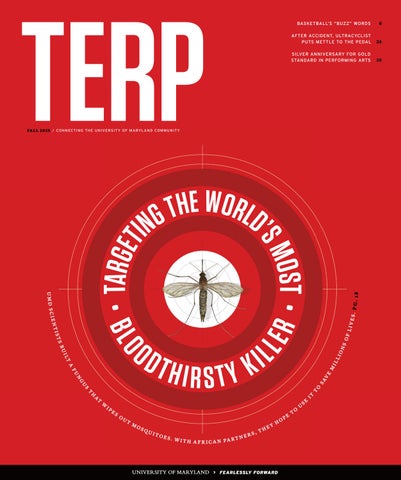

18 Targeting the World’s Most Bloodthirsty Killer

UMD scientists built a fungus that wipes out mosquitoes. With African partners, they hope to save millions of lives.

BY CHRIS CARROLL

24 Mettle to the Pedal

When his Olympic dreams on the bike came crashing down, Ryan Collins ’16, MBA ’20 struggled to even hold the handlebars. Now he’s racking up world records as an elite ultracyclist.

BY ANNIE KRAKOWER

30 A Silver Anniversary for the Gold Standard in Performing Arts

For nearly 25 seasons, The Clarice has celebrated theater, music and dance. Terp takes a photographic tour of the landmark center’s first act.

BY SALA LEVIN ’10

An alumna and UMD staffer and her husband learned that they’d been selected as adoptive parents and could bring home their baby in 10 days. They had nothing a newborn would need—until the outpouring from coworkers. go.umd.edu/terpbaby

For more than a half-century, the College Park apartments were synonymous with “Animal House”style debauchery. We revisit their notorious history. go.umd.edu/knoxboxes

higher education research is one of our nation’s crown jewels. Discoveries and innovations in fields spanning space exploration, quantum science, personalized medicine and food safety have exponentially improved our quality of life. And as a top-20 public research institution, the University of Maryland is at the forefront of maintaining this momentum and making real change for real people.

UMD entomologist and Distinguished University Professor Raymond St. Leger is doing just that through an ambitious project featured in this issue of Terp (page 18) to stop mosquitoes from spreading malaria and other deadly diseases. Bringing together a global team with funding from the federal government, St. Leger is pioneering the use of a genetically engineered fungus to target and kill the insect. This research has the potential to solve one of humanity’s most enduring public health challenges and save millions of lives.

Terps are also serving the public good by shaping the future of artificial intelligence. AI holds tremendous promise as a tool to advance industry, government and society, and we are making sure our students have the education and experiences necessary to lead the next-generation workforce. One of our latest projects is using AI to measure K-12 students’ engagement in math classes across the country and create a new database for scholars and educators to identify best practices (page 17). Led by the UMD College of Education in partnership with the Gates Foundation and Walton Family Foundation, this three-year initiative could help stop the decline in test scores since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Elsewhere in this issue, we profile Ryan Collins ’16, MBA ’20, who overcame horrific injuries to become a world record-breaking ultracyclist (page 24); celebrate the 25th anniversary of The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center (page 30); and introduce new leaders of our athletic department and men’s basketball team (pages 5 and 6).

I hope this issue gives you a full sense of how the University of Maryland is continuing to set a new standard of excellence and impact. I invite you to come back to campus and see it for yourself at Homecoming, Oct. 27-Nov. 1.

Sincerely,

Darryll J. Pines

President, University of Maryland

Glenn L. Martin Professor of Aerospace Engineering

DARRYLL J. PINES

President

Advisers

ANNE BUCKLEY

Vice President,

Marketing and Communications

MARGARET HALL

Executive Director, Creative Strategies Magazine Staff

LAUREN BROWN University Editor

JOHN T. CONSOLI ’86 Creative Director

VALERIE MORGAN Art Director

CHRIS CARROLL

ANNIE KRAKOWER

SALA LEVIN ’10

KAREN SHIH ’09

JOHN TUCKER

Writers

LAUREN BIAGINI

CHARLENE PROSSER CASTILLO Designers

STEPHANIE S. CORDLE Photographer

JANNA SINGER-BAEFSKY Digital Asset Manager/Archivist

DYLAN SINGLETON ’13 Photography Assistant

JAGU CORNISH Production Manager

EMAIL terpfeedback@umd.edu ONLINE terp.umd.edu NEWS today.umd.edu INSTAGRAM.COM / univofmaryland LINKEDIN.COM/ school/ university-of-maryland FACEBOOK.COM / UnivofMaryland YOUTUBE.COM /@UofMaryland THREADS.COM /univofmaryland X.COM /UofMaryland

The University of Maryland, College Park is an equal opportunity institution with respect to both education and employment. University policies, programs and activities are in conformance with pertinent federal and state laws and regulations on nondiscrimination regarding race, color, religion, age, national origin, political affiliation, gender, sexual orientation or disability.

I really enjoyed the magazine’s cover story. What a difference a few years make in tech tools. When I was a student in College Park, I took a few computer programming classes. To run a program back then, you punched it up on Hollerith cards, including the Job Control Language, took the stack of cards to a service window in the computer center, and waited a day for the results. Today’s kids have 10th-gen computers and AI. Wow, just wow!

—KENNETH RICHARDSON ’75, M.A. 77, TWIN LAKE, MICH.

Reading the article brought back memories of my time as a campus tour guide in the early ’80s. Back then we were paid; it was part of my job as an admissions representative. There were no auditions, no facts to memorize (and no Terps T-shirt, either). Each rep could say whatever they wanted on a tour!

—JULIE WAXMAN LISS ’82, POTOMAC, MD.

had ever seen, like shut-down-thecampus worst.

A few months ago I drove over to campus. I hadn’t been back in about seven or eight years, and oh my! I knew they were building tracks for the [Purple Line] and that they had moved the M circle a while back, but there were so many other areas that were unrecognizable! I still think it’s a pretty campus but it’s changed a lot—as has College Park!

—ERIN DILLENBECK ’89, VIA INSTAGRAM

Anne Kirwan was my tour guide in 1987. When we found out who she was (her father was UMD’s president), my father said, “Don’t ask anything dumb or they’ll revoke your admission. Better yet, don’t talk at all!” Thanks, Dad! I remember she was so sweet and incredibly well versed about everything on campus. The University of Maryland will always hold a special place in my heart.

—BONNIE WEINBERG ’93, VIA INSTAGRAM

I was an Imager in the early ’90s. My partner was a Testudo (no, he didn’t dress for the tour). We had red cardigans with white “M”s then. One of my favourite campus organisations!

—DONNA DEWICK ’93, VIA INSTAGRAM

My tour guide, when I told him I was from NY, pointed to a tree and jokingly said, “That’s a tree!” Ha ha. I then said, “Not NYC, but Syracuse.” “Oh you’re going to love it here,” he said, “It never snows!” That winter was one of the worst the area

I did want to let you know that the Cellar was definitely going strong through at least 1996 (the article mentions it closing in the 1980s). A friend gave the graduation address that year at Cole Field House, and he reflected on his fond memories of the Cellar. At the end of the night, every night they would play “December, 1963 (Oh, What a Night).” I’ll never forget singing along after a few too many drinks. I was also wondering about Penguin Pizza—another honorable mention? I hung out with some Maryland basketball players there; they were celebrities around campus but always kind to all of the students. Thank you for creating such a special article. Keep up the great work! I hope you’ll write a sequel.

—BRIAN

MARQUARDT ’96, LOS ALTOS, CALIF.

We love to hear from readers. Send your feedback, insights, compliments—and, yes, complaints—to terpfeedback@umd.edu or to: Terp magazine

Office of Marketing and Communications 7736 Baltimore Ave. College Park, MD 20742 a

DRESSED IN ADORABLE, tiny academic regalia, Kermit the Frog encouraged University of Maryland graduates to embrace life’s “big, messy, delightful ensemble piece” during the 2025 Commencement ceremony in May.

The cuddly creation of Jim Henson ’60 drew uproarious applause throughout his “Kermencement” address, interspersed with trademark heart and humor.

“I can tell you’ve all worked your tails off,” he said to thousands gathered at SECU Stadium and many more who watched online. “And as a former tadpole, believe me, losing your tail is a pretty big deal!”

“Life is like a movie. Write your own ending.”

—KERMIT

UMD WELCOMED ITS new Barry P. Gossett Director of Athletics on July 15, just two weeks after a landmark NCAA agreement to compensate student-athletes went into effect. It’s the very definition of a game-changer.

Jim Smith, who most recently served as senior vice president of business strategy for the Atlanta Braves, now oversees the Department of Intercollegiate Athletics enterprise of 20 teams, 250 full-time staffers, practice and competition facilities, and TV contracts, all supporting more than 550 student-athletes.

“As college athletics rapidly evolves, Jim brings valuable administrative and business experience, plus the energy, vision and passion to lead our athletics program to new levels of success and impact,” says UMD President Darryll J. Pines.

Smith says he’s excited to build upon Maryland’s excellence at a pivotal time for intercollegiate

athletics, with a sharp focus on student-athletes’ health and wellbeing and academic success. But his No. 1 priority, he told legendary Terps broadcaster Johnny Holliday, is to bring in more revenue to cover the $20.5 million annually that UMD has committed to paying its student-athletes.

“What we hope is going to happen during my time here is the revenue is going to increase,” he said. “We’re going to be highly competitive in all our sports in the Big Ten, because we already have the coaching component here. Coaches here are great, no question. It’s really amazing talking to them and hearing their passion for Maryland. So that part is figured out. The rest of the puzzle is what we have to do together.”

See the full interview at go.umd. edu/SmithOnHolliday.

A ONE-STOPLIGHT town might sound sleepy, but a new traffic signal at UMD instead will illuminate its growth.

Nearly 170 years after the university’s founding, the first stoplight in the campus core became operational July 31 at the intersection of Campus Drive and Regents Drive near the “M” as part of the state’s Purple Line light-rail project.

It’s among three new permanent traffic signals coming to the campus at reconfigured intersections to help accommodate future light-rail train traffic in a bustling community of 55,000 faculty, staff and students.

The other two signals are at the intersection of Union Union Drive and Alumni Drive and at the new intersection of Campus Drive and Rossborough Lane east of Baltimore Avenue.

The Purple Line, when completed in winter 2027, will extend from New Carrollton in Prince George’s County to Silver Spring and Bethesda in Montgomery County; five of the 21 stations will be on or around the UMD campus. With direct connections to Metrorail, Amtrak and MARC, the Purple Line will provide more accessible and reliable transportation for Terps.

As the FinaL GaMe clock was ticking toward zero during last season’s March Madness, Buzz Williams was warming up for a different kind of hoops whirlwind.

Announced as the new University of Maryland men’s basketball head coach in early April, he had to fast-break into building a new Terps team. In this new era of the transfer portal and student-athletes getting paid, they’re bouncing between schools far more frequently to score the best opportunities.

“It’s been incredibly busy—in a good way,” Williams says. “This is my first time as a coach that we’ve had to construct an entire roster. … That’s just how the model of college

athletics has changed. Our staff has been exceptional trying to find the right people.”

Williams replaces three-year coach Kevin Willard, who decamped to Villanova just after the Terps’ March Madness run ended in the Sweet 16. Coming to College Park after six seasons at Texas A&M and prior stints at Virginia Tech, Marquette and New

Orleans, Williams guided programs to 11 NCAA Tournaments, including four Sweet 16 appearances and one Elite Eight.

A father of four, he applies a family-first mentality to the role and embraces the communities he’s part of. That’s exemplified by his Buzz’s Bunch initiative, which offers a summer basketball camp and fall game to local children with special needs.

“Finding the right person to lead Maryland men’s basketball was critical to the continued success of our program, both on and off the court,” UMD President Darryll J. Pines says. “With an exemplary record of competitive success and a demonstrated commitment to providing leadership and development to our student-athletes, Coach Buzz Williams is the ideal coach to lead us forward.”

Hot on the recruiting trail this spring, Williams looked for not only talent but intangibles like emotional intelligence, then worked with his newly assembled crew to set the team’s tone ahead of the season opener in November.

Williams, who earned the nickname Buzz as an energetic student assistant at Navarro College, gave Terp a glimpse of the gameplan by sharing a few of his “Buzzwords.”—aK

Your coaching style? Passionate

Your reaction to getting the job at Maryland?

Your first impression of the area? Lots to do

Your favorite quality in a player?

The attitude you want your team to have?

The feeling after an NCAA Tournament win?

How you respond after a tough loss? Hunger

What you like to do post-game? Shower

Your mindset going into your first UMD season? Thoughtful

What Maryland basketball means to you?

MARYLAND’S NEW MEN’S basketball head coach isn’t the only development that has Terps excited this season. Both the men’s and women’s teams celebrated the September opening of the highly anticipated Barry P. Gossett Basketball Performance Center.

Located adjacent to the Xfinity Center, the 44,000-square-foot building features a practice court, a strength and conditioning facility, expanded locker rooms, training areas with hydrotherapy, space for film study, and lounges and offices for both teams’ staffs.

Former basketball locker rooms and

offices now freed up in the Xfinity Center will be redesigned to benefit other Terps sports teams.

The center, named for the lead donor, a longtime UMD supporter, is the latest completed project in Maryland Athletics’ Building Champions campaign to renovate and enhance facilities for every UMD student-athlete.

“It’ll be great not only for our players,” says new men’s basketball head coach Buzz Williams, “but it’ll also be great for our staff, great for recruiting and great for every aspect of the program.”—AK

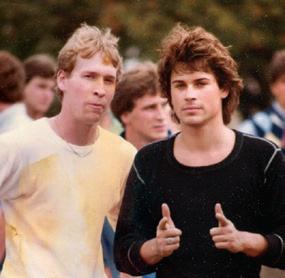

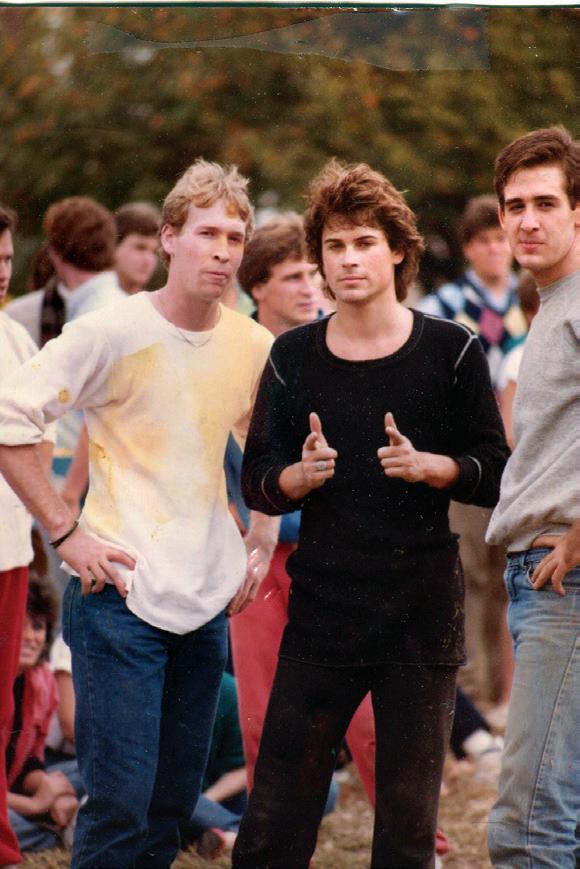

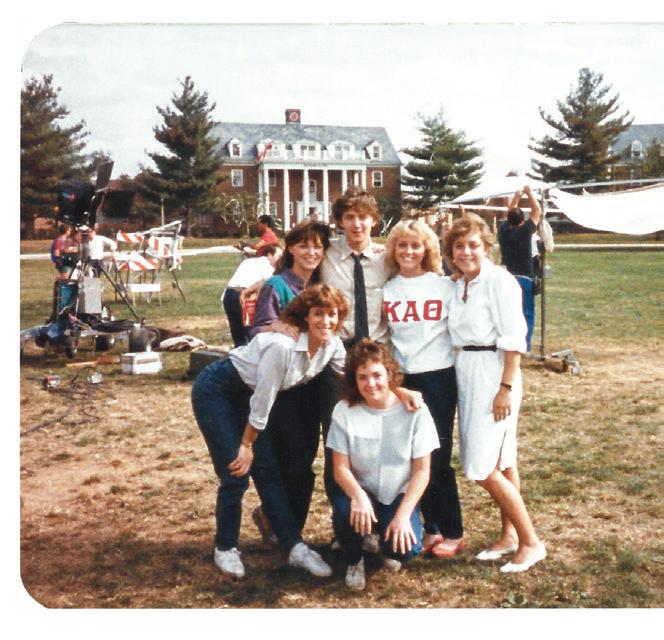

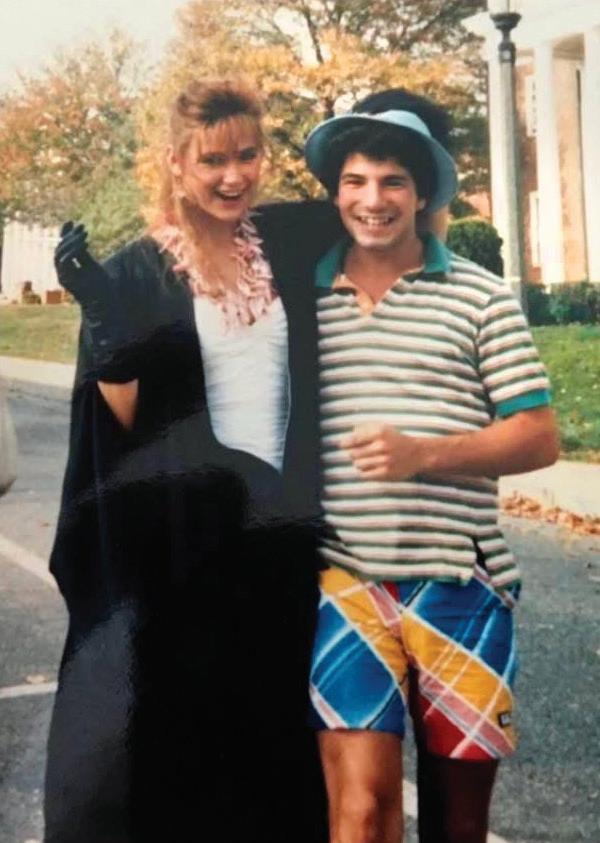

iG Out thOse COLORFuL Jams shorts, blast some synth-pop and plug in your crimper—it’s time for a little trip back to the 1980s. Decades before Demi Moore staged an Oscar-nominated comeback and Rob Lowe became a network TV staple, the Brat Pack stars were in College Park, strolling by UMD’s classic red brick and white-columned buildings.

D“St. Elmo’s Fire,” the hit coming-of-age movie released in summer 1985, also starred Emilio Estevez, Andrew McCarthy, Ally Sheedy and Judd Nelson. It followed the exploits of

recent Georgetown University graduates—but the school wouldn’t let them film there.

Instead, the cast and crew took over Fraternity Row for two days in Fall 1984 and recruited students as extras. UMD made the final cut in three scenes: the iconic opening shot of the full cast in graduation caps and gowns (below), a football scene on the field in the horseshoe and a chat between Lowe’s character and his wife with Memorial Chapel visible in the background.

As rumors abound of a sequel, Terps recount their favorite memories.—Ks

JAY HERGENROEDER ’86

Hergenroeder was plucked by the director out of a group of extras to greet Lowe as his character entered his old frat house—a scene that got a raucous reception at the sold-out screening at Hoff Theater. The cast members were nice, he recalls, especially Estevez, but Moore made the most unforgettable impression when she caught one of Hergenroeder’s fraternity brothers staring from the roof of their house: “She then proceeded to moon him!”

ROBIN MANOUGIAN ’87

“I was at dance team practice across the street with the Mighty Sound of Maryland,” she says. “I remember someone from production coming over and saying, ‘Can you guys not play right now?’”

LISA CLAPS USHER ’86

“The one day I skipped class ended up being unforgettable,” says Usher, who gathered Kappa Alpha Theta sisters for a photo with McCarthy. Clockwise from top left: Kristi Baker ’87, McCarthy, Jana Ifkovitz Rizzo ’84, Usher, Kelly Brady and Marlene Sadowsky Aisenberg ’86.

HOWARD SCHACTER ’87

Schacter filmed for a day and a half next to Lowe, which required over 30 takes of running and throwing a football.

The Phi Sigma Delta member recalls, “The crew used our house for bathrooms, and one of my fraternity brothers went into a shower and realized he was next to Andrew McCarthy!”

ERIC PLATT ’85

“We got paid almost $100 a day, which was big money back then—good money for the ’Vous,” he says. “During the actors’ lunch break, I eyed Demi Moore struggling to open a bottle of cranberry juice. I went over and gave the damsel in distress a little help.”

MIGUEL LOPEZ ’87

The cast was just outside the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity house, “and my friend Rene from Kappa Delta sorority, who had a camera, told me, ‘Go take a picture with (Moore).’… It’s a fun (and very embarrassing) photo I’ve kept all these years.”

A $2.85 MILLION DONATION from alumnus

Brendan Iribe will boost support for UMD computing majors and local middle and high school students through experiential learning, scholarships and professional development programs.

The new Computing Catalyst will continue the university’s efforts to cultivate an inclusive computing community at UMD It will be a unit in the Department of Computer Science with additional funding from the Institute for Advanced Computer Studies and the College of Information.

Tamara Clegg, an associate professor in the college, will lead the Catalyst.

Iribe’s latest gift establishes the Dr. Jan Plane Endowed Program Support Fund in Computer Science, honoring the principal lecturer emerita of computer science who pioneered the university’s K-12 outreach programs in computing. He previously donated $30 million to help build the Brendan Iribe Center for Computer Science and Engineering, made gifts to support tech-related experiential learning opportunities for local K-12 and UMD students, and endowed a scholarship fund and professorships.

He said that Plane’s launch of CompSciConnect, a three-year summer camp that introduces middle schoolers to computing, and her “compelling vision to support women and so many others in computing” ignited his commitment to this initiative.

“Collaborating with her has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my career,” says Iribe, co-founder of the artificial intelligence digital voice startup Sesame. “I’m thrilled to see her legacy live on and inspire others.”

Plane, who retired in 2022 after 33 years at UMD, touched the lives of thousands of students from elementary to graduate school. Thanks to Iribe’s gift, a student lounge in the Iribe Center will also be named in her honor.

“He is a true advocate for broadening participation in computing and improving the quality and quantity of computing education at all levels,” she says. “I’m so grateful that he believes in what we do and what we’ve accomplished—his commitment to continuing this work means everything.”

—ABBY ROBINSON

THINK YOU NEED a big red barn and acres of soil to have a successful farm? A different type of agriculture is taking root these days, and a UMD researcher is demonstrating how new adopters can make sure their plans go swimmingly.

Jose-Luis Izursa, senior lecturer in the Department of Environmental Science and Technology (ENST), oversees a recently opened 1,200-square-foot aquaponics greenhouse near the Xfinity Center, where colorful trays of lettuce grow above 200-gallon barrels of meaty tilapia and baby bluegill, as well as a smaller version in the Animal Science Building with goldfish.

Aquaponics combines aquaculture, or fish farming, with hydroponics, growing plants in water instead of soil. Fish produce waste, which is pumped through filters where bacteria break down ammonia into nitrates that provide nutrients for the vegetables, creating a sustainable, closed-loop system. The practice uses just a tenth of the water of traditional agriculture, can be set up in urban or space-constrained areas, and can grow food year-round.

“Aquaponics is a good alternative, especially in areas like Maryland and D.C. where land is very expensive,” says Izursa, who has already donated extra greens to the Campus Pantry, and hopes to bring tilapia to Dining Services.

Student workers and volunteers help him run the labs; he had about 15 this spring from departments across campus. They feed the fish, check pH and oxygen levels, and monitor experiments, including the effects of substituting black soldier fly larvae for commercial fish food and how different-sized air bubbles influence fish and veggie health.

The lab has become a teaching tool, not only for ENST students, who created a mobile system that can be taken to fairs and K-12 classrooms, but for farmers and others through a UMD Extension class.

“I want to put Maryland on the map for aquaponics,” Izursa says.—KS

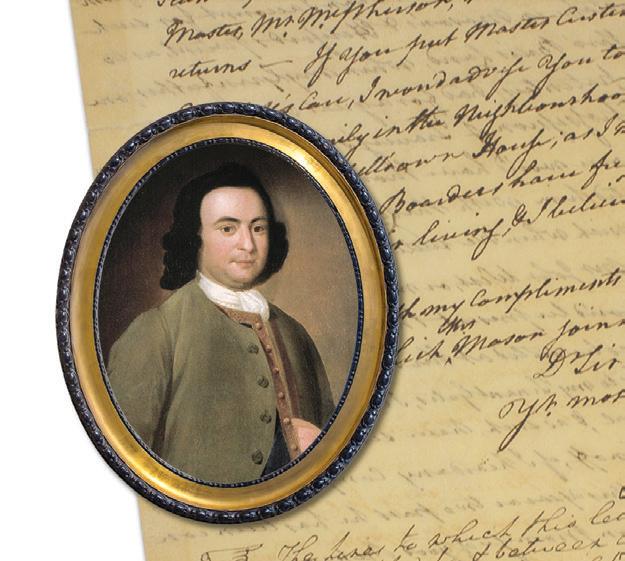

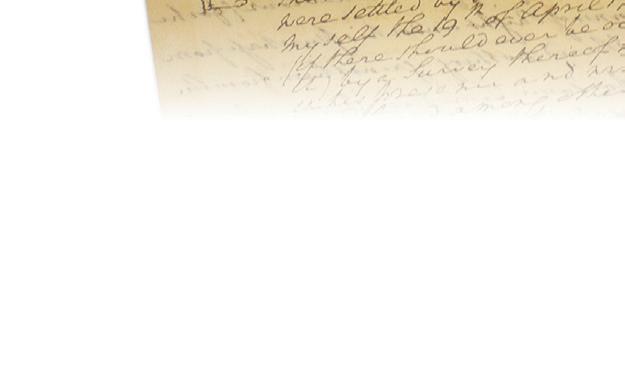

WORKinG in GeORGe MasOn’s 18th-century Georgian mansion overlooking the Potomac River, Nicholas Gentry MLIS ’26 typically spent his days deciphering and transcribing the cursive script of the Founding Father and his pen pals. The digital archives fellow at Gunston Hall, Mason’s home and now a museum commemorating the Virginian’s life, didn’t think much was out of the ordinary when he picked up a letter between Mason and his sort-of neighbor, George Washington.

But after scouring the online repositories of Revolutionary-era figures’ archives that day, he confirmed that the 1768 letter had never been digitized, giving Gentry a chance to edit the historical record.

He built a website for the document—largely about a land dispute between the two men, whose estates are roughly 11 miles apart—and shared it with the staff of the Library of Congress’ George Washington papers in February.

“It’s exciting to be hands-on—in a very safe, archivally friendly sense—with a document that old, and one that has George Washington’s handwriting on it,” says Gentry. “It was even more special to realize that you’re sort of rediscovering it.”

The letter, which is one document containing both Mason’s original and Washington’s response, hadn’t gone entirely ignored for 250 years. In 2012, Gerard Gawalt, a specialist in American history at the Library of Congress, printed the letter in his self-published book, “George Mason and George Washington: The Power of Principle.” Ensconcing the letter in an online archive allows a much broader swath of people to see it in a way “that will help protect it for the long term,” says Kate Stier, senior curator and head of collections at Gunston Hall.

It’s the second gem Gentry has uncovered since starting the position last September; he found another short letter between Washington and Mason— discussing recommendations for a cook at the presidential residence—stuck to the lid of an archival box.

Mason gained prominence as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where he refused to sign the fledgling nation’s government charter, primarily because it lacked a bill of rights. In 1776, he had authored the Virginia Declaration of Rights, which eventually served as a model for the Bill of Rights added to the U.S. Constitution.

The longer letter found at Gunston Hall includes personal tidbits in addition to discussion of property lines. Mason offers suggestions for who Washington might hire as a schoolteacher for his stepchildren: “If you put Master Custis under Mr. Campbell’s Care, I wou’d advise you to board him in some Family in the Neighbourhood, rather than in Mr. Campbell’s own House; as I know that Mr. Campbell’s Boarders have frequently complain’d of their living, & I believe not without Cause,” wrote Mason.

Gentry has sussed out other details about Mason’s exacting personality through his work at Gunston Hall. “If you went out today and got lunch with George Mason, he would instantly send you a Venmo request,” he says.—sL

ON A CLOUDY JUNE MORNING with air as moist as a devil’s food cake, Frank and Larry are running late. It’s their shared birthday, and the scores of people gathered on the Paint Branch Trail in College Park are waiting to serenade them. Meanwhile, a trio of tweenaged boys erupts in laughter when one realizes he’s wearing two similar but undeniably different shoes.

Footwear foibles aside, it’s a typical Saturday for devotees of College Park’s parkrun, where camaraderie has helped turn this offshoot of an international movement into the biggest of its kind in North America.

Born in the United Kingdom in 2004 and now operating in 22 countries, parkrun is a free 5K that takes place at the same time, on the same course, every week. Its volunteer organizers include University of Maryland faculty members Andrea Zukowski and Colin Phillips, a married couple who started the local parkrun in 2016.

Zukowski, a research scientist in linguistics who’d previously been “sedentary my whole life,” discovered a love for running at age 49 and wanted to give others a chance at the same revelation.

At first, roughly a dozen people regularly turned out. Today, some 200 show up at the starting point on the Paint Branch Trail every Saturday at 9 a.m. Many stick around afterward for coffee and brunch at The Board and Brew.

Social connections are key to parkrun. “You’re running for the friends around you,” says math Professor Larry Washington.—SL

SWAPPING YOUR JUICY STEAK or crispy chicken with a plate of stir-fried insect larvae or crunchy grasshoppers might sound like an invitation to skip dinner. But what if you could just mix some cricket flour into banana muffin batter, or replace a squeeze of lemon with a sprinkling of citrusy ants?

While people have consumed bugs for millennia, including about 2,000 species around the world today, Americans lag in accepting the protein-rich critters into their diets. Easing them into the practice, known as entomophagy, is the way to go, says entomology doctoral student Helen Craig ’22.

“My philosophy on eating insects is, why would you jump into the deep end?”

She and three undergraduate students in entomology Professor Bill Lamp’s lab researched the environmental, nutritional and economic benefits of eating insects. They spoke to experts, presented to peers and even tested bug recipes themselves. They published an article in American Entomologist this spring.

Ground into flour—and already raised in large quantities for pet food—these are the easiest entry point into entomophagy. They can be incorporated into smoothies or baked goods or dried and sold in cotton candy and lasagna flavors, all of which Craig and Hensley offered to undergrad classes. Students were willing to try at least one item; repeated positive exposure was key. “New food is scary,” says Hensley. “So how can we relate this type of diet, eating insects, to things like sushi and lobster, which are now seen as lavish, fine dining?”

past raising

GRASSHOPPERS One of the easier bug dishes to find in the United States—a restaurant adjacent to UMD serves them—“tacos de chapulines” contain fried or toasted spiced grasshoppers and are a popular Mexican street food. The caveat: A protein in their exoskeleton, chitin, which is found in many insects, could trigger a reaction in people who are allergic to shellfish.

methane. (In fact, some even eat rotting food,

Craig and biological sciences major Maya Hensley ’25 chat about six types you could eat.—KS

“I’m a vegan, but I would eat bugs because it’s one of the most sustainable proteins out there,” says Craig. As Earth’s population surges past 8 billion, raising enough livestock to feed more and more people is becoming a challenge. Enter insects, which require significantly less land and water than cattle, pigs and chickens, and don’t produce harmful methane. (In fact, some even eat rotting food, decreasing greenhouse gas emissions.)

BLACK ANTS With a lemony flavor from formic acid, these tiny insects could be tossed into guacamole for a little zing, says Craig. “It’s like adding a little salt.” Ants are a popularly foraged food across Latin America, Africa and Asia, where large queens are particularly prized.

BLACK SOLDIER FLIES An abundant creature that eats compost and can be farmed in stacked containers, the fly is consumed at its larval stage, made into a powder or an oil. Previous lab experiments have shown that using black soldier fly larvae could decrease methane production in cattle digestion, and now, Craig is the first to study its effects in cows on farms, exchanging a small amount of soybean meal for powdered larvae in their feed.

BAMBOO WORMS These worms, which are actually the larvae of a moth, taste nutty and were used by Craig as a topping on brownies. High in protein and fiber, they’re often found in Southeast Asian dishes, deep fried. Like many insects, they are consumed whole, so there’s no waste— unlike with livestock, which have many inedible parts.

A RECORD AMOUNT of the world’s tree cover vanished last year, according to data collected by UMD, and the greatest destruction occurred in old-growth tropical forests, which fell at a head-spinning rate equal to 18 soccer fields per minute.

These dense, ecologically precious areas produce much of the oxygen we breathe, provide homes to still-mysterious creatures and potentially harbor plants that could contribute to cures for cancer or other diseases.

“There are more species we haven’t discovered in those forests than species we have,” says geographical sciences Professor Matt Hansen, who together with Research Scientist Peter Potapov leads the university’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) Lab. With help from team members Svetlana Turubanova and Alexandra Tyukavina, the lab partnered with the World Resources Institute for a May report showing a surge in fires both in the tropics and at high latitudes.

The GLAD Lab, which has released tree loss data yearly since 2013, has become a central resource in the fight to save these crucial resources, menaced from the Amazon to the Congo Basin by drought, rising temperatures and economic pressures.—CC

COCHINEAL This pink, cactus-hugging bug has been used as a makeup and food dye, including at chains like Starbucks, which got pushback in 2013 for incorporating the vibrant, FDA-approved colorant into its strawberry Frappuccino and desserts.

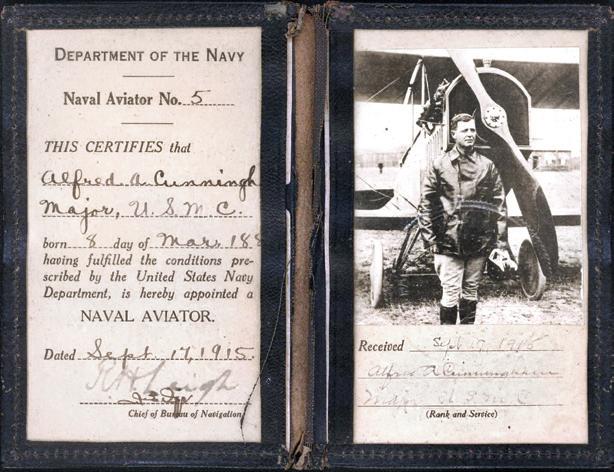

TBuffett Scholar Reflects on Role Model’s Retirement

he PhOtOGRaPh FROM 2005 (below) depicts a broadshouldered Warren Buffett surrounded by UMD students, handing his wallet to a grinning undergraduate who tugs at the hunk of leather, nonplussed at his seeming luck. But Clinical Professor of Finance David Kass, smirking off to the right side in the photo, says Buffett was just having fun while living out his famous Rule No. 1: Never lose money. (Rule No. 2? Never forget rule No. 1.)

“It was a photo op—he doesn’t really let the wallet go,” says Kass, displaying the keepsake soon after Buffett announced in May that he would step down as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, the company he turned into a $1.1 trillion juggernaut. Considered by many as history’s greatest investor, the

95-year-old will retire at year’s end but stay on as chairman, cementing a legacy that few know better than Kass.

The former senior economist for a variety of federal agencies is a foremost expert on the Oracle of Omaha, with his insights quoted over a hundred times by The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Bloomberg and others. His office is festooned with photos of the business titan and UMD students; a framed personal note graces the wall. In the classroom, Kass begins each lesson with a discussion of the news, often veering into Berkshire Hathaway territory. “It’s in my contract that I must mention Warren Buffett’s name at least once,” he quips.

Kass has accompanied students on visits to Omaha for private meetings with Buffett on four occasions since joining UMD’s faculty in 2004 and led them on annual pilgrimages to Berkshire Hathaway’s investor meetings, known as “Woodstock for capitalists.” In 2010, on Buffett’s 80th birthday, Kass launched the Warren Buffett

Blog, posting news and analysis.

This past February, as Kass studied Buffett’s annual shareholder letter, a short comment buried near the end jumped out: The investing icon was using a cane to walk. During a Business Insider interview, he suggested Buffett might announce his retirement during this year’s annual meeting. After the shocking revelation that day, the crowd of 40,000 erupted in appreciation, a moment captured on video by Kass near the front row.

The UMD professor will continue blogging about Berkshire Hathaway, the stock market and the economy while preaching Buffett’s philosophy: Buy and hold. Know your circle of competence. Look for a wonderful company at a fair price rather than a fair company at a wonderful price.

But Kass will also remember the private moments, when Buffett counseled students about life beyond money: “Follow something you’re passionate about,” Buffett once implored, a piece of advice Kass himself has stuck to. –jt

ASK THE EXPERT ADVICE FOR REAL LIFE

UNTIL 2022, it seemed that a chatbot’s highest calling was to lasso you to an e-commerce website until a customer service rep popped up to actually help. But recent “large language models” like ChatGPT, Claude and Gemini can write speeches, whip up computer code—even provide relationship advice.

The uninitiated are frequently surprised at what chatbots can do, says Assistant Professor Naeemul Hassan. To make sure those AI surprises are beneficial, the computational journalism expert offers tips on asking questions the right way (and that doesn’t mean saying “please”).—CC

GET SPECIFIC. If you have a precise vision—like a trip across Italy that must include seeing

certain artworks—unload everything on the chatbot. “In journalism, we have the five Ws, one H concept: ‘who, what, when, where, why—and how?’” Hassan says. “Try to include some of that when you make the query.”

OR KEEP AN OPEN MIND. Throw the query wide open if you’re just looking for ideas: “Provide artsy options for a life-changing Italy trip.” Chatbots have an uncanny ability to speedily parse mountains of online data to make interesting connections people often can’t, Hassan says.

LET AI HELP MAKE YOUR POINT. Chatbots aren’t just about creating. They can slice and dice text to order, like creating summaries and high-level overviews of complex

SCIENTISTS ENDEAVOR to put humans on Mars within two decades. Elon Musk wants to build a colony there. Jack Postlewaite, a UMD electrical engineering doctoral student researching deep space communications, envisions a day when Red Planet dwellers could stream “Good Morning America.”

Working in the lab of Clark Distinguished Chair Professor of Electrical and Computer

documents, Hassan says. If you’re writing for multiple audiences, they’re good at altering the tone and reading level while keeping the core message.

DON’T TRUST IT. Chatbots can be gregarious know-it-alls, but

Engineering Saikat Guha, Postlewaite has helped build a laser receiver, the “Green Machine,” that leverages quantum mechanics to extract light particles from extremely faint laser signals like those beamed from faraway satellites.

Converting these photons into coherent communication—not just GMA, but critical information to support Mars habitation—gets increasingly difficult as distance grows. The team, with funding from NASA, used a technique envisioned by Guha to achieve “superadditive capacity” to decode light-starved transmissions. Led by Assistant Research Scientist Chaohan

they frequently err, sometimes conjuring fictions known as “hallucinations,” prioritizing user acceptance over factuality or harboring deep biases. “They’re far from 100% accurate, particularly when logical reasoning is needed,” Hassan says.

Cui, the group presented the technology in April in Nature Communications NASA has increasingly experimented with laser communication, which uses less energy and bandwidth than radio frequency transmission. Scientists in 2023 used lasers to stream a 15-second cat video at broadband speed from 19 million miles away. The distance to Mars, by comparison, is 146 million miles—necessitating the souped-up quantum approach.

“Imagine you have a doctor on Mars who does an MRI scan, and you want to send it to Earth,” says Postlewaite, the study’s co-lead author. “That’s a big file.”–JT

FACULTY Q&A

CASEY DAWKINS

THE AMERICAN DREAM IS DEAD. Or it’s at least delayed, for recent college grads. According to a report earlier this year from mortgageresearch.com, they won’t be able to afford a house until 2034.

To solve the nation’s housing crisis, urban studies and planning Professor Casey Dawkins urges people to think smaller: Manufactured houses—homes built in factories and delivered to the site—are significantly less expensive and quicker to produce.

But these aren’t the flimsy, unattractive, double-wide trailers of half a century ago. Stylish new models are fitted with charming porches, gabled roofs and energy-saving features.

Dawkins talks about why housing prices got so far out of control, who might benefit the most from manufactured homes and what policy changes can make that possible.—KS

Why have houses gotten so expensive?

We simply haven’t been building enough housing to keep up with population growth. Since the foreclosure crisis (around 2008-10), housing production has stalled, and it took a dip again during the pandemic. A lot of factors play into that, from rising construction costs due to supply chain disruptions to land-use regulations that can stall production and inflate prices. On the consumer side, rising inequality and high interest rates have made it harder to afford a home.

How can manufactured housing help?

Labor costs to place these homes are lower than building on site, and constructing in a climate-controlled facility reduces the risk of weather damage. One study found that they could be 35-60% the cost of a traditional home, depending on size.

Who might buy these houses?

For first-time homebuyers, this is a really promising alternative for starter homes. The generation now graduating from college has lots of student debt, and what’s on the market is often large homes vacated by recent retirees. They could also be accessory dwelling units. As parents are aging, if it is easy to place a home in the backyard, why not do that?

What’s the future for manufactured housing?

We should address the low-hanging fruit in policy. People view this housing type as inferior and it feeds into NIMBY attitudes, so they oppose them at zoning hearings. States shape how this market is regulated. Maryland just passed a bill that requires local governments to treat manufactured housing the same as other housing, meaning they can’t prohibit it while allowing other single-family homes.

I don’t want to oversell it. My focus has been on the margins, where a little more housing built inexpensively could make a difference. We could scale up so they are 10% of all single-family homes.

INSIDE THE MIDDLE SCHOOL

classroom, a video camera swivels on its tripod while five microphones capture clues to the age-old question: How do you teach math to kids?

Recordings from this lesson and thousands like it across the country will be fed into an artificial intelligence (AI) program trained to spot instances of student engagement and the teaching practices that elicit it: Maybe a pupil explains her reasoning—“it can’t be divided because it’s a prime number!”—or raises her hand several times.

It’s the first half of a project, funded by a $4.5 million grant from the Gates Foundation/Walton Family Foundation and led by UMD’s Center for Educational Data Science and Innovation (EDSI) to create a massive database arming scholars and ed-tech companies with real-world classroom data to mine for best practices.

Elementary and middle-school math scores have tumbled from pre-COVID levels, widening the gap between high and low achievers as other countries leapfrog the United States in international rankings.

The three-year UMD effort, initially supported by a Grand Challenges Team Project Grant, blends AI with roll-up-your-sleeves rigor. The recordings will be made anonymous with technical wizardry, then turned into transcripts that educators will scour to flag examples of quality instruction. Those annotations will get fed into EDSI’s MPowering Teachers program and other AI systems to support effective instruction.

“There might be teaching aspects we didn’t know of that are really important for learning,” says the study’s lead researcher, education policy Associate Professor and EDSI Director Jing Liu. “The data open up this possibility.”–JT

Wine enthusiasts are increasingly filling their glasses with products from Maryland vineyards, spurring an eightfold growth in the number of wineries since the 2000s and generating billions of dollars in the state.

But unlike the dry, temperate climes of traditional wine regions of California or Italy, the DMV’s warm, wet summers invite fungus to thrive. If just 5% of a grape bunch is rotting, the product can be ruined, pressuring growers to apply fungicide liberally throughout the six-month growing season despite high costs, potential environmental threats and health risks.

Associate Professor Mengjun Hu, a plant pathologist who assists growers through the University of Maryland Extension, discovered a way to cut fungicide use while protecting quality. He spent two years culling diseased

grapes from more than 20 regional vineyards. In the lab, his team identified the pathogen responsible for most decay while understanding the control window of blight: the late growing season.

“For this type of rot, the crop isn’t vulnerable in the early season, so application then is unnecessary and ineffective,” says Hu.

Growers adopting his recommendation saw significant boosts in fruit quality.

He and his team further developed a mathematical model that predicts disease based on weather data, along with growth stage, which the Maryland Grape Growers Association incorporated into a digital tool for members. The model allows producers to pinpoint the best fungicide-application timing at their location for maximum effect. Those using the model can expect fungicide reduction by at least 30%, says Hu.—jt

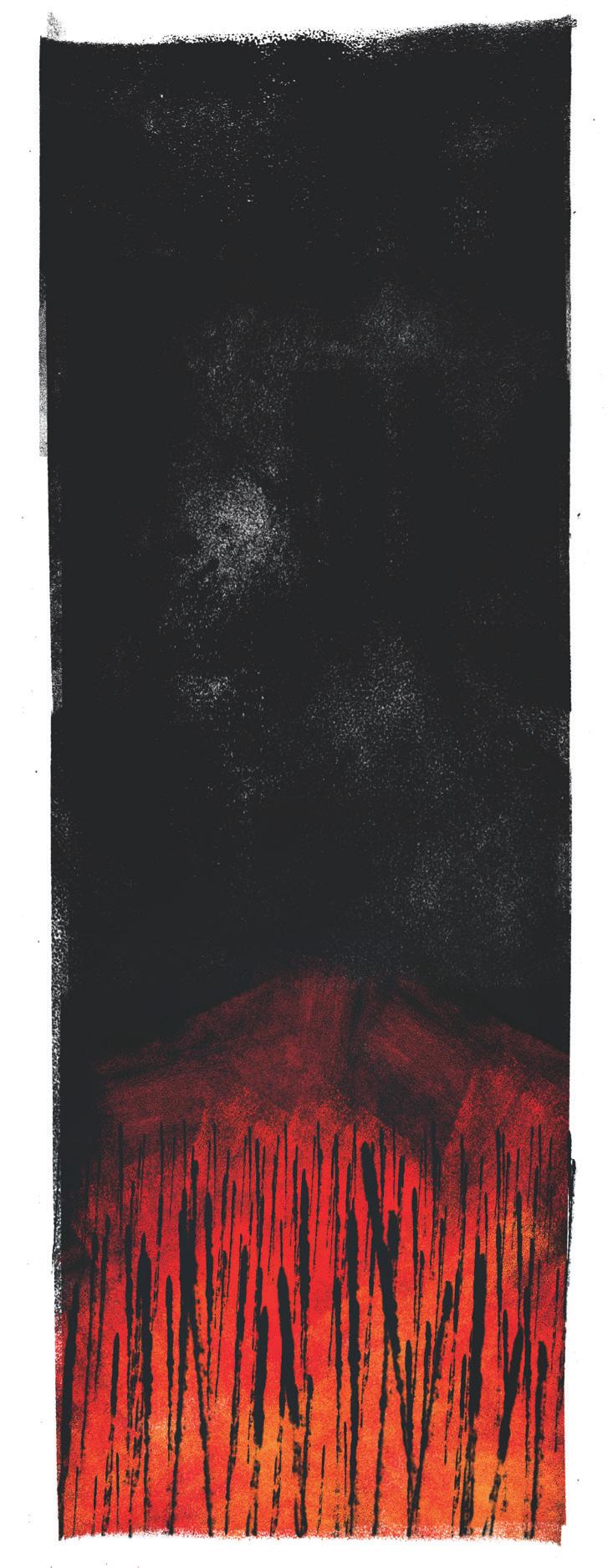

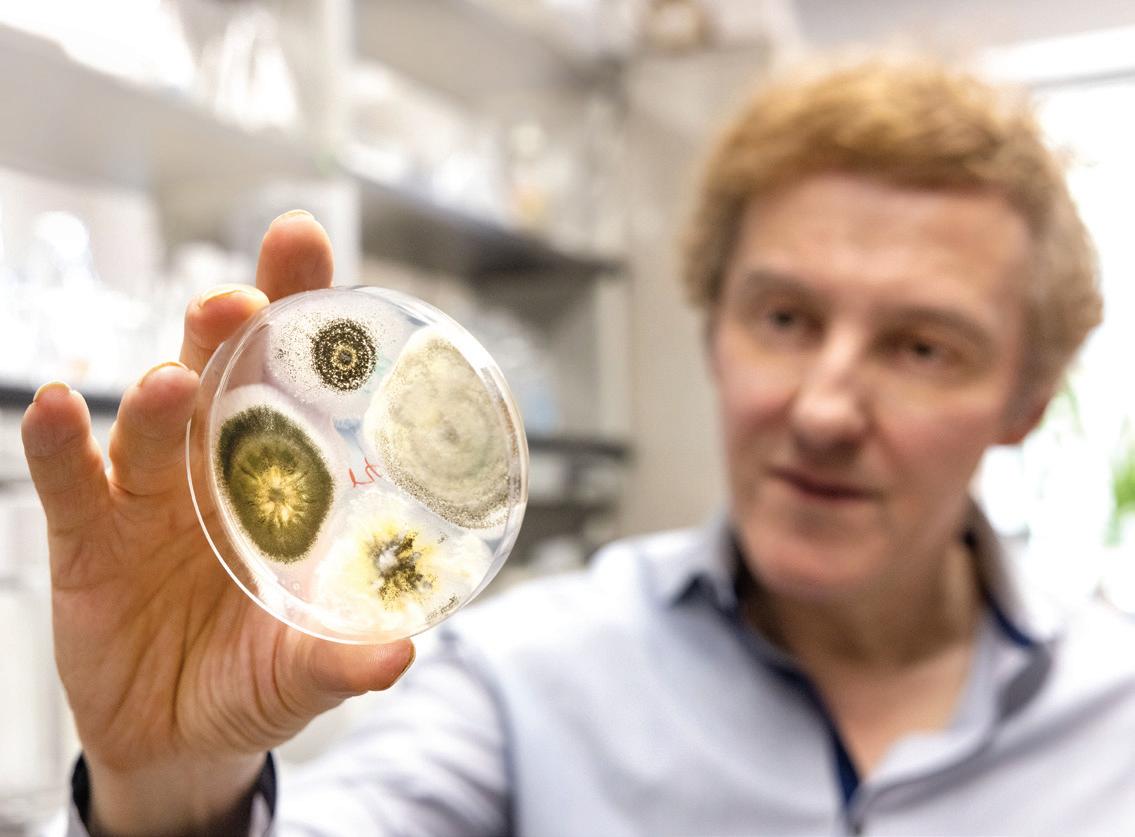

UMD SCIENTISTS BUILT A FUNGUS THAT WIPES OUT MOSQUITOES. WITH AFRICAN PARTNERS, THEY HOPE TO SAVE MILLIONS OF LIVES.

BY CHRIS CARROLL PHOTOS BY JOHN T. CONSOLI

APAIR OF BIOLOGICAL realities

helped shape Etienne Bilgo’s early life in the West African nation of Burkina Faso. He’d struggled to grasp one of them since first spending time with playmates: “Why was I alone when all my friends had brothers and sisters?”

He hadn’t yet reached high school when he decided scientific knowledge about reproduction might help him solve his parents’ fertility issues—painful in a culture that values large families. Though neither his mother nor father had progressed far in school, Bilgo soared to the top of his class, excelling in STEM courses.

This is where the second fact about his family’s biology might have given him an edge. While classmates often missed weeks of school with malaria, the mosquito-borne disease that sickens and kills more people per capita in Burkina Faso than almost anywhere else, he was spared.

It’s an arms race between the mosquitoes and us.”

Long after abandoning hopes for siblings, he learned why when he took a blood test before graduate school. Bilgo had inherited one copy of the sickle cell gene from his

mother, a fortunate mutation that granted them immunity. (Had his father also carried the gene, however, it would have caused sickle cell disease.) The test cast his early years in a new, more fortunate light.

“I was surprised, and I thought about all my friends being sick from malaria; even my dad would get sick,” Bilgo says. “Thinking about this was what brought me to the field of malaria.”

He eventually became an expert in the topic of reproduction—of mosquitoes, not humans. Now a medical entomologist at a government scientific institute in Burkina

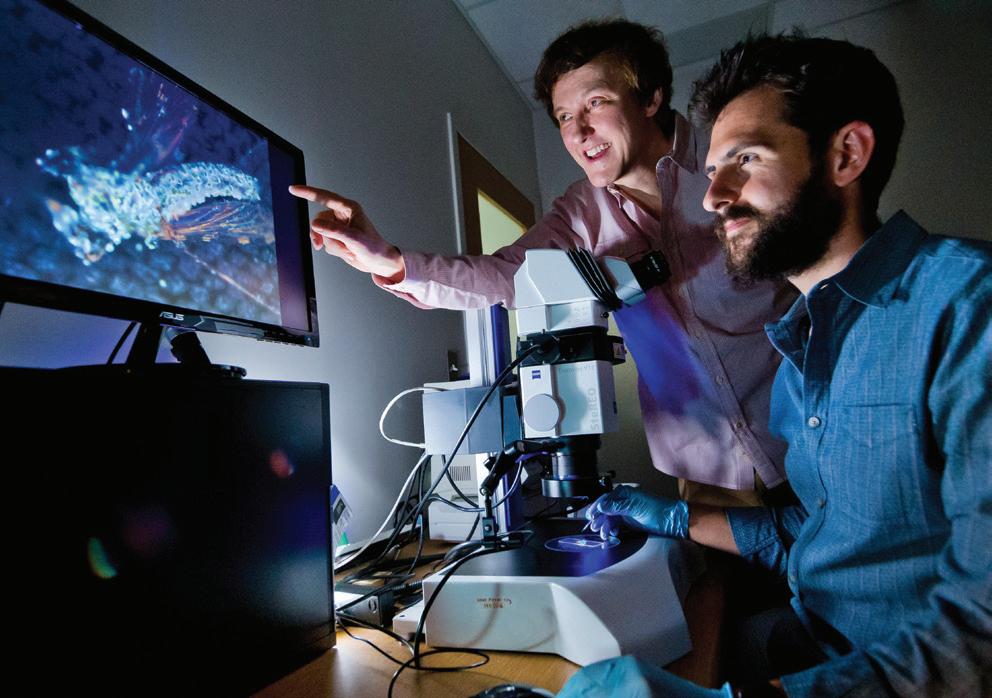

Faso, he was the lead author of a study in Scientific Reports earlier this year including University of Maryland researchers that created what amounts to a sexually transmitted disease for the pest.

The research was one of the latest steps in an audacious, nearly 20-year effort led by UMD entomologist Raymond St. Leger to deploy a lifesaving new weapon against the disease, supported by the National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies.

The Distinguished University Professor has used genetic engineering to turn a common insect-killing fungus species into what he calls a “living insecticide” supercharged by spider genes that produce toxic venom. This cross-species addition allows the “transgenic” Metarhizium fungus to knock out malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes so fast they can never spread

the sickness. In their STD paper, Bilgo, St. Leger and other members of an international research team showed this could be done by infecting male mosquitoes with the fungus to pass along during mating.

I don’t think many people outside of Africa can understand this burden.”

—ABDOULAYE

The impetus for the UMD research is a continuing global rise in insecticide resistance among mosquitoes, along with the increasing resistance to antimalarial drugs in the parasite that causes the disease. Chemicals that have saved millions of lives in recent decades are teetering ever closer to failure.

95% of yearly malaria deaths occur in Africa.

DIABATÉ HEAD OF MEDICAL ENTOMOLOGY AND PARASITOLOGY AT HEALTH SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE, BURKINA FASO

“It’s an arms race between the mosquitoes and us,” St. Leger says. “Just as they keep adapting to what we create, we have to continuously develop new and creative ways to fight them.”

IN THE RANKING of deadliest creatures that have ever preyed on humans, demographers agree that nothing—not sharks, sabertoothed tigers or even humankind with our growing array of weaponry—rivals the lowly mosquito.

SOURCE: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

While malaria is by far the most dangerous disease carried by some of the nearly 4,000 species, they also spread yellow fever, dengue, Zika, chikungunya and other serious diseases, most of which are now increasing globally.

The highest estimates indict mosquitoes for the deaths of half the humans ever born, perhaps 50 billion, mainly young children.

Proportionally, malaria fatalities today are far lower than historical highs, but 600,000 people still perish yearly of the disease. About 95% of deaths occur in

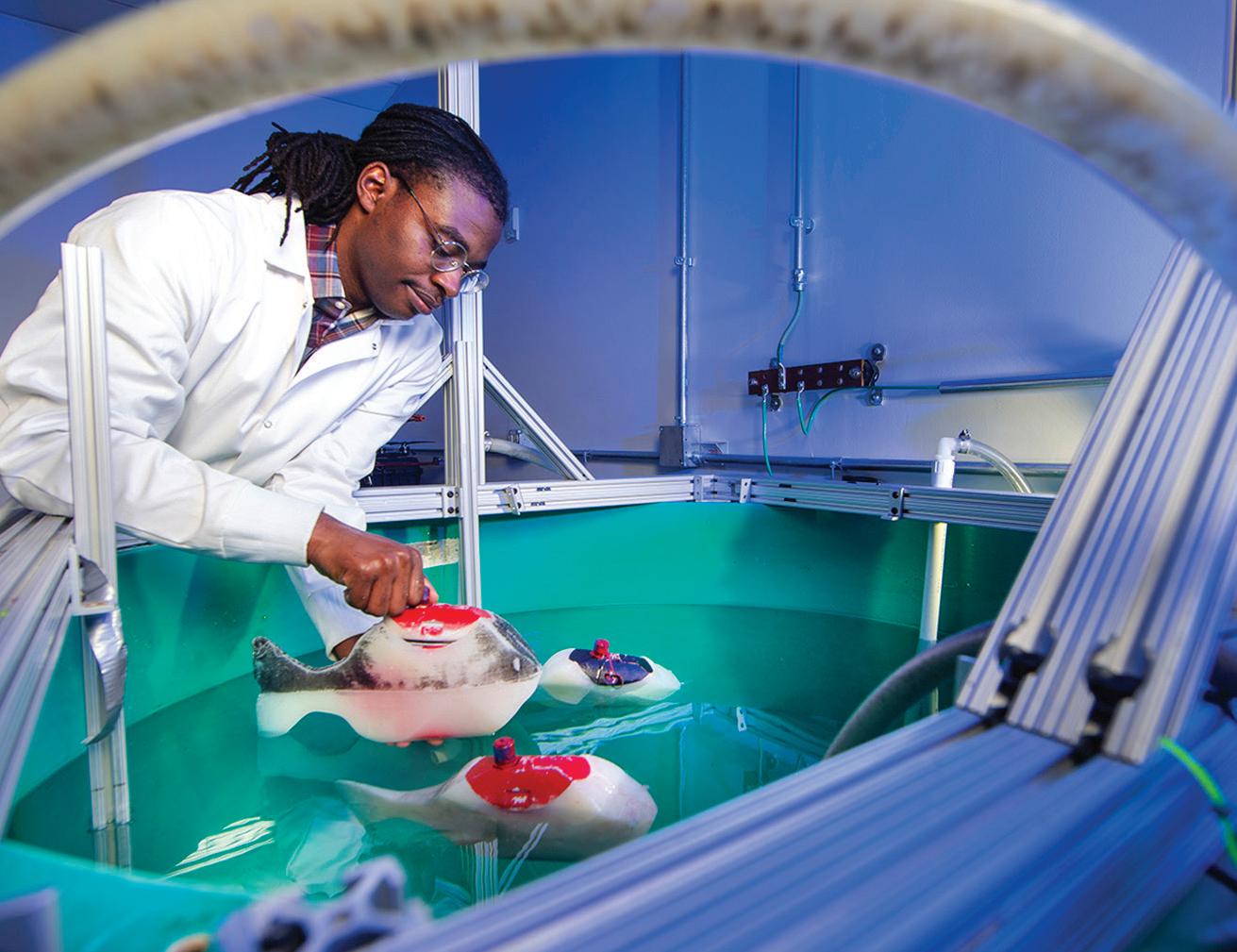

Etienne Bilgo, a medical entomologist in Burkina Faso who conducted research at UMD, records data on tests to control malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Bilgo has dedicated his career to fighting the insects that cause millions of illnesses and thousands of deaths in his country yearly.

Africa, as do most of the 250 million yearly infections; symptoms include fever, exhaustion and painful head- and body aches. The suffering is centered in heavily populated countries like Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, but little Burkina Faso, with only 23 million people, still tallies perhaps 10 million infections yearly and saw more than 16,000 deaths during 2023, according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) statistics.

“The statistics are big numbers, but don’t explain what it is like having lived all our lives with this disease,” says Abdoulaye Diabaté, Bilgo’s boss and the head of medical entomology and parasitology at the Health Sciences Research Institute in BoboDioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second-largest city. “There is a powerless feeling on the ground here that you can’t escape it. I don’t think many people outside of Africa can understand this burden.”

Diabaté is a global leader in malaria research, with scientific connections to major public health agencies, nonprofits and research universities around the world. As a collaborator in St. Leger’s research with the Metarhizium fungus, he coordinated his then-student Bilgo’s study at UMD in search of a fungal insecticide.

The institute is famous for developing insecticide-treated bed nets in the 1980s and ’90s; Diabaté assisted in some of the intense testing before the nets were distributed in growing numbers to the public earlier this century, when well over a million people died yearly from the disease. The bed nets stopped mosquitoes that fed on people while they slept, causing child death rates to plummet across Africa. But quickly, mosquitoes began showing resistance to the insecticides, and experts knew the reprieve would be temporary.

As public health efforts worldwide recalibrate amid recent funding cuts in the United States, long the global public health leader, experts say Africa may be a bellwether. The

U.S. eliminated malaria more than 50 years ago with DDT and swamp drainage, but an invasive strain of malaria-carrying mosquito that’s well adapted to city life, Anopheles stephensia, is expected to spread as rising temperatures put more of North America within its range. Since 2023, authorities have tracked nine locally acquired malaria infections in the United States—the first in decades. A case of falciparum malaria (the deadliest form of the parasite) was detected in Maryland.

“The more prevalent malaria becomes here in Africa, the more likely it is to affect Europe and the United States,” Diabaté adds. “You can be sure it won’t just stay here.”

THE WORLD DOESN’T WORK without fungi. During his postdoctoral work in the late 1980s, St. Leger began studying agricultural applications of species including Metarhizium, a type found worldwide that plays an important—and beneficial—role in the lives of plant species. With graduate student Gang Hu Ph.D. ’05, he showed that many plants would wither in its absence, unable to absorb enough nutrients from the soil or survive insect attacks.

(In recent research with former UMD postdoctoral researcher Weiguo Fang, now a regular collaborator based in China, St. Leger showed Metarhizium could effectively protect plants, along with the people and animals that eat them, from mercury poisoning caused by contaminated soil.)

St. Leger had been experimenting with genetically engineered versions that he suspected could be more effective and environmentally sound than chemical pesticides. But while serving on a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-backed committee in the early 2000s to look for technological approaches to aid African farmers, he had an epiphany. Instead of saving just crops, why not focus directly on protecting human populations?

“If I want to help people in Africa, I should help with this terrible burden of insect-borne diseases that is suppressing them—holding them back in innovation and weakening them economically,” he says.

Many forms of Metarhizium, rather than interacting with plant roots, infect and kill terrestrial and flying insects. St. Leger set out to modify the species to take on the specific mosquitoes responsible for spreading malaria and other tropical diseases.

With postdoctoral researcher Chengshu Wang (now another regular research collaborator), he soon submitted the first paper

Burkina Faso’s MosquitoSphere, built by the country’s Health Sciences Research Institute with funding from the U.S. government, provides a safe outdoor testing site for St. Leger’s mosquito-killing transgenic fungus.

about killing mosquitoes with a transgenic fungus in 2007 to Nature Biotechnology First, however, he had to counter worries about dangers not to bugs, but to people. Foreshadowing the fictional plot of “The Last of Us,” a popular video-game-turned-HBOhit-series about a fungal plague that wipes out society, reviewers suggested their innovation could comprise a “dual use” technology deployable as a weapon.

When finally published, the study showed that the addition of a neurotoxin from a scorpion increased the toxicity of the fungus to crop-eating caterpillars and a yellow fever-spreading Aedes mosquito by a factor of 22. But crucially, this surge in lethality left the “host range” unchanged, meaning the modified fungus remained dangerous only to the same creatures as the natural version—and no fungal zombies would be forthcoming.

In later experiments, St. Leger moved on to fungi that kill only mosquitoes; Bilgo had found the strain on insect carcasses in a small goat shed in Burkina Faso during his student days. Such precise targeting is one of the project’s layers of security; another is using toxins fatal solely to insects, while a third is ensuring that toxins activate only after the fungus has bored through the insect cuticle, injecting the poison deep inside.

An added benefit of using an existing “enemy” organism like fungi as an insecticide is that it should be more difficult for mosquitoes to become immune, versus establishing immunity to an inert, man-made product.

“The fungi have evolved their own strategies against the mosquitoes,” he says. Able to zig when the insects zag, “they’re an active player.”

WITH ITS MOSQUITO-KILLING bona fides established, it was time for the modified fungus to venture beyond a carefully controlled lab. Its inaugural “semi-field” trial played out in 2017-18 in a securely screened enclosure dubbed the MosquitoSphere, constructed by Diabaté’s institute in a small village near Bobo-Dioulasso with support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Designed to simulate places where people encounter mosquitoes, the facility has puddles for them to breed in, small houses in which to buzz around (and potentially meet their fate via various insecticides) and domestic animals to feast on.

In 2019, Brian Lovett Ph.D. ’19, St. Leger, Diabaté and Bilgo published a key paper demonstrating that Metarhizium, which the researchers were modifying with the venom from an Australian spider, could cause the collapse of a mosquito population, killing the 75% of insects that contacted the fungus in

the first generation and almost eliminating the second generation.

The results were promising, but the fungus would need a 90% kill rate to be useful. “It has to be shown it works not just in the sphere, but in the towns and villages,” Diabaté says.

The holdup now isn’t the need for further development of the modified fungus itself, St. Leger says. “Short of using synthetic biology to design a totally new pathogen from scratch, those science issues are done.”

A remaining step before moving on to open trials in towns across Africa—one required by the WHO and Burkina Faso’s government—is to present detailed plans and procedures for safely destroying insect populations with the fungus, along with solid evidence-based scientific studies pointing to likely success.

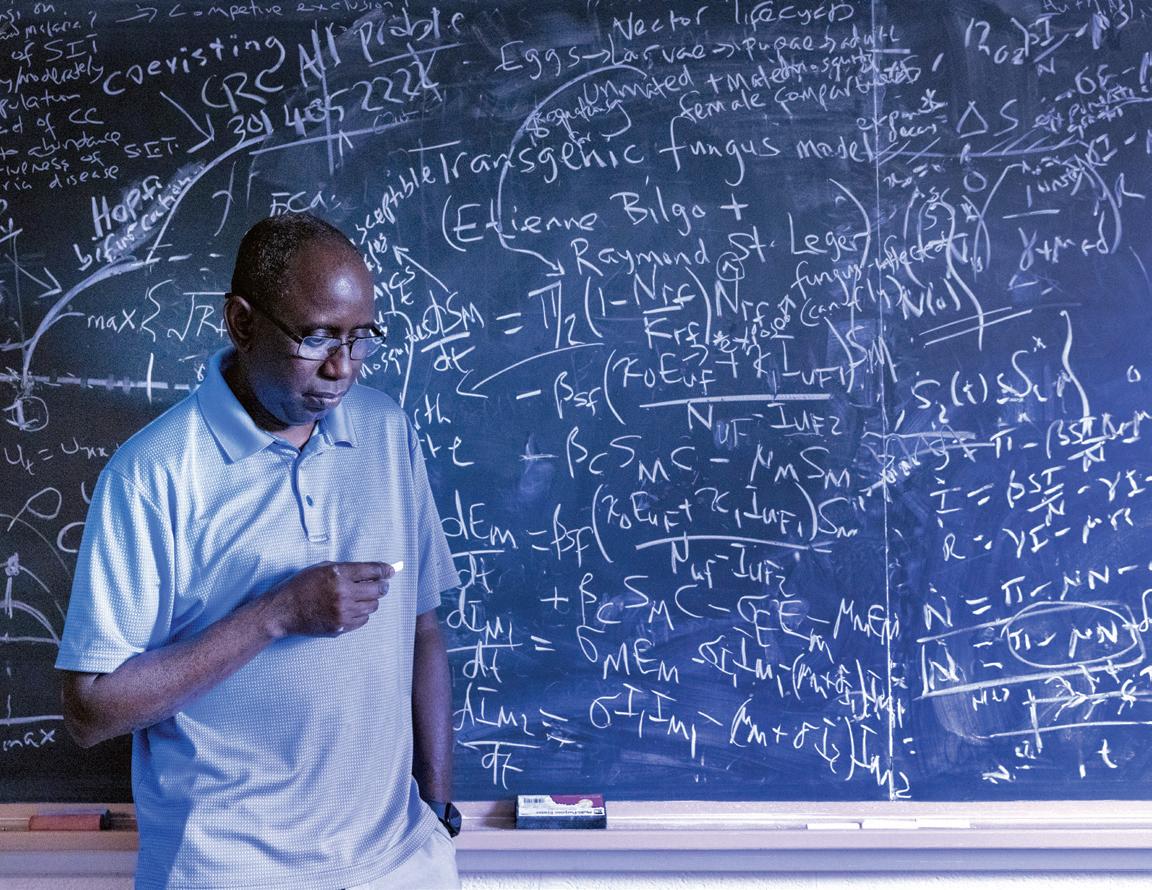

A study by another UMD collaborator, Distinguished University Professor Abba Gumel in the Department of Mathematics, could do just that. An expert on using mathematical modeling and analysis to research emerging and re-emerging infectious

diseases of major public health importance such as malaria, tuberculosis and pandemics like COVID-19, he’s in the odd position of fighting one pathogen by encouraging another.

“I had malaria many times when I was growing up, so it’s not hard for me to get interested in this research,” says Gumel, born in Nigeria, a country with the world’s highest burden of malaria.

In a forthcoming paper in Applied Mathematical Modelling that expands on the mosquito STD research released earlier this year, Gumel worked with his former graduate student, Binod Pant Ph.D. ’24, and postdoctoral fellows Arnaja Mitra and Salman Safdar to assess the utility of the transgenic fungus to combat Burkina Faso’s murderous mosquitoes. Their modeling study, co-authored with Bilgo, Diabate and St. Leger, shows how regular releases of male mosquitoes (which don’t bite) infected with the fungus can effectively suppress local wild mosquitoes, significantly reducing malaria among people.

One daunting finding from the mathematical modeling: To work, the transgenic

fungus approach requires 10 infected male mosquitoes to be released for every wild female mosquito in an area every few days for months. That adds up to many millions of mosquitoes until the disease is locally eliminated—a difficult public relations challenge.

“Male mosquitoes don’t spread diseases, but people see you releasing mosquitoes frequently and it makes them very nervous,” Gumel says. “The fungus-based approach wouldn’t be cheap or easy but if it reduces malaria burden, thereby saving lives in endemic areas, it would be well worth it.”

To achieve the 90% reduction in malaria cases and mortality, St. Leger and his collaborators aim to attack mosquitoes on several fronts with the transgenic Metarhizium. Targeting them through their reproductive behavior—with mating taking place outdoors—has the added benefit of slaying mosquitoes that have learned to seek prey outside to avoid pesticides in bed nets. Other new methods of applying the fungus would be less costly than mosquito releases; for example, a form engineered not just to kill, but to attract mosquitoes with floral odors, could be grown by residents at almost no cost and placed in traps or in the eaves of a house, St. Leger says. Yet another study has shown the transgenic fungus boosts the waning potency of chemical insecticides, indicating the new fungi can reinforce old approaches.

FEW PEOPLE FROM AFRICA’S malariaplagued regions can fully elude the disease’s ever-present danger—even those who are immune.

As Diabaté’s Ph.D. student, Bilgo studied for several months each year in St. Leger’s lab. This was in part because of the British American UMD scientist knew that for his potentially lifesaving, but controversial innovation to be accepted by those who stand to benefit, it would need introducing by respected African scientists.

I had malaria many times when I was growing up, so it’s not hard for me to get interested in the research.”

—ABBA GUMEL

DISTINGUISHED UNIVERSITY PROFESSOR OF MATHEMATICS

As Bilgo prepared to leave Burkina Faso for College Park in 2014, he suggested to his steady girlfriend, a fellow graduate student, that they talk to their parents about an official engagement when he returned in a few months. She agreed. Around this time, she received what was likely an unnoticed mosquito bite.

When she died just days after his arrival in the U.S., Bilgo had no money to return home to be with friends or family. St. Leger remembers him enduring the blow with stoicism,

then redoubling his efforts in the lab.

“Think about the mothers of the thousands of children in Burkina dying every year—I didn’t lose a child, so I didn’t have a right to feel sorry for myself. The death of a person I cared for was not why I went into malaria research, but all these deaths together …” Bilgo says in a recent interview from Burkina Faso, trailing off.

Today, along with overseeing tests in the MosquitoSphere, he hosts local visitors as part of the plan to familiarize the engineered fungus to a population assumed to have deep doubts about genetically modified organisms.

But when the townsfolk see the hated insects falling dead at their feet, their skepticism about St. Leger’s fungus seem to drop as well.

“People are asking me, ‘Let me take this to my house,’” he says. “I have to tell them not yet, but I hope soon.” TERP

When his Olympic dreams on the bike came crashing down, Ryan Collins ’16, MBA ’20 struggled to even hold the handlebars. Now he’s racking up records as an elite ultracyclist.

BY ANNIE KRAKOWER

S. CORDLE

yan Collins ’16, MBA ’20 was on his way home from a training ride, the gritty kind that made him feel like he could conquer the world. After spending the past couple of years racing up the ranks from a junior mid-Atlantic cycling champion to one of the top riders in the nation, he’d just received his dream phone call: an invitation to try out for the Olympic training team representing the U.S. in Tokyo. His bags were packed, and he was scheduled to fly out to the camp the next morning.

Collins could take his usual training route through his pretty Annapolis neighborhood, past families walking their dogs and boats gliding on the bay, or he could speed straight ahead down a shortcut to the salmon dinner—his favorite—he knew his mom had waiting for him. On that July evening in 2017, he decided to shave five minutes off his ride and started pedaling that way.

The next thing he knew, he and his bike were crumpled on the ground as onlookers’ screams pierced the air. In a flash, an approaching car had collided with him head-on.

Paramedics rushed Collins to Anne Arundel Medical Center, where doctors who recognized the elite athlete in their care reluctantly delivered the news: Not only was he not flying out in the morning to the Olympic training camp, but the odds were that he’d never ride a bike again.

“And I’m thinking, ‘Well, just watch me,’” Collins says.

When Collins was a resident assistant in Hagerstown Hall, he set up a stationary bike at the top of a stairwell so he could safely train during wintry weather or before the sun came up. It wasn’t uncommon for Terps to find him pedaling in place on the landing.

“People would come up and ask me, ‘What are you doing?’” says Collins. Some students even offered him mid-ride water or snacks.

Just a few years earlier, he might’ve been the one giving funny looks. He didn’t enter the cycling scene until he was a high schooler, and even then, he started out with indoor biking to condition for his primary sports of soccer and tennis.

He came to relish the camaraderie in the fitness group that he joined, and in 2009, members convinced him to try his first race, a 30-minute event called a criterium on a road circuit in Tysons Corner, Va. He didn’t come close to winning, but watching the more experienced cyclists got the wheels turning in his head.

“Wow, I want to be like them,” Collins recalls thinking. “I want to be stronger, faster, smarter, more tactical.”

He studied that race and entered many others through the Mid-Atlantic Bicycle Racing Association to hone his newfound craft—criteriums, shorter time trials and 10to 20-mile road races. By the time he came to College Park, he’d risen to the top of the junior category.

A major factor in that success was his interest in nutrition. While many teachers

are hard-pressed to get teens to read a textbook, Collins pored over scientific journals for fun, then acted as his own test subject, experimenting with how certain foods fueled his rides.

That passion blossomed at UMD, where between weekends of cramming people and bikes into cars for races with the Terps’ cycling team, he formed his own major through the Individual Studies Program. Called nutritional physiology, it combined health, biology, nutrition, kinesiology and business. He studied abroad in Spain and analyzed the Mediterranean diet, the focus of his capstone project.

“It’s always easier to just go with what is set up. But he was very adventurous, curious,” says Justicia Opoku-Edusei, senior lecturer of biology and Collins’ faculty mentor. “He needed more. That’s the type of person he is. He always wants to explore, push the envelope.”

In the aftermath of the accident, no matter how hard Collins tried to lift his arms, they stopped when extended horizontally in front of him, and he likened himself to a zombie or Frankenstein. In a more gruesome tie-in to Mary Shelley’s monster, the screws and

bolts holding him together protruded under the skin on his lean frame. The tiny bumps all over his chest are still visible today.

After his hospital stay, he was couchbound at home, unable to accomplish the simplest everyday tasks: dressing, showering, even using the bathroom. His parents had to hold him at the waist so he could stand and try shuffling around. He couldn’t hold a knife, so they precut his food or overcooked his veggies into a scoopable mush. Collins couldn’t even find comfort in his bed, needing to sleep upright in the living room so he wouldn’t get stuck, unable to turn over.

“If he laid on his back” says his mom, Kim Collins, “he was like a turtle.”

He chose a consistent ache over pain medication-induced loopiness, bringing on sleepless nights. It was still summer, he often thought in those hours, the ideal time to hop on the bike and explore with friends. Instead, he could only watch their adventures unfold on social media.

During months of near-despair, more painful questions lingered: How would the world see him now? Would he be able to pick up bags of groceries, or, one day, a kid? Was he now just like a chipped mug on the store shelf that no one wanted to buy or fix or use?

Small victories along the way helped quell those worries. Collins practiced slowly walking from the TV in one room to retrieve his laptop in another, challenging himself by keeping items far apart to encourage him to move more. He turned arm exercises into a game by setting up a jigsaw puzzle; he had to constantly reach for pieces. He was able to keep working remotely for an addiction treatment center, typing with just one hand. And he relearned to dress himself, even if his belt remained unbuckled and his shirt untucked.

But then he’d wake up some mornings and notice the race numbers, trophies and medals

surrounding him, and spiral back into an identity crisis.

“Everything up to that point was cycling,” Collins says. “All of my friends were connected to cycling. All of my goals were connected to cycling. … It wasn’t something that I could avoid.”

So he decided that he wouldn’t. After a few physical therapy appointments at Anne Arundel Medical Center, he brought his Tarmac SL5 bike there. With the same tenacity he had brought to the racecourse, he began tailoring each session to the goal of getting back in the saddle.

“There’s … people who do not like to be uncomfortable. He can really suffer.”

—CHRIS RICHARDSON, CO-FOUNDER, RICHARDSON BIKE FIT

can be monotony on two wheels. Unlike the high-speed bursts needed for shorter criteriums, or the blend of endurance and acceleration needed for a traditional road race, ultracycling keeps athletes pedaling for at least 200 km or six hours. On a banked, oval bike track called a velodrome, which averages a couple hundred meters in length, that means close to a thousand laps, with slight left turns every few seconds.

Even on a longer road course—with, say, a 50-mile loop, like the route for the 2025 national championship in Springfield, Ohio— cyclists are still subjected to a physically unnatural position for hours on end: head low, elbows tucked in, back as flat as it’ll go.

In the weeks after the accident, Collins needed to figure out how to reach the handlebars again. That’s how his months of rehab progressed: Could he raise his arm high enough to rest on the bike? How long could he keep it there? Could he grip the bars? How hard? What about gradually sitting upright on the seat, slowly pedaling for one minute, more?

The motions, once second nature, felt frustratingly awkward in his rebuilt body. He was like a gym rat who stopped working out for years, then dived into the deadlift again.

“My hands didn’t have the flexibility,” Collins says. “I didn’t have the strength. I didn’t have the connection to move as quickly as I did before.”

His physical therapists helped him adapt: Fatigue while turning the handlebars? Try “landmine resistance” exercises, pushing a barbell anchored to the ground at one end. Pulling the bike up to bunny-hop over bumps in the road causes pain? Focus on weightlifting to build arm strength. Every goal was personalized, cycling-specific.

As Collins improved, he craved the competitiveness of head-to-head racing—while simultaneously fearing that overdoing it would negate his painstaking work. Doctors warned him against the high-intensity events he was used to, but straight endurance, they said, was acceptable. He started looking into

longer ultracycling races and signed up for his first one, with virtually no expectations.

“I just thought, I’m going to go and just ride my bike for as long as I can. And if I get in any discomfort, whatever it may be, I’m just going to stop,” Collins says. “No sweat, no pressure. Just have fun and remember why I loved riding a bike.”

In February 2018, seven months after the accident, he came in second in the 12-hour race in Sebring, Florida., against top riders, covering 241.5 miles—just eight behind the leader.

He knew he could do more than just ride again. Maybe he could win.

Nervous to return to the open road for conditioning, he stuck to an indoor setup for the better part of a year (though it was a little nicer than his Hagerstown arrangement): a training bike in a makeshift home studio, with a box fan pointed at it and an old blue

desk propped up beside it, its shelf loaded with energy bars and gels. Even today, if it’s dark or rainy, he opts for hours-long sweat sessions there before logging on for his fulltime job as a senior associate brand manager at Haleon, the company behind products like Sensodyne toothpaste and Centrum vitamins.

He’s been disciplined with his nutrition, too, with a diet of mostly plants, very little red meat and no soda or chocolate. (The exception: post-race cookie dough, whether scoops from a Pillsbury tub, homemade bricks from a neighbor or Tollhouse logs gnawed burrito-style.)

It’s all translated into almost unfathomable post-injury success: Collins won 12-hour national championships in 2019, 2021 and 2022, as well as consecutive world titles for the same duration from 2021-23. In 2020, when COVID-19 shut down racing, he still set world records for the most distance covered in six hours outdoors, fastest 100 kms

“He needed more. That’s the type of person he is. He always wants to explore, push the envelope.”

—JUSTICIA OPOKU-EDUSEI, SENIOR LECTURER OF BIOLOGY

As Ryan Collins has shifted gears to ultracycling following his nearly career-ending injuries, he’s pedaled his way to several titles, including national and European championships this year.

and 200 kms outdoors, and fastest time to cross Maryland from north to south.

“He has a natural ability—that’s for sure. But Ryan marries that with an approach that is meticulous and with a mindset that’s attuned to growth,” says longtime friend and fellow cyclist Michael Thaxton. “I see his ability to come back from (the accident) as a testament to his character.”

Cycling sponsors came swarming: The Feed athlete nutrition, Ketone-IQ energy drinks, Rule 28 cycling apparel, Factor bikes, Inovalon health care analytics. Their products line the rooms in Collins’ house, with the companies happy to have an elite athlete promoting their brands—especially one with such a unique story.

“There’s people that can really suffer, and people who do not like to be uncomfortable,” says Chris Richardson, co-founder of sponsor Richardson Bike Fit, who’s been partnering with Collins since the accident. “He really can suffer.”

A month before his most recent outdoor world record attempt in September last year, Collins’ ambitions almost got derailed again.

Backed by financial support from sponsors and inspired by friends’ encouragement during rehab to get back to the velodrome, he’d decided to chase down the global outdoor and indoor marks—his “personal Olympics” after missing Tokyo. Then the Valley Preferred Cycling Center in Breinigsville, Pa., where he had been training and planning to invite Guinness World Records representatives, unexpectedly closed for repairs.

He scrambled to arrange the attempt at the San Diego Velodrome instead, but he was less familiar with that track’s quirks. On top of that, strong winds during training kept blowing him off course, to the point where he couldn’t practice a full six-hour ride ahead of the event.

When he saw his family cheering after his nearly 800 laps on the big day, though, he

knew he’d done it.

His 161.08 miles not only set a new global high, but his 100-mile, 100-km and 200-km times along the way were also records. In November, he rode that success into the Borrego Springs, Calif., desert, battling fierce sandstorms to notch another world championship and provide a boost of confidence for his indoor record attempts a month later. With 170.7 miles covered in those six hours, and similar 100-mile, 100-km and 200-km times shattered, he closed out 2024 with eight new world records and a sense of redemption.

As he’s embraced the ultra side of cycling and his life has shifted gears, Collins’ goals on the bike have shifted, too—away from the shorter Olympic events he once strived for. Already in 2025, he won national and European championships. He might summon Guinness again for another record attempt later this year, and he’s preparing for next year’s Race Across America from California to New Jersey.

But after cycling was almost permanently taken away from him, Collins doesn’t want it to be all of him. It’s why he went back to UMD for his MBA while he was still working his way back to full strength, why his family’s house is filled with as many Sensodyne toothpaste tubes as Ketone energy drink bottles.

“When cycling becomes my job,” he says, “I’m afraid that I would lose the love that I have for it.”

That passion is fascinating others, with his story, in a sense, coming a full velodrome loop.

As Collins attempted those indoor records, his father noticed a group of blackclad bikers assemble in the arena’s upper seating area. It was the Mexican Olympic cycling team, in the U.S. for training, now watching in awe as this skinny, sweaty force of nature blazed for hours around the track.

“Here are these Olympians, which he aspired to be,” Roy Collins says, “and they’re looking at him and aspiring to be who he is.” TERP

FOR NEARLY 25 SEASONS, THE CLARICE HAS CELEBRATED THEATER, MUSIC AND DANCE. TERP TAKES A PHOTOGRAPHIC TOUR OF THE LANDMARK CENTER’S FIRST ACT.

BY SALA LEVIN

SCOT REESE CRANED HIS NECK up at the soaring atrium of the new Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center for the first time in 2001 and knew immediately that a moment of dramatic transformation was unfolding at the University of Maryland.

A professor of performance who’d joined the faculty in 1995, Reese was used to the outdated lighting grids, paint-splattered walls and creaking floorboards in the old Tawes Fine Arts Building. Here, though, Reese became emotional as he took in the scale of this sprawling new venue, with its six performance halls, library, classrooms, offices, rehearsal spaces and café. He marveled at the natural light pouring through glass walls and the blend of modern design and functionality.

“There was a sense of validation—like all the late nights, the scrappy shows, the rehearsals in too-small rooms had led to this,” says Reese, now a professor emeritus. “I felt proud, not just for myself, but for everyone in the arts community at Maryland. We were finally being seen.”

The 318,000-square-foot building was the largest ever constructed by the state—and remains the largest performing arts center in Maryland. Critical to its creation was a $15 million gift from artist Clarice Smith and her husband, Robert Smith ’50; the state, Prince George’s County and other private donors provided additional support.

Center namesake Clarice Smith (left) was known for her portraits, still lifes, florals, landscapes and equestrian scenes. Smith showed her work at galleries in the U.S. and abroad. The Ina and Jack Kay Theatre (opposite page) is a classic, Broadway-style venue that seats 626 guests and is used for a variety of performances from opera and jazz to theater and comedy.

The Clarice, as it’s colloquially known, will celebrate its 25th season this academic year, having altered the trajectory of theater, dance and music at the University of Maryland. With its state-of-the-art technical capabilities, collaborations with international artists, and educational offerings and outreach, the center has become a crown jewel of the university.

“The building is a spectacular cultural resource, but what’s really special is that it’s the home of so many talented, passionate and committed staff, faculty, students and acclaimed artists who innovate and create and bring programs alive for UMD and the surrounding community,” says Terrence Dwyer, executive director of The Clarice.

The center, part of the College of Arts and Humanities, has hosted artistic luminaries like Harry Belafonte, Rita Moreno, Dionne Warwick and John Lithgow, along with state, national and world leaders for lectures and conversations, including the Dalai Lama and Al Gore. It has hosted groundbreaking musical collaborations, innovative interpretations of classical operas, global debuts of thought-provoking plays, an annual gathering of the nation’s most talented young instrumentalists and even an international puppetry festival.

UMD’s School of Music, the School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies and the Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library all have a home in The

Clarice, giving both students and local residents the chance to develop and sharpen their artistic skills—whether through UMD classes, student-community ensembles or opportunities like the Terrapin Community Music School, which offers area middle and high school students affordable music lessons.