Editor in Chief

Molly Hatcher

Managing Editor

Ella Kroll

Editor in Chief

Molly Hatcher

Managing Editor

Ella Kroll

Copy Editor

Dailey Jackson

Writers

Olivia Bassett

Faye Decker

Zaklina Grgic

Inga Gudmundsson

Razeen Kanjiani

Ethan Thomas

Brittney Waldheim

Molly Williams

Creative Director

Sam Nash Riggs

Layout Editor

Emery Wahlen

Layout Team

Brock Corbin

Paige Garvin

Erin Ideker

Maheen Lakhani

Eva Legaspi

Julia Rothermel

Mia Smitherman

Brittney Waldheim

Cover Design

Leah Kartsonakis

Andres Pina

Secretary

Clare Smith

Faculty Advisor

James Schulte

Thank you for reading this year’s issue of the Georgia Landscape Magazine. In August of 2022, I joined in with a handful of other individuals to help James Schulte resurrect the Georgia Landscape Magazine. I always had a passion for writing and researching, but never had an outlet for writing about my interests in landscape architecture. Fortunately, under the guidance of Professor Schulte and last year’s Editor-in-Chief, Jeffrey Bussey, not only did I discover this outlet, but many other students did, too, in forms of writing, graphic design, photography, and illustration. To see this magazine continue to gain support and grow has been one of the most rewarding experiences and I could not be more proud

of the hard work and dedication of our team. Since last year’s reemergence, more students have joined, giving them the opportunity to express themselves through creative writing. In this way, we have created a multidisciplinary study of the landscape to share with the CE+D community. I can only hope that it keeps growing into something every student can experience. While reading, you will see articles of all types, ranging from the landscape architect’s role in climate change and interviews with scholars and professionals, to how landscape design is applied in Minecraft and more. I would also like to take this opportunity to express how thankful I am to have such a great team to work with. The Georgia Landscape Magazine would not exist if we didn’t have a team with such determination and passion. I thank all of the staff and contributors from the bottom of my heart. I hope you enjoy this year’s publication and thank you for your continued support and readership.

Sincerely,

Molly HatcherI am Sonia Hirt, Dean of the College of Environment and Design at UGA, and I am confident that the built environment professions provide a lifetime of rewards. Our faculty members are passionate about helping the next generation of professionals succeed, and they provide a depth of knowledge that is difficult to find anywhere else. Collaborative studio spaces allow students to thrive and actively engage with faculty and peers, and our unique location in the heart of UGA’s historic North Campus provides exciting opportunities for outdoor learning. The 2023-2024 academic year was a great success for our college and the BLA program. This summer, the American Society of Landscape

Architects and the Landscape Architecture Accreditation Board received STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) designation from the Department of Homeland Security. This designation officially recognizes the high degree to which our students study science, technology, and mathematics. Our BLA program enrollment increased by 10 percent in 2023, and we hope to see continued growth. We also successfully fundraised $1 million, which resulted in a newly endowed professorship, several new scholarships, and graduate fellowships. In February, 63 of our 3rd-year BLA students secured summer internships with 40 firms, which is a great achievement and demonstrates our students’ dedication and commitment toward their academic and professional pursuits. At the CED, we are optimistic about our future. Our faculty is preparing and advising a new generation of professionals who will be leaders Prepared to Shape our World!

Sincerely,

Sonia HirtThe fields of landscape architecture and horticulture are often riddled with prevailing ideas and norms that propagate a garden design ideal that features beautiful and ecologically beneficial specimens. Customarily, this function of a landscape is attached with its responsibility to foster an ecosystem of mutual harmony among the various members, be it insects, humans, or the climate. This ideal entails the creation of a landscape that is ecologically reminiscent of the past and aesthetically recognizable. Perhaps the most celebrated way of attaining this ideal is through the use of a pollinator garden; an idea that has gained momentum with private gardeners over the past couple of decades.

This communal effort to protect our pollinators is not lost to those who are fierce advocates of healing the fractured ecosystem. One such organization is the State Botanical Garden of Georgia (SBG). The State Botanical Garden has played a major role in increasing curiosity and knowledge on the subject, and their Georgia Pollinator Plants of the Year Program particularly stands out in purpose and impact.

“This program started in 2021,” said Heather Alley, the conservation horticulturist at the SBG working to conserve endangered and rare native plants. “It is to help people choose high-performing plants that are great for pollinators.”

Every year, four plants are selected, and each of these fit into either the spring bloomer, summer bloomer, fall bloomer, or Georgia native categories. The plants selected for the spring, summer, and fall categories can be natives or non-natives. But just what is a high-performing plant, and who selects it? Naturally, a committee that is composed of a diverse group of opinions and backgrounds, including plant nursery owners, professors from the department of entomology at UGA, a representative from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a representative from Georgia Power, representatives from the SBG, and representatives from the UGA Extension that specialize in plants and insects make these selections.

“They’re selected based on the committees’ observations of pollinators utilizing the plants when they’re in flower; it’s also expected that they do not become invasive,” Alley said. Interestingly, an added challenge to the selection process comes from how difficult it is to find them. Understandably, for plants that are difficult to find in the trade, and plants that have less than a handful of nurseries growing them, demand often outpaces the supply. This is a valuable lesson that was learned after the selection of the 2021 bloomers. Unfortunately, in Georgia it is hard to find many nurseries that grow both native and non-native plants.

“There’s a significant shortage of a lot of landscape plant material, native and non-native, but there’s a very noticable shortage of natives,” Alley said.

To remedy this, the Mimsie Center conducts a native plant sale every fall and prepares a list of retailers that have plants of the year in stock. Even so, a shortage in nurseries that grow these plants in Georgia leads to outsourcing to other states, such as South Carolina. The selection of bloomers for any given year occurs two years prior. For instance, the 2024 plants were selected in December 2022 and announced in January 2024. This allows growers a year to stock up and prepare for the energized and galvanized crowd of gardeners who are prepared to expand their pollinator gardens—or are ready to try something new.

The annual rotation of selected pollinators is particularly attractive because it gives gardeners an opportunity to add to their collection in a relatively short amount of time and, if they are new to the practice, time to experiment growing bloomers and elaborate upon their understanding of dealing with diverse types of pollinator plants. This is the impact the program has had on the community. It has provided, for sake of analogy, a bingo card that gardeners want to fill out with the four new plants each year and, as Alley said, “people really gravitate towards those choices.”

There is also room for expansion; after about two years, this program is looking to have a wider impact throughout Georgia so that gardeners throughout the state can include these plants in their gardens.

“Next year, we’re going to try partnering with other botanical gardens around the state in hopes that they will put these plants on display so it can have more of a statewide impact,” Alley said.

Though still within the confines of Athens, one of the planting beds to the west edifice of the UGA Center for Continuing Education & Hotel is far enough to deserve a mention. It boasts a showing of the 2023 plants complete with cards showcasing their information and properties. Readers are advised to catch a glimpse of the planting come Spring.

The humanistic aspect of the impact that this program has had has been tremendous, but the impact on pollinators, arguably, is of even greater importance. The goal of returning pollinators to their glory days has been arduous, but even so, efforts have been extensive and results realistic. What this program does is offer up this goal to the wider public.

Unwittingly or not, the public has helped in reestablishing these ecosystems in their backyards. The biggest challenge of this effort is to cater gardens and plantings towards those pollinators that are specialists. These pollinators search for pollen that can only be found in a particular species. The antithesis of the specialists are the generalists. As the name suggests, these pollinators are able to collect pollen and nectar from a wide variety of bloomers. Therefore, it is wise to cater to the specialists because, more likely than not, the generalists can collect pollen and nectar from that species as well. Though the Pollinator Plants of the Year Program does not specifically select bloomers that cater towards the specialist bees, the plants selected do tend to native bees, hummingbirds, moths, and butterflies.

Illustrations: Paige Garvin 2023 pollinator plants, featured in order: Blue wild indigo, wild bergamot, aromatic aster, coastal plain joe pye weed

Some species that are selected belong to a genus that supports many of the specialist bees. One such example is found in the plants selected for 2024: Erigeron pulchellus ‘Lynnhaven Carpet’ (Robin’s Fleabane). The genus Erigeron supports 9 species of specialist bees in the Eastern U.S. The other winners include Monarda punctata (Spotted Horsemint) in the summer category, Eurybia divaricata (White Wood Aster) in the fall category, and Hamamelis virginiana (American Witchhazel) in the Georgia native category. This time around all four plants are native to eastern U.S. and, as has been the case in the past, they also support various moth and butterfly species, such as the Pearl Crescent butterfly. These bloomers have inflorescences ranging from white to pink to yellow. However, these are not luminous colors, but are more so gray tints of their respective colors which ensures a harmonious transition through the year while also maintaining a complementary relationship with the surrounding landscape. They vary in their inflorescence types and forms which provides excellent contrast and a necessary antagonist to their complementary aspects.

The 2024 plants of the year were announced in late January and the program now boasts an adequate selection to observe and witness the change over the years. The Georgia Pollinator Plants of the Year is a successful program, aimed at increasing knowledge and availability of pollinator plants that, in turn, increase the populations of pollinators found in Georgia. Analysis of the use of the natural landscape and resources found within has revealed the grim future that we are bound to approach and encounter; though anthropogenic extinction–extinction caused by human activities–has been carried out thousands of years, its recent acceleration is alarming. Amidst these woes, faith in community and an understanding of the world and its functions is necessary to maximize conservation efforts and this program is one of these local efforts that provides us with comfort and confidence to face the consequences of our actions and avert their realization.

Illustrations: Paige Garvin

Pearl crescent butterfly

White wood aster Spotted horsemint

Illustrations: Paige Garvin

Pearl crescent butterfly

White wood aster Spotted horsemint

Most of us have been there: you start registering for classes and the electives you wanted are either full or have a time conflict. For Janeth Garcia Torres (BLA’18 MHP’24), that exact scenario played out in the fall semester of her senior year. After failing to find any landscape architecture electives that aligned with her interests, she was left two electives short. A friend of hers, Gabe Harper (BLA‘18), advised her to look into the historic preservation courses offered through the historic preservation program. She ended up enrolling in Intro to Cultural Landscape Conservation and Rural Preservation, both taught by Professor Cari Goetcheus (MHP ’96). Janeth recently recalled that: Taking these courses completely changed my outlook on what landscapes have to offer. As a BLA you learn to manipulate and change landscapes. I have a strong passion for design and thoroughly enjoyed my BLA coursework. However, I discovered that my favorite aspect of the design process was the preliminary site analysis. I enjoyed studying landscapes and how they functioned. I had a genuine interest in exploring the various locations associated with each project and dedicated a significant amount of time

Janeth and Margot are the only current students who have this unique connection as BLA turned MHP students

to researching the historical context of the landscapes we were redesigning. Whenever a challenge or issue arose within a project’s landscape that required alteration, I was always motivated to uncover the underlying reasons behind its existence. It wasn’t until taking Professor Goetcheus’ Intro to Cultural Landscape Conservation course that I realized my interests fell into a field of study. Janeth met with Professor Goetcheus (MHP ’96), who also graduated with a BLA degree from Utah State, and after speaking to her about the historic preservation field, she felt her excitement and interest grow, especially in regard to the study of cultural landscapes. It was amazing meeting someone who had such a deep passion for - and extensive experience in - a field that I was just beginning to explore. I had never imagined that my interest in learning about the history and functionality of landscapes could turn into a profession. It was the most exciting thing that could have happened to me in terms of career possibilities!

Margot McLaughlin (BLA ‘23, MHP ‘24) came to historic preservation in a similar manner. After

Margot McLaughlin and Janeth Garcia on the 2024 MHP Charleston Visitattending a CED Lecture on a significant downtown location, Hot Corner, Margot, who was halfway through the BLA program, pivoted from considering a masters degree in urban planning to one in historic preservation. Growing up in a historic neighborhood in Atlanta, Margot is no stranger to preservation conversations, and feels that her BLA and MHP degrees will compliment each other well. Margot said recently, In many of my design projects, the initial researching phase was something I invested heavily in and I really wanted to understand what is and what was present on the site before in order to better inform my design. I’ve learned that designing in a way that is sensitive, respectful

“Recognizing that the American experience is diverse and multicultural, I strongly believe that the representation of American landscapes should reflect this richness”

Janeth Garciaand responsive to the context and history of a place is so important and is something I want to always prioritize. I think you can approach a variety of subject matter from a design perspective and having the background in landscape architecture has helped me to do that. I learned a lot about sustainability and got a sustainability certificate in my undergrad, so having that foundation made it easy to realize how preservation fits into that bigger picture of creating healthy and strong communities. Out of the twenty-four current Masters of Historic Preservation (MHP) students, Janeth and Margot

McLaughlin

are the only current students who have this unique connection as BLAs turned MHP students. When asked about how they foresee their career post-graduate school going, whether it will lean more towards landscape architecture or historic preservation, both

“I’ve learned that designing in a way that is sensitive, respectful, and responsive to the context of the history of a place is so important and is something I want to always prioritize” Margot McLaughlin

Janeth and Margot seem optimistic. Janeth stated, “My dream job would be working for the National Park Service in their Cultural Landscapes Program.” The opportunity to be actively involved in the preservation and management of these landscapes would be incredibly fulfilling and rewarding for me. I am equally enthusiastic about advocating for diversity within cultural landscape preservation. Recognizing that the American experience is diverse and multicultural, I strongly believe that the representation of American landscapes should reflect this richness. It is crucial to ensure that all voices and perspectives are included and celebrated in the preservation of our cultural heritage. By promoting diversity in cultural landscape preservation, we can create a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of our shared history and identity.

Margot

at a hands-on demonstration learning about various construction methods

Janeth Garcia and other classmates observing Park Hall for the Historic Preservation Design Studio course

Margot

at a hands-on demonstration learning about various construction methods

Janeth Garcia and other classmates observing Park Hall for the Historic Preservation Design Studio course

When you think of landscape architecture, the first thing that comes to mind probably is not a video game — even more so, that video game most likely isn’t Minecraft.

Directly from the American Society of Landscape Architects website, landscape architecture is a profession that “...involves the planning, design, management, and nurturing of the built and natural environments…It involves the systematic design and general engineering of various structures for construction and human use” (ASLA-About). As practicing landscape architects, we are expected and trained to investigate all social, ecological, and environmental conditions, as well as the cultural aspects of the existing landscape. And based on that analysis — understand and design landscapes that are cohesive, and productive for desired outcomes.

Seems daunting right? When you think about the practice of landscape architecture in-depth, it seems impossibly broad. How are we

supposed to do all of these analyses with time, budget, and resource constraints while striving to create a landscape of such grandeur? Time and time again, designers create and implement spaces that complete these daunting tasks, and once again, our awe and fascination are rekindled with our profession, and we are driven to do the same.

How does this tie into a video game then? The answer is simple: imagine if we could be designers in a world with no real-world constraints — a place where designers could come together to let their imaginations flow, test their ideas, and make their personal ethical and design priorities tangible. That is the reality for a handful of University of Georgia’s College of Environment + Design students.

Walk into the CED 3rd-year studio on any given day and you will see students refining designs, studying, reading, rendering, and working towards completing whatever assignment lies in front of them. But on some days, when the workload is low and there is time to relax, you will find a few students playing the well-loved game of Minecraft.

In the spring of 2023, one CED student, Tommy Chambers, started up a Minecraft Realm, an online world that could only be played by people who were added, and invited a handful of other students in his cohort just for fun. I joined about two months after the Realm had started, and once I joined, the world was practically deserted. Students had played for a while but built their

bases— where they resided and kept resources — disjointed. Everything was haphazardly built around a huge lake. When I came in, I could tell that the original intention was for there to be a bustling community — but something hadn’t quite worked. I chalked it up to communication being sparse and students just playing as they would in an individual private world, and not fully together with one another.

Over the summer of 2023, the existing server died down. Many students were interning with firms and spending their time gaining professional experience or were at home with their families. A large majority traveled to Croatia on the CED Study Abroad program studying together while a few others went on the CED West Coast Study Away to road trip and sketch together down the coast — and when it was time to come back to UGA for the Fall 2023 semester, the question of what to do with the Realm arose - continue it and rebuild together somewhere else, start a new Realm entirely, or close it? Collectively, we decided to start fresh, but with one specific goal in mind: build relatively close in proximity to one another to create a community space that would rival the likes of some real-world locations.

We all learn about walkable communities, green infrastructure, urban design, and community planning in our various studio classes, and we strive to see our practice and ideas come to life. In the real world, it might be years before any of us see anything we have personally designed come to fruition, but here in our Minecraft Realm, it took merely days. We built around a central location — the Realm’s spawn point — and built up a small base for new players when they joined the Realm. After a few weeks, we broke ground on our town center, which was to be comprised of a Town Hall with meeting spaces, a plaza, spaces for players to create businesses to trade goods out of, plantings, and a Villager trading center, all encompassed by a fortified wall on top of the largest hill in the region, and within short walking distance of everyone’s bases.

The sprawl of bases in the 3rd-year CED Minecraft server is small, as you can see in the aerial imagewe built homes in clusters near the town center, near spawn, and a body of water– deliberately, to create a genuine feeling of community. We pooled and shared our resources and we drew plans by hand to design our town center - Tommy built the town a protective wall,

Molly Williams broke ground on the Town Hall, and the rest of us graded the land by digging out dirt and mining away stone to create a flat landscape. On the site, we distinguished the separation between parceled land with colored wool blocks to be claimed by other players and cut pathways to later be replaced with brick. Real-world practices were implemented into this simple video game; zoning, grading, concept designing, and collaboration.

We build with the intention of creating a community while also keeping our style in mind. Our collective world has become a beautiful patchwork of varying aesthetics, which could not be truly conceived in the real world. Molly Williams, a player on the server, noted that one of her favorite parts of the server has been seeing everyone’s play styles shine. Some players choose to build more community-centric while others prefer to flesh out their homes. With this in mind, both Molly and fellow player Everett Wayman spoke about the fact that we create these builds within our shared world with unique designs that are all sourced from

materials found in our surrounding areas. Our color palettes are chosen based on the location of the build, and in turn, maybe we can focus more on this strategy in real-world practice. I cannot help but think that the players are so passionate about this Minecraft Realm not just because we love the game, but because we want so badly to get out into the world and make our mark on it. We want to change the world around us, make it greener, make it more diverse, bolster up the community, and create a cohesive landscape - and since we physically cannot now, we do it here, together, and for a small price of just $24 for the desktop copy of the game.

It is so simple, yet so intriguing, to look at this world, created by students, and see it as a window into all of our futures. We want to have the chance to make an impact on the profession and in the spaces around us, and while we are limited now - we do what we can here, and we dream in real-time, just simply in a blocky, Minecraft world.

The name Leah Crist Bush doesn’t have many results when searched on Google. Her name doesn’t hold much recognition. Most people don’t have a clue who she was. Despite her anonymity, Bush holds an important role in the history of the College of Environment and Design, the University of Georgia, and the field of landscape architecture at large. I was connected to Leah Myers, Leah Bush’s great-granddaughter through the Archive Atlanta Podcast and was able to gain insight into some information that her family has held onto to provide a glimpse into the life of an incredible woman in our field.

Now you may be wondering, who was Leah Crist Bush?

Leah was the first woman in the southeastern United States to graduate with a degree in landscape architecture. Bush graduated from the University of Georgia in 1933, back when UGA was the only university in the Southeast that offered a degree in landscape architecture, long before the College of Environment and Design was even a thought. She was the only woman in a graduating class of fifteen students and was the president of the Landscape Architecture Club at the college. Bush graduated from college in a time when mainstream local papers still reported on women as being less capable than their male counterparts. When she graduated, the Atlanta Constitution chronicled the feat, saying she “mastered engineering, art, chemistry, physics, architecture, botany, horticulture, and liberal arts in preparation for her degree in landscaping, which seems rather an ambitious program for a mere slip of a girl who is essentially feminine.”

Thanks to Bush’s curiosity and determination, many women have gained the ability to find their passion in landscape architecture. In pushing the boundaries of social acceptability, Bush is responsible for allowing so many other women to have the opportunity to follow in her footsteps as landscape architects. When Leah Crist graduated from college in 1933, the Atlanta Constitution reported that her degree in landscape architecture was not influenced by her father’s career, a fact that her great-granddaughter disagrees with. Leah Myers, Bush’s great-granddaughter, has no doubt in her head that Bush became a landscape architect due to the environment (no pun intended) she was raised in.

When the elder Leah was born, her father worked with some of the most famous people in the business. He was “on the ground floor of something great,” Myers said. What Myers is referring to is her great-great-grandfather’s work in Piedmont Park with the Olmsted Brothers who designed Central Park, one of the greatest and well-known parks in the world. Young Leah Crist Bush watched her father assist in constructing modern Atlanta through his work in Piedmont Park and in Druid Hills, another Olmsted creation, in which an entirely new neighborhood of the city was created in what was hundreds of acres of undeveloped wood.

Leah Crist Bush was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1911. She was raised in a home that still exists today in the West View subdivision, which was laid-out in 1910 by Solon Z. Ruff, the civil engineer also responsible for laying out the affluent and notable Ansley Park neighborhood in 1904. Similar to Ansley, Westview consists of streets laid out leisurely in a curvilinear form with roundabouts and traffic triangles, surrounded on all sides by craftsman style bungalows. It is no doubt that the superb design of Leah’s childhood neighborhood, paired with the career of her father, had a hand in shaping her view of the landscape. Bush was the daughter of Nelson Crist Sr. and Victoria Crist, and she had a brother, Nelson Jr. Nelson Crist Sr., was a notable horticulturist from Walden, NY. According to Bush’s great-granddaughter, Nelson brought the family to Atlanta because of his career. He worked in both architecture and landscaping and was associated with Robert Cridland, a well-regarded landscape architect from Philadelphia, PA. Cridland was hired to work on projects in Piedmont Park, Westview Cemetery, Grant Park (and the Atlanta Zoo), and the Druid Hills development. Piedmont Park and Druid Hills were also both built using plans created by the Olmsted Brothers of Massachusetts, the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, and Nelson Crist worked alongside them as well. The Olmsted brothers were who ended up convincing Crist to stay in Atlanta, and it was there that Nelson and Victoria started their family. Nelson Sr. was the superintendent of Piedmont Park and from 1910 until the mid-1920s, Crist kept a tree nursery in the park and planted a notable White Ash and several Pin Oaks.

A snippet from Leah Crist Bush’s UGA yearbook.As superintendent of Grant Park, Nelson was also the author of “Battle of Atlanta: Story of the Cyclorama, 1919” a publication about the battle of Atlanta for the popular attraction that was the Cyclorama located within the grounds of the park. Nelson Crist Sr. was superintendent of Grant Park for 12 years until 1926 when he was made manager of the nursery and landscape department of the Empire Nursery and Seed Co. Today his name bears an annual award for outstanding achievement that has been awarded by garden clubs around Atlanta since 1957.

Much like her father, Leah Crist was on the precipice of her own greatness. After she graduated from Girls High School in Atlanta in 1929, she attended and graduated with a B.S.L.A. from the University of Georgia in 1933 as the only woman of the fifteen students in her graduating class who studied Landscape Architecture. At UGA, she was in Phi Kappa Phi, the Zodiac (secretary of Zodiac in 1932), and was vice president of Landscape Architecture Club. Her senior thesis was a master plan for the Frank Neely Farm along the banks of the Chattahoochee River. While she was in school, she worked closely with H. Bond Owens, who was then only a professor before becoming the influential Dean of the College of Environment and Design. In Athens, Leah met fellow Georgia student Harold Bush. In March of 1935, two years after graduating college, Leah and Harold were married in Atlanta. Leah and her husband spent the rest of their lives residing on a farm in proximity to her childhood home on the Westside of Atlanta.

The Bushes were both principals in the landscape architecture/surveying firm of Bush, Steed, and Boyd, which they started together soon after their marriage. Leah Myers stated that the couple worked on a mixture of residential projects in addition to larger-scale planning projects. Most of the residential projects were concentrated in the Morningside neighborhood in Northeast Atlanta.

Newspaper clipping of Bush’s achievement for women.

One of the firm’s most notable projects was a plan for Jekyll Island off the coast of Georgia. Bush was widowed in 1974 and lived until 1989, when she died at Wesley Woods Rehabilitation Center in Druid Hills, GA, only a week before her granddaughter’s wedding. A few years later, her great-granddaughter was born and named Leah in her honor. Though the two Leahs never met, they are forever connected as well-educated Georgia Bulldogs and as women involved in the world of design.

Jane fell in love with academia and took a position teaching at Salem College in Winston-Salem, NC, and then at Kennesaw Junior College when it opened its doors in 1966. During her time at Kennesaw, she finished her doctoral dissertation and married a fellow academic, Daniel Fagg Jr. In 1968, Dr. Jane Fagg moved to Arkansas with her husband and they both took positions at Lyon College (now Arkansas College). She went on to receive her Master’s degree in history from Emory, and taught in Atlanta Public Schools while taking summer classes at the University of North Carolina. Dr. Fagg was immensely proud of her mother, Leah Bush, her career, and the opportunities that she opened for her family. Leah’s other daughter, Marion, was the valedictorian of her class at Emory and became a kindergarten teacher in Atlanta Public Schools. Marion still lives in Atlanta, near Emory University. When Dr.Fagg died in 2008, as a part of her estate, she left a $500,000 endowment to the College of Environment and Design in the name of her mother, Leah Crist Bush. Besides the Bush endowment, Bush lives on through her great-granddaughter Leah Myers. Myers, who was more than happy to share the story of her kin, is also a University of Georgia graduate. Although she didn’t go through the College of Environment and Design, Myers carries on the family legacy with design.

Leah’s legacy lives on today through her family and an endowment that bears her name. Besides her design work, Leah Crist Bush was a mother to two daughters, Marion Bush Senkowski and the late Dr. Jane Bush Fagg. Leah passed down a legacy of education within her family and ensured that both daughters were highly educated, with both of the Bush girls being graduates of Emory University in Atlanta.

Green Roof Garden at Geography-Geology Building, photographed by Shira Brown

Green Roof Garden at Geography-Geology Building, photographed by Shira Brown

Upon graduating from high school, my overarching career ambition centered around making a meaningful impact on our environment, both at the local and global levels. As I’ve gone through college, navigating the myriad of paths to achieve this goal has proved challenging. While many careers, such as environmental consulting, forestry, biology, and environmental law contribute significantly to creating a more environmentally conscious world for all, there’s a growing field often overlooked—landscape architecture. This dynamic profession has the potential to play a crucial role in mitigating climate change and fostering environmental well-being. So how can we as landscape architects achieve this? Let’s take a look at some techniques that contribute to the goal of mitigating the impacts of climate change and how we can use these in future projects. One of the big ways that landscape architects help developers make environmentally conscious decisions is our management of stormwater. We spend a lot of time thinking about the impacts of the built environment on the flow of the water cycle, which is crucial to ensure a healthy climate. Low-impact development– a land planning and engineering design

approach to manage stormwater runoff as a part of green infrastructure– stands as a key pillar in landscape architecture. The tools used in low-impact development play a crucial role in climate change mitigation. You may not notice these techniques at first, but I bet you can identify several examples throughout your day-to-day walk through the neighborhood, your city, or your campus. These include modern techniques like rain gardens, bioswales, and permeable pavements, which have evolved over time to effectively address environmental challenges. Rain gardens, designed strategically to capture stormwater runoff, offer a range of benefits, from reducing runoff and preventing soil erosion to supporting water conservation and biodiversity. Bioswales, exemplified across the UGA campus, act as vegetated ditches that filter pollutants, slow down water infiltration, and contribute to groundwater recharge. In our engineering class here at the College of Environment and Design, Professor Schulte took us on a walk to show us some examples of bioswales and rain gardens here on campus. Landscape architects are also adopting permeable pavements as a smart solution, allowing water

to infiltrate through porous surfaces and reducing surface runoff. For example, rather than using a solid concrete slab for a sidewalk through a courtyard, we could opt to use gravel or permeable interlocking pavers which allow water to soak through into the soil rather than running off into an off-site drainage system. In contrast to traditional impermeable pavements, permeable pavements contribute significantly to groundwater recharge, flood prevention, and overall water quality improvement, making them a valuable eco-friendly element in urban planning and development. Sustainability is another big aspect that landscape architects, as well as many other industries across the globe, are honing in on. Sustainability is in the spotlight due to environmental awareness, consumer demand for ethical products, and a growing understanding that it’s a catalyst for innovation. Within the field of landscape architecture, a focus on energy and carbon efficiency has led to the integration of practices geared towards this goal. Incorporating sustainability can be as simple as utilizing local resources rather than importing materials in our designs. It can also mean exciting new strategies to create more environmentally friendly landscapes, even in urban settings. Notably, the increased incorporation of green roofs stands out as a significant strategy, contributing to improved energy efficiency and carbon reduction. Green roofs feature vegetation and soil layers and enhance insulation for buildings, thereby reducing the need for heating and cooling while also addressing stormwater management. While it can be difficult to implement green roofs to existing buildings, there are plenty of examples of how this can be done, including the Green Roof Garden project here at UGA that sits atop the Geography-Geology building. This is a great example of urban agriculture initiative run by

students in order to grow food and conserve native plant species. Building off of this concept, the discipline also actively addresses the heat-island effect the elevation of temperatures in urban areas compared to their rural surroundings primarily caused by human activities and modifications such as impervious surfaces and infrastructure. Landscape architects can reduce this effect by strategically designing outdoor spaces with features like tree canopies and reflective surfaces, contributing to cooler urban environments. All together, these practices demonstrate the role of landscape architects in promoting energy efficiency and carbon reduction, aligning our work with broader environmental conservation objectives.

As I’ve navigated my journey to understanding impactful environmental careers, landscape architecture has become a hidden gem—an underestimated field with incredible potential. Exploring the fascinating world of landscape architecture, I’ve discovered that low-impact development, with its tools like rain gardens, bioswales, and permeable pavements, are a great tool to fight against climate change. These strategies have evolved over time, showing how committed landscape architects are tackling environmental challenges both locally and globally. And it’s not just about the techniques; there’s a real emphasis on energy and carbon efficiency in landscape architecture. Green roofs and sustainable construction practices aren’t just trendy terms; they represent tangible measures through which landscape architects can contribute to a more sustainable world. It makes me proud to see examples of these practices on my campus at UGA and inspires me about the potential of landscape architecture to make our world safer and more sustainable for future generations to come.

Volunteer tending to the Green Roof Garden at Geography-Geology Building,

photographed by Shira BrownBachelor’s, Master’s, and then…Ph.D.? Haven’t you had enough learning by now? And what is a Ph.D., after all? Let’s take a closer look at Ph.D. students and candidates in the College of Environment and Design and get to know a bit about their research interests.

Zaklina Grgic

The College of Environment and Design has a relatively new doctoral degree program in Environmental Design and Planning. A few students join the program every year and start their research journey. Before joining a program, students locate the main professor in their research interest with whom they will work for the next few years during their Ph.D. studies. The student proposes the idea of research, which forms and changes during the Ph.D. In our program, Ph.D. students join upon completion of their Master’s degree and usually, some work experience, which also reflects in the different age groups of Ph.D. students who decide to join the program.

The Ph.D. program can be done in a traditional way if you are fully immersed into doing a Ph.D., or a non-traditional track if, for example, you are working full-time. Those who do a Ph.D. on a traditional track are usually assigned positions of research or teaching assistantships. Every Ph.D. program has two steps: being a Ph.D. student and becoming a Ph.D. candidate. The first two or three years are dedicated to the coursework at the CED. Ph.D. students, in general, take 8000- and 9000-level classes. Our program has mandatory core courses that cover topics that are the foundational base for training new generations of academic researchers. Some of the core classes in Environmental Design and Planning include History and Theory, Research Techniques, Technology, and Analysis and Issues. Apart from these core courses, students take Doctoral Research courses with their main professor or others, and they take many classes at other departments, depending on what helps them form their research topic. Ph.D. students must form their doctoral committee, which is usually four to five professors from the CED, other departments at the University of Georgia, and external professors or professionals. When the coursework is done, the student takes Comprehensive Exams and defends a Doctoral Thesis Proposal. Those two events are key points, and if passed, the student is admitted into candidacy, and the official role changes to be a Ph.D. candidate. This phase lasts

another few years, and the focus is on conducting robust research using different research methods. Ph.D. candidates often take on roles as Teaching Assistants, start writing papers for academic journals, and present at conferences.

Upon completion of the program, Ph.D. degree holders can decide to work in academia and ultimately become professors, or can choose to work in the industry as a professional. They can do both at the same time, too; there is no real limit in terms of options. Since November 2023, three of our PhD students graduated:

“There is no real limit in terms of options”

Juncheng Lu, with thesis on “The Impact of Urban Landscape Development on Stream Ecosystems in the Southeast Piedmont: Impact Mechanisms, Watershed Management Tool, and Practical Implications”

Jungho Ahn, with thesis on “Measuring the Adequacy of Affordable Housing From Inclusionary Zoning on the Atlanta Beltline”, and

Marsha Anderson Bomar, with thesis on “Can Education Create a Paradigm Shift in Transit Usage by Building Lifelong Loyalty Among Young Transit Riders?”.

Now, let’s debunk some of the common myths about the program and the people in it. Here are some of the thoughts of the Ph.D. program from Bachelor’s and Master’s students in CED:

“PHD IS JUST LIKE DOING A DOUBLE MASTER’S DEGREE”

“PHD PEOPLE ARE NOWHERE TO BE FOUND; THEY ARE ALWAYS HIDING”

Ph.D. is nothing like a Master’s degree. Master’s degrees are larger cohorts where you all take essentially the same courses, do coursework and readings assigned by a professor, and ultimately do a Master’s thesis as a one- to two-semester project. In the Ph.D. program, you are in charge of designing your path and your Ph.D. thesis is a product of years of studying the topic. You study the ins and outs of the topic, which is justified by obtaining a ‘Doctor’ title in the end.

“YOU’RE DOING PH.D.; YOU ARE SO SMART!”

They are not hiding; they are busy! Ph.D. students have to juggle many things, and there is little time for anything else. It is known that a Ph.D. becomes your life, and there are jokes about a Ph.D. thesis being the baby someone cares for. Also, a Ph.D. is very

isolating as everyone is doing a different topic, so you don’t really have a cohort of people with similar tasks as one does during Bachelor’s or Master’s studies.

“PH.D. PEOPLE ALWAYS HAVE SOME HIGHLY ACADEMIC RESEARCH THAT I DON’T EVEN UNDERSTAND WHAT IT ENTAILS”

Even though it can be nice to hear, the truth is that a Ph.D. is much less about intelligence and much more about consistency, motivation, and organization. You can do a Ph.D., too, if you really want it and if you are always curious to learn more.

“Ph.D.

people always have some highly academic research that I don’t even understand what it entails.”

Well, it shouldn’t be like that. The point of Ph.D. research is not to change the world or make a Nobel-prize-winning discovery (great if it leads to any of those, though!). Rather, the point is to bring a tiny bit of knowledge to the existing body of literature and your area of research.

Hometown: Esfahan, Iran Ph.D. student in Spring 2024 Doing research on connection of sustainability, historic preservation, and technology Must-read book: The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History (Kostof, 1991)

Hometown: Tehran, Iran Ph.D. student started in Spring 2022 Doing research on urban vibrancy measurement in college towns Must-read book: Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space (Gehl, 1971)

Let’s hear from some traditional track Ph.D. students and candidates at the CED

Hometown: Juiz de Gerais, Brazil

Ph.D. student started Doing research on restoration and how interact with different Must-read book: Stream Restoration: Principles, Practices (The Federal nteragency Stream Restoration Working Group, 2001)

Hometown: Baku, Azerbaijan

Ph.D. Student started in Fall 2021 Doing research on urban greening practices and the evolution of public space in post-socialist Baku, Azerbaijan. Must-read book:Baku - Oil and Urbanism (Blau and Rupnik,

Hometown: Changsha, China Ph.D. Candidate started in Fall 2018 Doing research on over-tourism problems in world heritage site of Suzhou Classical Gardens

Hometown: Wuhan, Ph.D. Student started Doing research visual quality in Must-read book: of Great American (Jacobs, 1961)

Carvalho de

Almeidade Fora, Minas started in Fall 2023 on differenthowstreampeoplestream projects Stream Corridor Principles, Processes, and Federal I 2001)Restoration

Hometown: Zagreb, Croatia

Ph.D. student started in Fall 2022

Doing research on pathways to affordable housing for young people in Zagreb, Croatia

Must-read book: In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (Madden and Marucse, 2016)

Hometown:Udaipur,Rajasthan,India

public Rupnik, 2019)

Hometown: Shanghai, China

Ph.D. Candidate started in Fall 2016

Doing research on changes in the open public space of China built form

Must-read book: Public Places-Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design (Carmona et al., 2010)

Wuhan, China started in Summer 2022 on measuring the in street space book: The Death and Life American Cities

Ph.D.CandidatestartedinSpring 2021Doingresearchonredefiningbuffer zonesforprotected heritagesitesinIndia

Must-readbook:ManagingWorld HeritageSites(LeaskandFyall,2006)

Hometown: Wuxi, China Ph.D. Student started in Fall 2022

Doing research on remote sensing of urban vegetation and scenario prediction

Must-read book (journal here!): Urban Forestry & Urban Greening

Hometown: Wuhan, China

Ph.D. Student started in Summer 2022

Doing research on measuring the visual quality in street space

Must-read book: Mapping Urbanities: Morphologies, flows,possibilities (Dovey, Pafka, and Ristic, 2017)

With summer break approaching, there is nothing I dread more than the questions from relatives.

“So, what's your major?”

“What is landscape architecture?”

“Could I pay you to mow my lawn?”

“Do they teach you how to trim bushes in school?”

The answer is always no.

Every student, at some point in their BLA/MLA journey has had to answer these types of questions. It's not necessarily degrading, but it is tiring to be asked these things knowing the rigorous workload, importance, and complexity of our major. There are many other questions I would rather answer like...

“How did the line get so blurred?”

“At what point did we branch from gardeners and landscapers?”

“What can we do today as CED students to further establish our major on campus?”

Humans altering their environment has existed since the beginning of time, but the practice and term “landscape architecture” is relatively recent. The practice of landscape architecture is rooted in late 17th century to early 18th century Europe, where designers were commissioned for elaborate garden landscapes, often for royal, religious, or government sites (Think LAND 2510).

Perhaps this is where the connection to gardeners was first formed. However, the term “landscape architect” was not coined until 1828 in On the Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy by Gilbert Laing Meason. The term was then adopted by several other stewards in landscape design, eventually leading to the founding of The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1899. By the 19th century, the profession had to adapt to cities in America with rapid growth rates at a large

scale. Here is where the father of our beloved major, Frederick Olmsted (with co-designer Calvert Vaux), took the reins on re-defining our responsibilities. ‘Landscape architecture’ encapsulates design, ecology, landforms, planting, water, and hardscape as well as collaborative work with architects and urban planners. This remains the professional title in the face of constant change in both style and interdisciplinary requirements.

The first college to offer a degree in landscape architecture was Harvard University in 1900, furthering the development of the field and research within it. The University of Georgia followed by offering classes starting in 1928, and establishing the School of Environmental Design in 1969. This school was modified to fit a wider range of interests by becoming the College of Environment and Design in 2001. The CED was the first new college established at UGA since 1969 when its former name was created. This timeline puts into perspective how “fresh” our major is and how long it took from the coining of the term to having 53 programs available across 30 states in our country. One thing through it all has remained the same:

So what is landscape architecture today and why should we spread awareness? The way I always describe it for those dreadful small talk conversations is this:

Landscape architecture is the architecture for everything surrounding a building.

Though it usually gets the job done, this is just the tip of the iceberg for what we do. Most of you reading this are well aware of what landscape architecture entails, but speaking more often about what our major does is a way we can educate people.

According to ASLA, landscape architecture is the planning and designing of a variety of outdoor environments with an emphasis on sustainability, circulation, function, safety, aesthetics, and social impact.

It's pretty straightforward, yet there seems to be a lot of confusion surrounding it. To be fair, I did not start at UGA as a “Landie” nor had I ever heard of the major. Watching my freshman roommate in the CED bring home cardboard models every week did not help me understand what her major was. My first year I was on a path in Forestry, but despite my passion for science and nature, the limited opportunities for creative input caused me to rethink my decision. After long talks with my old roommate, I took a leap of faith. That’s how I ended up here, in a perfect mix of everything I love, now busting all the landscape architecture myths I used to believe.

So, no, contrary to what I thought freshman year, we are not gardeners or landscapers. However, it is important in our field to know plants: their mature size, soil, water, and sun requirements, and hazards. It’s not all about aesthetics for us. Each plant is specifically selected for functionality, sustainability, ecological impact, and longevity within the environment before beauty. We do not install or maintain the plants ourselves. Occasionally a landscape architect will oversee construction and installation, or check in on the site after a couple years, but mostly there are site visits and client meetings outside of office work. There's a lot of behind the scenes that people don’t realize, whether that’s calculating stormwater runoff, engineering the site grading, making cost estimations, or CADing up a base plan (“CADing” [cah-ding] verb: using the AUTOCAD computer program for accurate 2D plan drawings).

We handle the “not-so-fun” stuff to make sites that leave a positive impact on the community and environment. We’re not just artists either. Though visual representations play a large role in how we convey our designs, there’s a lot of practical thought that goes into each design choice like safety and accessibility standards to adhere to the Americans with Disabilities Act. And boy let me tell you, we do not just design backyards. There are so many projects in landscape architecture of different scales, functions, and requirements; the possibilities are truly endless! I used to take for granted how many outdoor spaces we design. Think golf courses, national park trails, college campuses, football stadiums, vacation resorts and more!

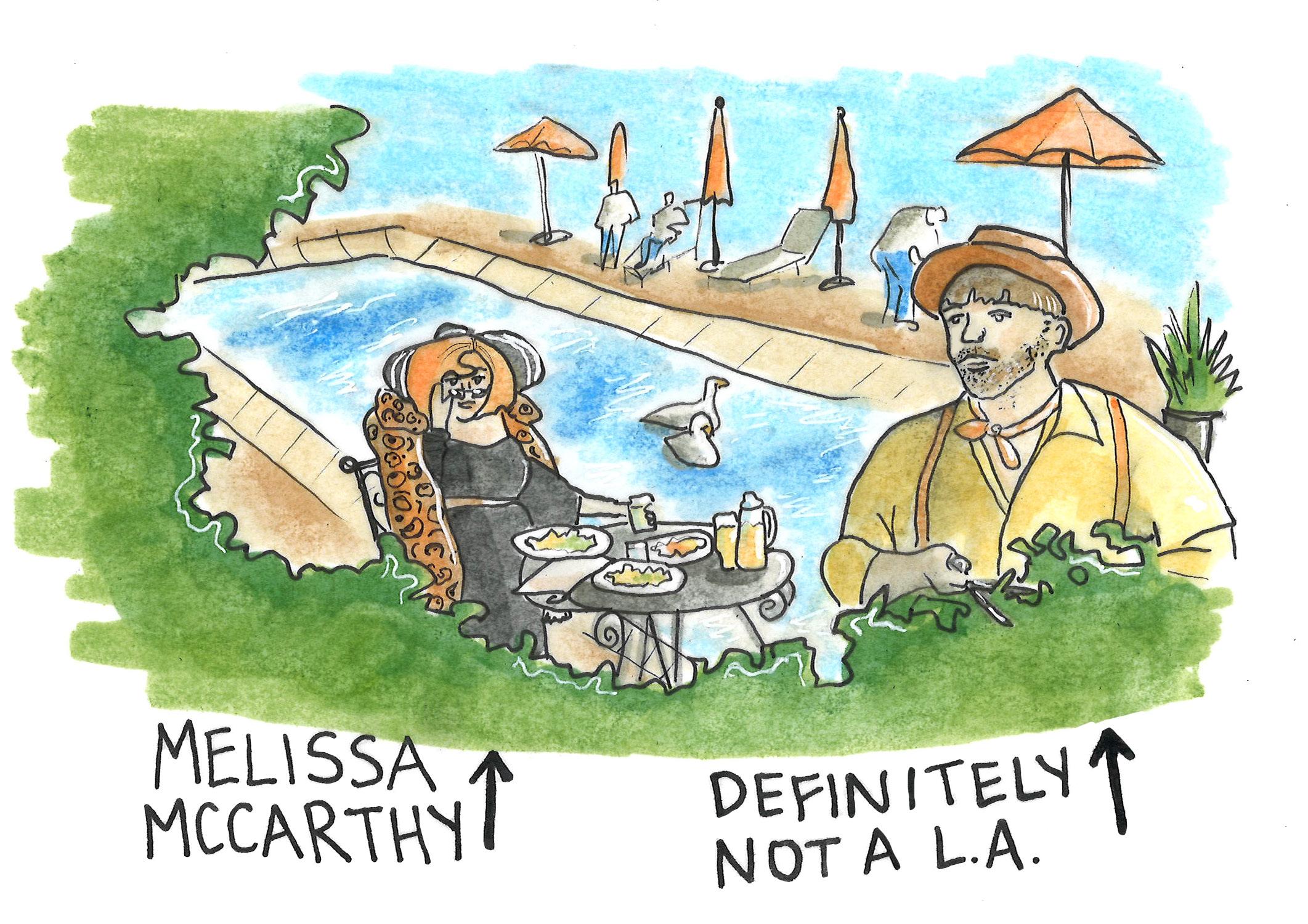

Landies, raise your hand if you’ve ever felt personally victimized by Booking.com’s advertisement from the February 2023 Super Bowl. For those lucky enough to have missed it, the “Somewhere, Anywhere” ad follows Melissa McCarthy traveling to different resorts. In one scene, a man is trimming a shrub with large shears. She sings “A fancy hotel with a sexy gardener” and the man promptly responds, “Landscape architect!”

A moment of silence to process.

Perhaps this is one of the factors that perpetuate L.A. myths. I was speechless when I first saw this, if they had just switched the words it would’ve at least been accurate. Knowing that it was viewed by millions, the advertisement grew so unpopular in the world of landscape architects that ASLA released an article addressing it. Several

L.A.s have commented under the Youtube video of this ad, explaining how they are not surprised by the misinformative depiction. If you scroll far enough, you may even see a comment from me…

Instances like this in popular advertisements and media could be partially to blame for our myths. I remember it aired shortly after completing my first semester in CED. I was so disappointed and almost discouraged knowing so many people had seen it, a feeling I would experience again later that year.

The endless possibilities in our field are juxtaposed with a general lack of awareness from the public. As a CED ambassador, I felt let down after seeing a shortage of interest at First Fall Look for incoming freshmen. I love my major, but there needs to be more information readily available and accessible to unknowing prospective students. Though we can't change the world's view, there are many ways on a college campus to combat these misconceptions and educate students about our major. A strong presence at all UGA engagement or career events is a vital first step. Including a presentation on what landscape architecture is (bust those myths!), briefing over the required classes, bringing in visuals of student projects, and showcasing alumni at these events can help incoming freshmen see first-hand the work we do and the opportunities in the field. The updated CED ambassador

program is a great start– I think each year it will only grow and attract more students. Furthermore, we need to always be vocal about landscape architecture. Take the time to explain to your roommate what you're doing in the Jackson Street Building most nights. Point out plants and impressive sites around Athens to a friend, start your own Instagram portfolio, and wear your (very limited) choice of college merchandise. Always be proud of CED!

Be proud if you’re a gardener too, but that just isn't us.

Despite some barriers to widespread understanding of our work, the profession is making great strides today, and is quickly gaining awareness. With increasing environmental health issues like climate change and global urbanization, the need for sustainable and environmentally conscious designs has become even more vital to our landscapes. Recognizing the demand for innovative solutions, landscape architecture has recently been designated as a S.T.E.M. major (science, technology, engineering, and math) – and rightfully so. Our strict schedule demands extensive knowledge in multiple subjects to accommodate its interdisciplinary nature. The knowledge we learn today can help solve real world problems tomorrow. Students today are the future. We are the future.

Now, more than ever, is our time to impact the world. It's time to show why our role is so important to every part of the world’s landscape.

Even your grandma’s backyard.

The art of sustainable design in residential landscapes weaves together aesthetics, functionality, and environmental consciousness

Navigating the complex world of residential architecture, I find myself standing at the intersection of innovation and environmental consciousness, eager to put to practice the transformative principles that shape our homes into resilient sanctuaries. As students of landscape architecture, we are at the threshold of innovation, armed with the wisdom that design is not merely an aesthetic choice, but a responsibility. Focusing on two key pillars— stormwater management and mindful selection of site elements—we delve into the innovative approaches that designers, architects, and homeowners are adopting to create landscapes that not only captivate the eye but also serve as stewards of our planet.

As we embark on this exploration of sustainable design, I invite you to be inspired and informed, to envision residential landscapes as more than just a plot of land to decorate- as an innovative canvas for resourceful living. Together, let us reimagine nature and design, where the designed beauty of our surroundings goes hand in hand with natural processes.

Gone are the days when rainwater was hastily directed away from our homes. Today, landscape architects are embracing a more symbiotic relationship with precipitation, turning raindrops into a valuable resource rather than an inconvenience.

In the heart of stormwater management lies the philosophy of embracing the flow. Harnessing traditional impermeable surfaces, such as concrete driveways and patios, are being reconsidered for porous alternatives that allow rainwater to seep back into the earth. These innovative surfaces allow water to percolate through, replenishing the groundwater table. Porous paving acts as a proactive stormwater management tool, especially in residential areas where space is at a premium. “Code requirements for impervious surfaces mean we need to utilize unpaved spaces wisely, porous pavers help us reach both design goals while staying within code” says SWH

Founder and Principal, Stephen W. Hackney. Rather than burdening municipal stormwater systems, these permeable surfaces absorb and detain rainwater, lessening the strain on traditional drainage infrastructure. The result is a landscape that is not only visually appealing but actively contributes to flood prevention and erosion control.

Contrary to common misconceptions, porous paving is not high maintenance. In fact, these surfaces often require equal or less upkeep than traditional pavements. The permeable nature of the materials minimizes standing water, reducing the risk of ice formation in colder climates. Additionally, the longevity of porous paving systems is comparable to conventional pavements when properly installed and maintained. These eco-friendly pavers do still benefit from periodic care to ensure their optimal functionality and longevity,

Incorporating pervious paving into residential landscapes is a progressive step towards sustainable design.

Here are several examples of how they can be seamlessly integrated into various elements of a residential property:

Transform the typical impermeable driveway into an eco-friendly statement by opting for pervious pavers or permeable concrete.

Pervious pavers, whether made from concrete, gravel, or other porous materials, can be used to create charming garden paths.

Integrate pervious paving around rain gardens or bioswales. By using permeable materials, you seamlessly merge these water management features into your landscape design while maintaining a cohesive and natural look.

Furthermore, we’ll navigate the intricate world of site materials, where the choices we make extend beyond mere aesthetics. From recycled hardscape elements to native flora that tells the story of the land, these materials serve as the palette with which we paint our renewable goals for the future.

Stephen W. Hackney believes that “from a residential perspective, hardscape is way more important than focusing on planting”. Choosing materials that are sourced locally not only minimize transportation-related

energy consumption and reduce carbon emissions but also is an easy way to support regional economies. Selecting materials that are durable and have a longer lifespan is another way to include an economic and environmental mindset. Materials that resist weathering and degradation will require fewer replacements over time, reducing not only the overall negative impact but as well as saving the consumer money.

Opting for native and climate-appropriate vegetation is a crucial step in promoting biodiversity and ecological

resilience. These plants have evolved to thrive in local conditions, requiring less water, fertilizer, and pesticides, thus minimizing the ecofootprint of landscaping practices. Additionally, selecting non-invasive species prevents the potential disruption of local ecosystems. Responsible plant choices not only contribute to the longevity of the landscape but also foster a harmonious coexistence between the natural world and human habitation. It’s a mindful approach that transforms residential spaces into thriving, environmentally conscious ecosystems, offering beauty without compromising the delicate balance of the surrounding

environment. In the past, the prevalence of using pestresistant, non-native, and ornamental plants in designing landscapes was a common practice, driven by the desire for visually appealing and low-maintenance outdoor spaces. However, decades of this practice has brought to light the potential ecological dangers associated with this approach. This shift in perspective underscores the evolving awareness within the field of landscape architecture, encouraging a more ecologically responsible approach to residential and public green spaces.

The Sustainable Sites Initiative (SITES) is a comprehensive program developed by the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at The University of Texas, the United States Botanic Garden, and the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The SITES initiative focuses on promoting sustainable and regenerative practices in landscape design, construction, and maintenance for various types of projects, including residential landscapes.

SITES provides a rating system and certification process that evaluates the sustainability of landscapes based on a set of criteria covering areas such as soil health, water conservation, biodiversity, materials selection, and human health and well-being. The goal is to encourage landscape professionals and property owners to adopt practices that minimize environmental impact, enhance ecosystem services, and contribute to overall community resilience.

The SITES certification can be applied to a range of projects, including residential developments, public parks, commercial landscapes, and more. For residential landscapes, this initiative offers guidelines and benchmarks to ensure that outdoor spaces are not only aesthetically pleasing but also environmentally responsible and sustainable.

Sustainable practices need not be confined to high-end residences; they can be applied to any design, regardless of budget constraints. The essence of sustainability lies in thoughtful choices and mindful planning. As research and modern practices advance, low impact development will become more accessible and prioritized. The gardens of tomorrow will not only be visually stunning but resilient ecosystems that nurture biodiversity, conserve resources, and inspire generations to come. From native plant selections to stormwater management strategies, every decision shapes not only the aesthetics but also the ecological legacy of our homes.