Reimagining Industrial Heritage

A Cultural Hub for Ghent’s Old Dockyards

Master’s Thesis by Ufuk Sencanli

Reimagining Industrial Heritage

A Cultural Hub for Ghent’s Old Dockyards

Ufuk Sencanli

5142026

Masters Thesis Booklet

Thesis Supervisor: Fredrik Skåtar

Second Advisor : Esra Kagitci

Dessau Insititute of Architecture

Hochschule Anhalt Dessau

July 2025

“Except where otherwise noted, all photographs, diagrams, and visual materials are the author’s own work (2024–2025).”

This master’s thesis marks the culmination of a long academic journey and a deeply personal exploration of architecture, memory, and transformation. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who supported me along this path.

First and foremost, I extend my deepest thanks to my family and to my wife, Sena Şeyma. Your unwavering support, belief in me, and countless sacrifices have been the backbone of this process. Your patience and love gave me the strength to persevere, even in moments of doubt and fatigue.

I would also like to thank my thesis advisors, Fredrik Skåtar and Esra Kagitci, for their insightful guidance and critical feedback, which were instrumental in shaping both the intellectual and design trajectory of this work.

Lastly, I would like to acknowledge the city of Ghent—its dockyards, its silences, its forgotten infrastructures. This project is a tribute to the latent stories embedded in its concrete, steel, and voids.

This thesis explores how post-industrial heritage can be reinterpreted through architectural transformation, focusing on Ghent’s Old Dockyards. Grounded in the theoretical frameworks of palimpsest urbanism (Corboz, 1983), cultural sustainability, and urban vitality (Jacobs, 1961), the project reframes adaptive reuse as a layered dialogue between spatial memory and contemporary urban needs.

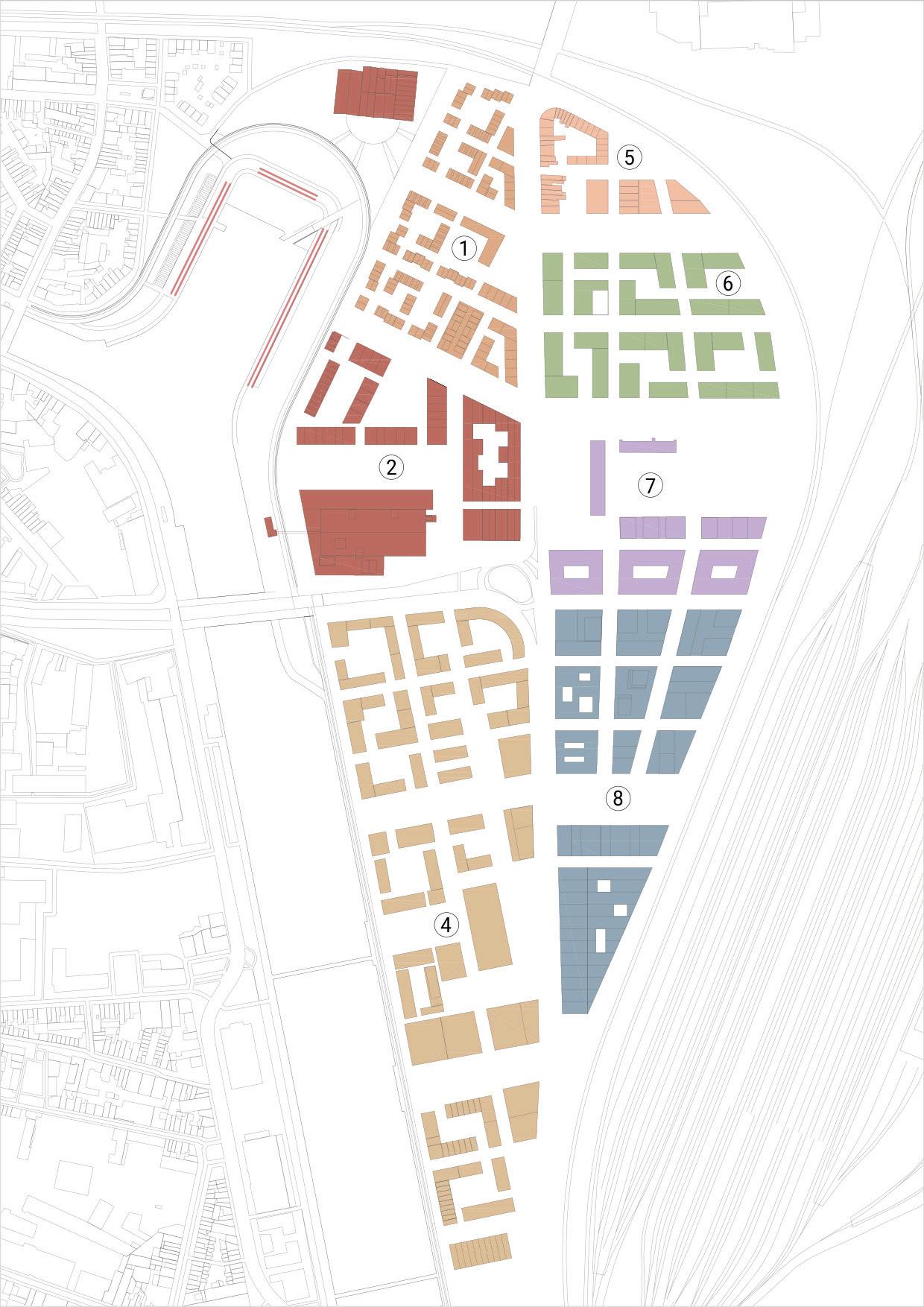

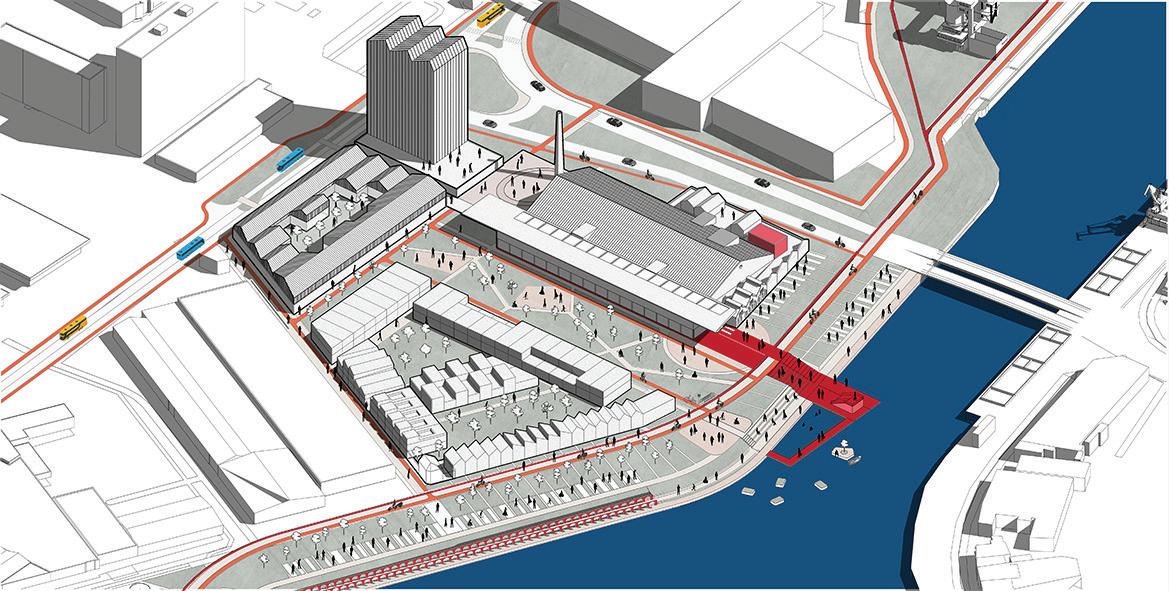

The research begins with a visionary masterplan that proposes eight interlinked zones blending housing, production, and culture into a hybrid urban fabric. Within this framework, the Cultural Spine— comprising repurposed industrial structures—emerges as the architectural focal point. At its core stands a 1920s concrete fertilizer factory, whose logistical logic of conveyors, storage bays, and forklift routes once dictated flows of material rather than human presence.

The central research question guiding the thesis is: How can the spatial logic of a logistical

industrial structure be transformed to foster cultural continuity and urban regeneration without erasing its material memory?

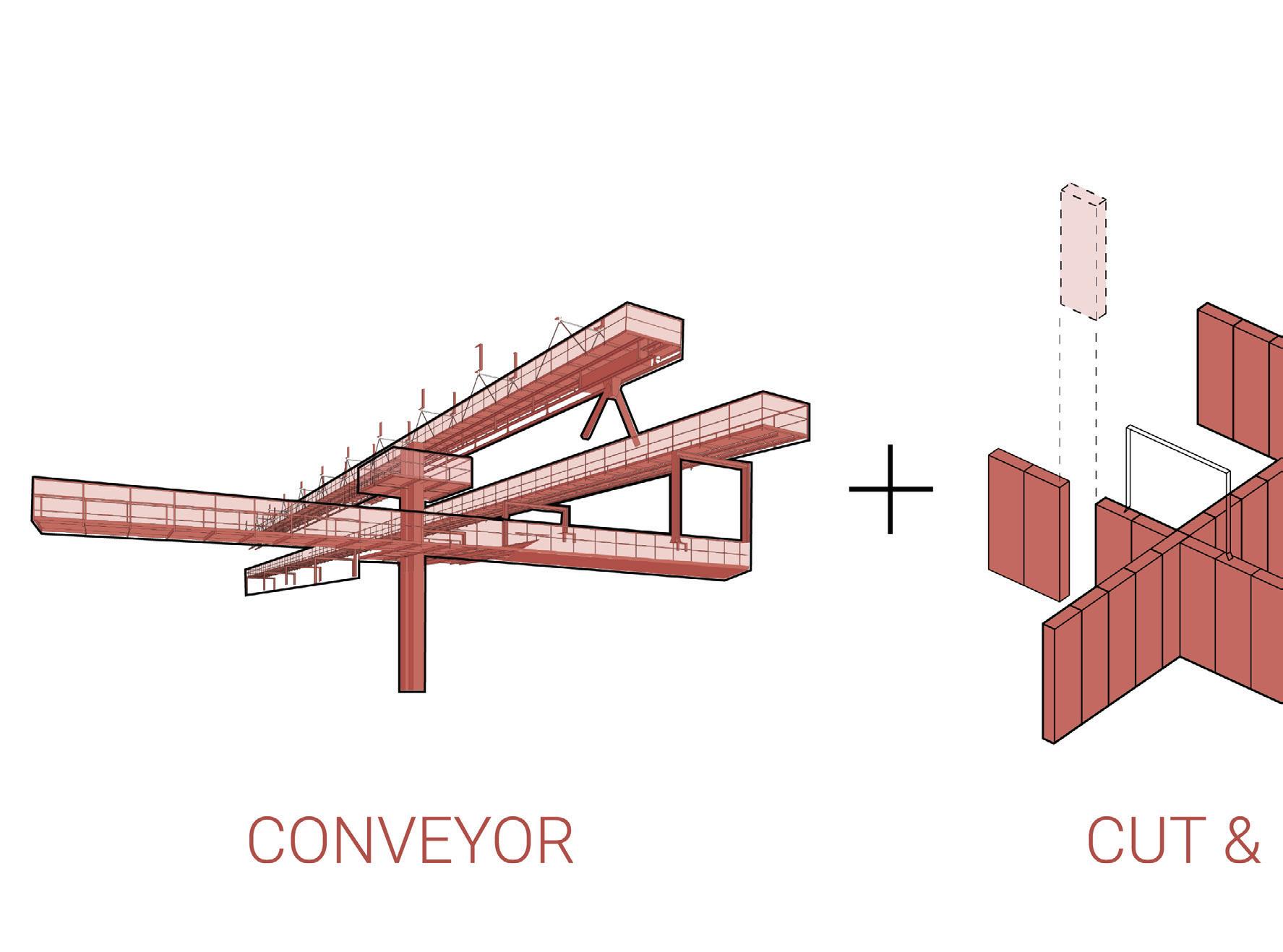

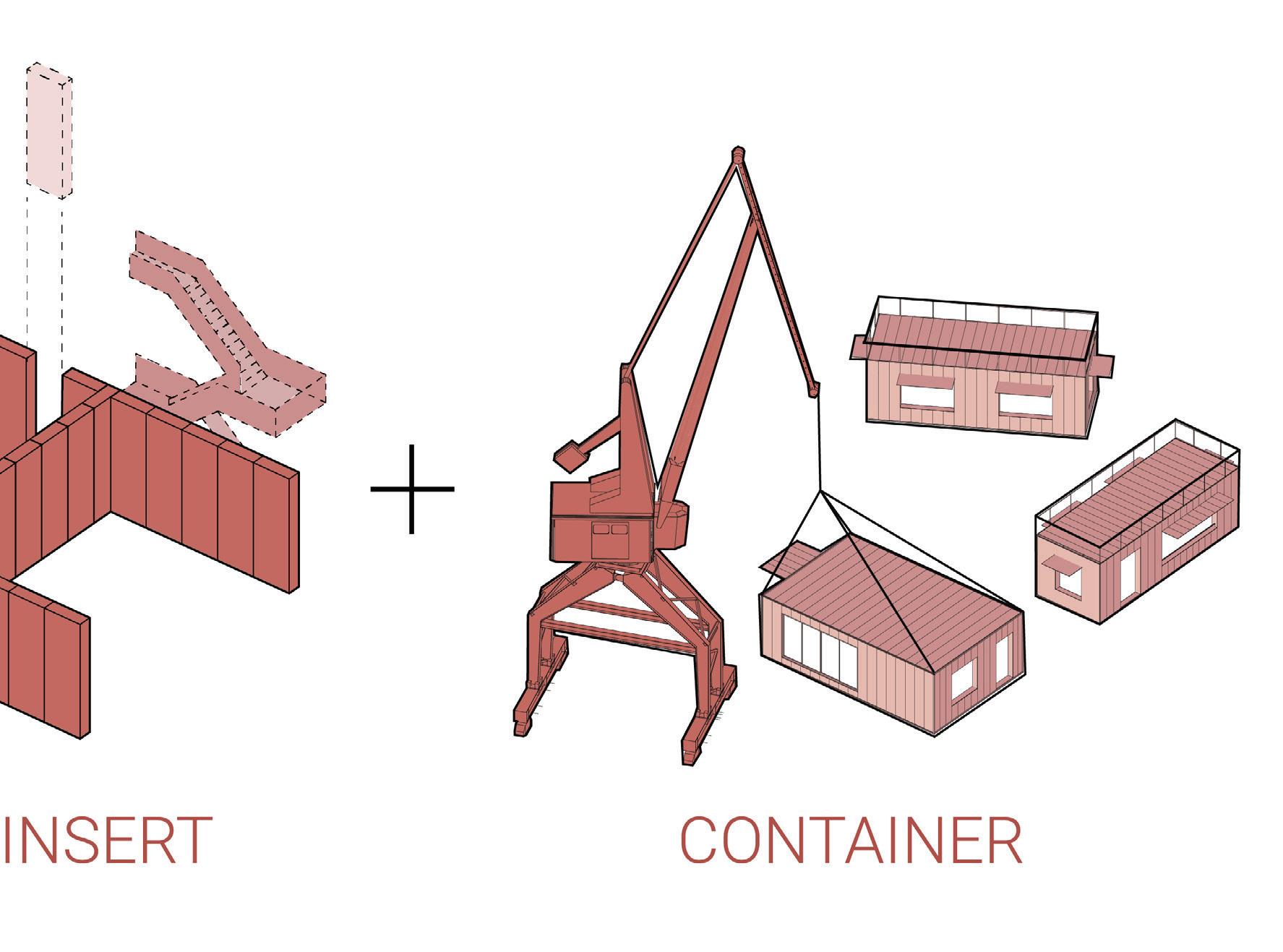

The design responds through three key strategies: reinterpreting the conveyor system as a circulation and narrative spine; employing a “Cut & Insert” methodology to surgically integrate new programs; and implementing containers as modular, adaptive cultural units.

Methodologically, the project combines design research, site observation, archival mapping, and iterative spatial experimentation. The outcome is both a masterplan and an architectural intervention that demonstrate how industrial infrastructure can be reconceived as a civic vessel—preserving spatial memory while enabling cultural transformation. Situated within a broader urban strategy, the thesis offers a site-specific, memory-driven model for adaptive reuse in post-industrial contexts.

Table of Contents

PART I — RESEARCH FOUNDATION

1. Introduction

1.1 Background & Context: From Industrial Logic to Cultural Flow

1.2 Research Question

1.3 Objectives & Relevance

1.4 Clarification of Key Concepts

2. Methodology

2.1 Ontological & Epistemological Approach

2.2 Cultural Sustainability as a Design Ethic

2.3 Hypothesis: Architecture as Cultural Rewiring

2.4 Research Position and Design Tools Justification

3. Research Methods

3.1 Archival and Literature Research

3.2 Site-Based Observation and Documentation

3.3 Visual and Diagrammatic Analysis

3.4 Iterative Design Experimentation

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1 Palimpsest Urbanism (André Corboz)

4.2 Cultural Sustainability in Post-Industrial Landscapes

4.3 Jane Jacobs & Urban Vitality

4.4 Adaptive Reuse Beyond Typology

4.5 Research Gaps: Towards a New Industrial Narrative

PART II — CASE STUDIES

5. Case Studies

5.1 Jernbanebyen Masterplan, COBE Architects

5.2 Europahafenkopf Bremen — COBE Architects

5.3 Zollverein Ruhr Museum, Essen — OMA + Böll Architects

5.4 Sichuan Arts Factory and Innovation Center, Urbanlogic

5.5 Wintercircus Ghent, Atelier Kempe Thill, Baro, SUMproject

5.6 LocHal Library, Braaksma & Roos, CIVIC, Inside O, Mecanoo

PART III — CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS

6. Site & Urban Analysis

6.1 Timeline of Spatial Transformation (1770–2019)

6.2 Urban Form and Spatial Fragmentation

6.3 Site-Specific Reading: Functional Layering & Memory Points

6.4 Community Needs and Socio-Spatial Gaps

6.5 Urban and Spatial Connectivity

PART IV — URBAN STRATEGY

7. Masterplan Development: From Policy to Design Intent

7.1 RUP Framework Reference

7.2 Memory Anchors & Spatial Cues

7.3 Strategic Zoning Logic

7.4 Layered Urban Systems

7.5 Final Masterplan Visualization

PART V — ARCHITECTURAL INTERVENTION

8. Architectural Proposal: The Factory as Memory Vessel

8.1 Design Evolution in Six Steps

8.2 Core Strategies: Conveyor, Cut & Insert, Container

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

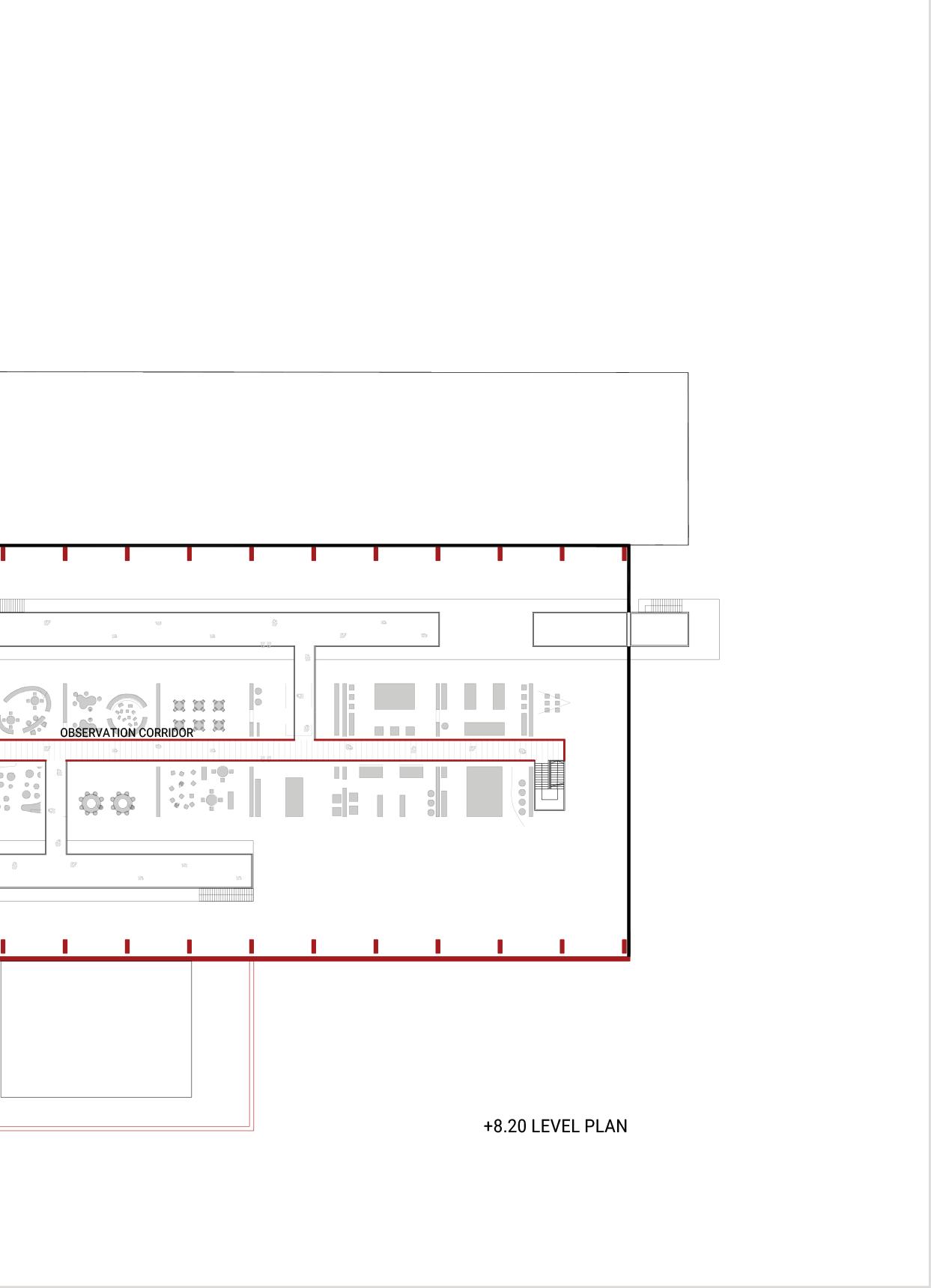

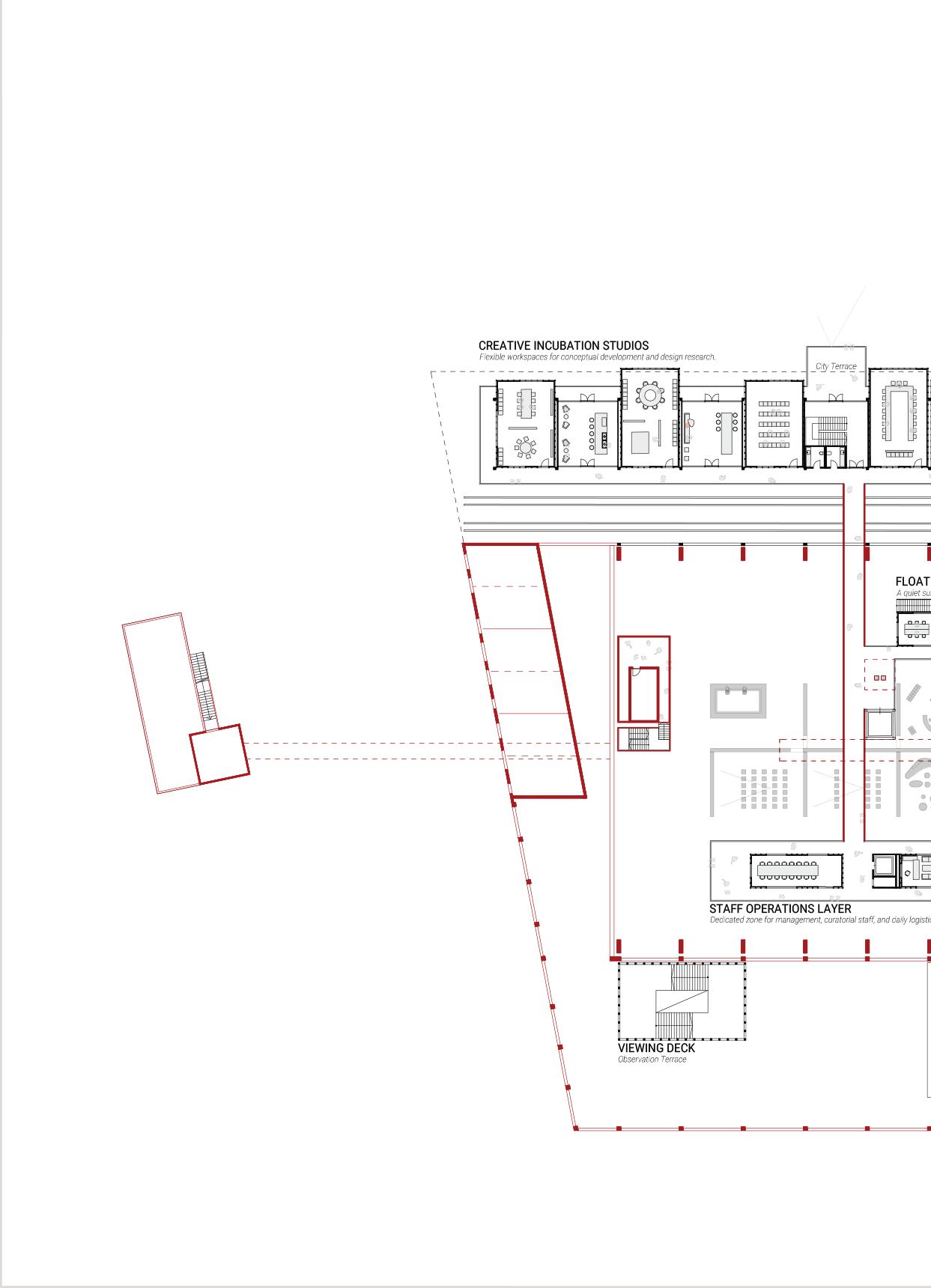

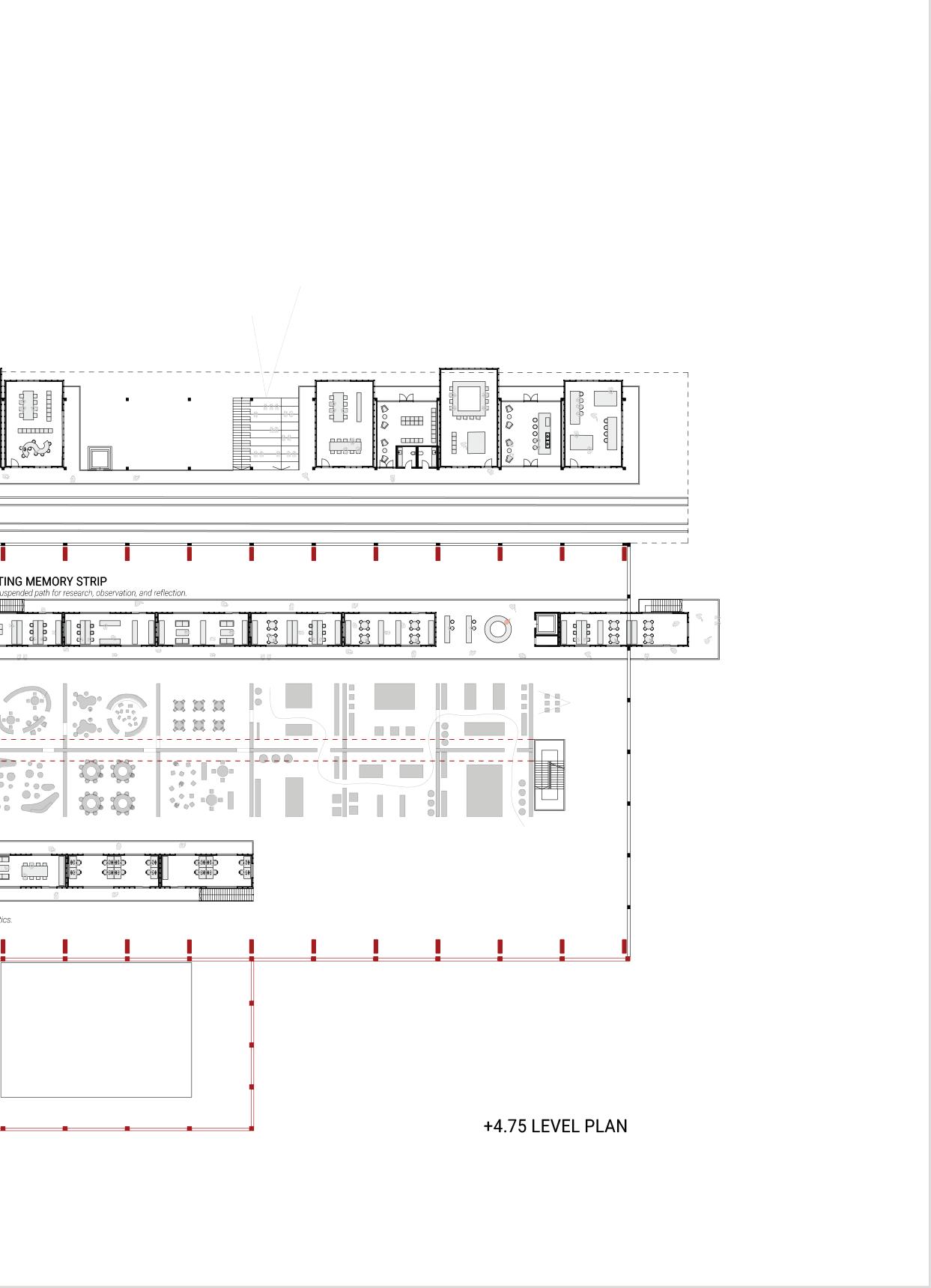

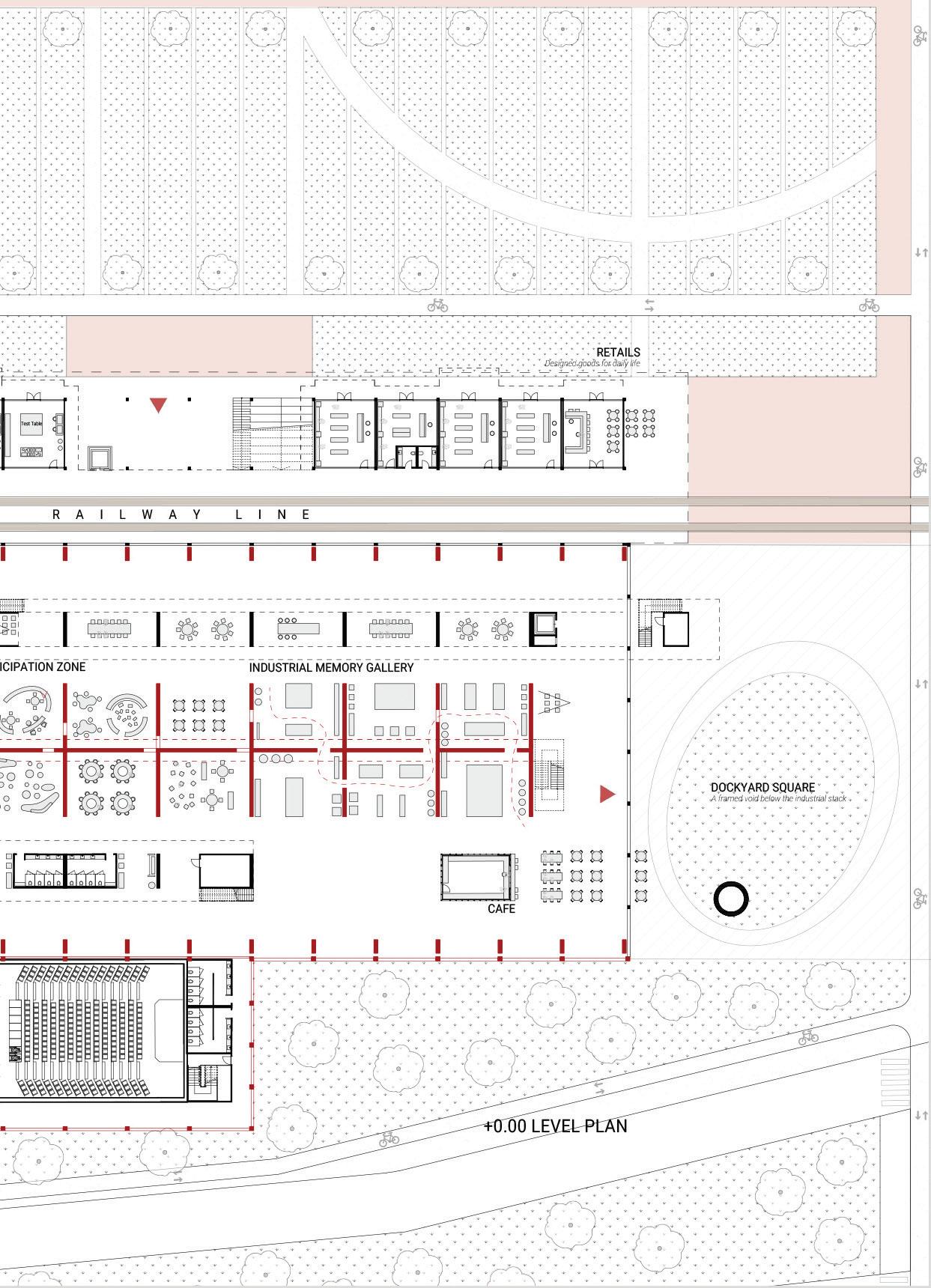

8.4 Architectural Floor Plans

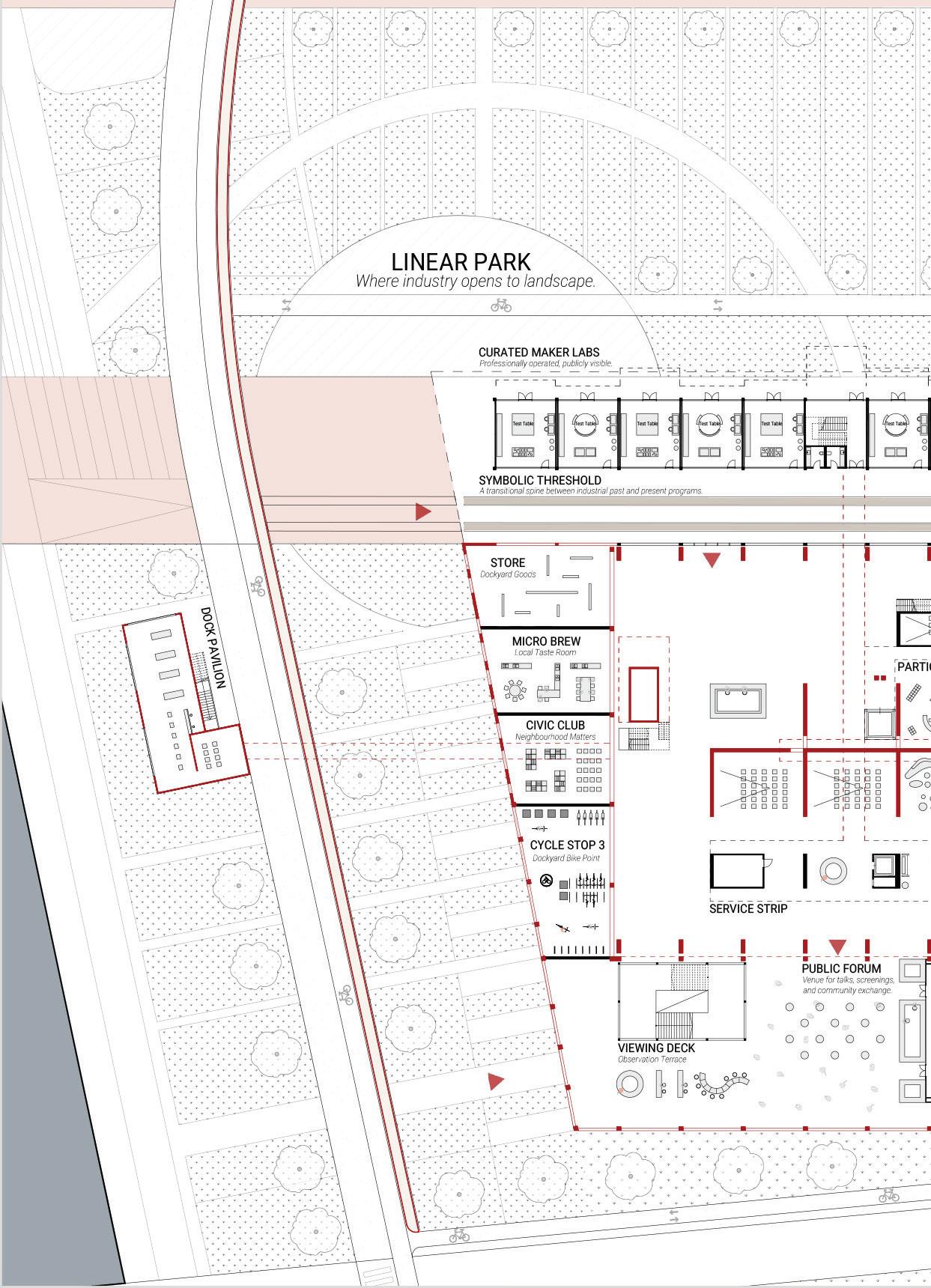

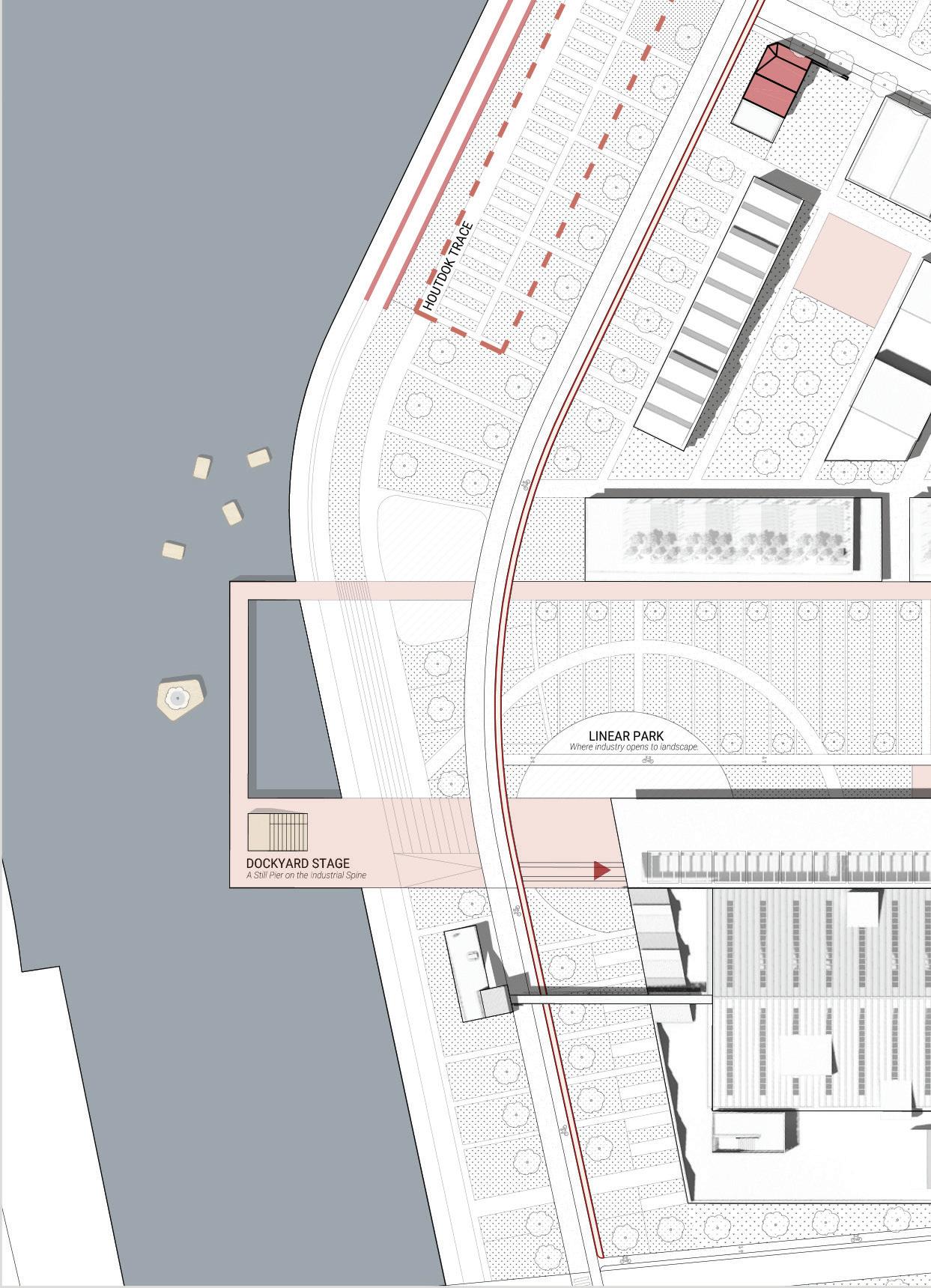

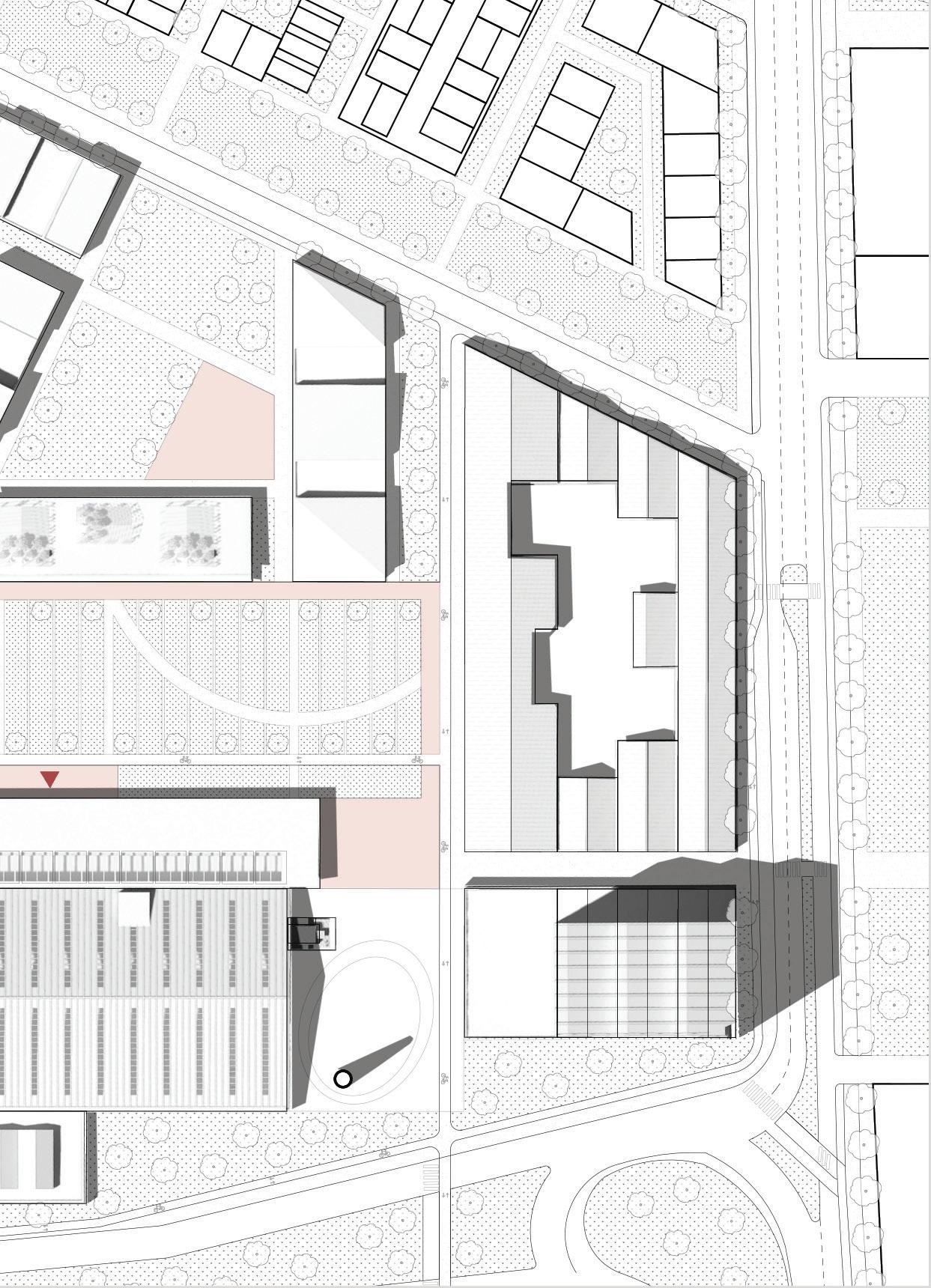

8.5 Site Plan

8.6 Visualizations

PART VI — FINAL REFLECTIONS

9. Conclusion

10. References

Photo by the author, 2024.

PART I — RESEARCH FOUNDATION

1. Introduction

1.1 Background & Context

1.2 Research Question

1.3 Objectives & Relevance

1.4 Clarification of Key Concepts

2. Methodology

2.1 Ontological & Epistemological Approach

2.2 Cultural Sustainability as a Design Ethic

2.3 Hypothesis: Architecture as Cultural Rewiring

2.4 Research Position and Design Tools Justification

3. Research Methods

3.1 Archival and Literature Research

3.2 Site-Based Observation and Documentation

3.3 Visual and Diagrammatic Analysis

3.4 Iterative Design Experimentation

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1 Palimpsest Urbanism (André Corboz)

4.2 Cultural Sustainability in Post-Industrial Landscapes

4.3 Jane Jacobs & Urban Vitality

4.4 Adaptive Reuse Beyond Typology

4.5 Research Gaps: Towards a New Industrial Narrative

1 Introduction

1.1 Background & Context:

From Industrial Logic to Cultural Flow

“Cities are living organisms—but what happens when their vital memories are erased?

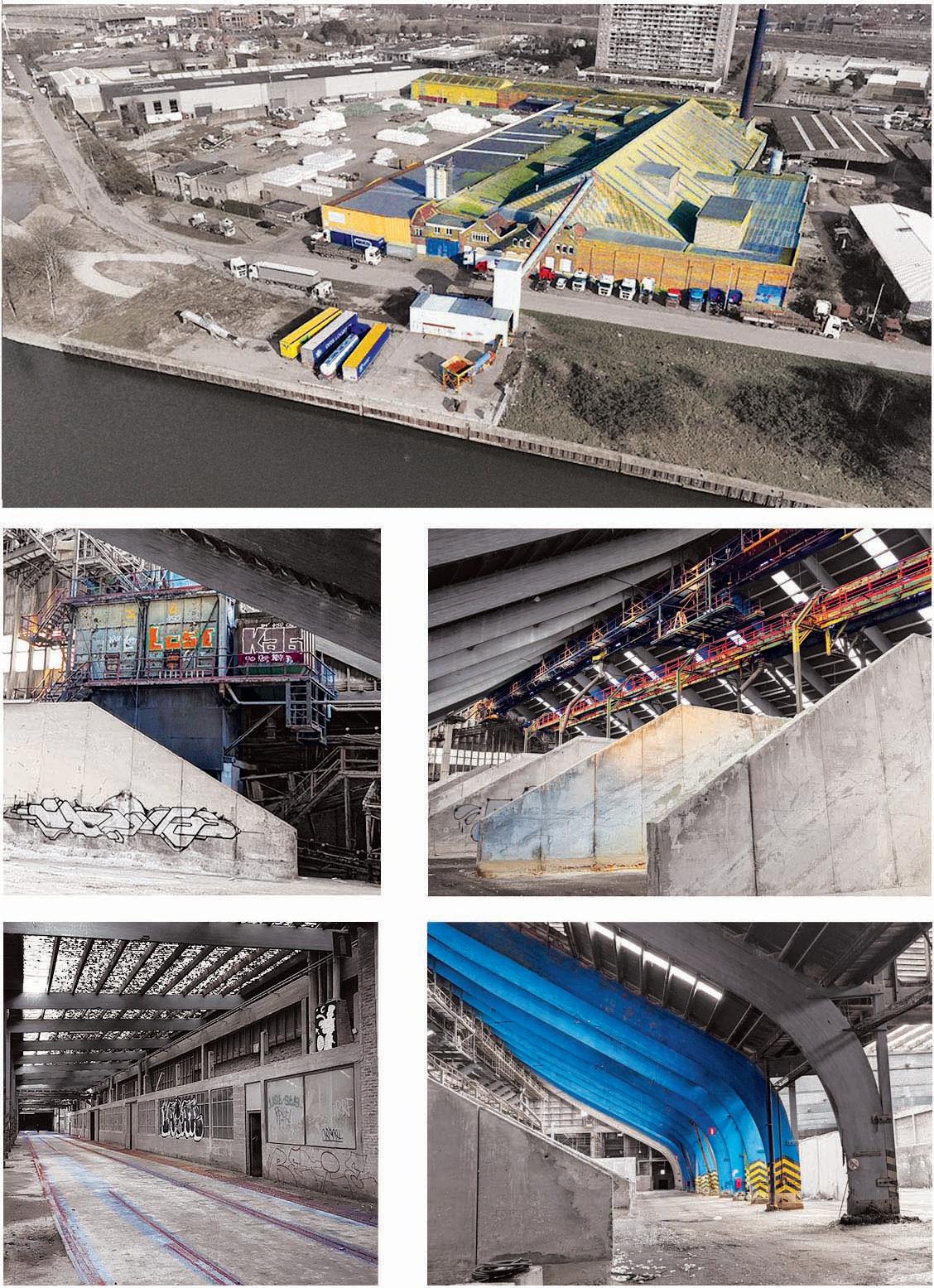

Ghent’s Old Dockyards, once integral to the city’s industrial metabolism, now linger as monumental yet mute structures—concrete silos, overhead conveyors, and logistical corridors that once animated the port’s economy.

These physical artifacts speak of a bygone era defined not by people but by goods, flows, and extraction. Yet despite their spatial prominence, they have become severed from contemporary urban life, standing as vacant shells within a city that no longer recognizes their purpose. Their functional obsolescence has turned them into voids of meaning, yet their material presence continues to define the landscape—a contradiction that demands a critical architectural response.

This thesis positions the dockyards not as static ruins but as latent vessels of possibility. From the perspective of André Corboz’s palimpsestic urbanism, the site offers a dense layering of time, infrastructure, and memory. Rather than viewing these industrial remnants as problems to be erased, the research reframes them as narrative systems waiting to be reactivated. As Ghent navigates ecological, cultural, and urban transitions, the question arises: How can the spatial logic of logistical infrastructure be transformed into spaces of cultural flow and social engagement?

The thesis embraces this friction—between permanence and change—as a design opportunity, aiming not to overwrite the past, but to work within its traces.

Pinte, M. (2014). Urban Development and Spatial Planning Department Archive

This project views the dockyards not as obsolete ruins but as latent frameworks for future urban vitality. The industrial infrastructures— steel bridges, conveyors, loading docks—are not obstacles but spatial tools with narrative capacity. These fragments reflect a functional logic rooted not in Fordist assembly, but in logistical circulation: a spatial system optimized for material movement, now open to cultural reinterpretation.

While many adaptive reuse projects treat architecture as an aesthetic object, this research frames the site as a performative system. The goal is not to preserve for nostalgia’s sake, but to transform with continuity. Spatial strategies such as re-inhabiting conveyor paths, reconfiguring voids, and inserting lightweight cultural programs are positioned as architectural responses to a broader urban and historical condition.

This contextual groundwork sets the stage for the thesis’ methodology: a combined reading of the city’s industrial DNA and the building’s logistical geometry. The research does not isolate the factory as an object but embeds it in its larger urban ecosystem—a living fragment of Ghent’s dockside metabolism.

Photo by Fredrik Skåtar, 2025.

1.2 Research Question

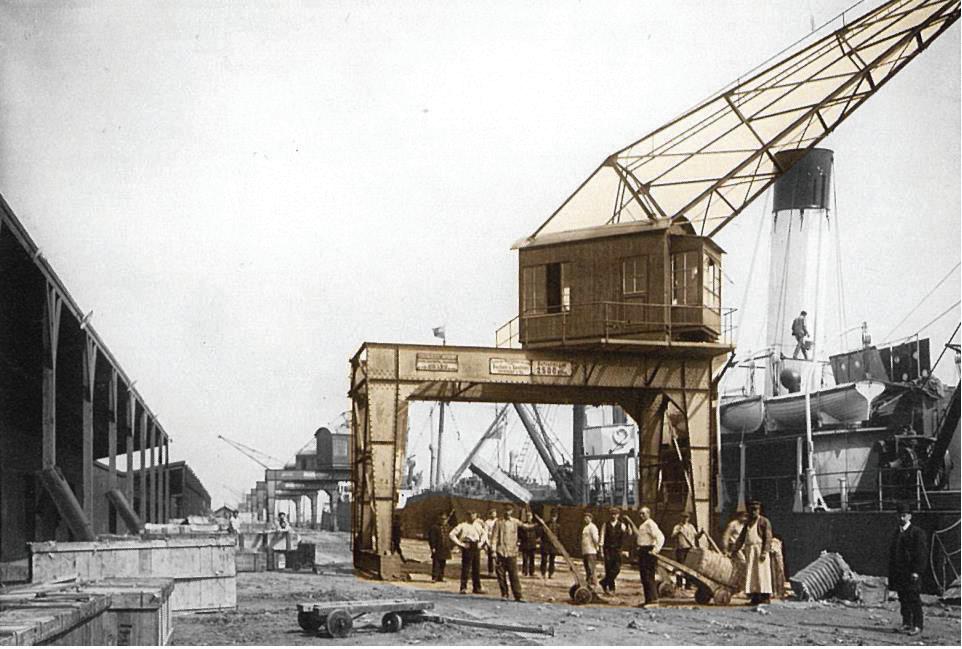

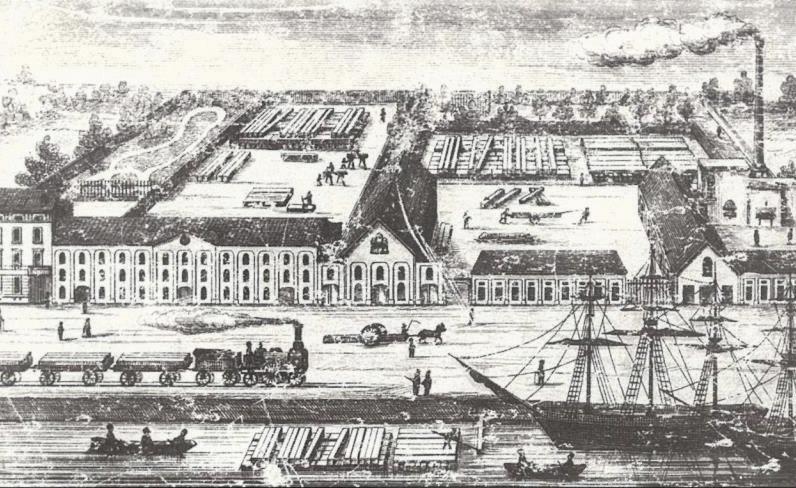

Pinte, M. (2014). Urban Development and Spatial Planning Department Archive. Handelsdok Harbor Photo (1840-1850)

How can the spatial logic of an early 20th-century former industrial structure in Ghent’s Old Dockyards be reimagined through adaptive reuse to foster cultural continuity, spatial memory, and public engagement?

This question guides the architectural and theoretical investigation throughout the thesis. It challenges conventional approaches to adaptive reuse by shifting focus from typological transformation to flow-based reinterpretation—rethinking the site’s conveyors, storage bays, and logistic systems not as obsolete relics, but as spatial narratives capable of hosting civic life. The inquiry sits at the intersection of postindustrial heritage, urban regeneration, and memorybased design, proposing a method to turn a dormant infrastructure into an active cultural framework.

1.3 Objectives & Relevance

The primary objective of this thesis is to develop an architectural strategy that reinterprets the spatial logic of a post-industrial logistical structure—specifically, a 1900s fertilizer factory in Ghent—into a platform for cultural production, public engagement, and spatial memory. Rather than treating the factory as a closed typology, the project explores its embedded flows— conveyors, storage bays, circulation paths—as design tools that can host new programs without erasing

the past. The relevance of this research lies in its methodological synthesis of theory and design. In a global context where post-industrial zones often face erasure or generic redevelopment, the thesis proposes an alternative: to build upon latent narratives and spatial residues, offering a framework for culturally attuned urban regeneration. It speaks to designers, planners, and theorists seeking to reconcile the permanence of memory with the necessity of change.

�� /activating industrial flows as spatial infrastructure

To reinterpret conveyors, storage bays, and forklift paths not as obsolete relics but as dynamic circulation and programmatic tools.

�� /building cultural continuity through spatial memory

To integrate historical spatial patterns and material presence into a new architectural logic that enables civic use without erasure.

�� /embedding reuse within multi-scalar planning

To link building-scale transformation with a six-zone urban masterplan that transitions from waterfront to rail-edge, enhancing social and spatial cohesion.

�� /transforming monolithic structures through surgical insertion

To apply the “Cut & Insert” strategy as a precise and respectful intervention method, layering new functions within heavy industrial shells.

�� /designing for long-term adaptability and cultural use

To generate modular, inclusive, and communityresponsive spaces that foster engagement, learning, and production.

This thesis draws on several key concepts that guide its theoretical and spatial approach. Below are brief clarifications of how these terms are understood and applied throughout the work:

�� /palimpsest urbanism

Coined by André Corboz (1983), the term describes the city as a layered artifact—where new interventions do not erase the past, but are inscribed over it. In this thesis, the concept frames the dockyard not as a clean slate but as a stratified site where historical and contemporary uses coexist. Architecture becomes an act of selective inscription, not replacement.

�� /adaptive reuse beyond typology

This approach moves beyond merely reprogramming a building’s use. It focuses on spatial logic—here, the logic of logistics: conveyors, circulation paths, and storage bays. The thesis argues that these flows can be reinterpreted to host cultural, civic, and collective life.

1.4 Clarification of Key Concepts

�� /cultural sustainability

Not limited to ecological or material strategies, cultural sustainability is framed here as the continuity of memory, use, and place-based identity. This project addresses how reuse can anchor cultural meaning without resorting to pastiche or nostalgia.

�� /cut & insert

A spatial strategy of surgical intervention: precise incisions into heavy industrial volumes that insert light, contemporary programs while preserving the host structure’s character. These insertions are minimal but impactful—threading new narratives into existing geometries.

�� /conveyor as narrative spine

Originally a functional component for moving goods, the conveyor is reimagined as a circulation system for visitors. It becomes an architectural storytelling device that carries people, memory, and experience through the space.

2. Methodology

This thesis adopts a design-led research methodology that bridges architectural inquiry with cultural theory, site analysis, and iterative spatial experimentation. It views the Old Dockyards of Ghent not merely as a subject of investigation, but as a palimpsestic ground to be reinterpreted and transformed.

Rooted in a constructivist epistemology, the project positions architecture as both a medium of analysis and a tool for narrative speculation. Knowledge is generated through drawing, modeling, site immersion, and conceptual synthesis, rather than solely through textual observation. Architecture here is not just the outcome—it is the process of inquiry itself.

2.1 Ontological & Epistemological Approach

The research assumes that industrial structures are temporal containers, shaped by shifting logics of production, infrastructure, and social use. They are read as active palimpsests—layers of material memory, functional residue, and spatial intelligence. This aligns with a constructivist approach, emphasizing situated knowledge and iterative testing through design.

2.2 Cultural Sustainability as a Design Ethic

Beyond ecological metrics, sustainability is reframed here as a cultural practice: How can architectural reuse sustain memory, meaning, and urban continuity? Drawing from Corboz’s concept of the city as a palimpsest and Jacobs’s urban vitality, the thesis pursues place-based transformation that retains inherited logics while enabling new civic life.

2.3 Hypothesis: Architecture as Cultural Rewiring

The central hypothesis holds that logistical infrastructures — such as conveyors, containers, and storage bays — can be reprogrammed as vessels for cultural engagement. Rather than imposing new forms, the design strategy uses Cut & Insert tactics to embed memory within transformation:

- Conveyors guide visitors

- Voids become event spaces

- Containers house modular cultural uses

2.4 Research Position and Tools

The The project integrates both qualitative and spatial methods:

-Theoretical Analysis: Cultural sustainability, reuse theory, palimpsest, urban resilience

-Site-Based Documentation: Photographs, mappings, diagrams, temporal comparisons

-Case Studies: Comparative analysis of adaptive reuse precedents

-Design Iteration: Testing hypotheses through plans, models, sectional narratives

Each tool is treated not as a passive support but as an active driver of discovery, enabling design to emerge as both a method and a form of cultural critique.

This thesis employs a combination of qualitative, site-based, and design-driven research methods to investigate how post-industrial spatial logics— particularly logistical infrastructure—can be transformed into cultural programs. Rooted in a constructivist research stance, the project draws knowledge from spatial observation, archival

3. Research Methods

documentation, visual experimentation, and theoretical analysis.

The methods are selected to reflect the project’s multiscalar approach, connecting urban masterplanning with detailed architectural interventions. Each method plays a distinct role in exploring the historical, physical, and narrative potential of Ghent’s Old Dockyards.

1.Archival and Literature Research

- Study of historical maps, documents, and photographs to understand the site’s industrial evolution.

- Analysis of relevant texts on adaptive reuse, cultural sustainability, and urban palimpsests (e.g. Corboz, Jacobs, and contemporary reuse discourse).

- Purpose: to frame a theoretical foundation and identify precedents and gaps.

3. Visual and Diagrammatic Analysis

- Use of axonometric drawings, exploded diagrams, and sectional studies to reinterpret the site’s original logic.

- Flow diagrams mapping past industrial movement vs. projected cultural flows.

- Purpose: to test how design strategies like cut & insert, container reuse, and cultural spine emerge from existing infrastructure.

2. Site-Based Observation and Documentation

- Field visits for spatial reading, photo documentation, and in-situ sketching.

- On-site mapping of logistical structures (conveyors, bays, forklift paths), current accessibility issues, and voids of use.

- Purpose: to understand how material memory is embedded in the existing spatial fabric.

4. Iterative Design Experimentation

- Sketching, physical and digital model-making, and spatial sequencing to test conceptual ideas.

- Spatial layering in section, manipulation of volumes, circulation loops, and transitions from void to program.

- Purpose: to materialize the hypothesis and ground theoretical ideas in tangible architectural proposals.

4. Theoretical Framework

This thesis draws upon five interrelated theoretical lenses — Palimpsest Urbanism, Cultural Sustainability, Adaptive Reuse, Urban Vitality, and the pursuit of a New Industrial Narrative — to construct a conceptual foundation for design interventions in Ghent’s Old Dockyards.

Each framework contributes a specific perspective on how industrial legacies can be reinterpreted within contemporary urban and cultural contexts. Together, they offer a multi-scalar reading of the site: from material memory and structural reuse to spatial equity and community engagement.

The accompanying diagram visualizes the interplay

between these frameworks through a shared vocabulary of key concepts. These range from tactical design tools (e.g., Cut & Insert, Hybrid Assemblies) to socio-spatial aspirations (Community Anchors, Spatial Resilience). The lines connecting each concept across domains emphasize their overlap and reinforce the thesis’s interdisciplinary foundation.

Rather than adopting a single lens, the framework operates as a conceptual web — reflecting the layered nature of the site and the complexity of its future transformation. In this way, design becomes not only a spatial act but a theoretical negotiation between past, present, and speculative futures.

André Corboz’s concept of palimpsest urbanism reconfigures the city not as a finished object, but as a continuously rewritten text—a layered accumulation of meanings, traces, and interventions over time. In this view, urban form is never complete; it is constantly inscribed upon, edited, and interpreted anew by successive generations of architects, planners, and users (Corboz, 1983). This theoretical lens challenges notions of erasure and tabula rasa, favoring continuity, heterogeneity, and temporal complexity. In the context of Ghent’s Old Dockyards, the palimpsest paradigm

4.1 Palimpsest Urbanism

(André Corboz)

offers a compelling model for engaging with industrial ruins. Rather than treating the 1920s fertilizer factory as a nostalgic monument or a blank slate, the thesis adopts a palimpsestic approach: acknowledging existing structural memory (e.g., conveyor belts, storage bays, steel bridges) while inserting new spatial narratives. The Cut & Insert strategy, for example, does not overwrite the past—it surgically opens new voids within it. Similarly, the Chronology Spine reads the building not only through space, but also through time.

“The photographs from 1893 and 2024 illustrate the drastic transformation of the site, aligning with the research objective of understanding the erosion of industrial identity and the potential for its preservation within new developments.”

Image 4.1.1 Triferto Factory and Surroundings in 1893

Image 4.1.2 Triferto Factory and Surroundings in 2024

4.2 Cultural Sustainability in Post-Industrial Landscapes

Cultural sustainability extends beyond ecological or economic concerns to encompass the preservation and evolution of local meanings, practices, and spatial identities. In post-industrial contexts—where former production sites often sit abandoned—this concept becomes particularly critical. These landscapes are not only marked by physical decay but also by a loss of the social and cultural fabric once embedded in their operations.

Rather than treating these sites as relics or blank slates, cultural sustainability calls for their reinterpretation as carriers of memory. Scholars such as Duxbury, Soini, and Hosagrahar emphasize the need to sustain cultural values by enabling continuity and transformation within

existing urban and architectural frameworks. This means engaging with the material traces of the past — not simply conserving them, but allowing them to take on new roles that reflect evolving communal identities.

In this view, cultural sustainability becomes a design ethic that balances preservation with reinterpretation. It resists erasure while avoiding nostalgia, enabling spaces to retain their temporal complexity. Especially in post-industrial cities like Ghent, it offers a critical tool for reactivating memory-laden sites without severing them from contemporary urban life. Adaptive reuse, when approached through this lens, is not only about architectural function, but about safeguarding the intangible values embedded in spatial forms.

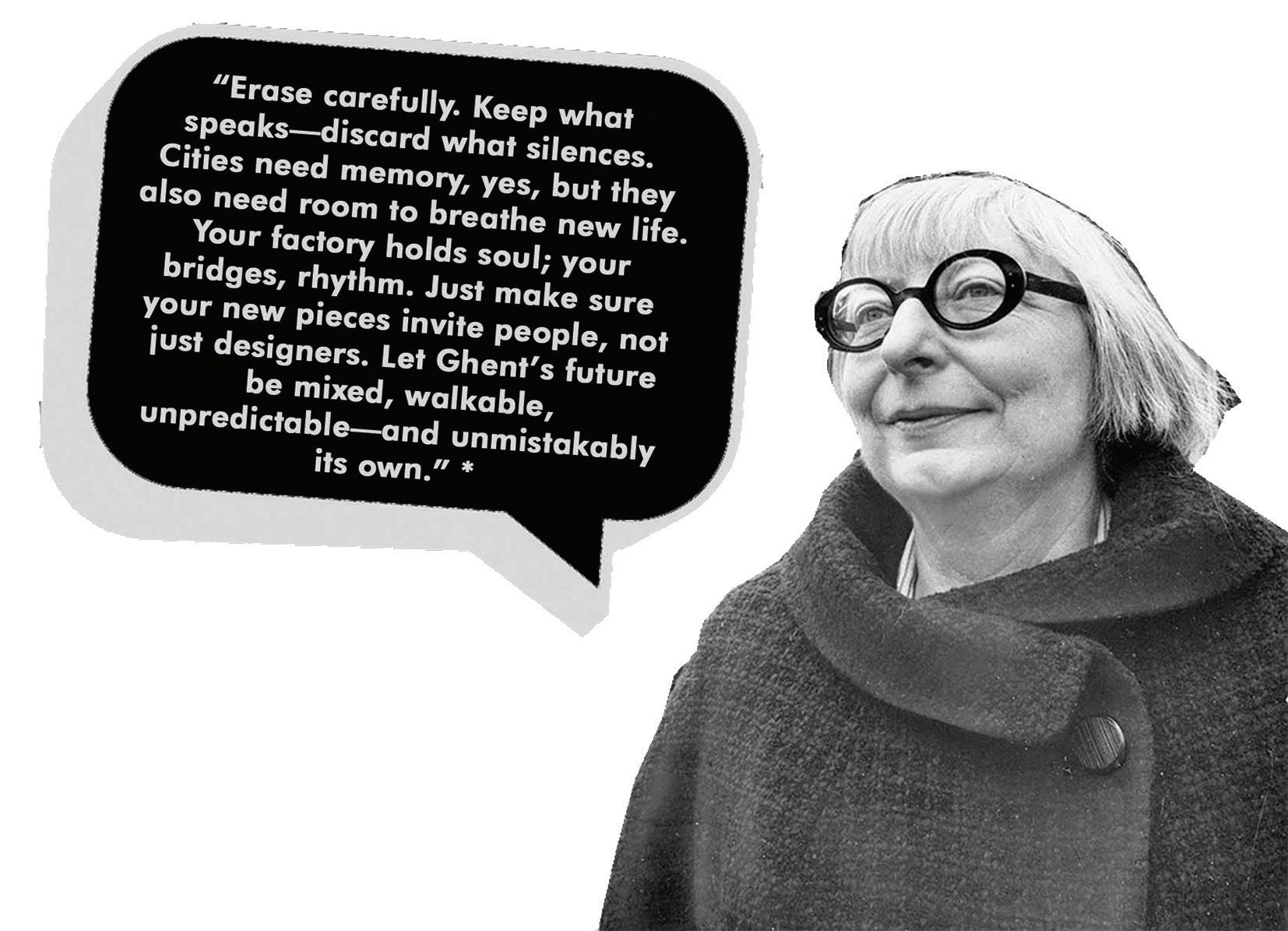

Jane Jacobs’s seminal work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), introduced a radically humancentric view of urban life, critiquing the modernist tendency toward spatial segregation and sterile, topdown planning. Her emphasis on “eyes on the street,” mixed uses, short blocks, and aged buildings remains foundational to contemporary thinking on urban vitality.

In post-industrial regeneration, Jacobs’s ideas offer not just theoretical guidance but spatial principles. She argued that older buildings—often undervalued by planning authorities—are essential to a city’s diversity, as they support experimental uses, smallscale enterprises, and cultural initiatives that new developments often fail to accommodate. This insight

4. Theoretical Framework

4.3 Jane Jacobs & Urban Vitality

directly informs adaptive reuse strategies in postindustrial contexts, where aging infrastructures provide both material texture and socio-cultural potential.

Urban vitality, in Jacobs’s terms, is sustained by complexity—of function, time, and human interaction. For the old dockyards of Ghent, such complexity is not erased by obsolescence; it lies dormant, embedded in the factory walls, circulation patterns, and industrial logic. The challenge, then, is not to overwrite this with a new order but to reveal and extend it. This thesis interprets Jacobs’s framework not as a nostalgic return to pre-industrial urbanism, but as an invitation to generate layered, participatory, and dynamic urban spaces through reuse.

* Interpretive Illustration — Jane Jacobs and the Future of Ghent’s Dockyards This speculative quote is constructed as a homage to Jane Jacobs’s urban philosophy, translated into the context of Ghent’s post-industrial transformation. It does not cite the author verbatim but channels her principles to critically reflect on adaptive reuse, social complexity, and the challenges of shaping meaningful urban futures.

4.4 Adaptive Reuse Beyond Typology

Conventional approaches to adaptive reuse often focus on typological transformation—converting a church into a library, or a factory into housing—based on functional equivalence or symbolic continuity. While these methods offer architectural value, they can sometimes overlook the deeper spatial intelligence and operational histories embedded within industrial structures.

This thesis advocates for a shift beyond typology. It proposes that adaptive reuse should begin with a careful reading of spatial logic: circulation patterns, material hierarchies, and latent voids that once structured a building’s original function. Rather than

prioritizing form or program alone, this approach emphasizes the importance of site-specific spatial narratives.

By treating industrial heritage not as a fixed typology but as a layered and interpretable system, adaptive reuse becomes a tool for cultural re-articulation. Such an approach enables architects to work with what is already present—physically and historically—without replicating or erasing it. In doing so, reuse becomes not a substitution, but a dialogue across time, connecting past use with contemporary meaning.

4.5 Research Gaps: Towards a New Industrial Narrative

Towards a New Industrial Narrative

While adaptive reuse has gained increasing prominence in architectural discourse, much of the existing literature gravitates towards either aesthetic preservation or functional repurposing. In post-industrial contexts especially, adaptive strategies often fall into two dominant models: either the romanticization of decay or the clean slate of redevelopment. Both extremes tend to obscure the nuanced spatial intelligence and logistical operations that defined these sites.

Moreover, industrial buildings are frequently treated as inert containers for new functions, rather than as active agents of spatial storytelling. Their embedded circulatory systems, modular structures, and operational rhythms

are rarely interrogated as design generators. This results in reuse models that may be visually compelling but lack continuity with the building’s original logic.

This thesis addresses this gap by proposing a spatially interpretive model of reuse—one that engages with the operational DNA of a site. Instead of approaching the industrial factory as a blank canvas, it treats it as a narrative framework, capable of hosting new cultural meanings through strategic architectural intervention. In doing so, the research moves toward a new industrial narrative: one that is memorybased, spatially intelligent, and forward-looking.

Image by COBE, Europahafenkopf Bremen

PART II — CASE STUDIES

5. Case Studies

5.1 Jernbanebyen Masterplan, COBE Architects

5.2 Europahafenkopf Bremen — COBE Architects

5.3 Zollverein Ruhr Museum, Essen — OMA + Böll Architects

5.4 Sichuan Arts Factory and Innovation Center, Urbanlogic

5.5 Wintercircus Ghent, Atelier Kempe Thill, Baro, SUMproject

5.6 LocHal Library, Braaksma & Roos, CIVIC, Inside O, Mecanoo

5. Case Studies

5.1. Jernbanebyen Masterplan, Copenhagen

COBE Architects

Theme: Masterplan & Urban Zoning Strategy in Post-Industrial Context

Jernbanebyen is a transformative urban redevelopment project located on a disused railway yard in Copenhagen. COBE Architects approached this masterplan with a deep respect for the site’s industrial history while embedding a futureoriented vision. The strategy involves structuring the urban fabric into a series of zones that promote permeability, walkability, and the integration of diverse programs such as housing, creative industries,

and green infrastructure. A key aspect of the project is the retention and reinterpretation of industrial buildings, which are adapted to accommodate new uses while preserving their material and spatial legibility. The project offers a compelling model for Ghent’s dockyards, demonstrating how zoning and strategic density can reknit formerly disconnected industrial terrains into vibrant urban continuities.

Image by COBE, 2021

5.2. Europahafenkopf Bremen

COBE Architects

Theme: Waterfront Redevelopment & Industrial Interface

This waterfront redevelopment in Bremen exemplifies how urban identity can be regenerated through zoning strategies anchored in material continuity. COBE Architects organize the site through a rhythmic block structure that recalls the historical scale of the harbor’s warehouses, employing redbrick materiality and modular urban forms. The project blends residential, commercial, and public

amenities, creating a resilient framework that supports social interaction and economic revitalization. As a precedent, Europahafenkopf informs this thesis’s masterplan approach, illustrating how site-specific zoning—balanced with heritage aesthetics—can scaffold contemporary urban life without erasing the infrastructural DNA of industrial port sites.

Image by COBE, 2021

5.3. Zollverein Ruhr Museum, Essen

OMA + Heinrich Böll + Hans Krabe

Theme: Cultural Reuse of Logistical Infrastructure

At Zollverein, OMA and Böll Architects transformed a former coal-washing plant into a museum by embedding the architectural intervention within the building’s existing logistical spine. The original conveyors, hoppers, and vertical circulation systems are preserved and reinterpreted as spatial devices that guide visitors through the museum. This design strategy emphasizes industrial authenticity while

creating a spatial narrative that foregrounds movement and memory. Zollverein demonstrates how the reinterpretation of logistical elements—as conveyors of meaning rather than just material—can become a core architectural concept. The project resonates directly with this thesis’s design approach to Ghent’s fertilizer factory, where conveyors are repurposed to facilitate cultural flow.

Image by Gili Merin, 2014.

5.4. Sichuan Arts Factory and Innovation Center – China

Urbanlogic Architecture

Theme: Cut & Void Interventions in Industrial Ruins

Urbanlogic’s adaptive reuse of a defunct cement factory in Chengdu is structured around a process of selective demolition, incision, and insertion. Large volumes are cut from the monolithic structure to create courtyards and vertical connections, while new programmatic elements are inserted using lightweight construction. The result is a layered and fragmented

spatial experience that reveals both the memory of the old and the vitality of the new. This approach—spatially surgical and materially expressive—parallels the “Cut & Insert” methodology employed in this thesis. The project affirms the potential of minimal interventions that strategically carve space to foster new civic uses within industrial shells.

Image by Urbanlogic, 2016.

5.5. Wintercircus Ghent – Renovation Project

Atelier Kempe Thill, Baro Architectuur bv, SUMproject

Theme: Layered Reuse within Urban Heritage

The Wintercircus project in Ghent centers on the reuse of a historic industrial structure that had long stood vacant and partially decayed. Rather than overrestoring or fully redeveloping the site, the architectural team embraces the building’s layered materiality— stabilizing deteriorated elements, preserving traces of prior use, and overlaying new functions. The

intervention includes performance spaces, circulation cores, and transparent insertions that coexist with the original brickwork and concrete skeleton. This sensitive treatment of decay and continuity aligns with the palimpsestual ethos of the thesis, underscoring the narrative richness of industrial remnants when treated as living heritage.

Image by VisitGhent, 2024.

5.6. LocHal Library – Tilburg, Netherlands

Braaksma & Roos architectenbureau, CIVIC architects, Inside Outside, Mecanoo Theme: Industrial Memory as Social Catalyst

In Tilburg, the adaptive reuse of a former locomotive hall into the LocHal Library exemplifies how industrial infrastructure can be transformed into inclusive cultural space. The project retains the original steel frame, gantry cranes, and soaring open volumes, juxtaposing them with movable curtains, flexible furniture, and human-scaled programs such as reading zones and

exhibition platforms. The architecture encourages interaction while amplifying the building’s monumental quality. As a precedent, LocHal supports the thesis’s exploration of memory as a spatial catalyst—affirming that industrial legacy can be reimagined not only as history, but as active social infrastructure for civic life today.

Image by Stijn Bollaert, 2019.

PART III — CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS

6. Site & Urban Analysis

6.1 Timeline of Spatial Transformation (1770–2019)

6.2 Urban Form and Spatial Fragmentation

6.3 Site-Specific Reading: Functional Layering & Memory Points

6.3.1. Memory Anchors: Spatial Figures of Collective Significance

6.3.2. Industrial Shells as Functional Archives: The Case of Triferto

6.4 Community Needs and Socio-Spatial Gaps

6.5 Urban and Spatial Connectivity

6. Site & Urban Analysis

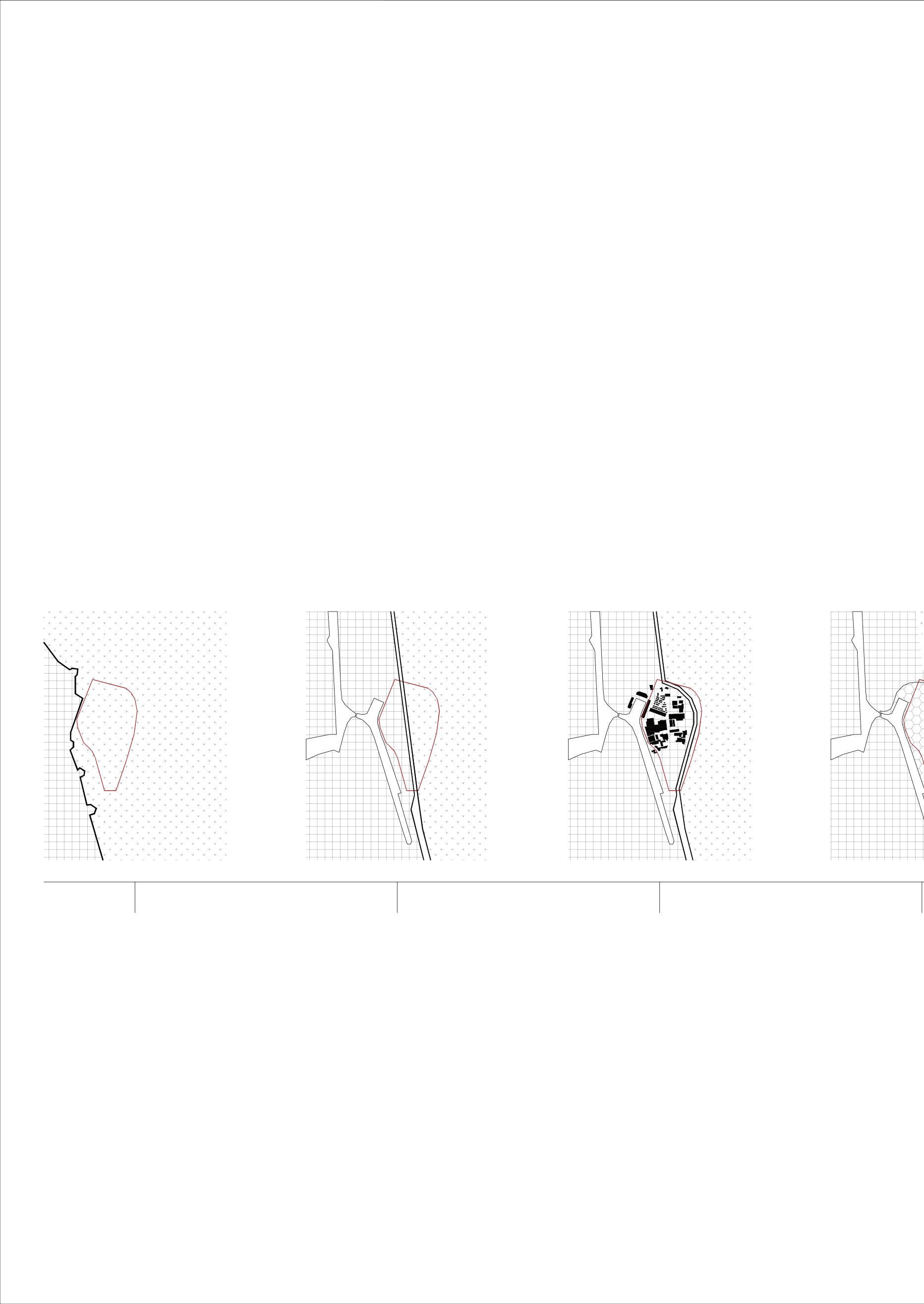

6.1 Timeline of Spatial Transformation – Ghent Dockyards (1770–2019)

This timeline diagram illustrates the spatial evolution of Ghent’s Old Dockyards from rural periphery to post-industrial void. From the early meadows of 1770 to the infrastructural boom of the late 19th century, each stage reveals a shift in spatial logic—from logistical expansion to fragmented urbanism. Key municipal interventions, such as OMA’s 2006 plan and TAB’s 2019 proposal, introduced new visions for

residential integration and mixed-use development. However, cultural programming remained absent. The final stage, represented by this thesis, proposes a cultural zoning strategy that reinterprets industrial spatial logic through adaptive reuse. By inserting civic functions within logistical structures, the project bridges historical flows with future urban vitality.

1770

The area was predominantly meadows and located on the city’s outskirts, with no urban development.

1893

The port’s development began alongside the construction of railway infrastructure, establishing industrial connectivity.

1950-1960

The railway was moved eastward, and residential construction commenced with highrise apartments and temporary wartime housing transitioning into permanent developments.

1977-1991

Regional plans assigned eastern area housing western area industrial purposes, adding provisions small-scale use in residential

1977-1991 and local assigned the area for and the area for purposes, provisions for

small-scale business residential zones.

2006

OMA’s master plan emphasized residential growth, parks, and dense urban zones, though Afrikalaan was excluded.

2019 - 2025

Municipal agencies like SoGent, BUUR, and TAB Architects proposed frameworks prioritizing livable density, mixed-use zoning, and integration of production with housing, setting the stage for cultural reactivation.

2025 (Present)

A student thesis introduced a cultural zoning strategy focused on adaptive reuse, reinterpreting industrial logic to transform logistical voids into vibrant civic infrastructure.

6.2 Urban Form and Spatial Fragmentation

1912 - Structured for Industrial Efficiency

The 1912 site plan reveals a coherent industrial landscape organized around production and distribution. Despite its functional clarity, it lacks integration with the urban fabric or public life.

The spatial fabric of Ghent’s Old Dockyards has undergone a significant transformation since the early 20th century. A comparative analysis of the site plans from 1912 and 2024 reveals a shift from a cohesive industrial morphology to a fragmented urban condition marked by physical disjunctions and underutilized land.

In 1912, the dockyards were integrated within a unified industrial system, anchored by the logistical rhythms of waterborne trade and connected to the city’s railway and maritime infrastructure. Buildings were arranged according to operational needs, forming a legible spatial grid that supported continuous flows of goods and labor.

2024 - Fragmented by Ownership and Obsolescence

Today’s site plan shows a patchwork of vacant plots, active industries, and isolated buildings. The lack of spatial cohesion and public connectivity reflects a site in limbo—rich in potential but disconnected.

By contrast, the 2024 site plan depicts a territory fragmented by disuse and transitional land uses. While the canal still offers strategic connectivity, the surrounding urban fabric exhibits signs of disconnection. Isolated industrial buildings, vast concrete voids, and fenced-off compounds interrupt potential pedestrian continuity. Despite the site’s centrality, it functions as a spatial vacuum within Ghent’s urban tissue—cut off from surrounding

neighborhoods both physically and programmatically. This fragmentation poses not only infrastructural challenges but also cultural ones, as the disjunction between form and function disrupts collective memory and the possibility of reactivation. Addressing this spatial rupture is fundamental to reimagining the dockyards as part of a living urban organism, where continuity can replace isolation.

6.3 Site-Specific Reading: Functional Layering & Memory

Points

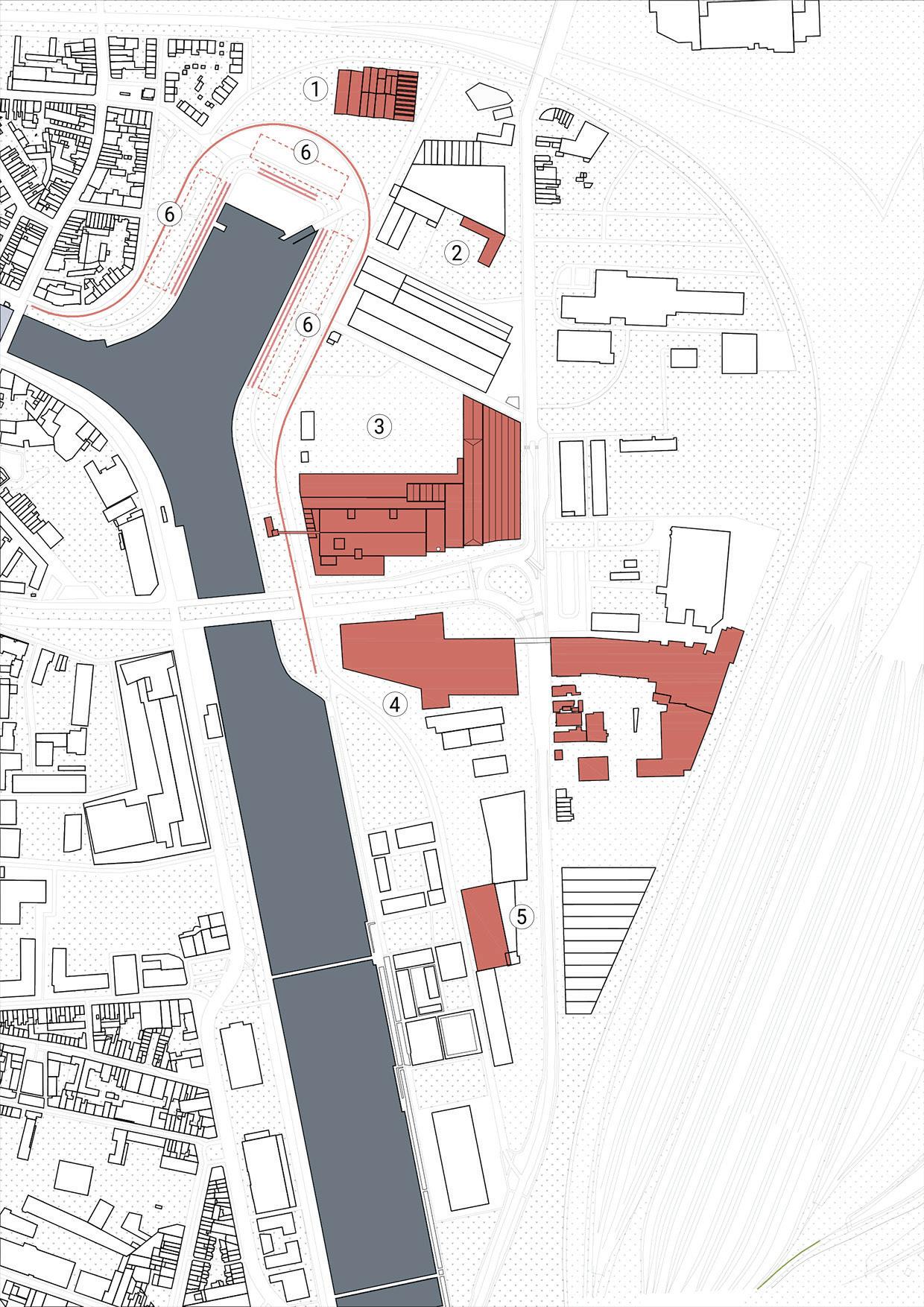

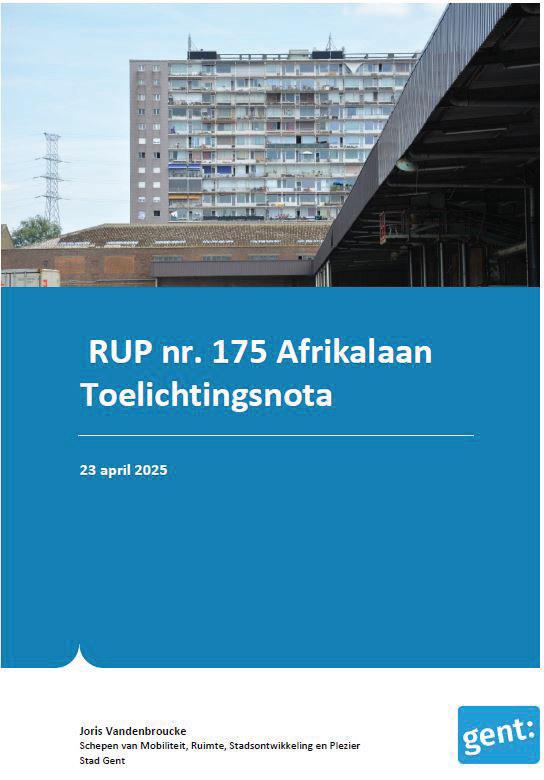

6.3.1. Memory Anchors: Spatial Figures of Collective Significance

The Old Dockyards are layered with architectural fragments that transcend their material presence to embody collective memory and urban potential. This section identifies key structures that serve as spatial anchors, each contributing to the site’s cultural and historical narrative. Together, these structures serve as both spatial markers and mnemonic devices, grounding the design proposal in the physical and symbolic continuity of the site. They frame a cultural palimpsest where architectural intervention can negotiate between preservation and projection.

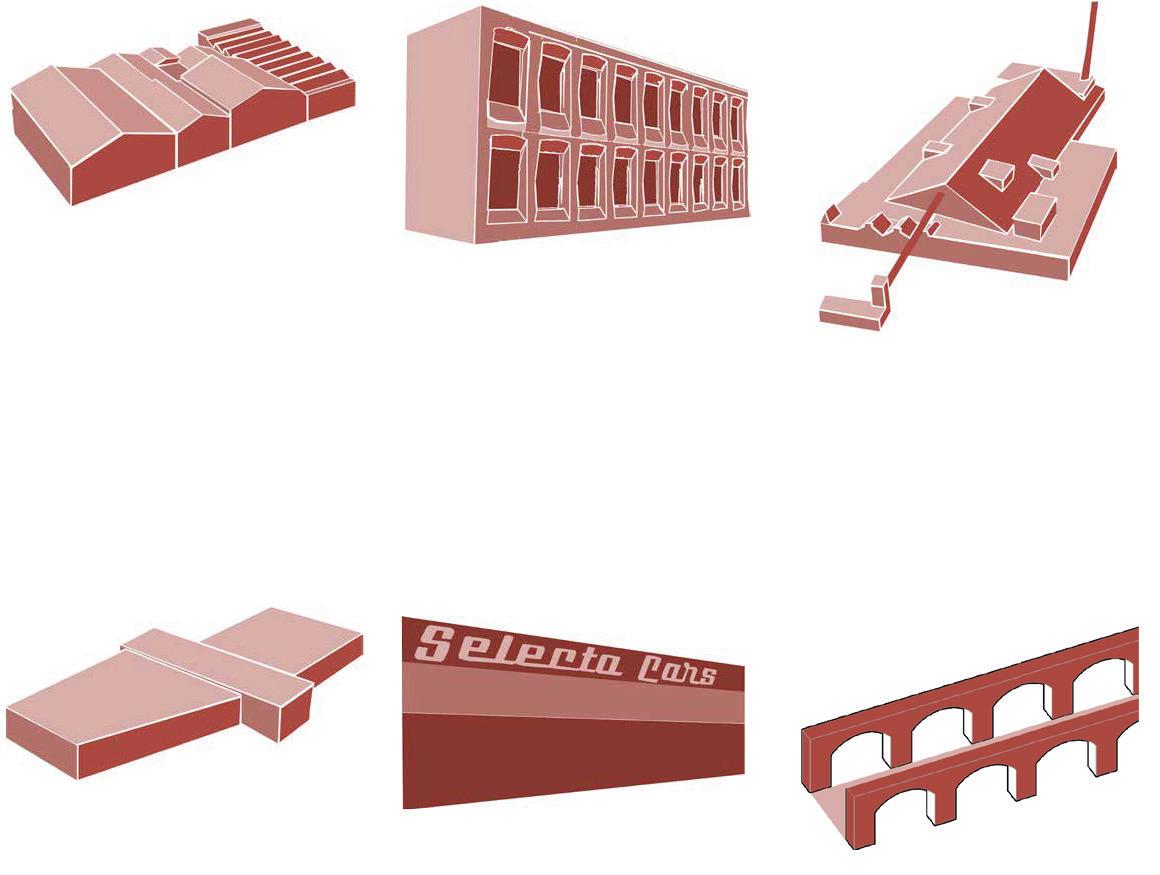

1- Bar Bricolage

A grassroots cultural hub housed in a former factory, embodying bottom-up reuse and demonstrating the site’s latent social vitality.

2 - Wyckaert Comarit Building

A monolithic industrial structure, representative of the architectural austerity and permanence of dock-era production.

3 - Triferto Factory

The central site of investigation, marked by its linear bays, overhead conveyors, and concrete shells. A relic of logistical production, it offers a robust framework for adaptive reuse.

4

- Christeyns SEVESO Site

A functioning Seveso-classified facility, symbolizing both industrial inertia and potential future transformation.

5 - Selecta Cars Building

An underutilized space with speculative reuse value, highlighting the fragmented conditions of current occupancy.

6 - Historic Dockyard

Arches

Brick structures that once supported shipbuilding activities now act as spatial thresholds and narrative artifacts along the waterfront.

6.3.2. Industrial Shells as Functional Archives: The Case of Triferto

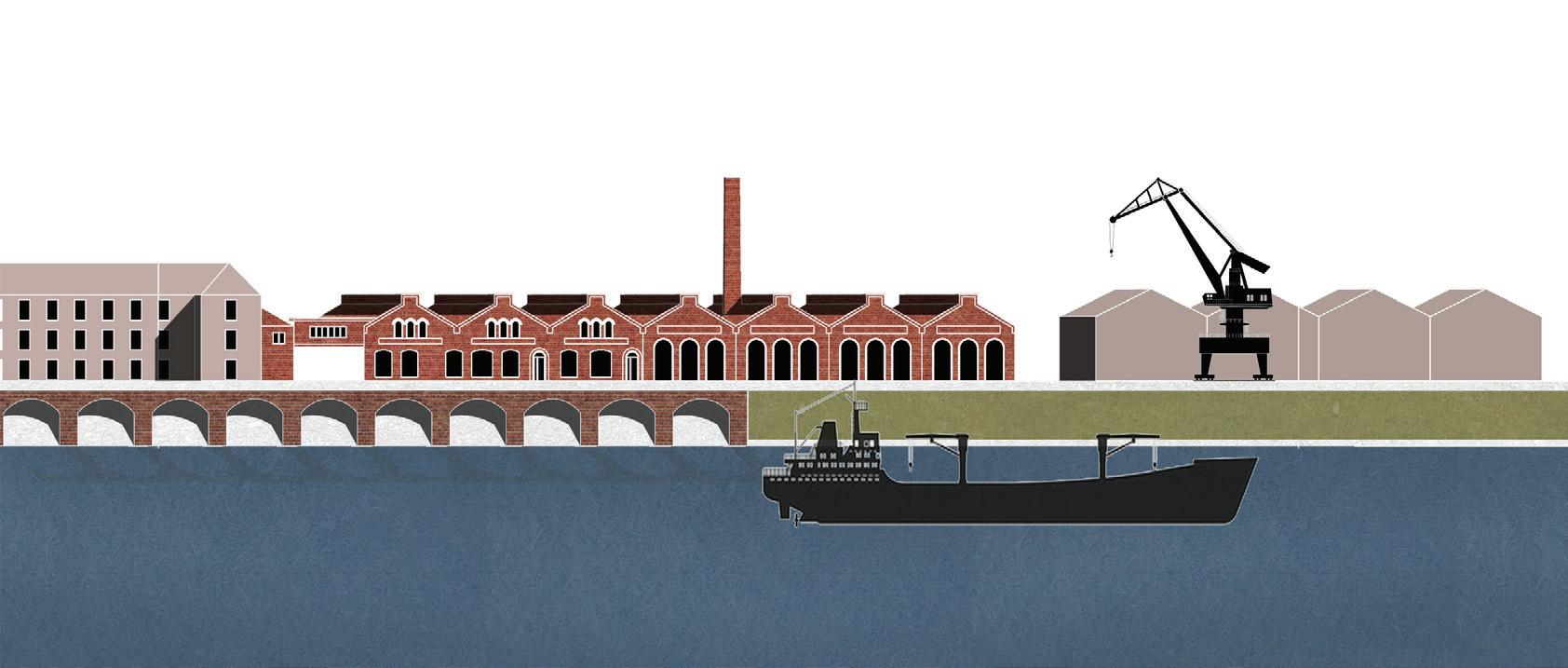

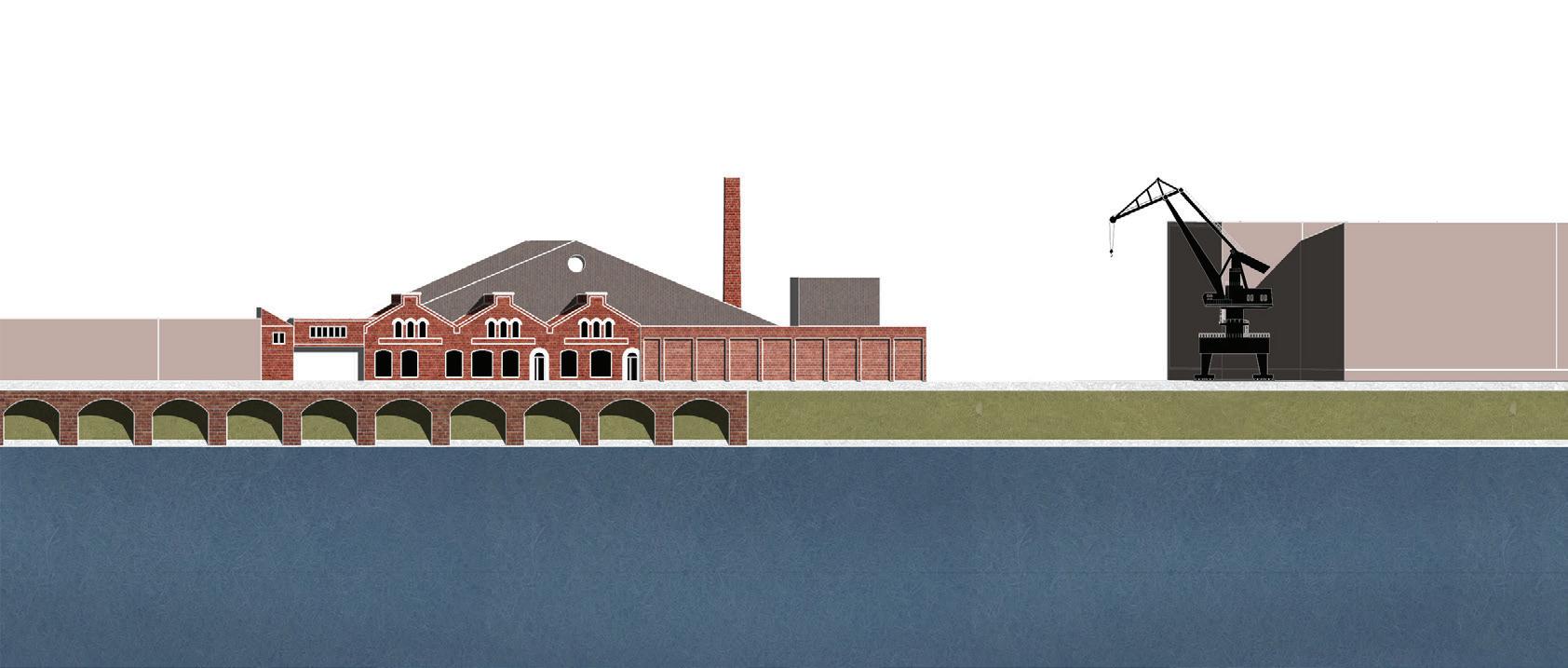

Focusing on the Triferto fertilizer factory, this subsection examines how architectural and infrastructural elements — originally conceived for storage and circulation — can be reimagined as spatial narratives and design devices.

These industrial residues are not static relics, but latent architectural scripts awaiting activation. They offer a grammar of form, material, and memory that informs the thesis’s broader strategy of “cut and insert,” modular overlay, and palimpsestic sectioning. The Triferto site becomes a case study in how adaptive reuse can transmute logistical spatial logic into cultural continuity.

Conveyors

Once used to transport bulk materials across the site, these linear infrastructural paths can become elevated pedestrian routes and programmatic connectors.

Containers

Modular transport units reinterpreted as adaptable micro-pavilions for workshops, exhibitions, or retail functions.

Waterfront Historic Facade

Factory Trusses

Steel structural systems enabling open-span interiors, now appropriated to host flexible public programs.

Chimney

A vertical landmark and symbolic remnant of production energy, offering potential for interpretive or artistic reuse.

A layered brick frontage along the quay, functioning as a memory edge and compositional spine for future additions.

Concrete Bays

Deep storage volumes capable of housing modular insertions and redefined as communal gathering spaces.

Railway Tracks

Vestiges of logistical flow now embedded into the groundscape, forming linear memory lines or green corridors.

Photo 1 by Google Earth, Photos 2-3-5 taken by F. Skåtar, Photo 4 taken by Mohsen Niknejad, 2024.

6.4 Community Needs and Socio-Spatial Gaps

Social Sustainability and Inclusion

The Old Dockyards, though industrially significant, are marked by socio-spatial neglect. This thesis identifies five pressing community needs that should inform the redevelopment strategy:

Lack of Public Spaces

Insufficient communal areas for interaction, culture, and leisure. Multifunctional public spaces are essential to foster cohesion and inclusivity.

Cultural Spaces

The absence of artistic, cultural, and performative spaces limits community expression. Cultural hubs can anchor identity and engagement.

Affordable Housing

Affordable, diverse housing options are critical to ensure a socially resilient neighborhood that accommodates a wide demographic range.

Support For Local Production And Start-Ups

Spaces enabling small-scale entrepreneurship and collective production are crucial to revitalize the postindustrial economy while maintaining the dockyard’s productive memory.

Social Integration

A disconnected urban fabric affects intergenerational and intercultural dialogue. Spatial strategies should bridge physical and social divides.

6.5 Urban and Spatial Connectivity

Despite its central location, the Old Dockyards remain physically and perceptually isolated. Enhancing connectivity is key to reintegrating this fragmented zone into Ghent’s broader network. This section outlines four critical dimensions. These strategies establish the infrastructural groundwork for a masterplan that is not only functional but equitable and culturally embedded. Reweaving the Urban Fabric

Waterfront Access

Reconnecting people to the canalfront through new public interfaces aligns with principles of Waterfront Urbanism.

Green Corridors

Linear green infrastructure should connect the site to the city’s larger ecological system, promoting walkability and leisure.

Pedestrian and Bicycle Networks

Soft mobility strategies—bike lanes, pedestrian promenades—support sustainable transport and draw from New Urbanism principles.

Multimodal Transport Integration

Linking the site with tram, bus, and ferry networks is essential to reduce isolation and support inclusive access.

PART IV — URBAN STRATEGY

7. Masterplan Development: From Policy to Design Intent

7.1 RUP Framework Reference

7.2 Memory Anchors & Spatial Cues

7.3 Strategic Zoning Logic

7.4 Layered Urban Systems

7.4.1. Morphological Rhythm & Spatial Porosity

7.4.2. Green Infrastructure Network

7.4.3. Mobility & Access

7.5 Final Masterplan Visualization

7. Masterplan Development

Masterplan Strategy Overview

The masterplan vision builds upon the analytical insights developed in the previous chapter, transforming urban diagnostics into spatial strategies. Drawing from regulatory frameworks like the RUP and site-specific observations, this section outlines a layered design approach that reinterprets Ghent’s dockyard as a

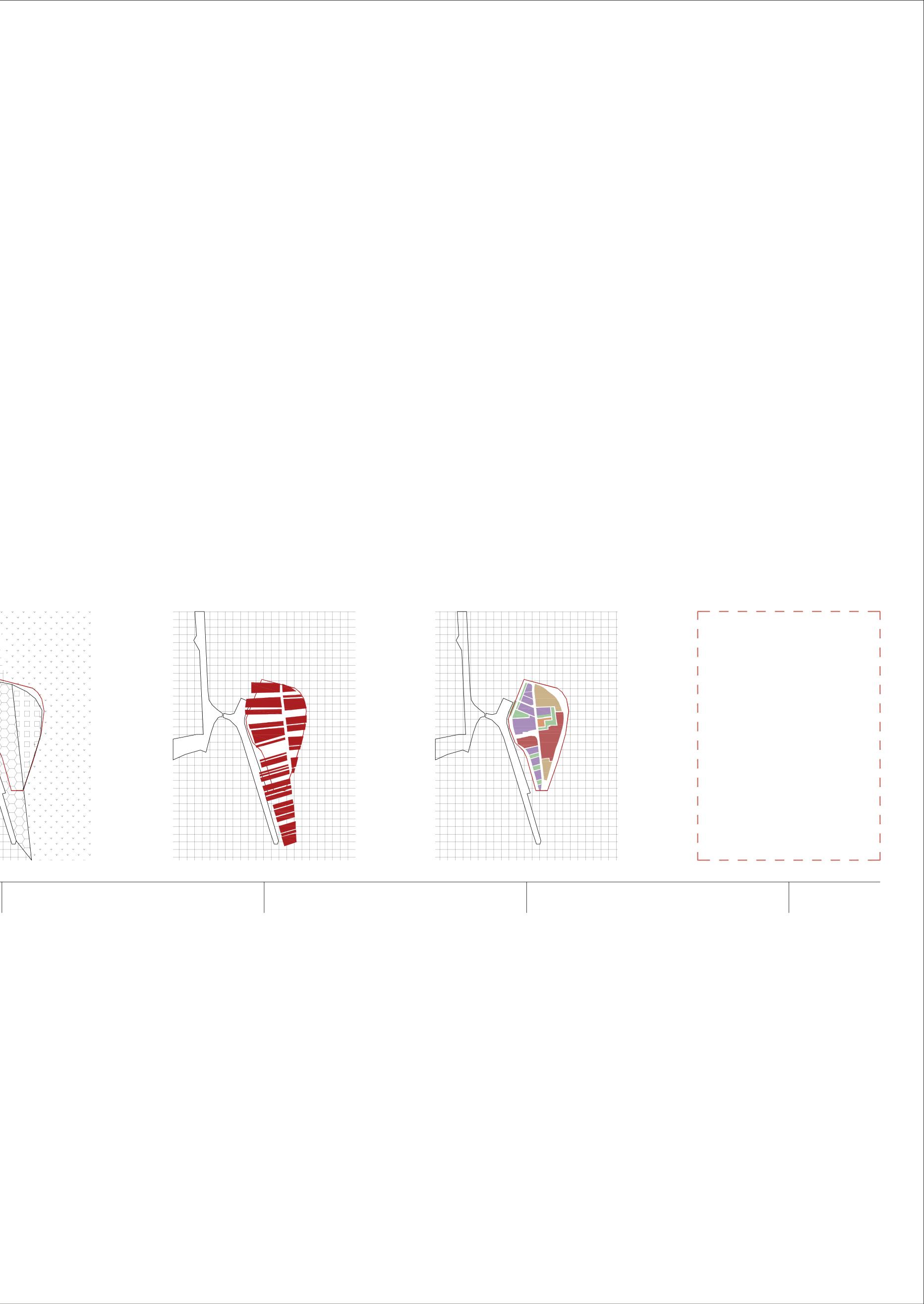

7.1 RUP Framework Reference

To understand the site’s development constraints and opportunities, this thesis refers to the official RUP nr. 175 Afrikalaan framework, a spatial implementation plan approved by the City of Ghent. The RUP outlines zoning designations, infrastructure hierarchies, and ecological buffers, forming the statutory basis for any future transformation.

However, while it sets clear functional categories — such as zones for business, housing, and mixed urban functions — it often neglects existing cultural anchors and fails to integrate post-industrial spatial legacies into its logic.

palimpsestual urban territory. Through the integration of memory anchors, zoning tactics, and infrastructural logic, the proposal aims to reconnect fragmented parts into a coherent, adaptable, and culturally embedded urban fabric.

This thesis proposes a critical reinterpretation of the RUP plan, acknowledging its regulatory structure while revealing its blind spots in addressing memory, spatial porosity, and adaptive reuse.

By re-mapping the graphic plan in a simplified architectural language, the project highlights the friction between policy-driven zoning and lived urban complexity, laying the groundwork for a more narrative and culturally embedded masterplan vision.

Legend – RUP Framework Zones

1- Mixed Urban Functions (Zone voor gemengd stedelijke functies (Z3))

Transitional urban fabric combining residential, commercial, and light public uses.

2- Seveso-Classified Industrial Zone (Zone voor bedrijven-type Seveso met nabestemming (Z1))

Heavy industry zone under safety restrictions; potential future redevelopment subject to mitigation.

3- General Industrial Zone (Zone voor bedrijven (Z2))

Active industrial use areas with limited public accessibility.

4- Urban Residential Zone (Zone voor stedelijk wonen (Z4))

Mid-density residential neighborhoods with potential for urban integration.

5- Public Green & Park Zone

(Zone voor openbaar park / park (Z8))

Areas designated for public open space, green buffers, and recreation.

7. Masterplan Development

7.2 Memory Anchors & Spatial Cues

The proposed masterplan begins not with abstraction, but with the material memory embedded in the site. Certain structures—such as the Triferto Factory, Bar Bricolage, Christeyns complex, and remnants of the dockyard arches—act as memory anchors. These buildings retain spatial, historical, and social significance, making them more than physical residues: they become cultural signposts.

Rather than erasing or replacing, the design reads these structures as initiators of urban strategy. Their position, scale, and past functions inform

spatial organization, programmatic clustering, and architectural vocabulary. Even abandoned or utilitarian elements—like the Selecta Cars building or Wyckaert warehouse—contribute as spatial cues, offering orientation within a fragmented landscape.

This memory-based approach repositions preservation as a proactive design tool. By mapping symbolic density and architectural relevance, the masterplan develops organically from within the site, aligning urban intentions with embodied history.

3 - Triferto Factory

1- Bar Bricolage

4 - Christeyns SEVESO Site

6 - Historic Dockyard Arches

2 - Wyckaert Comarit Building

5 - Selecta Cars Building

7. Masterplan Development

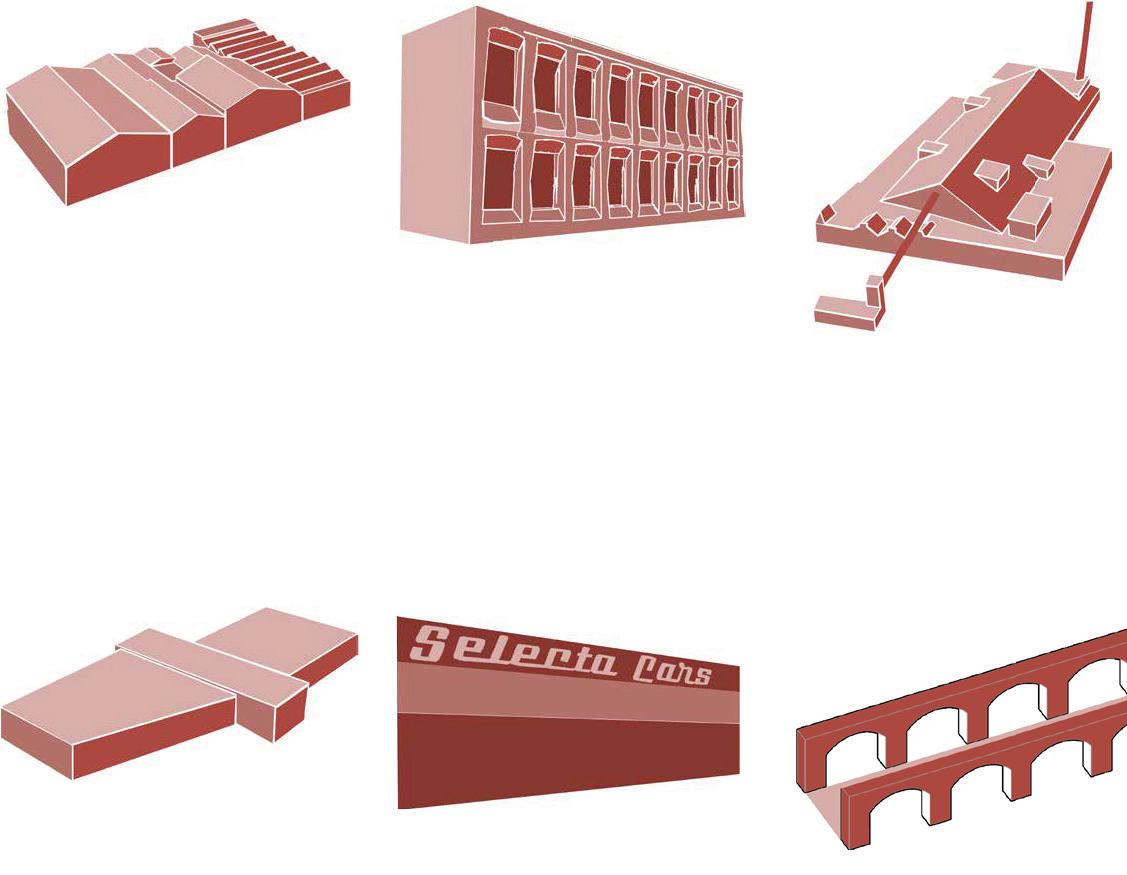

7.3

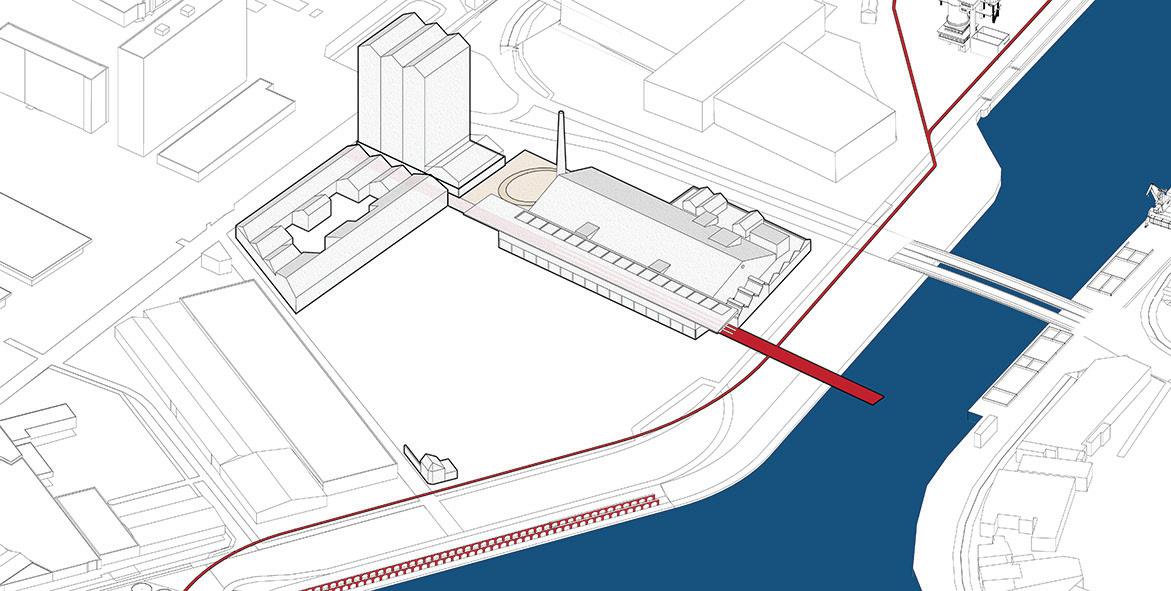

Strategic Zoning Logic

The masterplan organizes the site into seven distinct zones, each with a tailored identity rooted in spatial character, programmatic needs, and adaptive reuse potential. Rather than applying a uniform logic, the zoning reflects the diverse morphologies and memory anchors embedded across the site.

From the porous Urban Gateway that mediates city entry, to the Logistic Legacy Platform repurposing scale-heavy warehouses, each zone responds to its spatial DNA and social context. The zoning structure

balances continuity and contrast—combining civic permeability, production heritage, and new communal aspirations. Transitional zones like the Craft Line and Southern Urban Strip facilitate productive overlaps between housing, culture, and fabrication.

This zoning strategy avoids rigid land-use divisions. Instead, it promotes gradient programming, micro-centralities, and narrative layering across the masterplan, allowing past and future functions to coexist dynamically.

Zone 1 – Urban Gateway

This zone serves as the northwestern threshold to the site, adjacent to the city’s active edge. It proposes a transition from dense urbanity to adaptive reuse through small-scale housing and localized public programs. Designed with a porous edge and pedestrian focus, the Urban Gateway invites gradual integration and mixed activation.

Zone 2 – Cultural Core (Triferto Factory)

Centered on the preserved fertilizer factory, this zone is reimagined as a cultural and memory vessel. The Cut & Insert strategy activates the industrial shell with modular insertions, enabling public workshops, exhibitions, and performances. The factory becomes a spatial archive—retaining its material presence while supporting contemporary civic life.

Zone 3 – Southern Urban Strip

Located along the southern canal edge, this zone engages directly with water and urban frontage It introduces medium-density housing, open production platforms, and public plazas. As a linear system, it reclaims the canal as a social spine— restitching the waterfront into the urban fabric through housing and making.

7. Masterplan Development

7.3 Strategic Zoning Logic

Zone 4 – Community Plateau

Positioned in the northeastern triangular parcel, this zone envisions a neighborhood-oriented cluster. Focused on collective living and smallscale production, it integrates social housing, community gardens, educational spaces, and childcare facilities. The plateau becomes a testbed for inclusive urbanism rooted in everyday life.

Zone 5 – Craft Line

Running parallel to the central Seveso zone, the Craft Line fosters light industry, artisanal production, and entrepreneurial spaces. Its linear configuration allows for modular maker spaces, shared workshops, and flexible studios—reviving the productive spirit of the site with human-scaled fabrication and social interaction.

Zone 6 – Mixed Urban Grid

Corresponding to the existing Z3 zone in the RUP plan, this area supports a hybrid morphology of housing, commerce, and services. Its orthogonal layout facilitates phased development while enabling permeability and adaptability. As a transition zone, it blends residential needs with low-intensity public programs and community anchors.

Zone 7 – Platform 7 / Logistic Legacy

Situated along the southeastern rail edge, this zone transforms dormant logistical structures into adaptable civic platforms. Former warehouses, train docks, and container spaces are reprogrammed for event hosting, open-air markets, and temporary exhibitions—channeling industrial inertia into cultural energy.

7. Masterplan Development

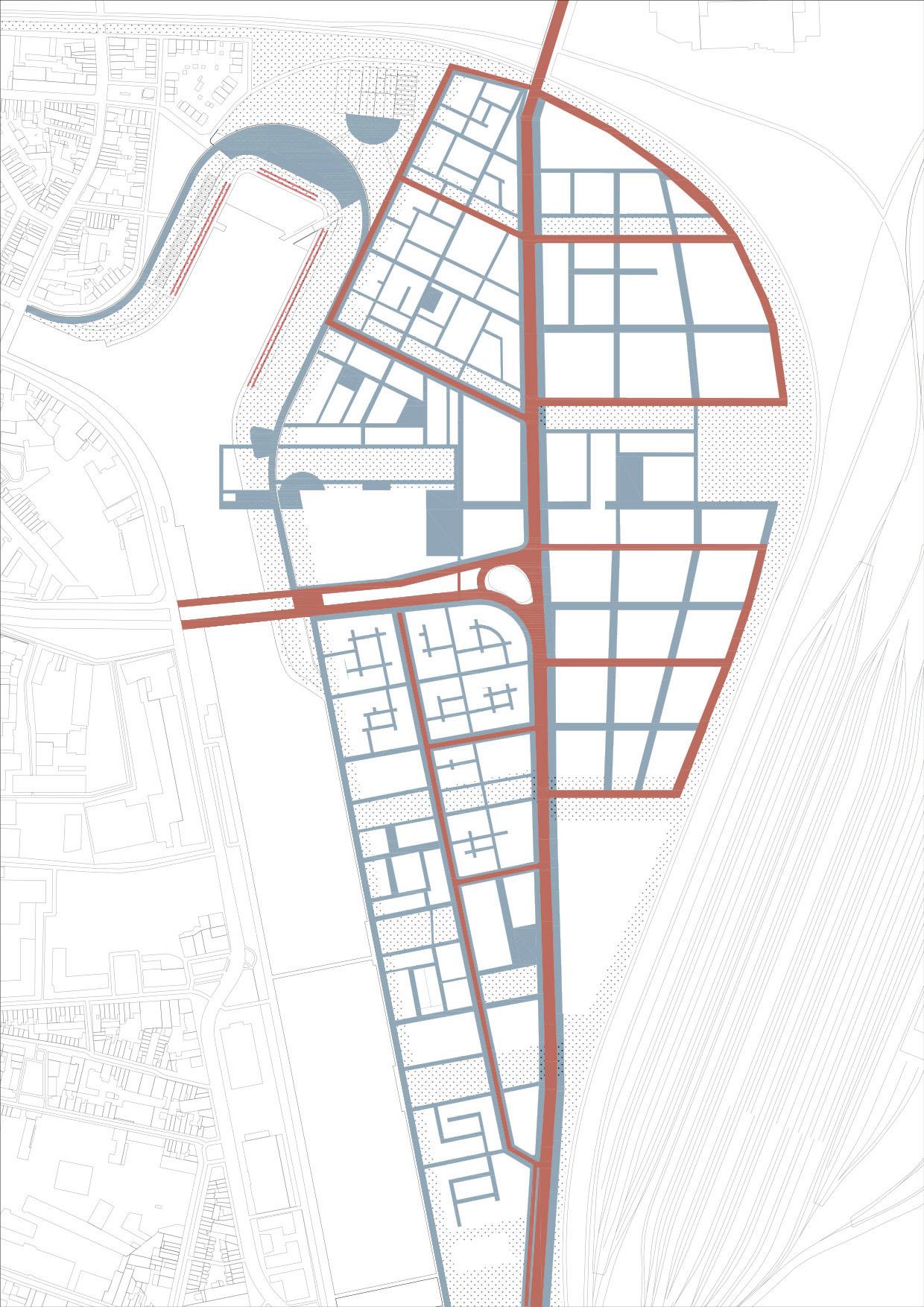

7.4 Layered Urban Systems

The proposed masterplan is not a singular formal gesture, but a composite system composed of interrelated spatial layers. These layers work in synergy to balance ecological resilience, functional logic, and spatial porosity—each informing the zoning strategy and architectural potential. A combined diagram

overlays these three layers into one composite visual, articulating the hidden logics that shape the urban strategy. Together, they demonstrate how design moves beyond aesthetics to choreograph social, ecological, and spatial performances.

7.4.1. Morphological Rhythm & Spatial Porosity

The final spatial articulation of the masterplan translates zoning principles into a legible built fabric— one that balances density, diversity, and permeability. Each zone develops a distinctive morphological rhythm that echoes its programmatic intent, spatial history, and human-scale responsiveness.

From the Urban Gateway (Zone 1) to Platform 8 (Zone 8), the masterplan avoids a uniform massing strategy in favor of context-sensitive typological variation. Small-scale residential clusters in the north dissolve into porous courtyard blocks; the preserved industrial shell of Zone 2 becomes a void-anchored cultural condenser; while Zone 6 and Zone 7 demonstrate modular repetition suited to incremental infill and civic adaptability.

The Southern Urban Strip (Zone 4) deploys alternating linear volumes to reinforce water frontage continuity, while Zone 8 reuses larger logistic volumes as hybridized public platforms.

Porosity is achieved not merely through voids, but through sectional nuance—lower buildings frame pedestrian corridors, transitional pockets open into collective courtyards, and spatial variety ensures micro-climatic and social responsiveness. This fragmented-yet-coherent urbanism echoes urban theorist Richard Sennett’s call for “open forms” (2018), offering flexibility without sacrificing identity. In sum, the morphology does not impose a rigid visual order but curates a spatial field of negotiated intensity—welcoming difference within a shared spatial language.

7. Masterplan Development

7.4 Layered Urban Systems

7.4.2. Green Infrastructure Network

The green system proposed for the Old Dockyards follows a dual logic: a continuous linear spine and localized collective greens.

The first layer (7.4.1-1) establishes a green backbone — a thick vegetated strip running parallel to the waterfront and looping into the neighborhood blocks. It connects fragmented parcels and delineates movement corridors, buffering industrial and residential functions. Acting as an ecological spine, it extends the city’s larger green-blue network, promoting continuity and environmental resilience.

The second layer (7.4.1-2) introduces a system of collective green pockets — distributed green spaces within residential grids and production-adjacent zones. These spaces respond to local needs, functioning as recreational, social, and productive commons.

In the composite diagram, the overlap of these two layers creates a porous green fabric that anchors the masterplan’s spatial logic. Rather than applying a uniform park typology, the proposal weaves green infrastructure through existing morphological rhythms, ensuring both ecological function and social accessibility.

7.4.2.1 The First Layer

7.4.2.2 The Second Layer

7. Masterplan Development

7.4 Layered Urban Systems

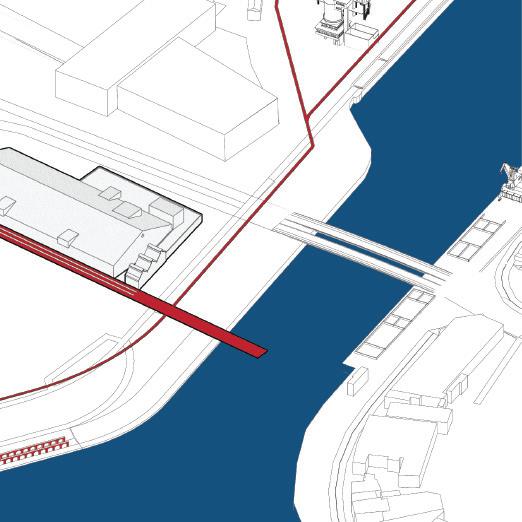

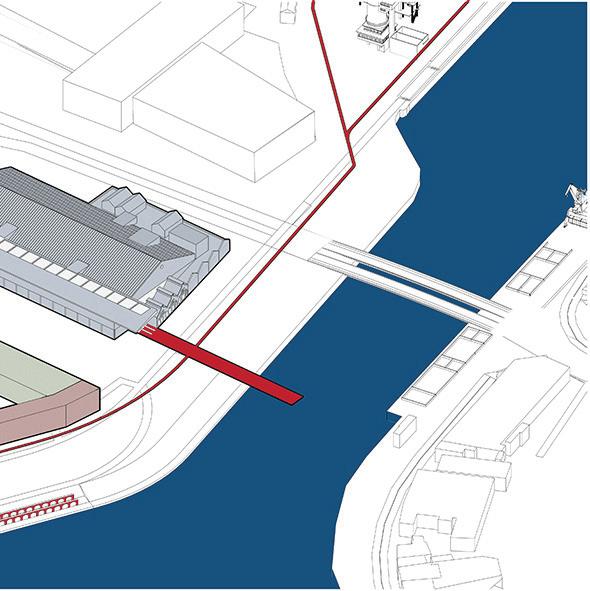

7.4.3. Mobility & Access: Toward a Layered, Human-Centered Network

The mobility framework proposed for the Old Dockyards repositions circulation not as a residual infrastructural necessity but as a core design tool that mediates between historical legacy and futureoriented spatial equity. In line with contemporary urban theories that prioritize walkability, slow mobility, and transit-oriented development (Gehl, 2010; Calthorpe, 1993), the project articulates a dual-layered network: vehicular containment and pedestrian-bicycle permeability.

The vehicular layer (7-4-2-1) is strategically minimized to reduce fragmentation and ecological load. Only essential routes are preserved—primarily those serving remaining industrial programs or connecting urban edges. These streets are designed for reduced speed and adaptive reuse, where appropriate, as shared surfaces. This approach aligns with the “filtered permeability” model advocated by sustainable mobility theorists (Melia, 2010), whereby car access is permitted but not privileged.

7.4.2.1

The Vehicular Containment

The pedestrian and bicycle layer (7-4-2-2) establishes a continuous and legible north-south spine that links the site with the broader cycling network of Ghent. This spine supports cultural nodes, public parks, and waterfront transitions, and follows Jacobsian principles of street vitality through “short blocks, frequent turns, and mixed destinations” (Jacobs, 1961). East-west connectors refine this framework by ensuring micromobility within and across zones, reinforcing the principle of “urban porosity” (Sennett, 2018)

A key moment of convergence occurs near the southern edge of the Triferto Factory, where a new vehicular bridge, currently under construction, intersects the site. While its design lies outside the scope of this project, its presence is embraced as an infrastructural given. Rather than opposing the road, the project reframes it as a civic condition to be adapted and mediated.

7.4.2.2

The Pedestrian - Bicycle Permeability

7. Masterplan Development

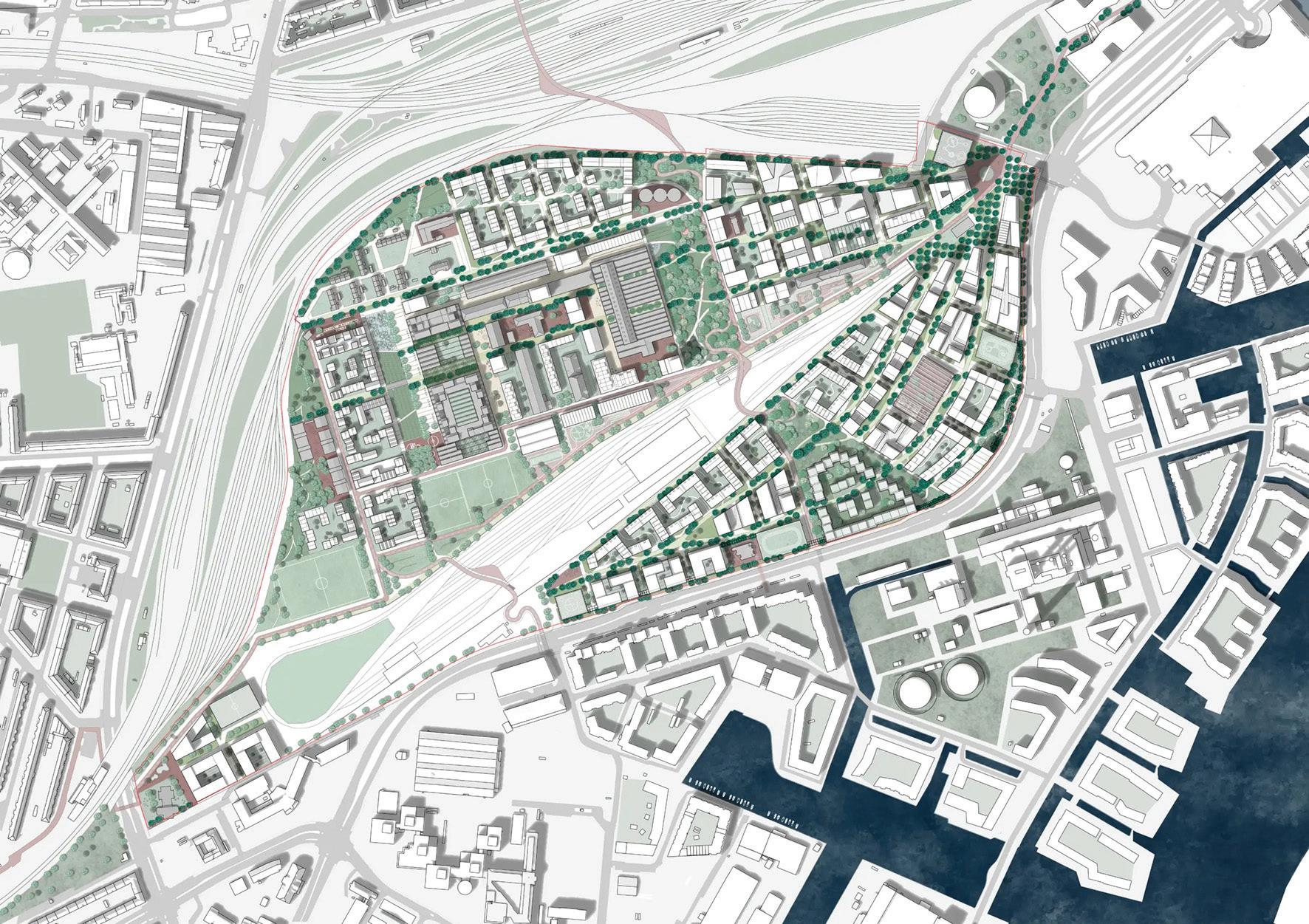

7.5 Final Masterplan Visualization

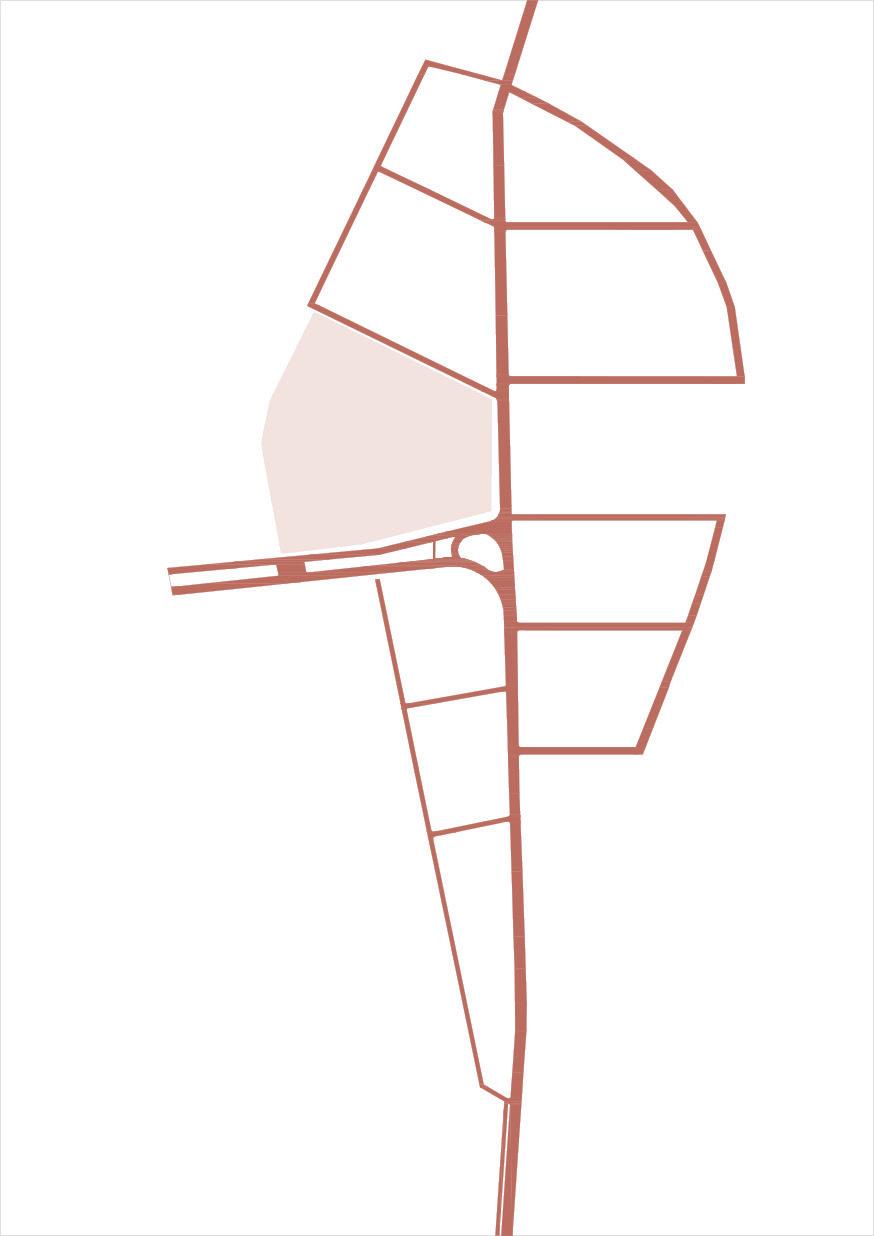

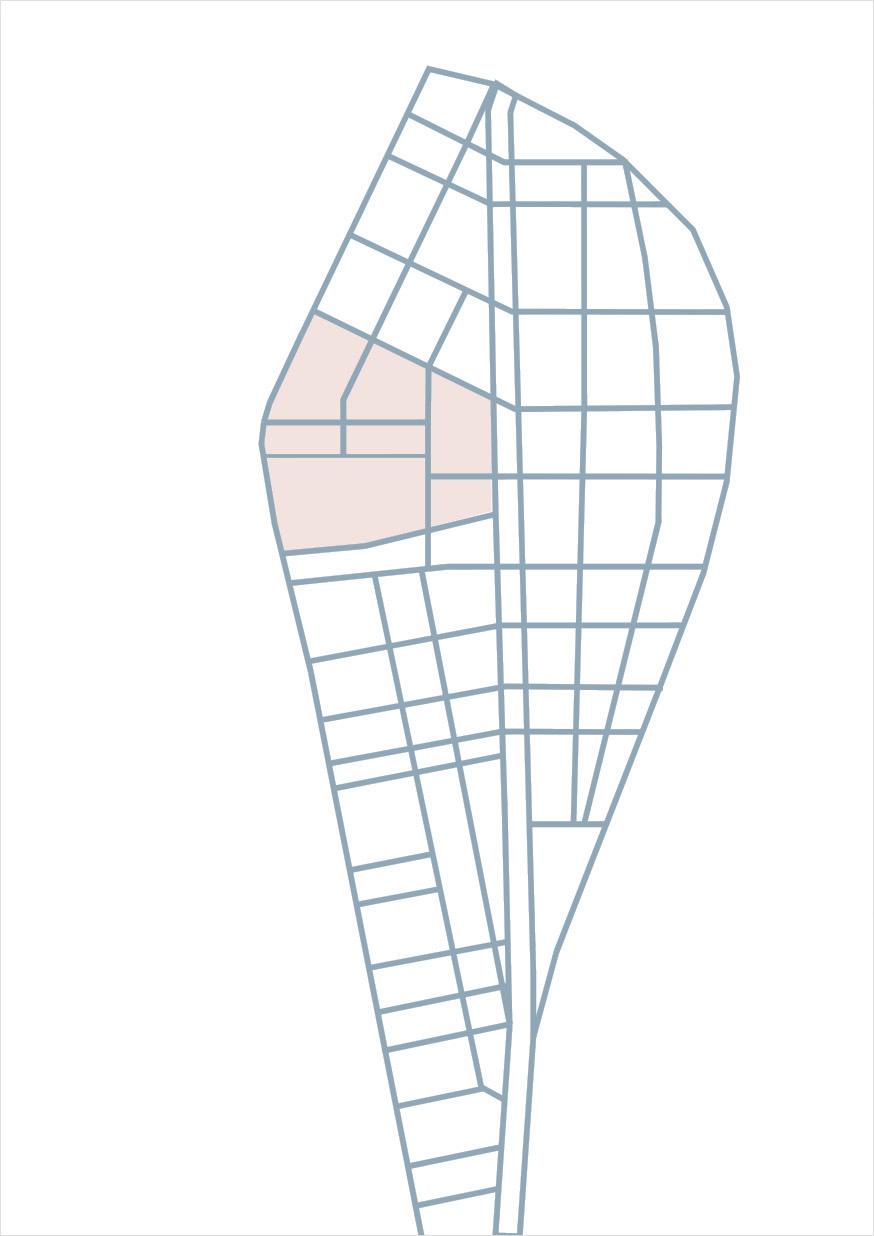

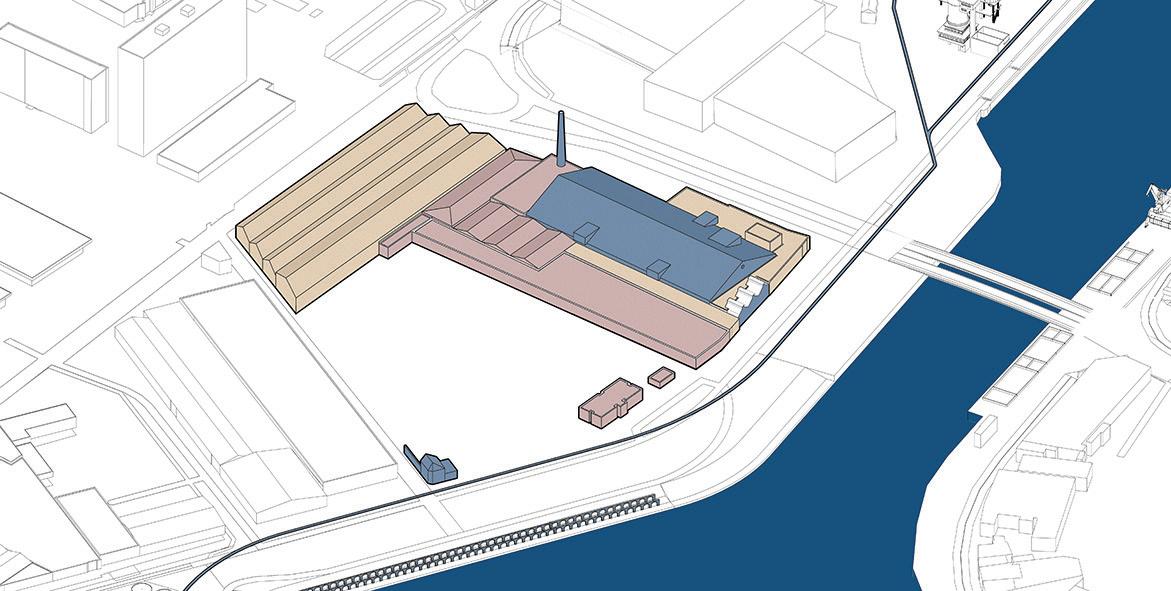

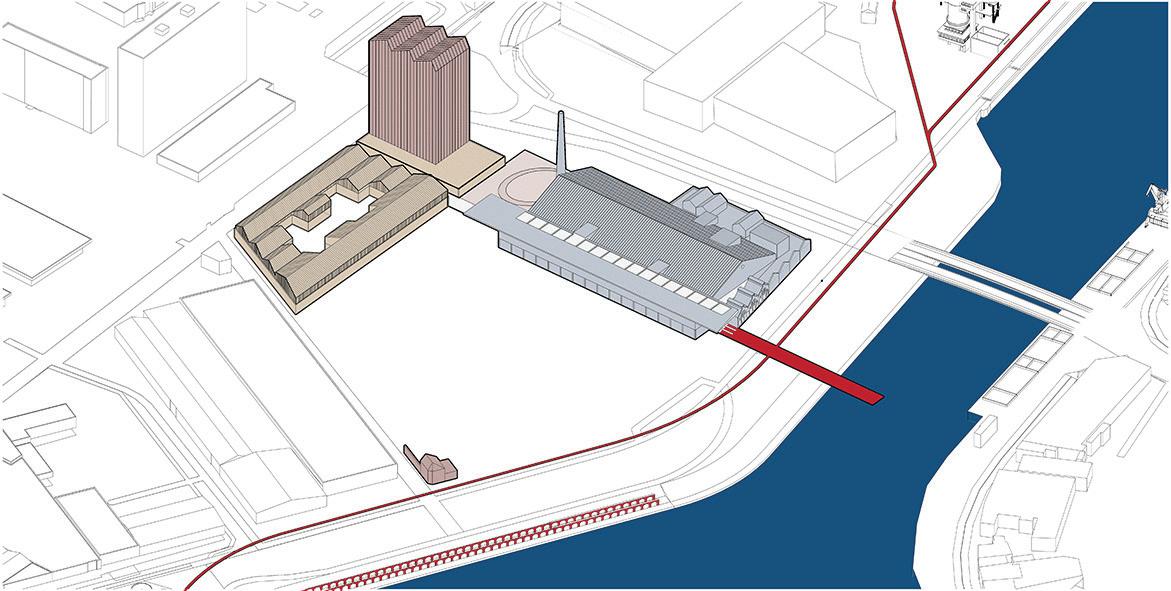

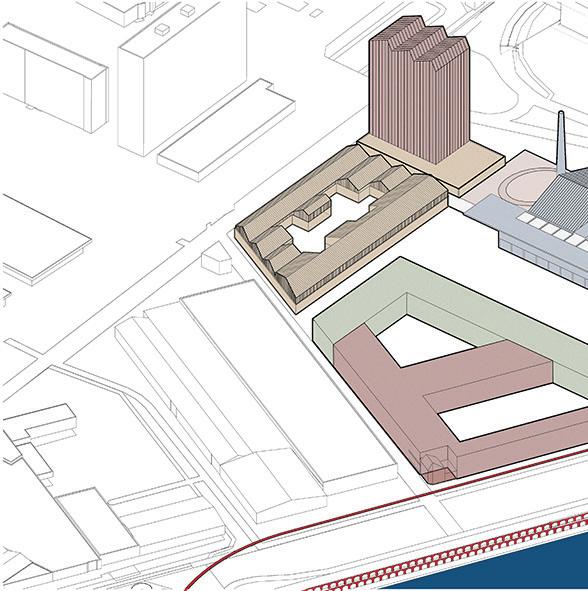

This section presents two alternative masterplan scenarios that synthesize the proposed urban strategies into a coherent spatial framework.

Both are drawn at 1:5000 scale and reflect the integration of zoning logic, green and mobility networks, and morphological principles.

7.5.1. Scenario A: Seveso Redevelopment Option

This version assumes the eventual relocation or decommissioning of the Seveso-classified chemical facility (Zone 3), enabling its transformation into a porous cultural and public landscape. The removal of industrial risk unlocks a continuous green corridor

linking the waterfront to the eastern neighborhoods. Public spaces, cultural nodes, and light civic programs densify the core, making this scenario the fullest realization of the proposed urban porosity.

7. Masterplan Development

7.5 Final Masterplan Visualization

7.5.2. Scenario B: Seveso Retained (Buffer Condition)

This alternative retains the current Seveso site as an active industrial enclave. The masterplan adjusts accordingly by strengthening edge buffers, introducing landscape screening, and programming adjacent zones with lower intensity uses.

Despite the constraints, the proposal maintains connectivity and vibrancy through transitional programs and controlled permeability. This demonstrates the plan’s adaptability to real-world policy and infrastructural inertia.

PART V — ARCHITECTURAL INTERVENTION

8. Architectural Proposal: The Factory as Memory Vessel

8.1 Design Evolution in Six Steps

8.2 Core Strategies: Conveyor, Cut & Insert, Container

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

8.3.1 Original Functional Diagram

8.3.2 Preserved and Added Elements

8.3.3 New Programmatic Zones

8.3.4 Upper Floor Circulation Bridges

8.3.5 Placing Containers for Reuse

8.3.6 Second Floor Circulation Bridges

8.3.7 Third Floor Conveyor Walkway

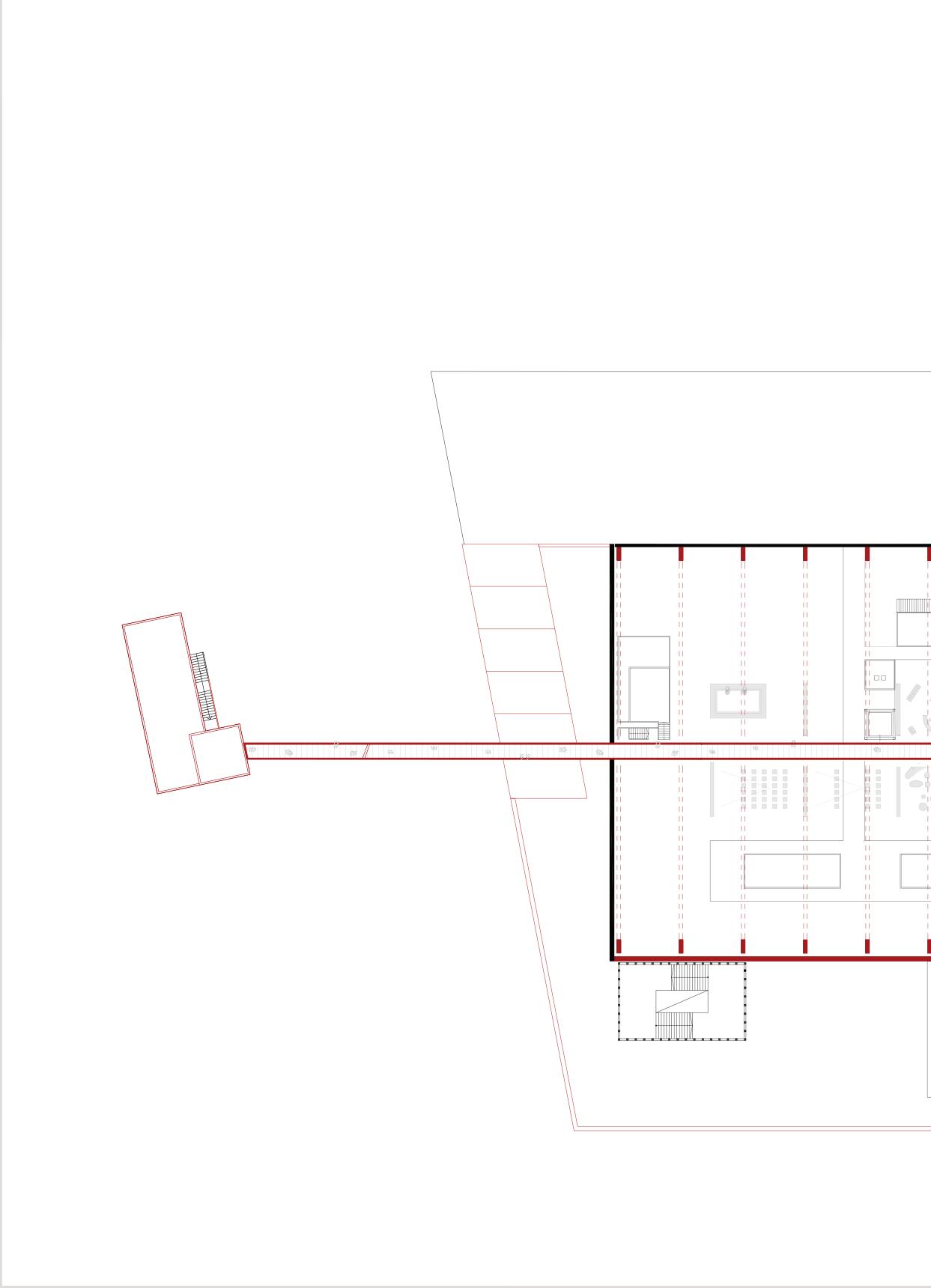

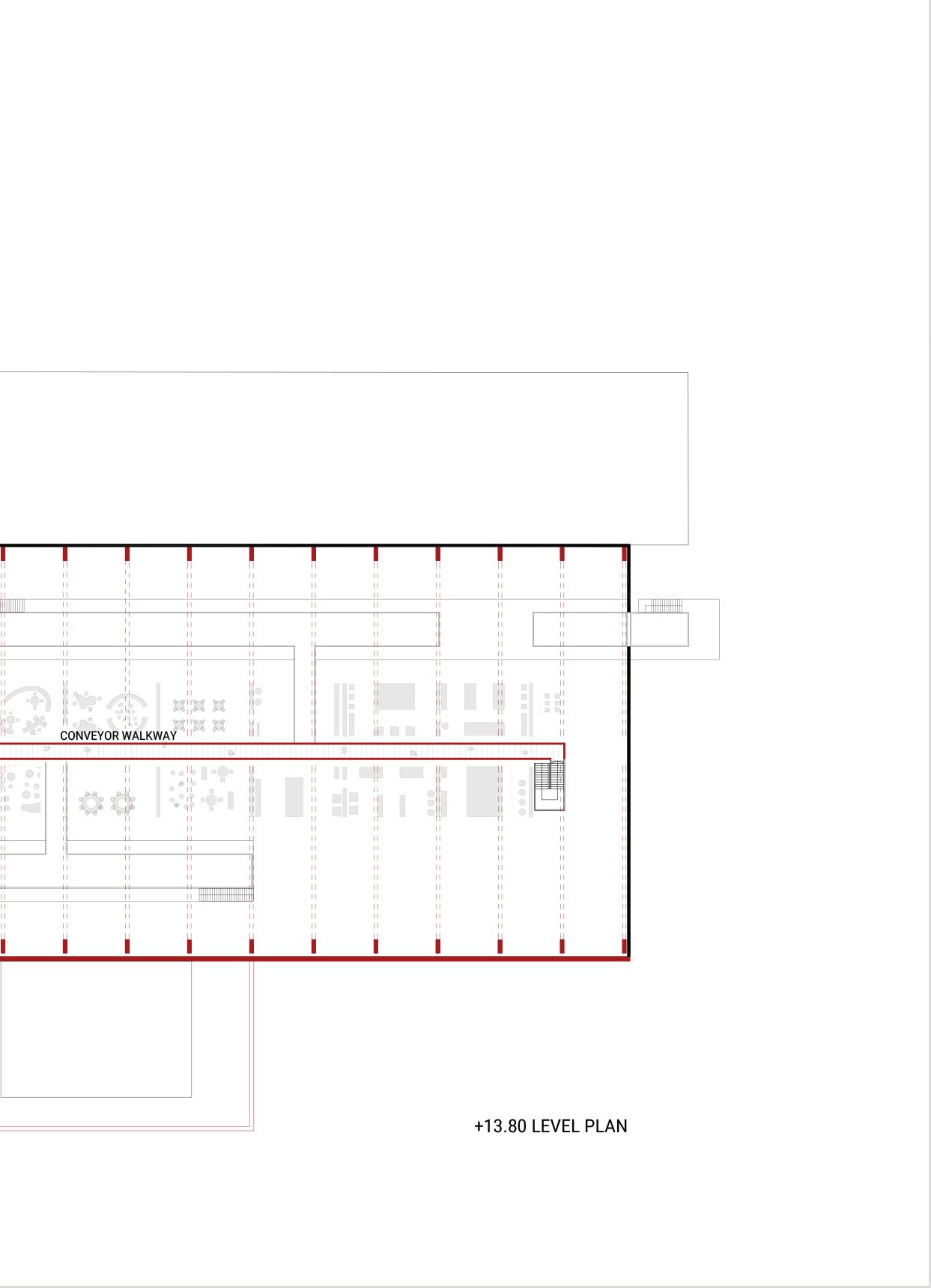

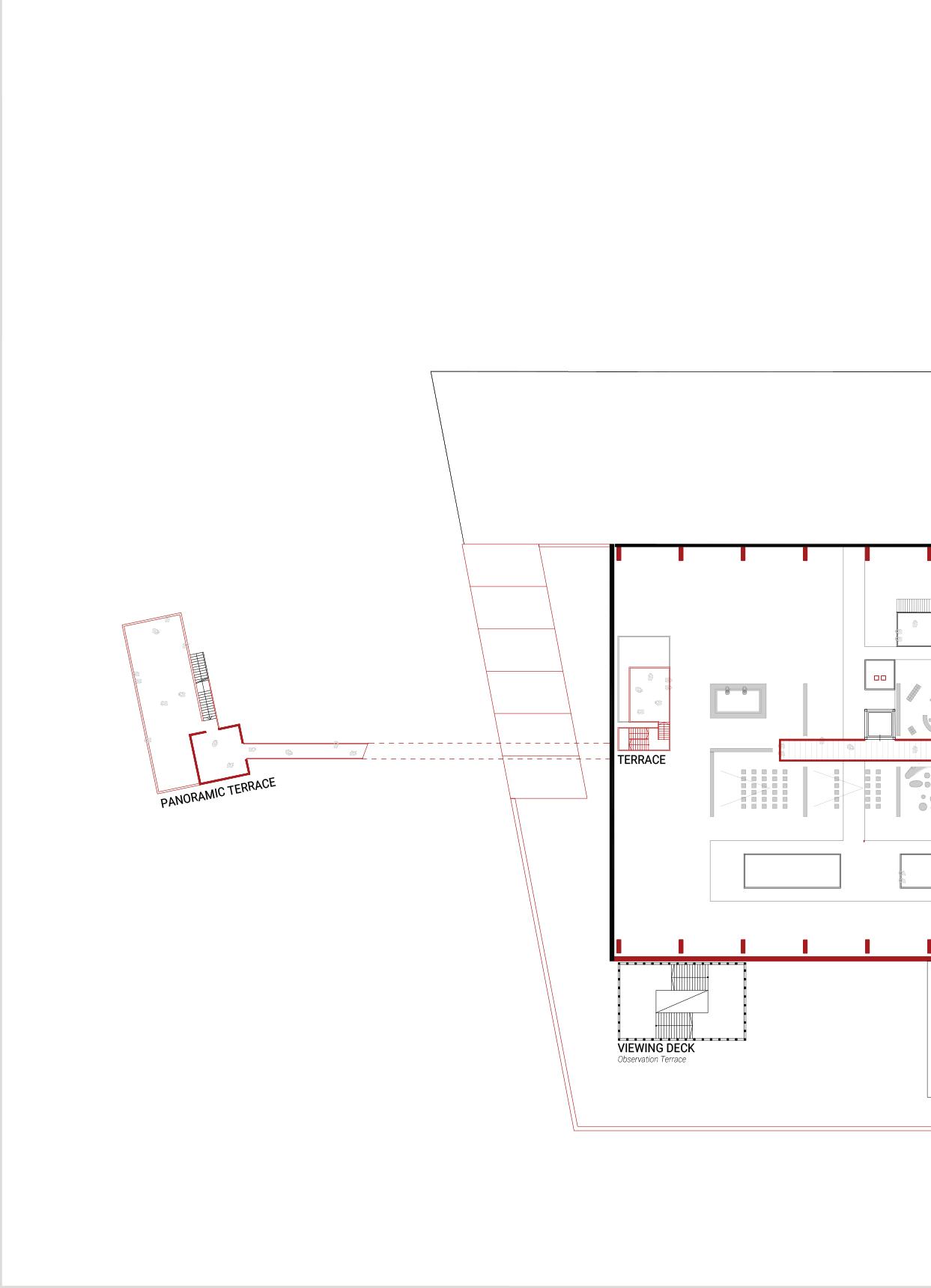

8.4 Architectural Floor Plans

8.5 Site Plan

8.6 Visualizations

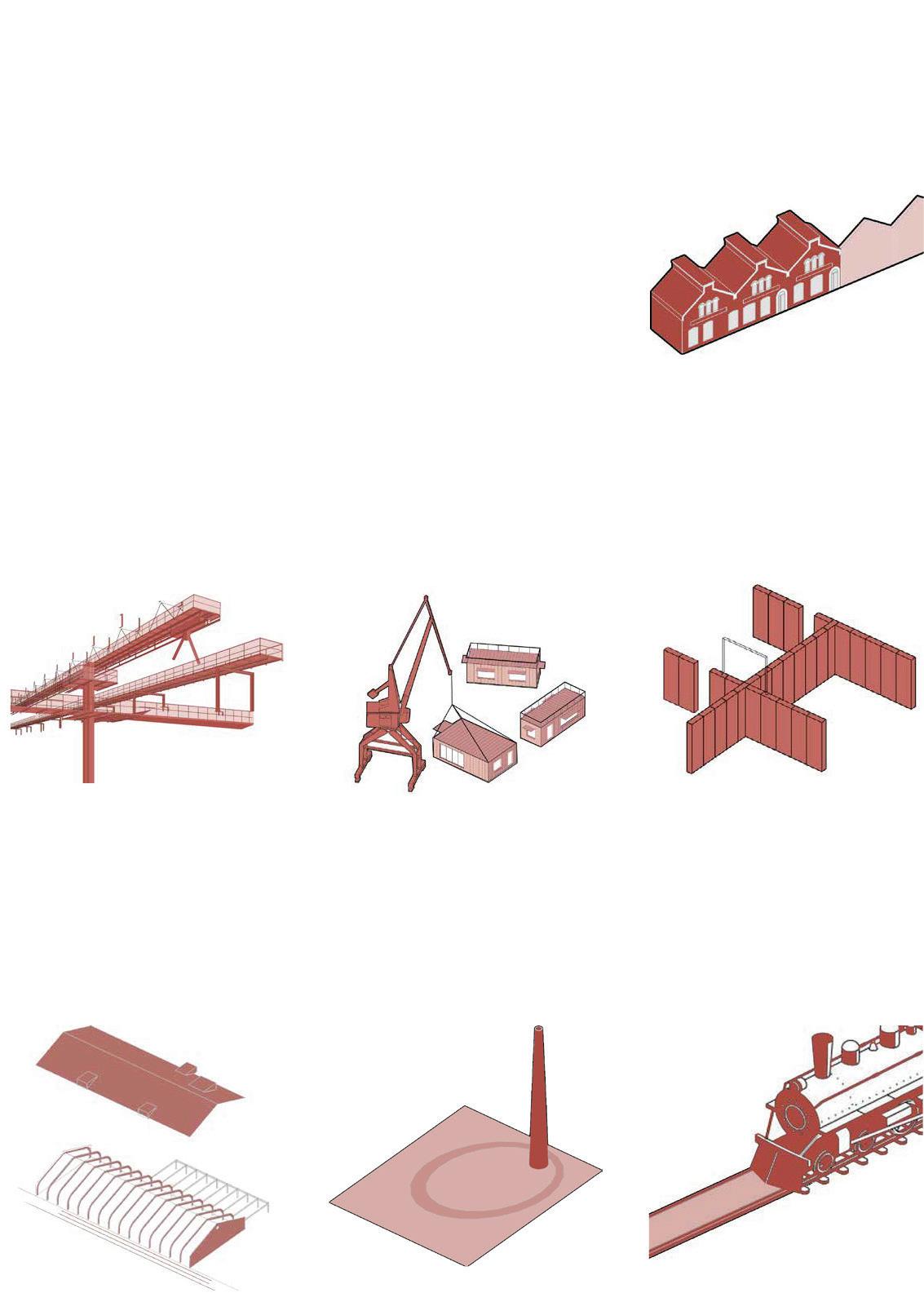

8. Architectural Proposal

8.1

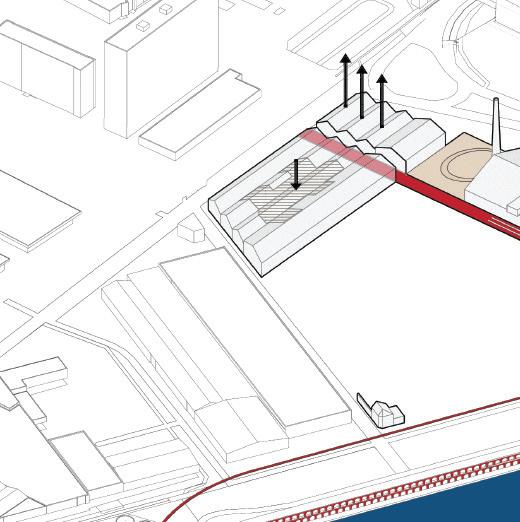

Design Evolution in Six Steps

The architectural transformation of the Triferto Factory unfolds through a six-phase design sequence that synthesizes memory, materiality, and urban strategy. Rather than proposing a single, static solution, the process activates an incremental methodology, reflecting both the layered industrial past of the site and its civic potential.

1. Repurposing Key Buildings

The intervention begins with the selective retention of significant structures— those with architectural, spatial, or logistical value. These form the initial anchors of the project, setting the tone for an adaptive reuse logic that values historical continuity without freezing the past.

4. Activation

With spatial armatures in place, the site is infused with use and rhythm. Color-coded massing reveals a diversified functional program—public workshops, cultural venues, and community amenities—each embedded within a porous, walkable layout. Ground-level permeability and edge activations ensure daily social interaction and neighborhood-scale vibrancy.

2. Intervention

Through targeted operations of incision, the proposal implements the “Cut partially removed, volumetric voids are are carved, enabling light, flow, and between preservation and innovation

5. Human-Centric Design

The plan embraces a sensitive urban transitions, and informal edges. New the factory’s central garden, framing sightlines. Emphasis is placed on slow line with contemporary placemaking

3. Integration

incision, addition, and reprogramming, & Insert” strategy. Interior walls are are introduced, and new access points and flexible use. The project negotiates at multiple scales.

urban grain, with compact blocks, visible New volumes are introduced around framing shared courtyards and preserving slow mobility and layered publicness, in principles.

A major infrastructural gesture defines this phase: the old rail line, which once cut through the factory for logistical purposes, is reimagined as a civic spine. This linear axis now connects the urban edge to the waterfront, acting as a structural and symbolic organizer for both circulation and programmatic distribution.

6. Final Configuration

The final outcome presents a hybrid landscape of memory and projection. The historic skeleton is preserved, new architectural fragments are carefully inserted, and infrastructural traces are redefined into connective tissue. The project emerges not as an object but as an evolving system—anchored in context, open to use, and rich in spatial narrative.

8. Architectural Proposal

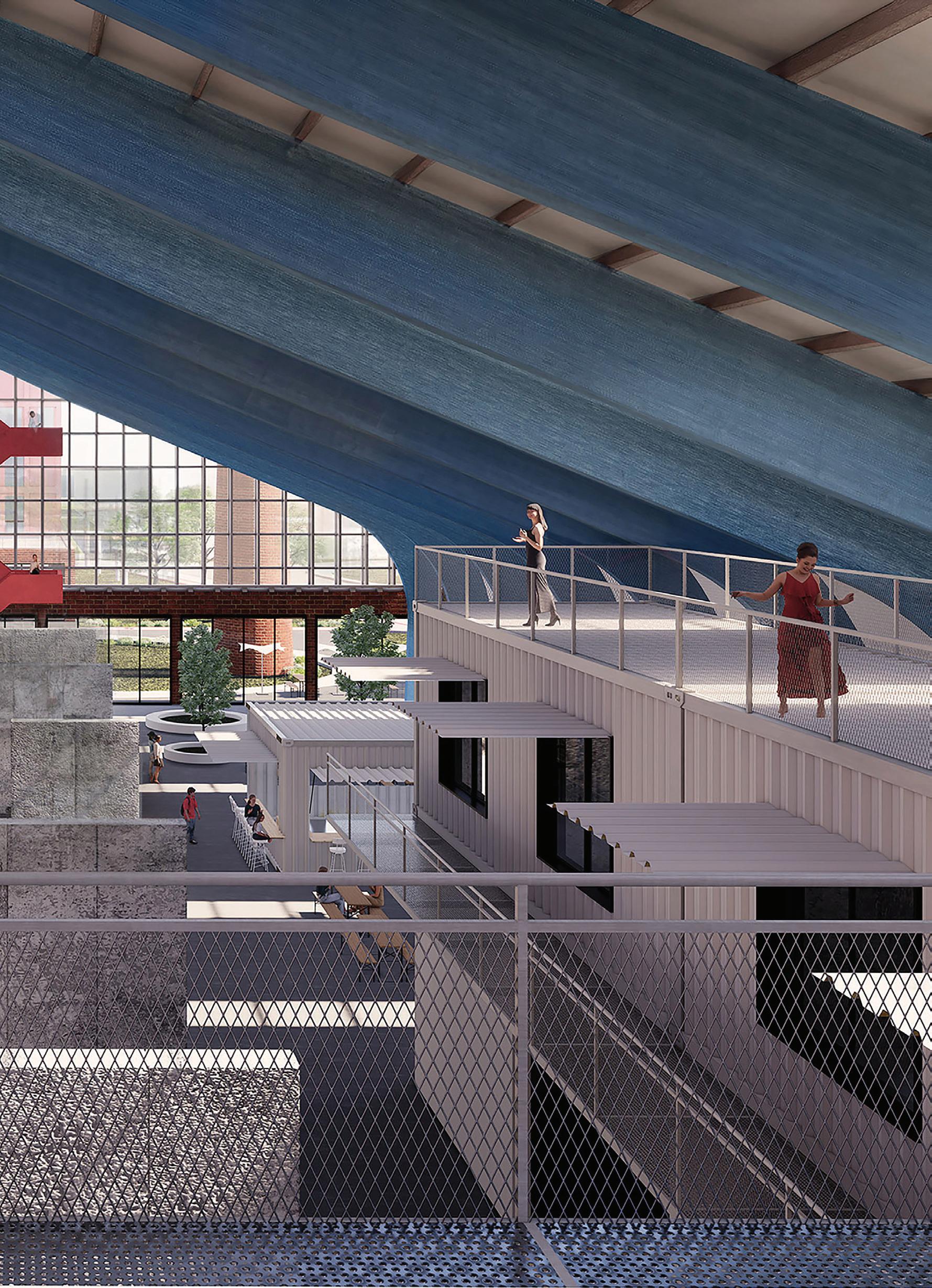

8.2 Core Strategies: Conveyor, Cut & Insert, Container

Reinterpreting Industrial Circulation

The architectural proposal is structured around three interdependent strategies—Conveyor, Cut & Insert, and Container—each extracted from the site’s industrial DNA and redefined through the lens of cultural reuse.

C-3 STRATEGIES

Together, they orchestrate a shift:

From Material to People From Product to Culture From Transport to Interaction From Storage to Memory

Conveyor: From Transport to Interaction

The existing overhead conveyor system, once central to the logistical choreography of fertilizer distribution, is reappropriated as a suspended walkway and connective artery. Its linearity becomes a device for narration, offering panoramic views and transitional experiences. As a new spine, it links fragmented programmatic clusters—transforming movement from a functional act to a cultural one.

Cut & Insert: From Storage to

Monolithic concrete bays, once optimized incised to introduce voids, insert light, surgical tactic not only provides spatial palimpsest of industrial occupation. galleries, ramps—are threaded through and present while enabling new modes

Memory

optimized for bulk storage, are selectively light, and generate permeability. This spatial relief but reveals the layered New architectural elements—stairs, through these openings, mediating past modes of use.

Container: From Product to Culture

Standardized freight containers, symbolic of globalized trade, are repurposed as modular cultural units—housing maker labs, artist studios, retail popups, and civic micro-programs. Their formal legibility and mobility allow for flexible, user-driven adaptation. Installed along railway tracks or within garden clearings, they stitch the memory of logistical flows into a more human-scaled, participatory landscape.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

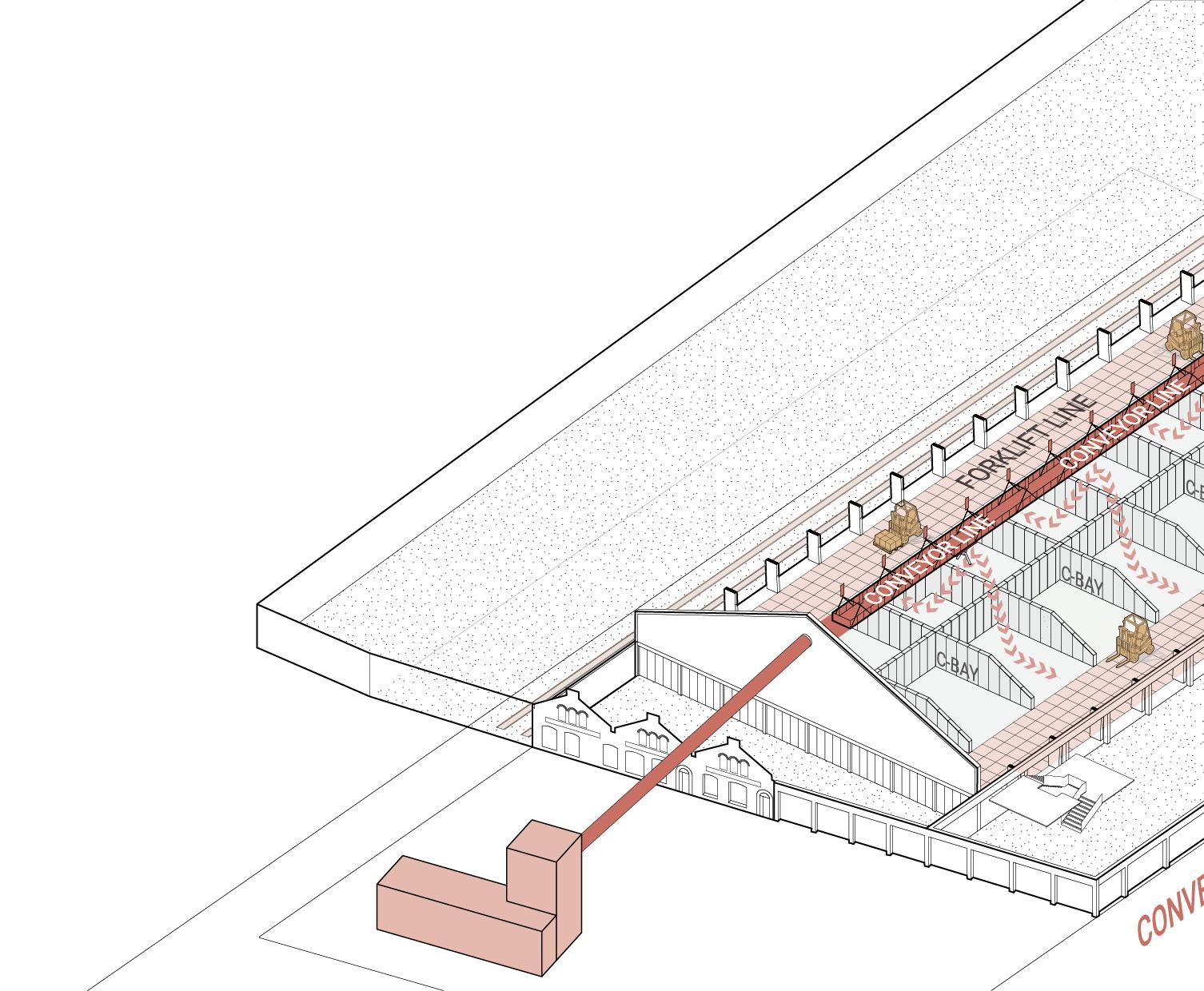

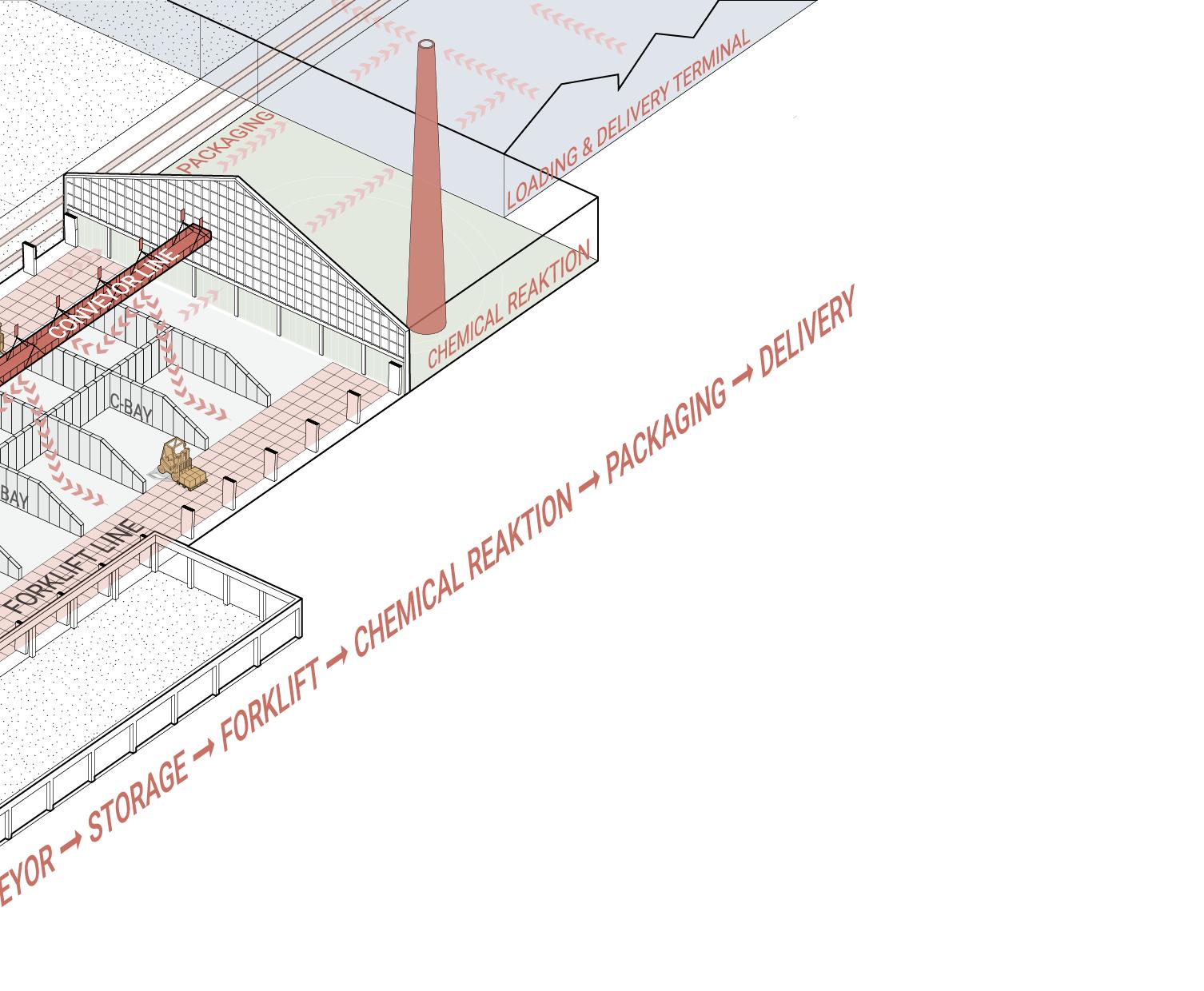

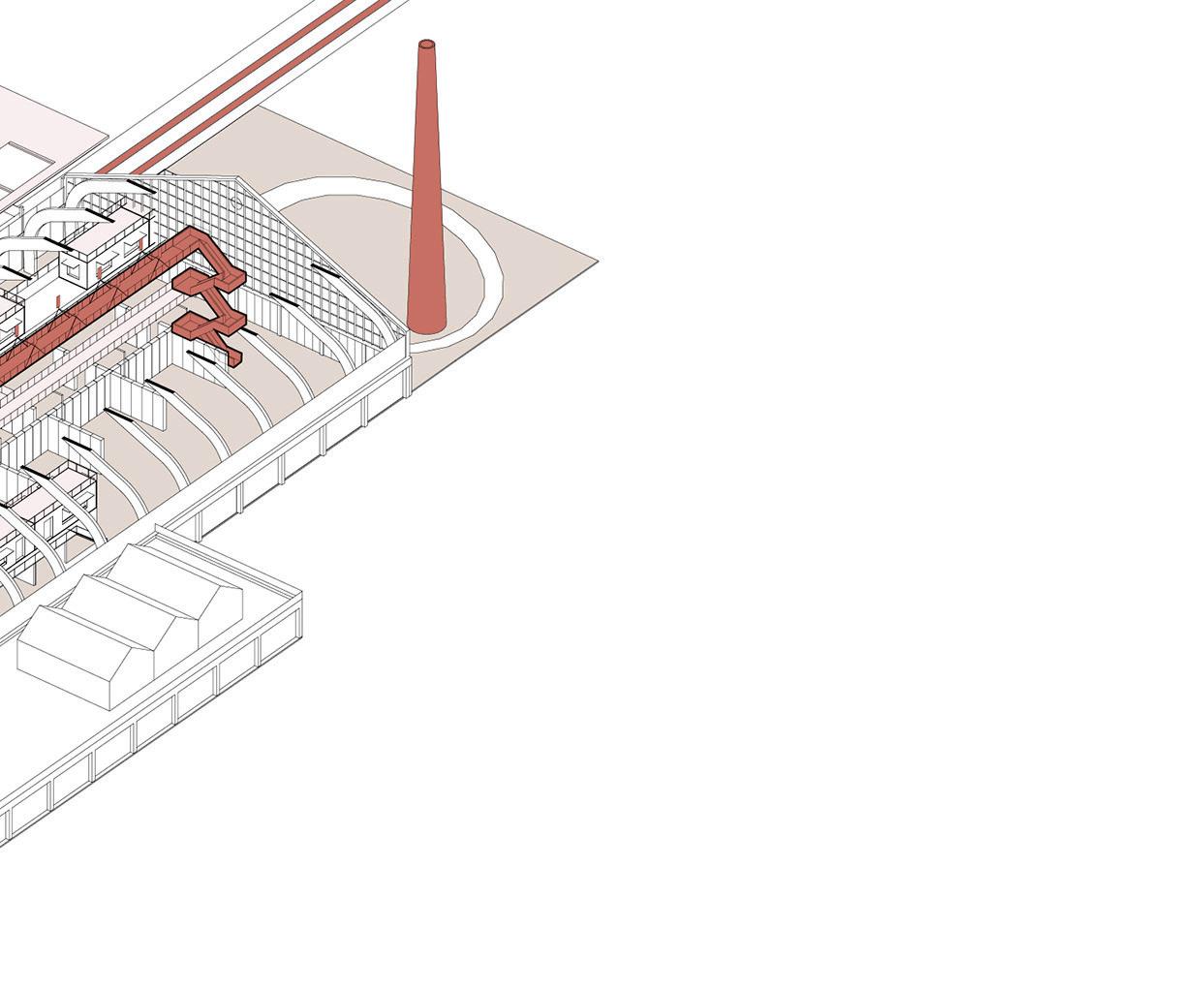

8.3.1

Original Functional Diagram

“From

Material Flow to Human Flow”

The factory once processed and distributed material—now, it cultivates meaning.

This diagram illustrates the original operational system of the Triferto fertilizer factory: raw material entered from the waterfront, moved via conveyor belts into storage bays, was processed through chemical transformation, and ultimately packaged and dispatched from the rear delivery terminal.

Original flow logic: Conveyor-Storage-Forklift-Chemical ReactionPackaging-Delivery

The spatial organization was purely functional— geared toward efficiency, movement, and control. Every architectural component served a role in the production chain, forming a loop that linked logistics with physical transformation.

Today, these same paths are reinterpreted as cultural infrastructure:

Conveyor lines become elevated walkways, guiding visitors through exhibitions and installations.

Forklift routes evolve into internal promenades and workshop corridors.

Storage bays transform into modular ateliers, forums, and memory spaces.

The former delivery terminal becomes a public stage for cultural output.

The chemical reaction square—once the core of material transformation—is reimagined as a gathering plaza: a site of dialogue, interaction, and collective energy.

The architecture no longer stores material—it stores memory, emotion, and meaning. What was once a choreography of machines becomes a choreography of people.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

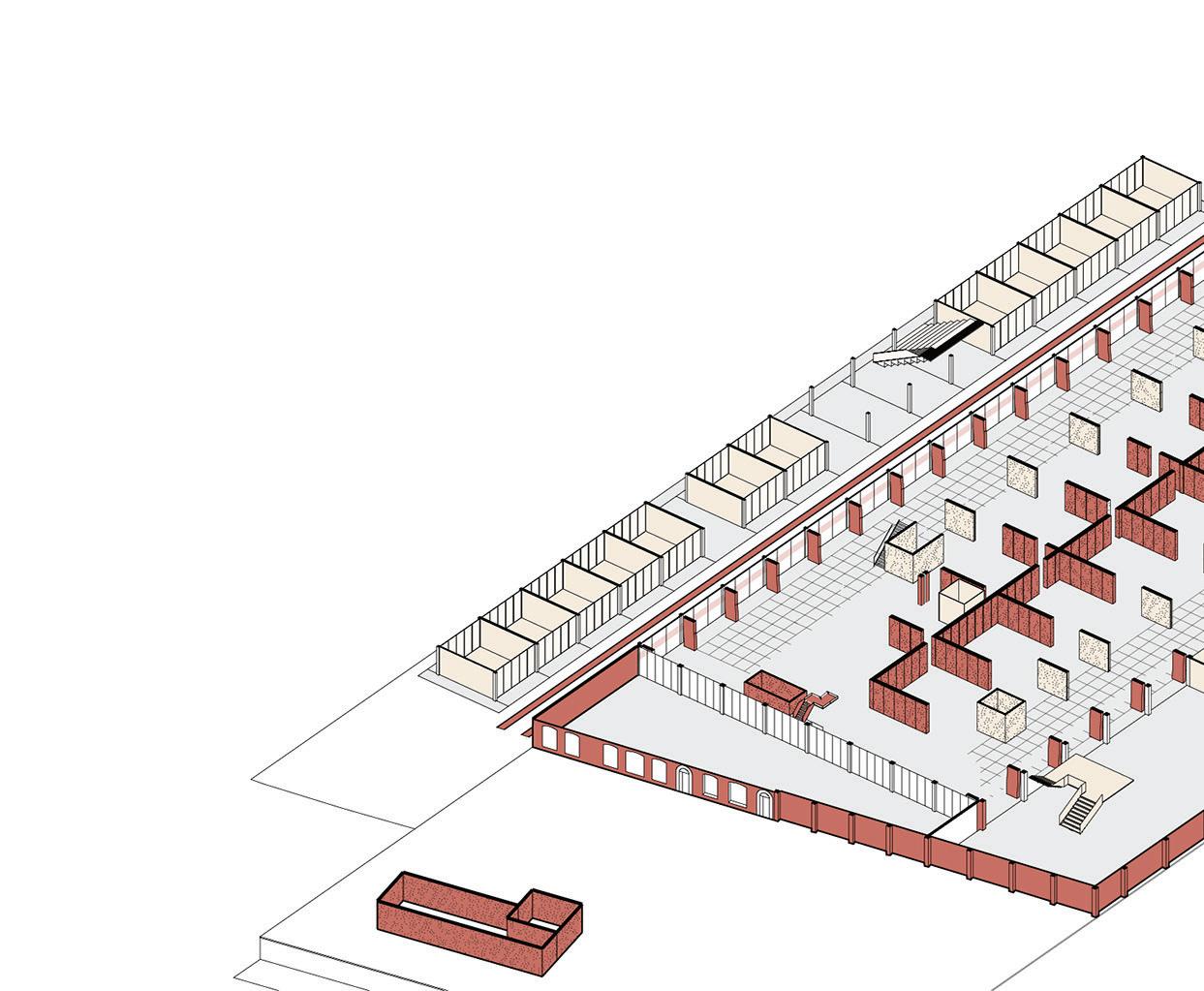

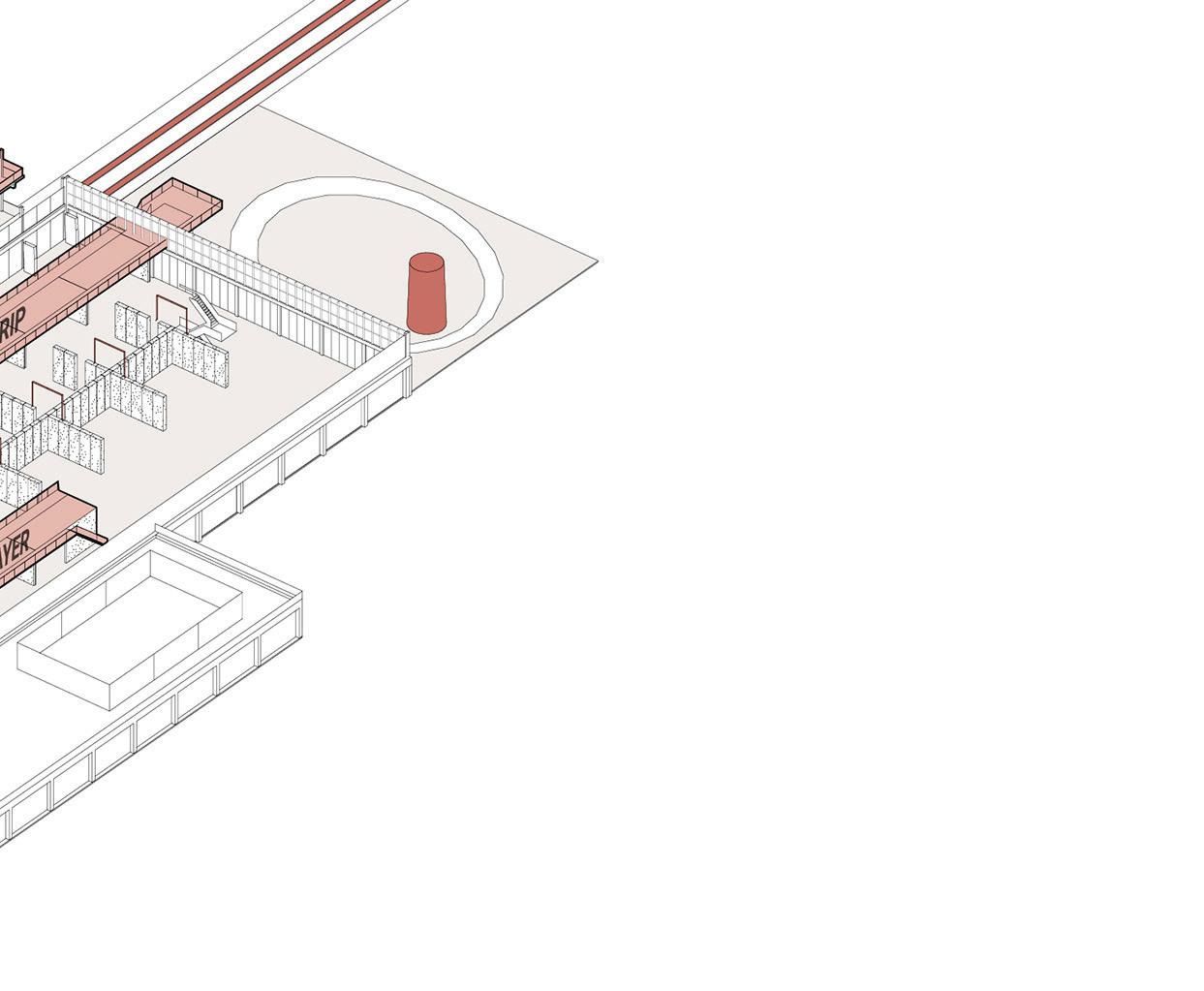

8.3.2. Preserved and Added Elements

Continuity Through Contrast: Rewriting Without Erasure

This diagram highlights the architectural palimpsest created through the dialogue between preservation and addition.

The red elements mark the original structures— primarily the central concrete storage bays, masonry

walls, and the linear circulation spine. These preserved elements carry the physical memory of the site: its material gravity, industrial logic, and spatial rhythm.

The light-toned interventions represent new additions: lightweight modular insertions, structural bridges, staircases, and new façade elements. These additions do not seek to mimic the original; instead, they expose it—framing voids, reprogramming flows, and providing new layers of access and inhabitation.

Rather than creating a seamless blend, the proposal intentionally juxtaposes new and old. This contrast reinforces the narrative of transformation:

-Preservation anchors memory. -Addition signals reactivation.

Through this approach, the factory becomes a vessel of accumulated time: a framework where material permanence meets programmatic renewal, and architectural silence is interrupted by contemporary voice.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

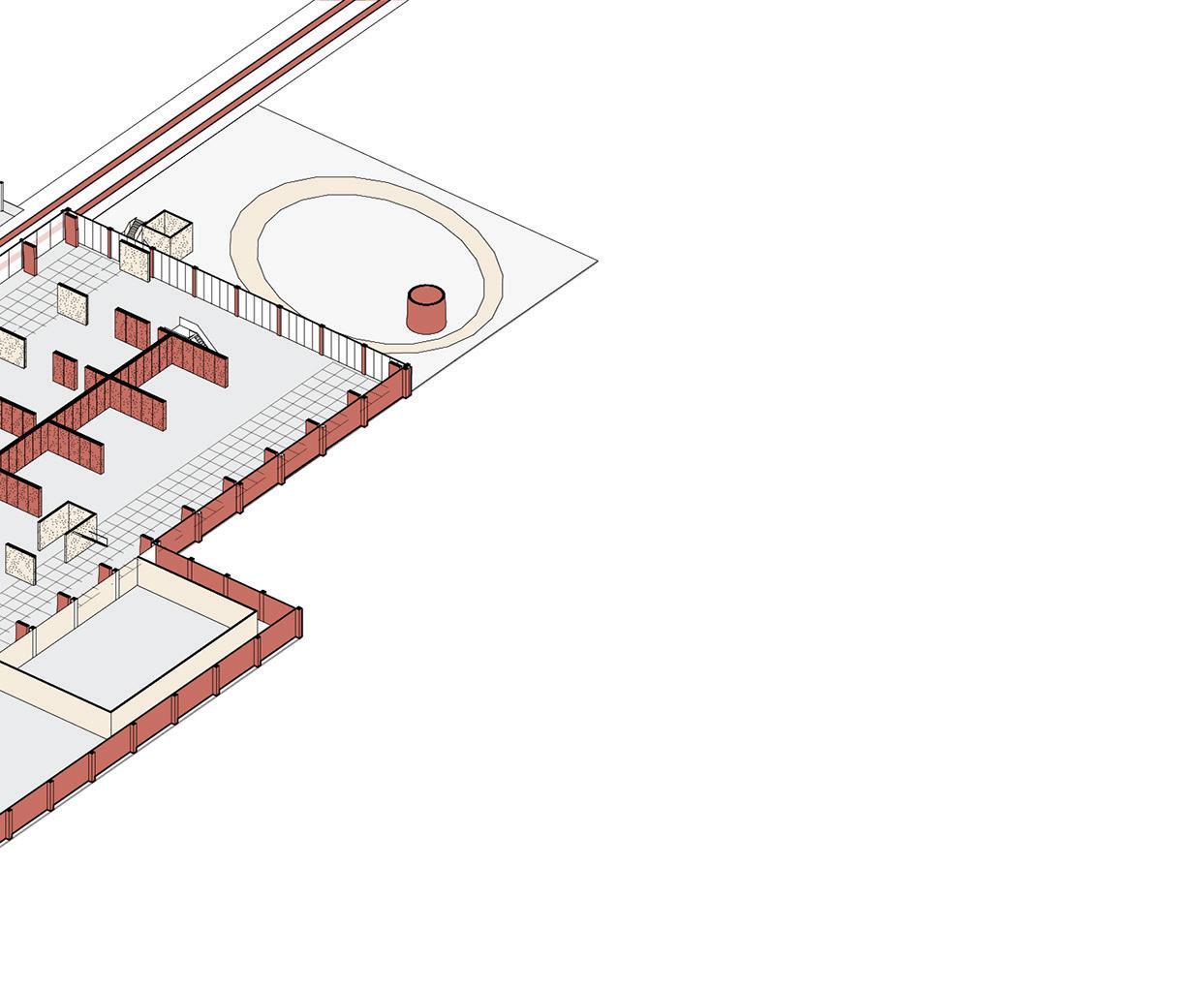

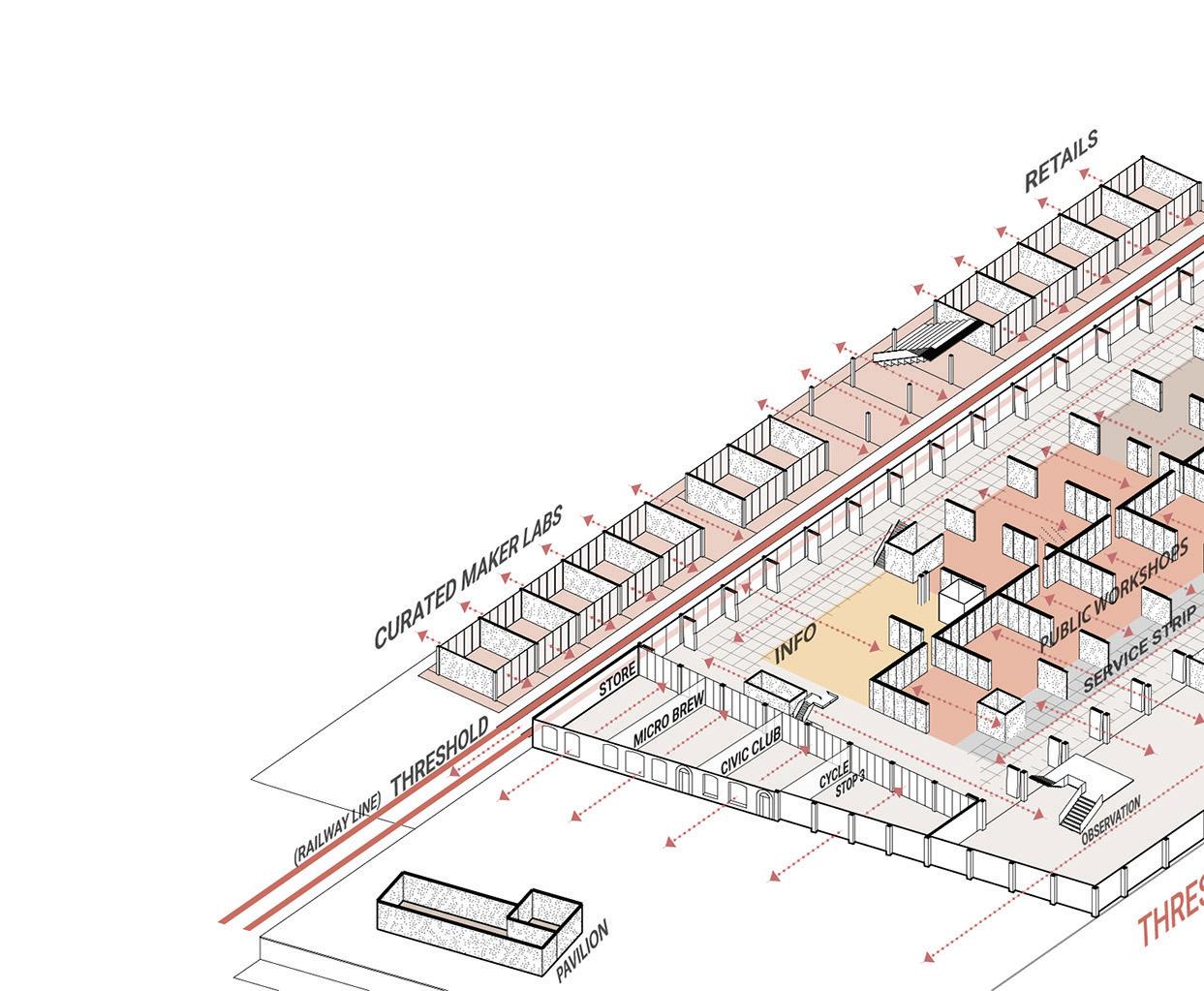

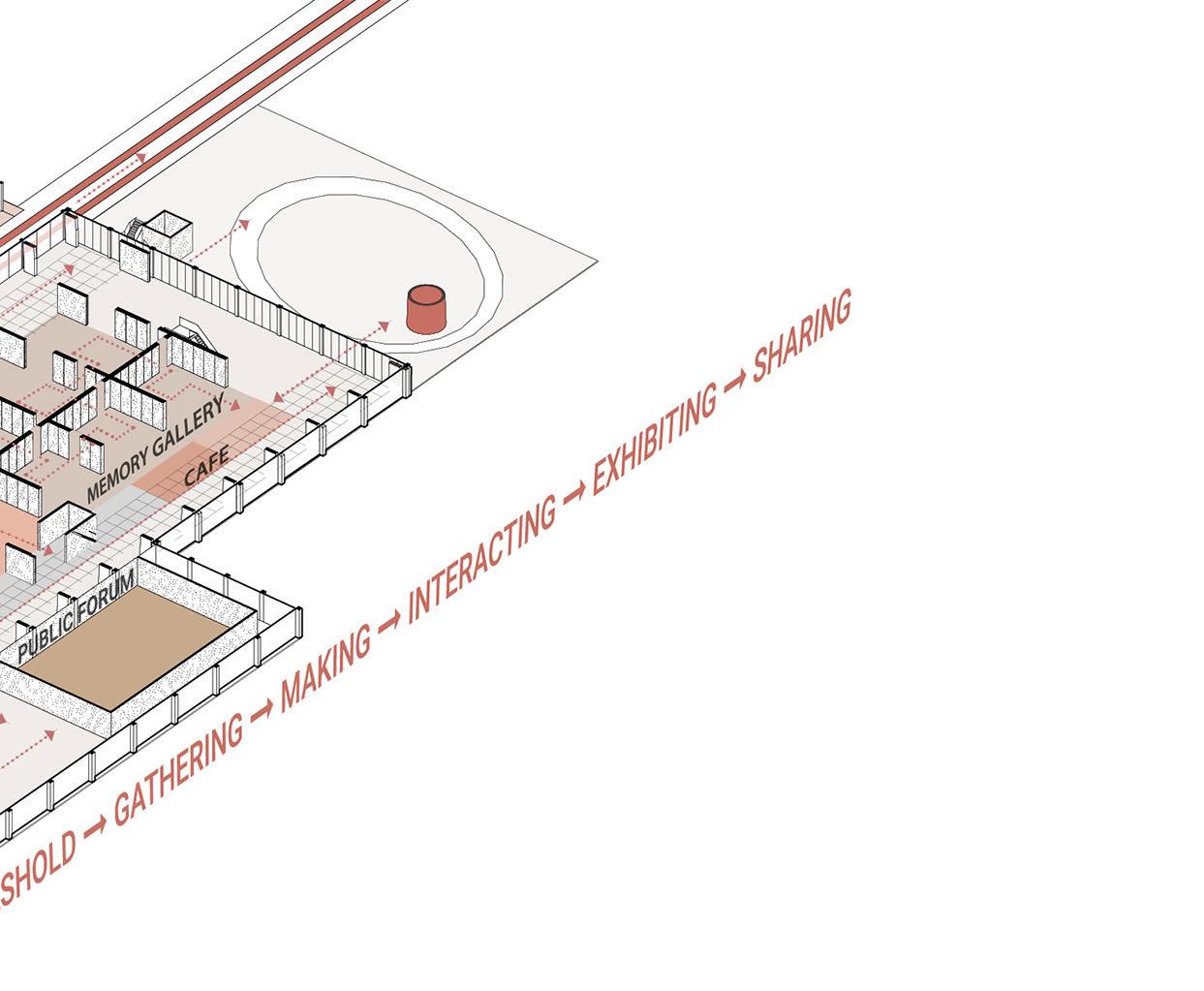

8.3.3. New Programmatic Zones

From Factory Hall to Cultural Circuit

This diagram maps the spatial transformation of the former industrial hall into a layered constellation of cultural programs. Building upon the logic of the original structural grid, the proposal introduces distinct yet interconnected zones, each orchestrating a different mode of public engagement—from gathering to making, from exhibiting to sharing.

The linear path of movement—from threshold to memory gallery—frames a sequence of spaces that unfold like a dramaturgical script. These zones are not arbitrarily distributed, but curated to echo the site’s industrial past while projecting new cultural functions:

Threshold & Pavilion Zone: Orients visitors and provides public interface elements such as a store, microbrewery, and civic club, situated along the former forklift path—now a shared pedestrian spine.

Curated Maker Labs: A series of modular workspaces aligned with the old railway line, accommodating small-scale production and open studios.

Public Workshops & Service Strip: Located within the central storage bays, these units reinterpret former storage cells as participatory creative modules.

Memory Gallery & Café: Strategically placed near the old chemical tank, forming an introspective anchor at the end of the path—where cultural reflection meets leisure.

Public Forum: Positioned at the edge, it serves as a performative node, enabling events, talks, and seasonal gatherings.

Together, these zones reinterpret the logic of industrial logistics as a spatial choreography of community interaction. By layering making, observing, and exchanging, the building becomes a cultural engine rather than a production facility— shifting the logic of flow from materials to meaning.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

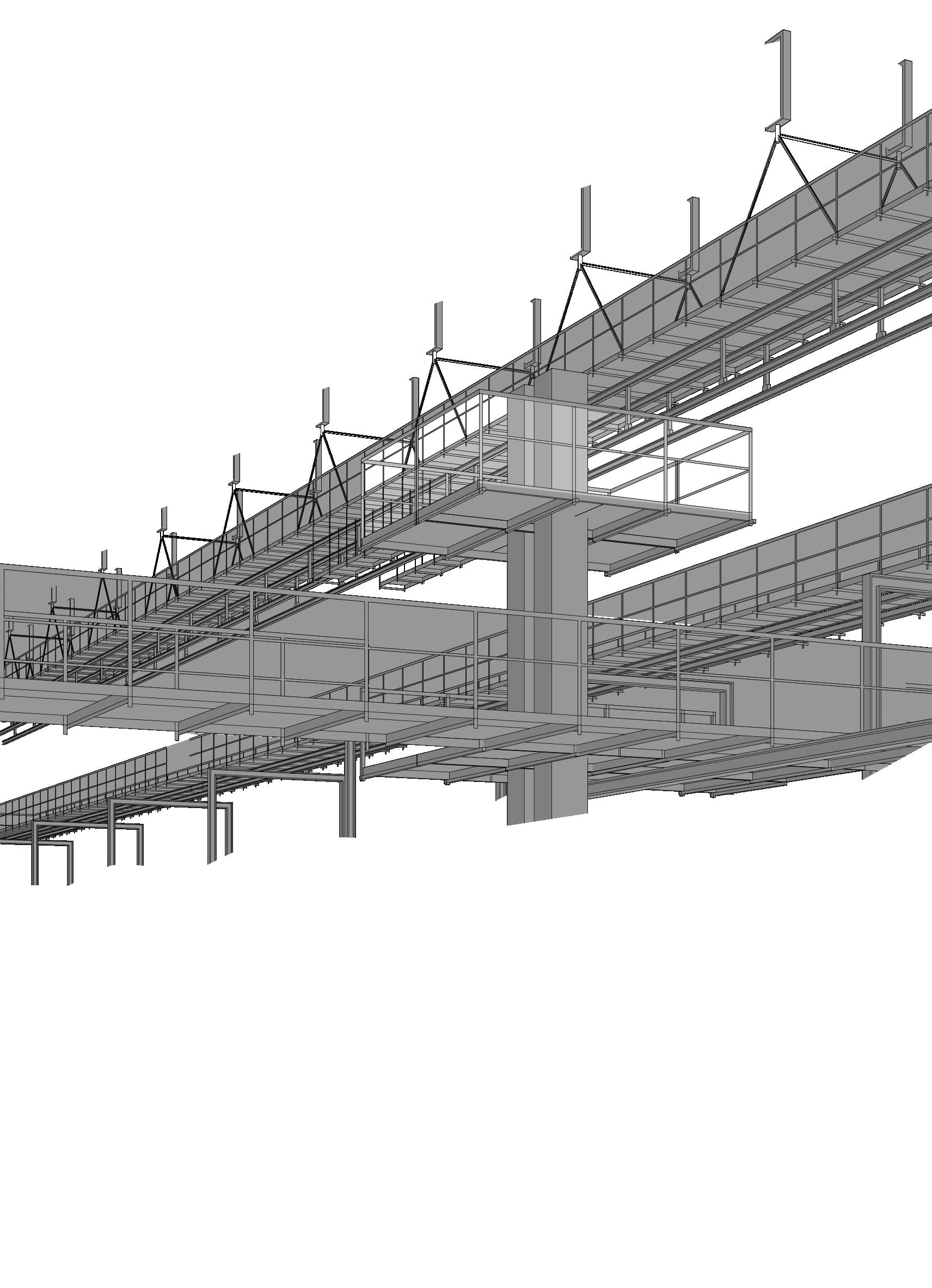

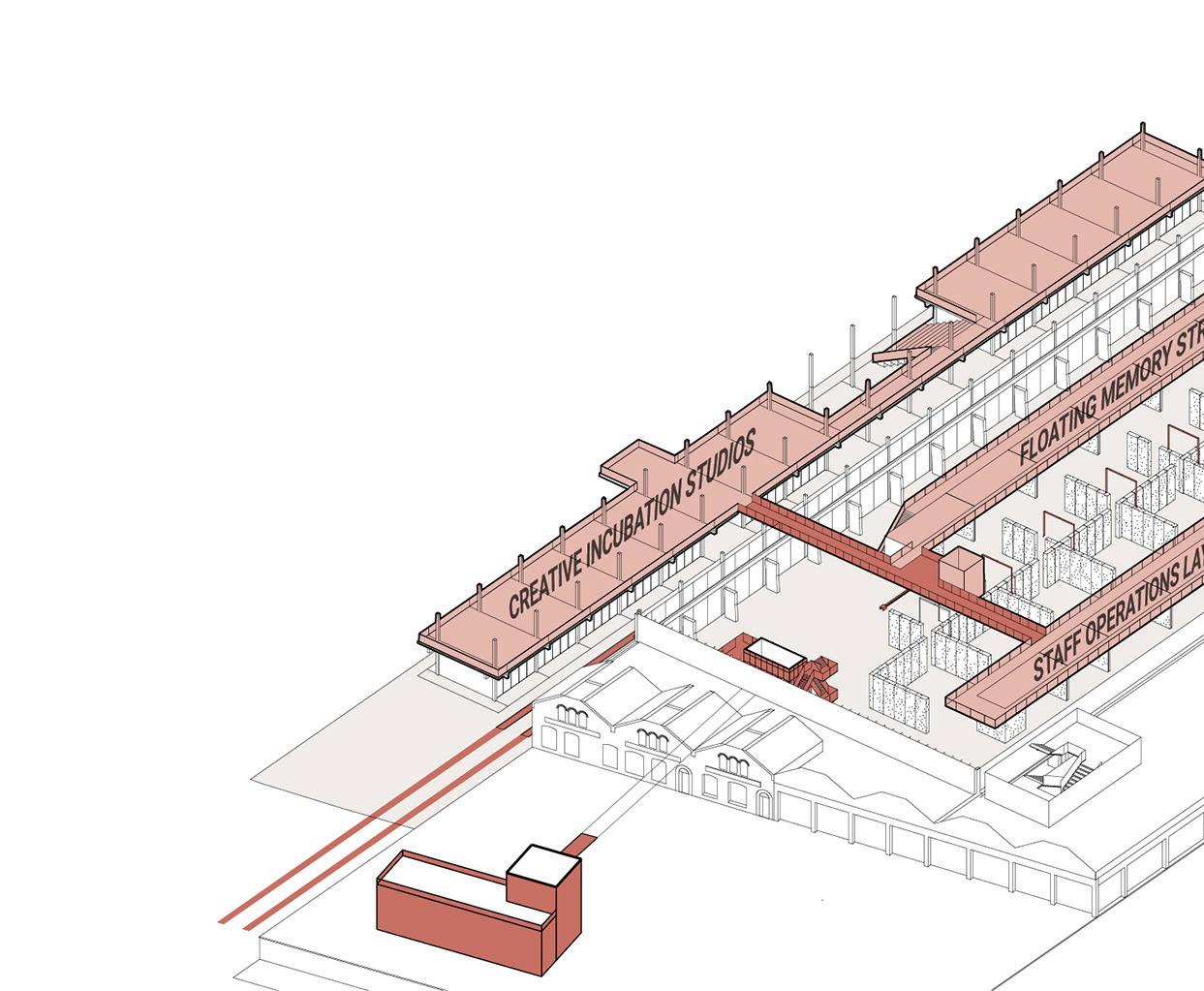

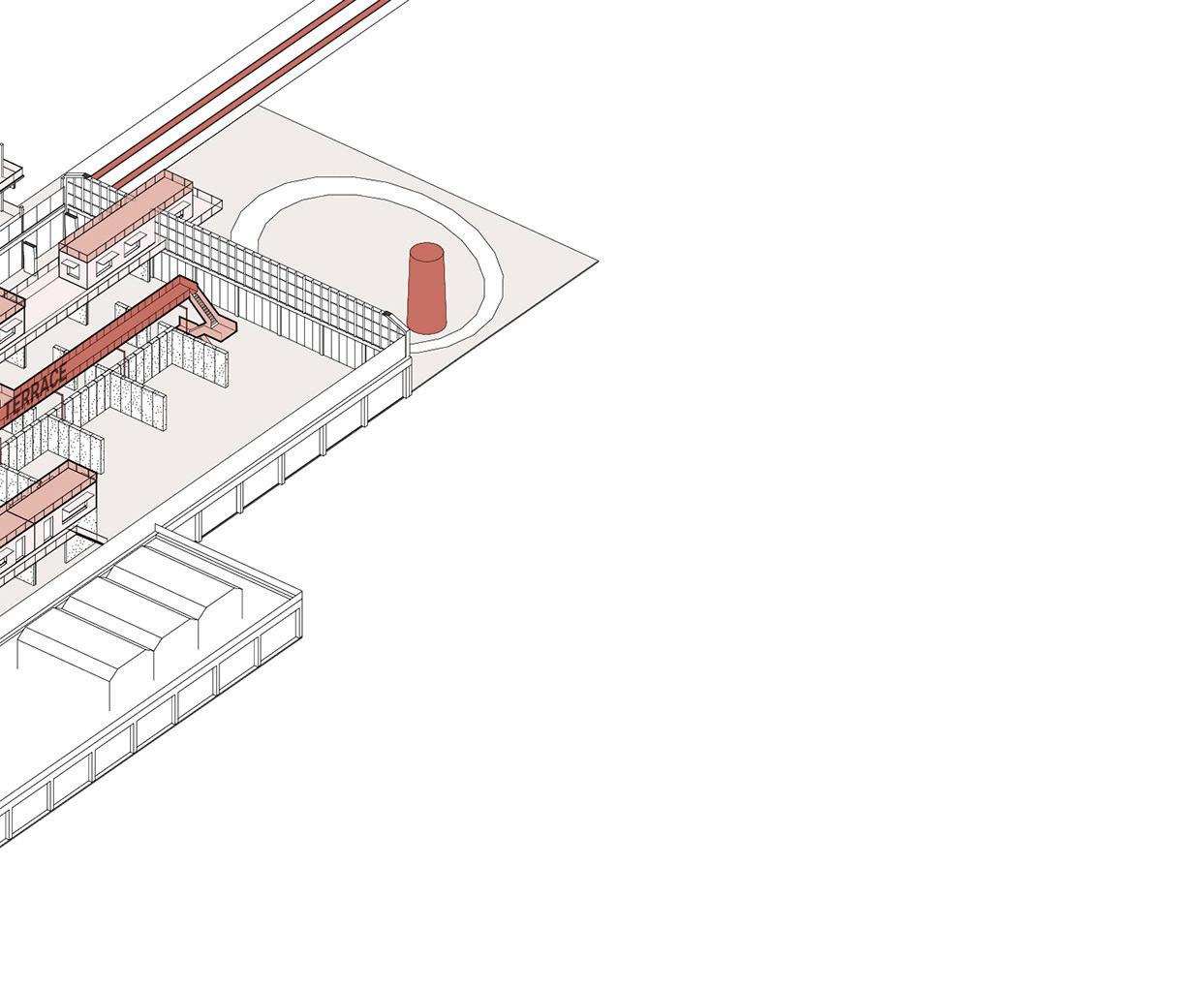

8.3.4. Upper Floor Circulation Bridges

The memory of movement continues, now with new directions.

This diagram illustrates the reinterpretation of the factory’s elevated circulation systems through a series of bridges and suspended platforms. Anchored in the memory of the original conveyor lines, the intervention introduces new connections that reprogram upper-level flows into human-centric networks.

The Creative Incubation Studios, located

along the periphery, are linked through overhead connections that frame views, invite exploration, and facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration.

The Floating Memory Strip runs longitudinally, offering an elevated narrative path. This bridge allows for moments of pause and reflection, framing the workshop grid below while referencing the historic conveyor spine.

The Staff Operations Layer provides service-level access, visually light yet operationally essential.

These lightweight additions contrast with the massiveness of the original concrete, creating a vertical layering that is both spatial and programmatic. Visitors now navigate suspended walkways where machinery once moved material. Through this transformation, the factory’s circulatory logic is not erased—but expanded and diversified, supporting a new choreography of creative, cognitive, and collective flows.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

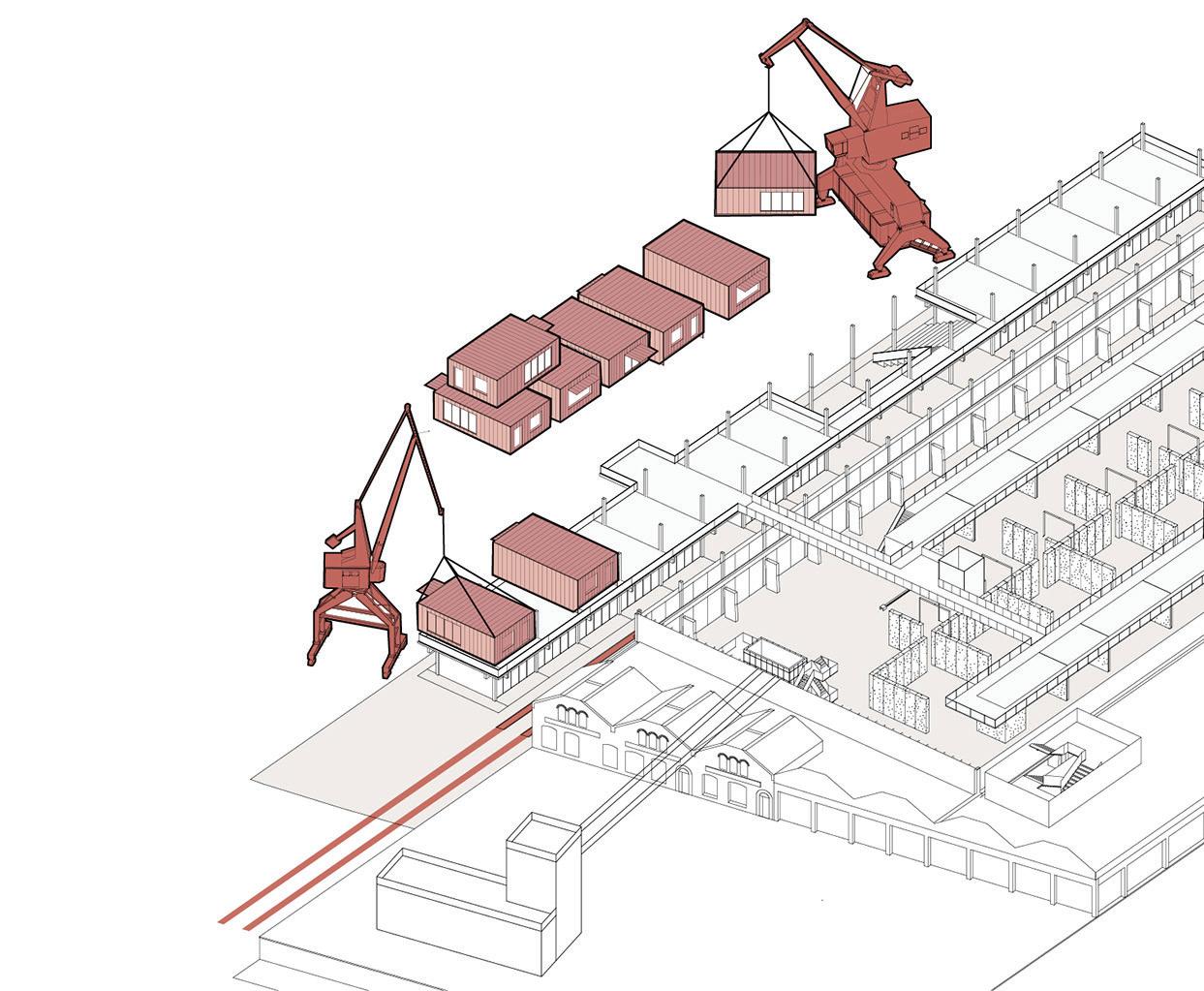

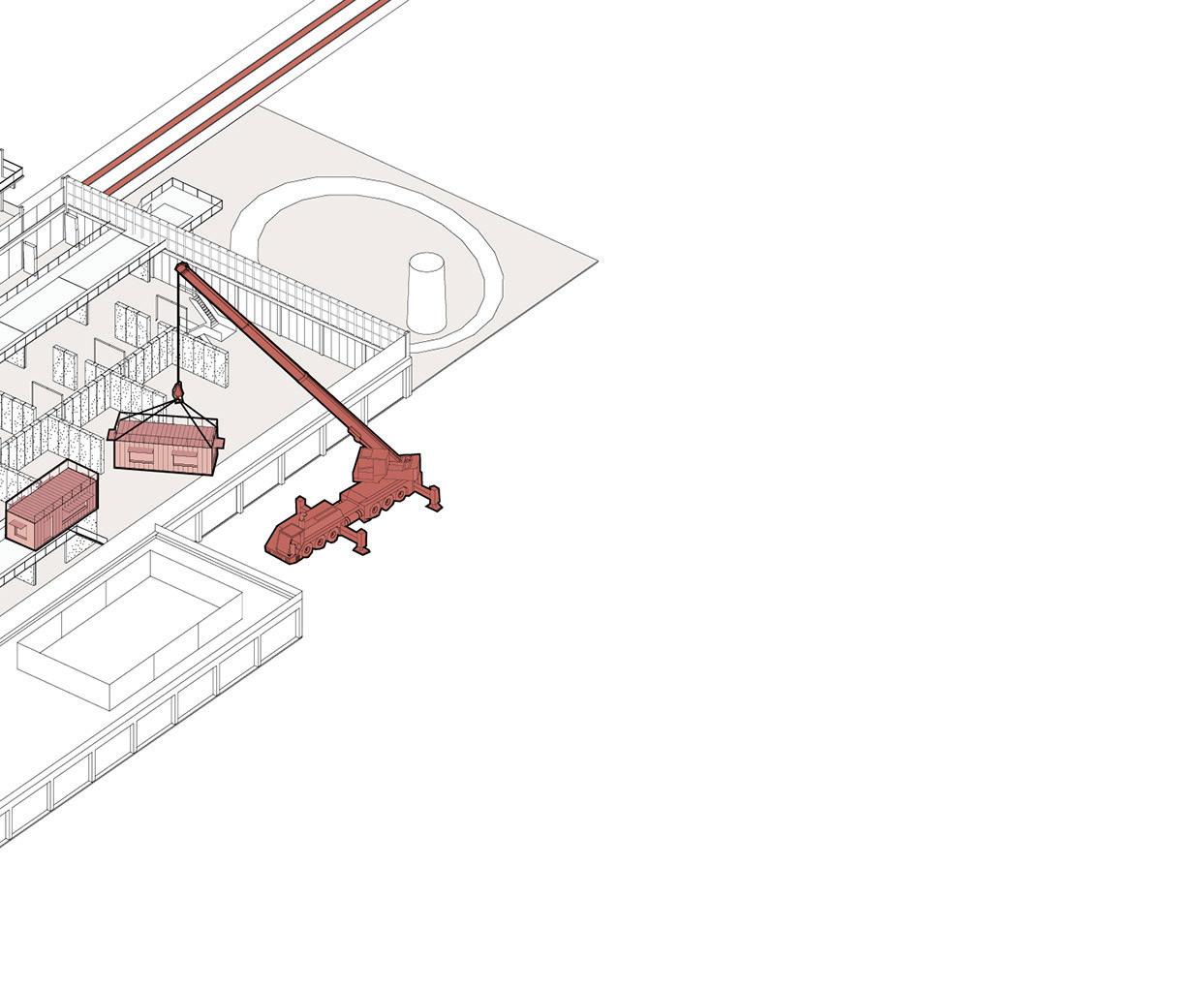

8.3.5.

Placing Containers for Reuse

Second-hand Bodies, First-hand Stories.

Shipping containers — once transient vessels of global commerce — are here reimagined as modular cultural cells. Inserted with surgical precision into the factory’s massive skeleton, they serve as lightweight studios, galleries, and shared creative spaces.

This diagram illustrates the arrival and distribution of containers via overhead cranes and mobile lifting units, in direct reference to the site’s logistical history. Their new placement is not arbitrary; it is choreographed along the memory of material flow, echoing the rhythm of past industrial activity while enabling a new kind of productivity: cultural, communal, and cognitive.

Containers are clustered and stacked to form dense collaborative clusters. Exterior and interior placements balance permanence and flexibility The use of second-hand containers reinforces the project’s adaptive reuse ethic, while offering spatial variety and architectural contrast to the heavy concrete frame.

These inserted elements bring in narrative multiplicity: each container may host a new maker, a community archive, a temporary installation, or a

shared workspace. Their presence is a testimony to the project’s core agenda—transforming logistical infrastructure into platforms for living culture.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

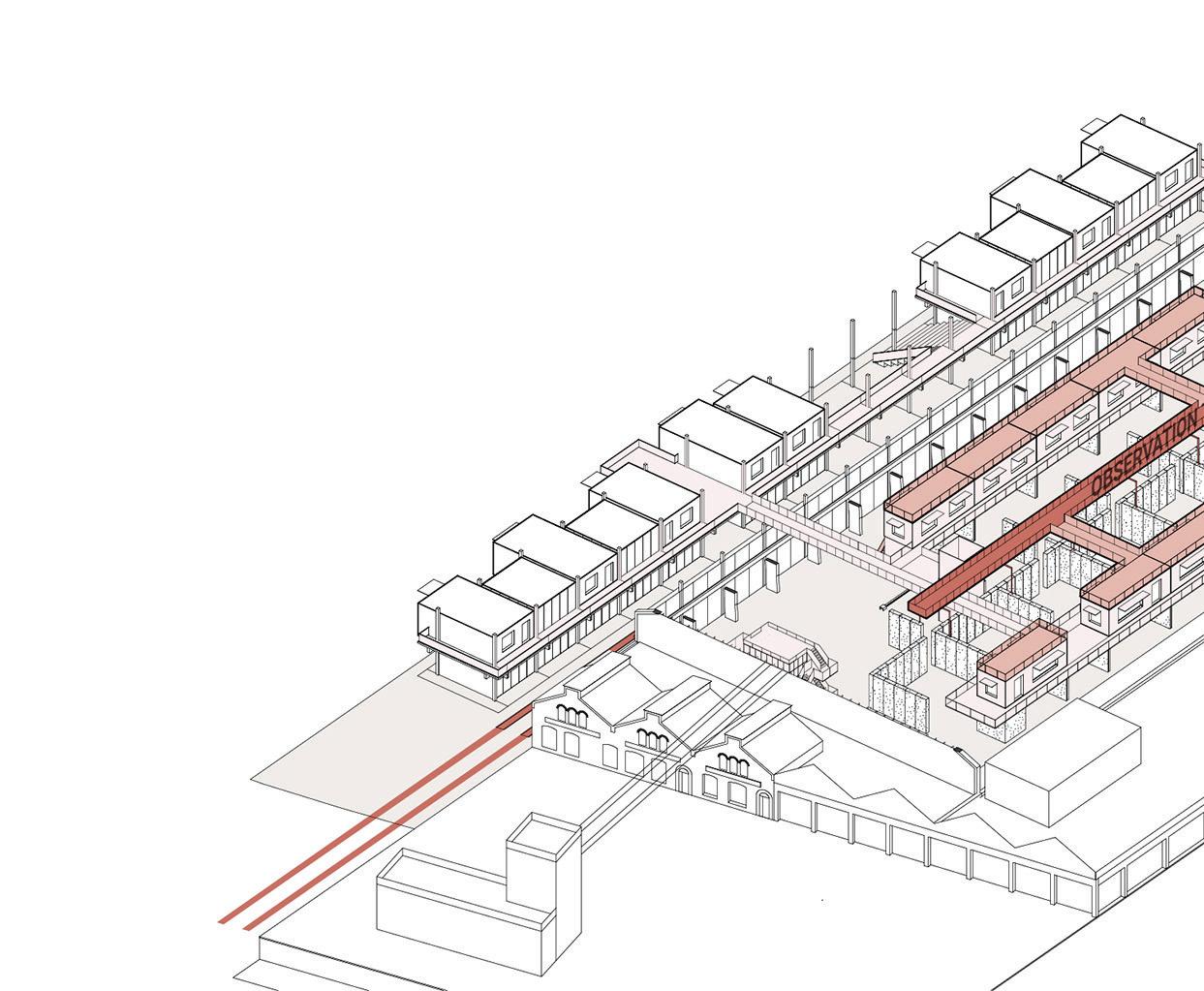

8.3.6.

Second Floor Circulation Bridges

Observation becomes navigation.

The second floor circulation bridges are envisioned as elevated public terraces—new urban promenades threading through the preserved industrial grid. These walkways connect the inserted container units, while offering continuous visual engagement with the layers of activity below.

The central bridge, labeled Observation Terrace, is not merely connective—it is reflective. Positioned directly above the main cultural production zones, it allows users to pause, observe, and interpret. This bridging strategy mirrors the former overhead industrial flows but transforms them into cultural navigational paths.

Bridges link containers programmed as studios, offices, and media units. Visitors navigate above active workshops, experiencing multi-level transparency. The alignment follows former logistical axes, continuing the memory of movement but now in a humanized form.

These paths turn the factory into a walkable archive, where users move not just across space, but across stories—witnessing how old infrastructures frame new practices.

8. Architectural Proposal

8.3 Axonometric Diagrams

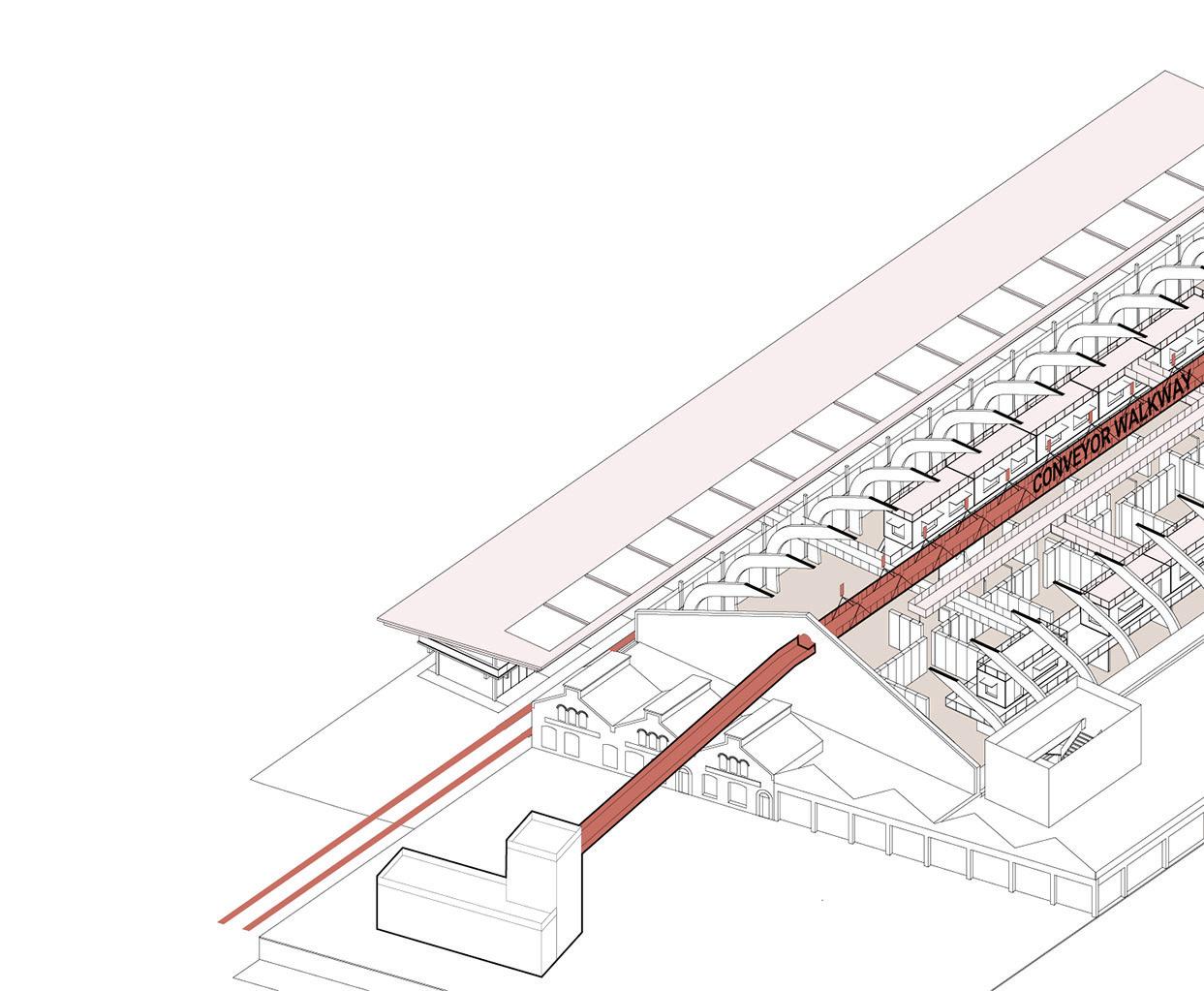

8.3.7. Third Floor Conveyor Walkway

From Logistics to Experience: Walking the Memory Line

The highest circulation layer reclaims the historical conveyor track as a new elevated pedestrian path. Originally used to transport processed materials toward the loading terminal, this linear infrastructure is now reimagined as a cultural walkway. It connects various programmatic units across the third floor, offering both visual oversight and narrative immersion.

The repurposed conveyor becomes a symbolic spine — bridging the building’s interior with the old railway loading platform outside. This spatial gesture not only links past and present but also literalizes the project’s transformation logic: from carrying matter to carrying meaning. As visitors traverse the red steel bridge, they retrace the building’s productive rhythms through a new lens of cultural memory and human flow.

8. Architectural Proposal

8. Architectural Proposal

8. Architectural Proposal

8. Architectural Proposal

8. Architectural Proposal

8.5 Site Plan

9. Conclusion

This thesis began with a question rooted in friction: how can a structure designed for logistics and material flow—Ghent’s 1920s fertilizer factory— be reimagined as a space for cultural continuity without erasing its industrial memory? The answer, as unfolded through design research, theoretical framing, and iterative architectural experimentation, lies not in erasure but in reinterpretation.

The project positions adaptive reuse not as a generic transformation of function but as a critical dialogue with spatial logic. By working with conveyors, storage bays, and monolithic concrete volumes, the design retains the building’s original DNA, even as it hosts radically different programs. Through the strategic use of “Cut & Insert” interventions, the industrial shell becomes porous to civic life— inviting participation, memory, and creativity.

The thesis introduced three core spatial tactics: reusing the conveyor system as a narrative spine, inserting lightweight modular containers as flexible cultural rooms, and weaving new circulation through previously inaccessible voids. These interventions emerged not from aesthetic speculation alone, but from a sustained reading of the building’s spatial intelligence. In doing so, the proposal transforms a space of material movement into a framework for knowledge exchange, production, and urban storytelling.

Grounded in Corboz’s concept of palimpsest urbanism, the design resists the lure of total renewal or nostalgic preservation. Instead, it enacts architectural continuity by layering new civic meanings onto infrastructural traces. Similarly, Jane Jacobs’s urban vitality and the principles of cultural sustainability underpin the thesis’s insistence on walkability, mixeduse layering, and social interaction—all vital for transforming this isolated post-industrial fragment into an active node within Ghent’s evolving urban fabric.

Ultimately, the project offers more than a sitespecific intervention. It proposes a model for post-industrial reuse that is materially respectful, programmatically open-ended, and culturally anchored. The Old Dockyards become not a fixed destination, but an adaptive framework—able to host shifting cultural needs while keeping the memory of labor, logistics, and landscape alive. Looking forward, this thesis lays the groundwork for future research in post-industrial urbanism, particularly in how spatial infrastructure can become a medium of collective meaning. The methods and strategies explored here invite further testing across other European port cities facing similar challenges. In a time when ecological and cultural sustainability are increasingly intertwined, the act of reuse is no longer optional—it is essential. And in Ghent, it begins with remembering how to move through concrete.

10. References

Alexander, C., Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A pattern language: Towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press.

ArchDaily. (2014). A photographic journey through Zollverein. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily. com/534996/

Bacon, E. (1967). Design of cities. Thames & Hudson.

Calthorpe, P. (1993). The next American metropolis: Ecology, community, and the American dream. Princeton Architectural Press.

COBE Architects. (2021). Jernbanebyen masterplan. Retrieved from https://www.cobe.dk/project/ jernbanebyen

COBE Architects. (2021). Europahafenkopf Bremen. Retrieved from https://www.cobe.dk/project/ europahafenkopf

Duxbury, N., Hosagrahar, J., & Pascual, J. (2016). Why must culture be at the heart of sustainable urban development? Agenda 21 for Culture –UCLG, 1–21.

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Island Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

Melia, S. (2010). Filtered permeability: A new approach to sustainable urban design. Urban Design International, 15(4), 287–292. https://doi. org/10.1057/udi.2010.19

Monderman, H. (2006). Shared space: Safe or dangerous? Traffic Engineering and Control, 47(10), 358–360.

National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). (2013). Urban street design guide. Island Press.

OMA, Böll Architects, & Krabel, H. (2010). Zollverein Ruhr Museum, Essen. Retrieved from https://www. oma.com/projects/zollverein-kohlenwaesche