THE AWAKENING

We would like to acknowledge the traditional custodians of the lands on which our editorial team and readers reside and pay our respect to any Elders past and present. We extend that respect to any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reading this publication.

Women’s Officer

Yang Yang Jiang

Editors

Elanah Sebastian

Gunni Kapur

Jeremy Wong (Meryl) Xiaomeng Liu

Publications Team

Aaryan Pahwa

Ashna Aravinthan

Teodulfo Jose Reyes

Ashna Aravinthan

Clara Athifa

Elanah Sebastian

Emma Taleski

Gabrielle Eivers

Nicolette Nair

Graphic Design

Grace Sun

Laura Elaine Lowe

Sofia Pastor

Dear Reader,

The UNSW Law Society invites you to step into the world of our first issue of 2025, The Awakening, which sheds light on the unspoken and the urgent, the hidden and the difficult.

What does it mean to awaken?

To awaken is to see with clarity what was once concealed by silence, custom, or convenience. It is to name what has long gone unnamed, and to question what we have been taught to accept.

Across these pages, we reflect on the structures that shape women ’ s livesthrough law, culture, media, or identity. Some pages confront injustice while others illuminate the complexities of navigating spaces that were never designed with us in mind. Each page asks us to reflect not only on the systems around us, but also on the internalised assumptions we carry.

They reject the notion that certain conversations are too niche, too uncomfortable, or too disruptive. Instead, they speak with urgency and strength, reminding us that real progress requires increasing the voices too often unheard.

The Awakening is not a singular moment, but a process of becoming more attuned, more courageous, and more committed to justice in all its forms.

We hope this issue invites you to reflect, to learn, and perhaps, to awaken something in yourself.

Thank you for joining us in this conversation.

Yang Yang Jiang and Elanah Sebastian

Red or Blue Pill?

Since I began writing this article in early April, I’ve had to update the number of women killed by domestic violence in Australia more than should be the reality. It stands now at a reported 24, coming to 4 to 5 women murdered each month – yet this reality is apparently all too easy to ignore. The least visible aspect of this within Western nations, but equally as dangerous, is how early seeds of violence are sown from a slow, normalised descent of mindsets and media that perpetuate with consequence as well as escalate the illogical norm of violence against women.

This issue of violence against women doesn’t erupt spontaneously. It’s shaped, reinforced, and released through often male–authored narratives that begin in seemingly harmless childhood consumption of their world and persist through adolescence into adulthood. The appropriate phrase that comes to mind being “it's only illegal if you get caught,” or a claim of plausible deniability. It's in fact this apparent lack of accountability which allows this progression.

The media plays a critical role in this continuum, conditioning us to either confront or ignore what’s in front of us. It's the audience’s general consensus of whether they swallow the red pill to see the truth, or whether they opt for the blue; remaining blissfully blind. This, interestingly enough, shifts based on factors including the time of these productions, the demographics of the shows themselves, or whether their love for the content outweighs their care for inhumane treatment.

The earliest messages children receive about gender roles often come via screens. Cartoons, commercials, and kids' films regularly depict passive, decorative female characters or reinforce ideals where dominance equals masculinity. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children exposed to repeated media violence are more likely to accept it as a natural means of problemsolving. These early ideas may seem trivial, but they form the foundation for adult attitudes that rationalise control, entitlement, and ultimately, abuse.

Teen dramas such as Euphoria and 13 Reasons Why claim to tackle heavy topics, but they walk a precarious line between awareness and exploitation. While they aim to illuminate issues like assault, addiction, and emotional manipulation, they also risk glamorising trauma. Much of this in the later case is born more of the audience reception of it, as in Euphoria, for instance, they draw upon the cinematography to stylise suffering to the point that viewers become voyeurs rather than advocates. We must ask ourselves: are we watching to understand, or simply to be entertained?

In contrast, the more recent Netflix series Adolescence offers a more grounded and unflinching portrayal of violence and its roots in toxic masculinity. The series is unfortunately unique in avoiding the sensationalism that often accompanies portrayals of violence. Instead, it delves into the psychological and societal factors that contribute to such acts, and only serves to unnerve audiences. Particularly focusing on the influences of digital culture and the normalisation of misogyny to explain the lead’s thinking, yet the series does not romanticise or glamorise the violence; rather, it presents it as a chilling reflection of contemporary issues.

However, the series' impact is complicated by its male creators. The fact that a story about male violence against women is told primarily through male voices raises questions about whose narratives are prioritised and who gets to define the discourse around such critical issues. This dynamic underscores the broader societal tendency to engage with topics of gendered violence only when they are mediated through male perspectives.

In this context, Adolescence serves as both a compelling narrative and a mirror to our cultural blind spots. It challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about the roots of violence and the systems that perpetuate it, urging a deeper examination of how we consume and respond to media portrayals of gendered harm.

Game of Thrones is frequently defended by fans and creators alike for its “historical realism.” An odd argument, considering the world it built is filled with dragons, ice zombies, and resurrection magic. And yet, this fantasy setting has been repeatedly used as cover for its graphic depictions of sexual violence, often against women. In its early seasons especially, the show relied heavily on rape, coercion, and nudity to "drive" the plot forward. But critics and scholars have noted that these scenes were less about narrative necessity and more about shock value and being gratuitous, stylised, and ultimately normalising violence against women. Is it not telling that these are what's used to provide that at the expense of women? Almost as though the directors and audience are able to live out a kind of ‘fantasy’ without consequence.

In one of the most notorious examples, Daenerys Targaryen’s wedding night is portrayed as a consensual union in George R.R. Martin’s novel. Within the onscreen adaptation, however, it was rewritten into a violent rape scene. Emilia Clarke later revealed she felt “terrified” and “completely overwhelmed” during the shooting of nude scenes in the first season. She also spoke publicly about feeling pressured into doing full nudity as a young actress, despite growing increasingly uncomfortable with it as the show progressed.

This is not a one-off occurrence. Other actresses on the show, such as Sibel Kekilli, were subject to invasive questions about their pasts, including Kekilli’s history in adult films, which were often weaponised to discredit and objectify her further. Meanwhile, scenes involving sexual violence were often written and directed by male showrunners and directors, and disregarded by the audience during the later seasons when the actresses spoke up on account of the show’s traction. It’s most telling that later in the series, when Clarke was able to assert more creative control, the nudity all but disappeared.

This use of pseudo-historical context to justify brutality against women isn’t unique to Game of Thrones. Other popular prestige shows follow a similar pattern. Outlander, for example, while praised for its female lead and occasional inversion of the male gaze, also includes repeated scenes of rape and torture, some of which verge on exploitative. Claire, the protagonist, is subjected to sexual violence and constant physical danger across the series, but it’s often framed in ways that feel voyeuristic rather than necessary.

Likewise, Vikings, The Tudors, and even Rome portray, accurately enough so, medieval or early modern societies as inherently violent, misogynistic playgrounds. Yet its explicit scene portrayals to the extent seen on these shows must be called into question. It becomes where women’s suffering for the sake of “the plot” is not only inevitable, but seemingly required to legitimise the world’s “grit”, and often it becomes a larger issue as characters perpetuating this are shown in positive lights. Many of the acts of violence shown weren’t necessarily historical realities but narrative choices; ones shaped by contemporary assumptions about gender, power, and what audiences are expected to find compelling. 9

The problem isn’t necessarily the depiction of violence itself but that this violence is so often unexamined, aestheticised, and dished out primarily to female characters, with little consequence to the male ones enacting it. These women are rarely given meaningful arcs that allow for justice, agency, or healing. Instead, the violence becomes a shortcut for drama, a tool to deepen male characters, or a spectacle to keep viewers hooked.

When rape is used repeatedly as a dramatic device without examining its emotional or systemic consequences, it’s no longer storytelling, it’s voyeurism. It's become the consumption of performative pain as opposed to watching trauma unfold.

This is where the "historical realism" defense becomes so hollow. These stories aren't bound by history, they’re shaped by who holds power in the writers’ rooms and on set. In many cases, a medieval setting becomes an aesthetic shield that permits and perpetuates fantasy violence, fantasies that disproportionately target women’s bodies. It allows creators to disavow responsibility, hiding behind swords and corsets while enacting contemporary misogyny in high-definition.

If anything, these shows reveal less about the past and more about our present, a media landscape still enthralled by the spectacle of violated women, still more interested in titillation than truth, and still unwilling to ask why so many of these stories are told at women's expense.

What happens when women tell the story? Shows like I May Destroy You and The Handmaid’s Tale offer a counter-narrative. Both, created by female directors and writers, effectively dissects trauma and consent with nuance and emotional truth; but it didn’t receive nearly the same mainstream embrace or viewership as its male-directed counterparts. This is the common theme amongst female-authored stories that center women’s pain without fetishising it. Often being labeled “niche” or “heavy,” while male-authored brutality is deemed “bold” or “prestige television.” Regardless of the content of these productions being such, entertainment is preferred over understanding.

The stories we consume are shaped long before they reach us, often in writer’s rooms where power is unequally distributed. In 2024, women comprised only 37% of TV directors, and fewer still were women of color. When the storytellers lack diversity, so too do the stories. If women’s voices aren’t valued behind the scenes, how can they be authentically represented on screen?

It’s easier to believe that things are getting better. That “we’ve come so far.” This blue-pill thinking congratulates progress while quietly accepting the status quo. It allows people to consume problematic media guilt-free, to dismiss discomfort as “just fiction,” and to frame violence as plot thickening rather than a challenge or reflection of real-world systems.

We stand at a crossroads. One pill lets us stay comfortably sedated by familiar stories and familiar power structures. The other demands that we see the violence not just on screen, but in the systems that create, package, and profit from it, and further into the broader issues of violence against women it encourages. While the choice exists, the reality remains that the media we watch, and accept, reveal more about our developmental thinking than often realised.

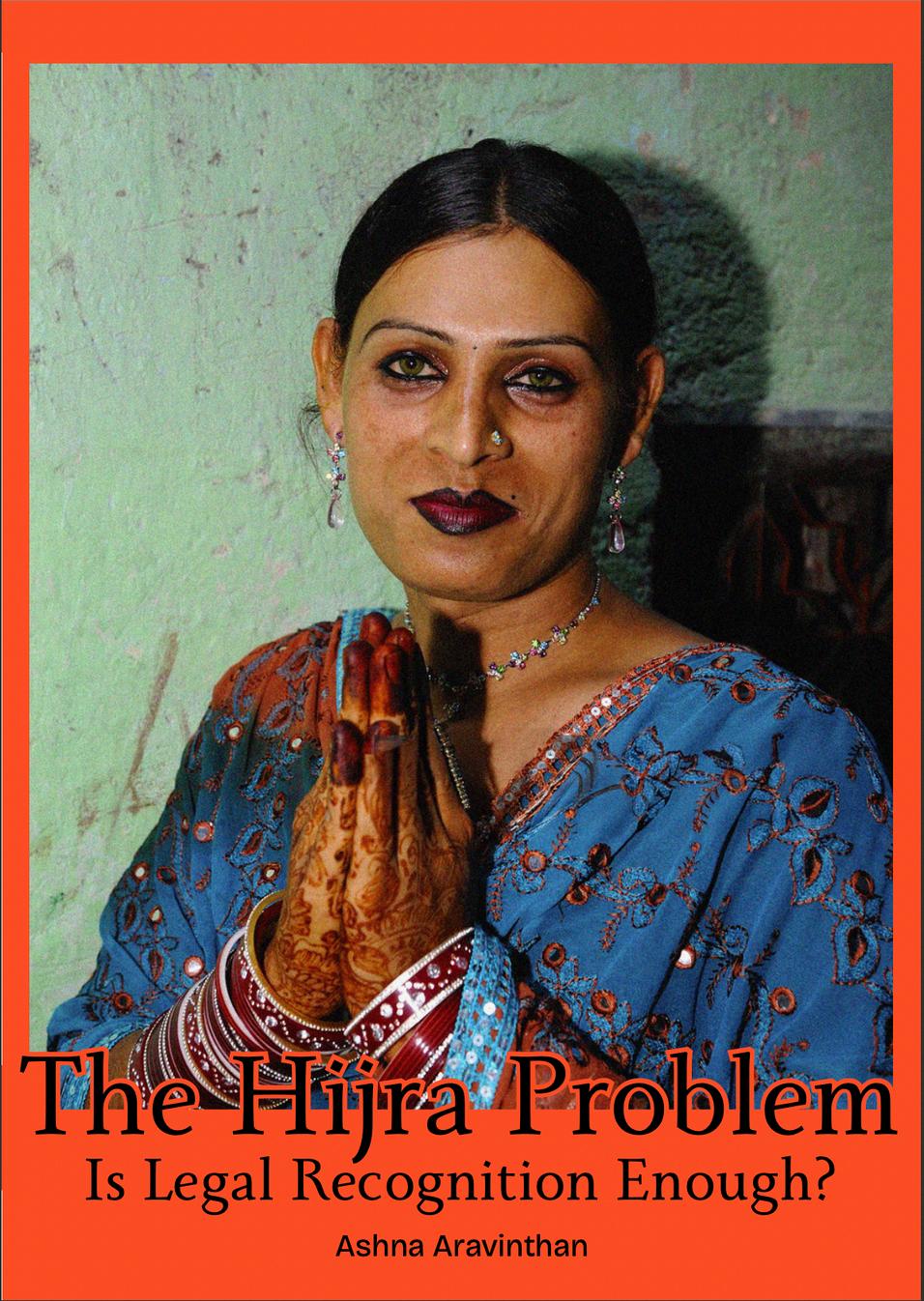

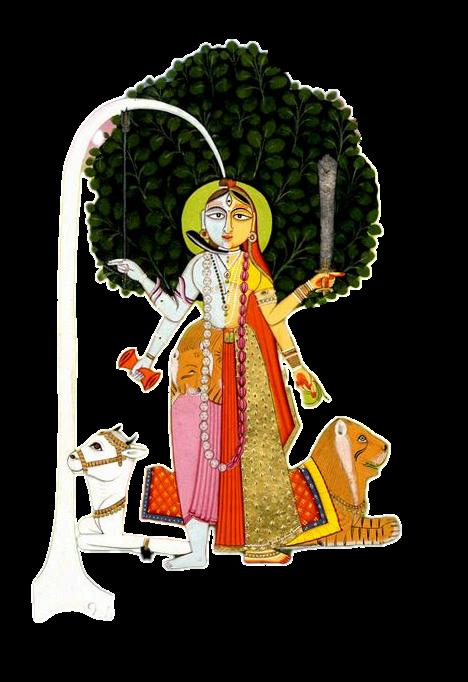

Since their emasculation was believed to bring them closer to the divine, hijras gained the right to conduct badhai, performances of song and dance conducted during births and weddings, intended to bless the family during the auspicious times when male and female genders were most nondifferentiable.

Hijras continued to enjoy their foundational trust within Indian society until the 18th century9, when the British East India Company shifted their focus to politically asserting dominance rather than simply trading1 0 In the late 18th century, every mention of the hijra by Europeans debased their very existence; as physical reminders of possibilities outside of the gender binary, hijras were described as “disgusting objects” and “an outrage to morality”. 11 As Indian subjects gradually gained access to the debates informing European intellectual politics in the early 19th century,1 2 they quickly began doubting their own cultural beliefs. Surrounded by a mass of derogatory writing from European settlers, the hijra’s social status began its decline

A hijra panic broke out in the mid 19th century, heralded by the 1852 case of The Government v Ali Buksh. The case concerned the murder of Bhoorah, a hijra who was found dead with her head completely severed. Her ex-husband was the clear suspect: she had left him for another man shortly before her death, and neighbours had seen the pair arguing on the very day she died Yet the fact that the victim was a hijra, rather than a biological female, jarred the court. Her innocent decision to leave her husband was painted as evidence of prostitution - and then, rather than expressing any concern for Bhoorah, the court’s judgment convicting Ali spent an inordinate amount of time detailing their views on the hijra community, portraying all hijras as sexually deviant prostitutes because of their baseless assumption that Bhoorah had been unfaithful

Unfortunately for the hijras, from this point on they became a symbol for the assertion of British superiority The British fabricated “a process of reform through which Christian doctrines might collude with divisive caste practices”,1 3 to induce partial reform such that even if India tried to emulate the British, their mimicry would always be plainly visible

Jessica Hinchy, ‘The Sexual Politics of Imperial Expansion: Eunuchs and Indirect Colonial Rule in Mid-Nineteenth Century North India’ (2014) 26(3) Gender & History 414, 414

Jessicy Hinchy, Governing Gender and Sexuality in Colonial India (Cambridge University Press, 2019) ch 1 28-29 (‘Governing Gender’)

Ibid Ibid

Homi Bhaba, ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’ [1984] 28, Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis 125, 127

There is now a doubling of mimicry; the Western “homoempire” 15 today asserts superiority in its normalisation of homosexuality in comparison to South Asia’s perceived backwardness, completely ignoring its own role in engendering this very backwardness

It is only recently that India has finally begun to grapple with the continued marginalisation of hijra peoples. In National Legal Services Authority v Union of India (2012), the Indian Supreme court ruled that hijras should be recognised as a specific third gender, and that this third gender could be self- determined, as opposed to biologically assessed. This was an enormous first step in formally breaking down rigid gender structures In the subsequent decision of Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India (2018), the court explicitly read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which had been interpreted as criminalising sodomy for almost 60 years. Instead of automatic criminalisation, the court stated that any act between two consenting adults, regardless of their sex, could not be considered “intercourse against the order of nature”. 16 Further explicit protections of transgender peoples, encompassing hijras, were then enacted in the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019. But, for all the court’s ramblings on the paramount need to uphold the human rights of hijras just as much as any other social demographic in India, the Protection of Rights Act does little to protect hijra rights in practice. The maximum penalty for disobeying the Act is 2 years’ imprisonment - nothing compared to the physical, psychological and emotional harm that hijras experience. 17

Although no qualitative studies have been conducted in India specifically with respect to the effect of legal recognition on hijra lives, several have been conducted in neighbouring countries Pakistan and Bangladesh, who also legally recognised third gender status by 2014. Regardless of their legal rights, hijras are consistently refused healthcare, jobs, and community support - but since these can be respectively justified by the hijra’s sex work or HIV status, illiteracy, and mere personal beliefs, little to no action is ever taken in response.1 8 Hijra sex workers recount the harrowing experiences of locking themselves inside their rooms to avoid people with criminal backgrounds who demand sex, and if refused brandish guns to get their way. Even when police are called, there are very few follow-ups or investigations conducted; the unfortunate irony is that many hijra clients are police themselves.1 9

Ahmad Qais Munzhaim, ‘LGBT Politics in South Asia: Ground Rules, Underground Movements’ in Michael J Bosia (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Global LGBT and Sexual Diversity Politics Indian Penal Code (India) 1860, s 377

The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2019 (India), ch VIII. Alamgir Alamgir, “‘We Are Struggling to Seek Justice’: A Study of the Criminal Justice System and Transgender Experiences in Pakistan” (2024) 25(2) International Journal of Transgender Health.

Even if they don’t follow the avenue of sex work, their poverty often bars them from access to gender-affirming surgeries, such that their castration is often violent and unsanitary. Despite legal recognition, a lack of respect permeates how hijras are treated even within institutions built to uphold the community.

The divided subaltern who is more concerned with the goings-on of those below them than their repression has been duplicated as India’s queer community becomes more welcoming in line with Western ideologies Other trans people in India have made it clear that they do not want to be associated with the hijra, who symbolises poverty, dirtiness, and sexual deviance.2 0 The upwards mobility of the queer lifestyle, now a symbol of middle-class freedom, seems to necessitate grinding the hijra into the dirt. It is true that hijras and trans people are not equivalent, but the parallels in their struggles and experiences would suggest some affinity. It is the continued illusion of a subaltern class, embedded into Indian society by the routine of English colonial mimicry.

Once that illusion breaks, the Indian population must face their continued subalternity under the European gaze. Hijras are already unapologetically performing and affirming their own gender identity day in and day out on the streets of India, but under a Western framework their gender expression is rendered invalid simply because of their ‘unconventional’ traits. It is important that India’s queer population, and even more generally the wider Indian population, consider how to work with pre-existing narratives of queerness in India, rather than succumbing to the West’s supposedly universal ideas.

Liz Mount Flagler, “I AM NOT A HIJRA: Class, Respectability, and the Emergence of the ‘New’ Transgender Woman in India” [2020] Gender & Society

As a child full of voice, I knew how to speak with conviction, ask questions until my curiosity was satiated, and speak up for my friend when things felt unjust. For as long as I can remember, this voice of mine was often met with a familiar mantra: “You would make a great lawyer, Clara…”

But this remark was not always an endearing testament to my precocious and outspoken nature. Rather, it was a script to confine my big personality into a box shaped by people’s stereotypes of what it means to be a lawyer - arrogant, pretentious, and overbearing. As if intelligence, assertiveness, and leadership in girls can only be expressed within the tight parameters of law; as if it is the only place where girls like me could exist without being told to quiet down.

And yet, if the same confident child was born and raised as a boy by only a stroke of luck, he would not be considered sassy, but sharp; not opinionated, but ambitious. He would be told that he would make a successful CEO, a talented athlete, an

influential politician - his options limitless. While the outspoken boy is groomed for greatness, his equal counterpart is directed down a onesize-fits-all path, just because she is a girl.

So, by the time we reach law school, we carry a lifetime of coded compliments. We have been taught that our voices are only welcome when carefully packaged - not too dramatic, not too bossy, and never too much. By the time we step into CATS rooms and

law offices, we arrive moulded, having mastered the art of subtle shrinking by lowering our hands as quickly as we raised them, starting sentences with “I’m not sure, but…”, and speaking with opinion but not too much power. We cushion our confidence with apology, dilute our assertiveness to avoid being labelled difficult, and learn to carefully tread the line between being opinionated and being tolerable. Once we reach adulthood, we have already internalised the rules of a game that was rigged against us from the beginning

Unlike her male peers, she is not just trying to succeed, but to justify her presence, forced to excel for the sake of being taken seriously. In traditional law school fashion, where competition is fierce and prestige is currency, the outspoken girl becomes the overachieving woman. While she treads water to stay afloat, the men around her are watching from the shore’s solid ground, dry and untouched This disparity is not imagined. It manifests when women are given more confidence -

focused feedback in competitions, told to speak with a deeper, louder voice, even when their performance matches their male counterparts. It manifests when women are told to smile more at work to appear “approachable,” while men are applauded for their stoic professionalism and gravitas. It manifests when women who speak up in class debates, unwavering in their opinions and morals, are seen as aggressive and domineering while the same behaviour in men is seen as confidence and intellectual capability. These slights, while subtle and casual, accumulate to reinforce an exhausting truth: while the law may suit outspoken girls, it does not yet know how to reward us without condition. And what becomes of this inequity is that women ’ s achievements are attributed to luck, hard work, and good organisation, rather than our intellect, skill, and leadership As if diligent rather than brilliant; driven rather than talented. Even when we stand at the top of the class or hold positions of leadership, there remains the unspoken need to prove, again and again, that we deserve to be there That we are not just a diversity statistic, a token, or an exception. We are praised not for breaking the mould, but for fitting neatly into it.

And because the road to the top is rocky and fraught with fire and resistance, we continue to celebrate women for being the first - first female partner, first woman-of-colour judge, first woman president. These milestones are often framed as moments of progress, and in many ways, they are. They honour resilience, persistence, and the ability to break through centuriesold barriers. But behind every “first,” is the fact that she had to carry the weight of proving not just her own worth, but the worth of every woman who might come after her. She carries the burden of representation –expected to succeed not just for herself, but as proof that women, as a whole, are worthy of the space she occupies

Her triumph is seen as evidence that the system is changing, even when the structure beneath her feet remains fundamentally the same. Her presence becomes a milestone, something exceptional and novel While it is wellworth celebrating, true triumph will only be achieved when our presence is no longer viewed as historic, but something that is rather unremarkable, unapologetic, and undeniable. The goal was never to be the only one, or even the first – it was to ensure she would not be the last. Because only then does her success become a pathway, not a pedestal. When we clear the path for others, when our stories are no longer rare but one of many, when our presence no longer makes headlines because it has become the norm. Only then will the struggle have served its purpose – not to spotlight one woman, but to open the floodgates for all. It is then when we can say that the fire they walked through was not done in vain

And so, a solution begins quietly, in the way we speak to the loud girl in the classroom, the stubborn girl at the dinner table, the curious girl who won’t stop asking “why?”. When we tell her she’s too much, we teach her to shrink. When we call her bossy, we dull her leadership. We must speak to her with belief celebrating her voice, backing her boldness, and reminding her that her much-ness is a gift, not a flaw. If we can raise a generation of girls who know they are powerful before they are demanded to prove it, perhaps we will no longer need to celebrate them for being the “first”. Instead, we will be building a future where we can celebrate them for being one of many.

Once upon a time, There lived a little girl with long raven hair, hair that shimmered like ink in sunlight. Since she could remember, her father told her she would one day marry a handsome prince. And that she would make compromises for his happiness

When she turned fifteen, her father married her to the finest prince in all the land, Whose vows read:

“I will shower you with all my riches in my most eligible palace.

Just you and I, Till death do us part.”

In a land far, far away, nestled in the Indian Ocean, sat a humble island

A tear-shaped drop of land.

Beautiful and resilient, its people had no idea that its very soil bore the roots of deep-seated traditions, woven through patriarchy and silence.

The soothing reality blanketed the imperturbable atmosphere, as the joys of children resounded through the crumbling walls of poverty. Their innocent laughter, contagious. Their delight, unspoiled by what they did not yet know.

Inside a modest home, morning sunlight spilled in through an open window

The sky was a canvas of a child's dream, brushed with coral pinks and honey oranges.

A mother sat on a worn wooden stool, handcrafted by the husband chosen for her. Her daughter sat before her as the sun’s rays reflected off her luscious hair, filling the humble multipurpose room with a haze of wonder and endless possibilities.

Wrapped around her worn shoulders, her mother wore her nicest fern saree. Mended with her bare hands, rewashed, and patched until it frayed at the edges. Today, she folded ivory mai petals into her daughter’s plait.

“Ouch, Amma! That hurts!”

“Not Archie’s oil again. It stinks!”

“Kasun pulled my plait again!”

The daughter’s voice floated like silk. Her skin glowed bronze in the sun, but it was her hair that caught whispers of the village. Like midnight woven into strands, gleaming with its own light

She was fifteen. Slim, joyful, wild.

Dressed in a scarlet reddi and hatti, sewn from scraps of her mother’s old sarees, she chased her brothers through the street.

The grass was dry and prickly, but her laughter rose louder than her father's warnings not to leave the house in her good clothes.

A majestic peafowl appeared. Its cobalt chest puffed. Its iridescent tail fanned wide. She stared, captivated, while it danced for her

“Come here!” her father barked. She ignored him. She was wrapped in wonder, the kind only children know.

“I said, come here!”

Still, she laughed Her joy was defiant Untameable

A man stood proud, his voice smooth, his presence towering over her. Her father gestured proudly.

“This is my daughter. She is yours.”

She blinked, her eyes burning. Her jaw fell. Her stomach twisted into knots

“You are to marry him.”

Every bone in her fragile body froze. Her silence was heavy.

“

“It’s a blessing You’ll lift us from the slums ”

“You’ll do it for us. ”

And with that, he shoved her into a rickshaw with a creature she did not know.

The rickshaw sped away. Her glistening mane caught the wind, tangling in the wheels as strands scattered, leaving a trail of prayers and sorrow across the pavement.

They arrived at an ever-growing tower. No palace at all, but a tall, hollow rook that appeared majestic from afar but loomed like a sentry up close.

Cold Immaculate Lifeless

Her eyes scanned every crevice. It was every little girl’s dream to live in a palace. She ignored the shadows clinging to its walls. No sunlight reached its windows. No breeze rustled through the curtains

No laughter filled the air.

Still, she stepped forward. Daughter no more, Now His wife.

Servant Housemaid. Prisoner.

Her husband had left, but the tower remained. A home turned mausoleum

Daylight never entered. The windows remained sealed

The world was locked away Or was she locked away from the world?

She cooked She cleaned The walls closed in, coffin-like. The concrete scratched her skin with every slight move Hope lingered only in the outskirts of her mind. Dim.

“Let me out!” she would scream. But no one heard

In her mind, the tower crumbled each day She fell, over and over again. No escape. No rescue.

The clouds swallowed the sun. And in the end, she remained Married not just to the prince, But to her sacrifice. To a fate she never chose Time passed She grew older.

But each time she looked for her freedom, She saw only darkness. Only that first moment of betrayal

The clock in her head ticked, ‘The End’. The past grew heavier, the future receded Possibilities decreased and regrets mounted.

Her luscious midnight hair stiffened into ash. Her mind wore thin.

I've always loved the law, but I’m not sure I'll make a good lawyer.

I love its clarity. Its rules. The promise that reason, fairness, and consistency in application hold power in a world that too often is messy, complicated, and incoherent. I thought that law is about how you think, problem-solving, and creativity. I thought that it was about applying the rules and finding your answers. I thought t That what matters was how you make your argument, not how loudly you speak.

But the more I immerse myself in the field of law, the more I realise that the legal system doesn’t just reward logic. It rewards theatrics. It expects lawyers to command attention, to make eye contact, to modulate their voice and their tone just enough to sound confident, but not aggressive. It favours a courtroom swagger that signals credibility long before the facts are weighed. It asks us to play roles, like actors, not just make arguments.

For neurodivergent women, it feels like a rigged game.

Class participation grades value your ability to be prepared. It involves not only reciting verbatim from the textbook, but being able to expand on the readings, and bounce off classmates with collected thoughts and confidence. Anxiously reciting the facts or issues verbatim in a monotone, with eyes fixed on the flickering ceiling lights, is frowned upon. Cold calls are like having a bucket of ice water dumped over your headare the enemy. I have found that it is not enough to know and analyse the law. Confidence matters almost more than accuracy.

Networking events and clerkship cocktail night. Partners glide past in sharkskin suits, rating students on handshake firmness, breezy chats about Sydney public transport and Martin Place food options. It seems easy and natural to them, but my brain tabs through smalltalk scripts. Meanwhile, I am being constantly overstimulated by the tag of my blazer rubbing on my neck, how to be sophisticated and eat canapes while discussing the latest Supreme Court cases, how much eye contact is too much eye contact, and, if you’re not making eye contact, where the hell are you supposed to look? My interviewing skills, practised and rote learnt with my mother, are not enough. Even if my networking “skills” somehow translate to a successful social interaction, I must keep up that exact mask and personality every single time I engage with these cohorts. It is exhausting.

However, one thing becomes clear: law firms buy charisma first. Passion and knowledge come later

Before I even reach the workforce, there's psychometric testing. Abstract reasoning, timed pattern-matching, maths, facial expression recognition tests, forced-choice personality inventories that demand I rank whether I’m “more empathetic or efficient,” as if the two cannot co-exist. These tests are pitched as objective and bias-free, yet they measure conformity to neurotypical norms: speed over reflection, instinct over logic, and likability over nuance. For neurodivergent women, being slow to choose when the options simply don’t make sense becomes the first, quiet exclusion. No feedback, no appeal. Just a “no longer under consideration” email in your inbox.

And then there’s the courtroom. I’ve learnt that stepping into a courtroom as a lawyer isn’t just about knowledge, it’s about performance. You need to speak with confidence, project certainty, and command the room Make eye contact with judges, read the jury, track the opposing counsel’s argument, know exactly when to pause, concede, press, and object. But neurodivergent women are told we’re “awkward” because we don't look you in the eye, or “intense” when we care ‘too much.’ We’re too blunt, too intense, too emotional, or not emotional enough The courtroom requires a performance that just isn't in our repertoire.

Sometimes, presenting your case is about being confidently wrong Arguing the loopholes in the law, or against what is ‘just’ and ‘fair.’ Yet justice isn’t simply a concept to neurodivergent women; it’s a moral imperative hardwired into how we think, feel, and act. It’s ‘black and white thinking’ that results in an inability to sway from what is ‘just’ And contrary to some stereotypes about neurodivergent women, some don’t struggle with empathy; some struggle with turning it off. I want to believe that caring about justice, about your client, about what is ‘right’ and ‘fair’ and following the rules of the law, isn’t a weakness, and shouldn’t make me a “bad” lawyer I don’t believe empathy should be severed from advocacy. Shouldn’t caring be the minimum, not a liability?

Neurodivergent traits aren’t flaws They should be considered strengths that the legal system needs. Maybe my minimal class participation means I’m not simply proving I know more than others, but that I’m processing, thinking, applying, and questioning My awkward presentation at networking events shouldn't mean I must be incompetent, but rather that I’ll care more about achieving goals than hour-long coffee “meetings” or watercooler chats. The wobbles in my voice when I'm arguing my case mean I know it's worth it; it's an exercise in seeking justice. My unwavering, black-and-white sense of justice hardwires my passion, my drive to make a difference, to fix a broken system.

If neurodivergence disqualifies someone from being a good lawyer, maybe it’s not us who need to change Maybe the profession needs to change what “good” is. Without challenging these facets of the legal profession, neurodivergent people will remain not just burnt out, exhausted from forcing ourselves to ‘mask’ and mimic neurotypicals, but also excluded Challenging these “flaws” may mean more neurodivergent people can engage in the system that is so often against us It may mean being able to give more, bring our passions, our attention to detail, our different ways of thinking, so that together we can create new solutions.

I’ve always loved the law, but maybe being a good lawyer isn’t about fitting in. Maybe it’s about caring too much to let things stay the same

By Nikki Nair

The ability to make one's own decisions and live independently, free from coercion or undue influence, is a fundamental human right. This includes the right to self-determination, which is enshrined in key international instruments such as Article 1 of the United Nations (UN) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Article 1 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. However, political regimes and religious influences can often restrict this inherent human right by shaping laws and regulations. Notably, reproductive rights are implicitly protected under the UN Convention to Eliminate Discrimination against Women. Despite this, the question remains: why has autonomy over women’s bodies been the subject of intense political and social debate for so long?

Reproductive rights in Australia have evolved over the last 50 years, with significant legislative and social changes, albeit at a gradual pace. In 1972, during the Whitlam government, the 27.5% luxury tax on the contraceptive pill was removed and it was included in the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, significantly reducing its costs and increasing its accessibility to a broader population.1 Initially, the pill was only available to married women with a prescription, reflecting the prevalent social and religious values of the time.2 Implying that sexual freedom and the ability to prevent pregnancy were only acceptable within marriage.

The history of abortion laws in Australia is similarly complex. The medical procedure that deliberately terminates a human pregnancy to provide women with agency over their bodies, especially if their health is of concern, was explicitly treated as a criminal offence in NSW for much of the 20th century.

‘The Pill’, National Museum of Australia (Web Page, 18 September 2024) https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/the-pill.

2 Ibid.

Women who sought abortions and those who assisted them faced severe criminal penalties. However, the landmark 1969 ruling in the Victorian Supreme Court, known as the ‘Menhennitt ruling’,4 established that abortions could be legally performed if necessary to preserve a woman's physical or mental health.5 This precedent was later followed in NSW,6 which permitted abortions where there was an ' economic, social or medical ground or reason' upon which a doctor could base an honest and reasonable belief that an abortion was required to avoid a 'danger to the pregnant woman’s life or her physical or mental health'.7 Despite these legal rulings, abortion remained under the Crimes Act as a criminal offence until the early 2000s.

The decriminalisation of abortion in all Australian states between 2002 and 2019 marked a monumental shift in reducing the stigma surrounding the medical procedure. These laws, such as the Abortion Law Reform Act 2019 (NSW),8 removed abortion as a criminal offence under the Crimes Act and introduced new legal provisions to regulate abortion as a medical procedure. Additionally, those going to abortion clinics in NSW were only provided with a 150m safe access zone as recently as five years ago.9 While these legal victories are monumental, they reflect a sad truth. It took almost 50 years, half a century, of immense activism and public struggle for women to reclaim their reproductive rights. The pace at which these advancements have occurred is deeply disheartening.

Despite advancements, reproductive rights in Australia remain vulnerable. The 2022 overturning of Roe v. Wade in the United States serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of reproductive rights globally.10 This ruling effectively abolished the constitutional right to abortion in America, triggering concerns of the potential regression of reproductive freedoms worldwide. In Australia, while abortion has been decriminalised, there are concerns that similar movements and anti-abortion groups are still actively attempting to wind back 50 years of progress.

3 Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) ss 82–4.

4 R v Davidson [1969] VR 667.

Bronwyn Naylor, ‘Judge-Made Law: The ‘Menhennit Ruling’ and Abortion Law Reform in Victoria’ [2017] 88(1) Victorian Historical Journal 97, 97.

6 R v Wald (1971) 3 DCR (NSW) 25.

‘Abortion Law Reform’, Community Legal Centres NSW (Web Page, 11 March 2020) https://www.clcnsw.org.au/policy/abortion-law-reform.

8 Abortion Law Reform Act 2019 (NSW).

9 Public Health Amendment (Safe Access to Reproductive Health Clinics) Act 2018 (NSW)

10 ‘Roe v. Wade and Supreme Court Abortion Cases’, Brennan Center for Justice (Web Page, 28 September 2022) https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/roe-v-wade-andsupreme-court-abortion-cases.

For example, in 2017, NSW MP Fred Nile proposed a ‘Zoe’s Law’ bill in the NSW parliament,11 designed to grant legal personhood to fetuses. The bill sought to criminalise any harm to a fetus as grievous bodily harm. Had the bill been passed, it would have severely restricted access to abortion services by complicating the legal framework. Those who underwent an abortion, or even medical practitioners, could have been criminally liable. Fortunately, the 2017 bill was not passed; however, this highlights the ongoing battle over reproductive rights in Australia and the anti-abortion sentiment that continues to exist within our society.

Another attempt to wind back progress was seen in 2019, when antiabortion groups in Victoria and Tasmania attempted to challenge safe access zones around abortion clinics.12 To combat this, the Human Rights Law Centre and Melbourne Fertility Control Clinic, represented by Maurice Blackburn Lawyers, brought this matter to the High Court and ultimately succeeded. The High Court upheld the current safe access zone laws, reinforcing the need to protect women from harassment and intimidation. While this 2019 High Court ruling was a significant victory, it also served as a critical reminder that there continue to be constant challenges to the protection of reproductive rights, due to contrasting perceptions of women's rights within society.

While the legal landscape for reproductive rights has improved, disparities remain, particularly in rural and remote areas. Australia’s fragmented system, with each state implementing its laws and regulations, has created a ‘postcode lottery’, as described by Jamal Hakim, Managing Director of MSI Australia (the national provider of abortion services in Australia).13 This system leaves many women, particularly those in rural and remote areas, facing substantial barriers in accessing abortion clinics or reproductive healthcare, including physical distance and costs such as transportation and accommodation.

Crimes Amendment (Zoe's Law) Bill 2017 (NSW). See also ‘Foetal Personhood Bill (“Zoe’s Law”)’, Women's Legal Service NSW (Web Page) https://www.wlsnsw.org.au/law-reform/pastcampaigns/zoes-law/.

Luke Cooper, High Court of Australia Upholds Abortion Centre Safe Access Zones for Women in Victoria and Tasmania’, NineNews(Web Page, 10 April 2019) https://www.9news.com.au/national/news-australia-abortion-centre-safe-access-zones-womenvictoria-tasmania-high-court-ruling-challenge-knocked-back/55bdb858-66e2-4490-9750abc09c02bf31; Australian Communities Foundation, Protecting Reproductive Rights in Australia: Update from the Human Rights Law Centre (Web Page, 2021) https://www.communityfoundation.org.au/article/human-rights-law-centre-reproductive-rights/; Dom O'Donnel, ‘Defending Reproductive Rights’, Human Rights Law Centre (Web Page, 2025) https://www.hrlc.org.au/projects/repro-rights/.

Angela Zhang, ‘Abortion Rights and Access in Australia: Implications of Roe v Wade’ Australian Human RIghts Institute (Web Page, 2022) https://www.humanrights.unsw.edu.au/students/blogs/abortion-rights-access-australia-roe-vwade.

Exacerbating these barriers is the fact that most public hospitals do not offer abortion services, creating ‘abortion deserts’.14 The current laws in place permit this; for example, the Abortion Law Reform Act 2019 outlines that public hospitals in NSW are not required to provide formal abortion services. As a result, only 3 out of NSW’s 220 public hospitals routinely provide abortions, forcing many to travel to those three specific hospitals or to incur out-of-pocket costs for the private clinics that do offer them.15 This geographic disparity is accentuated by the fact that currently only approximately 10% of general practitioners in Australia are registered to prescribe medical abortion, and large areas of rural and regional Australia have no GPs offering this service.16 This lack of access can have dire consequences for women seeking timely care.

However, one promising initiative to address this gap is the ORIENT Study, led by PhD Candidate Jessica Moulton, with the help of rural and regional nurses, GPs, and patients.. This study, which commenced in 2024 and is due to finish in 2025, is designed to help elevate the role of nurses in contraceptive and medical abortion care in rural and regional areas, where unintended pregnancies are more prevalent.17 This study essentially tests a nurse-led approach to reproductive healthcare in rural areas, including the provision of Long-Acting Reversible Contraception insertion and medical abortions. By training nurses to provide these services, the study aims to reduce the barriers of geography and accessibility, offering a more equitable solution for women in underserved regions of Australia.

Additionally, the Greens’ proposed Abortion Law Reform Amendment (Health Care Access) Bill 2025, introduced by Upper House Greens MP Amanda Cohn, aims to expand women's access to abortion by allowing nurse practitioners to supply medication to terminate pregnancies, up to nine weeks' gestation.18 The proposed bill also attempts to ensure that abortion services are provided across the state within a reasonable distance of residents’ homes, and that information about access is publicly available, to avoid the so-called ‘abortion deserts’. The amendments to the bill also

14 Ibid. 15

16

17

Melissa Davey, Nick Evershed and Donna Lu, NSW Abortion Deserts: Just Three of 220 Public Hospitals Provide Terminations, Research Finds The Guardian (Web Page, 17 December 2024) https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2024/dec/17/nsw-abortion-deserts-just-three-of220-public-hospitals-provide-terminations-research-finds.

Marie Stopes Australia, Situational Report: Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights in Australia (Report, August 2021).

‘Helping Nurses Lift Much-Needed Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Care in Rural and Regional Areas’, Monash University (Web Page, 29 July 2024) https://www.monash.edu/news/articles/helping-nurses-lift-much-needed-access-to-sexual-andreproductive-health-care-in-rural-and-regional-areas.

specify that nurse practitioners and midwives must be acting within their scope of practice. This means that there would be a government initiative to train nurses to assist with the termination of pregnancy. This underscores the need to reduce geographic and financial barriers to reproductive healthcare and abortion services.

While progress has been made, the fight for reproductive rights is far from over. Reproductive rights are not just a matter of healthcare; they are a matter of human rights. Women must have the autonomy to make decisions about their bodies, free from political or religious interference. As the ORIENT study and proposed amendments to the law demonstrate, there is hope for a future where reproductive healthcare is accessible to all women, regardless of where they live or their socioeconomic status. However, this future will only be realised if we continue to advocate for these rights and push for reforms that ensure equitable access for every woman in Australia.