EDITOR’S NOTE

Dear readers,

Welcome to the third issue of Uncovered!

We’re very grateful for the support that our first two issues have received and are excited to bring you a new volume! As a small newsletter run completely by highschool students, it has been amazing to have had unique readers from six continents visit our site. We hope that we can continue to use our platform in this way to reach students our age across the world, and open their eyes to historical atrocities that have gone unnoticed, uncovered and rewritten in classrooms that disproportionately favour Eurocentric narratives.

Our third August issue is centred on the issue of Kenyan detention camps - also referred to as ‘gulags’ - at the end of British colonial rule. As I was researching potential topics for our third issue, I came across the work of Caroline Elkins, a professor of history at Harvard University, and was both intrigued and angered by the way this historical atrocity has been so systematically suppressed by successive British governments. For our previous two issues, our team has selected topics that are somewhat close to our own experience - whether they have been drawn from our personal cultural background, or our school history

curricula! However, for this issue, we wanted to step out of our own sphere of experience and select a topic that we could truly ‘uncover’ for the first time. After all, the purpose of this newsletter is to educate and to constantly seek truthand this applies to us just as much as it does to our readers.

Thank you so much to the amazing Uncovered team who made this volume possible! As always, I have felt incredibly privileged to have worked with an incredible team of writers, researchers, illustrators and designers from across the world for this issue. Even though we have never actually met in person, I am always in awe of the work that you all produce!

We truly hope that this volume opens your eyes to an issue that has gone far too neglected in world history - and perhaps sparks some much-needed discussion on how we can move forward.

Sincerely,

Eujiny ChoTHE RUNDOWN

Punch Maneesutham

The term ‘gulag’ refers to the system of labour camps that the Soviet Union operated from the 1930s until the 1950s. Though most people are familiar with the labour & concentration camps operated by the Nazis during WWII, many do not know that the British Empire ran its own labour camps in Kenya during the Mau Mau uprising.

minimal to no access to education, healthcare and political representation.

In response to these injustices, the Kenyans staged the Mau Mau uprising, a rebellion lasting from 1952 to 1960. Whilst the Kikuyu ethnic group primarily led it, other ethnic groups participated in the resistance as well, united by shared grievances under British colonisation.

Britain colonised Kenya in 1901, seeking economic and strategic benefits. The occupation began with the arrival of British explorers and missionaries, who gradually expanded their influence. With the establishment of the British East Africa protectorate, Kenya became a colony and was renamed British Kenya. The British treated Indigenous Kenyans like secondclass citizens, subjecting them to various forms of segregation and providing

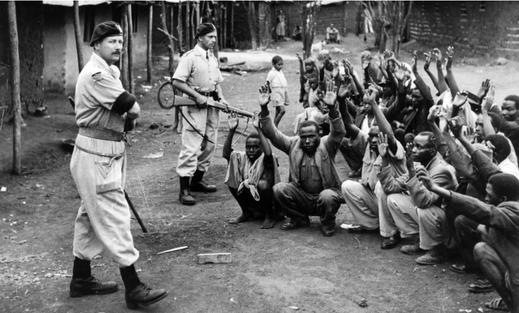

Amid assassinations and civil unrest, the British Kenyan government declared a state of emergency - marking the beginning of four gruelling years of military operations aiming to suppress the movement. The British forces, along with local loyalist militias, engaged in counterinsurgency tactics which included mass arrests, interrogations, and often brutal methods of extracting information. The impact of the military operations was devastating, resulting in the deaths of more than 11,000 rebels. The Mau Mau fighters faced significant challenges against the well-equipped British forces. However, they displayed resilience and resourcefulness in their guerilla warfare tactics - which included ambushes, hitand-run attacks and underground networks.

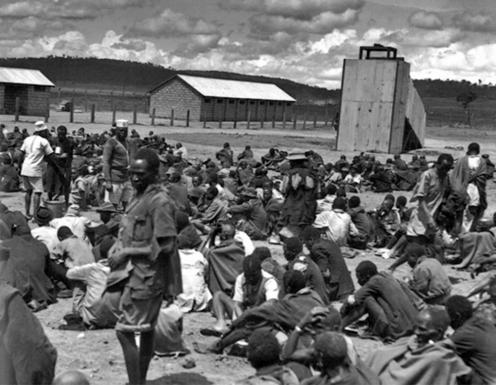

British soldiers searching for Mau Mau members, 1954 (Getty Images)To discourage Kenyans from joining the rebellion, the British government set up detention camps and ‘protected villages’ - essentially a euphemism for the campsall over the country. Kenyans suspected of having relations with the Mau Mau, including young children and the elderly, were subjected to horrendous methods of torture, regardless of their involvement. Upon arrival at the camps, detainees underwent assessments and were categorised based on their perceived ‘whiteness’; ranging from ‘Very black’ to ‘White,’ which determined their treatment and ‘re-education’ process. Thousands of women and children were forced into heavily guarded ‘villages’ surrounded by barbed wire fences and watchtowers, resembling the conditions that would be found in Soviet Gulags. Overcrowding was rampant, with inadequate provisions of food and water, and extremely poor sanitation. Physical abuse was also

prevalent, with many officers committing sexual assault and murder, further exacerbating the trauma inflicted upon the detainees. Some men were castrated by the officers using nothing but pliers; some women were raped with glass bottles. None of the detainees were given a fair trial.

The number of individuals held in these detention camps was staggering. Harvard professor Caroline Elkins estimates that there were roughly between 160,000 to 320,000 detainees. This devastating figure reflects the extensive reach of the British government's efforts to suppress the rebellion and exert control over the population. The physical and psychological scars left by the torture endured in these camps continue to haunt the survivors long after their release. Many survivors experience PTSD, some are unable to properly take care of themselves because of sustained injuries, and others have lost contact with their biological children since being separated. The impact of these traumatic experiences has reverberated through generations, leaving a lasting legacy of pain and suffering.

In Britain and Kenya, the governments ran propaganda campaigns villainising the Mau Mau, branding them as barbarians and a depraved tribal cult. The propaganda that was released inherently attempted to push the ‘us vs them’

thompson Falls Prison Camp, a detention site for hundreds of suspected Mau Mau fighters (SocialistWorker.org)narrative, alienating the Mau Mau from the Kikuyu and the Kikuiyu from the rest of the colony. A small number of the British press, parliament and activists, however, did protest against the military operation: most notably Barbara Castle, an MP who worked with other activists to publish an article in Tribune in 1955 seeking justice for the victims of British brutalism during the uprising. Yet, most of the prominent British thinkers and artistslike Ruskin and Dickens - were much more responsive to the atrocities committed in Jamaica and France. After the British had withdrawn from Kenya they had either incinerated or classified the documents relating to the camps. In 2013, the government settled the case after a long legal battle and announced that they would compensate 5,228 Kenyans.

MYTHBUSTERS

Evangeline AbhyA ‘Civilizing Mission’. A term to sanitise the campaign of terror over Kenya. After WWII, as Britain began to lose its hold over its colonies - such as India, Pakistan, Palestine and Burma - a Kenyan rebellion against its longtime oppressor erupted. We asked multiple students for their opinions regarding the Kenyan Rebellion, the reparations involved, the death tolls and most importantly the Gulags.

How do you believe that the British left Kenya after its colonial rule? Do you think they provided reparations for the damage that was done?

In my opinion, just as the British were forced to leave India after a long struggle, they would have left under extremely dire conditions. Regarding reparations, I doubt any had been provided for the damage as India did not receive any.

I think the British would have suffered extreme losses due to the defeat they might have incurred. Normally this would not have been expected of the British Empire (i.e. to be defeated) but given the circumstances of the World Wars, there is a good possibility.

How do you believe the Gulags functioned, and what kinds of atrocities do

you think were inflicted upon the people?

I don’t really know much about the Gulags but I assume it would be somewhat just as heinous or maybe worse than the Concentration Camps built by the Nazis. Probably they were built for Kenyan civilians or people that the British felt threatened by?

I think a lot of the torture was inflicted, aimed at disrespecting and humiliating prisoners apart from physical sufferings. I don’t know how these Gulags functioned exactly or what their specific purpose was, but they could have been built as detention centres, or to stifle any rebellion, or even for extermination.

Muthoni wa Kirima, during the Mau Mau uprisingIt is best to review testimonies of the survivors. One author states the nature of the detention camps: “The detention system, officially named the "Pipeline", meticulously sorted people according to their Mau Mau sympathies. "Whites" –mostly women and young children – were viewed as the least dangerous. The government shipped them on trains and lorries to the overcrowded reserves, where they lived and worked under armed guard. "Greys" were guilty of Mau Mau involvement and worked in moderately punitive labour camps. "Blacks" – hard-core insurgents – were banished to the harshest prisons.”

Do you know how many deaths occurred during this time? Of both the British and the Kenyans?

Considering it was a full blown internal conflict it could be relatively equal on both sides.

I think the death toll for the Kenyans side would be higher compared to the British.

I think the Kenyans death toll is higher but I’m not really sure.

Major facts repressed from the public involved the deaths involved in the Kenyan Emergency. According to sources only 95 Europeans were killed, yet the total of Mau Mau deaths in combat is estimated as 11,503 and by Caroline Elkins's estimate, “at least 160,000 Kikuyu were detained (almost all without trial) and brutally ill-treated”. This was also

exacerbated by anti terrorist laws, which suspended the rights of suspects and permitted torture, punishments and the death penalty for trivial crimes. The Mau Mau were branded as illegal, and the Kenya African Union was banned on the grounds of War and Political Struggles.

As we hear of freedom fighters or major leaders that led their respective countries to freedom from their oppressors, have you heard of any leaders or prominent people that might have led the fight for freedom in Kenya?

I cannot recall any names at the moment.

The Kenyan revolution is in itself relatively new for me. I had never heard of it before today.

Survivors such as Muthoni wa Kirima provided her own account as she was the most senior commander of the Mau Mau land. She not only fought for the freedom of her nation, but also had to stand and fight for women’s rights.

We’ve noticed only a few people know about these Kenyan Gulags, the rebellion and so on. Why do you think that is? Do you think certain people of groups were trying to bury it on purpose?

I agree that we barely get information regarding this conflict. I’m not sure why the information hasn't reached out to the rest of the world properly, but I do hope it does in the future.

I think the information could be suppressed or it just could not have reached out to the rest of the world.

As the British attempted to bury details about the Mau Mau conflict when they left in 1963, it is not surprising to see that many people did not even know the existence of this major atrocity. Hence it is only honourable that their stories be told. And a collective responsibility be taken up to bring these atrocities to light and provide due respect, reparations and justice.

THE ISSUE, TODAY

Michaela ChenTopic 1: Cover up and misinformation

How can large-scale, systematic torture and murder disappear into oblivion? Why is modern society ignorant of the happenings in British-controlled Kenya, or view those events as a mere blip in the timeline of British imperial accomplishments? How can this be if not for meticulous cover-up by the British government, lasting from the moment these tortures began and persisting till recent years?

When Caroline Elkins began seeking answers regarding the British Empire’s reaction to the Mau Mau uprising, she realised that the scale of the event was wildly disproportionate to the number of records that remained. Upon further research and deep dives into the available archives, it became clear that there were relevant records missing or destroyed, records that would undoubtedly be incriminatory to the British government if revealed. While the proof Elkins gathered had confirmed some atrocity, the damning evidence was uncovered in 2010, when the British government was pressured into admitting he existence of thousands of files that had been extracted from Kenya in 1963, the year Kenya gained independence. These files proved the alleged tortures suffered by Kikuyu under the British, and marked an important – however late – step toward transparency.

Looking ahead, we can only hope that this transparency continues as many seek acknowledgement and closure.

Topic 2: Inner conflict caused by British

Many nations across the developing world have recently become independent. Kenya is one of these nations, only having gained independence in 1963 from the British Empire. Being thrust onto the world stage after an era of oppression and exploitation is no simple task,

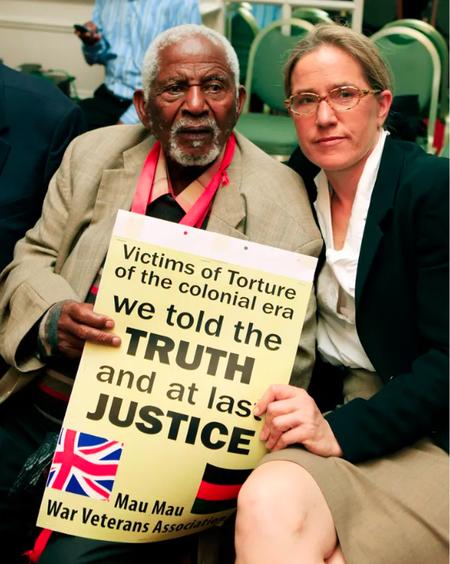

Caroline Elkins with Gitu Wa Kahengeri, secretary general of the Mau Mau War Veterans Assocation (Reuters)especially because the British Empire placed Kenya at a striking disadvantage through methods of exploitation which continue to leave their mark today. When the British began occupying Kenya, they knew it was impossible to conquer the people through sheer manpower, although the British undoubtedly had superior weapons. Instead, they decided on the tactic of “divide and rule”, a strategy that had been used by the British in other colonial undertakings such as India. The strategy entailed creating rifts between various people groups in the region, keeping the local people divided in order to subjugate them more easily. It was successful, and even one of the most significant Kenyan rebellions – the Mau Mau uprising – had a significant number of natives fighting on the British side. Though the British left Kenya in 1963, the rifts between many Kenyan groups remained. As Kenya develops and grows, internal conflict continues to be a major stumbling block for the nation, with the major contributor often cited as colonial tactics. The cruelty conducted by the British government did not leave in 1963, but continues to mar Kenyan society today.

Topic 3: Acknowledgement and reparations

In 2012, the truth about Kenyan torture victims was dramatically uncovered during a court case involving a group of abused Kenyans who sued the British Government for their crimes. After trying to dismiss the case many times –saying that the Kenyans should be suing their own government rather than the British, and that too much time had passed for the trial to be held – the British government finally agreed to pay a sum of approximately 30 million dollars to the remaining survivors. Given the number of survivors, the final sum that each individual was paid amounted to approximately 6 thousand dollars. Along with a formal apology, the British government acknowledged the atrocities they conducted in Kenya for the first time ever. Although the sincerity of the British apology will perhaps always be up for debate, and the torture suffered by Kenyan victims cannot be undone under any sum of money, the Kenyan victory in this court case no doubt marked the beginning towards healing and growth. Although there remains a long way to go, the first step is often the hardest, and there is always hope for the future.

Mau Mau veterans celebrate the outcome of the landmark 2012 case (Associate Press)

Mau Mau veterans celebrate the outcome of the landmark 2012 case (Associate Press)

OPINION PIECE

Eujiny Cho

It’s Time for the Royal Family to Own Up

8 September, 2022. On this day, the death of Queen Elizabeth II shook the world. Whilst political leaders expressed their respects for the monarch and observed national periods of mourning, the pageantry surrounding her passing failed to mask the tensions that simmered beneath the surface. While staunch royalists outpoured their grief on social media, others found it difficult to untangle this enduring reverence for the monarchy with a legacy of profound cultural disruption and intergenerational trauma.

For thousands across the world, the British monarchy holds vast symbolic power. For thousands, this institution represents the ideals of glory, stability and prestige; a reliable constant in a confusing and ever-changing world. Even in my own country, Australia, families celebrate the King’s Birthday with an almost-religious fervour and proudly display royal memorabilia on their spoon racks.

But behind the shiny veneer, the monarchy has masked for centuries a brutal legacy of violence, theft and dispossession. Five centuries ago, Henry

VIII first declared the existence of a ‘British Empire’, and his daughter Elizabeth I would go on to sponsor one of the first ships to profit from the Transatlantic Slave Trade. For the next four hundred years, successive generations of royals took up the baton on colonial expansion. From 1765 to 1938, the empire was estimated to have transported 3.1 million African slaves and drained $45 trillion of wealth from India alone.

Even more recently, as ideals of selfdetermination spread across the globe post-WWII, the monarchy suppressed independence efforts with brutality and violence. In Malaya in 1948, insurgents were subject to mass detention without

Protestors demand reparations for former colonies amid Prince William’s Caribbean tour (iWitness News)

Protestors demand reparations for former colonies amid Prince William’s Caribbean tour (iWitness News)

trial. In Kenya in the 1950s, thousands of colonial subjects were rounded up into barbed-wire villages where they were starved and tortured. In Cyprus in 1955 and Yemen in 1963, royal squads were deployed to terrorise and torture civilians. In Nigeria’s Civil War in the late 1960s, British intervention exacerbated a humanitarian catastrophe that led to the estimated deaths of one million Biafran children. Yet, the monarchy has done little to take responsibility for its crimes. No formal apology, no regret, no shame, no reparations, no moral accountability. On a tour of former colonies in the Caribbean last year, Prince William expressed “profound sorrow” over the events which “forever [stain British] history”; yet conveniently failed to acknowledge that the monarchy created that history. Or that, since the establishment of the British Empire, every member of the royal family has continued to benefit from history.

What is even more concerning is the farreaching effect of the royal family’s inaction on wider public sentiment. A 2020 YouGov survey revealed that 30% of Britons felt that colonies were ‘better off’ under the empire. Activists who have attempted to denounce the monarchy’s atrocities, such as Labour Party member Barbara Castle, have failed to gain wide public traction. The British education system says little about the horrors of imperial history. Public monuments that

glorify the empire are rife across the country. Even politicians have relied on imperial nostalgia to earn public support; for example, after the Brexit vote, the UK government promoted the notion of a ‘Global Britain’, adopting imperialist rhetoric such as ‘the world is our oyster’ and ‘[we can] transform the world for the better.’

As an institution that carries so much symbolic power, its refusal to admit to its legacy of violence, plunder and slavery instils apathy across its population. Further, it creates the conditions for a dangerous process of mythologisation; of the ossification of an outdated patriotic fantasy about British greatness and glory during the imperial era.

This is a crucial time for reckoning. The past is not ‘long gone’ or something to be ‘forgotten.’. The British monarchy must stop ignoring its colonial history and

Queen Elizabeth II on a tour of Kenya in 1983, 20 years after its independence (Avalon/Getty Images)finally face up to its crimes. Without a meaningful apology and proper reparations, there will never be healing for the communities whose ancestors have been dispossessed and enslaved and oppressed by the royal family. Without public acknowledgement and a redistribution of wealth to victims of imperialism, national consciousness and public perception of colonialism will never change. Using the momentum of the conversations sparked by Queen Elizabeth’s death, we must ensure that the future truly does involve change and not more complacency. It simply begins with opening our eyes.

RAYS OF HOPE

Eujiny Cho

Online ‘Emergency Exhibition’

In 2018, the Museum of British Colonialism collaborated with Kenyan and British historians to create an online interactive exhibit about the Mau Mau detention camps. The exhibit consists of oral history interviews with local Kenyan communities and Mau Mau veterans; archival records, such as photographs, books, maps and videos; and digital 3D reconstructions of some of the main detention camps, created entirely from archival photos and oral interviews. Whilst colonial history tends to be dominated by the voices of those who have studied it from a position of distance, this innovative project aims to privilege and centre the previously silenced stories of those who have directly experienced the impacts of colonialism; and thus resist the systematic suppression of marginalised voices. We strongly recommend that you visit the exhibition at this link: https://museumofbritishcolonialism.org/e mergencyexhibition/

Promisingly, other oral history projects are also taking place across the globe to preserve the stories and experiences of

Mau Mau veterans, such as the collaboration between Caroline Elkins, Harvard graduate students and the Kenyan Oral History Centre.

The Mau Mau Case

In 2009, five Mau Mau veteransrepresented by Leigh Day & Colaunched a reparations claim in Britain’s High Court. They, like thousands of other claimants, had been subject to unspeakable abuse at the hands of British colonial officials in detention camps. Despite constant pushback from the government - based on the arguments that ‘too much time had elapsed’ since the events, and that the Kenyan government had inherited responsibilitythe veterans collaborated with historians Caroline Elkins and David Anderson, as well as the Mau Mau Veterans Association

A 3D reconstruction of the Aguthi Works Camp from the online ‘Emergency Exhibition’ (Museum of British Colonialism)and Kenyan Humans Rights Commission, to collect evidence and oral testimonies. Further, the fortuitous discovery of previously undisclosed government files in Hanslope Park in 2011 provided direct evidence of colonial-directed coercion and torture of Kenyan civilians. Finally, in 2013, justice was delivered as the British government officially acknowledged that Kenyans had been subject to abuse at the hands of the colonial administration; and agreed to pay £19.9 million in reparations to over 5,000 claimants. This was a momentous step forward, representing the first time in British history that victims of colonisation could claim compensation from the government.

As a result of the settlement, the government also collaborated with the National Museum of Kenya and the Mau Mau War Veterans Association to construct a memorial in Nairobi recognising the victims of torture and abuse, which was unveiled in 2015.

Kenyan Human Rights Commission (KHRC)

Founded in 1992, this organisation broadly aims to achieve social justice and protect human rights in Kenya and beyond, and played a vital role in the Mau Mau case. After their appeal for an official apology to the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office was rejected in 2007, they filed an appeal for a trial with the High Court in 2009. A taskforce, led by George Morara, interviewed potential claimants and chose the five veterans that would lead the case; and together, with Elkins and Anderson, gathered oral testimonies, documents and artefacts to present as evidence. All the while, members of the Commission organised meetings between claimants and the then-prime minister Gordon Brown behind the scenes; appealing for a welfare fund, community reparations and monthly stipends for veterans. Now, since the success of the case, the Commission continues to establish a database of testimonies from Mau Mau veterans. Whilst grateful for the support of the British public during the trial, Morara comments that ‘[he’d] be very glad if the

international community joined in’ to ‘start a new discourse.’

But more action is needed...

Whilst we generally like to focus this section on the positive progress that has been made, it has to be acknowledged that far more action must be taken by the relevant authorities before justice is delivered.

Whilst the KHRC found that politicians such as Brown and Miliband were ‘sympathetic’ to their appeals for further reparations, they have failed to find a similar level of support in successive Conservative governments since 2010

According to members of the Mau Mau Original Lobby Group, the £19.9 million sum paid in 2013 is insufficient as it was calculated based on the census data from the 1940s - and thus fails to reflect current population levels

Despite more than 100,000 Kenyan citizens petitioning the royal family for reparations in 2022, as well as writing a letter to Prince William to support justice efforts, there has been no response; further, the Foreign Office continually declines meetings with community leaders

A second Mau Mau case was launched in 2013 as more than 40,000 Kenyans sued the British government in a group litigation order; the case was dismissed in 2018, as the Chief Justice argued that the difference in time between the ‘alleged atrocities’ and the lodging of the case was ‘too long to enable a competent trial’ - despite decades of misplaced and destroyed evidence by the British government

Complacency breeds inaction. We must increase public discourse and attention on the issue to motivate the British government and the royal family to make greater changes.

MEDIA REFERRALS

Abha Dabal

NON-FICTION BOOKS

Imperial reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain's Gulag in Kenya

FICTION BOOKS

"Weep Not, Child" by Ngg wa Thiong'o

Written

by Caroline Elkin,professor of

and African and African American Studies at Harvard, this book documents the atrocities committed against the Kikuyu people in Kenya, which were initially intentionally covered up during the transition to independence in Kenya by the British government. It investigates Kenya’s Mau Mau uprising and unearths a catalogue of cruelty, giving a profoundly chilling portrait of the barbaric treatment of the detainees. Elkins also received the Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction in 2006 for this book.

HistorySet during the Mau Mau uprising, this novel chronicles the journey of Njoroge, a young Kenyan kid, as he makes his way through a turbulent political environment and personal challenges. The impact of colonialism on people and communities is explored through a compelling narrative that emphasises themes of identity and resistance. This book also sheds light on the power dynamics between the colonisers and the colonised, as well as the brutality of the Mau Mau rebellion.

Histories of the Hanged

by David AndersonThis book gives a thorough and succinct history of the Mau Mau uprising, exposing the terrible methods used by the colonial government, such as hanging purported insurgents. It explores the complicated interactions between the various political and ethnic groupings in Kenya and provides insight into the motivations and grievances of the Mau Mau fighters.

"The Grain of Wheat" by Ng'g wa Thiong'o

This thought-provoking novel centres around multiple characters who took part in the Mau Mau uprising and explores their motivations, sacrifices, and ideological conflicts. It investigates the psychological effects of revolution and the search for identity amidst the struggle for independence.

MOVIES

"The First Grader" (2010)

This endearing movie, which is based on a true event, depicts an elderly Kenyan man's pursuit of education while also highlighting his participation in the Mau Mau insurrection. It perfectly illustrates the resilient nature of people as well as the profound legacy of historical injustices on individuals.

PLAYS

"The Trial of Dedan Kimathi" by Ngg wa Thiong'o and Micere Githae Mugo

The life and prosecution of Dedan Kimathi, a pivotal figure in the Mau Mau revolt, is explored in this compelling and thought-provoking play. Through compelling dialogue and symbolism, It emphasises the complexity of the battle for independence and its effects on society.

Simba" (1955)

A gripping adventure drama set in colonial Kenya during the Mau Mau Uprising. Former English soldier Alan Howard returns to find his land in ruins. As he grapples with his past, he develops a complex relationship with his loyal Kenyan worker, Kimani. The movie explores issues of racial discrimination, loyalty, and cultural disputes during a turbulent historical era. Alan and Kimani's friendship is put to the test as Kenya fights for independence, echoing the wider tensions of British colonial rule.

Still from ‘The First Grader’ (National Geographic Entertainment) Still from ‘The Trial of Dedan Kimathi’ (WordPress)CONTRIBUTORS WRITERS

Eujiny Cho

Punch Maneesutham

Evangeline Abhy

Michaela Chen

Abha Dabal

ILLUSTRATOR

Jisoo Han

DESIGNERS

Karina Gunawan

Amy Feng