Editor'sNote

Dear readers,

Welcome to the second issue of Uncovered! From the bottom of our hearts, our team would like to thank everyone who read and supported our first issue It was a genuine honour and joy to hear that it taught readers something new about important uncovered histories, even if it was in little ways.

If you are new to Uncovered, we are a student-run newsletter that aims to educate readers on historical atrocities committed towards marginalised communities that have gone unnoticed or rewritten And more importantly, show how the lingering impacts of these issues are still felt potently today.

We are incredibly excited to present our second volume, which is centred on the historical cultural genocide of Indigenous groups across the world. Being loosely defined and not yet ratified in international law, cultural genocide has always been a contentious and generally neglected topic; it always seems to be overshadowed by more ‘pressing’ issues in international discourse. For this issue, our Uncovered team was largely inspired by many of our own experiences in the classroom, of receiving little to no respectful education on the stories of the Indigenous communities in our respective countries. So for this issue, we wanted to shed light on just how significant and damaging cultural genocide has been throughout history Ground it in hard, indisputable evidence

Thank you so much to the wonderful Uncovered team who made this volume possible! It was lovely to work with writers, designers and illustrators from the first issue - and also bring on board some new members!

To end, I’d like to leave you with a quote from Vine Deloria Jr, an activist for American Indian rights, that I think sums up this volume so perfectly: “a society that cannot remember its past is in peril of losing its soul.”

Sincerely,

Eujiny Chonote

The Rundown: Australia and North America

Mythbusters

The Issue, today: Australia and North America

Opinion Piece: A New Stolen

Generation: the Epidemic of Indigenous Incarceration

TheRundown:Australia ByEujinyCho

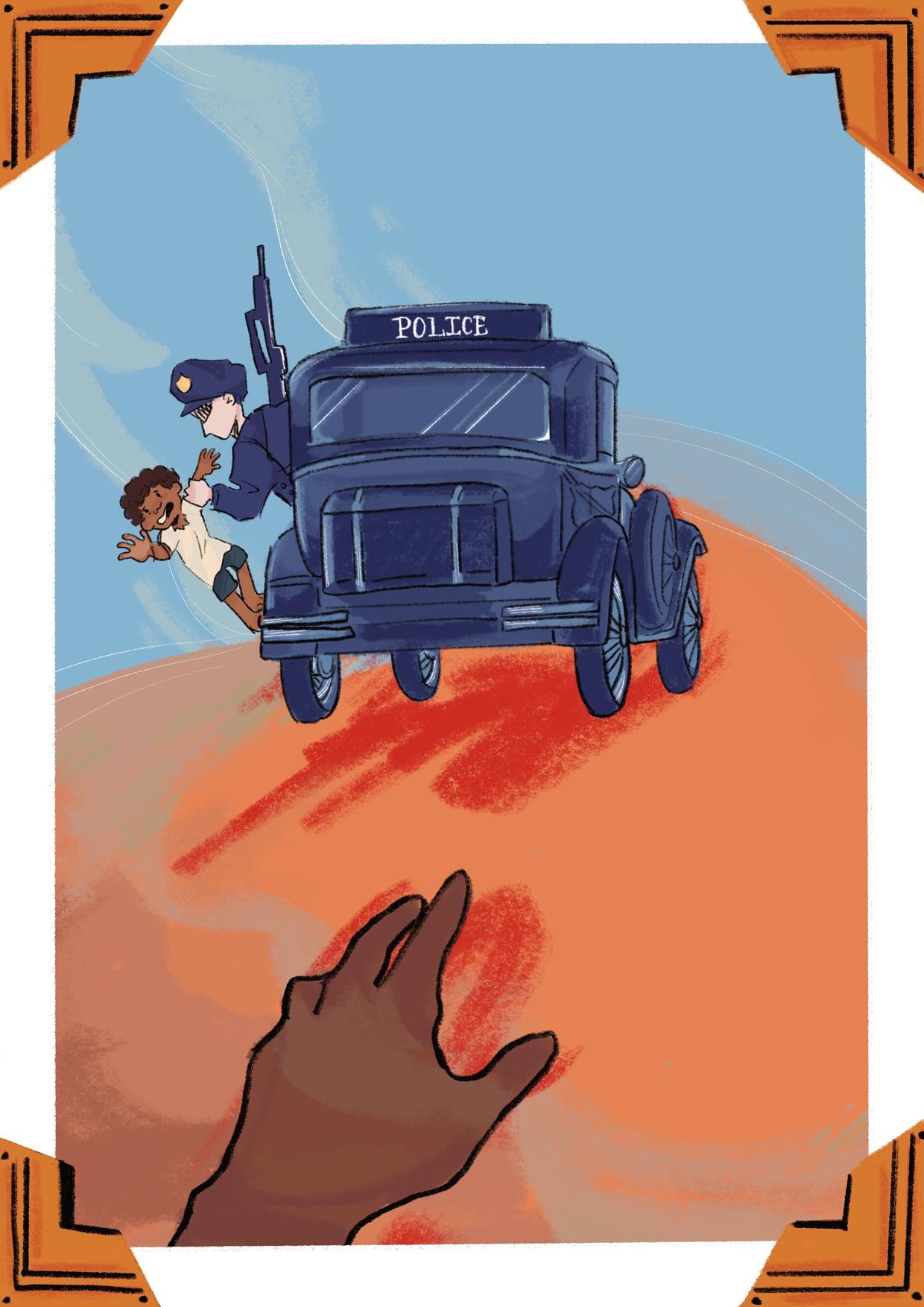

The Stolen Generation refers to the period between the 1910s and 1970s in which thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities - to be raised in missions, reserves, or white households, and to undergo harrowing years of cultural erasure and trauma.

This atrocity had its origins in deep-rooted racism towards Indigenous Australians, which began with the colonisation of Australia in 1788 and only worsened through decades of dispossession, conflict and violence From the late 19th century, the rising concept of paternalism - the idea that Indigenous Australians were incapable of caring for themselves due to their innate ‘inferiority’ - led to the Aborigines Protection Act of 1909 that lent state governments power to forcibly remove supposedly ‘destitute’ and ‘neglected’ Indigenous children from their families. Relocated to missions and reserves, these children were segregated from both European settlements and their own communities; cut off from their culture, livelihood and language and treated, in essence, as a ‘dying race.’

However from the 1930s, when it became clear that Indigenous Australians were not ‘dying out,’ the government shifted their approach to an equally sinister and aggressive policy of assimilation that was officially ratified in 1937 One that aimed to ‘breed out colour’ in the Indigenous populations and ‘civilise’ those individuals whose ‘Aboriginality could be overcome.’ Whilst fully Indigenous children remained segregated on reserves and missions, biracial children were forcefully absorbed into white communities in an

Mission Bay Aboriginal ReserveTheRundown:Australia ByEujinyCho

attempt to assimilate them. Children in reserves were exposed to terrible living conditions and a significant proportion developed severe depression, PTSD and substance abuse. Children in households were often rejected by both the white communities they were absorbed into and their Indigenous communities, ultimately unable to find a sense of belonging anywhere. However, despite their vastly different experiences, some aspects were common to a life in both a children’s home and a white household: an inability to participate in any form of cultural practice or speak one’s traditional language; the dispossession of one’s name and identity; and severe physical, psychological and sexual abuse. The inherently contradictory relationship between segregation and assimilation highlights the confused, irrational and racist policy that dominated the period; policy that sought primarily to stamp out Indigenous Australians by all and any means necessary.

Despite the repeal of legislation that allowed for the removal of Indigenous children in 1969, many missions and reserves did not close until the early 1980s; and even today, the practice of removal continues. 16% of Indigenous children are in the hands of child protection services - 8 times the rate of their non-Indigenous counterparts.

TheRundown:NorthAmerica

ByMichaelaChenThe story of native peoples in North America is one that is often lost in the telling of American history Their story, though acknowledged, is often not explored in much detail or solicitude. Many factors contribute to this, not the least of which are the US government’s efforts to assimilate American Indian children into white society.

Before the arrival of European settlers, North America was populated by large numbers of indigenous people, who grouped themselves in diverse tribes throughout the continent. Rich with culture, each tribe was distinct from the next Some lived on the plains, practising a nomadic lifestyle, some lived in the woodlands, others in the desert. However, with Columbus’ arrival in the Americas in 1492, and the subsequent European colonization, the lives of the Indians were changed dramatically.

In the years that followed, Native Americans saw their livelihoods being taken away one step at a time. What started with seemingly harmless English settlement on tribal lands ended with the forced removal of tribes in the infamous Trail of Tears in the 1830s to 50s. According to many history textbooks, this is where their story ends.

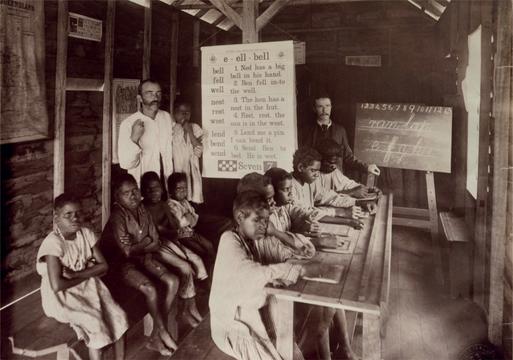

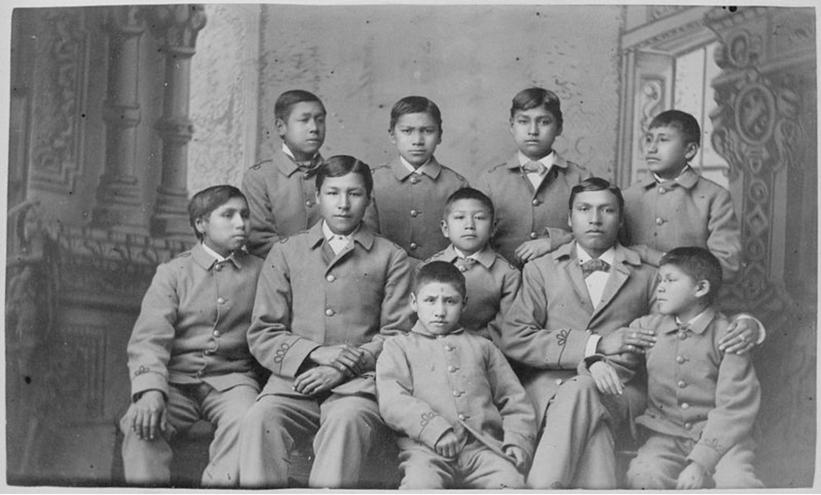

Forcibly removed children at Carlisle Indian SchoolTheRundown:NorthAmerica

ByMichaelaChenHowever, this notion is mistaken, and Indians continued to be ostracized by American society. White Americans viewed the natives as inferior, and soon came up with a plan to “lift” them from their perceived lesser position. This plan was simple: to send Indian children to boarding schools that were located outside of the reservation premises. They would be taught to speak English, made to wear Western clothing, and brought up into “civilized” society.

A prominent leader in this effort was Col Richard Henry Pratt, who famously said the line that summed up all the government’s assimilation efforts: “Kill the Indian, save the Man”. In keeping with this vision, he established the Carlisle Indian School in 1879, which would enrol around ten thousand Indian students throughout the course of its run To the US government and the white population of America, schools like these were a perfect solution to the “problem” of indigenous peoples. But for the Indians, these projects stripped them of their culture, traditions, language, and identity And although the schools were meant to “assist” the children, the school’s conditions were poor, showing the extent to which the government truly cared about the natives.

Living in these harsh conditions, students started to die from sweeping epidemics and malnutrition. By the time of its closing in 1918, hundreds of Indian children had died and been buried in unmarked graves, often without the knowledge of their distant family. The legacy of American Indians is one that is easily forgotten and dismissed. Looking back, it is easy to see why. The US government has long tried to erase Indians’ history and cover up their identity. But even so, pieces remain, and those pieces have a powerful story to tell

The unmarked graves of children at an American Indian boarding schoolMythbusters

For this volume of the newsletter, we decided to open up our interview section to everyday students! To students in high schools across the world, we posed some questions that addressed the most common myths and misconceptions about Indigenous cultural genocides - below we’ve summarised the main responses for each question. We wanted a good cross-section of society to see how much we already know about the issue and gauge where there is more work to be done in education. Enjoy reading through - maybe you’ll bust some of your own myths!

Did you know that Indigenous children in Australia and America were removed from their families? If so, why do you think so?

I knew that American Indians had their land taken away; however, I didn’t know that children were removed

Yes; the government maybe separated them because they thought Indigenous communities were not safe

I knew about America but not Australia

Thousands of children from Indigenous communities were forcibly taken in the 19th and 20th centuries. The main reasons for this removal were policies of segregation and assimilation that aimed to effectively ‘stamp out’ the Indigenous identities and cultures of children.

Were the children taken because they were in danger?

About 70% said no, which is the correct answer!

How were Indigenous children treated when they were taken away?

I think they were treated against their human rights

They were taken forcefully

The general gist of all the answers is correct! They were removed forcefully from their families and placed in reserves, missions or boarding schools, where they often experienced severe abuse and were severed from their communities and culture.

Mythbusters

How long ago did this practice of removal occur?

About 100-150 years ago?

From 1800s to early 1900s

The general timeline for Australia is 1910s-1970s, and America is 1870s-1960s. However, even today, some remnants of the past still remain! Hundreds of Indigenous Australian children are removed from their families each year to be put in ‘out-of-home care,’ whilst about two-dozen off-reservation boarding schools still operate in America.

How has the relationship between Indigenous groups and governments been throughout history?

Conflicting

for sure

They have been at odds

Probably antagonistic; a lot of stops and starts

Again, the general gist of the answers is correct! Reparations, official apologies and reconciliation have been huge points of controversy in the past decades as governments have often engaged in tokenistic acts that don’t address meaningful healing.

Does it seem like Indigenous groups today mostly have a good life?

No, from many TED videos I have seen they don’t have a good life. Housing is a problem, the government doesn’t support them and only takes their land away etc It doesn’t seem so; they have been robbed of their rightful land and also have a hard time finding jobs (especially with discrimination)

Not at all; especially in Australia education and health is a big problem and the justice system unfairly targets Indigenous people

This question had some great answers that showed accurate and comprehensive knowledge of ongoing issues today. Overall, it seems that whilst knowledge of the present is good, it’s what occurred in the past that still remains largely obscure for students across the world.

–FirstNationswomanfromthe Kimberleyregion,memberofthe StolenGeneration

“Howcananyoneforgetthat?We passitontoourkidsjustlikemy parentspasseditontome.Itstays withyou’tillyoudie.I’veseenpain allmylife.Itleavesscarssodeep”

Theissue,today:NorthAmerica

ByMichaelaChenDespite small steps made toward the improvement of Indian Americans’ lives, many continue to struggle against the overwhelming disadvantages that have been placed in front of them since birth. These disadvantages can be seen in factors as simple as education. The Bureau of Indian Education, or the BIE, has been charged with providing education for children. Operated largely under the federal government, BIE schools are often the only access that Indian children have to education, especially those who live in rural areas. However, proficiency reports of the BIE schools show that their quality of education is egregiously low, with many students lagging behind the national standard by multiple grade levels. This tragically recalls the terrible conditions that Indian children endured in boarding schools of the past. And although the US government has long promised to reform the program, changes have not been significant, leaving generations of Indians uneducated and unable to rise out of the poverty cycle. From xenophobic boarding schools to inferior education, Native American children have been disadvantaged in American society from the start Unfortunately, this is not something that can be confined to the past, but continues to be a struggle today.

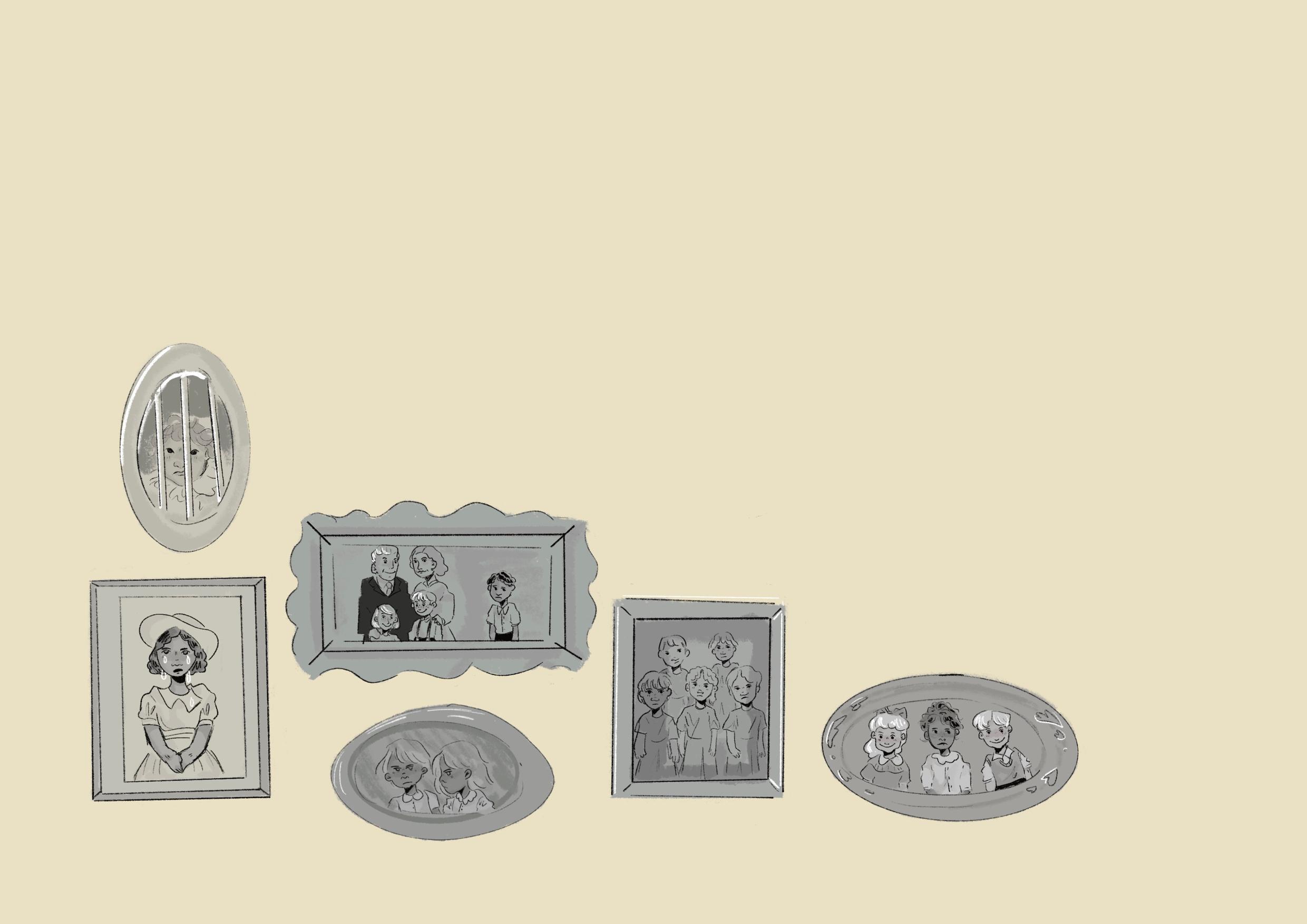

Today, Native American tribes are yet to recover from many of the trials they have experienced. Living in ill-maintained reservations, they face a cycle of poverty and vulnerability that is almost impossible to overcome. This is in large part due to their lack of control of their own land. Much of the reservation land is owned by the federal government, despite the sovereignty of the tribes. In addition, the majority of the land is shared among the people in the tribe, meaning that there are little to no private property rights. This is due to the communal culture and way of life that Indians have practised for hundreds of years. However, because of the setup of the legal structure, the implications of this can be extremely harmful. The lack of land ownership makes it difficult for Indians

Navajo Indian Reservation

Navajo Indian Reservation

to improve their standard of living by developing their land and homes. It also hinders them from simple privileges such as investment in or inheritance of their lands. The current legal framework makes it extremely difficult for Native Americans to overcome these challenges, leaving Indian tribes as some of the most impoverished demographics in America today.

Theissue,today:Australia

Government action:

ByEujinyChoGovernment action on the issue has been overall stagnant and tokenistic. It took four decades before a formal apology was delivered by Parliament, with a string of conservative prime ministers stating they ‘should not be required to accept guilt and blame for past actions and policies.’ Ironically, however, the apology in 2008 (widely known as the ‘Sorry Speech’) was not accompanied by improvements in social outcomes for Indigenous communities; but rather, a significant worsening in many rural areas The ‘Intervention’ program of 2007 to supposedly reduce levels of child abuse in Indigenous communities has only reduced people’s control of their lives and led to detrimental psychological impacts, concerningly harkening back to paternalist ideals through restrictions on welfare payments, invasive medical checks of children, revoking of Indigenous-owned land, and the establishment of armed police and soldiers in communities Additionally, the ‘Closing the Gap’ initiative of 2008 has similarly been compromised by sluggishness and poor leadership - whilst levels of Indigenous education are on track to meeting targets, child sex abuse, alcohol-related violence, and assault have only increased since.

Theissue,today:Australia

Ongoing disadvantage:

ByEujinyChoThe Stolen Generation has had a severe impact on both its members and their descendants. Those individuals sent to missions and children’s homes - exposed to brutal conditions, severed from their culture and identity and denied a proper education or care - experience significant rates of incarceration, violence, substance abuse, and lower general health. However, for the approximate 1 in 3 Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people who are descended from the Stolen Generation, psychological and mental impacts from the harrowing period still continue to trickle down in cycles of intergenerational trauma. The original trauma of the Stolen Generation - the lack of nurturing and high levels of abuse experienced, the aversion to and distrust of the government that formed, and the disconnection with culture and community - manifests and is inherited via abuseful and neglectful parenting practices, violence, and harmful substance use, creating and reinforcing a vicious cycle of stress and trauma Today, descendants of the Stolen Generation are 50% more likely to be arrested and 15% more likely to have substance abuse than their non-Indigenous counterparts. Without adequate recognition of these ongoing issues or support of affected communities, this cycle will only go on being exacerbated and intensified.

Education:

As with government action, education on the Stolen Generation is on the whole also insufficient and tokenistic. Primary school is dominated by glorified colonial narratives, with the ‘great journeys of exploration’ mandated in the national curriculum focusing heavily on Australia’s early settlement history, European exploration and problematic figures such as Captain Cook. Indigenous history, culture and trauma is almost completely obscured. However, whilst senior curriculums include aspects of the Stolen Generation, they have been criticised as too tokenistic and brief, leaving teachers with insufficient knowledge. According to a study by The Conversation Australia, many teachers treat the curriculum as something of a ‘tick-box’ - something to ‘[skim] the surface’ of - as ‘they don’t wish to offend’ Indigenous communities. In turn, Indigenous students expressed disappointment in the stark ignorance of their teachers; with some even describing how content taught in the classroom is ‘[copied] from the Internet’ and ultimately ‘racist.’ Thus a cycle is created where teachers who are denied a sufficient education of their country’s history transfer this lack of knowledge to future generations.

Theissue,today:Australia

Ongoing cultural genocides:

Cultural genocide has always lacked a clear and accepted definition. For this reason, it is not defined as a crime under international law. In addition, the international attention span is naturally limited and tends to focus on the abundant atrocities that can be quantified by death tolls - such as that of the Rohingya in Myanmar. Due to this lack of attention, concern or precedent it is not surprising that cultural genocides are still rife today, with nations exploiting their ability to be concealed and obfuscated by murky international law Perhaps the most prominent example is the cultural genocide of the Uyghur muslims, a Turkic minority in China’s Xinjiang province. The detainment of individuals in ‘political re-education camps’ in an attempt to reshape their identities and religious beliefs, the bans on Uyghur language instruction in schools, the razing of mosques, and the restrictions on signifiers of cultural identity such as hair, dress and names all point to cultural genocide - yet international uproar is concerningly quiet and collective action by the global community has not been taken

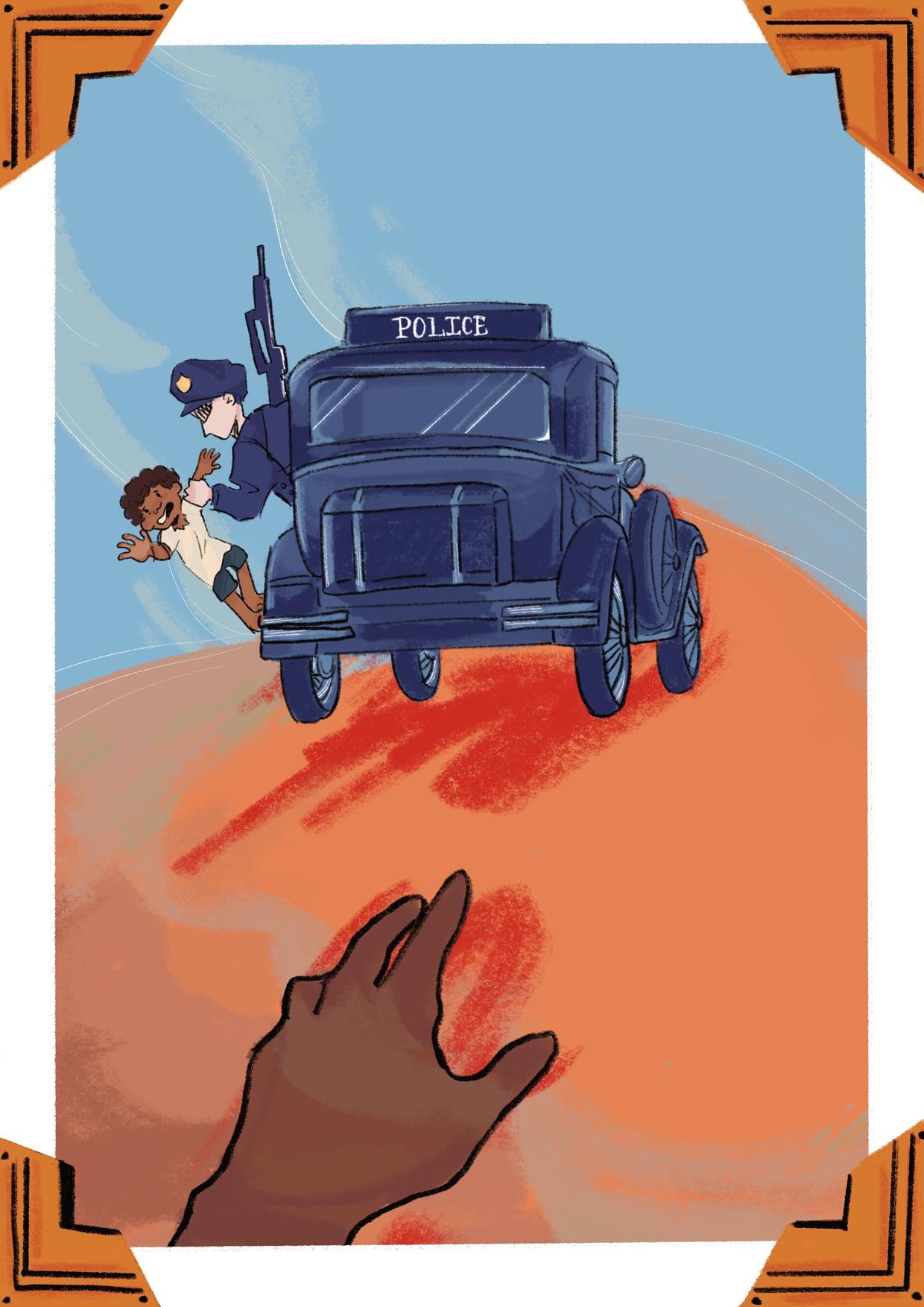

ANewStolenGeneration:theEpidemic

ofIndigenousIncarceration

It almost feels as if you are watching a horror movie. Grainy footage reveals two boysseemingly harmlessly - playing a card game. A few minutes pass, and they are suddenly gasping for air, crying, bending over their toilets, trembling beneath their mattresses. In another room, a boy repeatedly smashes the wall of his cell as gas surrounds him. Outside the cells, prison staff can be heard mocking him, calling him ‘an idiot’ and ‘little f****r.’ Moments later he is dragged out of the cell, hooded and shackled to a chair.

But this is not a horror movie It is CCTV footage from the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in Australia that shows the tear-gassing of six boys. This is, however, not an isolated incident. The overrepresentation and brutal treatment of Indigenous children in the criminal justice system is damning evidence that we have never really progressed past the atrocities of the Stolen Generation.

In Australia, the most overwhelming factor that rubs Indigenous children up against the criminal justice system is ongoing historical disadvantage. From the dispossession and forced poverty that was a byproduct of British invasion, to the intergenerational trauma, repression of culture and social exclusion inherited from the Stolen Generation, this disadvantage is a huge reason why Indigenous children are 18 times more likely to be incarcerated than their non-Indigenous counterparts. In addition to the fact that systemic racism in the courts can land a child in detention for throwing tomato sauce around a residential facility kitchen - shockingly, a real example.

Australian state and federal governments take the much-outdated ‘tough-on-juvenilecrime’ stance; claiming that the unjust and cruel incarceration of Indigenous children is for their benefit But, quite frankly, it’s impossible to buy that act The trauma of being strip-searched, tackled, taken before a court, restrained, beaten, tear gassed - from as young as 10 years old - is never forgotten. Indigenous children are more likely to be charged by police, more likely to be refused bail, and more likely to end up in detention; but they are also 3 times more likely to reoffend and be in adult prison before the age of 21. It is a never ending cycle of trauma and violence.

The criminal justice system does not care at all about ‘protecting’ Indigenous children or ‘building them up.’ Rather, it seeks to break them down. It’s a cruel snare, intended to validate and fuel a 200-year racist myth of a supposedly inherent Indigenous ‘criminality.’

ANewStolenGeneration:theEpidemic ofIndigenousIncarceration

ByEujinyCho

ByEujinyCho

So how can we end the reign of this myth? In the status quo, far too much government funding is thrown at prisons and police, only reinforcing the power of the punitive systems that exacerbate the problem. Several solutions have been suggested by Indigenous communities, though none have been taken up by governments in a meaningful way; raising the age of criminal responsibility, or implementing circle sentencing and healing programs, for example. Justice reinvestment - an approach that diverts funding from prisons to local communities, to address the underlying causes of crime in these areas - seems like a good start

But the most important thing is to empower Indigenous communities. Community leaders and elders must be given a full and uninterrupted platform to resolve disputes, reintegrate offenders, and bring about healing. We must not let harmful, racist, blanket policy stand in their way.

Children forcibly removed from their families, culture and communities at horrifying rates. An institution that claims to ‘protect’ them whilst serving the interests of the racist majority. A vicious, intergenerational cycle of trauma. Sound familiar? This continued incarceration of Indigenous children seems to be a haunting reiteration of the Stolen Generation - a practice that occurred a century ago. Clearly Australia has failed to reflect upon itself. And it is time to do so.

Footage of the abuse that occurs at Don Dale Youth Detention CentreMediaReferrals

ByRachelLaoStolen - Jane Harrison

TW: Infrequent coarse language, themes of racial violence, and intergenerational trauma.

Play/book

Five Indigenous children watch, captivated, as Sandy tells them about the desert. Playfully, they re-enact the rocks being crumbled by the wind Later, Sandy finishes the story alone.

‘The women… would shove sand inside themselves… to stop the men from raping them. My mother called me Sandy anyway.’

Stolen follows five characters. Anne is adopted for her pale complexion; Sandy is on the run; Ruby has been abused her whole life; Jimmy is a rebel against the system; Shirley was stolen and watches her children being stolen too.

Muruwari playwright Jane Harrison stages the effects of being stolen, which are still felt today

Stolen can be found here.

The Visitors - Jane Harrison (2019)

TW: Infrequent coarse language, themes of racial violence, and intergenerational trauma

Play

‘Visitors leave, right?’

MediaReferrals

ByRachelLaoIt’s January 1788. Unusual, foreign ships dot the coast of Gadigal land. Ships that approach, slowly but surely. Seven Clan Leaders gather to decide - should these strangers be welcomed? Or are they cause for alarm?

Jane Harrison’s play changed history. In The Visitors, Harrison illuminates the reality of that fateful day the First Fleet washed upon Indigenous soil.

The Visitors is showing at the Sydney Theatre Company in 2023 The show is directed by Quandamooka man, Wesley Enoch, who also directed the first production of Stolen in 1998.

The Lessons of Maralinga - Liz Tynan (2016) Podcast

Between 1956 and 1963, the British military dropped seven bombs on Maralinga to test their nuclear technology. One of these bombs was twice the size of Hiroshima’s. In the process, the Maralinga Tjarutja people were forcibly evicted from their land.

Before 1978, no one knew about it. And, it was only in 2009 that the Maralinga people received the rights to their land.

Dr Liz Tynan uncovers the story of Maralinga and the secrecy around it. A link to the podcast can be found here.

Aboriginal Australia - Jack Davis (1977) Poem

‘Now you primply say you’re justified And sing of a nation’s glory, But I think of a people crucifiedThe real Australian story’

Jack Davis is a renowned Noongar playwright, poet and activist. Aboriginal Australia (also known as To the Others) shows ‘a truthful and unfiltered portrayal’ of cultural genocide in urban Australia. It exposes how European colonisers reached out as friends and

MediaReferrals

ByRachelLaoproceeded to deny them Indigenous Australians their culture, land and freedom. A copy of Aboriginal Australia can be found here.

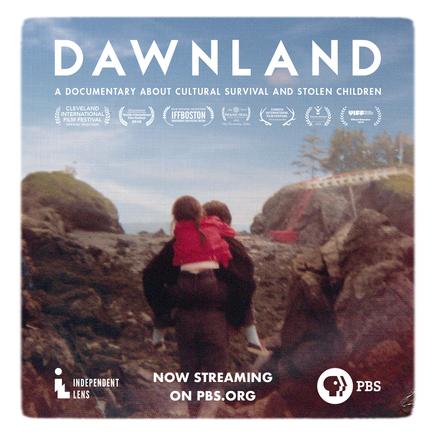

Dawnland - Adam Mazo, Ben Pender-Cudlip (2018)Documentary

During the 20th century, the US government forced Native American children into foster care, adoptive homes or boarding schools. The documentary shares the story of the Wabanaki children who experienced the abuse of their families who coerced them to give up their cultural and family ties. The film centres around the Maine governmentsanctioned Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which collected the stories from the Wavanakie families affected by the policy,

Dawnland has been widely acclaimed, winning an Emmy for ‘Outstanding Research’ in 2019. Rent or purchase Dawnland here.

Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools - PBS (2016)

Documentary

The saying, “Kill the Indian, save the Man”, was the beating heart of the American boarding school system until the 1970s. These institutions imposed assimilation on children who were taken from their families. The Indigenous children were put in military uniforms and forced to learn and speak english. Any rebellion would be punished with

MediaReferrals

ByRachelLaophysical or sexual abuse.

Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools investigates the brutality of these boarding schools. The documentary is in two parts, which can be viewed here.

Our Sisters in Spirit - Nick Printup (2018)

Documentary

Our Sisters in Spirit centres around the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) epidemic. According to the FBI’s National Crime Information Centre, only 0.8% of the US population consists of Native Americans, yet 1.8% of missing persons cases are Indigenous. Systemic violence and discrimination against Indigenous women and girls has led to many unsolved missing or murder cases.

In his documentary, Nick Printup calls for a national inquiry into these cases. Our Sisters In Spirit can be found here.

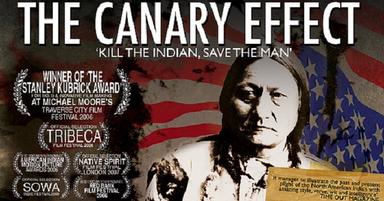

The Canary Effect - Robin Davey (2006) Movie

The Canary Effect explores the many government policies that have negatively affected Native American people. Director, Robin Davey, exposes the media’s refusal to report on Indigenous affairs including the Columbine-style school shootings among Indigenous youth as well as the economic marginalisation of these communities that is ongoing until today.

A copy of The Canary Effect can be found here.

Raysofhope

ByEujinyChoThe atrocity of Indigenous cultural genocides - and particularly, the removal of childrenis a dark chapter of history. Since its occurrence, it has been severely undertaught and still remains an obscure part of our international consciousness. However, there is much to be hopeful about! Across the world, amazing individuals and organisations are tirelessly working towards healing and justice for the communities who were affected…

Organisations / charities

Amnesty Australia: through publishing reports and in-depth coverage on ongoing Indigenous issues, such as youth incarceration and police brutality, the Australian branch of the international organisation draws attention to human rights abuses that are actively condoned under racist institutions. Key campaigns, like the ‘Raise the Age’ coalition, have successfully generated pressure on governments via petitions, letters and strong youth movements. In fact, as a result of ‘Raise the Age,’ the state government of ACT in Australia has pledged to raise the age of criminal responsibility to lower Indigenous incarceration.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS): founded in 2012, this organisation seeks justice and healing for the communities affected by Indian boarding schools. Their website features a comprehensive database of research and information that goes well beyond the detail of our newsletter. Additionally, NABS engages in meaningful activism work, including: the repatriation of children buried at Carlisle School to their families; and advocacy for a Congressional Commission to bring together survivors, tribal representatives and experts and record their stories.

Raise the Age Campaign

Raise the Age Campaign

Raysofhope

ByEujinyChoCoota Girls Aboriginal Corporation: where there was once a domestic training institution for Indigenous Australian girls taken from their families is now the office for the Coota Girls Aboriginal Corporation - founded in 2013 by former residents of Cootamundra Girls’ Home. Now run by survivors and their descendants, this organisation directly addresses the trauma of the Stolen Generations and the healing needs of survivors Its work involves establishing healing programs, sharing the stories of survivors, reconnecting survivors and their families, and linking survivors to support services.

Tangible action

Reports: In Australia, the ‘Bringing Them Home’ report of 1997 was a pivotal step forward that addressed the nation’s general ignorance of the Stolen Generation - it undertook extensive hearings in every capital city and many regional areas and took testimonies from thousands of survivors, ultimately concluding that the Stolen Generation was an ‘act of genocide’ and making recommendations for funding, reparations and official apologies. In America, the more recent Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative of 2022 involved investigations of over 400 boarding schools as well as discussion with local tribes across the country The report explains the laws and policies that allowed for the establishment of these schools and the key institutions involved in running them, as well as the conditions that Indigenous children were forced into; similarly to Bringing Them Home, it also suggests pathways towards justice

Young activists: Dujuan Hoosan, a 15 year-old Arrernte and Garrwa boy from Alice Springs in Australia, experienced frequent brushes with the law in his youth. In 2019, at the age of 12, Hoosan travelled to Geneva and became the youngest person to address the UN Human Rights Council. His speech exposed the glaring issues in his country’s

Raysofhope

youth justice system, and called for Indigenous-led education models - driven by his disappointment in the blatantly Eurocentric version of Australian history taught in his own school. In America, 18 year-old EllaMae Looney is a member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. Her activism is focused on the revitalisation of native languages and is a direct attempt to unwind the decades of assimilation policy imposed on thousands of American Indian children. She works with, surveys and and teaches youth in her own community, and presents her findings to tribal leaders, to reconnect individuals to their culture

Contributors

Writers

Eujiny Cho

Michaela Chen

Rachel Lao

Illustrator

Lola John

Designer

Karina Gunawan