10 minute read

MV WAKASHIO – COUNTDOWN TO AN ENVIRONMENTAL TRAGEDY

MV WAKASHIO – A SLOW COUNTDOWN TO AN ENVIRONMENTAL TRAGEDY

The Japanese owned, Panama registered capsize bulk carrier, MV Wakashio, discharged her cargo of iron ore in China on 4 July and was routed, in ballast (no cargo onboard), via Singapore to Brazil where she was due to arrive on 13 August. She never did. Instead she ran aground on a coral reef 1 mile off the south east coast of Mauritius at 11 knots at 1925 hrs on 25 July having apparently not slowed or altered course. While owners and authorities had believed she could be refloated she started to move along the reef and eventually one of her bunker oil tanks ruptured (tanks containing the fuel for the ships engine and generators). On the 6 August there was a significant loss of around 600 to 800 tons of low sulphur fuel oil which spread into the lagoon between the reef and the shore and along nearly 30 kms of the protected bio-diverse marine waters of the Mauritian South East coast.

It seems surprising that a 300m long, 50m wide, modern, well crewed, global travelling super carrier could strike a reef that it had approached in day light. However, the world was as shocked as the local Mauritians who woke to see this vessel, sitting high and proud, just a mile from their shore. For many fishermen, her bridge looked down onto their prized fishing grounds. She sat on a reef that is a key destination for tourist visitors who dive to wonder at the marine diversity on the reef and in the lagoon it protects.

For the last 20 years, the Mauritius Government had sat as the ‘poster boy’ in East African oil spill response having received various tranches of inward investment totalling over $15M in training and equipment resulting in capability for which it was respected. As MV Wakashio sat for a week she was slowly deteriorating. Battered by a storm, with no suitable tugs yet available or anchors able to be set to stabilise her position, she ‘walked’ 500m along the reef and ended up with her stern sections locked onto and being torn apart by it. With the stern no longer able to move her 22mm steel hull was starting to bend, twist and fail. On 6 August the first failure occurred causing between 600-800 tons of fuel to spill from her.

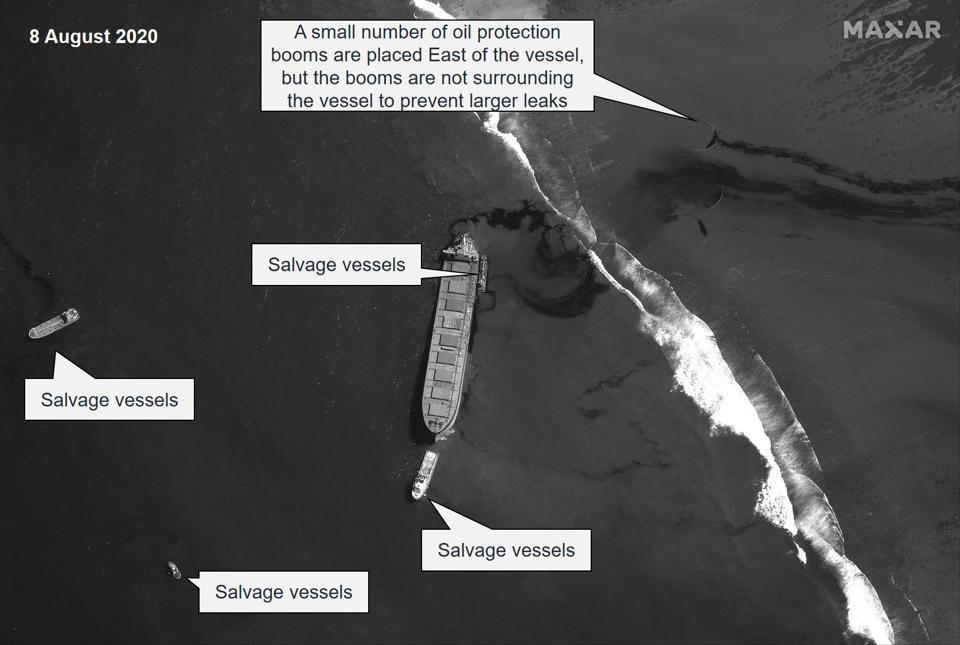

Efforts were made to transfer oil internally and to schutz tanks and drums on the deck. However it was not until the 8 August, two days after the fuel leak, that another tanker was able to get alongside and serious inroads could made in pumping out what was left of the 3894 tons of bunker and other oils she had on board when she grounded. Meanwhile what had been lost was causing distress to the people of Mauritius and harm to the diversity and marine habitats along the beautiful coastline.

It was also galvanising these communities into a wave of action that surprised the world. Dwarfing the government response, a public call to action saw local Mauritians and NGOs mobilise in their thousands to manufacture bagasse booms using sugar cane leaves, hair, plastic containers and plastic sheeting. Fishermen deployed them and as a result protected many coastal areas and prevented the migration of oil away from areas it had already impacted .

The shock at the event and a desire for action prompted, what the organisers reported was over 100,000, people to demonstrate their desire for more action on successive Saturdays throughout late August and into September.

The impact of the spillage eventually extended some 30km along the coastline. Early action by the government saved serious contamination of the Blue Bay Marine Reserve but areas downwind and to the East of the vessel were the worst affected and this included some mangroves swamps (10% were affected but 90% were protected by the co-ordinated response actions). Deployment of what existed as the government stockpile together with hundreds of ‘home-made’ bagasse booms held some of the lost oil at sea or close to beaches so that it could be recovered before it reached the shore or move again to unaffected areas.

In late November the picture is more positive. The clean-up changed scale in late August with the arrival of professional teams from France, Japan and India. The work started on the large public areas and sand beaches where volunteers were crucial to using smaller teams for the more sensitive sites. Polyeco, Mauritius’ preincident oil spill response service provider have worked hard since the incident began and supplemented their team with other professionals from their parent company in Greece. The Government encouraged and supported them, and the ship owners’ appointed contractor, Le Floch from France, in employing local people to work alongside their responders and scientists. Nearly 200 Mauritians continued to form the backbone of the cleanup workforce of over 300 people full time engaged in the clean-up operation.

As a result, the spill responders expect to complete their work by the end of February or in March 2021. Beaches are now starting to re-open, some fishing areas have been opened and more are likely to open before Christmas. The stern section of the ship remains on the reef and will be removed during first quarter of 2021 when weather and resources can be deployed for the wreck removal operation for which a contract has now been let. Tourism, so heavily impacted by COVID and then this spill, is slowly returning. However, it is too early to assess the long-term environmental impact on wildlife. There is no doubt the public and NGO effort helped to minimise harm in some accessible areas and early signs are positive but equally the environmental damage of oil, the clean-up operation disturbing habitats and affecting eco systems will continue for some time. Investment will be required to restore what has been damaged over the long term. A spill like this in such a delicate environment cannot occur without significant effect. So how did this happen?

On 9 Sept. the Panama Maritime Authority issued an initial report which was very critical of the seamanship in the hours leading to the grounding on a number of points:

The vessel deviated from its approved navigation plan, to round the Cape of Good Hope. The Captain authorised the approach so close to the shore, apparently to gain telephone and internet signal. The navigation system displayed the wrong scale charts. At the time of the grounding the Captain, First Officer and Chief Engineer were on the bridge.

Since then the shipping company have stated that there is full satellite communication available to its crew with telephone and internet access for all. Other reports have questioned whether the vessel did strike the reef at 11 knots or meandered around more slowly beforehand as if dropping something off. A problem with the engine room has also been alleged.

The question remains why put the vessel in danger by going so close to the shore? Why run aground on a reef when the surf line would have been obvious to anyone on the bridge?

Why did the vessel completely ignore all calls from the Mauritian authorities about its intentions as it closed the shore having entered Mauritius territorial waters at 2342 hrs 23 July nearly two days prior to her grounding. Why do this?

The Government reaction has been criticised, locally and internationally. A similar incident when the MV Benita grounded had resulted in the ship being refloated in equally challenging conditions. This going to demonstrate that a past success is no guarantee that the next incident will result in the same outcome. The details of the challenges, decisions and circumstances will eventually be independently reviewed and hopefully we can all learn from this for future incidents.

Some of the delay in action could have been to do with COVID restrictions which required the crew to be tested before any support could come onboard. Was the rigidity of their POLMAR plan, which dictated that as no oil had been lost, there was no need to instigate a response? Only when a loss above 10 ton occurred did the plan trigger action by making it a Tier 2 incident.

Was the responsibility for a response sat with the owners of the vessel who had appointed SMIT salvage to manage the incident. Was inaction therefore their fault? Indeed, when SMIT arrived on the vessel on 31 July they confirmed that they were confident of salvage…….

The legal issues still continue. The Captain is held in custody on the island and in late October a bail application was refused. He has been charged with unlawful interference with the operation of a property of a ship likely to endanger its safe navigation and is likely to face a severe penalty by the court. No trial date has been set but an appearance is expected in January.

The insurance issues still remain unresolved. To date commitments have been made to the tune of

Japan Mitsui OSK Line the charterer of the ship (hired to go to Brazil to pick up and transport cargo for them) had no legal liability but have committed $9.42m to help Mauritius to target effort on the mangrove forests and an environmental recovery fund.

With regard to response costs and compensation for financial losses as signatories to the Bunker Convention the island is entitled to compensation but as signatories to the Limit of Liability Convention 1976, the limit of liability is approximately $18.7m. However had they signed the 1996 version this would be over $40m, a similar lesson learned in recent years by Australia and New Zealand with respect to incidents involving MVs Pacific Adventurer and Rena. The costs of salvage effort and wreck removal being outside and paid separately to this.

The majority of the compensation will come from the Japanese P&I club who are ‘trying to make internal estimates’ for the cost of the cleanup and work with the government to identify and compensate those affected.

UK and Ireland Spill Association have now conducted two webinars on this incident. The recordings of these can be viewed through the website: www.ukspill.org and in our Youtube

channel.

Without COVID the impact on tourism could have been significant but given the island was already closed that impact is difficult to determine but post COVID it is the reputation of this beautiful island that needs to be restored so tourism can recover.

CONCLUSION

All observers who witnessed this incident were saddened to see pictures of oil reaching pristine shores and then the sight of people in Tyvek suits covered from head to toe in it. Nearly five months later we still do not know why this incident happened.

As spill responders the incident highlights the high cost of delay in responding and take all steps necessary to mitigate the possible effects of any spill or potential incident. The week of inaction following the grounding sealed Wakashio’s fate.

Any response plan must be flexible to allow concurrent, or preventive, action to take place even if, after the incident, the action may not have been necessary. The plan must also be practised, tested and evolve based on experience.

Communication to all stakeholders, in this case particularly the public and the media, must be clear, honest and consistently delivered. The vacuum that existed here has not helped the Government, those who have invested it is pollution response over the last 20 years and Mauritius’ global reputation.

With maritime shipping forecast to increase further is it time that response to these incidents is based on preventing environmental harm rather than worrying about who is going to pay. Surely that can come later!