The Foundation Year Program: in itself and for itself.

The Foundation Year Program: in itself and for itself.

Winter 2025 — Maenad Edition

The Foundation Year Program: in itself and for itself.

1. Busy Being: FYP as a Dionysian Experience of the West , FYP Final Lecture, Dr. Vernon Provencal (FYP 1974-75)

4. Spinning in Circles: The Search for Certainty in FYP’s Great Debate , Darius Amanat-Markazi (FYP 2024-25)

5. Interview with Dr. Amani Whitfield, New Carnegie Chair in the History of Slavery, Aliyah Daya (FYP 2024-25)

6. On Writing in FYP, Molly Rookwood, FYP Writing Coach

6. Our Co-op Book Store , Paul MacKay, King’s Co-op Bookstore Manager (reprinted from FYP at 50)

6. Hamza Karam Ally and Aruthur Schopenhauer, Susan Dodd (FYP 1983-84)

7. On A Year of Healing, Holly Currie (FYP 2024-25)

7. On FYP and Journalistic Writing, Kendra Gannon Sneddon (FYP 2021-22)

8. Instead of Hiding in your Room—Read Now!, Noah S.J. Sefcik (FYP 2024-25)

8. Chapel singing: “All the intellectual food groups,” Georgia Rose Becklumb (FYP 2024-25)

9. On FYP and Creative Writing, Abigail McGhie (FYP 2024-25)

10. On Coordinating my FYP Section in 2024-25, Eli Diamond, Neil Robertson, Maria Euchner, Daniel Brandes, Susan Dodd, Tim Clarke

13. Berlin: An Opportunity to Pay Attention—Lilacs and Memorials, Anil Pinto-Gfroerer (FYP 2020-22 not a typo)

14. FYP Pets! Heather Page, Taidgh Srivastava & Roan Wilder, Mitch Cait-Goldenthal (FYP 2024-25), Kenzie Saulnier

16. Night FYP: The Unmitigated Pleasure of Mozart , Elisabeth Stones, FYP Administrative Assistant and Deadly Soprano

18. Intolerably Stupid No More, Jane Austen Live! The Halifax Humanities Reads Northanger Abbey, Kate Lawson

19. Night FYP: “How the World Became this Way” Review of Gilgamesh at the Neptune Theatre , Aubree Field (FYP 2024-25)

20. School Prayer, Christopher Snook, Poet and Dalhousie Classics

20. A Tribute to Harry Critchley (1993-2025), Mary Lu Redden (Doctoris in jure civili)

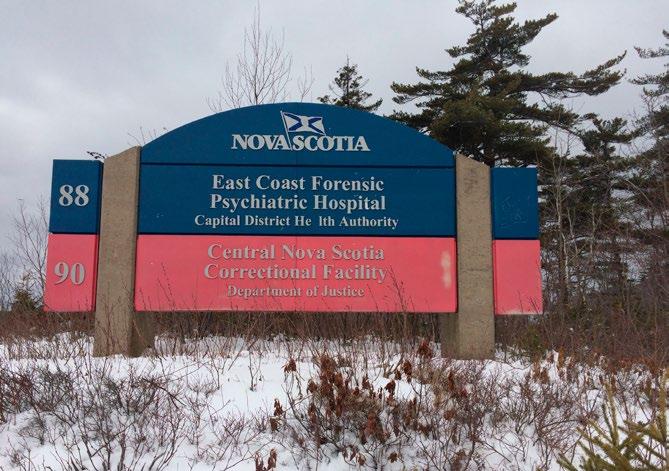

21. To Love and to be Wise: The Humanities in Prison , Harry Critchley (a Friday Meditation in the King’s Chapel from 2017)

22. “Dreaming of Medusa,” Kate Lawson

23. Ideas Worth Sharing: How FYP Gave me a Love for Translation , Lauren Konok (FYP 2022-23 and Lil’ Buddy’s buddy)

NEIL ROBERTSON (FYP 1982-83)

There is something both joyous and melancholic about coming to the end of the Foundation Year Program. I am so grateful to each of you for what you have brought to and made of this year. This moment is at once a magnificent accomplishment that you have made through this daunting and demanding program of study and yet in that accomplishment is also its conclusion. The friendships of person and intellect that have found there first life in and for you here are certainly not over, nor is the companionship of those books and figures from the past that have been discovered this year. That will all go with you and stay with you. Nonetheless the place and context, of that first connection, the Foundation Year class

of 2024-2025, is now entering into the Hades of memory, only brought to life by the living blood of your own and your fellow classmates’ powers of recollection (with perhaps the help of this edition of FYP News). However, as Odysseus teaches us the ghosts of departed souls, with which our living community is joined, can provide for us not only the continuity of memory, but also the ground and basis to know the present we inhabit and choose the future we reach out to. It is really this present and future orientation that define the project of FYP. As Augustine and Dante suggest, it is in memory that hope finds its basis: only then can change and transformation be real and sustaining. That journey you have been on has exposed

Editors: Susan Dodd (FYP 1983–84) Maria Euchner (FYP 1995–96)

Student Editor: Abigail McGhie (FYP 2024–25)

EDITORS’ NOTE: WHY MAENADS?

SUSAN DODD AND MARIA EUCHNER

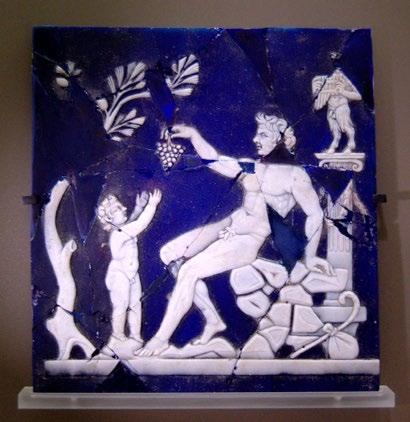

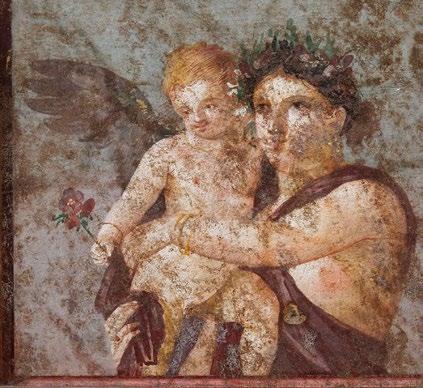

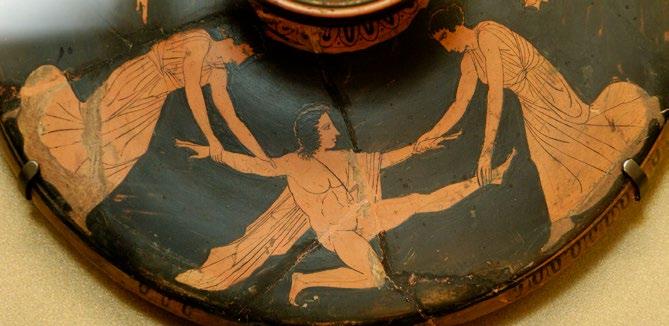

As we put together this FYP News, it became clear that, just like the maenads, this issue was firmly under the power of Dionysus. These frenzied women broke free from their conventional confinements and became followers of the category-defying god of transformation, wine, intoxication, ecstasy, and theatre. We leave it to you, esteemed reader, to locate Dionysus’ creative power in the works collated here, and we encour-

age you to attune yourself to the seemingly irrational, and not always explicable veneration of the Beautiful that permeates these pages. Animated by a diversity of passions – and perhaps by love above all – this eclectic assembly of our community’s reflections provides a snapshot of our shared experience of FYP that will hopefully resonate with you, and maybe even inspire you to join us in our maenadic dance celebrating the conclusion

Nous praktikos: Elisabeth Stones (FYP 2005–06)

Design: Co. & Co.

24. FYP Crossword , Ava Austin (FYP 2024-25)

25. FYP Section Personality Test , Eva Bisal, Anna Hartley and Ellie Rainnie (FYP 2024-25)

26. The Death and Resurrection of the Biopic: Bob Dylan, Robbie Williams, and Divine Inspiration , Matthew Vanderkwaak

29. Representations of Disability Lecture Series, Michelle Mahoney, King’s Accessibility Officer

36. If you liked this, try these!, Abigail McGhie (FYP 2024-25)

36. Answers to the FYP Crossword , Ava Austin

37. To Caravaggio, my beloved…, Maria Euchner

FYP Valentines (throughout the edition), Catherine Fullarton (FYP 2005-06)

you to not only sources of growth and renewal, but also, and perhaps inextricably bound with those green shoots, moments and deep structures of oppression and suffering that may have wounded your soul. The Foundation Year Program does not seek to bring about a specific political result, whether progressive or conservative, revolutionary or reactionary. Rather, it seeks to encourage thoughtfulness. If it has provoked in you, even in your dissatisfactions with it, a deeper thoughtfulness it has done its task. It encourages you to arrive in this moment of conclusion at your “beginning and know it for the first time.” In other words: it is all there in the circle and the centre. ❧

of a wonderfully rich year. Whether or not you see the FYP curriculum through the lens of the circle and the centre, we suggest embracing an entirely different shape: the . Congratulations on navigating the stormy seas of FYP, and all the very best for your future endeavours!

Warning: Imbibing the Dionysian spirit can lead to long-term intoxication! ❧

2025 FYP FINAL LECTURE BY VERNON L. PROVENCAL

“My lecture assumes your familiarity with most of this material through readings, lectures, and tutorial discussions. My aim is to evoke a summary recollection of your study of Western civilization by revisiting how it evolved by way of individuals having what I am provocatively characterizing as a “Dionysian experience.” To explain what I mean by Dionysian experience, we need to revisit the Dionysian experience of Dionysus in the Bacchae.”

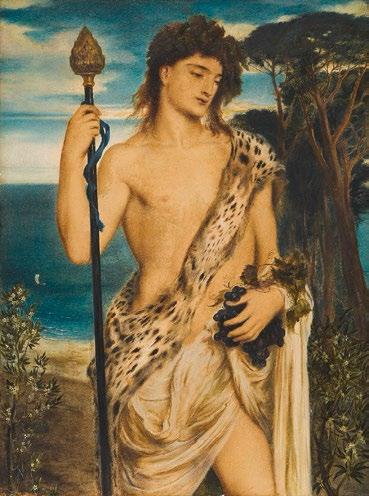

Dionysus God of Transformation

In Euripides’ Bacchae, the dramatic Dionysian experience of Dionysus as a god of transformation begins straightway with the god appearing on stage to explain “why I’ve transformed myself, assumed a mortal shape, altered my looks, so I resemble any human being.” He begins by citing the unique circumstances of his birth in the city of Thebes:

I have arrived here in the land of Thebes, I, Dionysus, son of Zeus, born to him from Semele, Cadmus’ daughter, delivered by a fiery midwife—Zeus’s lightning flash.

At the end of one of the Homeric Hymns that was likely recited in Dionysian rituals, Dionysus is celebrated as the ‘Insewn god:’

Be favorable, O Insewn, Inspirer of frenzied women!

Insewn refers to the unique feature of Dionysus as the twice-born god whom the Chorus of Asian Bacchants celebrate as they parade on stage:

with women to give birth to Dionysus, Heracles and other heroes: the passion to unite the Olympians and their mortal worshippers, to unite the human and divine. So the god who appears on stage transformed into a mortal is the god who was originally transformed at the time of his rebirth from a mortal hero into an immortal god. It is the unusual provenance of his birth that causes the Theban women led by his mother’s sisters to deny his divinity, which we’ll come back to in a moment. But first let’s have a broader look at the divinity of Dionysus.

His mother dropped him early, as her womb, in forceful birth pangs, was struck by Zeus’s flying lightning bolt, a blast which took her life. Then Zeus, son of Cronos, at once hid him away in a secret birthing chamber, buried in his thigh, shut in with golden clasps, concealed from Hera.

Dionysus is unique among the Olympians as the only god born of the union of god and mortal. Like Athene born from the head of Zeus as a goddess whose divinity manifests the mind of Zeus as active in the world, so the divinity of Dionysus re-born from the thigh of Zeus manifests the passion of Zeus as active in the world. The passion of Zeus manifest in Dionysus is the same passion by which Zeus united

Dionysus is best known as the Greek god of wine. In the Bacchae , Teiresias advises Pentheus that, as the wine god, Dionysus “is poured out to the gods, so human beings receive fine benefits as gifts from him,” which introduces the crucial function of Dionysus’s divinity in all of its different aspects, which is to be a mediator between gods and mortals, a way of uniting them.

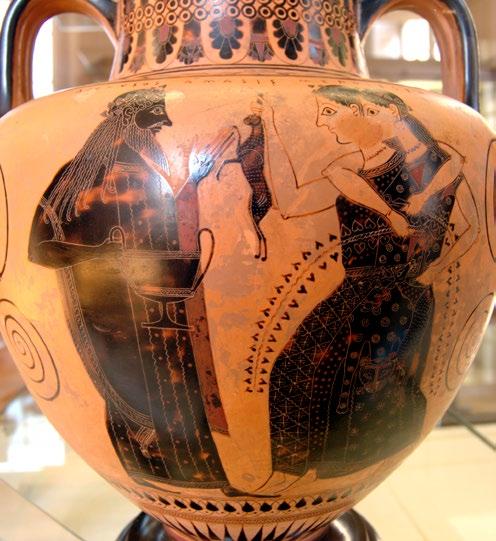

As the god of wine, his divinity was celebrated in symposia or private drinking parties, and civic wine festivals. The oldest wine festival in Athens was the Anthesteria, a three-day drinking festival celebrating the opening of new wine in the spring. According to Nancy Evans’ 2010 book, Civic Rites: Democracy and Religion in Ancient Athens ,

The transformative power of Dionysus linked the city back to the vineyard and civilized all the residents of Athens … Citizens [male and female] drank with slaves and children… The dead momentarily crossed the boundary that normally separated them from the living. The ancient rites of the Anthesteria brought the entire community together, and everybody celebrated the god of the vineyard who was also the quintessential god in the city.

In Athens, especially, Dionysus was celebrated as the god of theater, of masks and drama. Euripides presented the Bacchae in the Theater of Dionysus during the Athenian religious festival of the City Dionysia, as well as his comic Dionysian satyr play, Cyclops

Not long after Euripides died near the end of the fifth century BCE, Aristophanes presented Frogs , a comedy in which a rather cowardly Dionysus descends into Hades to retrieve the dead Euripides but instead decides to bring back the earlier tragedian, Aeschylus. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher, held that the intrinsic purpose of tragedy was to arouse in the audience the tragic emotions of pity (for the suffering protagonist) and fear (of the wrath of the gods) so as to effect at the end of the play a katharsis —a purgation—of those emotions, and thereby enable the spectators to renew their customary reverence for the gods on whom human life depended.

This Dionysian experience of katharsis was no doubt an aspect of the ecstatic rituals of the cult of Dionysus , including separate private ritual celebrations for women and men of which we know little save that, as with all Dionysian celebrations, the participants experienced enthusiasmos, mystic union with the god en theos , of the god dwelling within, by way of Bacchic frenzy or madness, the ecstatic state of Dionysian mania , perhaps in imitation of the mythic Dionysian thiasos , the band of Dionysian attendants, female maenads and male satyrs.

As E. Simon notes in The Gods of the Greeks (2021):

Dionysiac doctrine differentiated two kinds of madness: on the one hand, the indiscriminate rage inflicted by the god on opponents who refused to acknowledge him, such as Lycurgus, Pentheus, and many others, especially women of royal birth; on the other, madness as the holy rapture of the pious. Euripides depicts both kinds in the Bacchae.

In the Bacchae , the Theban women manifest the involuntary mania provoked by the god:

Theban women & Asian Bacchants

DIONYSUS: “I’ve driven those women from their homes in a frenzy [mania]—they now live in the mountains, out of their minds. I’ve made them put on costumes, outfits appropriate for my mysteries … For this city must learn against its will, that it has yet to be initiated into my Dionysian rites.”

The chorus of Asian Bacchants manifest the voluntary mania of the enthused participant in Dionysian ritual:

Dionysus! He’s welcome in the mountains … he dances, he runs, here and there … thick hair rippling in the breeze. Among the Maenads’ shouts his voice reverberates:

“On Bacchants, on... chant songs to Dionysus, to the loud beat of our drums! Celebrate the god of joy with your own joy, with Phrygian cries and shouts! When sweet sacred pipes play out their rhythmic holy song, in time to the dancing wanderers, then to the mountains, on, on to the mountains.”

Another aspect of the divinity of Dionysus is his connection to Hades and the afterlife, by which the Greek historian Herodotus identified Dionysus with Osiris, the Egyptian god of wine and the underworld. For Athenians, the main connection with Dionysus as a god of the underworld was the Eleusinian mysteries In the Eleusinian mysteries held not far from Athens, Dionysus was associated with Demeter and her daughter Persephone, fathered by Zeus and married to Hades. In the Bacchae , Teiresias associates Dionysus with Demeter as gods of bread and wine, natural and spiritual nourishment necessary to human life (the immortal gods eat ambrosia and drink nectar):

born of Semele, Dionysus brought with him liquor from the grape, something to match the bread from Demeter. He introduced it among mortal men. When they can drink up what streams off the vine, unhappy mortals are released from pain. It grants them sleep, allows them to forget their daily troubles. Apart from wine, there is no cure for human hardship.

The Eleusinian mysteries introduced initiates to Hades and Persephone as gods of the underworld and prepared them to accept their journey to the underworld where they would forever abide in the afterlife. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter recited at the Eleusinian mysteries recounts the reconciliation of Demeter (representing the realm of mortal life on earth), Zeus (representing the immortal life of the gods on Olympus) and Hades (representing the afterlife of the dead in the underworld) in the agreement that Persephone, fathered by Zeus and married to Hades, would spend part of each year with her mother Demeter in the upper world and the rest of the year with Hades in the underworld, thus uniting the separate spheres by which human life is divided. Experiencing Dionysus as a god of the underworld, the Dionysian ecstasy of the initiates would most likely effect a sense of transcendence freed from the division of the realms of Zeus, Demeter and Hades by which the initiates were purged of their fear of the afterlife and came to accept it as something belonging to the human and the human as belonging as much to the realm of Hades as to the realm of Demeter and Dionysus.

Richard Seaford sums up the many aspects of the divinity of Dionysus as essentially belonging to a god of transcendence and transformation:

[T]he cult of Dionysos had flourished throughout the recorded history of the Greeks, for a thousand years, always having at its heart the power of Dionysos to bridge the gaps between the three spheres of the world – nature, humanity, and divinity. Humanity emerges from nature and aspires to divinity.

Dionysos, by transcending these fundamental divisions, may transform the identity of an individual into animal and god. And it is by his presence that he liberates the individual from the circumstances of this life.

It is the joyful transformation of identity that underlies the importance of Dionysos in various spheres – notably the spheres of wine, mystery-cult, the underworld, politics, theatre, poetry, philosophy, and visual art.

R. Seaford, Dionysos (2006)

Socratic Dionysus: God of Ideas

How, then, does any of what we have said about the Dionysian experience of transformation and transcendence have anything to do with our study of texts in Foundation Year Program? Perhaps the best segue into that explanation is to consider one other aspect of Dionysus that is overlooked by scholars—Plato’s Socratic Dionysus in the Symposium . As we noted earlier, Dionysus was the patron god of the symposion , the private drinking party, which, as the Dionysian setting for the recitation of lyric poetry and philosophical discussion, was not just about drinking wine. Plato’s account of Socrates’ attendance at a Dionysian symposion to honor the winner for tragedy at the City Dionysia ends, I would argue, with his being crowned avatar of Dionysus as a god of ideas Symposium thus begins with a prologue in which its narrator, Apollodorus, drapes Socrates in the aura of a Dionysian mania for ideas:

Apollodorus

I take an immense delight in philosophic discourses … whereas in the case of other sorts of talk—especially that of your wealthy, money-bag associates—I am not only annoyed myself but sorry for dear friends like you, who think you are doing a great deal when you really do nothing at all.

Companion

You are the same as ever, Apollodorus,—always defaming yourself and everyone else! Your view, I take it, is that all men alike are miserable, save Socrates, and that your own plight is the worst. Apollodorus

It’s obvious that since I think this way about all of you and myself I must be manic/mad ( μαίνομαι) and infatuated [about Socrates and philosophy].

I must confess that my own experience of FYP exactly fifty years ago was very much a Dionysian experience of joyful transcendence, personal transformation and, I dare to say, profound enlightenment. It changed my life. Completely. FYP introduced me to the Socratic Dionysian experience of an intoxication with ideas . Like Apollodorus, I was absolutely manic about the Dionysian experience of ideas, and I still am.

Dionysian Experience in FYP

So, I am hoping that now that you have reached the end of your trip through FYP that you can appreciate how all the works selected for study serve to mark and explain dynamic transitions within a continuous development that we look back on from our global millennial perspective as the ‘Western Tradition.’ In most of these works, the ‘Dionysian experience’, as it were, of transcendence and transformation is recounted by an individual, whether mythic (Gilgamesh), poetic (Dante), or philosophic (Nietzsche). Each of these ‘Dionysian individuals’ envision a way of living in the world, a way answering more deeply to the possibility of the human, visions in which a new world is ‘busy being born’ within a world ‘busy dying’ to cite the phrase U.S. President Jimmy Carter repeated from Bob Dylan’s ‘It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)’. Ironically, the common Dionysian experience of FYP is to realize that what sums up one age proves prophetic of the age that follows.

Ancient Dionysian Experience of Gilgamesh

Every year of FYP begins with the Epic of Gilgamesh , which sets this ironic pattern of summing up an age in a transformative vision that proves seminal for our understanding the age that follows. In this case, as marking the transition from the temple state of the ancient near east to the Greek polis that is the beginning of what the Greeks saw as the division of East and West. And so the Epic of Gilgamesh served also to preparing the way to the study of ancient Greece as the beginning of the Western tradition.

(Continued on page 30)

DARIUS AMANAT-MARKAZI (FYP 2024–25)

The Foundation Year Program’s annual Great Debate is, in essence, an exercise in rhetorical swagger, theatrical absurdity, and a thinly veiled excuse for students and faculty to hurl artfully disguised jabs at one another under the guise of civilized discourse. This year’s topic—whether the analogy of the centre and the circle could explain the entirety of FYP—was, to put it lightly, ambitious. But what is the Foundation Year Program if not an excuse for discussion that exceeds the bounds of common sensibility?

In regard to preparation, our team largely focused on acquiring hula hoops and halos. As for the actual speeches, we agreed to prepare them individually, each in our own way. Naturally, the interpretation of this agreement varied. Most distinct was the case of Dr. Robertson, who arrived with only a pen and blank sheets of paper, upon which he began to compose his thoughts a mere ten minutes before the debate was set to begin.

Regardless, by summoning all of his improvisational power, Dr. Robertson presented a dazzling overview of the Foundation Year Program, making sure to point out the circularity of the images which define the curriculum, and the profound implications of the centre and the circle as a representation of oppression as well as the key to its destruction. Clara produced a powerful response, combining an emphasis on the dynamic nature of the present and a scathing critique of the nauseating effect of the

centre and the circle with a stage presence that gave Dr. Robertson a run for his money.

Next up was Dr. Sully-Stendahl. Drawing on her art-historical expertise, she put forward a rigorous historical and visual analysis of the art which surrounds FYP. Her presentation featured a playful (and mildly scandalous) interpretation of Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses sœurs —suggesting a rather intimate take on the centre and the circle—but quickly transitioned into a more philosophical reflection on eyes as the “threshold between the inner self and the external world”. Meir followed up with a punchy rebuttal. While he may have briefly gotten “lost in the sauce”, he proposed some earnest and intriguing alternatives to the centre and the circle; most famously, the diagonal line.

Armed with metaphysical certainty and just a hint of righteous indignation, I took to the stage to rescue my opponents from their pit of nihilistic despair—which I may have mentioned a few times—emphasizing the tension between the infinite and the finite as the fundamental reality of the human experience. Dr. Lawson returned the favour with a retaliatory threat to my S5P2 (which thankfully wasn’t acted upon), proceeded by a philosophical investigation into some of FYP’s most significant thinkers. She concluded that despite their apparent alignment to the centre and the circle, deeper analysis exposes their incompatibility with the concept. Finally, the anchor of our team, Azadi, emerged in all her glory to provide a heartfelt and illuminating account of the human disposition: one of being lost and in a constant search for certainty. She pleaded (on her knees, one might say) for the metaphor of the centre and the circle to be understood symbolically , as a representation of the belief systems we study in FYP and the certainty we derive from them. To close, Dr. Brandes provided a summary of the debate and generously cleared up some baseless accusations that

had supposedly been made against my team. He proceeded to dismantle our arguments (except for Azadi’s), unfettered by my accusation of his team having waged “intellectual terrorism” against the framework of reality itself. Unfortunately, as he neared the end of his response, it became clear that very little time was left for his own argument, although I’m sure it would have been a sight to behold. In the end, whether you saw the centre and the circle as a profound existential truth, a convenient rhetorical device, or just an excuse to bring up Renaissance nudes, one thing was certain: the debate brought some much-needed joy to Alumni Hall. In a program where most discussions teeter on the edge of an intellectual (and sometimes existential) crisis, it was refreshing to swap tutorial notes for theatrics and indulge in some philosophical grandstanding. And while some may continue to resist the truth—clinging stubbornly to their pit of despair—we can rest easy knowing that at least for one night, the centre held. ❧

In 2023, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of King’s and Dalhousie’s association, Dalhousie and King’s administration came together to create the Centennial Carnegie Chair in the History of Slavery in Canada. The position was a major step forward for the universities, promoting diversity within their curriculum and funding research that directly pertains to the history of African Nova Scotian communities.

Dr. Harvey Amani Whitfield, a prominent scholar on the history of slavery in Canada and America, was chosen to fill this position. As a Dalhousie alum, Dr. Whitfield had been a member of the King’s-Dalhousie community long before his appointment. He currently teaches classes at Dalhousie such as Slavery & Freedom in Americas and recently lectured in Foundation Year Program about the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. We sat down with him to learn more about him, his thoughts and experiences in his new role, and his plans for the next year.

Although originally from Chicago, Dr. Whitfield was no stranger to Canada or the East Coast prior to his return to Halifax. He spent six years at Dalhousie completing both his Master’s of Arts and PhD in History,

but despite living in Halifax for over half a decade, the city still feels new in a lot of ways. “Amazingly, the roads are the same [...], [but] it’s incredibly more diverse than it was when I was here the first time.” Just as the city has changed with time, so has he. In addition to now being a professor, he is also a father to a nine-year-old daughter named Hope. He remarks, “I’m at such a different stage in my life [now] that it’s very hard to compare.”

Dr. Whitfield is an absolutely phenomenal scholar. In addition to his long list of peer-reviewed publications spanning over 20 years, he has authored a number of books such as Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1860 and North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes . His research interests are wide reaching, spanning several states and provinces, allowing him to take a global look at the realities and legacy of slavery in the Americas. “I don’t think you can understand slavery in the maritimes or Atlantic colonies without understanding their connections to slavery in New England, New York, [and] the greater Caribbean.” Halifax’s library collections and their sources on slavery in Nova Scotia were “a

major reason” he took on The Chair, and will certainly inform his future research. These resources will be most applicable during the summer when he can travel to nearby cities and towns to sift through their archives and records. “I do think it’ll make a huge difference [...] because our archives are right there” says Dr. Whitfield.

Looking forward, Dr. Whitfield is excited to spend time teaching, researching, and working with students. “I see myself giving talks, teaching classes. [...] Mentoring is a big thing for me. I’ve really enjoyed that through my career.” He wants to facilitate change and opportunities that center student needs and interests. “I want to be supportive of the students at King’s, And if they think I can help out with something then I would.” ❧

MOLLY ROOKWOOD, FYP WRITING COACH

The Foundation Year Program can, at times, feel like a gauntlet, an endless rotation of readings and essays. I remember—and I see in my students now—the Sisyphean feel of it, the sense that you will be steeped in this torrent of philosophy and history and literature for the rest of time.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I loved that feeling. It was incredible being surrounded constantly by all that knowledge, day in and day out. I remember a real feeling of loss as my first year drew to a close—I knew that never again would I experience something as all-encompassing, as intellectually overwhelming, as constantly reorienting as FYP.

When I run into other King’s graduates, the question we ask is never “What year did you graduate?” Instead we ask, “What was your FYP year?” King’s students orient themselves around FYP, even long after they finish the program. It provides, as intended, a foundation for our future academic lives.

I never thought I would return to FYP. I chose, upon graduating from King’s, to pursue a publishing degree rather than stay in academia. My journey through the book world has been exciting and rewarding, and last summer, it unexpectedly led me back to

King’s when I came across the posting for the FYP Writing Coach position.

I have loved working as the writing coach this year, and I can’t wait to continue this work in the year to come. I have learned so much through my students and through this opportunity to teach writing in a very different way than I have before. I have learned where in the process students think they need the most help (invariably thesis statements) and where they need more help than they expect (invariably grammar and sentence structure). I have listened as students fretted over their marks, worried they weren’t smart enough, or adjusted to living away from home for the first time.

Writing is never just the act of putting pen to paper (or, more realistically, fingers to keyboard, which does not have nearly as nice an alliterative ring to it). I try to teach my students that writing their papers begins long before they come to see me. Writing involves engaging in the material through tutorials and lectures. It involves not just reading, but paying attention —highlighting and underlining and using sticky notes so they don’t have to read through all of Plato’s Republic again when it comes time to write about it. Writing requires taking the time to plan, to think, to wonder. It starts with asking questions and then more questions until you find your way to the question at the heart of your idea—the so what of the essay.

And more than anything, writing requires that you try. The blank page can be so difficult for FYP students to overcome,

PAUL MACKAY, KING’S CO-OP BOOKSTORE MANAGER

Operating a bookstore is difficult work under the best of circumstances: heaving heavy boxes of books wreaks havoc on your back, profit margins are slim, and there just never seems to be enough room for them. Every summer our unique location fills to bursting with just under 10,000 books— enough to ensure we have copies for every student in the program. But all that planning and effort is rewarded each year when I’m reminded that these aren’t just boxes of some disposable commodity: they represent a sizable portion of the collected wisdom of humanity spanning as far back as “The Epic of Gilgamesh”, one of the world’s most ancient texts. After school starts I’ll see students all over Halifax reading these books on their porches, in coffeeshops, or under the comfortable shade of a tree on the King’s campus. As they work their way through the Foundation Year Programme and the texts we provide, I’m reminded of how much the right book can change someone’s life and why I love running a bookstore. ❧

but if there is anything I want to impart to my students, it’s that they can only improve by trying. That’s why we write so many papers in FYP. That’s the point of the gauntlet. FYP lets us try over and over and over, and it has been so rewarding to see my students grow and develop—as writers and as people— over the course of this year. Being their writing coach has been an honour, and I can’t wait to see what they do next. ❧

BY HOLLY CURRIE (FYP 2024–25)

Hello friends, my name is Holly Currie and I’m a first year journalism student. One thing I lack at sharing is that I’m an author of a poetry book, which still shocks me to this day. My book is called A Year of Healing , and the idea to write this came to me on a whim. In January of 2023 I was writing poetry for my English class, and I hated each word I wrote. During this time I was also diagnosed with depression, and I didn’t know how to control my feelings. I went down to my highschool library one afternoon and the librarian, whose name is Katleyn, asked me what I was doing in English class. I told her we were doing poetry, and she asked to see my poems. I decided to show her the poems, convinced they were terrible and just a horrible display of my feelings. When she finished reading them, she looked at me in shock. She told me they were amazing, and that she could feel what I was feeling, relating deeply to the words on the page. I couldn’t believe what she was saying, so I reread the poems. That’s when I saw the potential.

KENDRA GANNON SNEDDON

“Writing is so easy. I barely have to try during English class,” naive high school me said before my first FYP essay. I was a student who never got below a 90 in English and never worried about passing the English exam. My friends came to me to proofread their essays and fix any typos or mistakes. I was confident that I was the most fantastic writer and that the FYP would be a breeze. And then, I got my grade back for my first FYP essay… Boy, was I wrong.

When my first FYP lecture ended, I was lost. I couldn’t keep up my notes as the lecturer was talking. I read the chapters the night before, but I didn’t know what any of those words meant. Then, it was time to go to

The next day I sat in the library and made a plan: I would write poems consistently for a year, after being diagnosed with depression, working through my emotions with words. It is my journey through a year of prioritizing myself—my mind, my body, and my soul. Depression doesn’t just go away, and that is the sad reality. I struggle with it every single day, and in my book you can see the variety of those feelings. It’s not just being sad, it’s feeling unworthy of life and hating your body with every breath. There’s many reasons why I wrote this book, but the main one is that I want people to know that they are not alone. That what they are feeling is valid no matter if you have depression or not, there is someone else going through something similar.

Finally, in October of 2024 I self-published my book on Amazon. When I submitted my book to be reviewed and authorized by Amazon to be published it was the most agonizing feeling of my life. It took 3 days to premier on Amazon after submitting, and then I was constantly checking my phone to see if it got approved. As a first time author, Amazon was a great way to get my work out there, and I even have my book on the shelf of my favorite local bookstore, Pages & Pieces Boutique. This is my first book ever written, and it certainly won’t be my last. I

tutorial and boast about what I had read. In simpler words, I was screwed. Before I knew it, it was time for the first FYP essay. I put together my thesis, included my evidence, and wrote confidently. I felt good about the submission. I opened my evaluated essay and scrolled down to the bottom for the grade. “It’s my first essay. I should expect a B- or even a C+,” I said, setting my expectations low. Imagine my disappointment when I received a C-!

I had some work to do if I wanted to improve my grades for the following essays. But that can be hard when, every Tuesday, you are learning to do the exact opposite for journalism. Yup, everything my tutor advised me to do, my journalism professors told me to do the opposite, and vice versa. I was stuck.

I kept getting comments like “Too much like an essay” and “Needs more substance and better vocabulary.” Although these two writing styles seem contradictory, eventually, they have made me a better writer.

I learned that evidence in both essays and journalism articles is essential. You can’t have enough evidence in both. I also learned a lot of synonyms and words that were the same but different for both mediums. I honed in on the inverted pyramid and flipped it while writing my FYP essays. I started to read quickly and pick out the important facts like nobody’s business. Ultimately, I could write a FYP essay in less than five hours (I may have chosen to go downtown over writing that weekend) and became even more prepared to write journalism articles. As I near the end of my four

already have book 2 and 3 on the go, and I can’t wait to see what this journey has in store for me. If you want to keep updated on the progress of my next books you can follow me on instagram @holly2006511, and as always, you are worthy. ❧

years at King’s with only a couple of months left to go, I have to thank FYP because it’s one of the only reasons I made it this far. I am one hundred per cent a more substantial writer because of it. My journalism is more vigorous because of it. I am stronger because of FYP and the thick skin I gained from having my essays dragged through the mud. Yes, FYP can be hell sometimes, but looking back, I wouldn’t choose to do any other program. ❧

The Read Now Events at King’s is a great way to complete your readings for the plays and performances as it is engaging and fun. It does not matter if you are an actor or have never done acting before; you can simply choose a character and voice them. Everyone is patient with you and while I have struggled with a couple words here and there, everyone is always supportive and encouraging.

It’s also a great place to attend even if you aren’t particularly interested in reading the work or uncomfortable with acting. Watching is just as fun, especially since some students who participate really give it their all. I have watched friends practically yelling at each other while reading because they are in character. It is an amazing sight to behold and even better when you are the

the intellectual food groups”

GEORGIA ROSE BECKLUMB (FYP 2024–25)

I didn’t come to King’s for FYP.

Don’t get me wrong; FYP is awesome, but a bigger draw for me was something even more unique about King’s than the Foundation Year Program; I’m here for the Chapel Choir.

I spent hours going through viewbooks last year. I’m pretty sure this choir is the only one of its kind in Canada.

The Chapel Choir is unique because it’s a working choir. We sing in service twice a week, different music every service. We sing alongside professionals. It’s the ultimate musical apprenticeship. It’s also reliably the best part of my week.

Understanding the FYP texts is careful, quiet work for me, involving highlighters and silent spaces and notepads. There’s something deeply satisfying about it, about making sense of things and reasoning it through. I love it, but I need choir in my life too.

There’s something so freeing, after a day of lecture halls and hushed libraries, about going to choir and opening my mouth and making sound, and making it as emotionally

one standing up and monologuing, while your fellow student waits patiently to retort their response. Many students fully embrace their roles, and it’s incredible to see those who might feel uncomfortable step out of their shell with confidence. This is excellent because you have people who come to the events feeling awkward or overwhelmed and come out confident and happy because they took the time to show up and put themselves out there.

Between each major scene or act we often review what has happened. We did this when we read Hamlet since it can sometimes be difficult to discern what is actually being said. This is very helpful to make sense of the piece. Maria Euchner also brings candy and offers it upon entering and leaving, which is amazing since my friends, and I all have a sweet tooth.

One of my friends has thoroughly enjoyed the Read Now Events and says that they are, “fun and a good way to get the reading done.”

Another one of my friends says, “The Read Now’s are very engaging, and it is very fun to act in them.”

I also recognize a lot of the same people going to the events. Sometimes they can’t

and generously as possible, about doing it with people, about doing it for people, about feeling together.

Not that it’s all touchy feely artsy fartsy all the time. I spend a very good chunk of my time in choir learning to count to four under pressure. Then there’s the Latin, and watching the director, and figuring out the intervals and paying attention to how Hillary, the other soprano, is pronouncing the ‘ai’ in ‘saint’. I tend to go more ‘eh’, and she tends to go more ‘aih’, and I’ve been trying to do more of an ‘aih’ thing too, but I keep forgetting, and my point is, when I’m singing, my whole brain has to be on the job, or else I get hopelessly lost.

I can worry about my FYP essay while swimming at the Dalplex, I can feel guilty about not reading ahead while scrolling through Instagram, I can think about Dante while on the phone with my mum, listening to her tell me about her adventures in wainscotting installation, but I can’t do choir and FYP at the same time.

Choir gives me real brain break, and it’s

stay long but they always make an effort to show up, even if it’s only for 30 minutes. The other people that attend are very friendly and I have made friends with some of them either before or after meeting them at the events.

As I mentioned, the event is a fantastic way to complete the readings. Instead of hiding in your room for hours, you get to go out, socialize, and act out the characters in a positive environment that is both supportive and fun. ❧

a break I can’t miss.

Chapel Choir has been jokingly called slave labour. Maybe pleasant, indentured labour would be more accurate. At the start of the year, I was given a scholarship through the Chapel Choir. The time commitment was laid out. I took the money. I can’t back out now. I can’t not feel like it today

I think this is one of the main differences between choir and other extracurriculars. Choir isn’t just a break from the world of FYP going on in the Quad. It’s an imposed recess, as fixedly unmissable in my mind as a class. Maybe more unmissable.

If I miss tutorial, conversation may be slightly less animated. If I miss choir, chords could be missing their identifying notes! That just won’t do!

Choir forces my brain to take a break from FYP, and my thinking is all the better for it. Between FYP’s quiet, private reasoning, and choir’s loud, public feeling, I feel like I’m hitting all the major intellectual food groups, and I’m loving it. I couldn’t think of a more complimentary pairing. ❧

I have always been a writer. My first foray into writing, penned at some point during my early years, was a short poem entitled ‘Fleece for Lease’. I believe the premise is self explanatory. Since this time, I have branched away from this sort of deep, soul searching poetry and discovered my real affinity for short fiction. I attended Canterbury High School in Ottawa for their literary arts program, getting the truly amazing opportunity to learn and write alongside a class of other people doing exactly the same thing as me. At some point over the course of these four years I personally like to think that I became a good writer, shaped through the influence of classmates, teachers, and friends.

In the fall of 2023, I submitted a piece to the youth short story section of the Amazon Canada First Novel Award (AFNA), hosted by The Walrus . The award invites students between the ages of 13-17 to submit their short fiction under 3000 words. A sentiment I’m sure other creatives can relate to—I felt that my piece was simultaneously the worst and best thing anyone has ever created. This to say I was incredibly surprised when I learned that I was one of six national finalists for this prize, and yet also not at all.

The awards ceremony took place in Toronto in June 2024. Long story short, I didn’t win the grand prize. Still, I can’t bring myself to feel shortchanged in any way. All of the short stories nominated were incredible, I got a copy of each of the novels short-

listed in the main category, and a free trip to Toronto plus runner-up prize money. Seriously, if there are any young writers reading, you should try your hand—it was a great experience. Not only that, but the feeling of having my work recognised in this way is something I will truly never forget.

Having written creatively for pretty much my entire life, the process of switching to academic essay writing at King’s was a little bumpy. Creative writing is largely about painting a picture, and writing essays requires a different brush. It’s been hard for me to kick the habit of persuasion over decoration. In FYP, every sentence written needs to contribute to the point of the paper. No longer am I allowed to wax poetic about the way the moon looks—that job belongs to the source I’m analysing.

FYP itself has also been extremely influential in my writing. In reading all of these texts from across the Western canon, I’m seeing firsthand the origins of some of my favourite tropes, styles, and genres. I see

FYP reflected in everything I have written, including my piece shortlisted for AFNA. It is about a man in dialogue with God, worried he has made the wrong decisions in his life. As I read St. Augustine’s Confessions earlier this year, I was struck with the similarity and reminded again and again of how humanity will continue to have the same questions for the rest of time—just phrased in slightly different ways. Creative writing and essay writing have the same goal in this aspect: to answer these ever-present questions however possible.

If you’d like to read the shortlist of AFNA youth short stories, for the first time in the award’s history they have all been published on The Walrus’ website. I have continued to write fiction throughout this year at King’s, and I have continued to try and answer as many questions as I can. Still, I doubt anything can top the mastery I demonstrated in my magnum opus, ‘Fleece for Lease.’ ❧

This year I was simply filling in for Kyle Fraser on sabbatical, and so for the most part I stuck with his superb choices from the previous year. There was nonetheless a bit of space for some exciting additions to our study of antiquity. The first Night FYP of the year was a solo folk opera entitled Sappho’s Garden , written and performed by FYP alumna Nicole Harris of the Spare Key Collective. This marvellous play rediscovers the fragmented remains of Sappho’s poetry through a contemporary lens, and I introduced the evening with a lecture on Sappho and Greek lyric poetry which primed the audience for Nicole’s performance, bringing King’s perennial Sappho-mania to new

heights. Another exciting innovation was having the Fountain School’s Dr. Roberta Barker lecture on Euripides’ Bacchae, re-introducing a Dionysian thread into FYP which will be taken up by my Prince lecture in March as well as the final FYP lecture of the year by Dr. Vernon Provencal. Finally, following the excellent idea which emerged in planning FYP this year that every section should have a devoted art lecture, I asked my Classics colleague Dr. Peter O’Brien to give a sweeping overview of ancient art, and he offered students a wondrous whirlwind tour through Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Rome.

There is a tension at the heart of coordinating Section Two: The Middle Ages. The section covers over a thousand years of historical and cultural development that is longer than the four subsequent sections combined. It takes FYP from the Mediterranean world of the Ancient Section to the Modern World of sections 3, 4, 5 and 6 focused on Europe and especially Western Europe as the centre of what comes to be called “the West.” The sensible thing would seemingly be to have as many lectures on as many topics as possible to simply try to do justice to the range and complexity of this era. The contemporary demands of diversity would seem to require such a decision even more so. Look at what is being left out or marginalized. Why expend half of the lectures in the section on two works and two works of specifically Christian, indeed Western or Latin Christian, reflection? Augustine’s Confessions and Dante’s Divine Comedy , framing either end of the Medieval World, can hardly be said to capture the many aspects of the Middle Ages. Of course, a similar act of discrimination occurs in Section One in its focus on Hellenic Culture or in fact in the foci of other sections. But because of its definite and specific religious character, the time spent on these two Christian texts can seem misguided and disproportionate. So what justifies this outrage? Certainly not the notion that Latin Christianity and its development on the Middle Ages is truer or more inherently valuable. The only possible justification is that it is

integral to grasping the explicit object of study of the Foundation Year Program: the development of “the West.” Just as we need to enter deeply into the Hellenic world through Homer and Plato, so we need to enter deeply into the Medieval world and Augustine and Dante are wonderful and powerful agents for such an experience and exposure. It is for this reason that they have been the fundamental to this section of FYP. But it is equally important to bring diversity and disruption to these intellectual and spiritual figures by bringing to light the ways in which the Medieval World is also the Jewish and Islamic Middle Ages. It is also the world of alternative spiritualities and beliefs: the enchanted or magical world of fairies and green knights. That that Medieval Development is unthinkable without the interactions, both with the more advanced civilizations of Medieval Islam and Medieval Judaism and the pagan and pre-Christian worlds is undeniable. Medieval Christendom, as it often thought of itself, defined itself through a complex interaction of positive influence and coexistence and negative misunderstanding and violence with these other cultures. There is no Middle Ages without them. Undoubtedly any given effort to balance coherence and disruption is open to challenge. This year’s section two was just one effort at this task of trying to make open to us this period that is crucial to the modern world in which we live and move and have our being.

Being tasked with the coordination of Section III was an exciting challenge. Although the Renaissance is not my “home” section, i.e., it’s not the period in which the majority of my scholarly work is concentrated, it is a period that has actually been closer to my heart than I initially realized. I have loved Shakespeare ever since I encountered him in school (albeit in German translation), and then more profoundly in a Shakespeare seminar during my undergraduate degree at King’s – this also marks the beginning of my intense love affair with Hamlet that is still ongoing – and I taught a course on “Love, Lust, and Desire in Italian Renaissance Art” for EMSP in 2024. The beautiful thing about FYP is that nothing comes from nothing, and the conception of a section is always in dialogue with previous iterations, as well as the other sections. I thought about how the section could make best sense within the larger narrative of the curriculum, and which texts might correspond well with those from Sections 1 and 2,

as well as look forward to what still lay ahead in Sections 4, 5, and 6. A balance of various access points was important to me: philosophy, literature, art, music, and science, and certain factors seemed non-negotiable. I thought the section needed to address the Reformation/Counter-Reformation, politics, different forms of colonization, women’s perspectives, the new centrality of the human subject, a discussion of social class, and the prevalence of the theatrum mundi (theatre of the world) trope. The latter aspect, which affected so much more than the theatrical stage – think of the important convergence of statecraft and stagecraft we see in Machiavelli’s The Prince and Elizabeth I’s carefully crafted public persona –motivated me to assign three very different plays: a comedy, a tragedy, and a tragicomedy. While this decision is potentially controversial, I am convinced that each of the plays offers us unique and distinct opportunities for ek-stasis , sharpening our willingness and capacity to seriously consider viewpoints

What to do with all the philosophy? This is the great and abiding problem that confronts every incoming coordinator of Section IV. In my time in FYP, there have been various strategies for dealing with the theoretical weight of the period, and colleagues were generous with advice: reduce Descartes to two lectures! Streamline the social contract theorists by leaving out the social contract theory! Eliminate the amenable Hume altogether! (I decided to pass on options A and B, but alas, I did put the kibosh on the gentle Scotsman.) I was also urged to get creative: Couple Leibniz with the Emperor of China and Locke with John Marshall, and thereby leaven the theory with

history and politics! Boom. Done! I knew I wanted to replace Voltaire with Molière (and thereby dramatically elevate the quality of Frenchman in the section), and Newton and Mozart were indispensable anchors. Cugoano has long been a staple (and a favorite), so there was no room for maneuvering there. Given all these givens, there was only so much room for genuine innovation, and I’m pleased with the two departures we made this year: the introduction of Spinoza (as a Maranno and biblical critic, as well as the first ‘secular’ man); and the return to FYP of the

magnificent Jane Austen (by way of

wholly different from our own, and maybe even enabling us to embrace discomfort or moral ambiguity. Invariably, one’s vision of a section will never please everyone, and it is always an experiment, the result of which is unpredictable, but that’s what makes teaching in FYP so exciting. I feel eternally grateful to have had the most amazing lecturers bring my particular vision of the section to life, and make it the success that I believe it was.

a banger of a novel likely unencountered by students in high school or on Netflix). To be sure, I second-guessed every cut, every Thursday lecture, every bump up (or down) in pages… and I’m still peeved about the absence of Dr. Samuel Johnson (the literary critic’s literary critic). Who cries for the good Doctor? Happily, there is always next year!...

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it” Marx wrote in 1845. We are called to action in Section V, to put flesh onto the ideals of earlier times. The French Revolution executed change: the king and queen are guillotined as ordinary citizens (killed in a way both efficient and “humane”), measurements are rationalized, time itself is inscribed in reason’s terms— overwriting superstitions of old. Reason itself is revered, society sacralised, morality humanised. New freedoms and new oppressions arise, along with new systems of social organization, and new resistances to them. The “West” becomes self-conscious in ways both monstrous and glorious, routinized and ingenious, scientific and poetical. My

It is late in the long day and we find ourselves in the middle of a broad stream. Between us and the farther shore, the expanse of water widens, and the bottom that seemed as shallow as a footstep recedes to a depth we cannot touch. We have traveled far in one direction, but now the river cuts another, and we are at every moment in this crossing

task was to draw us into the most fundamental contradictions of the “long 19th century,” to look behind the extremes of the “isms” of the era to the common aspiration for rationalized change: liberalism, utilitarianism, positivism, early feminism, capitalism, communism, conservatism, colonialism, racism, anti-racism, progressivism, scientism, romanticism, impressionism, expressionism, even nihilism—all in their various ways reach for authenticity and freedom. From the austere rationality of Robespierre to the anti-rationalism of the Underground Man, the diverse achievements and pitfalls of Section V resist reduction to simple themes or outcomes, though the energy of the time continues to disrupt and inspire.

borne downstream. The only way across is through.

This is the problem posed to us of the contemporary world in section VI: what seemed familiar and accessible is stranger than imagined. It may be tempting to read this section, which finds “the West” reimagining older narratives of human progress and perfectibility amid a litany of tragedies, including two World Wars, the Holocaust, and the ongoing violence of colonialism, as an immersion into chaos. To some, no doubt, section VI will appear as the cartography of a world that has stopped making sense. To others, though, the collapse of earlier “grand narratives” clears space for alternative stories and a different kind of sense. In a few short weeks, we will explore the tensions between these two visions of modernity as they appear in the representational strate gies of literary modernism, the rise of Freudian psychoanalysis, the growing fissures between the “continental” and “analytic” schools of philosophy, reflections on the horrors of the Holocaust and the Second World War, the development of anti- and post-colonial literatures and theory, the legacies of second-wave and

later intersectional feminisms, the development of new styles in the visual arts as well as new art forms such as cinema, the emergence of environmentalism, the civil rights movement in the United States, and Indigenous demands for the Canadian government to recognize its complicity in the violence of the colonial project. By the year’s end, having gotten across by going through, we will have gained—among other things—the critical distance necessary to begin making sense of a world whose very nearness makes it hard to know.

ANIL PINTO-GFROERER (FYP 2020–22)

This afternoon I received a message from a friend saying that he was currently on a bus from Poland to Berlin — upon reading his message my mind immediately filled with places I wanted him to see and visit, burgers he should eat, streets he should walk down, parks he should sit it. My enthusiasm is grounded, I think, in a profound sense of respect and gratitude to the city which so generously held my restless and seeking self for that month two years ago.

Berlin was not an easy love for me, I was not instantaneously enthralled with her beauty and charm, she was fast and broken and grey. I remember the first moment I stepped out of the U-Bahn station and into the dead centre of Rosenthaler Platz. I was immediately surrounded by hostels and restaurants somehow unable in the fog of jet lag to locate which was mine. I finally located the Circus Hostel tucked behind a pharmacy on a beautiful tree lined street just off the Platz and stumbled through the doors and up to my room where I was greeted by faces I knew well from King’s. It was a strange but very welcome sensation to be greeted by this motley crew of friends from what I had already begun to consider my home after two years in University. We joked and hugged and gleefully recounted the events of the brief time we had spent apart and then inevitably all found our way to our bunks and were struck by some unbeatable wave of fatigue.

The next day we arose early, elated to discover that we were really and truly in each-other’s company, and made our way down to the café below. I can still keenly remember the warmth of the Brötchen

on offer, the cool and bright sensation of stepping out onto the patio to see anew the Platz I had been so befuddled by. It is always humbling to perceive these things in the light of day, because when I looked, I saw that the station exit was in fact mere steps away from the door of the Circus.

That first afternoon we met in what would be our classroom, the dimly lit bar below the hostel — a place where I would hear words and have conversations which are burned into my mind and which have profoundly shaped the way in which I engage with the world.

Part of my reason for attending this program, which is important to acknowledge, was my desire to grapple with the reality of what it means to have German heritage. I can claim no personal suffering or any virtue in this regard, this act of engagement with my family’s past (which this program allowed for) was fundamentally made possible through the interactions which I had with friends and the people who we encountered on our journey. Despite having taken some German history and CSP classes that year which talked at length about the mangled past of Berlin, it was impossible to understand the gravity of the suffering which the city bore from a distance. And although it was easier to feel this weight staying there, even in those places where the marks of that suffering were apparent and present as gaping wounds, the pain was too great to wholly comprehend.

These gaping wounds were made evident that very first day when we emerged from our basement cavern to walk together through an old Jewish neighbourhood in Berlin’s Mitte, where we encountered budding lilacs, memorials (the poignant Deserted Room in

Koppenplatz), and stones laid to signify collective grief. As you spend more time in Berlin it can become easy to forget where you are, until your foot hits a Stolpersteine (a brick out of place stating the name, and life dates of a victim of the Holocaust who lived where you stand) and your body forces your mind to engage. I think in many ways that was what Berlin offered me most generously, the demand of her embodied presence to engage with her broken and fragmented self, guided by the caring hands and brilliant minds of those who surrounded me.

When walking in the company of friends and mentors in this way, one can learn a place and in this process of learning can foster attention. Attention, which as stated in Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird is in many ways synonymous with the act of loving. To be in this place is to learn to acknowledge its fragmentation and in this attention to brokenness it is quite possible to find yourself in a position of love. ❧

Heather Page:

To be honest, the initial idea of having a cat in a shared dorm seemed hard to manage, but after a whole semester it’s proven to be much easier and more worthwhile than I would have ever thought. Sure there’s less space, the smell of the litter box and being woken up in the middle of the night, but I think without this cat I’d feel so much less at home in residence because I grew up with cats and never want to stop owning them. She’s a rescue that my roommate and I adopted for the dorm, so it was so lovely to get to know both a person and a cat during my introduction to residence and university life. Unexpectedly, she is super playful and affectionate despite being an older cat and there’s never been a dull moment because she’s such a diva. Despite not being a trained emotional support animal, she’s extremely in tune with human emotions, which cats are less recognized for but apparently so good at! I’m convinced that I’d be way more stressed without her. Overall I’ve loved getting to have a pet in residence and the pros far outweigh the cons!

Taidgh Srivastava and Roan Wilder:

My roommate and I recently made the big decision to adopt a….fish! A betta fish to be precise. We knew something was missing from our room and our little baby G Force filled that void. We decided to take the big leap and provide him with a loving home as we wanted to experience the joys of parenthood and make our house a home with the love that we knew our lil G would provide us. Our journey originally began with this sense of longing for something more, after long nights of discussing what would be the right fit for us and what would abide by Alex Hall Residence guidelines, we found that pets must be non-walking aquatic animals thus our original idea of adopting a lobster or crab was no longer a go :(, so a fish was the only option, and what a great option it was! Our baby G-force is a silly, introverted young fella who loves late night talks and has a big appetite! He tends to hide away in the

plants of his tank during the day but during the night he loves to eat and swim around. G Force is named after the 2009 cinematic masterpiece made by Disney featuring Nick Cage and Steve Buscemi of the same name. We were inspired by the bravery and virtues that each of the highly trained FBI agent guinea pigs have in the film and wanted our own little ball of sunshine to fully embody these virtues that we believe will make the world a better place. When he is old enough we want him to follow in his parents footsteps and attend Kings for FYP as we full heartedly believe that he has what it takes to change the world and that FYP is the first step in doing so.

Lil G has been a great addition to our room and has truly made this house a home. P.S. King’s Alum and Students; be on the lookout for King’s first non-walking aquatic student, he’s very excited to meet you!

Normally, at around six in the morning, as the sun starts to enter my bedroom, I can hear scattering on the floor. If this were in my old house, I would probably be a little bit frightened, as this was a sure sign that mice had broken into the room. But now, all I can think of is the excitement of waking up to the beautiful brown eyes of my cat, Virgil Living with Vergil (people use Vergil and Virgil interchangeably) has brought a profound importance to life on campus. When I think about the first couple of nights after he arrived, I can explain the experience only in terms of what a father experiences while looking at his newborn child. Except my child is one born of soft fur and can’t seem to understand the world except in terms of amazement at long, string-like objects, and finds the most solace in resting his toasty body against my neck, kneading his paws on my throat, and sucking on my earlobes for some unexplainable reason.

This being said, there is a guilt that comes with him. My roommate sometimes is the victim of Virgil’s morning frenzy, where he latches on and attacks him in a manner I would liken to a swarm of Great Burdocks conjoining with a piece of clothing after a stroll through the woods. Yet, in the end, he is a beautiful and loving creature who expresses something that is all too rare on campus—an infatuation with the daily humdrum of life, expecting no more than the present realities he faces, and for this, I admire him and learn a great sum as well. He is always in the act of creating something within the confines of his narrow existence, not wallowing in the impossibility of leaving on some hypothetical trip to Europe or some great adventure yet unplanned. His adventure is in the pure tactile experience of anything from a towel to my toes (which have been the victim of his nibbles), and for that, whenever I feel as though the world is static, he provides the elasticity.

Bringing my cat, Joey, onto campus was honestly one of the best decisions I’ve made. I was having a hard time adjusting to university life—the new environment, meeting new people, and settling into residence were all incredibly overwhelming. After researching the benefits of having an emotional support animal, I realized that having Joey with me would be a great way to cope. Joey is truly the best cat I could’ve asked for. He’s outgoing, playful, and always excited to meet new people. He especially enjoyed his trip to the NAB and meeting Dr. Brandes!

Of course, there are some challenges to having a cat on campus. I’m not exactly fond of keeping a litter box in my room, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s completely worth it. It’s comforting to think that Joey has been with me during this pivotal period of my life. I can’t wait to look back on FYP and all the adventures we had.

2024–2025

“Sappho’s Garden” (A one-woman folk opera by the Spare Key Collective)

Thursday, September 12, 2024

7:00 pm – KTS Lecture Hall

Neptune Theatre – Gilgamesh & The Man of the Wild

Wednesday, October 2, 2024

7:30 pm – Neptune Theatre, Scotiabank Stage

100 tickets purchased for FYP students.

Hildegard of Bingen & the World of Medieval Chant

Monday, Oct 21, 2024

7:30 pm – King’s College Chapel

Songs & Madrigals of the Renaissance, with Helios Vocal Ensemble

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

7:30 pm – King’s College Chapel

An Evening with Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro

Wednesday, January 22, 2025

7:30 pm – President’s Lodge

The Great Debate: “Be it resolved: That all of the Foundation Year Program can be understood through the concept of the Circle and the Centre.”

Wednesday, February 26, 2025

7:00 pm – Alumni Hall

Eli Diamond, “Prince and the Revolution: A Dionysian Christianity for the 20th Century”

Wednesday, March 26, 2025

7: 30 pm – Alumni Hall

ELISABETH STONES

My role in FYP is pretty behind-the-scenes, and that’s usually where I like to stay, with two-to-four screens full of information to juggle and compare, and always a chance to double-check something before I make any definitive statements. But I’ve got this other gig, too…

Singing Mozart is an unmitigated pleasure, and I had the extraordinary good fortune to be asked to sing in the President’s Lodge, for this year’s FYP class. You could not dream up a more supportive crowd than the FYPers, but still I was terrified! I had been singing since forever, and performing solos since my King’s Chapel Choir days, but opera – with its added dimension of acting

– still felt like something “other people” do. Surely everyone would see what a fraud I was! Hey everybody, Oratorio Girl thinks she can sing a flirty duet!

In the weeks leading up to the Marriage of Figaro Night FYP event, I was singing nonstop. I knew the best thing I could do was plug that music deep inside so that when the moment came to stand in front of everyone and actually make the noises, my body would take over while my brain panicked. This meant I sang while I did the dishes, folded laundry, biked to and from work, and shoveled snow. My two-year-old, Felix, took a dim view to this method, and on one occasion he tenderly cradled my face in his sticky hands, and implored, “Mummy, STOP.”

The evening started with the famous opening duet from Figaro . J.P. Decosse was playing the titular baritone barber, and I, his fiancé Susanna. A duet is an act of trust, and I was desperate not to let the veteran J.P. down. As he wove his way through the audience, measuring, counting, at ease in character, I gripped my iPad, where my sheet music glowed up at me. I knew I didn’t want to keep my eyes on the notes – that’s why I had practiced so much at the expense of my family’s peace – but I felt very unprepared to

actually do the thing. Maybe we should have scheduled six or seven more rehearsals? Was it too late to ask Neil to sing this part?

Eek, it was time! Somehow, I caught my cue and came in. My brain screamed: Try to get a deep enough breath. Is it drier in here than normal? Remember, Susanna is very excited about her hat. Show them the hat! Yikes, were those the right words? Don’t think about it, keep moving… BREATHE! Don’t miss your chance to say “cappellino;” is there a better word in the world? Are you breathing?

I lost my spot on the page. My mouth made Italianesque noises in rhythm, but I knew I was barely keeping up. It was time to put the iPad down, and pretend I was a real Opera Girl. The worst I could do was catastrophically fail.

I offered my best reflection of J.P.’s sparkle and accepted his invitation into the whirlwind. And, somehow, every word was there, every note right in front of me, after all. ❧

KATE LAWSON

Jane Austen Live! The Halifax Humanities Marathon takes on Northanger Abbey

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.”

— Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey

I must begin with a confession that mere months ago, I myself may have been this intolerably stupid person when it came to reading the beloved author, Jane Austen. For numerous reasons, I could never find a way into Austen’s works. Part of Austen’s genius, her ability to incite either our distain or devotion for her characters was often what led me to throw down her novels in exasperation. I admit this rather sheepishly with the hindsight of my experience reading Northanger Abbey with Halifax Humanities’ incredible annual fundraiser this past November.

A marathon reading of a classic work of literature is the biggest annual fundraising event for the Halifax Humanities Society. Teams of readers take on the responsibility of performing a section of the text and collecting donations in support of their participation. By the end of the event, the whole text has been read from start to finish.

The Halifax Humanities Society, under the direction of Amy Bird, is a non-profit organization dedicated to providing educational opportunities and engagement with the arts to those who would otherwise lack such access. Students include, but are not limited to, those who live on assistance, disability, pension, or those who face other economic, physical, and social challenges to educational advancement and community inclusion. Halifax Humanities 101 is based loosely on the curriculum developed in King’s Foundation Year Program.

As a researcher in the field of philosophy, I focus predominately on the 20th century philosopher Simone Weil, and I believe, along with Weil, that the humanities should belong to everyone, not just those who attend liberal arts universities. Weil taught texts like the Upanishads , The Iliad , and Antigone to rural children, factory workers, and those marginalized by society. The consolation of philosophy, literature, and history has been immense in my own life, and I would go so far as to argue that these texts constitute a substantial part of what Weil refers to as the “needs of the soul” in her final book The Need for Roots . Halifax Humanities recognizes this richness and promotes democratizing that consolation.

And so, this past November, alongside my fellow FYP Tutors, Daniel Brandes, Veronica Curran, Maria Euchner, and Samuel Gillis Hogan, we read Chapters 15 and 16 of Austen’s Northanger Abbey for the 2024 Jane Austen Live! Marathon. I was cast as the deliciously materialistic Isabella, truly an embarrassment of riches for any performer.

Reading texts aloud has an almost miraculous effect, in my opinion, particularly with other lovers of literature and in the name of a cause so worthy. By joining together to explore the rich characters of the novel, finding the humor, heart ache, and even the underlying sociopolitical commentary, something opened up and I

began to finally understand Austen. In her book on the Human Condition , the philosopher Hannah Arendt claims that theatre is the political art par excellence. Reading out loud together, sharing in the surprises and possibilities of the life of the mind, reminded me of the necessity of sharing in the humanities as a step toward a society that thinks critically and supports an open dialogue. The marvelous surprise for me from this particular instance of communal thought is my deepening appreciation for Jane Austen and her tremendous writing (an appreciation further assisted by the superb FYP lectures on Emma from Dr. Kait Pinder). This newfound admiration for Austen emphasizes the ability to discover texts anew, to change one’s mind, to never cease in the pursuit of understanding, and to share that exploration with others whenever possible. Coincidentally, one excellent way to do this is by supporting the Halifax Humanities or perhaps next year, forming your own team and joining in the next literary marathon. ❧

—Intolerably Stupid No More (at least in regard to Austen), Dr. Kate Lawson, FYP Tutor. For more: halifaxhumanitiessociety.ca

REVIEW BY AUBREE FIELD (FYP 2024–25)

Getting the opportunity to see the ancient Mesopotamian text of Gilgamesh live within a current story brought me into a completely new way of thinking about the text. I had previously assumed our society rewarded ‘great nations’ for their ability to last in time. Yet seeing the story realized into a play I got a chance to interact with the geography of the story and what ancient Mesopotamia is sitting on today. This surprised me how the most ancient civilization we know of is now in conflict caused by the effects of colonialism. It introduced the thought process of not only being able to appreciate a great civilization, but also to study how it fell, why it fell, and what it gave way to. The artistry of this performance was by far my favourite part of the experience. The stage was outfitted with only a piano, some chairs and one main table. Yet it became the coffee shop, the place back home, and the audition room

with just a turn in lighting. The physicality that was able to be upheld by the two main actors was astonishing. They were tasked to play two or more roles each, not every one of them human, and successfully they illustrated the different lives with truthful body language. The live orchestra also came from the back out into the front of the stage becoming interchangeable characters in the story which was fascinating. I believe stories like these are so important because where they take place often only lives in history books and becomes inaccessible. Using the story of two men from different parts of the world not only portrayed the relationship of these societies today but how the world became this way. ❧

CHRISTOPHER SNOOK (forthcoming, Commonweal 2025)

It couldn’t mean anything in the end all of us disheveled and lined up disorderly singing O Canada to the muzak pumped through the PA system otherwise reserved for trouble trouble trouble then silence and Mrs. S intoning the prayer

And we said something about our hollow fathers (they were hungry even them)

And Jesus lived in Calgary with half the Island beautiful in black tea sartorial tar sand streaks of wet charcoal and the boys in their boats

And who wanted anything to do with forgiveness if it meant not getting Timmy after school?

What could it mean O what could it mean for kids on the Eastern shore forty years ago, the Lord’s Prayer before arithmetic? Except now daily daily daily the stone-filled stomach and what bread?

MARY LU REDDEN