14 minute read

Travels With My Father, 1959

by Udon Map

TRAVELS WITH MY FATHER, 1959

Advertisement

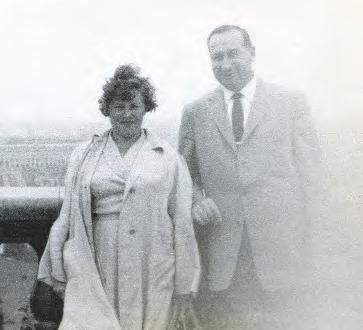

ad left it to me to plan this trip. We flew from New York to London first class, and in those days, the airlines treated you like kings. On the plane, my father went bananas over his filet mignon and red D wine but complained of having no sleep. Arriving in London, we went on a horse and buggy trip around town before our next flight. Dad, an insomniac of sorts, saw a man on a sidewalk, and as we traversed the meat packing district, remarked “I was in first class without a minute’s rest, and there’s a man fast asleep with a chicken on his head.” A minute later, he ate his words, falling fast asleep, his head bobbing up and down, in step with the horse’s hooves. Isn’t it amazing the things you remember? On to Prague we went for a four-day tour of the then Communist country. I recall striking up conversations with young people in restaurants and on streets. They were far more fascinated with us than vice versa. New York, democracy, new cars, my father’s job – all were subjects which seemed like fantasy to these Czechs. This was sixty years ago, so there’s lots I do not recall. However, it is possible that our next stop, after Prague, was the then Soviet Union. Since my college major included Russian history and government, I planned for us to spend almost a month in that country.

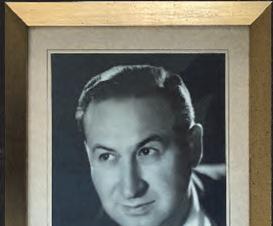

BIG mistake for Dad, an “out-of-body” experience for me. This was the era of the cold war, tourists did not include people from the West, and Communism was at its height. The situation was as follows: my dad, Albert Shore, a 50-year-old capitalist entrepreneur, had employed our system of government to the nth degree. He was born the son of a poor immigrant and worked his way up the ladder of the American dream. As such, he expected prompt service in his home, at restaurants, hotels and stores.

By way of contrast, he was travelling with his 22-year-old daughter, who was fascinated with the Soviet ways no matter what, unaccustomed to immediate service, and thrown by absolutely nothing. In New York, I was a face in a crowd. In Russia, I attracted crowds who showed interest in my attire, appearance, and my explanation of our American way of life. Young men showered me with small bronze Soviet pins, no one seemed resentful as I “sold” our system of government, free press, etc.

First arriving at the main hotel in Moscow, we were unaccustomed to the extremely tall plain Soviet style building. Every floor housed a babushkaclad older woman sitting at the elevator. We were lucky the elevators were running since the staircases were roughly 2 or 3 times the height of staircases at home. Our accommodations, old fashioned and stark, were bugged from the inside. Outside our rooms, men walked back and forth in search of spies. One night, my father attended a basketball game between the Harlem GlobeTrotters and the Russian team. I stayed in my room and answered my phone which rang incessantly, undoubtedly to ascertain my whereabouts.

For dinner, we frequented restaurants which served typical Russian borscht, stroganoff, various stews and, of course, vodka generally accompanied by oranges. We loved the caviar as it was the real thing. One night while dining, we decided to dance to the fast beat of a local band. As we jitterbugged and lindy hopped, all eyes were on us. The Russians were astonished at these strange dances, and we enjoyed “wowing” them.

However, my father became infuriated when he would beckon a waiter. Frequently, “the help” merely responded by remaining immobile, smirking, waving a hand as if to say hello and walked away. We knew they enjoyed taunting us, but no one could fire them since they were hired by the

state. The food was bad, many waiters had multi-colored gravy smudged over their aprons, the silverware was unclean. My father was throwing a fit, but I was unperturbed, already accustomed to mass produced food at college.

Our guide in Moscow, Helen, was kind. She showed us the main sights, such as the Kremlin, St. Basil’s Cathedral, GUM department store where the shelves were practically empty, and a historic Russian monastery. As we drove an hour to get there, we saw dachas, fields, huge trees, farms and life outside the city. No sign of our citified suburbs but plenty of people on foot, few cars, many horses and carts. A striking observation was their attire. In one month, I saw only ONE well-dressed woman and she was from China. Sorry to say, women wore the closest thing to a shower curtain – plain, ugly floral cotton wide dresses or skirts, little makeup, clunky shoes with laces, and many were overweight. While in Moscow, we visited a synagogue where my father conversed in Yiddish with the congregants, who made a motion of choking themselves when they were illustrating the life of Jews in Moscow.

After Moscow, we flew to several cities in the country’s interior. These included Yalta, Sochi, and the provinces of Georgia and Kiev. Conservative, provincial, poorer and more agrarian than Moscow, these areas bespoke centuries from the past. On the Black Sea, we went to the beach and were astonished at the sight: women, mostly ungainly and overweight, and their families crowding together, lying on rocks, with little sand in sight. Unglamorous was hardly the word. Confirming the poverty, the “taxis” to

and from airports were old, tinny cars which travelled at the speed of a fast bike in order to conserve gasoline. Air conditioning in hotels was nonexistent. Nowhere was there evidence of material success, modernism, or life as we knew it.

In Georgia, our passports were confiscated for three days. We had been standing on a street corner and saw a beggar to whom a boy in our group gave a few coins. Since begging was illegal, an official, suspecting us of spying, began yelling at us. Making matters worse, my father developed a bad case of diarrhea and had to lumber up three very high sets of stairs to reach his room. Worse still, we had run out of toilet paper. When he telephoned to order more, after being continually disconnected and ignored, he finally heard these words: “The head of the department of toilet paper is on vacation.” My dad was not thrilled.

In Sochi we met only a few people because the language barrier was problematic. One young man, however, remains clearly in my memory. Tahir, our guide, was someone to whom time was never a consideration. My father and I were scrupulously punctual but ended up waiting as much as an hour for Tahir to show up for the tours. Exasperated, my father finally spoke up and said, “THIS IS THE FOURTH TIME WE HAVE WAITED – WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN?” to which Tahir lethargically responded “I was tired.” My father stared at him with hatred in his heart! As years passed, that story became a cornerstone of my father’s oft repeated references to our trip.

Our next stop was Tashkent, then Alma Ata and Samarkand. We were getting relatively close to Siberia. Mongols resided in these mysterious, faraway lands which were virtually unknown to foreigners. Now the largest city in Kazakhstan, Alma Ata originally was an ancient settlement which had been destroyed by Mongols – then, Cossacks, peasant settlers from European Russia and Tatar merchants established themselves there. My dad, over six feet tall, was Gulliver in a land of Orientalized small people. He wore a tall blue and white hat, which we had bought in Moscow, making him a seeming giant. Part of the Silk Route, these lands, once the seat of astronomy and mathematics, breathed an ancient, rural aura. Unpaved roads traversed dusty

hills, open fields, peasant-like dwellings and dirty town squares. It’s a kind of blur to me now, except for one unforgettable story about Alma Ata.

I really wanted to see that legendary city, then the seat of Russian cinematography. My father remained behind, but not before he interviewed Aram Aram, the double-named Jewish tour guide who escorted me on an entire day outing to Alma Ata. My dad informed this young man that “If anything happens to my daughter, I will KILL you” – at which point a pair of handcuffs bound me to my guide. We flew in a rickety tiny plane along with a few Americans, including a handsome young man working for an oil company. After my handcuffs were removed, my new friend and I held hands the whole day. The mutual attraction was tactile. Following a city tour, we attended a “floor show” imitative of the French Can Can. Ten obese Russian women, dressed in brown skirts with tucked-in white cotton blouses and British-type laced brown leather shoes, clumsily formed a chorus line and kicked their hairy legs – hardly in unison – while we Americans contorted our faces to avoid laughing hysterically. We didn’t want to be mean, but that scene overwhelmed any semblance of self-control. Following a cabbage and rice dinner, we went to the airport (a runway in a field) to discover that our plane was several hours delayed. Arriving back to the motel around six in the morning, I saw my father sitting with another man, both decidedly inebriated, parked on a balcony awaiting my return. Both men were too drunk to be upset, instead laughed uproariously at my adventures.

I would be remiss if I omitted that fact that my father had intermittently attempted an exodus from Russia. Every request was rejected, much to his dismay and my delight. The excuse was that there were no flights to New Delhi, our next stop, and that we would have to wait for our purportedly scheduled flight. The airline, Aeroflot, was the final word. With no one to call, we simply waited it out. Additionally, we could not contact our family in America, nor could we receive word from them. My father was decidedly worried although I was too young to be concerned.

Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, was our final Russian destination. I loved the attractive hotel, majestic cathedrals, paved streets, the fabulous Hermitage, the statues, the people we met. My father loved nothing. Again, he requested exodus, only to be summarily refused. However, we did see the

Bolshoi Ballet, brilliant and inspiring – a night to be remembered. Especially since during the performance, a man tapped our shoulders with an announcement that our plane was leaving in an hour. Abruptly leaving the ballet, we dashed to the hotel, grabbed our bags and rushed to the airport. Except that the plane was conservatively six hours late, leaving us abandoned in an empty cow field with no water, electricity or food. We did, however, leave that morning en route to India – relieved, yet not knowing what adventure awaited.

On the flight, one of us rang for the stewardess. This was Air India, not Aeroflot, so we were expecting a response. However, we were informed that “all the stewardesses are unavailable” – that a typhoon was expected momentarily but the plane would “try to make it.” We experienced over an hour of intense shaking, abrupt dips, and rolling from left to right, then back again. We felt nauseated and extremely hot since the air conditioning system was broken. Furthermore, the stewardesses were stretched out, feeling sick, on the floor of the plane!

On to New Delhi where my father luxuriated in the gorgeous, sumptuous Imperial Hotel from which he happily called my mother. Additionally, he repeatedly swung open the minibar while holding up to the ceiling every Diet Coke and exclaimed “We’re in civilization!” All was well, Dad no longer had diarrhea, and we were halfway home. We toured Old Delhi ‒ horrified at the squalor, extreme crowding, naked children, bodies in the streets, garbage strewn everywhere, and emaciated people. We felt endangered in our comfortable, air-conditioned auto. The whole scene was confusing and overwhelming, we were absolutely bewildered.

New Delhi was less shocking. We shopped and bought Indian sandals and saris. I was treated to a two-piece blue and gold silk sari which I later wore at a college prom. We visited the Taj Mahal, the pink city of Jaipur, a famous fortress with gorgeous imprinted tiles, rode elephants, and ate delicious Indian food. We adored our stay at a pink Maharajah’s Palace which Billy and I visited many years later.

I must admit that aside from loving the fascinating adventures, some tension arose between my father and me. He complained about my attitude

and unpleasant disposition. On my part, I felt overprotected and stultified by his worrying and complaining. This dissonance was played out one night at the Imperial Hotel in New Delhi when I insisted on accepting an invitation from an older man for dinner and dancing. Defying my father’s displeasure, I accepted and learned what befell a girl accompanied by a sleezy, hyper-sexed older creep. Nothing awful happened, and I was only too happy to be on a date without any chaperone. The surprise came upon arriving back at the hotel in the middle of the night. There, guarding the entrance, a tall Sikh guard stood at attention, spear in hand, head wrapped in a turban, bedecked in a red and gold uniform. Next to this guard stood my father, similarly clothed and holding an identical spear. The two of them looked like attack dogs.

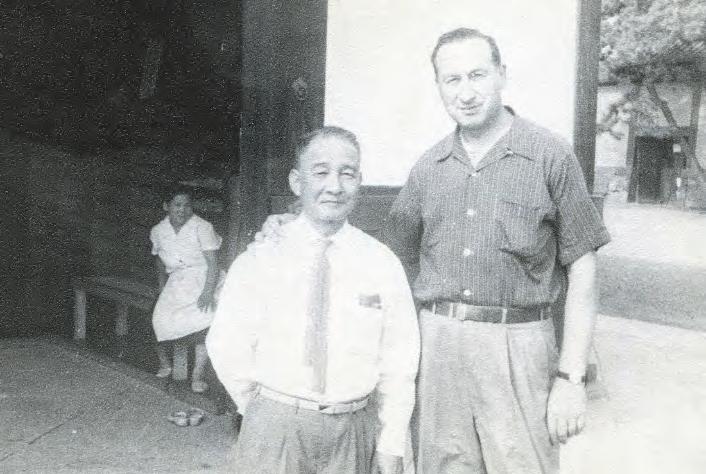

After leaving India, we flew to Tokyo. There we were treated to a Japanese tea ceremony hosted by my penpal of several years. His name was Mr. Kinbara, a Professor of History at the University of Tokyo. We went to his home, which was a unique honor since the Japanese have small houses and rarely entertain in them. We sat cross legged on the floor, and tea was served on a table situated in an indentation below the floor. (We liked this man who later came to New York with his family. After taking numerous photos, as is typically done by the Japanese, we took them for dinner to – unwisely – a Japanese restaurant.)

The other memorable event in Japan was the massage, a tradition enjoyed by women but particularly by men. During my father’s massage, I peeked through the window of his room and witnessed a muscular young

woman walking up and down his spinal column. He wasn’t objecting. Our final stop was Hawaii for a short time. We also flew via the Marshall Islands where the U.S. had played an important part in World War II and where I bought Billy his first Buddha for his collection.

In summary, my father and I experienced a unique peek into generally unknown cultures, as well as a chance to be exclusively together. I even related some of our experiences at his funeral. Although we had our differences, I remain eternally grateful to him for including me in the trip of a lifetime.

Years later, my father passed away not terribly long after my mother’s death. Without dwelling on what transpired, his illness – his second wife – the lawsuit which ensued – finally having my brother’s cooperation – all combined to create a miserably frustrating two years. It was a lesson in life’s cruelty and unpredictability for us to witness my father’s gradual demise, and seeing a person who had always called the shots become victimized in more ways than health decline. Tom was extremely helpful to us during the ensuing court case, as his contemporaneous notes confirmed the validity of our complaints against my father’s second wife. I wish I could end this on a happy note, but there was nothing happy to report, except that my mother’s illness was short-lived, she did not suffer, and her ending was charitable in its duration and nature.

After my father died, my brother and I inherited two shopping centers, and a piece of a third, in Massachusetts. My brother had some difficult issues, but deserves credit for his efficient managing of the shopping centers. Moreover, he got the timing right when the time was ripe for their sale. He and I had never been close – even as children – and the relationship deteriorated dramatically with the deaths of our parents. With my brother’s death in 2016, I said a final goodbye to someone who had effectively exited my life many years ago.