Writer to Writer

a journal by writers, for writers

Editor-in-Chief

Haley Newland

Submissions Chair

Michelle Liao

Social Media Chair

Alexandra Berryman

Art and Design Chair

Harper Johnston

Web Design Chair

Kiran Koul

Editors

Katherine Saunders

Lorenzo Norbis

Jenna Zaidan

Maggie Derby

Riley McComb

Eric Teng

Helena Piacenti Rodriguez

Claire Byrd

Noor Assi

Faculty Advisor

Shelley Manis

Dear reader,

Welcome to the thirteenth edition of Writer to Writer, a literary journal written by writers, for writers, in collaboration with the Sweetland Center for Writing. Through this organization, we aim to foster interdisciplinary creativity across a variety of modes, mediums and genres and to encourage conversation and growth among our community of writers.

In the beginning of the semester, through a series of biweekly creative writing workshops, our members were able to hone both their creative writing and editorial skill sets to further advance as professionals and academics. In early November we teamed up with the Minor in Writing Student Ambassadors to host an Open Mic Night that gave members an opportunity to share their own work or listen to other writers’ work.

In the latter half of the semester, our focus shifted to publication production. The editorial staff met weekly to share ideas, review submissions, and work together to compose the latest edition of our literary journal.

Within this issue, you will find pieces that all touch upon common themes of people trying to situate themselves within the conext of their lives. From struggling with self definition to reconnecting with one’s roots, we hope that you see yourself in this wonderful microcosm of writing and that you enjoy the stories our writers have chosen to share.

As always, our journal strives to celebrate multimodality in writing as well as the individual writing process for different writers with our “Spotlight Interviews.” You can find snippets of these interviews with featured writers in the publication itself, and you can hear the interviews in full by scanning the supplemental QR code to listen on our website.

Lastly, this journal would not be possible without the generous support of the Sweetland Center for Writing, especially from our wonderful faculty advisor Dr. Shelley Manis. Her incredible mentorship and willingness to help has been critical in the successful operations of our organization and our continuing growth as a young publication. To Shelley, the Sweetland Center for Writing, the contributing writers, and to you, the reader, we are so grateful. Thank you all for your support.

Sincerely,

Haley Newland Editor-in-Chief Writer to Writer

First, they shut my eyes

Maci Wilcox

The Joneses

Julian Izac

Speramus Meliora, Resurget Pirus

Joshua Nicholson Water Rose

Eleanor Raygorodsky

Rotting Fruits

Delcene Ralaingita

1

Afternoons Collection: A Windy Afternoon in Barcelona

Yixin Zhang

Buffalo Minotaur

Harper, Johnston

everyone has a god in their head

Megan Ahrens

Dissonance

Anonymous Remainder

Eric Teng

Be Honest, Who Spelled all over my Dictionary

Maci Wilcox

First, they shut my eyes, and I longed to see again. They dressed me in a silky dress like how I once had been. Next I heard the hammered nails and smelt the fresh-cut pine; I meant to yell for help, to rise in the sunshine but flesh-and-blood is weak and frail, so I could only lie.

I heard their voices grim from six feet up-above. Oh oh. Too much. Too much. I wonder what I was.

It’s not the crowd, not winning or the sound of shoveled dirt. It’s not the planet, not spinning: Do I then belong, after all, to the earth?

Next they prayed and then they cried: she cared desperately about what she did.

Do I know what product I’m selling? No. Who are they to kid? Do I know what I’m doing today? No. Perhaps they all forgot I have always been a corpse, I have always held this rot.

Did the soft earth thus turn to steel only to show me my own softness? I loved what I once was.

Not to die, not dying— I once was so alive!

Not to laugh, not lying— I pray to a pinewood sky.

They speak once more: she loved sunflowers and snakes, she loved to run and her loved-ones and she loved to cook and bake. What, are you having a whack attack? Did you think I wouldn’t mind? I loved Black Eyed Susans and the sun and I wanted to be kind.

If I must emerge, haply on the verge of happiness, What will remain of what I was?

It’s not the hunger revealing, it’s not the unmade bed. It’s not the way you view me, or the singing of the dead.

They say the Blood of the Lamb shall wash me clean And I shall heavenly arms enfold; I wish that nature might bring home to me; and save me from this cold; That to fall, not to fly, is in the order of things, that we all are born of stars— There are no sons or sheep or kings, and I may love the human, if only it is seen, thus, from afar.

I hear the mourners shuffle away, and smell the flowered soil. I taste the bitter taste of death: its sickly, stagnant oil. I feel the cold and hollow dark and the splinters of the pine.

I wish to see what I’ve become— if I could only open my eyes.

References

Big Thief. “Not.” Two Hands, 4AD, 2019. Brooks, Gwendolyn. “The Rites for Cousin Vit.” Annie Allen, Harper & Brothers, 1949.

Eliot, T. S. “The Hippopotamus.” Selected Poems, HBJ, 1958, pp. 40–41. Mishima, Yukio. “Sun & Steel”. Burnham Publishing, 2024. Zoolander. Directed by Ben Stiller, Paramount Pictures, 2001.

Julian Izac

spine breaks sternum and breathes against your smooth stone

sunk in vaccinated years, heavy time between the joneses

cracks home runs through the radio eating your laughing sine waves

over dinner, your deli case flank hung, limber and sharpened

fly tape, asks when i am free to meet the joneses

for ranch house conversation, thick american food with highway music

and false teeth holding soccer practice orange slices in bags. that son

turned up like a body, queer and bifurcated in my sick bed—

sorry i transferred my rabbit plasma towards your spit, you stuck

holding those kroger bags, watching me in the floodlight

drag the dawn, split-sky expired air show screams whistle, spire

Joshua Nicholson

There is a pear tree in Detroit that is old and battered and grows no more. And it speaks French, believe it!

A judas encased in bark and squeezed like its darling daughters between the zipping titanium of two major roads.

When the French came to Détroit and took the fur from the land, they brought their sweet seedlings, la poire, to replace what they took.

But only in sets of twelve.

Eleven making an orchard and one, for the crime of betrayal, planted some ways away, as if Judas had found himself cursed to live in the confines of a pear tree.

The tree is nondescript and looks, to all eyes, like nothing but shrubbery, surrounded as it is by evidence of the municipal neglect for gardening services. His skin is cracked by the troubles of time and he has lost some limbs, though yet has enough to point his last arms to the sky. No fruit is born. But Judas prays all the while.

To what! To whom!

To Pan, for absolution?

There are no more pear trees,

Judas finds himself an orphan to the civilizing march of concrete and steel, to the salivating hunger of industry and men. By what right does he hold himself, ancient and firm, in the indelible path of trade and commerce?

If it rains, rough and hard with heavy winds, pungent with the pollutants of his hated city, do they look like tears?

For what reason do you cry, old Judas, for your eleven brothers are centuries gone. Does the pain not heal?

You yourself are lost to the memory of time and must surely join your orchard soon. But yet, you are still here?

What have you seen, Judas, through the rumblings of the surface world on your expansive roots?

Great fires that offered to save your kind; factories built and factories destroyed; railcars passing as fast as the wind? Did you have fear when the riots started, that you’d finally face the axe?

Can you see the flames rising o’er the horizon across the country entire, or is your gaze limited to these straits: Détroit.

Or, grandfather sentinel, are you praying for us?

You who have lived for centuries, but seen countless injuries upon your human sons?

Though we have made a mess of things, and cut your elder soul, your arms are raised for us?

When the money runs dry, and the rivers break their falling banks, and passionate intensity takes hold of men… flee north. Until the cold creeps in. And find the pear tree, bearing fruit again. It has survived for three-hundred years and may live for three-hundred more.

Q: What first inspired you to write this poem?

J.N: So over the summer, one of my friends in my program, she did this thing called a Jane’s walk, but on bikes. So we went around Detroit on bikes, and the final little area, the last place we stopped was at this pear tree that is on the corner of Vernon and Gratiot, and is an empty lot. And so she was telling us the whole story about the pear tree and how there’s only a few left in Michigan. She spent this time trying to find this one, and so we stopped at it in this empty little lot, and learned about how when the French first colonized Detroit, there are stories about how they brought pear trees…They had orchards of pear trees, and they would plant 12, but they’d always keep one planted a little further away from the 11, to represent Judas as they’re doing it, like the disciples. After just hearing that and looking at this tree that has presumably been around since the French first got to Detroit in the area, and kind of just seeing it look very nondescript, just looking very by itself, and I couldn’t even notice it was a pear tree, unless my friend told me…was kind of the inspiration to actually write a little story of this little pear tree.

J.N: I think the idea of this pear tree surviving, you know, from the story that you know we learned about, I think kind of encapsulated a bit of Detroit, from what I know of it and from experience of it. Hence the title, changing the motto of Detroit to, instead of it rising from the ashes, it’s going to rise from a pear tree. This idea that this pear tree has also survived all these things in Detroit, just like the people, it survived riots, it survived industrialization, survived bankruptcy, and survived all these things that probably could have, should have, taken it down. It’s just a single little tree, but it’s still there and is still kind of fighting to survive…

listen to the full interview on our website:

There’s a taste that lingers when teeth sink into the tongue.

Copper and saliva.

Metal and water.

The pain of the wound, and the control of the bite.

And the body will heal, as bodies often do.

The hole will fill.

A callus will form.

The teeth will chew

And the tongue will move

And the mouth will eat.

But there is a taste that lingers when teeth sink into the tongue.

It’s the taste of the strawberries in your lunchbox going sour.

The taste of rotting apples cut for you by your mother.

It’s the taste of hope decaying into adulthood.

When teeth sink into the tongue,

There is copper and saliva.

Metal and water.

The pain of the wound, and the control of the bite.

And it is all the same.

The teeth and the tongue

And the copper and the saliva

And the metal and the water

And the pain and the wound

And the control and the bite

All exist within the mouth.

So there is no choice except for the body to heal. For the hole to fill. For a callus to form.

And the teeth will chew And the tongue will move And the mouth will eat.

But there is a taste that lingers when teeth sink into the tongue.

Julia Abounajm-Housey

1 am, suddenly

I think my arabic is getting worse, and my focus, and my memory. mama, waynik?

lexi texted me, said she is the happiest she’s ever been, I think this is the first time I’ve ever heard that from her, smallah, and nour is once again struggling, burnt out, burned out of caring bas 3ade, you know how it is, and patrick has a new girlfriend, I think the third, I think, how many has that been in two years now? ya allah, at least I am not the only one chasing the sun on earth,

and I can remember all of this but I can’t quite recall why it is that I am here, and how exactly it was how I got here—the days blur again, I remember crimson-gold-vermillion competition in tandem with violet wisps amidst puffs of white—and whether I should remain, whether I remembered to write all the tasks that bind me into my calendar, if I can trust my mind enough for that without Disappointment rearing her heavy head yet again, whether I am any more reinforced than the paper-mâchéd mess of a first grader’s fallen-over art project and yes, I’ve tried the supplements with their sickly-sweet cherry

blistering on my tongue, the false confidence as strong-held as gas station mascara and the self-compliments that age like the day I have tried so many things, you see, and I fear I feel it all will just—

shou? sorry, what?

oh, no, yes, I’m fine. this happens some times, you see, when I am low on sleep. I can’t quite recall the last proper nine-hour night, you see, and I think I have lost the delicately murderous eloquence I so pride myself on, my way with words wasting away, a trickling stream turned bloodred in the setting sun, clarity and insanity’s triplet come undone for you see I always get like this when I am

worsening, always worsening, the static in my mind becoming so much so as I age and my rage never subsides, rou7e, 3amilleh ma3rouf, I’m sorry to say it this way but my time is slipping through my fingers and I

can’t quite catch! up in time to slow down it all and—

hmm?

what’s that you asked? oh, no, those cracks have been there for a while. khallas, they’re not new. so have the ones in my ceiling, up in that corner above my bed, see? and the ash-grey ones sneaking across the paint on the wall below

my desk like hairline fractures, and the dead-skin dust gathering like a blanket on the folded socks strewn in the corner next to the posters I meant to put up last september, sitting still in their mismatched, color-clashed wooden frames.

I have lost something I cannot recall anymore. don’t you see? the sun is setting too fast again.

Translations (Lebanese Arabic): mama, waynik? = Mama, where are you? smallah = lit. “In the name of God,” a phrase for when something good happens bas 3ade = But oh well/but who cares?/but it is what it is ya allah = lit. “Oh (my) God,” used sarcastically or in frustration shou = what?

rou7e, 3amilleh ma3rouf = Go, please khallas = it’s done/enough

The number ‘7’ denotes a guttural “H” sound.

The number ‘3’ denotes the Arabic letter ع, for which English has no equivalent sound.

“Now, my friend, let us smoke together so that there may be only good between us,” said Nicholas Black Elk, (according to the poet and author of Black Elk Speaks, John G. Neihardt) after performing the first half of a Lakota ceremony, which includes smoking a pipe, and is thought to bind two men “together forever in an amicable relationship.” Black Elk provides a crash course in Lakota spirituality by describing the pipe and its symbolically significant adornments: four ribbons of black, white, red and yellow respectively representing the four quarters of the earth and an eagle feather representing the “father” spirit of the sky hung from it and its mouthpiece was wrapped in bison hide, representing the “mother” spirit of the earth.

About a month ago, I went to a Halloween party and smoked two American Spirit cigarettes, whose box features the silhouette of a non-specifically Native American man wearing a headdress and smoking a pipe with a feather hanging from it. I got them from my roommate/high school best friend, who was dressed as a cowgirl.

It’s around 11 PM. I can smell weed and wood burning, I can sense a winding down, kinetic energy siphoned by the cold, replaced with thermal energy absorbed from the fire. The little factions that had formed have dispersed and recombined into one blob surrounding the pit, some standing, some reclined in the splinter-y lawn chairs. I know every face I can see, even costumed, though some better than others. Some I can recall in six or seven different iterations, at least one for each year since I’ve met them. I’ve mentally catalogued different haircuts and colors, teeth with braces and then without, cheeks slim then fat, or the reverse.

There is one in particular that I know embarrassingly well, a face

that might materialize were you to ask some internet database what a Midwestern person looked like. He was dressed as Marty McFly, and his decidedly brown hair, which some (white) people would inexplicably call blonde, was cut neatly for once, though he had shaved his round face somewhat sloppily. I avoided his Tiffany blue eyes, but when I could catch it, I checked to see if his impossibly straight, (previously braced) white smile was as disarming as I remember. It was.

I know all these faces, but not so well in this context. In fact, I remember most of them under the yellow-y fluorescent lights of a classroom, or under the searing white lights of the football field up on their poles like fallen stars against the black sky, with their mouths fixed around silver brass or black plastic mouthpieces. Here, the light is sparse and soft, and mouths casually grip bottles of beer or the ends of blunts or THC pens. There is no urgency in the air, no musical phrases to learn, no posture to correct. Like one rarely could in a marching band rehearsal, I can hear the conversation veering into that familiar, juvenile, teasing tone which was the foundation of those tender school-age bonds that I had mostly opted out of. Apparently, I still wasn’t ready to participate in that kind of conversation.

“Wait, wait, wait, let’s play Never Have I Ever, Bea included,” slurs Lesbian Justin Bieber.

At that cue, I pretend to check the time on my phone, make a face, and get up. There’s a dull roar of protests, to which I just look back and smile and shake my head.

Inside, I find Cowgirl, and thank God, the rest of our group are ready to go. Cowgirl’s boyfriend Cowboy, who had been napping after having thrown up all the chili, beer and liquor he’d had that night, hands me the car key drowsily. Before leaving, we shuffle through the real adults back out to the fire pit so that Cowgirl can say goodbye to her sister Delores from Beetlejuice. We both hug Delores, and Cowgirl talks to Marty McFly for a second, but

I just kind of hover, because what would me saying goodbye to him in particular mean?

The cold bites us on the way down the driveway to the front lawn, where Cowgirl’s car is parked. Though I’m designated driver, and the only one sober (Cat, a friend of a friend from college, doesn’t drink, but she did smoke some weed and she’s a horrific driver), Cowgirl is the only one who can pull out of the lawn without causing at least $2000 in damage to someone else’s car, even tipsy.

I am the only one sober, but the cigarettes were my one indulgence. Actually, if I count the two I shared with other people as halves, one single cigarette. (I know when to stop.) The first, I shared with the hostess, Jack (of Jack and Coke), and the second with Black Bunny. Black Bunny and I were standing in a little group with Lesbian Justin Bieber, who I had just told that I don’t really smoke much, and who said “I feel like she’s lying to me, she just said she doesn’t smoke!” when she first saw me with the cigarette, and Marty McFly, who, though he’d been vaping nicotine and taking hits from a cart for the past hour, turned up his nose at cigarette smoking. I’m not one to argue, especially not with him, but I teased him a bit with Cowgirl, away from whom he had dramatically ducked in mock disgust when she tried to get her cigarette near his mouth, laughing, “Come on! Come on!” as he swatted at her.

“I don’t give a fuck, man, that shit is naaasty,” Marty said, with extreme nasalization on the last word. Looking at him in annoyed affection, I felt a pang in my chest that I hadn’t felt in years.

As much as I wanted to repress it, as many times I had lied about it, and as hard as I had felt my heart beat against my ribs when I heard his name, I knew I would always feel some type of way about him. Definitively labeling that feeling would be an admission I’m not ready to make. So I will continue to dance around it, to keep on just missing it like I would his gaze; I’d hold my head

straight and stare at him out of the corners of my eyes, but at the first hint of movement toward me, a miniscule tilt of the chin, a slight raise of the brow, a twinkle of the eye, I’d dart my eyes forward right away. But in the same breath I’d convince myself, and maybe I was right, that he held me in his vision for a few seconds after I’d looked away. I think in that interaction, which had many clones over the years, laid the nature of the attraction. Wanting to be looked at, but never to be seen actually looking.

I guess it tracks, then, that the closest I ever felt to him, the most I ever felt for him, was when we played music together. I couldn’t see him, he couldn’t see me, we were always about a foot apart, and yet we were touching. Our eyes slid across the very same page in sync, our fingers performed the same patterns, our lips locked not with each other but in the same position on two identical mouthpieces, our tongues slapped against our reeds in time with each other, methodically stopping and starting the flow our air, and our breath flew through the bells of our horns at matching speeds, vibrating the instruments and creating waves which swam through the air to sweetly kiss our eardrums.

Maybe it was also notable that in those moments he couldn’t talk, because as I was reminded that night, he always managed to say something stupid in some stupid joke accent that would spoil my glossy, romanticized memory of him and put in its place the rough reality in front of me. My already reluctant affection for him would sink beneath the shame which kept that affection from ever coming to the surface and which stopped me from even beginning to entertain the idea of playing Never Have I Ever. And out of that shame would come a mean sense of superiority, just as immature as the affection.

This meanness sprung to life in me when Marty put on his little performance of avoiding the cigarette Cowgirl jokingly shoved in his face. I started to think of him as a big baby throwing a tantrum: his big pink face crumpled in dismay, his arms splayed apart wildly, the cigarette a spoonful of food and the sleek, plastic vape

his pacifier. Somehow, in my head, I had managed to put myself on a pedestal for one of the most universally disliked habits ever. Somehow I was more grown up or down to earth or refined for taking my vice in a more “natural form.” Somehow I had “beat the system” by not succumbing to the ease and novelty of e-cigarettes and sticking to the “real thing.”

But in all honesty, my little habit was no less a product of insidiously strategic marketing than his was. The blueberry flavored vapor from his mouth polluted the air around us just the same as the tobacco smoke from mine did. The dangerously opaque technology of his mass-produced vice was no more a signal of the rotten spirit of American consumerism than the faceless, headdressed Native American man on Cowgirl’s box of cigarettes.

And anyway, we were both reaching for the same thing. We would never say it, but we wanted some sort of communion, for our mouths to have touched the same thing, in some ritualistic motion. We should really have been smoking from a pipe. Something like Black Elk described, with ancient, human meaning, maybe kept away in a specially carved case rather than thrown haphazardly into a pocket, or rescued from the ground or, God forbid, fished out of the trash.

Maybe sharing those cigarettes just felt as close to that as I could get. He probably wasn’t even thinking about it like that, just chasing a feeling in the dark. Maybe if I explained it to him this way, he’d try it for me. Maybe we’d get somewhere close to that place we were in a few years ago: our mouths, though completely parallel, locked in the same rhythm.

Maybe I should just quit smoking and kiss someone.

14, 13, 12

The red numbers on the cross walk make their way to zero 11, 10, 9

but I have been taught that red means stop Behave, listen to instructions

8, 7, 6

So never do my Converse even step onto the street if the little white man isn’t lit to tell me “Go.”

5, 4, 3

Almost to zero, a bus on either side and even then some people still continue with their stride

2, 1, 0

I’m still waiting for my “Go.” and a stampede surrounds me strangers, students some people

To them that crosswalk is a runway and for my people, the maíz in this maize, it’s a ladder sweating not strutting screaming and shoving

Just to not get left behind at the bottom of this climb

But to exist on the sidewalks of this city is a victory Some people follow legacies I get to make mine everyday And when I look up from the floor I’ve been so friendly with

I hope some people say “You’re welcome here, you’re here to stay. Take up space as you please” But I haven’t gotten that reassurance, it’s already crossed the street

Every door I open on this campus opens one back at home For my mother, for my children

Some people though Must’ve never been taught to hold the door And it shuts in my face

What am I doing here?

What am I doing wrong?

What do some people need to see from me to make me feel like I belong?

Don’t get too close It’s contagious

I don’t mean to ruin all your fun imposter syndrome in my veins, it keeps me guarded and alert Find brown in this blue crowd

This shit is nothing like the brochures I don’t know the brand of your navy tote bag or why you all have one and I don’t know what Pike or Fiji stands for I don’t know why your last names make me feel like mine’s a mouthful But I know I feel so small here, I’ve never been one to ignore The way some people change my energy, to no fault of their own These observations aren’t hatred, just a comfort I’ve outgrown

But you don’t know what it’s like to be a single digit percentage of a school you give one hundred to You don’t know what it means to take Spanish because you owe it to your history

And you don’t know why you get honked at when you cross Geddes avenue

I can’t pretend like I’ve adjusted, like everything’s just fine

Like I’m not shocked when in every classroom there’s no skin that looks like mine

And some people never feel that, at every table there’s a chair And I envy their confidence to take it, I pull up one for me elsewhere

And when I walk back to my dorm, and the end of a long day I wait to cross, until the little white man tells me that it’s okay

Yixin Zhang

William Cody’s daddy was an abolitionist who never backed down from a fight. In the end, the fight got him first—stabbed twice in the side with a Bowie knife. At 11, William buried his father and put on his boots: well-worn but loose enough that water pooled up at William’s feet every time a drought broke. He had been on his way to warn his daddy of the plot, rode 30 miles delirious with fever and still too late. He was on time to see his daddy cut open at the side like a choice cow, his unblinking glass eyes staring up at the sun.

James Hickok’s daddy was sick before he was born. Something in his lungs, they said, leftover grief stuck to the sides of his ribcage. When he died, James took the leather holster gently from his fathers hip and fastened it around his own. He keeps it close but empty, waiting for a weapon, and starts introducing himself by his father’s name. Hickok’s real name stays close to him, given to a select few who he tries to stay alive for. At 18, Bill nearly drowns in a canal in Illinois. His arms around the enemy, both fall into the water and both emerge thinking they’ve killed a boy. Bill washes his face in the river, touches his empty holster, and looks for another fight.

Before “Buffalo” Bill and “Wild” Bill, the boys were just William and James. William Cody, at 12, a “boy extra” riding the length of a wagon train, delivering the messages which connected end to beginning. The other, Bill Hickok, 18, has nightmares of his lungs filling with water. He joins the Jayhawkers to drown out his father’s voice in the wind. The first time they meet, it’s transactional. Clean. Simple. Like the sharp movement of air around a bullet. Bill Cody hands Bill Hickok a package wrapped neatly in brown paper, tied off with twine. “For James.” Something about the older boy compels Cody to stay and watch him open it. Slowly, deli-

cately, with long, gentle fingers, Hickok peels back the creature’s skin to reveal two beating hearts. A pair of Colt 1851 Navy Model cap-and-ball revolvers, with ivory grips and nickel plating. The sun reflects into Hickok’s eye. Both boys flinch.

The second time and the times after that were at Fort Leavenworth. James Hickok is “Wild Bill” Hickok now, a name he gave himself after his first shootout in Springfield. Bill Cody worked as a scout in Johnston’s army, throwing himself at every soldier in grey, the men who killed his daddy. Wild Bill sees the manic glint in his eye, the way he doesn’t look before shooting, and wants to know why. The two find each other again, the last outside around the campfire, slowly emptying another bottle of beer. It starts to come out then—how Cody doesn’t know what he’ll do when the war ends, there will be no place to go for him again he’ll be adrift in the prairie without a cause. Hickok laughs and says adrift in the prairie isn’t the worst place to be, look, they wouldn’t have met otherwise. They fall silent and the campfire is loud. Cody says he hears Hickok is a good shot, he laughs and says “I can teach you, if you’d like.”

The two boys get up and, in the dark, Wild Bill Hickok shoots a beer bottle off a fence post from 50 yards. He stands behind Cody and guides his arm until he hits just below the bottle, leaving a hole in the fence. “Here, keep practicing.” Cody feels the warmth of Wild Bill’s hand and the Colt 1851 revolver pressing against his palm. They meet every night until Wild Bill is made marshal of Abilene.

Some say Bill Cody killed 4,282 Buffalo in eighteen months. Nobody can tell how many it truly was. He’d polish his Springfield Model 1866 rifle, Lucretia Borgia, like he was holding his firstborn son. Lucretia was the last thing many a bison saw. The sun bouncing off her silver surface, only a glint in its tired brown eyes before the near-silent whistle of a bullet connected with its skull. The Kansas Pacific Railroad paid Bill handsomely too, gave him a place to stay and a little pocket change to sustain his legend-making.

When there are no Buffalo left to kill, Buffalo Bill needs another way to keep moving, to make a quick buck without thinking. He dreams up a variety show, and knows who he needs to make this picture complete—the famed outlaw sheriff, the best sharp shooter, whose stoic exterior, wild black hair, and deep brown eyes have become a widespread legend. Buffalo Bill strolls into Abeline, the spurs on his boots jangling, and comes to the marshal’s office with a question. “James, how’d you like to be in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West?”

Wild Bill Hickok gets up from his chair, hugs his old friend, and grabs his Colt from the desk drawer.

The two perform together, for a time, trading shots and jabs as naturally as waltz partners. They are dazzling. It doesn’t last long. The lights hurt Hickok’s eyes, and he starts to get headaches, and Buffalo Bill’s star begins to eclipse the young boy who delivered messages to Fort Leavenworth. Wild Bill has to leave, but he promises to come see the show the next time he’s in town. In South Dakota, he’s shot in the back of the head during a game of poker. His hand falls onto the table and the cards face up in two pairs—black eights and black aces. The first telegraph goes out to William Cody.

After the show, Bill lies for a long time on the floor with the ends of his hair draped in the wash tub. He sinks lower, until the water covers everything but his nose. He closes his eyes, and holds his breath and prays to a God, who has never cared before, that maybe James could live in place of him. That there was some way to bring him back. Above the water nothing has changed. They bring his casket to Bill. He wanted to be buried at Fort Leavenworth. For Cody, he leaves one Colt revolver with the initials J.B.H carved in the backstrap.

There is, apparently, no other god damned place to keep the body other than Buffalo Bill’s dressing room. He gets up, walks over to him, touches the lid, thinks better of it, sits back down, stands up, pours a glass of his whiskey from the locked cabinet, swallows. His dreams are filled with James. They are swimming in the creek out-

side of camp on a warm day in August. A bullet grazes Bill and in the medical tent James is there to patch him up, scolding his recklessness. They are lying on their backs in the tall grass, looking up at the night sky, imagining a world where they didn’t need to fight. He wakes in a hot sweat.

The first thing Bill notices is the empty mount, the wood strangely discolored in the absence of his taxidermied Buffalo head. The lid to the casket is open on its hinges. Something is breathing erratically in the corner of his room like a prisoner of war. It has James’s frame, but the bullet wound in his head has been replaced by coiled brown fur and two short black horns. The creature turns around and all Bill can do is stare. Its deep brown eyes stare back, unreadable. Buffalo Bill cannot scream and neither can his creation.

What is there to do other than to cage the animal? Though it has Wild Bill’s body, it is not human enough to inspire anything more than morbid, curious horror. How else can Bill explain what has happened than to chalk it up to magic—a new act for the show, a Buffalo calf brought to life by some ancient ritual. To keep the thing locked up is an act of charity. In its cage, the creature sits in the corner cross-legged, and looks at the wall. It turns around when Bill enters, compelled by habit to respond to the sound of his voice, his smell in the room. They train, as the two bodies used to, side by side, but Bill knows he has killed this animal before and it may be kinder to the man to kill him again. But, there is money to be made in the uncomfortable wrongness of the creature’s existence. Their act is billed as “Buffalo Bill and his Minotaur.”

On opening night, the Colt revolver fires into the air. Bill takes aim, not at the target but at James’s reanimated heart. He hesitates. Suddenly, the creature lunges forward. The audience gasps, delighted. The sharp point of its horn sears across Buffalo Bill’s stomach like a Bowie knife. He falls to the ground, blood falls onto the initials J.B.H. Nobody moves to stop the creature or to help Bill. Either way.

everyone has a god in their head

everyone has a god in their head and voices are nothing without the bodies behind them, a clattering of sonic particles echoing vibrations between vocal folds

yes, everyone has a god but my god is better than most, just by a little bit

her pettiness comes out when i rise sharply at dawn to swirl mint toothpaste around my mouth then send a postcard advertising my good deeds when i was younger, i thought my grit could take me anywhere, believed if i paid with the pencil graphite on the back of my hand i would get what i deserved, desired. i played the game, your game like my character was currency

for happiness till you taught me it doesn’t work like that in nature. the hawk will still circle and kill the mouse whether or not the mouse was good. whether or not i played the game, you still left me standing in the snow

everyone has a god creating mini universes between arteries

when my voice commands the gods think of an apple do you picture it on a table, lonesome or in your hand fingers clutching polished produce the author of your appled fantasy

my best friend showed me poetry was its own type of god and once i learned that it governed me, enraptured me. ars poetica became the altar i built and worshipped at, each completed poem in times new roman a proof of my worthiness

everyone sleeps when the stars come out, and i barrel down the freeway; god-mind propelling me forward while i’m picturing the apple, the altar, the mouse, and you.

if it came down to it and we had to fight using only our gods that is, the words we’ve shapen with our minds i think we both know i would win but this battle will not play out and

i no longer believe everyone has a god in their head

For Aaron Bushnell

“Sweet brother, if I do not sleep

My eyes are flowers for your tomb” -Thomas Merton, “Reported Missing in Action”

Tonight I’m a mass of hearing: eyes agape, breathing in the mind’s dissonance. Waves of electric guitars crash upon my ears— Still, I’d rather this shrill static than my pacing thoughts.

You’d think I grow tired, staring into the deepest blue of the skylight, letting the records repeat, the purring hum of hymnnnn slipping from stereo—I’ve heard this refrain before.

Cobain whispering under the distortion, Charles singing the blues—hell it’s all the same. One song. One God. Around and around and around.

I rise to blow out what’s left of the candle, lingering in my room’s silhouette before I sink, compelled to the floor. Now kneeling by the bed’s foot, prayer slips out all the same, it’s droning—it’s boring me.

The only prayer left is silence. I pray with my eyes, watching the one I want, surveying the sky, self-seeking in mirrors.

But silence is a rare blessing. To watch clouds in their standstill or a painting you don’t quite grasp,

to witness a sleeping child, the branches bending westward, a bedroom’s light turn off for the last time—quiet miracles.

This evening mimics each one before it, thunderous doldrums and all. Memories rewind and replay, delaying sleep. For once, I’d like to be taken gently, to have my sorrow spelled out for me— yet nothing comes save music pregnant with memories.

Turning up The Ronettes, I consider all the boys, beautiful in their youth, who’ve had songs written for them. How they’ve grown to men—balding, abusive, virile, sterile, comfortable—shrunk to their fathers. But they were boys once:

lanky and awkward with pubes peeking out, trembling as the swift hand of desire swept down, passing the boxer brief’s elastic band to the tingling, growing kingdom of life. You’re only that callow ball of hope once. You can only really hand yourself over like that once.

Christ too surrendered Himself, in the ultimate act of filial piety: to humiliation, libel, death—to God. Letting the cup pass willingly, He knew this life to be embarrassingly small—yet still worth saving. He sculpted each soul to scream for salvation, whether crumpled

under a hospital’s rubble or airdropped aid. Tonight, no song could silence 63,000 crying out, begging that their deaths penetrate the hardened hearts of an ambivalent world.

You heard them no better than I, but were compelled all the same to erupt before our eyes. Understood in effigy, you’ve given up the unendurable weight of each day: of each new mangled child and barren-gazed mother.

If I followed in your gasoline-soaked footsteps— if I made myself a votive before the embassy’s gate— could even one life be saved? Would the world stop turning for just one second?

The night fades and dawn’s ochre brush washes over this house while you burn on my mind.

An endless march down the ash-blackened valley

Nerves shot with the beat of every drum

One by one, our friends fell

Buckling under the weight of this terrible now

The Earth thrashed wildly as we crawled through trenches

Its pores seeped masses of flesh and bone

Alone, we pushed forward

Weary mangled spirits breeding blood-crimson flowers

But soon the dust that blinded us soothed our eyes

And the rotting stench turned lightly sweet

And tired feet grew numb

And stumbling over the dead became commonplace

All our bodies, becoming one with the ash

All our souls, creased over and over

Horribly misshapen

Trailing furrows at the bottom of the valley’s depths

One day the rain came and washed the ash away

The air, the trees, the soil glistening

Unrecognizable

We marched in place, waiting, as the sparkling world spun on

Sophia Marr

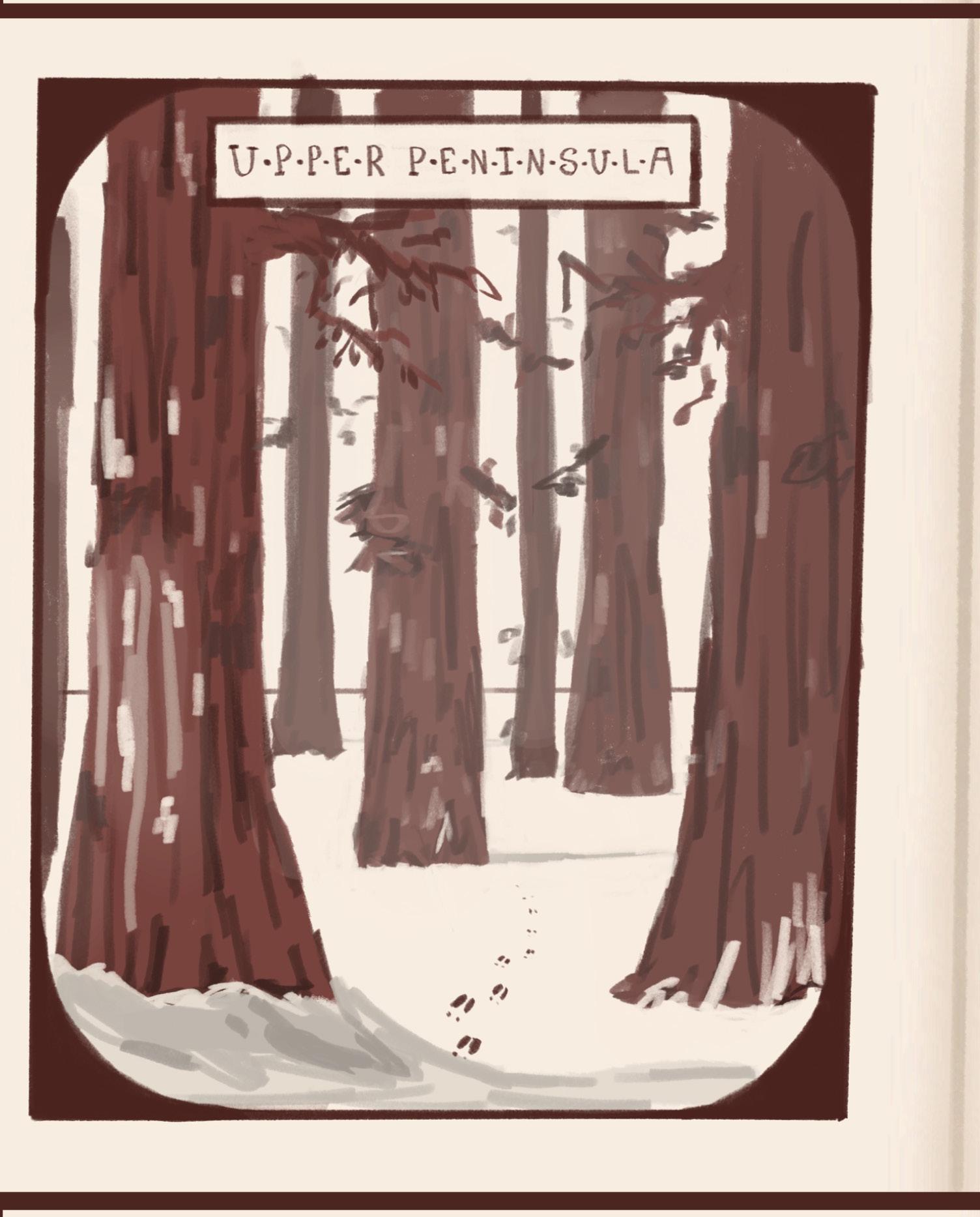

Be honest, Who spelled all over my dictionary

see the piece as one continuous image on our website:

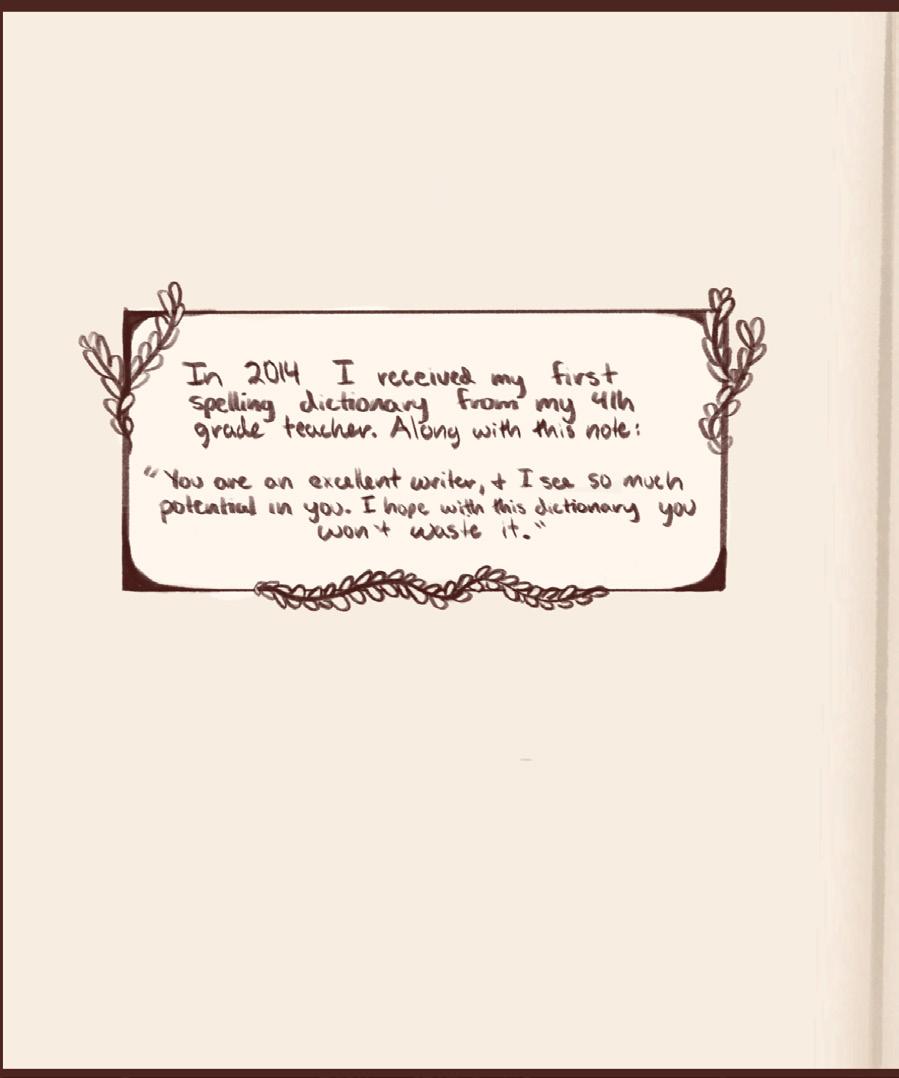

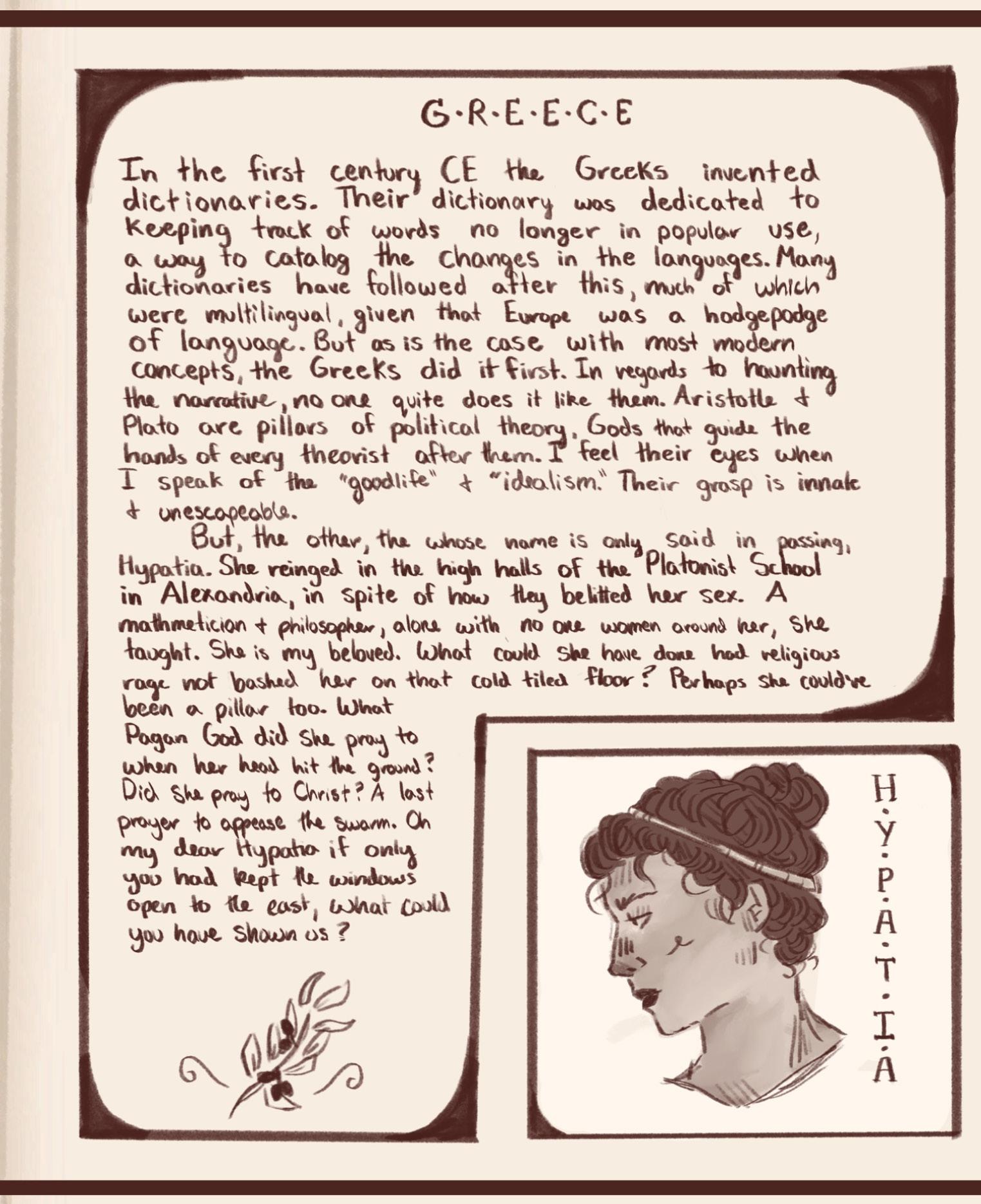

Q: What first inspired you to write/draw “Be Honest, who Spelled All Over my Dictionary?”

S.M: I’m taking English 425 right now, and we’re doing these lyric essays. We had read an essay in class where the author put photos on top of her essay, so it concealed some of it. And I thought, “oh, on my essay, I really want to include some art in it.” And so I ended up handwriting it and then doing the pictures. Also my semester topic was wasted potential, so the first essay is about my dyslexia and my own feelings of like, wasted potential because of that. I also chose to handwrite it because that felt kind of ironic, given the dyslexia. I actually didn’t do any editing, usually I run things through Grammarly, but I didn’t run this through Grammarly so that it kept sort of the Dyslexic nature of it, of me writing it.

Q: What do you think drew you to the act of writing and creating, even when you had these kinds of barriers in place that made it harder for you to express what you wanted to?

S.M: I think for me, it was always when I was younger, I was an insatiable reader, so much so that my parents—I got yelled at for reading too much, they were like, go outside. And I was like, No, I’m reading Narnia. Leave me alone. But I think it was—I think that the world of reading is so interesting. And I reached a point where I was like, even though writing is hard for me, and art is hard for me, it felt like I had to create something. I had consumed so much media that I needed to produce something. And then just keep producing things until I got something that I was happy with, until I produced something that I really liked and enjoyed.

listen to the full interview on our website:

Madeleine Kim

I am told someday I will find my other half; that if I could fold myself in two I would soon and surely find the half of me I have long since been missing. Though I believe that I am whole, perhaps there is an itching to find a half of me in you.

I dream of you and see you unsheathe my inner sword, the one which wards my woes away—but when I find myself floored I find you with a laugh not at me, but at he who pushed me down. You kneel to meet me half way. You must have been so afraid, you say, and I realize it is true. It was there I meant to stay, but once a hand offered me an upwards climb I saw and considered the slope.

It has been easier for me to grope through the darkness than to turn on a light; and though I expected the half of me to come with a lantern to brighten up my flight, you come to dance with me through the night. We become lost in the dark but the darkness feels so light: you lift weights off my shoulders and they ask me to fly through gates to soar over straits so clear my reflection shows you the half of me folded over and blank.

You see the half of me blank to kiss the blank half of you and keep us together like this; you find the half of me which I cannot see lined with paper stars, chocolate bars, and plans of ours we are yet to make—but when I wake from this dream I find my heart to be remiss; with an ache for what I could be if I sought the half of me.

Though I believe that I am whole I dream to see the half of me as I am told to dream it. At the instruction I have folded myself in two searching for half of me in you, though now I search for the key to unlocking my fold and regaining my whole. I do not need someone to match the half of me; for even if half of me is yours, first it was mine—and as mine it has not opened doors and dreamt through wars to see it unfolded again only as it is yours.

But if you can see my whole and are so inclined, I will give you my time so we can live our lives together to whine and wait in line; pick at our aging pores and look through each other’s drawers because we can no longer remember where we stored the half of me or you. We will be bored, of course; but I will do the chores as long as they’re yours. Across the floor I will sweep the worst right out the door as you see my fold reversed and me as the whole I know myself to be.

Dearest,

You’ve reminded me of the moon’s gentle shower, the sea’s calm as it basks in its glow,

You’ve reminded me of the soft dance, guided by an old brass’s croaked laugh. The kindling of an alluring fire, the highlight of a cold night, The wafting scent of brewing tea leaves, welcoming in the quiet. And amidst all the silence, comfortable contemplation, I’ve missed what you’ve reminded me of the most-

The waiting coyote, hiding behind fig leaves, Thinking himself a royal with treasures in his grasp that don’t belong to him. Wearing a cape of deep red velvet to hide the stains, a pointed smile as he bides his time to strike-

Your cunning gaze has taken me; I’ve drowned in your shadow. Yet move along, old coyote, or might you risk the same fate you’ve thought yourself godly enough to give.

Yours truly.