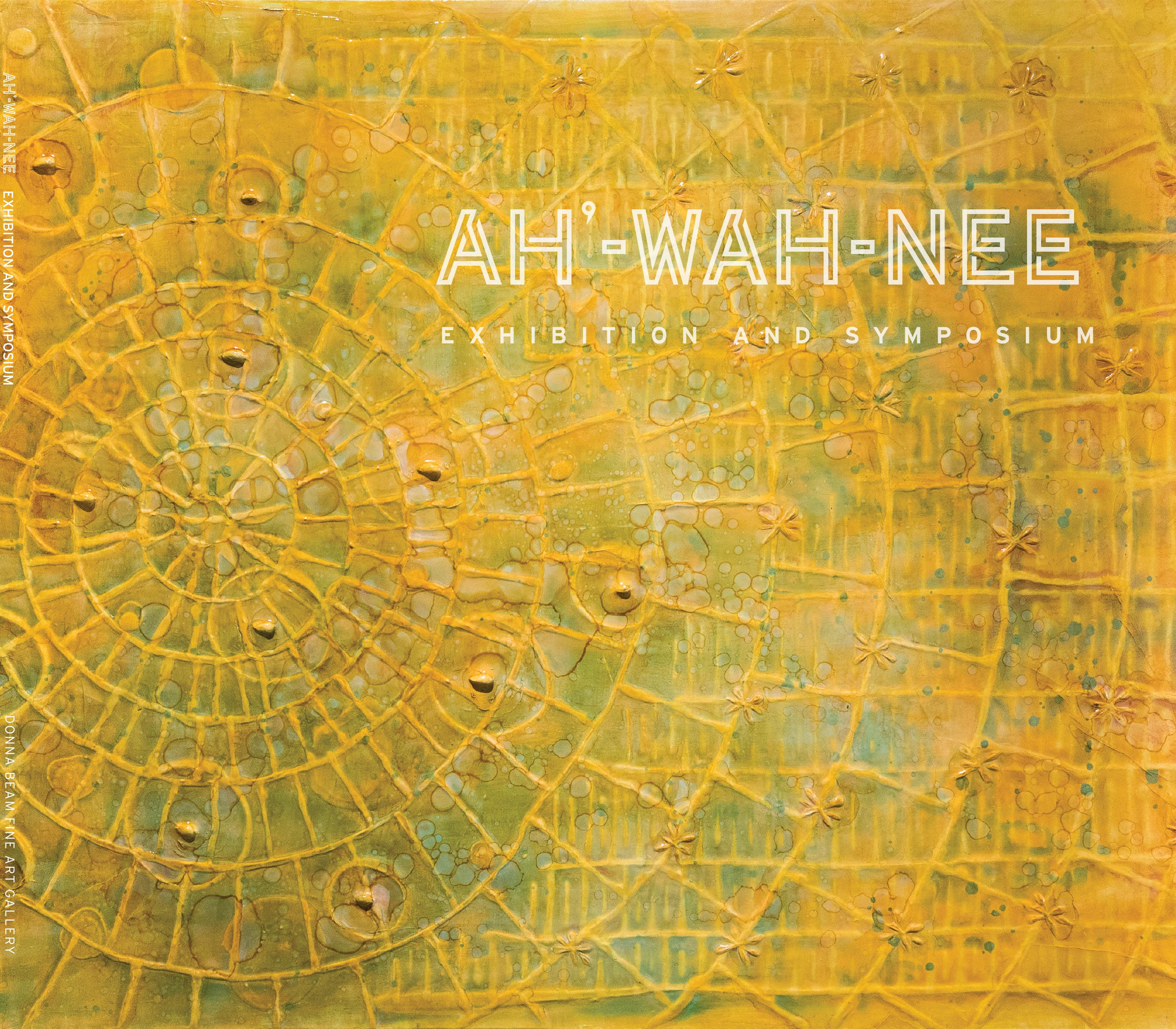

EXHIBITION AND SYMPOSIUM

CURATED BY FAWN DOUGLAS

November 1, 2021 December 10, 2021

Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery University of Nevada, Las Vegas Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute) Lands

1

AH’-WAH-NEE Curated by Fawn Douglas

Published by University of Nevada, Las Vegas Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery

Printed in an edition of 300 Integrated Graphics Services University of Nevada Las Vegas Design: Chloe J. Bernardo

All objects loaned courtesy of the artists unless otherwise indicated.

Copyright © 2022 University of Nevada Las Vegas. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any manner without the prior written permission of the copyright owner except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery

Alta Ham Fine Arts Building

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, Box 455002 Las Vegas, NV 89154-5002 Tel. 702-895-3893 www.unlv.edu/donnabeamgallery

2

FOREWORD

The Donna Beam Gallery is honored to host AH’-WAH-NEE, a truly momentous exhibition in the history of the gallery. AH’-WAH-NEE is the realization of a proposal that Fawn Douglas brought to the gallery nearly two years ago. Her goal was to recognize the work of Indigenous women artists who strive to re-imagine, revitalize, and reclaim the Indigenous Narrative. The importance of such an endeavor could not be overstated, and the decision was to move forward with it.

As it progressed, the exhibition developed into more than just an exhibition. The overarching goal was to share the art, the stories, the challenges, the successes and all that are balanced in the lives of Indigenous women artists. As the project developed, it was evident that AH’-WAH-NEE would have a much greater impact if there were additional offerings to accompany it: an artist’s lecture, a symposium, a dance performance. As is usually the case with any worthwhile undertaking, there was an extreme amount of work involved in curating, organizing and managing all the parts. In the end, the exhibition achieved its goal by bringing together a group of established Indigenous women artists paired with newly minted artists interspersed with mid-career artists all of whom helped define the exhibition theme, ah’-wah-nee, a Southern Paiute word for “balance.”

We wish to acknowledge that we are situated on the traditional homelands of the Nuwuvi, Southern Paiute People. We offer gratitude for the land itself, for those who have stewarded it for generations, and for the opportunity to study, learn, and be in community with this land.

On behalf of the gallery, I want to express my sincere appreciation to all who made this exhibition so significant. To the artists, Loretta Burden, Noelle Garcia, Jean LaMarr, Melissa Melero-Moose, Natani Notah, Cara Romero, Rose B. Simpson, Roxanne Swentzell, and Shelby Westika, thank you for sharing your messages, your stories, and your unique talents! Thank you to Dr. Erika Abad whose perceptive essay further defines and strengthens the impact of this exhibition. Thank you to Wendy Kveck whose behind the scenes work was vital in keeping all on track. To Dean Nancy Uscher and the College of Fine Arts, thank you for your generous contribution that got the ball rolling. Thank you to the individuals and organizations who caught the vision of AH’-WAH-NEE and offered your financial and in-kind support to make it a reality. This would not have been the success it was without you! And a profound thank you to Fawn Douglas whose tireless enthusiasm, energy, and tenacity served to connect all the parts making for a magnificent whole!

Jerry Schefcik UNLV Director of Galleries

3

CURATOR’S STATEMENT

The AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition and Symposium is a love letter to the Indigenous people of the past, present, and future. It expresses a love for the people and our lands that have shaped the flow of my existence and resistance, moving in and out of time like flowing water. AH’-WAH-NEE is a love letter to our Native students, faculty, and broader community through a special recognition of the sacred love for Indigenous women. It is a love around which I’ve witnessed my Aunt Suzan build her legacy, standing for Native American rights through action and policy advancing arts and education. What a love to witness, a love that sustains and impacts future generations.

I wish I knew the word for love in my language. These past several years, I have continued my journey of reclaiming ancestral stories, traditions, and language—language that has been removed from Indigenous people through genocidal assimilation practices of the United States.

It took me months to learn how to introduce myself in Nuwuvi:

Ha Gawda Wiyuk!? Nuni Neyan Fawn Douglas, Nik Nuwuvi!

How are you? My name is Fawn Douglas, I am Southern Paiute!

Those few words still feel like an accomplishment to say, given the history of what is now the United States of America. These words become a reconciliation with the past. I speak in my Nuwuvi language so my ancestors will hear me when in our homelands. My body and spirit are connected to this land, the Southern Nevada desert. My ancestors have been here since time immemorial, nik Nuwuvi! It is my Mother’s Tribe and my own. Above all, it is the Tribe that claims me. I rematriate the land every day with my existence in Western institutional spaces; I live in a state of constant cultural reclamation. My artistic practice makes the statement: This is Nuwuvi Land. In fact, The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, rests on the unceded territories of the Southern Paiute people, my people.

As a Master of Fine Arts Art student at UNLV, my research is connected to the University’s Special Collections and Archives, which archives artifacts and physical documents of my Nuwuvi heritage. I have carefully handled brittle pages that contain the Southern Paiute language. Here, I have found treasured whispers from my people. I do not always know what I am looking for in the archives, but while turning loose leaves of paper, I have sought direction for my life and art practice. How do I walk in two worlds? While researching the papers in the Fall of 2020, my eyes came to rest on a single

4

word: AH’-WAH-NEE. I breathed the word like a release, AH’-WAH-NEE — Balance. Balancing identity is at the heart of the AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition and Symposium, a celebration of the complexities and layers of Indigeneity.

I am not only of my Mother’s lands. I was born in Claremore, Oklahoma, to my Father, who comes from mixed ancestry. His blood flows through me, Southern Cheyenne, Pawnee, Muskogee Creek, and Scottish. Many artists in the AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition and Symposium also come from this mixed ancestry, which influences all of our work as we claim identity, reclaim space, dismantle stereotypes, and remix historical context through the visual arts. How can I accept who I am, all parts of me, and not deny the part of me that stems from the colonizer? How can I see myself in an institution that for decades celebrated an Indian-killer “Frontiersman” as a mascot? Every day, I work to decolonize and dismantle racism, to create the world that I want to be in and that I want for my daughter. It is important that I uplift my people whenever we have a moment of visibility in a place of erasure.

It is imperative that Indigenous students see themselves in the art of AH’-WAH-NEE. According to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) Student Statistics Report of 2021, less than 1% of the student body identifies as Native American or Alaska Native. The faculty demographic of Indigenous people at UNLV is much less. How are we at UNLV providing support for our Indigenous students from nations as near as the Las Vegas Paiute Tribe to the 572 federally recognized tribes that stretch across the United States? Inclusivity, visibility and representation matter.

Providing visibility for Indigenous people through the love of our women, AH’-WAH-NEE is rooted in matriarchal, feminine as well as non-binary energy. I am moved by female artists who challenge me. In 2017 at the Neo Native Arts Exhibition and Symposium, held at Riverside University, California, I was re-introduced to Chemehuevi photographer Cara Romero. She was visible in a way that other Southern Paiute women

in the arts are not. Cara balances the complex and critical lens of herself in the present and future as she walks in two worlds, as Southern Paiute in America. I saw her, and then I saw myself, an Indigenous woman artist speaking of truth and power, hope and resilience, history and the future. Representation opening possibilities. At the time, I could not fully visualize myself as an arts leader without seeing someone else pave the way.

Many leaders in the field of Indigenous arts are women who cross generations — sisters and aunties, daughters and mothers, matriarchs and elders. Loretta Burden is an artist from the Fallon Paiute. I have known Loretta since I was a child. Loretta is an amazing weaver who primarily uses traditional willows and also incorporates other materials into her woven works. She is a personal mentor who has taught me weaving practices and has combined traditional styles with contemporary materials. It is an honor to share my work next to hers in the exhibition.

As an artivist, I look up to artist-activist Jean LaMarr who presents images that represent ideas of “the West” from a Native perspective. Her work provides insight into places of prayer, existence, and resilience. Jean’s work is at the heart of “Artivism,” which captivates and tells stories of her Pit River Paiute people and their cultural landscape. She has been an activist since the 1960s as an artist and organizer during the American Indian Occupation of Alcatraz. Jean corrected me, saying that she is “not an elder yet.” She is still out there as a mover and shaker in her local community. Elders, a title of honor, are the people she helps assist on her reservation in Susanville, California. Jean LaMarr’s 1992 painting We Danced, We Sang, Until the Matron Came served as inspiration during the Symposium as local Las Vegas Paiute dancers performed dances of resilience, Pow Wow style, for their ancestors that went through the boarding school system. It foregrounded healing and resilience (#STILLHERE). I wanted to extend AH’-WAH-NEE’s reach to a place where some of the most incredible artists of our time call home. During birthdays past in August, it

5

was a gift to spend time with my Aunt Suzan Harjo in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts Market. We listened to stories about Grandpa Freeland and Grandma Sue, and I would learn more about my estranged father, her brother Dennis Douglas. Aunt Suzan opened the doorway for my learning in Indigenous Arts. Suzan Harjo has created a legacy in activism through the arts, education, and government policy. She has advised and collaborated on numerous U.S. federal policies, including the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978, the National Museum of the American Indian Act of 1989, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, and the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990. The Obama administration awarded Aunt Suzan the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014 for her many contributions to “Indian Country” in the United States.

In Santa Fe, I would assist Aunt Suzan driving her to gallery shows, exhibitions, artists talks, and forums where she would panel and I could quietly observe and admire all the amazing art and people around me. One of the most memorable trips we took was driving to Tower Gallery, just outside of Santa Fe where we visited her dear friend, Roxanne Swentzell. I would wander around the gallery while they caught up, listening in on their shared stories and laughs. Indigenous women laughing is such good medicine! Years later, it is truly an honor to present Roxanne Swentzell’s A Question of Balance, a bronze sculpture of a woman standing tall and proud with her hands lowered just beneath her abdomen over traditional Santa Clara Pueblo attire. A single, large piece of pottery rests squarely on the top of her head, perfectly balanced; it will never fall. She is pleased, strong, confident, and vulnerable at the same time. This art emotionally connects me to my dear Aunt and to Roxanne Swentzell’s daughter, Rose B. Simpson.

Rose B. Simpson was leading a “Transformance” project in Nevada around the same time that I was curating AH’-WAH-NEE. She wanted to collaborate with Natives in Nevada through this performative work, which foregrounded the idea of reclamation of space (#LANDBACK). We connected over shared

visions of Indigenous art in a post-apocalyptic time, envisioning our bodies as vessels, balancing the themes of Indigenous feminisms and futurisms. As Indigenous women and mothers we are healing our generation and the next in order to carry us into the future. Getting to know Rose and her daughter through this journey has reminded me of the friendship I saw through my Aunt Suzan and Roxanne Swentzell. Perhaps someday, we will be visiting in our own galleries, sharing stories and laughing so loud that other young women are blessed with that medicine. Our actions transcending time with art that solidifies that we are #STILLHERE.

Artists that are leaders in the movement of Indigenous feminisms gathered at UNLV from November 4–5, 2021, to share art, love, and laughter. Through the AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition and Symposium, I made lifelong connections and was able to share art from an array of Indigenous perspectives with the students and community. Through their art and participation in the panel discussions, the artists spoke of parts of themselves that were touched by conflict and trauma, yet they somehow found a way to establish an equilibrium. The artistic process helps us heal wounds and find balance. These artists are daughters, mothers, artists, students, teachers, fighters, protectors, and much more. This was the first exhibition of Indigenous artists that crossed generations, mixed identities, and honored the feminine and non-binary at UNLV. As women of color, as Indigenous women, we are at the forefront of change and leadership in our communities. We are building a path forward for others to follow. AH’-WAH-NEE is what others seek to find within themselves and for future generations. This gift was an expression of love for you.

Hu’ Iyuk! (It’s good!)

Fawn Douglas, MFA Indigenous American artivist Head matriarch of Nuwu Art + Activism Studios Las Vegas Paiute Tribe Member

6

EXH I BIT ION

Fawn Douglas Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands (detail) 2021

Fawn Douglas Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands (detail) 2021

LORETTA BURDEN

FALLON PAIUTE-SHOSHONE

Loretta Burden (b. 1945) is a basket weaver, teacher and multimedia sculptor. Her basketry was featured in the book Basket Weavers of Tradition and Beauty by Mary Fulkerson and exhibited with a statewide travelling art exhibition in the 1980’s called Common Thread. Burden also worked with the Clark County Museum, Henderson, Nevada, to create one of their first Native American exhibitions and a Native basketry exhibition at the McCarran International Airport (now the Harry Reid International Airport). Burden has been featured as one of six “Nevada Women Making a Difference” for the Las Vegas Centennial Celebration in 2005, and as a community leader making positive changes to the cultural fabric of Las Vegas in the documentary “Women of Diversity.”

8

Fish Trap 2020 Willow and commercial string 15 x 27 inches

9

Seed Beater 2 2021

Willow and commercial string 9.5 x 21 inches

Seed Beater 1 2020 Willow and commercial string 9.5 x 18 inches

Installation image (opposite) 2021

10

FAWN DOUGLAS

LAS VEGAS PAIUTE

Fawn Douglas (b. 1978) is an Indigenous American “artivist” and an enrolled member of the Las Vegas Paiute Tribe. She also has roots in the Moapa Paiute, Southern Cheyenne, Creek and Pawnee Tribes. She is dedicated to the intersections of art, activism, community, education, culture, identity, place and sovereignty. Within her art-making and activism, she tells stories to remember the past and to ensure that the stories of Indigenous peoples are heard in the present. Her studio practice includes painting, weaving, sculpture, performance, activist art and humor. She is currently working on her MFA degree with the Department of Art at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV, 2022).

Douglas is a dedicated advocate for environmental conservation, including the designation of Nevada’s Gold Butte as a historic national monument and her participation in the #NoDAPL protests at the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. As a survivor of sexual assault, Douglas’s experience has given her the fire to speak up about women’s rights, and she has been a vocal advocate for #MMIW (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women). She continues to speak up for her sisters, and she is an active supporter of Our Bodies, Our Lands—the movement that recognizes the connection between protecting land, water and Indigenous people. She is co-founder of Nuwu Art + Activism Studios in downtown Las Vegas.

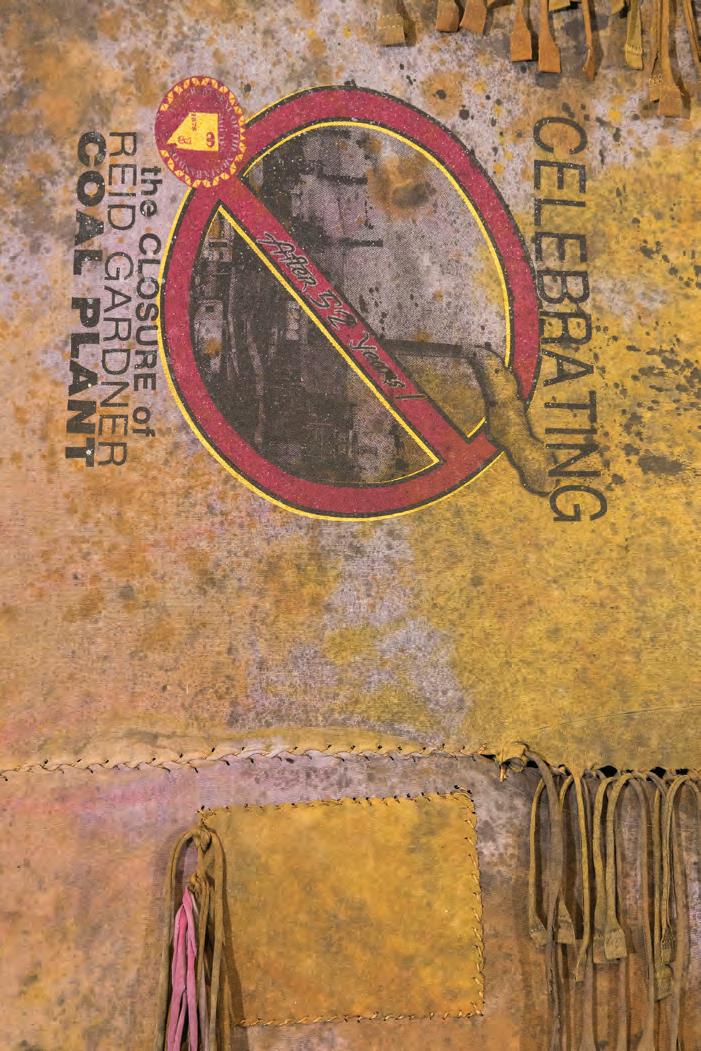

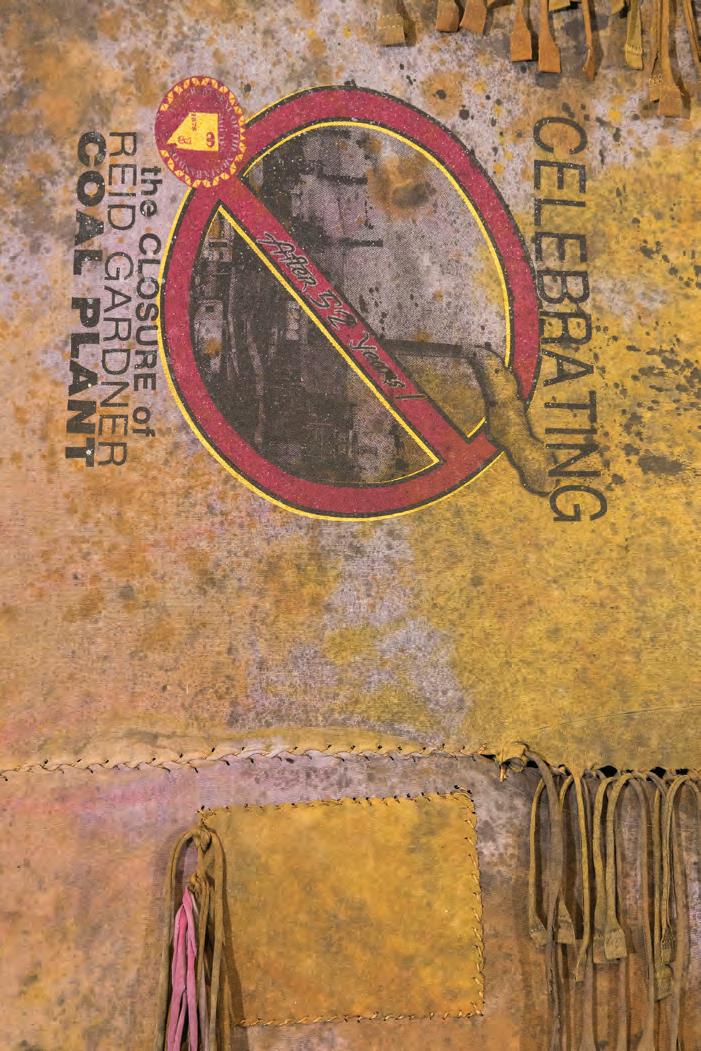

Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands 2021 Mixed media, repurposed T-shirts, acrylic, and sinew 48 x 54 x 2 inches

12

14

Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands (detail) 2021

Mixed media, repurposed T-shirts, acrylic, and sinew 48 x 54 x 2 inches

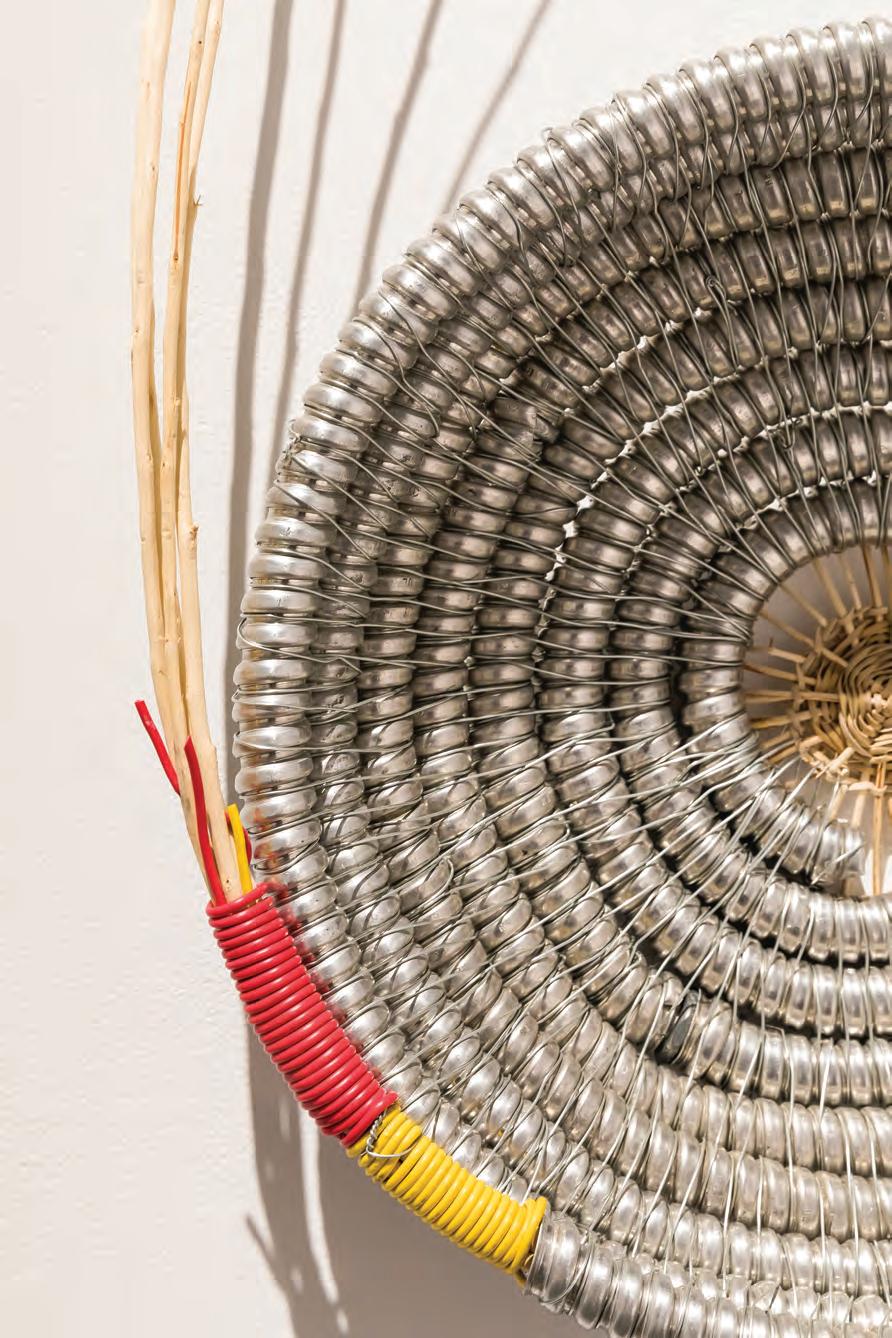

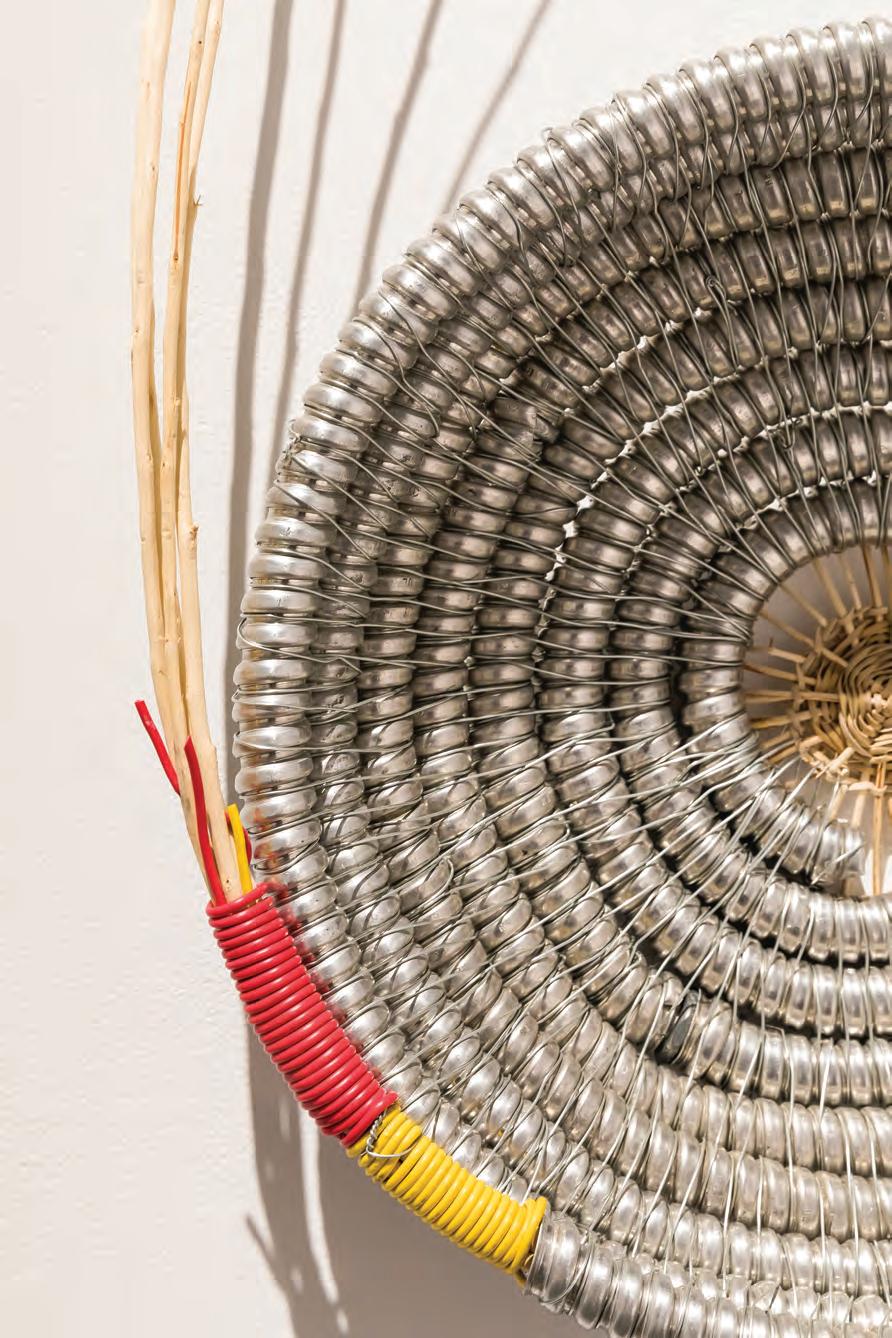

Nuwuvi Basket 2021

Mixed media, wire, metal conduit, and willow 16 x 16 x 5 inches

Nuwuvi Basket (detail) 2021

Mixed media, wire, metal conduit, and willow 16 x 16 x 5 inches

16

Deer Woman Rising 2020 Video Filmed by Krystal Ramirez, music by Sol Martinez Snow Mountain Pow Wow Grounds

17

Deer Woman Rising 2020 Video Filmed by Krystal Ramirez, music by Sol Martinez Snow Mountain Pow Wow Grounds

NOELLE GARCIA

KLAMATH, MODOC, AND PAIUTE

Based in the Chicago area, Noelle Garcia (b. 1984) is an artist and educator who focuses on themes of identity, family history, and recovered narratives in her work. She is an Indigenous artist from the Klamath and Paiute Tribes. She earned her BFA degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and her MFA degree from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Her paintings, drawings, and soft sculptures have been exhibited in galleries and institutions across the United States. Garcia has earned awards and fellowships at various institutions including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, the Nevada Arts Council, the Illinois Arts Council, and the American Indian Graduate Center.

18

19

Revolver (Cowboy Gun) 2019 Mixed media with beads and thread 4.5 x 11 x 1 inches

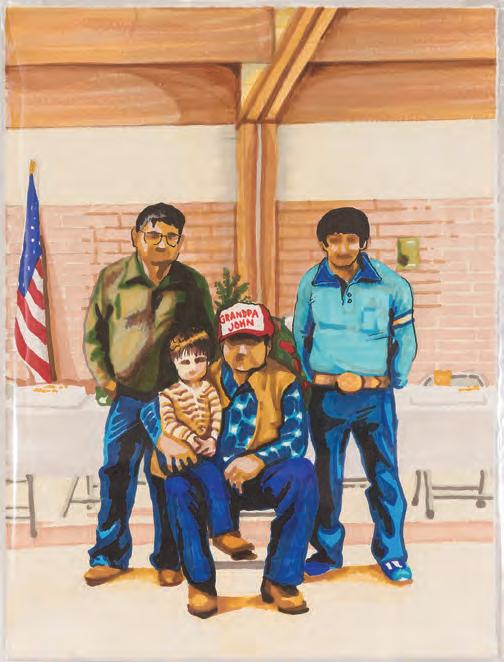

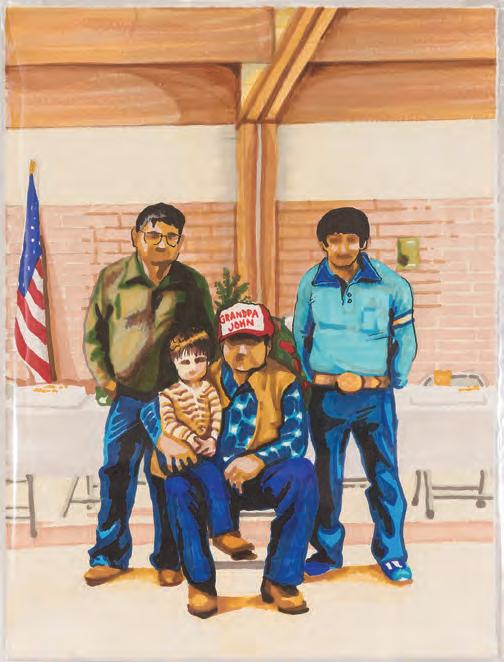

Grandpa’s Birthday 2021 Marker on paper 7.5 x 10 inches

Cradleboard 2006 Lithographic print, ed. 1/4 12 x 16 inches

20

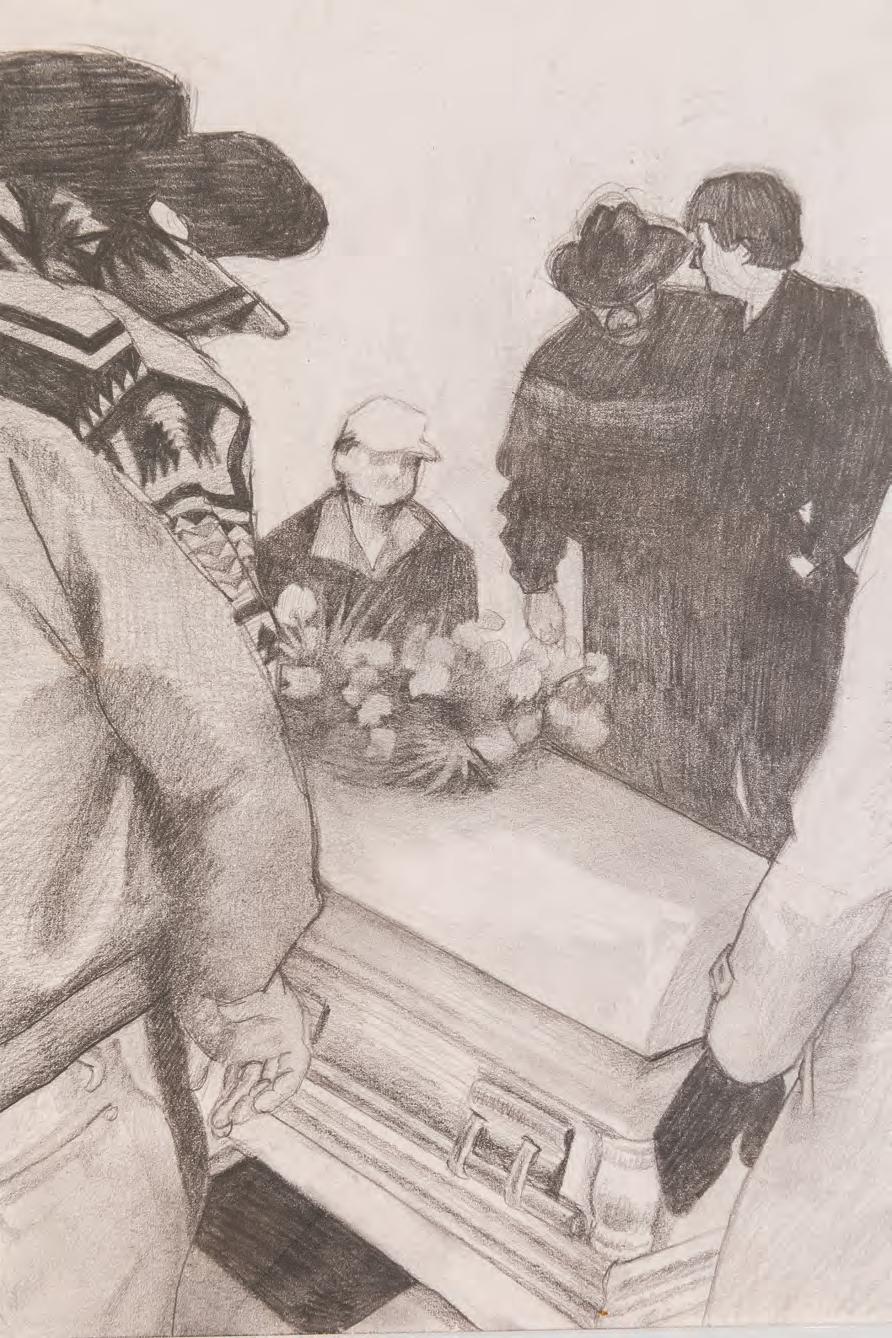

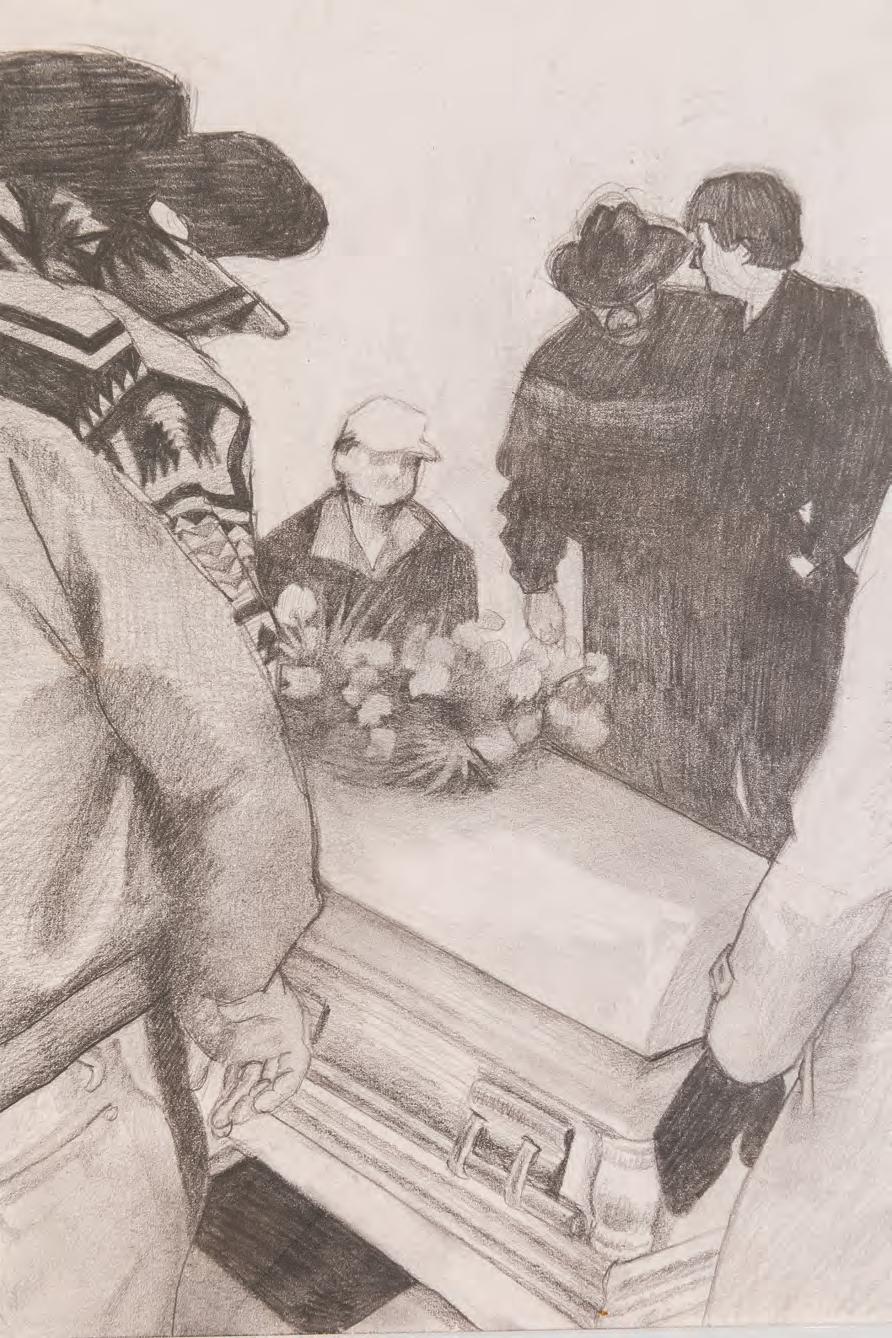

Now I Put You in the Ground 2021 Graphite on Bristol 12 x 9 inches

Rifle (Dad’s Gun) 2021 Mixed media with beads, fabric, cotton, and thread 4 x 30 x 1.75 inches

22

Revolver (Cowboy Gun) 2019 Mixed media with beads and thread 4.5 x 11 x 1 inches

Rifle (Dad’s Gun) 2021 Mixed media with beads, fabric, cotton, and thread 4 x 30 x 1.75 inches

23

JEAN LAMARR

PAIUTE/PIT RIVER

Jean LaMarr (b. 1945) makes art that addresses issues such as cultural stereotypes, representations of women and Native American people, and the traditions of her ancestors. Although she has worked primarily as a printmaker, she is also known for her paintings, assemblages, videos, and installation work. Her exhibitions are many and span the United States and Germany. LaMarr’s work was included in an exhibition touring the US titled Committed to Print, initiated by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She also designs and creates award-winning beadwork.

LaMarr, who was born in Susanville, CA, is of Paiute/Pit River ancestry with family ties to Northern Nevada and northern California. Her artistic development was critically influenced by the time she spent at UC Berkeley from 1973–1976, where she earned her BFA degree and where she was involved with activist politics. LaMarr describes herself as a community artist-activist. She lives on the Susanville Indian Rancheria in northeastern California, where she continues to operate the Native American Graphic Workshop. A retrospective of her work, The Art of Jean LaMarr, is currently on view at the Nevada Museum of Art.

24

25

Sacred Places Where We Pray c. 1964 Mixed media on canvas 30 x 45 inches

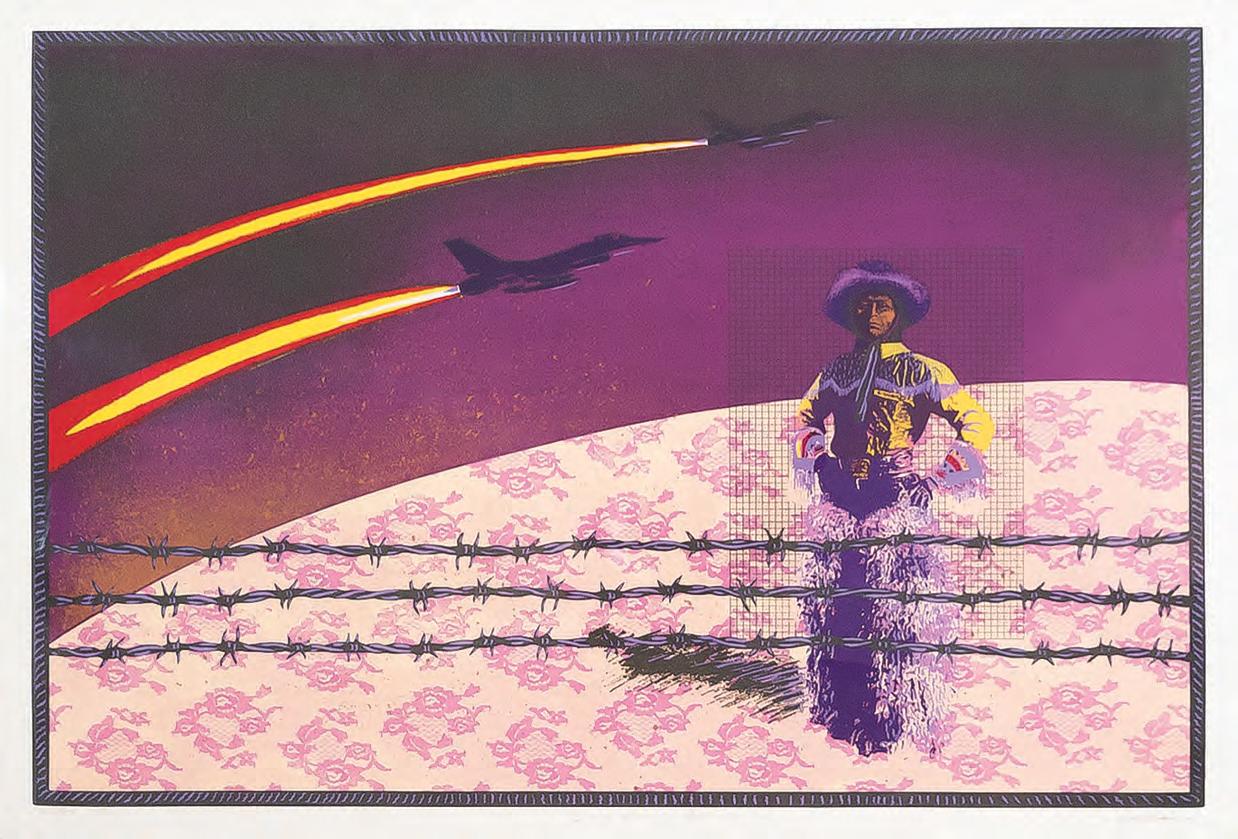

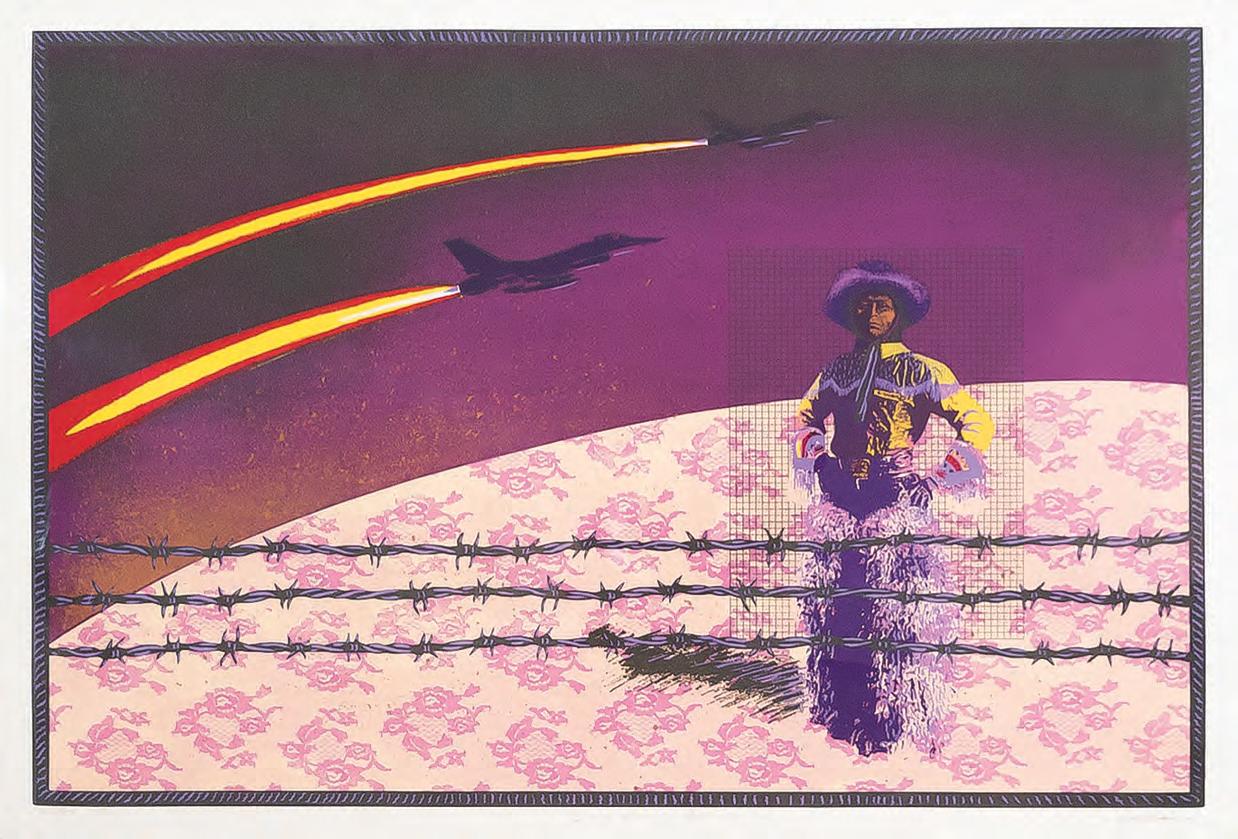

Some Kind of Buckaroo 1990 Screenprint, ed. 26/58 26 x 38 inches

26

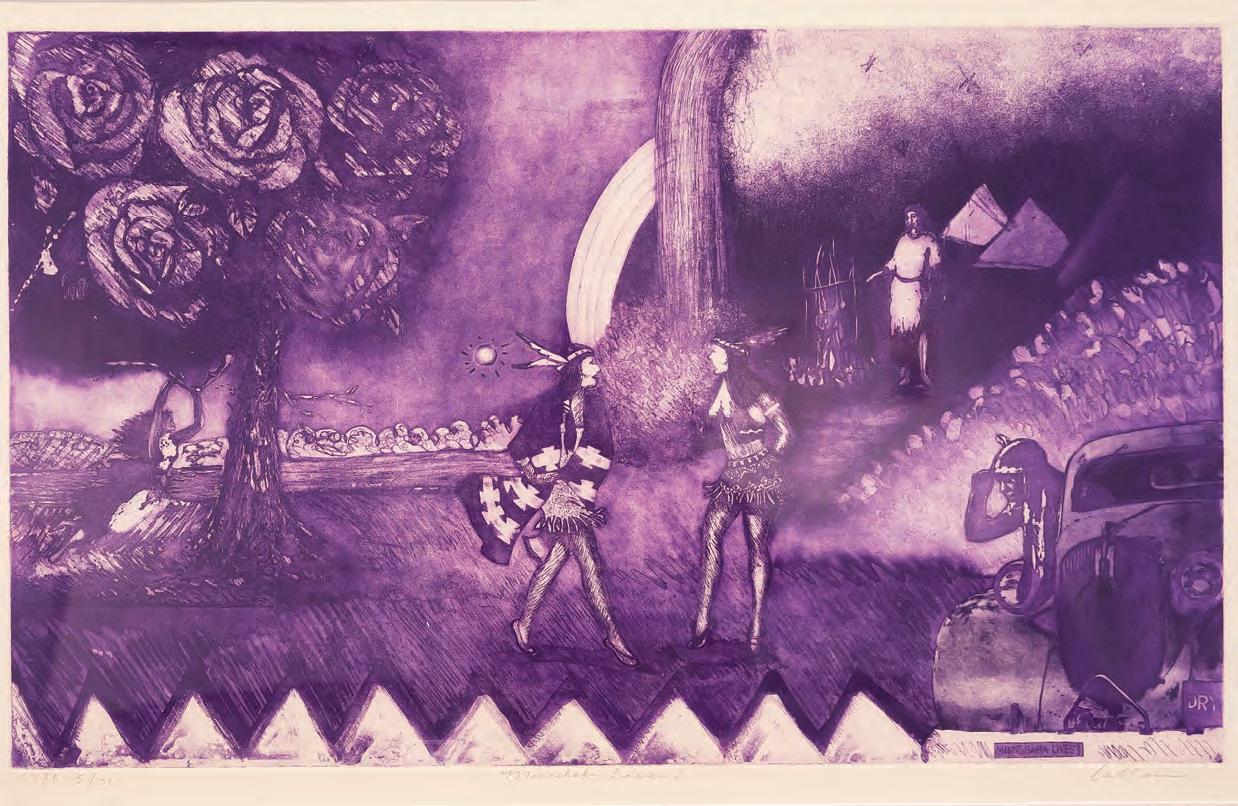

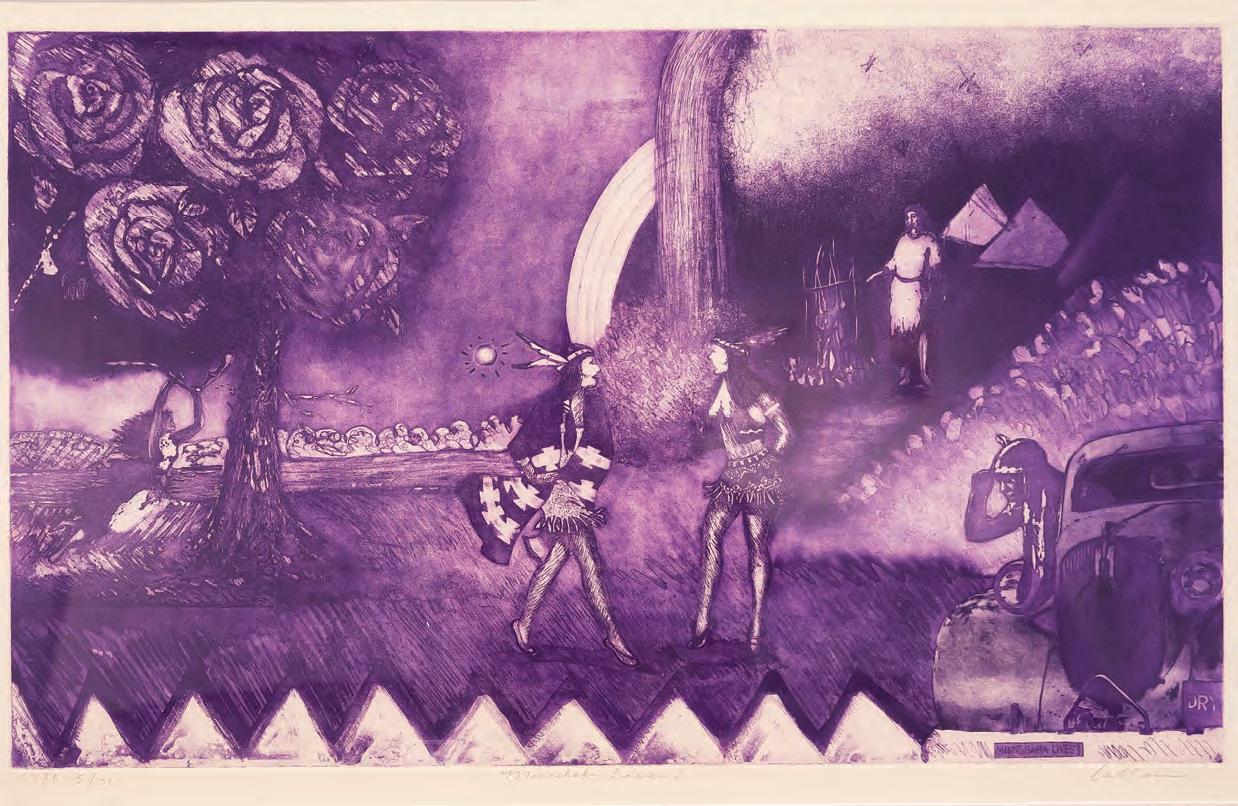

Minnehaha Lives! 1983 Color etching, ed. 5/30 24 x 36 inches

27

MELISSA MELERO-MOOSE

FALLON PAIUTE-SHOSHONE

Melissa Melero-Moose (b. 1974) spent most of her childhood living in Reno, NV. She is a Northern Paiute enrolled with the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe with ties to Fort Bidwell Paiute, CA. Melissa holds a BFA degree from the Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, NM and a BS in Psychology and Fine Arts from Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Melero-Moose’s works are a part of the permanent collections of the School for Advanced Research (IARC), Santa Fe, NM, Autry Museum in Los Angeles, CA, IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, NM, the Nevada State Museum in Carson City, NV, and the Lilley Museum at the University of Nevada, Reno. She is currently exhibiting regionally and nationally as an individual artist and with the Great Basin Native Artists (GBNA) art collective. Influences on her imagery are found in the Great Basin landscape, petroglyphs, beadwork, and basketry from the Indigenous tribes of Nevada and California.

Melero-Moose currently lives with her family in Hungry Valley, NV, where she works as a professional artist, a contributing writer for First American Art Magazine, and as founder/ independent curator of the Great Basin Native Artists.

28

29

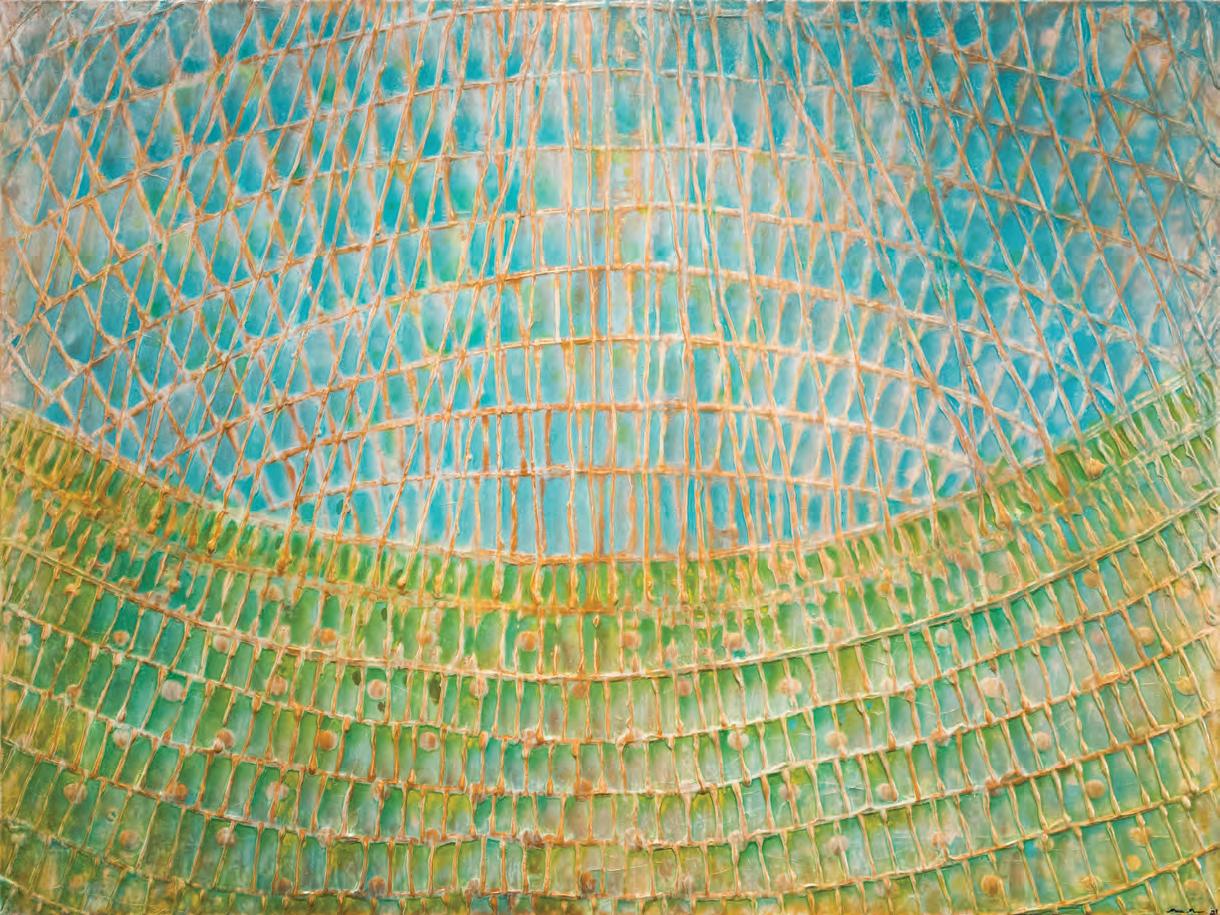

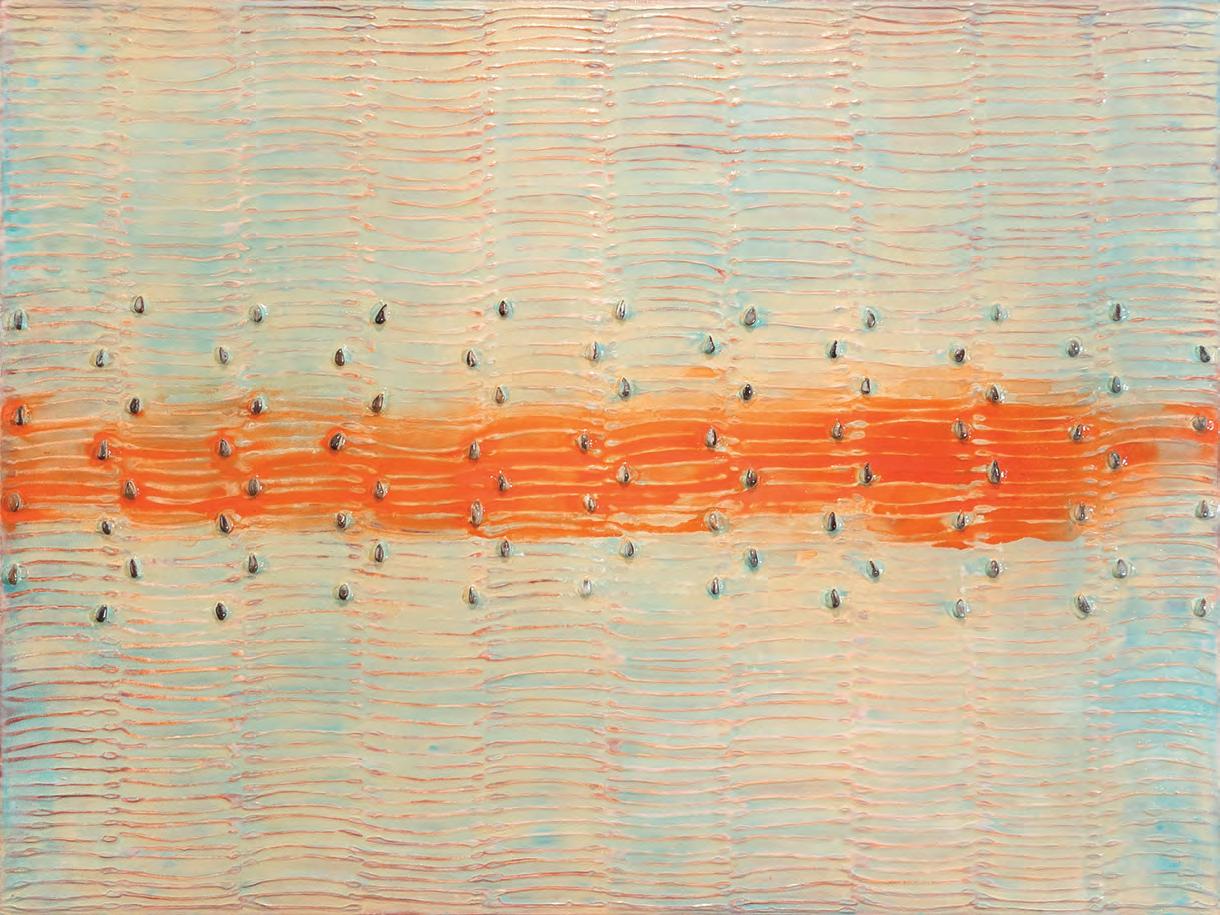

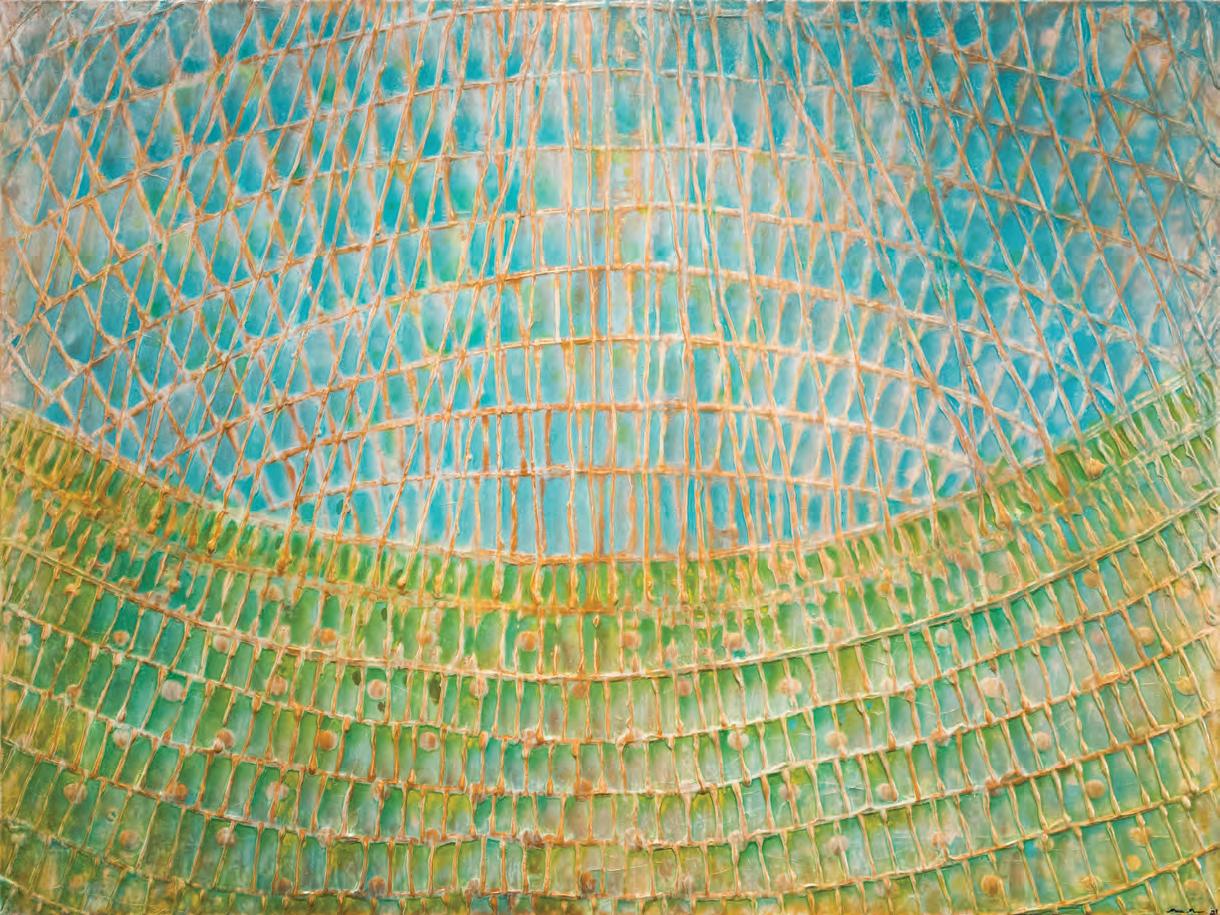

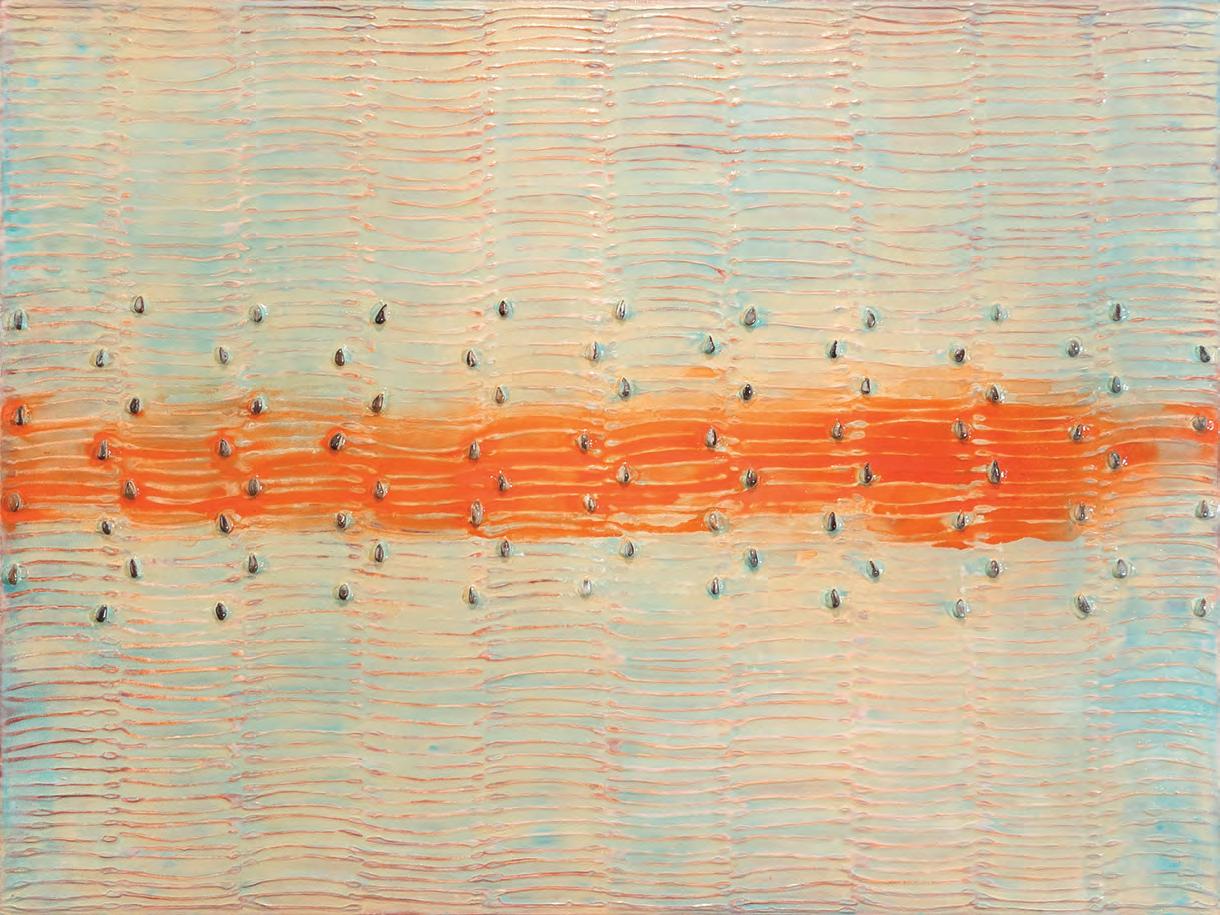

Access Denied 2020 Mixed media with pine nuts on canvas 36 x 48 x 2 inches

30

Making a Burden Basket 2021 Mixed media with on canvas 36 x 48 x 2 inches

Rearranging 2021 Mixed media with pine nuts on canvas 30 x 40 x 2 inches

31

NATANI NOTAH

DINÉ NAVAJO

Natani Notah (b. 1992) is an interdisciplinary artist and a proud member of the Navajo Nation. Her current art practice explores contemporary Native American identity through the lens of Diné womanhood. Notah has exhibited her work at institutions, such as apexart, New York City; NXTHVN, New Haven; Tucson Desert Art Museum, Tucson; Gas Gallery, Los Angeles; The Holland Project, Reno; Mana Contemporary, Chicago; Axis Gallery, Sacramento; SOMArts Cultural Center, San Francisco, and elsewhere. Notah has received awards from Art Matters, International Sculpture Center, and the San Francisco Foundation. Her work has been featured in Art in America, Hyperallergic, Forbes, and Sculpture Magazine and she has completed artist residencies at the Vermont Studio Center, Grounds for Sculpture, Headlands Center for the Arts, This Will Take Time, Oakland, and Kala Art Institute. Notah holds a BFA with a minor in Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from Cornell University and an MFA from Stanford University. Currently she is a 2021-2023 Tulsa Artist Fellow.

32

Lady in Beads 2021 Vintage cotton t-shirt, faux fur pom pom, silk scarf. silver bells, seed beads, artificial sinew, thread, and plastic corn pellets 10 x 10 x 12 inches

33

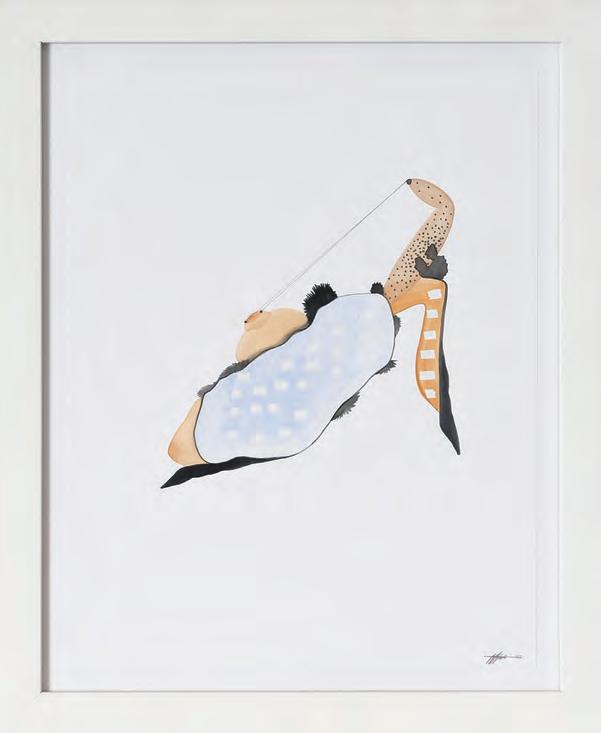

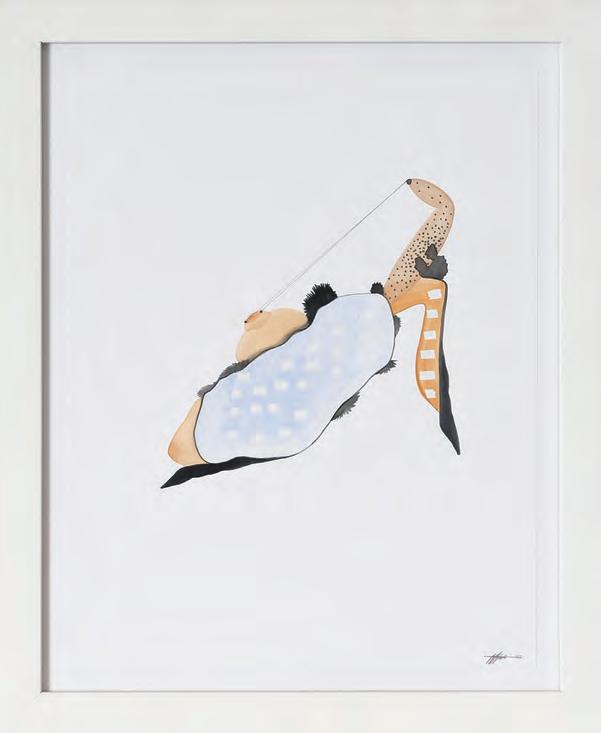

Come in the Water is Nice 2021 Watercolor, graphite, and white out strips on archival paper 11 x 14 inches

Call Her at Sunset 2021 Watercolor, graphite, and white out strips on archival paper 11 x 14 inches

34

CARA ROMERO

CHEMEHUEVI

Cara Romero (b. 1977) is a contemporary fine art photographer. An enrolled citizen of the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe, Romero was raised between contrasting settings: the rural Chemehuevi reservation in Mojave Desert, CA and the urban sprawl of Houston, TX. Romero’s identity informs her photography, which is a blend of fine art and editorial photography shaped by years of study and a visceral approach to representing Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural memory, a collective history, and lived experiences from a Native American female perspective.

As an undergraduate at the University of Houston, Romero pursued a degree in cultural anthropology. Disillusioned, however, by academic and media portrayals of Native Americans as bygone, Romero realized that making photographs could do more than anthropology could with writing words, a realization that led to a shift in medium.

Since 1998, Romero’s expansive oeuvre has been informed by formal training in film, digital, fine art and commercial photography. Romero takes on the role of storyteller by staging theatrical compositions infused with dramatic color, using contemporary photography techniques to depict the modernity of Native peoples, and illuminating Indigenous worldviews and aspects of supernaturalism in everyday life.

Romero regularly participates in Native American art fairs and panel discussions, and she was featured in PBS’ Craft in America (2019). She maintains a studio in Santa Fe, NM, and her award-winning work is included in many public and private collections internationally. Married with three children, she travels between Santa Fe and the Chemehuevi Valley Indian Reservation, where she keeps close ties to her tribal community and ancestral homelands.

36

37

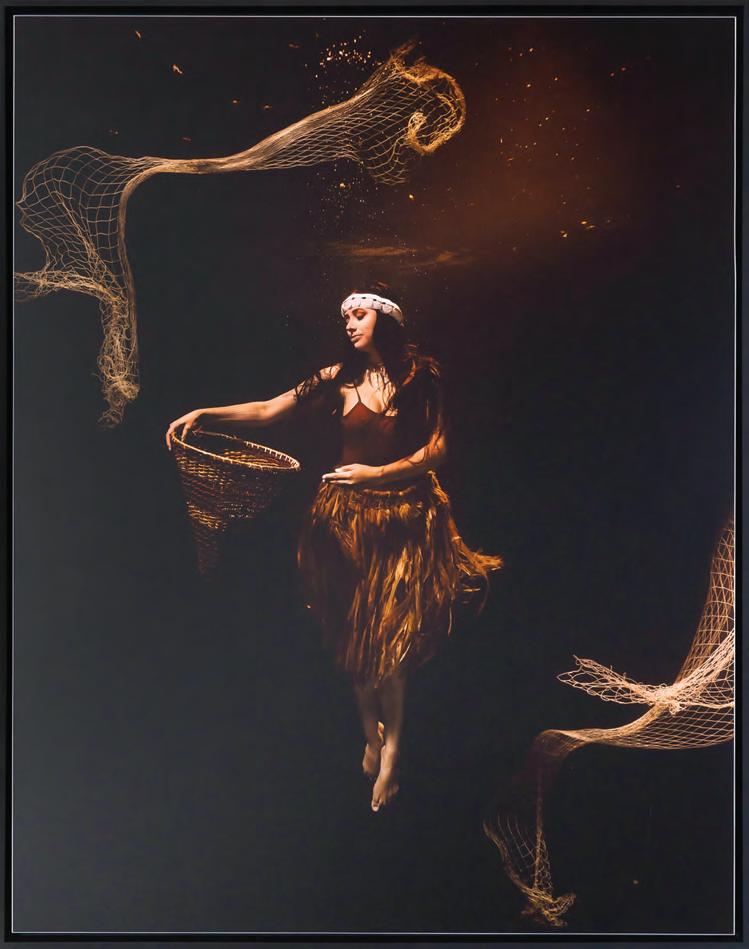

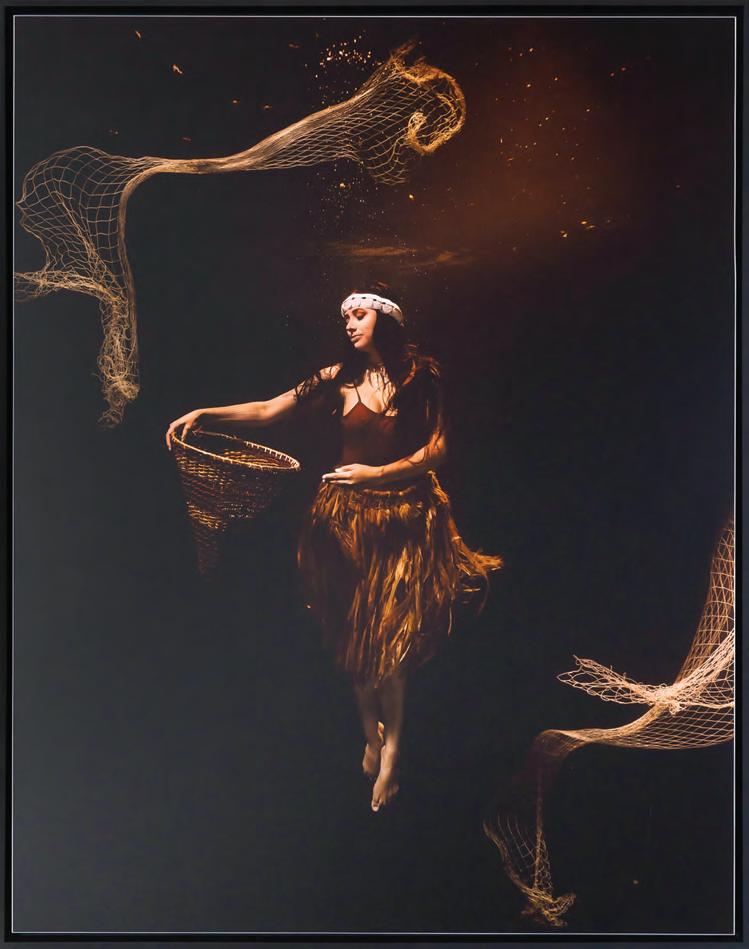

WESHOYOT

2021 Archival pigment print 51 x 40 inches Edition of 3

38

GAEA 2021 Archival pigment print 51 x 40 inches Edition of 7

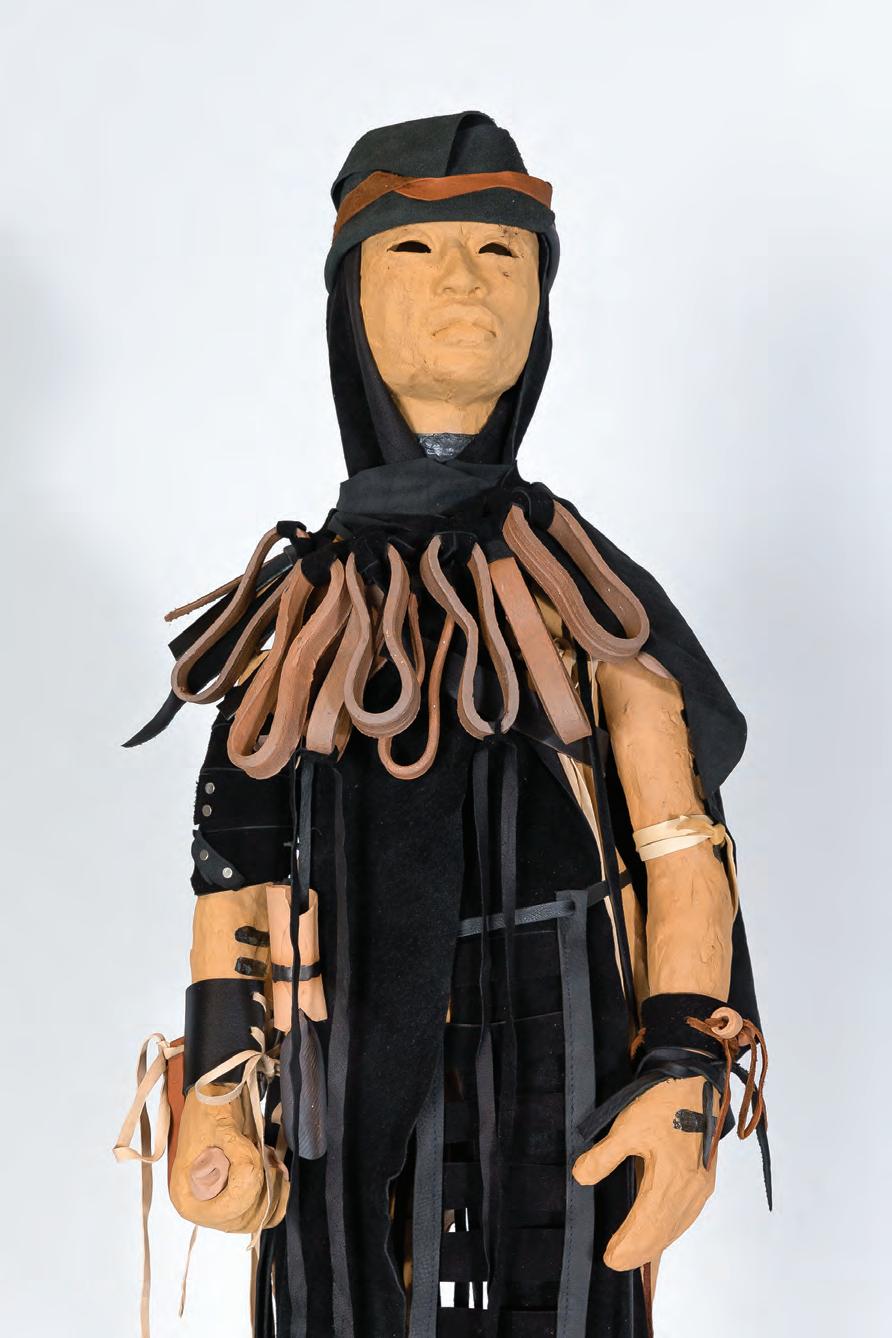

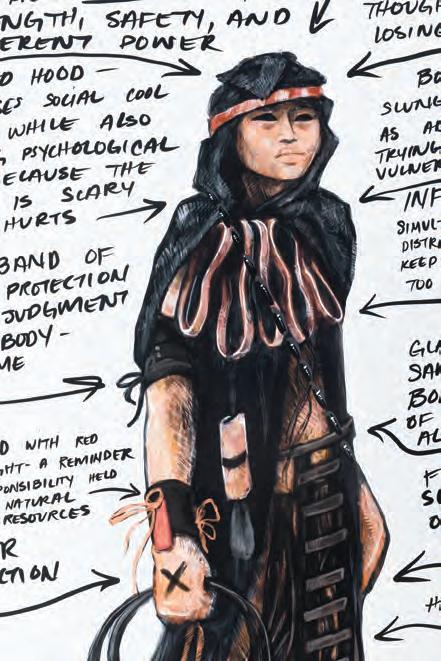

ROSE B. SIMPSON

SANTA CLARA PUEBLO

Rose B. Simpson (b. 1983) is a mixed-media artist from Santa Clara Pueblo, NM. Her work engages ceramic sculpture, metals, fashion, performance, music, installation, writing, and custom cars. She received an MFA in Ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2011, and an MFA in Creative Non-Fiction from the Institute of American Indian Arts in 2018. Her artwork is shown and collected by museums from across the continent including SITE Santa Fe; the Heard Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Native Art, Santa Fe; the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian; the Denver Art Museum; Pomona College Museum of Art; Ford Foundation Gallery; The Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian; the Minneapolis Institute of Art; the

Savannah College of Art and Design; and the Nevada Museum of Art as well as having her work shown internationally.

Simpson lives and works from her home at Santa Clara Pueblo, and she hopes to teach her young daughter how to creatively engage the world. In November, 2021, Simpson collaborated with members of the local Las Vegas, Indigenous community to co-create an experience informed by their collective lifetimes of a post-apocalyptic reality. Her Las Vegas Transformance was presented by the Nevada Museum of Art with support from Art Nuwu Art + Activism Studios in Las Vegas, NV and artist Fawn Douglas.

40

Innate 2021 Ceramic and mixed media 36 x 12 x 8 inches

41

Courtesy of Silverman Gallery, Santa Fe

42

ROXANNE SWENTZELL

SANTA CLARA PUEBLO

Roxanne Swentzell (b. 1962). Her mother, Rina Swentzell, was a Native American from Santa Clara Pueblo in Northern NM, who was a potter and architect. Her father, Ralph Swentzell, was a professor at St. Johns College for 45 years. Roxanne was exposed to the richness of Native American culture which included pottery, adobe building, farming, and community traditions of the Pueblo peoples. On her father’s side, she was exposed to the wealth of Western philosophy and great works of European art. Roxanne struggled with a speech impediment but at the age of four she started using her mother’s clay to create small figurines to communicate. The figures showed emotions and simple scenes that were part of Roxanne’s world. This became her first language. By high school, she was invited to attend college level art classes at the Institute of American Indian Arts. After graduating, Swentzell went on to the Portland Museum Art School in Oregon, but her cultural roots brought her back to Santa Clara to build her home in the pueblo and raise her two children.

Sculpture became the medium that would support Swentzell and her family. In 2004, she opened the Tower Gallery,

in Pojoaque, NM. The gallery primarily featured Swentzell’s work but has also included work by other Native and nonnative artists. She has always used her art to address topics of gender, culture, and environmental issues. A few of the many awards from her 40-year career include: 1st place in Sculpture at the Santa Fe Indian Market (1998), the Native Treasures Award (MIAC 2011), and the Spirit of the Heard Award (2016, AZ). Her work is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian (DC), the Heard Museum (AZ), the Denver Art Museum (CO), the Museum of Wellington (New Zealand), and the British Museum of Art (England). She has exhibited in Paris, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Denver, Washington DC, and Santa Fe.

Swentzell cares deeply about environmental issues and cultural preservation. In 1987, she helped co-found the non-profit Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute. Swentzell continues to create sculptures and to work on community projects, all with the intention of addressing issues of today and creating a better world for generations to come.

44

A Question of Balance 2021 Bronze, ed. 25 23 x 4 x 5 inches

45

46

SH EL BY W ES TIK A

ZUNI PUEB LO

Shelby Westika (b. 1992) is a contemporary Zuni artist whose work links the mediums of painting, drawing, and sculpture.

By utilizing an ever-growing archive of historical documents and photographs, they create artwork that evokes the viewer’s emotions through abstraction and color. Each piece of source material is dissected to the point where meaning shifts, and the interpretation of it becomes multifaceted. Westika imagines their translation by examining ambiguity and original reference through evolving adaptations and studio experiments. They reflect on the closely related subjects of archive, memory, and imagination. Westika graduated from Santa Fe University of Art and Design with a BFA, and they earned an MFA from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in 2021.

48

Dream 2020 Ceramic and acrylic on panel 24 x 49 x 3.5 inches

49

Dream (detail) 2020 Ceramic and acrylic on panel 24 x 49 x 3.5 inches

50

Eye of the Storm 2021 Digital painting 20 x 30 inches

51

AH’-WAH-NEE installation (left to right): Melissa Melero-Moose. Making a Burden Basket, 2021. Rearranging, 2021. Jean LaMarr. Sacred Places Where We Pray, c. 1964.

AH’-WAH-NEE installation (left to right): Melissa Melero-Moose. Making a Burden Basket, 2021. Rearranging, 2021. Jean LaMarr. Sacred Places Where We Pray, c. 1964.

BALANCING STORY, MEMORY, AND PANDEMICS—INDIGENOUS ARTISTS REMEMBERING VULNERABILITY, RESILIENCE, AND TRADITIONS

For the AH’-WAH-NEE exhibition and symposium, Fawn Douglas brought together 26 pieces from 9 artists who have inspired her over the years. The AH’-WAH-NEE exhibition extends the conversation that recent Native womencentered art shows like Hearts of Our People, Native Feminisms, and NeoNative started. Douglas spearheaded this endeavor, the first of its kind on campus, initiating dialogue with institutional leaders and funders to support her vision. Douglas localizes the conversation, specifically focusing on contemporary Indigenous women artists from colonies, bands, nations, and tribes in what is now called the Southwestern United States. As artist and curator, Douglas positions her Indigenous fusion artistic identity in conversation with established and up-and-coming Indigenous artists balancing tradition, adaptability, story, and healing. As she discussed in the introduction of the symposium, reviewing UNLV’s Special Collections’ documents brought her across the term “AH’-WAH-NEE,” which is Paiute for “balance,” as the central theme that spoke to the vision she had for the first documented Indigenous centered show on UNLV’s campus. AH’-WAH-NEE begs the question, what does it mean for a rising artist-activist-scholar to dedicate time and energy to create a balanced conversation with contemporary artists of her time?

The first essays in Hearts of Our People frame Douglas’s ethical and political considerations in bringing this exhibition together. Douglas’s media brings her home to the forefront by inserting her work within the show. Her Nuwuwi Basket functions as a critical case study of how, “women have continued to hand down [the fusion of artistic practice, Indigenous traditions, and visual/ material storytelling] through generations despite the impositions and oppressions that have occurred throughout history.”1 Loretta Burden’s baskets, Fish Trap (2020) and Seed Beater (2021), similarly fuse traditional practices

1 Silver, Ahlberg Yohe, Greeves, Feldman, Silver, Laura, Greeves, Teri, Feldman, Kaywin, Minneapolis Institute of Art, issuing body, publisher, organizer, host institution, & Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community of Minnesota. (2019). Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists. Minneapolis Institute of Art in association with the University of Washington Press.

53

with contemporary materials to extend the conversation of Indigenous artists who blend their foundation of ancestral traditions with current materials.

As a participant on the symposium’s first panel at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, Burden tells the audience, “I never knew I was an artist.”2 After moving to Fallon to bring her great-niece closer to her family, she then took basket weaving classes to learn about the tradition. Her reasons for pursuing basket weaving complement how family, responsibility, and story ground many of the other artists’ motivations. Burden explains that she, “started adding color to my baskets because of Mother Earth and because I could see all these colors and I thought, well I’m traditional and contemporary and so people would look at my work and say ‘Well, that’s not traditional.’”3

An elder in the community whose artistic practice is relatively more recent than other, more established, and formally trained artists in AH’-WAH-NEE, Burden’s testament speaks to the institutional struggles many of the artists experience while navigating art school. They contend with how their respect for Indigenous traditions contrasted or challenged Western ideas of what constituted “art.”

Douglas’s approach to basket weaving in Nuwuvi Basket (2021) brings metal conduit in conversation with willow, much like Burden’s fusion of willow and commercial string within her baskets. These artists speak to the longstanding tradition of Indigenous women’s adaptability to resources to retain traditional practices. For example, Douglas built the basket with materials she found on the grounds of the Nuwu Art + Activism Studios she started concurrently developing during this exhibition. Douglas’s use of found materials is a means to enact respectful and sustainable stewardship of the land.

Their basket-making practices also challenge the monolithic extension of traditions that often legally mediate how the federal and state policies impede upon Indigenous people’s sovereignty and access to the wealth of their own land, creating urgency to tell their stories. Their conditional access, whether to memory or natural resources, or the land itself, pushes the conversation and concern with balance.

Many of the sculptures, prints, and performances speak to homelands, some explicitly focusing on environmental protection. At the beginning of the AH’-WAH-NEE Symposium, Las Vegas Paiute Council Member Alfreda Mitre shared that, “the desert was created by the Creator so he could have a place to dream.”4 So Douglas’s Nuwuvi: Our Bodies Our Land (2021), made from repurposed t-shirts from environmental protests, speaks, via the blank spaces in the piece, to where the Creator still dreams, despite how we (humans) have treated the desert. Douglas’s work artistically represents the ongoing efforts to repair and reclaim a connection to the land.

The plum-dyed fringe in Nuwuvi: Our Bodies Our Land echoes the aesthetic of the Valley of Fire and the desert’s golden hour, in commune with Jean LaMarr’s extensive use of purple across her prints and mixed media pieces, Some Kind of Buckaroo (1990), Minnehaha Lives (1983), and Sacred Places Where We Pray (1964). In “The Art of Jean LaMarr,” Ann M. Wolfe writes, “The color purple…has become an integral part of [LaMarr’s] identity. When she speaks of the color purple, it conjures memories of the lilacs, lupine, and long mountain shadows of her homeland, Susanville, CA.”5 Artists’ dialogue with their ancestral homelands also reflects what it means to have lost access to those lands and the traditional foods and medicines they relied on before Western colonialism and imperialism.

2 AH’-WAH-NEE symposium, the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. November 5, 2021.

3 Ibid.

4 Wolfe, Anne and Jean LaMarr. (2021) Jean LaMarr. The Art of Jean LaMarr. Nevada Museum of Art. p. 9

5 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (December, 2021) Melissa Melero-Moose.

54

Melissa Melero-Moose’s mixed media paintings, Access Denied (2020) and Making a Burden Basket (2021), speak to the influence of limited access to natural resources. Melero-Moose is a member of the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, and she resides on the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony near Sparks, Nevada. Melero-Moose founded the Great Basin Native Artists Collective. Like Douglas and Burden, Melero-Moose abstracts place, identity, and memory in her work. In an email, Melero-Moose explained that her mixed media work Access Denied “is about limited representation at positions of power and the visibility of Indigenous artists, and the imagery is about the barb wire that separates a lot of Native peoples from access to the willow, pine nuts, and water on our homelands in Nevada, which is the essence to our traditions and survival.” Her pieces Rearranging and Making a Burden Basket are, “both an interpretation and abstraction of the basket texture and culture, pine nuts, colors of the Great Basin and mixing that visual into a new memory and respect for place.”6 In conversation with Douglas’s and Burden’s baskets across the entryway of the Donna Beam Gallery, she abstracts adaptability and resilience by explicitly highlighting the lack of access and the determination of facing burdens through her use of desert yellows, oranges, and greens in conversation with Indigenous pine nuts.

Like Douglas, she sustains collaboration with other Indigenous artists via the Great Basin Artist Collective with the intent of controlling the narrative about their practice. The titles of her works speak to the ongoing legacy of limited representation at positions of power and visibility Indigenous artists have. “Indian people, even though so much of the population was wiped out, we never stopped creating,” she said. “If you want to look at our history, and specifically our art history, it always continue[s]. So we made it past our apocalypse. We’re

6 Orozco Rodriguez, Jazmin. (2021) “Indy Q&A: Paiute Painter Melissa Melero-Moose on Creating Space for Indigenous Art.” The Nevada Independent https://thenevadaindependent.com/article/indy-qa-paiute-painter-melissa-mele ro-moose-on-creating-space-for-indigenous-art

always here, we’re still here.”7 The extensive labor of organizing exhibitions like AH’-WAH-NEE, serve as a testament to the perseverance of that kind of work. From the pieces by Noelle Garcia of the Klamath, Modoc and Paiute tribes, we see that personal storytelling is persistently driven by the lingering influences of colonialism, Indigenous resistance and resolve to survive. In the recording of the symposium’s first panel, Garcia explains that, “The story comes first. A lot of my artwork is expressing memories or stories or trying to dissect them and coming to terms with them.”8 Garcia’s Cradleboard (2006), Now I Put You in the Ground (2012), Grandpa’s Birthday (2021) center the personal more explicitly. Each speaks to the circle of life–birth, celebration, and grief in conversation with Rifle (dad’s gun) (2021) and Revolver (Cowboy’s gun) (2019), beaded symbols of violence.

Garcia’s father is a prominent influence in her creative profile, most explicitly presented in Rifle (dad’s gun). Under the partnership Arts Everywhere made with National Coalition against censorship, Garcia revisits the injustice of her father’s life to situate the particularity of her privilege of being both heard and seen. Her father was convicted of murder, with a rifle being the murder weapon adds emotional weight to the piece. Beyond debilitating the gun, the meditative practice of beading an object connected to her father’s criminality highlights how Garcia, “spends time with a loved one or with a memory” to better come to terms with guns’ influence on her life. Though Garcia’s creative process is deeply personal, she is deliberate in creating work that engages broader social issues. Garcia’s work answers the questions she posed in Art, Freedom, and the Politics of Social Justice. Garcia asks, “Doesn’t art reflect our constant cultural shifting? If not prompt dialogue?” in response to Sam Durant’s College Art Association talk, where he states that he “think[s] that

7 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (December, 2021) Melissa Melero-Moose 8 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (December, 2021) Noelle Garcia

55

social and political problems and issues are being superimposed onto art and debates about art.”9 Garcia believes, “that’s what good art does.”10

“Good art” for so many Indigenous women artists featured in the exhibit is in constant dialogue with its environment. In seeking out a greater context for Santa Clara Pueblo artist Roxane Swentzell’s bronze sculpture, A Question of Balance (2021), I found the book A Question of Balance Artists and Writers on Motherhood edited by Judith Rosenburg.11 Rosenberg’s profile on Swentzell summarizes Swentzell as someone who integrates her artistic practice with her motherhood. When speaking of her practice and the significance of the pieces she produces, Swentzell says, “There’s that whole mentality that everything has to stay the way it is instead of letting it be affected by its surroundings.”12 With her feet firmly planted and balancing a vessel on her head, the sculpture evokes critical contemplation of how Indigenous people adapt to their surroundings and cultural shifts to thrive despite adversities.

These artists are reclaiming ownership over how they are depicted, honoring their layered existence. Photographer Cara Romero, of the Chemehuevi tribe, stumbled into photography as she was grappling with addressing the erasure of contemporary Indigenous life while pursuing her education. She said that, “People outside the rez and outside our cultures had no understanding of us…I knew [photography] was going to be the way to tell the story of my community, to tell the story of the pain and the beauty that I knew.”13 Placed

next to Swentzell’s sculpture, Romero’s photos create a visual reflection on how Indigenous women’s balance is as much about what they carry and where, as well as how they dance. Her photo WESHOYOT (2021) featuring a woman underwater, holding a basket surrounded by fishnets, converses with A Question of Balance by positioning the basket to the woman’s left in contrast with the basket Swentzell’s’s figure holds on her head. The figure’s movement expands on the adaptability of Indigenous women as demonstrated throughout the show, emphasizing the many ways to carry the stories they tell. Next to WESHOYOT, GAEA’s (2021) figure is dancing in ballet slippers on the sand reminding us that joy, dance, and play are equally important. The embodiment of Mother Earth, a shared source of inspiration for many of the artists, depicting her in dance, in joy, speaks to the beauty and wonder that drives Romero’s ethical impulse to counter dominant narratives of Indigenous women.

Mixed media artist Natani Notah, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation, explores Native women’s experiences through their histories. The corpus of Notah’s aims to critique cultural appropriation and pull from her lived experiences.14 Natani balances her commitment to appropriation and aesthetic through an investment in the personal. Inspired by her father and supported by her family, she committed her life to creating. Notah’s works complement Romero’s celebration of femininity, play, and joy. Notah’s watercolor pieces, Come in the Water is Nice (2021) and Call Her Sunset (2021), evoke delight and play. She reflects that those pieces are more experimental where, like Garcia and Shelby Westika, she aimed to create intentionally abstract items.15

9 Garcia, Noelle. (2018) “Art, Freedom, and the Politics of Social Justice.” Arts Everywhere https://www.artseverywhere.ca/author/noellegarcia/ https://www.artseverywhere.ca/politics-of-social-justice/

10 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (December, 2021) Noelle Garcia

11 “A Question of Balance: Artists and Writers on Motherhood.” (1995). Publishers Weekly, 242(25), 54. PWxyz, LLC.

12 Ibid. p. 87

13 Vagner, Kris. (2021) “Meet the women of Ah’-Wah-Nee” Double Scoop https://www.doublescoop.art/meet-the-women-of-ah-wah-nee/

Notah balances the abstract with the intentionality of repurposing items in her sculptures. As a panelist at the symposium, she, “see[s] value in things that are

14 https://vimeo.com/320013343 Natani Notah - ISCxGFC Residency (2019)

15 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (February 2022) Natani Notah

56

discarded,” wanting to give them, “a second chance at life.”16 Her mixed media sculpture, Lady in Beads (2021), gives a second life to a t-shirt she slept in for years. She felt she could relate to the Native woman illustration on the front of the shirt, because in her image she saw, “one of longing for transformation.”17 Notah’s reflection on her sculpture speaks to the greater motivation behind Douglas’s vision, particularly one aiming to transform the meaning of her positioning as a student to be one that could, through curation, make more visible the creative works of her colleagues, role models and inspirations.

So much of that inspiration Notah speaks to stems from the adaptability many of the artists embodied in their careers or in their relationship to technique and artistry. When I asked her to elaborate weeks after the symposium, she explained that, “The conceptual framework of ‘making the most with the least’ became the best way I could explain my approach to my creative process. I think it translates through the material choice to use second hand objects or garments as a source of fabric for many of my soft sculptures.”18 In the context of her earlier works and interviews, the process of giving the discarded a second chance at life, she shifts its meaning, reimagining the potential of the worlds around them.

Shelby Westika’s (Zuni Pueblo) pieces similarly explore the worlds around them, with attention to the modern and digital worlds in which they play. Westika writes that both the mixed media piece, Dream (2020), and digital painting, Eye of the Storm (2021), “connect the visuals of gaming, music, and my emotions in a painting. Both build a harmonious melody that embodies the rhythm of the music and sounds from the game and clicks of the keyboard

16 Apex Art NYC. (2021) “Native Feminisms Artist Interview” YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCBhR_yzjXg apexart NYC 1/15/21

17 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (February 2022) Natani Notah

18 Ibid.

and mouse.”19 Positioned between A Question of Balance and Notani’s three pieces, Westika’s Dream asks the viewer to consider what other worlds could be possible for Indigenous artists, expanding on what Indigenous artists adapt and integrate of their lived experiences in their work.

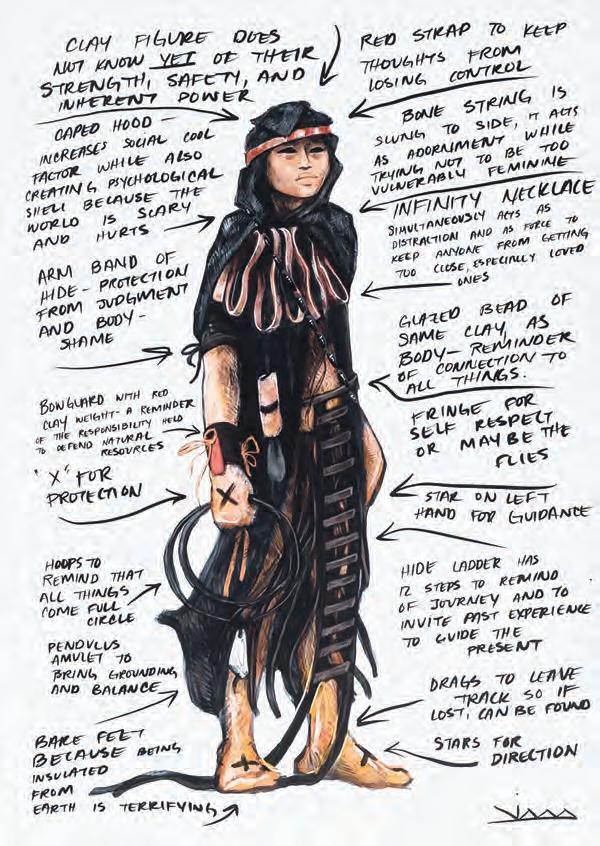

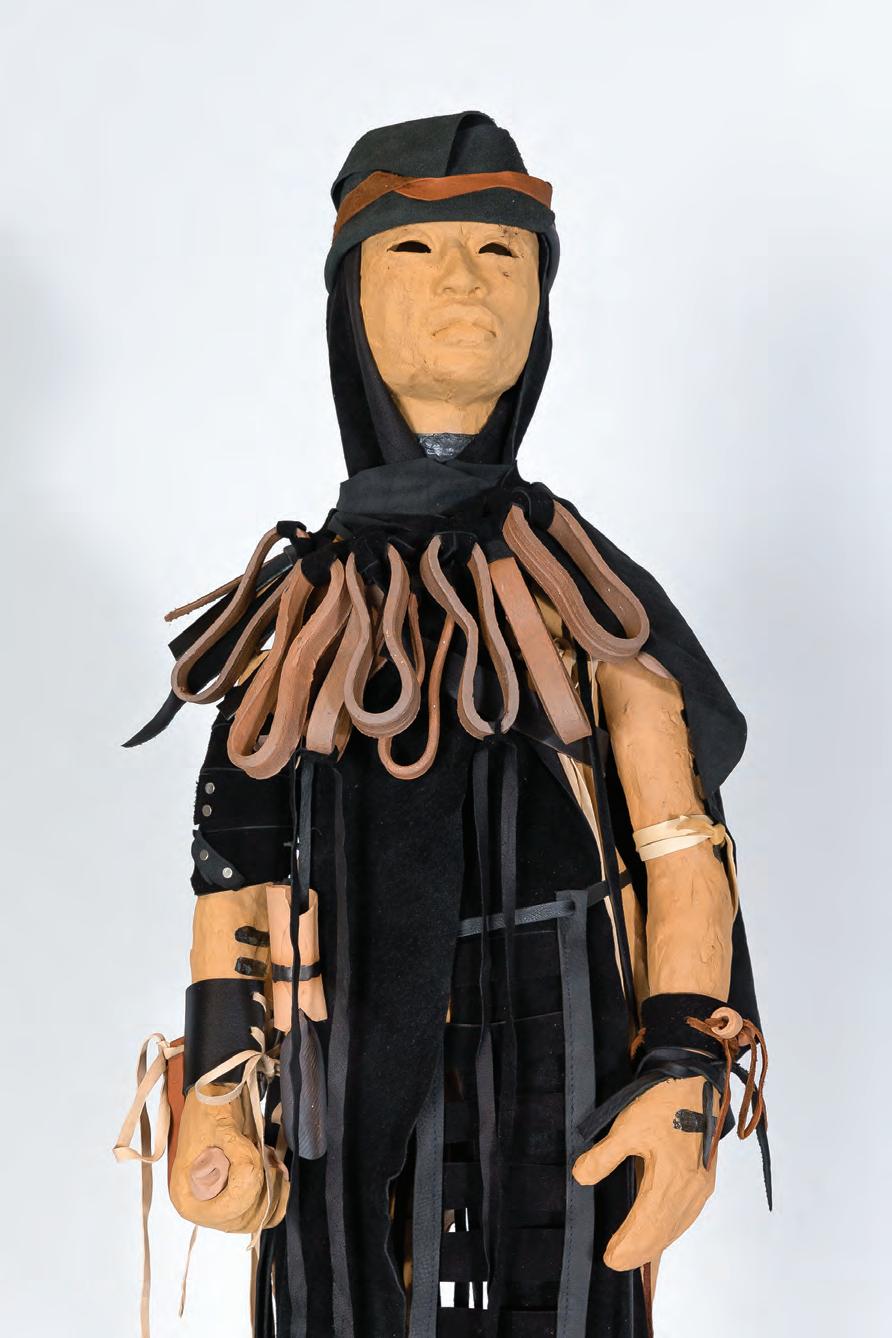

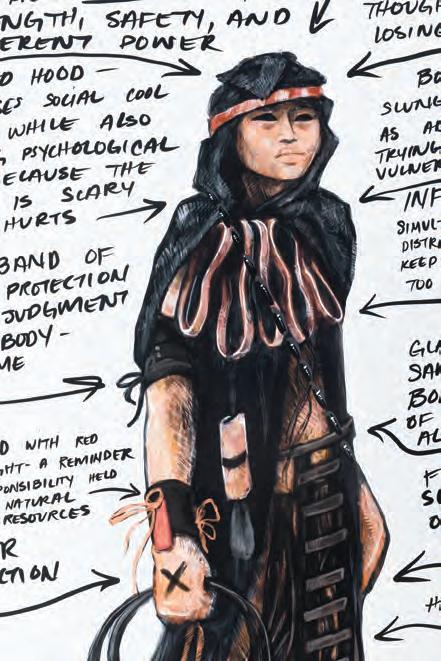

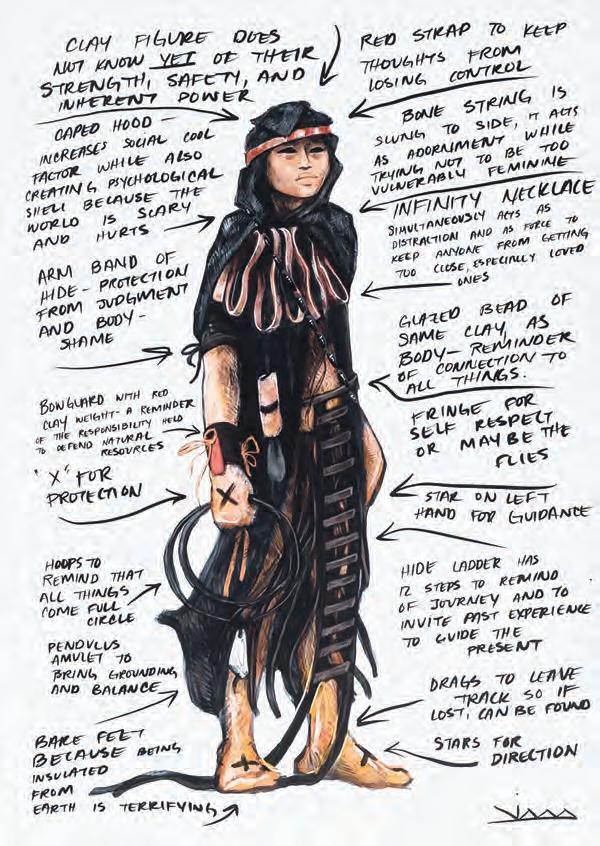

Rose B. Simpson’s (Santa Clara Pueblo) sculpture in the exhibition, Innate (2021), clothed in protective gear may appear to expand upon the message of the artist’s 2014 Maria. With Maria, Simpson, “craft[ed] post-apocalyptic Indigenous warrior accouterments out of leather, metal, found objects, and ceramic components.”20 On further discussion, however, Simpson and Douglas explained that Innate was not supposed to be displayed wearing the protective gear. The accompanying drawings of the clothed figure were meant to function as a key to the, “protective crap’s meaning and what the figure would have looked like adorned with it.”21 In other words, while Maria was centered on showcasing protection, Innate was supposed to depict vulnerability. Completed days before being delivered to the show, Simpson’s Innate intends to move beyond what Maria had done. The accouterments were supposed to surround the figure instead of it being adorned. Simpson intended to have the Innate sculpture unwrapped and posed in between images that explained the figure’s, “transition from feeling the need to ‘protect’ oneself with warrior imagery or ‘stuff.’”22 While Douglas explained that she offered to remove the adornments after the symposium, time hadn’t permitted it, and Simpson decided to leave it as is. I followed with her regarding how she felt about the piece not being displayed as she intended,

19 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (January 2021) Shelby Westika

20 Simpson, Rose. The Massachusetts Review, Volume 61, Number 4, Winter 2020, pp. 665-676

21 Abad, Erika. Correspondence with artists (December, 2021 – January 2022) Rose B. Simpson

22 Ibid.

57

and she explained that, “I think there’s a reason for everything, and the piece couldn’t be ‘unwrapped’ and vulnerable just yet, for whatever reason.”23

The vulnerable figure Simpson envisioned unwrapped, aimed to express, “The idea that…we are ‘innately’ protected, beautiful, prepared, loved, even (and especially) in our vulnerability.”24 The joy, forgiveness, play and utility AH’-WAHNEE’s artists explore through their work diversely balance vulnerability and story, reinforcing Douglas’s ongoing efforts to make visible the artists’ humanity, resilience, and artistic brilliance. The process of organizing the symposium and exhibition was an exercise of Douglas’s vulnerability. She roots her artistic and social praxis in Indigenous resistance and expresses a desire for the greater celebration of Indigenous creative technique, storytelling, and visibility.

In the ongoing dialogue of balance, Innate’s presentation brings the discussion full-circle in unexpected ways. While Douglas intended to remedy the situation, the demands on her time–as she was organizing her collaborative performance with Simpson in the days following the AH’-WAH-NEE symposium— affected the potential of immediate follow-up. The incomplete dialogue and subsequent shift in display points to our ongoing responsibility to be mindful of listening and supporting Indigenous women. While bearing witness to the consequences of their communities’ genocide and attempts at erasure and human rights’ abuses, these Indigenous artists’ works embody the spiritual healing they navigate through their artistic practice. In light of the ongoing demands on their time and continued efforts to uplift their people, their efforts at telling their stories often come under strain given the extensive rewriting and reimagining they have to do. Rewriting how the West and their historic colonizers have written them is a lifelong process, often engaging with multiple audiences at once. These artists are but a few who set a

precedent for doing it well. As both curator and artist in conversation with them, Douglas set a standard for a student’s commitment to positioning herself in conversation with an ongoing legacy that decenters Western training.

As UNLV, among other institutions, normalizes land acknowledgments, institutions also need to take responsibility for what it means if, when, and how students labor over inserting themselves and their communities into the institution. Returning to Noelle Garcia’s question regarding why people are listening now, AH’-WAH-NEE reminds us that Indigenous people were never silent. Furthermore, the exhibition and the symposium take time and care to say they continue to create, find joy, resist, and tell the stories because it is as essential to their survival as it is to ours. Even in the capitalist seduction to forget, they will continue to insist we remember.

Dr. Erika Gisela Abad, Ph.D. Assistant Professor-in-Residence, Gender & Sexuality Studies and Interdisciplinary Degree Programs

(Opposite) We Danced, We Sang, Until the Matron Came—Dances of Resilience,

UNLV

58

23 Ibid. 24 Ibid.

Paul Harris Theatre,

SYMPOSIUM

The November 5, 2022 AH’-WAH-NEE Symposium artist panel discussions at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Auditorium and the performance We Danced, We Sang, Until the Matron Came at The Paul Harris Theatre were filmed by documentary filmmaker Ben-Alex Dupris. The videos are available to view on the UNLV College of Fine Arts YouTube page.

Clockwise from left: Cara Romero, Artist Lecture; Symposium Panel, Noelle Garica, Loretta Burden, Cara Romero; Symposium Panel, Natani Notah, Rose B. Simpson, Fawn Douglas; Stacey Montooth, Nevada Indian Commission, speaks about Stewart Indian School at the Paul Harris Theatre.

60

The November 5, 2022 AH’-WAH-NEE Symposium artist panel discussions at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art Auditorium and the performance We Danced, We Sang, Until the Matron Came at The Paul Harris Theatre were filmed by documentary filmmaker Ben-Alex Dupris. The videos are available to view on the UNLV College of Fine Arts YouTube page.

Kadie Ann Anderson, Fancy Shawl Dancer (blue and purple), Jared Chee-Anderson, Traditional Dancer, Sol Martinez, Jingle Dancer, Gianna Yazzie, Fancy Shawl Dancer (blue, pink, black)

61

62

Left to Right, Kadie Ann Anderson, Jared Chee-Anderson, Jaiden Kennan Anderson, Sol Martinez, Amaia Marcos, Gianna Yazzie. Cultural gathering in celebration of the AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition at Nuwu Art + Activism Studios.

Cultural gathering in celebration of the AH’-WAH-NEE Exhibition at Nuwu Art + Activism Studios.

63

PHOTOGRAPHY

All photographs by Mikayla Whitmore

Cover: Melissa Melero-Moose

Back cover: Cara Romero

FURTHER READING

Reed, C. Moon. (2021) “Connecting past and present, AH’-WAH-NEE celebrates Indigenous female artists.” Las Vegas Weekly https://lasvegasweekly.com/ae/fine-art/2021/nov/04/connecting-past-and-present-ah-wah-nee-celebrates/

Westika, Shelby. Artist Website https://www.shelbywestikastudio.com/about

Kunts, Visuell. (2021) “Rose B. Simpson” https://podcasts.apple.com/no/podcast/pulling-on-the-thread/id1557556237?l=nb

Mason Hunter, Linda. (2003) “Living in Balance: A Pueblo Woman Discusses Her Balanced Life Philosophy.” Mother Earth Living. https://www.motherearthliving.com/gardening/Living-in-Balance/

Notah, Natani. “Artist’s Statement” https://www.headlands.org/artist/natani-notah/

Tower Gallery, Roxane Swentzell (2021) https://www.roxanneswentzell.net/roxanne_swentzell_public_arts.htm

(2019) “Rose B. Simpson Explores the Human Condition through her Native American Past.” Elephant. https://elephant.art/ ceramic-twins-and-spiritual-space-in-rose-b-simpsons-sculptures-native-american-pueblo-home/

Collier, Angie (Kichi). (2013) “Rose Bean Simpson, Santa Clara Pueblo.” https://contemporarynativeartists.tumblr.com/ post/39391980928/rose-bean-simpson-santa-clara-pueblo -

(2015) “Episode 27: Interview with Rose B. Simpson.” Broken Boxes Podcast http://www.brokenboxespodcast.com/ podcast/2015/3/5/episode-27-interview-with-rose-b-simpson

64

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project is funded in part by a grant from Nevada Humanities, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Thank you to the AH’-WAH-NEE Partners:

Black Mountain Institute

The Cosmopolitan of Las Vegas Desert Arts Action Coalition

Howard Watts, Nevada State Assembly member

Indigenous AF Inc. Indigenous Educators Empowerment

The Las Vegas Paiute Tribe

Meow Wolf

National Endowment for the Humanities Nevada Arts Council

Nevada Humanities

The Nevada Indian Commission Nevada Museum of Art Nuwu Art + Activism Studios

The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians Southern Nevada Conservancy UNLV American Indian Alliance UNLV College of Fine Arts UNLV Department of Anthropology UNLV Department of Art UNLV Department of History UNLV Interdisciplinary Gender & Ethnic Studies UNLV Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art UNLV Minority Serving Institution Student Council UNLV Native American Alumni Club

UNLV Paul Harris Theatre WESTAF (the Western States Arts Federation)

And thank you to all who contributed to realize this significant project.

65

66

UNLV COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS

The College of Fine Arts, a creative nexus anchored within the vibrant and diverse culture of Las Vegas, boldly launches visionaries who transform the global community through collaboration, scholarship, and innovation.

At UNLV we illuminate the power of the arts amidst breathtaking advancements in science and technology. In doing so, we are creating a global destination at the forefront of transforming arts and design. To accomplish this we encourage agency, inventiveness, problem-solving, and big-idea thinking in our students, faculty, and staff. We make education relevant through curriculum and effective learning outcomes. We are passionate and compassionate, principled and supportive, joyful and kind. We believe in inclusion, invention, transformation, engagement, and rigor. These vital principles underpin all our efforts and guide us in fulfilling our mission.

67

DONNA BEAM FINE ART GALLERY

UNLV has a history of supporting the visual arts beginning in 1969 with the first art gallery that opened in Archie C. Grant Hall. A second gallery was added in 1981 in the then, newly-constructed Alta Ham Fine Arts Building. In 1987 it was remodeled and enlarged, and the name it now carries, Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery, is in honor of the daughter of Thomas Beam, whose generous donation made the expansion possible. The gallery is free to the public and open on a regular basis throughout the year.

The Donna Beam Fine Art Gallery actively supports the university’s Top Tier mission of, “… achievement through education, research, scholarship, creative activities and clinical services.”

The gallery provides a venue for exhibitions that tap into the variety of creative activities in contemporary art and encourages freedom of individual thought, expression, and artistic consciousness. A year-round exhibition schedule offers the work of student and faculty artists, artists from the region and throughout the U.S., and from lands across the globe.

The mission of the Donna Beam Gallery is to stimulate and enrich the cultural vitality of a diverse UNLV community and all who visit the gallery.

The Donna Beam Gallery draws upon recognized as well as up-and-coming artists, critics, and scholars to fulfill programming goals. The focus of the gallery is to support and augment classroom instruction. Our primary purpose is to educate our audience, and also to excite, enlighten, and inspire, and to enrich the art curriculum of the university. In any given year the gallery presents from seven to 15 exhibitions, which can range from one-person shows, group or theme shows, to faculty exhibitions, MFA thesis exhibitions, BFA group shows or juried student exhibitions. The gallery also serves as a teaching gallery for students learning gallery practices.

4505 S. Maryland Pkwy. Box 455002 Las Vegas, NV 89154 702-895-3893 www.unlv.edu/donnabeamgallery

68

(Opposite) Loretta Burden. Fish Trap (detail), 2020.

Fawn Douglas Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands (detail) 2021

Fawn Douglas Nuwuvi: Our Bodies, Our Lands (detail) 2021

AH’-WAH-NEE installation (left to right): Melissa Melero-Moose. Making a Burden Basket, 2021. Rearranging, 2021. Jean LaMarr. Sacred Places Where We Pray, c. 1964.

AH’-WAH-NEE installation (left to right): Melissa Melero-Moose. Making a Burden Basket, 2021. Rearranging, 2021. Jean LaMarr. Sacred Places Where We Pray, c. 1964.