Jacob Freedland on Yiddishism - Agne Knuiraite on her Ukrainian childhood

Charlotte Cobb on Gene Simmons and Israel - Xander Ross on Jew-perheroes

Ainsley-Kay Rucker on building a community

Jacob Freedland on Yiddishism - Agne Knuiraite on her Ukrainian childhood

Charlotte Cobb on Gene Simmons and Israel - Xander Ross on Jew-perheroes

Ainsley-Kay Rucker on building a community

‘What’s your favourite JSoc?’ is a question I’m often asked. Whilst my rigid impartiality forbids a straightforward answer, the conceptual answer dawned on me last Shabbat. I was staying with the Jewish community in South Hampstead as part of the Rabbi Sacks Fellowship and a source spoke to me. We were exploring the later portions of the book of Exodus (including my Bar Mitzvah Terumah) which depict the construction of the Tabernacle - the temporary Temple the Israelites used for worship whilst in the wilderness.

The Torah spends a surprising amount of time covering the Tabernacle. In Genesis, the world is created in a mere 34 verses. In the books of Exodus, hundreds of verses across Terumah, Tetzaveh, Ki Tissa, Vayakhel and Pekudei are dedicated to the creation of a temporary sanctuary for the Israelites to use whilst journeying through the wilderness. Rabbi Sacks takes this seemingly technical and antiquated set of instructions and reclaims it as a political text. In the first half of the book of Exodus, the traumatised Israelites are taken out of Egypt. In the second, “a nation is created through the act of creation itself … God was in effect saying to turn a group of individuals into a conventional nation, they must build something together”. I’ve seen this idea born out in dozens of Jewish societies across the UK and Ireland. In The Home We Build Together, Sacks details the distinguishing

features of the Tabernacle model. In his words:

• Identity is achieved: It is not granted. We are what we do.

• There is an integral connection between giving and belonging. Because we are co-creators of society, we are members of it in a strong sense.

• It is a model that focuses on responsibilities, not rights.

• It focuses on altruism rather than - as in the social-contract model - the convergence of multiple calculations of self-interest.

• It focuses on the future, not just the past. The national narrative, which includes the people’s past, is still being written and we are its co-authors.

• It is teleological. It focuses on purpose, not status. Every contribution counts.

• It carries with it a strong sense of the common good: the Tabernacle is a symbol of collective dedication.

When a JSoc President or committee member comes to me with a difficulty, I often think about R’ Sacks’ Tabernacle model, which is strikingly applicable to JSocs. The strongest JSocs are those with a clear sense of collective identity, in which members give their time for the sake of society. They are purpose-driven, peer-led and self-sustaining. In my years at uni, on a Thursday night JSoc would gather and

peel potatoes and chop veg in a slightly crusty kitchen. Cooking together brought us together. I’ve seen the unifying atmosphere sustain JSoc committees setting up for socials or laying the tables on a Friday afternoon.

Some wrongly see the Jewish student sector as a marketplace and attempt materialistic incentives to fend off perceived competitors. In my experience, Jewish students resent being treated as consumers. The best activists are unpaid, the most dedicated JSoc presidents are altruists, and the most vibrant JSocs aren’t the best resourced. Jewish student life is sustained by our common interest, as opposed to the convergence of self-interest. Another quality essential to a thriving JSoc is diversity. The best student communities prioritise unity over uniformity. In the eleventh chapter of Genesis, we are offered a picture of a uniform and ambitious society, one that built the Tower of Babel: “The whole world was of one language and of one common purpose.” Whilst the idea of a society united in a creative endeavour at first seems com-

pelling, this is ultimately rejected by God, the chapter continues: “Thus the Lord scattered them from there over the face of the whole earth, and they stopped building the city”. Rabba Sara Hurwitz in her compelling analysis cites the Pirkei Derabi Eliezer’s commentary on this chapter to explain the problem inherent in the Tower of Babel : “It had seven steps from the east and seven steps from the west. Bricks were hauled up from one side, and the descent would be from the other. If one man fell down and died, no attention was paid to him, but if one brick fell down, they would sit and weep.” According to the Pirkei Derabi Eliezer, this was a deeply materialistic society, one that valued property over people.

Early Modern England in my first year at university; it was hard to come to terms with the array of religious and political doctrines of seventeenth-century England. Amidst a plethora of differing ideologies - Diggers and Levellers, Quakers and Dissenters and many more - Milton makes the case for free speech: “Where there is much desire to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinion in good men is but knowledge in the making.” The best JSocs aren’t solely Orthodox or Progressive, they aren’t right or leftwing. Rather, they are home to arguments for the sake of Heaven, for it is in the exposure to other ideas that our own become refined. Fascinatingly, Milton uses the building of the Temple, to prosecute the case against conformity and uniformity:

many moderat varieties and brotherly dissimilitudes that are not vastly disproportionall arises the goodly and the gracefull symmetry that commends the whole pile and structure.

At the UJS convention in February, we tried to actualise this ideal. On Friday night we held five simultaneous services recognising our is a song sung in harmony, not a solo. Jewish students pitched into every activity and delivered countless sessions for their peers and we built an unforgettable weekend together. The words of the Talmud in Brachot spring to mind: ‘Call them not ‘your children’ but ‘your builders’’. When students fly the nest, move away from home and build something together they gain as much as they give.

Putting these two biblical passages together, we can infer that the ideal society whilst creative is not conformist. It makes space for difference. Returning to the concept of a Temple, Sacks looks to a lesser-known passage in the John Milton Areopagiticathe seventeenth-century poet’s defence of free speech. I remember struggling with

… as if, while the Temple of the Lord was building, some cutting, some squaring the marble, others hewing the cedars, there should be a sort of irrationall men who could not consider there must be many schisms and many dissections made in the quarry and in the timber, ere the house of God can be built. And when every stone is laid artfully together, it cannot be united into a continuity, it can but be contiguous in this world; neither can every peece of the building be of one form; nay rather the perfection consists in this, that out of

So to return to the question I avoided at the start of this piece, my favourite JSoc isn’t homogenous. It does, however, possess ‘brotherly dissimilitudes’. It doesn’t need the grandest ball or the most members. It doesn’t need celebrity speakers or sushi platters, it has a dedicated committee that always turns up out of concern for the community. My favourite JSoc is a JSoc in which everyone contributes a part of themselves and they, in turn, feel a part of it, the JSoc relies on the strength of its students not its sponsors. My favourite JSoc is the one we build together.

The

Guy Dabby-Joory, Editor-in-Chief

Sarah Wilks, Editor-in-Chief

Edward Daniel, Design Editor

Joel Rosen, Editor-at-Large

Dora Hirsh, News Editor

Grace Silverstein, Design Editor

The ideal society whilst creative is not conformist.

On a cold weekend in February, we welcomed nearly four hundred students to UJS’s biggest event of the year, the pinnacle of student democracy, a beacon of cross-communalism, a festival of peer leadership: UJS Convention. This was quite a feat considering the country had been brought to a standstill by rail strikes! Fortunately, coaches were organised from campuses around the country to transport students, and before we knew it, the site was buzzing with Jewish students from across Britain and Ireland.

Once students arrived, they were presented with beautiful dark green hoodies. After they had some time to socialise, explore, find their rooms and ready themselves for Shabbat, students had the opportunity to attend their choice of Kabbalat Shabbat services according to their tradition, with the options of Orthodox, Sephardi, Egal, progressive and explanatory services available to all students. They were all led by student volunteers who had worked very hard in the weeks leading up to Convention.

The next order of business was Friday night dinner, and the atmosphere could not be rivalled. Once students had led Kiddush, everybody tucked in. It was wonderful to see so many Jewish students, all in one big dining hall, getting to know each other, and having a great time. After dinner, students filed to the manor house for some peer-led TED Talks – with each theme a surprise for the students. Students then descended on the manor house’s main entrance, where a Tisch began, filling the manor house with spirited singing, starting shabbat with an incredibly warm, welcoming atmosphere.

After dinner, and over the rest of shabbat, students were able to choose from a wide array of sessions to attend, led by their peers, sabs, shlichot, and external speakers who had come to Convention specially. Topics ranged from cross-communalism to disability activism, from Holocaust education to Israeli cultural activities - there truly was something for everyone. These sessions continued throughout Shabbat, with students able

to curate their own Convention experience to suit their interests. Among external speakers who joined us were Baroness Ruth Anderson (formerly Smeeth), the former Labour MP who was an outspoken advocate against antisemitism in Corbyn’s Labour Party.

Saturday evening gave way to a soulful and slightly chaotic Havdalah (service to end Shabbat), which itself gave way to a very chaotic but very fun evening. First, we saw the much-anticipated final round of Jewniversity challenge. After returning following an 8-year hiatus, the final of this year’s tournament was finally here. Bristol and LSE teams competed in round after round of mind-boggling questions, ending in a fierce tie break of sudden death questions. The Bristol team emerged victorious, with each member receiving a prize for their victory (as well as chocolates for the runners-up of course !!) Jewniversity Challenge was swiftly followed by the silent disco.

Finally, on Sunday morning, it was time for Conference. This is UJS’s annual decision-making event where students have the opportunity to write and submit motions and have their voices heard. They then get to argue for their motion in front of their peers, and the motions are voted on. Motions which pass become UJS policy, and this shapes the direction of UJS over the following years. This year, students debated motions of a range of topics including funding for smaller JSocs, how UJS should engage with Israel, and promoting more peer leadership on campus. To break down what went down at conference – 103 motions were submitted pre conference, 26 were discussed at conference and 25 of these passed. Despite the intense debate that was had at conference, this didn’t stop it from being a lively session, with music breaks between debate, and of course conference had to pause for a BeReal break!

Sadly, after Conference, it was time to go home and students said goodbye and bundled onto their coaches’ home, already excited for next year.

From March 20-24, UJS ran an innovative dialogue-oriented Israel/Palestine campaign across the UK centred around artwork. The “Art of Dialogue” campaign sought to provide alternative means of engaging with Israel which underscore peace-building efforts and foster constructive dialogue, as opposed to the divisive politics so often observed on university campuses.

The campaign was organised by members of UJS’s Israel Engagement team, who spent four days travelling across the country opening up deeply insightful conversations at our on-campus Israel stalls with a broad array of interested students.

Israel/Palestine artwork conveying diverse and nuanced messages featured at each of our stalls, alongside educational leaflets, a beautiful roll-up banner, and truckloads of Bissli and Bamba! Locations reached included campuses in Nottingham, Manchester and Leeds, with both Jewish students from JSocs and non-Jewish students passing by engaging extensively with our team.

The Art of Dialogue campaign also featured a series of online events, highlighting coexistence and grassroots peace-building projects in the region. Speakers from the Peres Centre for Peace & Innovation, Shevet Adam and Oasis of Peace were featured, with inspiring stories of positive intercommunal initiatives spread to hundreds of Jewish students across UJS’s social media.

UJS in partnership with Yachad hosted Zakaria Abu El-Halawah, the Field Researcher and Arabic Social Media Coordinator for Ir Amim as part of a national speaker tour. Zakaria spoke to over 130 students and visited Bristol, London, Nottingham, Leeds and Birmingham discussing issues including human rights and home demolitions, offering a Palestinian perspective on the sitution in Jerusalem.

Jewish delegates were welcomed to this year’s National Union of Students conference in Harrogate. Rebecca Tuck KC’s independent investigation into antisemitism within the Union had identified the annual conference as a major flashpoint in years gone by. After months of work on the part of UJS and Jewish students, Jewish delegates reported positive experiences at the conference.

NUS Vice President Chloe Field paid tribute to the work of UJS and opened the conference with an apology: stating “On behalf of NUS today and the past, I am genuinely, truly sorry that it has taken us so long to address antisemitism head-on. You have been let down by the very organisation that you should have been able to trust the most.”

Every so often, there are two special days in a row. The buzz builds, expectations are high, and excitement is in the air. In March this year, Purim and International Women’s Day were just that. Jewish students across the UK and Ireland were preparing Purim parties, with megillah readings, hamantashen bakes and gifts exchanges. Purim was an unforgettable day. UJS supported activities on all these campuses and many more, whilst also collating and publishing videos of female Rabbis’ perspectives on Purim. This led us into International Women’s Day. Jewish women were celebrated, and the women of the UJS team launched two campaigns – combatting period poverty and ‘Women In’. ‘Women In’ showcases women working in various exciting careers, who want to inspire and give confidence to female students to achieve whatever they set out to do.

Delegates were able to learn about antisemitism at a UJS fringe event chaired by Head of Campaigns, Faye Huberman. Manchester Student Union’s Sam Bronheim spoke fondly of her time as a Jewish sabbatical officer. UJS President, Joel Rosen described his fight against antisemitism on the left. The National Chair of Labour Students Ben McGowan spoke and stressed the importance of allyship across the student movement in the fight against antisemitism, whilst Cambridge delegate and former JSoc President Hannah Haskel brought a Jewish student perspective to the conversation. Around 80 delegates attended a UJS pub night and numerous members and friends of UJS were elected to key roles within the hundred-year-old organisation.

There’s an old joke that says that if a person’s name ends in “man”, it means one of two things – they’re either Jewish or they’re a superhero. But the links between the two go a lot further than simply names. The reason for this, as is the case with many things in Jewish history, comes from antisemitism. In the 1930s, having been barred from working in traditional print and media, Jewish writers turned to the one industry where they were allowed to work: comic books. This led to an influx of incredibly talented creatives such as Bill Finger, Bob Kane, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, Joe Kubert, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon (the stories of each would likely be their own articles). But these creatives didn’t simply sign up and ignore their Jewish roots. Instead, many of them interwove Jewish themes and stories into their characters –even though they were in many cases unable to make them explicitly Jewish due to antisemitism. Some characters even went so far as using their skills to help combat antisemitism, such as Captain America punching Hitler in the jaw before the US was even involved in the Second World War. Captain America himself is a giant middle finger to the entire Nazi ideology –with Jewish creators taking the Nazis’ ‘ideal man’, dressing him up in an American flag, and having him punch Hitler in the jaw. Spider-Man is yet another Jewish-coded hero. Indeed, some argue that the character represents American Jews processing the Holocaust, having been created 20 years after the end of the Second World War, and focusing on a character who struggles with a guilt complex, much like many Jews were at the time. Additionally, in many recent comics he frequently speaks in Yiddish and references Jewish festivals such as Hannukah and Shavuot. It’s worth noting as well that Spider-Man was also played by Jewish actor Andrew Garfield, and was shown as explicitly Jewish in the film ‘Into the Spider-Verse’. While there’s many other notable characters with Jewish roots and coding, the most famous example of a Jewish-coded character in comics is arguably the most

famous comic book character of all: Superman. Beyond his Jewish creators, Superman’s inherent character has strong Jewish connotations. His origin parallels that of Moses – though sent down from space instead of the Nile, in a rocket rather than a basket. But the parallels go even further; one of the main themes that Superman and many other heroes grapple with is the need for a secret identity as they have to mask their true self in public in order to avoid being ostracised and hated. This is much like how many Jews have historically, and still in many cases do, have to hide their identities and assimilate in order to maintain the safety of themselves and their families. In fact, going even further - Clark’s “kryptonian name”, Kal-El, is Hebrew, translating to ‘the voice of God’, much like how Jews have their English names, and their Hebrew names. Some writers have even argued that the very persona of Clark Kent is the bumbling, nebbish, brainy Jewish stereotype.

But, as Superman has been written and re-written over time, and eventually adapted into film – as many comic books fans will likely complain – he’s been altered and changed, with many of these Jewish roots being minimised or outright ignored. Modern films indeed often him as more of a Jesus metaphor, with Man of Steel even going as far as marketing the film to churches. More worryingly, even explicitly Jewish characters such as Scarlet Witch, The Thing, Moon Knight and Batwoman routinely have their Jewishness either minimised or completely ignored. Scarlet Witch had both her Romani and Jewish roots completely erased, with the

Marvel Cinematic Universe instead changing her to be Christian and “Sokovian”. The Thing had his Jewishness completely erased in the Fantastic Four films, and Moon Knight, while explicitly Jewish in the show, had his backstory altered so that his dissociative identity disorder is triggered by an abusive mother rather than being the victim of an antisemitic attack due to his father being a Rabbi. Some even argue that this new backstory ties into the antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish men being passive and Jewish women aggressive. Another example of this is how the TV show “Batwoman” focusing on Kate Kane (Batman’s gay Jewish cousin) wrote off its lead character in the second season, instead replacing her with Ryan Wilder, an original character created for the show who while representing another under-represented community, is not Jewish. But hope is on the horizon. As already mentioned, Spider-Man was shown as explicitly Jewish (albeit briefly) in ‘Into the Spider-Verse’, and Marvel have even announced that the next Captain America film will feature the debut of Sabra, a Jewish and Israeli Superhero. And both in the comics, and outside of them, we are seeing more and more Jewish characters, including recently the characters of Whistle in DC comics, a Jewish teenager who fights crime in Gotham with the help of her dog sidekick, as well as Adam Stein, an 8 year old Jewish Autistic boy who develops superpowers in the upcoming short film: Secret Identity. Perhaps the Jewish roots of so many superheroes will finally be celebrated.

Jewish characters have their Jewishness either minimised or ignored.

Against a background of grandiose skyscrapers and darts of yellow cabs, black suits and payot are as much an iconic feature of New York’s archipelagic boroughs as the winding East River separating them. Stretching from coast-to-coast, Jews have been carving their own place in American society since the arrival of the first settlers on the continent. In the darker days of world history, the Americas have been a destination for Jews fleeing persecution across the world, from the expulsion of Jews from Spain in the late fifteenth century to the influx of thousands hoping to rebuild their lives after the Holocaust. With the largest Jewish population in a nation outside Israel, Ashkenazim now make up ninety percent of the American Jewish population of the

Americas, yet it was Sephardim who were the first Jews to set foot on the continent. These first Sephardi Jews arriving with Columbus’ fleets were themselves refuges, forced to flee from their homes after the Alhambra Decree banished Jews and Muslims from Spain. Much of the early activities of Jews on the continent are a mystery, but a recent discovery by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York found Jewish genetic markers among Indigenous people on the Colorado Plateau, suggesting that Jews had married and assimilated into Indigenous Southern communities since the point of first contact.

For those arriving in the ‘New World’, the presence of Indigenous people challenged everything that European thinkers believed about the world and the people in it. In the era that Columbus sailed the globe, the Bible was Europe’s authoritative source on how humans had come to populate the world. Encountering peoples with new forms of religion, language and social organisation confounded European explorers, and whilst the early settlers heavily relied on Indigenous peo-

ple for survival in the new lands, violent programs of Christian conversion and mass displacement soon befell the Indigenous communities.

For many early Jews arriving in the Americas, the Indigenous people inspired a different sort of re-evaluation of the world. Many Jewish people drew similarities between different cultural practices in various tribes and those within Jewish tradition and looked at these societies as potential kin. Indeed, many visual and theological comparisons can be drawn between the religious practices of Jews and certain Native American tribes.

Many Jews today still remark at the visual similarities between the shaking of the Lulav on Sukkot and the parading of the Eagle Staff at ceremonial gatherings.

Indigenous people inspired a re-evaluation for many Jews.

In a thought-provoking piece, Olly DeHerrera considers the tribal nature of Judaism.

Jews assimilated into Indigenous communities for centuries.

Most notable was the similarities of tribal social structures, which many commentators at the time likened to records of the organisation of early Jewish civilization into the twelve Tribes of Israel. Indeed, the word “tribe” itself is from a thirteenth century French word created to describe the historic Tribes of Israel.

In 1837, Jewish scholar Mordecai Manuel Noah published “Discourse on the Evidence of the American Indians Being the Descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel”, and excitedly theorised on what it could mean for Judaism to re-unite these allegedly lost sons of Jacob. In modern times, it is understood that Indigenous people in the United States do not share common ancestry with Jews, and assertions about Indigenous history that seek to displace tribal history from the continent are largely viewed as conspiratorial and damaging to Indigenous people. Yet, it is possible to view the willingness of Jews to embrace Indigenous Americans as kin as evidence that a distinctly tribal identity continues to resonate within Jewish tradition.

Extensions of solidarity and kinship have not ended between American Jews and Native Americans on the continent. Throughout the 1950s, lawyer and philosopher Felix S. Cohen, whose ideas were shaped by experiences of Jews during the Holocaust, applied himself to bettering Native Americans’ civil rights. In

1953, Cohen stood at Capitol Hill to call for greater Federal accountability for the lives and freedoms of Native Americans. Here he implored America to embody the core Hebrew biblical value of “care for a stranger”. Inspired partly by his leadership, many Jews devoted time, money and energy to support and elevate the lives of fellow Native American citizens during the heated campaign for Native American civil rights from the 1950s to the 1990s. The theoretical works of Felix Cohen highlighted how both Native American and Jewish culture are foundational pillars to the modern American state, which are often deeply neglected by the façade of the American national identity.

As modern Jews in the world, it is up for debate if the word ‘tribe’ can still be used to classify the Jewish people. As identity becomes an increasing part of postmodern discourse, the question of who a Jew is takes on increasing relevance and is hotly debated in the mainstream media. The answer to this question, like anything in Judaism, is never simple. The practice of Judaism has undeniable religiosity and predication on a belief in God. Faith has delivered many Jewish people through the darkest parts of history and been foundational to the development of many other world religions. Yet, many of the most notable Jewish figures in popular culture, including Jaques Derrida, David Baddiel, Harold Rubin, and even David Ben-Gurion, have identified as either agnostic or atheist whilst maintaining a strong and decisive Jewish identity.

The matrilineal and genealogical elements of the identity also express an ethnic element to Jewish being, which has only been compounded by centuries of racialisation of Jewish people and Jewish ethnic traits. Any Jew who has faced the infamous “but you don’t look Jewish” will know that Judaism has no one race, colour, or ‘look’. Furthermore, the Talmudic and Halachic precedent for welcoming the convert and the existence of the Beit Din denies any claims that being a Jew is purely a biological status. Thus, the question stands: is being a Jew the same as being a member of a tribe?

In America, MOT (Member of the Tribe) is a popular slang term for Jews to refer to an identify each other, yet not many will earnestly consider the meaning of this. Sadly, a history of distortive academic and social racism towards tribal communities in the Americas, Africa and elsewhere has attached deeply negative traits of barbarism and blasphemy to the notions of ‘tribe’. These ideas often arose from the same schools of thought which sought to rank and classify non-Christian ethnic groups, including Jews, as lesser and inferior to white European Christians. Repeated historical attempts to racialize the Jewish identity have arisen throughout modern history, but Jews and Judaism have repeatedly denied classification and definition; this beautiful complexity is a part of why Jews have risen and thrived against insurmountable odds. In 5783 years, Jews and Judaism have undergone beautiful change, yet Jewish people should not seek to minimise the tribal beginnings of Judaism and its practices, which testify to the origins of a truly encompassing and undefeatable identity.

Judaism has no one race, colour, or ‘look’

It was roughly a year ago that Russia’s growing intolerance of Ukrainian self-determination took a drastic turn for the worst. Adding untold devastation atop an already dire situation, Russia’s attempted full-scale invasion of Ukraine launched in February last year is still ongoing, with Ukrainians putting up a formidable resistance.

As Russia struggles to maintain the momentum of its assault following a series of surprising military setbacks, Agne Kniurate reflects on the enormous human toll the war has inflicted on ordinary life in Ukraine, and revisiting cherished memories of a country she holds deeply close to her heart.

The media called February twenty-fourth, 2023, the first anniversary of the war in Ukraine. What an untruth. The war is not a year old – it is nine. Nobody has talked about it out loud it seems, but it was always there. It was never a ‘conflict’ or ‘kerfuffle’ or whatever other sugar sprinkled on the matter – it is, and has always been, a war. Now that a consensus is reached about what to call this ongoing event, I would like to see some more open discussion about the eight years that preceded it, about their real name. The occupation of Crimea in 2014 marked the real beginning of it – I was 10 and I remember the man on the radio hoping the war would end quickly, be as bloodless as possible, and, above all, not spread, so that we in Lithuania, more than 700 kilometres away, would be spared. I remember hearing stories of soldiers fighting with old sneakers and duct taped helmets, of children getting blown up by mined toys left on the streets for that specific reason, mothers and sisters in

despair, their fathers and sons on the front lines, unprepared yet determined to fight for freedom. Every news segment was a nightmare – and they never stopped. I skipped my ninth-grade spring dance to go to Mariupol. While the city stood, it was wounded. Every day, I would walk past shot-up, crumbling buildings, and abandoned blocks. A general sensation of unease filled the air despite the lovely, early spring that year. It was the spring of 2019, yet it felt more like 1946. My parents amusedly took pictures of a park sign forbidding people to ‘pick the flowers’ – as if someone would do such a thing? Looking back, I almost wish I did. A tsunami strikes twice – once as a warning and the second time destructively. Mariupol is no more, and my memories of it are now preserved in a jar, sealed tight and pickled on a shelf. On YouTube sits an unlisted video, a joking ‘vlog’ of teen-me prancing around the city, filming sights from the beach to the bleak factory buildings. Until the war

began, I debated deleting the video completely – I am forever happy that I didn’t. In retrospect, it seems as if there’s more I missed than I recorded, which is my biggest regret. How could I have known? I was blissfully unaware of the future, and now I suffer, although, is it really pain if I’m safe and sound and so far from it all?

I picked flowers in Bucha, ate delicious ice cream, and wore a button-up shirt that was way too tight for me and left a lasting impression on my skin. Another city massacred. I visited a space museum and ice cream factory in Zhytomyr – also attacked. Somehow, ice cream has so much to do with my memories, but so does summer, joy and carelessness. With every step I take, the happiness transforms into grief, every warm memory now a charred brand that feels like it will never heal. On the street I lived on in Kyiv stands the Chasidic Brodsky Synagogue, the second largest one in the city. I would pass by it every day, but I’ve never entered it. Religion was never a matter of great in

terest to me before the war began. Now I regret not having interacted with it. I used to sit in restaurants facing the building, watching people trickle in and out of it – a bar mitzvah, a wedding… I wonder how the people I’ve seen are doing today, I wonder if they stayed in Ukraine, and, if they left, what happened to their families and friends, are they safe? I’ve heard of Rabbi Moshe Reuven Azman’s humanitarian efforts. Now it all feels surreal, everything I took for granted, the sunny streets and the hustle and bustle of cars and people just going about their day. On that street, traffic jams would stretch out for hours, and, if you were especially unlucky, you’d spend more time turning one corner than at your destination.

ibly etched into my mind. It was a cold, cold winter, and nothing could take me out of the cold and sadness I felt as much as this one piece. And now I sing ‘Request the welfare of Kyiv; may those who love you enjoy tranquillity’. Back then, I didn’t like the choir, oh, what would I give to sing with them once more! What would I give to know all of the people I’ve bonded with are safe and sound! It is one thing to feel relieved knowing my classmates have mostly gotten out and are now on campuses of universities around the world, far from the cruelty of it all, but the fear caused by a twelve-monthold message delivered to my Ukrainian friend still left on delivered is a merci–less beast, interrupting all joy’s rhythm.

I used to take that road to sing in a choir, on cold days and dim evenings, listening to music – I was particularly taken by Arvö Part’s Peace Upon You, Jerusalem (Tefillah 122), and would go through periods of compulsive listening to only that one Psalm, until it was indel-

Ukrainian people are very lovely, and I’ve always felt a strong kinship with them. History, tradition and culture unite us, we understand each other even if we don’t understand each other’s tongues. They have shown me love and friendship, and a special kind of relatability no one else has been able to replicate. I adore Ukraine, its people, its vibrancy and excitement – it is the country of my coming of age, a country of unlimited stories and possibilities, unbridled potential and optimism. Its land and diversity are as unique and stunning as its inhabitants, and seeing it destroyed so baselessly kills me every day. I have turned off the news – a selfish and privileged act, but I would

have lost my mind otherwise. There’s only so much a person can take. And there’s only so much I can tell in a single article. Among the many places in the world I itch to return to, Ukraine sits on top. Once the war is won – and Ukraine will win, no doubt about it – I will run head first up my old street… and weep, most likely. I will check up on my friends, knock down doors of those who are phoneless, and take pictures, of everything, mountains of evidence that I was there, that it wasn’t a dream. Ukraine is my first true love, my coming-of-age story in every corner of Kyiv, Mariupol, Zhytomyr, Odesa, Ivano-Frankivsk, Bukovel and all the other cities and villages and fields I’ve come across. There I bloomed from an awkward young teen to the adult I have become, Ukraine shaped me, nursed me, and governed me. I long to see it achingly, torturously. I root for its success and future because I know that if any country can resist its offender, it is Ukraine. It has done it time and time and now it will undoubtedly fight to win again.

I have turned off the news to not lose my mind.

Now I regret not having interacted with religion.

The NUS opened its national conference this March with an apology directed towards Jewish students in response to the damning independent report into antisemitism within the organisation that was published earlier this year. At its annual meeting of delegates representing students from across the UK, an apology was made for the “truly shocking” accounts of antisemitism detailed in the report, while the leadership of the NUS acknowledged that they were “truly sorry that it has taken us so long to address antisemitism head-on”.

In May 2022, the National Union of Students had commissioned Rebecca Tuck to lead an independent investigation into antisemitism, the results of which were published in January. The organisation was condemned as a “hostile environment” for Jewish students, additionally, the NUS itself described the report as “a detailed and shocking account of antisemitism”. Complaints of antisemitism were found to have been consistently ignored and dismissed, often being demoted as a result of bias over the Israel-Palestinian conflict.

An additional report conducted by the charity Community Security Trust (CST) that examined antisemitism within UK university campuses identified a 23% increase in incidents in 2020- 2022 compared to the previous two-year period. Although this is a significant increase, CST maintains that the real statistic is likely higher as many university-related antisemitic hate incidents experienced by students go unreported. The report detailed that across UK university campuses, investigations into antisemitic incidents are largely characterised by slow responses, communication breakdown,

lack of impartiality and a failure to use the IHRA working definition of antisemitism, all of which contributed towards a lack of action and appropriate response when it came to the handling of allegations. Looking at instances of reported antisemitism specifically related to London universities, incidents were found to have more than doubled over the last two academic years.

To me and my fellow Jewish students the findings of these reports will not come as a surprise, rather, they illustrate the Jewish university experience with accuracy. Universities and Student Union organisations are failing their Jewish students by allowing a culture to develop in which antisemitism simply isn’t treated with the seriousness it deserves, but is rather tolerated, excused, and covered up. Students do not feel it is worth approaching their university in regard to their experiences of antisemitism because of the frequency with which they are met with hostility, defensiveness and gaslighting, so much so that this is what we have learnt to expect and anticipate. My time at university has been dominated by and consumed with dealing with incidents of antisemitism as I did not have confidence in my university to act on my behalf and so had no option but to take matters into my own hands. This is not a unique experience by any means. Continuities in the reaction to antisemitism by universities in the UK include the trivialisation of issues, the blatant disregard for the safety of Jewish students and a lack of understanding as to what constitutes antisemitism, while inadequate not-fit-for-purpose complaints procedures only serve to make matters worse. The impact of antisemitism on Jewish students cannot be underestimated - not only the initial subjection to antisemitism but also the subsequent process of making a complaint and risking facing backlash by staff or peers has an immense impact upon an individual’s mental health, leading to feelings of hopelessness and isolation. When Jewish students opt to speak out about their experiences of antisemitism, they are placing themselves in an exceedingly vulnerable position and potentially making themselves a target

of further abuse and harassment, a situation that is often worsened by the lack of support and protection provided by the university in these instances. Rather than back Jewish students, universities would rather attempt to delegitimise their claims and brush any complaints under the carpet for fear of facing bad press or being cancelled, leading to the internalisation of antisemitism by Jewish students who are led to believe that the abuse they were subject to was somehow justified or acceptable. Universities must address and acknowledge antisemitism fully and unreservedly if they are to relieve Jewish students of the burden they currently carry.

The rise in antisemitism in the UK is not confined to universities and student unions by any means, it is part of a far wider problem with a multitude of origins - appalling religious education coupled with totally inadequate holocaust education, a renewed rise in conspiracy theories and the normalisation of the coded language and imagery that allows antisemitism to present itself in disguise and makes it so pervasive. In addition to this is the platform provided by social media to celebrities or politicians promoting antisemitism and misinformation. One just has to think of Kanye West, able to reach his 30 million followers on twitter in just a few clicks, an audience numbering over double that of the Jewish population of the entire world. Contributing towards the difficulty of tackling antisemitism in a university setting is the lack of agreement as to what exactly antisemitism is. It’ s one thing for a university or student union organisation to agree to combat antisemitism, it’s another thing to agree on what it means. This is why a definition of antisemitism is such a vital tool in the fight against antisemitism, once adopted, they allow us to clearly define what is and isn’t antisemitic, something that is not always immediately obvious, especially when it comes to areas such as anti-Zionism. Combatting antisemitism isn’t just about calling it out, it’s about helping people understand what antisemitism is in the first place.

Universities must address antisemitism fully and unreservedly.

Having a strong Jewish community on campus can be enormously beneficial to students’ wellbeing. I’ve been fortunate to experience such communities at both Imperial College London and the University of Cambridge. London is a city with a massive thriving Jewish population, multiple Jewish schools, and kosher restaurants and supermarkets, in sharp contrast to Cambridge. Nevertheless, I was surprised to find Cambridge has a vibrant and engaging student Jewish community. I spoke to community leaders and discovered several reasons why that may be.

The strength of the Cambridge student Jewish community may even be a direct consequence of the smaller local community. In 1937, Cambridge’s JSoc opened their own purpose-built synagogue –which is still largely student-run to this day. Here, students come together weekly and cook Friday night dinner, at least partially motivated by the limited local alternatives.

Rabbi Baruch, the Cambridge Chaplain , points out that although this is more laborious than simply turning up to a catered Friday night dinner, it’s more likely to leave a lasting impact on the students involved: “It’s inevitable that a community you’re invested in is one you contribute to and feel connected to.” In London, by contrast, students can enjoy one of the strongest and most established communities in Europe right on their doorstep, which is hard for campuses to compete with. There’s little incentive to make your own mark on the wealth of existing options and build community spaces of your own.

The more students put into their own community, the more they’re likely to get out. Cambridge has the best of both worlds. There’s a local community

vacuum which pushes students to come together to build a space of their own, and yet, at just an easy hour-long journey from London, it’s easy to pick up kosher supplies when you need to.

In a walkable city like Cambridge, Jewish students are never that far from each other or from their community spaces. That means there’s a regular – and very strong –cohort of students gathering in community spaces, with some regular shabbat services attracting up to 70 students. This is especially important to students limited to walking on shabbat. London offers some much-loved events such as Marble Arch synagogue’s Friday night dinner, but with London students living up to 2 hours away from each other and from their community spaces, they need to be realistic about how many events they can attend.

The Jewish centre-of-gravity in London is in the north-west, and far from the university campuses. Rabbi Leigh, the Chabad Rabbi of Cambridge, told Aleph the impact this has on campus Jewish life: “In London, affiliated students – those who would probably be the most keen to foster a sense of community on campus –will understandably choose to live in the north-west of the city and commute into campus. So, the community of people living on campus are likely the less affiliated Jews.”

Terms in Cambridge are only eight weeks long, meaning students can theoretically spend more of the year at home than they do at university. Rabbi Baruch has noticed that, for many students, terms are too short to feel homesick “it’s not worth going

home for shabbat, so people stay during term time, and shabbat is the main time the community comes together.” Cambridge students typically live in one of 31 constituent colleges which, according to Rabbi Leigh, can infuse a strong sense of community. Leigh sees the collegiate environment as something students might even bring into their Jewish engagements. Indeed, Leigh actively tries to integrate the “Cambridge atmosphere” into Chabad events to attract students who are embedded in the collegiate system.

Rabbi Leigh highlighted that a strong sense of community isn’t always a good thing – spaces dominated by more affiliated Jews can leave less-religious students feeling alienated. Perhaps Cambridge offers a solution to this with a wide variety of spaces catering to a wide variety of student needs. Students can choose between orthodox and egalitarian Kabbalat shabbat services, as well as events run by the JSoc, Chabad or chaplaincy.

Saul Yardley, a PhD student at Cambridge and ex-president of King’s College London JSoc has had the opportunity to travel across the country to learn how different JSocs operate. Yardley believes there is a vibrant Jewish student life in London, but it can be hard to get involved. He said: “The infrastructure is there, it doesn’t need radical top-down initiatives it just needs support for the people that are there and making a difference.” Saul also points out that Cambridge’s reputation as a strong “jewniversity” acts as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Cambridge and London are both full of talented and passionate figures working to strengthen their communities. Cambridge has a combination of geographical, cultural, and historical factors which in my opinion has allowed for its Jewish student community to thrive.

After three years of statues being torn down, lecture theatres being occupied, and a police van set alight, it is time to say goodbye to Bristol and most importantly, Bristol JSoc. Bristol JSoc has been at the heart of my university experience, with the JSoc house being central to all things Bristol JSoc. Year after year Bristol JSoc Presidents have tested the structural integrity of the JSoc house by packing it full of students for the annual fresher’s week Friday night dinner and the Bristol Purim party, making for some of the more memorable nights at university. Given my first year of JSoc Friday night dinners (FND) was cancelled due to Covid, as JSoc President I ended up making my own first JSoc

FND. When preparing for dinner, I thought it would be best to stick to what I know. So, there I went, setting up the dinner table just like it would be at home in Finchley. A white tablecloth, knives and forks aligned, bottles of wine spread across the length of the table. Come 7:30, 140 students turned up for dinner. Accepting my fate, the tables were pushed to one side with dinner becoming self-service. Not quite like how we have it in Finchley, but an awesome evening nonetheless. So, if you are a student and ever find yourself in Bristol over shabbat, reach out to the JSoc, you will be sure to receive the warmest of welcomes, but don’t expect to find a nice shiny white tablecloth.

As Jewish students in their final year wrap up their time at university, they share their experiences of Jewish life on campus.Edward Isaacs Bristol JSoc

Being a part of Warwick JSoc has given me so much. While at university, JSoc has always been my home away from home that I’ve really appreciated.

During my first year at university, I got more involved in JSoc, joining the exec as a Shabbat Officer. In this role I was in charge of cooking and coordinating weekly Friday night dinners. This was hard work but I learnt so much about time management, and I really developed my organisational skills. I also think that I am now a master at peeling potatoes and chopping up an Israeli salad.

After my term as Shabbat Of-

Warwick JSoc

ficer ended, I decided that I still wanted to get more involved and I became the president of JSoc. This was so much fun and I was able to really make a difference and manage everything that the society did. I learnt how to manage a team and within my exec team, I came by some of the best friends that I have at university.

I’m now coming to the end of my time at university but I will be forever grateful for what UJS and JSoc have given me. I’ve met great people, had great times, learnt so much and most importantly, I’ve eaten some great Friday night dinners!

Oxford Brookes JSoc

I first became involved with UJS when I was my College SU President and needed support as a representative on the NUS NEC as a Jewish Student.

I had the privilege of becoming the first Trans* identifying person to be a representative on the Board of Deputies, eventually being elected to the Defence Division. I was given the opportunity run an LGBT+ inclusion workshop for WUJS as a UJS representative in 2014.

This is all credit to UJS and its support of students from a range of Jewish backgrounds, beliefs and political opinions. JSoc and UJS have had such a fundamental role in exposing me to new opinions, experiences and opportunities over the years.

As my student experience comes to an end and I bid farewell to UJS and JSoc I’d like to give thanks to UJS staff past and present and all students I have met over the almost past decade since my first initial involvement with UJS.

I absolutely LOVED my time at Leeds JSoc. I loved being on the bar for the committee, scandalous cooking for Friday night dinners, and the liveliest Purim parties! I really enjoyed living in a house of all JSoc people in 2nd year (Hurray for Alison, Maital and Samantha) and my favourite part was making friends with Jews I wouldn’t have met had it not been for this society. So, a big thank you to those people.

The AGM was iconic, I might have stood in front of 70 people on zoom running for education officer (who’s one job was to run Lishma) and replied “What is Lishma????” when asked in front of everyone…oops … which I now know was lunch and learn and I ran MANY. The

committee of 2021 spent so much time catching up with events that never happened during Covid that I think with being one of the Gabbais of the Hillel Minyan I spent a few weeks where I’d go into Hillel every day. During freshers of second year we even ran a JSoc welcome back BBQ, pres and a freshers Friday night dinner in one week…manic! After experiencing it myself I really think there’s a place for every Jew in Leeds. It was a really special way to meet people during Covid and Leeds JSoc is a really special society.

Shout out to Joseph Gavzey and Grace Silverstein, for forcing me onto committee. I cannot believe my time is over!

#LeedsLeedsLeeds

Glasgow JSoc

This year, I am finishing up my life at university and I can’t help but go down memory lane every chance I get.

In my first year entering university after leaving my Jewish bubble in Hungary I couldn’t help but feel a bit lost. It was my chaplains and JSoc that gave me a space to be Jewish and be my authentic self without a worry.

Through these four years my Jewish identity was shaped by

the amazing people around me, my JSoc presidents and my fantastic friends. Looking back, I feel such a sense of pride that I was part of the Glasgow Jewish society, and even more that we created such unity within the Scottish Jewish student community. To each and every one of you, thank you from the bottom of my heart and I am excited to continue this journey with all of you in my heart!

Ábel

Being part of a Jewish Society has definitely impacted my experience at university. My first year was during the pandemic, so we were limited on what we could do but Olivia (the president at the time) still arranged Holocaust memorial calls and a call with Ughyur refugees.

In my second year, I got to meet the other members in person and it was great.

Olivia did an amazing job of making it a welcoming environment, we would have FNDs at her house and had a fantastic Hanukkah party in our university’s bar. I developed friendships, even joining Aidan’s (a member of JSoc) campaign team for a student union position.

Now in my third year, the JSoc remains invaluable to me.

Our president Rheannon had gone above and beyond to connect us to the wider Jewish community of Northern Ireland, which means a lot when at university we feel like such a small group.

We have had the usual FNDs, but also a Purim event, with a few UJS visitors and the progressive link of Northern Ireland. We have been to the Orthodox synagogue for social events, and we have plans to join other Irish JSocs for a trip.

The people currently in the JSoc are absolutely fantastic, and we are always there supporting each other. I definitely hope to stay in contact with all of them after university!

Being involved in LSE JSoc has provided me with a wonderful opportunity to be part of a community of students from around the world, with diverse backgrounds and always finding ways in which we all relate to Jewish culture and identity.

Socials, weekly ‘lunchand-learns’ and speaker events on campus are always fun, and they give us the perfect space to come together when Jewish life might otherwise be reasonably limited. I really enjoyed the chance to run the society, which allowed me and others to use the platform of JSoc and our shared values to organise and participate in social impact

and intercommunal events.

It has been lovely that UJS have helped support us with events, which have included an anti-discrimination workshop, as

well as providing us with an opportunity to meet senior figures in the UK to voice students’ concerns related to antisemitism. Other highlights include the London JSoc Ball, Friday night dinners and all of the chagim events, which were organised collectively by all London JSocs, as well as hosting LSE alumnus Lord Dubs, in collaboration with LSE Student Action for Refugees, and organising a soup kitchen ran by all LSE faith societies.

I have met so many amazing people, and it has been a highlight of my university experience!

The last three years at university have been a truly amazing experience and being a member of Oxford’s JSoc was a large part of that for me. It gave me a base of friends that I knew I could reliably see every week at Friday Night Dinner, where we would always have something new and interesting to talk about.

Being president in my second year, looking back on it now, was an absolute whirlwind. Dealing with low Friday night dinner attendance; issues of antisemitism; arranging the first interfaith event since covid and organising the massive end of term party

whilst Spotify was down-but I wouldn’t change any part of it. In that term JSoc became my life and whilst it was not always easy, and not necessarily the most balanced term of my university career, the lessons I took from it have been invaluable. My experience of Jsoc has allowed me to both meet new people and really solidify the friendships that I had coming into university.

I was able to explore both religious and cultural aspects of Judaism and share this with both my Jewish and non Jewish friends. Thanks to JSoc I can now say that I’ve celebrated Shavuot

in a park, in the dark, taught a lot of drunk people the dance for Moshiach and even been on BBC Radio 5 Live.

Community is something extremely important for a person’s wellbeing and sense of place in the world. Even more so for Jews, where so much of our practice and culture is based on coming together, and being a tiny minority in a vast, non-Jewish world. I was well aware of this coming from a small community in Reading so, when I applied to Universities, I made

sure that each one had at least a small JSoc – and a small JSoc was exactly what I ended up with at Hertfordshire.

I know many people at “Jewnis”, where Jewish students can casually be counted in the hundreds. Birmingham, Leeds, Bristol, Oxford, Cambridge etc. have busy JSoc scenes and even dedicated buildings which we at Herts could only dream of. When I visited Manchester earlier this year, where they have a large Jewish student centre with a shul, study rooms and regularly provided kosher food, they couldn’t understand my wonder at it all. In a small JSoc, you don’t have much, but as a result you value it all the

more.

At Herts, I probably couldn’t name more than 20 Jewish students. But we still have lunch and learns, inter-JSoc socials and do our best to provide for the Jewish students at our university. Like many, my JSoc has been an essential lifeline during my studies. I’ve met a lot of great people and had opportunities arise which I never expected.

If you’re in a large JSoc, know just how valuable what you have is; if you’re in a small one, you’ll likely empathise with my experience; and if you’re not yet involved with your JSoc, change that – you’re missing out on something valuable.

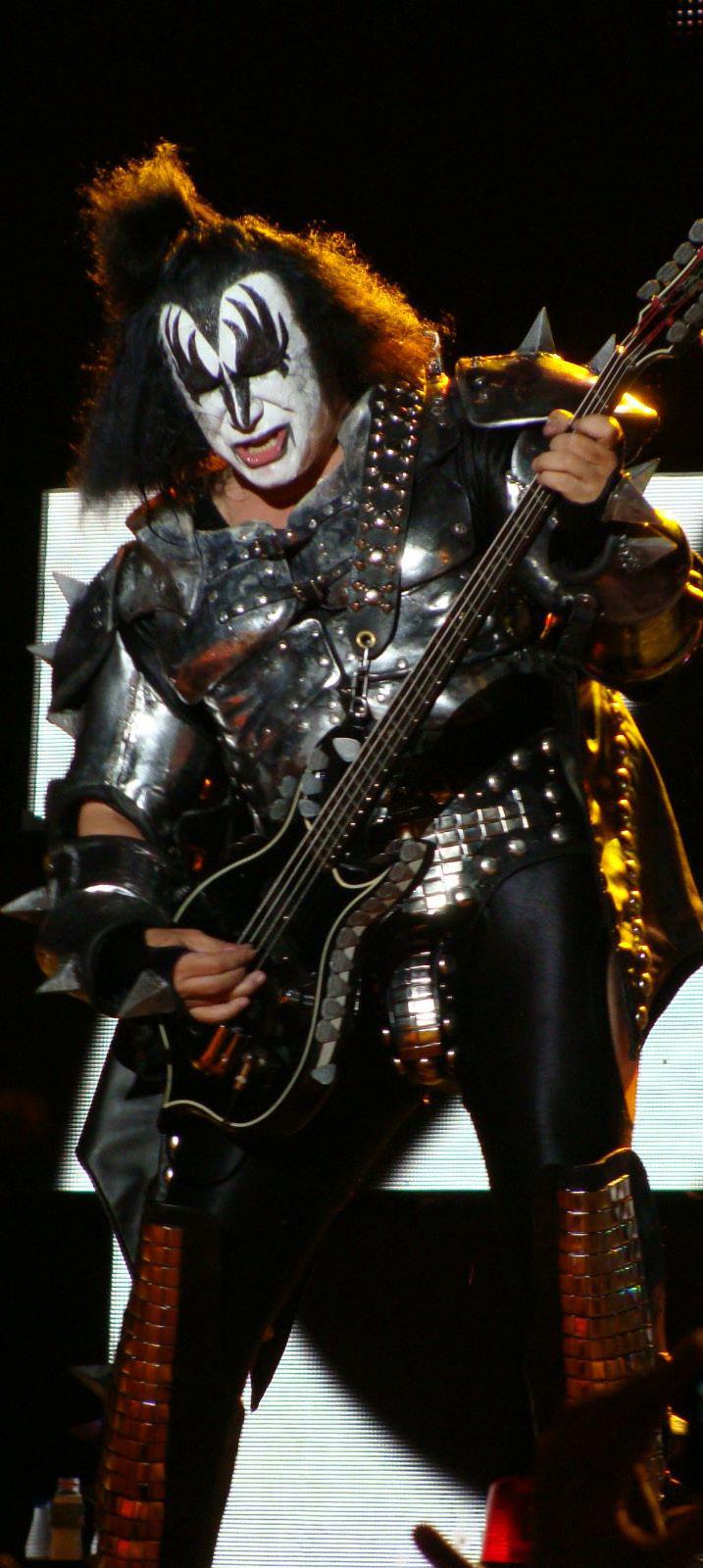

Gene Simmons, better known as a co-founder, bassist and co-lead singer of the hard rock band KISS, was born Chaim Witz in 1949 in Haifa, Israel. His mother Florence, and her brother, from eastern Hungary, survived Auschwitz, and were the only members of their family to survive the Holocaust. Simmons’ father, raised in Haifa long before Israeli Independence, became estranged from his wife and son by the time Gene turned 6, and Florence and Gene uprooted to Queens, New York, due to the financial hardship in Israel. While in America, Gene even studied at Yeshiva Torah Vodaas in Brooklyn,

before transferring to a public school. His new life in America encouraged Gene to change his name, to assimilate and give him better chances of acceptance into college, which he attended in New York. Gene developed a talent for the guitar and established several bands in his youth. In the early 1970s, KISS began to perform and gained a huge amount of traction, particularly due to the iconic stage makeup. Simmons adopted the persona of ‘The Devil’ through his face paint and even taught himself to breathe fire – to attend a KISS performance was to experience a fresh new perception of what it meant to be a rockstar. If one didn’t know any better, it would be plausible to be entirely unaware of Simmons’ Jewish heritage and Israeli nationality. Perhaps the name ‘Gene Simmons’ could be considered relatively ‘Jew-ish’, however for all intents and purposes, since Simmons left Yeshiva Torah Vodaas, he could have been an entirely assimilated Jew. After all – when considering typical Jewish professions, rockstar is usually very far down the list.

Objectively speaking, assimilation is a totally understandable process for all Jewish people. Assimilation and social integration allow minorities to have more in common with, and perhaps be less alienated by, the majority of society. Some may call it conformity to the masses, however, particularly when we observe Simmons’ case, assimilation would be totally understandable. His mother and uncle lost everything in the Holocaust because they were Jewish; he moved to a new country with a new language during his childhood because life in the Jewish State was too financially straining, and his father remained in the Jewish State and was entirely absent for the rest of his life. Following fame, assimilation would be even more appealing: if your Jewish identity is publicly known, you are exposed to a group of people with no idea of their feelings or intentions towards Jewish people. The only saving grace is that antisemitism via social media was not a possibility back then. Even more shocking is the apparent antisemitism Gene was exposed

When considering typically Jewish professions, rockstar is usually very far down that list.

Despite Gene Simmons’ Israeli childhood, Charlotte Cobb asks if he lost touch with this part of his identity.

to from his own bandmates; Ace Frehley, a co-founder of KISS, reportedly collected Nazi memorabilia which he would allegedly use to play cruel jokes on Simmons, along with another Jewish bandmember, Paul Stanley. In his autobiography, Simmons recounted an event when Frehley burst into his hotel room in a Nazi uniform and proceeded to yell ‘Heil Hitler’ into his face. While researching Gene’s life, I have been abhorred to find that as a Jewish performer, there are more documented incidents of antisemitism from his own bandmates compared to incidents from fans. This is not to say that there were not cases of antisemitism committed by fans (unfortunately an educated guess would suggest there were a fair few) however none are documented, compared to extensive evidence pointing towards Frehley’s obsession with Nazism and blatant antisemitism towards his own bandmate. It is for this reason that I am even more in awe of Simmons’ consistent public pride of both his Jewish heritage and his Israeli identity. He describes himself as

an Israeli-American, although he left the country as a child over 60 years ago. He regularly calls out other performers in the music industry who refuse to perform in Israel due to public pressure, putting his own reputation on the line for Israel, which he calls ‘his homeland’. Simmons returned to Israel for the first time since he left in March 2011, citing his busy schedule as the reason he had not returned before. In an interview with the Associated Press in Jerusalem’s Old City, Simmons told a reporter ‘I’m Israeli. I’m a stranger in America. I’m an outsider’. Simmons’ behaviour suggests he is open about his Judaism and Israeli identity despite the potential hate he may receive as an Israeli Jewish celebrity, rather than despite it. While he may not know it, his proactive stance on pride is a lesson we as Jewish students can all take – no matter our religious, political or cultural identities. Simmons does not wait for an antisemitic incident to spur on an announcement of his identity – he did not share it as a reaction to hate directed towards anyone else. Instead, he introduced himself as a Jewish Israeli rockstar from the beginning of his musical career, and while there are so many reasons why he could have chosen to assimilate (and perhaps more personal ones we cannot speculate about) he chose to take a proactive, headstrong position to make his Israeli and Jewish identities an intrinsic part of him. Perhaps his courage and respect for his own identity has encouraged fans to respect him not only as a

performer, but as an Israeli who did not lose his relationship with his homeland, and as a Jewish man who is not fearful but instead proud of his identity.

Simmons’ behaviour suggests he is open about his Judaism and Israeli identity.

A few months ago, my friends and I received the news that the only remaining synagogue in Ireland, located in Dublin, would be shutting its doors to move to a smaller, more affordable location. Upset by the news, we spent our next meeting brainstorming how we could help, each idea presenting more problems and equally as many obstacles. The discussion devolved into a debate about the cost of living crisis, then our concerns about our ability to ever have a synagogue where we live in Cork again, and finally, after a moment of silence, what a miracle it is that we all found each other. Living in Cork, our group has no easy access to the built-in community of a nearby synagogue, with each of us instead having to find each other in order to create any semblance of a community. Despite this initial difficulty, we formed an active Jewish Society, with all of us being dedicated members of both the campus and broader Cork community. We became representatives of Judaism to the interfaith council at the University College of Cork and involved with the Cork Jewish Community, and we organised educational events and fundraisers for the whole of Cork, being sure to benefit the most

vulnerable members of our community. Within our Jewish community, over the course of a few months we went from being peers in a society to a small yet loving family. Our weeks are punctuated by family style dinners, group study sessions, an unfathomable amount of inside jokes, late nights and early mornings all spent together, fighting for, and encouraging each other every step of the way. To describe them as my lifeline would be an understatement. Sitting together around my kitchen table, watching my friends eat the meal I spent my afternoon labouring over, pushing more food onto their plates when their mouths are too full to protest, I cannot help but think about my family at home as my heart overflows with love for them. I immigrated to Ireland from the United States only recently, and I still

find myself overcome with homesickness more often than not. Over the past few months, however, these friends have become my family here, I lovingly refer to them as my “Ireland family” as opposed to my “America Family,” both of them supporting me in different parts of my life. Ianna, Malachy, and Melissa are all in a choir together, so the three of them intermittently breaking into song is the soundtrack to our meal. More often than not Abbie and Al are squabbling like siblings over someone they went to school with or some other topic which has been a moot point for well over a decade. Shoshana, Reuban, and Dante also tend to descend into an impassioned discussion about politics, conspiracies, or whatever piece of media they’ve most recently consumed, each taking turns to briefly dominate conversation while the other two listen with genuine interest. Ruby and I take turns sharing stories with the group about home, our own lives, or whatever bizarre gossip we have most recently heard about those who frequent the same spots as us. The familiar chaos brings me more comfort than anything else ever could. There is an almost meditative element to the overlapping voices, chorus of

We went from being peers in a society to a small yet loving family.

Ainsley-Kay Rucker reflects on the components of Cork’s Jewish student community

laughter, and mingling scent of perfume and a freshly baked loaf of challah. It’s in these moments where I remember something my mom first told me when I was little: “Friends are the family you get to choose.”

Our community continues to thrive, not just because we are cooperative members of a society, but because we have become a family. Even without the community centre of a synagogue in Cork, we still have each other and work every day to foster a sense of community and familial love with every new member of our society. To an extent, it is almost entirely due to the necessity of active community building that the Cork Jewish community has become so closely knit. This is the most crucial factor in supporting a community once you have established it: not just to meet but to gather, giving what you have to give while taking what you need from your community members. For myself and my fellow students, sometimes all we have is each other, and so we all lean on each other to stay standing.

A triangle is the strongest shape; the three sides equally distribute weight across each other with the smallest possibly perimeter. In a similar vein, there are only three elements needed to build the strongest possible community, anything more is superfluous. The first key element of any community is faith. Faith in each other, in yourself, and in whatever it is that brings you all together. In our case, it was this faith which brought us all together initially, pulling us from most walks of life across the University and city as a whole. Without it, there is an incredibly slim chance we ever could have all met. The second element, determination, is crucial for any community, but to Judaism more so than others. On more than one occasion we’ve had our Erev Shabbat meetings interrupted by being told to put out candles, been faced with demeaning questions from our peers, or had to sit through lectures where professors spread misinformation about Judaism, all while having to put our own faith second to succeed in the University environment. Nevertheless, as determined as ever, we move not past but through these obstacles, appearing on the other side still with each other and resilient in our faith. The final element needed to make a thriving community is not a community centre, but food. What is a communi-

ty if not those who would fight to break bread together? Every time we sit together to eat, we share stories and the wisdom which comes along with them. We speak, laugh, listen, learn, and help each other. There is something so sacred, almost ritualistic, about all gathering together simply for the sake of being together and to support each other. Without the designated community centre of a synagogue, these meals have become all the more important, taking the power of a community centre out of a physical location and instead placing it within the individual, allowing for the community to exist wherever and however its members do. This is not to imply a community centre in and of itself can be the heart of a community – no matter where you are or what circumstances you are under, the true centre of a community is always within its members, but for us in Cork we do

not have the comfort of placing it external to ourselves. This is active community building. We must tend to the hearth within ourselves in order for the community to not only thrive, but exist at all. Our shul has no choice but to thrive, because our only option is to seek each other out and pass the torch amongst ourselves: we have nowhere to put it down except each other’s hands, and a watched fire never goes out. There is a certain level of comfort which comes along with knowing your whole community is not dependent on your own unending faith and determination, but simultaneously there is no better feeling than being a member of a community where the resilience of its members is so tangible. With a balance of these things, the effort becomes worth it. It isn’t always easy for us individually because it will be easy for us collectively as long as we all keep moving forward as a community, as a family, and as a shul. A triangle is the strongest shape, and as long as we maintain our faith and determination, we will still sit down together every week to share a meal and share our love within the community we made.

Our shul has no choice but to thrive.

The mikveh sat still and clear as I shivered, freshly showered and awaiting entry. I stared into that clear pool, imagining who I would become when I emerged. I saw so many futures laid out before me; Shabbat dinners with my friends, celebrating festivals at the synagogue, sending my children to Hebrew school, a real vision of the Jewish life I had fought so hard for. I stood there petrified to enter the waters and start anew- terrified that I hadn’t learned enough, my Hebrew was too shaky, I couldn’t quote the Torah front to back, that I wasn’t ready. And yet, I slipped into the pool- it was lukewarm, I continued to shiver- and took a deep breath.

On the first submersion, the blessing said is “Baruch atah Ad-nai eloheinu melech ha-olam asher kidshanu bi-tevilah b’mayyim hayyim,” “Blessed

are You, G-d, Ruler of the Universe, Who makes us holy by embracing us in living waters.” (Mikveh-going readers may notice that this is not the traditional blessing, but rather a slightly poetic rewording. While I would love to claim this was a purposeful choice, it was indeed the version written on the card to the side of the pool.) The second dip came much more easily, with a moment of breathing be-

tween. Another blessing, shehecheyanu, with the sh’ma for good measure, and the final time going under. On this dunk, I spent a good deal longer under than the rest. I wanted to really feel the change I expected when I broke the surface. After all, I was becoming a new person. At last, my lungs began to demand a return to the world, and I came back to reality. On stepping out, I noticed how, despite being elated, I felt distressingly similar to the person who entered. The same hair, although it was now dripping down my blouse. The same eyes in the same face. This is the thing they don’t tell you in conversion classes: the mikveh hadn’t taken away the imposter syndrome, but I had faith it would fade with time.

Converting to Judaism is not something anyone takes lightly. The pro-

The thirst for truth is something so characteristic of Judaism.

cess takes years, and requires a major upheaval in your daily life, sometimes even moving far from your original home. Students are required to practice all aspects of Judaism, to learn what it means to take on mitzvot. It is overwhelming at best and exhausting at worst. Nothing has ever been more worth pursuing in my life. With every class, I learned a new topic to explore, a new rabbit hole to fall deep into. Being an English major came surprisingly in handy in my journey to become part of the people of the book. My library grew weekly when my innumerable questions were answered with recommendations on where I should search next. This thirst for truth is something so characteristic of Judaism. How fitting for the process of joining the nation to require a deep love of knowledge and a heart open to new understandings of the world.

We are commanded by the 207th mitzvot to love the convert. In the Talmud, Shevuot 39a, it is said that the souls of all Jews, including future converts, were present at Sinai. This is a vital teaching of our faith. There have been so many who, once learning of my conversion status, treat me with such love and grace. They either ask me no questions, or wonder lightheartedly about what the process was like. Then again, there are those who begin to ask me if I converted through the ‘right’ movement, tell me I am culturally appropriating, or ask invasive questions to try and parece out if I’m ‘really’ Jewish. Did we not read the same Torah? Do we not love the same G-d?

It appalls me truly how people find the intimacies of my conversion process to be any of their business. I generally do not share my conversion status with strangers, hence the anonymity of this article, and this is for many reasons, none of which are to trick born Jews. I

feel as if my journey is my own to share, and I shouldn’t be forced to explain my ethnic and religious history with anyone before I am ready. As much as we might hope that converts be treated exactly the same as all other Jews, the reality of the matter is that humans are full of curiosity. No matter how pure hearted, it can still be exhausting to feel in constant need of proving my ‘Jewishness’ to others around me. I am eternally grateful for those who see my Jewish soul, and know it was up with theirs on that holy mountain top. One of the kindest examples of one of my born-Jewish friends protecting me happened over the course of a few erev Shabbat evenings. There are several members of our JSoc who know how I came to Judaism. We had a newcomer arrive, and stay for the semester. He once asked me what my shul from home was like, and I said very casually “my family wasn’t religious growing up.” My friends didn’t contradict this. Later on, I thanked them for not exposing my past, and one said to me, “it is a white lie that does no harm, and revealing it would hurt you more.” Those words expressed exactly my feelings on the origins of my Jewishness. I am so grateful to have people in my life who know who I am and are willing to help me keep my boundaries in place.

In Ruth 1:16, Ruth makes a promise to Naomi; “where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your G-d my G-d.” Like Ruth, I made a commitment to Hashem and to all of Judaism, to follow the rules and traditions, and to make every moment holy. It can be difficult to explain to those who didn’t convert how monumental this feels. Really, more than

anything, it’s an end to years of wandering and a warm welcome home.

It has been about 9 months since that day- a year in June. A year of keeping Shabbat, of attending services, of keeping kosher. I am even preparing for my bat mitzvah (and my Hebrew is improving with every lesson)! Daily prayer helps me to grow my relationship to myself and to Hashem. Living my life happily, richly, and Jewishly brings me more joy than anything I could ever imagine. I see Hashem in nature. I see them in the love of my friends and family, and in our beautiful community. Knowing my day will follow a pattern makes even the hardest day surmountable. Setting apart Shabbat to connect back in with myself and my loved ones is so freeing. I often am asked if the restrictions are difficult, and to that I say I did not convert not to be Jewish, rules and all. I love everything about being Jewish, and I wouldn’t give it up for all the crab legs in the world. The feeling of pretending fades with every mitzvah, and I affirm my Jewish identity every day through these little blessings. I know who I am, and I am grateful every day to have made it to that mikveh. To be Jewish is a thing of beauty. Baruch Hashem.

I wouldn’t give up being Jewish for all the crab legs in the world.

Converting to Judaism is not something anyone takes lightly.

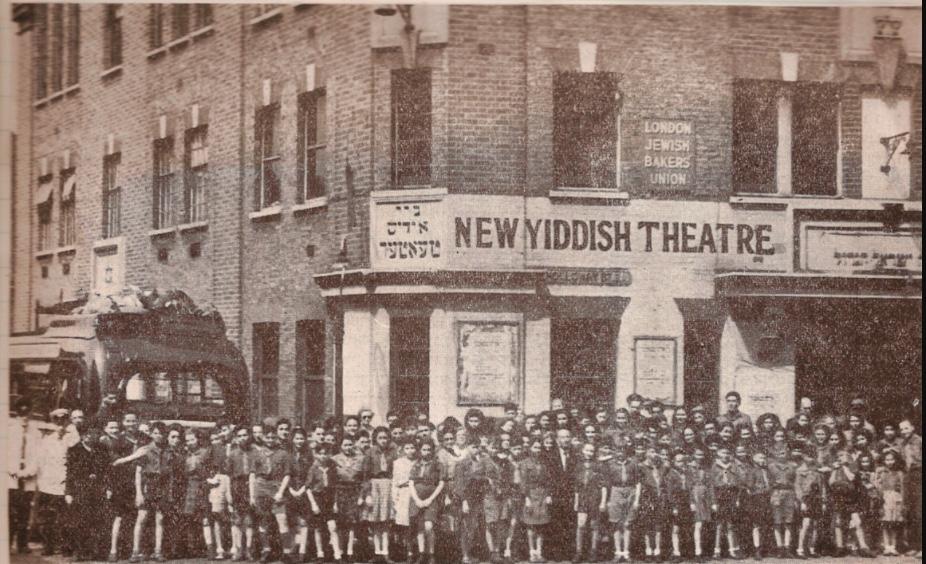

If you’re a young Jew on the left, it’s likely that you’ll hear a language you thought had been confined to history spoken once again. Its sounds evoke a bygone era. Its literature transports you to an unrecognisable world. To speak it is an act of subversion, breathing life into a language that our oppressors looked to exterminate.