.

Student participants shape OST (after-school time) according to their interests, and work on projects that can create meaningful change.

JSI staff and teachers regularly gather information about the support students and graduates need.

experienced. “Through the teachers that we’ve had, all the people on the Pitt end, and the students that we’ve had in the program, we’ve been able to build a culture in that space where people actually believe in what they’re saying.”

Nadia, who served as valedictorian for the Class of 2024, graduated with 12 Pitt credits she hoped to transfer to her chosen school, Howard University. With those classes behind her, she appreciates not having to take some of the general education classes, because “Who doesn’t want to be out of a gen-ed? No one.” Overall, being a Justice Scholar helped her develop confidence in her ability to do college-level work, and her classmates seemed to feel the same way. “The program helped

them realize college is not that hard,” she says.

Spiezia completed her first year as program coordinator at Westinghouse in June. She was happy to witness motivated students’ enthusiasm and excitement as their college offers and scholarships flowed in. She was even prouder of being part of other students’ evolution throughout the program, seeing them make a life-changing choice.

“Maybe they weren’t sure,” she says, “even—‘I don’t know if I want to go to college.’ And then, it’s like, ‘I didn’t apply to college yet.’ And then, it’s like, ‘Okay, I applied to college.’ ‘I got in.’ ‘Actually, I think I’m going to go.’”

Pittsburgh Milliones 6-12 University Preparatory School

Neighborhood school with a magnet entrance option, post-secondary focus; and Early Childhood Education and Entertainment Technology CTE programs

Enrollment 315 students District 6-12 average: 615

Current enrollment (October 2024): 280 students

Total Students in JSI of Juniors and Seniors currently enrolled in JSI

College in High School Courses

Graduation Rate 2023: 88%

Attending college or trade school immediately after graduation 2022: 38%

Completion of degree within 6 years: Class of 2018: 5%

Percentage of Black Teachers (2023-24): 21%

Percentage of Teachers new to school (2023-24): 3%

* Students with an Individual Education Plan (IEP) for special education, excluding students identified as “gifted”

9-12 neighborhood school with a Junior ROTC program; Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math Magnet programs; and Health Careers Technology and Cosmetology Career and Technical Education programs

Enrollment 428 students District 9-12 average: 799

* Students with an Individual Education Plan (IEP) for special education, excluding students identified as “gifted” District 9–12 average: 39%

76 28% 4 89% 29% 4% 14 % 3 %

Current enrollment (October 2024): 430 students

Total Students in JSI of Juniors and Seniors currently enrolled in JSI

College in High School Courses

Graduation Rate 2023: 89%

Attending college or trade school immediately after graduation 2023: 29%

Completion of degree within 6 years: Class of 2018: 4%

Percentage of Black Teachers (2023-24): 14%

Percentage of Teachers new to school (2023-24): 3%

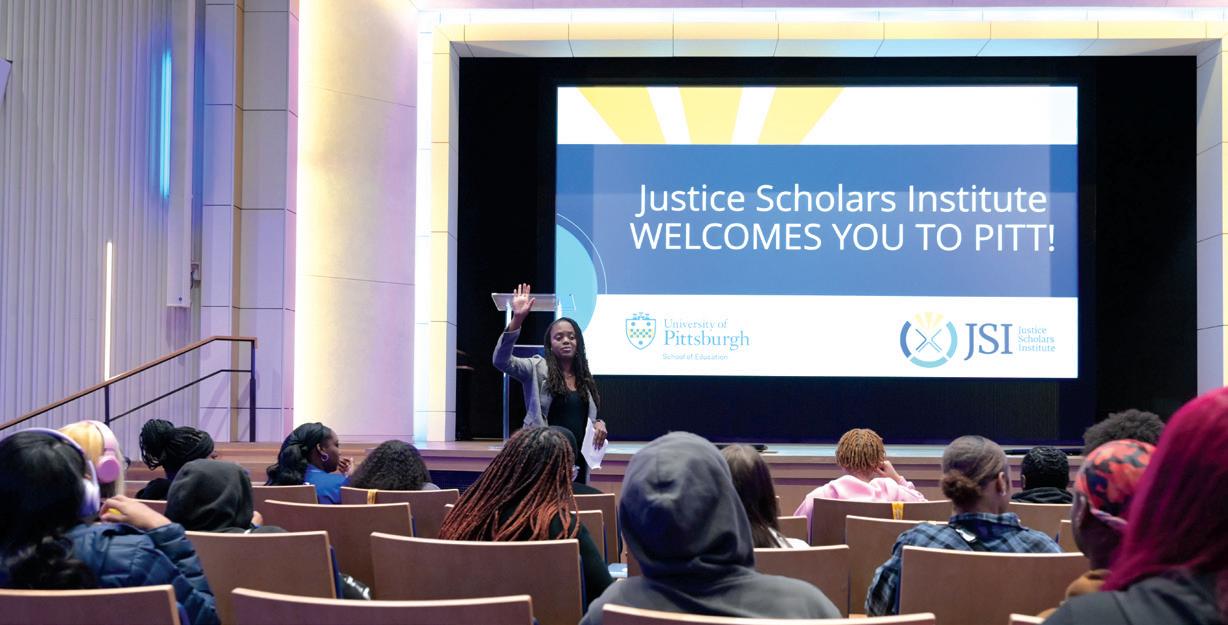

Throughout the school year, Justice Scholars Institute provides a host of educational enhancement opportunities, including college preparatory workshops and college visits. The workshops are intended to expose students to learning that will prepare them for the post-secondary transition. The college visits are vital to enhancing prospective students’ college selection experience. We often partner with The Pittsburgh Promise for college visits, which allows both organizations to expand our reach. JSI events are a great way for these students to immerse themselves in the full college experience and build skills that will be essential to them once they are enrolled in college.

Enrollment Day is the day that the students initially meet the JSI team and officially enroll in College in High School courses. We share all about JSI and explain why dual enrollment is important. We also share the program expectations and answer any questions students might have about their involvement. Students sign an agreement committing to the program expectations. Finally, we assist, as necessary, with registration for the relevant College in High School courses being offered at their school.

The JSI College Ready Workshop was held at Alumni Hall on Pitt’s campus. Juniors from across all three of our program schools attend the event. The students were greeted by the Roc (Pitt mascot) and Pitt Cheerleaders! After a welcome from our team, students engaged in a presentation by the Pitt Study Lab on Study Skills and Test Taking Strategies. Students took notes, dialogued with the presenters, and asked great questions. This was JSI’s first official partnership with the Pitt Study Lab and we look forward to working with them more in the future.

After the presentation, students went on a tour of the University of Pittsburgh. For most students in our program, this is their first official tour of Pitt’s campus. The tour ended at the Pitt Eatery where students ate lunch with other college students. After lunch, we finished the day with hands-on learning activities. Pitt is about a lot more than just classes. We wanted to expose our students to a few of the numerous activities, labs, and resources available on a college campus. Students were divided into three groups. One group went to the Bio Lab and participated in a lab exercise called “Searching for Biofuel Enzymes”. The second group went to the Open Lab where they learned about 3D printing and made their own buttons. The third group went to the Center for Creativity and made their own journals by book binding. Each of the three experiences was unique and enjoyable. Students left after a full day of diverse experiences on campus that gave them a glimpse into what college look like.

3 4

Each year, one of our primary goals is to take seniors and juniors in our program on a college visit. We typically take seniors on a visit in the fall and juniors in the spring. On October 1, 2024, we took 40 seniors from across all three of our program schools to Slippery Rock University. Students attended an information session, had a tour of the campus, and were able to eat in the cafeteria with other college students. We finished our visit by connecting with former JSI students. We met up with Elijah Warren a 2024 graduate of University Prep/Milliones and current freshman at Slippery Rock University and Amari Richardson a 2021 graduate of Westinghouse and a current senior at Slippery Rock University. We even brought both students a care package to help them make it through their fall semester!

5

College Night and Holiday Party is another wonderful collaborative event! We usually partner with the Pittsburgh Promise to host the festivities. JSI students and their families are invited to attend, along with our JSI teachers who usually show up for the fun. Citizens Bank also partnered with us this year and provided students and families with Financial Aid and FAFSA information. Importantly, we shared a holiday meal catered by a local business. Six colleges and universities set up tables to share materials and talk to students and their families. We raffled off prizes and gift cards to all in attendance.

The Personal Statement Workshop is a collaboration between the Educational Outreach Center and the Pitt Writing Lab. We work together to provide seniors from across our three program schools with the knowledge and skills needed to craft a compelling college application essay and/or scholarship essay. This allows our students to effectively showcase their personality, experiences, and goals to admissions officers, ultimately increasing their chances of college acceptance.

6

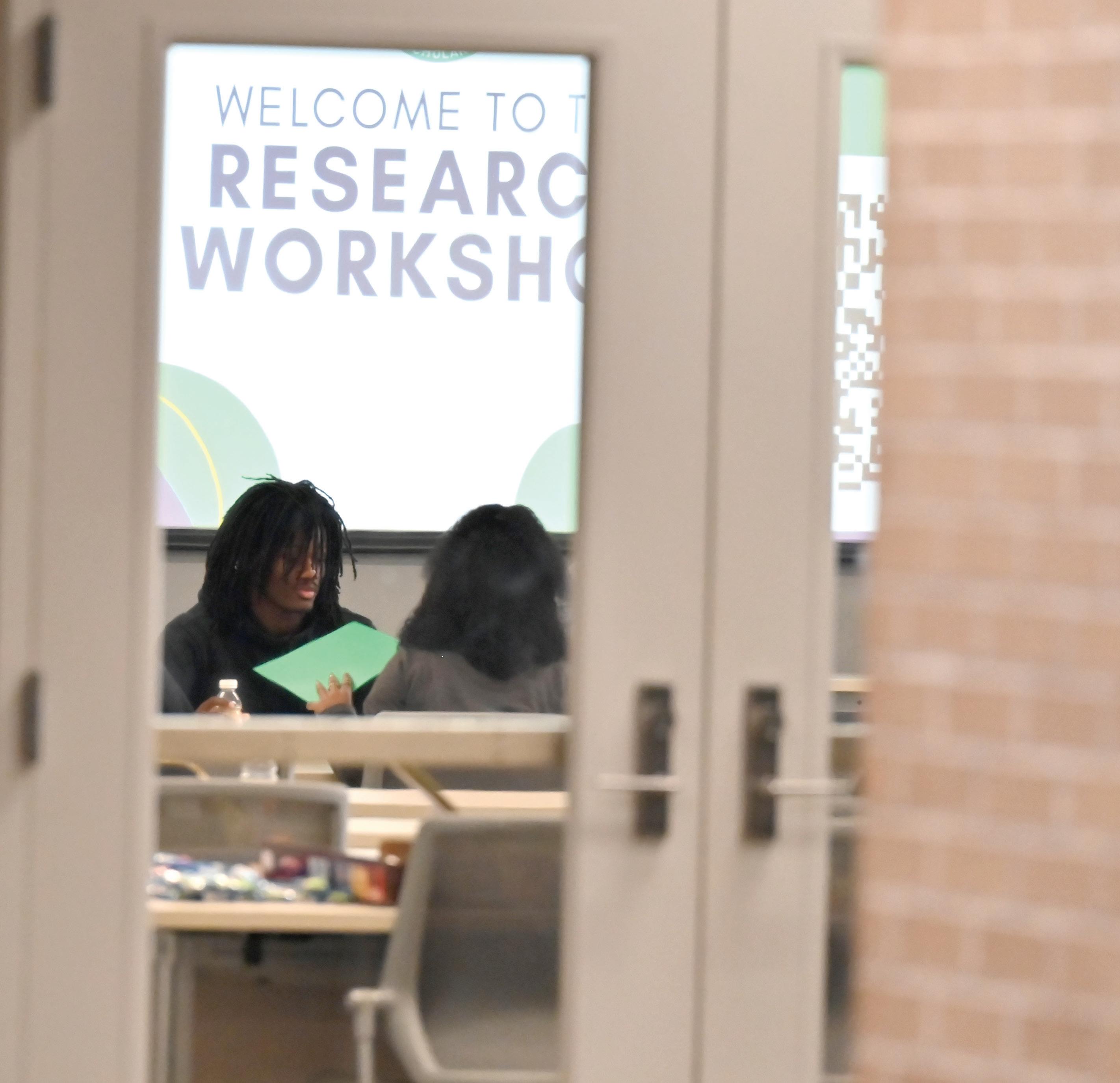

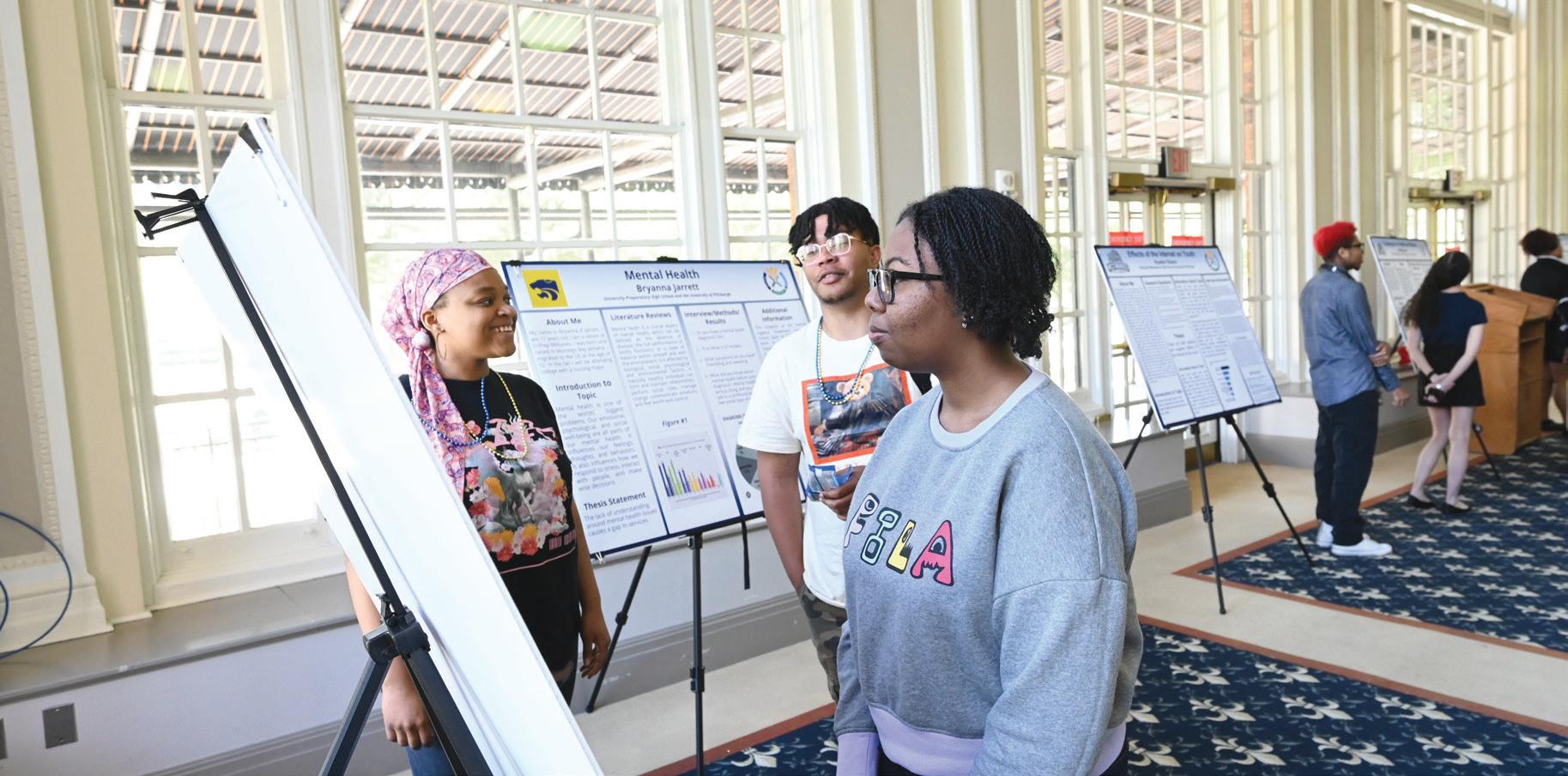

Our JSI seniors were invited to the Research Workshop to learn firsthand about the research process, discover innovative research methods, and get inspired to write their research papers. Each senior in JSI does a research project as part of their College in High School class. The paper is converted into a poster and presented at our JSI Symposium & Celebration in May. This celebration gives our students the opportunity to showcase their work to their families, Pitt faculty, Pitt staff and the larger community. The Research Workshop is coordinated in partnership with the University of Pittsburgh Hillman librarians and Dr. Khirsten Scott, a faculty member in the Pitt School of Education.

How did you get connected to JSI and what led you to get involved with the program?

I got connected to JSI through my high school (Perry) and they came in and introduced us to workshop opportunities! I attended a paid workshop with JSI that same summer leading into my senior year.

How did you benefit from your time working with JSI?

Working with JSI has been very beneficial for me as I worked with them in high school leading up to college, and I now go to Pitt, where they are located. So I have a very helpful and insightful network of individuals that have helped me a lot along my college journey so far.

What is something that you learned through working with JSI? How might that impact you moving forward into your career?

JSI helped me prepare for my transition to college from high school and has helped me out throughout my time here at Pitt. The habits and skills I learned through my summer workshop with JSI like study skills and plans of action, expected experiences, and normal plausible reactions to those experiences have helped keep me on track and focused.

What do you feel was your most significant contribution to the program? Encouraging the kids at my school to participate in JSI and take from the opportunities given to them.

How did you get connected to JSI and what led you to get involved with the program?

I was connected to JSI through a program within my school. This program allowed me to take college courses and participate in many events outside of school. What led me to be involved in JSI was the countless opportunities that the program provides that help with success in college.

How did you benefit from your time working with JSI?

The JSI program came with many benefits. The two major benefits, I would say, were, firstly, that it helped prepare me for college and, secondly, that it gave me many opportunities to explore Pennsylvania colleges that I was thinking of going to. JSI ultimately helped me pick the University of Pittsburgh with its numerous school tours and Pitt events.

What is something that you learned through working with JSI? How might that impact you moving forward into your career?

Something I learned through JSI is not to be afraid to ask for anything. JSI provides a lot of friendly people to help you on your college journey. Throughout high school, I had many JSI members help me be where I am now. Being able to ask for help when you need it is a big part of college. Everyone struggles in some sort of way in college, so being able to ask for help when needed is huge.

What do you feel was your most significant contribution to the program?

I believe my most significant contribution to the program was showing that the program does help prepare students for college. I am on my way to starting my second year in college and I can thank JSI a lot for that.

RISE Summer Program Sets Stage for College Success

How August Wilson’s archive came home to the University of Pittsburgh

For some Black families in Pittsburgh, finding the right school means choosing between diversity and academic rigor

WTAE Teacher of the Month: Mr. Means, Pittsburgh Public Schools

Tenth Anniversary of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Education Award in Partnership with Schools That Can

Pittsburgh students take part in Justice Scholars Institute symposium

My favorite Intro to Social Justice lesson is the Human Rights Market. In this exercise, we begin by brainstorming the basic needs of humans and compiling our ideas on the board. Then, I share an article on contemporary human rights issues—this year’s piece focused on the conflict in the Congo—to set the context for our discussion.

After reading, students receive a list of 16 human rights and are asked to rank them from most important to least. This task challenges them to distinguish between rights that may seem trivial and those that are essential to everyday life. Next, the class is divided into two groups: Buyers and Owners. The Buyers, who outnumber the Owners roughly five to one, learn that the Owners have “human rights” for sale and are competing to earn the most income from these sales. With a budget of $1000, Buyers must purchase their top four rights, while Owners can charge up to $500 for each right. After a few minutes of creating makeshift signs, the market opens. I love this lesson because it forces students to confront the reality that access to human rights is not universal. Wealth, geography, religion, and government influence those who enjoy these rights. At the end of the activity, Buyers reflect on what life would be like if they were limited to only the four rights they managed to acquire. At the same time, Owners discuss their pricing strategies and how competition affects their empathy toward Buyers. This simulation not only cultivates critical thinking but also personalizes the concept of human rights, prompting students to appreciate and question the value of rights that many of us take for granted.

I always have a plan and goal when teaching my Argument class. However, while having a road map is handy, it is often when one goes off-road and explores their environment to provide an opportunity to know and learn something new. This is the second year that I have taught this College in High School class through the support of the Justice Scholar Institute. Last year was full of many learning opportunities for me (read failed lessons).

This year, I have taken a different approach, having a clear agenda but always listening and looking for student feedback to improve learning. While introducing causal arguments, I became frustrated with the lack of student engagement and turned it over to the students what would make this class more relevant and encourage them to learn. Many ideas came fast and furious, and it was decided that we would present causal arguments that mattered to students: the term “strong Black woman” is more detrimental than helpful, having age restrictions to public spaces for teens under 18 is causing many problems, and America was born out of violence and has caused issues ever since. While this lesson is still in its infancy, I see possibilities abound. Problems have been identified, and the next step is to address them within our community, leading to our next subject: proposals. What to do to change the problem?

Having the structure to guide and the freedom to explore issues that matter have been a way to teach new skills through student-led voice.

One of the highlights of Theories of Leadership is our Leadership Magazine project. After being introduced to various styles and models of leadership, students think of a leader they like or about whom they want to know more. The person can be contemporary or historical, real or fictional/ mythological. Students research the leader’s background and describe the person’s leadership style, noting any highlights or challenges that influence their trajectory. Students then design a two-page magazine spread presenting information about the leader they researched. They are encouraged to be creative in their design while also making sure to include the most relevant aspects of their research that support their description of their subject’s leadership journey. Their research is expected to follow conventions of essay writing, including a formatted reference list. The finished product compiles the student pages into a magazine that is able to be shared at community events and within the school.

One of my favorite lessons to teach is cell signaling, a fascinating yet complex process that explains how cells communicate and respond to their environment. To make this concept more accessible, I break it down into a five-step timeline that ultimately leads to a change in gene expression. This structured approach gives students a solid foundation before exploring variations that can lead to different biological outcomes. To enhance relevance, I connect the lesson to real-world scenarios that students may have experienced or observed, such as diabetes, the fight-or-flight response, and sickle cell disease. For instance, when discussing diabetes, students analyze how insulin signaling regulates glucose uptake and what happens when the pathway malfunctions. In the fight-or-flight response, they explore how adrenaline triggers a cascade of cellular reactions, increasing heart rate and energy production. With sickle cell disease, students examine how a single genetic mutation disrupts hemoglobin structure, leading to altered cell signaling and the disease’s symptoms.

I incorporate case studies, discussions, and interactive simulations to deepen engagement. Students apply their knowledge by diagnosing conditions, predicting outcomes of pathway disruptions, and even modeling signal transduction using visual and hands-on activities. These elements challenge students to think critically and make real-world connections, reinforcing scientific rigor and relevance.

By the end of the lesson, students gain a deeper appreciation of how cell signaling governs essential biological processes. More importantly, they see the direct impact of these pathways on health and disease, transforming an abstract concept into something meaningful, applicable, and thought-provoking.

The following quotes reflect the 5 Pillars of Historically Marginalized People I use to prepare, teach, and learn from and with my students. Their function is to create hooks for students to link past historical situations to current events.

Quote 1 ~

”Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” attributed to philosopher George Santayana.

Quote 2 ~” …

My concern about not remembering (the past) is NOT that we will REPEAT it.

My concern … my fear is that we will CONTINUE the past. We will continue to do thethings that created inequality and injustice in the first place. So, we must disrupt the continuum of hard history, and we can do this by seeking truth; by confronting hard history directly by magnifying hard history for all the world to see. We can do this by speaking the truth and teaching hard history to our students. To do anything else is to commit educational malpractice.

Hasan Kwame Jeffries |Professor of History at Ohio State University

The 5 Pillars of Historically Marginalized People (HMP) help students confront what Jeffries calls “hard history”: the good, the bad, and the ugly of American History. The Pillars bring different lenses to history that start and end with TRUTH. This pillar helps reveal honest stories through various perspectives instead of nostalgic storytelling. Truth examines the paradox of American history between prioritizing principles and actions that maintain social, economic, and political power over others. The remaining pillars shed light on this substantial contradiction regarding principles, policies, and actions the United States took against HMP. They are OPPRESSION – through forms of segregation, discrimination & violence toward HMP to maintain paternalism, White supremacy, and other forms of domination over HMP; RESISTANCE from HMP against oppression to achieve justice, equitable opportunities, and protection to maintain basic human rights; RESILIENCE through persistence and fighting through renewed forms of oppression; RESOLUTION or goals that mirror complete freedom or partial positive outcomes that fuel HOPE. Thus, an honest examination using these pillars equips students to prepare for the cyclical nature of U.S. History, linking past events to the present. Hopefully, as new forms of oppression take shape, newer forms of resistance may also evolve toward achieving a more perfect union.

Student choice is key to cultural relevance and student engagement: choosing what you are doing naturally makes you want to do it more. The second semester of the Argument course is rooted in student choice as the springboard for the challenging and rigorous process of writing a 15-page research paper. Any research topic goes, as long as it has a social justice angle. From the detrimental effects of catfishing to the mental health of athletes to inequities within the criminal justice system, the student topics are rooted in their interests and advocacy, issues they see in the world that need attention, awareness, and solutions. The writing process spans several months and while rigorous, it is highly supportive, broken down into each step necessary to write a high-quality paper. It’s not just about the product. The process along the way is where the learning happens. From learning to find and read scholarly sources to creating an annotated bibliography and writing multiple drafts, the students are challenged and supported every step of the way. A culmination of passion, hard work, and academic skills, the research papers are the true epitome of students exemplifying being a Justice Scholar.

My Statistics lesson that engages students is one I borrowed from another curriculum. At the beginning of our study of binomial random variables, we came across the story of Darius Washington. Darius was a point guard for the Memphis Tigers during their 2005 playoff run. He was playing in the Conference USA championship game and was fouled while taking a 3-point shot with no time left, and his team was down two points.

The question the lesson tries to answer is whether it is wise to foul a player at the end of a basketball game. When we begin the lesson, the class maps out how Darius could win, lose, or tie the game with his three shots. Students are then given Darius’s accuracy when shooting from the line. Students then calculate the probability of win, lose, or tie. We continue to follow the game via video and recalculate these probabilities as Darius makes or misses his shots.

Once the game’s outcome is decided and Memphis loses, we are given Darius’s 3-point shooting accuracy. We take this new knowledge along with the previously calculated probabilities of winning or tying and compare it to the 3-point probability. It’s a great lesson that engages both me as a teacher and all my students.

I use a variety of engaging methods to support learning in my classroom. We begin by examining how Hitler gained power and relate this to the use of fascism and dictatorships in other parts of the world. Next, we step on The Magic School bus and land in the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Students read a condensed biography of Jessie Owens. Next, they’re instructed to write and argue why he should or shouldn’t have participated in the athletic protest during the games. At the end, we run the 100mm race (outside or in the hallway), and I dress up in my Olympic gear, and we even use a candle lighter as a torch. I’m losing by a wider margin each successive year.

We then turn to maps, where students examine how The Blitz occurred, and which nations were taken over when and how. We’ll look at appeasement strategies and why such a policy failed then and now. We conclude the takeover of Europe by watching the first few minutes of Dunkirk and modeling

Operation Dynamo using a rolling laundry basket (we also use this when flying in P-51 with and watching Red Tails during our after-school Dinner and a Movie).

After the Battle of Berlin, students read multiple articles on the Tuskegee Airmen. They’ll create flashcards on the airmen and continue with those cards throughout the different chapters of the war; they will work in pairs, asking one another questions based on their research using the notecards. By quizzing multiple peers, they will make different connections and understand the context from various viewpoints.

Towards the end of the unit, I’ll show students a video I made in Normandy, France, where I created a video tutorial of the battlefield in addition to providing focused readings and engaging prompts on Stalingrad, 761st Tank Battalion, the Holocaust, the Pacific Campaign, and the Manhattan Project.

Over the past three years, our JSI Teacher Collective has focused on a Problem of Practice, which states: Inequitable post-secondary pathways exist for students in our schools, particularly for Black students in the Pittsburgh Public Schools District. In exploring this issue, we narrowed in on four areas that are implicated in the problem:

Our Practice

Our Students’ Lives

Our Schools

Our District

In previous school years, we engaged JSI students, district leaders, principals, and community members to help us make sense of the dynamics in all four areas. This year, our collective has narrowed in on Our Practice, where we have the most direct impact. The goal was to create an evaluation tool that would serve two purposes: 1) Help us create a frame for the types of CHS classrooms that are most effective in JSI-partnered schools and 2) Assist us with an internal assessment within our community of practice.

Dr. Carmen Thomas-Browne is supporting the development of the JSI Classroom Observation Framework. The Classroom Observation Framework aims to ensure alignment across courses while maintaining a commitment to preparing students to be social justice advocates with the necessary skills to succeed in their post-secondary pathways. The framework contains four domains: Planning and Preparation, Learning Environment, Teaching & Learning, and Professional Engagement. The Framework aligns with the state of Pennsylvania Teacher’s Framework for Observation and the Cultural Awareness Competencies of the Pennsylvania Department of Education Common Ground Framework. The tool provides a structured approach to assessing and enhancing instructional practices. It uses a reference for college-level course rigor since students will gain college credit upon successful completion of the courses.

Dr. Carmen Thomas-Browne has joined our team as a Justice Scholar’s Institute consultant. She is a seasoned educator with over 25 years in the field. She was formerly a Comprehensive School Improvement Math Specialist working on the Regional Improvement Team for the State of Pennsylvania. She came to this work from the University of Pittsburgh, where she was a Math Test Development Manager on the Pennsylvania Alternate System of Assessment (PASA) Project. She has supervised numerous preservice teachers in their student teaching experiences. She was the lead author in the development of an instrument titled, Assessment of Beliefs and Practices of Teaching Mathematics to AfricanAmerican Students, which was used on the Designing for Equity by Thinking in and about Mathematics (DEbT-M) project as a tool for teachers to reflect on their beliefs that inform the quality of their teaching and classroom practices. An article on this instrument was published in the journal Urban Education. She also wrote a book chapter on teaching mathematics for social justice that was published by the Association for Educational and Communication Technology. She brings the flavor of a seasoned educator, mathematics instructor, and native Pittsburgher to our team.

I interned with the Justice Scholars Institute (JSI) in my senior year at Pitt. My major, Applied Developmental Psychology, required me to work part-time with children and youth in Pittsburgh. I remember not having anything specific I was looking for in an internship. One day, my advisor sent me an internship posting with JSI. I had a couple of experiences working with youth already, and I saw this internship as an opportunity to capitalize on that. I also had professional goals of working within schools after graduation. Therefore, I saw JSI as the perfect chance to combine my personal and vocational interests. I did many things at JSI, from supporting workshops, chaperoning college trips, checking in on past students from the program, helping students complete college applications, editing scholarship essays, sitting in on dual enrollment classes, and participating in the program’s monthly Teacher Collectives meeting. My favorite part about all of these things was getting to know the students in the program and witnessing their progress throughout the year. It was rewarding seeing all the hard work they put in, and it paid off as many of our students received multiple college acceptance letters. And for those who did not choose the path of a college education, it was exciting to see that they

My experience as an intern with the Justice Scholars Institute was nothing short of amazing. I was able to watch students learn and grow in their JSI courses. It was inspiring to see our students connect what they were learning in class to local history and their firsthand experiences within their communities. The trips we took to various colleges, universities, and local organizations allowed students to explore their options, passions, and make plans for their futures. Not only were these trips insightful for students during their college/career planning

had set goals for their futures. At the end of the experience, I had the pleasure of attending graduations for Perry and Westinghouse of which our students held positions as both salutatorian and valedictorian. This is a testament of the hard work of JSI students and also the staff and teachers as we help to challenge them academically while supporting their growth as students and people.

I credit the amazing time I had during my internship with JSI to the staff, namely, Erica Roberts, Kaleah Malloy, Jackie Spieza, Dr. Esohe Osai, Kelcey Rounsville, and, my fellow intern, Molly Tiplady. I always looked forward to our frequent meetings throughout the week. Even the more dull gaps of time spent driving to and from schools, traveling to colleges, setting up for programs, and the lulls between workshop sessions were made fun. Throughout the year, the JSI team was supportive and accommodating of my busy schedule which I appreciate. I keep regular contact with all these individuals and even continue to support their work after the end of my internship. Although the experience only lasted a year, I will never forget the time I spent at JSI and the connections I made along the way.

process, but the students never failed to make the trips enjoyable and have us laughing all day. Working side by side with JSI teachers was truly an invaluable experience for me. Seeing school staff members learn, adapt, and advocate for their students the way the JSI teachers did was extremely influential for me regarding my own career goals and aspirations. The way the Justice Scholars Institute highlighted the importance of community, educational equity, and social justice made it the most memorable and impactful educational experience for me.

JSI Lifers: Interviews with two Pitt graduates who spent four years volunteering with the

Mary McMahon worked with JSI throughout her time as an undergraduate student at Pitt. She volunteered with the schools weekly to provide peer and academic support. She also worked with Dr. Osai on a research project by interviewing past JSI students who had graduated. Mary is now at Columbia University working to get her Master’s degree in Social Organizational Psychology.

What program theme stood out to you as most impactful through mentoring with the JSI?

A big theme of the program is being able to see yourself in postsecondary education [and seeing all of the] opportunities that are out there. Bringing [JSI students] to Pitt’s campus … was where I saw the most transformative experience for them.

What was your biggest takeaway from working with JSI?

Listening. I learned way more from [JSI students] than I honestly think students learned from me. There are so many ways to listen to students, which is especially important in high school because it can be a hard time overall.

What did you learn from the interviews you completed with JSI graduates?

Personal development is what stuck out throughout the interviews. Even after moving on to college, students could talk about how their experiences shaped them as a person. The program definitely has a long-lasting effect on the students.

What did you gain from interning with JSI?

I learned a lot about how you engage in the community and how you talk about students in general. I engaged in conversations that were uncomfortable in a good way. When volunteering, you learn so much about your [own] perspective.

What was your biggest takeaway from working with JSI?

Two things come to mind. The first is they gave me a sense of autonomy and power towards how I spend my time and how I can contribute. Being a business major working with the School of Education, I would sit in a room full of people who have two to three degrees on me. I was young and I had not even an undergraduate degree. I never once felt like I didn’t have the power to contribute. It gave me a lot of like sense of purpose and confidence in the

workplace professionally. The second thing I most benefited from was the exposure I got. I grew up in a very isolated community in Massachusetts. When I moved to Pittsburgh, I would say in higher education, nothing really changed about that. I think JSI was a big place where I was able to engage in conversations of topics and people of different socioeconomic statuses, upbringing and beliefs, engage in conversations that made a real difference.”

What have you learned through JSI that you will carry with you throughout your future career?

I learned that it is important to have a multidisciplinary approach to every job and every project I work on. Different ages, different perspectives, different career paths. I think JSI was a big wake-up to the fact that you gain so much more from having people working on the same project who have very different backgrounds”

Based in the University of Pittsburgh School of Education, the Justice Scholars Institute is a college preparation and academic enrichment program for high school students in Pittsburgh Public Schools. Our goal is to prepare young people to be advocates for change and social justice. Please support our efforts by clicking the QR code to the right to make a donation today.

Back row, left to right:

Jackie Spiezia, research and evaluation coordinator

Jason Boll, partner teacher

Rachel Mackenzie, partner teacher

Bilal Abbey, partner teacher

Erica Roberts, program manager

Maria Orton, partner teacher

Angela Flango, partner teacher

Esohe Osai, founder and director

Sean Means, partner teacher

Kaleah Malloy, program coordinator

Front row, left to right:

Brian Wagner, partner teacher

Kenneth Smith, partner teacher

Carmen Thomas-Browne, community partner

Vicki Ammer, partner teacher,

Ashley Capps, partner teachers

University of Pittsburgh

College in High School Program

Office of the Chancellor

Office of Engagement and Community Affairs

Office of the Provost

University Educational Outreach Center

School of Education

School of Social Work

University Library System

School and Community Partners

A+ Schools

Catapult Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh Public School District

Pittsburgh Milliones

Pittsburgh Perry

Pittsburgh Westinghouse

The Pittsburgh Promise

Pittsburgh Public School District Leaders

Special Thanks to Our Philanthropic Supporters

Hillman Family Foundations

The Pittsburgh Foundation