Recently, in an attempt to gain temporary relief from the overwhelmingly bureaucratic world of architecture, I listened to a political podcast. A now-retired politician was asked to compare his time in City Hall as Lord Mayor with his time in Stormont as an MLA. He began, “What a dump Stormont is… it’s up on a bloody hill, nobody can get to it, there’s not a restaurant near it, there’s not a cafe near it; it’s divorced from the people”. In contrast he referred to City Hall as “a palace of the people”.

As an architect, I was intrigued. For here, our messy politics was being considered not through a lens of bias, manifestos or agendas, but through urbanism. This was a politician talking; free from the whimsy of architectural notion. The assessment had no forced symbolism or complicated language, just honesty through experience.

He’s right, Stormont is on a hill and no, you can’t get to it. It is up such a huge hill that east Belfast running clubs use it for their most brutal training sessions. It’s not near a café, nor a pub. In contrast, City Hall is the centre of town. It hosts the Christmas markets, demonstrations, protests and al fresco lunches. It belongs to the people.

So, what to do about Stormont? Can it be more like City Hall? If it is to remain as a legislative assembly within our current political landscape or as part of a ‘New Ireland’, it simply must undergo renovation.

Architectural intervention in parliament buildings isn’t new. My old boss, Norman Foster, did this very successfully with the Reichstag building in Berlin. Once the epicentre of the Nazi regime, the building is now the physical manifestation of democracy itself.

A glass dome was added directly above the debating chamber, allowing light to pour into the space below where

politicians fight their respective corners, adding a sense of openness to proceedings. The dome isn’t just a skylight; a spiralling ramp sweeps around its inside face creating a publicly accessible viewing gallery, affording the people great views of their city as well as the ability to look down on their elected representatives. The politicians below are all too aware of the people circling above them; a constant reminder of who they truly work for.

I am not suggesting a cut and paste response, Belfast is unique and deserves a unique solution. If Stormont is to continue to house a government of sorts, then its physical space needs brought into line with the values that any democracy should uphold: openness, fairness, accountability, and responsibility. But who could and who should do this? Someone with an indepth understanding of this place? Perhaps someone with a blissful ignorance? Maybe I’ll give Norman a bell.

If you would like to submit a comment for Perspective, please contact: a.vauls@ulstertatler.com

Richard Kennedy ARB RIBA Architect

The Ulster University Architecture Student Symposium is a three-day annual event established in 2018 by the Belfast School of Architecture and the Built Environment. This article explores the inspiration and purpose behind the symposium, complemented by a student’s personal reflection on the experience.

The initiative emerged from a number of overlapping ambitions held by the school. The first was to take the architectural research questions being formulated and explored by our BA Year 3 and MArch Level 1 and Level 2 students in their respective Design Theory and Communication, Ideas Lab and Dissertation modules, and open these up to cross-course presentation, discussion and interrogation. This enables students in different years – and at different levels of their architectural education – to learn from one another. A second ambition was to place these presentations, discussions and interrogations in a public setting within the city of Belfast, allowing the public to listen to the various research topics and themes and engage in questions and dialogue. The third ambition was select venues that helped to draw attention to the powerful role that architecture can play in catalysing urban activity and revitalisation. This has seen the Symposium take in place in a variety of landmark buildings in Belfast, such as the Raidió Fáilte Building in west Belfast, the Indian Community Centre at Carlisle Methodist Memorial Church in north Belfast, and most recently at 2 Royal Avenue in Belfast city centre. The Symposium affirms the commitment of Ulster University to grounding education at the intersection of situational learning, civic engagement and critical research.

David Coyles

Architecture Programme Director

The Ulster University Architecture Student Symposium plays an important role in connecting architectural education and discourse to the civic life of the city. By hosting the 2025 event in 2 Royal Avenue, this enabled student research to move beyond the university studio and into the urban realm, facilitating city users, practitioners and researchers to engage with themes emerging from the school. The result is a shared space where academic inquiry enters wider public conversation, encouraging students to see their work as something that operates within, and responds to, the lived conditions of Belfast.

As an MArch student, I have had the privilege to attend multiple symposiums. I see this as an opportunity for students to showcase their work in a safe environment based on positive inquiry and constructive critique. This provides a platform for information sharing across the school between years and a unique learning environment for further academic investigation. It challenges us to articulate why our work matters beyond the confines of architectural education and

to translate complex theoretical concepts into language that can be understood and questioned by the public.

I was fortunate to present my MArch dissertation ‘The Hollow City’, focusing on Belfast’s ‘Markets’ area, an inner-city residential community shaped by deindustrialisation, conflict and ongoing redevelopment pressures. Using critical theory to examine power and control in the built environment, my project investigates how planning and regeneration processes can prioritise commercial interests over longstanding communities. It traces patterns of containment through security-led planning, disinvestment through surrounding redevelopment, and marginalisation through the persistent privileging of private development. At the same time, it highlights local resistance, particularly the work of the Market Development Association, which challenges these forces and advocates for more equitable urban futures.

Most importantly my research invited the audience to question how cities are shaped, who development serves, and how communities continue to negotiate space, power and belonging within changing urban environments. Sharing this work reinforces how student inquiry can contribute to civic debate and can inform future research opportunities.

Adam O’Neill, MArch student

In this issue, we speak to

What was the topic of your university thesis? Why did you choose it and what did you learn from it?

For my final year thesis, I set out to reconnect the historic town of Carlingford with the waters of Carlingford Lough - a link lost after 19th-century land reclamation and the decline of its waterfront. My proposal centred on a new civic square as the town’s focal point, framed by cultural and public spaces, and anchored by the adaptive reuse of Taaffe’s Castle. The scheme aimed to restore a sense of place, create a vibrant meeting hub and accommodate the thousands who visit each weekend. The process deepened my understanding of placemaking, heritage integration, and how public realm design can revive a community’s relationship with its setting.

What does the practice of meaningful architecture look like to you?

For me, meaningful architecture is about designing places that genuinely connect with people. It’s less about making a statement and more about creating spaces that feel right, that reflect their surroundings, support everyday life, and hold a sense of belonging. The best buildings, I think, are the ones people grow attached to over time, because they tell a story, spark memories, and quietly become part of the community’s fabric.

What are some of the challenges faced by architects and the wider profession?

A big challenge for architects now is just keeping up with how fast technology is moving - and working out when its use is appropriate. Things like AI, new software and all the digital tools can make life easier, but sometimes they end up creating more work than if we had just used more traditional methods.

If you hadn’t become an architect, what would you be doing?

If I hadn’t pursued architecture, I most likely would have gone down the route of teaching PE or into building surveying. I actually wanted to be a PE teacher first, because I’ve always loved sport and was very inspired by my own PE teacher, however, I was unable to pick it as a GCSE subject, so I had a change in direction. I later became interested in buildings and design, which led me down the built environment route instead. I had a choice between studying building surveying

or architecture at university, but I still think if things had been slightly different, I’d have followed the sports route.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m currently working on a large 700-unit social housing development in Derry/Londonderry, which also includes a community hub and retail centre as part of the wider masterplan. Alongside that, I’m involved in a very different type of project - the design of a new golf club - which has given me a nice contrast in scale and type of client. Having both projects on the go at the same time has been a great mix, allowing me to work on community-focused housing while also developing a leisure project with a completely different brief.

What does the next ten years look like?

Over the next 10 years I want to keep growing as an architect and take on projects I feel passionate about. I’m working towards specialising as a conservation architect and would love to focus more on heritage and conservation work in the future. I also hope to continue building a portfolio that blends social value with good design. Ultimately, wherever my career takes me, I want to keep designing places that genuinely connect with people - places that feel rooted, human and meaningful. The projects I choose in the future won’t just be about size or profile, but about whether they add value to communities and make people feel something. I’d love to look back in ten years and see that the buildings I’ve worked on have become part of people’s everyday lives - spaces that tell stories, spark memories and quietly embed themselves in their surroundings. That’s the kind of architecture that inspires me most, and it’s the kind of work I hope to spend my career doing.

The Early Career Architects Forum seeks to support architects in Northern Ireland in their first ten years of practice, consecutive or otherwise; and aims to provide a platform for the society’s newest members to engage on matters specifically pertaining to the development of early career architects.

Over the next year, through Perspective, the ECAF seeks to promote the individual profiles of Early Career Architects, as well as invite them to contribute to opinion pieces for upcoming editions of the magazine. If you would like to contribute or be featured in future columns please reach out to the chair of the Forum, Alex Knowles.

MacGabhann Architects was founded in 1975 by Antoin MacGabhann Snr, and expanded in 1997 when sons Antoin and Tarla joined the practice. Post-graduation from UCD, Antoin Snr worked with Liam McCormick in his Derry office and the influence of McCormick continues to be evident in the practice’s design philosophy for civic and domestic projects alike.

Frank Lloyd Wright considered the importance of form and function in his book In the Cause of Architecture (1908), and from this discussion he would create his six propositions of ‘organicity’, namely, simplicity and repose should define each project with windows and doors acting as a structural element of the design; a building should extend and grow easily from its site, reflecting the landscape around it; colour should be informed by the fields, trees and surrounding environment; materials should be freely expressed and not hidden; and, buildings should be sincere and true.

These principles came from a development and refinement of Wright’s mentor Louis Sullivan’s dictum ‘form follows function’

to become Wright’s integrated pronouncement that ‘form and function are one’ and should be equally reflected in design. Liam McCormick is widely recognised as Donegal’s most important modernist architect and his work, predominantly in church design, can be seen to follow Wright’s principles, primarily in relation to buildings reflecting their context in form and colour. Notable examples include the Church of St. Aengus, Burt (1967), where the church’s shape was inspired by the nearby bronzeage hill fort of Grianán of Aileach, and St. Michael’s Church at Creeslough (1971) with its contours echoing the surrounding mountains. Equally these design ideologies inform the work of MacGabhann Architects and are visible in two recently completed houses, Cashel and Sámhnas, both located in County Donegal.

Cashel House

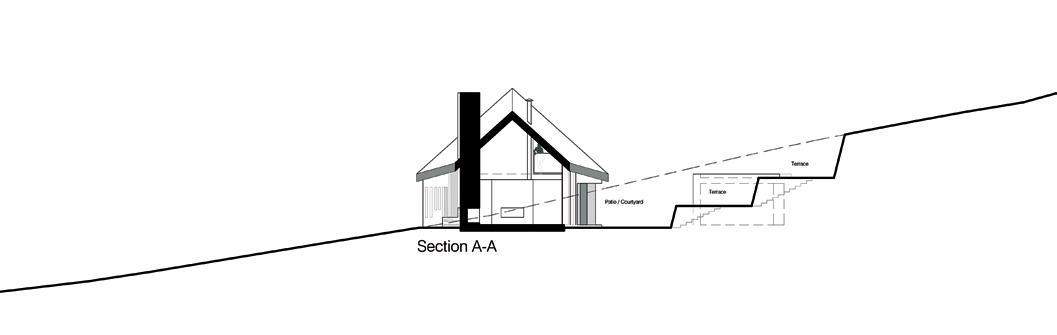

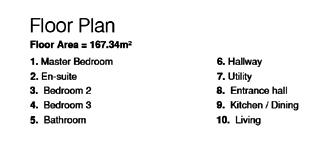

Cashel is a relatively common name for a townland, and it comes from the Irish word ‘caiseal’ meaning fortified settlement or hill fort. This is an accurate descriptor as the house is set on a steep north-facing site, and its elevated location sets it in direct

Client Private

Architect

MacGabhann Architects

Björn Patzwald, Tarla MacGabhann, Antoin MacGabhann

Civils & Structural

Carr Consulting Engineers

M+E

Contractor Designed

Main Contractor

Self Build

Photography

Joe Laverty

Photography

communication with Doe Castle and the Ards Estuary, of which it enjoys a commanding view. Doe Castle is a well-preserved 15th century four-storey tower house and surrounding enclosure situated on a rocky outcrop in Sheephaven Bay. This creates a dramatic vista for Cashel House. Despite its raised position, however, the house does not break the skyline when viewed from Doe Castle.

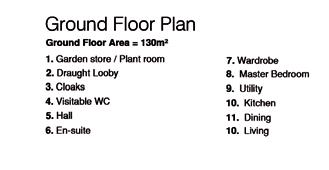

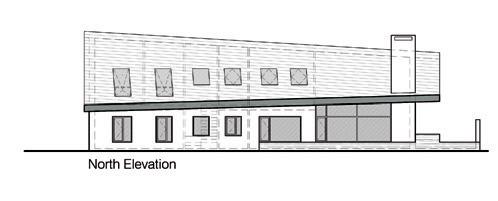

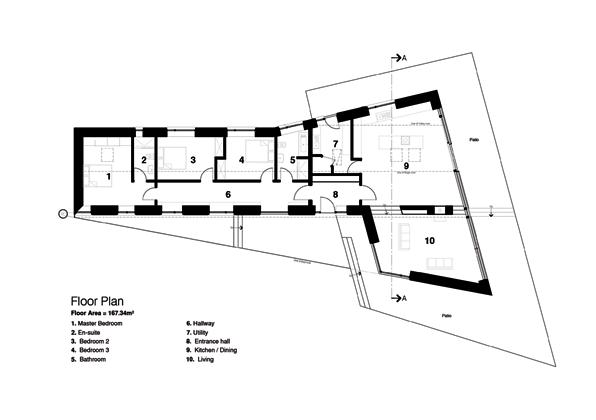

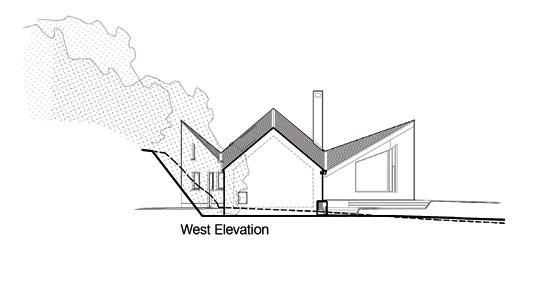

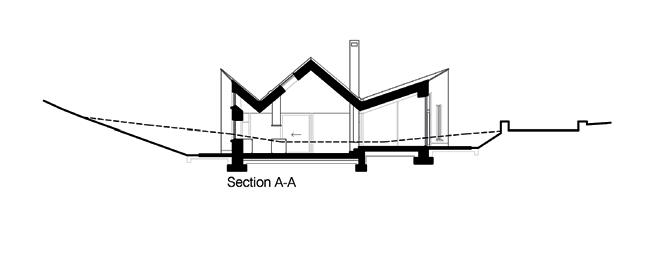

The architects have innovatively conceived the roof design to reduce its perceived scale. It is a two-storey dwelling but, according to the architects, the special geometry of the roof and the shape of the house (which is not a perfect rectangle) creates the illusion of the roof sitting lower; “it looks like a singlestorey dwelling from the road”. It is a clever configuration and it helps tie the house more effectively to vernacular precedent as intended. The chimney is a distinctive feature of the house and its form echoes that of Doe Castle, marking another linking device with the surroundings.

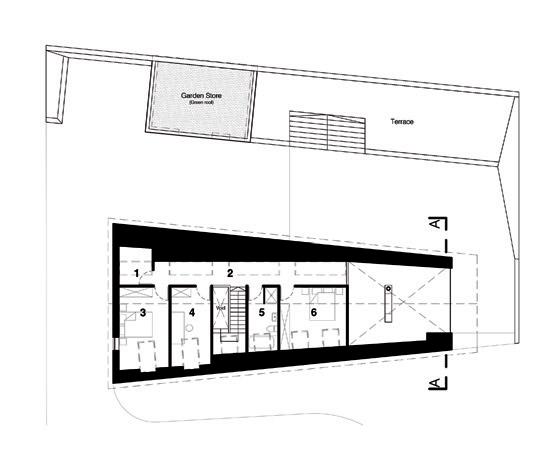

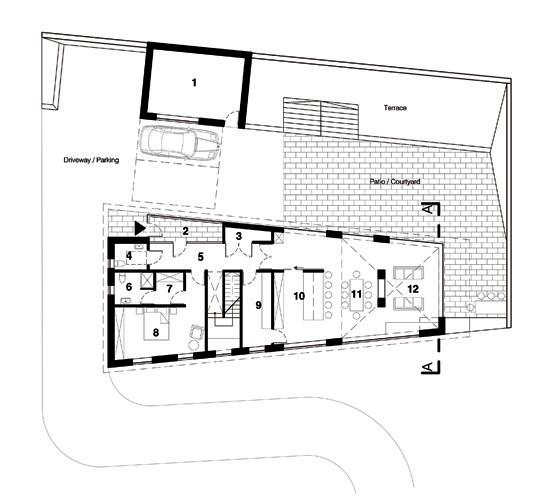

The footprint of the house is shaped as an elongated isosceles trapezoid, or wedge-shape rectangle. This creates

an expanded floor area at the east end of the property, which accommodates the master bedroom, en suite bathroom and additional bathroom on the ground floor, and at first-floor level, a study, bedroom and comms/plant room. At the west end, a double-height living and dining area is located, and this space communicates with an adjacent patio area, accessed via glazed doors. A dialogue is established between internal and external spaces via the continuous levels, glazing on the west elevation and the roof that extends over a portion of the patio space. Within this extended roofscape the timber soffit is exposed; its treatment is a nod to the roof interior of St. Conal’s Church in Glenties (1974) by Liam McCormick. There is further continuity with McCormick in MacGabhann Architects’ use of white wet dash and downpipes conceived as abstracted gargoyles on either corner of the east elevation to bring water down from the roof into two circular receptacles. The closest McCormick referent for this feature is the Church of St. Aengus in Burt with its rainwater spout delivering water to a circular pool at ground level. The symmetry of these spouts and receptacles acts as a grounding device for the house on its site.

Client Private

Architect

MacGabhann Architects

Ronan O’Domhnaill, Tarla MacGabhann, Antoin MacGabhann

Civils & Structural

Carr Consulting Engineers

Sámhnas House

Directly in line with Frank Lloyd Wright’s first principle of creating simplicity and repose, Sámhnas, in Fanad, was named by its clients and this translates as ‘ease, respite’: ‘Shíl mé go mbeadh sámhnas agam’/’I thought I would rest myself’. This naming device references the feeling of contentment and serenity that the clients believe the house design engenders. In this project, the traditional clachan formation is the inspiration and the house enjoys spectacular views out over Lough Swilly and Dunree, with natural southern and western light penetrating the interior. The architects explain that “the design aims to celebrate the cultural and architectural heritage of rural Ireland while incorporating sustainable building principles”.

A distinctive feature of the house is its red roof that connects with the existing vernacular of the adjacent shed and the overall locality. In my opinion, the west elevation of Sámhnas unites aesthetically with McCormick’s Fish Auction Hall, in Killybegs, (1983) through McCormick’s use of red corrugated tin, a series

M+E

Contractor Designed

Main Contractor

Darren Kelly

Photography

Joe Laverty

Photography

of triangles in the roofscape and the scale of the chimney. It is a subtle aspect of continuity and one which may not have occurred to the architects when conceptualising their design. It is an apt connector however, as both structures are situated by the water. For the architects it was important that “the red roof in the landscape was in harmony with the red shed roofs that are visible in rural Donegal… it also has three distinct roof sections, echoing the natural rock formations along the coastline”.

There was an existing cottage on the site and the design of the new build sees its footprint extended and fanned out through adding two wings. This opens the house to the seascape and Malin Head beyond. The form of the house is that of single-roomdeep traditional cottages and the small gable end of the building reflects this scale, ensuring continuity with tradition while also providing privacy. The house essentially has two distinct aspects: that of the south elevation where the vernacular is evidenced but given a contemporary dimension of a sloped soffit of timber painted black. This overhang provides shelter and is partially supported by the living-area wing of the structure. Within, the interior is centred on multi-generational living. The kitchen and dining area adjoins the living area on a higher level and there is a soft demarcation of these spaces through incorporation of a dividing wall with an opening for the stove that shares heat throughout this combined space. Bedrooms are accessed via

a simple monastic-style corridor. Similar to Cashel, rainwater collection is integrated into the design and the red rain spout channels storm water into a circular receptacle and this water is conserved and used domestically.

Both Cashel and Sámhnas overlook the water; their modest scale and sensitive design ensure a quiet and comfortable position within the landscape. They reflect Wright’s principles where the buildings extend naturally from their site reflecting the surrounding context, and where colour is referenced from those tones already visible in the environment. They further acknowledge McCormick’s signature design elements which ensure distinctive landscape features are reflected in the design, as well as integrating plain glass ‘picture windows’ to enable inhabitants to enjoy nature and light-filled homes. They are essentially objects in the landscape but designed to be sincere and in harmony with that context.

Dr. Marianne O’Kane Boal

Metal Technology’s architectural aluminium systems have been utilised in a wide range of sophisticated student accommodation developments throughout the UK, many of which are dominating Belfast’s skyline. Meeting the demand for modern, attractive accommodation that is fit for purpose and for students’ lifestyles, Metal Technology’s specialist products offer total design flexibility for creative aesthetics with the assurance of value engineered, structural, weather and security performance.

Windows | Doors | Curtain Walling | Brise Soleil | Louvres | Passive House

Environmental

Life cycle analysis

Sustainable products

Responsible sourcing

RecycAL low carbon solutions

Support

Technical design input

Thermal modelling

Free air calculations

Security analysis

Online BIM models

Secured By Design

overlooked

Lost in the wasteland on the north end of the core of Northern Ireland’s capital, an overlooked building faces the glazed façade of a 1980s structural expressionist shopping centre; ignored and invisible to the trickle of foot-traffic along the once bustling civic spine of the central city.

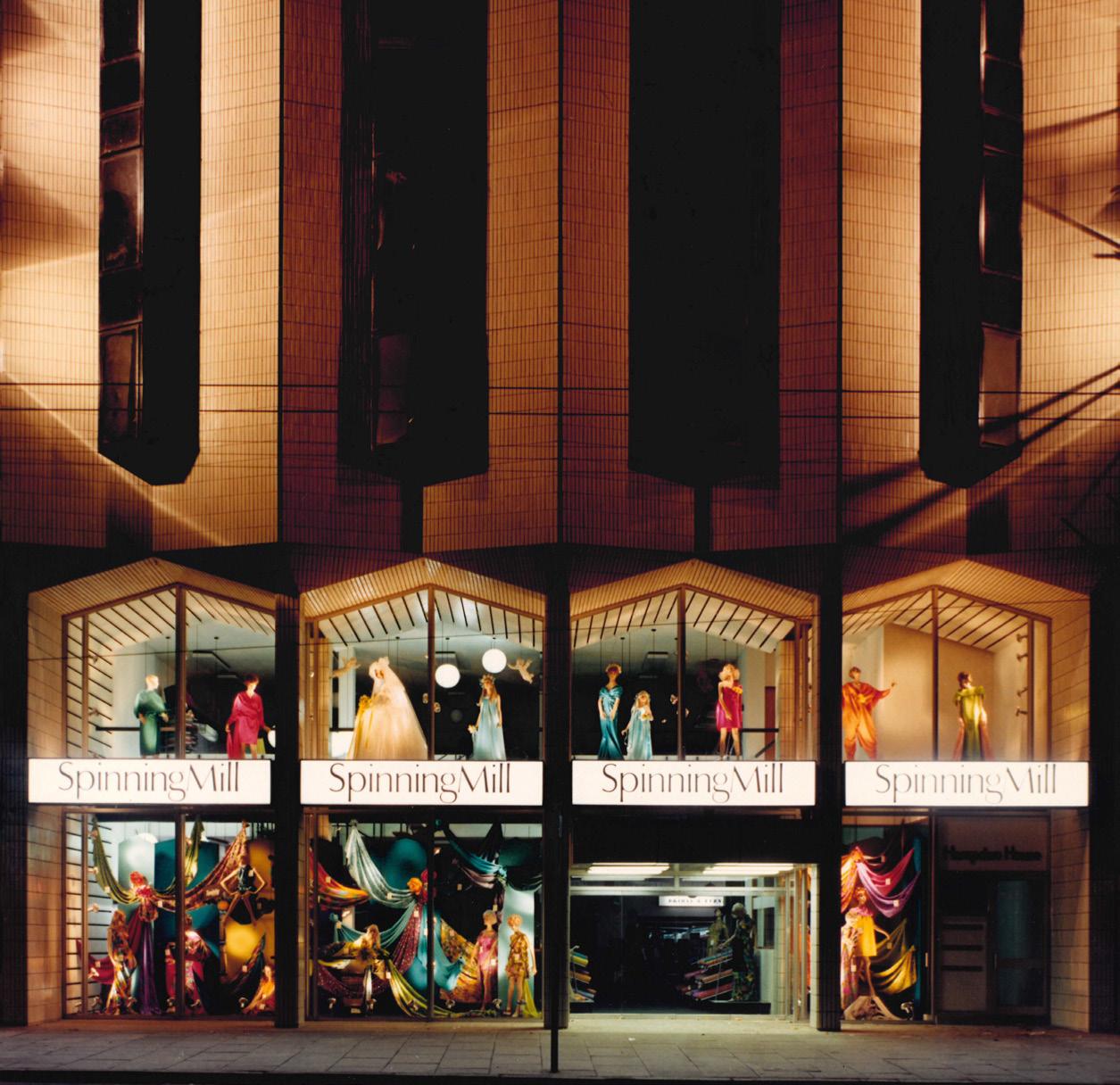

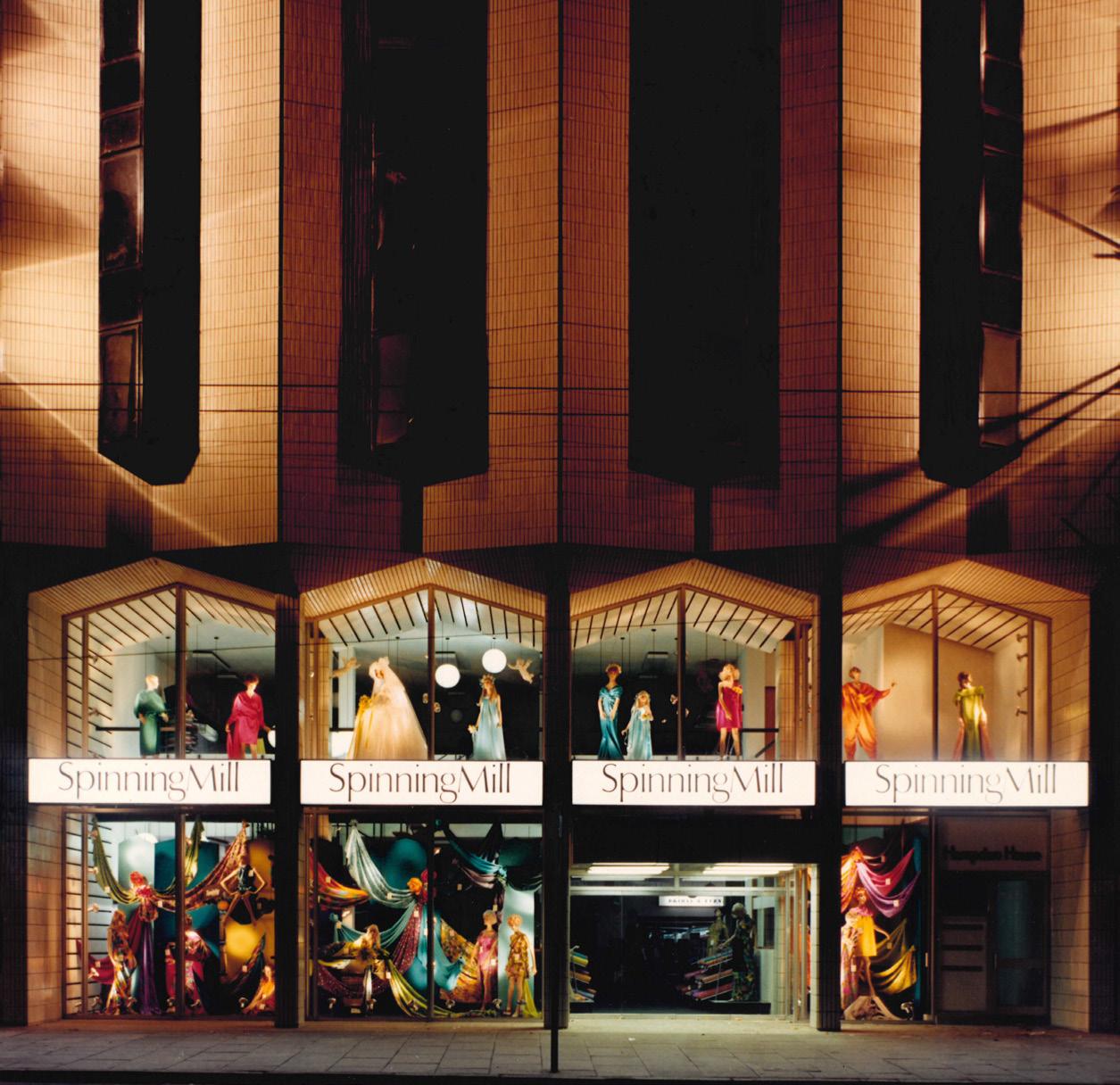

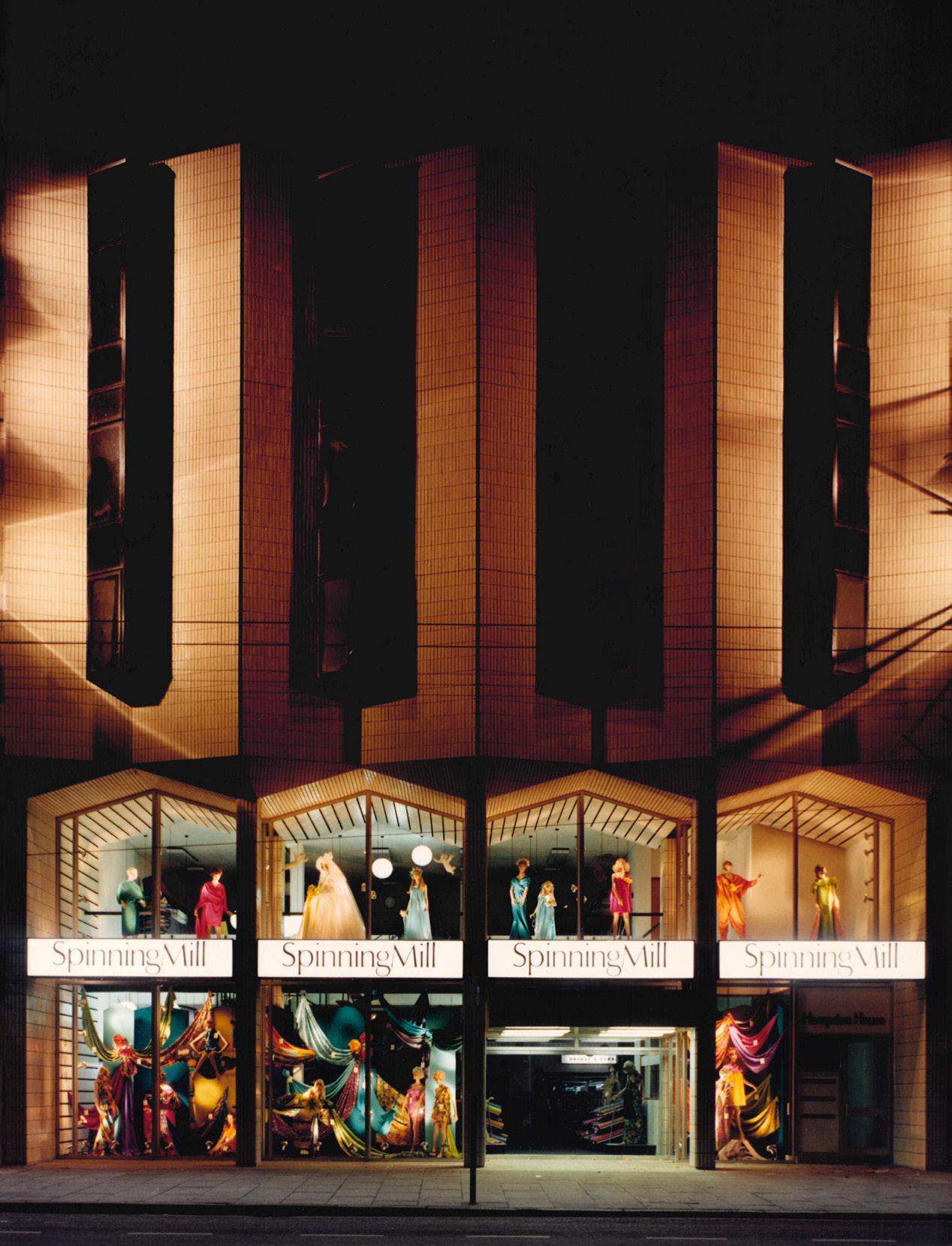

No.55-59 Royal Avenue – originally called Gladstone House and since renamed Hampden House – is best known to Belfast’s populace known (depending on their vintage) as either the Spinning Mill fabric and soft furnishings store, Texas Homecare DIY warehouse, Argos, or as the current home of the Linen Hall Library Charity Bookshop. Like many of its neighbours, the building has been denigrated and compromised over its sixty years, the most recent indignity – presumably an ill-considered attempt to mask decades of neglect – being the application of brightly coloured paint to its previously austere façade. More profound, however, is the existential threat being posed to this city quarter by the Tribeca development: a proposed 140-thousand-squaremetre, mixed-used regeneration scheme focused on the inner-north of the city that obtained planning consent in 2019. Hampden House is looking beleaguered, tired, and arguably (and I very much intend to argue against the words I am about to write) ready for the bulldozer.

Despite this, the building has retained signs of its original design quality, evident for those willing to stop to consider it as a significant piece of architecture. The unusual white tiled ‘zig-zag’ façade, terminating in chevron detailing, over fullheight glazing to the lower two floors; black-framed glazing to the upper floors with geometry matching the complexity of the facade; the carefully considered detailing of the tiles to the complex angles as the façade folds back into the first floor

soffit; elements that hint towards a concealed auspiciousness derived from the era of its inception.

The 1960s was a time for optimism in Northern Ireland. The austerity and dread of the War were two decades in the past, the baby boomer generation – teenagers and young adults at the time – was experiencing an increasingly enriched cultural and social life and, even though the sanguine atmosphere was underscored by political tension, the horrors of the Troubles were yet to be realised. Across the UK, planners and architects were not only rebuilding Britain following Göring’s Blitzkrieg, but also reshaping the country’s cities and suburbs based on international utopian ideals under the broad term of Modernism. Northern Ireland was rather slow on the uptake of this new design style, with ‘neo’ versions of traditional styles being rolled out well into the mid-century. However, there was a cohort of confident and bold young design professionals, buoyed by this new style as the optimism manifested in concrete, steel, glass and – in the case of Hampden House, delicately slim white tiles.

I think to add in that the optimism was a forward thinking design approach, a complete rejection of what had come before…

Two such architects were Derek McIlwaine and Victor Robinson. Both born in the mid-1930s and graduating in the late 1950s, they were perfectly positioned to ride the crest of that wave of optimism. They established their joint architectural practice – the eponymously named ‘Robinson & McIlwaine’ – in 1963; later shortened to ‘Robinson McIlwaine’ and since abbreviated even further to RMI. The practice is perhaps best known for designing Belfast’s Waterfront Hall, a building closely tied to the optimism of the late ‘90s and the

Good Friday Agreement, but in the early Sixties they were cutting their teeth primarily on small commercial projects and private houses executed in the ‘modern’ style.

Their breakthrough into large-scale retail work, that would come to define the practice for the next four decades, came in the form of retail entrepreneur John Goldstone. Not quite as young but every bit as bold, ‘Johnny’ moved to the Province from Manchester in the mid-1930s, establishing a number of retail chains that benefited from that post-war, pre-conflict optimism. One such chain was the Spinning Mill, established in the 1950s and expanding to eleven outlets across Northern Ireland and Scotland at its height.

The headquarters of the Spinning Mill consisted of two conjoined Victorian buildings located on Belfast’s Royal Avenue, conforming to the strict parapet, sill and storeyheight rules dictated by Town Surveyor JC Bretland’s original design concept of 1880. Goldstone envisioned

something braver than what he perceived as the tired and grotty eighteenth century buildings that dominated the area. In conversations with his son and fellow architect Gavin, Victor recalled his initial meeting with Mr Goldstone as a young architect in 1966. “He had his office in the old building, and he said, ‘I’ve had lots of architects and they’ve left me with this building as it is. I really want to open it up.’ I told him the only thing you could do is pull the building down and rebuild, so he said, ‘Thank you Young Robinson, good luck to you.’ That was it… I thought we had missed our chance, but a few weeks later I had a phone call. ‘Young Robinson, I want you to knock this down and build a new building.’ That was our first job in the city centre.”

Goldstone sent his newly appointed architects to London to look at emerging trends in retail architecture. Victor recalled what he observed and how it affected the design. “We saw the best shop fronts on Oxford and Regent’s Street. The first floor was often open up to the public so you had a two

storey frontage; there was nothing like that in Belfast at the time.” Robinson developed this simple concept further. “I wanted to recess the whole shopfront by six feet to give depth to the entrance, pulling people in and bringing out the geometry of the elevation. At first Johnny was unsure as he was losing quite a bit of retail space. I persuaded him, showing him what we had seen in London. He was excited, seeing that it was a totally new retail concept for Belfast.”

The realised building was a stunning departure for the city’s architecture, particularly in the context of Royal Avenue and unique amongst its contemporaries. Divided into four bays, the upper three storeys are folded along the y-axis, zig zagging back and forth along the z axis and creating an undulating elevation with sharply folded edges. This brought a strong vertical emphasis to a streetscape otherwise defined by verticality. Windows modules are situated where the undulations are set back from the street, taking the form of four dark oblongs. The folded plane, clad in white tiles, terminates above the first floor with sharply angled chevrons that cut back forming the soffit of the double-height shopfront recess. The delicate points of the chevrons rest on elegant pilotis, giving the appearance that they are tethering an abstract cloud, stopping it from floating off rather than holding a building up. Despite the stylistic departure for Royal Avenue, the building broadly conforms with the Victorian development rules of the street; the distinct upper and lower floors maintaining the sense of horizontality despite the vertical emphasis. It is a modern building that makes no apologies or compromises while remaining congruent with its older neighbours; respectfulness without deference.

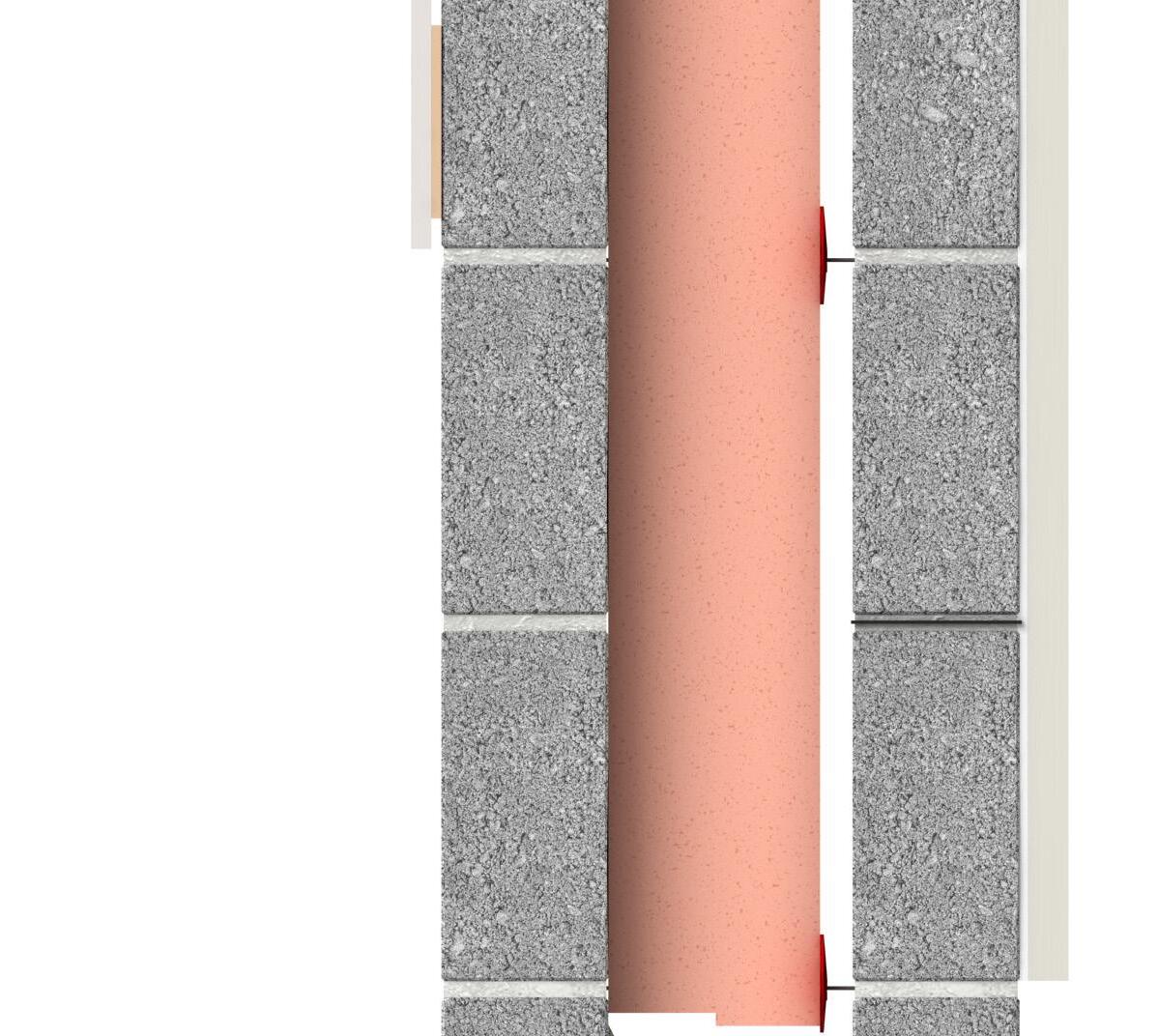

Victor Robinson noted the controversy surrounding the finish: “We used a Belgian vitreous ceramic tile. A façade on a building at University of Warwick by Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall had failed; tiles were dropping off and there was a high-profile legal case. We produced a ten-page specification for the cladding to make sure this wouldn’t happen. Most tiles have a simple key running down the back, but this one had a semi-circular key that drew the mortar in; it really worked tremendously well.”

The building opened in 1968 to such success that, in 1970, the premises were extended to the rear, increasing the floor area by almost 50% and providing a similarly bold doubleheight shopfront to Garfield Street. Using the same material palette, the form here appears more functional and not as conceptually pure as the Royal Avenue elevation. When initially built, the upper floors took the form of a monolithic

white mass floating over the double-height shop front. Although somewhat comparable to the main building, the angular bulk is too heavy to be considered cloud-like. The glazing of the shopfront was cut back sharply at the ground floor, creating an awkward glazing junction. A razorsharp corner cantilevers out over the recessed shopfront, supported by a single square column that somewhat dissipates the sense of flotation.

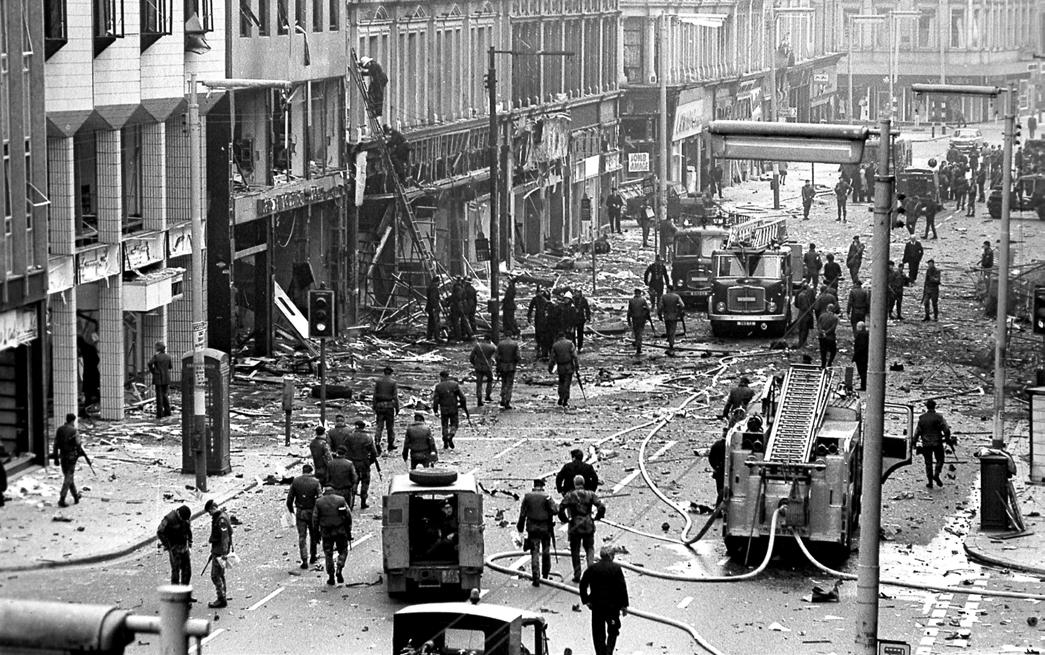

The optimism of the early 1960s came to an abrupt and shocking end in the summer of 1969 with the onset of the contemporary Troubles. The Spinning Mill found itself within the ‘Ring of Steel’, the security cordon around the centre of Belfast erected to protect the retail core from terrorist attacks. This proved ineffective as the store was entirely burnt out by an incendiary device in July 1972. During the ensuing refurbishment works the building was again badly damaged in March 1974 when a car bomb detonated directly outside the building, targeting the army barracks in the Grand Central Hotel opposite. The Spinning Mill never stopped its business during any of these attacks.

Victor shared his observations on visiting the building after the bomb: “I was called down the following morning and the destruction was incredible. All the glass and frames had been blown out but, although little bits of shrapnel pitted the tiles, not one had come off. We had the whole façade tap tested and there wasn’t a single loose tile.” It appears the Warwick University controversy had led to the inadvertent development of a blast-proof facade. The subsequent remodelling lead

to a reconfiguration of the Garfield Street elevation, with the elimination of the awkward cantilevered glazing junction and the introduction of double-height curtain walling to the previously monolithic upper floors. While it was a pity to lose the bold cut back of the glazing, the result was a more comfortable-looking elevation, and no doubt some high quality office accommodation to the upper storeys.

The Spinning Mill closed in 1979 but the building reopened as Texas Homecare, another of Johnny Goldstone’s retail ventures, operating as such until 1987 when Argos took on the lease of the building. Bombed again in July of 1989, this attack targeted the recently opened Castlecourt Shopping Centre that replaced – among a great many other Victorian buildings – the Grand Central Hotel. The subsequent refurbishment unfortunately lead to the loss of the recessed shopfront. The glazing line was brought out in line with pilotis, a shortsighted commercial decision omitting one of the hard-won primary concepts of the building’s design.

Argos moved out of the building in 2010, leading to a period of vacancy that lasted until 2024 when the Linen Hall Library Charity Bookshop moved into the building from its previous premises in Linenhall Street. This apparent new lease of life came after planning approval for the Tribeca development in 2019. The Spinning Mill is one of twenty-one buildings in the area proposed for demolition to make way for the £500 million development.

The building’s distinctive style is not ‘en vogue’, as exemplified by the public reaction to the recent listing of Marlborough House, a 1977 modernist office block located in the New Town of Craigavon. Additionally, there is no doubt that it has been compromised and has lost the exuberance evident in the renders, drawings and historic photos. While I imagine that the suggestion that the building is worthy of saving (or – dare I say it – formal listing) would be met with derision from some, there is no doubt that the building has

unique characteristics that tell us something about ourselves and a key period in Northern Ireland. One just needs to be willing to observe and consider the building and its history, something made much more difficult given the building’s current state.

The optimism of the Sixties – whether it was well-placed, naïve, or a state of denial – created a rich, creative culture out of which some of the defining local architectural practices were wrought including Kennedy Fitzgerald, W.D.R & R.T Taggart (now Taggarts), Ferguson McIlveen, Ian Campbell Architects, P&B Gregory (now Gregory Architects), the James Munce Partnership (now Consarc Design Group) and, of course, Robinson & McIlwaine. These firms and the individuals within them shaped the built environment of Northern Ireland before, during and after the three decades of the contemporary Troubles. Robinson & McIlwaine played a key role in that story with the design of the iconic Waterfront Hall, so closely associated with the 1996 Good Friday Agreement. Considered in this broader context, Hampden House was Robinson & McIlwaine’s first large-scale building in the city centre, opening a year before the onset of the Troubles. These two buildings – Hampden House and the Waterfront – serve as bookends, not only for the individual architectural firm but also for this unfortunate yet defining era for the Province.

This story feels worthy of telling, and the building has the capability of being an equally worthy storyteller.

The author wishes to thank Gavin Robinson for developing the idea for this article and for providing his extensive research on the building to assist in its writing. Gavin’s work in documenting his late father’s early buildings is not only focussed on safeguarding legacy, but is also about preserving the neglected architecture of this era; if not physically then in simply documenting what could be lost imminently. It is hoped that this article plays some small part in this.

Marcus Patton OBE

Marcus Patton was born in Enniskillen and trained as an architect at Queen’s University Belfast. He has been drawing cartoons for sixty years and has designed numerous posters and illustrations. He is a member of the Royal Ulster Academy and was awarded the OBE in 1995.

This book of cartoons takes a satirical look at world events between 2023 and 2025. You can also find a selection of prints by Marcus in The Architecture Shop https://rsua.org.uk/shop/

Clifford Henry

We have a selection of three sketchbooks of prints by the architect and artist Clifford Henry, featuring well known landmarks and street scenes of Royal Hillsborough, Strangford and Holywood.

Desmond NG - East West Fusion, My Food Legacy cookbook

Desmond is a retired chartered architect living in Ireland, originally of Han Chinese descent and born in Malaysia.

When he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, a fellow architect introduced him to the works of Dr Thomas Siegfried, who advocated that cancer patients adopt a ketogenic diet integrated into chemotherapy and radiation treatment. These recipes provide delicious and nourishing meals.

We continue to promote and showcase our members’ creativity. If you have any item that you would like to feature in The Architecture Shop or online shop, please contact kerry@rsua.org.uk.

The Architecture Shop is available at http://www.rsua.org.uk/shop

The Architecture Shop is currently processing and posting orders Monday to Thursday, items are posted Royal Mail, second class delivery.

Mary Arnold-Forster, Director, Mary Arnold-Forster Architects

Roisin McCann and Martin Marshall, Directors, Marshall McCann Architects

The RSUA is hosting its annual conference “Architecture 2026: Home Truths” on 26 March 2026 at Riddel Hall, Queen’s University Belfast.

The architecture of our homes is fundamental to how we live. Do it well, we thrive. Do it poorly, we invite problems.

This conference will delve into the architecture of the home in its many guises – from the rural, to the village, to the town, into suburbia and our city centres.

We are assembling a range of contributors from across the UK and Ireland and beyond to create a day which is thoughtprovoking, challenging, stimulating and inspirational.

The conference will also be a day for conversation, for meeting and hearing from others who share a passion for housing, for design excellence, for enabling lives full of health and happiness.

Who should attend?

• Architects

• Construction professionals

• Housing professionals

• Housing associations

Oliver Schulze, Founding Partner, Schulze+Grassov

• Policy makers

• Politicians

• Local Councils

• Community sector

• Business community

Sarah Featherstone, coDirector, Featherstone Young and co-Founder, VeloCity

• Government departments and agencies

• Project funders

• Developers

• Planning consultants

• Students

• Oliver Schulze, Founding Partner, Schulze+Grassov

• Mary Arnold-Forster, Director, Mary Arnold-Forster Architects

• Roisin McCann and Martin Marshall, Directors, Marshall McCann Architects

• Claire Bennie, Founder, Municipal

• Sarah Featherstone, co-Director, Featherstone Young and co-Founder, VeloCity

More speakers to be announced!

For full conference details and to book a place, visit www.rsua.org.uk

Delighted to consult on the design and supply of a highly efficient kitchen for Down High School

Ashgrove Contract Furniture Ltd is Ireland’s leading specialist joinery, creating handcrafted and bespoke commercial fitted furniture.

Established in 2000, Ashgrove works throughout the UK and Ireland. Our dedicated team of highly skilled craftsmen, draughtsmen, designers and joiners can deliver custom made solutions to suit any project, delivering quality, from design stages through to on-the-floor installation.

Ashgrove has built a strong client and contractor portfolio across public and private sectors including education, healthcare, leisure, hospitality, retail and office sectors. Our solid reputation is built on regular repeat business and the delivery of high-quality, custom products within project budgets and timescales.

Ashgrove was delighted to partner with Graham to deliver classroom and fitted furniture throughout the new state-of-the-art Down High School.

46-48 Doury Road, Ballymena, Northern Ireland, BT43 6JB Tel: 02825 651144. info@ashgroveltd.com www.ashgroveltd.com

McAdam are delighted to have been the lead consultant for the design and delivery of the new Down High School. Our service included Project Management, Architectural, Civil & Structural and Health & Safety

Client Down High School and EA

Architect McAdam Design

Structural Engineer/Project

Manager McAdam Design

QS/M+E/BREEAM JCP

Landscaping

McIlwaine Landscaping

Main Contractor

Graham Construction

Photography

Gareth Andrews Photography

We have a rich heritage of groundbreaking and critically acclaimed schools in Northern Ireland, dating back to the Art Deco Belfast primary schools of RS Wilshere in the 1930s, and extending through the likes of Shanks Leighton Kennedy FitzGerald’s Victoria College of the early 1970s to KFA’s wonderful SEN schools of the 1980s and 90s.

In 1992 the Department of Education introduced the Building School Handbooks, with the very laudable ambition of looking to establish equity in building provision across the primary and secondary school estate in the province. Unfortunately, their very prescriptive design guidance, which has seen only limited

revision over the past thirty plus years, has to a large extent stymmied design innovation.

However, that is not to say that in the hands of skilled architects, with an in-depth understanding of the guidance and the associated budgetary challenges, that new schools of quality cannot still be produced.

McAdam Design has been at the forefront of education architecture in the province over the past number of decades and has successfully delivered a portfolio of well regarded school projects.

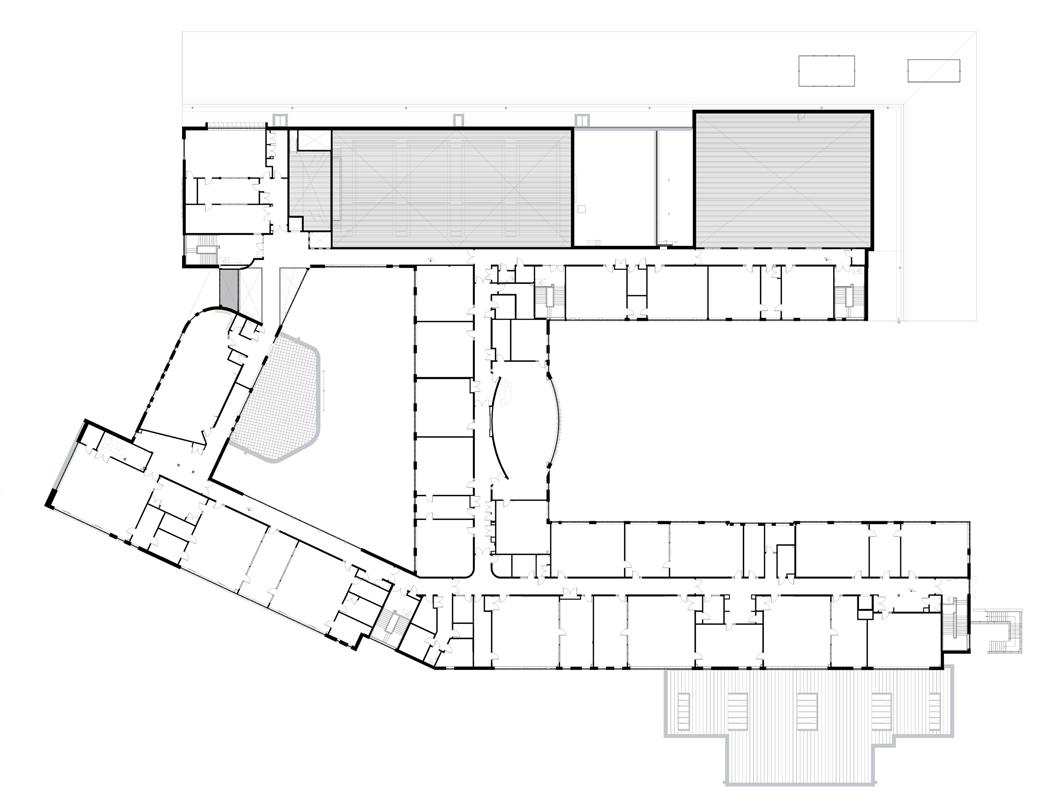

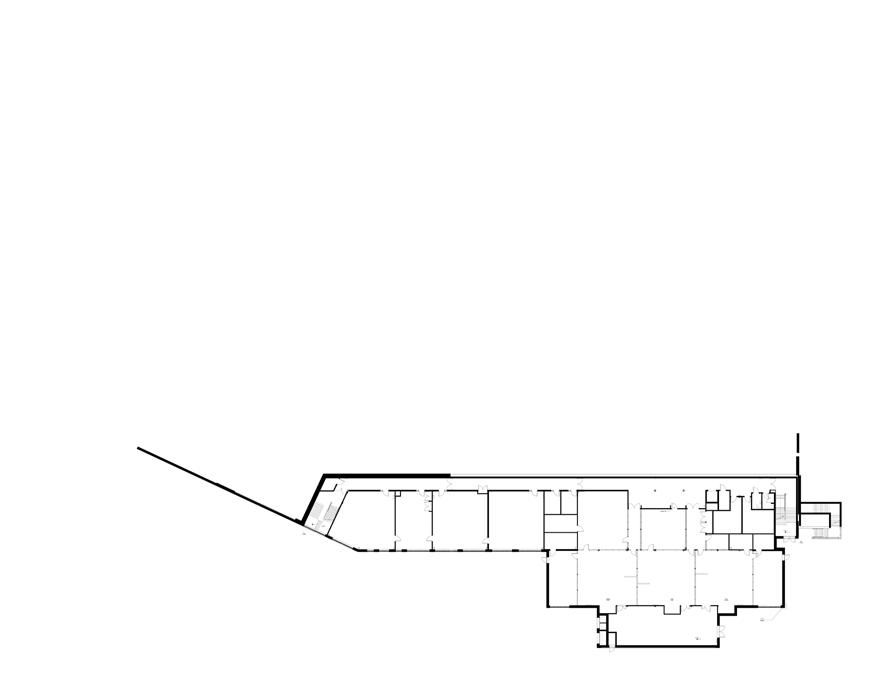

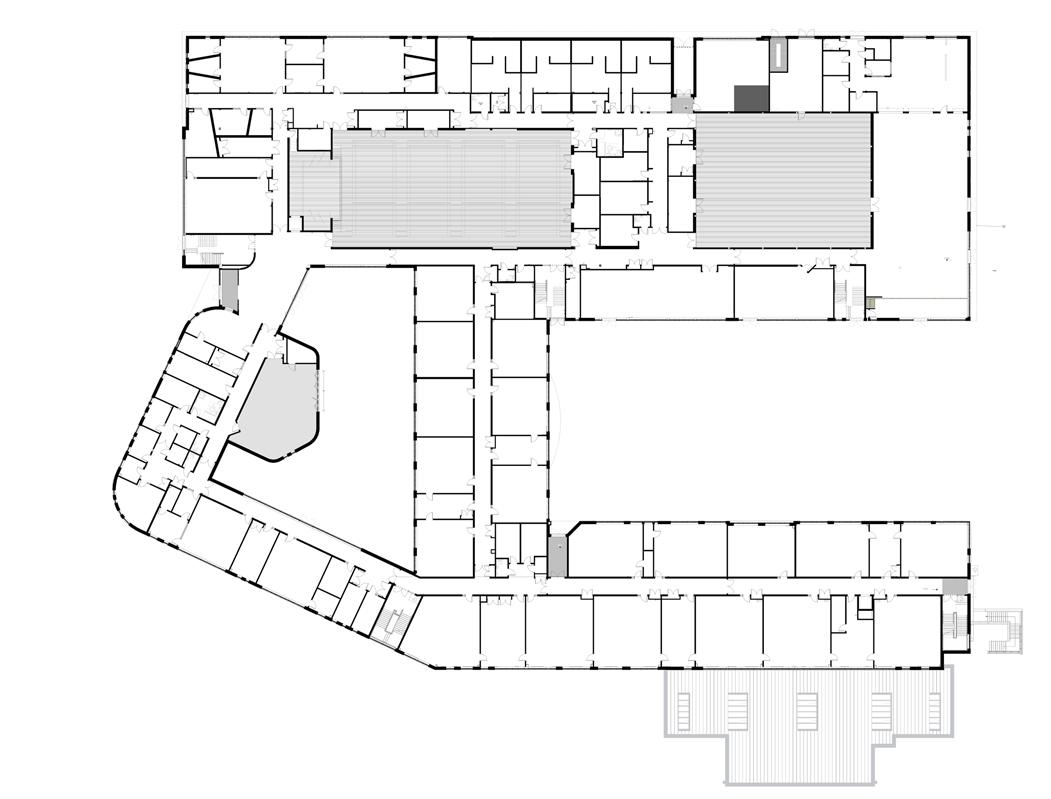

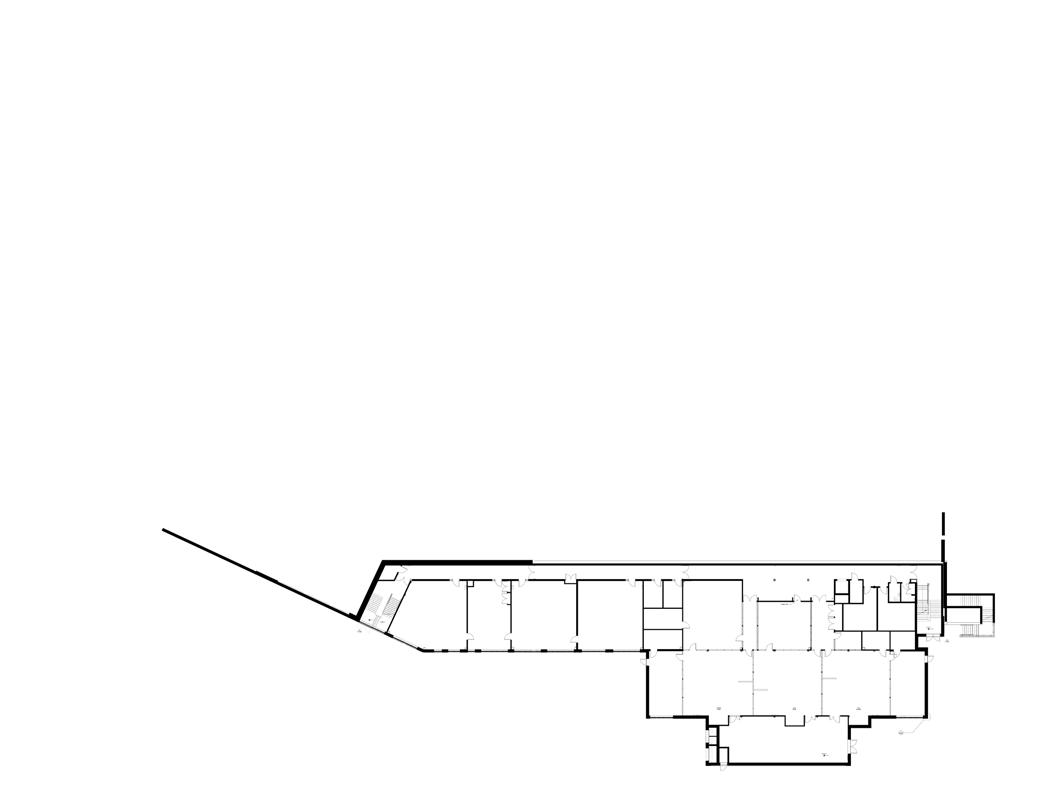

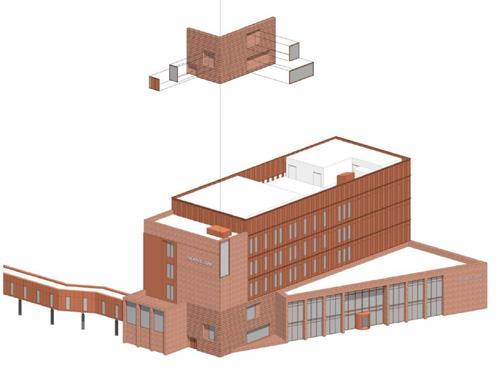

Down High School is one of its most recently completed schemes (June 2025), although its original design dates back over ten years, with capital funding only becoming available some time later to allow construction to proceed in early 2023.

The school itself was established in 1933 and has moved from its original home in the town to a stunning new rural location on its northern outskirts.

The integration of such a large building (with its surrounding playing fields/car parking) into a rolling drumlin landscape will have presented some very difficult challenges. They have evidentially been overcome through the co-ordinated input of the architects, civil engineers, and landscape architects, carefully setting the building into the site, banking surrounding lands and reducing the extent of retaining walls.

The low-slung building form incorporates a long-curved approach wing, with two linking elements connecting it to a shorter rear wing (containing the school’s shared/large volume spaces). Flat roofs both help reduce visual impact and allow

for the incorporation of sedum in selected areas, as part of the environmental strategy that allowed the school to secure a BREEAM Excellent rating.

The consciously restrained palette of external materials responds appropriately to the setting, combining a stone-faced base, anchoring the building into its surroundings, with white rendered walls above predominating and blackened timber sheeting used to identify particular elements (including the projecting art classrooms at second floor).

The school is arranged over three levels, with a small lower ground-floor section set into the sloping site, where the Technology and Design suite, (which has very particular layout requirements) has been neatly integrated, with quieter systems rooms set internally below classrooms and only the noisier manufacturing rooms projecting as a single-storey element.

The accommodation above is organised around two courtyards – a small, intimate, internalised space, accessed off the main entrance (which the school is still considering how best to use)

and a large, south-facing, open courtyard, which the dining area opens out onto and where the school has cleverly installed covered external seating/tables to encourage greater use.

McAdam’s maturity in working with the Handbook and their ability to assist the school in “adapting” scheduled accommodation to suit its particular needs is evident throughout:

• The entrance hall, whilst modest in floor area, is bright and open, with generous glazed screens providing views into the courtyard and a double-height volume (animated by a bridge link) combining to provide an appropriate sense of arrival.

• The designated “Dance Studio” has been strategically placed adjacent to the entrance hall, allowing it to become a multifunctional space, already used for examinations, meetings and presentations.

• Scheduled resource bases/storage areas for specialist classrooms have been fitted out with desks and computers, allowing them to function as small sixth form classrooms.

• The library only retains fiction books, freeing up the remaining area for other independent study and learning.

• Laboratory furniture in science classrooms is movable, allowing it to be reconfigured to suit differing teaching patterns.

The Handbook sets very strict guidelines overall around area limits for schools, based on pupil numbers. This typically necessitates classrooms to be arranged either side of a linking central corridor.

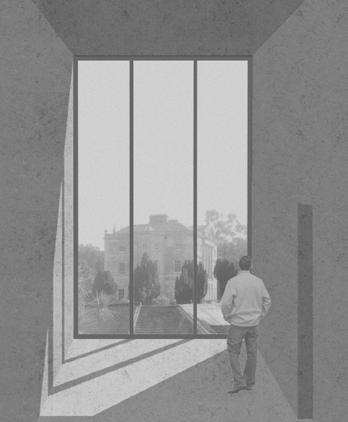

At Down High School space planning efficiencies elsewhere have allowed McAdam to push corridor widths beyond guidance, and whilst generally internalised, they have been able to provide some visual relief to circulation routes through incorporating large glazed screens within staircases, allowing views over the surrounding landscape (the attractiveness of these spaces evident in the use of one for a piano recital at a recent open day).

The large-volume multi-purpose hall and gymnasium are linked by a suspended acoustic screen to allow independent or combined use and, with the PE hall, are arranged in a linear pattern, with accommodation set around to reduce their apparent bulk and allow views into these spaces from corridors at upper levels.

There is a general calmness to the interior, with a restrained palette of “heritage” colours incorporated, heavily influenced by the school’s principal, Mrs Maud Perry.

This impression is wonderfully accentuated by the playing of classical music within the highly specified toilets and its use to announce the end of periods rather than the traditional bell (features seemingly borrowed by Maud following a recent visit to schools in China).

The school is delighted with its new home; it is a very successful design solution, responding extremely well to its landscaped setting and the needs of its staff and pupils.

However, it is also perhaps further demonstration, supported by many educationalists, that the Department needs to undertake a thorough overhaul of their Handbooks, allowing them to respond in a more flexible manner to emerging pedagogies and the individual needs/ethos of a school … which in turn would remove the “straight jacket” that is restraining architectural ambition.

Peter Minnis

Project Data

Gross internal area (GIA): m2 12,253 m²

Predicted regulated energy use: 110.01 kWh/m2/year

Predicted on-site renewables output: 2.53 kWh/m2

In-use Operational energy use: 77.63 kWh/m2/year

In-use potable water: Litres/person/day 20 litres

WJ Hogg & Co Ltd have supplied and installed a louvre wall, plus a louvre plant screen together with its Big Foot steel support structure as part of the exceptional renovation of Down High School.

This plant screen solution is quick and easy to install and avoids the need to penetrate the roof membrane with support steel.

The louvre systems at Down HS were designed to provide

visual screening, however Hoggs can provide louvres for any type of application including ventilation, Class A rain defence, penthouse louvre turrets, and motorised louvre/damper units for natural ventilation.

Tel: 028 9077 8700

Email: louvres@wjhogg.co.uk

AFS Passive Systems delivers certified passive fire protection solutions across commercial, residential and public sector projects. We work collaboratively with architects to safeguard both compliance and architectural intent. Third-party certified | FIRAS accredited | Comprehensive QA documentation.

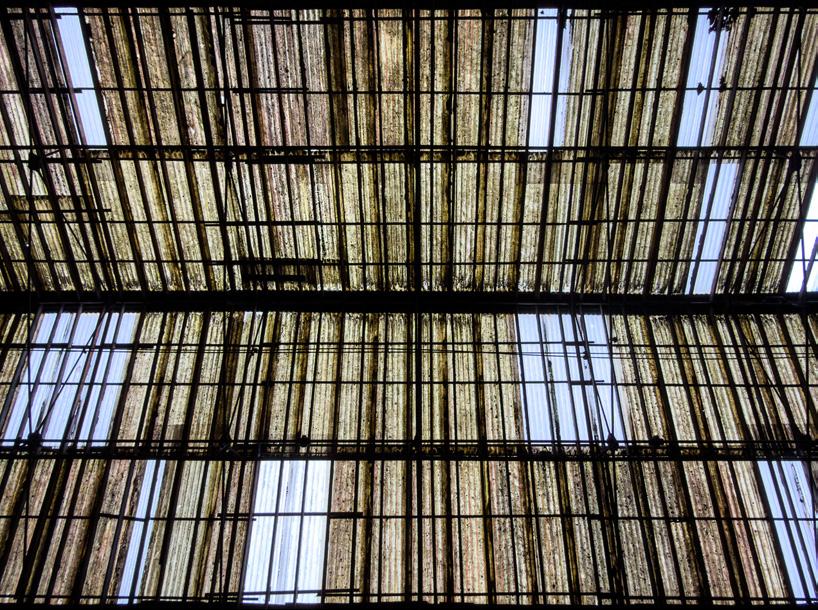

It is difficult to imagine a venue more appropriate, nor indeed one with more raw beauty, than Riddel’s Warehouse, in which to present this exhibition celebrating architectural conservation across the UK and the artful and imaginative reuse of old buildings.

The fabric of this 19th-century ironmongery warehouse exudes architectural and engineering quality and heft. The patina, the palette and the very perfume of the place ooze history.

The form and articulation of the interior with its tall open volume embraced by layered balconies exhibits a uniquely theatrical air, Belfast’s own “Globe Theatre”.

But its current condition demands urgent attention and demands substantial expenditure.

This special venue renders palpable those values in our man-made heritage which we must protect and nurture. In a more modern or a more neutral venue, the imperative for conservation might have seemed an abstract notion.

Not so here.

Riddel’s is a doubly fitting location since its planned conservation by Hearth (Historic Buildings Trust) has attracted the benign and generous interest of the charitable organisation whose history is the subject of this exhibition, the Architectural Heritage Fund.

The exhibition celebrates the work of this remarkable charity which has, since 1976, by means of grants, loans and expertise, been supporting passionate local groups in the conservation of their built heritage. Specifically they have encouraged communities in nurturing imaginative reuse of loved but now redundant buildings.

They have aided almost two-and-a-half thousand projects in their 50 years (to the tune of approximately £180 million).

For this exhibition they have selected 50 representative projects (mostly completed) to illustrate the diversity in building type, in new use and the breadth of location of the schemes which they have assisted and encouraged.

There are medieval churches and a lighthouse, mills, factories and warehouses, pubs and swimming pools, department stores and theatres across the entire United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland is well represented. Riddel’s Warehouse, of course, is illustrated and the aspiration of Hearth that this stunning, unique building can be fully used for the people of Belfast and beyond is articulately expressed.

The much loved and highly successful courthouse in Bangor is displayed here as a completed and popular project. The redundant court building has become a busy musical, theatrical and community venue and a gallery space.

Other NI projects in the exhibition include the Tearooms at Murphy’s on Main Street in Ederney, Co. Fermanagh. This scheme creates multi-purpose community and office space, revitalising the heart of the village.

An 18th-century country house near Cookstown was conserved and reopened by the Lissan House Trust with assistance from the Architectural Heritage Fund. It now welcomes thousands of locals and visitors to experience one of the country’s most significant historic houses.

The handsome Georgian Hamilton Terrace in Belfast was reclaimed from little more than the crumbling shells of houses when Hearth Historic Buildings Trust intervened with the aid of AHF to retain and comprehensively restore an exemplary piece of our urban fabric.

The narrative which accompanies many of the projects and which underpins the aspirations of “the Fund” emphasises the significance of people and place in valuing the historic buildings. A strong community demand for the retained and restored buildings is a central measure in assessing the potential success of the schemes. Local commitment to fix and to new use is essential.

Aidan McGrath

The exhibition is open to the public from 05 February to 19 February 2026

Part one: My recent four-day visit

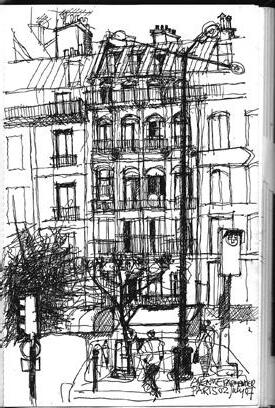

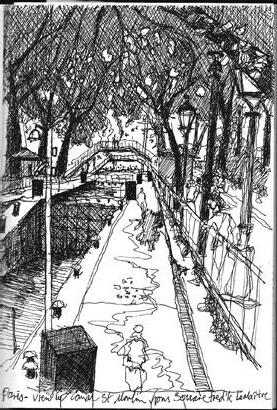

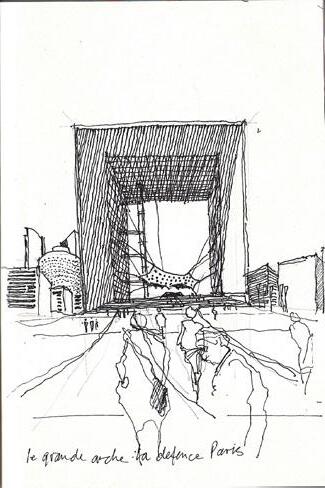

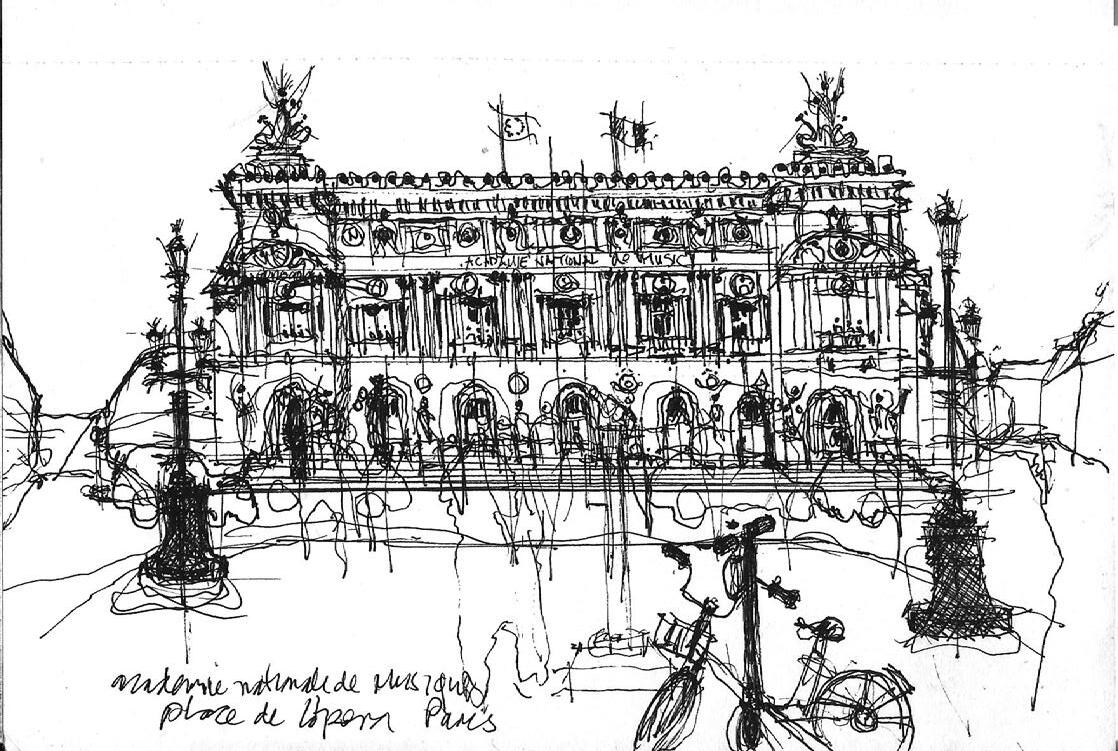

It is quite a few years since my last visit to “gay Paree” – so beautiful and elegant - no wonder it is the most visited in the world. I am fortunate to have old friends with a gorgeous apartment located between Place de la République and Canal Saint-Martin who let me stay there for a few days - how lucky am I? I flew from Dublin after staying in the United Arts Club, a bohemian retreat off Baggot Street - at €60 per night, so cheap for Dublin. I took the opportunity to see exhibitions in the RHA (its annual open exhibition), the National Gallery (female retrospective of Marnie Jellett & Evie Hone, wonderful) and the Douglas Hyde Gallery1 In Trinity College, powerful work by Mohammed Sami: images of trauma with oblique references to loss or conflict – he was for a brief period in our own UU art college (and undoubtedly was influenced greatly by our own Paddy McCann). See sketch no 01

Arriving in Paris (ha!) Beauvais airport and, after a long transfer, late evening arrival at my destination, I immediately get the Parisian vibes and tingle. I quickly got out on the street and absorbed the unique Parisian atmosphere; why did it take me so long to return to this magical city? I found an inexpensive café opposite my accommodation - La Barrique - and after being well fed and watered (and wined!), made a quick sketch of my temporary residence opposite before retiring to bed. See sketch no 02

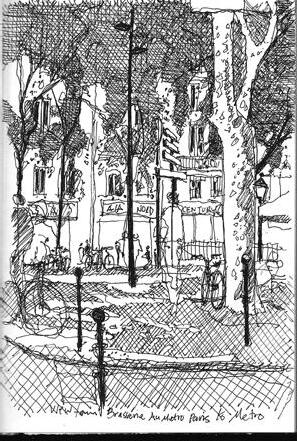

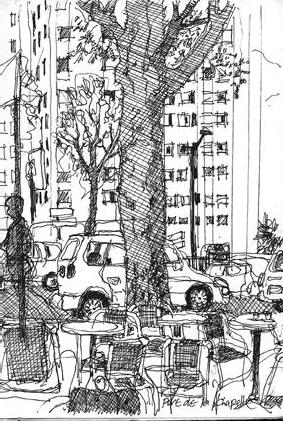

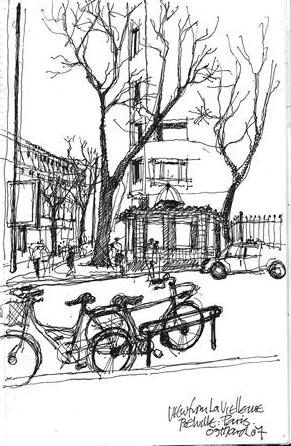

Next morning I had breakfast at my favourite café, Au Métro, a short walk from Place Jacques Bonsergent, and ordered a petit déjeuner of espresso, tartine (baguette with butter) and orange juice (for €9), and took in the surrounding street scene. I decided to draw it and remarked to myself the value of street trees to urban life - but more of this later. See sketch no 03

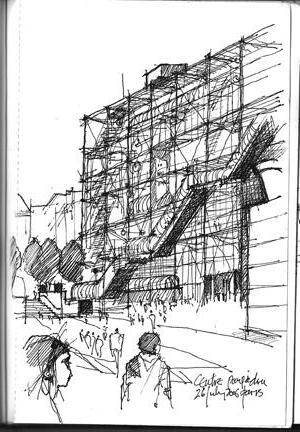

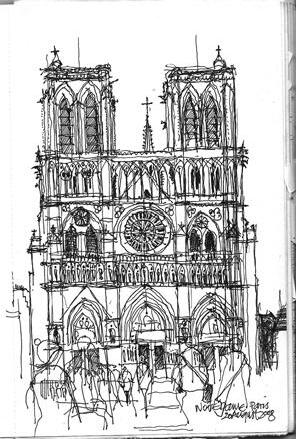

I decided to take the metro and briefly revisit Musée d’Orsay, located in the former railway station interior (magically transformed in 1980 by the Italian architect Gae Aulenti) to view post/impressionist art, especially by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the huge dynamic images of the follies on raw canvas - extraordinary - with Oscar Wilde depicted. We were entertained to a Folies Bergère cabaret performance – on a temporary stage – of dance and music in period costume. But onwards to my main destination, Centre Pompidou, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s 1977 glass-andsteel masterpiece. I saw the “hole”, a huge excavation created by artist Gordon Matta Clarke, pre its construction on my first of many visits, in 1973, on my way to work in Vancouver (an unpublishable story!). I wanted to see the building again before its 5-year closure in September for refurbishment. It is by far my favourite public art space and plaza. Its ‘Meccano-like’ structure and box-form strangely sits comfortably in its historic context. Sadly, most of the

exhibition spaces were already cleared (including the permanent collection) but a display of works by the pioneering female artist Susanne Valadon (long overlooked, also the mother of better known artist Maurice Utrillo) was delightful. I was too late to draw the building this time but include one executed on a previous visit (one of many such sketches in this article). See sketch no 04

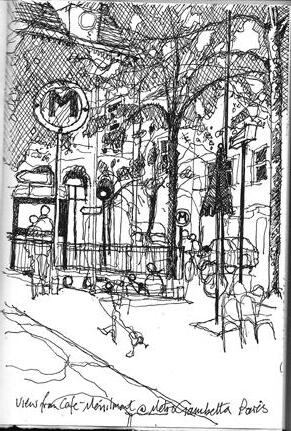

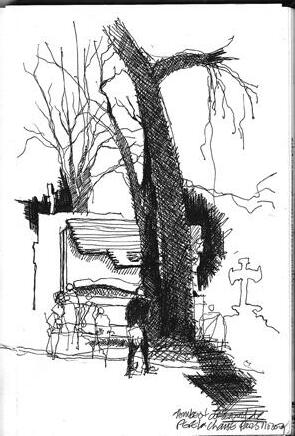

A return to Paris would not be complete without a visit to Cimetière du Père-Lachaise and to the tombstone of Oscar Wilde – not to be missed. I travelled to Place Gambetta and stopped for a coffee, enjoying the view of the tree’d intersection before making my pilgrimage to the cemetery.

Since my last visit, a glass screen has been erected to stop damage by enthusiastic visitors inscribing messages or leaving items, including lipstick kisses, on the stonework. I admit, I was once one of those individuals leaving my mark - which one? I leave you to guess!

See sketches nos 05 & 06

I continued my travels to re-explore the historic markets at Porte de Clignancourt (an exit to the Boulevard Périphérique ring road), a huge sprawling ramshackle collection of stalls selling all sorts of bric-a-brac. I stopped for an Arabic coffee – so tasteful – and took in the surrounding streetscape before exploring the wares on sale. See Sketch no 07

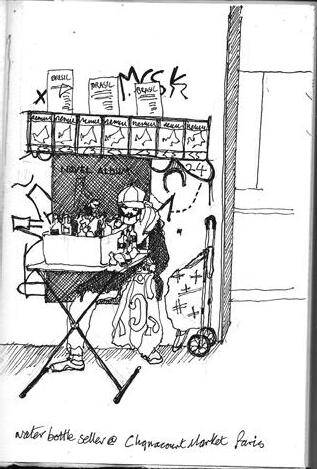

There I was moved to see so many impoverished (?) immigrants, especially those standing alone trying to sell me perfume, watches or illicit cigarettes. One woman, seated, selling water bottles for €1 caught my eye; a picture of the contrast between the rich and poor in Paris - I will return to this observation later. See sketch no 08

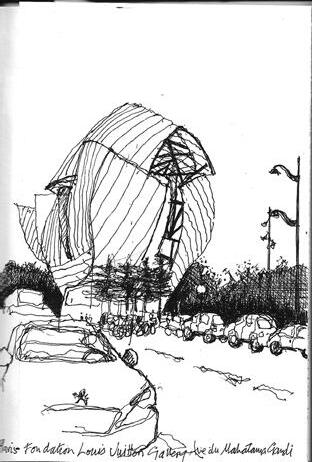

The following morning I took the metro to Les Sablons on Avenue Charles de Gaulle – much improved with new pedestrian/ cycle streetscape – and made my way to see the much lauded Fondation Louis Vuitton, a contemporary art gallery designed by Frank Gehry, located in Jardin d’Acclimatation next to Bois de Boulogne park. A huge, very expensive glass, steel and timbered ‘sail’ structure with ‘concrete cubes’ underneath, housing the art gallery’s fine art collection. The extensive David Hockney retrospective exhibition on show was impressive, especially his early American/Californian works. Only a family as rich as LVHM group could afford to construct such a building and curate such an exhibition. See sketch no 09

absorbing the Parisienne atmosphere, but not the pollution; there is now less traffic and more cycle lanes and pedestrian priority was more visible than on previous visits (again more on this later).

See sketches no 10 & 11

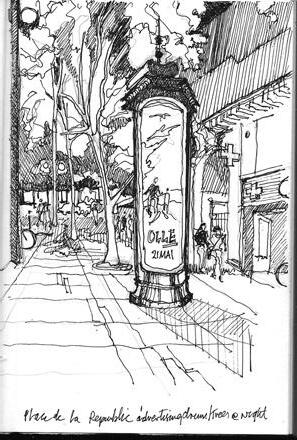

I headed to Place de la République to a vast eatery, the newly opened Bouillon République. It is an enormous café/restaurant serving very cheap food to 500 patrons daily. For the 2nd evening, I queued outside with dozens (maybe 100+), but as a single person managed after 10 minutes to jump the queue (legally!) to be seated in its vast, very elegant interior. Prices were ridiculously cheap for Paris (starter, main course, dessert, ½ litre of wine and café €25!!), great value and delicious, I can’t eat better/cheaper in Belfast! I lingered a while to sketch the street scene on the wide boulevard with its treescape of mature plane trees with a traditional cast iron advertising ‘drum’ (and Metro vent).

See sketch no 12

Afterwards I strolled down to Canal Saint-Martin, crowded with mostly young people enjoying the canal-side evening ambiance, chatting and relaxing.

I made my way to Chez Prune, one of my favourite haunts, to have a nightcap – it was packed outside but a woman beckoned me to join her and her family. She was an Argentinian/Slovakian lawyer married to an Irish expat educated in Paris - what a combination! We had a wonderful conversation over shared ice-cold beers. I hope to return to see them again.

See sketch no 13

I finished my French journey in La Rochelle, travelling by a luxurious, fast SNCF train journey, arriving at the station to be picked up by my friend Gildas to relax for a few days before travelling home.

Paris is a beautiful city to visit, with so many world-famous sites to see. Just strolling along the boulevards or the banks of the River

Part Two: Comment on city issues raised/noted

One - I can’t help but wonder about iconic buildings such as Fondation Louis Vuitton (a vanity structure by owner/CEO Bernard Arnault), their cost, value and relevance to cities other than as a tourist attraction – and the €1 billion cost of it (and wealth of the owner) compared to the life of the €1 water bottle seller in the same city; incomes under the living wage threshold; visible homelessness and destitution - are our values misplaced?

Two - The city is awash with large street trees – their value to the urban environment is invaluable: they provide shade, shelter, a habitat for wildlife, capture carbon, pollution and deliver oxygen – as well as improving our mental health and wellbeing – and planting them is a no-brainer. Belfast, take note.

Three - Paris has aggressively banned/severely restricted vehicular traffic in favour of pedestrians and expanded cycle lanes (started for the 2024 Olympics). The results are visible, with rewards of less pollution and public safety notable – we need to follow in their footsteps, (Bel)fast!

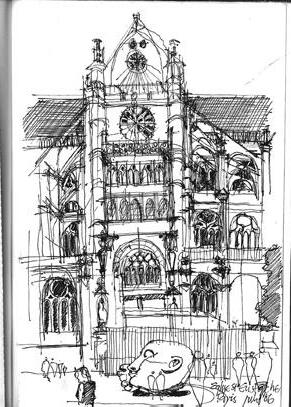

Part Three - sketches compiled from previous city visits

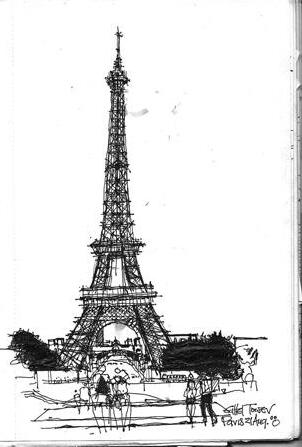

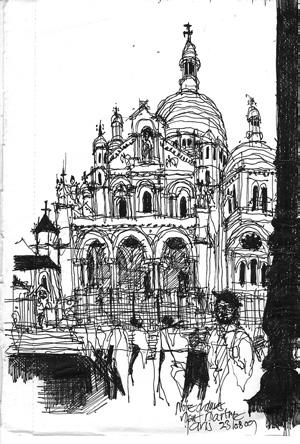

It will be apparent to the reader that it would have been impossible for me to have created all these sketches during one short city visit (I sketch quickly but not that fast!!). So I have selected some of the more recognisable images sketched during my many previous visits to the city. Some more notable sites shown are: Sacré Coeur, Notre-Dame (before the fire), the Opera House and Gustav Eiffel’s Tower. Rather than producing another article, I include them here - I hope you don’t mind and forgive me.

Peter Hutchinson

1 Designed by Paul Koralek of ABK Architects, in 1978, a magical brutalist concrete space-with delightful steel/concrete detailing 2 Paddy McCann/Pádraig Mac Cana is one of NI’s best living contemporary artists –his influence on this artist’s work is clearly visible

The Institute for Research Excellence in Advanced Clinical Healthcare (iREACH) on the Lisburn Road in Belfast by Todd Architects is a groundbreaking project set to transform medical research in Belfast. This 8,500m² state-of-theart facility, funded through the Belfast Region City Deal initiative, will provide specialised spaces for clinical trials, research and associated enterprise activities.

Designed to foster collaboration and innovation in medical research, iREACH comprises two strategically located buildings on either side of Lisburn Road, adjacent to Belfast City Hospital and Queen’s University Belfast Medical Biology campus.

Each building is expressed as a single lightweight aluminium volume supported by a sculptural brick podium and expressed

gable. This design creates a holistic response to the dual-site arrangement, establishing a clear formal relationship where the separate buildings visually “interlock” despite being separated by a major thoroughfare. Textured brick coursing and aluminium fins add detail and articulation, responding to both the Lisburn Road streetscape and the larger contemporary buildings of the adjacent City Hospital site.

Building A integrates with Belfast City Hospital via a bridge link, housing essential research spaces and clinical areas.

Building B, replacing the former Radius Housing tower, focuses on innovation with shared amenities, offices, incubator spaces and advanced laboratories.

The project aims for BREEAM Excellent certification, emphasising sustainability and cutting-edge research capabilities.

Construction is set to begin in Autumn 2024, with completion expected by Autumn/Winter 2026, marking a significant advancement in Belfast’s medical research infrastructure.

Client Private

Architect Des Ewing Architects

Civils and Structural Manhire Associates

M+E Advance M&E

Interior Designers Garuda Design

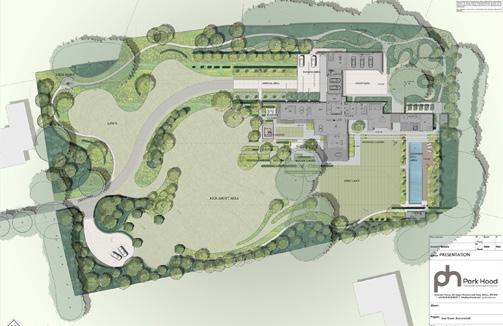

Landscape Architects Park Hood

Quantity Surveyor Rainey Best

Main Contractor

Roskyle Construction

Photography Elyse Kennedy

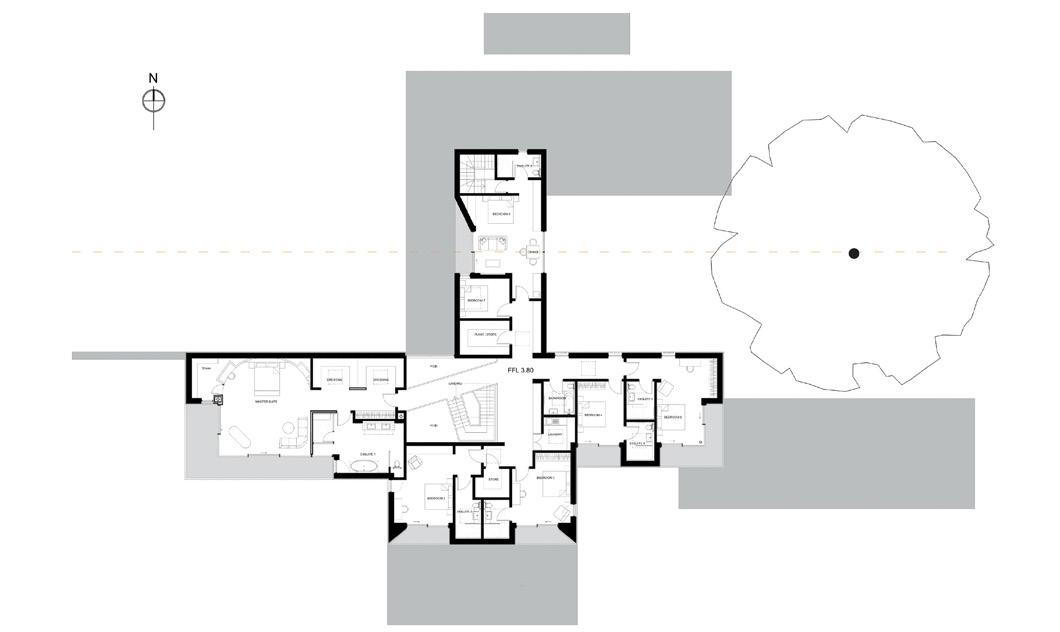

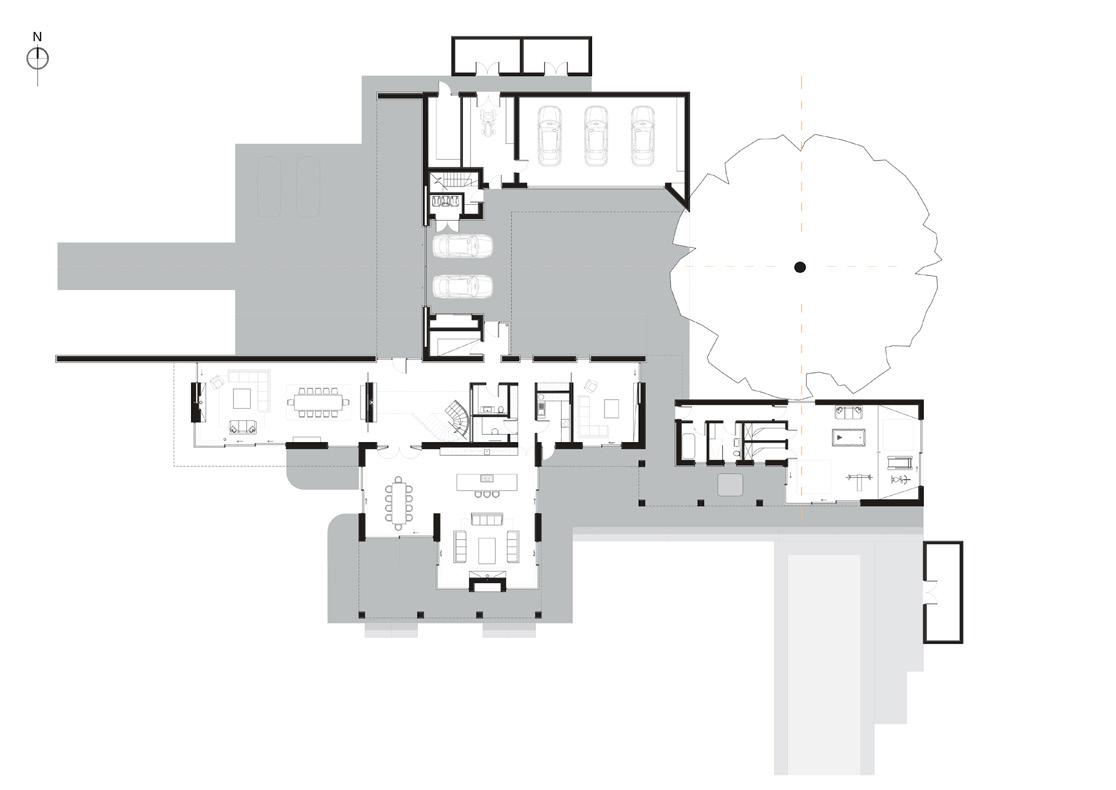

Our vision for this project in the southeast of England was to design a modern country house informed by the spatial clarity and measured order of traditional estates, interpreted through a contemporary architectural approach. The design draws on classical principles of proportion, symmetry, and hierarchy to establish continuity and coherence while addressing the practical requirements of a modern family life. We aimed to create a home that balances established architectural language with present-day patterns of living.

The layout references the ordered planning of historic country houses, creating a clear and legible sequence of spaces. Rooms unfold gradually to provide a sense of generosity without undue formality. The plan accommodates flexible living and entertaining areas alongside quieter, more private rooms, supporting a range of domestic activities.

Externally, the material palette reflects a dialogue between traditional and contemporary influences. Clay brick and natural stone are combined with aluminium and natural

timber cladding. The masonry elements provide solidity and help anchor the building within its woodland setting, while their muted tones respond to the surrounding landscape. The cladding introduces contrast and a horizontal emphasis within the overall composition.

The façades are composed with careful attention to proportion and rhythm, drawing on classical precedents in a restrained manner. Ornamentation is limited, allowing material quality and detailing to define the architectural character. The approach prioritises durability and long-term performance over expressive stylistic gestures.

A close relationship with the landscape informs the design strategy. Glazing is positioned to frame views of the

woodland and introduce daylight into the interior. Colonnades provide sheltered transitional spaces between inside and out, referencing classical architecture while supporting contemporary use of outdoor areas.

The landscape design by Park Hood forms an integral component of the scheme. Layered planting, subtle changes in level, and informal pathways mediate between the building and its setting. The landscape contributes to the overall spatial experience, creating a sequence of open and enclosed areas throughout the site.

At the lower edge of the garden, a private leisure area incorporates an outdoor swimming pool and pool house. This element is integrated into the wider landscape and designed

for informal use. The pool house reflects the architectural language of the main residence, maintaining visual continuity while establishing a distinct destination within the garden.

Constructed by Roskyle Construction, the project demonstrates careful attention to material integrity and detailing. This supports the long-term durability of the building and its function as a family home.

Interior designers Garuda Design worked in collaboration with the wider team to develop an interior aligned with the

architectural framework. Layouts, materials, and finishes reflect a contemporary sensibility while remaining consistent with the overall design approach. The interior reinforces connections to the landscape through light, views, and material continuity.

Photographed by Elyse Kennedy, the completed house engages with architectural tradition while responding to its setting and contemporary living requirements.

Des Ewing Architects

Park Hood worked in close partnership with Des Ewing Architects to ensure the simplicity of the house materials were complemented by a natural landscape on this 1.5 hectare site. Roads and paved areas were viewed as a secondary aspect of the landscape, subordinate to the setting of the house and gardens. Landscape materials, such as flint, were derived from local soil, and the pavings were made from natural clay. The driveway was uncomplicated; a local, loose gravel was used to provide an unobtrusive approach to the house, with long views of the landscape and long runs of planting toward and extending beyond the house.

The main garden sits on an axis with the house, with an ancient oak tree forming the core focal point of the project

development. The nuttery around this tree features ferns, bluebells, and a hazel copse, with the spa building set in the hazel and beech wood along the boundary. The use of core native tree species such as Scots pine, birch and beech would provide a strong framework and a loose informality to the landscape form.

The planting was designed to enable the house and garden to seamlessly blend together, meaning the beds run along the slope as opposed to vertically. Planting hugs the contours and spills out onto the curving paths. The planting palette was designed so that ferns, luzula, hazel and understorey could

benefit from the wet area and the open, sunlit meadows, with some additional drainage assuring the setting could thrive and run directly to the building footprint. The result is a garden of muted colours and quiet natural beauty that seamlessly connects the house to the landscape.

The upper area houses a cutting garden, while the lower area is an expansive native perennial meadow that slopes away from the house, surrounded by woodland walks. A series of new Scots pine copse set onto gently rolling mounds provides a winter structure underplanted with ferns and grasses. The effect is a separation of simple, uncluttered spaces which still

flow together, while also creating slightly screened views that invite visitors to explore what lies around the corner. There are stone-feature seating areas and interventions at various intervals around the garden, made from stones dug up from the land. The pathways guide a winding route into the new woodland, showcasing views over the surrounding Buckinghamshire countryside. Harnessing an existing habitat means even the informal lawns, studded with bulbs, provide interest all year round.

Johnny Park, Park Hood Chartered Landscape Architects

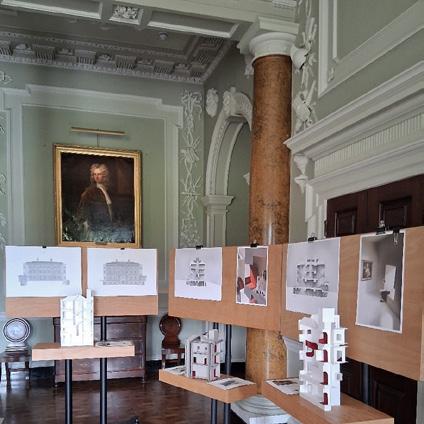

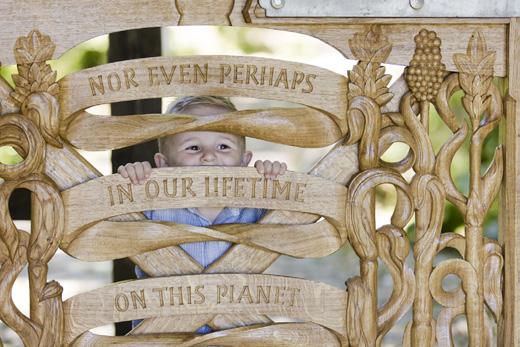

The Queen’s Masters unit, In Praise of Adaptation, was both fortunate and grateful to partner with the National Trust at Castle Ward for the duration of 2024-25. Led by Jane Larmour and Keith McAllister, the unit benefited greatly by being generously given full access to the Castle Ward Estate, its buildings and gardens throughout the year.

The Estate, which has been in the ownership of the National Trust since 1952, extends to over three hundred hectares of landscaped gardens, a fortified tower house, Victorian laundry, theatre, saw-mill, working corn-mill, barns, harbour and boathouse. Best known for its eighteenth-century mansion, this was designed as a compromise between owner Mr. Ward and his wife Lady Anne who could not agree with each other on an architectural style for their new home. Hence the house was divided in two, resulting in it being Classical to the front and Strawberry Hill-inspired Gothic to the rear. That separation in styles persists through the interior, presenting the house almost as two stage sets or ‘characters’, each with distinct personalities. It was into this unique ‘backdrop’ that the unit was able to operate and consider many other dualities, including those of identity, the permanent and temporary, the seen and unseen, whilst always considering the challenge of integrating the existing alongside the new.

Taking as a starting point the low-key but romantic beginnings of the no-longer operating Castle Ward Opera Festival and the opportunities that the architectural and landscape heritage of the estate presented to the unit, students explored the potential of the Estate to welcome a wider and more diverse audience to its doors. This began by reinforcing the central theme of In Praise of Adaptation, that the most sustainable way of building is to do so with something that already exists, and which can be made better by adaptation through careful, insightful and creative making.

That architectural position continued throughout the year, being one that sought to develop the students’ position as future architects. It did so by encouraging learning from the Estate’s buildings and their sense of place within landscape. With the Estate providing a wide range of agricultural, industrial and ancillary buildings built to support the main house, this investigation extended not just to the ‘grand’ but also, crucially, to the more modest and vernacular.

With such a varied selection of buildings and landscapes on offer, student-led exploration into areas of personal interest and individual modes of working were supported. After a series of smaller personal tasks centered on entrance, narrative and event, enriched by a study-trip to København, students were then able to develop their own projects through the

year. Importantly, working at small scales was encouraged; whether through the making of a new window, doorway, seat or route, as this would help ensure that any proposal would be embedded in a genuine understanding of the existing.

At the end of the year, the National Trust extended their generosity to inviting the students to prepare an exhibition of their work within the Estate over the summer months. This took place in two locations. The larger exhibition was erected in the laundry building, accessed from the Estate’s main entrance courtyard. This allowed the public to see the students’ work before then making their way to the Estate’s gardens or alternatively, to the main house, where a smaller exhibition of work was in place. This second display acclaimed the dual architecture of the main house alongside proposing a subtle reordering of the mansion’s interior to celebrate the ‘homecoming’ of the only portrait of Lady Anne, a painting that was only recently acquired by the National Trust.

In Praise of Adaptation and its students, Abigail, Aman, Ananya, Anthony, Caris, Cillian, Conor, Daniyal, Deimante, Eve, Hannah, Lara, Lauren, Robbie, Ruari, Samual, Seirian, Shreya and Sophiya, would like to express our gratitude to the National Trust at Castle Ward Estate and to Anne, Susan, Roisin, Chris and their colleagues, all of whom were always accommodating and encouraging of the students throughout the year. We are also very grateful for the critique, kind support, healthy challenge and engagement throughout the year from our partners at Historic Environment Division, Department of Communities: Natalie O’Rourke, senior conservation architect, HED: Nicola Golden, senior conservation architect, in addition to our guest reviewers Nicci Brock, Brock Finucane Architects and Mark Todd, architect.

Jane Larmour & Keith McAllister

Park Hood Landscape Architects are leading the landscape design for the £5 million redevelopment of Cathedral Gardens in Belfast, transforming this prominent civic space between St Anne’s Cathedral and Ulster University. Its location means it is one of the most centrally placed public spaces in the city.

The landscape scheme extends to over one acre to create a garden that is flexible, inclusive and vibrant public realm, featuring a large multi-use events space, a nature-inspired play area and an interactive digital play zone. A new memorial

will honour the 987 people who died in the Belfast Blitz of 1941, created in partnership with the Northern Ireland War Memorial Museum.

Integrated lighting and projection infrastructure will animate the space throughout the year, while new planting, lawns, seating and high quality paving create a welcoming setting for everyday use. The flexibility designed into the space will also allow it to be used for festivals, markets, music events and public art experiences

Developed in collaboration with Belfast City Council, the project strengthens connections within the Cathedral Quarter and supports the ongoing regeneration of the city centre, with completion anticipated in 2027. Perspective will revisit this project when it is opened…..

Andrew Bunbury Park Hood Landscape Architects

Hamilton Road, Bangor, County Down BT20 4LF Tel: 028 3829 4898 1 Shaerf Drive, Lurgan, County Armagh BT66 8DD Tel: 028 3832 3296

Inspired by the timeless beauty of natural materials, this capsule collection reinterprets organic textures for today’s work and living spaces

The Moxy Belfast aims to be a fun and contemporary adaptive reuse project and addition to the city’s evolving hospitality landscape. Located on Clarence Street West, at the edge of Belfast’s Linen Quarter, the 179-key hotel occupies a strategically prominent urban site.

Developed in partnership with MHL Hotel Collection, the project is the group’s first investment in both the city and in Northern Ireland. The project combines the well-established and popular international brand with a distinctly local cultural design narrative.

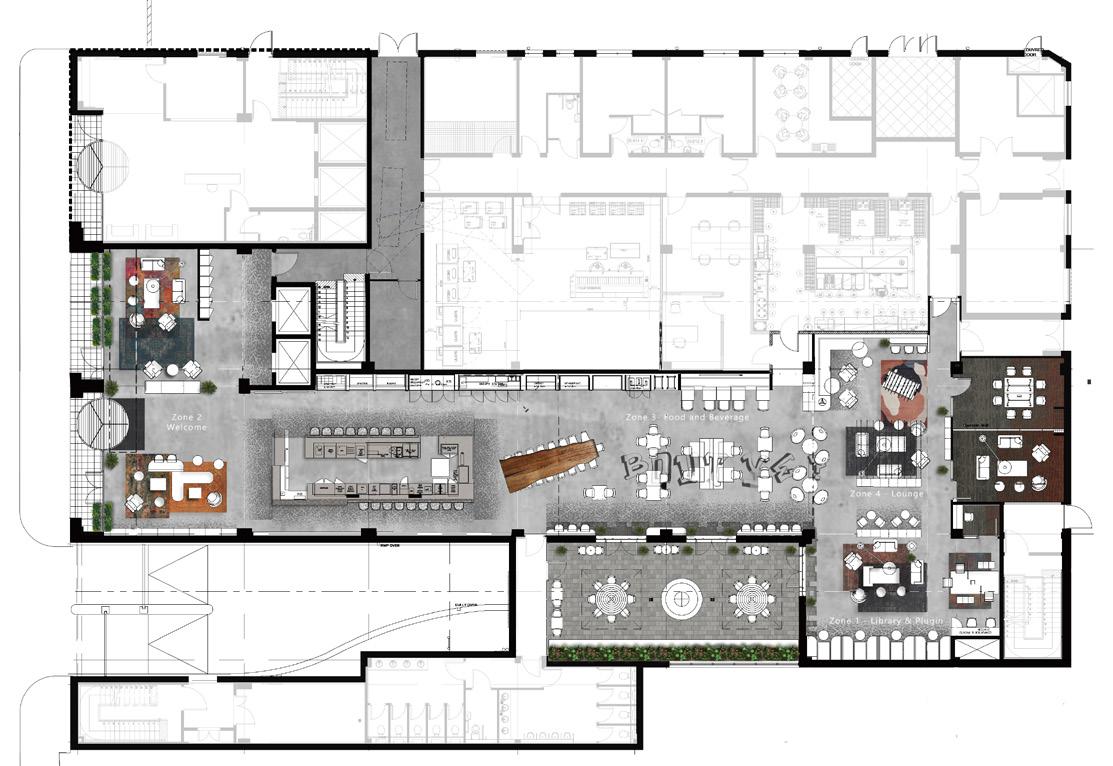

Acquired by MHL Hotel Collection in September 2024 as part of an £8 million investment, the building was formerly a Park Inn hotel, which closed its doors in 2021. The redundant building no longer met modern operational standards and the tired, run-down interior required a complete overhaul. The project team undertook a comprehensive retrofit and refurbishment, retaining the existing structural framework while reimagining the building’s spatial organisation, services and interior architecture. The ground and first floors were spatially reorganised to create a hospitality experience and 34 additional hotel rooms. This approach wcaptured the embodied carbon within the existing structure and highlights the importance of adaptive reuse in Belfast’s ongoing regeneration. The architectural strategy focused on transforming a tired building into a vibrant hotel environment that reflects the Moxy by Marriott brand ethos (playful, informal, edgy and socially engaged) while responding sensitively to its Belfast setting. The ground floor is conceived as a spatially porous, energetic social hub, where the differing functional zones connect and flow into one another, whilst retaining their own individual characteristics.

The interior design draws heavily on Belfast’s cultural identity, using narrative-driven architecture to root the hotel firmly in its place. References to the city’s music scene, particularly its influential punk and alternative culture of the late 20th century, are embedded through graphic treatments, bespoke wall art and curated installations. These elements are not applied superficially, but integrate into the architectural language of the space, reinforcing a sense of authenticity. Local expressions and colloquialisms are incorporated into lighting features and wall details using typography and illumination as architectural devices that animate the interiors while celebrating Belfast’s humour and vernacular.

Client MHL Hospitality

Architect/Interior Designer

TODD Architects

Project Team: Jim Mulholland, Jessica Sampson, Colin Gibson, Eryn McQuillan

Structural and Civil Doran Consulting

M+E Caldwell Consulting

Project management/ Quantity Surveyor Conway McBeth

Main Contractor Grant Fit-Out

Photography Eric Harford

Materiality plays a central role in grounding the design within its context. Ketley brick tiles are used extensively around the bar, referencing the red-brick architecture that characterises the Linen Quarter. This material choice provides both visual continuity with the surrounding streetscape and a tactile robustness appropriate to a high-traffic social space. A corten steel fireplace introduces warmth and texture while evoking the industrial heritage of the city. Its weathered finish recalls Belfast’s shipbuilding legacy, offering a contemporary reinterpretation of industrial materials within a hospitality setting.

One notable architectural intervention is the custom-designed pergola inspired by the iconic Harland & Wolff cranes. Rather than literal replication, the structure abstracts the geometry and

scale of these landmarks, translating them into a bold, sculptural element within the interior. This gesture bridges past and present, allowing the city’s industrial history to inform a modern spatial experience without resorting to nostalgia.