2023 & 2024

Thesis Exhibition Catalogue

lineage

Olivia Gallenberger

Camila Leiva

Nik Nerburn

Hawona Sullivan

Janzen

Delta Passage

Namir Fearce

Whalen Polikoff

Calvin Stalvig

About the University of Minnesota Department of Art MFA Program

Our three-year MFA program places emphasis on the conceptual and material understanding of creative practice and also on the significance of visual art within the broader social and historical contexts in which it is made. Coursework is designed to balance studio time with critical inquiry that takes advantage of the research university environment, while offering full tuition remission.

Our program places major emphasis on creative artistic work of high quality. We promote not only the conceptual and technical education of the professional artist in artistic practice, encouraging critical inquiry, excellence, and an understanding of the history of art, but also an experimental approach toward each medium. Our curriculum covers four main areas of study: Drawing, Painting, & Printmaking; Sculpture & Ceramics; Photography & Moving Images; and Interdisciplinary Art & Social Practice.

MFA students are provided with studio spaces in Regis Center for Art with generous workspaces, natural light, and access to departmental facilities The Regis Center houses state-of-the-art facilities in sculpture, foundry, ceramics, digital fabrication, imaging and editing, printmaking, drawing, painting, photography labs and digital moving image studios, and studios for sound and interdisciplinary collaborations with emerging technologies.

Graduate students are eligible for research funds that support national and international travel. The department has numerous international partnerships and residency programs with peer institutions abroad.

art.umn.edu | 612-625-8096 | artdept@umn.edu

z.umn.edu/artmfa @umn_art @umn_nash

lineage

Olivia Gallenberger

Camila Leiva

Nik Nerburn

Hawona Sullivan Janzen

with writing by

Jessica Lopez Lyman

Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski

Christina Schmid

Delta Passage

Namir Fearce

Whalen Polikoff

Calvin Stalvig

with writing by Nadia DelMedico

Ashley E. Kim Duffey

Douglas Kearney

and essays by

Christine Baeumler

Diane Willow

Jane Blocker

2023 & 2024 MFA Thesis Exhibitions

University of Minnesota Department of Art

Letter from the Chair

Professor Christine Baeumler Chair, University of Minnesota Department of Art

In the fall of 2020, amidst a backdrop of the global pandemic, the tragic police murder of George Floyd, and the powerful expression of collective grief and resistance seen in the Uprising, a new MFA cohort embarked on their graduate school journey here at the University of Minnesota. Three years later, their thesis exhibition in the Katherine E. Nash Gallery showcased the result of artists maturing from within the crucible of history, a group of four people researching, internalizing, and making their own both our cultural lineages and their own familial heritage, in the way that artists do: through their work.

The exhibition Lineage delves into the intricate tapestry of ancestry, offering a multifaceted exploration through compelling imagery, text, objects, and sound installations of stories both personal and political. Lineage explores how these historical threads resonate in the present moment and extend into the future, inviting viewers to contemplate the interconnectedness of past, present, and future.

Each member of the 2023 cohort made work related to their families: Camila Leiva illustrates and catalogues her grandmother’s powerful political activism in Chile. Nik Nerburn delves into a family tragedy that goes three generations back, crafting a world of speculative history and voyeuristic archiving. Olivia Gallenberger finds a direct connection between their studio practice and growing up in their father’s bakery, using touch and material to sculpturally address concerns of the body. And Hawona Sullivan Janzen’s installation is literally wallpapered with images of her ancestors, invoking and embodying their memories and legacies in a mirrored reflection on past and present, complete with a gathering space as welcoming as any family’s living room.

The 2024 cohort, whose experience here was also undeniably impacted by ongoing political and cultural crises, looks back and digs deep to uncover the roots of this present moment. Whalen Polikoff frames contemporary issues within hidden historical antecedents, offering twisted recreations of imagery we may or may not even recognize, from the cowboy chic of Ronald Reagan to Nazi-approved German Romantic Realism to snippets from pop culture and art history. Namir Fearce invokes the long history of anti-Black violence and pro-Black resistance on this continent, creating an immersive atmosphere that draws a line between the Middle Passage, the Mississippi River, the Middle East, the Blues, and contemporary ballroom culture. Calvin Stalvig creates a

ghostly sense of home, where masked spirits watch from the wings and offerings are laid out to honor the ancestors, going all the way back to the Venus of Willendorf. These three artists have personalized these cultural histories, creating not academic studies but visceral responses — work that feels very much lived in and true to these artists as individuals.

Delta Passage serves as a poignant reflection on the complexities of ancestry, traumatic histories, present-day atrocities, and the profound questions surrounding legacy and responsibility in the current era. Through immersive environments, evocative imagery, moving visuals, and resonant soundscapes, the exhibition prompts viewers to consider the kind of ancestors they aspire to be and how the echoes of history continue to shape the present and future.

It’s also a show that would not have happened without the advocacy of the former Director of Graduate Studies, Professor Jenny Schmid, who pushed to accept a graduate cohort in the fall of 2021 as the impact of Covid led many departments to halt admissions to their programs altogether. Professor Diane Willow, the current Director of Graduate Studies (2021-2024) has worked closely with both MFA cohorts, serving as a valued advisor and supportive mentor, creating a much-needed sense of community in the graduate program as we emerged from the social and physical distancing of Covid.

Both exhibitions benefited from the curatorial expertise of Teréz Iacovino, the Assistant Curator at the Katherine E. Nash Gallery. Teréz and a team of dedicated staff and students, which in 2024 included lighting specialists from the Department of Theatre Arts & Dance, assisted the graduate students in realizing these professionally installed and complex installations.

In the face of adversity and uncertainty, both of these exhibitions stand as a testament to the power of making and sharing art to provoke thought, evoke emotion, archive histories, and spark meaningful dialogue. They invite us to confront the past, engage with the present, and envision a future guided by introspection, empathy, and a deep understanding of our shared human experience.

with courage

Professor Diane Willow Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art

Lineage brings Camila Leiva, Hawona Sullivan Janzen, Nik Nerburn, and Olivia Gallenberger into creative relationship as they uplift, utter, unravel, and unearth deeply personal stories of themselves, their families, and their ancestors through re-membered pasts, dreams, and speculative futures. What evolved into Lineage, a thesis exhibition with a shared yet varied focus on kin and kinship, could not have been anticipated when each began. The rhythm of a three-year graduate plan typically recalibrates each artist’s creative process. The start and end dates are predetermined. What transpires is open. Yet none could have imagined, when applying in early 2020, that a global pandemic would ensue, persist throughout these three years, and alter the course of their life experiences and artistic processes.

Theirs is a uniquely charged commitment to artistic development with its acts of courage, leaps of faith, trust in the potential of imagination, embrace of hope and meaning making, and nearly inexhaustible adaptability. Lineage carries the aura of the pandemic and its emergence as a collective, traumatic stressor with its isolation and loneliness, extended state of unknowingness, disorientation, dislocation, and loss.

Camila Leiva grounds herself in the power of the matrilineal: her grandmother and mother. She recognises and cherishes these courageous and loving women and their participation in the Chilean social movements for justice that nurtured her. Passionate about remembering what she describes as the stories below, Camila re-embodies and renders unforgettable the story of her grandmother, the human rights lawyer Fabiola Letelier. She elicits her communicative powers with a graphic novel, polychrome figurines, and the narrative textile form, arpillera.

Nik Nerburn portrays the felt reverberation of his great-grandfather’s tragic actions, as unforgettable as the potato dominating the interior of a domestic space portrayed in his mural-scale, constructed photograph. Within this meticulously rendered tiny room, at the edge of an avalanche of wood shavings, he places two illuminated candles that suggest current day communication with this spirit from the past. He invites us to look, unflinchingly at familial sites of abandonment, absence, and decay.

Olivia Gallenberger opens an intimate and fluid dialogue with clay. Informed by tacit knowledge gleaned from proximity to their father and grandfather shaping dough in the family bakery, they find relief and possibility in the responsiveness of clay. With this medium, this earthy and elemental substance, they call out memories and loss, pain and care, wounds and healing. Soothed by this material receptivity and reciprocated listening, they imagine portals to constellations existing beyond.

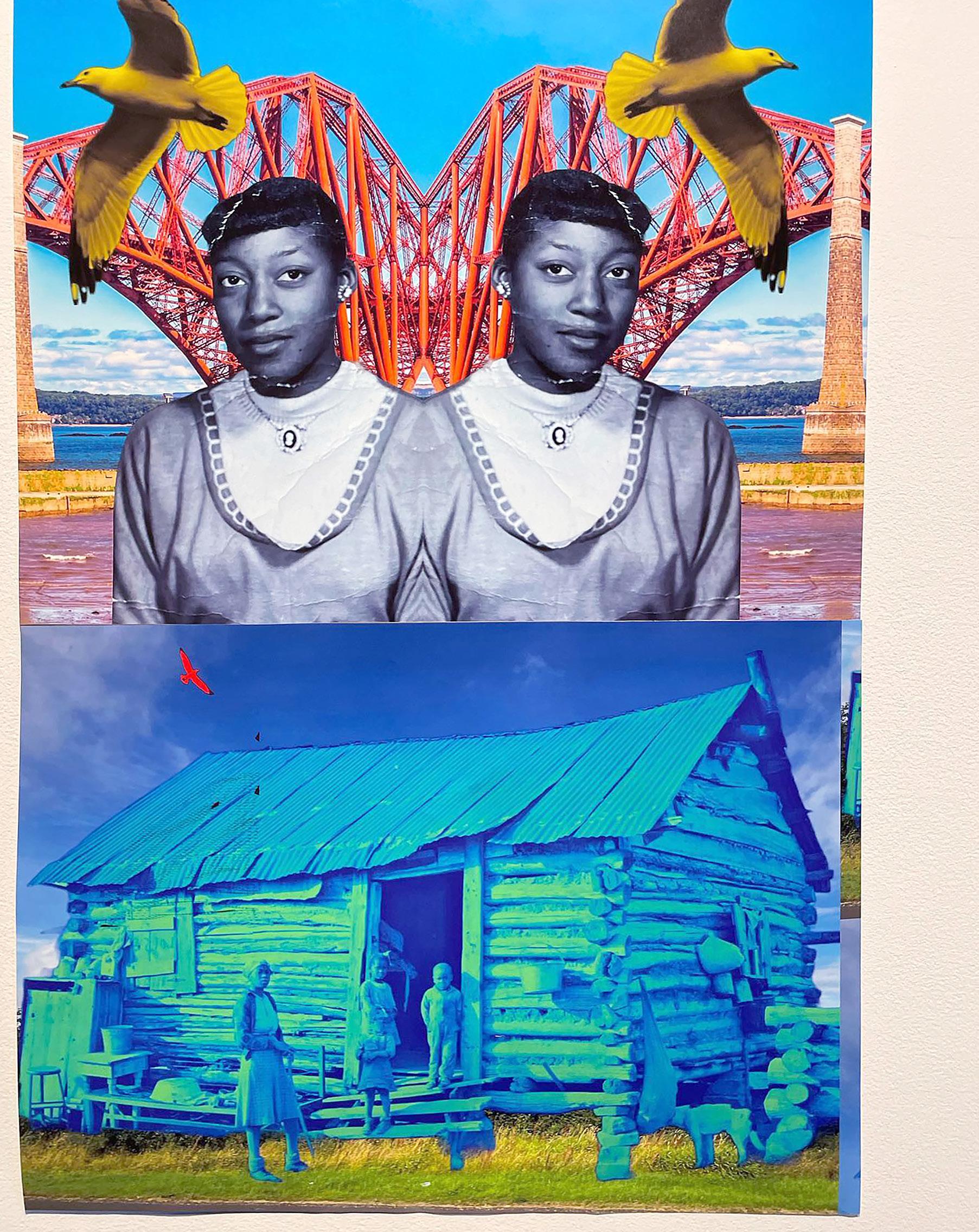

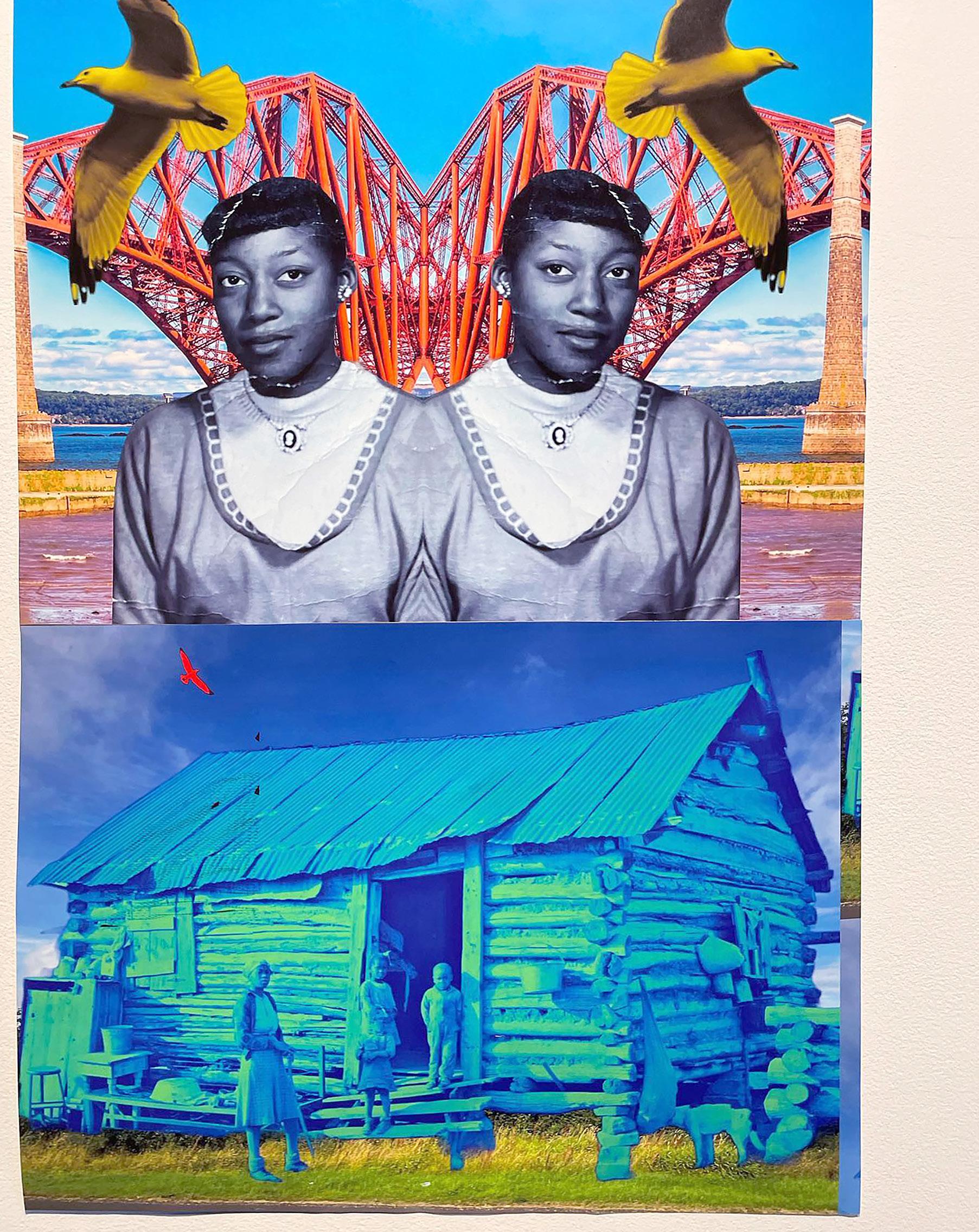

Hawona Sullivan Janzen conjures the present into the past, and the past into the present to imagine futures as a salve for healing through the collective process of remembering and sharing memories. Toward wholeness, she makes visible Black ancestors in her Louisiana birthplace when tracing her newly found Scottish ancestry. She transports them photographically in her portrayal of this present day European shore, enacting her magic to collage the reality of them joining her there. She is guided by her dreams, communications with her ever-present ancestors, and her unwillingness to accept the unquestioned.

Olivia Gallenberger transmogrification

Above: transmogrification, 2023. Exhibition installation view.

Opposite: threshold (detail), 2023. Reduction fired stoneware with ochre, cobalt based underglaze.

9

Wounded Bodies in Outer Space: Olivia Gallenberger’s ceramic sculpture

Christina Schmid

Olivia Gallenberger works with her hands. Whether she kneads clay, weaves fibers, or stains gauze with indigo dye, the body – her body – is instrumental in shaping and imagining her art. Her pinch pots and hand-built ceramic sculptures are a case in point: each work bears the traces of countless small gestures that, together, create a texture and record of interactions with material. The process is laborintensive, repetitive, and demanding. These qualities, in keeping with the exhibition’s title, are all part of Gallenberger’s artistic lineage: she grew up in her family’s bakery, where generations were busy mixing dough and letting yeast rise before firing flour-based forms. Processing ceramics from raw clay to finished, fired, and glazed vessels follows a remarkably similar protocol of production.

The importance of process cannot be overstated in Gallenberger’s art. The iterative practice of molding clay allows her to get lost in the work, a temporary disorientation that allows for meditative states of mind to emerge. Thus, doing the work becomes a pathway to somewhere else. In Lineage, two rows of hand-built ceramic forms, respectively titled pinch pots and portals, emphasize the close relationship between countless gestures recorded in clay and the work’s potential to allow for imaginary movement to an elsewhere, an elsewhen. The titles of her work reflect Gallenberger’s abiding interest in science fiction: planetoids features stacks of ballshaped, textured clay bodies that conjure the distant dark movements of objects caught in the gravity of some distant sun; threshold, a coilbuilt tubular structure, is vaguely reminiscent of a worm-hole; and in exploratory, a digital video that moves the viewer’s gaze along a ceramic sculpture in a probing, tentative way, the artist

invites us to explore the quasi-alien strangeness of the form. Thus, the earthy medium of clay becomes a vessel for speculating about shapes and spaces far from earth.

At the same time, the works in Lineage stay grounded in functional pottery: “Pottery is meant to be touched,” the artist writes. “Please handle the pots with care.” Like most functional hand-made art, pottery is in close relationship with the human body’s capacities: two hands can hold liquid for drinking; a cup, however, expands the range and effectiveness of what can be held. Given the artist’s experiences with chronic illness and her lived experience with being incapacitated, the escapist speculations offered by science fiction complement the connotations of craft in her practice. This tension between the earth-bound and bodily on the one hand and, on the other, the unapologetically speculative animates Gallenberger’s work.

In Wound Care the theme of the injured body is most prominent. A series of indigo-dyed prints on unused medical gauze makes visible the labor of tending to injuries old and new – and lingers on the slow and patient work it takes to allow visible and invisible wounds to heal. incision, on the other hand, suggests an injured body, cut open for surgical intervention. Tubular clay forms lean on each other, as if to support one another through the violence of severance and sutures. In both the print series and incision, Gallenberger’s color choices center shades of blue: indigo dye and cobalt-based underglazes allude to “the blues,” depressive states of mind that the artwork honors even as it transforms them. The desire for transformation is ultimately at the heart of Gallenberger’s art and practice. Relying on clay bodies, she invites us to journey inside and far beyond the confines of a body.

11

Top: incision, 2023. Reduction fired stoneware with ochre, cobalt based underglaze, granufoam.

Bottom: planetoids, 2023. Reduction fired stoneware with ochre.

Top, foreground: threshold, 2023. Reduction fired stoneware with ochre, cobalt based underglaze.

Top, on wall: wound care, 2023. Expired medical gauze, indigo dye.

Bottom: tiny portals, 2023. Reduction fired stoneware with ochre.

12

Olivia Gallenberger (they/she) received their Master of Fine Arts in sculpture and ceramics from the University of Minnesota - Twin Cities in 2023. She grew up in a small Wisconsin town living and working above her father’s bakery. This taught her the importance of working with one’s hands. She watched the hands of her dad and grandpa cut and shape dough in their bakery. Eventually her hands learned to move the same way. Now, these gestures make things out of clay. They explore themes of memory loss, psychiatric care, medical violation, and familial relationships using clay, fiber, photography and poetry. Their interest in science fiction as a means of escapism seeps into the work they make by creating alternative fictions of the body. Gallenberger investigates color as material and metaphor while considering how predisposed obsession affects the intersection between life and art.

Artist Statement

Things are the same as they were, but exist in a new reality. An alternate universe I am the first to explore. My body navigates the space with familiarity. Yet, there is an awkwardness. Something is slightly off and that is okay. The conversation between me and the clay is an intimate whispering. We greet each other with ease.

Our embrace gives me hope.

Our dialogue is unique.

We love to talk about science fiction: Starships traveling home. Alien landscapes. Teleporting and transforming. Wormholes. Portals. Paths to somewhere “beyond”.

I used to have these conversations in my head, but now I have someone to share it with. The clay listens and understands. It boldly goes with me to explore new constellations.

Constellations have to exist in space. My work does the same.

13

Photo by Nik Nerburn.

Camila Leiva

Trae una flor, un poema, una cancion /

Bring a flower, a poem, a song

15

Above: Trae una flor, un poema, una cancion / Bring a flower, a poem, a song, 2023. Exhibition installation view.

Opposite: Chapter 1: Fabiola’s Perseverance, 2023. India ink, acrylic ink, and black ink pen on paper,

11 x 17 in. each.

Con la Mano: Camila Leiva’s Archival Recovery Project

Jessica Lopez Lyman

Trae una flor, un poema, una cancion / Bring a Flower, a Poem, a Song exhibit is a transnational recovery project grounded in Chilean women’s intergenerational knowledges. The multidisciplinary exhibition includes a graphic novel, arpillera textiles, and polychrome clay sculptures. Camila Leiva draws from her years as a trained muralist to venture into new mediums that weave together family archives and domestic aesthetic practices.

Leiva’s work centers her grandmother, Fabiola Letelier, who was a Chilean lawyer and political activist during the time of the Chilean dictatorship. When Fabiola’s brother, Orlando, was assassinated by the regime in 1976, she worked endlessly to uncover her brother’s murder. Known throughout the Chilean press as the Letelier Case, Fabiola ensured that during the post-dictatorship truth-telling process (1990 to 1995) the world would remember the grave violence of the dictatorship and that the family, and more broadly the country, would find healing by bringing the men responsible for the assassination to justice.

Trae una flor roots itself in the archive. Drawing from archives — family correspondence between Fabiola and Orlando, court documents, at-home movies, and a plethora of print media — Leiva tells a story of her great uncle’s death through the activist spirit of her grandmother. Leiva’s multilayered narrative and multi-genre form creates what Diana Taylor terms “the archive and the repertoire,” a slippage between the document and the embodied. Throughout all of the work, but especially in the graphic novel, Leiva grapples with the complexity of being a granddaughter trying to make sense of her family’s violent and activist past. Aesthetically drawn in black and white with pops of red adorning Fabiola’s lips and flower brooch, there are scenes in the graphic novel where Leiva inserts herself talking to her family, learning about the dictatorship as a young girl. These powerful moments illustrate the transnational and temporal nature of grief – there are no borders that can contain loss. Exhibited as an in-process, yet to be finished work, the graphic novel reminds viewers that the archive, while uncovered, is never fully complete until we insert ourselves into the frame.

In addition to family archives, Trae una flor uplifts domestic aesthetic practices Chilean women have passed down from generation to generation. The arpillera is a textile artform made from found fabric that depicts quotidian scenes. During the dictatorship, women would craft arpilleras and then through solidarity networks ship them internationally to provide insight into the atrocities occurring in the country. Leiva’s grandmother supported these networks and her mother smuggled arpilleras out of Chile to Minnesota. Leiva continues the practice of making arpilleras in Fabiola’s Joy, which depicts a birthday party where her grandmother is holding her as a young child. The fabric for the scene came from Fabiola’s old clothes and represents her grandmother’s love for vibrant color. Along with arpilleras, Levia creates a loza policromada [polychrome clay] scene depicting street protest against the state. Leiva learned the women-led folk-art tradition from Talagante, while researching in Chile. In the exhibited scene, Fabiola’s Legacy, the military throws tear gas as protestors fight back. There is a protestor holding a sign that reads, “Verdad y Justicia Ahora!” [Truth and justice now!] Another person sells fruit, and a woman holds up an arpillera with an image of a dove and the words “Libertad [freedom]” stitched above in blue script. Both the arpillera and loza policromada scene showcase the contributions women have made to challenge violent regimes through their domestic aesthetic practices. Leiva expands these mediums to illustrate their contemporary significance and in the process of making them finds solace in creating con la mano.

The final component of the exhibit is a short documentary featuring Fabiola produced from videos found in Leiva’s family archive. Created in partnership with her sister, Leiva’s documentary does more than provide context for her other works. The documentary is a seedling for future work and promises to continue telling Fabiola’s activist legacy. Overall, Trae una flor documents and embodies recovering the archive and domestic traditions in order to process grief and transform a country’s history in order to become sites for renewal.

17

Top: Fabiola’s Joy (Arpillera with Her Clothes) (detail), 2023. Hand stitched fabric, embroidery thread, and acrylic paint, 60 x 66 in.

Bottom: Archive of Fabiola Letelier’s personal effects (detail), 2023. Found objects, dimensions variable.

18

Top: Trae una flor, un poema, una cancion / Bring a flower, a poem, a song, 2023. Exhibition installation view with still image from the short film Fabiola’s Path

Bottom: Fabiola’s Legacy, 2023. Earthenware clay, acrylic paints, underglaze, transparent glaze, approximately 5 to 7 in. per figure.

Camila Leiva (b. 1987) is a transnational Chilean and U.S. American artist and educator whose body and soul are often seen traveling between Minneapolis and Santiago. Her life has been shaped by brave and loving women, especially by her grandmothers and her mother. She grew up in the visual, musical, and literary culture of Chilean social movements for justice, during the final years of the Pinochet dictatorship and in its neoliberal aftermath. She paints community murals, handdraws comics, sews textile arpilleras and molds earthenware clay. She is razor-focused on telling the unknown story of her grandmother Fabiola Letelier, Chile’s most dogged human rights lawyer. Her work explores themes of memory, histories from below, and questioning the public versus private dichotomy imposed on women’s lives.

Artist Statement

Trae una flor, un poema, una cancion / Bring a flower, a poem, a song is an invitation to learn about an extraordinary and imperfect woman named Fabiola, and the implications of growing up as her granddaughter. At the heart of the work is a graphic novel, told in first person narrative by the artist, that mixes archival research, family stories, and childhood memories. Hand drawn comic pages of the first two chapters hang in the gallery next to a short film Camila and her sister Elisa collaborated on, with recovered footage from 1995 of a never-made documentary about Fabiola. An empty perfume bottle, abalone shell ashtray, declassified CIA documents, and a UN badge give dimension to the story. Polychrome figurines, an homage to a Chilean folk art in which women artisans make scenes of the quotidian out of clay, emerged as a tactile way to process the painful family stories of dictatorship. Camila created a protest scene reflecting the tradition of marching in the streets of Santiago. Finally, a Latin American textile form, known as an arpillera, transforms the inherited pieces of Fabiola’s old clothes into an image of abuela and nieta (granddaughter) imbued with memory.

19

Photo by Nik Nerburn.

Nik Nerburn

21

The

Longing

Above: The Old Longing Camp, 2023. Exhibition installation view. Opposite: The Way We Grow Them Here (detail), 2023. Digital image on wallpaper, 120 x 120 in.

Old

Camp

Tall Tales and Tiny Houses: Americana, Unmasked

Christina Schmid

Agiant potato — a practically room-sized oddity — lies half-buried under a pile of wood shavings. A dainty lace curtain hangs above the mammoth tuber while off to the side, a small portrait of a jackalope is taped crudely to faded floral wallpaper. A photograph of this unlikely interior serves as the opening act to Nik Nerburn’s MFA exhibition. Steeped in the vernacular of tall tales and roadside attractions, Nerburn’s creative practice unfolds across an array of media: photography meets woodcarving; sculptural elements turn into installation. In Lineage, the artist follows a generations-old family story from a boarding house in Minneapolis through the upper Midwest, to the lore of logging camps and dusty displays in small-town museums where quirky Americana collide with the cruel history of pioneer culture. The result is a multi-layered exhibition that meditates on masculinity, domesticity, secrets, and shame.

The veneer of folksy sensationalism — the biggest ball of yarn you’ve ever seen! — imperfectly conceals a different kind of story. In the wake of the Great Depression, the Farm Security Administration (FSA) set out to document the plight of rural Americans. Photographers were hired and provided with shooting scripts. Nerburn riffs on this history when he constructs a 1930 memo modeled after the actual shooting scripts and imagines an editor asking for images of “lost men:” itinerant individuals who fled family life and became part of tramp culture, riding trains and camping in “hobo jungles.” Nerburn’s greatgrandfather Joseph was one of these lost men. Rather than simply abandon his family, he fled after pushing his wife Eva down the stairs in a drunken rage. She did not survive the fall.

Nerburn’s project engages this tragic family story as a speculative documentarian. In one series of black and white photographs titled If he wanted to disappear, this would have been the place to do it, he imagines spaces that could have offered a man on the run temporary refuge. Carefully staged color photographs,

such as Moving In and Rented Room, created in dollhouse scale, suggest a compromised domesticity. Nerburn’s doll houses collide the iconography of an idealized domesticity with the insignia of masculine lonerism: wood shavings take over one room while outsized objects — a fishing bobber the size of a soccer ball — threaten a carefully cultivated fantasy of normalcy. Nerburn’s work carefully and gently unravels this fantasy.

The photographs vary in size: some hang in ornately carved wooden frames; others are blown up to wallpaper scale. The hand-carved frames reference the tramp and hobo culture of the Great Depression. Carvings, large and small, lean, hang, and stand in the gallery: a diminutive bindle stick shares a notching pattern with a twelve-foot wooden beam. Such shifts in scale and proportion abound in Nerburn’s work. In a table display that makes use of a model-train landscape — another hobby culturally coded as a masculine pastime — wood shavings imperfectly cover a mossstudded faux wilderness. The miniature clearcut renders the picturesque logic of progress suspect.

Together, the elements of Nerburn’s multifaceted material storytelling lend the work an air of the uncanny and off-kilter. Loss looms large yet unspoken in the narrative’s folds: lost men, lost homes, and perhaps lost faith in the redemptive humor of tall tales. A single black and white photograph, hung amid wood carvings, centers a statue of a robed figure, cross in one hand, the other raised in a blessing. Off to the side, a worn tipi-shaped sign advertises a nameless “Indian Village.” Another loss, of unfathomable proportions, hovers in-between the stories that can be told. Nerburn’s work, through performing the visual equivalent of the sideways glance and trading in allusive entendres, invites a double-take that effectively shifts a complicated affection for Americana into a personal and cultural reckoning with histories that no tall tale can gloss over.

23

Top: From the series If he wanted to disappear, this would have been the place to do it, 2022. Silver gelatin print.

Bottom: Joseph’s Room, 2022. Inkjet print, cherry wood, black stain, 20 x 24 in.

24

Top: The Old Longing Camp, 2023. Exhibition installation view.

Bottom: Rented Room, 2022. Digital image.

Born in Bemidji, Minnesota, Nik Nerburn’s cross-disciplinary photographs, videos, and sculptures reflect his passion for people’s histories and stories from places that are “off the map.” His wideranging work addresses urgent subjects like toxic masculinity and the rural-urban divide, while also centering craft, generosity, trust, and humor. Informed by the collaborative traditions of puppetry and documentary filmmaking, Nerburn works with amateur genealogists, community archivists, neighborhood clubs, small town philosophers, and little museums.

Artist Statement

Nik Nerburn’s current body of work tends to personal and familial stories, using regional vernacular artistic forms like yard art, model making, dollhouses, and tramp style wood carving. His photographs reveal miniature domestic spaces unraveling by way of personal and mythological disaster. Mostly composed inside of dollhouses, his photographic tableaus embody precariousness and turmoil rather than the dollhouse’s middle class ideal. Using traditional processes such as whittling, chip-carving, frame making, and metal casting, Nerburn braids narratives of both whimsy and catastrophe. This is where a giant secret lives in a tiny house, stuck like a piano you can’t fit out the door.

25

Photo by Nik Nerburn.

27

Murmurations Above: Murmurations, 2023. Exhibition installation view. Opposite: Grandfather Henry Smiling (from the Ancestor Wallpaper Series) reflected in mirror.

Hawona

Sullivan Janzen

Hawona Sullivan Janzen: Murmurations

Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski

hen I had a dream. in the dream, there were no colors. in that dream, it was like spirit was saying, “welcome home. welcome home.”

I just trusted, and it just came into being in that way. what was needed, was to share my stories but also to encourage others to consider their own. to create your own.”

Hawona Sullivan Janzen

the salt. then the blue. then the sepia tone. each one in some way a reference to remembering.

an assemblage of complex memories and dreams are convened in this offering, whilst solace and liberation are sought through trusting in the subconscious, led by the auspicious guidance of ancestral wisdom(s). in the creation, reenactments of spiritual dreams are (re)presented.

the space extends a welcome for us to process difficult memories, but not just difficult memories, memories.

in this place, we are preserving memories and stories. in this space we are sharing memories and stories. painstaking, thoughtful efforts, unapparent to the uninitiated viewer are applied in the hope that even the most painful memories become easier to tolerate.

you are invited to enter, sit, rest, wander, and process.

navigating the landscape(s), where the bluest skies meet the bluest seas. ancestral homelands intersect.

West Africa; South Carolina; Louisiana; Scotland; England; Wales; Ireland; Spain. the labour of a griot is visible, reconstructing, retelling, reconciling intimate family narratives through (self) portraiture. here, photographic technologies are not used as a reflection of reality but instead, to invoke images that conjure and combine new and old truths. the whispering ripples of short stories, poems, and songs, weave in and out of this landscape, libations, bearing witness.

in this space, in this place, the mundane is worshipped, revered, and reclaimed. new kinds of landscapes resuscitated. in this space, in this place, Black memory work becomes an embodied and embedded methodology and practice. in the west. in the east. in the north. in the south.

a collective embodied and embedded methodology and practice. Black memory work as murmuration.

“t

29

Top: Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski in the gallery. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Bottom, from left: Girl Cousins in Senegal with 6 Birds and Self Portrait as Afropean, 2023.

30

Aunt Kathleen’s Only Daughter (Makes her Presence Known) (top) and When First We Visited the Green Isle (bottom), from the Ancestor Wallpapers Series, 2023.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

Hawona Sullivan Janzen is a Saint Paul-based social practice and visual artist whose work explores the intersections of grief, loss, love, and hope. A 2020 Jerome Foundation Naked Stages Fellow, Hawona has received funding from the Minnesota State Arts Board, the National Endowment for the Arts, Metropolitan Regional Arts Council, and the McKnight Foundation. Her writings have been read on National Public Radio, featured in 10-foot-tall broadsides, performed as a jazz opera, and produced as a play at Pillsbury House Theatre. Her recent projects include the co-design of Saint Paul’s Dale Street Bridge over I-94 and Love Letters for the Midway — a crowdsourced poem printed onto lawn signs.

Artist Statement

i am the black-white. the descendant of the enslaved and enslavers. both torn open. let me be the salve: the thread that seals these wounds.

The images, performances, and poetry in this work are the result of a journey through dreamconjure, and acts of divination. According to my dna profile, the blood of more than seventeen nations swirls in my veins. After discovering this I began to ponder who I really am physically, genetically, artistically, and spiritually versus who I might have been had my ancestors lived solely in one of these landscapes. I seek to explore how each of those cultures may manifest itself in me. Using real-altered photos and images from travel to several of my ancestral homelands, I began creating digital collages that seem to be a path to answers. May my journey inform and illuminate the path for any who follow.

31

Photo by Nik Nerburn.

32 ,

Witnessing Delta Passage

Professor Diane Willow Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art

What began as a story of three artists, Calvin Stalvig, Namir Fearce and Whalen Polikoff, continues as a story of three artists interwoven in their resolve to value love as motivation. Each conjures love in their work as they collectively call upon us to attend to grief and healing, memory and amnesia, power and justice, violence and protection, ghosts and hauntings, death and life. Within the cosmos of Delta Passage, the potential for transcendence takes many forms. It emerges while activating ancestral folkways, flipping assumptions, confronting the horrific, holding the sacred, feeling pleasure, inviting the mysterious.

When I reflect on my lingering experience of Delta Passage I think about:

Passage, as movement, as change. The ebb and flow of inner and outer time, shaping and catalyzing the growth of each person. Passage, as a decisive 2021 graduate school entrance by three artists marking their first year of three. Passage, ongoing creative process open to internal spells of time that spawn imagination, unknowing, and courage, risk, tempest, and reflection. Passage into year three. Once imagined as a far away future, it has arrived, and with it the transformations that emerged as Delta Passage

This particular Passage, Delta Passage, is a generative form of fruition. It is a culmination and it is a beginning, one that shapes a previously unknowable opening. Inner worlds of artistic vision mirror an outer world that is anticipating a long awaited spring blossoming. Delta Passage signals a warming season for the spirit, Passage into a rippling atmosphere of love, generated by Namir, Calvin, and Whalen, to support their growth and wellbeing. Passage from solitary notions of what it is to survive as individual artists to a collective proposition of what it may be to thrive in interdependence.

Delta, presented as singular, exists as multivalent, holding multiple concurrent meanings.

Namir summons Delta Blues, Mississippi, alluvial flow, floodwaters, mourning, transmutation, Black migratory descendants, home.

Calvin evokes Delta, the uppercase Greek letter ∆ , a symbol for change and variation, the occult, nodes of connection, of three.

Whalen names Delta FPCON, (Force Protection Conditions), a military global threat code of ever escalating levels: normal, alpha, bravo, charlie, delta.

Delta is Namir Fearce’s Delta - Hi Cotton, Calvin Stalvig’s Delta - Chapter One, and Whalen Polikoff’s Delta - I’m Not Yelling. Together, Whalen, Calvin and Namir recognized and amplified a resonance that each embraced in this threefold now one relationship with Delta, a transcendence that is Delta Passage

WeProfessor Jane Blocker Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art History

WeProfessor Jane Blocker Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art History

At my side. At my elbow. At my throat. At its heart.

To work together (col-labor-ate) — to be with, to talk with, to think with, to write with, to make with — seems risky, almost impossible these days. Oddly, one of the meanings of the word “with” is adverse, against, opposite. No “with” without division. No “with” without “without.” We read every day of the divided polis. The country torn apart. The era of with and without.

We (I use the word “we,” but there is still no we) were crossed. Like a street. Double crossed, like a promise gone back on. Like a line policed. Police line. Do not cross.

We (I use the word “we,” but there was no we) were alone. Locked down. Locked out. Locked up. I think of Anne Sexton writing, “I am in my own mind. I am locked in the wrong house.”1

We (I use the word “we,” but that’s just it, there was no we) were siloed. Towered in ivory. Towered in a corporate ruin; the corner office of a West Bank claim staked in 1963 (once called Management/Econ, then rebranded as “The Arts Quarter”). To get to Regis Center for Art, just follow the derelict lamppost banners (on which a meaningless scribble stands for ART) left for two decades to bleach in the sun.

How can we be a we? I think of Toni Morrison writing, “She is a friend of my

mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them and give them back to me in all the right order.”2

We, that is, Jennifer Marshall, Chris Baeumler, Diane Willow, and I, proposed a small collaboration. It meant minding one another, gathering each other’s pieces, sharing each other’s students. We had to cross the street.

What is withing? Withal. In addition. In conjunction. Interest. It is to place oneself in the hands of another as a gift to be opened. A game to be played. A puzzle to be solved.

In 1955, Robert Rauschenberg made a painting called Rebus. A rebus is a visual puzzle combining letters, words, and pictures. Art and writing. A collaboration.

The essays here, written by poet Douglas Kearney and art historians Nadia DelMedico and Ashley Duffey, are as material as painted fabric. Soaked. Stiffened. Like a page from the newspaper, made thick with encaustic or Cy Twombly’s desperate scribbles at the end of the world. They are offered here with Calvin Stalvig’s, Whalen Polikoff’s, and Namir Fearce’s convictions. Their art of conviction is as bold as dripping red paint, as loud as a headline, the anguish of a torn sleeve.

Rauschenberg’s painting? It was, he said, “a record of the immediate environment and time.”

1Anne Sexton, “For the Year of the Insane,” Anne Sexton: The Complete Poems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981), 133.

2Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Penguin Books, Ltd., 1987), 272-3.

Namir Fearce

Cotton

37

Hi

Above: Hi Cotton, 2024. Exhibition installation view. Opposite: heart turn coal, 2024. Installation view.

Joy, Pain, and Hi Cotton

Douglas Kearney

So it go to be “in high cotton” is to find oneself in good fortune. For when “the cotton is high” (see Gershwin’s “Summertime”), one need not bend to pull a boll free of its barbed stem. In this, then, we see intertwined the do low and the come up, the pain there to ceiling transcendence (that old hustle), or, better yet, to chain it down, lashing and moor, upon strange ground.

Artist Namir Fearce’s High Cotton, then, is a nod to this ambivalence. A person(a)—say Dunbar’s mask, though in regalia that eschews a physical fac covering—High Cotton might could remind of Yemaya, Drexciya, David Dabydeen’s Turner (a reference to JMW’s famed and lurid painting), and The Creature from the Black Lagoon. Even “Namir” slant rhymes with “Namor,” Marvel’s Submariner predating his MCU premiere in Wakanda (like Drexciya or Stankonia, another utopia of Black imagination). All of this is to say that the syncretization Fearce flexes makes a complex of diaspora in one: an atavistic next step in the necessary evolution of Blackness in a terra-/terror-formed post-plantationosphere: High Cotton “can dance underwater and not get wet”1: amphibious and ambivalent.

If transcendence is commonly considered the facility of going high when shit gets too low, we can see a parallel in rhetoric regarding what criticism calls “vernacular art.” Up in there, like graf writing down on the gallery’s white wall, we find the drive to invent inventory taxonomies, thus to see where to put down what got picked up. Fearce’s side eye isn’t rolling at the notion of “vernacular,” that’s the radio signal through the white noise, the static. Rather, the artist might have us set it in all caps: VERNACULAR (he doesn’t want you to get it twisted).

To this end, Fearce means for you to see the chicken wire infrastructure of his sculptures, themselves kaiju-versions of the African Americana tchotchkes (read: NAACP’d “negrobilia”) he picked for his installation, displayed not quite as scale figures for an architectural model; for that, check Lauren Halsey’s we still here, there. What could scan as kitsch come gets to be set on a shelf like an ancestral altar, presided over by a tintype-type photo of High Cotton, glowering-eyed, spiny-fin eared, barracuda toothed.

The sculptures draw from and tool-up the collectibles—many of Fearce’s nonstalgic make— arming the tropes (Black kewpies, Black kewpies used for gator lures) into troupes and troops. They are here to play, but not for play-play. Ask “Chopper,” the big ‘gator hovering above, his long mouth sporting rifle-round teeth. On his back sets one of Fearce’s “Baby” sculptures, their hair a crown or up-twist terminating high in bolls of cotton: the family jewels. Composed thus, Fearce preps the Baby for battle, not bait, a member of a sea/land/air calvary swinging low this time, but not in the cut, as Fearce means for you to see. Beyond the visible mesh, the intentional and critical mess of rider and steed’s skins are rough wound with cheesecloth and plaster (blackened, all), so you can see the light through and the hand what cut the pieces to be assembled.

Materially, Fearce signifies as well. A Baby stands on a hill of beans (an idiom for something worth little), turning under light like a display item (a technique suggesting something worth buying).

A mama as boat carries in her hold, more embrace than storage space, a Baby and more kewpies. Here, Fearce uses industrial “black stretch wrap” for skin, the heat gun application suggesting scarification and keloids. Mama’s do a W. Mama’s shipshape like a figure head slouched all the way back to the aft of the craft, a gangsta lean and spine. Behind (or below) Mama, a video projection of a river, flanked by twinned supine images of Fearce entwined in bright, white bindings. Going over the water might be Jordan (crossing to death), the ocean (into the ‘New World’ or back to the Home World); but as the shipping wrap puns, the voyagers are in a supply chain, swung from (un!)wanted to (un?)wanted.

Speaking of swinging, by which I mean to mean going back and going forth, two Babies ride playground swings, their seats bits of white, picket fence hanged from the rafters. Their pendulum trajectory rhyming with time and displace. Black skin blue lit, bouncing blueblack back, the Babies soar over another white fence fragment recovered from Fearce’s grandmama yard. As the swing seats do, the broken picket does doublework, a suggestion of an American dream of utopian home ownership on the one, on the two, a surface for projection, another

1See Parliament

word for “dreaming.” A video of Fearce’s Crone persona—this one a mask—loops, going around to begin again. The fence screen mounted on more salvage, iron gate work with filigree quoting the Adinkra symbol for Sankofa: “go back and get it” or moving reversed for to move forward, a swung and swinging loop.

Hanged also is a sculpture of an Ananse/Aunt Nancy figure, a trickster reference to the spider of Akan and Caribbean folklore. Fearce’s spiderfolk (singular) rocks gold hoops and, similarly to High Cotton and Chopper, features teeth that, if bared to smile, reveal danger. Joy and pain, like Frankie Beverly and Maze played in a Black backyard turn up. Bet. But what pain is here can be made shanks aimed away from the Blackself. A shadow narrative uprises from the blue and red filtered lighting of the great Spider; the thread from which it descends conjures Obatala, the Yoruban sky god and creator of humankind. Seen like that, one could locate the origins of each suspended figure as coming down or coming up, movement through time + space made vertical versus the strict horizontality of teleological expansion as colonial plunder-economics.

The material appetite—which is to say acquisition of capital and the desire for the tactile, find themselves deferred in another projection. The Crone croons in a video featuring stop-motion tchotchkes, détourning “Christmas Time is Here” into a litany of grief. Joy and pain, come

again. Yet, in this here, here, Fearce stacks up on irony and signification: Vincent Guaraldi’s song, a centerpiece of Merry Christmas, Charlie Brown, evokes nostalgia for some. Bittersweet in its original context—a Holiday special in which a child bemoans commercialism’s appropriation of the spiritual—“Christmas Time is Here” becomes more haunting in Fearce’s hands. The animation reminded me of the Rankin-Bass canonical Holiday shows, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and The Year without a Santa Claus as Fearce’s blued singing suggests a past-Midnight slide into a darkness lit by sirens and 12’s muzzle flashes. Merry Christmas.

As the video passes, however, Fearce gifts us with an additional clip. Scenes from a documentary about a Blues singer, the video features a Black family within a Black gaze, kin and kith Fearce syncretizes as his own clan. Not quite a standin, not quite not. This projection is a wish for such footage to exist of his genealogical family and like Fearce’s other works of salvage, there is the desire to keep what could be taken after centuries of theft. It’s that loop, a historical Changing Same, made up of the dream and nightmare we stay finding ourselves down in: the family function fades gently back into the jeremiad “Christmas Time is Near.” The caustic suggestion Fearce makes? Antiblack violence is the gift that keeps on giving, joy bought with Black tears, sweat, and blood. Irrigation for someone’s high cotton.

39

Hi Cotton Altar (detail), 2024. Leather hide, burnt wood panel, tintypes, wax figures.

40

Top: Sweet Chariot, Choppa’ n Baby, 2024. Chicken wire, plaster wrap, foam clay.

Bottom: Riding the fence, 2022. Reclaimed fence, projection, chicken wire, foam clay, gold bamboo earrings.

Namir Fearce holds a BFA in Studio Art with a concentration in film and sculpture from the University of Illinois Chicago. His work has been featured in Dazed, Paper, Them, and Office Magazine, in addition to The New York Times. He is a 2020 Walker Arts Fellow and a Black Harvest Film Festival nominated director. Fearce most recently curated, directed, and produced a multi media performance and storytelling festival, Hi Cotton, which has been shown in Minneapolis, Rio De Janeiro, and Berlin.

Artist Statement

Namir Fearce is a North Minneapolis born interdisciplinary artist and cultural worker. His studio practice engages experimental film, assemblage, and music under the moniker Blu Bone. Fearce is informed by a constellation of Black Indigenous histories and sites of memory that weave complex emo-political worldscapes, while conjuring a futurity of pleasure and freedom. The emo-political is the positionality of the fugitive—those who by embracing their Indigenous technologies of survival, somatic, and pleasure based knowledge, agitate and resist the white fascistic cognitive schema, and doctrine of domination.

Fearce’s work collapses, samples, and collages these histories and sites of experience to transmute grief as a technology of survival and practice of cultural resistance. Through performance he embodies across species to access an expanded empathy, an understanding of the reversal, and the way of the blues. Across all facets of his practice exist sites of ritual, and ceremony, that visually, sonically, and somatically converge and reverberate to generate a feedback loop as the blues does—a portal that opens to a collective reimagining.

41

Photo by Justin D. Allen.

Whalen Polikoff I’m Not

Yelling

Above: We Look Through the Lens and Stare Past the Moon, 2023. Surplus USN Utility shirt, wooden frame, hide toggle clips, ratchet straps, 87 x 97 in.

Opposite: The Enduring Freedom of War and Work are set in Stone and Steel, 2024. Acrylic on canvas, wooden frame, hide toggle clips, ratchet straps, 10 x 10 ft.

43

Cause for Alarm: Dog Whistles, Political Malignancies, and Visual Encoding in the art of Whalen Polikoff

Nadia DelMedico

Haunted by the threat of complacencybased ignorance, painter and printmaker Whalen Polikoff weaponizes the power of the physical object to reawaken viewers and pause the slippage of reality that becomes possible through digital media and information inundation. Stylistically situated at the intersection of Max Beckmann and Honoré Daumier, Polikoff transforms the painting and the print into an exercise in encoding and decoding. Through his own practice of covert signaling via art historical citation, Polikoff visually mirrors this verbal and written encoding as he works to disentangle it. This exhibition demonstrates the possibilities that emerge when political dog whistles, sensorially imperceptible but subliminally persuasive, are rendered visibly legible: time becomes collapsible, a lineage of theory becomes discernible, a whistle becomes a shout, a shout becomes a bullhorn.

Polikoff’s process is similar to that of collage. Drawn to iconographies and aesthetics that render insecurity and strength simultaneously, the artist synthesizes figures and references into singular painted and printed images. Inspired by material ranging from early modern religious iconography to nineteenth-century Romanticism to twenty-first century firstperson shooter video games, Polikoff marries art historical canon and visual culture archives. By collecting a century’s worth of images of colonial making and re-making, Polikoff collapses time and the archive upon itself, curating images that undermine, through their alignment with, the pictorial logics of Western Catholic empire. The power of the image, then, is in demonstrating the fragile underpinnings of the very symbols of dominance.

Polikoff’s installation is anchored in three double-sided canvases, pulled taut by orange, industrial straps in visible tension with the wooden frame, actively tearing and shredding the edges of the composition. Unstretched, raw-edged, and creased, the untreated

canvases undermine the urge to mentally catalog the painting as an artifact of a historical past and reinvigorate a sense of urgency and immediacy in viewers. Though not conceived of as a series, the canvases guide the viewer through a narrative progression that evokes centuries of United States interventionist policy and colonialism.

Ranch Hands Lay Razor Wire on the Golden Hill is the only vignette that does not feature a human figure. Instead, Polikoff presents the immaterial and inhuman presence: a set of clothes with corporeal structure but no physical body; a mushroom cloud instead of a head; a haunting shadow without a physical pair. On the verso (Burned Books are Worth Twice the Bush), the airy blue sky is replaced by a bloodred void of a room in which a group of variably obfuscated human-adjacent forms present a tome whose cover mimics the portal sculptures of Gothic cathedrals. Based on photographs from conservative uprisings in Bolivia, Brazil, and the United States, the figures on the right side are amorphous and under-formed as though they are still malleable, like the slightest force impressed upon them would permanently alter their compositions. The two central figures stake a more concrete claim: one, his hand resting on this bible of war, speaks to an unseen crowd or camera, while his counterpart, eyes and face covered, stands his ground. A lone soldier waves a white flag in the form of an open book lifted over his head; he becomes unidentifiable as his hat covers his face. The previously immaterial presence invades, physically and ideologically.

In Stacked Decks of Prayer Cards and the Lamentations of Circling Wagons, Archangel Michael (in his typical form: winged, robed, lanced) descends from the sky, looming over a crying humanoid and screaming horse. The only angel named in the Bible, the Torah, and the Quran, Michael is known as an angel called upon for aid during crisis; however, as much as he is known for being a protector,

he is also an angel of death. He assumes the role of death-bringer here: the man in the foreground cries out of blank, lifeless eyes, desperately clinging to his hat with a visibly tensed hand. His horse, modeled directly after the same creature in Picasso’s Guernica, flags this scene as one of atrocity. Perhaps here more than anywhere else, Polikoff models his ethos of encoding and decoding: what appears to be an act of divine violence is encoded as a statement against war. The reverse is dominated by an alienlike adaptation of Francisco Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Son. In Polikoff’s rendition, Saturn is deconstructed into a surreal anatomical model of raw, red flesh, muscly sinew, and disproportionate limbs. He stretches the intestine-like body on the table in front of him like dough as he scoops it into his mouth. The narrative reaches a nadir, with near total dissolution of humanity as men cannibalize each other literally and metaphorically in service of the nation-state.

The third and final canvas returns the narrative to the homefront. In Baying Pigs give their Tongues to Tracking Hounds, an intestinal, rabid dog tries to shake itself free from its collar in a Futurist blur of motion, his efforts futile against his owner’s tightly-gathered short leash. The narrative sequence concludes with what the military effort claims to protect: the family unit.

An Americanized version of Adolf Wissel’s Farm Family from Kahlenberg (1939), sold to Adolf Hitler as a representation of the prototype for the ideologically conformant family during the rise of his National Socialist German Worker, or Nazi party, Polikoff’s subjects in The Enduring Freedom of War and Work are set in Stone and Steel, are jarringly lifeless. The centrally seated boy is the only subject who breaks the fourth wall, his hollow eyes turned to but not focused on the viewer. Instead of a toy, he holds a miniature of the American Response Monument; perhaps he knows that he will come of age and join the next response effort.

Polikoff and his work are consumed by deriving understanding from the seemingly unthinkable present that we find ourselves in. Visual media becomes a vehicle for understanding the deeply rooted but often invisible structures of existence. The power in noting and observing these visual permutations of political ideology is that its documentation in physical form equips viewers to look with more critical discernment. Polikoff’s work, therefore, makes an important intervention in developing political and artistic literacy across media; preservation of the past and representation of the political present enable viewers to liberate themselves from historical amnesia and complacency.

45

Stacked Decks of Prayer Cards and the Lamentations of Circling Wagons (left), 2023, and Ranch Hands Lay Razor Wire on the Golden Hill (right), 2023. Both: Acrylic on canvas, wooden frame, hide toggle clips, ratchet straps, 10 x 10 ft.

46

Top: Burned Books are Worth Twice the Bush (left), 2023 and Ewes Nestle Spine to Spine on a Bed of Sunning Perineum (right), 2023. Both: Acrylic on canvas, wooden frame, hide toggle clips, ratchet straps, 10 x 10 ft.

Bottom: Be Bound and Maintain your Arms, 2023. Two channel video, 5 min.

Whalen Polikoff (b.1996, United States) received his BFA in sculpture from the Lyme Academy College of Fine Arts in 2019. He is an interdisciplinary artist working in painting, drawing, printmaking and sculpture. He navigates the visual, verbal, metaphysical culture that shaped his early childhood growing up in Central New York. As a cancer survivor, his diagnosis in highschool continues to inform the urgency of his practice and his relationship to survival.

Artist Statement

My work addresses the visual, verbal, and metaphysical culture that shaped my early childhood. At the heart of this culture was a desire for national and social belonging—a promise of safety. We see these same desires made tangible through the conservative nationalism that can be found in america’s mainstream political parties and identities. The biden administration, with backing from the democratic and republican parties, continues to aid the aparthied state of israel in its genocide of the Palestinian people. My work bears witness to the justification of atrocities by the state as a result of nationalist complacency and conditioned ambivalence towards violence.

47

Photo by Justin D. Allen.

Calvin Stalvig

Chapter One

Above: Ghost House, 2024.

Opposite: Spirit Sweeper, 2024.

49

Ancestor: A No-Act Play

Ashley E. Kim Duffey

ALVIN STALVIG, Artist: a graduating MFA student

ANCESTOR: a sewn, terrycloth body, made up of dismembered legs, arms, and a central torso; a portal for communication with ancestors; a receptacle of pain

URSA MAJOR: cast iron sculpture, a soft, feminine form.

GHOST HOUSE: a plastic form suggesting an interior, but which one may only experience exteriorly.

SPIRIT SWEEPER: sorghum and nylon and leather, both bulwarked against and susceptible to winds.

CANDLEMAN: beeswax candles suspended from a wooden scaffolding by their still-looped wicks

DUSTPAN: a method of fertility worship; 53 hand-welded, powder coated dust pans with hand-turned and sanded handles.

SCENE 1

(CALVIN stands before the altar, considering the cast iron URSA MAJOR standing upon it surrounded by glass forms, trophies as it were, there both to venerate and protect her. ANCESTOR is piled to CALVIN’s right, all its appendages attached, both figures’ backs facing the audience, their voices muffled by the fourth wall.

ANCESTOR is propped up to look at URSA MAJOR, the cast body absorbing the flickering candlelight. The light, on this altar, becomes an offering of warmth and essence, given to URSA MAJOR as a representative of the ancestors, to ask for intercession, for guidance, for love. What is it we offer of ourselves? What do we give in worship? What do we demand of our ghosts?)

CALVIN STALVIG, ARTIST

I think it was God.

ANCESTOR

(facing its head towards CALVIN, gesturing towards comprehension) Oh, like God––

CALVIN

(interrupting)

God was like, “you’re going to be sick now.” And that was it.

ANCESTOR

(facing its head towards CALVIN, gesturing towards comprehension) Oh, like God––

CALVIN

I think it was God.

SCENE 2

(CALVIN stands inside GHOST HOUSE, vocalizing, humming a harmony to the sounds that emanate from the space. ANCESTOR, still assembled, rests upright outside, back to the audience, looking through GHOST HOUSE to the back of the stage.

ANCESTOR considers a story that CALVIN shared offstage about his most memorable birthday, his seventh, an occasion on which he received a set of Power Rangers walkie talkies, and which occurred a month after his uncle died. Are walkie talkies a way to imagine talking to the disembodied, to the dead? Are they a way to bridge outside and in? What secrets lie in a feedback loop?

CALVIN thinks carefully about the loops and circuits that mark a life, weaving through domestic spaces, the ties that bind not just the embodied family but also those “beyond.” What makes a home if not its spirit(s)? How does the home define its space? How does a spirit?)

C

CALVIN

(from inside GHOST HOUSE)

Outside.

Inside?

ANCESTOR

(from outside GHOST HOUSE)

CALVIN

(now outside GHOST HOUSE, gazing up past its roof into the space beyond the audience) Inside?

ANCESTOR

Outside.

SCENE 3

(CALVIN slaloms between the three spirits, a sacred triangulation of energies. ANCESTOR rests detached in a pile in front of the central figure facing the audience, creating an obstacle for CALVIN’s ambulation through the spirits. The fourth wall seems now to calcify, becoming more than a suggested barrier.

CANDLEMAN is a light, guiding and orienting, but also destruction.

SPIRIT SWEEPER cleans, prepares, purifies,

distributes, energies.

DUSTPAN collects, holds, carries.

In his ambulation, CALVIN is led, cleansed, held. He asks the figures to guide him: what does it mean to craft art? When does craft become art, and art craft? Is life, being, a matter of art or craft?

CALVIN

(still walking, now gesturing)

Fire and ash.

ANCESTOR

(still standing in front of SPIRIT SWEEPER) What builds us?

CALVIN

What do we build?

ANCESTOR

What builds us.

CALVIN

(stopping midstep, looking towards ANCESTOR, who returns his gaze)

Fire and ash?

51

Altar To Ursa Major (detail), 2023. Mixed media installation.

52

Top: The Gate Portal, 2024, and Altar To Ursa Major, 2023

Bottom: Candleman, 2024.

Calvin Stalvig creates sculpture, installation, works on paper, digital collage, video, and performance. By approaching artmaking with a child’s curiosity and love for the material world, he alchemizes the everyday ordinary into poetic compositions charged with sacred symbols and relationships. Calvin has exhibited at Law Warschaw Gallery, St. Paul, MN; Washburn Lofts, Minneapolis, MN; The Invisible Dog Art Center, Brooklyn, NY; Governors Island, New York, NY; Electronic + Textiles Institute Berlin; and Regis Center for Art, Minneapolis, MN. His work was included in Issue 2 of the Minneapolis-based publication Scorched Feet / Quemados Pies. He is the former Director of Youth Programs at Beam Center in Brooklyn and holds an M.A. in Youth Development from City University of New York.

Artist Statement

I was born and raised in a family of folk painters, assemblage artists, and stage actors living on the harbor’s edge of Gitchi-gaami Lake Superior —one of Earth’s largest freshwater portals to the underworld. I am a sensualist compelled by a desire to feel, taste, manipulate, and co-create with the world around me. To this end, my practice slips between mediums. I cast beeswax in silicone and iron in sand. I stitch industrial felt into rock formations and epoxy stacks of glass into trophies. My artwork and installations are a synthesis of ritually collapsing dreams, ghost stories, and premonition into something that feels like a lifeboat for survival.

53

Photo by Justin D. Allen.

About the writers

Nadia DelMedico is a historian of American art and material culture. Her research focuses on the art and visual culture of the southeastern United States across the long nineteenth century, particularly as it pertains to immigration, transatlantic exchange, and constructions of race. Her previous work has explored the role of Italian immigrant artists in shaping the built and cultural environment of New Orleans in the nineteenth century. Her current work continues to investigate these themes, and expands into the realm of domestic material culture and its role in shaping immigrant identity. She holds a B.A. and M.A. in art history from the University of Alabama, and is currently a Ph.D. student in art history at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

Ashley E. Kim Duffey is a Korean American art historian based in Minneapolis, MN. Her dissertation, “(Re)visioning Kinship: Photographies of U.S.-Korean Adoption since 1953,” considers the role of photography in producing, facilitating, and responding to the conditions of Korean adoption to the United States. Her scholarly interests also include ghostliness, haunting, and practices of spirit communications, especially as they mark or describe the lives of peoples living in diaspora in the United States. She has published two exhibition reviews on the work of Korean American artists and looks forward to continued opportunities for supporting working artists. Kim Duffey’s work has been supported by the American Council of Learned Societies and the Henry R. Luce Foundation.

Douglas Kearney has published eight books ranging from poetry to essays. In 2023, Optic Subwoof, a collection of his Bagley Wright lectures, won the Poetry Foundation’s Pegasus Prize for Poetry Criticism and the CLMP Firecracker Award for Creative Nonfiction. His seventh, Sho (Wave Books), is a Griffin Poetry Prize and Minnesota Book Award winner. Kearney is a Whiting Writers and Foundation for Contemporary Arts Cy Twombly awardee with residencies/fellowships including Cave Canem, The Rauschenberg Foundation, and The McKnight Foundation. He is a Samuel Russell Chair in the Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Associate Professor of English at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

Jessica Lopez Lyman, Ph.D. is an interdisciplinary performance artist and Xicana feminist scholar interested in how Indigenous and People of Color create alternative spaces to heal and imagine new worlds. She received her Ph.D. in Chicana and Chicano Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Jessica has published poetry and scholarship in Chicana/Latina Studies Journal, Label Me Latina/o, and Praxis: Gender and Cultural Critiques. Her manuscript Midwest Mujeres: Chicana/ Latina Art and Performance explores racialized and gendered geographies of urban Minnesota. Jessica’s second project focuses on climate justice. She built La Luchadora, a mobile screen printing cart, and prints political posters with communities across the state. She currently serves on the Academia Cesar Chavez Board of Directors and is the Board Chair of Serpentina Arts. Jessica is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Chicano and Latino Studies at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski is a mixed media artist and archivist. Her research explores the synergies between Black feminisms, DIY & queer culture, and (self) archiving as a curatorial method and artistic practice. She is co-editor and contributing author for Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life (Thames & Hudson, 2024). Her writing and photography have been included in the Feminist Review, British Art Studies journals, Hyperallergic, and MN Artists online platforms. Alongside art historian Alexandra Nicome she is currently part of the archival and curatorial team for The Black Gate, a radical creative legacy project founded by Saint Paul based multidisciplinary artist Seitu K. Jones

Christina Schmid is a writer who thinks with art and experiments with prose. Her arts writing unfolds as a critical practice and takes shape in creative non-fiction, always in dialogue with art and story. Through art, her work engages with the ways cultural narratives shape experiences and encounters, delves into ethics, the politics of immigration, feminism, queer ecology, practices of belonging, and wherever else art takes her. As a writer, she is interested in the materiality of text, haptic criticism, and the ways art can embody, archive, and generate ideas. Her essays and reviews have been published online and in print, in anthologies, journals, zines, artist books, and exhibition catalogs. She works at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Art in Minneapolis where she teaches contemporary art, critical practice, creative processes, and theory. She is a recipient of a MN State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant for Creative Prose.

Land Acknowledgment

The Department of Art acknowledges that the University of Minnesota is on the ancestral and contemporary lands of the Dakota people. As a land grant institution that was created through and continues to profit from the genocide, coercion, theft, and forced displacement of Dakota, Anishinaabeg, Ho-Chunk, and Cheyenne peoples, the University of Minnesota has an obligation to recognize and counter historical and contemporary injustices that continue to shape our environment. The recently released TRUTH Report, which stands for “Towards Recognition and University-Tribal Healing,” focuses on the past and systemic harms towards Indigenous people by the University of Minnesota and offers concrete steps towards recognizing tribal sovereignty healing.

The University can begin by acknowledging the ongoing debt that is owed to the region’s Tribal Nations, respecting Tribal sovereignty, and investing in Tribal-led programs that promote nation-building, selfdetermination, and trust-building through mutually beneficial education, partnerships, research, policies, and practices that center Indigeneity.

University of Minnesota

Department of Art MFA Program

Professor Christine Baeumler, Chair

Professor Diane Willow, Director of Graduate Studies

Patricia Straub, Graduate Program Coordinator

Shannon Birge Laudon, Administrative Director

The Katherine E. Nash Gallery

Howard Oransky, Gallery Director

Teréz Iacovino, Assistant Curator

Nash Gallery Assistants: Kathryn Blommel, Jordan Bongaarts, Mikayla Ennevor, Kayla Fryer, Eleanore McKenzie Stevenson, Roya Nazari Najafabadi, Breena Pehler

Special Thanks To

The staff and faculty of the University of Minnesota Department of Art, especially: Facilities Coordinator Jim Gubernick, IT Specialist Karen Haselmann, and

Technology Administration Technician Sonja Peterson

Professor Jane Blocker and the University of Minnesota Department of Art History

Lighting Supervisor Bill Healey and the University of Minnesota Department of Theatre Arts & Dance, including MFA candidates Wesley Cone and Jacqulin Stauder

The MFA students, their families, and their friends

University of Minnesota Department of Art students, alumni, and donors

Exhibition Photography

Easton M. Green

Portraits of the Artists Nik Nerburn & Justin D. Allen

Catalogue Design Russ White

Printed by Smart Set, Minneapolis

art.umn.edu | 612-625-8096 | artdept@umn.edu

WeProfessor Jane Blocker Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art History

WeProfessor Jane Blocker Director of Graduate Studies, University of Minnesota Department of Art History