Volume 1 | Edition 1 June 1, 2024

1 Salient Identity Development & Expression Among Diverse Adopted Adolescents

Simon Boone & Dr. Rachel H. Farr 27 The Fall of Enicidem - A Fairytale & Satire of America’s Response to the Opioid Epidemic

Sophie Wingo & Dr. Anna Brzyski 15 “Terror had exterminated all the sentiments of nature”: Disease and Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown’s

Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 and the Pandemic Fiction Novel

Riley Droppleman & Dr. Michelle Sizemore

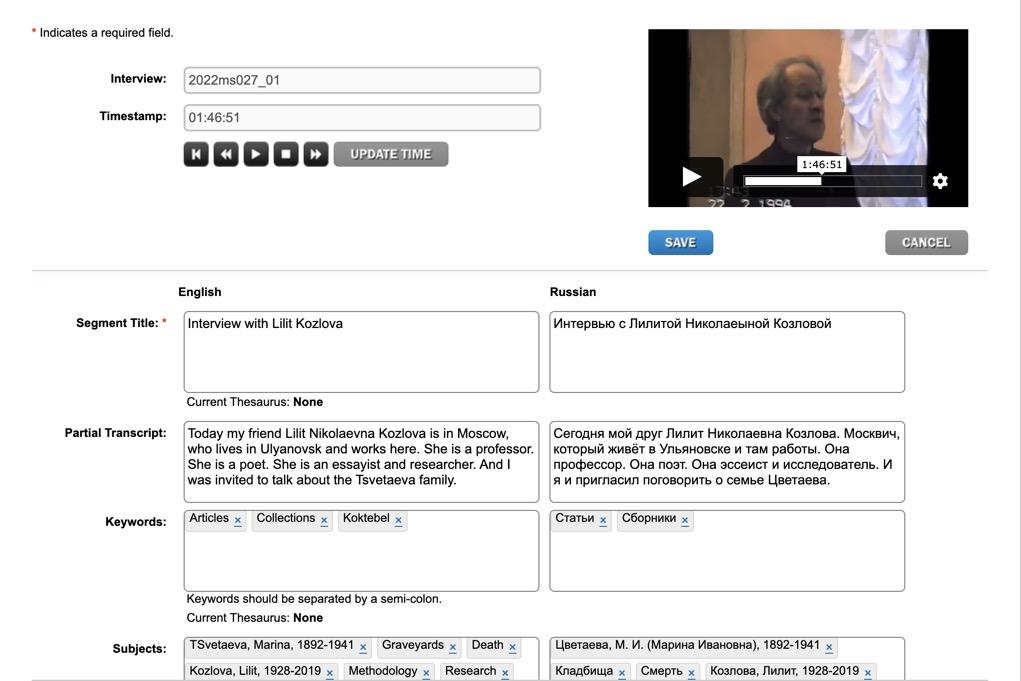

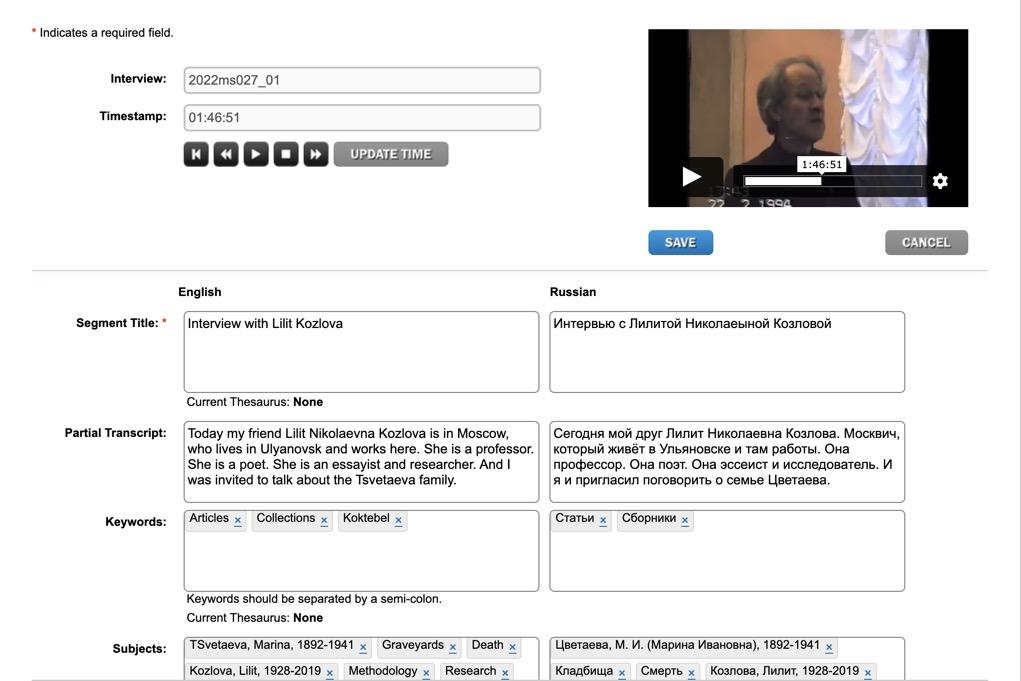

Caroline Youdes & Dr. Anthony Bardo 33 The Persistence of Memory in Other Mediums: Creating a Digital Audio Archive of Anastasia Tsvetaeva

Johnna Warkentine & Dr. Molly T. Blasing

Samuel LeRose & Dr. Christopher

Tobacco Farming in Appalachia and Demon Copperhead

Joshua Hinton & Dr. Michelle Sizemore 51 “You ought to see the corridas!”: Normalizing the Franco Regime in the 1960s through Tourism Promotion

61

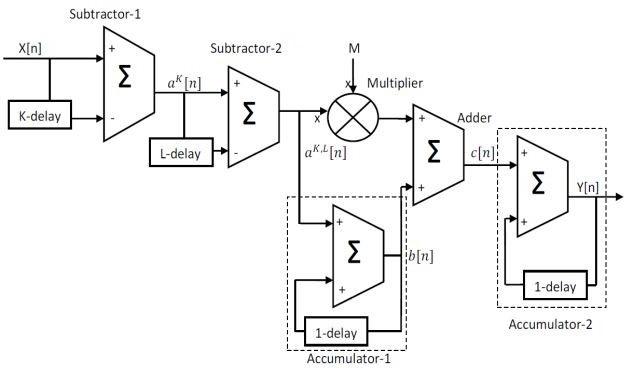

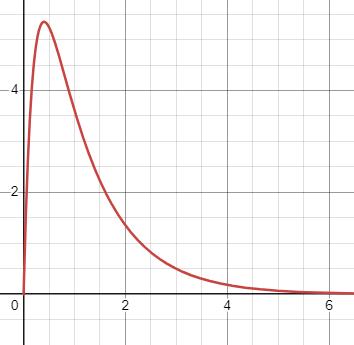

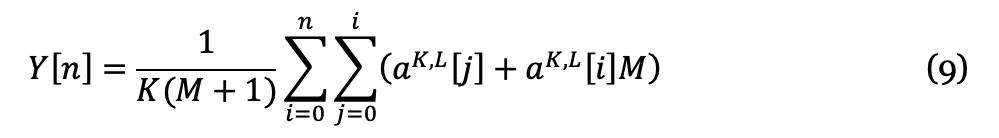

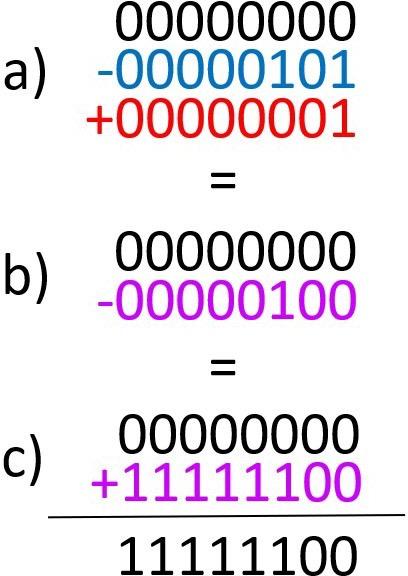

Design and Implementation of Digital Logic Filtration on Open-Source Field-Programmable Gate Arrays

Crawford

73

OF CONTENTS

TABLE

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

The University of Kentucky is home to immensely diverse, richly creative, and crucially important research. The undergraduates at the University of Kentucky have continually showcased intense dedication to their respective projects, working tirelessly to advance their elds.

Aperture arose as a way to showcase this rich scholarship. Aperture was founded as a student-run, peer- and expert- reviewed journal that would allow undergraduates across the university an accessible means to publish their work. The rst Aperture meeting took place on June 6, 2023, and was attended by Ashbey Manning, Megan Johnston, Abraham Alhamdani, Diksha Satish, and the incredible O ce of Undergraduate Research sta , Jesi Bowman and Haven Patrick. Throughout the months that followed, the team continued to grow and a true team began to form. Today, the journal has two co-Editors-in-Chief, four committees, four committee chairs, and eighteen committee members.

The rst edition of Aperture includes work in American Literature, Physics, Counseling Psychology, Creative Writing, Modern and Classical Languages, and Retailing and Tourism Management. The wide range of disciplines available in this edition re ect the exact vision held by the original founding team.

We are incredibly thankful for the committee chairs and members, students who took the time to submit their work, the mentors who supported their undergraduate researchers throughout their journey, and the experts who stepped in to review the work presented here.

It is an immense pleasure to present to you the rst edition of Aperture.

APERTURE TEAM

Ashbey Manning

Kenan Flores

Design Chair Co-Founder

Megan Johnston Editor in Chief Co-Founder

Gretchen Ruschman Editorial Co-Chair Co-Founder

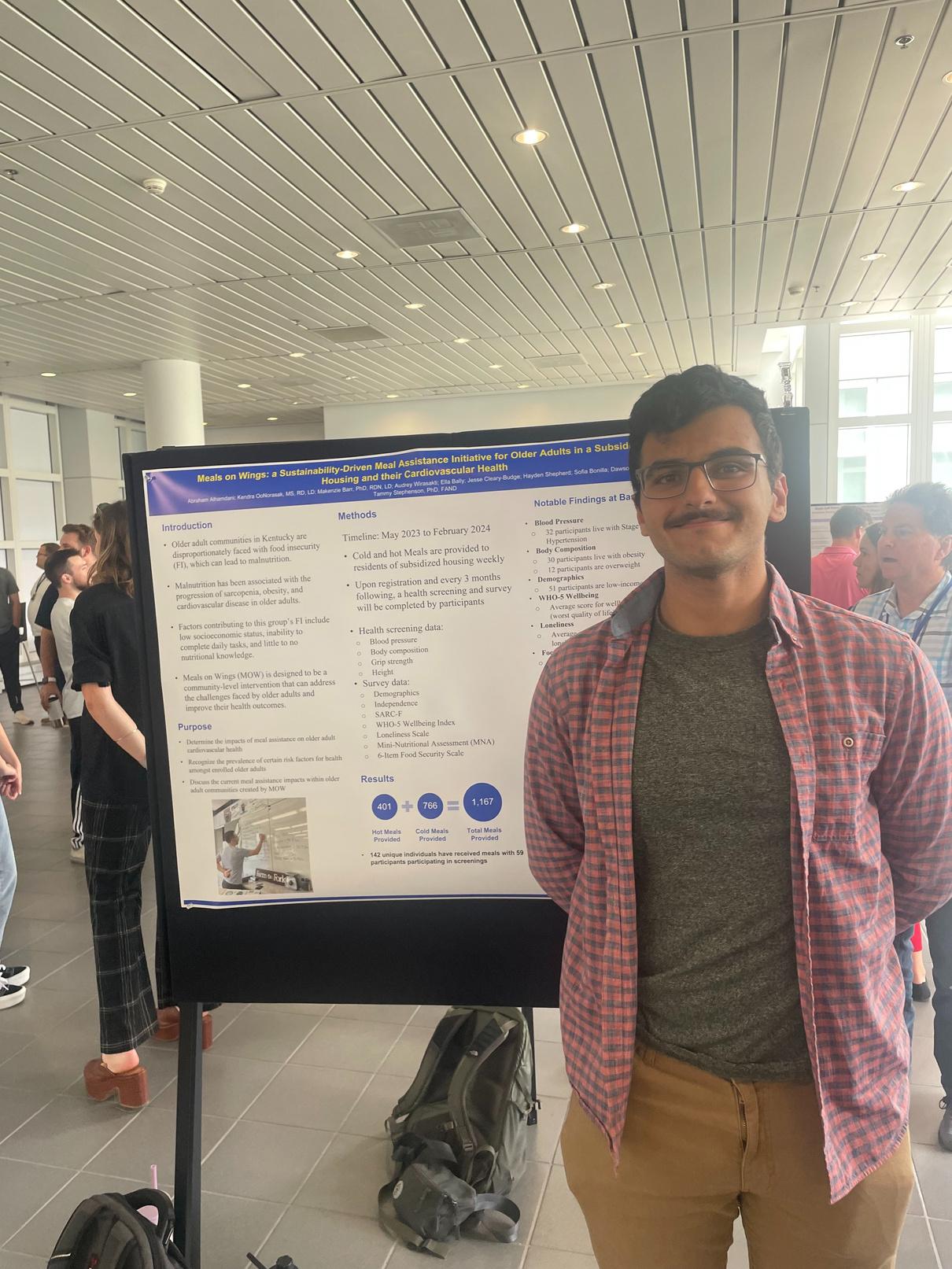

Abraham Alhamdani

Marketing Chair Co-Founder

Diksha Satish Editorial Co-Chair Co-Founder

Riley Droppleman

Publication Chair

Sai Yalla Secretary Co-Founder

6

Publication and Production Committee

Marketing and Outreach Committee

Editorial Review Committee

Simon Aaronson

Cailin McDonald

Jai

Safiyah Ashe Mill

Kasey Montgomery

Natalie Lewis

Lynzi Huggett

Anna Schroll

Gracie Burrows

Jordan Berezowitz

Caleb Weber Dexter Vilt

Alaina Taul

Elizabeth Elliott

Jaesylin Stephens

TYPING THE SELF-REPORTED, SALIENT IDENTITIES ADOPTED ADOLESCENT

1

SELF-REPORTED, IDENTITIES OF DIVERSE, ADOLESCENT

SIMON BOONE

Simon T.A. Boone is a recent graduate of the University of Kentucky with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Psychology and a Certificate in Social Science Research. He is a native of Maysville, KY and enjoys playing video games, making art, listening to metal music, and watching horror movies in his free time. Simon was a research assistant in Dr. Rachel Farr’s Families, Adoption, and Diversity (FAD) Lab since 2021. He is passionate about research regarding LGBTQ+ identity development during adolescence, identity labeling, and transgender parenthood. He is a UK Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF) and APA Summer Undergraduate Psychology Experience in Research (SUPER) fellow. He also served on the logistics committee for the 2023 Midwest Bisexual Lesbian Gay Transgender Asexual College Conference (MBLGTACC). Before attending graduate school, Simon is continuing independent research involving LGBTQ+ self-labeling. He also looks forward to being a camp counselor at Camp Lilac, a summer camp celebrating gender-diverse youth.

2

Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

Simon T.A. Boone & Dr. Rachel H. Farr Department of Psychology, University of Kentucky

ABSTRACT

Throughout the lifespan, identity is a malleable but salient aspect to development. Particularly in adolescence, valuable identities help determine social groups, acceptance, and family closeness. However, identity development during this period has not been extensively investigated in adoptive adolescents or adoptive adolescents with LGBTQ+ parents, who may have differing environmental factors that encourage and/or weaken this development. Determining the types of identities that adolescents in these populations use strengthens the investigation of sourcing these determinants. Using interview data from the third wave of an ongoing longitudinal study [REDACTED] based in the United States, central identities were described by 10 adolescents, ranging from 15-19 years old. These were distinguished by four categories: Demographic, Interest, Personality, and Other Demographic identities were the most prevalent (n = 6), followed by Interest (n = 4), Personality (n = 2), and Other (n = 2). Participants could list several identities and thus were categorized into multiple identity types. Participants with Other identities, however, seemed unsure how to answer and were not classified further. 60% did not consider their adoption status to be salient and out of the 6 adolescents with LGBTQ+ parents, 83.33% (n = 5) agreed that their parents’ LGBTQ+ identities were salient to themselves. Identity labeling amongst this sample was similar to patterns in non-minoritized and non-adopted adolescents. Future studies should investigate the prevalence of these identity types in relation to how diverse adolescents define and understand identity, given implications for developmental theory, school settings, and clinical practice.

Keywords: adoption, adolescence, identity, diversity, LGBTQ+ parents

INTRODUCTION

Since the inception of Erik Erikson’s Stages of Development in 1950 (Erikson, 1950), developmental psychologists have been further developing foundational work based on periods across the lifespan. Individuals are composed of numerous identities, with a select few becoming especially salient (i.e. prominently expressed) due to their importance, impact, and intersectionality with other identities. This concept of identity centrality, developed by Hinton et al. (2022), is what allows adolescents to independently engage with activities, social groups, and influences that positively impact their experience with a particular identity. Because of this, identity becomes more salient and valuable for individuals during adolescence, as these important influences impact their development into

adulthood and beyond (Branje et al., 2021; Erikson, 1980; Orenstein & Lewis, 2022). A core influence to identity development is one’s parents, who can pass down or model aspects of identity (Luyckx et al., 2015). Although parents’ sexuality does not appear to directly impact development (Farr, 2017; Wainwright et al., 2004), unique parenting styles and socialization as a result of same-sex, transracial, and/or adoptive family structures may stimulate diverse identity development (Watson et al., 2019). Investigative identity typing may indicate how that identity was formed and the social structures important to an adolescent if their parents are not found to be significantly impactful on the development of such an identity.

Specifically, we observe diverse and

3

Salient

Typing The Self-Reported,

adoptive identities as potential salient identities. In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw established the term intersectionality when discussing the interactions between race and gender (Crenshaw, 1989). Since then, expansive research has been performed examining the interactions between intersectional identities and the social attitudes that affirm or discriminate against these minoritized populations (Azmitia, 2023; Moffit et al., 2020; Pauker et al., 2018). In adoptive families, multiple intersections commonly present themselves, including race and sexuality in transracial adoptions and same-sex parent adoptions respectively (Barn, 2018; Goldberg, 2023).

Hal Grotevant and Lynn Von Korff (2011) examined identity through the lens of adoption, providing comparisons across all of the types of adoption, as well as interceptive strategies in the case that identity development is stagnant because of adoption status. They found that there were “highly varied identity narratives among adoptees, even within gender and age groups,” indicating that research with these individuals must be intentionally specific, as it seems that adoption status is not indicative of the development of other identities on its own.as these important influences impact their development into adulthood and beyond (Branje et al., 2021; Erikson, 1980; Orenstein & Lewis, 2022). A core influence to identity development is one’s parents, who can pass down or model aspects of identity (Luyckx et al., 2015). Although parents’ sexuality does not appear to directly impact development (Farr, 2017; Wainwright et al., 2004), unique parenting styles and socialization as a result of same-sex, transracial, and/or adoptive family structures may stimulate diverse identity development (Watson et al., 2019). Investigative identity typing may indicate how that identity was formed and the social structures important to an adolescent if their parents are not found to be significantly impactful on the development of such an identity.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

In 1950, Erik Erikson published Childhood and Society, in which the chapter “Eight Stages of Man,” first outlined what came to be later known as Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development. He described the fifth stage with the virtue of “fidelity,” in which adolescents either fulfill their identity development milestones or falter, leading to “role confusion.” Later, in 1968 and 1980, identity was explored in depth at both the adolescent stage and across the lifespan in Identity, youth, and crisis and Identity and the Life Cycle, respectively (Erikson, 1968; 1980). Under his theory, it is expected that the adolescent moves on to the next stage, early adulthood, where love is the intended developmental milestone if they have surpassed their “identity crisis.” These stages are dependent on each other in order to thrive in society.

Regarding modern views of fidelity, there have been correlations associated with societal trajectories related with fulfillment or crisis (Brittian & Lerner, 2013). Successful attainment of identity corresponded with positive psychosocial and behavioral characteristics and crisis corresponded with negative psychosocial and behavioral trajectories. However, there has not been strong methodological research examining the influences of these outcomes, especially in adoptive or LGBTQ+ families. We aim to categorize identity types in order to simplify the process of determining such influences. Such work has been previously conducted in a specific manner, investigating gender (Menon et. al, 2013) and personality (Luyckx et. al, 2014) but not the mechanisms of how these interact with identities of other types.

CURRENT STUDY METHOD

Participants

Adolescents were sampled from a larger, ongoing longitudinal study [REDACTED], where families and their adopted adolescent were interviewed on various subjects related to family, community belongingness, and social support. 10 participants were chosen because their interviews had been completed and transcribed in sync with this study. Mean

4

Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

Procedure age was 16.4 (SD = 1.66; range 15-19). 50% (n = 5) identified as male, 40% (n = 4) identified as female, and 10% (n = 1) was classified as “gender expansive.” 70% (n = 7) of the adolescents identified as the same race as both of their parents and 30% (n = 3) identified as a different race than their parents (i.e., transracial). 40% (n = 4) of the adolescents were in two-mom families, 20% (n = 2) were in twodad families, and 40% (n = 4) were in momdad families. Of the 8 (80%) participants that disclosed their sexual identities, 3 (30%) identified as heterosexual, 2 (20%) identified as bisexual, one (10%) identified as pansexual, one (10%) identified as queer, and one (10%) was self-described [Table 1].

One-hour (approximated) interviews were originally conducted via phone call or Zoom with adopted adolescents between the ages of 13 and 19, as well as their parents, as a part of a longitudinal study [REDACTED]. This study is in its third wave and is still ongoing, with data in this report being a sample. Adolescents were asked as a part of their interviews, “If you had to describe yourself to someone else, using any core identities to who you are, what would those be?” The answers to this particular question were the basis for identity classification. Identities were then classified by a three-party coding team into one of four types: Demographic, Interest, Personality, or Other [Table 2]. Additionally, participants were asked if being adopted and if having LGBTQ+ parents (where applicable) was factored into or one of their core identities [Table 2, 3]. Complete responses to these three questions are documented in Appendix A, B, and C respectively.

Identity Coding

Over a period of three months, the authors and a team of undergraduate research assistants in the University of Kentucky’s Families, Adoption, and Diversity Lab read and coded the transcribed interviews of the participants. We use thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to examine identity integration and perception among diverse adolescents (i.e., adoption, race, family structure, etc.) and the implications of its self-identification.

Codes were developed using the frameworks of identity centrality and labeling, as well as the following developed identity types. Our team utilized all parts of the interview for this coding but focused on the aforementioned questions regarding core identities, adoption, and LGBTQ+ parents. The names used in our data and results were also converted to pseudonyms in order to protect the identities of our participants.

Demographic identities are defined by Hays (2016), in which they describe culturally important and intersectional influences that compose the full person. Specifically, they refer to age, developmental or acquired disabilities, religion or spiritual orientation, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, indigenous heritage, national origin, and/or gender, although demographic data is not limited to these descriptors.

Interest consists of intentional reengagement of activities with or without advantage (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). These can be either situational interest, in which attention and effort is centered on an object or topic or individual interest, the predisposition to reengage. For the purposes of this study, we will focus on individual interest, as it more closely relates to identity presentation and development. Finally, Personality has been classified as longitudinal characteristics that are dependent on adjustment, or the lack thereof (American Psychological Association, 2018). Even though these are considered to be long-term descriptors, they are still subject to change over the course of development, particularly in the transition from childhood to adolescence (Caspi et al., 2005). More often than not, these are traits that are assigned to an individual, rather than self-perceived. Given the popularization of personality tests such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), Enneagram, The Big Five, and HEXACO, there is an increasing reliance on using personality to determine “the whole package” of an individual (Ashton & Lee, 2007; John et al, 2008). However, some of these assessments have consistently been reported to be more reliable than others (Hook et al., 2020; Stein & Swan, 2019).

For answers unable to be classified into

5

one of these three identity types, they are categorized as Other. Typically, these are answers signifying uncertainty.

RESULTS

Demographic Identity Type

A majority of our sample, 60% (n = 6), listed one or more identities that could be categorized under the Demographic identity type. Common traits included gender (n = 3) (ex., “Cis[gender] female,” Maya, 18, female, white, two-mom family), sexuality (n = 2) (ex., “Bisexual,” Katie, 17, female, white, two-mom family), and religion (n = 4) (ex., “Seventh Day Adventist,” Charlotte, 15, female, Black, momdad family).

Interest Identity Type

Of our sample, 40% (n = 4) of our sample listed one or more identities that could be categorized under the Interest identity type.

Arthur (19, male, multiracial, mom-dad family) reasoned his interest in learning, the social sciences, and business:

“I love learning about random things, interesting things, the way other people think. I like learning [sic] the way things work. Really anything is something that I like to learn. So that’s driven a lot of the choices I’ve made have been [sic] because I wanted to know, basically I just want to know. So yeah, I mean that defines a lot – that covers a lot of who I am. I care a lot about other people. I care a lot about the way things work and the way things are and why we do things. Sociology interests me a lot, psychology interests me a lot. But the reason I’m in business is because I aspire to be the best version of myself. And with that skill set, and knowing how other people work, [it] makes the most sense for me to be in that situation.”

Arthur’s passion for learning has become an integral part of who he is and how he interacts with people, therefore distinguishing it as an identity that he holds dear.

Personality Identity Type

After classification, 20% (n = 2) of our sample listed one or more identities that could be categorized under the Personality identity type.

Researcher:

“If you had to describe yourself to somebody using your core identities, maybe religion, race, things like that, to who you are, what would those identities be?”

Cole (16, male, white, two-mom family):

“Agnostic and then just like full of energy, I guess.”

This answer reflects the Personality identity type because Cole’s identity of “full of energy” influences his relationships and his perception of himself.

Other Identity Type

Some participants did not list any discernible identities and were therefore classified as Other (20%; n = 2):

“I’m not really sure how to answer that [question],” Aaron (16, male, Black, twodad family).

Our interviewers assured participants that there were no wrong answers and that abstaining from the question wasn’t an issue.

Adoption Type

Many adolescents shared that since they were adopted at birth or at a relatively young age, they haven’t regularly thought about their relationship with their birth parents compared to their adoptive parents, often considering the latter to be the former. 60% (n = 6) explicitly stated that their adoption status was not a significant part of their identity.

Arthur (19, male, multiracial, mom-dad family) described his lack of acknowledgement of his adoption status:

“I don’t think about it. Pretty much ever. I was adopted when I was five days old, right? None of my core memories. Period. Basically, the only thing that ever happened between me and my birth parents was that when I was born, my birth mother asked to see me in the room, which is what I’ve been told. And then after that, my mom sent her update emails for a while. And then eventually, she stopped requesting them, and my mom stopped sending them. And, really, that’s it. So I don’t view my birth parents as my parents, I view my adoptive parents as my parents. And so for that reason, it doesn’t really bother me ever. It doesn’t, it doesn’t sit in my brain. I can forget about it

Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

6

for months at a time. And then one day happen to remember that I’m adopted.”

One participant, Rosanna (15, female, Black & white, two-mom family) remained neutral when asked, stating that she also forgets that she’s adopted and that she doesn’t think about it often:

“I mean, maybe, I don’t really think about it that much. Sometimes I kind of forget. It doesn’t really stay on my mind that much.”

The remaining 30% (n = 3) participants agreed that their adoption status played an important part in their life but shared the forgetful sentiments of Arthur and Rosanna:

“I mean, I don’t think about it too much, but yeah I guess it is,” Jack (15, male, white, mom-dad family).

Being the Child of LGBTQ+ Parents

Of the 6 adolescents with LGBTQ+ parents (e.g., two-mom family, two-dad family), 5 (83.33%) considered their parents’ relationship to be integral to their own identity [Table 4].

Maya (18, female, white, two-mom family) indicated the necessity of introducing her moms and how it influences her:

“It’s obviously something I have to deal with. But it’s not something I have to deal with always. It’s also my life, you know? Like, those are my parents, and it shouldn’t change things, but it does. And so, you know, having to have this bomb drop of telling someone new, ‘Oh, I have two moms.’ It’s a part of my personality that is strange that I have to announce and hope that people are okay with that, and have people not be okay with that.”

Alternatively, the adolescent that indicated that having LGBTQ+ parents was not important to their identity assured that it wasn’t important because there wasn’t that much of a difference (compared to nonLGBTQ+ parents).

Rosanna (15, female, Black & white, two-mom family) stated:

“I mean, to me, it’s not that important. Like, I don’t really see that much of a difference. I mean, obviously, there’s a difference, but like, I don’t really see it. Like, I’m just normal.”

DISCUSSION

Apart from their diverse family structures, these adolescents appear to present similar salient identity types and development compared to their peers (Lewis-Smith et al., 2021; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014; Watson et al., 2019; Woolverton & Marks, 2023). That is, the types of identities are not reflective of adoptive or LGBTQ+-parent status. For adopted adolescents, biracial/bicultural identities with their birth parents and their adopted parents are commonly reflected (Manzi et al., 2014). Despite societal pressure to create hetero/gendernormative children (Lev, 2010), LGBTQ+ parents model an accepting environment for the development of diverse identities without necessarily creating one. In other words, LGBTQ+ parents communicate about identity with their children in a similar manner to non-LGBTQ+ parents but do not directly encourage certain identities (Simon & Farr, 2022). Parents, regardless of sexual and/or gender orientation, remain prominent societal paradigms for their children throughout the lifespan, even in the independently-driven stage of adolescence (Laursen & Collins, 2009).

Adolescents do indeed think of identity but not necessarily in terms of labels, as many questionnaires, studies, and social groups tend to assume (Porta et al., 2020). Instead, self-labeling, or the rejection of labels altogether, allows individuals with intersectional and/or diverse identities to better affirm their identities. This study supports the concept of identity typing, rather than labeling, to determine salient characteristics and their influences.

Limitations and Further Research

Our biggest limitation was sample size, as data in the [REDACTED] study is still being collected. Transcribing, coding, and composing data sets extends this timeline. Higher volumes of participants exceed the capacity of the FAD Lab and it is recommended that the duplication or expansion of these data sets be completed with adequate personnel. It should also be noted that as this research was conducted in the United States, western ideas and acceptance of identity cannot be generalized

7

all cultures.

For all identities unable to be categorized, they were placed into the Other category. It is recommended that future studies further distinguish emerging themes in this category, possibly negating its existence. For instance, responses that lack a distinguishable identity at all (e.g., “I don’t know,” “I’m not sure,” etc.) could be considered “No Response” instead. Quantitative methods, such as demographic collection via surveys, rather than open-ended interview questions, may also assist individuals who struggle to categorize their identity.

Pertaining to Erikson’s framework for adolescence (identity vs. role confusion), psychologist James Marcia further developed four stages that occur during this period: identity diffusion/confusion, foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement (Marcia, 1966; Yip, 2014). Perhaps dividing participant responses, based on the stage they are coded to be in based on other indicators (e.g., assurance, disclosure, comfort, etc. in their identity), can reveal patterns in the type of identities they represent. Discussions regarding adoption, identity, and having LGBTQ+ parents between the adolescents and their parents were acknowledged in the participant interviews, however, they were not explored through the lens of identity development. Future research into the intersection of identity type and parental identity modeling may reveal any correlation between frequency of communication regarding identity and the identities these adolescents choose to express.

Adoption status being majorly negated as a salient identity could be a product of the level of birth parent involvement, in which most participants considered to be minimal or absent. Studies involving close relationships with birth and adoptive parents are recommended to further inquire into this possibility.

Implications for Policy and Practice

As there were no patterns in identity typing within adolescents with LGBTQ+ parents and those with straight parents, this conclusion adds to the well-defined and growing literature highlighting the similarities between the two parent types. Typing can be an indicator of prioritizing factors that are salient to the

adolescent (e.g. salient Personality identities may be related to social group perception). This is reflected in the ecological systems of the adolescent and how they interact with or choose their peers (Brofenbrenner, 1994; Ragelienė, 2016).

The clinical aspect of identity factors into parental relationship building, based on communication, that can be beneficial to the overall wellbeing of an individual. Schachter & Ventura (2008) expand on this concept, describing parents as “identity agents,” in which parents intentionally interact with their children in order to encourage identity formation. Even if this is not the case, adolescents are more likely to approach their parents for complex conversations as opposed to their friends and peers, whom they discuss simple, everyday issues (Collins & Steinberg, 2006).

Conclusion

Although identity is something that can be discerned and categorized by research, it has been difficult to isolate predictors of salience, and in this case, type. Perhaps it is not expected that adolescents share a standard of identity but rather, environmental influences that encourage the exploration of Demographic, Personality, and Interest types. Parental identities are likely not relevant to the specific developmental framework of typing and are more aligned with how identity is discussed, if at all. Open communication between parent and child leads to more comfort in considering possible salient identities, in which they are validated and talked about in an impactful lens (i.e., how certain current events and/or environments impact the adolescent’s salient identities and vice versa)(Bhushan & Shirali, 1992; Sillars et al., 2006). Salient identity adoption is ever changing across the lifespan, developing more with insight and education that becomes increasingly prominent with maturity (Bowman & Safran, 2007). Typing, particularly within diverse populations, reveals an individual’s definition of a core identity and how that may influence their perception of other identities, whether they are visual or not.

Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted

8 to

Adolescents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the William T. Grant Foundation and the American Psychological Association for their supportive funding of this research. This study was also made possible by the coding and analytic efforts of graduate and undergraduate research personnel in the Families, Adoption, and Diversity Lab. Finally, we are grateful to the families in this study, particularly the adolescents who were willing to share their stories.

9

TABLE 1: ADOLESCENT DEMOGRAPHICS

*Note. The term “white” has been printed in lowercase, in the appropriate areas, in deference to those with minoritized racial and ethnic identities.

10

AGE M 16.4 1.66 SD Bisexual White* Two-Mom Same-race 2 6 4 7 1 2 2 3 1 2 4 3 2 1 20.0 60.0 40.0 70.0 10.0 20.0 20.0 30.0 10.0 20.0 40.0 30.0 20.0 10.0 Queer Multiracial Mom-Dad Undecided Pansexual Black Two-Dad Transracial Heterosexual Self-describe (i.e, “I don’t like labels. Men are pretty hot though.”)

/

ADOPTION TYPE ADOPTION TYPE n n % %

RACE

ETHNICITY

GENDER SEXUALITY n n n % % % Gender Expansive (i.e. “any pronouns”) 1 10.0 Male Female 5 4 50.0 40.0 Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

TABLE 2: ADOLESCENT SELF-IDENTIFICATION

IDENTITY TYPE DEFINITION EXEMPLAR QUOTE

Demographic n=6

Interest n=4

Personality n=2

Other n=2

An identifiable descriptor of age, developmental or acquired disabilities, religion or spiritual orientation, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, indigenous heritage, national origin, and/or gender (Hays, 2016).

“The psychological state of engaging or the predisposition to reengage [sic] with particular classes of objects, events, or ideas over time”

(Hidi & Renninger, 2010, p. 111).

“The enduring configuration of characteristics and behavior that comprises an individual’s unique adjustment to life, including major traits, interests, drives, values, self-concept, abilities, and emotional patterns”

(American Psychological Association, 2018).

A salient identity not otherwise specified by a given classification or by the participant.

“I’m a cis female. I’m bisexual. I’m agnostic. And I guess white.”

Maya, 18, female, white, two-mom family

“I’m an artist, and I like cats, and I have a coffee addiction.”

Rosanna, 15, female, Black & white, two-mom family

“I’m kind of the jokester of the class. Funny, creative. Sometimes quiet. Yeah.” Chandler, 17, male, white, two-dad family

“I don’t know, [my identities] all seem so normal. I don’t really know.”

Jack, 15, male, white, momdad family

Note. All participant names are pseudonyms; demographic information is self-described.

11

TABLE 3: ADOPTION SALIENCE

ADOPTION AS A CORE IDENTITY STATUS

Present (n=3)

Absent (n=6)

Neutral (n=1)

EXPLANATORY QUOTE

“I mean, yeah. It’s just people: whenever I say, ‘oh, I’m adopted,’ they don’t really understand. It gets hard after a while to explain.”

Quinn, 16, gender expansive, white, momdad family

“No. I was adopted at birth and my parents have always loved me and supported me like any other parent, biological or otherwise, would. So to me, they’re my parents.”

Aaron, 16, male, Black, two-dad family

“I mean, maybe. I don’t really think about it that much. Sometimes I kind of forget. It doesn’t really stay on my mind that much.”

Rosanna, 15, female, Black & white, twomom family

Note. All participant names are pseudonyms; demographic information is self-described.

TABLE 4: LGBTQ+ PARENTS SALIENCE

HAVING LGBTQ+ PARENTS AS A CORE IDENTITY STATUS

Present (n=5)

Absent (n=1)

EXPLANATORY QUOTE

“For sure. I think that they have, you know, given me a lot of empathy for other people. I think they were part of my start to being interested in politics and social justice and issues of that sort.”

Katie, 17, female, white, two-mom family

“I mean, to me, it’s not that important. Like, I don’t really see that much of a difference. I mean, obviously, there’s a difference, but like, I don’t really see it. Like, I’m just normal.”

Rosanna, 15, female, Black & white, twomom family

Note. All participant names are pseudonyms; demographic information is self-described.

12

Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

REFERENCES

• American Psychological Association (2018, April 19). APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/ personality

• Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 150–166. https://doi. org/10.1177/1088868306294907

• Azmitia, M., Garcia Peraza, P. D., & Casanova, S. (2023). Social identities and intersectionality: A conversation about the what and the how of development. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 5(1), 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-devpsych-120321-022756

• Barn, R. (2018). Transracial adoption: White American adoptive mothers’ constructions of social capital in raising their adopted children. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(14), 2522–2541. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01419870.2017.1384556

• Bhushan, R., & Shirali, K. A. (1992). Family types and communication with parents: A comparison of youth at different identity levels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21(1), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF01538739

• Bowman, E. A., & Safran, J. D. (2007). An integrated developmental perspective on insight. In L. G. Castonguay & C. Hill (Eds.), Insight in psychotherapy (pp. 401–421). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11532-019

• Branje, S., de Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. https://doi. org/10.1111/jora.12678

• Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi. org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

• Brittian, A. S., & Lerner, R. M. (2013). Early influences and later outcomes associated with developmental trajectories of Eriksonian fidelity. Developmental psychology, 49(4), 722–735. https://doi. org/10.1037/a0028323

• Brofenbrenner, U. (1994) Ecological models of human development. In T. Husén & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp.37–43). Elsevier.

• Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 453–484. https://doi. org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

• Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Adolescent Development in Interpersonal Context. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 1003–1067). John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

• Crenshaw, K. (1989) Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 4(1), 1–31.

• Erikson, E. H. (1950). Eight ages of man. In E. H. Erikson, Childhood and Society (pp. 247–274). W. W. Norton & Company.

• Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. W. W. Norton & Company.

• Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. W. W. Norton & Company.

• Farr, R. H. (2017). Does parental sexual orientation matter? A longitudinal follow-up of adoptive families with school-age children. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/ dev0000228

• Goldberg, A. E. (2023). LGBTQ-parent families: Diversity, intersectionality, and social context. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49(1). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101517

• Grotevant, H. D., & Von Korff, L. (2011). Adoptive identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 585–601). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_24

• Hays, P. A. (2016). The new reality: Diversity and complexity. In P. A. Hays, Addressing cultural complexities in practice: Assessment, diagnosis, and therapy (3rd ed., pp. 3–18). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14801-001

• Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The Four-Phase Model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/ s15326985ep4102_4

• Hinton, J. D. X., de la Piedad Garcia, X., Kaufmann, L. M., Koc, Y., & Anderson, J. R. (2022). A systematic and meta-analytic review of identity centrality among LGBTQ groups: An assessment of psychosocial correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 59(5), 568–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021 .1967849

• Hook, J. N., Hall, T. W., Davis, D. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., & Conner, M. (2021). The Enneagram: A systematic review of the literature and directions for future research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 865–883. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23097

• John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm Shift to the Integrative Big-Five Trait Taxonomy: History. Measurement, and Conceptual Issues. In O. P. Johns, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). Guilford Press.

• Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychol-

13

REFERENCES

ogy: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 3–42). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002002

• Lev, A. I. (2010) How queer! – The development of gender identity and sexual orientation in LGBTQ-headed families. Family Process, 49(3), 268–290. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01323.x

• Lewis-Smith, I., Pass, L., & Reynolds, S. (2021). How adolescents understand their values: A qualitative study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(1), 231–242. https://doi. org/10.1177/1359104520964506

• Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S., J., Rassart, J., & Klimstra, T. A. (2016). Intergenerational associations linking identity styles and processes in adolescents and their parents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080 /17405629.2015.1066668

• Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi. org/10.1037/h0023281

• Moffitt, U., Juang, L. P., & Syed, M. (2020). Intersectionality and youth identity development research in Europe. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00078

• Pauker, K., Meyers, C., Sanchez, D. T., Gaither, S. E., & Young, D. M. (2018). A review of multiracial malleability: Identity, categorization, and shifting racial attitudes. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12392

• Porta, C. M., Gower, A. L., Brown, C., Wood, B., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2020) Perceptions of sexual orientation and gender identity minority adolescents without labels. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(2), 81–89. https://doi. org/10.1177/019394591983

• Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2022). Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

• Ragelienė, T. (2016). Links of adolescents identity development and relationship with peers: A systematic literature review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry / Journal de l’Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent, 25(2), 97–105.

• Schachter, E. P., & Ventura, J. J. (2008) Identity agents: Parents as active and reflective participants in their children’s identity formation. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18(3), 449–476. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00567.x

• Simon, K. A., & Farr, R. H. (2022) Identity-based socialization and adopted children’s outcomes in lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parent families. Applied Developmental Science, 26(1), 155–175. https:// doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2020.1748030

• Stein, R., & Swan, A. B. (2019). Evaluating the validity of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator theory: A teaching tool and window into intuitive psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12434

• Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross, W. E., Jr, Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., Syed, M., Yip, T., Seaton, E., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. https://doi. org/10.1111/cdev.12196

• Wainright, J. L., Russell, S. T., & Patterson, C. J. (2004). Psychosocial adjustment, school outcomes, and romantic relationships of adolescents with same-sex parents. Child Development, 75(6), 1886–1898. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14678624.2004.00823.x

• Watson, R. J., Wheldon, C. W., & Puhl, R. M. (2019). Evidence of diverse identities in a large national sample of sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(52), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12488

• Woolverton, G. A., & Marks, A. K. (2023). “I just check ‘other’”: Evidence to support expanding the measurement inclusivity and equity of ethnicity/ race and cultural identifications of U.S. adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000360

• Yip, T. (2014). Ethnic identity in everyday life: The influence of identity development status. Child Development, 85(1), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/ cdev.12107

14 Typing The Self-Reported, Salient Identities of Diverse, Adopted Adolescents

“TERROR HAD EXTERMINATED NATURE”: DISEASE AND DISRUPTION

DEN BROWN’S ARTHUR MERVYN: YEAR 1793 AND THE PANDEMIC

15

EXTERMINATED ALL THE SENTIMENTS OF DISRUPTION IN CHARLES BROCKMERVYN: OR MEMOIRS OF THE PANDEMIC FICTION NOVEL

RILEY DROPPLEMAN

Riley is a recent graduate from the University of Kentucky with degrees in Biology and English. She is a Chellgren Fellow, a Gaines Fellow, and a graduate of the Lewis Honors College. She also participated in undergraduate research as a research ambassador, sang in the UK Treble Choir and UK Chorale, and performed with UK Opera Theatre. She will attend DePaul University this fall on a graduate assistantship to pursue a master’s degree in literature and publishing. Eventually, she hopes to earn a PhD in English, perform research in Medical Humanities and American Literature, and become a university professor. Her Aperture submission is part of her Senior Gaines Thesis titled “Writing New Normals: A Study of American Pandemic Fiction in the Wake of COVID-19”.

16

“Terror had exterminated all the sentiments of nature”: Disease AND Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown’s Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 and the Pandemic Fiction Novel

Riley Droppleman & Dr. Michelle Sizemore

ABSTRACT

As the world pushes into another year of living in the wake of COVID-19, we all are learning how to heal from and interpret the experience of death on a massive scale. Throughout history, the devastation of war, genocide, and plague have left trauma spanning generations, and the artwork, literature, and movements that emerge from grief capture these moments of destruction and resilience. Charles Brockden Brown’s novel Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 (1799) provides a fictionalized account of the Yellow Fever outbreak in Philadelphia in 1793, which makes it one of the earliest examples of American plague fiction. This research, which acts as a small section of a larger senior thesis, aims to reveal Brown’s association between fear and the disease itself, which both spread through spaces quickly and devastatingly. With the aid of archival research performed at the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, this research examines the effects of the plague on early American society both historically and literally. This study also emphasizes the destabilizing power of infectious diseases on urban spaces, and Brown chronicles the blurring of real-world boundaries through his fictional medium. Separation by race, class, and career disintegrates in times of crisis, and fear, rumor, and irrationality run rampant. The upheaval of society in the eyes of Brown rests on the ability of one to maintain reason, and his novel explores the perpetuity of fear as well as the impermanence of modern institutions in the face of disaster.

PANDEMIC LITERATURE: AN OVERVIEW

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we believed that the world was going through “unprecedented times”. Through the examination of previous pandemics and disease outbreaks, we can begin to visualize the commonalities between today’s human trauma and the traumas caused by diseases of the past. After four years since the pandemic started, the world is still recording new cases and deaths every day, and suddenly, we are thrust into what is likely the new “normal”. With loved ones and public figures falling ill, the COVID-19 pandemic has shaped, and is still shaping, the way we view life, the globe, science, and medicine; the tragedy and terror that accompany a disease on a large scale is difficult to quantify, but there are places we can look that give us a better idea of how humanity is coping with the effects of a

deadly disaster. Literature acts as a gauge for the sentiments of a certain period in history; from the political to the religious, authors have turned to the pen to not only comment on the events of their time but also to bring attention to aspects of their circumstances they wish to be changed. Times of universal hardship and struggle yield history’s seminal works of art, and pandemics and plagues have produced such novels.

The recent and current fight against the COVID-19 pandemic has already inspired numerous fiction novels about the effects of being quarantined in an unfamiliar place, like in Jodi Picoult’s Wish You Were Here, and the dynamics of being forced to stay at home while the world around transforms, as seen in Sarah Hall’s novel Burntcoat (Picoult, Hall). These

17

novels and many more present the production of literature as a natural reaction to a global disaster. The fiction novel allows for authors to express their perspectives on the effects of the pandemics as well as highlight any anxieties related to the experience of living through a time a fear. Popular media has presented the disastrous effects of deadly diseases spreading across the globe, with movies such as Contagion, 28 Days Later, and Outbreak visualizing the spreading of terror and the dismantling of society through storytelling (Contagion, 28 Days Later, Outbreak). The subject of disease and plague fascinates the human mind; its spread and devastation incite panic and leave humanity helpless. The thought of the transmission of something invisible to the eye, something floating in the air or living on surfaces, something that changes at such rapid speeds unfathomable in the scope of human evolution, presents a possible apocalypse to modern existence. From the Bubonic Plague of the Dark Ages to fictional zombie disease outbreaks, media across time presents these pandemics as some of the most terrifying threats to humanity.

The trend of writing fiction in the midst or wake of plagues is not a novel one. For this study, pandemic or plague fiction can be defined as fictional works that contain a contagious disease at the center of its plot, whether the disease itself is fictionalized or real. One of the earliest examples of the pandemic fiction novel is Daniel Defoe’s 1722 work A Journal of the Plague Year, which describes a man’s account of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (Defoe). First thought to be a work of nonfiction, Defoe’s novel is used as a model for the fictional witness account of real-life events. The novel has been analyzed to explain the behaviors of people, societies, and politicians during pandemics as they relate to COVID-19. An article written for Economic Inquiry describes the tendency for individuals’ behavior to become more extreme, social behavior to emphasize suspicion, blame, and othering, and officials responding to tragedy too late (Dasgupta). Albert Camus’s absurdist novel The Plague chronicles the transmission of the bubonic plague in Oran, Algeria, and the

novel’s sales only skyrocketed following the genesis of COVID-19 (Camus). Through his story, Camus reveals a pandemic’s “traumatic impact worldwide, and its interlocking with and intensification of class, racial and gender hierarchies and injustice,” which are common themes to be discussed in this paper (Kabel 4). Also, The Plague has been used to rationalize the current pandemic, with themes of “common humanity” and the idea that “COVID is a ‘great equaliser’” being at the forefront of literary discussion (Kabel 8). The importance of these novels lies in their defining of the genre of plague fiction, but their focuses remain in Europe, which produces most pandemic fiction, including German author Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, whose focus on tuberculosis and isolation in sanatoriums makes it one of the most well-known works of plague fiction (Mann).

Conversely, American pandemic fiction novels are less well-known in the tradition. By analyzing works from the American plague literary canon, one can examine the unique American experience. From the effects of a pandemic on a newly established country to the continuing American imbalances among races and classes, plague fiction reveals aspects of American society that surface during times of disaster. One of the more famous American plague novels is Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, which criticizes the capitalistic society of America as the downfall of the world (London). As stated by scholar Michele Riva, through his groundbreaking pandemic novel, London “used the plague topos to criticize contemporary social structure” to reveal that “the pandemic breaks the class barriers” (Riva et al. 1755). This study aims to focus in on institutions of American society that change and remain due to disease outbreaks throughout history. From the early years of the new republic to the contemporary times of COVID-19, American pandemic fiction reminds us that looking to the past can inform and validate our current experience, and they teach us how to continue living in a world that is forever changed. These seemingly “unprecedented times” can be compared to the literature of past pandemics, and these novels provide us

18

Disease and Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown

with patterns seen during times of trauma and disaster: the dismantling of class boundaries, the loss of entire generations, the burden of memory, the perpetuation of stereotypes, and the human need to survive.

ARTHUR MERVYN:

AN INTRODUCTION

When first meeting the titular character of Charles Brockden Brown’s Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793, Dr. Stevens stumbles upon a fatigued young man, plagued by fever and a withered frame. Taking the infected Arthur Mervyn into his home, Dr. Stevens not only nurses the man back to health but also becomes audience to Mervyn’s life story. Through Dr. Stevens’ eyes, the reader slowly learns about the ravaging by yellow fever and corruption in 1793 Philadelphia. Mervyn’s journey from the rural environment in which he feels most comfortable to the great American city starts with his disenfranchisement at the hands of his father, whose passivity leads to his new, young wife forcing his son out of the house. Seeking work, Mervyn moves into the city, where his belongings are stolen, and his luck runs low. Following several odd encounters in Philadelphia, he is offered a position as a clerk under the supervision of a local merchant named Welbeck, whose suspicious nature and duplicitous demeanor led to a scandalous murder that Mervyn must help his employer cover up. Scarred from his experience in the city, Mervyn leaves Philadelphia and decides to work at the Hadwin residence. During this time, the yellow fever outbreak hits Philadelphia, and Mervyn must venture back into the city to find someone the Hadwin family is anxious to have home. The events that follow not only paint Philadelphia as a hellscape of disease, filth, and death but also inspire Mervyn to pursue medicine as a result of witnessing the horrors of the fever and the public’s response firsthand.

In 1793, Philadelphia was a growing metropolitan city, with a focus in trade and commerce. It was a political hotspot, being the location of the Constitutional Convention and the signing of the Declaration of Indepen-

dence. Ten years after the end of the American Revolution, Philadelphia in 1793 was suddenly overrun by a new pestilence, virulent in nature and terrifying in its spread. Yellow fever, so named for the occasional jaundiced appearance patients present with, is now known to be spread with the help of a species of mosquito named Aedes aegypti. The mosquito carries the virulent blood in its stomach, biting uninfected people and transmitting the virus through the blood (Foster 89). However, the virus at the time was believed to have been spread through miasmas, which were vapors that carried infection with them. The miasma theory dominated popular thought in 1793, which is reflected in Arthur Mervyn’s scenes of the protagonist practically smelling the illness in the air of the city. Through decades of research, scientists have determined that the fever most likely originated from a trade ship from San Domingue, and the warm, humid summer in Philadelphia in 1793 provided an ideal environment for the propagation of these A. aegypti mosquitos (Langton). The mechanism of transmission was generally unknown to the people of Philadelphia, leading to the deaths of over 5,000 people in Philadelphia, a city of 50,000 at the time (Langton). Yellow Fever presents itself in infected victims through fever, chills, vomiting, weakness, and in severe cases, the signature yellow skin, bleeding, and shock, with chances of death for those who develop the severe symptoms ranging from 30-60%. (“Yellow Fever Virus”). Philadelphia’s climate, the ignorance regarding transmission, and the high death rate among severe cases combined to create a disastrous outbreak of Yellow Fever in 1793. The disease itself dominates the first part of Arthur Mervyn, but Charles Brockden Brown’s work is not about just Yellow Fever alone. Brown presents the virus as both a harbinger of death and a destabilizing agent that causes societal structure to crumble.

The time during which yellow fever rages in Philadelphia in 1793 is characterized by the complete breakdown of domestic and societal relations as well as the blurring of hierarchical boundaries defined by class and race. Charles Brockden Brown suggests that Yellow

19

Fever may not be the only pathological annihilator, but rather he highlights the danger of fear, which spreads through Philadelphia like its own contagion. Reason, Brown suggests, is the ultimate key to surviving in this time of pandemic. Through discussions of the decimation of the sentimental Hadwin family, the reliance on African Americans as hospital volunteers, and the equalizing of different classes of people, Brown presents Yellow Fever and the attendant fear that follows as major disruptors of societal order.

DOMESTIC DISRUPTION: THE DESTRUCTION OF THE HADWINS

The decline of the Hadwin residence following the appearance of yellow fever in Philadelphia serves as the quintessential model of the breakdown of domestic spaces in Arthur Mervyn. The Hadwin Family consists of Mr. Hadwin, his wife, and two daughters, Susan and Eliza. Their adherence to the Quaker lifestyle leads them to house Mervyn at their rural residence, far from the city and the corrupt activities that occur within. However, because of their rural residence, they are not aware of the fever’s arrival until after Philadelphia is seized by fear and disease. The novel’s first mention of the contagion arrives in the form of a rumor, which travels from a city “involved in confusion and panick” to the “quiet retreats” of the countryside (Brown 99). The far-reaching rumor holds immense power, as it consisted of tales in which “wives were deserted by husbands, and children by parents,” and “men were seized by this disease in the streets…they perished in the public ways” (99). These reactions to the pestilence are rooted in the historical record; Philadelphia resident Mathew Carey wrote several editions of “A Short Account of the Malignant Fever…”, which describes the 1793 outbreak of yellow fever on which Arthur Mervyn is based. This book details similar abandonments, such as “a wife unfeelingly abandoning her husband

on his death bed – parents forsaking their only children without remorse…resigning them to chance” (Carey 30-31). Caretakers and partners would desert their loved ones in order to save themselves, and the principles of nature that push parents to protect their children disappear in the face of one’s mortality. Prior to any characters interacting with the fever directly, stories of yellow fever, and more specifically the fear surrounding it, expose its ability to lead spouses to leave their families and homes. The fear is presented as almost contagious as yellow fever itself, whose visceral effect manifests like a disease; the rumor could “absorb and suspect the whole soul”, and when shared, “the hearer grew pale, his breath was stifled by inquietudes, his blood was chilled and his stomach was bereaved of its usual energies… Some were haunted by a melancholy bordering upon madness” (Brown 101). By making fear manifest symptoms in its subjects, Brown draws parallels between disease and the contagious nature of fear, terror, and rumor. This is further supported by scholar Bryan Waterman, who states that the “effect of…rumor is the suggestion that words and imagination –the very stuff of fiction – can have physical effects and even do bodily damage” (214). Even just mere rumor of the disease is enough to plague one’s psyche to the point of presenting symptoms; in fact, the fear that arises from the presence of a disease, rather than the disease itself, contributes to the death of one Hadwin. Mervyn and the Hadwin family only hear of the disease’s effect on the people of Philadelphia, yet its subject matter cultivates intense fear and panic among the daughters of the family, Eliza and Susan. Susan’s fiancé, Wallace, is in the city when yellow fever begins its reign of terror, and his hesitancy to join her in the safety of the countryside distresses her, so much so that she “would sink into fits of lamentation and weeping, and repel every effort to console her with an obstinacy that partook of madness” (102). Susan’s fear drives her to the brink of sanity, and her fits and “paroxysms” resemble a symptom of yellow fever itself, which Dr. Benjamin Rush describes in his “An Account of the Bilious Yellow Fever…”: “The patients were generally seized with rigors…

Disease and Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown

20

the pulse was full, sometimes irregular” (Rush 13). Through the inclusion of violent physical reactions driven by fear, Brown continues to underscore the relationship between disease and terror and the combined power of both to overturn lives and households. The fear of the disease is just as much a contagion as the disease itself, as seen in its pervasiveness within the household, as well as the analogous symptoms Brown ascribes to the fear. Susan’s violence escalates, with her attempting “to snatch any pointed implement which lay within her reach, with a view to destroy herself” (Brown 103). Susan’s inclination to commit suicide highlights the desperation and severity of the fear that plagues her; as people die as a result of a virulent disease, Susan desires death for herself as a result of her sorrow. Scholar Sian Silyn Roberts, in her Early American Literature article “Gothic Enlightenment: Contagion and Community in Charles Brockden Brown’s ‘Arthur Mervyn’”, claims that the antidote to such damaging effects of rumor lies in one’s ability to maintain reason. She draws distinctions between the “sentimental Hadwin household”, which is “characterized by its constituents’ ability to think the same way about things” until Susan’s aberrant reaction to the rumor, and the level-headedness that Mervyn presents in the same situation (312, 314). Roberts continues, elucidating Mervyn’s reaction to the rumor, which involves viewing it “as a fiction”, thus allowing “him to aestheticize the sufferings of the plague victims without actually feeling them” (314). This idea of separating oneself from the effects of fear through logic is seen in Mervyn’s thoughts regarding futility of succumbing to terror. Mervyn’s decision to venture into the city to find Wallace reflects an association between logic and action, one that is countered by Susan’s manifestation of irrationality and paralysis due to fear. Mervyn sympathizes with Susan’s plight, but rather than collapse into the same state of devastation, he is able to overcome the fear in order to continue living. Roberts continues her argument by claiming Mervyn’s personality reveals a new form of Enlightenment within the context of the modern city. However, Mervyn seems more representative of the broader idea of En-

lightenment, in which reason and rejection of irrationality pave the way to the modern world. In fact, when Mervyn is afflicted with the fever, he seeks refuge in an abandoned house, telling himself that his “indisposition might prove a temporary evil” and that rather his illness being a “pestilential or malignant fever it might be an harmless intermittent” (139). He surrounds himself with a blanket, sets up a source of water for himself, and rests “without fear” (139). Mervyn eventually escapes the clutches of the disease, almost seemingly through the refusal to allow for terror of yellow fever to overcome him in the way it did Susan. Through the triumph over the surrounding rumors regarding the devastation of the pestilence, Mervyn represents the Enlightened individual seemingly defying laws of nature through a reliance on reason and agency.

By the second part of Brown’s novel, Arthur has recovered from yellow fever and seeks out the Hadwin family following his treatment with Dr. Stevens. The patriarch of the family succumbed to the disease, but Susan and Eliza remain. However, Susan is not entirely well; upon Mervyn’s entrance into the home, Susan believes him to be her missing fiancé Wallace. Realizing this, the “pale, emaciated, haggard, and wild” Susan “uttered a feeble exclamation, and sunk upon the floor without signs of life” (Brown 208). Eventually, Susan would die as a result of her debilitating fear and anxiety culminating into this final episode of grief. At the conclusion of the novel, the entirety of the Hadwin household is eradicated save for Eliza, and the fear that had infected their home ultimately led to the complete disintegration of the domestic space. Brown chooses to spend an inordinate amount of his novel speaking on Susan’s affliction, which contrasts the vague recollection of Hadwin’s yellow fever death given to Mervyn by a nameless old man in the Hadwin residence. Brown’s fixation on the fearmongering nature of the disease as opposed to the affliction itself suggests that the outbreak of 1793 in Philadelphia was just as defined by its chaos among its people as it was defined by the presence and spread of yellow fever.

21

CLASS DISRUPTION: A CITY IN UPHEAVAL

As the fever continued its decimation of Philadelphia, the presence of the disease catalyzed the disintegration of class divides and human morality in the urban sphere. This phenomenon is seen in the actions and subsequent death of Thetford. Mervyn approaches the house of Thetford, finding it abandoned save for one man, who tells Mervyn that the family had perished overnight and removed from the residence. The man also details the horrific actions of Thetford prior to his passing; a servant girl, “more faithful and heroic” than the other servants that abandoned the family, suddenly became sick (121). The man believes the illness to not be yellow fever, but instead a “slight disposition” that “would have…readily yielded to suitable treatment” (121). However, Thetford decided to send the girl to Bushhill, the designated sick home in Philadelphia to which the afflicted were sent. Knowing that sending someone not afflicted with yellow fever to Bush-hill would condemn them to death, “neighbors interceded” and the servant girl “implored his clemency”, to no avail (121). The man then reveals that Thetford’s ward, and Susan’s fiancé, Wallace received the same treatment when he fell ill, and the stranger claims that “Thetford’s fears had subverted his understanding”, suggesting that fear also overcame rationality in the case of the merchant Thetford (122). Again, Brown emphasizes the fatality of fear, as seen in Thetford’s death. Despite taking these measures to prevent the spreading of the virus, Thetford eventually dies, but one of the men responsible for clearing the Thetford family’s bodies from the house claims, “it wasn’t the fever that ailed him [Thetford], but the sight of the girl and her mother on the floor” (109). The nature of Thetford’s death mirrors that of Susan Hadwin’s. Death resulting from emotional distress rather than yellow fever itself plagues the characters of Arthur Mervyn, which suggests a larger focus on the effects of pestilence on one’s ability to remain logical and rational in a time of pressure. This disruption of rationality and basic human de-

cency contributes to a diminished treatment of fellow citizens and an ignorance of the needs of others.

In addition to the paranoia and suspicion that consumes Thetford before his death, the lack of ceremony given to him and his family also represents a breakdown of traditional social hierarchy. Mervyn discovers that Thetford is deceased when he witnesses men bringing a coffin out of the residence. He also notices that “the driver was negro” and that the men’s “features were marked by ferocious indifference, to danger or pity” (108). Brown’s description of the removal of yellow fever victims can also be found in the real Philadelphia in 1793; Mathew Carey claims that “the corpses of the most respectable citizens…were carried to the grave, on the shafts of a chair, the horse driven by a negro, unattended by a friend or relation, and without any sort of ceremony” (Carey 29). Despite Thetford’s higher status as a city merchant, both him and his family are treated exactly like the general population of yellow fever victims; there is no opportunity for funeral rites or family visitors, and there is no formal burial. The distinguishing marks of wealth and privilege, including the privilege to have a well-attended service, disappear as the city struggles to handle the increasing number of dying citizens. When presented with a crisis of massive scale, the hierarchies of urban society crumble, and disease does not discriminate when it rages through a city, despite historical arguments to the contrary.

SOCIAL DISRUPTION: RACIAL ROLE REVERSAL

At the start of the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, several white physicians and citizens believes that the minority freed population was not susceptible to yellow fever. Mathew Carey repeats the thoughts of a Dr. Lining, who claims that “there is something very singular in the constitution” of this population, “which renders them not liable to this fever” (Carey 77). According to scholar Nicholas Miller, popular physician at the time, Ben-

22 Disease and Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown

jamin Rush “continued to make inaccurate claims that blacks were inherently immune to yellow fever” (Miller 153). This belief yielded a general expectation for people of color to put themselves at risk as front-line workers during the epidemic. Minister Absalom Jones wrote a discourse in response to several claims being made about the participation and behavior of the minority group. Jones mentions a “solicitation” that “appeared in the public paper to the people of colour to come forward and assist the distressed, perishing, and neglected sick” (Jones et al. 3). This expectation of whole selflessness from an oppressed population did not prevent harsh criticism from writers such as Mathew Carey, and the depictions of the workers in Arthur Mervyn provide a negative portrayal of African American volunteers and laborers. The description of Bush-hill remains a haunting moment in the novel, and the previously afflicted Wallace provides the account of his treatment at the sick house. The people at Bush-hill who are supposed to take care of the dying “neglect their duty and consume the cordials, which are provided for the patients, in debauchery and riot” despite being “hired, at enormous wages” (Brown 132). Although Brown does not specify the races of the Bushhill workers, it can be assumed that they were dominantly African American due to the words of Jones and Carey. Jones specifically elucidates that the minority population was “doing the duty of nurses at the hospital at Bush-hill” and commends them for “faithfully” fulfilling a “severe and disagreeable duty” (Jones et al. 5).

The likelihood of the Bush-hill workers being people of color combined with the negative portrayal of the attendants in Arthur Mervyn reveal a racial anxiety prevalent in the time period. The depiction of the workers as uncaring, wild, and manipulative in the face of white vulnerability creates fear of a dependence on this particular group of people, despite their contribution to and sacrifice for the fighting against yellow fever.

Suddenly, the survival of the majority population of Philadelphia is dependent on the help of an oppressed group, which underscores an inversion of power and blurring of racial boundaries that normally separates

these groups or places them in rigid hierarchical roles. Yellow fever and other illnesses originating from the West Indies or Africa were believed to not affect the minority African minority population, and this separation of immune systems allowed for white society to further separate themselves from the population; if these two groups were immune to different things, race separation could be justified erroneously through biology. As Nicholas Miller elucidates: “the simultaneous perception of blacks as contagious agents and inoculated carriers of disease served to further marginalize them as a community” (Miller 153). While at first working to support the separation of these groups, yellow fever would eventually prove this biological argument for race wrong. Upon discovering the black population’s equal susceptibility to the virus, the breakdown of these racial boundaries occurs, suggesting that the disease disrupted this part of society acutely. No longer able to justify racial differences with biological barriers, Philadelphians are forced to come to terms with the lines separating the two populations beginning to blur. Brown once again presents another form of disruption caused by the disease, and the breakdown of society in the midst of crisis forces the white population of Philadelphia to face the flaw of marginalizing a community based on an unfounded rumor.

CONCLUSION

Charles Brockden Brown’s Arthur Mervyn or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 serves as one of the earliest iterations of the American Pandemic novel. The novel presents new fears and crises to the young American state, and the downfalls of urban life reveal themselves when disaster strikes. Racial and class boundaries blur and invert during the time of yellow fever, and the disease exacerbates these issues that separate the urban space. Despite the obvious impact that yellow fever had on the city of Philadelphia, Brown specifies that fear, rather than the actual yellow fever, spelled doom for the people of Philadelphia and the surrounding countryside. Fear’s contagion matched that of the disease, and reason was its antidote, saving Arthur Mervyn and allowing him to recog-

23

nize the shortcomings of society the plague was revealing.

Brown capitalizes on the ideas of social contagion, where the focus lies in the emotional effects of the pandemic, and fear takes ahold of both the urban and domestic space. Yellow fever may be the ultimate disruptor through its equalizing nature for class and race separations, but it also provides insight into the parts of urban life that also destabilize society: baseless rumor, conflicting reports between scholars, and a fear of those deemed different. Arthur Mervyn acts a case study for the debilitating effects of fear as well as diseases’ ability to dismantle societal structures.

24

Disease and Disruption in Charles Brockden Brown

REFERENCES

• Brown, Charles Brockden, et al. Arthur Mervyn, or Memoirs of the Year 1793: With Related Texts. Hackett Pub. Co., 2008.

• Camus, Albert, and Stuart Gilbert. The Plague: Albert Camus. Modern Library, 1948.

• Carey, Mathew. A short account of the malignant fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia: with a statement of the proceedings that took place on the subject in different parts of the United States. Philadelphia: Printed by the author. 14 November 1793.

• Contagion. Directed by Steven Soderbergh, Warner Brothers, 2011.

• Dasgupta, Utteeyo, et al. “Persistent Patterns of Behavior: Two Infectious Disease Out breaks 350 Years Apart.” Economic Inquiry, vol. 59, no. 2, 2020, pp. 848–857., https://doi. org/10.1111/ecin.12961.

• Defoe, Daniel. A Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations or Memorials of the Most Remarkable Occurrences, as Well Publick as Private, Which Happened in London during the Last Great Visitation in 1665. Published by E. Nutt et al. London, 1722.

• Foster, Kenneth R., et al. “The Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793.” Scientific Ameri can, vol. 279, no. 2, 1998, pp. 88–93. JSTOR,

• http://www.jstor.org/stable/26070603. Accessed 17 October 2022.

• Hall, Sarah. Burntcoat. Faber & Faber, 2022.

• Jones, Abaslom, and Richard Allen. A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793: And a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon Them in Some Late Publications. Philadelphia : Printed for the

• authors, by William W. Woodward, 1794.

• Kabel, Ahmed, and Robert Phillipson. “Structural Violence and Hope in Catastrophic Times: From Camus’ The Plague to Covid-19.” Race & Class, vol. 62, no. 4, 2020, pp. 3–18., https:// doi.org/10.1177/0306396820974180.

• Langton, Ryan P. “Philadelphia under Siege: The Yellow Fever of 1793: Pennsylvania Center for the Book.” Philadelphia Under Siege: The Yellow Fever of 1793 | Pennsylvania Center for the Book, https://www.pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/fea ture-articles/philadelphia-under-siege-yellow-fever-1793.

• London, Jack. The Scarlet Plague. Macmillan, 1912.

• Mann, Thomas. The Magic Mountain: Der Zauberberg. Translated from the German by H.T. Lowe-Porter. Vintage Books, 1969.

• Miller, Nicholas E. “‘In Utter Fearlessness of the Reigning Disease’: Imagined Immunities and the Outbreak Narratives of Charles Brockden Brown.” Literature and Medicine, vol. 35, no. 1, 2017, pp. 144–166., https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2017.0006.

• Outbreak. Directed by Wolfgang Peterson, Warner Brothers, 1995.

• Picoult, Jodi. Wish You Were Here. Thorndike Press Large Print, 2021.

• Riva, Michele Augusto, et al. “Pandemic Fear and Literature: Observations from Jack Lon don’s The Scarlet Plague.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 20, no. 10, 2014, pp. 1753–1757., https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2010.130278.

• Roberts, Siân Silyn. “Gothic Enlightenment: Contagion and Community in Charles Brockden Brown’s Arthur Mervyn.” Early American Literature, vol. 44, no. 2, 2009, pp. 307–332.,

• https://doi.org/10.1353/eal.0.0069.

• Rush, Benjamin. An account of the bilious remitting yellow fever, as it appeared in the city of Philadelphia, in the year 1793. Philadelphia: Printed by Thomas Dobson, at the StoneHouse, No 41, South Second Street. 1794.

• 28 Days Later. Directed by Danny Boyle, Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2002.

• Yellow Fever Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 June 2022, https://www. cdc.gov/yellowfever/index.html. Accessed 25 August 2022.

25

THE FALL OF ENICIDEM SATIRE OF AMERICA’S OPIOID EPIDEMIC

27 27

ENICIDEM - A FAIRYTALE & AMERICA’S RESPONSE TO THE EPIDEMIC

CAROLINE YOUDES