The State of Design in Nebraska and Surrounding Territories

Actual Architecture

Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture

BVH Architecture

Carlson West Povondra Architects

DLR Group

The Heartland Interior Design

HDR (Great Plains Studios)

LEO A DALY

RDG Planning & Design

Sinclair Hille Architects

TACKarchitects

Premiere Issue Fall 2023

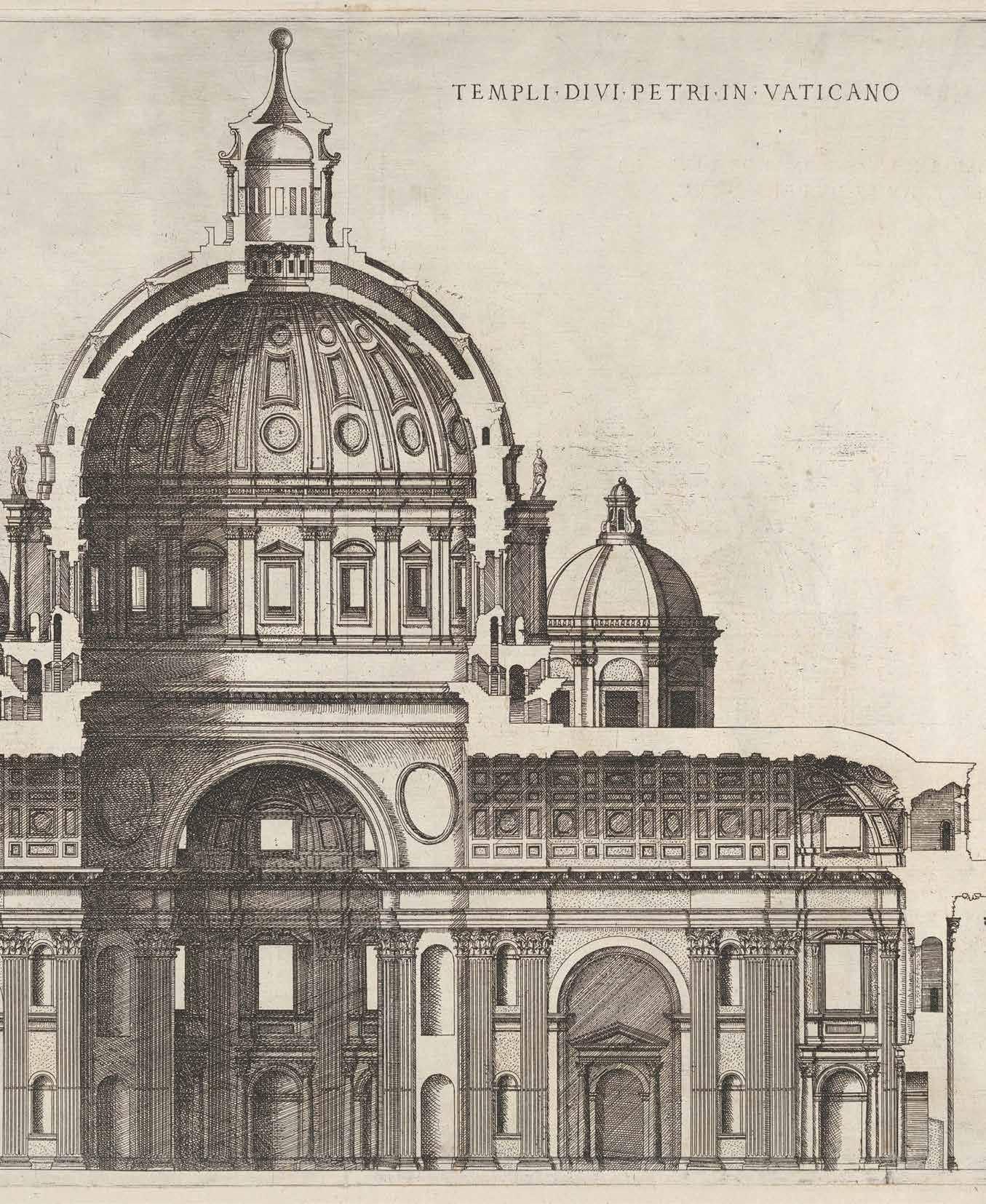

Form follows function.

Form follows form.

Form follows beauty.

Louis Sullivan

1895.jpg; Guaranty (Prudential) Building, Church Street and Pearl Street, Buffalo, NY 5267453990; Sony Building

David Shankbone crop.jpg|thumb|Sony Building by David Shankbone;

Niemeyer Quelle: selbst fotografiert am 21.11.2002, Fotograf oder Zeichner: Ulrich Gärtner

circa

by

Oscar

LouisSullivan,Architect

Philip Johnson, Architect Oscar Niemeyer, Architect

LESS IS MORE LESS IS A BORE

Mies van der Rohe (left), Robert Venturi (right).

Why Unicameral?

A defining element of the State of Nebraska is the fact that our state government consists of a single or unicameral legislative body. It is something that is unique to our state alone in the great diversity of the United States of America. Throughout Nebraska’s history, our small population has made it necessary to work together and think differently. Therefore, the idea of a design publication for the State needs to be one that blurs boundaries and break down traditional formations with a singular disciplinary focus.

This design publication will also look to engage across the traditional categories of academic faculty, professional practitioners, and the students that ultimately enter these worlds after they have completed their period of study and internship. The publication will occupy a middle ground that takes the worlds of magazines and journals and combines them.

It will be formed to create a unified creative team comprised of members of the University of Nebraska, College of Journalism and Mass Communication, the Johnny Carson Center for Emerging Media Arts, the College of Architecture, and members of the State of Nebraska’s diverse design professions.

Unicameral will combine the public outreach and audience of a magazine and merge it with the focus of a journal. Its aim is to provide a window into Nebraska’s design culture, work(s), ideas, and personalities that create and define our communities, urban spaces, workplaces, and homes.

Photography: Dana Damewood. Reprinted with permission of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States. OPPOSITE PAGE Photography: Madeline Cass.

By supporting Unicameral these groups and individuals attest to their belief in the power of design and its importance in creating great environments, places, and products in the great state of Nebraska and surrounding territories. This publication would not exist without their passion and commitment to great design in the middle of everywhere. Thank you for continuing to make Nebraska a great environment to practice and create.

To the students, professionals and faculty of Unicameral—thank you.

AIA Nebraska AOI DLR Group Nebraska Masonry Alliance GreenSlate Development

HDR (Great Plains Studios) IIDA Great Plains Chapter LEO A DALY Noddle Development Company

Olsson Ronco Construction RDG Planning & Design Sheppard’s Business Interiors | Steelcase

TACKarchitects Tom & Amy Trenolone Whiting + Turner

EDITOR IN CHIEF Thomas J. Trenolone, FAIA

ART DIRECTOR Encarnita Rivera

SENIOR EDITORS Brendan Colford, Bridget Knudtson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Vy Cao, Caroline Goertz, Audrey Huse, Louis Khu, Mitch Neujahr, Jay Quemado, Emily Scheidler, Tiffany N. Scwheer, Anastasia Wand, Megan Willoughby

COPY EDITOR Kathryn Ineck

CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATORS Vy Cao, Audrey Huse

EDITORIAL SUPPORT Danette Hunter

EDITORIAL OFFICE: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, College of Architecture

400 Stadium Drive, Lincoln, NE 68508

PHOTOGRAPHY OF PROJECTS : AJ Brown, Madeline Cass, Colin Conces, Dana Damewood, Corey Gaffer, Thomas Grady, William Hess, Kurt Johnson, Emma Morem, Tom Kessler, Lea Schuster, Dan Schwalm

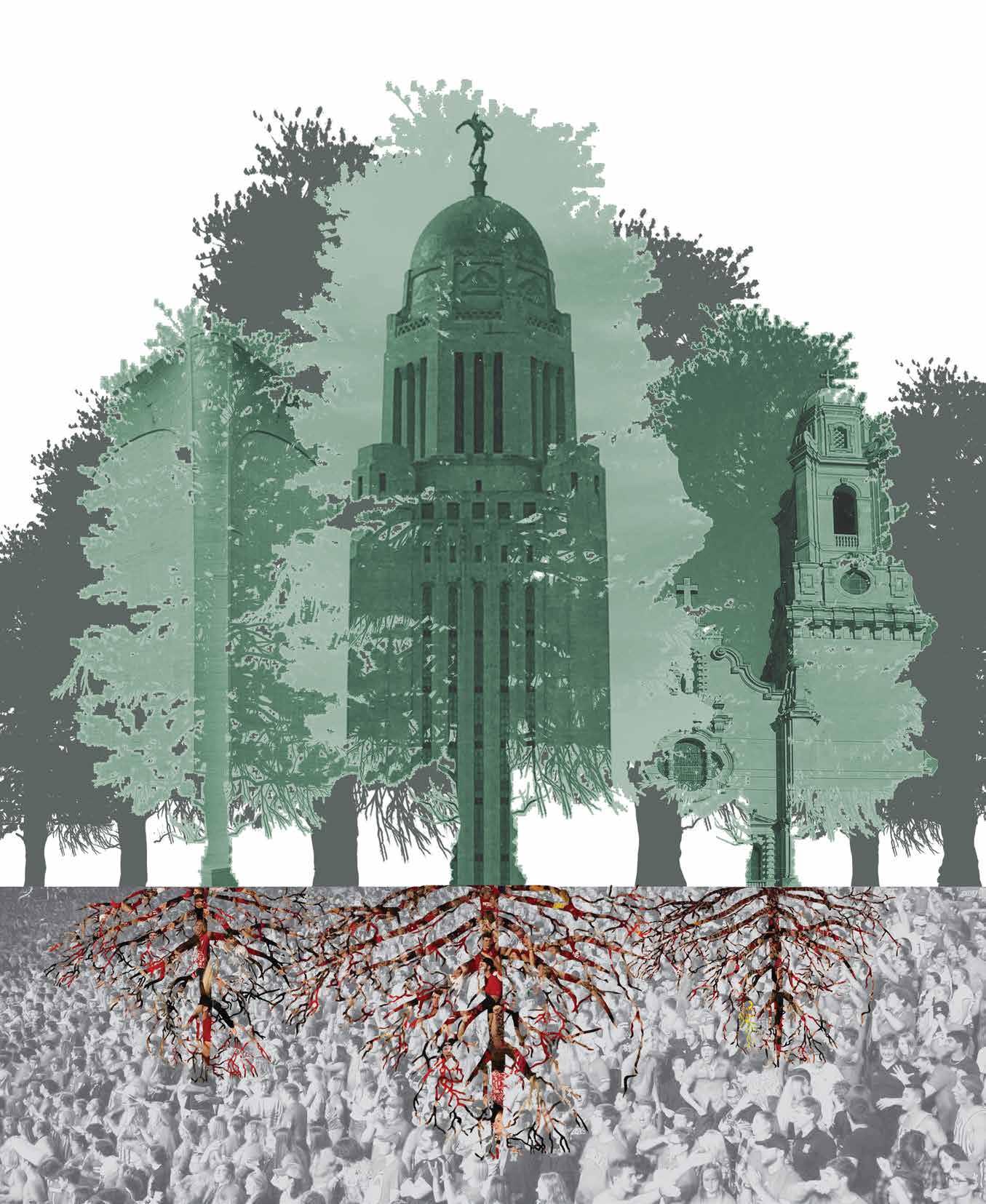

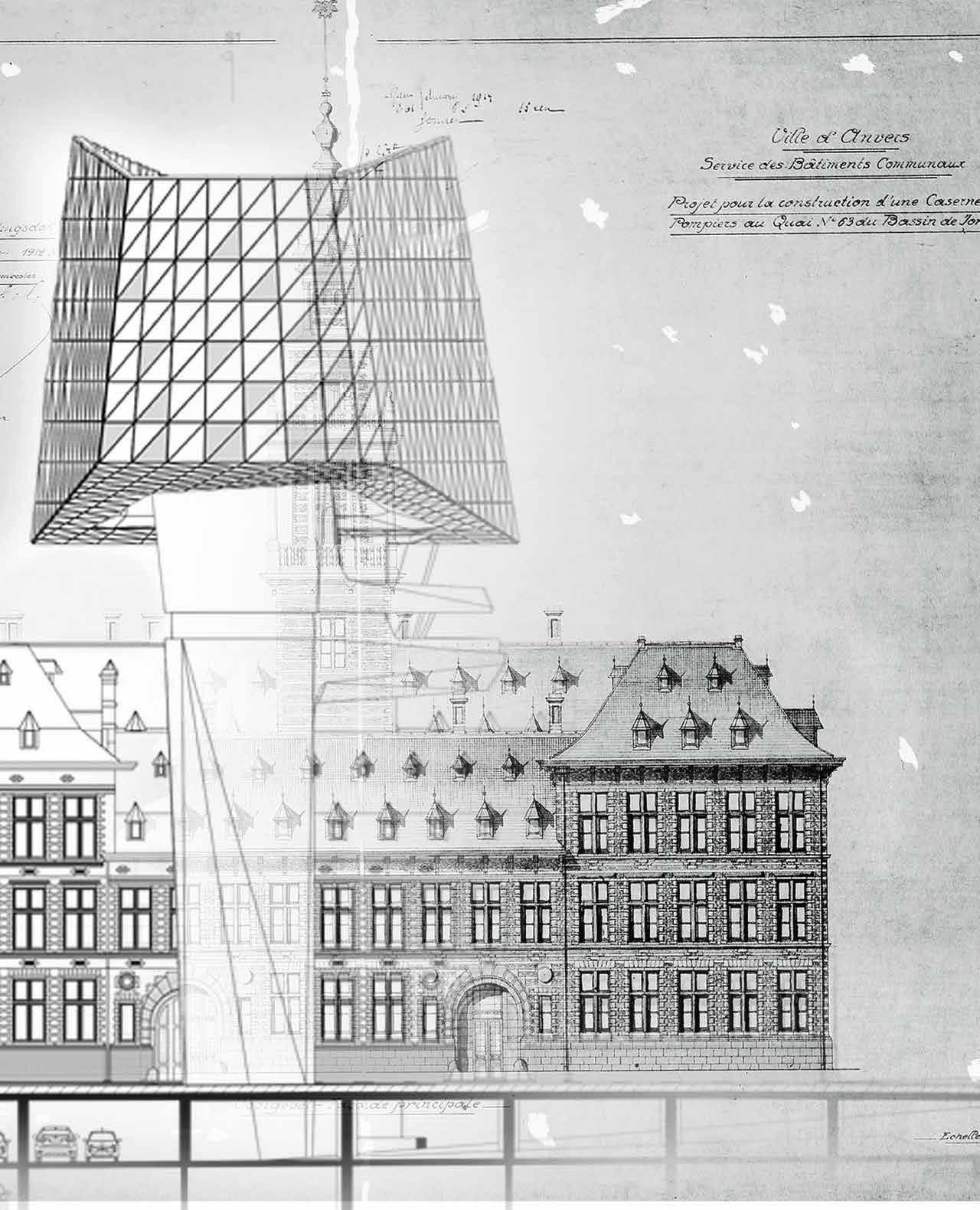

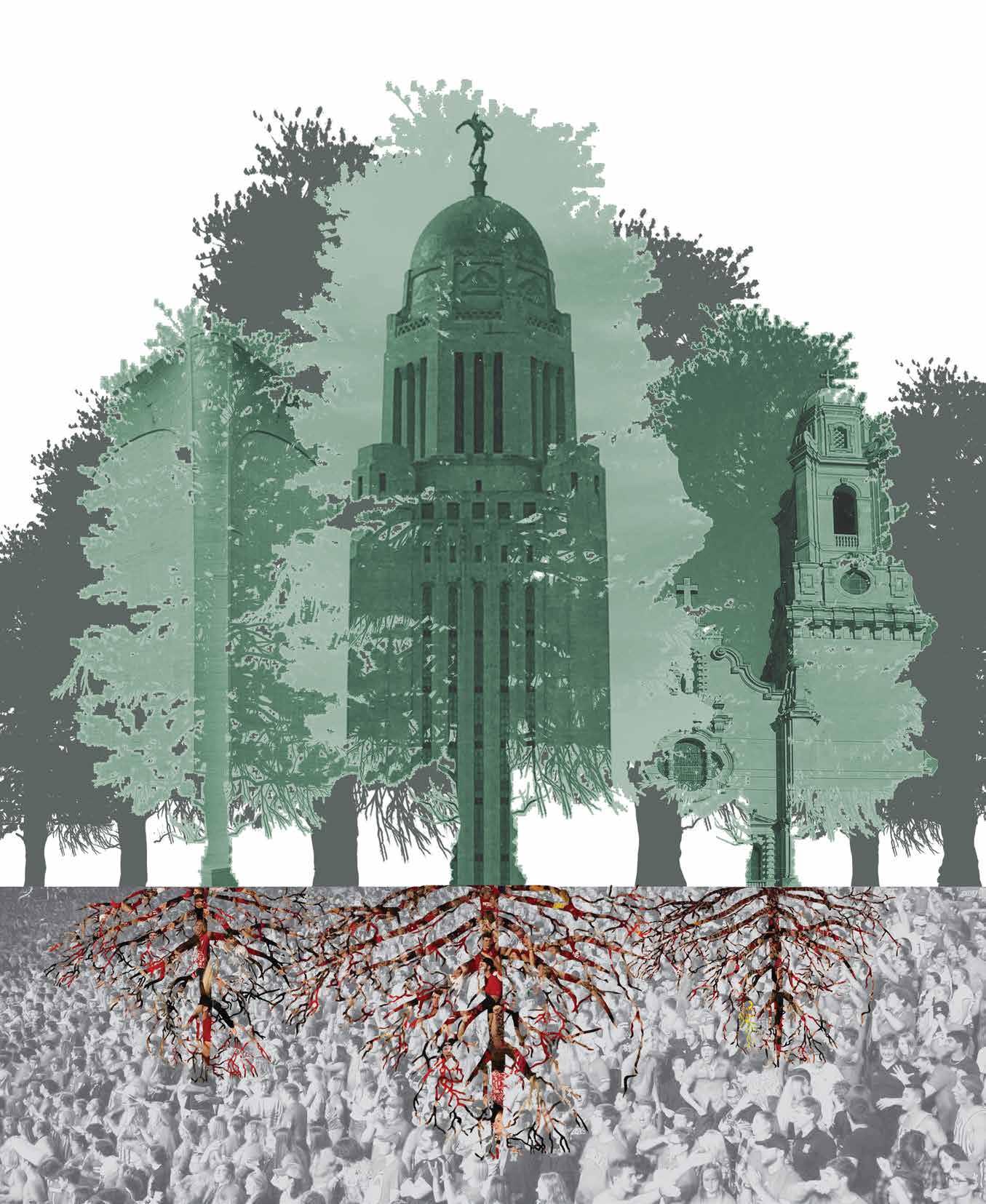

COVER ART: Collage by Bridget Knudtson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

College of Architecture; Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg, Ph.D., Dean, David Karle, Associate Professor and Director of the Architecture Program, University of Nebraska College of Architecture Professional Advisory Committee

College of Journalism and Mass Communication; Shari R. Veil, MBA, Ph.D., Dean; Adam Wagler, Associate Dean for Academic Programs

Johnny Carson Center for Emerging Media Arts; Megan Elliott, Founding Directo r; Ash Smith, Assistant Professor of Emerging Media Arts

Barnhart Press; John Barnhart, President

HDR (Great Plains Studios); Matt Whaley, Managing Principal

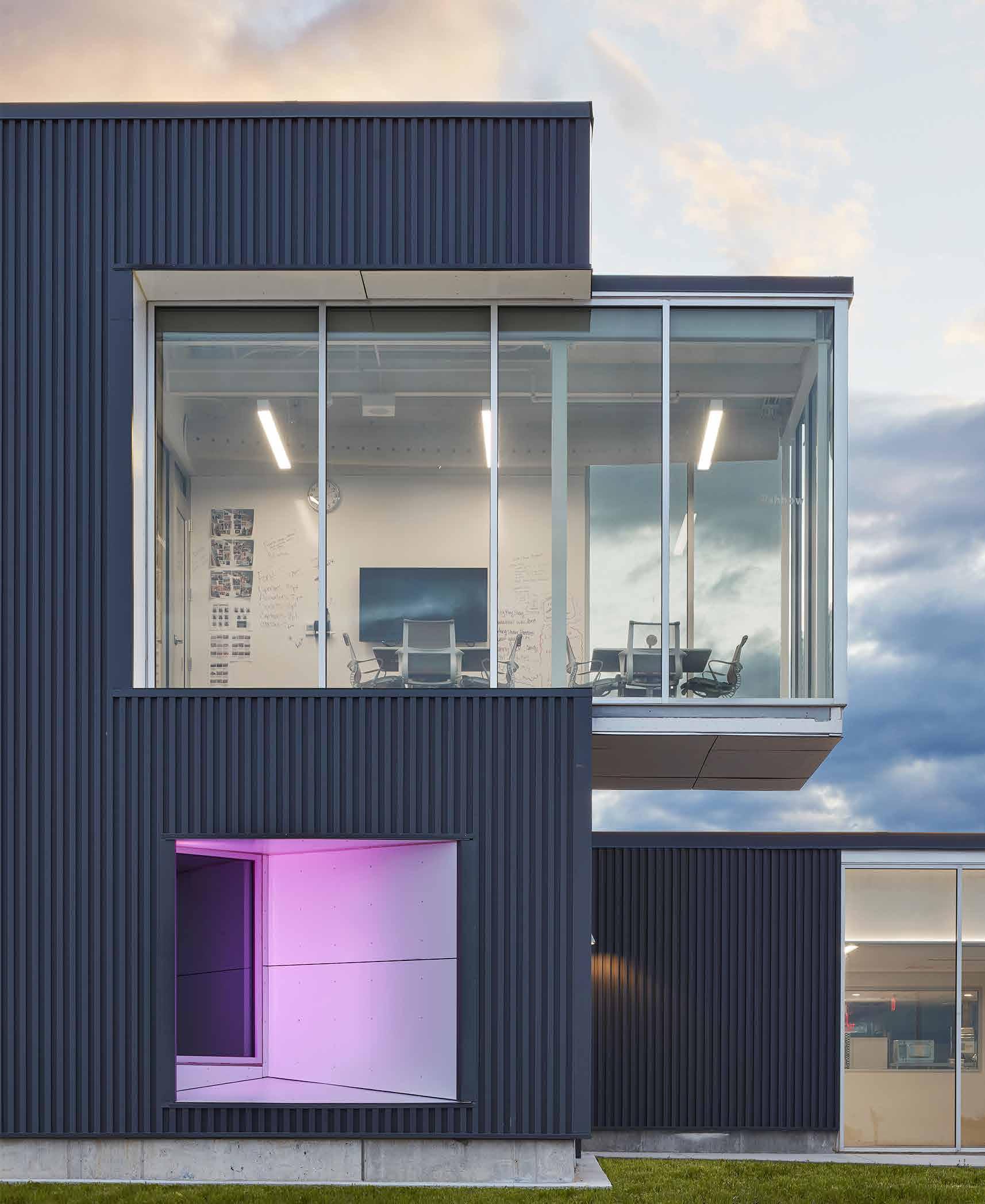

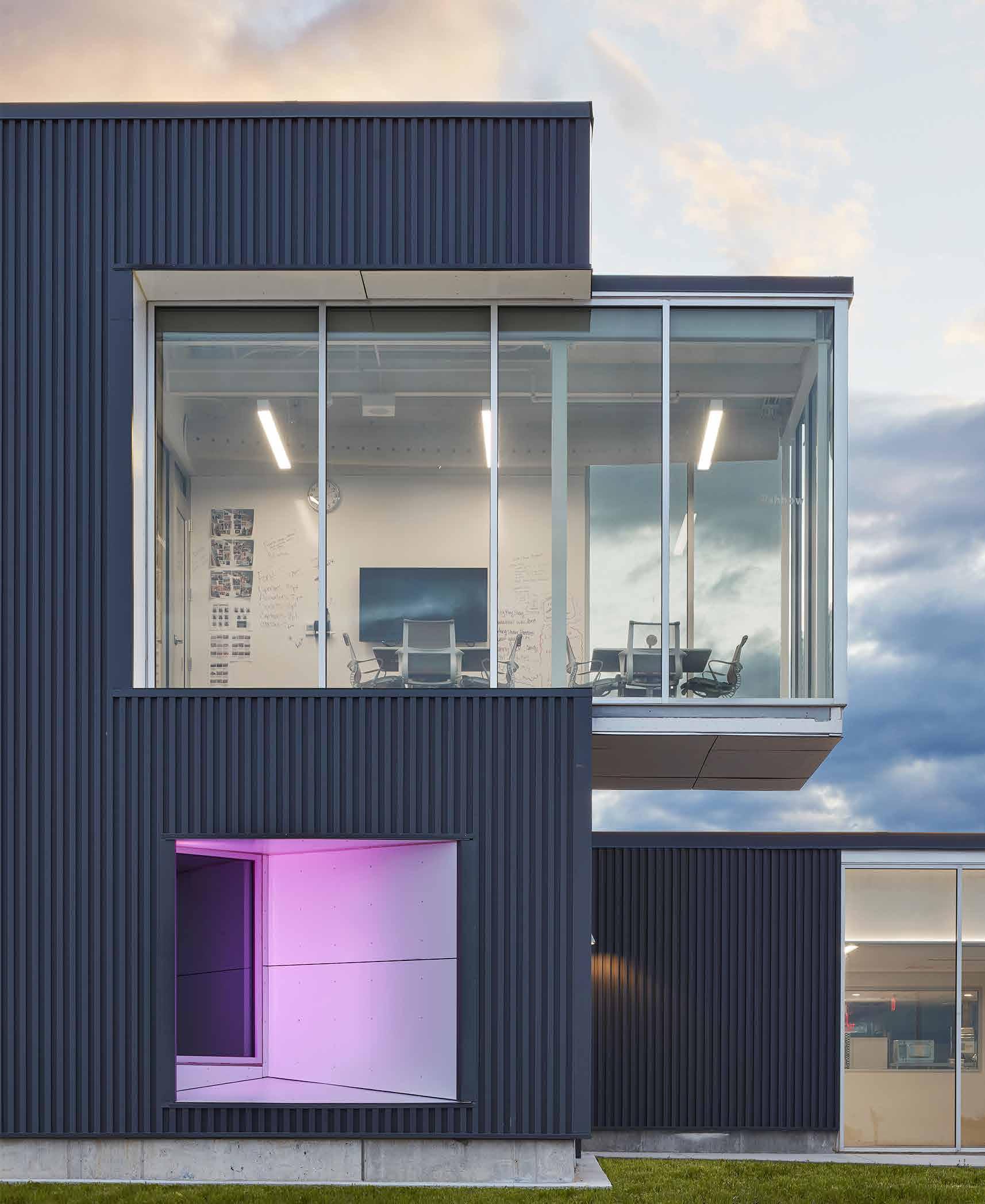

Photography: © 2023 Dan Schwalm, OPPOSITE PAGE © 2023 Colin Conces

WINSTON CHURCHILL

WE MAKE A LIVING BY WHAT WE GET.

WE MAKE A LIFE BY WHAT WE GIVE.

Printed by Barnhart Press, Omaha, Nebraska. PROFESSIONAL & ACADEMIC PARTNERS

18 Love, Aretha Franklin, and the Dead Poets Society 50 Split or Steal 60 An Evolving Urban Core 68 Redlining’s Ripple Effect 86 The Case for Community Engagement 106 There’s No Place Like Home 116 Entangled Evolution 126 Hostile Architecture 170 Becoming a Master of the Archido Arts –One Must Have Balance

Essays

Design

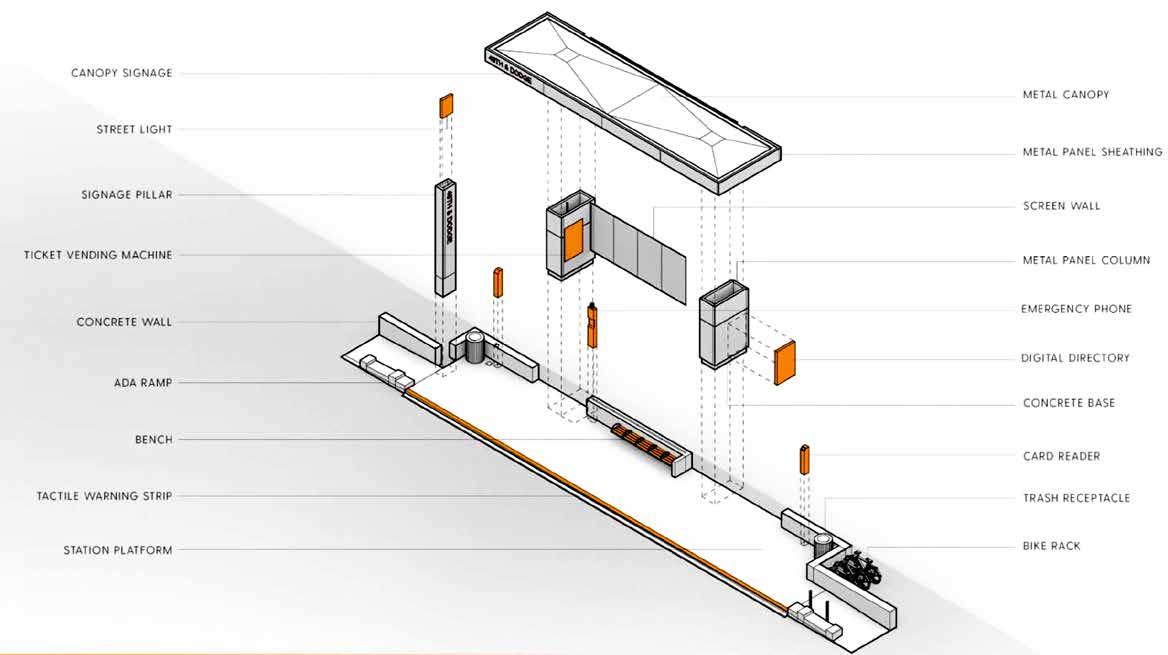

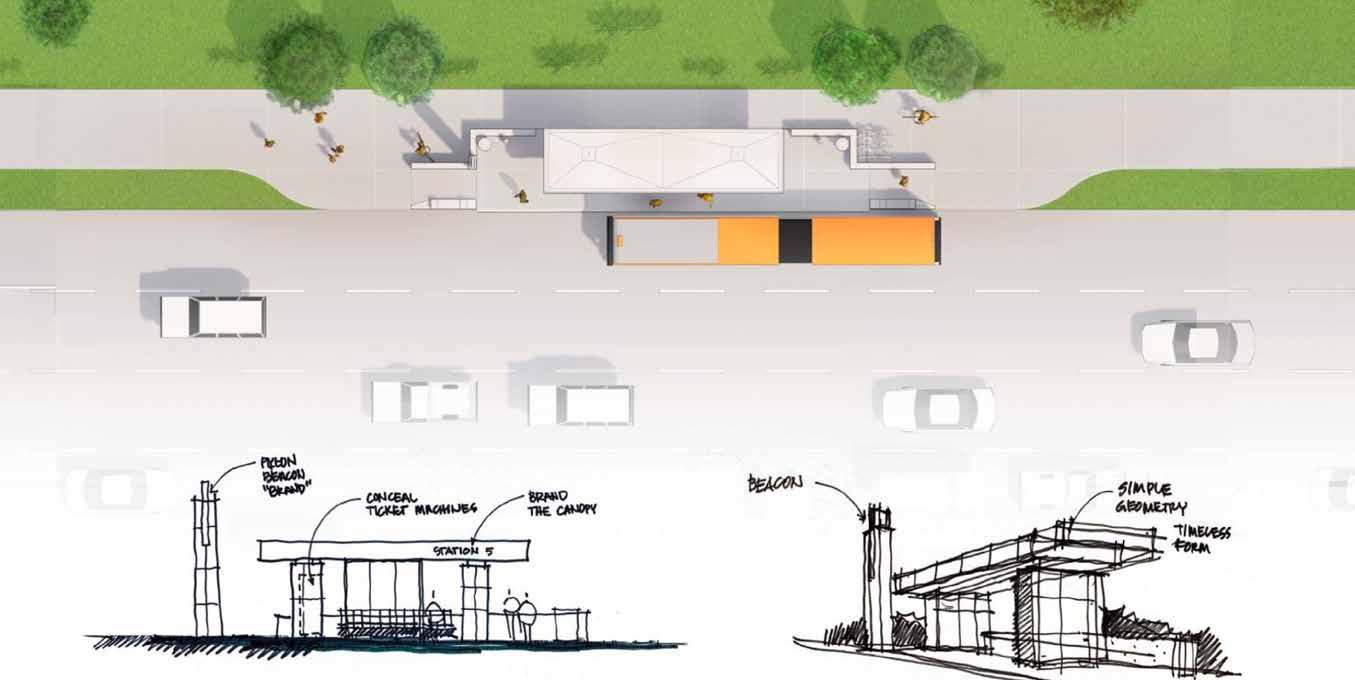

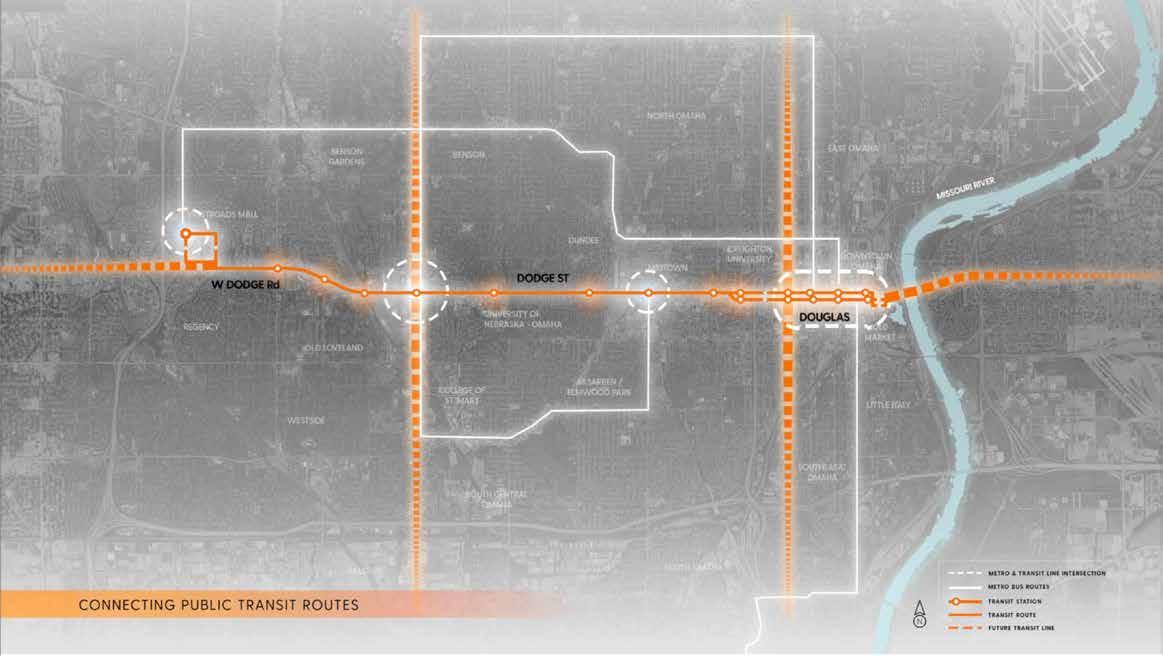

RDG Planning & Design 20 Entrepreneurial Studio 20 RDG Landscape Architecture 22 Omaha Office Central Stairs 24 First National Bank, CSU 28 The New North Makerhood 34 Casper Wayfinding Master Plan 40 La Vista Civic Space 44 Carlson West Povondra Architects 54 Lexus of Omaha 58 Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture 62 The Switch Beer and Food Hall 66 HDR (The Great Plains Studios) 72 Judy Varner Adoption and Education Center 74 Siena Francis Miracles Treatment Center 78 HDR feat. Sinclair Hille Architects 82 Concordia University Music Center 82 TACKarchitects 90 Bridges Trust 92 Dvorak Law Group 100 LEO A DALY 110 Omaha Rapid Bus Transit (ORBT) 110 DLR Group 118 UNL Dinsdale Family Learning Commons 120 Nebraska Medicine PES Unit 124 Actual Architecture Company 130 DVLP Basketball Training Center 132 The Heartland Interior Design 138 Lulubee Artisanal Chocolates 138 BVH Architecture 144 Crete Public Library 146 Barnato Entertainment Venue 152 Nebraska Center for Advanced Professional Studies (NCAPS) 158 Niobrara River Valley Preserve Visitor Center 164 Feature Stories

Editorial

By Thomas J. Trenolone

By Thomas J. Trenolone

FANBOY LETTER TO THE DESIGN DISCIPLINES / CULTURE IN NEBRASKA

I am a fortunate son, as I am a Nebraska native: I arrived here via Archbishop Bergan Mercy Hospital on July 1, 1970, in the pre-dawn hour of 4:01 AM CDT, to be exact. Since that moment, regardless of where I have called home, this wonderful place in the middle of everywhere has defined me in so many ways. As I have gotten to know so many of my colleagues here in the heartland, I have learned that this is a common thread we all seem to share regardless of where we practice, be it Kearney, Kansas City, New York, or Paris.

The intent of this publication is to be a snapshot in time, one that features professionals and academics contributing to our design culture. It is written, curated, and directed by the students at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and printed in partnership with chambers of commerce, professional organizations, and community groups that advocate for the importance that good design and creative businesses contribute to our state’s health, economy, and overall vitality.

The essays included in this magazine are written by students about topics on their mind regarding our professions and the features reflect the outcomes of the awards juries held by the local and regional chapters of the AIA, IIDA, and ASLA. In this manner, we see Unicameral as a consolidated outreach for each of these great professional organizations. When we asked the students to write a feature, we asked them to consider three things: the people who did the work, the place where the work was done, and, ultimately, the project that was the outcome of this chemistry.

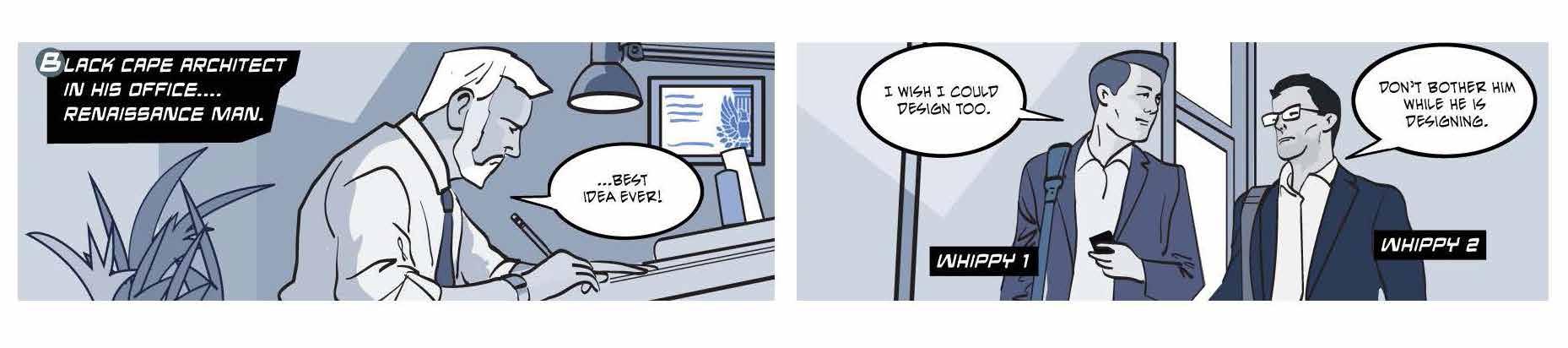

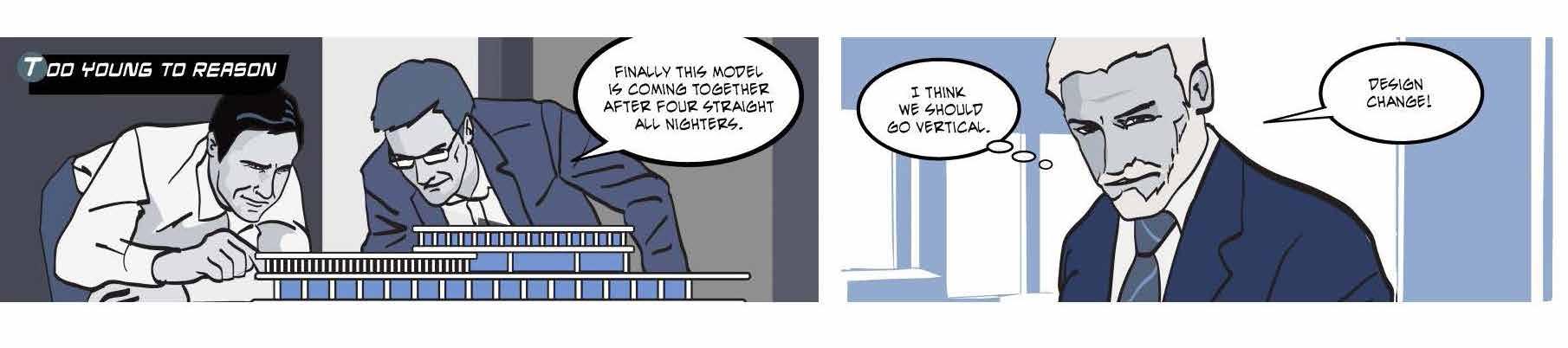

As we have no advertisements but are fans of this form of art direction and graphic design, we introduce you to “blurbs”—small moments of transition between content that offer notes of wisdom, sarcasm, and pop-culture sweetness. Inspired by CliffsNotes, created by a fellow husker Clifton Keith Hillegass, we have pored through TV, video, Google, and theoretical texts: like that kid who fished all the raisins out of the Raisin Bran or marshmallows out of the Lucky Charms box we have taken some of the work out of finding the “good stuff”. These little moments of reflection focus on Nebraska and design. They offer insight into how the world sees us (Nebraska – good and bad) and how designers/creative thinkers see their world.

On this auspicious occasion as you hold this first copy of Unicameral Design magazine, I am hopeful that this is the start of a new institution in our state’s design culture. We have never had a design magazine for our state and it is my sincere hope that Unicameral in its eccentricities of academic and commercial “hybridness” will become something of a standard for the designer class. We have worked to create a publication that looks to create a single body for all types of designers. That is why we chose the name Unicameral, not only is it an element unique to Nebraska as the only unicameral government in the United States, but it also established the idea that design is common in its process and application, regardless of the discipline that we each espouse to practice.

One challenge we have always had to overcome in Nebraska is population—or lack of it. Ranked 37th out of the 50 states, our entire population can fit in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. Because of this Nebraska, we have the need to become the fanboy, fangirl, fanperson to see our communities continue to demand progressive and inclusive design, for graphics, buildings, parks, environments, and spaces. We must create strong partnerships with artist, professional, and engineer alike. That mission begins with getting the word out to the world. Unicameral is intended to be the vessel to do just that.

8

9 Fall 2023 Unicameral Letter from the Editor

Photography: Dana Damewood. Reprinted with permission of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States.

Contributing Photographers

People & place photography was contributed by the following Nebraska photographers.

An old soul, an unplugged see-er, a soaker up of moments. I’m an outdoorsy explorer who nurtures a touch of wanderlust—while remaining deeply rooted in home. These passions are reflected and revealed in my work. I’m a professional image maker based in Omaha, Nebraska. My focus is capturing people, places, and spaces in real moments, in real time. I’ve honed my skills through my education in photojournalism, countless hours of practice and 15 years of business as a professional photographer.

I picked up my first camera at 16 and have not stopped taking pictures since. I started my formal education in high school and went on to finish a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Throughout my long career I have worked in all processes and mediums, film and digital. My work has been recognized in various national publications and platforms such as Bon Appetit, The Food Network, The Wall Street Journal, This Old House, National Parks Conservation Association, Culture Magazine, Preservation: Magazine for the National Historic Trust, Mother Earth Living, Country Living, Covey Rise, Cosmopolitan Magazine, Diabetes Magazine, Travel Kansa s and Country Woman. My personal work can be found in the following private collections: Aksarben Living, Bridges Trust, Peter Kiewit Foundation, UNMC, Scoular and at the Corvina Apartments. I am based out of Omaha, Nebraska, and split my time in Savannah, Georgia; Asheville, North Carolina; and other areas in the Southeast.

10

Colin Conces

Dana Damewood

Mad Cass is a multidisciplinary artist based in Lincoln, Nebraska. She primarily works within photography, poetry, artist books, painting, and drawing. In 2017 she earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in studio art with an emphasis in photography from the University of Nebraska. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally. Her book, How Lonely, To Be A Marsh, was featured at Fotobokfestival Oslo, and has been collected by institutions such as The Museum of Modern Art Library, The National Gallery of Art Library, The Getty Research Institute Library, and The Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s Hirsch Library. Her photography has been published in the following list of selected publications: The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and National Geographic

Dan Schwalm is an architectural photographer for HDR’s global architecture company based out of Omaha, Nebraska. He creates visually compelling images for projects ranging in size from 1,000 square feet to millions of square feet for both domestic and international HDR architects, interior designers, and other professionals to help tell their project stories. Dan was exposed to photography at a young age, with his father having a passion for photography. While initially interested in photographing skateboarding, Dan eventually transitioned into working as a photography assistant at HDR. This exposed him to a more diverse pool of subject matter and helped him realize his passion for architectural photography. Today, Dan’s work is featured in many publications, and he has helped HDR win an ever-increasing number of design awards.

11 Fall 2023 Unicameral Contributing Photographers

Mad(eline) Cass

Dan Schwalm

1 VY CAO

Growing up in a small town just south of Vietnam, at fourteen years of age, Vy moved to the United States. A high school teacher suggested that he could be a LEGO designer—one of his favorite mediums—and pursue an education in architecture. Completing his bachelor’s degree in 2021, Vy is pursuing a master’s degree in the College of Architecture, University of NebraskaLincoln. One of his primary goals is to design for LEGO and, more importantly, to make the world a better place than when he found it.

2 BRENDAN COLFORD

Brendan Colford is an associate editor for Unicameral Design magazine and a design coordinator at HDR Omaha. Brendan received a Bachelor of Science in Architecture and a minor in industrial product design at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He is now pursuing his Master of Architecture at the University of Washington in Seattle. When not at work, he spends his time camping, hiking, and rock climbing.

3 CAROLINE GOERTZ

A sixth-year master’s student in the Master of Architecture program, Caroline Goertz feels that architecture has always been the perfect creative outlet for her love of complex problem solving. Working on a design publication has been an exciting new way to flex those skills and develop a few new ones. Originally from New Jersey, she has chosen to make Lincoln her true home while working at Sinclair Hille Architects upon graduation. When she is not in school or at work, Caroline collects every experience the “little-big” town of Lincoln has to offer, weather that be a sporting event, open mic night, or adult volleyball league.

4 AUDREY HUSE

A graduate s tudent in the Master of Architecture program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Audrey finds the ever-challenging subjective nature of design a never-ending battle of personal growth. Inspired by her peers and individual experiences, her designs typically reflect her passion for balanced aesthetics, form exploration, and human interaction. Though newly pursuing journalistic expression, she has long wanted to follow this path that was once considered her backup plan from architecture.

5 LOUIS KHU

Originally from Omaha, Louis is a graduate architecture student at the University of NebraskaLincoln. He is also a first-generation college graduate in his family and holds a Bachelor of Science degree in architecture, anticipating his master’s degree in the Spring of 2024. As a member of the AIA and AIAS, Louis aspires to collaborate with designers nationwide to continuously innovate the standards of architecture and health. His hobbies include playing volleyball, drawing, and binge-watching his favorite shows.

6 BRIDGET KNUDTSON

Bridget is a design coordinator with HDR

Architecture and an associate editor of Unicameral Design magazine She earned her Bachelor of Science in design with high distinction from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 2022. Originally from Brookings, South Dakota, Bridget is passionate about design in the Great Plains and its surrounding regions. This fall, she plans to attend the University of Texas at Austin to pursue a Master of Architecture and certificate in historic preservation. In her free time, Bridget enjoys practicing yoga and watching movies with her cat, Binx.

12

Unicameral Staff 1 2 3 4 5 6

Unicameral staff, Fall Semester 2022.

7 MITCH NEUJAHR

Mitch is a Master of Architecture student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He grew up in Omaha and is in his final sixth-year study towards his master’s degree. He plans to dive into his architecture career as a designer at a local firm in Nebraska. His main interests are large-scale commercial projects and residential apartments. He hopes to provide thoughtful design to improve upon environment. Mitch’s passions include playing golf on the weekends and watching football with the boys.

8 JAY QUEMADO

Jay is a big vibe. The concept of “you only live once” is what he lives by and stands for because to be human you need to experience life to its fullest intent. A new soul trying to make his mark on the world, one step at a time—because you’ve got to start somewhere—he is an aspiring technical director and broadcast journalist, and strives to tell interesting stories to the world-at-large. Jay is currently a part of Nebraska Nightly, a COJMC news broadcast. He enjoys the everlasting concept of learning and prefers adventure and getting lost. He is a student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Journalism and Mass Communications.

9 EMILY SCHEIDLER

Emily Scheidler is a Colorado native from Colorado Springs. She is a junior at the University of Nebraska- Lincoln, and is a double major in journalism and advertising with an emphasis in public relations. Emily is passionate about being able to spread awareness for a variety of different topics including politics, the arts, and social justice. In her free time Emily enjoys analyzing movies and playing with her golden retriever, Homer.

10 TIFFANY N. SCHWEER, ASSOC. AIA

Tiffany is a project coordinator, architectural designer, and marketing assistant at arCuretecture in Lincoln, Nebraska. Born and raised in Clay Center, Nebraska, she moved to Lincoln to study architecture at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She graduated in 2021 with her Architectural Bachelor of Science in design with high distinction. As a young professional, Tiffany is a member of the Nebraska AIA. She has a passion for helping clients by using creative problem-solving to design beautiful and functional spaces.

11 ANASTASIA WAND

Anastasia is a first-year student in the two-year Master of Architecture program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She is originally from Woodstock, Illinois. For her undergraduate degree, she attended the University of WisconsinMilwaukee where she received a Bachelor of Science in architectural studies (BSAS). Her goal is to become a licensed architect and specialize in residential and hospitality design. Being a part of the Unicameral Design magazine staff has been an exciting opportunity for her to learn more about design in Nebraska.

12 MEAGAN WILLOUGHBY

Meagan Willoughby is a Master of Architecture student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She’s lived in Lincoln for over 15 years but spent her early life and summers in Montreal. Living in such different places created a curiosity about the different ways cities were designed, and combined with her love of drawing and science,this led her to architecture. She is passionate about bringing attention to and resolving inequalities perpetuated through design and encouraging diversity in designs and the design community.

Photography: © 2023 Madeline Cass 9 7 10 8 11 12 13 Fall 2023 Unicameral

Unicameral staff, Spring Semester 2023.

A building has at least two lives—the one imagined by its maker and the life it lives afterward—and they are never the same.

Rem Koolhaas, Dutch Architect, CO-Founder and Partner, OMA, Rotterdam

LOVE, ARETHA FRANKLIN, AND THE DEAD POETS SOCIETY

By Thomas J. Trenolone

18

LOVE . We want to be loved by our clients (cue your internal soundtrack—1975 song “Love Hurts,” by Nazareth: “Love hurts, Love scars, Love wounds…”). The difficulty is love comes with honesty, heartache, vulnerability, anger, and passion. It knows compromise and sometimes failure. Being liked is simply being cordial or kind; it lacks the commitment of love. Love from a client will see you through the difficult times that our profession is often defined by. Architecture, design, and the creation of great new environments and products is never easy (if it is, we are doing it wrong). Love comes with danger and risk; we often work diligently to remove these from the business. I believe truly great practices—ones that define long periods of time and improve the human condition— are loved.

ARETHA FRANKLIN, A.K.A. RESPECT. We want to be respected by our peers, our colleagues, and our communities (cue internal soundtrack—the 1967 song “Respect,” by the great Aretha Franklin: “What you need. Do you know I got it. All I’m askin’ is for a little respect when you come home…”) We want to be true to ourselves, to our values. I believe that it does not matter where you practice. I was once told that Omaha is where an architectural career goes to die. The type of work you do or the size of firm you run or practice with does not matter. If you are passionate about the work and its importance to our world and our communities, you will earn respect. Hopefully it will be in your lifetime, but I ultimately believe that, through this practice the path to it will come. Respect is often much like karma. Your attitude, knowledge, and commitment to the world of architecture, design, and interiors will define you and how your peers and clients perceive you. These perceptions—reinforced by your actions—will establish the foundations of a respected practice.

THE DEAD POETS SOCIETY. I have always believed that there is something special, even magical about what we do (cue internal soundtrack—1989 instrumental “Keating’s Triumph” by composer Maurice Jarre). A scene from the 1989 film Dead Poets Society has always stuck with me regarding this matter. In the scene, John Keating (Robin Williams) says to his students:

“We don’t read and write poetry because it is cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

(N. H. Kleinbaum)

I know it sounds self-important, but I have always wanted to place design in that quote. However, one day when I had become a little older and wiser, I realized that when it is done right, architecture and design inherits all these qualities. Architecture done well is poetry, beauty, romance, and love.

So, go forth and be loved and respected.

19 Fall 2023 Unicameral Essay: Love, Aretha Franklin, and the Dead Poets Society

Architecture, design and the creation of great new environments and products is never easy (if it is, we are doing it wrong).

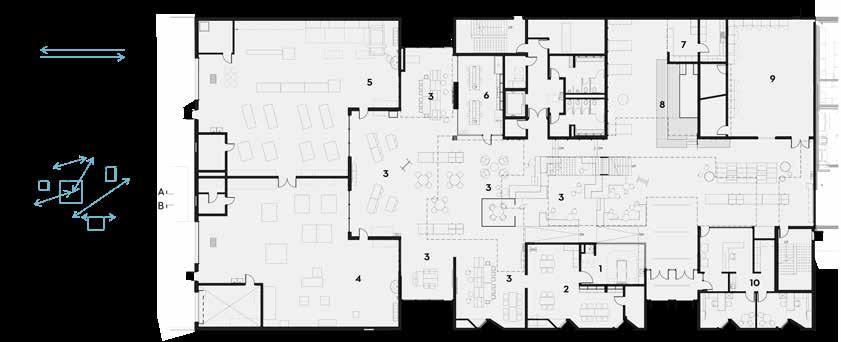

PLANNING & DESIGN

Entrepreneurial Studio

By Vy Cao

John Sova is managing principal of RDG Planning & Design. He has lived and worked in Nebraska his entire life. Graduating from the College of Architecture at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, John applied for a position through a newspaper advertisement and has since been with RDG. Starting out as a draftsperson and working his way up to become president of the firm, his journey has been a gratifying 41 years. Managing the business end requires constant and thoughtful attention but John makes sure to spend at least 20% of his time involved in projects, staying active in the design process, and participating in meetings with clients. RDG has nearly two hundred staff members located in Omaha, Des Moines, St. Louis, Denver, Dubuque, and Iowa City.

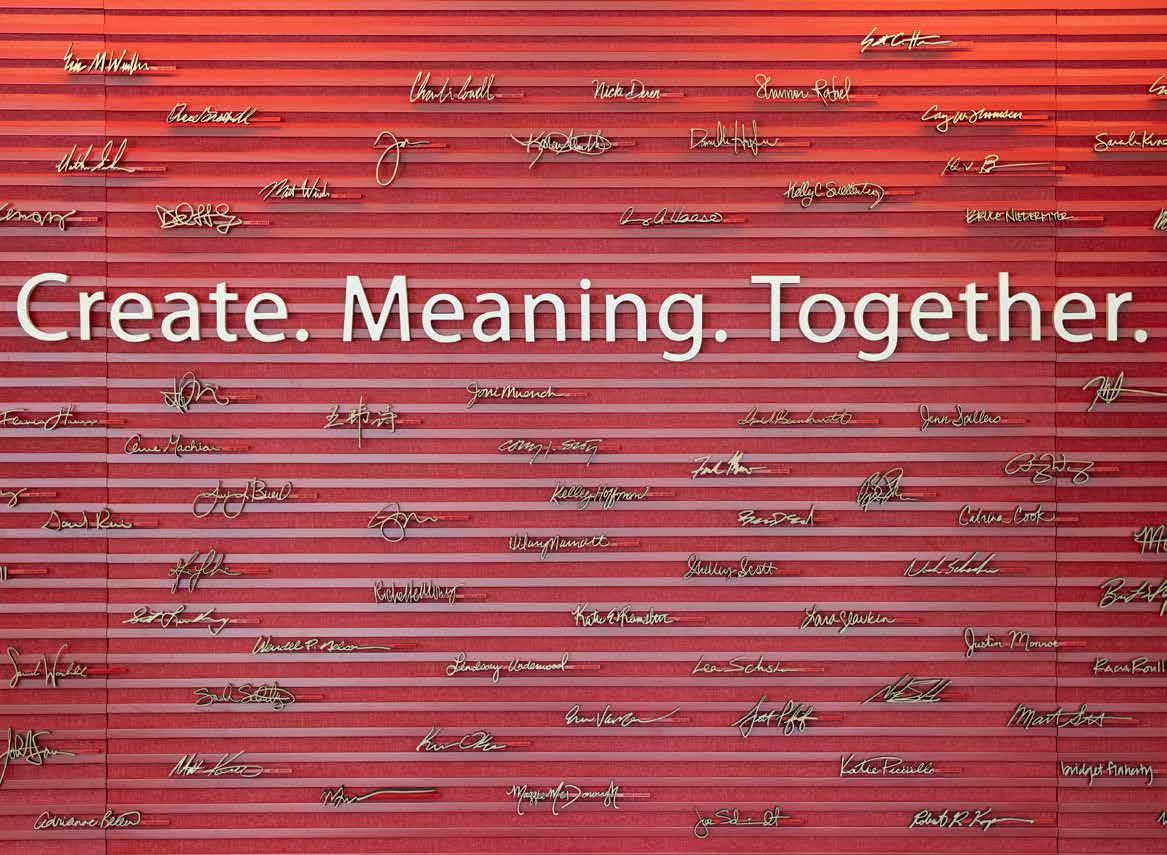

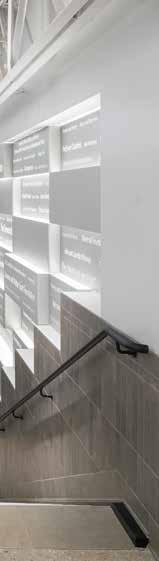

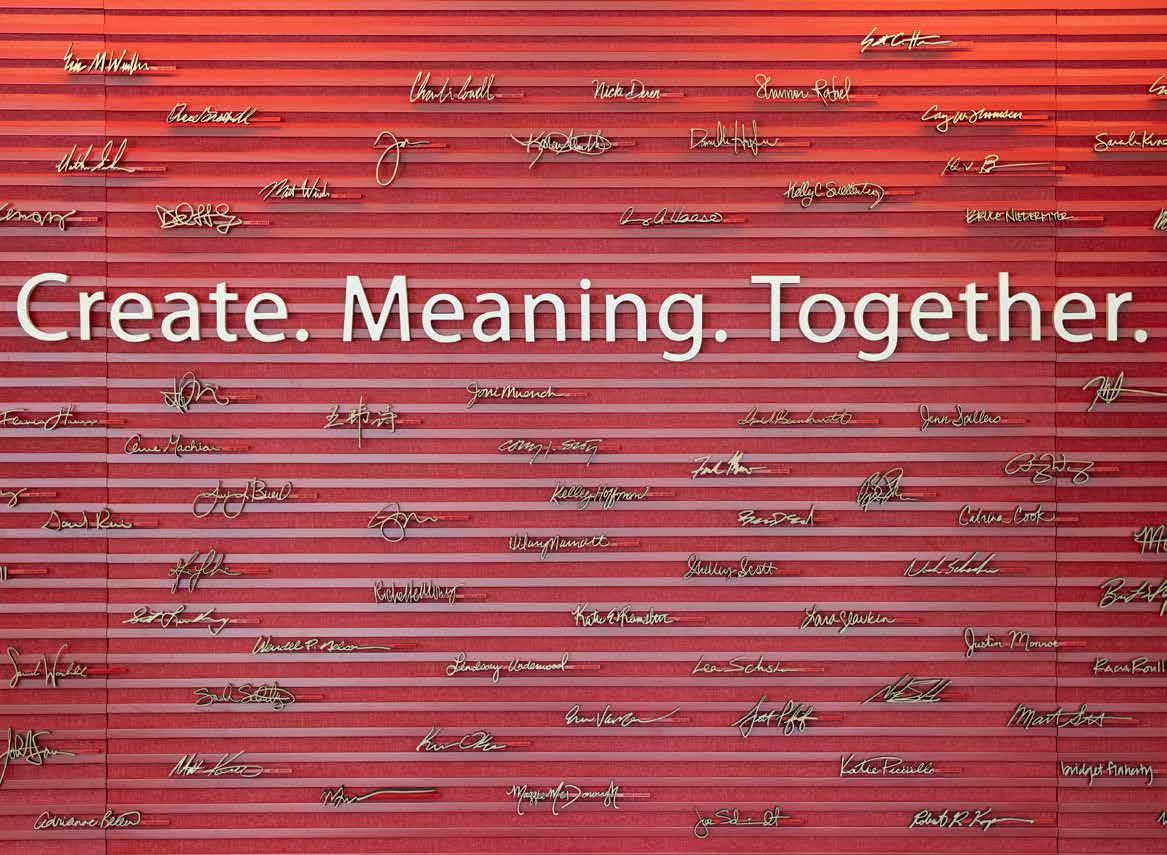

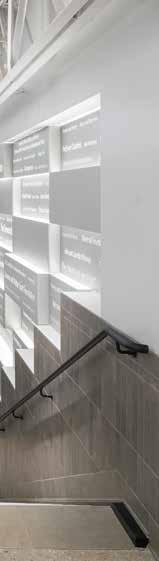

A core value at RDG is a strong culture of work-life balance with eight communities’ lifestyles. This allows their employees to have the opportunity to do a lot of things as John has been able to do in his career. As you walk into their office, the first thing you will see is a red installation displaying all the names of the staff. John explains that the wall is a reflection of their mission, to create meaning together with each other and with their clients.

Responsiveness to clients’ needs is of the highest priority, not simply to give the clients what they want, but also to challenge them to think outside of the box. Clear client communication is critical, making sure that clients understand the project scope and that designers understand their clients’ needs and expectations. Providing design solutions to unforeseen issues is a key factor in building trust and continuing relations with their clients.

Having a diverse client base and wide-ranging project types, the aesthetics of RDG’s style adapts to the uniqueness of each scope. The Omaha office is staffed with visual designers specializing in the creation of three-dimensional renderings, in addition to project models that enable the client to experience the spatial qualities by video. A virtual walk-through with the client has become a critical part of their communication and is vital to the success of each project.

Benjamin Kroll has been with RDG since 2015. After living and working in New York for over a decade, Kroll was ready for a change. What stood out to him about RDG was the culture. RDG takes a holistic approach to working with their clients and the way they manage their employees. They employ eight “Lifestyles” that provide a foundation for their company’s culture: Design, Learning, Healthy, Sustainability, Community, Technology, Fun, and Leadership. The by-product of the culture at RDG is a strong entrepreneurial spirit; staff are not only allowed, but encouraged to pursue their passions and find ways to integrate those passions in their workplace. Kroll explains that this strong entrepreneurial spirit sets RDG apart and allows people to excel because they get to implement their passions into their work and into their projects.

20

RDG

John Sova and Hilary Navratil, interior designer for the Omaha Office Central Stairs.

21

Above

and at right; First National Bank designers Benjamin Kroll, Bob Krupa and Gina Lorkovic. Photography: © 2023 Lea Schuster, Colin Conces Photography

22

Photography: © 2023

Dan Schwalm

The Road to RDG

By Bridget Knudtson

Both Bruce Niedermyer and Kene Okigbo exemplify the eight RDG lifestyles outlined on the firm’s culture wall. Niedermyer, a partner of the firm and Okigbo’s senior, is pragmatic and encouraging. Okigbo, a young designer with a passion for diversity, freely admits that the RDG lifestyle he most relates to is “fun.” Together, the two landscape architects lead with a laid-back and can-do attitude.

Okigbo considered a variety of majors before settling on a landscape architecture degree from North Dakota State University. The design market in Fargo was sparse at the time of Okigbo’s college graduation, so he took several jobs to make ends meet. “If you look at my resume,” he said, “there’s a period of continuous change.” That experience paid off when he landed a position with a landscape firm in Omaha. After gaining a year of experience, he transferred to RDG and has now been with them for four years.

Niedermyer took a more straightforward path in his education, graduating in 2011 from Iowa State University (“Let the record show that everybody groaned,” Okigbo noted). As a first-year student, Niedermyer was pre-architecture but made the switch to landscape after a convincing presentation from a professor in the program. After graduating, he hoped to work with an individual he had met from RDG but the firm didn’t have any openings at the time. Accepting another opportunity, he travelled halfway across the country to Alexandria, Virgina. “Six to nine months later, RDG called and said, ‘we’re hiring.’” Niedermyer jumped at the chance to interview and was immediately hired by the Des Moines office. After five years, he transferred to the office in Omaha.

One thing that sets RDG apart is its emphasis on urban planning and landscape architecture. In fact, it’s right there in the name: RDG Planning & Design. I asked Okigbo and Niedermyer about their thoughts on this. “[Landscape Architecture] is not the leading revenue source for the firm by any means, but the number of projects that we lead and have a large stake in is very robust,” said Niedermyer. Okigbo and Niedermyer are both in the urban design market. That market is housed under RDG’s community studio, which involves mostly landscape architects and planners. “I think that's an important point that within the community studio, there's a lot of collaboration between planning and landscape.” Collaboration is a key theme at RDG, and landscape architects hold a very significant position. As Okigbo said, “Including landscape architects early in the conversation during the planning and design of a project will provide a more complete experience.”

RDG’s dedication to inclusion of multiple disciplines is part of what secures great employees like Niedermyer and Okigbo. In 2021, their team was recognized with three awards by the Nebraska/Dakotas Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) for their work in the Midwest and surrounding regions. The three projects— the Casper Wayfinding Plan, New North Makerhood, and La Vista Civic Space—encapsulate a wide range of contexts and scales that the team works successfully within.

23 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

Above; Bruce Niedermyer (right) and Kene Okigbo (left) interviewed by Bridget Knudtson.

24

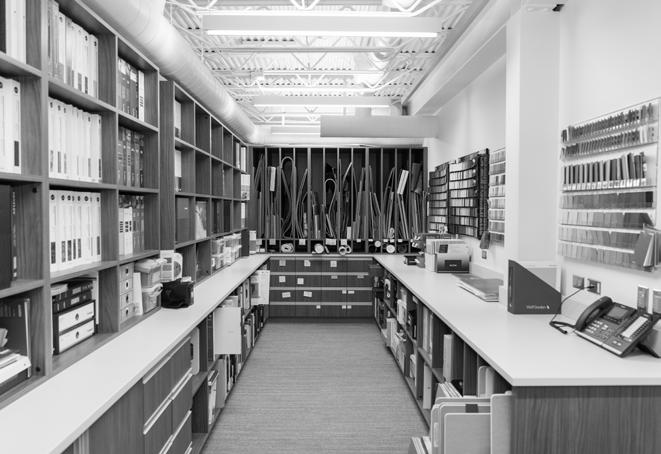

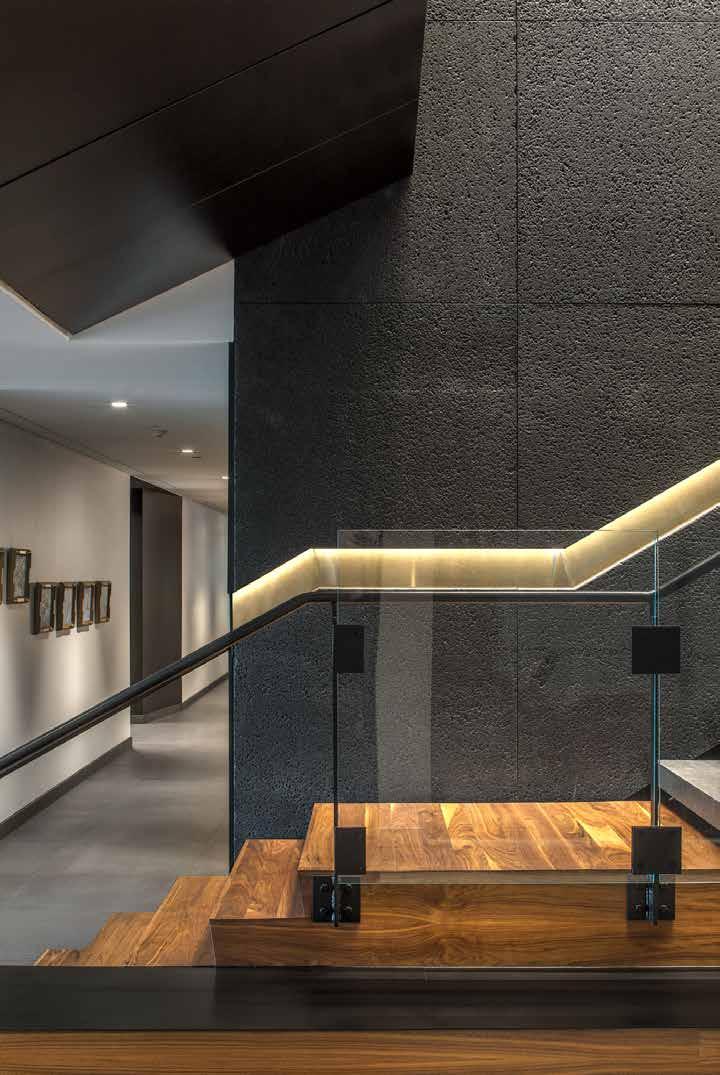

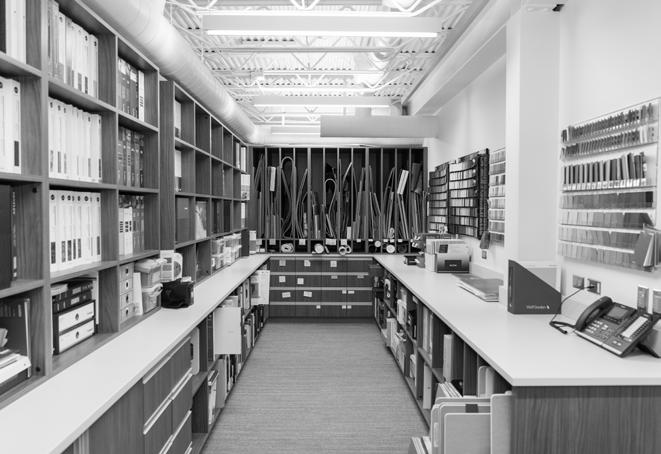

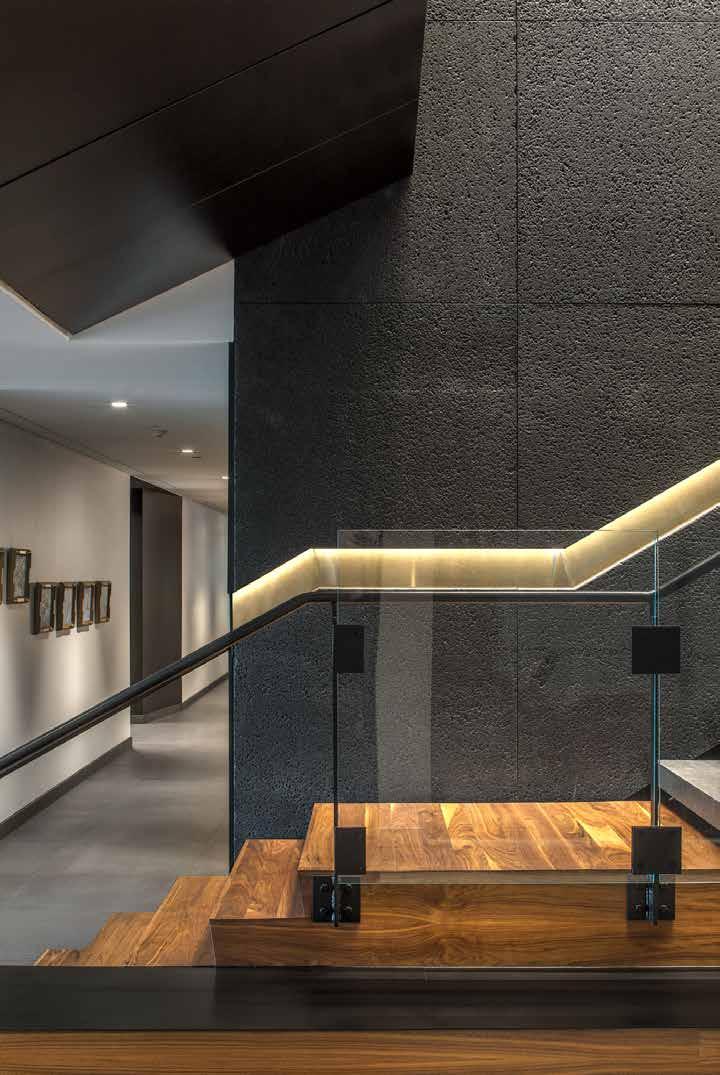

OMAHA OFFICE CENTRAL STAIRS

A Natural Connection

By Vy Cao

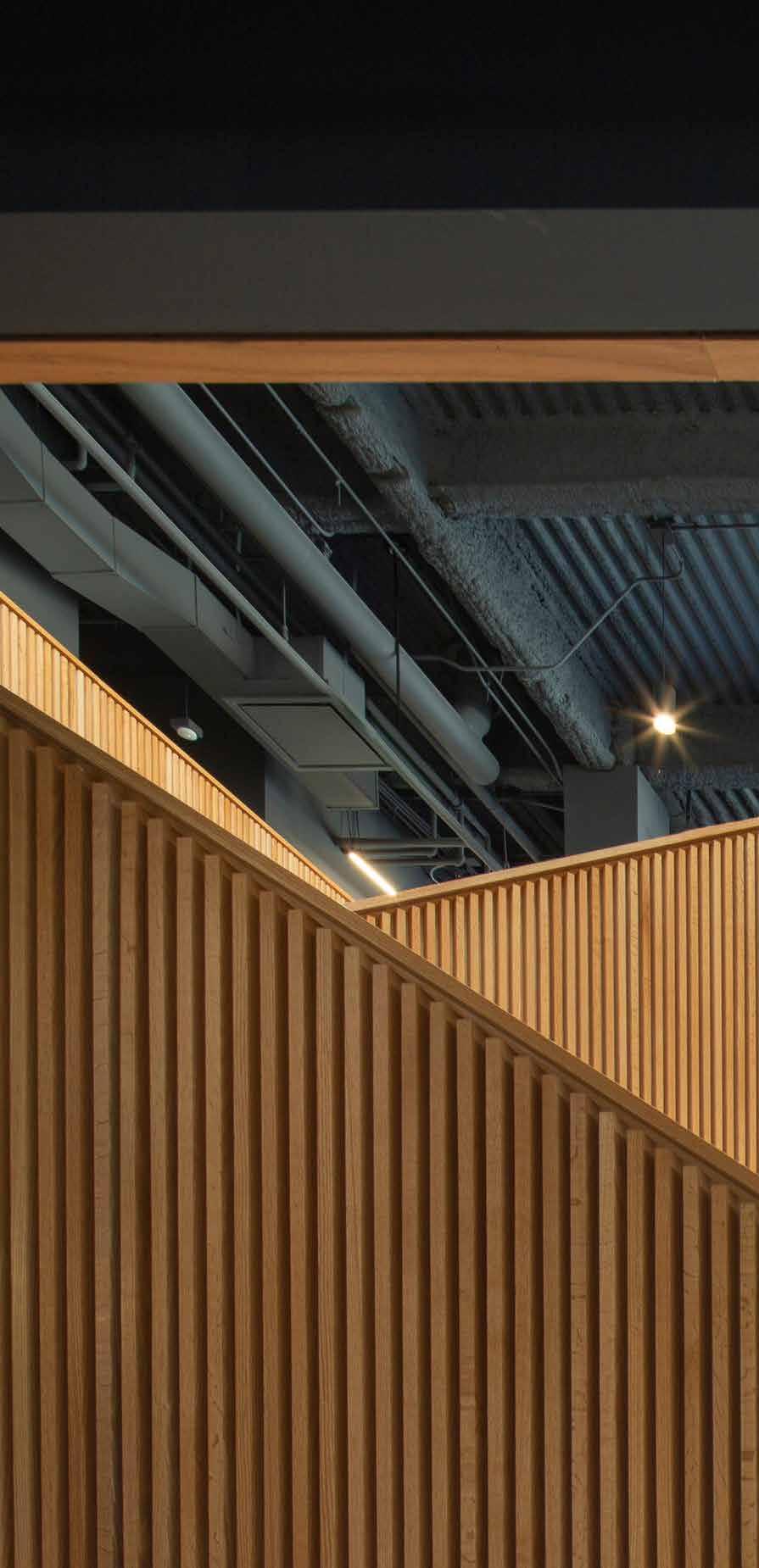

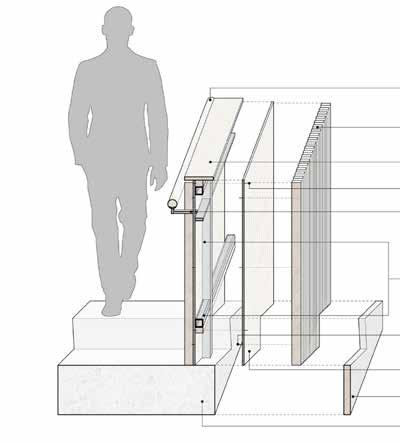

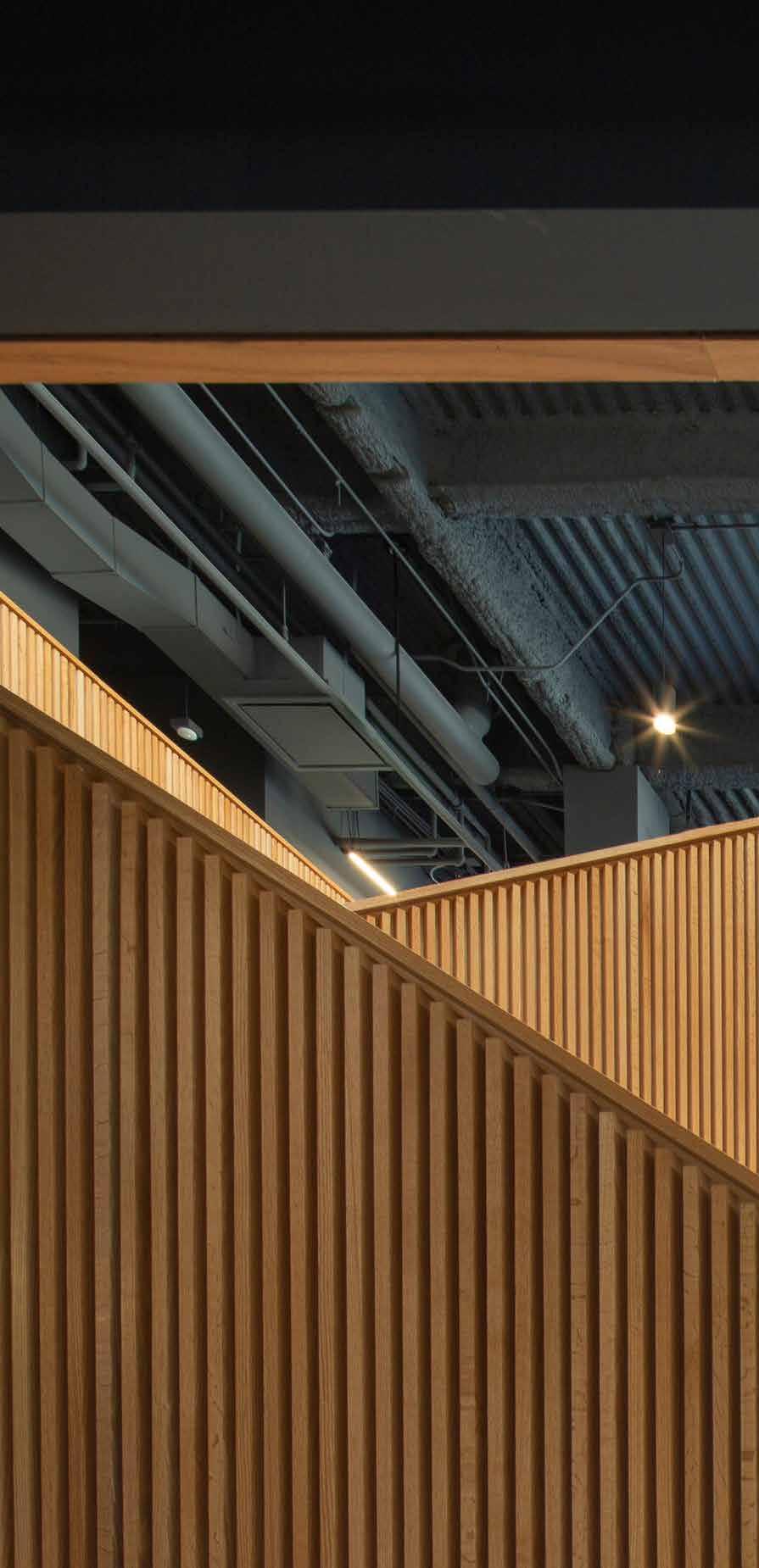

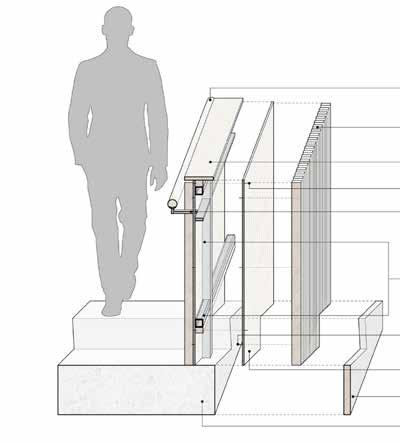

The renovation of the Omaha stairs was a design decision to create a focal point in the office. Part of the Chamber of Commerce for the last 35 years, the stairwell is integral to everyone’s day-to-day workflow. The stairs are shaped like circular sectors, a wide entrance leading to a narrow landing then widening again at exit. The uniqueness of this architectural detail is the highlight of the office interior.

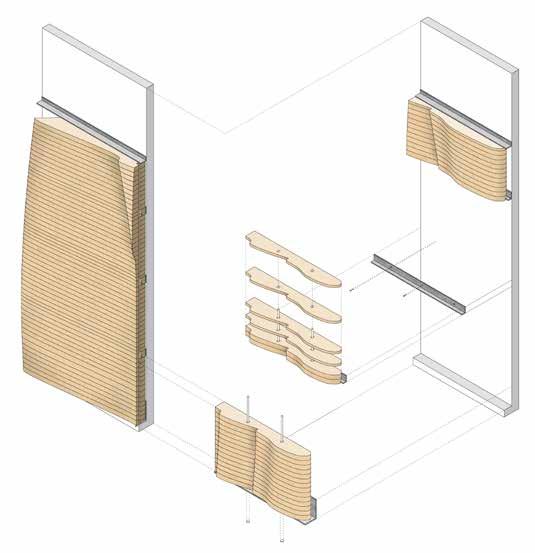

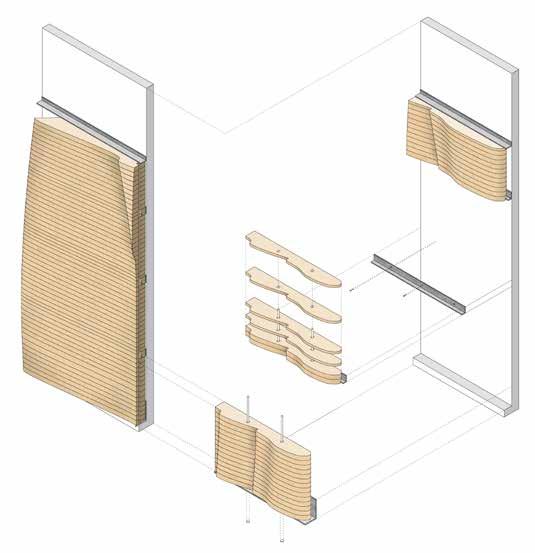

Originally, RDG wanted to take the carpet and walls off, and the stairs were supposed to be exposed concrete stairs to fit with the simplicity of the renovation. When the design team visited the site, they noticed there was a significant amount of wood from the original design’s door jams, window frames, and millwork. Thus, the design team decided to reuse as much of the material as possible. They found a carpenter who loved the idea, so it turned into a design-build project. The team spent three months planing down the wood planks to wrap around the stairs. In the end, about 80% of the wood on the stairs was recycled.

RDG started the project with no grand vision because of the design-build nature of the project, they were more concerned about how to recycle, and process the wood into the right dimensions with the carpenter. Though there were no expectations for the stairs—except to minimize the waste from the original design—the result is a resilient focal piece to the space that is beautifully detailed.

25 RDG Planning & Design

1.25″ Oak handrail

1 x 2″ Refurbished and hand-milled oak slats

Recycled oak cap

Hidden panel fastener

Steel handrail bracket

Existing steel guardrail

Hidden wood slat fastener

0.25″ Fastening panel

Refurbished oak fascia

Existing concrete stairs

26

27 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

Financial Strata

by Tiffany Schweer

First National Bank of Omaha (FNBO) has been a client of RDG’s for many years. What is unique about FNBO is that they are the largest privately owned bank in the country. As the front page of their website states, “We’re more than a bank. We’re a neighbor you can count on.” FNBO primarily focuses on independent banking, and the result of this, along with their mission, is a level of authenticity as an institution that customers can trust with their money. FNBO makes a point to be involved in the communities they serve, and even though they are a large company, there is a level of intimacy that inherently comes hand-in-hand with their business model.

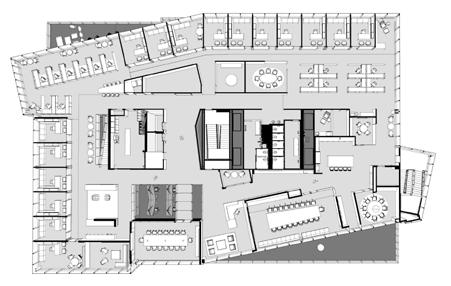

It is important to understand their mission when looking at this project and their other branches. FNBO’s mission and values translate directly to the physicality and intent of their spaces. The intimacy and friendliness in their interactions between the banker and the customer directly tie to the functionality of their branches, the Colorado State University (CSU) branch in particular.

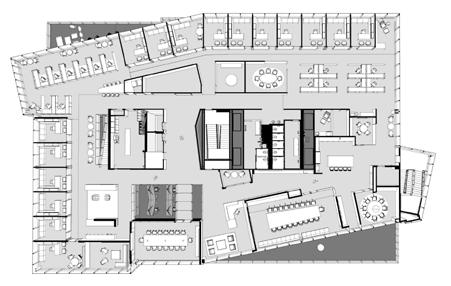

28 FIRST NATIONAL BANK, CSU

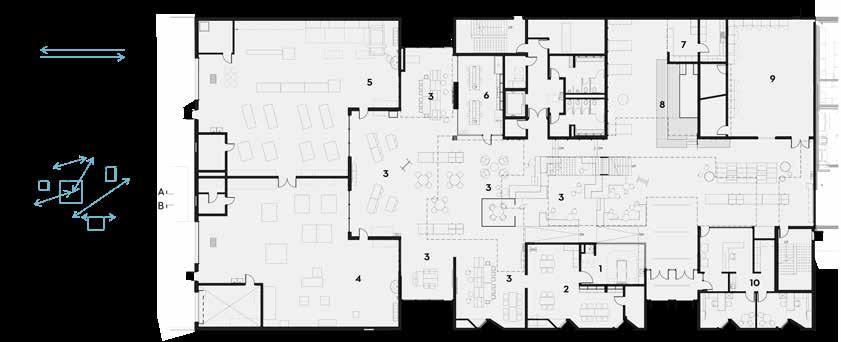

FLOOR PLAN

Photography: © 2023 Thomas Grady

29 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

Although RDG has done many projects for FNBO and has a good understanding of their mission and goals, like any project the design process begins with listening. Kroll explains that the best projects come out of the passion and vision of the client, taking that information and applying the architectural principles that come out of that vision. The design team focuses on the storytelling opportunities, by defining linguistic terms to solve the design challenges at hand. Kroll describes how their design process starts with linguistics, with thought, rather than with imagery. By removing the imagery, RDG can focus on designing a solution that the client can take unique ownership of—because really, they are either helping the owner determine the design challenge, or they are regurgitating the owner’s defined challenge back to them through architectural concepts and principles. After the linguistic storytelling phase is complete, the design team begins researching the site, followed by massing and iterative design.

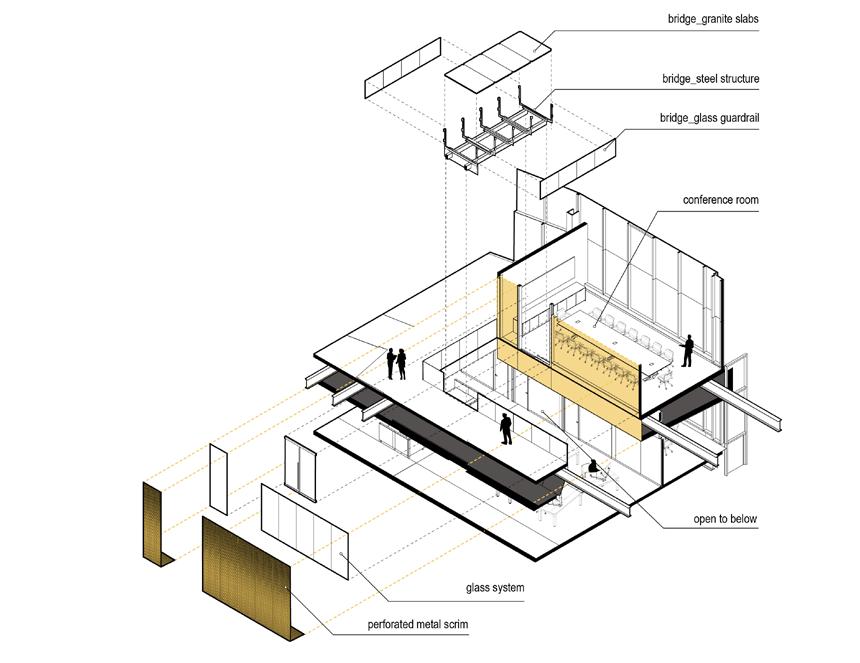

EXPLODED AXONOMETRIC 30

The biggest challenge of this project was square footage. The CSU branch’s previous space was 3,400 square feet. The new space was less than half of that, yet Kroll’s team still had to fit all of the same program elements into a significantly smaller space. RDG worked closely with the client, to really dive deep and think about the transactional experience between the banker and their clients, how can they provide the same (or better) experience in such a small space, while simultaneously expanding the branch’s presence on campus. The client wanted to “expand their footprint” on campus by providing a sense of openness and welcome that invites clients in.

RDG’s design team employed several design elements that helped to achieve these goals and address this challenge. The new individual offices in the branch are smaller, but because the wall partitions are all comprised of clear glazing, the office spaces feel larger than they are. Retractable glass walls that pocket back into the walls completely open up the corner of the space to the corridor, blurring the line between a main

circulation path in the building and the FNBO’s space. The wrapping of materials on the exterior and the way the wood flows into a bench out in the hallway helps make the bank feel like it is expanded out into the corridor environment.

The parametric sculptural wall fabricated in wood attracts passersby to reach out and touch the wall as they stroll by. It creates a tactile experience that helps draw people in. The wavy wood design is a nod to the natural environment of Colorado but does so in a way that is not only unique, but also functional. The undulations, the pushing and pulling of the material, naturally create programmatic functions, such as the check-writing table and a wheelchair-height table, seamlessly blend into the design of the front desk. Something Kroll strives to do in his designs is to make sure to give the design element multiple programs. This not only provides a bigger return on the investment and bigger impact to the users but helps tie the whole space together.

31

RDG’s design concept for the CSU branch became a reality after teaming with Polynomial, an interdisciplinary fabrication and design shop collaborating with designers, architects, and contractors on unique and daring projects. Polynomial has a keen eye for details, and they are industry experts when it comes to constructability and the installation of all sorts of projects like the First National Bank, CSU. Polynomial was quickly able to take RDG’s design, run budget numbers, and help refine the design based on their knowledge of machinery capabilities, and design details like the routing on this project that helped take it to another level of craftsmanship. Polynomial worked with RDG

and the client to design and construct the project in a way that it could be fabricated in pieces in their studio, and then transported to Fort Collins, Colorado where it would need to fit through the doors of the existing building and be pieced together on-site.

One of the greatest challenges for designers across all industries is convincing a client to have trust in the expertise of the designer. Sometimes designers and clients don’t always see eye-to-eye, and at the end of the day, clients will choose to do what’s right for them—after all, it is their project and the space has to ultimately serve their purpose. Right or wrong, as the designer you can only do so much. This project was one of those

32

cases. The professional photos of the project showcase completely clear glazing surrounding the exterior of the space, however users don’t quite get that same experience: the owner has since completely frosted over all the clear glass walls in order to provide more privacy and added oversized logo graphics across the glass, including a huge FNBO logo and a giant ram, the mascot of CSU.

Although the owner’s modifications might hinder the design intent, the overall program successfully aligns with the student union at CSU. The same natural, oak-colored wood finish with forest green accents (both FNBO’s and CSU’s primary color) is scattered throughout the student

union building, some of which are new additions since the FNBO installment. This cohesive element unifies the wide-variety of programs found under one roof, from the coffee shop to the welcome desk, and even to the open lounge space where students hang out and study between lunch and afternoon classes. This level of cohesiveness not only adds to the school spirit in the primary student hub on campus, but directly ties FNBO to the CSU community accomplishing the client’s vision.

33 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

THE NEW NORTH MAKERHOOD

Artists In Residence

By Bridget Knudtson

By Bridget Knudtson

34

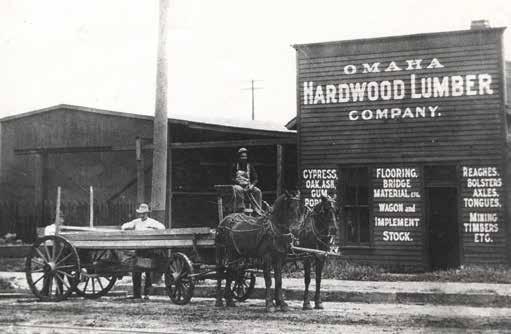

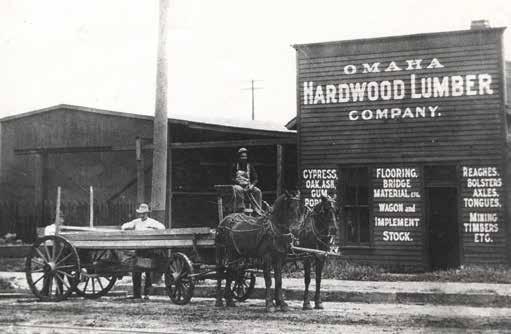

The New North Makerhood space is situated at the site of the former Omaha Hardwood Lumber Company. During its industrial past, the place was a thriving lumber mill with a busy railroad line running directly through its warehouses. Now, the site sits derelict, despite its proximity to the Missouri River and Omaha downtown core. Future Forward, an Omaha non-profit, plans to change this. They have partnered with RDG to create a master plan that imagines what the space could one day become. The New North Makerhood transforms the site of the old lumber mill into a haven for artists and a cultural hub for the Omaha community.

RDG brought a unique vision to this project having its own in-house art studio. Artists from the Iowa-based art studio and Omaha-based landscape architects and interior designers all worked in close collaboration to develop this high-level plan for the Makerhood. Future Forward wanted to ensure that studios for Nebraska artists have an economical approach so the RDG team kept their interventions minimal. “There was a lot of visual listening , we'll call it, of other industrial renovated sites that keep that grit and charm that's associated with the history of its site,” Bruce Niedermyer, project champion, said of their inspiration. Taking cues from the site itself, specifically its logging history, they decided to keep the existing rail tracks running through the site and use them as the main corridor for circulation. The concept is strong and provides visitors with several spatial experiences with direct access to the proposed artists’ studios.

35 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

36

In order to facilitate pedestrians crossing through parking lots and into the site, RDG’s team had to design physical dividers to denote spaces not accessible by vehicles. They did so by creating stacked towers of logs, another nod to the site’s past. As it is currently, the partitions do not provide much separation from the street, which may prevent the space from beign used safely and comfortably. Incorporating the site’s logging history by creating a green screen or a canopy to enclose the pedestrian space could create opportunity for a more elegant integration of this crucial moment within the site’s history while also providing much needed shade currently lacking within the space. Another feature, a small park at the beginning of the complex, experiences the same problems. Called “River Meander Park,” this space pays homage to the Missouri River and its role in the logging industry. The team at RDG has plans for several fountains and seating areas, but the design has potential to be pushed futher. In the future, when the project is realized, this park can become a fun and interesting landscape for family recreation. Some small changes in grade, more water features, and strategic foliage could help bring this design to life.

A notable feature sure to be a highlight is the incorporation of public art throughout the site. RDG proposed the installation of vibrant murals with the addition of sculptural pieces strategically placed to hide mechanical and electrical boxes. Due to a limited budget, much of RDG’s proposal focuses on how to repurpose

37 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

existing materials into new and useful objects like planters, benches, and lighting. “There's not a large budget for new improvements, the main goal is to create spaces accessible to artists. It's intended to respect the history of the site and make sure it doesn't change the vernacular,” said Bruce. RDG’s masterplan provides many opportunities for local artists to make their mark on the space and showcase their work. The eye-catching murals will hopefully bring visitors further in to explore the site.

At the heart of the Makerhood is a large plaza which will provide several opportunities for engagement between artists and the community. This area will become an adaptable space for community events like art fairs, musical performances, and farmer’s markets. To help facilitate these events, the space includes a stage, stepped seating, and a special pavement design. The concrete patio is offset with a line of dark brick tiles at 10-foot intervals providing the perimeters for the installation of tents or tables. The space will help bring people into East Omaha and boost the economy of a oncederelict district. The timeline has not yet been solidified for the start and completion of Makerhood. Currently, Future Forward is prioritizing its funding. Regardless of the site’s challenges, RDG hopes to see the project realized. The New North Makerhood site could potentially add an energetic venue for the creative community in the city of Omaha.

38

39 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

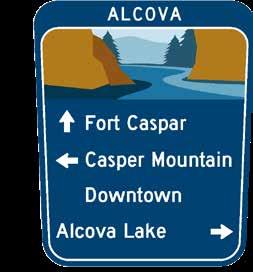

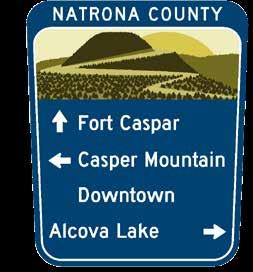

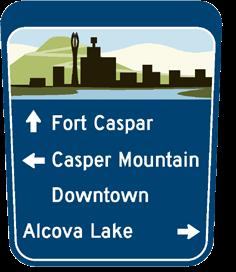

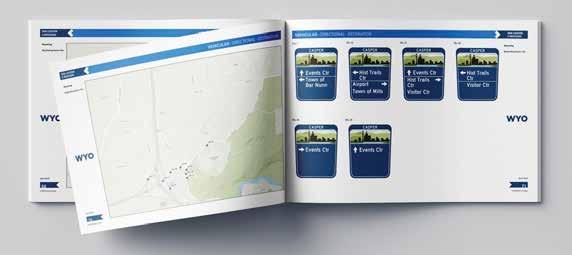

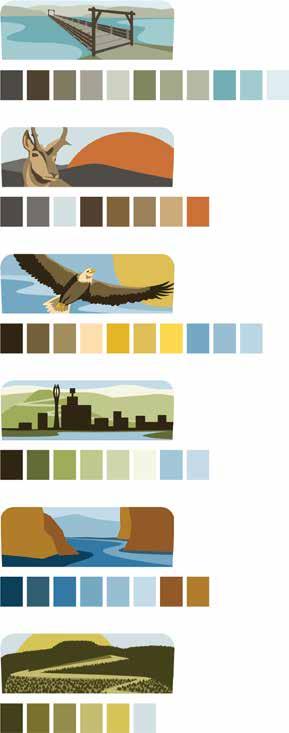

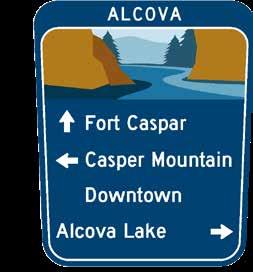

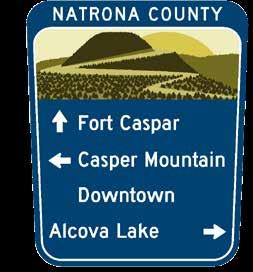

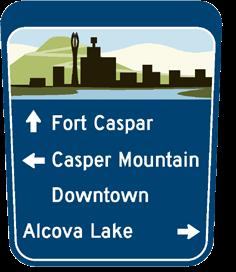

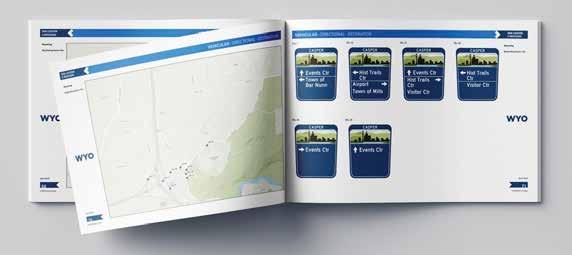

CASPER WAYFINDING MASTER PLAN

40

By Bridget Knudtson

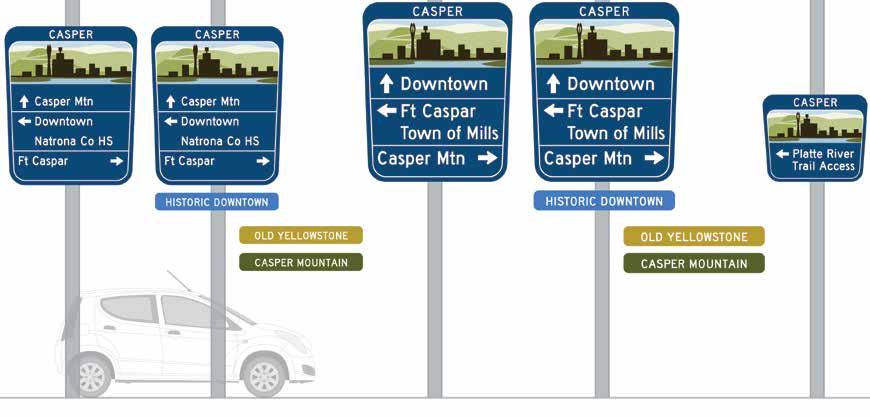

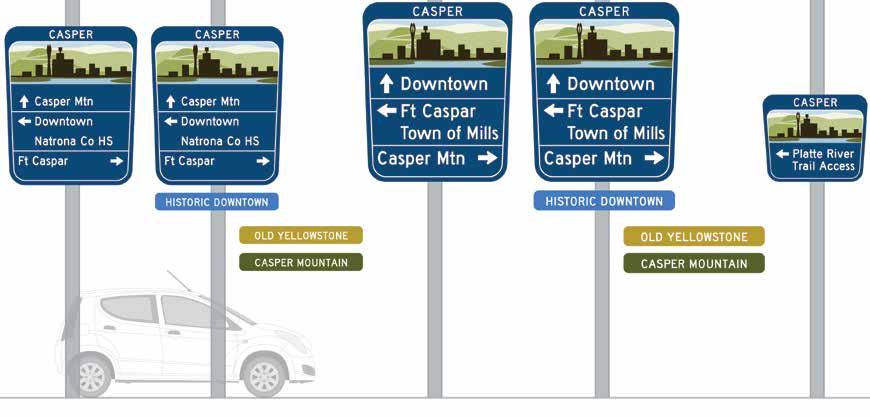

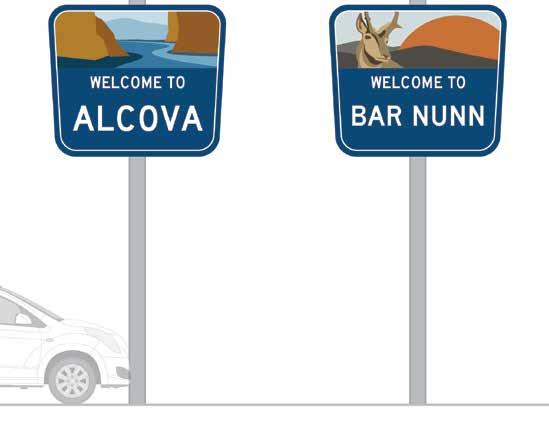

The Casper Wayfinding Master Plan was a team effort between RDG’s landscape architects, environmental graphic designers, and community planners to develop a unified signage and wayfinding standard for the county, cities, and towns within the Casper area in Wyoming.

Leading the team was landscape architect, Ryan Peterson, based in Madison, Wisconsin. The Casper Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) was looking for guidance in creating and implementing a wayfinding system for residents and tourists to their jurisdiction. With the help of Natrona County residents and Casper MPO, RDG devised a detailed plan for the design and placement of over 200 signs throughout the community. They also gathered extensive GIS data to aid Casper MPO in carrying out the implementation and maintenance of the new wayfinding system.

“The primary challenge was in providing clear directions to key destinations. How do we help people navigate our streets?” says landscape artchitect, Kene Okigbo. He agrees that it is not standard practice for landscape architects to drive the design approach for a signage and wayfinding project: nevertheless they are an important asset to the multidisciplinary team in design development. “Making something that worked for all of these different jurisdictions, both in aesthetics, function, and cost, was going to be huge because Evansville compared to

41 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

Casper are drastically different size communities with drastically different budgets.”

The team relied on public engagement to determine what was most valued by each community within the client’s jurisdiction. Determining areas that receive heavy traffic, Casper Mountain was identified as the premier destination for tourists. Prioritizing by location, RDG submitted specifications for over

200 vehicular signs for Natrona County. The effort involved combining huge amounts of data both received from Casper MPO and generated by RDG’s GIS specialists. This included data on traffic flow, road speeds, and the coordinates of each location. The final deliverable for the project was a GIS database comprising completed information and location of every sign.

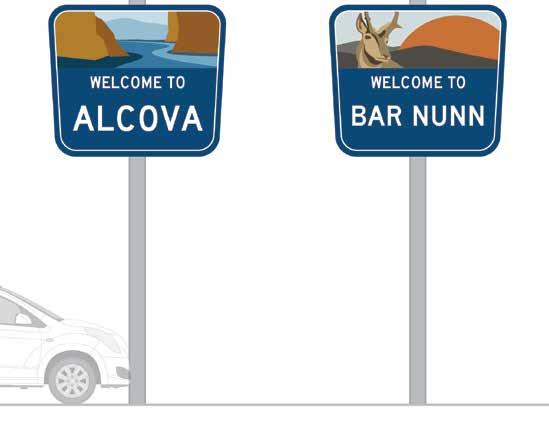

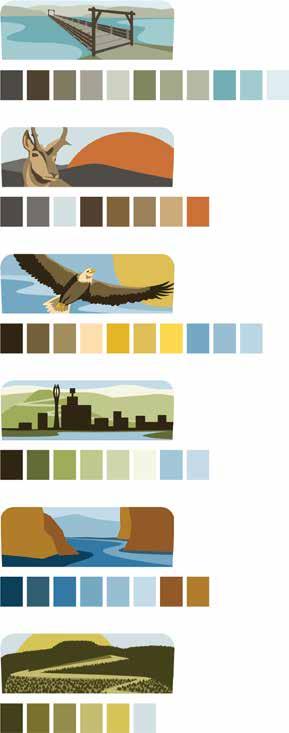

In-depth studies of iconography representing each community was tasked to the graphics team. “While visiting the project site, we prioritized exploration of the environment, noting flora, fauna, and everything in between, these facets represent what is important for our community,” says Okigbo. Each community was assigned a unique image and color palette to symbolize that jurisdiction. The town of Casper is symbolized by its iconic skyline, the Waterways region by an

image of the North Platte River, and the town of Bar Nunn a native pronghorn. Bar Nunn was another instance where public engagement proved invaluable. Where Main Street was once an old landing strip, an aircraft seemed the logical choice for iconography. That was not the case, as the residents of Bar Nunn felt little connection to their aviation history and instead opted to choose the beloved Nebraskan wildlife: the pronghorn.

42

As a final exercise, Casper MPO asked RDG to provide several options for gateways into the community. Okigbo and his team proposed designs aligned with the existing style of the architecture and materials in Casper. The town is phasing RDG’s wayfinding standards into new construction projects. Rather than replacing all the

signs in their jurisdiction at once, they are updating signs and markers as new construction projects begin. The local community anticipates that the signage and wayfinding system will help establish a positive identity for Casper, providing an enjoyable experience for tourists to discover their beautiful environment.

43 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

LA VISTA CIVIC SPACE

A Spotlight on Community

By Bridget Knudtson

44

La Vista Civic Space, dubbed the “Interface,” provides a new cultural hub for the community and connects La Vista’s City Centre to Central Park. RDG has a long history with the city and has been a part of a decades-long process to develop La Vista’s central core. Their first project in La Vista was a master plan turning a par 3 golf course into Central Park in 2011. Now that the park is complete and the city’s core is on the rise, the landscape architects at RDG were hired to merge the two projects into a nexus for art and culture. With 38 feet of vertical grade change, an indoor/outdoor music venue, and a sensitive wetland to work around, the effort was no small feat, but the team at RDG once again delivered. Though the work was gained through an RFP, it was RDG’s familiarity with the community and diversity of skills that set them apart. Oftentimes in the world of planning, the firm that does the initial master plan is not the same group that designs and constructs the project. “You’re setting it up for somebody else to dunk,” explains Okigbo. But RDG Planning & Design has a secret weapon that many groups lack, and it says so right in their name. Bruce Niedermyer adds, “I think what helps us be successful in those pursuits is showcasing exactly what Kene is describing: our ability to take a project from early planning through implementation, whether we have the invitation or not, it doesn’t necessarily matter.” RDG has a strong focus both in the worlds of planning and in architecture and design. The firm employs a diverse group of professionals who excel in their respective fields but are also able to navigate the overlaps between the two disciplines. This trait allows RDG to take on projects like the Interface and see them to completion.

45 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

46

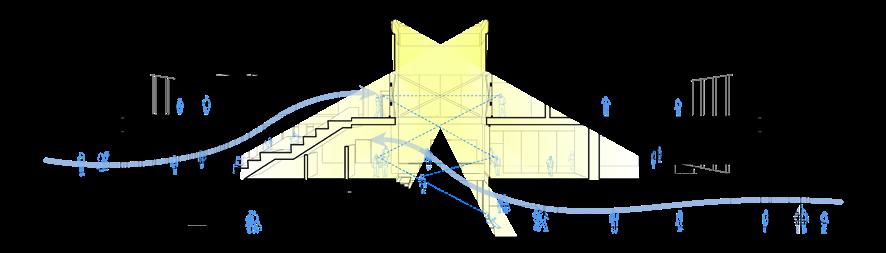

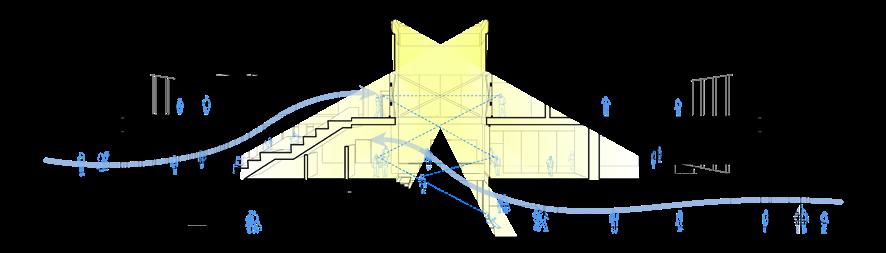

The Interface involved a crossover of multiple disciplines including landscape architects, architects, engineers, artists, and urban planners. The team had three goals for the space: to converge people into the space; build energy around it; and amplify that out into the community. At the center of the project will be a new indoor/ outdoor music venue, designed by a separate firm. This venue provided key inspiration for the Interface. “This angularity of a spotlight was big from early on, shaping how these spaces get created, and how they relate to one another.” Niedermyer says, “And so we ended up with multiple zones in the overall design, but each one is kind of informed by that iconography.” The first zone, City Centre Commons, provides a front door to the downtown and welcomes visitors into and around the music venue. The angularity of the design aids in this process. The team wanted to enhance the design of the music venue, while also keeping in mind that the form will change as work moves forward. Carefully placed landforms, benches, and water features compliment the angles of the venue, while providing much needed shelter from the street and the elements.

The second of the three zones RDG created is La Vista Landing. Located northwest of the music venue, the landing accounts for 27 of 38 feet of grade change. A grand staircase and ramping system are carefully carved into the hillside to safely get visitors down to the level of the park. This zone includes colorful seating, play equipment, and

picnic tables which point to La Vista’s past. “La Vista was first established as a bedroom community and people, when they first moved there, didn’t know anybody. So they would have these community dinners where all their neighbors would come together, potluck-style and just get to know one another.” From this came the idea of the Community Table which Niedermyer and his team wanted to implement in the final scheme.

To the east of the landing is the true star of the entire design: a pavilion connecting with the music venue and overlooking Central Park Pond. The form of the pavilion again embraces the spotlight iconography with elegant, angled roof structures that provide shade and directionality for the whole complex. This building was done in collaboration with RDG architects and lighting designers to give the right feel to such a monumental structure adjacent to an idyllic park. Geometric planters along the edge of the overlook blend the building into its context and move visitors to the final zone of the design. The final zone, Water’s Edge Terrace, expands the usable park space and offers cohesion with the pavilion and overlook. The terrace is suspended above the lake in order to maintain usability during a storm event in which the park’s retention pond can fluctuate up to ten feet higher than normal.

Finally under construction, the building’s strong angular iconography remains intact. The Interface is a triumph by landscape architects, Niedermyer and Okigbo in collaboration with RDG’s multidisciplinary team.

47 Fall 2023 Unicameral RDG Planning & Design

48

49

SPLIT OR STEAL

By Brendan Colford

The Architects Dilemma: Split or Steal is a thought experiment based on a game theory concept called the Prisoner’s Dilemma, created in 1950 by Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher.

50

The experiment goes like this: two participants are presented with a large sum of money. Each participant is then given the option to press one of two buttons; one to split the pot between the two of them, and one to steal the pot for themselves. However, there is a caveat. If both players choose to steal the pot, they get nothing. Neither player can see what the other chooses. If Player One chooses to split and Player Two chooses to steal, then Player One gets nothing. This is where the Prisoner’s Dilemma comes in. The Prisoner’s Dilemma shows why two completely rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interest to do so.

The Farnsworth House, first designed in 1946 and then built in 1951 by Mies van der Rohe, is an iconic masterpiece of internationalstyle architecture. It has no doubt been used countless times as a design precedent for aspiring architects looking to emulate its deceptively simple elegance. One year earlier, Philip Johnson announced the completion of his own design, aptly named Glass House. While not totally similar to the Farnsworth House, it’s not entirely dissimilar either. Johnson admittedly used Mies’s designs as a basis for his own: this culminated in Mies supposedly telling Johnson that he got the design all wrong.

Despite the apparent similarities and criticisms, Glass House is widely considered one of Johnson’s best designs. Whether or not these two designs are rip-offs of each other is not the point I am trying to make: these are both highly celebrated works of architecture regardless of their context to each other, but should their context to each other matter at all? Is it better to split your work in the hopes that others will choose to split as well, rather than stealing it for themselves? By safeguarding our own designs from becoming a facsimile of another, are we just contributing to the dullness of our own built environment? We must ask ourselves what is actually important when it comes to architecture.

The Architect’s Dilemma, much like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, is that designers want to improve and leave a mark on the world, but they want that mark to be their mark. Imitation is tolerated to a fault, do it too shamelessly and you lose total authorship of your work.

SPLIT/SPLIT. T his is typically the sweet spot of design. Everyone wins, ideas are shared, and boundaries are pushed. Architecture shouldn’t be the baseless stealing of ideas or the gatekeeping of good ideas, but a careful mix between the two, a mutually beneficial imitation and improvement of what we got right about design while still protecting the unique beauty of what made the first design successful. Architecture (especially Architecture school) has this concept of precedent, aka the projects you look at on archdaily.com and spend the rest of the design process retrofitting your design intent to back up your eerily similar design. This is tasteful imitation, pulling from multiple designs to create an original piece of work that may or may not be strongly influenced by a single design. When publishing work online or in journals, a designer understands that their ideas might become a part of someone else’s idea. If everyone operated this way, our built environment would be filled with beautiful, unique designs.

SPLIT/STEAL. A more cynical food for thought is that stealing is good— if it looks good. At the knife’s edge of imitation is the carbon copy, the unabashedly unoriginal design, the kind of building you look at and think, “that’s a Fay Jones building! What’s that doing here in Nebraska?” Shameless? Yes. Wrong? I’m not so sure. I would say we should lean further into imitating other projects. Steal, but steal well. In an idealist world, this wouldn’t be necessary, but we live in a built environment plagued by ugly design. At a certain point, when does it stop being about the ethics of ideas and start begging the question, “how do we effectively improve our surroundings?”

STEAL/STEAL. The problem with uninspired stealing is that, at some point, you end up with junk design. We’re talking cookie-cutter houses, strip malls, those “Live, Laugh, Love” signs everyone’s mom puts in the living room. This is a Steal/Steal situation, both players have lost, game over. This is where the power of the architect comes in. It’s the duty of the architect to ensure good quality work is produced; the source of that work is of secondary importance when it comes to improving the lives of people.

WRAPPING UP. Architectural intellectual property does have its issues with plagiarism but not nearly as much as entertainment media or product design. There’s no shortage of junk knockoffs of good products out there, it’s basically all Split/Steal and Steal/Steal at this point. Architecture suffers from the opposite problem: there’s an immense amount of good-quality ideas being put out and a total underutilization of those ideas. Bad ideas are being ripped off and good ideas stand alone as monoliths to great design. It’s not enough that these good ideas exist: they need to be used, and they need to be used a lot.

51 Fall 2023 Unicameral Essay: Split or Steal

By safeguarding our own designs from becoming a facsimile of another, are we just contributing to the dullness of our own built environment?

Pre-Crit C o nfidence

DARE THEM TO TEAR APART MY DESIGN

WOULDN'T THOUGH, RIGHT?

Overheard C o n versations

I

THEY

IT'LL PRINT IF I LEAVE

BACK LATER TAPE AND STICKY NOTES EVERYWHERE, THIS IS WHY WE CAN'T HAVE NICE THINGS

A DIAGRAM IS SUPPOSED TO SIMPLIFY A DESIGN MAYBE

AND COME

C o mments

BUT I NEED THEM TO KNOW ITS NOT A SIMPLE DESIGN Studio

I'D RATHER CLEAN UP A MAKE2D THAN READ THIS ARTICLE

SHOULD I DRAW EVERY MULLION LINE?

THAT WOULD TAKE HOURS

A LITTLE ERASER FOR LITTLE MISTAKES

YOU MIGHT NEED A LARGER ERASER

I UNPLUGGED MY LAPTOP 15 MINUTES AGO AND IT'S ALREADY DOWN TO 40%

WHOSE SKETCHBOOK JUST FELL AND HIT ME!?

hT e A r c h i te c ture StudentDilemma

C o n v e snoitasr

Overheard

Photography: © 2023 Madeline Cass 54

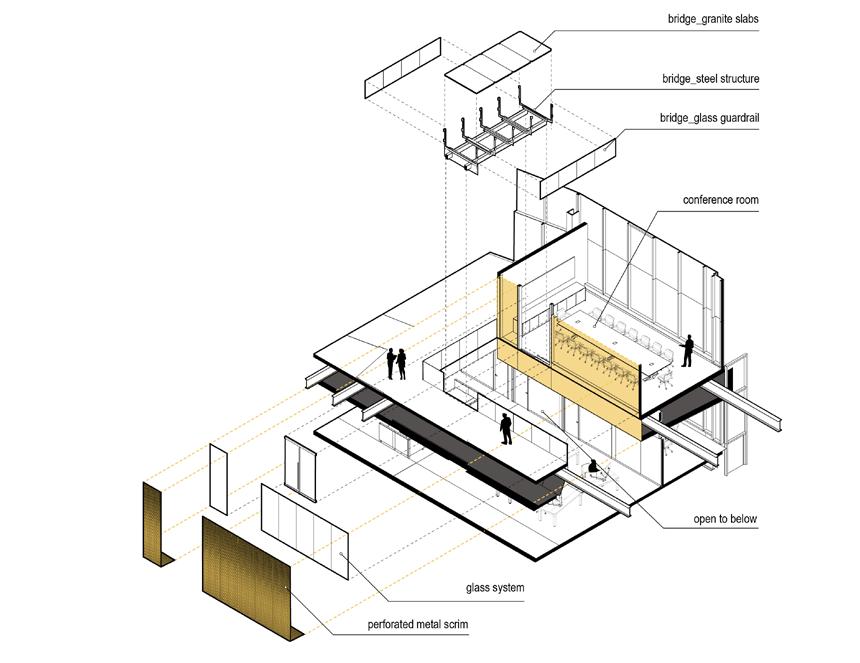

The Bridge to Collaboration

By Mitch Neujahr

Mentorship plays a pivotal role in career development. In architecture, this could not be any more true. Mentors are crucial to the architecture industry; they help guide and shape the next generation of designers. Having a mentor is helpful during every stage to becoming an architect, but it is much more crucial during the beginning of your architectural career. At Carlson West Povondra Architects (CWP), mentoring the next generation of designers is central to their firm culture. CWP states that, “strong mentorship helps us maintain continuity of firm culture as we look to the future.”

There are currently 24 employees at CWP and each play a role in making CWP a successful firm in Nebraska. They pride themselves on having a diverse group of people of all ages and backgrounds. They have recruited and maintained a highly-motivated staff, and each employee has the ability to bring their own perspective to future projects. The more experienced staff are partnered with younger designers providing a balanced collaborative environment.

CWP’s built works around Nebraska include a wide range of project typologies. Their “experience and expertise encompass 35 years of work in commercial, educational, municipal, justice, public safety, recreational, healthcare, civic/community, senior and supportive housing, and spiritual architecture.” They solve the needs of their clients with an innovative design approach that is unique to each project and specific to its user type.

During my interview, I sat down with Al Povondra, Owner; Bob Soukup, Principal; and Jamie Eckmann, Business Development/Interior Designer. Al Povondra started the firm in 1987, having previously worked at Leo A Daly, then as a staff architect under Paul Rudolph. He then went on to work for DLR Group before venturing on to start Carlson West Povondra. Bob Soukup earned his architectural degree at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and soon after graduating, he came onboard at CWP. Jamie Eckmann is one of three interior designers at CWP and also leads business development. She has been working at CWP for 16 years and has enjoyed every minute of it.

The CWP office has undergone many renovations since its establishment in 1987. Initially a Great Western Bank, the building was purchased by several attorneys. One of the attorneys, Mike Boyle, was the former mayor of Omaha. Eventually the office of attorneys broke up and the building went up for sale in 1992, that’s when Povondra bought the property. Soukup said, “for a time we shared this building with the graphic design firm, Webster Design,” and the two firms split the building in half. Granted, CWP was nowhere near the size it is today, and it was manageable. Dave Webster, the founder of the graphic design studio, ended up merging with another company and sold his business. The timing was perfect because CWP was growing quickly and needed more space.

55 CARLSON WEST POVONDRA ARCHITECTS

Left to right; Jamie Eckmann, Bob Soukup, and Al Povondra.

The building located at 5060 Dodge Street has been through many renovations over the last three decades. One of the most notable renovations made by CWP in 2003, addressed the entrance facing Dodge Street. Before this renovation, the ordinary entrance to the building was hardly noticeable to drivers passing by. The final design has stood the test of time, its modern style looks as though it was designed yesterday. When Soukup led me through this entrance, he emphasized that this renovation was important because, at that time, CWP’s design vision became a major factor in the future success of the firm. Their most recent renovation, completed in 2017, accomodated the growth of the firm by providing a more suitable space for effective collaboration.

Beyond the front desk on the second floor are spaces that can be closed off, offices designed for private meetings or calls. Soukup explained that they want the firm to be open and collaborative but also allow for private rooms when needed. On the first floor is a large, open studio filled with architects. This space is surrounded by offices on the perimeter and a large central meeting desk. The desk positioning acts as the bridge that joins everyone together. The open studio space is reflective of who CWP is as a firm. Walking through the space, observing everyone working together in harmony was motivating and inspiring.

56

57 Fall 2023 Unicameral Carlson West Povondra Architects

LEXUS OF OMAHA

Driven by Modernism

By Mitch Neujahr

If you live in Omaha, it is hard to miss the Lexus of Omaha dealership on 130th and Dodge Street. Its modern appeal is timeless beyond its construction in 2014. Carlson West Povondra Architects (CWP) was tasked to meet the highest levels of design thinking to represent the luxurious standards of the Lexus brand.

Al Povondra led the team with Mike Lacey and Bob Soukup as project architects. Povondra explained that “Lexus decided that the dealership was outdated,” with very few corporate architecture existing around Omaha at that time, “CWP had complete freedom to re-imagine the building.” Complete freedom. Some might see this as a huge benefit, but with unlimited freedom it's sometimes hard to know where to start.

Povondra said, “There were no blueprints established so we started with the founding principle of designing a museum for cars.”

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi was the main inspiration for the project, he explained. More specifically, they looked at Yamaguchi’s renovation to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Japanese architect uses elegant canopies and deep overhangs in his projects and this is reflected on the Lexus of Omaha building. The large deep overhang canopy makes the building look streamlined and elegant. The 7.1 acres of land was at a lower grade than Dodge Street. The client wanted to make sure the building was visible from the busy expressway. In order to achieve this, the building was raised up by sculpting the terrain. This also helped the building rise over the parked cars out front. Onlookers are able to see directly into the entrance from Dodge Street without obstruction. Lifting the building onto a “podium,” as Povondra describes it, allows for the main design feature of the building to stand out more—this feature being a sustainable biophilic wall.

58

Povondra is a “big proponent of biophilic design,” a reoccuring design element seen in other projects designed by CWP around Omaha. He explained, “It’s was one of the first green walls in Omaha.” A biophilic wall at this scale comes with a commitment from the client to maintain the health of a living wall. Soukup explained, “there will be varying degrees of sunlight and different amounts of moisture from the top or bottom of the wall.” A variety of plants were strategically placed throughout the wall space to create a well-balanced growth.

The dealership includes a service garage, a detached detail bay, and a carwash to the south. The service garage houses 33 service stalls with rooftop parking that can accomodate 70 cars. The project site is surrounded by single-family residences to the south. Povondra mentioned that the south area is protected by a thick wall of trees to keep the noise and light pollution away from the residential area.

The 60,000-square-foot dealership houses two showrooms, a customer’s lounge area, sales offices, and an employee fitness area. The material choices of the interior reflect the richness of the luxury vehicles in the showroom. The subdued interiors accentuated with rich mahogany wood, combined with the textures of the green biophilic wall, sets a stage that is both environmentally-aware and impactful to the experience of a potential Lexus owner. To catch a glimpse of this modern building from the expressway should appeal to anyone interested in buying a luxury car, at minimum, and also to lure those who appreciate and understand thoughtful architecture.

59 Fall 2023 Unicameral Carlson West Povondra Architects

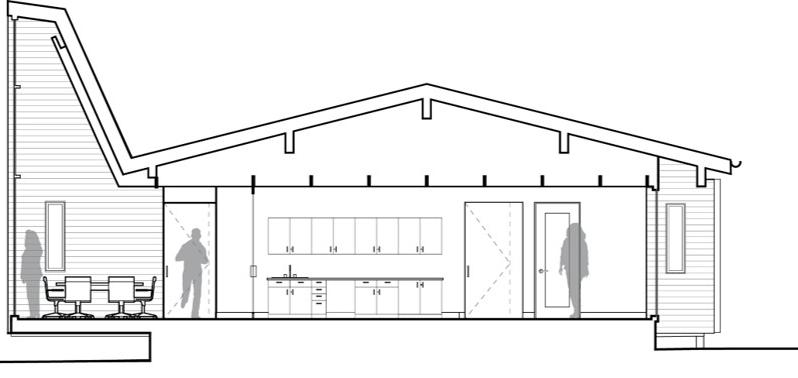

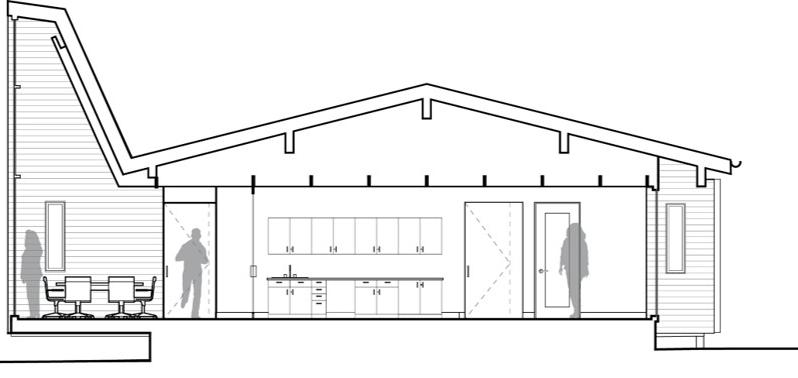

SECTION

Landscaping

Sales

Photography: © 2023

Frontage

Bamboo Planter Screen Living Wall Showroom Sales Office

Office Conference Room Design Center Green Roof

Tom Kessler

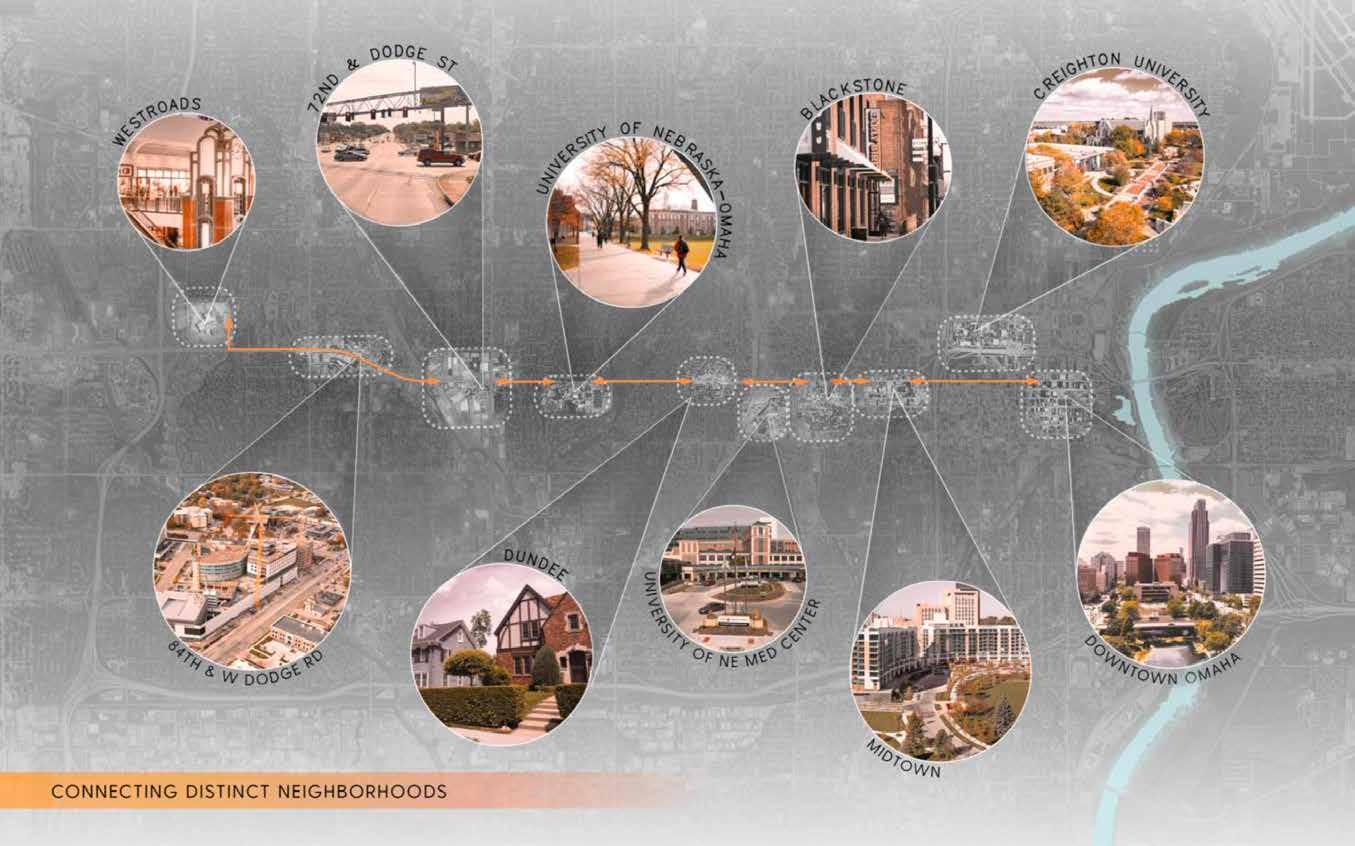

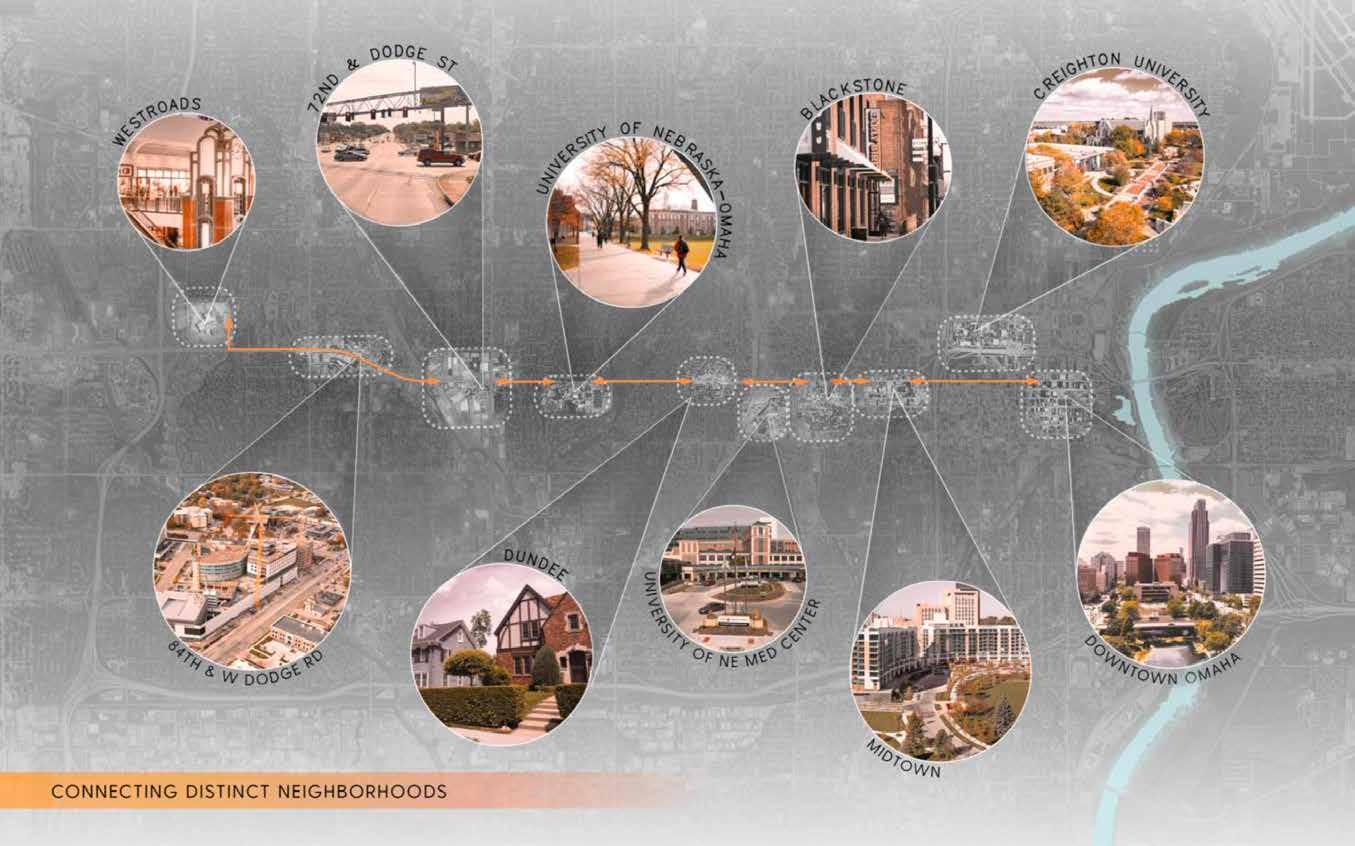

AN EVOLVING URBAN CORE

By Louis Khu

When was the last time someone told you they wanted to move to downtown Omaha—or Nebraska in general—for the rest of their lives?

60

People are always talking about wanting to move away to California, Florida, or New York; Nebraska is not even close to being a part of that conversation. If we take inspiration from successful urban redevelopment initiatives, could we make incremental adjustments towards our very own downtown Omaha? We’ve already seen a wide range of cities successfully urbanize their downtown core, such as the River District in Portland, Oregon and Brick Town in Oklahoma City. Downtown Omaha has been playing it too safe when it comes to ambitious design, and it’s scaring off our architects, communities, and businesses.

In recent years, the Greater Omaha Chamber Committee has decided to push our urban core to the next level. According to the Urban Core Strategic Plan, recent market studies indicate that our urban core is falling short of capturing the jobs and population it should. This has caused a negative impact on the neighborhoods surrounding the core on both sides of the river. The committee’s response is to invest $425 million towards a major revitalization project through the brand-new Gene Leahy Mall and the upcoming Kiewit Luminarium project, both of which will serve to reactivate the aging riverfront parks in downtown Omaha. We need to make sure we not only reactivate our core but also build upon and continually revitalize our central city to maintain growth. The committee makes it clear their mission is not to fix the problem in a short-term manner, but to help it develop into a model metropolitan area for others to emulate moving forward.

Though Omaha is behind on urban trends, we are already starting to see incremental developments. Take the new Gene Leahy Mall for example; Omaha’s version of Central Park Mall in Manhattan. This piece is one of three upcoming parks which include a sculpture garden, performance pavilion, and dog park. Surrounded by restaurants such as Omaha Tap House, Kitchen Table, and Dynamite Woodfire Grill, the Gene Leahy Mall component can serve as an extension of the Old Market district which is within walking distance. Overall, the parks are expected to increase civic engagement between downtown and the riverfront.

So, what can we expect moving forward? Over the next 20 years, this plan aims to attract 30,000 residents and 30,000 jobs to the urban core, drastically increasing the density of downtown Omaha. Public transportation will be developed to support a growing urban population as affordable housing programs provide new communities for diverse income levels. For the first time, outsiders may finally be interested in embracing a lively urban lifestyle in downtown Omaha. And maybe this will help put an end to the stereotype that Nebraska is nothing but plains and cornfields.

61 Fall 2023 Unicameral Essay: An Evolving Urban Core

Downtown Omaha has been playing it too safe when it comes to ambitious design, and it’s scaring off our architects, communities, and businesses.

ALLEY POYNER MACCHIETTO ARCHITECTURE

People First

By Mitch Neujahr

Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture (APMA) started out as a two-person group in a spare bedroom and has grown to become one of the most influential and successful firms in Nebraska. APMA prides themselves on putting people first and they “aim to lift up communities, making them more beautiful and vibrant, helping them be healthier, and inspiring them to learn and create.” Eric Westman, a long-time architect at APMA, explained in that they have a strong “dedication to put people first.”

With a current staff of 67 employees, their firm culture revolves around a sense of community and collaboration. Westman defines the firm culture as a place to “absorb” information in an open and collaborative environment. APMA architects, interior designers, and engineers are a varied group of people, they bring perspectives from different backgrounds and are dedicated to making Omaha a better place.

Westman, who earned his bachelor of science in architecture at the University of Kansas, wanted to become an archaeologist from early on in his childhood. In the 8th grade, his academic choices were limited, so he instead chose the next subject in alphabetical order to archeology which, as you might have guessed, was architecture.

APMA has a diverse range of project types in their portfolio in Nebraska and across the country. Projects range from government buildings to theaters to food halls. Over three decades of experience have produced award-winning architecture and interior design. Their website states: “we strive to create spaces that not only perform functionally, but also stir the imagination of their users while reconnecting them experientially to the world.”

62

Opposite page, left to right; Victoria Estep, Eric Westman, Loucinda Bauer, and Jeanie McCorquodale, design team for The Switch.

63 Photography: © 2023 Dana Damewood, Courtesy Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture

The firm has two offices: one in Omaha, and one in Red Oak, Iowa. They were first founded in 1987 in a spare bedroom and have grown into a firm powerhouse in the Omaha area. The Omaha office is in the vicinity of the Charles Schwab baseball field on 16th and Cumming Street. With collaboration being the key to APMA’s success, the studio space is open to promote interaction between employees.

The front entrance is tucked behind a large parking lot. It can be easy to miss when driving down Cumming Street. At the entrance you are greeted with a massive open aperture spanning multiple floors that extend to the rooftop allowing natural daylight to filter down to the ground floors.

The studio is an open environment and cubicles are non-existent. Despite the expanse of this open space, it was a surprisingly quiet workplace. Large windows on the north and west side of the building provide natural light throughout the day minimizing the need for electrical lighting.

High ceilings enhanced the openness of the space. Modern and minimalistic in style was consistent throughout the building. The materiality and color schemes, which are a mix of neutral and vibrant tones, create an effect of calm for creativity. Conference rooms and open spaces provide a healthy balance between private meetings and team discussions promoting interactive collaboration.

64

65 Fall 2023 Unicameral Alley Poyner Macchietto Architecture

THE SWITCH BEER AND FOOD HALL

Setting the Bar High

by Mitch Neujahr

Local food has always been an important aspect of Nebraskan culture. It can be a competitive scene for some local restaurants around Nebraska. The Switch Beer and Food Hall provides a home for up-and-coming local restaurants and provides a space for the citizens of Omaha to indulge in unique foods and drinks. APMA, the main designer for the food hall, “provides the perfect opportunity to celebrate Omaha’s industrial history and agricultural pedigree, all with a forward-thinking view of our city,” according to Eric Westman.

The Switch is capable of housing seven unique vendors with both indoor and outdoor dining. Westman explains they gained inspiration from the Milk Market in Denver, Colorado. The food hall in Denver is a much larger scale, with over 16 venues, but still helped APMA to start developing their own twist to define what a local food hall could be.

The waste solutions for the food hall is one of the best in the country. When consumers dine at the Switch, 100% of what’s tossed will be composted. They have set a zero waste goal, where 90% or more of expected waste output will be diverted from the landfill. Most importantly, The Switch educates take-out customers how to responsibly dispose of those materials.

What set this food hall apart from the rest was the fact it was a 3-Star Certified Green restaurant. To achieve this, they chose eco-friendly design routes like 100% LED lamps, dry wall with 95% preconsumer waste, and solar heat-blocking window film. Westman stated that it was a challenge to meet these goals due to the different needs of each vendor with varying degrees of requirements.

The Switch has closed business at the time of this writing; it is undergoing a new renovation and rebranding. The Switch was a creative concept that enabled local vendors to thrive; we hope to see something similiar to develop in the future.

66

Photography: © 2023 Emma Morem

REDLINING’S RIPPLE EFFECT

By Meagan Willoughby

Contamination Snow. While lead is often discussed concerning lead toys and household paint, in Omaha, residents in some neighborhoods unknowingly inhaled lead for over a century. The city was home to multiple lead-smelting plants, in operation from roughly 1870 until 1990, piping contaminants high into the air to then fall onto the neighborhoods around it and the Missouri River nearby in the form of “lead snow.” People had the potential to ingest lead from simply gardening or playing in their yard, where the soil had absorbed the lead snow for decades.

68

Lead exposure’s worst effects occur in children and infants. Early in life, lead exposure can interfere with gene development and can lead to an increased risk of disease and chronic health conditions. Lead exposure in childhood has been linked to increased aggression and likelihood of incarceration, and the health effects can include memory loss and difficulty concentrating, mood disorders, hearing and vision problems, and cognitive disabilities.

The worst of this lead pollution fell within a 7-mile radius from the plants. In a single zip code, over 40% of children tested showed elevated lead blood levels in 1998. Upon this shocking discovery, the City of Omaha invited the EPA into the city to help remediate. Within the 7-mile radius from the plants, 25% of children displayed elevated lead blood levels. The EPA designated a 27-square-mile zone contaminated and was officially labeled a Superfund site—the largest in the US.

Omaha’s Superfund site is home to a much larger percentage of the city’s Black and Hispanic population than the city, overall. This reflects a troubling but well-documented pattern in the US showing that, on average, areas with larger populations of racial and ethnic minorities experience higher levels of pollution and contamination. But why does this occur?