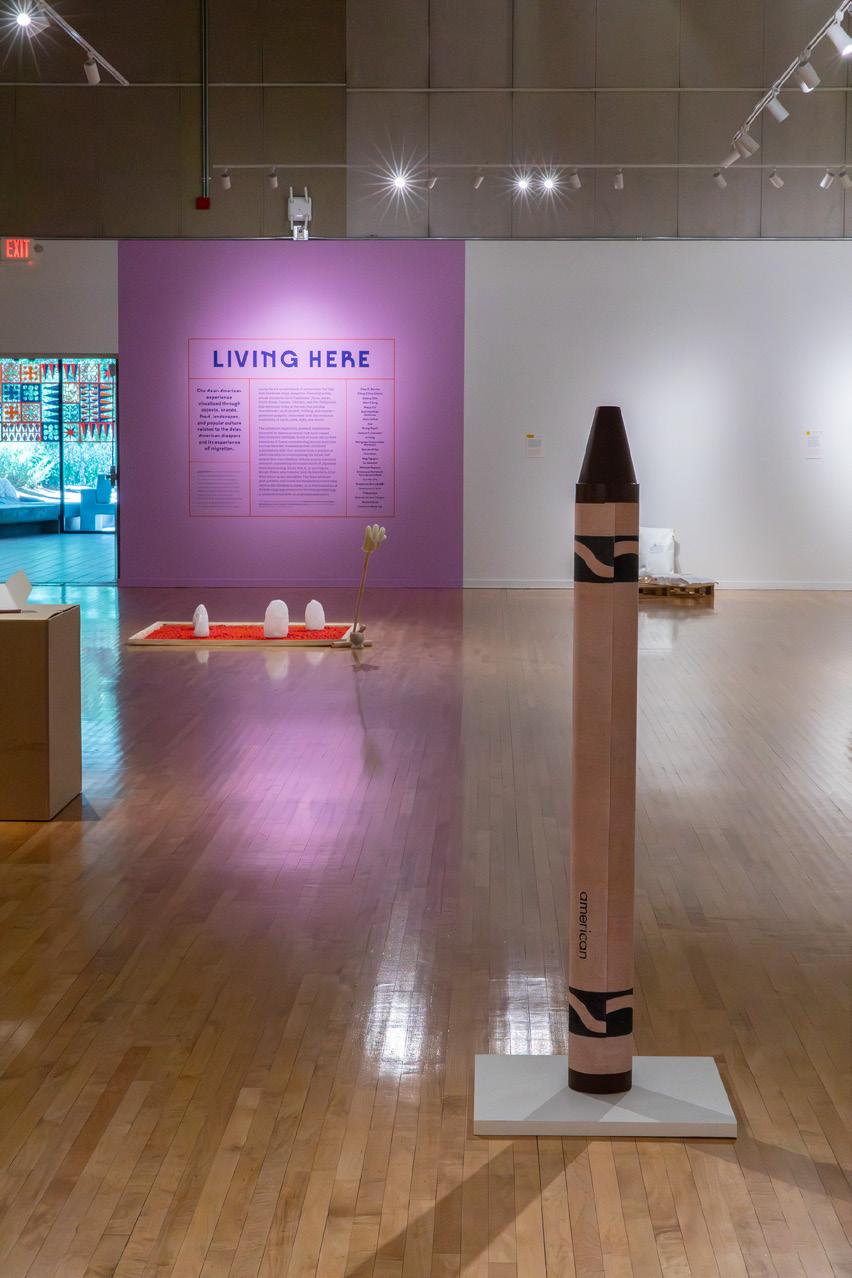

LIVI NG HERE

JULY 20–DECEMBER 20, 2025

MA RJO R IE B A RRICK M USEU M OF A R T U N IVERSI T Y OF N EV A D A , L A S VEG A S

JULY 20–DECEMBER 20, 2025

MA RJO R IE B A RRICK M USEU M OF A R T U N IVERSI T Y OF N EV A D A , L A S VEG A S

Living Here is an exhibition of artists from the East and Southeast Asian diasporas. Featuring artists whose ancestries lie in Cambodia, China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines, this exhibition looks at the way that familiar touchstones—such as food, clothing, and movies— permeate diasporic movement with the sensuous materiality of touch, taste, sight, and sound.

The artists are inspired by personal experiences informed by historical events that have shaped their diasporic identities. Some of them call on their memories of home, remembering favorite activities such as karaoke, reassessing their childhood relationships with their parents from a position of adult maturity, or contemplating the future that awaits their own children. Others employ historical research, considering the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, or the Filipino Rough Riders who traveled with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in the late 1800s. The links between past, present, and future are manifested in everyday objects like balikbayan boxes, or in the frustration of English-language autocorrect technology replacing a person’s name with an anglicized alternative.

The Asian American experience visualized through objects, brands, food, landscapes, and popular culture related to the Asian American diaspora and its experience of migration.

Eliza O. Barrios

Ching Ching Cheng

Daieny Chin

Jisoo Chung

Emmanuel David and Yumi Janairo Roth

Maya Fuji

Sush Machida Gaikotsu

Jeannie Hua

Hue

Phung Huynh

Jeanne F. Jalandoni

eri king

Maryrose

Cobarrubias Mendoza

Quindo Miller

Jiha Moon

May Nguyen

Ian Racoma

Michael Rippens

Jennifer Seo

Stephanie Shih (史欣雲)

Stephanie H. Shih

TT Takemoto

Sherwin Rivera Tibayan

Maria Villote

Christine Wong Yap

Mark Padoongpatt, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Asian American Studies and Interdisciplinary Studies

It’s true that Asian Americans are not a monolith. As part of a larger Asian diaspora, we are incredibly diverse and complex—heterogeneous. We are culturally and linguistically different. We don’t speak the same language, and sometimes use different dialects when we do. We carry and practice multiple cultural traditions, religions, and lifeways. Many of us were born in the United States, but a majority are immigrants. We are among the most educated and the least educated in the country. Some of us have higher median annual personal earnings and household income than the general population, while some of us live in extreme poverty. We dislike and fight each other. Most of us don’t even describe ourselves as “Asian” or “Asian American” but prefer to identify ethnically or with other labels instead.

But it’s also true that we can—and ought to—think and talk about Asian Americans as a group with a shared experience. Collectively, the pieces in this exhibit reveal, to borrow from Sonia Shah, that despite the fact that our lives are different in substance, we have been and continue to be “monumentally shaped” by history and broader forces in American society: U.S. global power, colonialism, imperialism, war, militarization, sexism, and racism. These forces bind us; they affect all of us. We are not here by accident. We did not come from spots randomly around Asia and the Pacific but from places where the U.S. penetrated. We are immigrants and refugees, uprooted and unsettled. We travel back and forth across borders, both physically and in memory, returning “home” and back again. We are deemed foreign, alien, unassimilable, and a “model” American all at once. We navigate, resist, and transform these forces everyday, in the everyday. This is what it means to be living here.

The concept of “kapwa” is defined by Virgilio Enriquez and Leny Strobel, scholars of Indigenous Filipino culture, as a “recognition of a shared identity or, an inner self, shared with others.” “Kapwa is more than just a cultural value; It is a reminder that we are all part of a shared identity,” Mendoza explains. “I am thinking about how wonderful it would be if the value of Kapwa was available to be shared widely. I am playfully ‘boxing’ the concept, as in a form of distribution. It would be so nice if we recognized Kapwa in our lives more.” She connects her work to the visual language of consumer products (the Coca-Cola logo) and reminds us of consumerism’s intersection with art history (Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes).

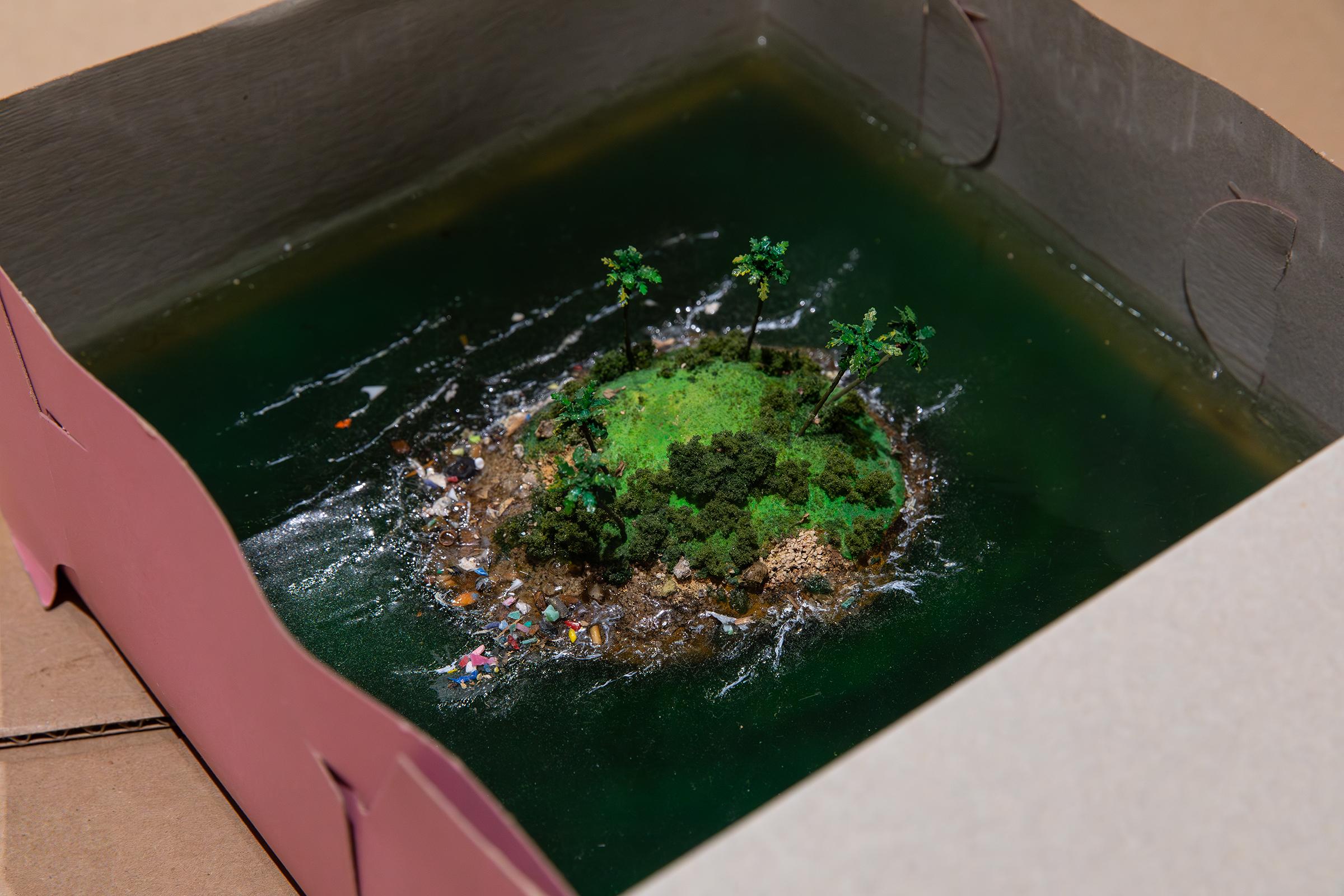

Filipino treats were not widely available in Southern California when the artist was growing up during the 1970s. Instead she ate pastries in pink boxes from local Chinese American bakeries. The impression the pastries left on her—“familiar and slightly different at the same time”—shaped the creation of Isla and Immigrant. “I’m archiving memories associated with objects such as a pink pastry box; it is representative of culture, location, and identification. The palm tree is like a happy surprise...like how the notion of a pink box feels in my memory, triggering positive associations to food and culture. In Isla, the island is polluted with trash, showing the reality of our shared memories of an idyllic island.”

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores personal narratives, material significance, and history. As a 1.75-generation immigrant, her identity was shaped by perspectives and experiences that continue to unfold through her work in drawing, sculpture, and installation. Since 2001, she has served as an Associate Professor and Drawing Coordinator in the Visual Arts and Media Studies Division of Pasadena City College. From 2022–24, she served on the board of FilAm Arts (The Association for the Advancement of Filipino-American Arts and Culture). Mendoza earned her MFA from the Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. Her work has been exhibited in the United States, Canada, and the Philippines.

Kapwa, 2018 – 2020, cardboard and spray paint, 85.5 x 178.25 x 0.25 in.

Isla, 2020, pastry box, scenery materials, acrylic, trash, 5.75 x 14.75 x 18.25 in.

Immigrant, 2018, cardboard box, paper, gouache, 6.25 x 13 x 18 in.

The presence of a shipping pallet clues us in to raft’s themes of international commerce and everything associated with it: colonialism, globalism, migration, consumerism, and cross-cultural exchange. The rice bags are modeled on the Calrose Botan brand that Mendoza–like many of her Filipino-American peers–grew up with as a child in 1970s California. The artist has subtly altered them by changing the name to “Calotus,” with a lotus flower instead of a rose, and replacing “Botan” with “Baton,” to suggest both the passing of a baton and the Province of Bataan in the Philippines. The positions of the bags mirror the placement of key figures in the painting The Raft of the Medusa, by French painter Théodore Géricault (1791-1824). Like Mendoza, Géricault was processing some personal ideas about the effects of international cross-fertilization, as the Medusa in his title was the name of a French ship transporting passengers to the African colony of Senegal.

“Much of the diasporic experience involves grappling with the continued amputation of the context of our origins, histories, and cultural practices when we are perceived as cultural ‘others’ in American society,” said Stephanie Shih (史欣雲) in an interview with Lenscratch. As a professor of linguistics as well as an artist, she notes that still lifes constitute visual languages, with distinct culturally-specific traditions and references.“Still lifes are the one genre historically that comes absolutely loaded with symbolism, with signs in the art that communicate messages to the viewer. There are flies in classic European religious still lifes that symbolize mortality and decay in contrast to godliness. In historical Chinese art, rebuses–‘visual puns’–were incredibly common: for example, the combination of peonies and roosters symbolize a well-wishing for achieving success because the words for peonies and roosters sound similar to the words for prestige, honor, and expectation.”

Her work resists the process of amputation by merging symbols from multiple traditions across Asia and Europe into a united American whole. An Auspicious Start to the Year of the Tiger mingles Chinese references to the “celebration of lucky fruit, daily life, the new year,” with signs of European mortality, such as the fly. Shih outlines the diasporic connotations of the fruits. “The mandarins are kishus, a varietal transplanted to the US from Japan in the 1980s. The pomelolooking citrus are oro blancos, which were bred in Southern California from a cross between pomelos (which have a long history in Southeast and East Asia for new years’ celebrations) and white grapefruit. The non-traditional oro blancos are here as a symbol of the continued development and remixing of Asian diaspora experiences.” Ugly Duckling uses the visual conventions of European still lifes to present a Chinese celebratory meal of roast duck sourced from Californian restaurants. Shih makes a point of crediting them. “Cantonese roast duck from Sam Woo BBQ and peking duck from Moon House.”

As a second generation Taiwanese-Chinese American, Stephanie Shih (史欣雲) explores the contemporary and historical cultural dynamics of the diaspora through her still life creations, drawing on her background in semiotics and research to recode the symbologies of the still life canon. Her work has been exhibited in the United Kingdom and across the United States. Her photography has been featured in outlets including Lenscratch, Gastronomica, Audubon, and Los Angeles Times. She currently lives and works in Los Angeles where she is a professor at the University of Southern California.

STEPHANIE SHIH (史欣 雲)

Ugly Duckling, 2021, archival pigment print on bamboo paper, wood panel, varnish, glue, acrylics, 32 x 48 x 1.5 in.

An Auspicious Start to the Year of the Tiger, 2022, archival pigment print on bamboo paper, wood panel, varnish, glue, acrylics, 40 x 30 x 1.5 in.

STEPHANIE

SHIH (史欣 雲)

The First Slice, 2023, looping video, monitor, digital media player, plaster, acrylics 27 x 18 x 3 in.

Accompanied by Lap Ngo’s “Chocolate Cake” and “Strawberry Cake”, 2024

“Chocolate Cake”: Stand and plates: Bradford pear; Cake: maple, walnut, juniper, cherry

“Strawberry Cake”: Stand and plates: Chinese pistache; Cake: maple, redwood, juniper, cherry

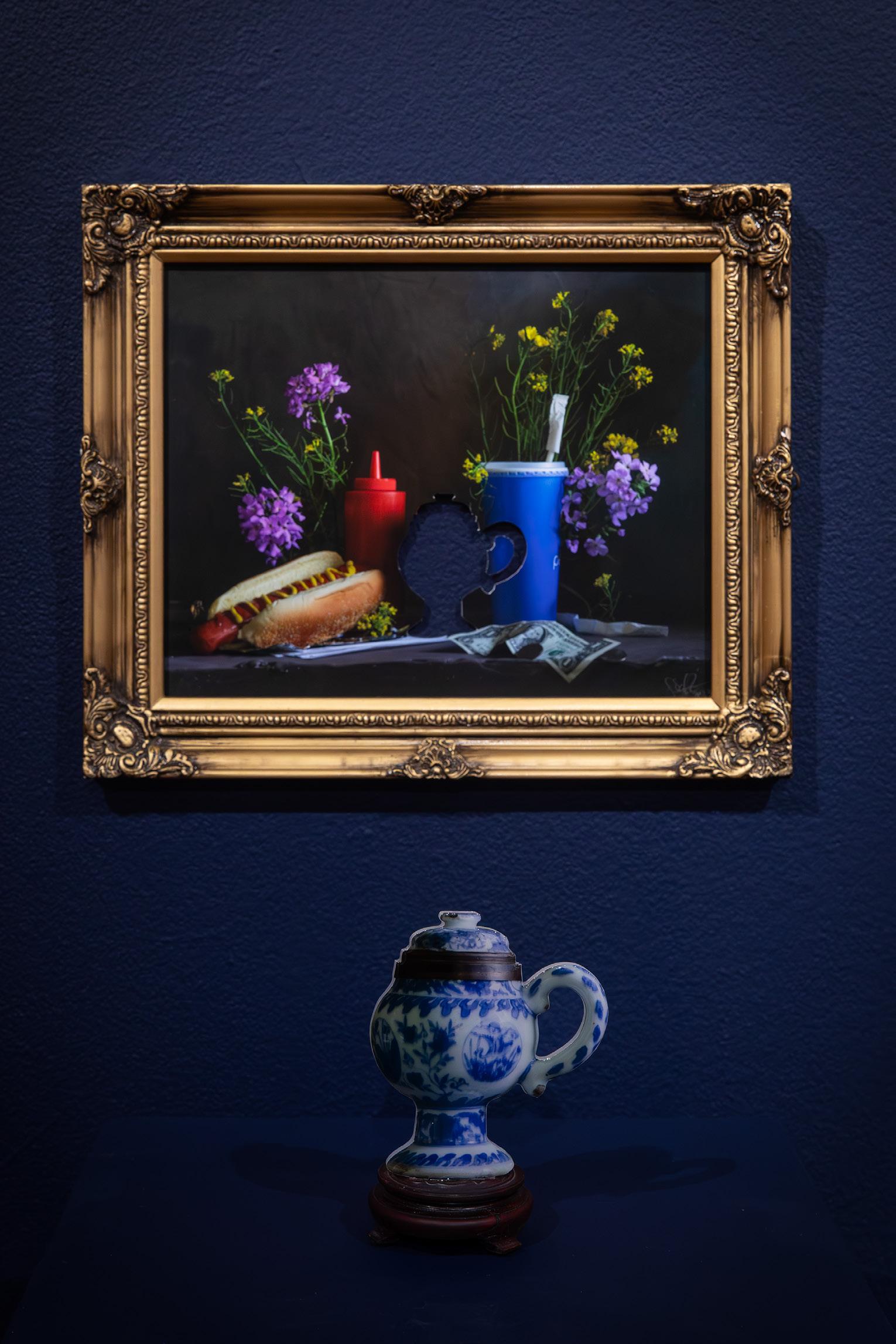

Seventeenth-century flower paintings from The Netherlands often use dark backgrounds and deep shadows to counterpoint the bright colors of their subject matter. Here, Stephanie Shih (史欣雲) uses that visual language to symbolically unite Europe with, in her words, “comfort foods from my own upbringing as a TaiwaneseChinese American—foods that are derided as ‘strange’ in the United States but hold quotidian significance in Chinese culture.”

Referring to The First Slice, she writes, “My oldest childhood friend and I grew up with Oakland Chinatown birthday cakes like this one from Napoleon Super Bakery (拿破崙餅) gracing our tables every celebration. When we got older, we continued to order from the same bakeries ourselves using our out-of-practice Chinese language skills (which resulted in ordering accidents like all-pink cakes that became part of our traditions).” In Onggi with Six Kimchi, she directs our attention to Korean American foodways by including juicy curls of kimchi that gently hint at the variegated red and white streaks of the Rembrandt tulips that were highly prized by the Dutch. She stands the bouquet in a vase modeled on an onggi–a Korean clay pot traditionally used for kimchi fermentation. As part of her practice, Shih credits the local businesses and artisans who provided her with materials. She notes that the kimchi was created by Oliver Ko of Korilla Kimchi and the ceramics by ceramicist Eunbi Cho, while the cake slice in First Slice was carved by the sculptor Lap Ngo.

Shih collaborated with the Museums at Washington and Lee University in southwest Virginia to mine their Collection of Chinese Export Porcelain and create the series of works that includes Dad’s Favorite, Mondays and Gilding the Lily/ Corn Soup. Choosing from a range of almost 3,000 Chinesemade ceramics, she used historical research to connect them to Europe and Asia before drawing on her own presence in contemporary America to bind everything together.

For Dad’s Favorite, Mondays, she chose a 17th-century mustard pot. Considering the diasporic histories of both mustard and its culinary partner ketchup, she observed that the yellow-flowered mustard plant (visible in the photograph) is native to Eurasia, a region of cultural exchange and trade between Europe and Asia. Ketchup has its origins in Chinese fish sauce from Southeast Asia. After centuries, the ancient fermented substance was transformed by an ingredient from South America—the tomato. “Nowadays, both condiments are quintessentially American toppings for hot dogs,” she writes, “which I grew up eating at Costco food courts when my dad would, like many frugally-minded immigrant parents, make his weekly shopping pilgrimages there every Monday.”

Writing about Gilding the Lily/Corn Soup, she notes that the ceramic vessel started its journey as an incense burner in China before being exported to the Netherlands. Then it went to Austria, where the Du Paquier porcelain factory designed a lid that transformed it into a soup tureen somewhere around 1735. The original blue and white decorations were joined by European additions in red and gold. The corn soup in the second photograph underscores the vessel’s current presence in the Americas. (Corn was originally cultivated in Mexico.) Recipes for corn soup and other dishes were promoted in new Asian markets after World War II to boost sales of American canned goods. The soup in this photograph was made from a recipe by Shih’s mother, an emigrant from one of those areas: Taiwan.

eri king

Red 40 Zen MSG Rock Garden belongs to a body of artworks titled Healthy People Are Bad for Capitalism. It makes use of “like cures like,” a homeopathic doctrine which proposes that a substance that causes harmful symptoms can also bring about healing. In this case the substance is an all-American snack food, Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, while the medium through which the Cheetos harm and heal is a karesansui (枯山水), commonly known in English as a Japanese zen garden. Karesansui are traditionally made of gravel, but eri king created this one by pulverising the Cheetos with a mortar and pestle before raking the crumbs into concentric ring patterns, or mizumon (水紋). The gravel space becomes a stimulating shade of fiery red thanks to Red 40, the synthetic petroleum-based dye that gives the snack its color. The large rocks are created from another ingredient that makes Cheetos appealing and commercially successful—the taste-enhancing salt known as Monosodium glutamate, or MSG. (Another Japanese invention, this time dating from 1908.) “The four MSG Healing Rocks are placed inside the garden to cleanse and purify the air from the chemical Red 40,” king explains. In theory, the salt will absorb the moist air around the Cheeto crumbs, trap the toxins inside, and exhale the detoxified dampness. The snack food counteracts its own noxious aura thanks to the karesansui, creating a space where harm and healing enter into neutral balance.

eri king is a New York-based multidisciplinary artist working across painting, drawing, installation, sculpture, textiles, video, sound, and performance. She employs a syncretic, collage-like approach that weaves together diverse philosophies, ideologies, rituals, cultural phenomena, and objects. She received her BFA from UNLV and her MFA from Hunter College, New York. From 2011 to 2014, she was the co-founder and curator of the artist-run spaces 5th Wall Gallery and Project Space in Las Vegas. Her work has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions in New York, Nevada, and the UK. She currently lives in Brooklyn, New York, where she is one half of the collaborative art duo Eridan alongside artist Daniel Greer.

Red 40 Zen MSG Rock Garden, 2018, hand-pulverized Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, Monosodium Glutamate, marble, mortar and pestle, Zen rake, wood, and plastic, 32.5 x 75 x 65.5 in.

These ceramics are part of Jiha Moon’s Yellowave series. She uses the color yellow to convey a “social, political, or cultural point of view,” acknowledging its historical association with racial slurs directed at Asian Americans. By prominently and abundantly incorporating yellow in her work, she subverts these biases and reclaims it as a symbol of joy.

Peaches, dumplings, and banana peels are some of her recurring motifs. She values the way they hover between a multitude of contexts, making them simultaneously familiar and hard to pin down. In a 2022 interview with Guernica magazine, she said she cherishes art that leads to ambiguity, even misreadings. “For me, this misunderstanding is often the first step of understanding.” As a Korean who moved to the United States in her twenties, she knows that different audiences will see peaches as symbols of good luck (Korea), the state of Georgia (the U.S.), or maybe as comical sets of breasts and buttocks. Dumplings are a pan-cultural unifier, but viewers from different backgrounds will read them as “mandu,” (Korean) “gyoza,” (Japanese) or “pierogi” (Polish), all with different associations.

Jiha Moon’s paintings, ceramic sculptures, and installations explore fluid identities and the global movement of people and culture. She draws from a wide range of influences, including international art histories, Korean temple paintings and folk traditions, popular culture, internet emojis and icons, and product packaging from around the world. She is a 2023 Guggenheim Fellow and a recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Painters & Sculptors Grant.

Her mid-career survey exhibition, Double Welcome: Most Everyone’s Mad Here, organized by the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art and the Taubman Museum, toured more than 15 museums across the U.S. She earned her MFA from the University of Iowa. Born in DaeGu, South Korea, she is currently based in Florida where she is a faculty member at Florida State University.

JIHA MOON LEFT Yellowave Peach Smile, 2022, stoneware, underglaze, glaze, 12.5 x 12 x 3.5 in.

RIGHT Yellowave (Round and Round), 2023, stoneware, underglaze, glaze, 4.5 x 13.25 x 10.75 in.

BOTTOM Yellowave (Double Firework), 2023, stoneware, underglaze, glaze, 3.25 x 19.5 x 10.75 in.

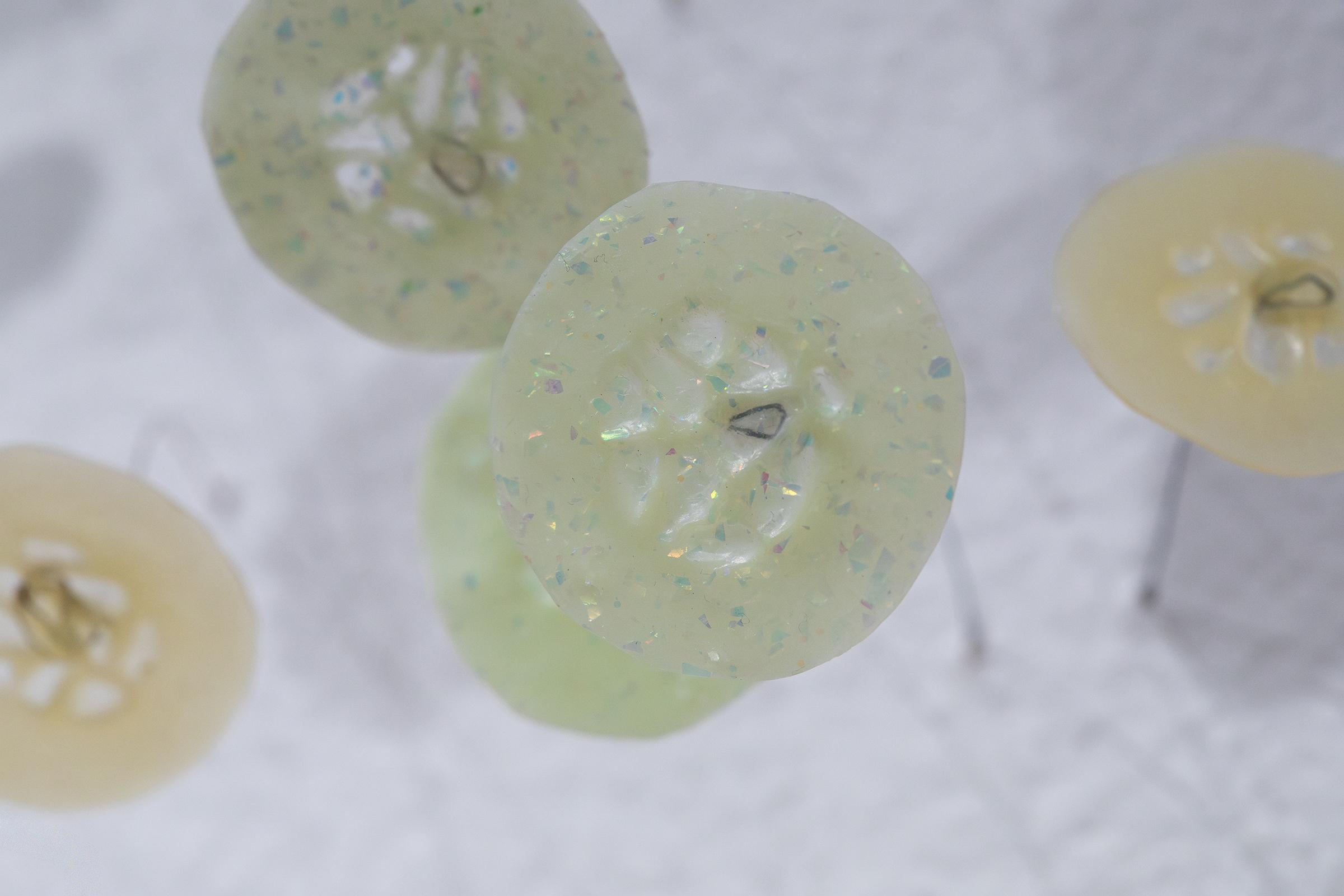

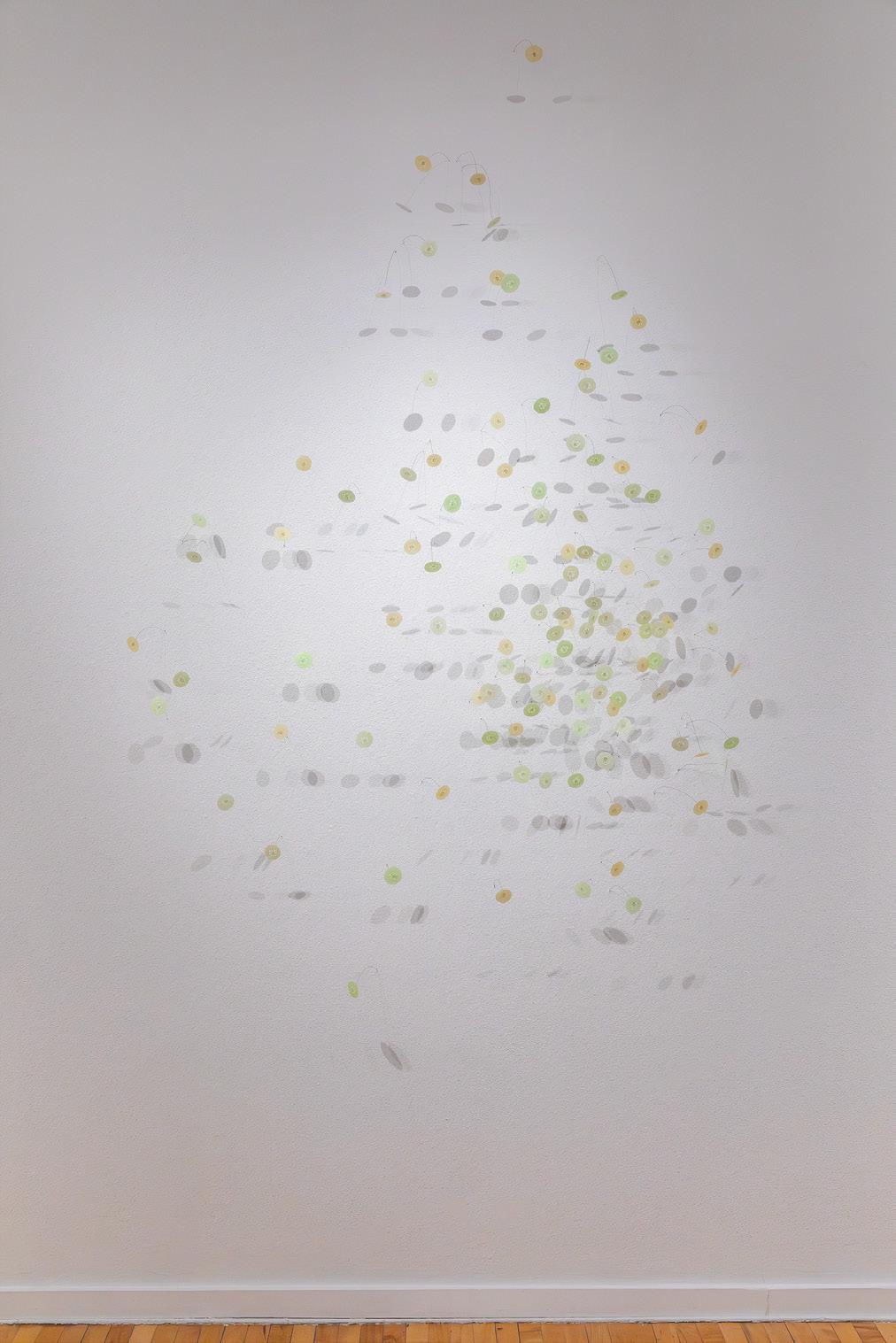

The impact of this artwork depends on the relationship between its title and the sculpted slices of fake cucumber. When Jennifer Seo says the Korean word for cucumber (오이) out loud, she notices that it sounds like the English letters O.E.G. With O.E.G. (cucumbers), she creates a new word that is neither English nor Korean, but the noise of meaning migrating between the two languages—a phenomenon that materializes out of a diasporic sensitivity to difference. Her cucumber slices stand out from the wall on thin wires, making them seem more vulnerable than they would if they were positioned securely on a shelf or a pedestal. Seo’s practice as a whole focuses on fragility and disappearance. Her most recent artworks (not featured in Living Here) are delicate paper models of objects she finds in old family photographs. “Recreating these objects is a study of my family that I have always felt disconnected from, but cherish,” she writes. O.E.G. (cucumbers) is filled with similar feelings of connection and slippage.

Jennifer Seo creates drawings and sculptures that express a desire for connection and an awareness of preservation and loss. She studied at artist So Moon Kim's hagwon from 2004 to 2005 and earned her MFA from the University of Texas at San Antonio in 2020. Seo is currently based in Washington, where she works as an Assistant Professor at Gonzaga University in Spokane. Her art has been exhibited across the United States and at the Czong Institute for Contemporary Art (CICA) in South Korea.

JENNIFER

O.E.G (cucumbers), 2023, polymer clay, wire, 114 x 54 x 6.75 in.

“The longer I spend time in the U.S. I’ve noticed the way certain habits have shifted and morphed, often re-emerging as new ways of being. I often surprise myself by the unexpected ways certain parts of each culture have taken root within me,” Maya Fuji said during an interview with Artsin Square. In her paintings she visualizes the story of that shifting, morphing experience.

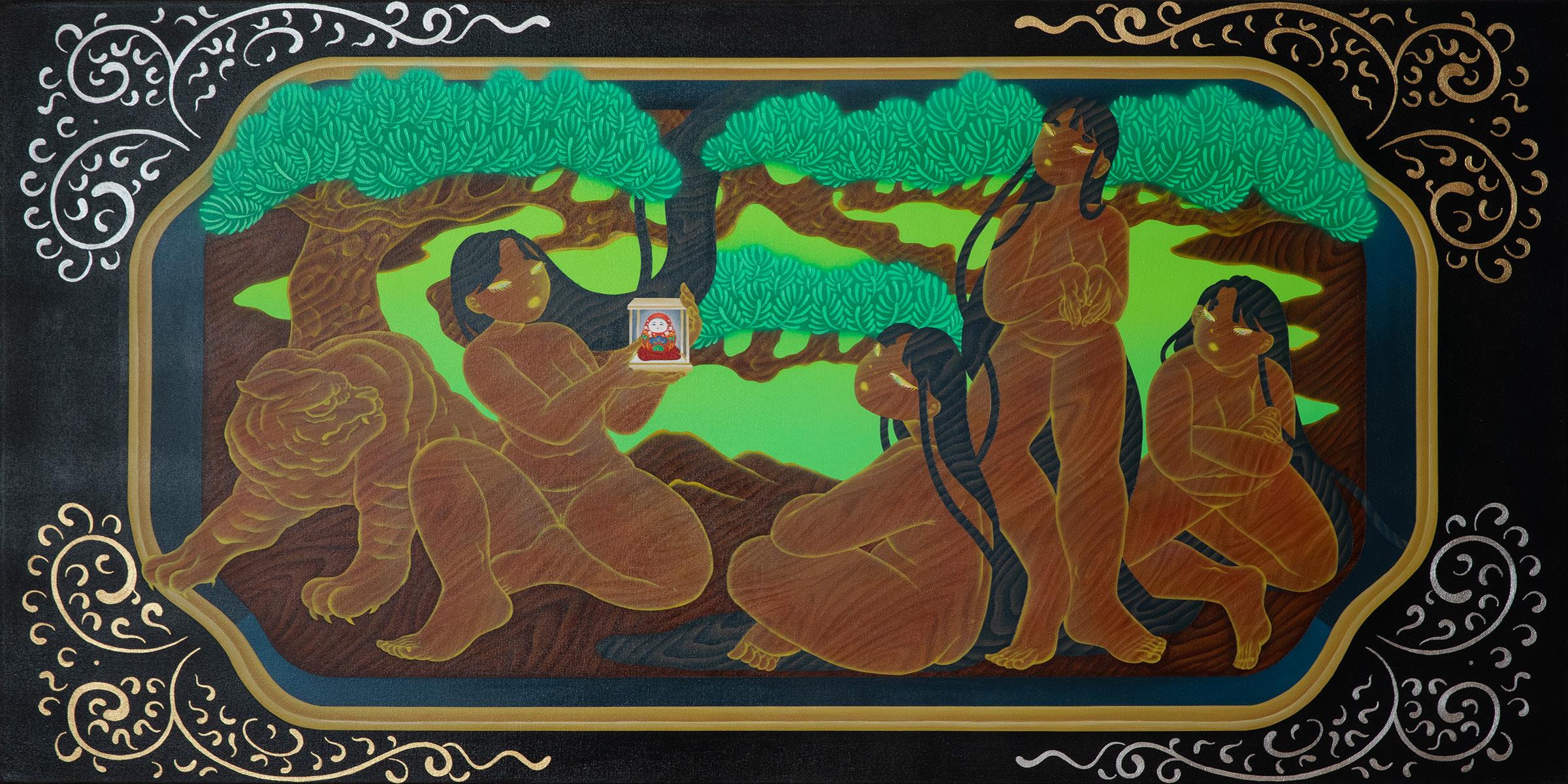

Growing up biracial, she attended school in both California’s Bay Area and Kanazawa in western Japan. In A Word That Doesn’t Exist・存在し ない言葉, she remembers the classroom experience of unsuccessfully trying to find a word that meant “diversity” in Japanese on a mechanical translator. In other paintings she reimagines Japanese spirit beings as contemporary women who wear up-to-date nail art on elegant fingers inspired by ukiyo-e imagery from the Edo period. Cultural migration takes on a physical shape. Can the spirits migrate, just like people? Or do they only stay in Japanese homes? The question is heightened by the knowledge that these spirits are traditionally formed by the accumulated energy of families living in a single place for years. Double Belonging is inspired by fragments of the wooden Buddhist altar that she brought from her late grandmother’s house in Kanazawa to her home in the United States. By replacing the original picture of Buddhist monks with a group of her women holding up a Kaga Hachiman Okiagari—a figure from Japan’s other official religion, Shintoism— Fuji shows us that a whole, complete form can be made up of things that espouse doubleness, and that have “shifted and morphed.”

Maya Fuji was born in Kanazawa, Japan. She is a self-taught artist who shifted careers midway through her MBA program to pursue her passion for visual arts and painting. She immigrated to Berkeley, California at an early age, and spent time moving back and forth between Kanazawa and the United States. She currently lives and works out of San Francisco. Fuji has had solo exhibitions in both Japan and America. She received the Innovate Grant, was nominated for the SFMoMA SECA Award, and was a finalist for the Foundwork Artist Prize in 2023. In 2024 she received a San Francisco Arts Commission Artist Grant and was an artist-in-residence at Wassaic Projects.

TOP

A Word That Doesn’t Exist

葉, 2023, acrylic, oil pastel, charcoal, and rhinestone on canvas, 16 x 20 x 1.5 in.

BOTTOM Double Belonging, 2024, acrylic, silver and gold leaf on canvas, 24 x 48 x 1.5 in.

MAYA FUJI

LEFT–RIGHT

A Word That Doesn’t Exist ・ 存在しない言葉, 2023, acrylic, oil pastel, charcoal, and rhinestone on canvas, 16 x 20 x 1.5 in.

Pareidolia, 2024, acrylic and rhinestone on canvas, 24 x 24 x 1.5 in.

Buddy, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 12 x 12 x 1.5 in.

Scent of a Mosquito Coil ・ 常夏の香り, 2024, acrylic and rhinestone on canvas, 12 x 12 x 1.5 in.

Double Belonging, 2024, acrylic, silver and gold leaf on canvas, 24 x 48 x 1.5 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery

High Horse resembles a kudkuran ng niyog, a device used for manually grating the meat out of niyog, or mature coconuts. Coconuts play a major role in life throughout the Philippines, where different parts of the tree have historically been used for food, medicine, shelter, and fuel, among other things. Coconut oil is one of the nation’s primary exports. Maria Villote uses this culturally charged form to unite a number of suggestions that, together, become a commentary on the difficulty of decolonizing the mind. She replaces the spiked disc with a Western cowboy spur, while the coconut flakes become a heap of skin-whitening soap. (Advertised in the Philippines and within the Filipino diaspora, these soaps promise to deliver “natural fairness for your face and body” with ingredients that often include acidic chemicals.) Speaking about the work, she points out that “coconut” can be used as a derogatory term for people of color who are accused of betraying their cultural identity and becoming “white on the inside.” Understanding and undoing that process is likened to a physical grind.

Maria Fe Victoria Tolentino Villote is an interdisciplinary artist whose process-based works explore the complexities of identity and the transformation of emotional experience through mimesis. As a 1.5-generation immigrant from the Philippines, she draws on fleeting and fragmented childhood memories to reflect on the intricate process of cultural amalgamation within the diaspora and the fluidity of cultural boundaries. Her work examines the enduring impacts of colonial mentality, internalized racism, and cultural assimilation. Villote received her BA from the University of California, Berkeley. Her work has been exhibited in the United States and Mexico. She lives and works in Ventura County, California.

High Horse, 2018, wood, coconut shells, whitening beauty soap, western-style horizontal cowboy spur, leather, 14.75 x 37.75 x 60.75 in.

Mark Padoongpatt, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Asian American Studies and Interdisciplinary Studies

The Asian American diasporic experience is inextricably intertwined with imagining and constructing “home” in new places. Sometimes, this gets expressed rather strongly and spectacularly—in “Asian” neighborhoods, temples, festivals, shopping malls and store signs. Yet, this exhibition is a beautifully vivid, important reminder that some of the most profound expressions of making and connecting with home emerge from, and are encoded within, the humdrum rhythms and practices of everyday life. We see and feel it in ordinary, commonplace, and thus seemingly insignificant objects and activities: bags of rice, tsinelas, a pink donut box, singing karaoke, scraping meat out of coconuts, and stuffing cardboard boxes with goods. Each reflects larger struggles over power and operates as contested sites of social and cultural transformation. They are local resonances of larger global processes and issues. They represent stability under turbulent conditions of migration. They serve as clues as to how Asian Americans have shaped and defined the places they live, leaving imprints even when they are not formally or intentionally trying to do so, as well as how places, in turn, reshape and redefine Asian American identities, communities, and meanings of home. And they illustrate how memories of home are fraught; home is not always safe. These expressions from the Asian American diaspora present glimpses, or little eruptions, of new ways of being in the world and of relating to each other—new ways of living.

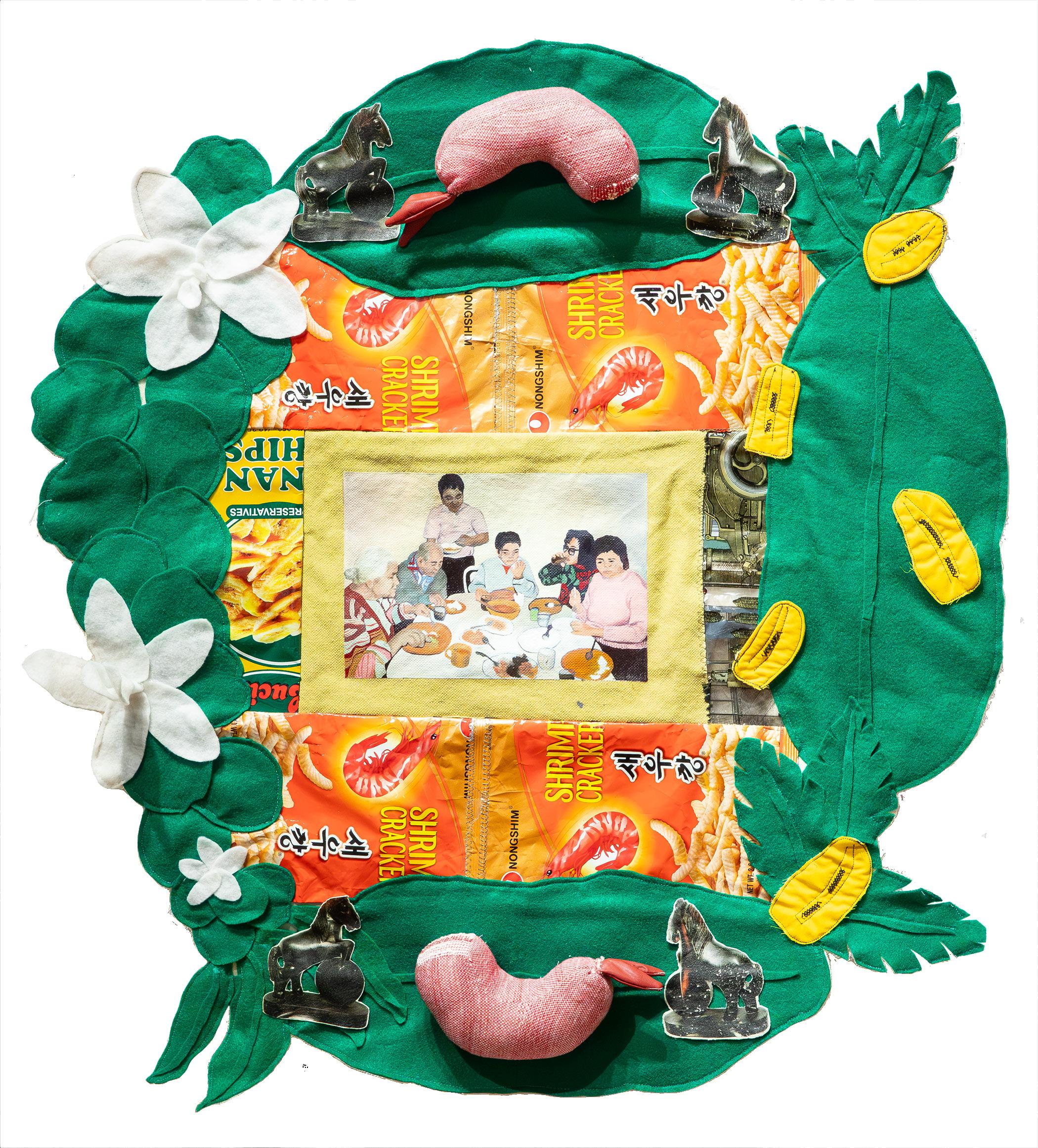

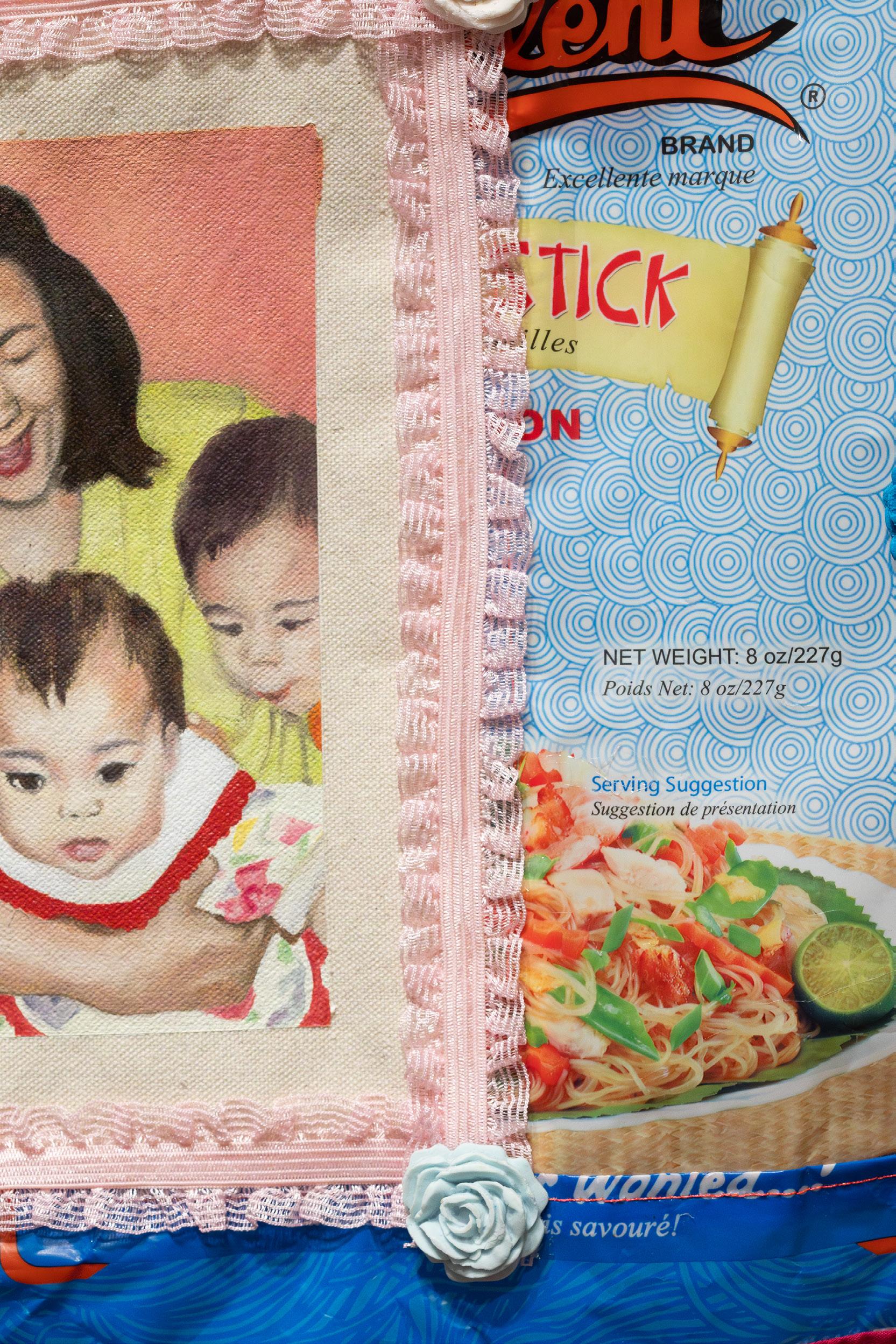

In these artworks, Jalandoni highlights the cultural and personal histories that enrich the Filipino diaspora.

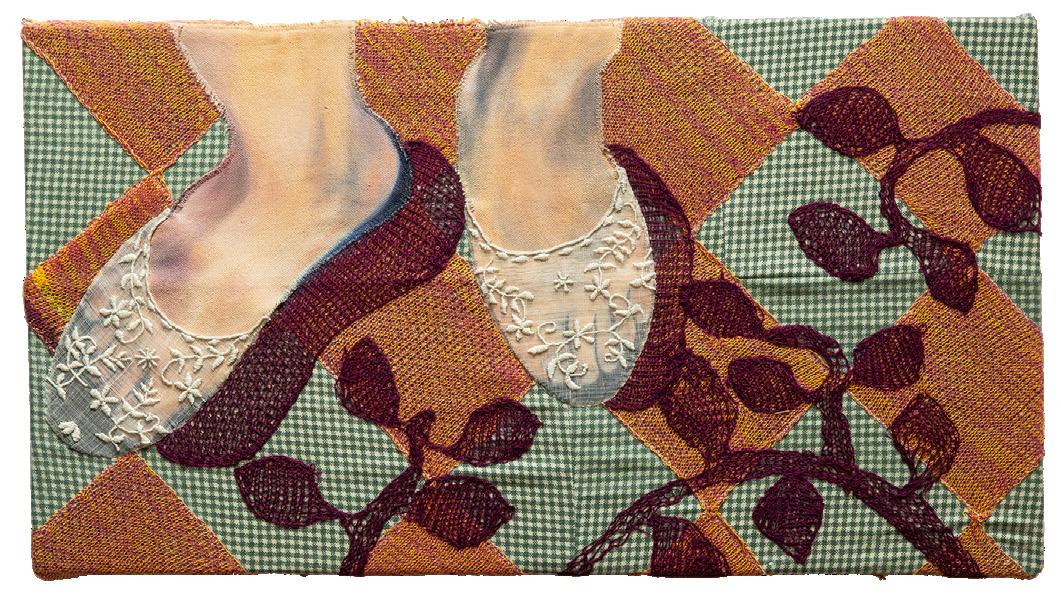

And Look! Piña Slippers (Tsinelas) reimagines Cinderella’s glass slippers as tsinelas made from piña, or pineapple-leaf fiber. Introduced to the Philippines by Spanish colonizers, pineapple plants provided an alternative to an older traditional cloth made from the abacá plant. Piña textiles were exported to Europe where they became garments for the rich. In the Philippines, they were used to make formal clothing such as the barong tagalog. These slippers are a reminder of the country’s presence in the global economy and piña’s historical association with beauty and status.

The other two works react to the Boxer Codex. Produced anonymously in Manila during the late 1700s, the Codex describes the people and customs of several different Asian countries. It includes fifteen pictures of people from the Philippines in traditional costumes. Jalandoni responds by foregrounding her existence as an individual person, not a costumed stereotype.

Dinner with Lola and Lolo in Seattle reproduces a photograph—taken by her father, Anthony Jalandoni—of her New York-based family visiting interstate relatives. The Asian flora and fauna of the Codex are translated into objects familiar to the artist such as shrimp chip bags and a wooden horse from her childhood. She notes that her father’s photograph was once used in an American nonfiction book titled Filipinos that, like the Codex, was created to explain Filipinos to a non-Filipino audience.

In Happy Birthday she is celebrating her first birthday. The rice noodle packet alludes to the pancit traditionally eaten on Filipino birthdays to symbolise a wish for a long healthy life. The patterned cloth around the edges of the picture resembles the clothing she wore as a child. Through these references to the tactile realities of her own life (clothing, food, aging, family) the artist reveals her Filipina American reality with personal nuances that were unavailable to the authors of both the Codex and Filipinos.

Jeanne F. Jalandoni is a painter and textile artist based in New York City. Her work blends weaving, machine-knitting, and oil painting to explore the complexities of her Filipino American cultural identity. She aims to offer alternate insights into the nuances of Asian American identity, especially as someone who has never been to the Philippines. Jalandoni received a BFA in Studio Art with a concentration in painting from New York University. She has exhibited nationally, as well as in Europe and Asia. Her work is held in private and public collections worldwide.

JEANNE F. JALANDONI

Dinner with Lola and Lolo in Seattle, 2019, oil on canvas stitched to food wrappers, felt, knit fabric, leather, cotton, stuffing, printed fabric, 33 x 30 x 2 in.

And Look! Piña Slippers (Tsinelas), 2023, oil on canvas, cotton, cotton perle embroidery on piña, machine knits, 12 x 22 in.

“Most of my maternal family resides in Seattle, and my family would fly from New York City to spend our summers with them,” Jalandoni recalls. Family Reunion (Ring Around the Rosie) is an intimate memory of a childhood that has passed. The passage of time is quietly underscored by the inclusion of stripes from her mother’s 1970s-era scrapbooks in the background. As with many of her other works, Jalandoni personalizes the scene with photographic images of her family. It includes not only her cousins, her sisters, and herself, but also—in the framed portrait on the wall—the older generations. “There is a reminder of my family roots with the framed portrait of my mother, her siblings, and my lolo and lola (grandparents), who were farmers. My mother’s generation were the first to receive college degrees and then come to America.”

JEANNE F. JALANDONI

Happy Birthday, 2019, oil on canvas, rice noodle plastic sewn to jean, fabric, cotton, trimming, fringe, fondant, 21 x 21.75 in.

OPPOSITE Family Reunion (Ring Around the Rosie), 2023, oil on canvas, cotton T-shirts, iron-on print, cotton and wool weaving, various fabric, machine knits, charcoal, 40.25 x 43.5 in.

Jalandoni raises her family history to mythological proportions with beings of her own invention: humans with carabao heads. Strong and hard-working, these water buffalo are the national animal of the Philippines. The artist associates them with her maternal grandfather, who built a farm with two carabaos to help him.

In With All You Possess, she positions them in an ambiguous network of desire and escapism that reverberates between America and the Philippines. Their yokes break as they plough the farm and they burst free in front of the kind of romanticized tropical sunset that appears on Philippine postcards aimed at American tourists. Their clothing is distinctively Filipino—terno shirts with high-shouldered butterfly sleeves—but a dreamlike photograph of Jalandoni, an American-born child in the United States, is reproduced on one of their skirts. She seems to be standing next to the Statue of Liberty, a symbol of hope and freedom, but this is an illusion. The photograph was taken next to a replica Lady Liberty in Washington state. Through references to the past and future of her family, the artist reflects a history of unsettled fantasies between the two nations.

As a child, Ian Racoma moved between the United States and his grandparents’ home in the Philippines. Coming to adulthood in Las Vegas enabled him to maintain strong ties to Filipino culture “since there is such a large demographic of Filipinos here,” he explains. “This allowed for our families and friends to maintain certain traditions and religious holidays with big groups. A lot of the challenge growing up was navigating these two worlds and learning where and when to use a certain cultural language. These paintings touch a little on that navigation.”

Commenting on Bowl, he remembers that “90% of Asian kids had” bowl haircuts while he was a child, “including girls.” Girls were, however, excluded from his friend group of other boys from Asian and South Pacific backgrounds. It’s Different for Boys sprang from the unease he felt at not being able to locate the source of the misogyny that sometimes emerged in their games. Meanwhile, The Baboy—“baboy” means “pig” in various Filipino dialects—reflects a different kind of anxiety. The fact that lechon is a traditional part of Filipino culture does not alleviate the disquiet he feels when he sees the whole animal fully roasted and laid out as the centerpiece of a meal.

Ian Racoma is a Las Vegas-based artist and graphic designer who articulates his upbringing as a first-generation Filipino American through a practice rooted in painting and drawing. He focuses on the personalities of his subjects in order to draw attention to the multifaceted cultural context that shapes them. His paintings have been exhibited in Las Vegas galleries such as the Winchester-Dondero Cultural Center and Priscilla Fowler Fine Art. Racoma received his BFA from UNLV in 2010. For many years he was a Senior Designer for the Greenspun Media Group, most recently working on the Las Vegas Weekly.

LEFT–RIGHT Bowl, 2025, oil on canvas, 31.56 x 31.56 x 1.5 in.

The Baboy, 2025, oil on canvas, 49.625 x 38.5 x 1.5 in.

It’s Different For Boys, 2025, oil on canvas, 31.56 x 31.56 x 1.5 in.

“Tsinelas is a Tagalog word from the Spanish chinela and translates to slipper,” writes Sherwin Rivera Tibayan. “A common sight in many Filipino and Asian households, I am interested in recording the myriad visual and material qualities of these slippers and considering what these varieties might suggest about their owners and the lives they live. I also want to preserve how they gather and accumulate at the thresholds of doors, hallways, and areas of transition within domestic spaces. For me, they have come to reflect the sometimes messy but always meaningful ways we show and share our individual selves and group identities in the worlds we make at home, and serve as indirect family and group portraits of Filipino Americans, both in the US and in the Philippines.”

Sherwin Rivera Tibayan is a Filipino American photographer living in Austin, Texas. He uses formal strategies of repetition, multiplicity, obstruction, and visual ambiguity to re-present the various technological structures, tools, and supports that make up and sustain our personal and official photo-documentary histories. His projects have gained recognition from Photolucida, the Magenta Foundation, and the Houston Center for Photography. He received his MFA from the University of Oklahoma. His artwork has been exhibited in Europe, Asia, and across the United States.

Untitled (Cedar Park, TX), 2022

Untitled (Indang, Cavite, Philippines), 2024

Untitled (Austin, TX), 2023

Untitled (Indang, Cavite, Philippines), 2024

Untitled (Las Vegas, NV), 2009

Archival pigment prints from the Tsinelas Series, printed in 2025, 17 x 22 in.

“Inspired by my childhood in Vietnam, each box contains an everyday object—simple, often overlooked—now transformed into a keepsake of once-vivid moments that are slowly fading,” writes May Nguyen. The objects she has chosen vividly evoke different senses—the sight of a colored petal, the flavors of home, the touch of a caregiver. “As life continues in a foreign land, these memories blur around the edges, like photographs left too long in the sun, leaving behind only fragments of a home that now exists more in feeling than in form.”

She explains the three types of object like this—

“This small, red plastic stool is more than just a seat—it's a symbol of everyday life in Vietnam. The more beat-up the stool, the better the food that's served beside it. You'd find these stools clustered around street food stalls, holding bowls of steaming phở or fragrant bún thịt nướng, or tucked in a shady corner where two aunties trade gossip over a cup of ca phe sua da. Worn and scratched from years of use, it holds the comfort of familiarity.”

“This paper hand fan holds the quiet memories of childhood nights in Vietnam. During power outages on hot, sticky evenings, my grandma would sit beside me and my sister, slowly fanning us until we fell asleep. In her hands, the fan became a lullaby, a breeze that soothed both our body and soul. Each fold carries the memory of my grandma’s care, comfort, and her love that still lingers with us, soft as wind.”

“In Vietnam, we call bougainvillaea hoa giấy—’paper flower’—for its delicate but vivid petals. At my childhood home, it draped over the front gate, a canopy of color watching over endless summer days. It's embossed in my memory as a quiet witness to many family meals and childhood daydreams. In Las Vegas, bougainvillaea is rare, but when I see one, those fading memories rush back, bright for a moment like those petals in the sun.”

May Nguyen is a graphic designer whose work is influenced by the traditional values of Vietnamese culture and history, as well as the concept of “complex simplicity.” After graduating from dpiCENTER in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, she earned a Bachelor of Science in Graphic Design and Media from UNLV. Nguyen is currently based in Las Vegas where she works for Resorts World Las Vegas.

Giấc Mơ Trưa / The Afternoon Dream, 2025, mixed media installation, 10 x 10 x 5.5 in.

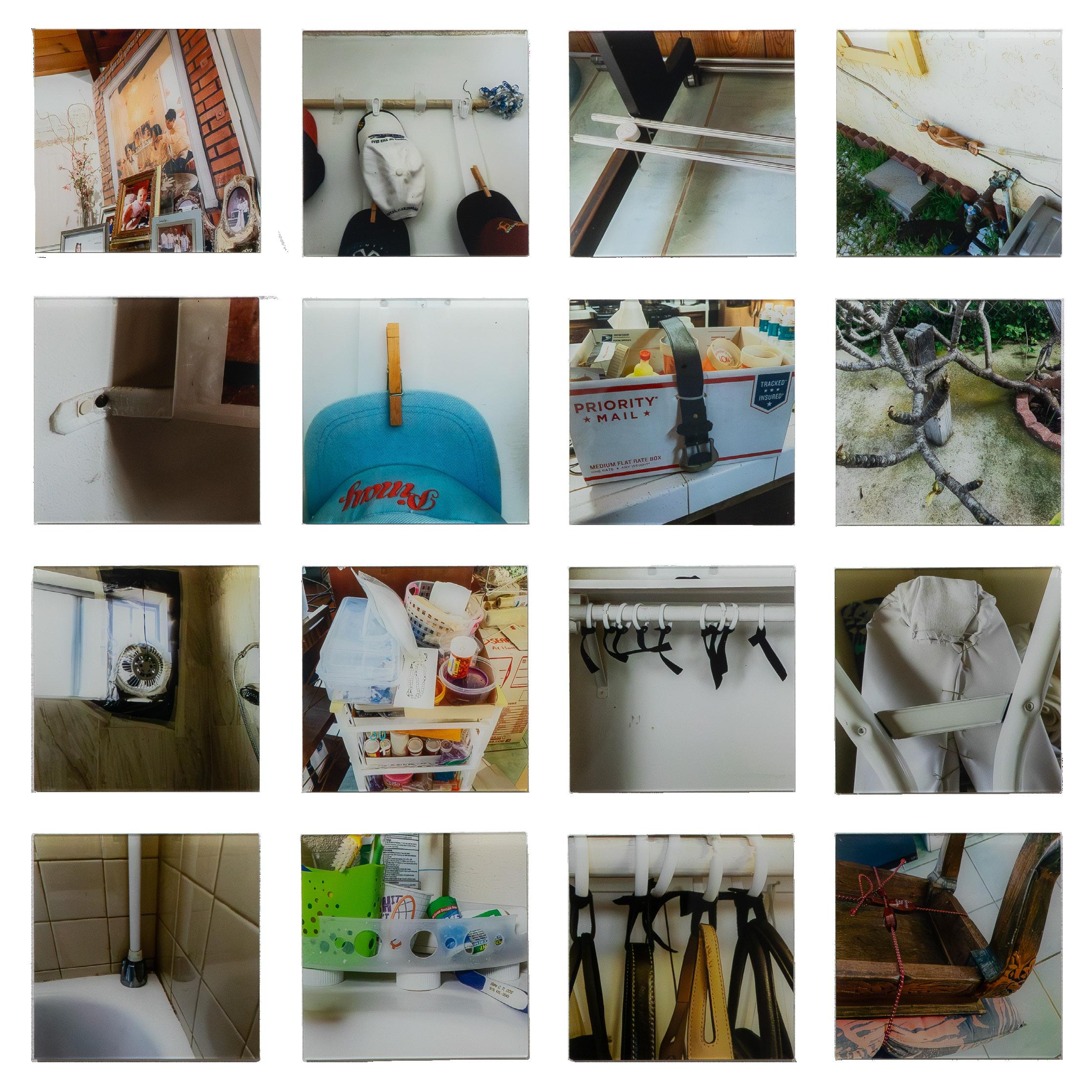

“My childhood home symbolized the legacy of my family’s success having immigrated from the Philippines in 1963,” writes Eliza O. Barrios. In Make Do: part one, she photographs the domestic space as it looked after her mother passed away. The altered objects that embarrassed her as a child are now documented by her adult self. Her mother “repurposed broken fixtures to prop up photos, or support shelving that did not quite fit in a corner,” the artist recalls. “Her fervent need to be creative was evident throughout the house. She had an uncanny ability to see beyond the intended use of an object and resurrect it elsewhere, extending its life. From a make-shift ‘basket’ to a foot-rest using medicine bottle caps and curtain rods, she created contraptions to satisfy her exact needs. The objects range from decorative to functional, all metaphors of how she took control of and managed her experience transitioning to the States.”

This method of taking control by deliberately changing things is reflected in Barrios’ own art practice, where societal norms are often refashioned to suggest perspectives that come closer to the world the artist wants to see. As part of the Filipina American collective M.O.B., for example, the term “mail order brides” is reworked, which creates satire and disruption—a “mob”—while M.O.B.’s Manananggoogle performance project reshapes a traditional Filipino vampire-like quality, the manananggal, into an expression of feminist anti-capitalist satire when manananggal join the executive class.

Eliza O. Barrios is a San Francisco-based artist whose work encompasses both individual and collaborative practices. In her solo work, Barrios explores the relationship between physical space, memory and the impermanence of lived experience, using digital media to orchestrate site-specific installations and projections. Her collaborative practice includes performance, video and photography engaging with concepts of gender and culture (as part of the collective M.O.B./Mail Order Brides), and public interventions addressing current social and political issues (in collaboration with the muralist Paz de la Calzada). Barrios holds a BA from San Francisco State University and a MFA from Mills College. Her solo and collaborative work has shown domestically and internationally in museums, galleries, public spaces and theaters.

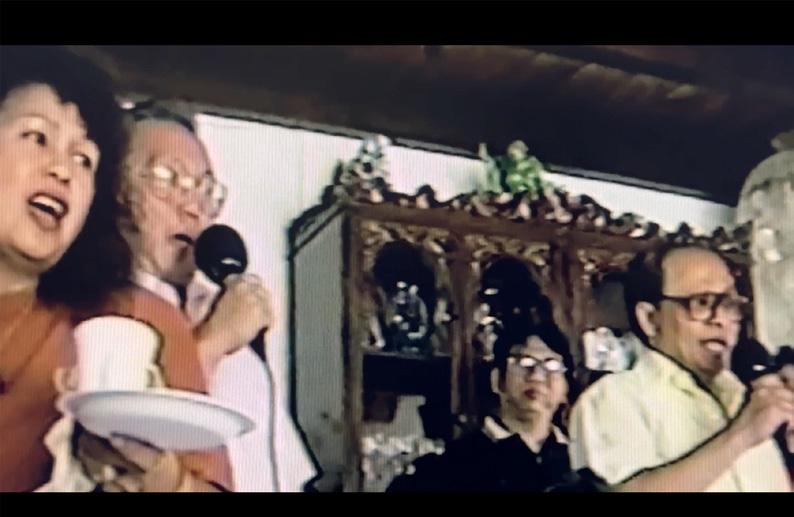

Make Do: part two Karaoke Sessions, help me make it through (2 min, 59 sec), where do I begin (3 min, 20 sec), yesterday (2 min, 33 sec), 2022–present, video, video stills

Voices are central to Eliza O. Barrios’ art practice. Sometimes she uses her own voice in live performances; at other times, she highlights the voices and performances of others. In SOMA: Youth and Elders’ VOICES, for example, interviews with Filipino residents of San Francisco’s SOMA district were projected onto a building. In Chatsilog Revisited, her collaboration with M.O.B. recreates the original CHATSILOG project (2008) a performance with the late Filipino American artist Carlos Villa.

In Make Do: part 2 Karaoke Sessions, Barrios turns her focus inward, exploring the voices of her family—especially her mother. “The video is a collection of media from the Barrios family archives, spanning 1980 to 2020,” she explains. “This material has been remixed, layered, and reimagined using newly uncovered footage from my childhood home at 1571 Bubbling Well Drive. It captures key family milestones alongside my late mother's favorite pastime: karaoke. The piece reflects on our lineage, the search for belonging, and the blending of tradition and technology between 1989 and 2008. It offers a glimpse into the lives of one of many Filipino immigrant families striving to ‘make do’ in a foreign land.”

Collaboration—with both people and nature—lies at the core of Hue’s art. After studying fashion at the Parsons School of Design in New York they developed a practice that revolves around mindfulness and embodiment, working on community-centered projects such as the cloud house, a free creative space, and TWYN: Take What You Need, an initiative that provides artists with materials. They use redesigned clothing and bodily adornment to stimulate feelings of positive self-worth. Fuck You to Generational Trauma brings these different areas of their practice together. Working closely with makeup artist Izzy Macala and art writer Oona Robertson, the artist created a region of healing in the desert outside Las Vegas.

In Robertson’s words, this project is “an antidote to generational trauma, using fashion, makeup, and place to construct an alternate world where we have shed our inherited patterns and healed our ancestral suffering by fully becoming ourselves. It depicts Hue and their mother and grandmother as 3 generations of Chinese femmes and immigrants surviving and thriving, but also through its collaborative production incorporates ideas of glamour medicine, drag, and chosen queer family.”

Hue is a cultural worker and multidisciplinary artist based in Las Vegas. They love to dream up ways to contemplate the relationship between nature, the land, and how we adorn our bodies. They are a member of TWYN: Take What You Need, an art supply redistribution artist mutual aid group. They have shown work in spaces around Nevada, such as Left of Center Gallery, the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, and the International Car Forest of the Last Church. They have given artist talks at Meow Wolf, Death Wives, and at the Western Folklife Conference. Previously, Hue worked as a freelance designer for fashion companies. They received their BA from the Parsons School of Design, New York.

“For a while, I’ve been thinking about my family and the traditions that we hold, and observed that we always sing karaoke,” writes Quindo Miller. Karaoke, with its “recurring themes of home, solitude, and repetition,” is a ritual that the family members have in common no matter how far they travel around the globe. This interactive installation shifts the karaoke machine from the domestic closeness of a family home to the space of a museum gallery where visitors are invited to take on the role of the vulnerable yet brave performer who expresses their feelings through song. Miller has chosen songs from 1993 to 2005, a period of time that coincides with their childhood and young adulthood. “That time frame (for me, anyway) seems to stretch endlessly, marked by its own realm of possibilities, distinct from the constraints of adulthood.”

The framed objects on the wall in Endless are titled Homeland. “These artworks are framed pieces of wood veneer salvaged from my grandmother's house in the aftermath of Typhoon Mawar, which made landfall in Guam, March 2023. The pieces of wood were from a closet, painted pink, and Mod Podged with magazines by my mother sometime in the ‘90s. During our visit, we found the pieces, laid them out to dry, then shipped them in a suitcase back to Las Vegas. I rearranged and framed them using matte board and archival tape.”

Born in Guam, Quindo Miller spent their formative years developing an interest in isolation, rituals, and repetition as they explored the island territory’s jungle environment. In 2012, after moving to the mainland United States, they earned a BFA at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Miller’s work investigates their early preoccupations through the mediums of painting, drawing, installation, video, and sound. They have exhibited at venues in Nevada, California, and New York, including the Goldwell Open Air Museum, La Matadora Gallery, the Las Vegas Contemporary Art Center, and Hereart. In 2015 they exhibited in Uttarakhand, India, as part of their PECAH artist residency. Miller lives and works in Las Vegas.

Endless, 2024, steel, rope, tarp, lamp parts, cinder block, wood planks, TV, electronic components, rug, 78 x 173.25 x 80.5 in.

Homeland, 2025, wood veneer, magazines, pink latex paint, Mod Podge, 78 x 173.25 x 80.5 in.

Like many Filipino Americans, Sherwin Rivera Tibayan grew up around balikbayan boxes. The practice of boxing up gifts for family and friends in the Philippines became an entrenched feature of the diaspora in the 1980s as more Filipinos made the journey abroad. When his parents decided to return home after thirty years, he watched them tape up their belongings in the same boxes. “I began to understand a deeper, melancholy truth to this practice: maybe they never wanted to leave. Economic insecurity meant they couldn’t afford to stay; economic success meant they could afford to return.”

Now he uses the same taping process to repurpose balikbayan boxes as museum plinths, placing these signs of transience inside the context of a museum—an institution that tries to imbue objects with stable, lasting value. He writes: “My hope is that the space preserved inside each box has room enough for each of us to imagine and fill it with the ideas and feelings we have about longing (for home, for a person), belonging (to a community, to a family), and belongings (all the objects we give and receive).”

Sherwin Rivera Tibayan is a Filipino American photographer living in Austin, Texas. He uses formal strategies of repetition, multiplicity, obstruction, and visual ambiguity to re-present the various technological structures, tools, and supports that make up and sustain our personal and official photo-documentary histories. His projects have gained recognition from Photolucida, the Magenta Foundation, and the Houston Center for Photography. He received his MFA from the University of Oklahoma. His artwork has been exhibited in Europe, Asia, and across the United States.

Balikbayan Series: Macho, Ate, Junior, 2025, empty cardboard international shipping box, 2-inch archival white artist tape, 17 x 22 in.

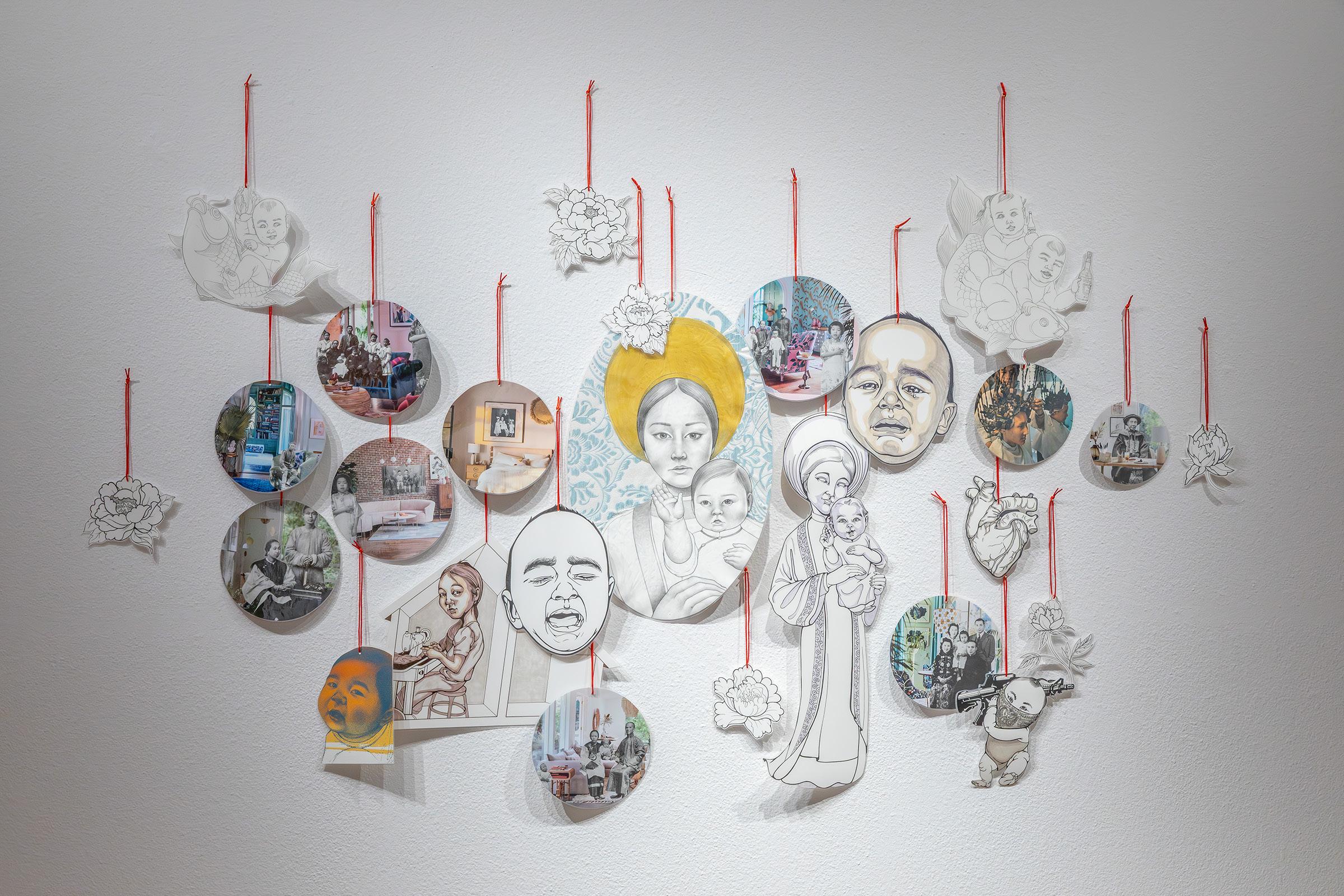

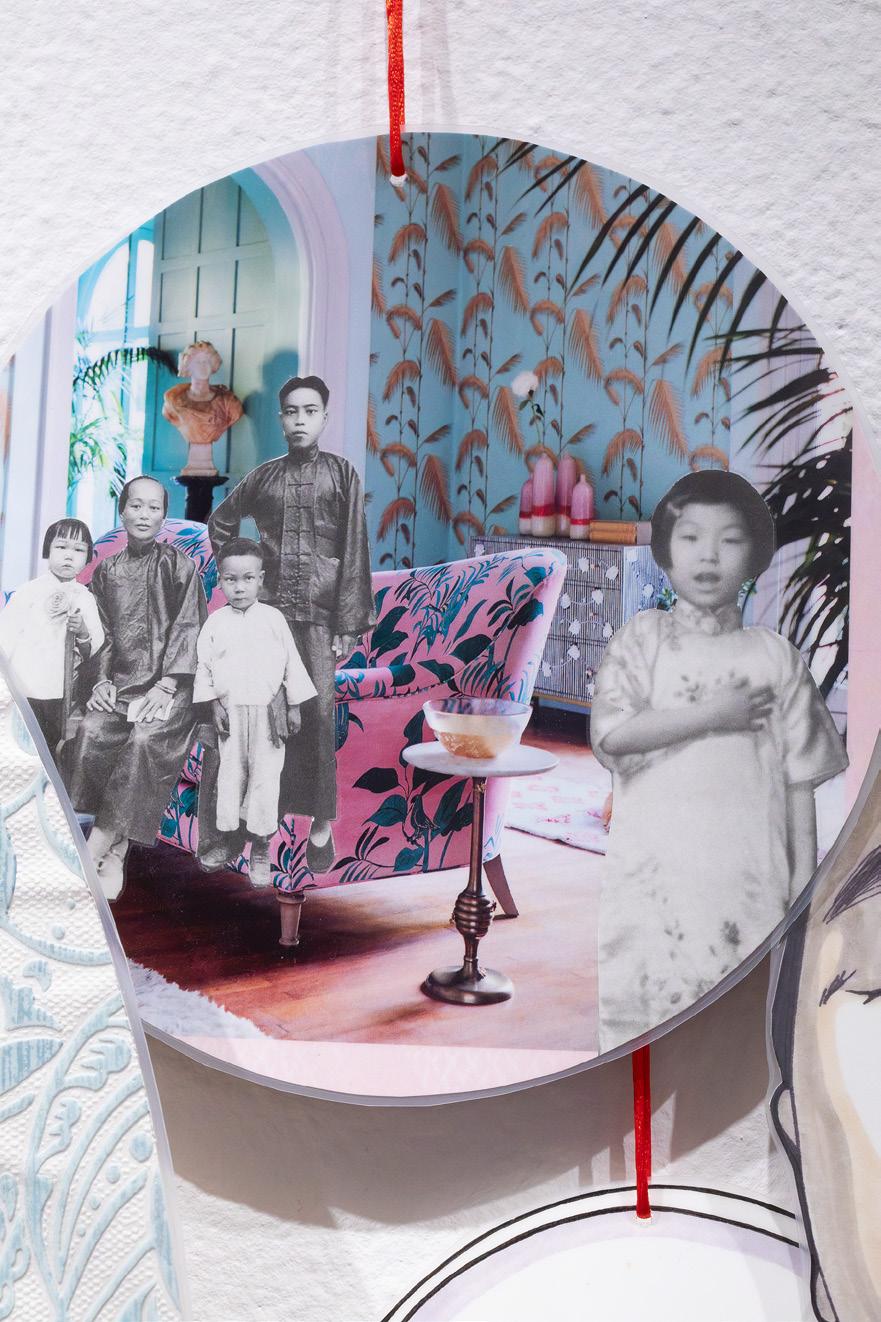

A variety of Chinese and Vietnamese figures intermingle in Phung Huynh‘s Americanization. They include the Lady of La Vang (a vision of the Virgin Mary that manifested in Vietnam’s La Vang rainforest in 1798), a National Geographic magazine image of Chinese women in Shanghai getting a perm in 1980, photographs from a textbook that show one of the first Chinese families in California, and Chinese families in traditional clothing pledging allegiance to the American flag. This amalgamation hints at the challenges that faced Huynh’s Vietnamese family when they arrived in the United States, initially as the first group of Southeast Asians in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, and then as members of a predominantly Chinese community in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. “We had access to language and food that was more similar to our culture,” she remembers, “but we were also othered for not having assimilated. The installation of drawings peels the layers of this complicated journey.”

Phung Huynh is an Assistant Professor of Art at California State University, Los Angeles, where her focus is on serving disproportionately impacted students. She has served as Chair of the Public Art Commission for the city of South Pasadena and Chair of the Prison Arts Collective Advisory Council, which supports arts programming in California state prisons. She served on the Board of Directors for LA Más, a nonprofit organization that serves working class immigrant communities of color in Northeast Los Angeles. Huynh received her MFA from New York University. She is a recipient of the City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship, the California Arts Council Individual Established Artist Fellowship, the California Community Foundation Visual Artist Fellowship, and the Marciano Art Foundation Artadia Award.

Americanization, 2022, mixed media collage, 44.75 x 71 x 1.75 in.

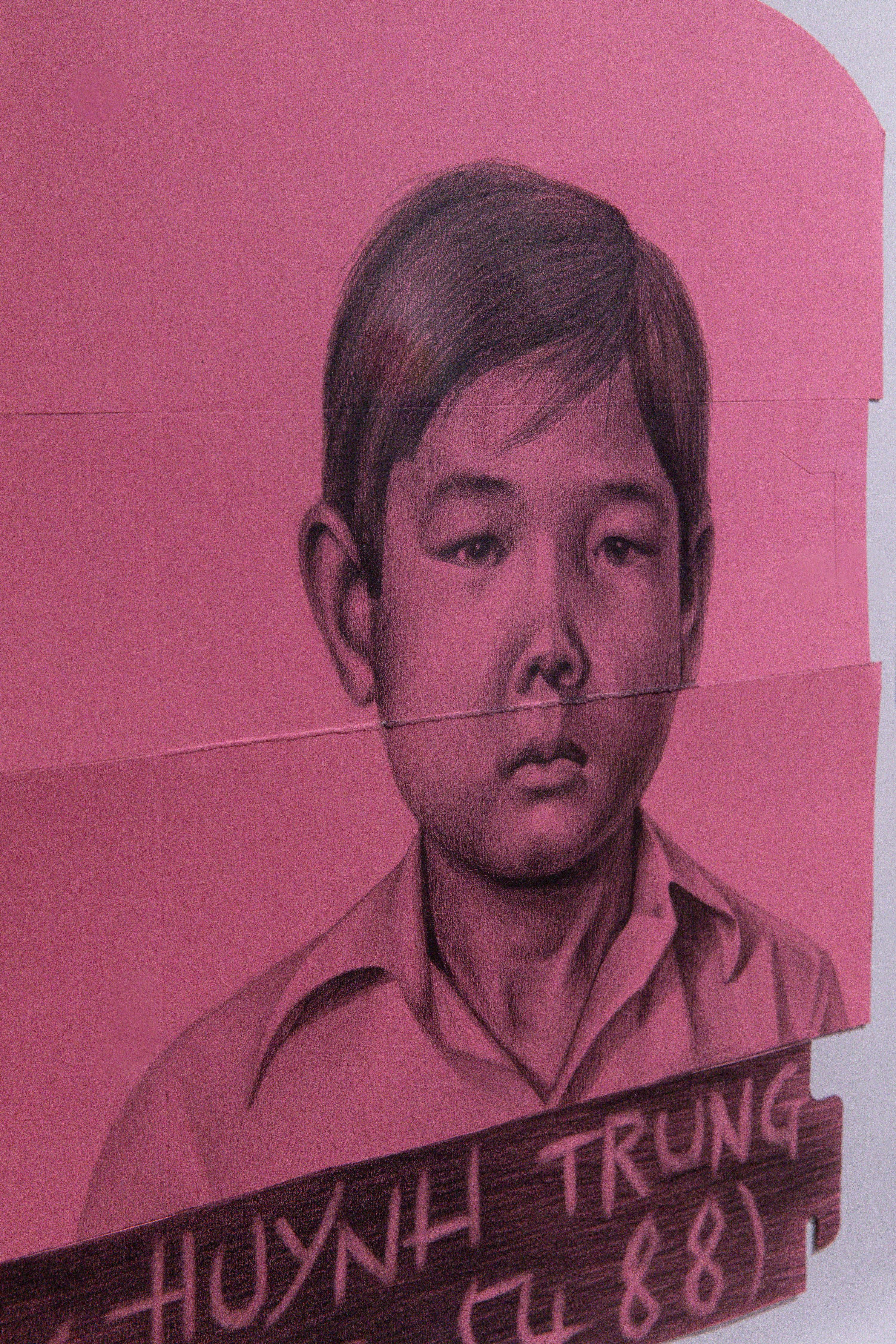

“The first iteration of the pink donut box series started with my immediate family.” In 2019, Phung Huynh began to draw portraits on donut boxes. Starting with resettlement photos of her family in a refugee camp in Thailand–including images of herself as a baby–she expanded the series to include friends, neighbors, and children of other Southeast Asian refugees. The drawings in Living Here depict her grandparents and older brother. “I have a very complicated relationship to photographs and portraits because when we left, we couldn't bring any photos with us,” she explained to NPR in 2022. “And we use photographs to worship our ancestors.” Pink boxes became a staple of donut stores across large areas of the US after Cambodian American store owners in California began using them in the 1980s. Today, roughly 80% of all donut outlets across California are owned by Asian Americans. Huynh says she hopes her work will uplift her community and save her children from forgetting “where they come from.” “Making this body of work on pink donut boxes has always been my desire to pass on the story to my children. I’ve always wanted to do that.”

LEFT–RIGHT

“Although I’ve come to appreciate this early engagement with my heritage and culture, being forced by my parents to put on a plaid shirt and neck scarf and perform Filipino folk dances seemed extremely uncool at the time.” In Dancing Shoes, Michael Rippens reflects on his childhood experience performing Tinikling, a traditional dance where bamboo poles are clapped together in a rhythmic beat. He recalls it was often painful—both physically, as his feet were often caught between the heavy poles, and socially, as a junior high kid in Los Angeles navigating the challenge of fitting in with his peers.

For this work, Rippens altered a wooden relief of young Tinikling dancers, a common decoration in Filipino households. He handcarved sneakers for each figure, outfitting their bare feet in brandname shoes that were popular when he was growing up. The bamboo poles were replaced with jump ropes, giving the impression that the dancers were just regular American kids having fun on a playground. “The changes I made to the original sculpture allude to the internal conflicts and contradictions I felt as a child navigating a hybrid identity.”

Michael Rippens is a multidisciplinary artist whose work focuses on public, participatory, and socially-engaged art projects. Employing a range of media including performance, audio, video, installation and sculpture, he considers issues surrounding systemic inequities, and imagines alternative ways to bridge gaps in existing structures. As a biracial Filipino-American, Rippens draws inspiration from his personal and family history to explore multiple—and multilayered— backgrounds and perspectives, engage with diverse communities, and amplify unheard narratives. Rippens earned a BFA in painting from Pratt Institute in New York. He has exhibited his work and created performances across the United States. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Dancing Shoes, 2021, wood, paint, wire, plastic, 46.5 x 78 x 2.25 in.

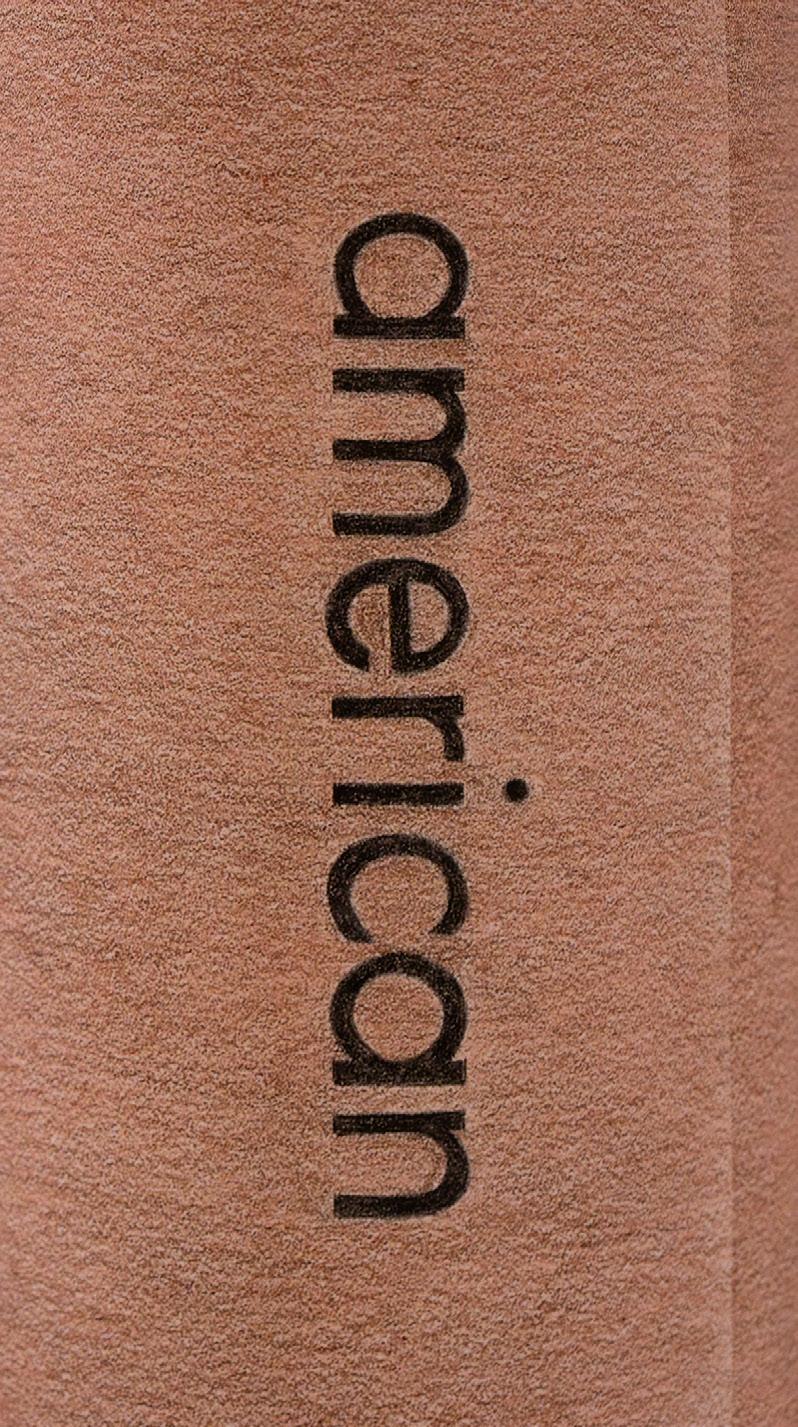

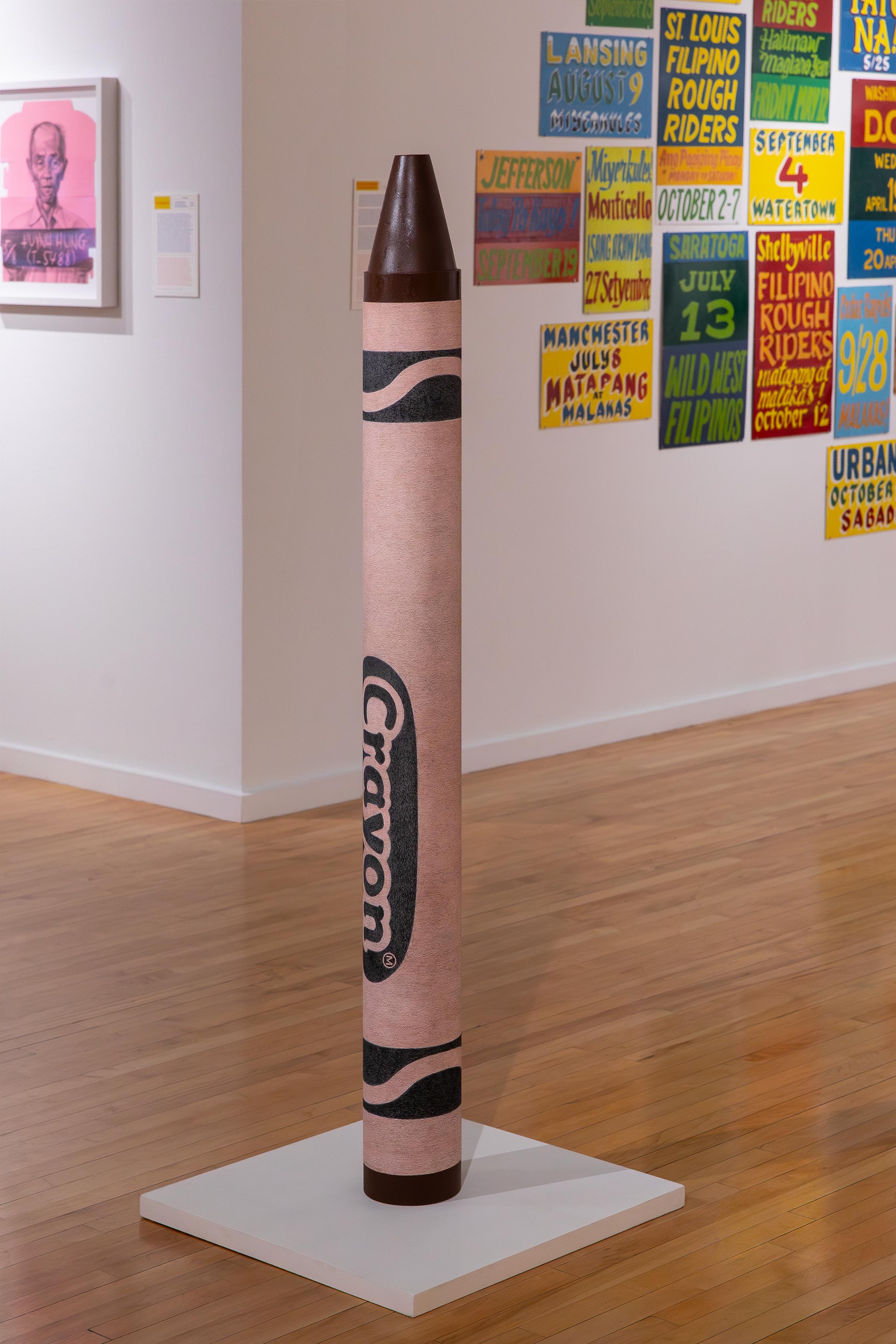

Mendoza is inspired by the mid-century Fluxus and Pop art movements, especially the work of the American sculptor Claes Oldenburg (19292022), who is best known for creating giant versions of common objects such as hamburgers and spoons. “When I manipulate scale, I think it might be able to stimulate perception or possibly create an environment where a viewer might take a bit more time with a piece, observe it more closely, or take an opportunity to ponder what’s in front of them,” she told the Picture This Post website in 2022. Here, she enlarges a crayon to the height of her own body, labels the color “american,” and titles the sculpture with the Tagalog word for the brown tone of Filipino skin. “Kayumanggi not only specifies language and location, but becomes a source of pride in skin color and cultural values.”

Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores personal narratives, material significance, and history. As a 1.75-generation immigrant, her identity was shaped by perspectives and experiences that continue to unfold through her work in drawing, sculpture, and installation. Since 2001, she has served as an Associate Professor and Drawing Coordinator in the Visual Arts and Media Studies Division of Pasadena City College. From 2022–24, she served on the board of FilAm Arts (The Association for the Advancement of Filipino-American Arts and Culture). Mendoza earned her MFA from the Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. Her work has been exhibited in the United States, Canada, and the Philippines.

Kayumanggi, 2019, plastic, wood, paper, colored pencil, Giclée print, 59 x 6 in.

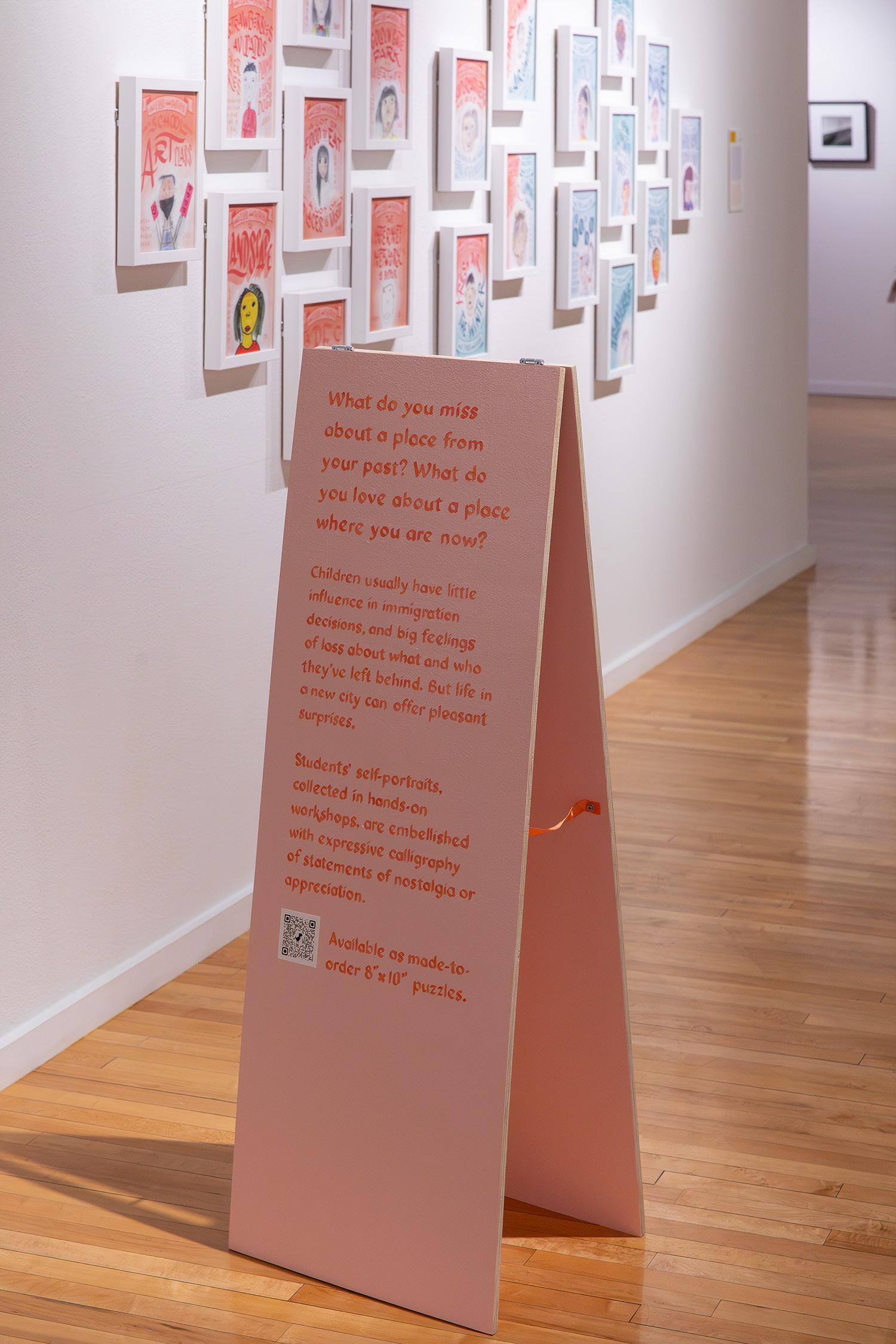

with students from Edwin and Anita Lee Newcomer Elementary

“I like to think that asking people to respond to questions about their interior life creates much-needed space for self-reflection,” Christine Wong Yap told the Othering & Belonging Institute in 2019. What I Love and Miss was originally part of her Recognitions / 认 • 知, a project aimed at articulating feelings of belonging in children who had recently migrated to the United States. Her collaborators were students from a one-year scholastic program in San Francisco Chinatown. For the past two decades, Yap has been shaping her artistic practice around optimism and happiness, drawing on the work of scholars such as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi whose studies in positive psychology counterbalance the more common psychological focus on recovering from trauma. Yap likens this to preventative medicine, pointing out that it's beneficial to maintain good health, and less beneficial to allow negative symptoms to accrue before treating them. She worries that people tend to dismiss happiness as an unserious area of research, seeing it as something that can be simply felt and understood rather than a multifaceted process that can be investigated. The interactive component of What I Love and Miss invites us to gain insights into our feelings about belonging in a safe and constructive way.

Christine Wong Yap is a visual artist and social practitioner who works in community engagement, drawing, printmaking, publishing, textiles, and public art. Through her hyperlocal participatory research projects, she gathers and amplifies grassroots perspectives on belonging, resilience, and mental well being. She is a 2025 Creative Capital Awardee. From 2023 to 2024, she served as Neighborhood Visiting Artist at Stanford University. She has developed projects with the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco, For Freedoms, the Library Foundation of Los Angeles, the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, Times Square Arts, and the Wellcome Trust, among others. Holding a BFA and MFA in printmaking from the California College of the Arts, she lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area.

What I Love & Miss, 2022, series of 20 portraits with calligraphy: social practice, drawings, inkjet prints, 34.25 x 136 x 1.25 in.

What I Love & Miss, 2022, series of 20 portraits with calligraphy: social practice, drawings, inkjet prints, 34.25 x 136 x 1.25 in.

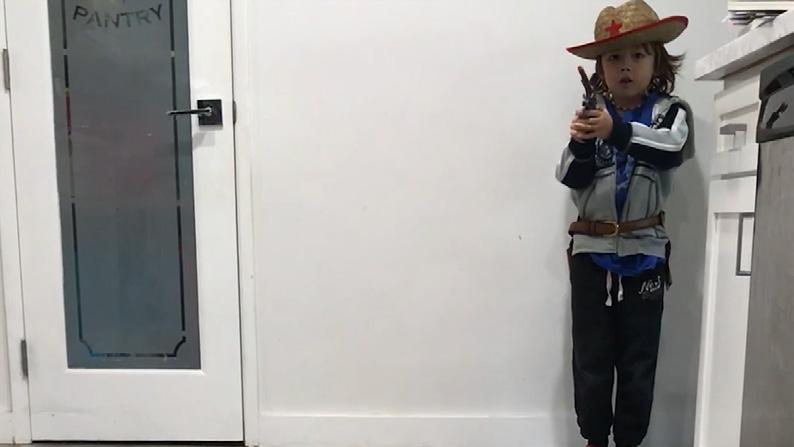

“My children are mixed-race, as are many of my neighbors' and friends’ kids. Living in America, I quickly realized that race, like gender, was a constant undercurrent shaping the way identities are perceived and internalized,” writes Ching Ching Cheng. “The question of belonging, of how they saw themselves versus how the world categorized them, became an ongoing dialogue in our family.” She articulates that dialogue in this video by juxtaposing footage of her son and daughter with excerpts from a movie that she herself loved when she was growing up in Taiwan—好小子 (Young Dragons: Kung Fu Kids), a 1986 comedyaction film about three boys who use their martial arts skills to protect themselves against the movie’s villains. As an adult, Cheng reflected on the resilience of the boys and how, as a young girl, she was kept away from the kinds of experience that would have helped her develop an equivalent level of confidence. In Kung Fu Kids, we see two small individuals working out how to grapple with the media they consume and the cultural pressures that surround them. “For my children, for myself, and for many others navigating this complexity, this project is both a reflection and an open-ended conversation—one that continues to unfold with every generation.”

Ching Ching Cheng is an artist, filmmaker, and art educator based in Los Angeles. She is interested in the relationship between our identities and the spaces we live in, specifically how the physical environment relates to and affects gender, culture, society, economics and politics. She received her MFA from the ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena in 2020. Cheng has exhibited her work at institutions in Taiwan, China, and the United States, including the Chinese American Museum, the Craft and Folk Art Museum, and Los Angeles International Airport.

Kung Fu Kids

, 2019, 5 minute single channel video, video stills

Dogs

Cats and Dogs brings a maneki-neko—the figure of a cat beckoning us closer—together with a video of Snoopy Come Home, an animated movie about a pet dog who feels emotionally torn between two owners. The maneki-neko originated in Japan, but it has been adopted by other Asian cultures. In the United States it is often seen welcoming customers into Chinese American restaurants and stores. The blank TV screen suggests indecision—what will it “play”? By choosing a VHS tape and a CRT monitor, rather than a contemporary digital stream on a flatscreen TV, Shih places the decision away from us in time, hinting that this moment of choosing between different locations can be recalled but never recovered.

Stephanie H. Shih renders outdated consumer goods as painted ceramic sculptures that explore the way cultural identities transform as they migrate with a diaspora. In replicating everyday objects, she reflects on the traces of colonization, emigration, assimilation, and cultural interchange within the lives of Asian immigrants and their children. She has exhibited her artworks in museums and galleries across the United States. Community work is central to her practice. Since 2017, she has raised over half a million dollars in direct aid for victims of state violence. Shih is currently based in Brooklyn, New York.

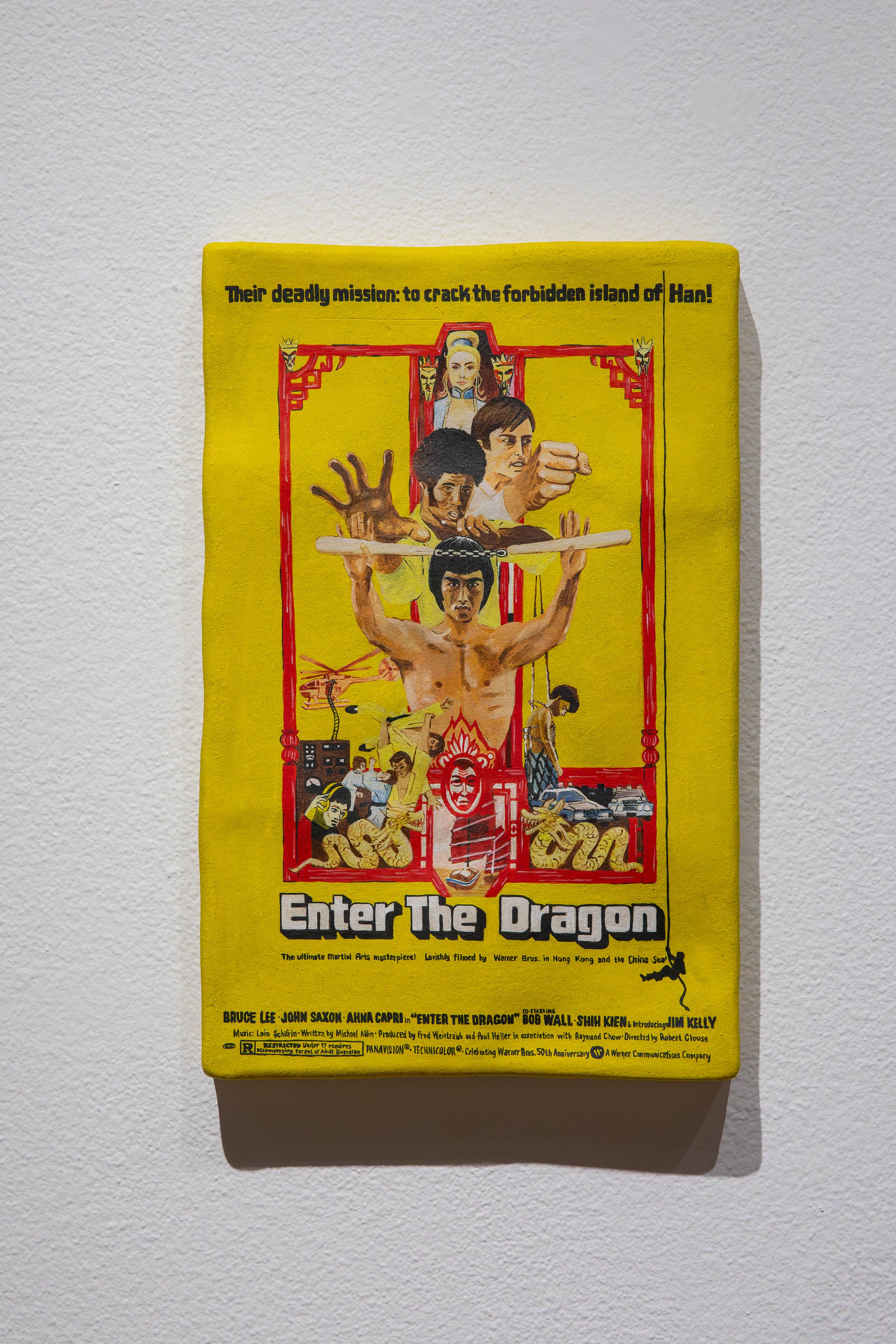

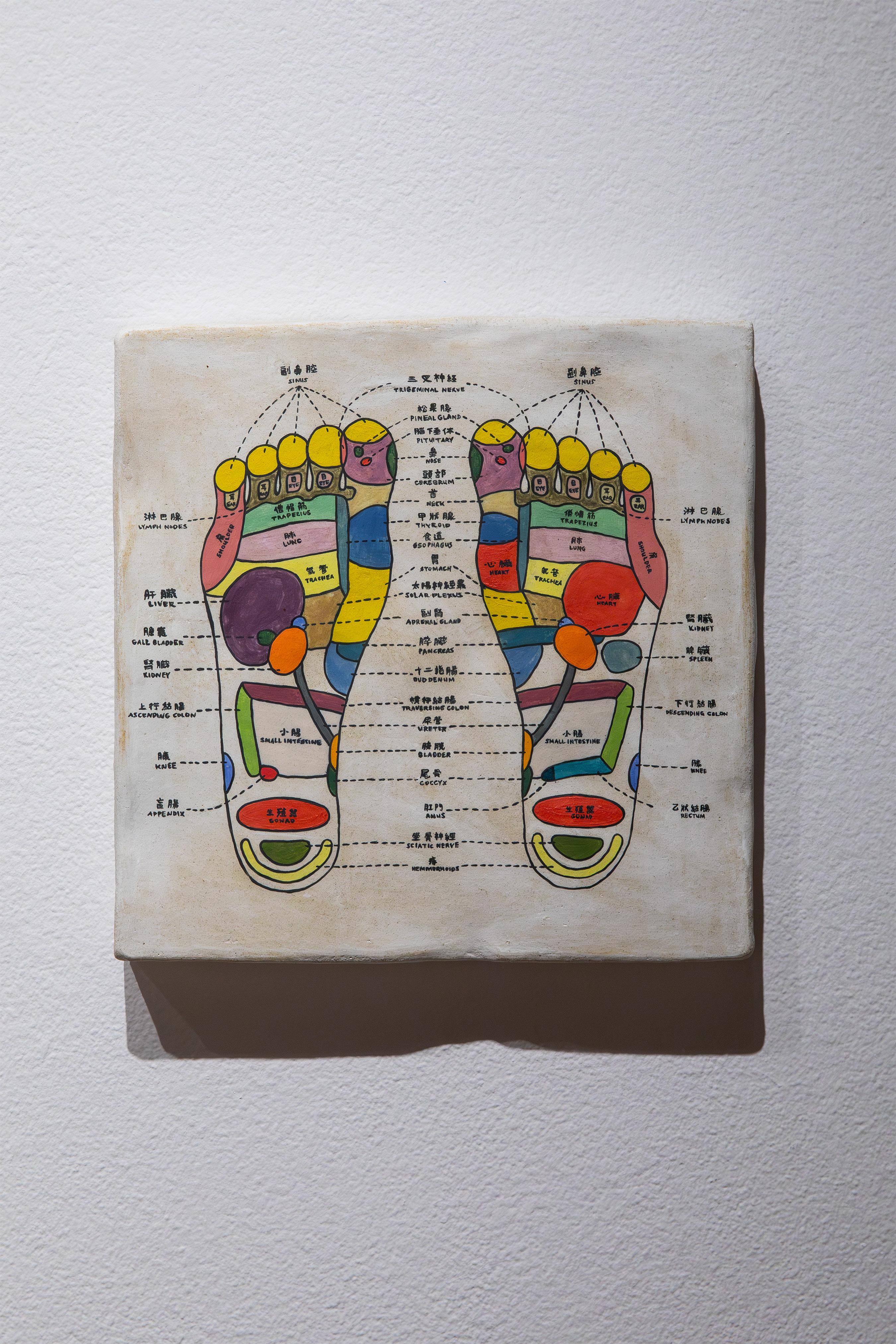

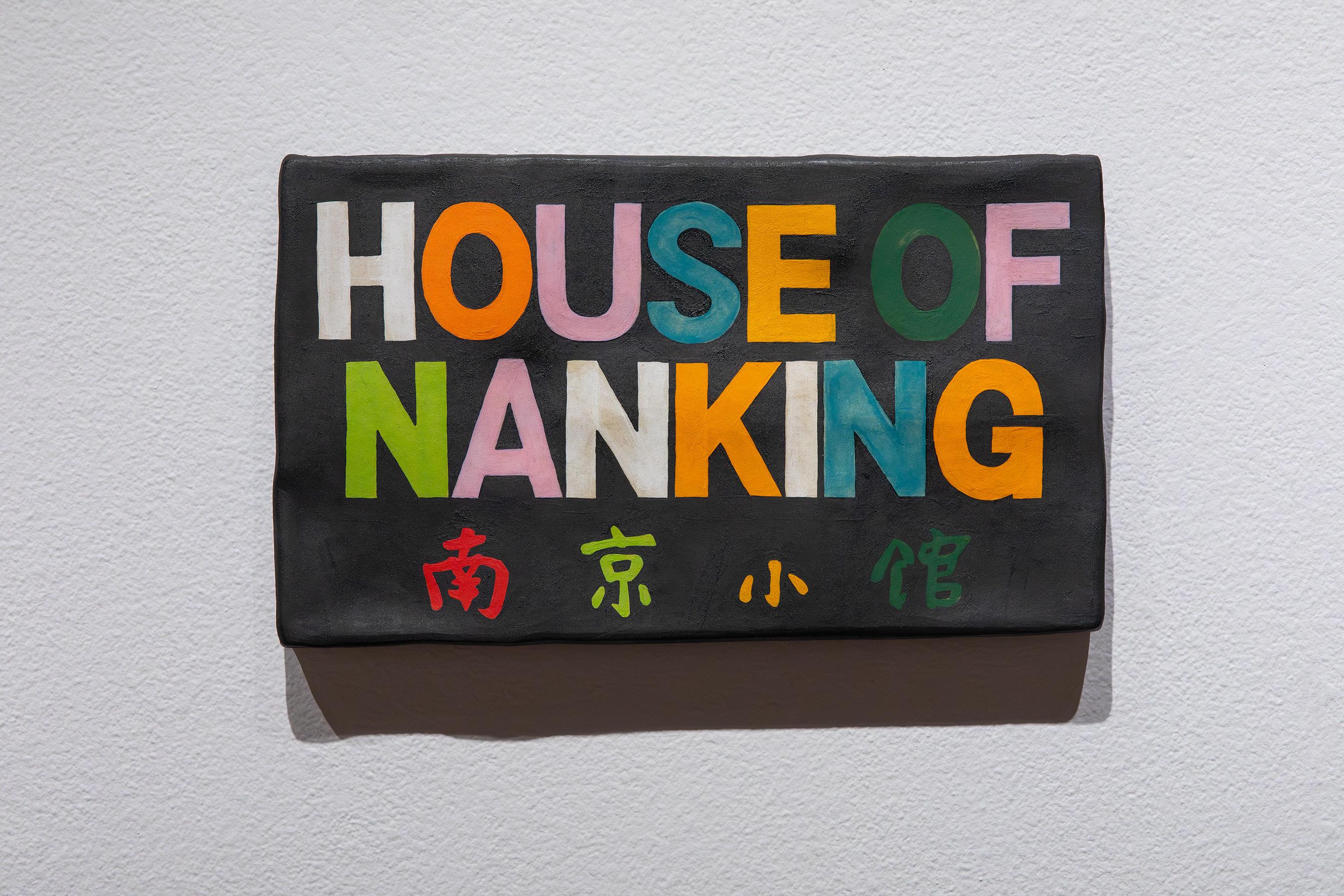

These artworks belong to a series that explores the history of the first Chinatown in the United States, in San Francisco. House of Nanking (1988), 919 Kearney St. replicates the sign of an iconic restaurant founded in 1988 by Peter and Lily Fang, who emigrated from Shanghai in the early 1980s. Enter the Dragon is arguably the most famous movie starring the 20th century’s most widely known Chinese American actor, Bruce Lee. Lee was born in San Francisco's Chinese Hospital in 1940. The film premiered one month after his death in 1973. Reflexology Chart recreates a poster often seen in the city’s Chinese American massage parlors. Hand-crafted and tactile, as if made to be held, these ceramic sculptures hint at the day-to-day experiences of life in one specific area of the diaspora.

STEPHANIE H. SHIH

Enter the Dragon, 2023, ceramic, 17 x 10.5 x 1.75 in.

OPPOSITE Reflexology Chart, 2022, ceramic, 13 x 13.25 x 1.75 in.

TOP House of Nanking (1988), 919 Kearny St., 2022, ceramic, 10 x 17 x 2 in.

RIGHT

Crab Rangoons (detail), 2022

Courtesy of the artist and Berggruen Gallery

In 2018, Shih created porcelain sculptures of the dumplings she remembered folding as a child with her aunties and posted them online. The response from her Asian American audience was immediate. She began sculpting other foods that reminded the community of their childhoods in the diaspora—grass jelly, Ligo brand sardines, one-gallon cans of Kikkoman soy sauce. Sculpted and painted by hand, each clay foodstuff was a tangible connection to shared memories that gave the community a sense of belonging. Over time, the artist expanded her repertoire of foods that speak about other areas of Asian American experience. Crab rangoons, for example, were invented in California in the mid-1950s. Today they are a staple of Chinese American restaurants that cater to a non-Asian clientele.

STEPHANIE H. SHIH

OPPOSITE

Salmon Tail (detail), 2021

TOP–BOTTOM

Scallion, 2020, ceramic, 0.75 x 13 x 2 in.

Crab Rangoons, 2022, ceramic, 2 x 6.75 x 7.5 in.

Salmon Tail, 2021, ceramic, 2 x 9 x 4.75 in.

Courtesy of the artist and Berggruen Gallery

“Creating beauty and finding beauty are really important to me,” Sush Machida told CMH magazine in 2009. He mingles motifs from both Japan and America to create a third place derived from his personal fantasies: an independent landscape of bright colours, springy curved lines, action, humor, fishing, and toys. His style is often compared to American pop art, but he points out that “In Japan’s art world, painting pop culture is not a new thing, it is an old thing. Andy Warhol started in the 1960s, the Japanese started in the 16th century–patterns, logos of department stores and woodblock prints—I guess that is in my DNA.” By frequently using arthistorical references and brands rather than realistic images, he asserts the power of his imagination to turn artificiality into a new reality. (The banana in Tiger is doubly removed from the reality of an actual banana, since it is not only an artwork by Andy Warhol, but also the cover picture from The Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut album.) “My culture—street culture, skaters’ culture—is about graphics, graffiti, tattoos and things like that,” he said to CMH. “I deal with traditional Japanese subject matter—tigers, dragons, flowers, waves and wind. Using old subject matter and making it new is really challenging.” Machida has described the feeling of being slightly removed from the mainstream as an essential part of his artmaking, drawing parallels with his status as both an artist and an Asian in the United States.

Atsushi “Sush” Machida is a Japanese artist who combines contemporary and ancient images in painted compositions that prioritise artificiality, beauty, and imagination. He was based in the United States for approximately three decades. After attending Utah State University he moved to Las Vegas to join the Fine Art graduate program at UNLV under the guidance of the late art critic Dave Hickey. He received his MFA from UNLV in 2002. Machida’s work has been exhibited internationally and across the United States.

RIGHT Tiger, 2007, acrylic on panel, 72 x 16 x 1.75 in.

BOTTOM

Crank Up the Deep Divin’ Ultra 3, 2001, acrylic on panel 16 x 96 x 1.5 in.

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection. Gift of the Las Vegas Art Museum, 2021; Gift of an anonymous donor, 2008. 2021.08.151

Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Collection. Gift of the Las Vegas Art Museum, 2021; Gift of Cliff Benjamin, the Western Project, 2012. 2021.08.189

Growing up in an Evangelical Christian household, Daieny Chin felt a tension between their family’s religious beliefs and the indigenous Korean folktales and myths they heard from their mother. These paintings from their Mythos Unveiled series juxtapose those two ways of understanding the world. “I wanted to depict that spiritual dichotomy I’ve always felt,” Chin writes. In a cat stretches, the artist’s personal meditation on grief following a miscarriage is illuminated by an item of Christian pop culture (a Precious Moments candle) and accompanied by a Korean vase painted with the mythological figures of snake and tortoise, indicating conflict and also balance, as in the symbol of yin and yang. The objects are close by, but Chin depicts themselves gazing away from them. The same mythology carries over into Tortoise and Snake, where the two animals encircle the figure of a girl with ram’s horns–a reference to the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1853 painting, Tête de femme coiffée de cornes de bélier (Woman’s Head with Ram’s Horns), another work that blends mythology with then-contemporary life. “Rams are a symbol of sacrifice in Biblical context,” Chin explains.

In Angel’s Trumpet they are holding a pigeon. Chin calls it “strange” that pigeons are seen as inherently dirty when they’re part of the same family as doves, which Western culture presents as pure, sanctified birds. “Doves are an important symbol in Christianity, so I wanted to give pigeons the same tenderness.” The artist describes the angel’s trumpet flowers, like the Christian dove, as symbols of rebirth and spiritual connection. Meanwhile, Cut Fruit looks at the family as a site of comfort and connection. “Growing up, my family would cut fruits after every dinner for dessert and a place to bond. In Korean culture, we show love through acts of service. The act of meticulously peeling the skin and cutting the fruit for others shows how much we care for one another.”

Daieny So Won Chin creates introspective artworks that bridge the gaps of identity, culture, personal narratives, and human connection within the Korean diaspora. They graduated from San Francisco Art Institute in 2018 with a BFA in painting. Their work has been exhibited in New York, California, and the United Kingdom. Chin currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

DAIENY CHIN

CLOCKWISE

Cut Fruit, 2024, oil on canvas, 28 x 34 in.

a cat stretches, 2024, oil on canvas, 20 x 24 in.

Tortoise and Snake, 2024, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in.

Angel’s Trumpet, 2024, oil on canvas, 30 x 30 in.

“I grew up in Los Angeles where most people view coyotes as a nuisance, or a pest. But I've always seen similar traits such as resilience, strength, and perseverance my grandmother shared with coyotes, and her experience moving to the States as an immigrant.“In Coyote Ugly, Daieny Chin imagines their maternal grandmother’s younger self coming into contact with a coyote–a physical manifestation of indigenous America. The young woman has lowered her body so that she and the animal are meeting at a roughly equal height. Her hand offers a cluster of medicinal yarrow flowers, an expression of healing, to affirm the encounter. “I think about the perils of my grandmother to coyotes and how Asian people were seen and sometimes still are seen as nuisances and invasive,” Chin told Filo Sofi Arts in 2024. “My grandmother still adapted to the city and really really thrived here.”

“My grandmother and I had a significant language barrier between us, which often left me filling in the blanks of who I thought she was.” Daieny Chin’s paintings are peopled with mothers, daughters, grandmothers, and aunts, reflecting the artist's upbringing in an immigrant matriarchy. Hybrid Body is part of a series of works dedicated to their maternal grandmother. In it, they picture their grandmother wearing a traditional European-American dress paired with a daenggi— a type of ribbon often worn by unmarried Korean women. Both aspects of the costume are brought together in a single coherent form. The sense of unity is underlined by Chin’s emphasis on the figure’s interwoven hands.

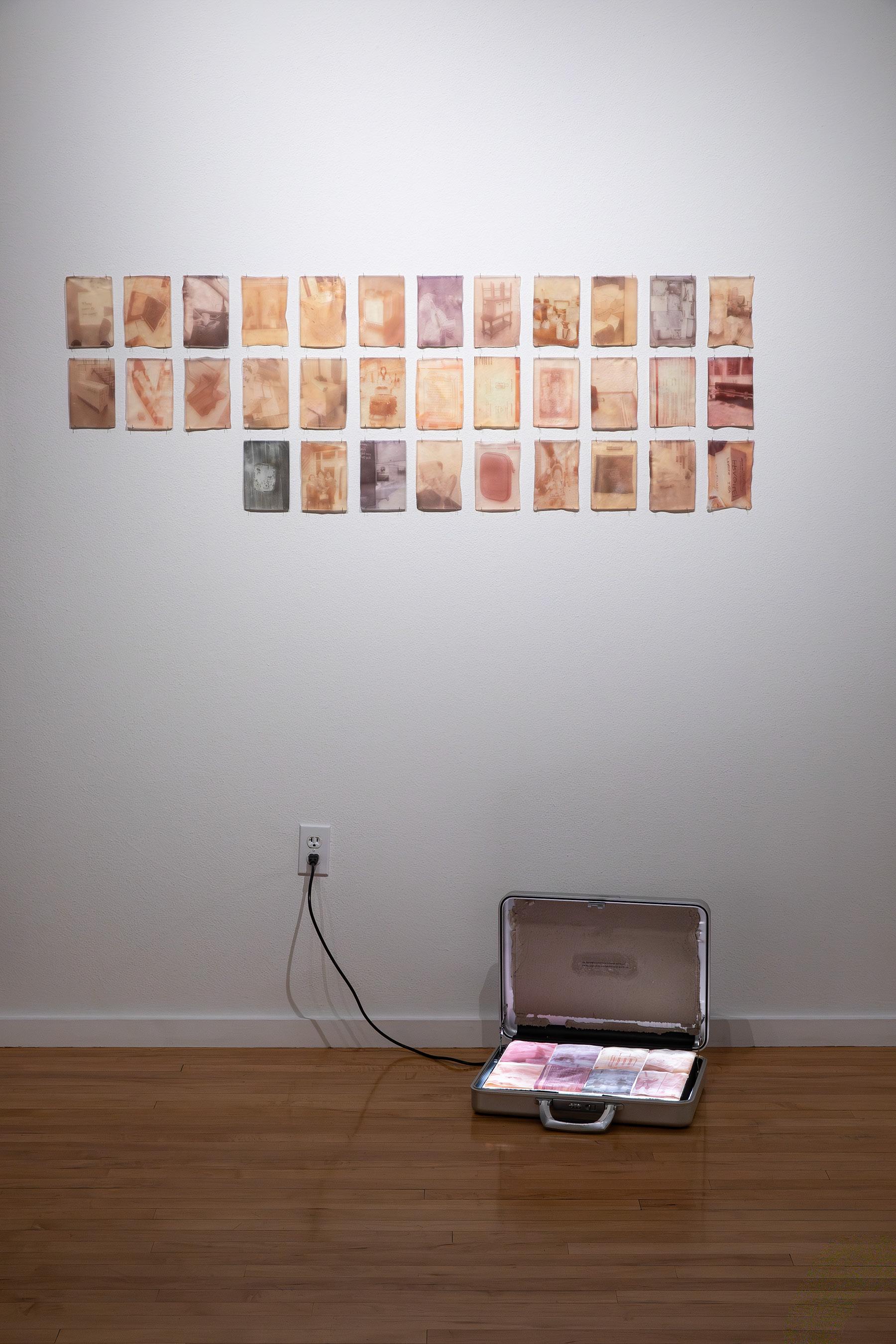

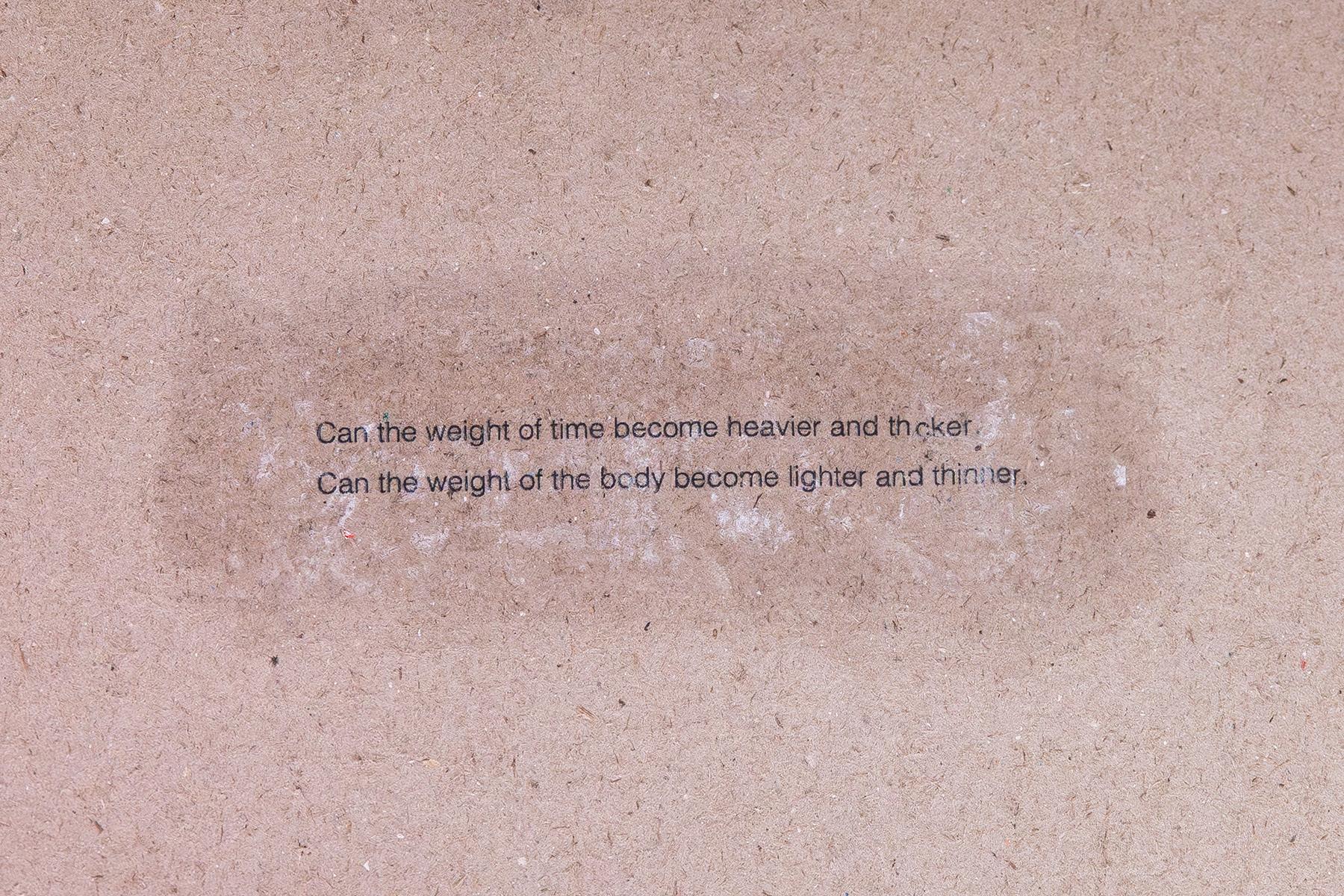

These two artworks unite dual meanings of the phrase “carry on” with a homage to the Synecdoche (1991–present) by the Korean American artist Byron Kim. By filling a grid with squares of color representing the skin tones of people who sit for his “portraits,” Kim imbues an apparent abstraction with a private depth of meaning. Similarly, Chung uses her personal experiences to fill the space of the words “carry on” with new intent. The textured rectangles in these works are cast from the surface of her body and tinted with the color of her skin. “Carry on” is both the carry-on luggage she keeps close to her when she flies between Korea and her new home in the United States, and a phrase she uses to give herself strength as she endures the stress of the migration process. “Both meanings carry weight for me physically and emotionally,” she explains. “I am interested in how a body carries time and how those carriages mark their index on the body. I think about how the intangibility of time and language holds the body’s tangibility.”

Embedded in the resin casts we see images that a search algorithm— responding to a request for “carry on”—chose from a gallery of pictures she created after she moved to the United States. They range from a screenshot of the guidelines for luggage sizes on planes to a photo of her grandmother holding a handbag. Chung invites us to expand language to be more capacious. “Here,” she writes, “the term carry on becomes a broader term for a container that can hold something.”

Jisoo Chung is a multimedia artist who uses video, installation, drawings, and performance to track the sociocultural power in language and names. A search for the loss of identity evoked by linguistic failures is where her works begin. Her recent film, Miss Kim Lilac (202324), won the Jungwoon Award from the Seoul Experimental Film and Video Festival. She has presented her work internationally in Europe and Asia as well as the United States. Chung holds an MFA from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a BFA from Seoul National University. She has been a production committee member of the Los Angeles-based diasporic Korean artist collective, GYOPO.

JISOO CHUNG

Carry On, 2024, resin cast of the artist’s skin, submerged photo printed on clear film, 6 x 4 x 0.75 in.

Can The Weight Of Time Become Heavier And Thicker, Can The Weight Of The Body Become Lighter And Thinner., 2025, briefcase, LED, resin, photo, clear film, 15.5 x 18.25 x 17 in.

OPPOSITE

Carry On (detail), 2024, resin cast of the artist’s skin, submerged photo printed on clear film, 6 x 4 x 0.75 in.

RIGHT

Can The Weight Of Time Become Heavier And Thicker, Can The Weight Of The Body Become Lighter And Thinner., 2025, briefcase, LED, resin, photo, clear film 15.5 x 18.25 x 17 in.

Growing up in South Korea, Jisoo Chung found herself both attracted and repulsed by the nation’s enthusiasm for new technology. The “prominent societal values of ‘productivity’, ‘efficiency’, and ‘functionality’ led me to question systems such as instruction, rules, and codes that are often used in technology,” she writes. Her skepticism towards unthinking rule-making became sharper after she moved to the United States in 2017 and found herself trying to navigate unfamiliar terms and jokes in a new language with its own set of grammatical expectations–English. Her practice evolved to focus on the places where dominant structures create a rift with reality. Jason was inspired by the English-language autocorrect technology that constantly changes her first name from “Jisoo” to “Jason.” By turning her own body–her hands and voice–into a Jason-identifying machine, she draws attention to the ludicrous confidence of the systems that insist on wedging her into a category where she doesn’t belong.

In 2009, the artist E.G. Crichton paired other artists with the archives of queer ancestors for a project titled Lineage: Matchmaking in the Archive. That was how TT Takemoto encountered Jiro Onuma. Onuma migrated from Japan to the United States when he was nineteen. In 1942, at the age of thirty-eight, he became one of roughly 120,000 people of Japanese descent who were incarcerated after America declared war on Japan. “Seeing Onuma’s photographs … startled me,” writes Takemoto. “They opened my eyes to the presence of LGBT individuals in the American concentration camps and connected me to this history of wartime imprisonment in a whole new manner.” The artist’s research resulted initially in a group of handmade objects titled Gentleman's Gaman: A Gay Bachelor's Japanese American Incarceration Camp Survival Kit, and then in Looking for Jiro. Takemoto describes Jiro as a “a queer experimental video featuring an ABBA/Madonna mash-up, drag-king performance, US war propaganda footage, muscle building, and homoerotic bread making” that “conjures up an alternative campy world in which Onuma can dream of musclemen as a way to keep his queer imaginary alive amid the loneliness and despair of incarceration.“

Takemoto’s research into Onuma revolved around a number of questions. “What internal and external factors have contributed to the invisibility of same-sex intimacy and queer sexuality within the collective memory of Japanese American wartime history? How does the Onuma collection complicate and expand existing incarceration camp histories, memories, and representations? Is it possible to form personal and affective attachments to queer individuals and absent memories through the objects and materials they leave behind? These questions challenge me to consider what is at stake in the process of looking for Jiro Onuma in the mute photographs and ephemera that constitute his material remains.” Looking for Jiro won the Best Experimental Film Jury Award at the Austin LGBT International Film Festival in 2012. It has been screened in dozens of festivals and exhibitions.

TT Takemoto is a queer Japanese American artist and scholar who interacts with found footage and archival materials to explore Asian American history, sexuality, and identity. Their work delves into hidden dimensions of same-sex intimacy and trauma existing within Asian and Asian American archives. Takemoto holds a PhD in Art and Art History from the University of Rochester, and an MFA from Rutgers State University of New Jersey, Mason Gross School of the Arts. They have exhibited artworks and appeared in film festivals in Asia, Europe, and throughout North America. Their writings have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. They were a member of the Queer Cultural Center’s Board of Directors and co-founder of Queer Conversations on Culture and the Arts. Takemoto lives and works in the San Francisco Bay Area, where they are a professor at the California College of the Arts.

Looking for Jiro, 2011, single-channel digital video with sound, 5 min, 45 sec, video stills

“The contributions of Chinese Americans have often been devalued or omitted,” Jeannie Hua told Double Scoop in 2023. “It makes me think about what we base our knowledge of history on. How legitimate are records made by those in power? They’re not objective. It’s what people record that is passed down. I have no choice but to make tracings out of the traces of history that I glimpse and add them to that record.” In Meditation, she lulls the viewer with the language and music of a soothing mindfulness session before asking them to meditate on something very different. The video is part of Did You Know Chinese Americans Fought in the American Civil War?, a body of work inspired by Hua’s research into the approximately fifty Chinese Americans who served in both Confederate and Union armies.

"Take a walk in the woods and discover your mind can take you to places you’ve never imagined, the lived experience of another transcends time, space, and cultures." —Jeannie Hua

Jeannie Hua is a Las Vegas-based artist who uses collage, sculpture, and other media to bring underrecognized aspects of United States history subversively into the spotlight. She received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2022. Her work has been exhibited in the United States and France. She was the recipient of the Denis Didero Grant, Nevada Council of Arts Grant, as well as a merit scholarship to Ox-Bow School of Art.

Meditation, 2022, video, 3 min, 52 sec, video still

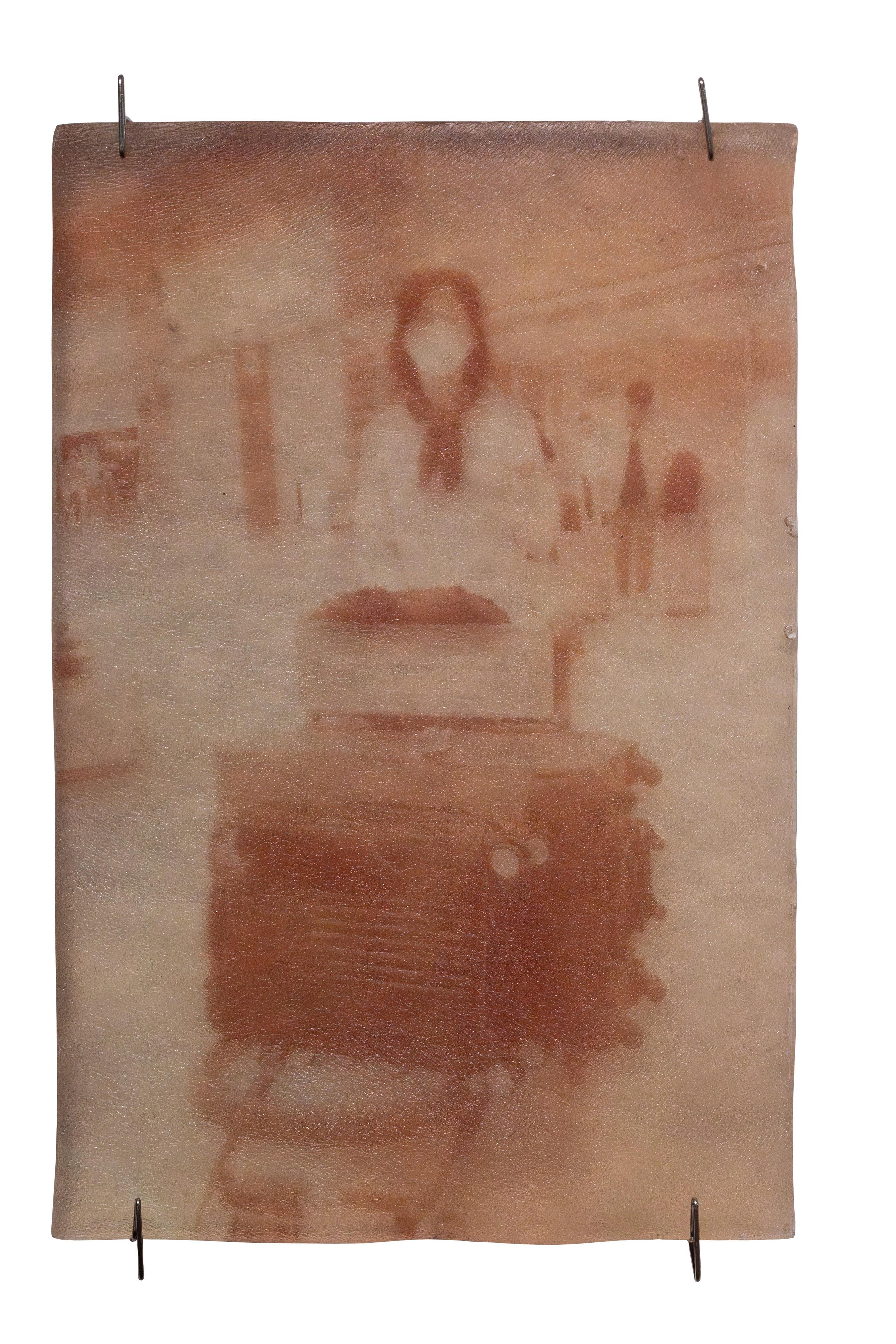

In 2022, Emmanuel David and Yumi Janairo Roth came together to research a group of Filipino performers who toured the United States around the turn of the 19th century. The Filipinos joined the Rough Riders of the World performance in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveling show soon after the United States annexed the Philippines at the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898.

David and Roth tracked the group through traces left in the archives: a name in a logbook, a face at the edge of a photograph. In their project, the ephemera that only faintly marked the Filipinos’ presence when they were alive is reimagined with them as the stars. Noting that the advertising blitz for the Wild West show always focused on one name—Buffalo Bill—the artists have worked collaboratively, foregrounding the relationships that form within a collective.