THE CITY OF THE PAST TO ENSURE THE FUTURE:

Material Upcycling and Adaptive Reuse Practices in Malmö’s Western Harbour

Svea Anstis, Robert Duncan

Sebastian Amaya Segura

Fig. 1: Map of Case Study Areas within the Western Harbour in Malmö, Sweden

Fig. 1: Map of Case Study Areas within the Western Harbour in Malmö, Sweden

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. Timeline

3. Background

3.1 Case Study: Bo01

3.2 Case Study: Varvsstaden

3.3 Policy Evolution: Miljöbyggnad

4. Conceptual Framework

4.1 Sustainable Development

4.2 Circular Economy

4.3 Neoliberal Planning Principles

4.4 Brandscapes

5. Methods

5.1 Observations and Film

5.2 Film

5.3 Interviews

5.6 Document Analysis

6. Informants

6.1 Taleen Josefsson

6.2 Jan Dankmeyer

6.3 Eva Dahlman

6.4 Hanne Birk

7. Findings and Results

7.1 Bo01

7.2 Varvsstaden

8. Conclusion 9. Glossary of Terms

References

Image

1 2 3 3 5 6 7 7 8 9 10 11 11 12 13 16

11.

Index 14 14 14 15 15 17 17 21 25 27 28 30

10.

INTRODUCTION

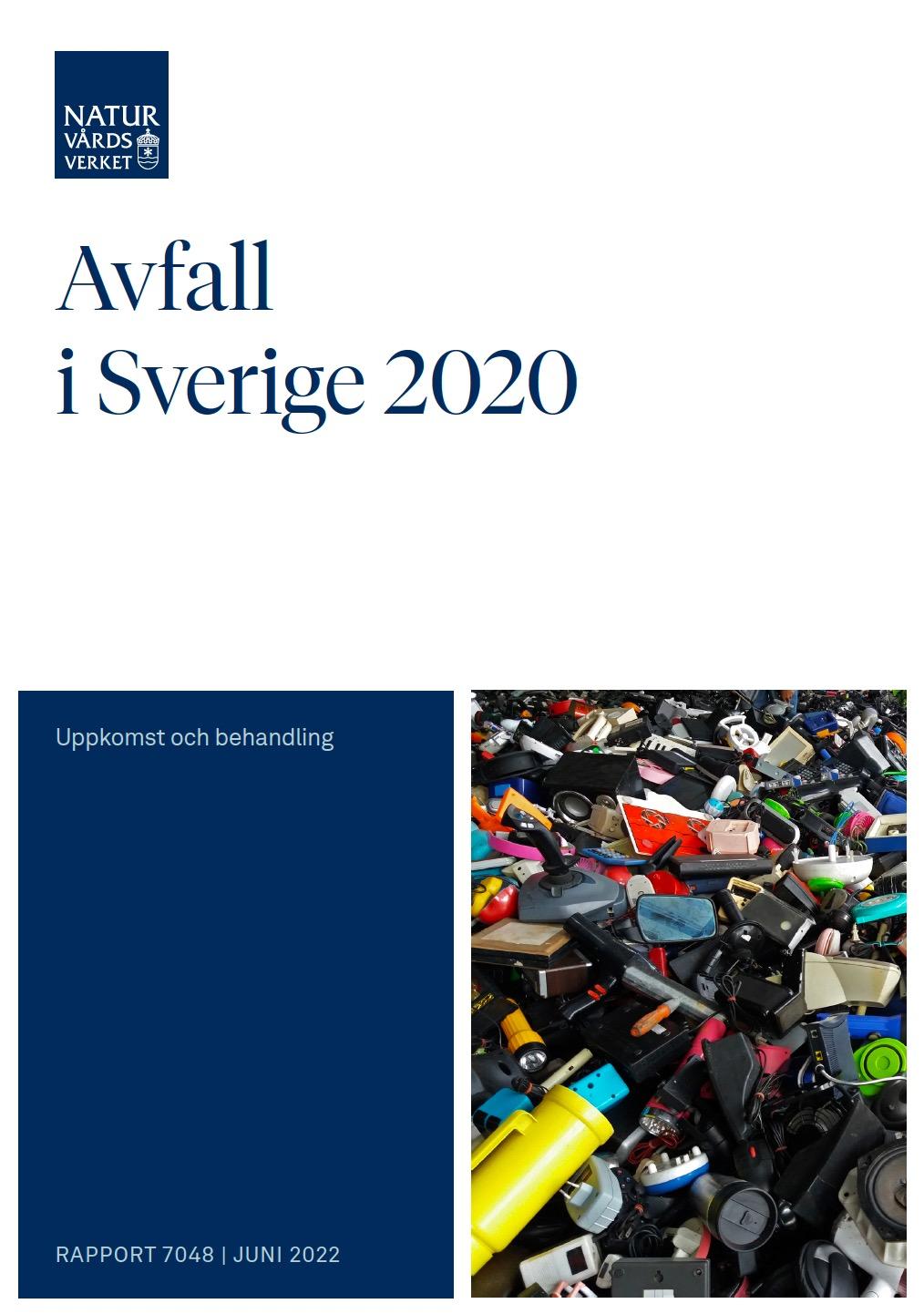

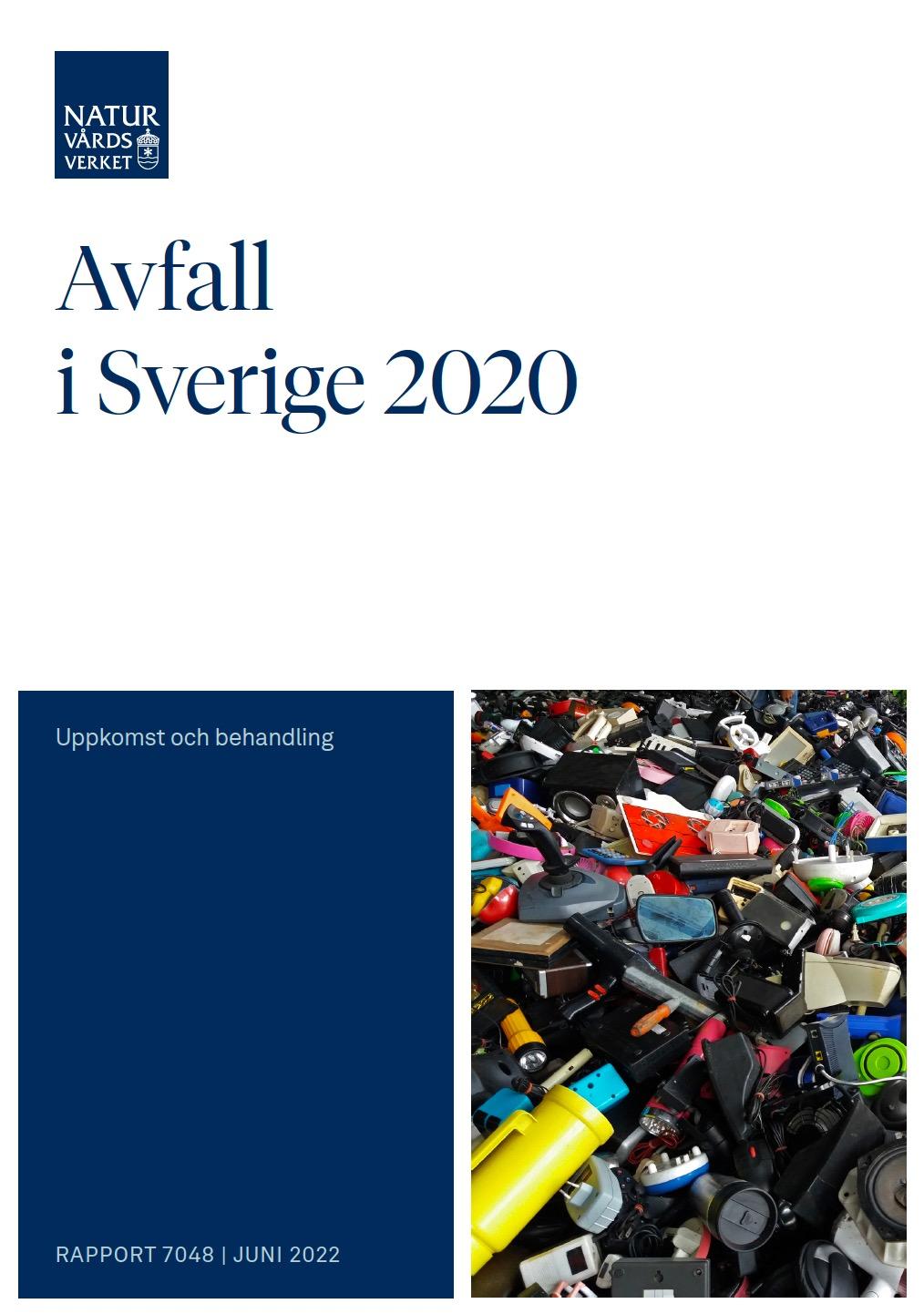

The global construction industry, while crucial for societal development, harbours significant environmental implications, posing challenges for sustainable growth. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), construction activities contributed to 37% of global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2022 (UN Environment Programme). The cycle of raw material use and waste production as it has continued up until today is simply not sustainable. However, there is a growing trend of material upcycling and reuse practices seen within the construction industry. Upcycling may be more familiar in terms of clothing and fashion design but has been a part of building construction as far back as the Roman Empire where the “[...]reused remains of earlier imperial monuments'' (Alchermes, 1994,) known as spolia, can be seen adorning buildings from the time. In more local contexts, 14.2 million tons of waste was generated by the Swedish construction industry in 2020 (Naturvårdsverket Rapport 7048, Avfall i Sverige 2020, p. 8). Of this 14.2 million tons of waste produced, a hopeful 4.4 million tons was used as functional construction materials (Naturvårdsverket Rapport 7048, Avfall i Sverige 2020, p. 33). As the industry continues to tackle material demands, reuse and upcycling practices are gaining traction. If you take a stroll into Malmö’s Western Harbour you may notice a significant portion of the old industrial area currently in flux. A number of the historical brick buildings stand in various stages of renovation, looming and idle with broken windows and cracked stones or draped with tarps and surrounded by an exoskeleton of scaffolding. Many however gleam proudly, amalgamations of past and present material given new life. Small details here and there preserve the industrial identity of the area, like public seating made from hefty steel beams and border walls cobbled together from old bricks. Sit for a moment on one of these neatly crafted benches and ponder the mass of material making up each building: bricks, glass, steel, wood, concrete. Where does it all go when a building has served its purpose?

This project aims to address the material reuse and upcycling trend as it has developed in the city of Malmö, Sweden through the analysis of two different areas in Malmö’s Western Harbour. The two areas we intend to look at are Bo01 and Varvsstaden. Bo01 is an architectural exhibition manifested in the area of the Western Harbour in Malmö between May and September 2001. Bo01 represents a time in Malmö’s history where the city intended to forget its industrial past and embrace a new age of green energy, technology and harmony with nature.

Varvsstaden, which translates to “the shipyard city”, encompasses a historical industrial sector of the harbour which is currently being revitalised by the private company Varvsstaden AB. In contrast to Bo01’s sleek technology-based conception, Varvsstaden seeks to maintain the history and identity of the area through the preservation and integration of historical buildings using upcycling and material reuse strategies.

These two case studies represent an evolutionary timeline of how sustainable construction has developed over the years in the area. It should be kept in mind however that this timeline is not mutually exclusive and should be thought of as more of a sliding scale. In examining these areas two questions arise:

1. To what extent do green building practices, upcycling, and adaptive reuse initiatives contribute to sustainable building construction in Malmö’s Western Harbour development projects?

2. How have perspectives and approaches towards sustainable building construction changed throughout the development of the Western Harbour in Malmö?

The final goal of the study is to present a written analysis and visual timeline of the evolution and discourse surrounding sustainable building practices in Malmö’s Western Harbour.

1

Late 1990’s

Environmental Programs

Construction began at Hammarby Sjöstad which influenced the creation of the environmental program for Bo01.

New City Image

Neoliberal planning principles take hold in Malmö’s newest developments seeking to attract a new class of resident.

Housing exhibition in the Western Harbour, focusing on green building technologies and the inclusion of green spaces.

Reuse and Upcycling Practices

Miljöbyggnad 4.0 begins incorporating adaptive reuse and upcycling practices as indicators in the manual.

Miljöbyggnad 2.0 begins to guide urban developments in Sweden towards sustainable building practices.

Evolving Environmental Policies

Adaptive reuse and upcycling practices are realized in Malmö’s Western Harbour in consultation with Danish firm Lendager Group.

Bo01

Varvsstaden

Present 2 TIMELINE

BACKGROUND CASE STUDY: Bo01

Bo01 was an architectural exhibition that was manifested in Malmö’s Western Harbour between May and September 2001 with a theme name “The city of the future in the ecologically sustainable society of information and welfare. ” The area was built as a new city district, with buildings designed by several high-profile architects (Malmö Stad, 2024). The exhibition was partly financed by the Swedish LIP (Lokala investeringsprogram) program, which was a state-funded economic support being shared amongst 161 municipalities between the years 1998 and 2003. The purpose with the program was to increase the rate of Sweden´s transition towards an ecologically sustainable society. 250 million SEK out of the total fund of 6.2 billion SEK was given out for the development of Bo01 (Persson, 2005). The initial idea was to establish the exhibition in the area of Ön in Malmö’s southwestern city district Limhamn, but eventually the location was changed to a new industrial land area which the municipality had then acquired, today known as Western Harbour (Persson,2005). The LIP program funding was used to cover the costs for ecologically sustainable solutions for the Bo01 area, where the goals in the application of the grant was stated as the following: “[...]Bo01 will become a leading example of environmental adaptation of a dense urban development. The area will also function as a motor in Malmö´s transition into ecological sustainability” (Persson, 2005, p.19).

The different projects and environmental interventions that were created as a part of Bo01 consists of eight different areas, which are described as areas making up the entirety of the development of Bo01. The eight areas are as follows.

1. Urban planning, 2. Land mass remediation, 3. Energy, 4. Circulation, 5. Traffic, 6. Green structures and water, 7. Building and residence, 8. Information, knowledge production, and exhibition activities.

Housing exhibition in the Western Harbour, focusing on green building technologies and the inclusion of green spaces.

Bo01

Bo01

3

2 & 3: Bridge in European Village and View into House in European Village

Figs.

A quality program was established between the municipality of Malmö and the building developers before the construction started, to ensure that the different goals of the exhibition and the development of the area were accomplished. The program served different functions to reach these goals. It would, for example, work as a tool for the involved parties to strive for the same ambitious results, as well as making sure that technical and qualitative requirements were secured. Most of the requirements of the quality program for Bo01 were of a qualitative sort, meaning that they could not be measured from absolute measurements. A few quantitative exceptions involved requirements for energy consumption and green area factors, which in this context are relevant considering the project's ecological focus (Larsson & Wallström, 2005). Examples of features that were demanded by the building developers in the quality program to ensure a high quality of the new city district´s ecological profile include the requirement of a certain amount of so-called green points, as well as the green area factor. The green points for Bo01 are a list of interventions which were inspired by a document created by the Naturskyddsföreningen (Swedish Society for Nature Conservation) in the late 1990's with the aim to create a greener Stockholm. The list was further developed by Bo01 to be used as a tool for a high-quality direction of the green features of the different housing projects of the exhibition and aimed towards the building developers and the landscape architects in the design process. Each individual project at Bo01 had to present the green points that were included in the documents before the building permit was granted. Out of 35 points on the list, at least 10 of these had to be included in each project. Requirements included for example, that there should be a bird house for every apartment unit, that half of the courtyard should consist of water, and that all the trees and bushes have edible fruit (Persson, 2005). The green area factor was for the first time implemented in an urban development in Sweden where it was applied to all the projects of Bo01. The idea behind this came from Berlin at the time, where the green area factor had been used as a principle in urban planning. By taking different ecological aspects of the land area for each project into consideration, a factor between 0 and 1 is calculated. For Bo01 a factor of at least 0.5

was required to ensure the ecological quality of the area by the building developers.

Factors which were taken into consideration were divided into three areas. These include factors for greenery, factors for impervious surfaces, and factors for local stormwater management (Persson, 2005). Not only were there ecologically high standards at Bo01 which were quantifiably measured by the previous examples of the green points and the green area factors, but also the architectural design included elements of ecological sustainability. Examples which were characteristic of the exhibition are the inclusion of solar thermal collectors, as well as the implementation of green roofs. One of the most prominent ecological measures in the development of Bo01 is the energy system which was developed to achieve selfsufficiency regarding sustainable energy production for the area. The idea from which the energy production would stem was to include renewable energy sources in the form of sun, wind and an aquifer in the ground. This was achieved by the usage of solar thermal collectors on buildings and the construction of a wind turbine in the Northern Harbour in Malmö, which provides the electricity needs for the area of Bo01 (Lövehed, 2005).

4

Fig. 4: Water feature in Bo01

Figs. 5 & 6: Solar energy technology Bo01

CASE STUDY: VARVSSTADEN

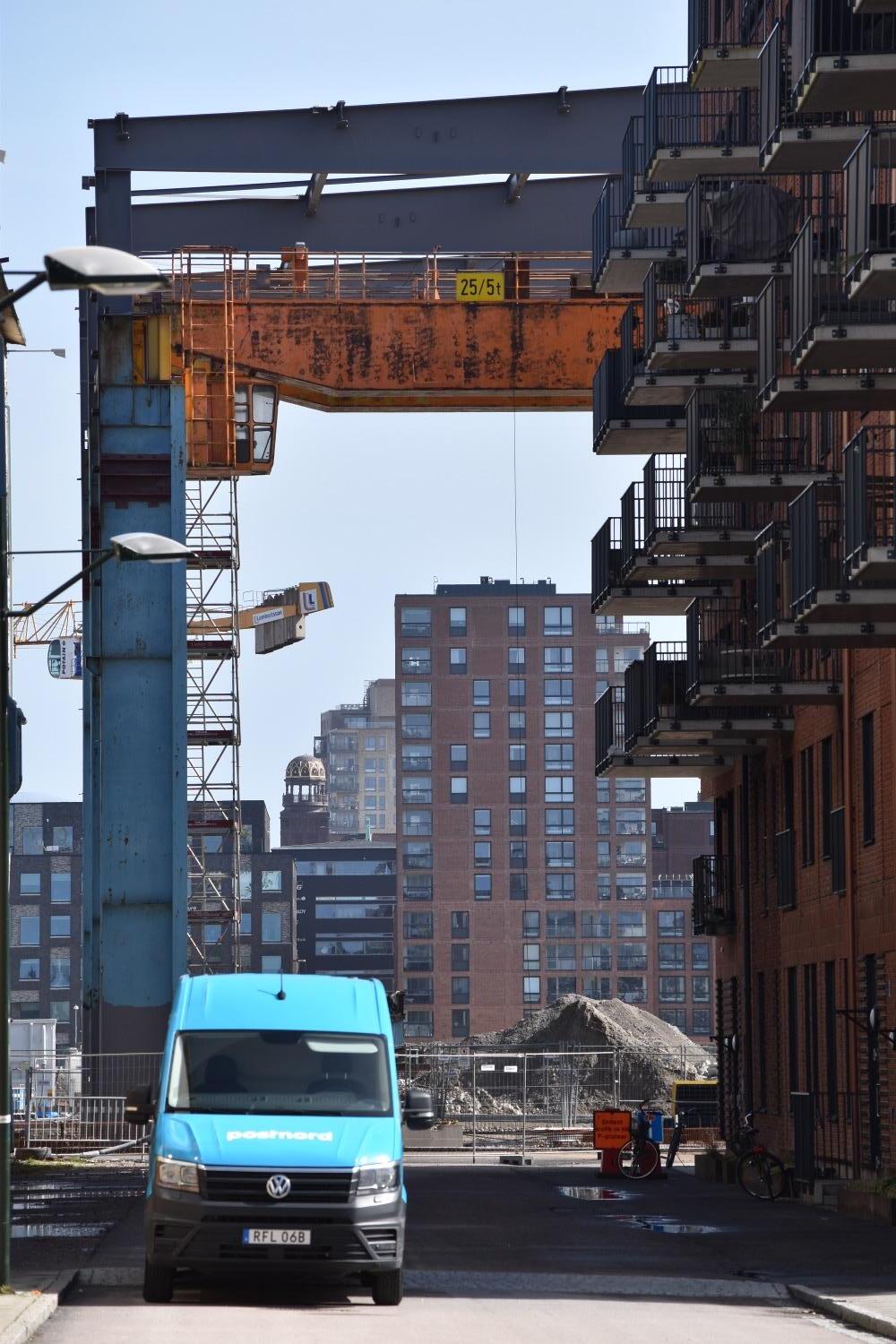

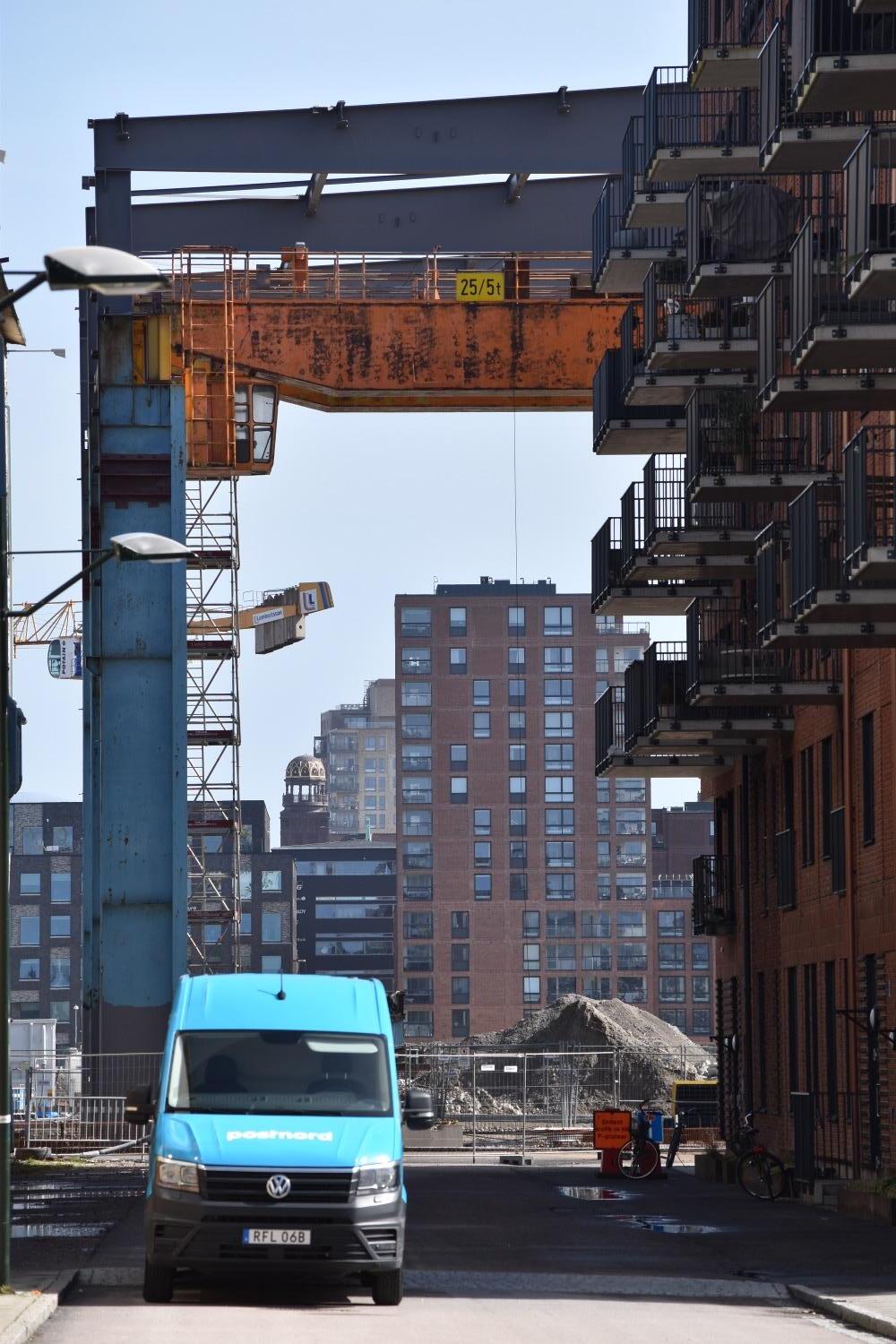

Varvsstaden is a former industrial land in the central parts of Malmö’s Western Harbour, comprised of several industrial buildings spread across an area of over 180.000 square metres. Most of the buildings in the area were constructed between 1910 and the 1950´s and are of varied character. The industrial history of the area goes back to the late 19th century, when Frans Henrik Kockum acquired property in the Western Harbour, which was used to establish a shipyard with the purpose to serve the production of railway wagons for the company Kockums Mekaniska Verkstad.

The company would at this time focus on the building of ships, and the shipyard opened in 1914. During the World Wars in the first half of the 20th century there was an extensive need for repairs of ships, as well as a need for the Swedish marines to expand their fleet. During the 1940´s the workforce almost doubled in size, which resulted in the need for a labour force from Denmark and Italy. Until the mid-1970's there was an intensive investment in the shipyard company, which ended abruptly by 1973 when the oil crisis and the following recession affected the shipyard industry negatively. In 1986 the Swedish government decided that all civil ship production would cease as a result of the negative economic trends trends (Lund, et.al., 2007).

The historic cultural value of the area is high with many features that have shaped the city of Malmö. Without the shipyard industry, the city would most likely not have developed its size and importance that it has today. The recruitment of an immigrant workforce from Southern Europe also contributed to the multicultural city, where in the end of the 1960's a fifth of the total workforce in the shipyard of over 6000 people were born outside of Sweden (Lund, et.al., 2007). The Kockums company was the largest employer in Malmö for over half a century and has in an international perspective been a prominent shipyard, as well as an important part of the identity of the city on a local level. The shipyard industry shaped both the silhouette and the geography of Malmö, as new landfills were placed in the Öresund strait, creating the contemporary coastline. Today, the large iconic

Kockums crane is no longer included in the silhouette of the city, the industrial area of Varvsstaden is on the other hand still well preserved in the Western Harbour (Lund, et.al., 2007).

Adaptive reuse and upcycling practices are realized in Malmö’s Western Harbour in consultation with Danish firm Lendager Group

Varvsstaden

5

Figs. 7 & 8: Industrial window in Gjuteriet building, and Facade of Gjuteriet building

POLICY EVOLUTION

MILJÖBYGGNAD

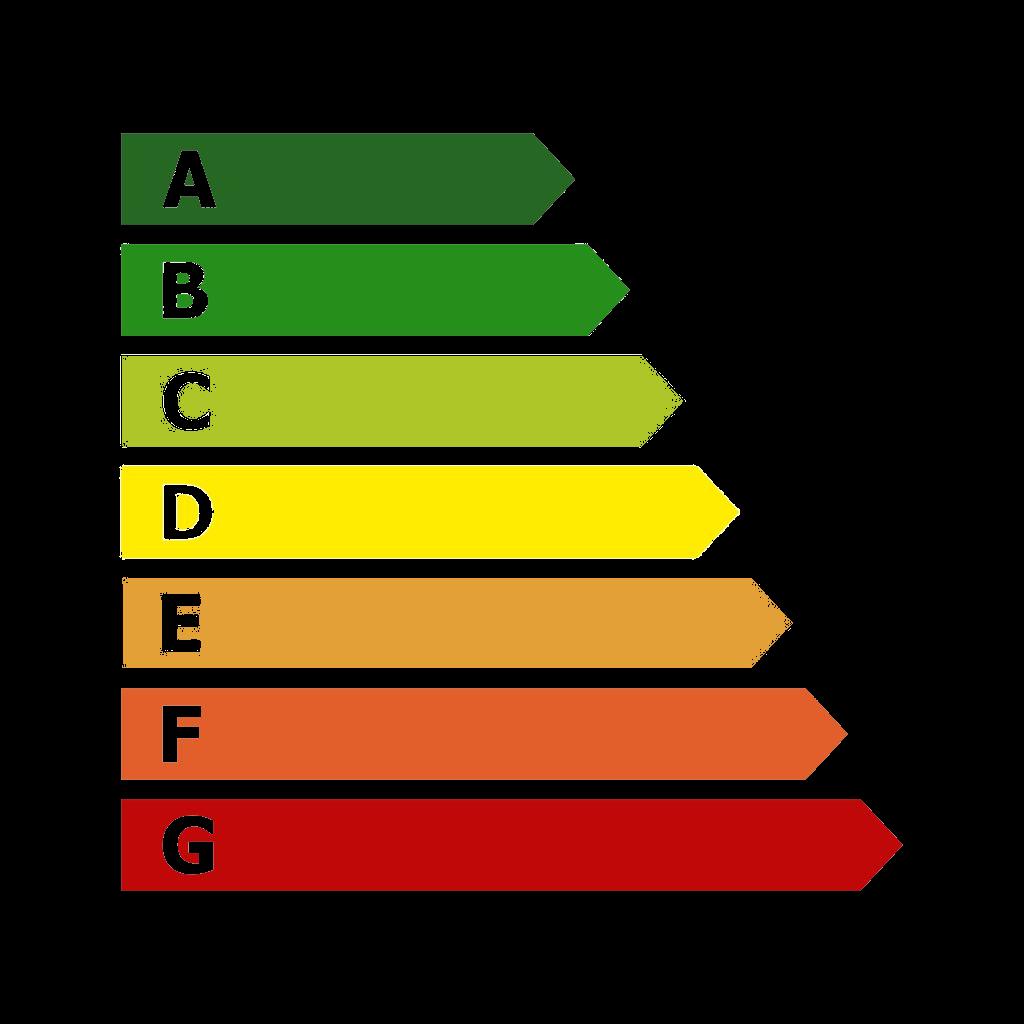

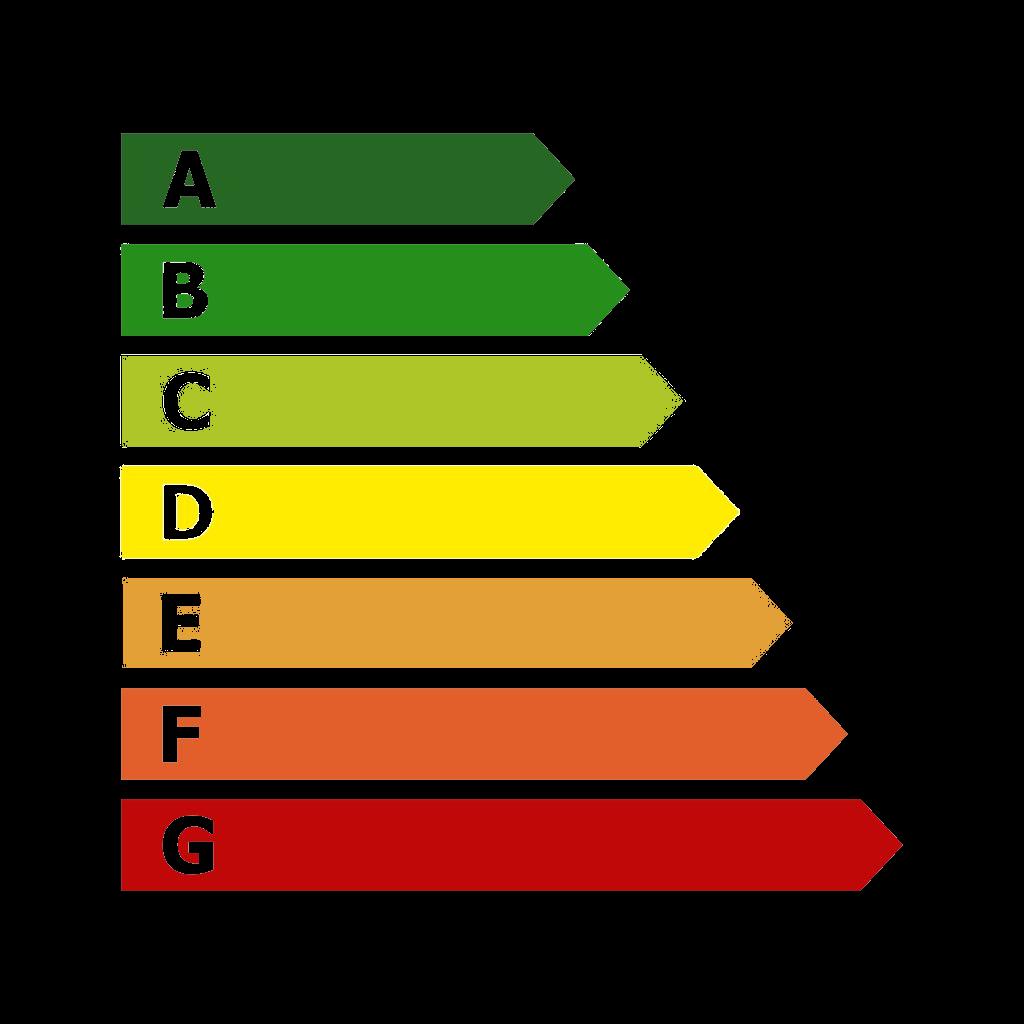

Miljöbyggnad is a Swedish environmental assessment method considering buildings, where the certification includes the environmental work and performance which is assessed by a third party. The assessment method is owned and developed by Sweden's largest organisation for sustainable urban development, the Sweden Green Building Council (SGBC) which is responsible for the certifications. There are a total of 16 different indicators, where the emphasis is on the indoor climate, measuring air quality, ventilation performance, the amount of daylight, and the concentration of radon, to name a few (Miljöbyggnad, 2022a). There are three different levels of certification: bronze, silver, and gold. Bronze is the first level and is achieved by conforming to the legal requirements and existing recommendations. The silver level is achieved if the performance of a building in consideration to the indicators is well above the minimum requirements. Most developers who decide to approach a Miljöbyggnad certification aim for this level which is a clear statement from the developers that they are committed to environmental aspects. The gold standard is for the most ambitious developers where the requirements are high, and the qualities of the building are more advanced to assess (Miljöbyggnad, 2022).

Reuse and Upcycling Practices

The indicators for achieving a certain standard for a building are presented in the Miljöbyggnad manual, which was first published in 2010 as Miljöbyggnad 2.0. Since then, there have been several updates to the manual and the newest generation is called Miljöbyggnad 4.0. The manuals are available in two different versions, considering if the building is newly constructed or if it is renovated. The fourth generation (Miljöbyggnad 4.0) was released on the 6th of December 2022. With the climate change as a background to the development of the latest release of the manual, the aim of the development of the latest addition of the Miljöbyggnad manual has been to weave in parts of the EU taxonomy, as well as to update the indicators in relation to new standards, legislative requirements, and other needs. The most significant difference in Miljöbyggnad 4.0 is the apparent consideration for reuse, circularity, and ecosystem services (Miljöbyggnad, 2022b). There are now four new indicators added into the manual which are aimed at property owners to have a more holistic approach to sustainability, they are as follows: Indicator 10 – Climate risks, Indicator 11 – Ecosystem services, Indicator 12

Miljöbyggnad 4.0 begins incorporating adaptive reuse and upcycling practices as indicators in the manual.

Miljöbyggnad 2.0 begins to guide urban developments in Sweden towards sustainable building practices.

Evolving Environmental Policies

– Flexibility and demountability, and Indicator 14 – Waste management. By conforming to the EU taxonomy, Miljöbyggnad has strengthened its focus on the drive for sustainability by the inclusion of the indicators mentioned earlier. The taxonomy defines what an ecologically sustainable economic investment is, by applying a common classifying system. The aim is to reach the climate goals in the Paris 2050 agreement by conforming to the taxonomy directives (Wienerberger, 2023).

6

Fig. 9: Miljobyggnad logo

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: THE THREE PILLARS

When thinking about sustainable development it may be difficult to land on a single explicit definition as so many already exist, each taking different perspectives on the issue. However, one of the most well-known definitions from the Brundtland Report, published in October 1987 by the United Nations, helps to break down the concept into three distinct areas of focus: environmental sustainability e.g. “[...]the exploitation of resources,” economic sustainability e.g. “[...]the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development,” and social sustainability e.g. “[...] current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, pp. 43, 46).

Environmental sustainability can best be defined as addressing the conservation and preservation of the natural environment and resources. It involves protecting biodiversity, ecosystems, reducing pollution and waste, mitigating climate change, and promoting sustainable land use and resource management (United Nations Environment Programme, 2000). Economic sustainability pertains to the economic systems and activities that support sustainable development and addresses concerns such as the promotion of economic growth, the efficient use of resources and issues of inequality and poverty (International Institute for Sustainable Development, n.d.). Social sustainability focuses on the well-being and quality of life of individuals and communities, encompassing aspects such as social equity, human rights, health, education, and cultural diversity (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). Together, each of these three areas of focus or “pillars,” are known as ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance.) Within our research we have chosen to look at the sustainable building practices taking place in the Western Harbour through the lens of environmental sustainability.

When examining these two case studies we do note that there are overlapping perceptions of social sustainability within the conceptions of Bo01 and Varvsstaden, each within their own time seeking to provide human friendly neighbourhoods as modelled by Bo01’s intention to “[...] model new arrangements for living, working, and playing for all occupants and visitors” (Holden, Airas & Larsen, 2019, p. 156) and Varvsstaden’s goals for a careful design of public space, streets and buildings in which “[...] ‘life in the houses’ and ‘life between the houses’ can work in wonderful symbiosis with each other” (Varvsstaden, 2024). Through the lens of economic sustainability, this idea can be traced back to the pure economic gains of upcycling or reusing materials versus the higher manufacturing costs of new materials, which we have discovered is not always economically viable from an investment perspective when compared to traditional approaches for new construction. However, where we see the most interesting and stark contrasts in sustainable philosophy is within the discourse surrounding Bo01 and Varvsstaden and the clear concentration in both cases on environmental sustainability. Upcycling and adaptive reuse practices fall within discussions of resource management and waste prevention.

7

CIRCULAR ECONOMY WITHIN THE CONSTRUCTION AND MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIES

Building sustainably has been a goal of many international organisations for several decades but has largely failed to yield much change in the construction and manufacturing industries. In 1987, the United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as “[...] ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’” (European Commission, 2018). To achieve this goal, industries need to become more conscious and innovative when it comes to how they consume resources while constructing new buildings. This drive to build more sustainably is becoming increasingly important as “[...] global resource demand is expected to double by 2050” and “supplies of rare metals could run out” (Geng et al., 2019) resulting in amplified pressure for the construction and manufacturing industries. In the Nordic context, a 2018 report from the Nordic Council of Ministers set forth a goal to “[...] accelerate a transition towards a circular economy in the construction sector in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden” (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2022) as a means of attaining improved sustainability. The concept of a circular economy itself is most simply defined as “[...] keeping resources inside a closed loop system” while aiming to “maximize the value of resources by allowing materials and products to be reused and thereby give greater purpose than disposal” (Moscati et al., 2023, p.3). Geissdoerfer et al. (2016) define the concept of circular economy as “[...] a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimized by slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops. This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling” . More broadly, applying this concept of a circular economy within the construction and manufacturing industries is what will allow for a transition to more sustainable and environmentally conscious practices within both industries.

This is in direct contrast to the current system which is more reflective of a linear economy centred around the “[...] concept of ‘take, make, dispose of’, where materials are used for their purpose once and then disposed of” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2014). As mentioned by Moscati et al. (2023) “[...]the construction industry is the largest single sector in most countries and an important trading partner for the manufacturing industry” (p. 3) which demonstrates the deep-rooted link that these two industries have. Furthermore, the construction and manufacturing industries are “[...] one of the largest consumers of resources, consuming about 50% of total raw material consumption and 36% of global final energy consumption” (Moscati et al., 2023, p. 3) which reveals the enormous impact that these industries have on the environment. According to Johansen & Rönnbäck (2021), there is currently “[...] increasing pressure on the Swedish manufacturing companies to support the transition to circular economy and new requirements are constantly being introduced” adding that ‘in order for manufacturing companies to thrive, they will need to enhance their competitiveness through sustainability and circular economy aspects’” . Unfortunately, there seems to be a gap in understanding within those industries in Sweden when it comes to the concept of a circular economy. Moscati et al. (2023) argue throughout their study of the two industries in Sweden, “[...] a pervasive barrier to the transition emerged as a lack of organization, knowledge, and understanding of the circular economy concept and its economic benefits” (p. 14). They argue that “[...] awareness and knowledge of CE (circular economy) among stakeholders must be improved” and that “[...] collaborations are needed between stakeholders in order to share experiences for future cross-sectional working processes” (Moscati et al., 2023, p.14).

8

NEOLIBERAL PLANNING PRINCIPLES

To better understand the economic conditions for which the Western Harbour was developed under, it is important to consider several aspects of neoliberal planning principles that have helped to guide the development projects at Bo01 and Varvsstaden. Neoliberal planning “[...]can be understood as a restructuring of the relationship between private capital owners and the state, which rationalises and promotes a growth-first approach to urban development” (Sager, 2011). This modern arrangement of planning powers, essentially places more power in the hands of private developers when it comes to building new parts of the city, Western Harbour included. These private companies develop land with their own ideals in mind and Beaten (2012) argues that private developers at work in the Western Harbour “[...] want Malmö to develop along modern lines, thereby erasing the past: the industrial past, the unemployed, the (ethnic) poor, the non-adapted to the 21st-century service economy, and their necessary replacement with the creative classes” (p. 37). In this sense, when plans were made for

the Western Harbour, the private companies tasked with the development did not necessarily consider the needs of those currently living in Malmö as they were “[...] largely designed to attract a new class of people and in that way change the social demography of the city” (Baeten, 2012, p. 38). Baeten (2012) argues that this new way of planning in Malmö was pioneered at the Western Harbour. It is clearly marked by “[...] the attraction of high-profile architects, the organisation of high-profile architectural competitions, the allocation of land to major developers without wider consultation, and the unmatched desire to build a new city for new people” (p. 38).

It is important to note that this way of thinking is what allowed for both Bo01 and Varvsstaden to develop in the ways that they have. Both projects have seemingly departed from serving the needs of the current citizens of Malmö to becoming reflective of more idealised planning principles when it comes to environmental sustainability that are ultimately placed within a profit maximising agenda. The challenge from a planning perspective, as Beaten (2017) argues, lies “[...] in how to continue to pursue the integration of economic, environmental and social issues in land use decisions when economic concerns are prioritised (and) social and environmental concerns are co-opted to fit into the profit-maximising agenda” (p. 10).

9

Neoliberal planning principles take hold in Malmö’s newest developments seeking to attract a new class of resident. New City Image

Figs. 10 & 11: Curious dog and view of private gardens in European Village

BRANDSCAPES

When redeveloping the Western Harbour in Malmö there was great consideration taken to not only how the new district would be laid out, but what this new district would ‘say’ about the city. Malmö previously had an image of an industrially focused working-class city, and with the shuttering of the Kockums shipyard and surrounding industry, there was great attention on how the city would rebrand itself. This process of redeveloping the old harbour lands, ties directly to the concept of ‘brandscapes’ which reflects how “ [...] such processes of conversion leave imprints on the landscape” (Swensen & Granberg, 2024, p. 103). In other words, “[w]hen used in connection with urbanism and cities, branding is defined as a specific form of place branding, which involves the creation and promotion of a designated identity for a city’” (Swensen & Granberg, 2024, p. 103-4). The concept of brandscapes “[...] typifies many of the processes that large urban development projects undergo, emphasising the entanglement of economic considerations and visual symbols” (Swensen & Granberg, 2024, p. 103). For Malmö, losing much of its industrial history prompted a deep consideration regarding its future economic drivers. Much of this history was embodied in the largest shipyard crane (at the time), which was sold when Kockums ceased operation in the area, and so there was a desire to create a new visual symbol in its place - this became the Turning Torso tower, a part of to Bo01. When considering the repurposing of industrial buildings in the Varvsstaden area, Swensen and Granberg (2024) note that “[i]ndustrial buildings are considered resources in an experience economy, providing a mixture of services, including cultural and recreational adventures” adding that they “[...] become historicised and aestheticised and are used as part of a brandscape” (p. 104). It is important to consider that “[...] reprofiling post-industrial urban areas this way can, from a heritage point of view, be criticised for being “vague images of former landscapes and appear as new construction that are completely detached from specific places’” (Swensen & Granberg, 2024, p. 104).

We can see examples of this in the newly developed area of Varvsstaden, with a mix of old and new buildings, which although a nod to a not-so-distant past, are somewhat detached from their former landscapes. As the development of the area is not yet complete, developers must carefully consider the final visual brand they want to impart on the area, as “[...] the tight- knit relationship between the urban landscape and its historic fabric too often fails to be acknowledged” (Swenson & Granberg, 2024, p. 104).

10

Figs. 12 & 13: Turning Torso in Bo01 and Industrial scaffolding Varvsstaden

METHODS

In order for us to further investigate and analyse the research questions, we decided to conduct two case study analyses through the implementation of three main methods including observations, interviews and document analysis. Together with our conceptual framework, these methods allow for us to form an in-depth review of sustainable construction practices in the Western Harbour.

OBSERVATIONS AND FILM

In very basic terms, observations can be described as “[...] the systematic description of the events, behaviours, and artefacts of a social setting” (Kawulich, 2012, p. 2). Moreover, there are two main types of observations, what is known as participant observation, and direct observation - the type employed for this research. Direct observation “[...] involves observing without interacting with the objects or people under study in the setting” and can provide the researcher with the ability to record rich, detailed descriptions of these settings. These detailed notes can then be used to develop more relevant questions to be asked of informants (Kawulich, 2012, p. 3, 7).

Relating specifically to the chosen area of study, observations undertaken in the Western Harbour, focusing on Bo01 and Varvsstaden allowed for more qualitative, evidence-based examples of upcycled materials in their built form and within the urban environment, largely in the form of photographs. Information gathered during this time was used to help guide the creation of two interview guides with informants working in the sustainable construction field, as well as two additional interviews; one with an informant heavily involved in the development of the environmental quality program at Bo01, and a second informant working at Varvsstaden. In addition to our own observational notes and photographs, we filmed a walk-along tour of the two case study areas to enrich our mixed-methodology approach and provide a recorded collection of naturally occurring data (Jewitt, 2012).

11

Fig .14: Nikon D3500 DX D-SLR Camera

Figs. 15 & 16: Intrepid explorers Rob, Herman, and Sebastian

Svea, Sebastian and Rob take you on a walk-along in Malmö’s Western Harbor Varvsstaden and Bo01 areas.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrfcUraadBg

12

INTERVIEWS

As previously mentioned, interviews were also used as an integral method for further investigation of our research question. Interviews provide a wealth of information when used appropriately and “[...] enable interpersonal contact, context sensitivity, and conversational flexibility to the fullest extent” (Brinkmann, 2018, p. 1000). For the purposes of our research, semi structured interviews were used. According to Brinkmann (2018), “[...] semi structured interviews can make better use of the knowledge-producing potentials of dialogues by allowing much more leeway for following up on whatever angles are deemed important by the interviewee” (p. 1002).

More specifically, this style of interview can allow for a more natural conversation to occur, rather than a more rigid question and answer format. In the context of our research, a semi structured interview allowed for us to be a little more flexible with our informants, while still having some pre-formulated questions that were decided on beforehand. As previously indicated, it was our initial observation period that helped to guide the creation of our first two interview guides. In working to find relevant informants to address our research questions we came across the master's thesis of Taleen Josefsson who is an architect in Brooklyn, New York (TAJ Architecture Studio PLLC) where she works mainly with material re-use and the upcycling of various building materials with a wide range of clients ranging in scale. Her master's thesis focused on what she described as the ‘reuse revolution’ and was very relevant to our topic as it was written within a Swedish context. It was through Taleen’s connections that we were able to contact our second informant, Jan Dankmeyer who is a Design Architect at Lendager Group specialising in sustainability and circular design. Lendager Group is involved with Varvsstaden in a consultancy role where, together with Varvsstaden, they have been responsible for the creation of an “idekatalog ”, which is a collection of materials and guiding principles that are helping to shape the development of Varvsstaden’s recent construction projects.

Our third informant is Eva Dalman who is a now retired architect and was at the time the area architect for Bo01, responsible for developing the quality program. Eva was personally approached through the encouragement of our supervisor. Our fourth informant is Hanne Birk, who is a Development Manager at Varvsstaden and has been heavily involved in the company’s vision for the area since the beginning of its development.

Transkribering, intervju med Eva Dalman

Sebastian Amaya Segura: Där kör vi igång Vi kan ställa den där kanske

Eva Dalman Men det var Västra hamnen ja

SAS Ja, precis Så att vi

ED Historia

SAS Ja, exakt Vi sitter ju och gör ett grupprojekt som vi har gjort på den här kursen Det är vårt första år på mastersutbildningen som är inom urbana studier på Malmö Universitet

ED Det är jag väl bekant med Ja, den utbildningen Jättebra

SAS Och då är ju vårat syfte med arbetet egentligen från vår sida, det är att skapa en slags tidslinje kan man säga Så att vi vill ju se hur hållbara stadsbyggnadsideal och olika praxis har förändrats från Bo01 Där du då är en huvudperson i det här och vi är väldigt tacksamma för att du vill ställa upp på den här intervjun Och sen så vill vi se hur det har sett ut just i Västra hamnen då med utvecklingen fram tills idag Där vi har det främsta exemplet med Varvsstaden då Så att det är det vi är nyfikna på lite och se vad är det som påverkar förändringarna vilka skillnader ser vi egentligen?

ED Ja, och då tror jag att jag måste börja med ett sidospår som inte är Västra hamnen

SAS Ja, det får du jättegärna göra

Speaker 1: Fyrtunnet, yeah They have making a lot, they have making a lot of good choices there I mean, I think you will be able to learn a lot of that project Okay, yeah, perfect

Speaker 2 And then will recommend you to contact Imbila Okay Imbila is the person that actually are working for, hold by the, from Peab Okay So maybe it's best, of this case, you contact Peab actually So can only talk about how we are making up cycling in the old building and in the area Just for more I fell on the first question

Speaker 1: No, it's fine It's good that we have some clarification Because then, for, so as we understand it, Varvsstaden is basically just, how do you say it? I mean, it's just commercial spaces, right? That you are developing

Speaker 2 No, I can say Varvsstaden is owned by Balder and Peab Yeah And they have to make what's called, I mean, a company called Varvsstaden And that's one is the company they are working with the detail plan We are making the whole area, but we are not, and then we are selling the houses So the, don't know what it's called

Figs. 17 & 18: Transcripts from interviews

13

INFORMANTS

TALEEN JOSEFSSON

Taleen is a New York State registered architect, holds a U.S. Passive House Consultant certification, is a BREEAM AP, and has received training in Healthy Materials specification. She has been deeply involved in environmental activism, participating in volunteer organizations to support industry-wide construction and demolition waste reduction through material reuse. Having worked for firms in the U.S. and the U.K. as an architect, designer, and sustainability consultant over the past 12+ years, Taleen recently established her own practice to apply her expertise through a holistic approach to architecture and consult for other architecture firms in her capacity as a sustainability consultant. She wrote her master’s thesis in 2019 titled, Form Follows Availability – The Reuse Revolution, at Chalmers University in Gothenburg, which speaks directly to the subject matter of our investigation. We had the chance to interview her to gain further perspective into the sustainable construction industry, her thoughts on influences and trends, as well as limitations that the industry faces, both in the EU and in the North American context.

JAN DANKMEYER

Jan Dankmeyer is a Design Architect at Lendager specialising in sustainability and circular design. His work focuses on the intersection of architecture and public space with a deep interest in behavioural design. He has worked in Germany co-leading the design of an urban densification project in Göttingen and has been involved in projects in Hamburg and Düsseldorf. He has a Master of Science in Architecture and Planning Beyond Sustainability from Chalmers University of Technology and completed a four-course online learning program, Healthier Materials and Sustainable building from the Parsons School of Design, which focuses on the relationship between building materials and the human body. We were able to get in contact with Jan with Taleen’s help. Not only did we get the chance to speak with Jan, but we were also given a tour of the Lendager office space in Copenhagen, which contained project models and upcycled material mock-ups.

14

Fig. 19: Taleen Josefsson

Fig. 20: Jan Dankmeyer

EVA DALMAN

Eva Dalman is an architect who was employed as a Project Manager at the municipality of Malmö between 1989-2009. At the time of the development of Bo01 she was on leave from her employment to take the role as a consultant where she was responsible for developing the environmental quality program for the area. Between the years 2009-2024 she was employed at the municipality of Lund where she worked as a Project Manager for the development of the Brunnshög area until her retirement in early 2024. Dalman is an advocate for putting humans before cars and building cities which support human needs and a sustainable lifestyle.

Hanne Birk is the Developing Manager at Varvsstaden AB, where she has been employed since 2014. Her experiences in the field of architecture range from practicing architecture in her own business, to Project Manager at M2 A/S, as well as Project Developer at Skanska Nya Hem.

15

HANNE BIRK

Fig. 21: Eva Dalman

Fig. 22: Hanne Birk

DOCUMENT ANALYSIS

Document analysis is an additional method that was employed for this research study. This method mainly serves as “[...]a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents both printed and electronic” (Bowen, 2009, p. 27) and similar to other analytical methods, “[...] requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge” (Bowen, 2009, p. 27). Document analysis is most often used in conjunction with other qualitative methods, such as observations and interviews to seek convergence and corroboration across different sources of data (Bowen, 2009, p. 28). Overall, Bowen (2009) writes that “[...] documents provide background and context, additional questions to be asked, supplementary data, a means of tracking change and development, and verification of findings from other data sources” (p.30). Therefore, in the context of this research study, a document analysis allows for us to delve deeper into our chosen case studies of Bo01 and Varvsstaden, identify key elements of these areas and compare them to general themes uncovered through the use of previously mentioned methods, as well as concepts identified in the theoretical framework. This method forms the main basis of the background for this study in addition to our findings and results.

16

Miljöbyggnad släpps runt årsskiftet

Fig. 23: Malnualversion

3.2

Fig. 24: Article “Förändringarna i Miljöbyggnad 3.0-det här bör du tänka på,” from Byggnorden

publication “Avfall i Sverige 2020”

Fig. 25: Naturvårdsverket

FINDINGS AND RESULTS

CASE STUDY: Bo01

The Western Harbour can be described as an experimentation arena for the environmental sustainability discourse, with the Bo01 exhibition being one of the largest pioneering projects in Sweden at the time (Interview with Eva Dalman, 2024). Not only were there ecologically high standards at Bo01 which were quantifiably measured through the green points system and the green area factors, but also the architectural design integrated elements of ecological sustainability. One of the most prominent ecological measures in the development of Bo01 is the energy system which was developed to achieve self-sufficient energy production for the area through renewable sources, including solar, wind and water energy. This was achieved through the use of solar thermal collectors on buildings and the construction of a wind turbine in the Northern Harbour.

Principles of the ESG pillar concerning environmental sustainability are very prominent in Bo01. The implementation of green technology translate to the reduction of pollution as well as the mitigation of climate change. This can be motivated by the ambitions that the area had of being energy self-sufficient, as well as goals to protect biodiversity and the ecosystem through the inclusion of green features in the form of greenery on the roof and walls, as well as water resources. The development process of Bo01 is described by Eva Dalman as being a “journey of knowledge” where construction companies had to be enlightened about the meaning of sustainability before the start of the construction. A team of ambitious developers worked together to shape the environmental sustainability features that were to be included in the quality program for the area. One of these was landscape architect Agneta Persson, who was very aware of trends both in Sweden and in the rest of Europe. Persson worked to implement the green point system and green area factors in Bo01’s surrounding landscape as they were developed together with Bengt Persson, another consultant in the team. In

mentioning trendsetting as a feature of Bo01’s development and the sustainability discourse surrounding the area, it is relevant to mention that the team also looked closely at Hammarby Sjöstad´s approach to sustainability practices. Hammarby Sjöstad is a city district in Stockholm which was built between 1994 and 2020. Similar to Bo01’s industrial setting in the Western Harbour, Hammarby Sjöstad was built in an old industrial park.

”When we started with Bo01 the building contractors didn’t know what sustainability was. We had to explain to them as part of a journey of knowledge.”

- Eva Dalman -

17 Figs. 26 & 27: Solar technologies in Bo01 Fig. 28: Map of Bo01 area

Hammarby Sjöstad’s development was intended to serve as the Olympic Village in Stockholm´s application to host the 2004 Olympic Summer Games. As described by the city of Stockholm, the architectural expression of the area is an “[…] excellent example of urban supermodernism that was in vogue during the ´90s. Simple and clean shapes and materials, that put function before form. ” (Visit Stockholm, 2024). The functional focus which was also alluded to, or rather explicitly expressed in the architecture of Bo01, suggests a modern take on the built environment with the inclusion of hi-tech sustainability measures (solar panels, wind turbines), as well as the large windows for maximized daylight exposure indoors. As a city which was “[…] spearhead[ing] sustainable city-planning” (Visit Stockholm, 2024) at the time, it is understandable that the development team at Bo01 looked to Hammarby for inspiration. Other similarities can be drawn between these two large scale urban developments in looking at the transformation of an industrial area to a constructed post-industrial reality, where a new image for the city is created. Both Madureira and Baeten (2016) put Bo01 forward as the predecessor for other large scale urban developments in the contemporary urban fabric of Malmö, including Hyllie and Norra Sorgenfri. Bo01 and the Western Harbour area are in this context advertised by the municipality as a “best practice” example of architecture which will attract companies in knowledge intensive sectors as well as a physical proof that Malmö has left its industrial past behind (Madureira & Baeten, 2016). The explicit ultra modernist expression of the planning and architecture of Bo01 created a new brand for the area replacing the older industrial image of the city with another expression of attraction. The loss of the Kockums crane created an empty canvas in the silhouette of the city and another majestic figure took its place.

The completion of the Turning Torso in proximity to the Bo01 exhibition area filled this gap and concluded the transitional phase of turning the worn-down industrial brownfields into the attractive forward-thinking and technology-driven node Malmö now strived for.

Environmental Programs

Construction began at Hammarby Sjöstad which influenced the environmental program for Bo01.

18

Fig. 29: View of Bo01

It can be argued that the apparent unachieved goals regarding the ambitious environmental implementations in the construction of Bo01 conception of the area as being created in favour of transforming from a declining industrial city towards a knowledge intensive Öresund region, rather than practising and managing the green made at Bo01. These unachieved goals are presented in a variety both in the following years of the area ´ s completion, as well as some Several years after completion, the energy system of the area was how well the calculated energy usage goals by the residents in the Regarding the energy goals in the quality program, the value of 105 meter BRA (Bruksarea = the area in a building which is used for a per year was proposed as a requirement. Measurements of the expenditure of 10 different buildings two years after completion showed of them reached this goal value. Some of the buildings even doubled calculated energy expenditure (Nilsson & Elmroth, 2005). There are for the discrepancy between the calculated and the actual energy the buildings at Bo01, with many of them being of general construction of residential buildings. The main reasons that are found relates to not having energy-efficient appliances, the large windows characteristic of the building´s design, as well as reported leakages envelope. Another issue mentioned is the flawed energy calculations which according to Nilsson and Elmroth was a result of underestimating energy expenditures. This is also backed up by Eva Dalman, who factors as contributing to underachieving these energy goals. Dalman today's energy declaration is a step in the right direction as there are certified actors who proved these to assure that the requirements are met, which was not as accessible when Bo01 was developed.

19

Figs. 30 & 31: Bygg.se Energideklaration and Modern apartment building in Sweden

Another example of an evaluation of the sustainability objectives at Bo01 is highlighted in the 2021 master´s thesis by Hanna Eriksson, in which the author examines the number of green areas in the area at the completion vis-à-vis 20 years later. Eriksson rhetorically asks if Bo01 can be seen as a shattered vision, regarding the declining greenery and ecological features related to the green area factors, which in fact was introduced with the development of the area (2021). The result of the research shows that greenery and water areas have shrunk in size at Bo01 in the last twenty years, where impervious surfaces have replaced previously green areas. Other findings which support the notion of a vision which has not stood its ground is that vertical greenery as green walls and vines is missing, water areas as well, and that the green roofs which were once introduced as an architectural ecologically prominent feature have become smaller (Eriksson, 2021). An additional finding which is noted by Eriksson is that the larger trees have become fewer, which is explained by diseased trees due to subpar soil conditions and a restricted growth area. The green area factor which was a benchmark for developing the individual housing project of Bo01 is evaluated in the thesis and presents declining numbers as well. For each of the six different courtyards included in the study, the green area factor has declined amongst all of them compared to what was initially planned (Eriksson, 2021). Approaches to sustainable construction in Malmö´s Western Harbour, which in this research project have been made apparent from the start of the Bo01 area, have changed during the 25 years which has passed since then. The view on sustainable building in Sweden has lagged, where in the 1990's UK it was already on the agenda to talk about built in carbon dioxide, while the focus at the same time in Sweden was surrounding energy expenditure (Interview with Eva Dalman, 2024).

The contrast is clear in the local context as the heritage of Bo01 expresses another understanding to the environmentally sustainable practices praised at the time, consisting of a variation of architectural expression which included the modernist approach to embrace greenery and small-scale water supplies. Not only was this the focus during the development of the area, but other obscured features were also focusing on self-sufficiency, creating a kind of individual village where energy production and waste management was implemented for the individual households to take part of. In comparison to the contemporary sustainable construction approach to highlight the carbon dioxide footprint which is made up of built in material and production of such, Varvsstaden expresses a change in the building practices in the Western Harbour currently.

“I think it’s good that the discourse today talks about carbon dioxide. At the time of Bo01 I was at a conference in England, as there was a lot of travelling as part of the job. Back then the British were already talking about the ’built-in’ carbon dioxide.”

-Eva Dalman-

20

FINDINGS AND RESULTS

CASE STUDY: VARVSSTADEN

In 2011 a new planning program for the area of Varvsstaden was presented by the municipality of Malmö. Together with Swedish construction company Peab, the municipality developed the program as a consensual vision for the area. Later, the joint venture company Varvsstaden AB would be formed, consisting of abovementioned construction company Peab, as well as real estate company Balder (Malmö Stad 2011, Fastighets AB Balder, 2022). The goal with the general overview plan for the area is “[…] to create an inner-city environment which has a large variation in functions, a richness of meeting spots, as well as lively public spaces” (Malmö Stad, 2011, p.11.). The stated purpose in the plan is to develop an area of mixed buildings with respect to the culturally and historically valuable built environment. It is also mentioned that the program serves as a compass for the direction of the continuing development of Varvsstaden over the next 20 years (Malmö stad, 2011). The approach for the development of the area is to emphasise sustainability practices as reuse and upcycling, where the motto of the company is “[...] The better we keep, the better we can renew” (Varvsstaden, 2024). Importantly, the existing buildings, which hold significant cultural and historical value, are demounted, rather than demolished. Through our observations undertaken of the area we were able to observe first-hand the extent to which Varvsstaden has worked to achieve this goal. Despite a large part of the area still being under construction, we were able to tour one of the fully completed buildings, Gjuteriet, which is currently occupied by the company Oatly and serves as an office space. The building itself incorporates an estimated 45.000 bricks that were de-mounted from surrounding buildings, reused steel sourced from surrounding buildings and sound insulation features made from recycled building materials. Even the new materials used for this building were sourced in a sustainable way, with the structural timber being sourced from northern Sweden, and office furniture being sourced second-hand. In this way, the building is aiming to meet much of what the circular economy goals

for Sweden envision, where materials are reused instead of manufactured from new and serve to ensure that the building meets the three pillars of sustainable development – environmental sustainability, economic sustainability, and social sustainability.

21

Fig. 36: Map of Varvsstaden area

Figs. 32, 33, 34, 35: Interior Oatly office in Gjuteriet building

The sustainability strategy employed at Varvsstaden AB has been developed together with the Danish sustainability and circular economy company Lendager Group and has served as basis for decision making in both zoning plans and in projects (Varvsstaden, 2024). In our interview with Hanne Birk, we understood that the process for which Varvsstaden endeavoured to build out the property was very new territory for the company. They had little prior knowledge of how to work within the ideals of a circular economy and depended a great deal on Lendager Group to help them pave a path forward for how to properly survey the available land and buildings, as well as create a material bank for which to store reusable materials. In addition to our meeting with Hanne, we had the opportunity of meeting Jan Dankmeyer, who is a Design Architect at Lendager Group specialising in sustainability and circular design. Although not directly involved in the Varvsstaden project, Jan was able to provide us with valuable insight into the state of sustainability and the circular economy within the Nordic context and some of the projects that Lendager Group are involved in. As a whole Jan states that we are good at making buildings efficient in terms of insulation and building systems, but we forget to factor in the carbon footprint that is left behind because of using certain materials. He estimates that 70-75% of a given building’s carbon footprint is actually as a result of the materials used, and only a fourth coming from the actual operation of the buildings once they are completed. Despite this, he mentioned that he has witnessed a mind-set shift in terms of using more and more biogenic materials, some of which can be observed in the development of the Varvsstaden area. A total of nine buildings will be totally or partially preserved within the area, serving as the pieces of the development for which the practices of upcycling and reuse are being realised. These buildings are and will primarily be used as offices and commercial locales.

The housing structures which are under development today are new constructions and are not included in the buildings where upcycling and reuse practices are being made (Varvsstaden, 2024). Although Varvsstaden developed the general overview plan for the area to include housing, we understood from Hanne that this specific portion is not in fact managed by Varvsstaden themselves. Instead, Varvsstaden sells certain parcels of land which were set aside for housing to other private construction companies and leaves the development of those projects in their hands. Meaning that the housing projects themselves may not incorporate aspects of upcycling and adaptive reuse at all, although Hanne does note that Varvsstaden sells materials from their material bank, and so it is possible that some materials used may come from upcycled material.

“I

“And they came back to us and said, yeah, you have a lot of materials. And we were thinking, what are we going to do with all this? I mean, its a new way to think...we didn’t actually know at the time how we could use it.”

-Hanne Birk-

think there’s this shift from just being super efficient...because it’s a contradiction because you use more material to make a building efficient. But these materials you use, most of them are not biogenic.”

-Jan Dankmeyer-

22

The development of Varvsstaden being composed of a mix of both upcycled, re-used and new materials speaks to the disconnected state of the circular economy model which was discussed in our interview with architect Taleen Josefsson, who works mainly with material re-use and the upcycling of various building materials. Taleen states that the process of having private projects and large-scale company projects adopting sustainable construction practices is slowly evolving. From her perspective, most projects are adopting a more topical approach, that is reusing materials for surfaces and not necessarily to support the building's structural core, a sentiment also shared by Jan. Taleen believes this is largely the case because these facets of buildings are less regulated when it comes to their structural integrity requirements. This links directly to what is identified as missing links in the Swedish manufacturing and construction industry, which Moscati et al. (2023) summarise in the following points:

• Policymakers (governments) need to develop guidelines, laws, and regulations to force companies to switch from a linear to a circular economy business model.

• The construction and manufacturing industries need to implement new digital strategies.

• Standards must be developed.

• Digital models and shared databases must be used and new technologies for information sharing tested.

• Individuals need to put pressure on the industry by requiring and purchasing products that fulfill CE (circular economy) principles.

• Academic institutions need to develop the necessary knowledge and prepare generations entering the market in starting, undertaking, and pushing forward the transition towards a CE (p. 15).

“I see it in more topical approaches...People are reusing materials for surfaces, things that are not necessarily the building structures.”

-Taleen Josefsson-

23

Figs. 37, 38, 39: Upcycled materials and Industrial details in Varvsstaden

It’s important to note that some of the points identified above have largely been implemented by Varvsstaden. The company has conducted an analysis and overview of the variety of materials which are found in the existing structures of the area, concluding that the five most important material fractions are concrete, steel, bricks, glass, and wood. This comprehensive overview of the existing materials has resulted in two key modes of presentation, compiled by the Varvsstaden company. First, a catalogue of ideas has, together with Lendager Group, been developed and shared on their website. In this document the existing materials are presented and concretized in examples of how they can be utilised in new structures and functions. Secondly a material bank has been created in both a physical and digital form. The materials are today stored in a warehouse in the area, with a digital database accompanying it with climate savings data and other key figures connected to the materials (Varvsstaden, 2024). In addition to this, much of the work being done by Varvsstaden has been guided by the Miljöbyggnad 4.0, which focuses on a more holistic approach to sustainable development to reach the long-term climate goals set forth in the Paris 20250 agreement. What’s clear from this case study of Varvsstaden is that green building practices, upcycling and adaptive re-use initiatives have formed a large part of the development being completed in the Western Harbour. Varvsstaden has made a conscious effort to embody circular economic building practices in much of its completed and future projects, but more work needs to be done to ensure the longterm viability of these building practices. Without the proper regulatory framework being in place (including standards and policies), there is no requirement for companies to build in this way, and so the developments, and how sustainable they become, are largely left in the hands of these private developers, who can often struggle to prove the financial viability of these projects. With the looming threat of a raw material shortage, companies need to continue to innovate much further than what is currently being done at Varvsstaden.

24

Figs. 40 & 41: Varvsstaden Materialbank and Stål excerpt from Varvsstaden Idékatolog

CONCLUSION

Overall, as a result of our case study investigation into both the Bo01 project and the ongoing Varvsstaden development occurring in the Western Harbour, we have discovered how the notion of a sustainable development has changed over time. From the early 2000s, culminating in the Bo01 project, we can see how the development largely proceeded into unchartered territories when it came to what it meant to develop sustainably. At the time, and partly because this area was developed as an exhibition, the focus remained tied mainly to notions of energy consumption, with buildings and infrastructure being built with low C02 emission goals. We have also noted that during this time, the Swedish government, in addition to most world governments at the time, lacked the policy and regulations to guide such developments. Instead, these developments continued under the guise of neoliberal planning principles. These principles largely served to meet the desires of those developing the area who sought to attract a new creative class to Malmö, in the wake of the slowing industrial operations that had been a staple in the local economy for decades.

What we were left with is a development that, although marginally lower in emissions, failed to meet the lofty goals set forth by the exhibition's conception, and lacking a holistic approach to sustainable development. This relative failure resulted in large carbon footprints from the manufacturing of materials and construction undertaken to complete the project, which followed the traditional linear economic model. The development of Bo01 is then placed in high contrast with the newest emerging developments of the Western Harbour’s Varvsstaden, which seeks to highlight more recent trends of sustainable construction practices that are focused on regulations developed over the last twenty years and the concept of a circular economy.

However, as is similar to the Bo01 development, our research shows that Varvsstadens development is also falling short of totally meeting their own goals by creating an area that mixes both circular economic building principles and linear construction techniques. This can be partly understood as a result of an approach to the development of Varvsstaden which complies with the creation of an area aiming to attract the creative class, initiated by Bo01’s paving the way for this evolution of city branding in the Western Harbour.

25

This is apparent in how the (relatively low amount of) buildings which have notable architectural qualities are marketed as symbols for reuse and upcycling practices, while in actuality the majority of building structures in the area are not embracing the circular economic building practices made possible through the collaboration with Lendager Group. This creates an image of the district which follows trends in the general discourse surrounding reuse and upcycling (mainly accessible in the commercial sphere, focusing on the influence of second-hand stores and conscious consumerism), attracting a clientele who are drawn to these ideologies but do not necessarily adhere to them or develop them further. The Gjuteriet building which serves as an office space for the tenant Oatly is an example of such a notion where the ecological sustainability discourse is what makes the brand, within which the Varvsstaden image of a contemporary sustainable development fits very well in their marketing strategies.

With the three pillars of sustainability (focusing on social sustainability) in mind it can also be understood that the upcycling practices in the well-preserved buildings from a century back are serving actors who can afford to establish themselves in the area. This is in effect drawing focus away from the needs and possibilities of the general population of Malmö who may seek to improve their situation regarding the shortage of housing and affordability alike. With that being said, Varvsstaden should be commended for their efforts when it comes to building with circular economic aspects in mind, they have consciously recycled materials from previous industrial buildings and created a material bank in both a physical and digital form to be used for future projects.

This mindset demonstrates a potential shift in the building practices for all future Swedish construction projects, but as Swedish scholars note, there remains a gap to be filled within the regulatory framework to further promote these building practices. With a looming raw material shortage and an increasing need for housing construction, it begs the question of whether the circular economic model will be enough, or if further innovation is still required in order to avoid an extremely precarious situation for both the manufacturing and construction industries, as well as prospective residents.

26

Fig. 42: Image of quote on Varvsstaden poster

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

CIRCULAR ECONOMY

“Circular Economy is an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design. It replaces the EoL (end of life) concept with restoring, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, which impede reuse, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and, within this, business models” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2014)

ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY

Economic sustainability pertains to the economic systems and activities that support sustainable development and addresses concerns such as the promotion of economic growth, the efficient use of resources and issues of inequality and poverty (International Institute for Sustainable Development, n.d.).

ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY

Environmental sustainability can best be defined as addressing the conservation and preservation of the natural environment and resources. It involves protecting biodiversity, ecosystems, reducing pollution and waste, mitigating climate change, and promoting sustainable land use and resource management (United Nations Environment Programme, 2000).

LINEAR ECONOMY

“The concept of ‘take, make, dispose of’, where materials are used for their purpose once and then disposed of. ” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2014)

PRESERVE/MAINTAIN

Conserve and maintain existing buildings and building components on an ongoing basis e.g. preserve various existing ground covers and some structures instead of replacing them with completely new ones.

RECYCLING

“Recycling is the process of converting waste materials into new materials and objects. It is an alternative to ‘conventional’ waste disposal that can save material and help lower greenhouse gas emission” (‘Recycling’, 2019).

REDISTRIBUTE/REUSE

To reapply or reinstall a material (post-consumer, by-product, waste) in the same manner as originally intended or for a useful new application e.g. reuse of various building parts, material components or surface coatings after relocation within the Shipyard.

SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY

Social sustainability focuses on the well-being and quality of life of individuals and communities, encompassing aspects such as social equity, human rights, health, education, and cultural diversity (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987).

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

“In essence, sustainable development is a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development; and institutional change are all in harmony and enhance both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations” (Brundtland Commission, 1987).

UPCYCLING

Transform buildings to completely new purposes and/or rebuild them for new uses, reshape different building materials or building parts and assemble them into new constellations e.g. transform, reshape, rebuild. “Waste has the potential to become new materials or products with a higher utility value.” (Lendager, 2018).

27

REFERENCES

Alchermes, J. (1994). Spolia in Roman Cities of the Late Empire: Legislative Rationales and Architectural Reuse. Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 48, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/1291726.

Baeten, G. (2017) Neoliberal Planning, in Gunder, M. et al. (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory, London: Routledge, p. 105-117.

Baeten, G. (2012). Normalising Neoliberal Planning: The Case of Malmö, Sweden. The GeoJournal Library, 102, p. 21-42.

Brinkmann, S. (2018). “Interview,” The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, p. 997-1038, Editors Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln, SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bowen, G.A. (2009). "Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method," Qualitative Research Journal 9(2), pp. 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027.

Byggnorden. (2018). Förändringarna i Miljöbyggnad 3.0 – det här bör du tänka på.

Förändringarna i Miljöbyggnad 3.0 – det här bör du tänka på, Byggnorden.seNyhetskällan för dig inom bygg.Retrieved April 29, 2024.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation Towards the Circular Economy Vol.3: Accelerating the Scale-Up across Global Supply Chains. 2014. https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-3accelerating-the-scale-up-acrossglobal.

Eriksson, H. (2021). Bo01 20 år senare – en utvärdering av grönytefaktorn på Bo01 i Västra Hamnen, Malmö [Examensarbete för masterexamen, Lund Universitet]. Kandidatarbete_mall (lu.se). Retrieved Apr. 11, 2024.

European Commission. A Clean Planet for All a European Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate Neutral Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

Fastighets AB Balder. (2022). Globala hållbarhetsaktören Position Green väljer varvsstaden i Malmö för nytt kontor och powerhouse. Pressmeddelande, 25 Oktober 2022. Globala hållbarhetsaktören Position Green väljer Varvsstaden i Malmö för nytt kontor och powerhouse | Balder. Retrieved Apr. 9, 2024.

Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. (2017). The Circular Economy

– A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod., 143, 757–768.

Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Bleischwitz, R. Globalize the Circular Economy; Springer NATURE: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

Holden, M., Airas, A., & Larsen, M. T. (2019). Social sustainability in eco-urban neighbourhoods: Revisiting the Nordic model. In Urban Social Sustainability (1st ed., pp. 22). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315115740.

International Institute for Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Economic Sustainability. [Available online: https://www.iisd.org/topics/economic-sustainability].

Johansen, K.; Rönnbäck, A.Ö. (2021). Small Automation Technology Solution Providers: Facilitators for Sustainable Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP, 104, 677–682.

Josefsson, T.A. (2019). Form Follows Availability: The Reuse Revolution [Masters thesis, Chalmers University of Technology]. Chalmers ODR. https://odr.chalmers.se/bitstream/20.500.12380/257024/1/257024.pdf.

Jewitt, Carey. (2012). An Introduction to Using Video for Research. National Centre for Research Methods.

https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2259/4/NCRM_workingpaper_0312.pdf.

28

Kawulich, B. (2012). Collecting data through observation in Doing Social Research: A global context, pp.150-160, Editors: C. Wagner, B. Kawulich, M. Garner, Publisher: McGraw Hill.

Larsson, B & Wallström, U. (2005). Bo01, Hållbar framtidsstad – Lärdomar och erfarenheter. Formas, Stockholm.

Lövehed, L. (2005). Bo01, Hållbar framtidsstad – Lärdomar och erfarenheter. Formas, Stockholm.

Lund, C, et.al. (2007). Kulturhistorisk utredning. Varvsstaden – Kockumsområdet söder om Stora Varvsgatan. Fastigheten Hamnen 21:149 i Malmö stad. Skåne län. Enheten för Kulturmiljövård Rapport 2007:009.

Malmö stad. (2011). Planprogram Varvsstaden. Malmö stadsbyggnadskontor, Malmö.

Malmö stad. (2024). Bo01. Bo01 - Bo01 - Malmö stad (malmo.se). Retrieved Apr. 11, 2024.

Miljöbyggnad. (2021). Manualversion 3.2 i Miljöbyggnad släpps runt årsskiftet. Manualversion 3.2 i Miljöbyggnad släpps runt årsskiftet - Sweden Green Building Council (sgbc.se). Retrieved Apr. 29, 2024.

Miljöbyggnad. (2022a). Vad är Miljöbyggnad? Vad är Miljöbyggnad? - Sweden Green Building Council (sgbc.se) .Retrieved Apr. 26, 2024.

Miljöbyggnad. (2022b). SGBC lanserar Miljöbyggnad 4.0 – en ny generation av Sveriges mest använda hållbarhetscertifiering för byggnader. SGBC lanserar Miljöbyggnad 4.0 –en ny generation av Sveriges mest använda hållbarhetscertifiering för byggnaderSweden Green Building Council. Retrieved Apr. 29, 2024.

Moscati, A. 1981, Johansson, P. 1966, Kebede, R. Z., Pula, A., & Törngren, A. (2023). Information Exchange between Construction and Manufacturing Industries to Achieve Circular Economy: A Literature Review and Interviews with Swedish Experts. Buildings, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030633.

Naturvårdsverket. (2020). Avfall i Sverige 2020: Uppkomst och behandling [Report].

https://www.naturvardsverket.se/4ac5db/globalassets/media/publikationerpdf/7000/978-91-620-7048-9.pdf.

Nilsson, A & Elmroth, A. (2005). Hållbar framtidsstad – Lärdomar och erfarenheter. Formas, Stockholm.

Nordic Council of Minister. (2022). Nordic Council of Ministers Circular Economy in the Nordic Construction Sector: Identification and Assessment of Potential Policy Instruments That Can Accelerate a Transition toward a Circular Economy . https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1188884/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Persson, B (red.) (2005). Bo01, Hållbar framtidsstad – Lärdomar och erfarenheter. Formas, Stockholm.

Sager, T (2011). Neo-liberal urban planning policies: A literature survey 1990–2010, Progress in Planning, Vol. 76, pp. 147–199.

Swensen, G., & Granberg, M. (2024). The Impact of Images on the Adaptive Reuse of Post-Industrial Sites. Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 15(1), pp. 101–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17567505.2024.2311005.

29

United Nations Environment Programme. (2024). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction [Fact Sheet]. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/globalstatus-report-buildings-andconstruction#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20buildings%20were%20responsible,carbon %20dioxide%20(CO2)%20emissions.

United Nations Environment Programme. (2000). Glossary of environment statistics, studies in methods. United Nations Publications. [Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/environmentgl/gesform.asp?getitem=2].

Varvsstaden. (2024). Startsida | Varvsstaden.Retrieved Apr. 24, 2024. Varvsstaden AB. (n.d.). Idékatolog Återvinning, transformation/upcykling, underhåll och återbruk: En materialkompass för Varvsstaden [Catalogue]. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/vrkpsg46td74x4jbx5a8r/Varvsstaden_idekatalog_ 180405.pdf?rlkey=0argxxse1fts692u31kj160fd&e=1&dl=0.

Visit Stockholm. (2024). Hammarby Sjöstad. Hammarby Sjöstad - Visit Stockholm. Retrieved May. 14, 2024.

Wienerberger. (2023). Nu är Miljöbyggnad 4.0 här – vi har samlat allt du behöver veta. Nu är Miljöbyggnad 4.0 här – vi har samlat allt du behöver veta (wienerberger.se).Retrieved Apr. 29, 2024.

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford University Press. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-commonfuture.pdf.

IMAGE INDEX

• Fig. 1: Map of Case Study Areas within the Western Harbour in Malmö, Sweden; Rob Duncan

• Figs. 2 & 3: Bridge in European Village and View into House in European Village; Svea Anstis

• Fig. 4: Water feature in Bo01; https://www.neighbourhoodguidelines.org/quality-program-malmo-sweden

• Figs. 5 & 6: Solar energy technology Bo01; Svea Anstis

• Figs. 7 & 8: Industrial window in Gjuteriet building, and Facade of Gjuteriet building; Svea Anstis

• Fig. 9: Miljobyggnad logo; https://www.sgbc.se/certifiering/