HINGE CSS

We the editors recognise that the work and scholarship at the University of King’s College, including the activities of the Contemporary Studies Society and the publication of Hinge, takes place in K’jipuktuk, located in Eskikekwa’kik, the third district of the Mi’kma’ki. This is the unceded and ancestral territory of the Mi’kmaq people. The primary language of this journal is English, a language of historic and continuing colonialism and oppression. These lands are governed under the Treaties of Peace and Friendship, which promised to uphold Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship on this land, never dealt with surrender of the land to settlers, and did not address the issue of land possession in any significant way. The promises of the treaties were continually broken by settlers, who carried out a violent, genocidal agenda against the Mi'kmaq and all the nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

For more information on these treaties visit https://www.migmawei.ca/negotiations/migmaqtreatyrights/

These injustices are not limited to historical events. Indigenous lands and knowledge continue to be appropriated for political and economic gain. As people dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge, it is our responsibility to recognise the impacts of colonialism and strive for a future of shared understanding between all peoples. Our intellectual pursuits at King's and beyond must be guided by the principle of Two-Eyed Seeing, which Mi'kmaq elder Albert Marshall refers to as “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and learning to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing... and, most importantly, using both of these eyes together for the benefit of all.” May our curiosity and learning guide us toward a better and more just world.

HINGE

A Journal of Contemporary Studies Volume XXIX

Editor in chief: Morag Brown Assistant Editors:

Callie Jurmain, Bonnie Lennox, Noah Poitras, Isabelle Wong

Copyright remains with the author in all cases.

Cover art by Jack Mastrianni

Cross-stitch featuring the album cover of American rock band Phish’s 1992 album A Picture of Nectar, and cross-stitch reproduction of a still from Star Trek, S3E22 “The Cloud Minders.”

Printed in Kjipuktuk (Halifax), Nova Scotia, 2024

Foreword

Light and Enlightenment in the Parable of the Madman

Kailen Crosson

Gods, Power, and Erasure: A Comparative Analysis of European Presence in Africa

Rowan Helmer

The Multiplicity of Perspective in Holocaust Memorials

Daniel Konopelski

Lucky for You, I’m a Vampire: Saltburn’s Queer Abjection

Evan Lorant

Visibility and Voids in Berlin’s Memorial Landscape: How Germany Marks a Self-inflicted Absence

Olivia MacDonald

Problematizing the Apocalypse: Analyzing Climate Change

Narratives

Noah Miko

Harriet

Foreword

This edition of HINGE aims to weave a written tapestry depicting the learning and writing that took place in the Contemporary Studies Program (CSP) at King’s in the 2023/2024 academic year. By stitching together papers of different styles and on diverse topics ranging geographically from Nigeria to Berlin, and temporally from Nietzsche to Saltburn, the XXIX edition of HINGE aims to faithfully represent the scope and depth of the creativity and criticism fostered by the CSP.

Over the 2023/2024 academic year, the Contemporary Studies Society (CSS) prioritised reviving the sense of community among CSP students that has been disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. We were thrilled to watch our CSP cohorts become more tight-knit through social events and study sessions, and we hope to continue this project of building social and academic community. We believe it is essential to facilitate the sharing and threadingtogether of ideas that makes excellent CSP papers–like those in this journal–possible.

Thank you sincerely to everyone who supported the CSS this year,

The

CSS Executive Board

Morag

Brown, Callie Jurmain, Bonnie Lennox, Noah Poitras, Isabelle Wong

Light and Enlightenment in the Parable of the Madman

Kailen Crosson

In The Parable of the Madman, Nietzsche uses metaphors of light and illumination to inform his philosophical ideas. In particular, he focuses on the imagery of a lantern carried by the Madman, contrasting it with other sources of light to express his ideas about other philosophies of his time. The present discussion focuses on Nietzsche’s use of the lantern and how it is contrasted with the light of the sun. In particular, this analysis focuses on the supremacy of self-formed ideas. Nietzsche uses natural light to represent enlightenment ideals of philosophy, science, and eternal truths, while simultaneously demonstrating how a reliance on eternal ideas is stifling of the true human spirit. Furthermore, this analysis focuses specifically on the symbolic significance of the Madman’s lantern, insofar as it is representative of Nietzsche’s attitude concerning the valuation of ideas. Nietzsche uses light in The Parable of the Madman as a means of defining his view on the correct way of forming and maintaining ideas.

The Parable of the Madman opens with a description of the eponymous Madman who, lighting a lantern “in the bright morning hours”, carries it into a market square full of atheists while declaring God to be dead (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). While the act of carrying a lit lantern in the light of day may seem to be evidence of madness, it underlines one of Nietzsche’s key beliefs about the reception of the death of God within society. When the Madman tells the atheists in the marketplace they laugh at him, mocking his proclamation as they have already ceased to believe in a God (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). The bright morning light in the marketplace seems to further this point. They believe God to be non-existent and that “human maturity requires that we learn to live in the clear, invigorating light of that knowledge,” and as such are acting as representatives of the enlightened era (Mullhall, 2009, p.21). The atheists assume that since he brings a lantern to light a bright marketplace, the Madman is trying to enlighten an already enlightened group of people. Nietzsche intends this group to represent the philosophical and scientific thinkers of his own era, whom he believes to possess an unhealthy “Will to Truth”. Nietzsche defines the Will to Truth as a life lived “according to a prefixed ideal, against which the person is judged and valued,” which seeks to only understand life as it is defined by a set of truths (Huskinson, 2009, p.6). These fixed truths are ‘eternal’ insofar as they are considered factual, and not subjected to continual scrutiny. Through the practice of rational thought and enlightenment ideals, scholars of Nietzsche’s time embodied this Will to Truth’ by seeking to make the world knowable through both philosophical and scientific study. While they may not concern themselves with religious rites in particular, Nietzsche sees their ‘faith’ to be their obsession with knowledge and finding absolute truth (Nietzsche, 2003, p. 34). Therefore, Nietzsche interprets the scholars to still believe in God insofar as they believe in the existence of preconceived truths, albeit in the form of scientific and metaphysical ideas rather than religious principles. However, Nietzsche’s death of God is the death of these scientific and philosophical ideas as well. He is claiming that there is nothing that

can actually be known as an unchanging truth, and that the truths sought by the academics of his time are, at their core, distractions from achieving a full understanding of one’s own potential. The atheists in the marketplace embody this concept when they mock the Madman for announcing God’s Death, falsely believing that God is a fairytale entity whom they have already outgrown (Mullhall, 2009, p.23). As such, they believe themselves to be enlightened because they fail to understand that the Madman is not attempting to warn them of the absence of God, but rather wishes to impress upon them the absence of all empirical truths, including those which the atheists believe themselves to be illuminated by. The Madman is positing that “the bright morning of enlightenment atheism is, in fact, dead light,” or a false idea of truth that the atheists do not yet fully comprehend (Mulhall, 2009, p.28). Thus, the Madman is not mad for carrying the lantern, but rather prepared for the darkness that is the absence of eternal truths.

If the Death of God implies the absence of any eternal truths, what are the remaining implications in Nietzsche’s assessment of human value systems? An analysis of the many metaphors that Nietzsche employs to express this amputation, like his use of imagery detailing the cosmos and the sun, provides helpful references to his view on the matter. During his parable, the Madman beseeches the atheists to explain “what were we doing when we unchained the earth from its sun?” (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). Here, he is referring to the Death of God insofar as it is the act of ‘untethering’ from the ideas that society has been traditionally based upon. Humans and society, represented by the earth, have come untethered from the idea of any eternal source. The very nature of the sun makes it possible to associate with the idea of eternal truths and values because of its own eternal qualities. Firstly, the sun is in itself considered an eternal source of light and is a constant of human life. Recalling the bright morning enjoyed by the atheists, we can even consider the light of the sun to be directly symbolic of enlightenment era ideals (Mulhall, 2009, p.28). Consider the twenty-four-hour structure of the day where all aspects of life, from prayer times to workdays, are centered around the presence or absence of the sun’s light. We believe a day to be a day because of the average length of the sun’s presence. Likewise, eternal truths are “employed as a means of coercing uniformity of belief” by implying that there are true and knowable facts about life and the universe (Gemes, 1992, p.51). The idea of lacking eternal truths is comparable to the idea of lacking the sun, as both consist of losing something that had previously been the total measure of existence. This is further supported in the text when the Madman described the earth as actively moving away from the sun, and not just simply becoming disconnected from it (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). When faced with a lack of eternal values, which comes as the result of the death of God, one is faced with the choice of active or passive nihilism. One can choose to accept the death of God passively and mournfully, or actively take joy in absolute freedom (Li, 2016, p.308). Nietzsche believes that the Death of God, and therefore the elimination of eternal truths, is an active process and not a passive happening. Earth should not just allow for the passive crumbling of its tethers to the sun, but actively distance itself from it. Nietzsche employs similar imagery in Beyond Good and Evil, where he claims “as long as you still feel the stars as something ‘over you’, you still will lack the eye of the man

of knowledge” (Nietzsche, 2003, p.91). Here, as he does in The Parable of the Madman, Nietzsche is using the idea of eternal, cosmic light to symbolize the idea of eternal truths and values. When one realizes that the cosmic ‘light of the stars’ is not over them, they gain the knowledge to realize that they are their own highest goal, and actively partake in the creation of their own truths. By engaging with this idea and rejecting the eternal light of the sun, the Madman is free from the Will to Truth to which the atheists fall victim. The Madman understands that to known as an unchanging truth, and that the truths sought by the academics of his time are, at their core, distractions from achieving a full understanding of one’s own potential. The atheists in the marketplace embody this concept when they mock the Madman for announcing God’s Death, falsely believing that God is a fairytale entity whom they have already outgrown (Mullhall, 2009, p.23). As such, they believe themselves to be enlightened because they fail to understand that the Madman is not attempting to warn them of the absence of God, but rather wishes to impress upon them the absence of all empirical truths, including those which the atheists believe themselves to be illuminated by. The Madman is positing that “the bright morning of enlightenment atheism is, in fact, dead light,” or a false idea of truth that the atheists do not yet fully comprehend (Mulhall, 2009, p.28). Thus, the Madman is not mad for carrying the lantern, but rather prepared for the darkness that is the absence of eternal truths.

If the Death of God implies the absence of any eternal truths, what are the remaining implications in Nietzsche’s assessment of human value systems? An analysis of the many metaphors that Nietzsche employs to express this amputation, like his use of imagery detailing the cosmos and the sun, provides helpful references to his view on the matter. During his parable, the Madman beseeches the atheists to explain “what were we doing when we unchained the earth from its sun?” (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). Here, he is referring to the Death of God insofar as it is the act of ‘untethering’ from the ideas that society has been traditionally based upon. Humans and society, represented by the earth, have come untethered from the idea of any eternal source. The very nature of the sun makes it possible to associate with the idea of eternal truths and values because of its own eternal qualities. Firstly, the sun is in itself considered an eternal source of light and is a constant of human life. Recalling the bright morning enjoyed by the atheists, we can even consider the light of the sun to be directly symbolic of enlightenment era ideals (Mulhall, 2009, p.28). Consider the twenty-four-hour structure of the day where all aspects of life, from prayer times to workdays, are centered around the presence or absence of the sun’s light. We believe a day to be a day because of the average length of the sun’s presence. Likewise, eternal truths are “employed as a means of coercing uniformity of belief” by implying that there are true and knowable facts about life and the universe (Gemes, 1992, p.51). The idea of lacking eternal truths is comparable to the idea of lacking the sun, as both consist of losing something that had previously been the total measure of existence. This is further supported in the text when the Madman described the earth as actively moving away from the sun, and not just simply becoming disconnected from it (Nietzsche, 1974, p.181). When faced with a lack of eternal values, which comes as the result of the death of God, one is faced with the choice of

active or passive nihilism. One can choose to accept the death of God passively and mournfully, or actively take joy in absolute freedom (Li, 2016, p.308). Nietzsche believes that the Death of God, and therefore the elimination of eternal truths, is an active process and not a passive happening. Earth should not just allow for the passive crumbling of its tethers to the sun, but actively distance itself from it. Nietzsche employs similar imagery in Beyond Good and Evil, where he claims “as long as you still feel the stars as something ‘over you’, you still will lack the eye of the man of knowledge” (Nietzsche, 2003, p.91). Here, as he does in The Parable of the Madman, Nietzsche is using the idea of eternal, cosmic light to symbolize the idea of eternal truths and values. When one realizes that the cosmic ‘light of the stars’ is not over them, they gain the knowledge to realize that they are their own highest goal, and actively partake in the creation of their own truths. By engaging with this idea and rejecting the eternal light of the sun, the Madman is free from the Will to Truth to which the atheists fall victim. The Madman understands that to untether oneself from the sun is to no longer view its light as an eternal and all-guiding force, but instead seek out and create one’s own source of light. With the elimination of both the daylight of the marketplace and the eternal light of the sun and cosmos, Nietzsche’s Madman is left holding his lantern, the only source of illumination (Nietzsche, 1974, p.182). This object is the key to Nietzsche’s parable, revealing the only source of actual value after having abandoned both enlightenment values and eternal truths. This comes in the form of a lantern’s one distinguishing trait that separates its light from that of the dawn or the cosmos: a lantern must be lit. When Nietzsche insists that one must be active in the Death of God he does not simply mean that one must reject eternal values. When faced with the end of eternal values, one must “[face] the reality of the collapse of faith, but [also have] the courage to live with a healthy attitude towards life” by affirming it, and creating one’s own set of ideals (Li, 2016, p.308). A lantern is representative of this idea insofar as one must make the active choice to light a lantern and receive its light – one cannot passively receive a lantern’s light the same way one passively receives sunlight. This concept is further affirmed by the Madman when, growing frustrated in the atheist’s lack of understanding, the Madman smashes his lantern to pieces upon the ground (Nietzsche, 1974, p.182). He is not only free to light the lantern as he wishes, but also to destroy that same light. This idea of destruction and creation is not only an embodiment of the active nihilism that Nietzsche encourages, through which one creates values for themselves, but also an understanding that not even created values can be eternal (Huskinson, 2009, p.55). By fully unpacking this concept, the Madman does not just reject the idea of eternal values, but becomes their antithesis by embodying the concept of Will to Power. The cycle of creation and destruction allows one to overcome the Will to Truth by “annihilating the world of being” and transform it into a world of cyclical and consistent becoming (Nietzsche, 2017, 341). The Madman does not just announce the death of all eternal truths, but demonstrates it. He lights his lantern and creates values, only to shatter them and begin anew when they are no longer of service to him. Through his use of both natural and man-made light in The Parable of the Madman, Nietzsche expresses his understanding of the Death of God through the rejection of

eternal truths. Additionally, the lantern is representative of the ability to practice Will to Power by igniting new ideas and values in oneself, while still having the ability to reassess and discard them if appropriate. Through the exploration of light in both The Parable of the Madman and other works, Nietzsche makes clear what he believes to be true illumination, and what he believes to be simply a trick of the light.

References

Gemes, K. 1992. 'Nietzsche’s critique of truth,' Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 52(1), p. 47. https://doi.org/10.2307/2107743.

Huskinson, L. 2009. The SPCK introduction to Nietzsche. London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: SPCK publishing.

Li, G. 2016. 'Nietzsche’s Nihilism,' Frontiers of Philosophy in China, 11(2), pp. 298–319. Mulhall, S. 2009. Philosophical myths of the fall, Princeton University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400826650

Nietzsche, F. 2017. [1901] The Will to Power. Translated by K. Hill. London, England. Penguin Classics.

Nietzsche, F. 2003. [1886]. Beyond Good and Evil. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. London, England. Penguin Classics.

Nietzsche, F. 1974. [1882/1887]. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kauffmann. New York, USA. Vintage Publishing. pp. 181-182.

Gods, Power, and Erasure: A Comparative Analysis of European Presence in Africa

Rowan Helmer

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart both deal with the topic of European colonisation of Africa. In Heart of Darkness, Charles Marlow searches for proof of European virtue, only to find that it has been completely overtaken by violence. The life and death of Kurtz represent the breakdown of European values through the process of colonialism. In Things Fall Apart, Okonkwo tries to maintain his culture and traditions in the face of Christian missionaries. Okonkwo’s life and death represent a struggle to maintain one’s culture and cultural values in the face of colonialism. Ultimately, his death shows how colonial Europe writes over the cultures of the colonised. While Kurtz and Okonkwo share a hunger for power, they represent fundamentally different positions within social hierarchy. This is defined by their positions as either colonisers or colonised. While drawing on Achebe’s “An Image of Africa”, this paper explores how Kurtz and Okonkwo reveal the true nature of European colonisation and expose Europe as the true “heart of darkness”.

Throughout Heart of Darkness, Marlow is afraid of Congolese autonomy and humanity. European expansion and white supremacy rely on a dehumanising understanding of colonised peoples; seeing cultures as other, and thus, less than, allows supremacists to justify their domination. This is demonstrated by the dehumanising language he uses to describe the Congolese. Marlow describes the Congo men as having “faces like grotesque masks” (Conrad 16). Marlow wants to see Africa as a simple “heart of darkness”, so that he can justify European occupation and violence there. Despite his continued racism, Marlow eventually realises the humanity of the Congolese as he travels; “The men were – No, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it – this suspicion of their not being inhuman” (Conrad 44). As Chinua Achebe remarks in “An Image of Africa”, “What actually worries Conrad is the lurking hint of kinship, of common ancestry” (783). Through Marlow, Conrad shows the deep extent of his dehumanising racism. The idea that the Congolese people may be similar to the Europeans frightens Marlow, as it means that he now has to reckon with the fact that his Company is taking advantage of and erasing the lives of real human beings like him. This idea is fully realised when Marlow meets Kurtz.

Despite representing the worst of English occupation, Kurtz is far from the typical englishman. As the Russian tells Marlow, “You can’t judge Mr. Kurtz as an ordinary man” (Conrad 70). Kurtz’s violent nature represents the crumbling of humanity within England due to violent and exploitative attitudes towards the rest of the world. However, before Marlow meets him, he has hope that Kurtz is a great man, as that is how he is talked about in the company. Marlow’s last hope that England is not a dark place lies within Kurtz. Kurtz represents the “flicker” of European humanity that Marlow is desperately searching for within the Congo (Conrad 6). Marlow discovers, however, that Kurtz is a maniacal ruler.

We can understand Kurtz’s unlimited power as a representation of European colonisation of the Congo; says Marlow, “All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz” (Conrad 61). He suggests that Kurtz is a product of European attitudes, beliefs and practices, thus representing the true evils of European colonialism. Marlow hopes that Kurtz will show him Europe’s goodness, however, in reality, Kurtz represents the furthest reaches of European colonial violence. His practices reflect those of the Company but are even more violent and disparaging. He sees himself as a deity and, due to his position in English society, is able to abuse English power over the Congo. Being backed by the Company means he has tools at his disposal to exploit the Congolese. Kurtz represents a complete breakdown of European values. European presence in the Congo was validated as it was made out to be an enlightening mission, as was Kurtz’s. Kurtz’s violence contradicts this claim. The power he wields over the Congolese represents the power that Europe holds over the countries it colonised.

By doing his job, Kurtz shows Marlow the truth about colonialism. Among Kurtz’s responsibilities within the Company is the task of writing a report on the “Suppression of Savage Customs” (Conrad 62). This is presented in an educational and enlightening manner. At first, it seems that Kurtz has strayed from this task by prioritizing his own authority and domination over “enlightening” the Congolese. We discover, however, that his responsibility has been killing the Congolese; scrawled at the bottom of the pamphlet is the objective: “Exterminate all the brutes!” (Conrad 62). This doctrine represents the true purpose of the colonial project. Under the guise of education and enlightenment, Europe seeks to exploit Africa and exterminate its cultures.

This realisation comes to full fruition with Kurtz’s death. Kurtz’s last words are “The horror! The horror!” (Conrad 86). Here he rebukes his own acts, therefore rebuking the colonial project. When Kurtz is revealed as a violent tyrant, he dies. With him dies any hope that Marlow may have had of Europe’s salvation. It is now clear that Europe is “one of the dark places of the earth” (Conrad 5).

Heart of Darkness ends where it began - in London and in darkness. The first time Marlow speaks in the novel he says, “And this also, has been one of the dark places of the earth” (Conrad 5), referring to Europe. Marlow’s use of the past tense here shows his view that Europe has been, but is no longer, in darkness. Marlow brings this assumption with him into Africa, and it is the belief that carries him through his journey. However, as he continues, this assumption crumbles. He slowly realises that there is, in fact, humanity in Africa and that European colonialism is not guided by enlightenment, but extermination. Marlow originally believed that London had escaped the darkness because they found humanity, life, and culture. But again, as shown above, Marlow later realises that Africa is not this dark place. It is a place of culture, life, and language, even if he does not want to admit it. The book begins and ends in London, as a point of comparison to Africa. In the end, Marlow seems to have changed his mind, stating that the Thames leads into the “heart of an immense darkness” (Conrad 96). Rather than stating that England was once a dark place, Marlow now suggests that the darkness of Africa comes directly from the Thames in London. The darkness is brought from Europe into Africa, ostensibly through practices of colonisation.

One major drawback of Heart of Darkness is Conrad’s failure to evaluate the impacts of colonialism on anybody except European colonisers. In “An Image of Africa”, Achebe states, “Travellers with closed minds can tell us little except about themselves” (791). This can be directly related to Marlow. Kurtz has shown him the true nature of the colonial project of the Company, and yet Marlow is more concerned with how this impacts England than how it affects the Congolese. He realises that England’s colonialism makes it “one of the dark places of the earth” (Conrad 5), but fails to consider how this impacts the colonised people. Marlow is more concerned about the breakdown of his own society than the destruction of that of the Congolese. Achebe critiques this and asks the reader to imagine how much richer Heart of Darkness would be if it fully realised the complexity of the Congolese people or any colonised people. He asks the reader to imagine:

...the abundant testimony about Conrad's savages which we could gather if we were so inclined from other sources and which might lead us to think that these people must have had other occupations besides merging into the evil forest or materializing out of it simply to plague Marlow and his dispirited band. (Achebe “An Image of Africa” 791)

Achebe suggests that to truly understand the colonial project's impact on Conrad’s so-called “savages”, one must turn to literature which explores the impact of colonisation on the colonised. Specifically, this literature must allow for the colonised to speak for themselves. To fully evaluate the truth of European colonisation which Kurtz unveils, we must now turn to Things Fall Apart. While Kurtz demonstrates the truth of European colonialism and what it means for Europe, Okonkwo shows us how it affects the colonised. Things Fall Apart can thus be read as a response to Heart of Darkness.

We might find similarities between Okonkwo and Kurtz, but their political positioning makes them fundamentally different. While both men are power hungry and violent, their powers are different in that one is limited and one is not. Okonkwo’s violence and power are limited to his household. Regarding this power, Achebe explains, “Okonkwo ruled his household with a heavy hand. His wives [...] lived in perpetual fear of his fiery temper, and so did his little children” (Things Fall Apart, 13). Okonkwo is limited by his society, which he has immense respect for. He has the same desire to be seen as strong and powerful as Kurtz does, but his reputation is hindered by the norms of his society. While the two men are respected in their communities, Kurtz’s power extends much farther than Okonkwo’s does.

Okonkwo’s actions are generally in line with his society’s beliefs and traditions. For example, Okonkwo kills his adopted son, Ikemefuna (Things Fall Apart 61). We might read this as abuse of his power, in line with Kurtz’s violence, but a deeper look reveals striking differences. Okonkwo’s violence, though disturbing, does not result in a breakdown of his societal values in the same way that Kurtz’s does. Okonkwo kills Ikemefuna because he respects the Oracle and his gods. This violence is contained within his family, making it incomparable to Kurtz’s colonial violence and exploitation. By straying from any morals or respect for humanity that he may once have had, Kurtz represents the death of European values and humanity, and the descent into the darkness that comes with violating humanity. Okonkwo’s respect for humanity

and his societal values guide his actions, therefore differentiating him from Kurtz and showing the reader that there is abundant humanity in Africa, which Marlow only shallowly and briefly notices in Heart of Darkness

Okonkwo’s death represents the European rewriting of African history and traditions. As established, Okonkwo is a man who has deep respect for his society, his gods, and the beliefs of his ancestors. Throughout the book, Okonkwo’s beliefs are broken down more and more. When the Christian missionaries come to his community, Okonkwo sees his values and beliefs being destroyed in front of him. This is exemplified when his son Nwoye turns to Christianity, thus “abandon[ing] the gods of one’s father” (Things Fall Apart 152-53). To Okonkwo, this represents his beliefs, traditions and way of life being disrespected and written over by Christianity. Eventually, Okonkwo loses any hope of the continuation of Igbo tradition and life. This realization impacts him so much that he commits suicide (Things Fall Apart 207). This death is out of character for Okonkwo, who is characterised by his pride and would want to die in battle, with honour. The colonisation of Umuofia by Christian missionaries triggers Okonkwo to lose the pride he has in himself and his community. His death represents the shame and dehumanisation he feels due to the Christians’ presence in Umuofia, and because his people are being converted to Christianity. The assistants to the Christian missionaries unceremoniously handle Okonkwo’s body (Things Fall Apart 208), violating his beliefs. He has been broken down so thoroughly that he does not even get to find honour in his death. The intention and the absolute evil of the colonial project is to break down a culture and to write over it which, as stated above, is represented by Kurtz’s occupation in the Congo. This results in not only the disappearance of the history and traditions of the colonised but also the total breakdown of both the colonised and coloniser’s values.

Treating Heart of Darkness and Things Fall Apart as companion novels highlights common themes and interesting contrasts, and can teach us about European colonisation in Africa. From two characters, Kurtz and Okonkwo, we can take away a new vision of the dynamic between the two continents; Europe might be the real “heart of darkness”. Kurtz’s unlimited violence, exploitation, and lust for power convince Marlow that Europe’s self image as a morally righteous continent is shallow and misguided. In “An Image of Africa”, Achebe recommends that we not rely on Conrad’s depictions of Africa and African people without reading his claims in conjunction with those of a colonised society. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart shows us the other side of the European colonial project. Okonkwo’s life and death demonstrate how the erasure and destruction of Igbo traditions and his belief system caused him immense pain. The Christian overtaking of his society leads to his death, which represents the “death” of societies such as the Igbo, after being colonised. Kurtz and Okonkwo come together to expose Europe as being the true heart of darkness that Charles Marlow is looking for.

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. “An Image of Africa.” The Massachusetts Review, vol. 18, no. 4, 1977, pp. 782–94. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25088813. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023. Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Anchor Canada, 2009. Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. Penguin Books, 2007.

The Multiplicity of Perspective in Holocaust Memorials

Daniel Konopelski

The Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings near the Tiergarten in Berlin, Germany offers a substantive case for the memorialization of people persecuted in the Holocaust. The monument provides a striking perspective on the persecution of disabled people, a class which could be overlooked if mixed with another memorial. The blue glass wall on a diagonal represents the disabled victims. Rather than the traditional, well photographed counterparts in Berlin, the monument is separate but in close proximity to the parts of the memorial representing other persecuted people from the operation. Each section tells a piece of the larger story about the mass atrocity through a consideration of the people who were targeted. The placement of the monument itself offers a counterargument against the agglomeration of the different persecuted groups of the Holocaust, to allow perspective in the face of anonymity of mass atrocity. The monument is found in the Berlin Mitte region of the city where the most notable landmarks are set apart from other monuments. This monument, or countermonument, serves to justify the perspective and experiences of people represented as a sovereign group and to commemorate events that directly impacted them while resisting a traditional idea of memorialization.

Architecturally, the memorial is a simple wall of blue-tinted glass that runs perpendicular to the road and Tiergarten to the north and the Berliner Philharmoniker to the south along Tiergartenstraße. The blue pane appears as both a physical and visual obstruction, rising from the flat pavilion on which it sits. The visual obstruction represents the perspective of the disabled, and is a form of visual distortion that evokes their challenges for which they were persecuted.

Two information panels run parallel on both sides of the memorial. They are present to help the audience to contextualize the memorial with Operation T4, which was the process of exterminating people with disabilities or impairments. In this context, the blue pane serves to level the distance between people with disabilities and the audience passing the memorial every day. Much like other monuments in the city, the Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings near the Tiergarten is meant to be stumbled upon by the viewer and act as a means to contemplation amidst the city’s environment. The Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings, while independent, has a continuity with the other monuments in

Fig 1 The Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings (Konopelski)

Berlin’s urban geography. This is exemplified by the proximity to other memorials of persecuted peoples of the holocaust, with the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe and the Memorial to the Homosexuals persecuted under Nazism being within the Tiergarten. Additionally it is located in close proximity to various landmarks in the Berlin Mitte and the as well as the Potsdamer Platz which is a block south of the memorial.

The plethora of interpretations that viewers of the monument may form reflect the multiple perspectives of the persecuted group of people–in this case the disabled. The monument's separation from more recognised preserves a “narrative[,] with other nationalized memories of the Holocaust[,] to identify some unique characteristics of this memory” (Chalmers 151). This method of preserving the group’s narrative prevents the conglomeration of this structure into another monument and the associated loss of awareness of the group affected by mass-atrocity (Chalmers 151). This retrospective analysis of the involvement Germany had in committing the atrocity is a triumph of “the state-sponsored monument's traditional function as selfaggrandizing locus for national memory” (Young 270). Specifically, since “the essential, nearly paralyzing ambiguity of German memory comes as no surprise”, knowing the groups of people deliberately targeted as inferior is crucial (Young 270). Therefore, the act of providing space for a monument that reflects on the question of “who gave their lives in the struggle for national existence” and honours them sovereignly (Young 270) is significant. A success of the “[h]istories of violence or state-mandated hatred can be easily integrated into this narrative so long as one demonstrates” an acknowledgement of the past in the contemporary German state (Chalmers 159). This is what makes Germany well known for monuments that acknowledge the past in that opposes the passivity of the traditional memorial.

The separation of monuments across the Tiergarten region in Berlin Mitte, and the acknowledgement of the past without direct imagery of atrocity in Berlin is “[o]ne of the contemporary results of Germany's memorial conundrum...the rise of its ‘counter-monuments’” or places for contemplation about the idea of memorialization of a particular aspect of the tragedy (Young 271). Germany following the Holocaust is:

Ethically certain of their duty to remember, but aesthetically skeptical of the assumptions underpinning traditional memorial forms...a new generation of contemporary artists and monument makers in Germany [are] probing the limits of both their artistic media and the very notion of a memorial. (Young 271)

The separation of one group in a monument from another is relevant to “the ‘Oppression Olympics’ concern [over] whose genocide should be recognized by the museum and whether or not the Holocaust should be compared with other atrocities” (Chalmers 161). In the case of Berlin, and within the context of the Holocaust, the separation of monuments reveals the plight of each group affected during the atrocity. The abstract nature of the monument for disabled victims provokes a “new generation of artists in Germany” that “may only be enacting a critique of ‘memory places’ already formulated by cultural and art historians long skeptical of the memorial's tradition” that comes with its embodiment within an environment (Young 272). Thus, by using the urban landscape of Berlin, the monument makes itself a part

of that environment with the surrounding scenery, but uses visual distortion to alienate the viewer from reality and create a point of contemplation.

The imagery of the monument in the immediate environment surrounding it provides a model for counter-memorial arguments in Berlin. Specifically, the Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings refers to the memory of the victims embodied within “the monument, an afterimage projected onto the landscape by the rememberer” that overshadows the surrounding environment (Young 279). The creation of the memorial and its location along with other counter monuments near the Brandenburger Tor evokes the past amidst the renewed beauty of the city following the mass atrocities that transpired there and across Germany.

Works Cited

Chalmers, Jason. “Canadianising the Holocaust: Debating Canada’s National Holocaust Monument.” Canadian Jewish Studies. vol. 24. 2016, pp. 149-165.

Konopelski, Daniel. “The Memorial and Information Point for Victims of National Socialist Euthanasia Killings”. 16 May 2023. iPhone 8Plus.

Young, James E. “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today”. Critical Inquiry, vol. 18, no. 2. 1992, pp. 267-296.

Lucky for You, I’m a Vampire: Saltburn’s Queer Abjection

Evan Lorant

Emerald Fennell’s 2023 film Saltburn captured the public consciousness immediately upon its release. It became known as a graphic and shocking film, seminal in many respects. It uses abjection to communicate the horrors of filth and pollution as a threat to class and sexual subjectivity. Saltburn hinges upon two graphic scenes involving the ingestion of bodily refuse which lend themselves to a queer reading of abjection. Julia Kristeva’s “From Filth to Defilement” shows abjection to be an affront to the social order through the presentation of the subject’s boundaries and social divisions. Due to the heterosexual social order that governs the subject’s social construction, the abject must be adaptable based on its relative perception and context. By imposing a queer lens onto Saltburn’s filthiest moments, we can see the abject as a tool for delimiting heteropatriarchal subjects. It adjusts the acceptable definitions of desire and filth to reflect a moving and shifting image of social boundaries.

Kristeva’s “From Filth to Defilement” defines abjection as a force against the separation of the subject from the other. The abject imposes a sense of horror or disgust in its contestation of the boundaries of the subject. Abject substances are those which have challenged the subjective boundary: blood, spit, milk, urine, and feces. These are all abject because they have been banished from the clean and pure body and therefore threaten the bodily margin with pollution, or even defilement (Kristeva 69). Once within but now exiled, it is not wholly other, but decidedly not the self; the abject is not entirely an object, but also explicitly not a subject. The boundary of the subject is fragile; the reaction of horror when we encounter the abject is an effort to reject these things that threaten the purity and cleanliness necessary to maintain subjectivity.

Kristeva understands abjection as existing in tandem with rituals of defilement and sacrality. She draws on the anthropological trope of purification rituals, in which filth is expunged in the name of purity and the sacred. In these movements, the filthy is removed from quotidian context and placed in opposition to the pure. Once ritually divided, these become the sacred and defiled. This exclusion of filth constructs a boundary of the “self and clean” (Kristeva 65). In filth’s alignment with the sacred, its extraction from the symbolic system of secular life, it ceases to be an object at all, and becomes abject (Kristeva 65). Discussing the ritual fear of menstruating women among the Bemba people of central Africa, Kristeva states that “non-separation would threaten the whole society with disintegration” (Kristeva 78). In this case, the abject is a necessary presence, as its exclusion from the clean and sacred self delineates the boundary of that which lies outside subjectivity.

Saltburn follows Oxford student Oliver Quick as he becomes friends with classmate Felix Catton and summers at Saltburn, the Catton family estate. After Felix discovers that Oliver has lied about his tragic family backstory and grew up middleclass in the suburbs, he asks Oliver to leave Saltburn. The night before Oliver is set to leave, Felix dies. After his funeral, Felix’s sister, Venetia, commits suicide. Having lost both her children, Elspeth becomes increasingly dependent on Oliver as a stand-in

for them. James, Elspeth’s husband, bribes Oliver to leave the estate so that the Cattons may grieve alone. About fifteen years later, Oliver encounters Elspeth, whose husband has recently passed away, in a café. In an eleventh-hour twist,Oliver tells Elspeth on her deathbed that he was responsible for the deaths of both Felix and Venetia. After thanking her for writing him into the family’s will he tears out her breathing tube, monologuing about his aspiration to wealth and the family’s own ingratitude and self-centeredness. The film consistently makes use of abjection to display transgression of social boundaries, namely through Oliver’s bathtub scene with Felix, his sex scene with Venetia, and Elspeth’s death scene.

The abject is intimately tied to the mother, incidentally an integral figure in Saltburn. It is the mother’s duty to preserve the clean and proper body, making the approach of the abject a failure of the mother’s authority (Kristeva 72). Once the mother has been constructed as the vanguard of purity, abject material “absorbs within itself all the experiences of the non-objectal that accompany the differentiation from the mother-speaking being” (Kristeva 73). It is the mother’s responsibility to fend off the abject; a challenge to the boundary of subjectivity is a failure of the mother to preserve its purity.

Elspeth is constructed as a paragon of this purity: when describing the rules of Saltburn Estate, Felix tells Oliver that “Mum has a phobia of beards and stubble… she thinks it’s unhygienic” (Saltburn 00:34:00). This focus on cleanliness is consistently reinforced throughout her introduction: Elspeth herself later says, “I have a complete and utter horror of ugliness” (Saltburn 00:36:00). Kristeva suggests that the division of pure/impure not only leads into the subject/other binary, but all difference, including gender (82), sexuality, and class. If Elspeth is the epitome of subjectivity, upholding the family’s purity through her impositions of cleanliness, all of Oliver’s transgressions against her children may be read as fundamental acts of defilement against the mother herself.

Kristeva outlines two categories of polluting objects: the excremental threats to subjectivity that issue from outside the body (decay, infection, disease), and menstrual (blood, spittle, feces), that issue from within (Kristeva 69, 71). The internal category is based on menstruation as the peak of abjection. Indeed, as Elspeth, the film’s symbol of purity, sagely states, “I was a lesbian for a while, you know. But it was all just too wet for me in the end. Men are so lovely and dry” (Saltburn 00:50:50).

In his article, “What Happens in The ‘Saltburn’ Bathtub Scene And Why It Matters” Jason Tabrys spares no detail describing what was received as the most horrifying moment in Saltburn, concerned with sperm, but largely glosses over other moments in the film which similarly constitute the boundary-pushing themes, specifically those featuring menstrual blood (Tabrys). Given that Kristeva explicitly describes sperm as non-polluting, and menstruation as the eponymous internal abject (Kristeva 71), why is the cultural response displayed as the inverse, highlighting the grotesque ingestion of sperm while downplaying the equally transgressive tasting of menstrual blood? This question can be answered byoperationalizing abjection as a dynamic concept, reflecting the changeability of prohibition itself (Kristeva 69). Where prohibition is more severe, abjection seems more shocking, and pollution reveals itself as truly proportional to the social order it challenges.

In order to establish the bathtub scene as the abject zenith of the film, it must be compared to other abject moments; namely, Oliver’s sex scene with Venetia. Oliver approaches Venetia one night in the garden and accuses her of attempting to lure him out for sex. When she protests that “it’s not the right time of the month”. Oliver responds, “It’s lucky for you I’m a vampire” (Saltburn 00:55:30). He proceeds to insert his fingers below her nightgown and lick the blood off them, before performing oral sex.

Oliver uses his sexuality in exercises of abject power, engaging with the Catton children in a sexual manner. “The one scene everyone is talking about” (Tabrys) is one in which Oliver drinks Felix’s inseminated bathwater. Meanwhile,Oliver’s sexual encounter with Venetia, in which he licks her menstrual blood off his fingers and engages in oral sex, is a similar engagement with bodily fluid, yet garnered much less discomfort from popular audiences. In Kristeva’s attribution of abject qualities to bodily fluids, menstrual blood is abject due to its connection to the feminine, while semen is not abject because it is a patriarchal substance, and thus innately tied to the symbolic order. But the audience response to these scenes inverts Kristeva’s categorization. Reading the bathtub scene in the context of abjection, the masculine is bound intimately with filth and waste. Oliver watches Felix masturbating through the open door to their shared bathroom (Saltburn 00:48:45). The sperm, paragon of patriarchy, has “no polluting value” (Kristeva 71); that is, until it is adopted by a subject seeking to threaten social boundaries, as Oliver aims to invade the lives of the Cattons. The bath is a site of cleansing, but when Felix gets out of the tub, he leaves behind his semen mixed with dirt, sweat, and soap. When Oliver crawls in, slurping up the remnants of the bathwater and licking the drain, he has seized the already defiled patriarchal fluid as a signification of his threat to the social symbolic order upheld by the purely sexualized and classed structure the Cattons represent. The bathtub scene shocked and unsettled viewers precisely because it threatened the boundary of sexuality and class that Felix and his family represent: Oliver’s homoerotic advance transgresses heterosexual boundaries and results in abject horror. Kristeva argues that the fluid coming from within the self “stands for the danger issuing from within the identity (social or sexual); it threatens the relationship… of each sex in the face of sexual difference” (Kristeva 71). Oliver internalizes the threat to difference signified in the now-abject semen through his ingestion of the offending fluid as a figure of the lower class. This classed threat is only amplified by the threat of queer love against Elspeth’s matronly rules of Saltburn. Kristeva says that prohibition “founds the abject” (64) as highlighting the fragility of social and symbolic order (68). The presence of the abject highlights the failure of the mother to fulfill the role of maintaining clean social order (Kristeva 72). Abjection is by nature a failure of the mother. By engaging sexually withanother man, Oliver subverts the prohibition of homosexuality, rejecting the normative heterosexual dynamic. This is not an ordinary failure of the mother, but instead an outright erasure of her presence. Once the sexual difference necessitated by heterosexual order has been upset, there is no more authoritative force of cleanlinesstodefendsocialorder.

This subversion of heterosexual difference also explains why Venetia’s menstrual blood was less horrifying than Felix’s bathwater. If the abject is characterized by a

threat to social order (Kristeva 64), an act that binds Oliver back into the social order must be less abject in comparison. The heterosexual sex act is far more compliant with order––menstrual blood notwithstanding—than queer, voyeuristic consumption. Furthermore, their sex scene shows lower-class Oliver kneeling before upper-class Venetia (Saltburn 00:55:22), illustrating their places in the social hierarchy. Though this scene probes the clean division of sexual power through Oliver’s active role (one might say he is ‘topping from the bottom’), Venetia immediately reasserts her authority by refusing Oliver’s demand that she remains at the table after eating (Saltburn 00:59:22). In his relations with Venetia, Oliver can be seen as upholding both heterosexual and class expectations. Informed by Tabrys’ observations about Felix’s semen and its outsized impact on perceptions of the film in comparison to Venetia’s menstrual blood, and when contextualized with the dynamic of the social order, abjection is a fluid state.

Sperm, decidedly not abject, can become abject in a queer context just as menstrual blood, which is definitively abject, may be mollified into supporting the social order. Where the dichotomy of sexual difference is represented by that of purity and filth (Kristeva 82), Oliver’s most striking engagement with filth in the bathtub must be connected with a more severe rejection of the social order of sexuality. In this light, his interaction with Venetia is more reflective of the social order and less abject. Embracing the fluidity of the abject offers a way around Kristeva’s strictly binary thought on sexual difference. Sexual difference here is reaffirmed as a cultural construction and patriarchal tool, rather than an element of our primitive nature, validated by outmoded traditions of anthropology.

Oliver’s threat to the heterosexual social order is secondary to his socioeconomic relationship with the Cattons. As Oliver’s opening narration probes, “I loved [Felix]. But was I ‘in love’ with him?” (Saltburn 00:01:45). This suggests that the attraction Oliver experiences toward Felix is less romantic or sexual than social. Indeed, the class dynamic between them is far more thematically dominant throughout the film than their sexual tension. Oliver is continuouslyportrayed as outof-place, especially against Farley, Felix’s cousin, who is also summering at the estate and seeking to conceal his own racial otherness (e.g., Saltburn 00:58:52). Oliver’s search for upward class mobility, crossing the boundary of the middle-class, is the root of his pursuit of the Cattons’ lives. In drinking Felix’s bathwater, Oliver highlights the fragility of the social order (Kristeva 69), violating sexual difference in service of shattering class distinctions through his inheritance and consumption of the Catton estate.

Oliver’s transgression of social boundaries in his sexual encounters with both of the Catton children is reflected in their deaths as well. Felix is found dead at the centre of the hedge maze after ingesting a drink poisoned by Oliver (Saltburn 01:35:44), a reversal of the bathtub scene. Venetia is found bathing in her own blood in the same tub where Oliver washed her menstrual blood off himself (Saltburn 01:51:46). These call-backs reinforce the connections between Oliver’s sexual transgressions and his destruction of the social order. Through the abject sexual act, Oliver transforms clean and pure subjects into corpses, abject in and of themselves (Kristeva 71). This extends into Saltburn’s penultimate scene, where Oliver kills Elspeth by tearing out her breathing tube (Saltburn 02:02:00). In this climax of the

third act, Oliver vanquishes both the figure of maternal authority and the only obstacle to his flouting the class barrier. This death of the mother, foreshadowed by each abject impingement on her purity, demonstrates Oliver’s absolute destruction of social order.

Abjection is as stable as the social order with which it coincides: that is, it is constantly changing. As demonstrated by Saltburn’s audience reactions, a queer lens is a crucial tool in unpacking the abject in popular culture. When used to understand the sex and death scenes of three crucial characters, Kristeva’s definitions of abject materials prove suggestions rather than a rigid boundary. Despite the patriarchal nature of sperm, the film contextualizes it as a pollutant which contests the social order of heterosexuality. Menstrual blood, which is typically emblematic of the abject, is refigured against the previous transgressions of the film and thus feels less filthy than the ingestion of sperm. Each affront to the social order leads to the final destruction of the mother, Elspeth, who is consistently associated with purity and order. The destruction of purity is coextensive with Oliver’s central goal of escaping the social order of class under which he believes himself to be subjugated. Saltburn helps us understand abjection as something constantly shifting alongside the social conditions in which it is enmeshed.

Works Cited

Kristeva, Julia. “From Filth to Defilement.” 1980. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, Columbia University Press, 1982, pp. 56–89.

Saltburn. Directed by Emerald Fennell, Film, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 2023.

Tabrys, Jason. “What Happens in The ’Saltburn’ Bathtub Scene And Why It Matters.” UPROXX, 30 Nov. 2023, https://uproxx.com/movies/saltburn-bathtub-sceneexplainer/.

Visibility and Voids in Berlin’s Memorial Landscape: How Germany Marks a Self-inflicted Absence

Olivia MacDonald

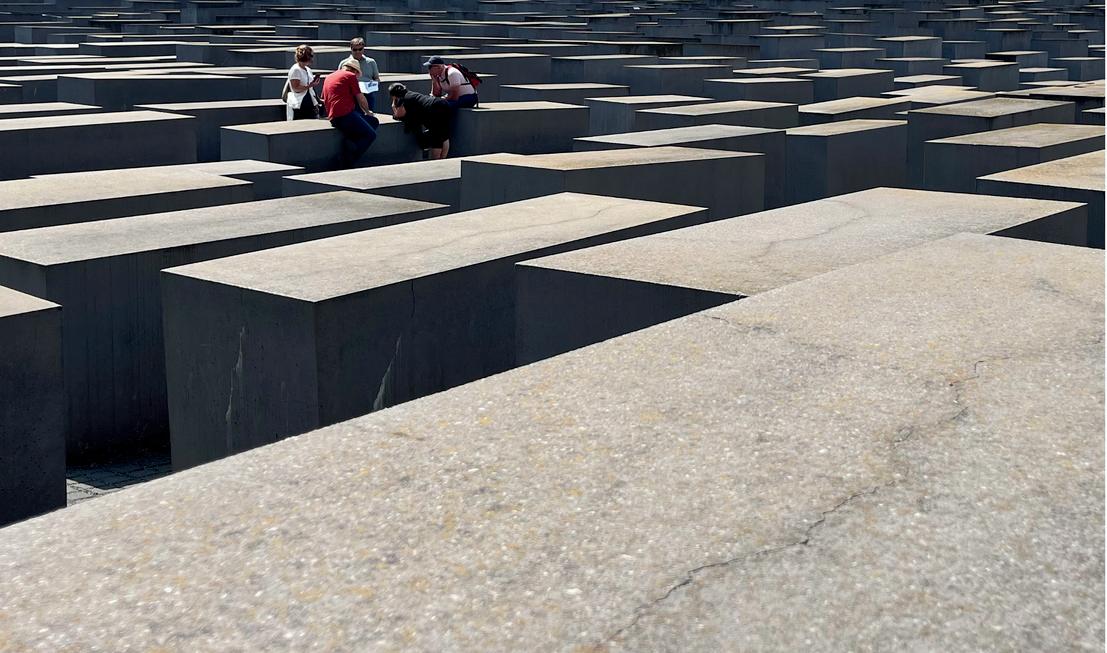

In the center of Berlin, just steps from the Brandenburg Gates sits a field of 2,711 gray concrete pillars known as a Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Field of Stelae or often simply called the Holocaust Memorial. Such a vast and abstract monument demands to be seen and considered, and its visibility is undeniable as numerous visitors walk in and amongst it daily. Peter Eisenman’s Field of Stelae is not alone in its harsh abstract appearance; Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum is also dedicated to the Jewish people and meant to memorialize their absence. Both pieces of Berlin’s memorial landscape were not easily decided upon, and both included years of campaigning, competition, and debate in deciding suitable locations and designs. This essay explores how the abstract and conceptual designs of the Holocaust Memorial and the Jewish Museum effectively address the challenge of commemorating Germany's self-inflicted void of Jewish presence. Their ambiguous design creates an absence of meaning which requires that viewers engage and reckon with the history themselves, or amongst people in their community, thus creating an extension of the debate into a physical form which a more traditional and representationally direct monument could not. As reflected in the artist and committee statements, the visual aspect of a memorial is only one of many which often comes up inadequate for a perpetrator nation reckoning with their crimes. It is the visibility, accessibility and physical immersion of these memorials which makes the suffering of Jewish people and their absence from the city evident not only visually but emotionally for visitors.

A Demand for Visibility: The Campaign and Competition

In the post-war years, Germany was plagued by silence about their crimes and its victims (Young 120). In 1988, feeling the weight of that silence, journalist Lea Rosh and historian Eberhard Jäckel spearheaded the campaign to establish a national memorial to Germany’s Jewish victims and successfully convinced the public that such a memorial was necessary (“Founding of the Foundation”). As Germany looked to forge its identity as a newly reunified nation, Rosh expressed the danger of forgetting the past as they looked to the future. It became her mission to have a visual mark of remembrance in the nation’s new capital in part as a “process of selfunderstanding” (“Founding of the Foundation”). In Karen Till’s The New Berlin, Rosh expresses how the catalyst for her interest in seeing a monument in Berlin was visiting the Path of the Just at the Yad Vashem memorial, which commemorated anyone who had helped Jewish people escape deportation and death during the Holocaust. For Rosh, it was the visibility of this monument—and in part, the absence of German names—that sparked this need to see a memorial in Germany that rather than commemorate its victims of the war would acknowledge itself as the perpetrator (Till 162-163).

In 1994, the German Bundestag initiated an international contest for designs of the pre-named memorial. Despite providing minimal guiding instruction, all artists

and architects had to work their designs to fit that title. Nonetheless, 528 design proposals were submitted (Young 187). This initial competition was judged by a jury with fifteen members, some experts and some citizens who decided upon a design by Christine Jackob-Marks: a giant tilted gravestone engraved with the names of Jewish victims and scattered with eighteen boulders to represent Jewish mourning traditions (Young 189). This very literal design was met with disapproval from important figures of the German Jewish community causing the government to retract their previous approval of the design. Amid controversy, the competition reopened in 1997 with a much more select pool of entrants. Twenty-five participants, including the top nine finalists from 1995, received invitations to submit a design. Eisenman's design was ultimately chosen from these submissions (Young 208). Even after deciding on the design, the debate persisted regarding its construction, leading to several amendments. The number of pillars initially proposed, around 4200, was reduced to 2,711. Additionally, an underground information center was incorporated into the site at the urging of Minister of Culture Michael Naumann. He disagreed with the design's abstract nature and the limited opportunities for learning and contextualization (Young 218). In 2005, The memorial was completed and opened to the public year-round (“Founding of the Foundation”).

The process of deciding upon and building the Holocaust Memorial is known for its difficulty and debates; however, the history, decision-making, and construction of the Jewish Museum were equally challenging. The Jewish Museum in Berlin opened in 1933, just a week before Hitler became Chancellor, and operated for 5 years, serving as a space to exhibit Jewish art and culture (Young 156-157). In 1933, the Jewish Museum “hoped to establish the institutional fact of an inextricably linked GermanJewish culture” countering the Nazi notion of inherent hostility between German and Jewish identity (Young 156). Displaying the works of German-Jewish artists such as Max Liebermann was one method the museum used to indirectly challenge Nazism. However, following Kristallnacht, the museum's director was deported to Sachsenhausen, its contents confiscated, and the site destroyed by Nazi officers in 1938 (Young 157). After the war, the Berlin Museum began collecting materials to curate a show on Jewish history, with its first exhibit on Jewish life unveiled in 1971: “Contribution and Fate: 300 Years of the Jewish Community in Berlin, 1671-1971” (159). This sparked a debate around how to handle a Jewish collection in Berlin this was a matter of visibility for Jewish culture in Berlin. Should the Jewish Museum be a separate entity from the Berlin Museum? As some argue this would effectively perpetuate the assumed separation between Jewishness and Germanness, even though before 1933 there was a thriving Jewish community in Berlin and greatly influenced its culture (Young 159). The alternative option was to continue incorporating Jewish collections within the Berlin Museum, a choice that faced criticism for continuing to keep "the culture of the murdered in the house of the murderer” (Young 160). In 1987, the decision was made to maintain affiliation with the Berlin Museum but to expand the exhibitions on Jewish culture into a distinct department with its own building. This led to the project's official name: "Extension of the Berlin Museum with the Jewish Museum Department" (Young 160-161). In that same year, the Senate organized an anonymous contest for the design, eventually selecting Daniel Libeskind's radically conceptual zigzag design a year later (Pavka

“AD Classics”). This ‘extension’ to the old building— connected underground to the original— juxtaposes the style of the old baroque building with its modern titanium exterior, slashed through with abstractly shaped windows. This design was chosen as it was the only bid which decided to use the form as an expression of Jewish life in Berlin before, during and after the Holocaust (Pavka “AD Classics”). He created the jagged shape of the building from a map of what he calls “Berlin’s cultural Jewish topography” (Young 167) which mapped out the places where Jewish composers, writers and poets once lived (166-168). This shape is cut through by an invisible straight line which leaves in its wake openings in the building—Voids (Young 164-165). The presence of these voids and interruptions serves as a commentary on the tangible absence of Jewish people in Germany resulting from the Holocaust.

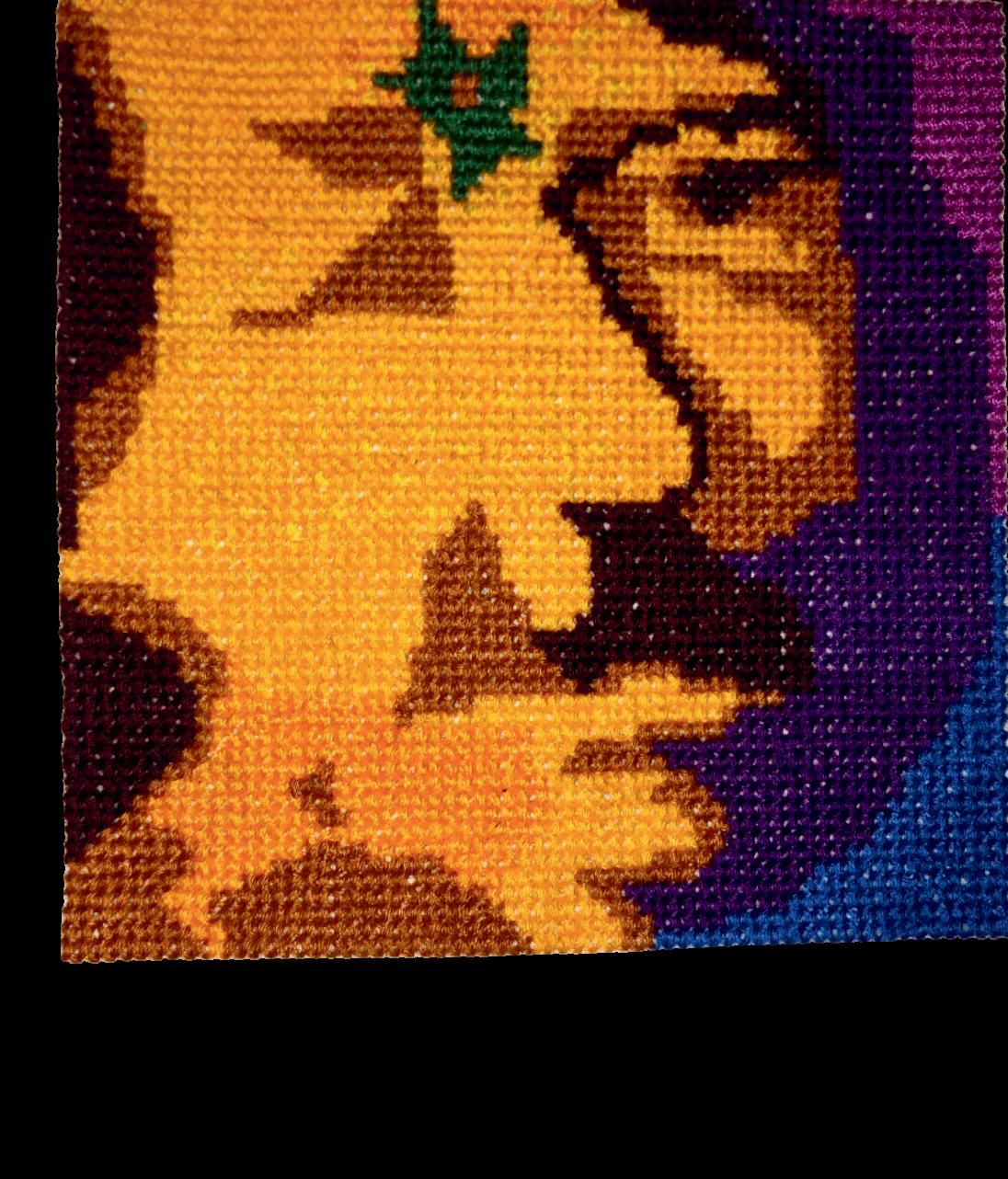

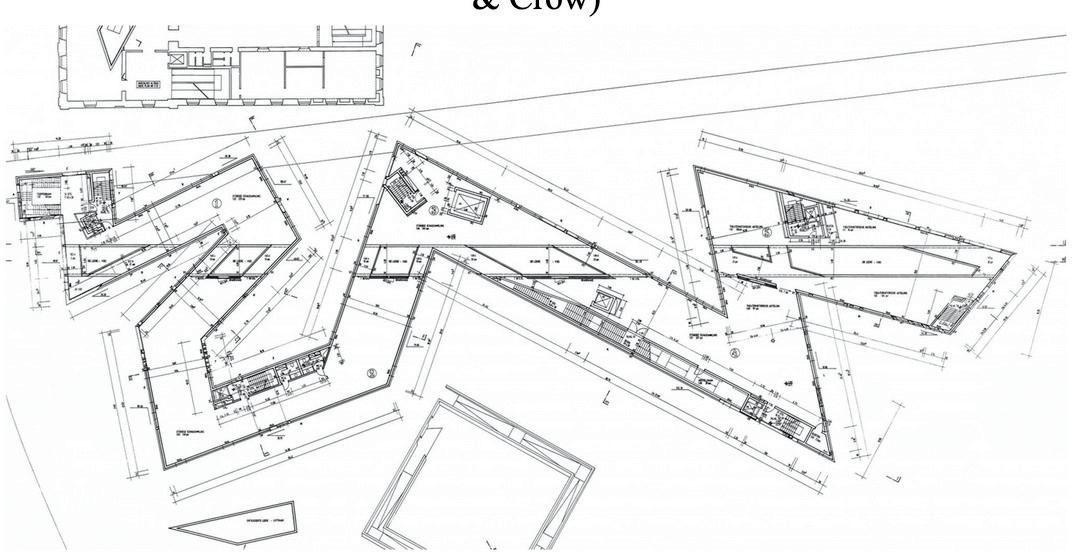

Fig. 1 Jewish Museum, Libeskind Building next to Old Building (Hufton & Crow)

Fig. 2 Ground Floor Plan (Libeskind)

A Demand for Voids: In Protest of Monumentality

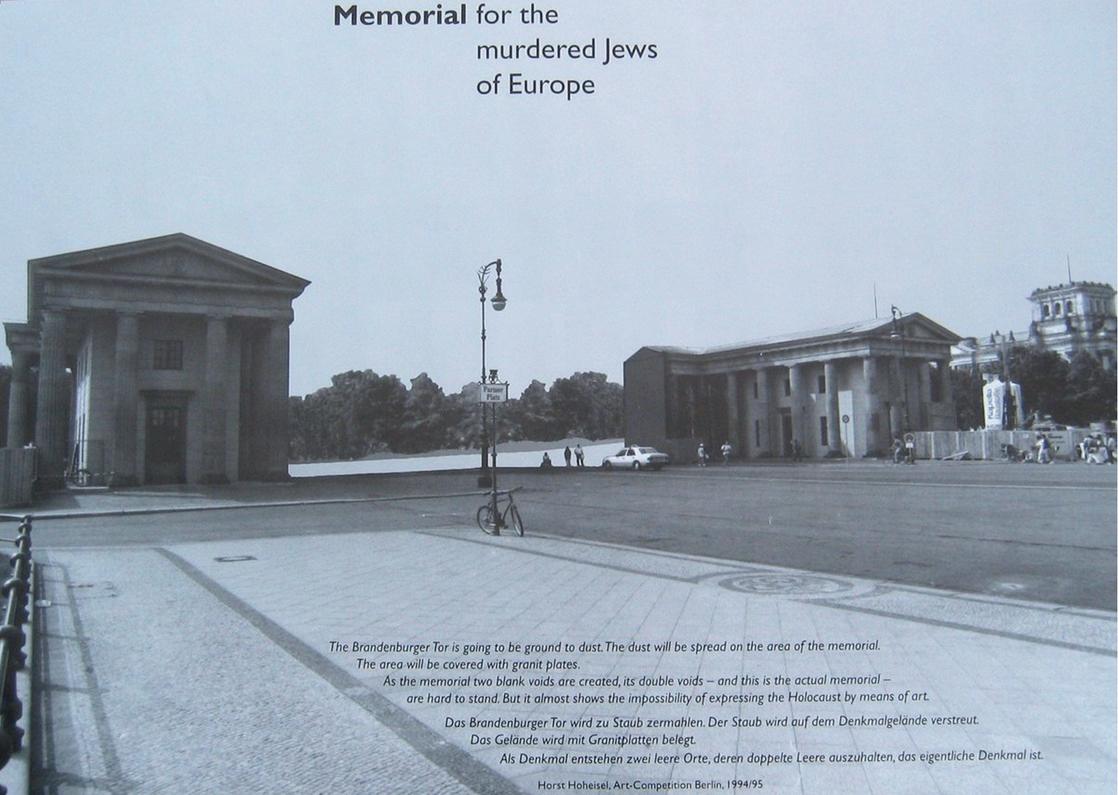

“

Let’s Blow Up the Brandenburg Gate!” This is what Horst Hoheisel submitted as proposed monument for The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in 1995 (Young 90). This proposal and its departure from the original prompt are part of a larger reaction felt by many at the idea of a monument to remember the absence of Europe’s murdered Jews: how can such a void be filled by anything at all? How representationally inadequate is a monument that depicts the suffering of Jews, if in trying to represent this suffering the monument would only nullify the reality of it — a sentiment which is similarly reflected in the famous quote from Theodor Adorno, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric'' (Koerner 18). James Young writes about Hoheisel’s proposal, “How better to remember a destroyed people than by a destroyed monument” (90). Hoheisel is not alone in proposing the “values of invisibility” (Callaghan 255), submissions such as Rolf Storz and Hans Jorg Worhle’s Empty Memorial Plaza (Young 202) claim a blank space in the city the place of a traditional monument. Similarly, in Saarbrücken, Jochen Gerz’s Place of the Invisible Memorial 2146 Stones Against Racism is another example of a monument that proffers the value of invisibility as a space for memory (Young 140). In 1997, as a memorial to the 2,146 Jewish cemeteries in Germany that were destroyed or left abandoned, he enlisted the help of students to steal about 70 cobblestones from the square in front of Saarbrucken Schloss, the former site of the Gestapo under Hitler. They removed the stones, inscribed with the names of some of the now-missing

cemeteries and returned to the square before anyone was aware (Young 142). When visitors entered the square in search of a monument, they became the memorial: “the only standing forms in the square, the visitors would become the memorials for which they searched” (Young 144). The problem with such a memorial as Gerz was aware was that its invisibility meant that the proliferation of meaning was dependent on continued public knowledge of the act of memorialization and what it stood for (142). Indeed, Gerz found success as the square was renamed "Square of the Invisible Monument," serving as a perpetual public acknowledgment of its presence. However, the inherent risk in employing invisibility within any monument lies in the potential for the intentionality behind the absence to fade from memory. This mirrors the exact concern many had with a traditional concrete monument— the challenge of commemorating something without inadvertently allowing it to fade into history and obscurity. The protest against a traditional monument may come from the notion that there is something finalizing about a monument, it marks something as past, part of the city's history rather than something that is felt and grappled with daily. As Hoheisel said, “every public work of art is an act of closure, not remembrance” (Callaghan 256), and since it is the perpetrator nation searching for closure with their crimes, Hoheisel and many others find the desire to build a monument to be disingenuous (Young 197). Additionally, beyond suggesting that the mourning process has ended— the absence amended by a memorial in the center of the city— some suggest that a large monument counterintuitively would become invisible. In 1927, Robert Musil describes this in his essay “Monuments”:

“There is nothing in the world as invisible as a monument. They are surely erected to be seen, indeed, to attract attention; but at the same time, they are impregnated with something that repels attention…One cannot say we do not notice them; one would instead say that they elude our senses” (Callaghan 225).

In other words, as time passes, statues and memorials often become mere fixtures in the cityscape, fading into the background of daily life for inhabitants. Their significance and purpose as memorials gradually diminish, and the true intention behind their commemoration is lost on those who encounter them regularly (Koerner 9). Where visible monuments become unconsciously invisible, perhaps as Hoheisel seems to suggest, the answer is spaces of invisibility or the destruction of something else that has become invisible. The Brandenburg Gate, meant as a symbol of German unity

Fig. 3 “Blow Up the Brandenburg Gate” (Hoheisel)

and peace Hoheisel suggests, is part of Germany’s deluded self-image that it can simply repair and move on from the past.

Another stance taken against the construction of fixed monuments is that the debate itself is a better way to remember than anything that could be built. Unlike a monument, the competition and subsequent debate surrounding the construction is alive with discussion and demands attention, resisting the “closure of memory” (Callaghan 31). The initial 1995 competition was considered a failure by some. However, others, including Young, viewed the competition itself as a success due to the large number of entries and the ensuing public debate and discussion, which served as a form of memory work. In Young’s words: “If the aim is to remember for perpetuity that this great nation once murdered nearly six million human beings solely for having been Jews, then this monument must remain uncompleted and unbuilt, an unfinishable memorial process” (Young 191), A fixed monument and its finality would put an end to the real monument, the debate, but without architecture, where can the debate be housed and not forgotten?

Conceptual Monuments: Towards Emotional Architecture

How do artists and architects combat the inherent ineffectuality of monuments and the fleetingness of a debate, given concerns about possible complacency and inadequacy arising from monument designs, and the worry that voids might easily be forgotten without a visual marker? Analyzing Libeskind and Eisenmann’s designs to understand how a monument can generate and house a debate, both on an individual level and within a group can explain how best to address and memorialize Germany’s self-inflicted void of Jewishness without cementing it as something of the past. Peter Eisenman’s Field of Stelae is made up of 2,711 concrete pillars that protrude from uneven ground at various heights and angles, from flush with the ground up to ten feet above, towering over the heads of anyone who enters (Young 210). The abstract site lacks any clear meaning or symbolism, though many associate the gray pillars with tombs, which is a symbolic association that Eisenman denies (Louisiana Museum of Modern Art). However, controlling the interpretation of the stelae by visitors and their diverse ways of interpreting and interacting cannot align with the purpose of its

abstractness; the appeal and intention of the monument lie in the uncontrollability and personal nature of individual interpretations. Unlike traditional didactic monuments, Eisenman’s design is not trying to teach its visitors a clear moral message or provide them with a sense of closure, instead this monument requires visitors to think about the space and their place in it.

Fig. 4 A Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Details (MacDonald)

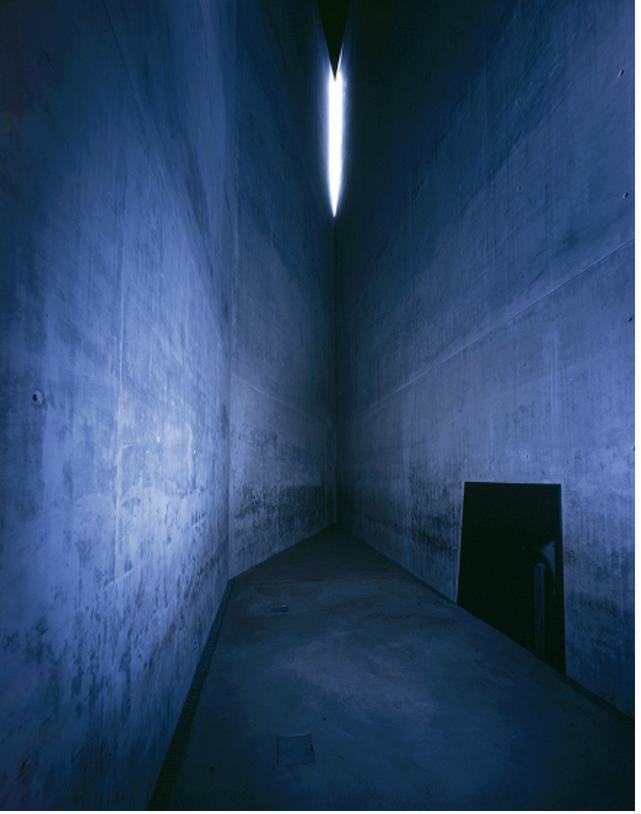

In an interview with Spiegel Online, he explained, “The world is too full of information and here is a place without information. That is what I wanted” (Craven “The Controversial Holocaust Memorial”); Although it was against his initial design, the information center is there to provide concrete historical answers, as a memorial is a place meant to generate questions. To encounter the information, one must first consider the abstract monument. By design, there is no way around this due to the overwhelming visibility of the site; Information Center visitors will have to participate in the monument and create meaning to access answers. Eisenman described getting lost in a cornfield as one source of inspiration: “There are moments in time when you feel lost in space. I was trying to create the possibility of that experience, that frisson, something that you don't forget” (Sudjic “Feuds? I’ve Had a Few”). By engaging with the architecture, one creates a similar disorientation and the actions of others become integrated into the memorial experience: getting lost among strangers, briefly encountering them, and swiftly losing sight, thereby simulating a sensation of continual loss (Åhr 285). Eisenman expresses how he does not care how people interact with the monument because the meaning comes from them, it is a public space and the people within it are on equal footing with the monument (Young 210). Things like children running around, sunbathing on the stones and even graffiti do not bother him, as in his opinion these actions are also expressions of how people feel just as much as people being bothered by such actions— this is where the debate is housed (Craven “The Controversial Holocaust Memorial”). Individuals are just as much part of the space as the stones. The process of contemplation and debate remains individualized and repeatable, incapable of reaching completion. This same ideology of immersive individual experience applies to Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, the three Axis: the Axis of Exile, the Axis of the Holocaust, and the Axis of Continuity create the lower level of the building. The Axis of Exile ends with the Garden of Exile which has a strikingly similar design to Eisenman’s Field of Stelae and is meant to evoke a similar experience of feeling lost after being exiled. The Holocaust Tower is meant to simulate the feeling of oppression and anxiety experienced by Jewish people during the Holocaust (Jüdisches Museum Berlin).

Fig. 5 “Field of Stelae of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” (Foundation Memorial)

Fig 6 “Holocaust Tower” (Ziehe)

Other exhibits are meant to engage the visitor with a sense of understanding in a noninformational way, such as Menashe Kadishman’s Shalekhet (Fallen Leaves), which inhabits the ground floor of one of the museum's voids.

The installation invites visitors to walk on over 10,000 faces cut from iron plates, listening to the grating sound of metal on metal. This experience disturbingly places the visitor in the position of a perpetrator (Jüdisches Museum Berlin). The museum aims to educate its visitors about something specific—Jewish history and culture. Yet, beyond the exhibits and information, it's the medium in which they're presented that molds the narrative of how visitors receive that information. Libeskind hopes that as an effect of its design, the building will not just house the collection but challenge the visitors' preconceptions about the collection through the lens of the designs disorienting and defamiliarizing nature (Young 175). Like Eisenman, Libeskind attempts to negate a sense of closure and finality through voided spaces that imply discontinuity and prompt further unanswered questions.

Berlin's memorial landscape, exemplified by the Holocaust Memorial and the Jewish Museum, represents a unique approach to marking Germany's self-inflicted absence of Jewish culture and the horrors of the Holocaust. The designs by Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind share a common characteristic of utilizing architecture to evoke a sense of loss and absence without explicitly representing it. These designs, with their abstractness and ambiguity, demand engagement and contemplation from visitors, extending the debate surrounding Germany's history and crimes into a physical form. The visibility and accessibility of these memorials, combined with their immersive nature, create an emotional experience for visitors, making the suffering and absence of Jewishness in Germany something that is never fully healed, it is something that each visitor will need to consider when trying to understand the memorials. By challenging traditional notions of monumentality and embracing conceptual approaches, these memorials offer a powerful means of grappling with the past and ensuring that it is not forgotten or diminished over time. Ultimately, Berlin's memorial landscape serves as a testament to the importance of visibility, and architecture as a place to house debate, collective memory and perhaps an unfixable void.

Works Cited

Åhr, Johan. “Memory and Mourning in Berlin: On Peter Eisenman's "Holocaust-Mahnmal" (2005).” Modern Judaism, vol. 28, no. 3, 2008, pp. 283-305.

Callaghan, Mark. Selected Proposals From the Berlin Holocaust Memorial Competition and the Winning Design By Peter Eisenman: Memory, Commemoration, Aesthetics and the Representation of Difficult Histories. 2019, Birkbeck, University of London., https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40378/. Doctoral thesis.

Craven, Jackie. “The Controversial Holocaust Memorial by Peter Eisenman.” ThoughtCo, 18 July 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/the-berlin-holocaust-memorial-by-petereisenman-177928. Accessed 16 June 2023.

Foundation Memorial. “Field of Stelae of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, https://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/e n/memorials/memorial-to-the-murdered-jews-of-europe/#Stelenfeld. Accessed 14 June 2023.

“Founding of the Foundation.” Stiftung Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, https://www.stiftung-denkmal.de/en/foundation/founding-of-the-foundation/. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Hoheisel, Horst. Blow Up the Brandenburg Tor. 1995.

Hufton, and Crow. “Jewish Museum, Libeskind Building next to Old Building.” Building Blocks: Rethinking the Facade in Berlin, Archdaily, 2 June 2022, https://www.archdaily. com/91273/ad-classics-jewish-museum-berlin-daniel- libeskind. Accessed 16 June 2023.

Jüdisches Museum Berlin. “Shalekhet – Fallen Leaves | Jewish Museum Berlin.” Jüdisches Museum Berlin, https://www.jmberlin.de/en/shalekhet-fallen-leaves. Accessed 16 June 2023.